The crystal structure of a thermostable serralysin from Serratia sp. FS14 was solved at 1.10 Å resolution.

Keywords: metalloproteases, serralysin, thermostability, crystal structure, high resolution, Serratia sp. FS14

Abstract

Serralysin is a well studied metalloprotease, and typical serralysins are not thermostable. The serralysin isolated from Serratia sp. FS14 was found to be thermostable, and in order to reveal the mechanism responsible for its thermostability, the crystal structure of serralysin from Serratia sp. FS14 was solved to a crystallographic R factor of 0.1619 at 1.10 Å resolution. Similar to its homologues, it mainly consists of two domains: an N-terminal catalytic domain and a ‘parallel β-roll’ C-terminal domain. Comparative studies show that the shape of the catalytic active-site cavity is more open owing to the 189–198 loop, with a short 310-helix protruding further from the molecular surface, and that the β-sheets comprising the ‘parallel β-roll’ are longer than those in its homologues. The formation of hydrogen bonds from one of the nonconserved residues (Asn200) to Lys27 may contribute to the thermostability.

1. Introduction

The Gram-negative bacteria Serratia spp. are facultative anaerobic organisms that ubiquitously inhabit soil, water, animals, plants and humans. Serratia species can secrete a variety of exoenzymes including proteases, nucleases, phospholipases and chitinases (Monreal & Reese, 1969 ▸; Braun & Schmitz, 1980 ▸; Givskov et al., 1988 ▸; Chen et al., 1992 ▸; Petersen & Tisa, 2014 ▸). In particular, serralysin, a zinc-dependent metalloprotease, has been well studied (Miyata et al., 1970 ▸; Braunagel & Benedik, 1990 ▸; Baumann, 1994 ▸; Baumann et al., 1995 ▸; Aiyappa & Harris, 1976 ▸; Hamada et al., 1996 ▸).

Serralysin has been found to not only play important roles in bacterial nutrition but also in virulence as a cytotoxic factor capable of infecting larvae, mammalian cells and the human immune system (Marty et al., 2002 ▸; Kida et al., 2007 ▸; Petersen & Tisa, 2014 ▸; Shanks et al., 2015 ▸; Pineda-Castellanos et al., 2015 ▸).

Serralysin homologues have also been found in many other enteric bacteria including Erwinia chrysanthemi (Delepelaire & Wandersman, 1989 ▸), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Morihara & Okuda, 1992 ▸) and Photorhabdus luminescens (Daborn et al., 2001 ▸). These serralysin-family proteases share approximately 50% sequence similarity with each other. Serralysins are usually not thermostable and their proteolytic activities decline rapidly above 315 K, with no detectable activity above 328 K (Miyata et al., 1971 ▸; Liang et al., 2010 ▸; Sarker & Cornelis, 1997 ▸), with the exception of the serralysin isolated from Serratia sp. RSPB11, which retains 45% of its protease activity after pretreatment at 343 K for 15 min (Bhargavi & Prakasham, 2013 ▸).

The first crystal structure of serralysin to be reported was that from S. marcescens (Baumann, 1994 ▸). To date, 16 crystal structures of serralysin-family proteases have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (Berman et al., 2000 ▸) with resolutions from 1.64 to 2.8 Å, including native serralysins or serralysin homologues and serralysins or serralysin homologues complexed with inhibitors or ligands, but only three of them are from Serratia species [PDB entries 1sat (Baumann, 1994 ▸), 1smp (Baumann et al., 1995 ▸) and 1srp (Hamada et al., 1996 ▸)], with resolutions of 1.8, 2.3 and 2.0 Å, respectively. Structurally, the catalytic domain of serralysin comprises a large N-terminal lobe mainly consisting of a five-stranded mixed β-sheet and three α-helices, and a small C-terminal lobe mainly assembled from an α-helix and an irregular structure. The Zn2+-binding pocket is located in a groove between the lobes. Inhibitor binding leads to movement of both lobes, and the loop region between Asp189 and Thr198 with high temperature factors seems to be relatively flexible, which induces opening and closure of the catalytic cleft (Hamada et al., 1996 ▸).

