Abstract

The phototropins are blue-light receptors that base their light-dependent action on the reversible formation of a covalent bond between a flavin mononucleotide (FMN) cofactor and a conserved cysteine in light, oxygen or voltage (LOV) domains. The primary reactions of the Avena sativa phototropin 1 LOV2 domain were investigated by means of time-resolved and low-temperature fluorescence spectroscopy. Synchroscan streak camera experiments revealed a fluorescence lifetime of 2.2 ns in LOV2. A weak long-lived component with emission intensity from 600 to 650 nm was assigned to phosphorescence from the reactive FMN triplet state. This observation allowed determination of the LOV2 triplet state energy level at physiological temperature at 16600 cm−1. FMN dissolved in aqueous solution showed pH-dependent fluorescence lifetimes of 2.7 ns at pH 2 and 3.9–4.1 ns at pH 3 to 8. Here, too, a weak phosphorescence band was observed. The fluorescence quantum yield of LOV2 increased from 0.13 to 0.41 upon cooling the sample from 293 to 77 K. A pronounced phosphorescence emission around 600 nm was observed in the LOV2 domain between 77 and 120 K in the steady-state emission.

INTRODUCTION

Plant growth and development are to a great extent regulated by light. Plants have evolved several photoreceptors that are able to respond to both the blue and red regions of the solar spectrum(1-3). The plant phototropins are serine/threonine kinases that undergo autophosphorylation in response to absorption of blue light and control several physiological responses such as phototropism, light-mediated chloroplast movement and stomatal opening (1). The photochemistry in this class of photoreceptors takes place in two flavin mononucleotide (FMN)-binding light, oxygen, or voltage (LOV) domains at the N-terminus of the protein, which comprise approximately 100 amino acids.(4-6) LOV domains form a sub-class of the widely distributed Per-ARNT-Sim (PAS) family of signaling and interaction proteins (7). LOV domains were also identified in algal (Chlamydomonas) phototropin,(8, 9) and in a number of prokaryotes (10-16). They act as signaling photoreceptors involved in the regulation of plant and fungal circadian rhythms (17, 18). Because of the ubiquitous cellular bioavailability of flavins, it has been suggested that LOV domains may serve as genetically encoded switches and fluorescence sensors (19-23). LOV domains share such favorable bioengineering properties with BLUF domains (24), which also bind flavin, and bacteriophytochrome (25, 26), which binds biliverdin. Thus, the photoactivation mechanisms of biological photoreceptors are of considerable interest to bio(medical) research and technology.

Absorption of a blue photon in the LOV domain initiates a photocycle that leads to the formation of a long-lived flavin species absorbing at 390 nm (5, 27, 28). It was proposed that this species corresponds to a covalent cysteinyl-C(4a) adduct (5) which was confirmed using NMR spectroscopy, X-ray crystallography and FTIR spectroscopy.(29-32) Thus, absorption of blue light leads to the transient formation of a covalent bond between the FMN cofactor and the protein, which slowly ruptures in the dark to regenerate the non-covalent dark ground state species, presumably through a base-catalyzed mechanism (33, 34). Absorption of near-UV light may also rupture the covalent adduct (35, 36). Formation of a covalent bond to FMN bond triggers protein conformational changes on the surface of the PAS core which weaken interactions of this core with a C-terminal amphiphilic helix called Jα, packed against its central β-sheet (37-39). Unfolding of the Jα helix is the critical event which regulates C-terminal kinase activity of phototropin and downstream signal transduction (40).

The light-driven reactions of the LOV domain have been studied by means of time-resolved absorption spectroscopy (27, 28, 41, 42). Formation of a spectroscopic photointermediate absorbing at 390 nm, corresponding to the covalent FMN-cysteine adduct, takes place on a μs timescale. The covalent adduct has a lifetime of seconds to hours before it returns to the dark state. An intermediate state preceding adduct formation absorbing in the red showed spectral features characteristic of a FMN triplet state. Ultrafast spectroscopy showed that indeed singlet-to-triplet intersystem crossing takes place on the FMN chromophore on the nanosecond timescale at high yield (43-45). Based on earlier molecular orbital calculations (46) this triplet state was proposed to be the reactive species that leads to adduct formation.(6, 27, 43). Alternatively, a radical pair mechanism was invoked to explain the LOV photoreaction (47-49) with neutral Cys-flavin radicals forming a short-lived intermediate on the reaction coordinate towards the covalent adduct. .Recent spectroscopic and computational work has favored the latter mechanism (50-52, 45, 53, 54).

In this contribution we further explore the primary photophysics of the LOV2 domain of Avena sativa (oat) phototropin 1 and FMN in aqueous solution by means of time-resolved fluorescence spectroscopy utilizing a multichannel synchroscan streak camera. The time-resolved emission data were published before in ref. (55). This work presents a re-analysis of these data and resolves phosphorescence from the reactive triplet state of FMN bound to LOV2 and in aqueous solution, which allows an accurate positioning of the FMN triplet state level at physiological temperature. We discuss the results in relation to low-temperature emission spectroscopy on LOV2 published earlier (55).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample preparation

