We report radiation necrosis as the first manifestation of a germline mutation in telomerase. A 60-year-old woman presented with defective wound healing after multiple surgical explorations of the chest wall to exclude breast cancer recurrence. At age 42, she received a diagnosis of stage I estrogen receptor–positive left breast infiltrating ductal carcinoma on routine mammography. Lumpectomy with axillary node dissection revealed T1N0 disease. Her adjuvant radiation therapy consisted of 50.4 Gy in 28 fractions followed by a 10-Gy boost in 5 fractions to the tumor bed. She did well for 12 years, when a left rib fracture was incidentally noted on imaging. This prompted multiple needle biopsies which showed atypia but no malignancy. Open surgical biopsy revealed the anterior ribs within the radiation field were replaced with soft tissue, but no malignancy was found. The postoperative course was complicated by multiple wound infections requiring surgical debridement and failed healing of skin grafts left her with an open chest wall wound (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

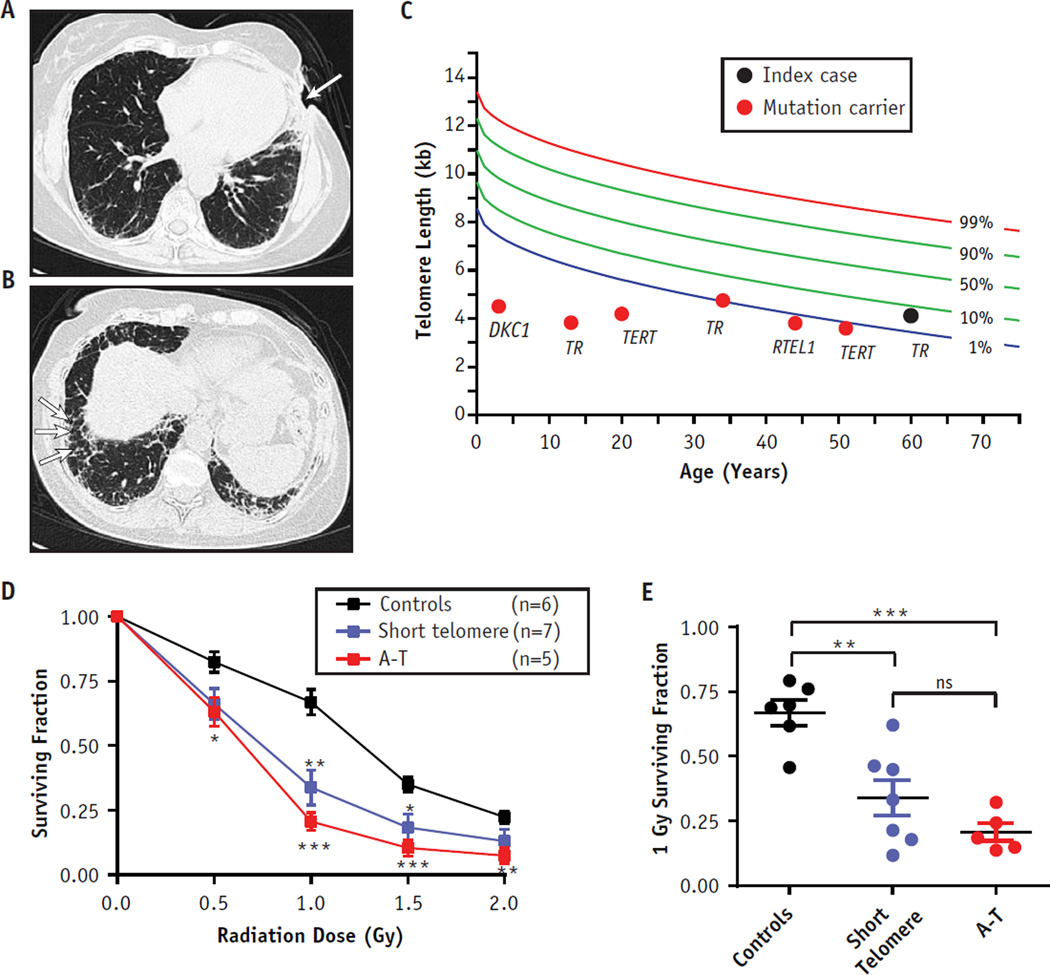

Clinical features and cell survival of cells with short telomeres after irradiation. (A) Nonhealing open, left anterior chest wall wound (arrow) after open biopsy and failed grafts. (B) Basilar honeycombing typical of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (arrows). (C) Telogram shows telomere length of mutation carriers relative to that of age-matched controls (n = 192). Telomeres were measured in peripheral blood lymphocytes by flow cytometry and fluorescence in situ hybridization. Labels indicate the mutant telomere gene in each case. Red circles refer to individuals whose lymphoblastoid cell lines were studied in vitro (D and E). (D) Dose response curve shows the surviving fraction of cells at each dose of ionizing radiation. Data are means from each group of controls, short telomeres, and ataxia telengiectasia (A-T) cells. Each cell line was assayed in quadruplicate, and the experiment was replicated independently. (E) Individual data points for each case at 1 Gy, a threshold which has been shown to be useful in the diagnosis of DNA double-strand break syndromes (1). Error bars refer to standard error of the mean. *P<.05, **P<.01, and ***P<.001, two-sided comparison of differences in surviving fractions relative to those of controls (Student t test; GraphPad Prism software). ns = nonsignificant P value.

