The structural elucidation of a unique lactone cycloisomerase involved in pectin degradation is reported.

Keywords: d-galactaro-1,4-lactone cycloisomerase; d-galacturonate; pectin; Agrobacterium tumefaciens

Abstract

Pectin is found in the cell wall of plants and is often discarded as waste. A number of research groups are interested in redirecting this biomass waste stream for the production of fuel and bulk chemicals. The primary monomeric subunit of this polysaccharide is d-galacturonate, a six-carbon acid sugar that is degraded in a five-step pathway to central metabolic intermediates by some bacteria, including Agrobacterium tumefaciens. In the third step of the pathway, d-galactaro-1,4-lactone is converted to 2-keto-3-deoxy-l-threo-hexarate by a member of the mandelate racemase subgroup of the enolase superfamily with a novel activity for the superfamily. The 1.6 Å resolution structure of this enzyme was determined, revealing an overall modified (β/α)7β TIM-barrel domain, a hallmark of the superfamily. d-Galactaro-1,4-lactone was manually docked into the active site located at the interface between the N-terminal lid domain and the C-terminal barrel domain. On the basis of the position of the lactone in the active site, Lys166 is predicted to be the active-site base responsible for abstraction of the α proton. His296 on the opposite side of the active site is predicted to be the general acid that donates a proton to the β carbon as the lactone ring opens. The lactone ring appears to be oriented within the active site by stacking interactions with Trp298.

1. Introduction

Pectin is found in the cell wall of plants and is often discarded as waste in sugar-beet pulp, apple pomace and citrus peel (Richard & Hilditch, 2009 ▸). A number of research groups are interested in redirecting this biomass waste stream for the production of fuel and bulk chemicals (Benz et al., 2014 ▸). The primary monomeric subunit of this polysaccharide is d-galacturonate, a six-carbon acid sugar that is degraded in a five-step pathway to central metabolic intermediates by some bacteria, including Agrobacterium tumefaciens.

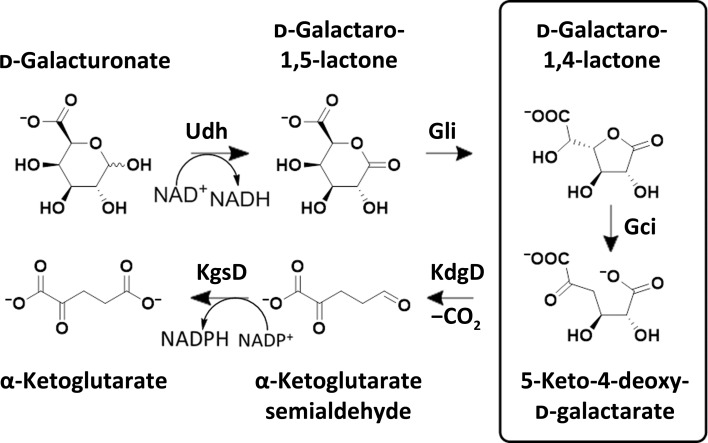

A. tumefaciens can use d-galacturonate as a sole source of carbon in a five-step pathway (Fig. 1 ▸), in which the first step is the oxidation of d-galacturonate by an NAD+-dependent hexuronate dehydrogenase to form d-galactaro-1,5-lactone. Next, d-galactaro-1,5-lactone isomerase (GCI) converts the 1,5-lactone to d-galactaro-1,4-lactone, which is then ring-opened by d-galactaro-1,4-cycloisomerase to form 2-keto-3-deoxy-l-threo-hexarate (equivocally 5-keto-4-deoxy-d-galactarate or 5-keto-4-deoxy-d-glucarate; KDG). KDG undergoes dehydration and decarboxylation to form α-ketoglutarate semialdehyde, which is oxidized to α-ketoglutarate, an intermediate in the tricarboxylic acid cycle (Andberg et al., 2012 ▸; Bouvier et al., 2014 ▸; Taberman et al., 2014 ▸).

Figure 1.

Reactions in the five-step pathway for d-galacturonate assimilation.