LOV2 from Avena sativa phototropin 1 was expressed from a construct spanning residues 407 to 563 and contained an N-terminal fusion of protein G and a His-tag.(37) Twelve liters of cells were grown at 37° C to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.4, induced with 500 μM Isopropyl ß-D-thiogalactoside and grown for an additional 14 h after induction at 20 °C. Cells were lysed via sonication. Avena sativa phot1 LOV2 was purified on Ni-NTA resin (Qiagen). The protein was concentrated in a high-pressure stirred ultrafiltration cell with a 3,000 molecular weight cutoff filter (Amicon). Prior to the experiments, the LOV2 domain was dissolved in 20 mM Tris/150 mM NaCl buffer at pH 8.0. For the time-resolved experiments, the absorbance of the sample was adjusted to 0.1 per mm at the absorption maximum of 447 nm. The sample was loaded in a flow system containing a cuvette of 1 mm path length, and flowed at a speed of approximately 5 cm/s by means of a peristaltic pump. The total volume of the flow system was 1.5 ml. For the low temperature fluorescence measurements, the sample was diluted to an absorbance of 0.015 per mm, and contained in plastic cuvettes of 1 cm path length. Flavin mononucleotide (FMN) was purchased from Sigma Chemicals and used without further purification. FMN was dissolved in 20 mM Tris, acetate or formate buffers at pH 8.0, 5.0 or 3.0/2.0, respectively.

Fluorescence spectroscopy

The streak camera setup has been described earlier (56, 57) and was applied to examine the fluorescence decay kinetics of the LOV2 domain and of FMN at pH 2.0, 3.0, 5.0 and 8.0. The time resolved fluorescence kinetics were recorded upon excitation at 400 nm at an excitation power of 100 μW. The pulses were generated with a 50 kHz repetition rate using a regeneratively amplified titanium:sapphire laser (Coherent Mira-Rega). Fluorescence was collected with a right-angle detection geometry using achromatic lenses and detected through a sheet polarizer set at the magic angle (54.7°) with a Hamamatsu C5680 synchroscan camera and a Chromex 250IS spectrograph. The streak images were recorded with a cooled (−55°C) Hamamatsu C4880 CCD camera. The streak image represents the fluorescence intensity as a function of both time (vertical axis) and wavelength (horizontal axis). The image has a size of 1018 (vertical) ×1000 (horizontal) pixels, corresponding to 2033.5 ps and 310 nm, respectively. The spectral resolution was 8 nm and the spectrometer was calibrated by means of a Hg lamp. The spectra were not corrected for the wavelength dependence of the spectrograph diffraction efficiency and streak camera sensitivity. The streak camera data were analyzed with a global analysis program using sums of exponentials (58, 59). Associated with each lifetime is a decay-associated spectrum (DAS). The instrument response function was described by a gaussian (20 ps full width at half-maximum).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Time-resolved fluorescence spectroscopy

FMN singlet-excited state dynamics in LOV2 and aqueous buffer

The room temperature absorption spectrum of dark-adapted Avena sativa LOV2 domain (not shown) agreed with those presented earlier. In accordance with the literature, this species is referred to as D447 (27). The absorption spectrum exhibits a major peak at 447 nm and two shoulders at 422 nm and 473 nm, which correspond to vibronic states of the lowest singlet excited state S1 of the FMN chromophore. The band at 375 nm can be assigned to the higher-lying S2 singlet excited state of FMN.