Previously, we isolated the bacterial strain Serratia sp. FS14 from the stem of diseased Atractylodes macrocephala Koidz and found that it could secrete a thermostable protease (Zheng et al., 2011 ▸). A 50 kDa protease from the supernatant culture of Serratia sp. FS14 was identified as a serralysin and a thermostability assay showed that it retained 40% of its protease activity after pretreatment at 363 K for 10 min.

To dissect the thermostable enzymatic properties of serralysin from Serratia sp. FS14 at the structural level, we determined the crystal structure of serralysin from Serratia sp. FS14 at the atomic resolution of 1.1 Å.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Purification and protease-activity assay

Unless otherwise noted, all purification steps were carried out at 277 K.

Serratia sp. FS14 (Zheng et al., 2011 ▸) cells were grown in Luria–Bertani (LB) broth (1.0% tryptone, 0.5% yeast extract, 1.0% NaCl pH 7.0) on a rotary shaker at 180 rev min−1 at 301 K for 12 h and transferred to 1 l LB medium at 301 K for a further 24 h. The culture was centrifuged at 16 000g for 30 min; the supernatant was passed through 0.45 and 0.22 µm filters and was then precipitated by ammonium sulfate at 80% saturation. The precipitate was collected after centrifugation at 24 000g for 30 min and dissolved in 20 ml 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer pH 7.0. After centrifugation at 24 000g for 30 min, the supernatant was collected, diluted with an equal volume of 3 M ammonium sulfate and loaded onto a CM Sephadex C-50 hydrophobic interaction chromatography column pre-equilibrated with buffer consisting of 1.5 M ammonium sulfate, 50 mM sodium phosphate pH 7.0. The column was eluted with a linear gradient of 1.5–0 M ammonium sulfate in 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer pH 7.0. The fractions with thermostable protease activity were pooled and dialyzed against 200 volumes of a solution consisting of 20 mM Tris–HCl buffer pH 8.0 for 12 h and then applied onto a DEAE Sephadex A-50 anion-exchange chromatography column pre-equilibrated with 20 mM Tris–HCl buffer pH 8.0 and eluted with a linear gradient of 0–1 M NaCl in 20 mM Tris–HCl buffer pH 8.0. The fractions with thermostable protease activity were then concentrated and applied onto a Superdex 200 column (30 × 1.0 cm) which had been pre-equilibrated with 20 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 0.3 M NaCl. The protease was finally eluted with the same buffer. The purified protease was inspected on 10% SDS–PAGE and stored at 277 K for further crystallization and protease-activity assays. Protease activity was determined using a reaction mixture consisting of 50 µg casein and 5 µg purified protein in 50 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 20 mM NaCl buffer at 310 K for 10 min using the method described by Saleemuddin et al. (1980 ▸).

2.2. Crystallization and data collection

After purification, the protein samples were concentrated to 20 mg ml−1. Crystals suitable for data processing were grown in 24-well plates by the hanging-drop vapour-diffusion method by mixing 1 µl protein solution with 1 µl reservoir solution and equilibrating against reservoir solution consisting of 0.1 M ammonium sulfate, 0.1 M sodium citrate pH 6.3, 30%(w/v) polyethylene glycol (PEG) 8000. The best crystals were obtained at 289 K in 4 d.

Crystals were looped out from the crystallization drop and transferred into fresh mother liquor with 10%(w/v) glycerol as a cryoprotectant for several seconds. The crystal was then flash-cooled in liquid nitrogen. Diffraction data were collected on beamline BL17U at Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility (SSRF), Shanghai, People’s Republic of China. The raw data were processed using the XDS package (Kabsch, 2010 ▸). Data-collection and processing statistics are summarized in Table 1 ▸.