The cycloisomerization reaction of d-galactaro-1,4-lactone to 2-keto-3-deoxy-l-threo-hexarate is catalysed by a member of the mandelate racemase subgroup of the mechanistically diverse enolase superfamily. With the exception of the racemization of mandelate, all known members of the subgroup dehydrate acyclic acid sugars; in both cases the first step in the reaction is the abstraction of a proton α to the carboxylate group of the substrate, followed by the stabilization of an enediolate intermediate by a divalent metal cation in the active site. During the subsequent processing of the intermediate, the C3 hydroxyl group departs as a water molecule (Andberg et al., 2012 ▸; Gerlt et al., 2011 ▸). In the case of A. tumefaciens d-galactaro-1,5-lactone isomerase (AtGCI) the substrate is a lactone; thus, instead of elimination of water from the carbon β to the carboxylate the cleavage of the carbon–oxygen bond at this position yields the acyclic diacid (Fig. 1 ▸). This activity is unique to the mandelate racemase subgroup.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Macromolecule production

The gene encoding AtGCI (UniProt accession A9CEQ8, gene locus Atu3139) was amplified via the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) from genomic DNA isolated from A. tumefaciens strain C58 using Platinum Pfx DNA Polymerase (Invitrogen). The PCR mixture consisted of 5 µl 10× Pfx Amplification Buffer (0.3 mM dNTPs, 1 mM MgSO4), primers at 0.3 µM each (Table 1 ▸), one unit of Pfx DNA Polymerase and 50 ng of genomic DNA in a total volume of 50 µl. The amplification was performed using a PTC-200 gradient cycler (MJ Research) with the following cycling profile: 94°C for 5 min followed by 35 cycles of 94°C for 15 s, 60°C for 30 s and 68°C for 1 min 30 s followed by a final extension step at 68°C for 10 min. The amplified gene was cloned into the pET-17b vector using conventional cloning methods (PCR amplification followed by cloning into multiple cloning restriction sites in the vector). AtGCI was expressed heterologously without a tag by growing 3 l of Escherichia coli strain BL21(DE3) cells in LB supplemented with 100 µg ml−1 ampicillin at 30°C while the sample was shaken at 220 rev min−1 for 48 h. IPTG was not used to induce expression.

Table 1. Macromolecule-production information.

| Source organism | A. tumefaciens strain C58 |

| DNA source | A. tumefaciens strain C58 |

| Forward primer | GAAAAACGGGAGGGGACATATGAAAATCACGGCGGTGC |

| Reverse primer | CTCAGTTTTTCTCTCTCGAGTTCGCTCATGGGTCTGGCATC |

| Cloning vector | pET-17b |

| Expression vector | pET-17b |

| Expression host | E. coli BL21(DE3) |

| Complete amino-acid sequence of the construct produced | MKITAVRTHLLEHRLDTPFESASMRFDRRAHVLVEIECDDGTVGWGECLGPARPNAAVVQAYSGWLIGQDPRQTEKIWAVLYNALRDQGQRGLSLTALSGIDIALWDIKGKHYGASISMLLGGRWRESVRAYATGSFKRDNVDRVSDNASEMAERRAEGFHACKIKIGFGVEEDLRVIAAVREAIGPDMRLMIDANHGYTVTEAITLGDRAAGFGIDWFEEPVVPEQLDAYARVRAGQPIPVAGGETWHGRYGMWQALSAGAVDILQPDLCGCGGFSEIQKIATLATLHGVRIVPHVWGTGVQIAAALQFMAAMTPDPVRVNPIEPIMEFDRTHNPFRQAVLREPLEAVNGVVTIPDGPGLGIEINRDALTEFRMPDP |