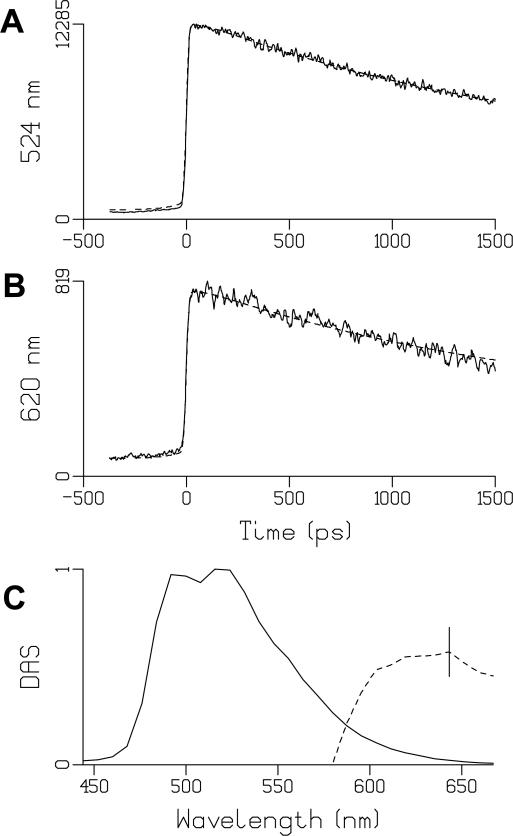

The excited-state dynamics of the LOV2 domain and FMN in aqueous buffer at various pH were examined by means of time-resolved fluorescence spectroscopy. We performed synchroscan streak camera fluorescence measurements upon 400 nm excitation. Figure 1A,B shows the kinetics of the LOV2 domain at 524 and 620 nm, respectively, along with the result of a global analysis procedure. One lifetime is required to adequately describe the tim-resolved fluorescence data. The decay-associated spectrum (DAS) is shown in Fig. 1C (solid line) and shows vibronic maxima near 495 nm and 525 nm and a shoulder at 550 nm. We find a fluorescence lifetime of the LOV2 domain of 2.2 ns, which agrees well with our previous result from ultrafast spectroscopy of 2.0 to 2.2 ns (43, 60) and that of others (44). It is significantly shorter than the fluorescence lifetime of free FMN in aqueous solution ((61, 62) and see below), and shorter than the fluorescence lifetime for the LOV1 domain in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii of 2.9 ns (62). The shortened fluorescence lifetime of the LOV2 domain compared with free FMN in solution most likely results from enhanced intersystem crossing to the triplet state due to the proximity of the cysteine sulfur to the isoalloxazine ring (43, 62, 63). Enhancement of the intersystem crossing rate in LOV2 is induced through weak electron donation by the cysteine which mixes the FMN π-electrons with the sulfur orbitals (63). In agreement with this notion, the C57S mutant of Chlamydomonas LOV1 has a significantly longer fluorescence lifetime of 4.6 ns (62). Ultrafast IR and (time-resolved) FTIR experiments on plant LOV2 domains are consistent with an unprotonated FMN triplet as the primary photoproduct (45, 53, 54).

Fig. 1.

(A, B): Representative traces of LOV2 emission (solid) and their fits (dashed), at 524 nm (A) and 620 nm (B). Estimated lifetime was 2.2 ns. At 524 nm, the signal before time zero can be entirely attributed to the 2.2 ns decay in combination with the backsweep of the synchroscan streak camera system (59). At 620 nm, the relatively higher magnitude of the signal before time zero must be attributed to an additional long lived component. For this we used the 2 μs lifetime of the phosphorescence. During this very long lifetime the signal builds up from about a thousand forward and backward sweeps (the period of the synchroscan is 13 ns). See text for details.

(C) Decay Associated Spectra (DAS) of LOV2. The solid line denotes the 2.2 ns DAS, the dashed line the 2 μs DAS. The dashed phosphorescence DAS has been multiplied by 5 × 104. The vertical bar indicates the estimated standard error, which is negligible for the 2.2 ns DAS.

To date, all time-resolved work on LOV domains indicated strictly single-exponential fluorescence decay of the FMN chromophore in 2 – 4 ns (this work and refs. (43-45, 62, 64-66). This contrasts with results on other flavin-binding photoreceptors such as BLUF domains and cryptochromes where rapid, multiphasic electron transfer processes from nearby aromatic side chains quench the oxidized flavin singlet-excited state on the picosecond timescale (67-77). The single exponential behavior is consistent with a highly ordered structure around the FMN chromophore in LOV domains, which is generally supported by their X-ray structures (6, 32, 78-80). However, it is noteworthy that multiple cysteine conformers were observed in the ground state in some X-ray structures (32, 78) and by FTIR spectroscopy (81, 82). If the reactive cysteine were to shorten the FMN singlet-excited lifetime in LOV domains through a heavy atom effect, the single-exponential fluorescence decay of fluorescence would imply that cysteine conformer interconversion must be fast relative to the singlet excited state lifetime of a few nanoseconds so that an averaged effect is observed. Indeed, molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have indicated that such side chain interconversions occur on the sub-nanosecond timescale (82).