Table 1. Data collection and processing.

Values in parentheses are for the outer shell.

| Diffraction source | BL17U, SSRF |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.9792 |

| Temperature (K) | 100 |

| Detector | ADSC Q315r |

| Crystal-to-detector distance (mm) | 120 |

| Rotation range per image (°) | 1.0 |

| Total rotation range (°) | 360 |

| Exposure time per image (s) | 1.0 |

| Space group | P212121 |

| a, b, c (Å) | 42.3, 105.4, 151.1 |

| Mosaicity (°) | 0.18 |

| Resolution range (Å) | 20–1.1 (1.2–1.1) |

| Total No. of reflections | 1915565 (423363) |

| No. of unique reflections | 273151 (62101) |

| Completeness (%) | 99.5 (99.5) |

| R merge † (%) | 9.1 (93.2) |

| R meas ‡ (%) | 9.9 (100.9) |

| 〈I/σ(I)〉 | 10.96 (2.03) |

| Overall B factor from Wilson plot (Å2) | 13.6 |

R

merge =

, where I

i(hkl) and 〈I(hkl)〉 are the observed intensity of the ith measurement and the mean intensity of the reflection with indices hkl, respectively.

, where I

i(hkl) and 〈I(hkl)〉 are the observed intensity of the ith measurement and the mean intensity of the reflection with indices hkl, respectively.

R

meas =

.

.

2.3. Structure determination and refinement

The molecular-replacement method was used to solve the structure of serralysin from Serratia sp. FS14 using the structure of the 50 kDa metalloprotease SMP from S. marcescens (PDB entry 1sat; Baumann, 1994 ▸) as a template. Molecular replacement was performed using Phaser (McCoy et al., 2007 ▸), the model was subsequently manually adjusted and checked with Coot (Emsley et al., 2010 ▸) and refinement was carried out using REFMAC5 (Murshudov et al., 2011 ▸) and PHENIX with isotropic B factors (Adams et al., 2010 ▸). Structure-solution and refinement statistics are summarized in Table 2 ▸.

Table 2. Structure solution and refinement.

Values in parentheses are for the outer shell.

| PDB code | 5d7w |

| Resolution range (Å) | 20–1.1 |

| Total No. of atoms | 3474 |

| No. of reflections used | 259368 |

| R work (%) | 16.19 |

| R free (%) | 17.553 |

| R.m.s.d., bond lengths (Å) | 0.0064 |

| R.m.s.d., bond angles (°) | 1.085 |

| Average B factors (Å2) | |

| Protein | 12.74 |

| Water | 27.66 |

| Ramachandran plot (%) | |

| Favoured | 96.25 |

| Allowed | 3.75 |

| Outliers | 0 |

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Purification of the thermostable serralysin

By monitoring the protease activity during purification, the thermostable serralysin was purified from the culture supernatant of Serratia sp. FS14 in several steps. A protease-activity assay showed that this serralysin has about 40% protease activity remaining after pretreatment at 363 K for 10 min. The serralysin is secreted in a large amount, with a yield of 10 mg purified protein per litre of culture supernatant.

3.2. Overall structure

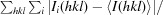

The crystal structure of serralysin from Serratia sp. FS14 was solved and refined to a crystallographic R factor of 0.1619 at 1.1 Å resolution (Table 2 ▸). Serralysin from Serratia sp. FS14 is an elongated molecule with approximate dimensions of 90 × 35 × 40 Å. It is comprised of an extended N-terminal tail (residues 3–20) contacting the C-terminus and two main domains: the N-terminal proteolytic domain (residues 21–251) and the ‘parallel β-roll’ C-terminal domain (residues 252–471) (Fig. 1 ▸).

Figure 1.

Cartoon view of the overall structure of serralysin, coloured according to secondary-structure element. Calcium ions (Ca1–Ca7) are shown as green spheres. The zinc ion is shown as a grey sphere with its ligands in yellow.