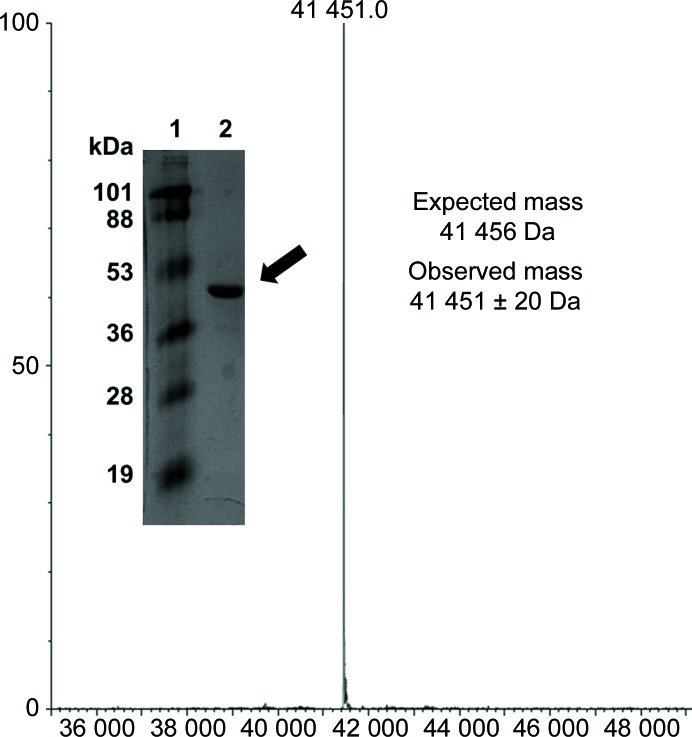

The cells were harvested by centrifugation (5000g at 4°C) and resuspended in 75 ml low-salt buffer (20 mM Tris pH 7.9, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2). The cells were lysed by sonication and the lysate was cleared by centrifugation (30 000g at 4°C) to remove cell debris. The supernatant was loaded onto a 125 ml Dowex DEAE column equilibrated with 625 ml low-salt buffer. The column was washed with 625 ml low-salt buffer and the protein was eluted with a linear 1875 ml gradient of 0–50% high-salt buffer (20 mM Tris pH 7.9, 1 M NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2) followed by 250 ml 100% high-salt buffer. The purity was confirmed by SDS–PAGE. Fractions containing protein of the correct molecular weight were pooled and loaded onto a 20 ml Q Sepharose column equilibrated with 100 ml low-salt buffer. The column was washed with 100 ml low-salt buffer and the protein was eluted with a linear 600 ml gradient of 0–50% high-salt buffer. The purity was checked by SDS–PAGE (Fig. 2 ▸). Fractions containing protein of the correct molecular weight were pooled and dialyzed in low-salt buffer. The total yield was 171 mg from 3 l of culture. The mass of the polypeptide was confirmed by mass spectrometry (Fig. 2 ▸). The protein preparation (>90% purity) was flash-cooled by dropwise addition to liquid N2 and transferred to a cryogenic vial for storage at −80°C.

Figure 2.

Grayscale photo of an SDS–PAGE gel and mass-spectrometry chromatogram of purified AtGCI. Protein ladder is in lane 1 and purified AtGCI (as indicated by the arrow) is in lane 2.

2.2. Crystallization

Crystallization of AtGCI was accomplished by sitting-drop vapor diffusion in 96-well Intelli-Plates (Art Robbins) stored at 20°C. Crystallization drops were assembled using 0.5 µl precipitant solution combined with 0.5 µl protein solution (11.5 mg ml−1 in 20 mM Tris pH 7.9, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2) and were equilibrated against 70 µl reservoir solution. Crystallization screening used the commercial screens MCSG1–4 (Microlytic). AtGCI crystallized in two crystal forms. The first crystal form consisted of dodecahedron-shaped crystals obtained from a solution consisting of 0.2 M CaCl2, 0.1 M HEPES pH 7.5, 28%(w/v) PEG 400; crystals grown from this solution could be directly flash-cooled without additional cryoprotectant. These crystals gave the structure deposited as PDB entry 4ggb. The second crystal form consisted of tetragonal bipyramid-shaped crystals from a solution consisting of 0.2 M calcium acetate, 0.1 M imidazole–HCl pH 8.0, 10%(w/v) PEG 8000 and were cryoprotected in reservoir solution supplemented with 20%(v/v) glycerol prior to flash-cooling. These crystals gave the structure deposited as PDB entry 4hpn. Crystals were mounted in nylon loops before flash-cooling and storage in liquid N2.