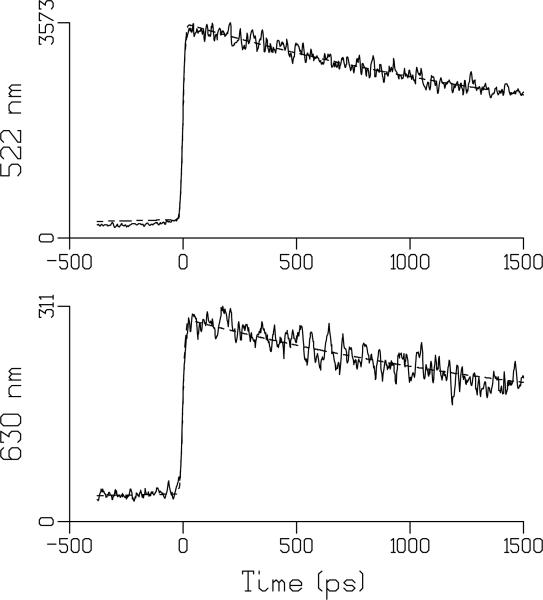

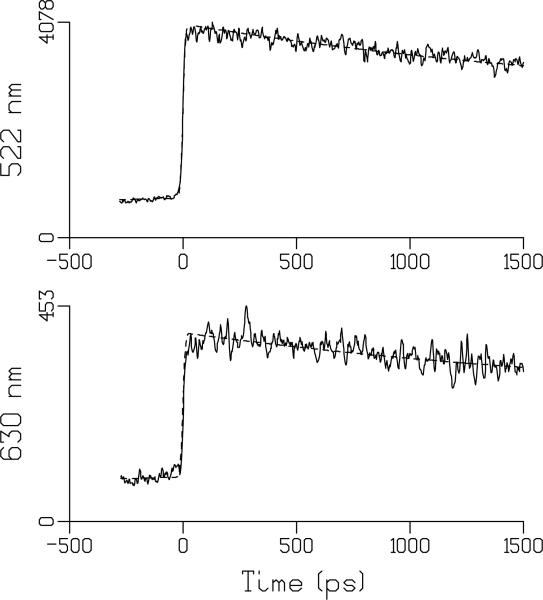

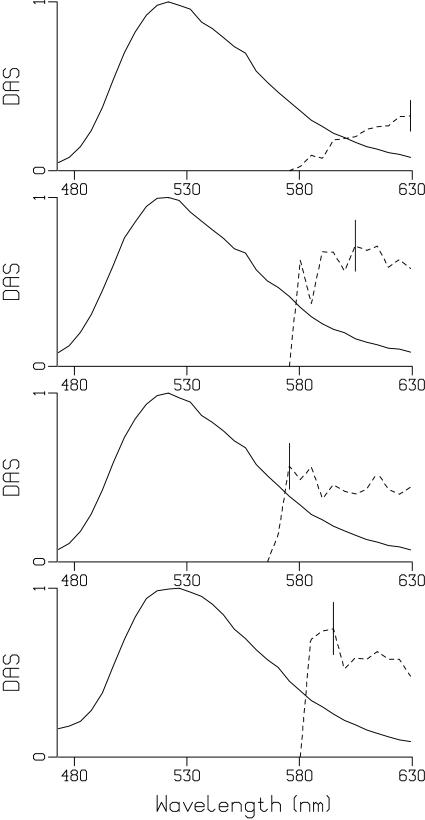

Fig. 2 shows the kinetics of FMN fluorescence emission at 522 and 630 in aqueous solution at pH 2. Fig. 3 shows the kinetics at these wavelengths for FMN in aqueous solution at pH 8. The DAS for FMN at pH 2, 3, 5 and 8 are shown in Fig. 4 and show a broad band with a single maximum near 520 nm. For FMN, monoexponential fluorescence lifetimes of 2.7 ns at pH 2, and 3.9, 4.1 ns and 3.9 ns at pH 3, 5, 8, respectively, were found. The fluorescence lifetime of FMN at pH 8 reasonably agrees with the literature value (61, 62). At pH 2 there is a significant shortening of the FMN singlet excited-state lifetime to 2.7 ns, as we have observed with ultrafast transient absorption spectroscopy (43). Similar results were reported for lumiflavin in aqueous solution, where the shortening of the fluorescence lifetime was assigned to hydronium-ion (H3O+) mediated conversion of neutral lumiflavin to cationic lumiflavin in the singlet excited state (83, 84). Thus, although the LOV2 fluorescence lifetime and that of FMN at pH 2 are similar, there is no mechanistic relation between the two.

Fig. 2.

Representative traces of FMN emission at pH 2 (solid) and their fits (dashed) at 522 nm (top) and 630 nm (bottom). The estimated lifetime was 2.7 ns. At 522 nm, the signal before time zero can be entirely attributed to 2.7 ns decay in combination with the backsweep (after 6.5 ns) of the synchroscan streak camera system. At 630 nm, the relatively higher magnitude of the signal before time zero must be attributed to an additional long lived component and is assigned to phosphorescence. See text for details.

Fig. 3.

Representative traces of FMN emission at pH 8 (solid) and their fits (dashed) at 522 nm (top) and 630 nm (bottom). Estimated lifetime was 3.9 ns. At 522 nm, the signal before time zero can be entirely attributed to 3.9 ns decay in combination with the backsweep (after 6.5 ns) of the synchroscan streak camera system (59). At 630 nm, the relatively higher magnitude of the signal before time zero must be attributed to an additional long lived component and is assigned to phosphorescence. See text for details.

Fig. 4.

Decay Associated Spectra of FMN as a function of pH. From top to bottom pH 2, 3, 5, 8, with the solid lines denoting the 2.7, 3.9, 4.2 and 3.9 ns DAS (at pH 2,3,5,8, respectively), and the dashed lines denoting the10 μs DAS. The dashed phosphorescence DAS has been multiplied by 105. The vertical bar indicates the estimated standard error, which is negligible for the ≈4 ns DAS. The ordinate refers to the amplitude of the Decay-Associated Spectrum

LOV2 phosphorescence at physiological temperature

To describe observation of LOV2 phosphorescence by the streak camera system, some explanation of the data collection method is required. The synchroscan streak camera is synchronized to the pulse train emitted by the Ti:sapphire oscillator (operating at 76 MHz) that seeds the Rega amplifier (operating at 50 kHz). Thus, the streak camera sweeps back and forth every 13 ns while excitation of the sample takes place every 20 μs. For this reason, emission that is longer-lived than the (maximum) 2 ns time window may be recorded on the streak camera image as a constant contribution that is not time-resolved. Its presence becomes apparent as a nonzero signal before time zero, essentially a ‘baseline’ signal that in such a case has a distinct physical origin.

With the 2.2 ns fluorescence lifetime of LOV2, it is expected that such a nonzero signal appears on the streak image as a result from the first ‘back sweep’ at 6.5 ns, because the fluorescence signal has not entirely decayed to zero at that time. In fact, the amplitude of this so-called back sweep signal can be used to accurately estimate fluorescence lifetimes that are signficantly longer than the maximum 2 ns time basis of the streak camera (59), as we do here for LOV2 and FMN in aqueous solution. This is illustrated in Fig. 1A, where a kinetic trace is shown with detection at 524 nm. It shows a signal before time zero that has a finite value, and the subsequent rise and decay of the fluorescence. The dashed line indicates a fit with an estimated single exponential lifetime of 2.2 ns which also takes into account the back sweep effect on the streak camera. The fit accurately describes fluorescence decay and the pre-zero signal.