She was evaluated at our center for a second opinion. Computed tomography (CT) imaging showed fractured left ribs and chest wall abnormalities consistent with radiation necrosis. In addition, in the contralateral lung, there was basilar honeycombing characteristic of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) (Fig. 1A and B). Family history revealed 2 siblings who died from IPF and myelodysplastic syndrome, a complex pathognomonic for the diagnosis of a short telomere syndrome (2). Genetic evaluation revealed a deleterious mutation in the telomerase RNA gene, TR, that was also found in her siblings (n.80, T>A). The mutation predicted disruption of the essential pseudoknot domain of TR and was associated with short telomere length, below the age-adjusted 10th percentile (Fig. 1C). Additional chest wall reconstruction was deferred given the known risk of respiratory failure after anesthesia and elective surgery in IPF patients (3). During the subsequent year, her wound improved with conservative care, but she developed worsening respiratory symptoms, and subsequently died cancer-free from end-stage lung disease.

In order to test whether short telomeres may predispose to radiation sensitivity, we used a modified cell survival assay that is used in the diagnosis of double-strand break syndromes such as ataxia-telangiectasia (A-T) (1, 4). We examined lymphoblastoid cells derived from 7 other telomerase and telomere gene mutation carriers (Fig. 1C). Four of the carriers were asymptomatic, 2 had IPF, and 1 had bone marrow failure. Cells from these subjects showed significantly compromised survival compared to controls and were similarly sensitive to A-T on average (Fig. 1D and E). In 3 of 7 cases (43%), the surviving fraction at 1 Gy fell at or below 21%, a threshold considered to be diagnostic of A-T in some settings (1). Neither the age nor the extent of the telomere defect predicted the 1-Gy surviving fraction.

Radiation sensitivity and radiation necrosis are rare complications of radiation therapy, but they are well documented in patients with defective DNA doublestrand break repair such as A-T (5). The data we show here indicate that patients with short telomere syndromes are similarly sensitive to radiation. To our knowledge, this is the first report of radiation necrosis in a telomerase mutation carrier. Sensitivity to radiation in the setting of telomere length abnormalities was first documented in telomerase null mice with short telomeres (6), and our data highlight the relevance of these observations in clinical settings.

Syndromes marked by short telomeres manifest as IPF, emphysema, and aplastic anemia (7). Mutations in telomere and telomerase genes are the most common cause of familial pulmonary fibrosis cases, accounting for one-third of cases (7); they also rival alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency as a risk factor for emphysema (8). Short telomere syndrome patients most often present in mid-to-late adulthood and have no associated dysmorphic features. A cancer diagnosis is estimated to affect up to 10% of severe cases, such as in dyskeratosis congenita, and predominantly manifests as myelodysplasia-acute myeloid leukemia and, more rarely, squamous cell head and neck carcinomas (9). There are sparse data regarding cancer treatment outcomes in this population. After bone marrow transplantation, pulmonary fibrosis is a nearly uniform complication, and lung shielding has evolved as a standard to minimize this risk (10). Awareness of this genetic diagnosis is important in clinical settings, where ionizing radiation is used such as in assessing the risk of X ray–based imaging as a screening tool in pulmonary fibrosis, as well as in a preference for radiation-sparing regimens in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Patients suspected of having telomere syndromes and who have a personal or family history of IPF-emphysema, especially, or myelodysplastic syndrome, should be identifiable by telomere length measurement combined with genetic testing.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant (RO1 CA160433), the Ataxia-Telangiectasia Children’s Group, and Common-wealth Foundation (M.A.).

We are grateful to the subjects who volunteered for this research, and Ms. Jenny Wright from the Johns Hopkins Ataxia-Telengiectasia Clinic.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: none.

References

- 1.Sun X, Becker-Catania SG, Chun HH, et al. Early diagnosis of ataxia-telangiectasia using radiosensitivity testing. J Pediatr. 2002;140:724–731. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2002.123879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parry EM, Alder JK, Qi X, et al. Syndrome complex of bone marrow failure and pulmonary fibrosis predicts germline defects in telomerase. Blood. 2011;117:5607–5611. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-11-322149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ghatol A, Ruhl AP, Danoff SK. Exacerbations in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis triggered by pulmonary and nonpulmonary surgery: A case series and comprehensive review of the literature. Lung. 2012;190:373–380. doi: 10.1007/s00408-012-9389-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang AT, Kim T, Wagner JE, et al. A dominant mutation in human rad51 reveals its function in DNA interstrand crosslink repair independent of homologous recombination. Mol Cell. 2015;59:478–490. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gotoff SP, Amirmokri E, Liebner EJ. Ataxia telangiectasia. Neoplasia, untoward response to x-irradiation, and tuberous sclerosis. Am J Dis Child. 1967;114:617–625. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1967.02090270073006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wong KK, Chang S, Weiler SR, et al. Telomere dysfunction impairs DNA repair and enhances sensitivity to ionizing radiation. Nat Genet. 2000;26:85–88. doi: 10.1038/79232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stanley SE, Armanios M. The short and long telomere syndromes: Paired paradigms for molecular medicine. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2015;33:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2015.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stanley SE, Chen JJ, Podlevsky JD, et al. Telomerase mutations in smokers with severe emphysema. J Clin Invest. 2015;125:563–570. doi: 10.1172/JCI78554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alter BP, Giri N, Savage SA, et al. Cancer in dyskeratosis congenita. Blood. 2009;113:6549–6557. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-12-192880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dietz AC, Orchard PJ, Baker KS, et al. Disease-specific hematopoietic cell transplantation: Nonmyeloablative conditioning regimen for dyskeratosis congenita. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2010;46:98–104. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2010.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]