Furthermore, the N-terminal domain is divided into an upper N-lobe consisting of a five-stranded β-sheet and three α-helices and a lower C-lobe consisting mostly of irregular structure with an α-helix and three short 310-helices. The lobes form a large flap-shaped active-site cleft hosting a zinc ion at the bottom. The β-sandwich C-terminal domain consists of 16 β-strands, three short 310-helices and irregular structure, characterized by an elongated parallel β-roll binding seven calcium ions.

3.3. Structural comparison with serralysin homologues

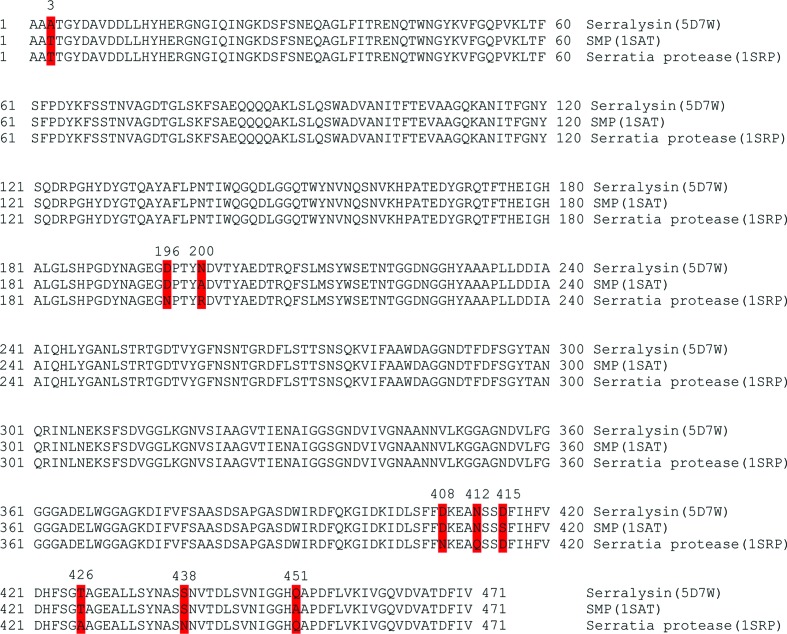

The sequence of serralysin from Serratia sp. FS14 shares 98% identity with two homologues for which structures have been determined (Fig. 2 ▸). The overall structure of serralysin reported here (PDB entry 5d7w) shares a similar fold with its homologues, such as SMP (serralysin) from S. marcescens (PDB entry 1sat; Baumann, 1994 ▸; r.m.s.d. of 0.18 Å for 408 Cα atoms) and Serratia protease (serralysin) from Serratia sp. E-15 (PDB entry 1srp; Hamada et al., 1996 ▸; r.m.s.d. of 0.20 Å for 407 Cα atoms).

Figure 2.

Amino-acid sequence aligment of the serralysins from Serratia sp. FS14 (PDB entry 5d7w), S. marcescens (SMP; PDB entry 1sat) and Serratia sp. E-15 (Serratia protease; PDB entry 1srp). Identical residues are shown on a white background and differences are highlighted in red.