Fig.1B shows the streak camera signal at 620 nm. Interestingly, the pre-zero signal is higher relative to the fluorescence signal after time zero (amplitude ratio 1:10) as compared to that observed at 524 nm of Fig. 1A (amplitude ratio 1:25). We conclude that a long-lived emission component, additional to the 2.2 ns fluorescence decay, also contributes to the streak camera signal at this longer wavelength. With the laser system operating at 50 kHz (20 μs pulse-to-pulse interval), the streak camera sweeps more than 4000 times between consecutive excitation pulses and accumulates the long-lived emission shown as the finite pre-zero signal in Fig. 1B. Hence, the absolute emission amplitude of the additional component may be very weak. Since we were aware that phosphorescence from the FMN triplet state might be present, we analyzed the data with an additional emission component with a lifetime of 2 μs, the FMN triplet state lifetime in the A. sativa LOV2 domain (27). Fig. 1C shows the DAS of the LOV2 fluorescence (solid line) and the additional long-lived component (dashed line), which was expanded 5 × 104 times. It shows a band spanning 600 to 650 nm, which indeed is typical of flavin phosphorescence (85). Thus, this experiment provides the first experimental observation of phosphorescence from the reactive FMN triplet state in LOV domains at physiological temperature. With a modeled decay time of 2 μs, the integrated area under the phosphorescence band as compared to that of the fluorescence band provides an estimate of the dipole strength of the spin-forbidden 3FMN → 1FMN transition. It amounts to roughly 10−5 of that of the optical singlet-state emission, corresponding to the spin-forbidden nature of the triplet-singlet transition. The observation of phosphorescence allows determination of the LOV2 triplet state energy level at 16600 cm−1. Losi et al. (86) determined the energy content of a transient species absorbing at 660 nm, which is presumed to correspond to the triplet state, in the Bacillus subtilis YtvA protein by calorimetric methods. They estimated the energy content of the triplet state species to be 198 kJ/mole or about 16800 cm−1, in excellent agreement with our present value.

For FMN in aqueous solution, phosphorescence phenomena similar to those in LOV2 were observed. The kinetic traces of FMN at pH 2 and pH 8 show a relatively higher pre-zero signal at 630 nm than at 522 nm (Fig. 2 and 3). Global analysis of the time-resolved data yielded the DAS of fluorescence (solid line) and phosphorescence (dashed line) shown in Fig. 4 for FMN at pH 2, 3, 5 and 8. Because the FMN triplet lifetime in aqueous solution is a priori unknown (we did not attempt to control the oxygen concentration), we arbitrarily adjusted the lifetime to 10 μs to give a DAS amplitude similar to that of LOV2. For FMN at pH 2, the phosphorescence is not well resolved, which may be related to the low triplet yield under these conditions (43).

We also performed streak camera experiments on LOV2 on a short time basis of 200 ps with 3 ps time resolution (not shown). As for the long time basis of 2 ns, a single fluorescence decay time constant of about 2 ns was observed, without appreciable spectral shifting and a DAS identical to that shown in Fig. 1C. The lack of spectral red-shifting of the fluorescence on a ps timescale is consistent with the notion that the solvation response of a protein matrix to creation of an excited state on the chromophore is very rapid and occurs on the (sub) 100 fs timescale (87-89). In similar experiments on BLUF domains, no spectral red-shifting of the fluorescence spectrum was observed (77, 90, 70).

Low-temperature absorption and fluorescence spectroscopy

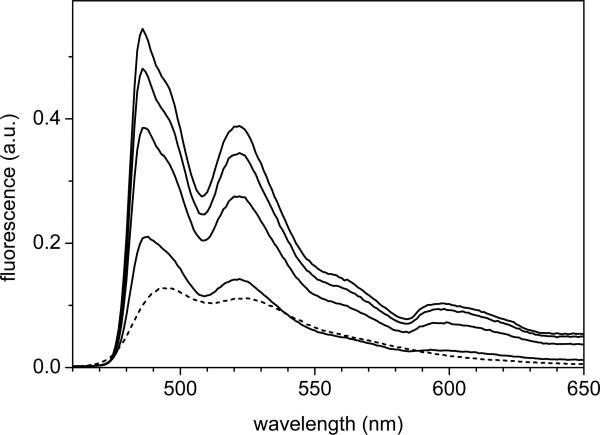

To compare the observation of phosphorescence in the streak camera data, it is useful to consider low-temperature steady-state fluorescence data of the Avena sativa LOV2 domain, reproduced from ref. (55) shown in Fig. 5. The excitation wavelength was 447 nm. The fluorescence emission spectra exhibit peaks at 485 nm and 520 nm at low temperature. Increasing the temperature to room temperature shifts the peak positions to 495 nm and 525 nm, respectively. The slightly different intensity ratios of the 495 and 525 nm bands between the room-temperature steady-state fluorescence spectrum (1.2:.1) and that of the streak camera (0.95:1, Fig. 1C) arise because the latter was not corrected for wavelength sensitivity of the detection system. The splitting of the 473 nm band in the absorption spectrum at 77 K (39, 33) is also reflected in the low-temperature fluorescence spectra, where a double band structure is observed at 485 and 495 nm. The double peak structure was assigned to two different FMN C(4)=O conformer populations, co-existing in the dark state and characterized by C(4)=O carbonyl frequencies at 1712 and 1694 cm−1 .These arise from a single H-bond or double H-bonds to this site, from Gln-513 or Asn-492, respectively (39).