2.3. Data collection and processing

X-ray diffraction data were collected at 110 K from single crystals on LRL-CAT beamline 31-ID at the Advanced Photon Source, Argonne National Laboratory with a Rayonix 225 HE detector using a wavelength of 0.97931 Å and a crystal-to-detector distance of 119 mm. The data were processed using MOSFLM (Leslie, 1992 ▸) and SCALA (Evans, 2006 ▸). The final data-collection and processing statistics are given in Table 2 ▸.

Table 2. Data collection and processing.

Values in parentheses are for the outer shell.

| PDB code | 4ggb | 4hpn |

|---|---|---|

| Rotation range per image (°) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Total rotation range (°) | 149 | 180 |

| Exposure time per image (s) | 1 | 1 |

| Space group | I422 | I422 |

| a, b, c (Å) | 132.2, 132.2, 95.5 | 121.1, 121.1, 128.4 |

| Mosaicity (°) | 1.5 | 0.52 |

| Resolution range (Å) | 93.5–2.0 (2.11–2.00) | 25.7–1.6 (1.69–1.60) |

| Total No. of reflections | 274879 (24028) | 918003 (131597) |

| No. of unique reflections | 28770 (4128) | 62863 (9078) |

| Completeness (%) | 99.9 (99.6) | 100.0 (100.0) |

| Multiplicity | 9.6 (5.8) | 14.6 (14.5) |

| 〈I/σ(I)〉 | 15.1 (2.5) | 14.4 (3.2) |

| R r.i.m. | 0.097 (0.745) | 0.134 (0.932) |

| Overall B factor from Wilson plot (Å2) | 25.8 | 11.7 |

2.4. Structure solution and refinement

The structures were determined by molecular replacement using Phaser (McCoy, 2007 ▸) within PHENIX (Adams et al., 2004 ▸). The structure of an enolase superfamily member of unknown function (PDB entry 3sjn; Enzyme Function Initiative, unpublished work) from Shewanella pealeana showed the highest sequence identity to AtGCI (33%) and was used as the search model to obtain initial phases for the structure deposited as PDB entry 4ggb. PDB entry 4ggb was then used in a second round of molecular replacement to phase the structure deposited as PDB entry 4hpn. The structures were refined with iterative cycles of manual building and modeling in Coot (Emsley et al., 2010 ▸) and refinement in PHENIX. TLS refinement (Winn et al., 2001 ▸) was included in the final rounds of refinement with domains selected by the automated procedure within PHENIX (Adams et al., 2011 ▸). The final model-refinement statistics are given in Table 3 ▸.

Table 3. Structure solution and refinement.

Values in parentheses are for the outer shell.