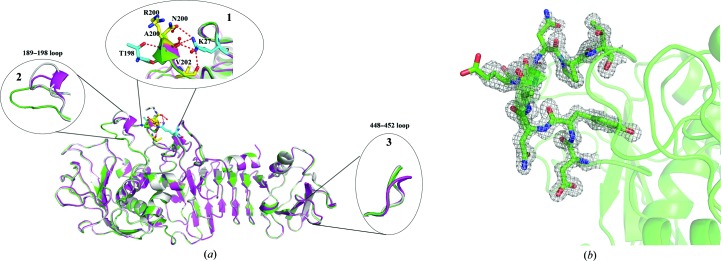

Sequence alignment showed that only nine residues differ among the three Serratia serralysins (Fig. 2 ▸). Nevertheless, several structure differences can obviously be observed. One obvious difference is residue Asn200 (Arg in Serratia protease and Ala in SMP), which forms hydrogen bonds to Lys27; at the same time Lys27 also forms hydrogen bonds to the carbonyl groups of Asn200 and Val202 (labelled 1 in Fig. 3 ▸ a). These interactions are not present in the other Serratia serralysins. The interactions between Lys27 and Asn200 and Val202 may stabilize the protein. This phenomenon has also been observed recently by Zhang and coworkers, who introduced interactions between the N-terminal helix and the RTX domain, leading to an increase in the thermal and chemical stability, of serralysin from S. marcescens (Zhang et al., 2015 ▸). Additionally, the 189–198 loop with a short 310-helix in serralysin from Serratia sp. FS14 protrudes further away from the molecular surface than the 189–198 loop in SMP or Serratia protease, restricting the entrance to the active-site cavity. This loop is ordered in the Serratia sp. FS14 structure and has relatively high B factors (28.95 Å2) compared with the whole protein chain (13.37 Å2) (labelled 2 in Fig. 3 ▸ a; Fig. 3 ▸ b). The serralysin reported here (Fig. 3 ▸ a, magenta) has a wider active-site cavity and shows a more open conformation than SMP (Fig. 3 ▸ a, green) and Serratia protease (Fig. 3 ▸ a, grey). A previous study showed that this loop is disordered in the crystal structures of the free proteases but becomes ordered upon ligand binding. Asn191 in this loop in SMP moves 3.6 Å to make hydrogen bonds to the P3 residue of the ligand to close the entrance to the active cleft. Asn191 in serralysin from Serratia sp. FS14 moves more than 9.0 Å towards the molecular surface compared with SMP, and the movement of the Cα atom of Asn191 may restrict the substrate or ligand specificity. The more open active-site cleft and entrance of serralysin reported here may be responsible for the substrate specificity of Serratia sp. FS14 serralysin.

Figure 3.

(a) Comparison of the serralysins from Serratia sp. FS14 (PDB entry 5d7w; magenta), S. marcescens (PDB entry 1sat; green) and Serratia sp. E-15 (PDB entry 1srp; grey). The significant distinct positions are magnified. (b) The electron density of the 189–198 loop of the serralysin from Serratia sp. FS14 showed that this loop was ordered in the structure. Structural superimpositions were performed with PyMOL.

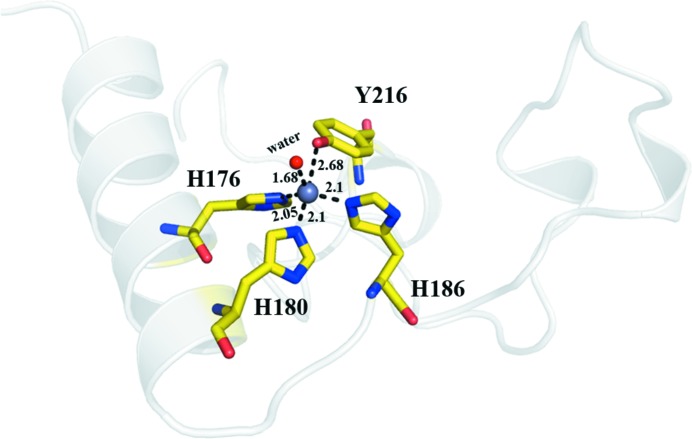

Other than the above significant distinctions, another difference is observed in the zinc ligation. Similar to its homologues, the active-site zinc ion of serralysin from Serratia sp. FS14 is positioned at the bottom of the active-site cleft by five zinc ligands arranged in a distorted trigonal bipyramidal geometry, but the distance between the zinc and the hydroxyl O atom of Tyr216 is 2.66 Å, which makes the coordinate bond more strong than that in its homologues (2.75 Å in SMP and 3.05 Å in Serratia protease; Fig. 4 ▸). This may make the active site more stable in Serratia sp. FS14 serralysin than in the other serralysins, resulting in the thermostability of the protease.