Fig. 5.

Fluorescence emission spectra of the LOV2 domain of Avena sativa phototropin 1 at, from top to bottom, 77 K, 90 K, 120 K, 150 K and 293 K (dashed line). The excitation wavelength was 447 nm.

Lowering the temperature from 298 K to 77 K leads to a marked increase of the fluorescence intensity. Integration of the fluorescence spectra shows that the fluorescence yield at 77K is 3.7 times higher than at room temperature. With a room temperature fluorescence quantum yield of 0.13 in the LOV2 domain (43), this observation suggests that the fluorescence quantum yield at 77 K is 0.41. The increase probably follows from internal properties of the FMN chromophore rather than from specific protein – chromophore interactions, as Sun et al. have reported that the fluorescence emission of free flavins in solution similarly increases upon lowering the temperature to 77 K (85).

A conspicuous feature of the low temperature emission spectrum is the small but distinct band near 600 nm. Following our streak camera observations of Fig. 1, this band can be assigned to phosphorescence of the protein-bound flavin (85). The phosphorescence is observed in the 77 K, 90 K and 120 K spectra, and to a lesser extent at 150 K. At room temperature no phosphorescence is observed in steady-state. Thus, while at room temperature the phosphorescence band is only observed in a time-resolved measurement, lowering the temperature leads to ready observation of phosphorescence in the steady-state luminescence. This observation allows accurate positioning of the flavin triplet state in the LOV2 domain at 16900 cm−1 at cryogenic temperatures.

The question arises why phosphorescence from the FMN triplet state is not observed in the steady-state emission spectrum at physiological temperature, yet is so prominent at cryogenic temperatures. The observation of a phosphorescence band at 77 – 120 K indicates that (with the forbidden nature of phosphorescence), the FMN triplet state must have a long lifetime. At 5 K, where no photoconversion to the adduct state occurs upon blue-light illumination (data not shown), an orangered glow lasting for a fraction of a second emerged from the sample upon illumination and subsequent quick blocking of the light (55), indicating that phosphorescence indeed has a relatively long lifetime. Sun et al observed phosphorescence for flavin in frozen solution at 77 K (85), indicating that such long FMN triplet lifetimes are an intrinsic property of flavin. At room temperature, the FMN triplet state is the precursor to the adduct state and has a short lifetime of only 2 μs, and hence phosphorescence is not observed in steady state. At low temperature, LOV2 only partly photoconverts to the adduct state, at a 28% fraction at 77 K and 78% at 150 K (50, 82). Sato et al. demonstrated that the partial photoconversion is related to the aforementioned multiplicity of cysteine conformers in LOV2. At such low temperatures, only limited thermal interconversion between the conformers takes place and only those conformers that have a favorable molecular configuration with respect to the conserved cysteine form the covalent adduct upon illumination (82). Hence, the FMN triplet states of those LOV2 domains that do not undergo adduct formation obtain a long lifetime and phosphorescence becomes observable in steady-state emission.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The construct of oat phot1 LOV2 was generously provided by Kevin Gardner of University of Texas and Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas. M.G. was supported by the Chemical Sciences Council of the Netherlands Foundation for Scientific Research (NWO-CW). J.T.M.K. was supported by the Earth and Life Sciences Council of the Netherlands Foundation for Scientific Research (NWO-ALW) via a VIDI grant, and through the Foundation of Fundamental Research on Matter (FOM). K.M. was supported through NIH grant GM 36452, S.C. was supported through an NSF Predoctoral Fellowship.

Footnotes

This paper is part of the Symposium-in-Print on “Blue Light Effects”