| PDB code | 4ggb | 4hpn |

|---|---|---|

| Resolution range (Å) | 38.7–2.0 (2.07–2.00) | 25.7–1.6 (1.62–1.60) |

| Completeness (%) | 98.7 (99.0) | 100.0 (100.0) |

| No. of reflections, working set | 28435 (2675) | 62856 (2553) |

| No. of reflections, test set | 1446 (139) | 3190 (158) |

| Final R cryst (%) | 19.6 (25.0) | 13.8 (20.0) |

| Final R free (%) | 23.4 (32.9) | 16.1 (24.6) |

| No. of non-H atoms | ||

| Protein | 2675 | 2962 |

| Water | 186 | 479 |

| Total | 2869 | 3449 |

| R.m.s. deviations | ||

| Bonds (Å) | 0.012 | 0.020 |

| Angles (°) | 1.15 | 1.67 |

| Average B factors (Å2) | ||

| Protein | 21.8 | 14.1 |

| Ion (Ca2+) | 49.5 | 10.6 |

| Water | 24.7 | 27.3 |

| Ramachandran plot | ||

| Most favored (%) | 97.4 | 97.4 |

| Allowed (%) | 2.6 | 2.6 |

3. Results and discussion

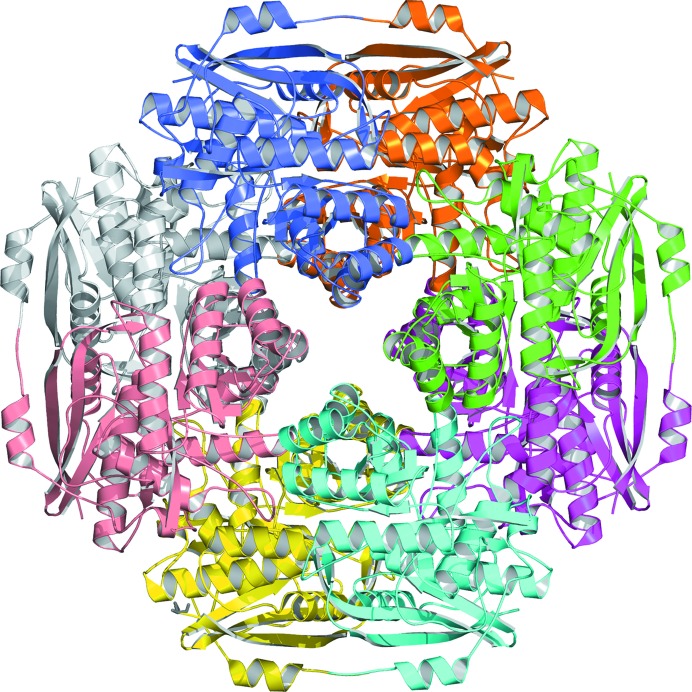

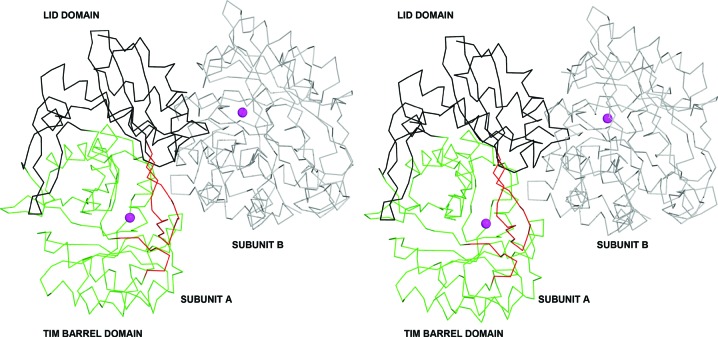

d-Galactaro-1,4-lactone cycloisomerase from A. tumefaciens (AtGCI) was expressed and purified using a tagless construct to overcome the poor solubility and yield associated with the N-terminally six-histidine-tagged construct. The protein crystallized in two forms, both in space group I422 and with a single polypeptide chain per asymmetric unit. Examination of the crystal packing indicates that AtGCI is a homo-octamer, which is a common oligomeric state for enolase-superfamily members (Fig. 3 ▸). The protein has the typical enolase fold with two domains: a (β/α)7β TIM-barrel domain and a lid domain (Fig. 4 ▸). The active site is in the interface between the two domains, with the TIM barrel contributing side-chain functionalities for binding the divalent cation required for activity and the lid domain shielding the catalytic site from bulk solvent and providing additional ligand-binding specificity. Additional sequestration of the catalytic site is provided by a neighboring subunit (Fig. 4 ▸). A search for structural homologs using the secondary-structure matching (SSM) server (Krissinel & Henrick, 2004 ▸) yielded a number of enolase-superfamily members of unknown function in the 25–35% sequence-identity range, with the highest match to Spea_3858 from S. pealeana (PDB entry 3sjn; 33% identity, 1.23 Å r.m.s.d. on 343 Cα atoms) with bound Mg2+. The closest homolog with a bound organic ligand is BB4687 from Bordetella bronchiseptica RB50 with bound Mg2+ and meso-xylarate (PDB entry 3ozm; 31% identity, 1.62 Å r.m.s.d. on 354 Cα atoms; A. A. Fedorov, E. V. Fedorov, D. Wichelecki, J. A. Gerlt & S. C. Almo, unpublished work). Activity data have not been reported for this homolog, so BB4687 remains an enolase-superfamily member of unknown function.

Figure 3.

Ribbon representation of the homo-octamer (α8) of AtGCI generated by applying crystallographic symmetry (I422) to the single subunit per asymmetric unit. The view is looking down the fourfold axis. Each active-site pocket (eight in total) contains contributions from two protomers; for example, the green and magenta ribbons share residues for their respective active-site pockets across a twofold axis.

Figure 4.