Figure 4.

The active site of Serratia sp. FS14 serralysin. The zinc ion is coordinated by His176, His180, His186, Tyr216 and a water molecule, forming a distorted trigonal bipyramidal catalytic active centre.

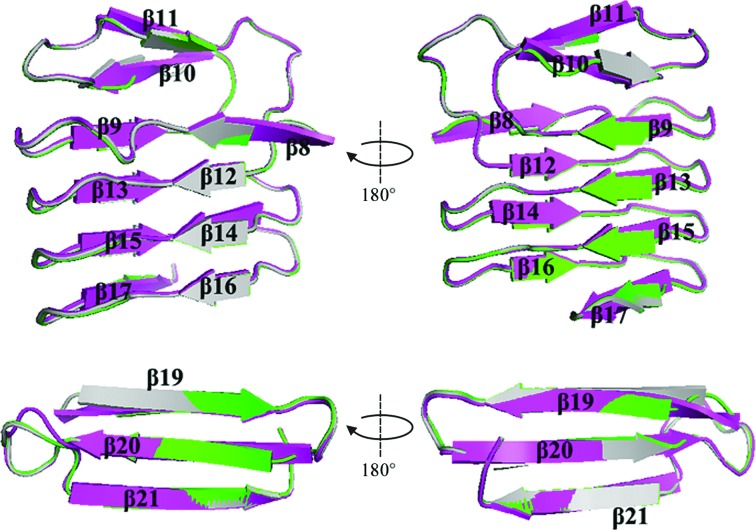

Furthermore, as a result of the very high resolution, a few distinct differences are located in the β-strand sandwich domain. This domain mainly consists of 16 β-strands and is subdivided into two regions: an N-terminal region consisting of 13 β-strands (β6–β18) and a C-terminal region consisting of three antiparallel β-sheets (β19–β21). In the N-terminal region of SMP or Serratia protease, each of the β-strands is formed by only three amino-acid residues in an untwisted manner. However, in that of serralysin from Serratia sp. FS14 the β-sheets (including β8, β9, β10, β11, β13, β14, β15, β17, β19, β20 and β21) are longer and are formed by four or five amino-acid residues; in particular, β8, β10 and β17 are formed in a more twisted manner (Fig. 5 ▸). A characteristic of serralysin and its homologues is the presence of multiple calcium ions binding in the RTX domain; the binding of calcium ions facilitates the folding of serralysins and stabilizes the protein (Baumann, 1994 ▸; Baumann et al., 1993 ▸). Comparison of the distances between the calcium ions and their coordinating ligands revealed that the binding affinity for calcium ions in Serratia sp. FS14 serralysin is relatively lower than that in the other two Serratia serralysins; this difference may also contribute to the thermostability of our serralysin (Table 3 ▸).

Figure 5.

Comparison of the ‘parallel β-roll’ C-terminal domains of serralysin from Serratia sp. FS14 (PDB entry 5d7w; magenta), S. marcescens (PDB entry 1sat; green) and Serratia sp. E-15 (PDB entry 1srp; grey). The β-sheets in the C-terminal domain are labelled.

Table 3. Distances between the Ca2+ ions in the parallel β-roll of the serralysin family and their ligands.

| Distance (Å) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Serralysin | SMP | Serratia protease | |