REFERENCES

- 1.Briggs WR, Tseng TS, Cho HY, Swartz TE, Sullivan S, Bogomolni RA, Kaiserli E, Christie JM. Journal of Integrative Plant Biology. 2007;49:4–10. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kami C, Lorrain S, Hornitschek P, Fankhauser C. Plant Development. Vol. 91. Elsevier Academic Press Inc; San Diego: LIGHT-REGULATED PLANT GROWTH AND DEVELOPMENT. pp. 29–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moglich A, Yang XJ, Ayers RA, Moffat K. Structure and Function of Plant Photoreceptors. Annual Review of Plant Biology, Vol 61. 2010;61:21–47. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042809-112259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Christie JM, Salomon M, Nozue K, Wada M, Briggs WR. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1999;96:8779–8783. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.15.8779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Salomon M, Christie JM, Knieb E, Lempert U, Briggs WR. Biochemistry. 2000;39:9401–9410. doi: 10.1021/bi000585+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crosson S, Moffat K. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98:2995–3000. doi: 10.1073/pnas.051520298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moglich A, Ayers RA, Moffat K. Structure. 2009;17:1282–1294. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2009.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang KY, Merkle T, Beck CF. Physiologia Plantarum. 2002;115:613–622. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3054.2002.1150416.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang KY, Beck CF. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100:6269–6274. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0931459100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Losi A, Polverini E, Quest B, Gartner W. Biophysical Journal. 2002;82:2627–2634. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75604-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crosson S, Rajagopal S, Moffat K. Biochemistry. 2003;42:2–10. doi: 10.1021/bi026978l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Purcell EB, Siegal-Gaskins D, Rawling DC, Fiebig A, Crosson S. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:18241–18246. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705887104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Purcell EB, Crosson S. Current Opinion in Microbiology. 2008;11:168–178. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2008.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Swartz TE, Tseng TS, Frederickson MA, Paris G, Comerci DJ, Rajashekara G, Kim JG, Mudgett MB, Splitter GA, Ugalde RA, Goldbaum FA, Briggs WR, Bogomolni RA. Science. 2007;317:1090–1093. doi: 10.1126/science.1144306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Losi A, Gartner W. Photochemical & Photobiological Sciences. 2008;7:1168–1178. doi: 10.1039/b802472c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krauss U, Minh BQ, Losi A, Gartner W, Eggert T, von Haeseler A, Jaeger KE. Journal of Bacteriology. 2009;191:7234–7242. doi: 10.1128/JB.00923-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.He QY, Cheng P, Yang YH, Wang LX, Gardner KH, Liu Y. Science. 2002;297:840–843. doi: 10.1126/science.1072795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Imaizumi T, Tran HG, Swartz TE, Briggs WR, Kay SA. Nature. 2003;426:302–306. doi: 10.1038/nature02090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Drepper T, Eggert T, Circolone F, Heck A, Krauss U, Guterl JK, Wendorff M, Losi A, Gartner W, Jaeger KE. Nature Biotechnology. 2007;25:443–445. doi: 10.1038/nbt1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chapman S, Faulkner C, Kaiserli E, Garcia-Mata C, Savenkov EI, Roberts AG, Oparka KJ, Christie JM. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105:20038–20043. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807551105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Strickland D, Moffat K, Sosnick TR. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105:10709–10714. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709610105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moglich A, Ayers RA, Moffat K. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2009;385:1433–1444. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu YI, Frey D, Lungu OI, Jaehrig A, Schlichting I, Kuhlman B, Hahn KM. Nature. 2009;461:104–U111. doi: 10.1038/nature08241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schroder-Lang S, Schwarzel M, Seifert R, Strunker T, Kateriya S, Looser J, Watanabe M, Kaupp UB, Hegemann P, Nagel G. Nature Methods. 2007;4:39–42. doi: 10.1038/nmeth975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shu XK, Royant A, Lin MZ, Aguilera TA, Lev-Ram V, Steinbach PA, Tsien RY. Science. 2009;324:804–807. doi: 10.1126/science.1168683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Toh KC, Stojkovic EA, van Stokkum IHM, Moffat K, Kennis JTM. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107:9170–9175. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911535107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Swartz TE, Corchnoy SB, Christie JM, Lewis JW, Szundi I, Briggs WR, Bogomolni RA. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276:36493–36500. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103114200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kottke T, Heberle J, Hehn D, Dick B, Hegemann P. Biophysical Journal. 2003;84:1192–1201. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74933-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Salomon M, Eisenreich W, Durr H, Schleicher E, Knieb E, Massey V, Rudiger W, Muller F, Bacher A, Richter G. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98:12357–12361. doi: 10.1073/pnas.221455298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Crosson S, Moffat K. Plant Cell. 2002;14:1067–1075. doi: 10.1105/tpc.010475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Swartz TE, Wenzel PJ, Corchnoy SB, Briggs WR, Bogomolni RA. Biochemistry. 2002;41:7183–7189. doi: 10.1021/bi025861u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fedorov R, Schlichting I, Hartmann E, Domratcheva T, Fuhrmann M, Hegemann P. Biophysical Journal. 2003;84:2474–2482. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)75052-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alexandre MTA, Arents JC, van Grondelle R, Hellingwerf KJ, Kennis JTM. Biochemistry. 2007;46:3129–3137. doi: 10.1021/bi062074e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zoltowski BD, Vaccaro B, Crane BR. Nature Chemical Biology. 2009;5:827–834. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kawaguchi Y, Nakasone Y, Zikihara K, Tokutomi S, Terazima M. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2010;132:8838–+. doi: 10.1021/ja1020519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kennis JTM, van Stokkum NHM, Crosson S, Gauden M, Moffat K, van Grondelle R. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2004;126:4512–4513. doi: 10.1021/ja031840r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Harper SM, Neil LC, Gardner KH. Science. 2003;301:1541–1544. doi: 10.1126/science.1086810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yamamoto A, Iwata T, Sato Y, Matsuoka D, Tokutomi S, Kandori H. Biophysical Journal. 2009;96:2771–2778. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2008.12.3924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alexandre MTA, van Grondelle R, Hellingwerf KJ, Kennis JTM. Biophysical Journal. 2009;97:238–247. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.03.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Harper SM, Christie JM, Gardner KH. Biochemistry. 2004;43:16184–16192. doi: 10.1021/bi048092i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guo HM, Kottke T, Hegemann P, Dick B. Biophysical Journal. 2005;89:402–412. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.058230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Corchnoy SB, Swartz TE, Lewis JW, Szundi I, Briggs WR, Bogomolni RA. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278:724–731. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209119200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kennis JTM, Crosson S, Gauden M, van Stokkum IHM, Moffat K, van Grondelle R. Biochemistry. 2003;42:3385–3392. doi: 10.1021/bi034022k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schuttrigkeit TA, Kompa CK, Salomon M, Rudiger W, Michel-Beyerle ME. Chemical Physics. 2003;294:501–508. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Alexandre MTA, Domratcheva T, Bonetti C, van Wilderen L, van Grondelle R, Groot ML, Hellingwerf KJ, Kennis JTM. Biophysical Journal. 2009;97:227–237. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.01.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Song PS. Photochemistry & Photobiology. 1968;7:311–313. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1968.tb08018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kay CWM, Schleicher E, Kuppig A, Hofner H, Rudiger W, Schleicher M, Fischer M, Bacher A, Weber S, Richter G. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278:10973–10982. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205509200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bittl R, Kay CWM, Weber S, Hegemann P. Biochemistry. 2003;42:8506–8512. doi: 10.1021/bi034123i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kottke T, Dick B, Fedorov R, Schlichting I, Deutzmann R, Hegemann P. Biochemistry. 2003;42:9854–9862. doi: 10.1021/bi034863r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schleicher E, Kowalczyk RM, Kay CWM, Hegemann P, Bacher A, Fischer M, Bittl R, Richter G, Weber S. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2004;126:11067–11076. doi: 10.1021/ja049553q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dittrich M, Freddolino PL, Schulten K. Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 2005;109:13006–13013. doi: 10.1021/jp050943o. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Domratcheva T, Fedorov R, Schlichting I. Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation. 2006;2:1565–1574. doi: 10.1021/ct0600114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pfeifer A, Majerus T, Zikihara K, Matsuoka D, Tokutomi S, Heberle J, Kottke T. Biophysical Journal. 2009;96:1462–1470. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2008.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sato Y, Iwata T, Tokutomi S, Kandori H. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2005;127:1088–1089. doi: 10.1021/ja0436897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gauden M, Crosson S, van Stokkum IHM, van Grondelle R, Moffat K, Kennis JTM. Low-temperature and time-resolved spectroscopic characterization of the LOV2 domain of Avena sativa phototropin. In: Avrillier S, Tualle JM, editors. Femtosecond Laser Applications in Biology. SPIE; Bellingham: 2004. pp. 97–104. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gobets B, van Stokkum IHM, Rogner M, Kruip J, Schlodder E, Karapetyan NV, Dekker JP, van Grondelle R. Biophysical Journal. 2001;81:407–424. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)75709-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gobets B, Kennis JTM, Ihalainen JA, Brazzoli M, Croce R, van Stokkum LHM, Bassi R, Dekker JP, van Amerongen H, Fleming GR, van Grondelle R. Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 2001;105:10132–10139. [Google Scholar]