Wall-eyed stereoview of the two protomers contributing to each catalytic site shown as a Cα trace (PDB entry 4hpn). Subunit A is shown in black (lid domain; 1–127 and 341–378), green (TIM-barrel domain; 128–340) and red (loops disordered in 4ggb; 12–30 and 136–142). Subunit B is shown in gray and the active-site cation is shown as a magenta sphere.

The two crystal forms (PDB entries 4ggb and 4hpn) are similar (0.80 Å r.m.s.d. on 339 Cα atoms), with the largest deviations owing to a difference (up to ∼3 Å for interdomain Cα atoms) in the relative orientation of the TIM-barrel and the lid domain, which is more open in 4ggb. 4ggb also exhibits significantly more disordered structure, with many active-site side chains exhibiting weak electron density and distorted cation-ligand geometry relative to other members of the superfamily (and to 4hpn; data not shown). However, the structure of 4ggb is useful in suggesting which portions of the structure exhibit flexibility. These not only include relative placement of the two domains, but also two loops (residues 12–30 and 136–142) which cover the active site and which are completely disordered in 4ggb. Since 4hpn exhibits a structure which is better ordered and may better reflect the active conformation, 4hpn will be used in further discussion.

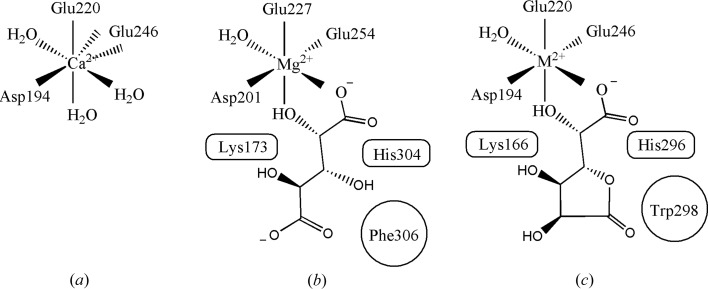

The active-site divalent cation located at the base of the TIM barrel is coordinated by Asp194, Glu220 and Glu246 and three water molecules in an approximately tetragonal bipyramidal geometry (Fig. 5 ▸). Glu246 makes a bifurcated interaction with the metal (OE1–Ca2+, 2.3 Å; OE2–Ca2+, 2.5 Å), which most likely will be converted to a monodentate interaction upon the binding of substrate. The divalent cation was assigned as a calcium ion (present at 200 mM in the crystallization condition) based on ligand bond lengths (2.2–2.3 Å) and a comparative thermal factor analysis (Ca2+ or Mg2+ at full occupancy). The incorporation of Ca2+ rather than Mg2+ (the cation with observed activity) and the uncertainty in the final conformation of highly mobile residues in the active site complicate a computationally driven molecular model of substrate binding. Thus, in order to identify putative active-site residues involved in catalysis, a manually docked model was constructed to guide future mutagenesis experiments.

Figure 5.

Schematic of cation-ligand geometries. (a) Cation-ligand geometry for AtGCI. Glu246 makes a bifurcated interaction with Ca2+, distorting the square-pyramidal geometry. (b) Cation-ligand geometry of BB4687 with bound Mg2+ and meso-xylarate (PDB entry 3ozm). Putative acid/base ligands are shown in rounded boxes and a nonpolar interaction with Phe306 is shown as a circle. (c) Model of d-galactaro-1,4-lactone bound to AtGCI and the corresponding conserved residues.

meso-Xylarate exhibits the same relative stereochemical configuration at Cα and Cβ to the carboxylate as does d-galactaro-1,4-lactone;therefore, the structure of the homolog BB4687 bound to Mg2+ and meso-xylarate (PDB entry 3ozm) was used as a molecular guide to dock d-galactaro -1,4-lactone to the 4hpn structure. Interestingly, all of the residues providing polar interactions with the carboxylate and the hydroxyl α to the carboxylate are conserved between the two structures, such that the binding conformations to the cation are predicted to be very similar. In this model, one of the carboxylate O atoms and the α-hydroxyl group are coordinated to the Mg2+/Ca2+, replacing two of the bound waters (Fig. 5 ▸). In contrast to the racemization/epimerization (with solvent hydrogen exchange) or dehydratase (elimination of H2O) reactions typical of enolase-superfamily members from this subgroup, d-galactaro-1,4-lactone cycloisomerase is proposed to involve a β-elimination reaction yielding an acyclic dicarboxylate product without elimination of water. In all members of this subgroup, an active-site lysine or histidine serves as a general acid or base in the active site. This docking study suggests that Lys166 is the general base that abstracts a proton α to the carboxylate group in the first step of the reaction, while His296 on the opposite side of the barrel is predicted to be the general acid that donates a proton to C3 of the product. A phenylalanine (Phe306) in BB4687, which forms extensive van der Waals interactions with the nonpolar face of meso-xylarate, is a tryptophan (Trp298) in AtGCI and could participate in similar stacking interactions with d-galactaro-1,4-lactone.