| Distance between Ca1 and | |||

| Arg253 O | 2.29 | 2.30 | 2.28 |

| Gly255 O | 2.37 | 2.36 | 2.46 |

| Thr257 O | 2.46 | 2.36 | 2.46 |

| Asp285 OD1 | 2.46 | 2.55 | 2.48 |

| Asp285 OD2 | 2.53 | 2.56 | 2.60 |

| Gly287 O | 2.30 | 2.31 | 2.38 |

| Asp290 OD1 | 2.31 | 2.41 | 2.31 |

| Distance between Ca2 and | |||

| Gly288 O | 2.33 | 2.38 | 2.49 |

| Asp290 OD2 | 2.37 | 2.44 | 2.47 |

| Thr327 O | 2.34 | 2.36 | 2.52 |

| Glu329 OE1 | 2.48 | 2.62 | 2.55 |

| Glu329 OE2 | 2.46 | 2.58 | 2.74 |

| Wat543/72/550 | 2.42 | 2.40 | 2.55 |

| Wat541/42/524 | 2.36 | 2.35 | 2.67 |

| Distance between Ca3 and | |||

| Gly334 O | 2.34 | 2.33 | 2.28 |

| Gly336 O | 2.36 | 2.38 | 2.53 |

| Asp338 OD2 | 2.37 | 2.50 | 2.61 |

| Gly351 O | 2.33 | 2.32 | 2.51 |

| Ala353 O | 2.31 | 2.38 | 2.40 |

| Asp356 OD1 | 2.40 | 2.47 | 2.38 |

| Distance between Ca4 and | |||

| Asn343 O | 2.35 | 2.31 | 2.43 |

| Ala345 O | 2.32 | 2.36 | 2.51 |

| Asn347 ND1 | 2.35 | 2.39 | 2.53 |

| Gly360 O | 2.33 | 2.40 | 2.49 |

| Gly362 O | 2.28 | 2.33 | 2.39 |

| Asp365 OD1 | 2.41 | 2.49 | 2.63 |

| Distance between Ca5 and | |||

| Gly352 O | 2.42 | 2.32 | 2.39 |

| Gly354 O | 2.39 | 2.43 | 2.62 |

| Asp356 OD2 | 2.35 | 2.46 | 2.41 |

| Gly369 O | 2.38 | 2.40 | 2.50 |

| Ala371 O | 2.29 | 2.27 | 2.32 |

| Asp374 OD1 | 2.38 | 2.48 | 2.59 |

| Distance between Ca6 and | |||

| Gly361 O | 2.32 | 2.40 | 2.51 |

| Gly363 O | 2.40 | 2.35 | 2.51 |

| Asp365 OD2 | 2.26 | 2.40 | 2.19 |

| Asp383 O | 2.21 | 2.20 | 2.25 |

| Asp390 OD1 | 2.42 | 2.54 | 2.51 |

| Wat173/561/604 | 2.72 | 2.81 | 2.72 |

| Distance between Ca7 and | |||

| Gly370 O | 2.43 | 2.47 | 3.22 |

| Gly372 O | 2.38 | 2.46 | 2.65 |

| Asp374 OD2 | 2.24 | 2.44 | 2.52 |

| Asp400 OD1 | 2.55 | 2.55 | 2.60 |

| Asp400 OD2 | — | — | 3.17 |

| Wat99/629/— | 2.37 | 2.29 | — |

| Wat39/566/527 | 2.78 | 2.66 | 3.18 |

The crystal structure of serralysin from Serratia sp. FS14 represents the highest resolution serralysin-family structure available to date and will be used as a model providing detailed information for future studies.

Supplementary Material

PDB reference: serralysin, 5d7w

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31100028, 31170686 and 31400055), the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK20140690) and the Youth Science and Technology Innovation Fund of Nanjing Agricultural University (KJ2013027). We are grateful to the staff of beamline BL17U at SSRF, Shanghai, People’s Republic of China for their assistance.

References

- Adams, P. D. et al. (2010). Acta Cryst. D66, 213–221.