Together with previous reports (Taberman et al., 2014 ▸; Bouvier et al., 2014 ▸; Parkkinen et al., 2011 ▸), this work completes the structural elucidation of the first four enzymes used by A. tumefaciens to degrade d-galacturonate by providing the structure of the enzyme that catalyses the third step in the pathway. These structures provide the foundation upon which enzyme engineering could be performed to improve the conversion of d-galacturonate, and ultimately pectin, to biofuels and bulk chemicals.

Supplementary Material

PDB reference: d-galactaro-1,4-lactone cycloisomerase, 4ggb

PDB reference: 4hpn

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a cooperative agreement from the National Institutes of Health (U54GM093342). We acknowledge the staff in the School of Chemical Sciences Mass Spectrometry Laboratory (UIUC) for determining the mass of A9CEQ8 by electrospray ionization. This research used the resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a US Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357. Use of the Lilly Research Laboratories Collaborative Access Team (LRL-CAT) beamline at Sector 31 of the Advanced Photon Source was provided by Eli Lilly Company, which operates the facility.

References

- Adams, P. D. et al. (2011). Methods, 55, 94–106.

- Adams, P. D., Gopal, K., Grosse-Kunstleve, R. W., Hung, L.-W., Ioerger, T. R., McCoy, A. J., Moriarty, N. W., Pai, R. K., Read, R. J., Romo, T. D., Sacchettini, J. C., Sauter, N. K., Storoni, L. C. & Terwilliger, T. C. (2004). J. Synchrotron Rad. 11, 53–55. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Andberg, M., Maaheimo, H., Boer, H., Penttila, M., Koivula, A. & Richard, P. (2012). J. Biol. Chem. 287, 17662–17671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Benz, J. P., Protzko, R. J., Andrich, J. M., Bauer, S., Dueber, J. E. & Somerville, C. R. (2014). Biotechnol. Biofuels, 7, 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Bouvier, J. T., Groninger-Poe, F. P., Vetting, M., Almo, S. C. & Gerlt, J. A. (2014). Biochemistry, 53, 614–616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Emsley, P., Lohkamp, B., Scott, W. G. & Cowtan, K. (2010). Acta Cryst. D66, 486–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Evans, P. (2006). Acta Cryst. D62, 72–82. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Gerlt, J. A., Babbitt, P. C., Jacobson, M. P. & Almo, S. C. (2011). J. Biol. Chem. 287, 29–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Krissinel, E. & Henrick, K. (2004). Acta Cryst. D60, 2256–2268. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Leslie, A. G. W. (1992). Jnt CCP4/ESF–EACBM Newsl. Protein Crystallogr. 26.

- McCoy, A. J. (2007). Acta Cryst. D63, 32–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Parkkinen, T., Boer, H., Jänis, J., Andberg, M., Penttilä, M., Koivula, A. & Rouvinen, J. (2011). J. Biol. Chem. 286, 27294–27300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Richard, P. & Hilditch, S. (2009). Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 82, 597–604. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Taberman, H., Andberg, M., Parkkinen, T., Jänis, J., Penttilä, M., Hakulinen, N., Koivula, A. & Rouvinen, J. (2014). Biochemistry, 53, 8052–8060. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Winn, M. D., Isupov, M. N. & Murshudov, G. N. (2001). Acta Cryst. D57, 122–133. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

PDB reference: d-galactaro-1,4-lactone cycloisomerase, 4ggb

PDB reference: 4hpn