- Aiyappa, P. & Harris, J. (1976). Mol. Cell. Biochem. 13, 95–100. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Baumann, U. (1994). J. Mol. Biol. 242, 244–251. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Baumann, U., Bauer, M., Létoffé, S., Delepelaire, P. & Wandersman, C. (1995). J. Mol. Biol. 248, 653–661. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Baumann, U., Wu, S., Flaherty, K. M. & McKay, D. B. (1993). EMBO J. 12, 3357–3364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Berman, H. M., Westbrook, J., Feng, Z., Gilliland, G., Bhat, T., Weissig, H., Shindyalov, I. N. & Bourne, P. E. (2000). Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 235–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Braun, V. & Schmitz, G. (1980). Arch. Microbiol. 124, 55–61. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Braunagel, S. C. & Benedik, M. J. (1990). Mol. Gen. Genet. 222, 446–451. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.-C., Shipley, G. L., Ball, T. K. & Benedik, M. J. (1992). Mol. Microbiol. 6, 643–651. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Daborn, P. J., Waterfield, N., Blight, M. A. & Ffrench-Constant, R. H. (2001). J. Bacteriol. 183, 5834–5839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Delepelaire, P. & Wandersman, C. (1989). J. Biol. Chem. 264, 9083–9089. [PubMed]

- Emsley, P., Lohkamp, B., Scott, W. G. & Cowtan, K. (2010). Acta Cryst. D66, 486–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Givskov, M., Olsen, L. & Molin, S. (1988). J. Bacteriol. 170, 5855–5862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hamada, K., Hata, Y., Katsuya, Y., Hiramatsu, H., Fujiwara, T. & Katsube, Y. (1996). J. Biochem. 119, 844–851. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kabsch, W. (2010). Acta Cryst. D66, 125–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kida, Y., Inoue, H., Shimizu, T. & Kuwano, K. (2007). Infect. Immun. 75, 164–174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lakshmi Bhargavi, P. & Prakasham, R. (2013). Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 61, 479–486. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Liang, T.-W., Kuo, Y.-H., Wu, P.-C., Wang, C.-L., Dzung, N. A. & Wang, S.-L. (2010). J. Chin. Chem. Soc. 57, 857–863.

- Marty, K. B., Williams, C. L., Guynn, L. J., Benedik, M. J. & Blanke, S. R. (2002). Infect. Immun. 70, 1121–1128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- McCoy, A. J., Grosse-Kunstleve, R. W., Adams, P. D., Winn, M. D., Storoni, L. C. & Read, R. J. (2007). J. Appl. Cryst. 40, 658–674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Miyata, K., Maejima, K., Tomoda, K. & Isono, M. (1970). Agric. Biol. Chem. 34, 310–318.

- Miyata, K., Tomoda, K. & Isono, M. (1971). Agric. Biol. Chem. 35, 460–467.

- Monreal, J. & Reese, E. T. (1969). Can. J. Microbiol. 15, 689–696. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Morihara, K. & Okuda, K. (1992). Seikagaku, 64, 149–159. [PubMed]

- Murshudov, G. N., Skubák, P., Lebedev, A. A., Pannu, N. S., Steiner, R. A., Nicholls, R. A., Winn, M. D., Long, F. & Vagin, A. A. (2011). Acta Cryst. D67, 355–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Petersen, L. M. & Tisa, L. S. (2014). J. Bacteriol. 196, 3923–3936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Pineda-Castellanos, M. L., Rodríguez-Segura, Z., Villalobos, F. J., Hernández, L., Lina, L. & Nuñez-Valdez, M. E. (2015). Pathogens, 4, 210–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Saleemuddin, M., Ahmad, H. & Husain, A. (1980). Anal. Biochem. 105, 202–206. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sarker, M. R. & Cornelis, G. R. (1997). Mol. Microbiol. 23, 410–411. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Shanks, R. M., Stella, N. A., Hunt, K. M., Brothers, K. M., Zhang, L. & Thibodeau, P. H. (2015). Infect. Immun. 83, 2907–2916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L., Morrison, A. J. & Thibodeau, P. H. (2015). PLoS One, 10, e0138419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Zheng, C.-C., Wang, C.-L., Fu, L., Wang, W.-W. & Xu, D.-Q. (2011). Microbiology/Weishengwuxue Tongbao, 38, 228–236.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

PDB reference: serralysin, 5d7w