- 58.van Stokkum IHM, Larsen DS, van Grondelle R. Biochimica Et Biophysica Acta-Bioenergetics. 2004;1657:82–104. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2004.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.van Stokkum IHM, van Oort B, van Mourik F, Gobets B, van Amerongen H. (Sub)-Picosecond Spectral Evolution of Fluorescence Studied with a Synchroscan Streak-Camera System and Target Analysis. In: Aartsma TJ, Matysik J, editors. Biophysical Techniques in Photosynthesis Vol. II. Springer; Dordrecht, The Netherlands: 2008. pp. 223–240. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kennis JTM, Alexandre MTA. Mechanisms of light activation in flavin-binding photoreceptors. In: Silva E, Edwards AM, editors. Flavins: Photochemistry and Photobiology. The Royal Society for Chemistry Publishing; Cambridge: 2006. pp. 287–319. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Visser A, vanHoek A, Visser NV, Lee Y, Ghisla S. Photochemistry and Photobiology. 1997;65:570–575. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Holzer W, Penzkofer A, Fuhrmann M, Hegemann P. Photochemistry and Photobiology. 2002;75:479–487. doi: 10.1562/0031-8655(2002)075<0479:scofmb>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Alexandre MTA, van Grondelle R, Hellingwerf KJ, Robert B, Kennis JTM. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics. 2008;10:6693–6702. doi: 10.1039/b810040c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Holzer W, Penzkofer A, Hegemann P. Chemical Physics. 2005;308:79–91. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Holzer W, Penzkofer A, Susdorf T, Alvarez M, Islam SDM, Hegemann P. Chemical Physics. 2004;302:105–118. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Alexandre MTA, Purcell EB, van Grondelle R, Robert B, Kennis JTM, Crosson S. Biochemistry. 2010;49:4752–4759. doi: 10.1021/bi100527a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Brazard J, Usman A, Lacombat F, Ley C, Martin MM, Plaza P, Mony L, Heijde M, Zabulon G, Bowler C. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 132:4935–4945. doi: 10.1021/ja1002372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gauden M, van Stokkum IHM, Key JM, Luhrs DC, Van Grondelle R, Hegemann P, Kennis JTM. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103:10895–10900. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600720103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gauden M, Grinstead JS, Laan W, van Stokkum HM, Avila-Perez M, Toh KC, Boelens R, Kaptein R, van Grondelle R, Hellingwerf KJ, Kennis JTM. Biochemistry. 2007;46:7405–7415. doi: 10.1021/bi7006433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bonetti C, Mathes T, van Stokkum IHM, Mullen KM, Groot ML, van Grondelle R, Hegemann P, Kennis JTM. Biophysical Journal. 2008;95:4790–4802. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.139246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bonetti C, Stierl M, Mathes T, van Stokkum IHM, Mullen KM, Cohen-Stuart TA, van Grondelle R, Hegemann P, Kennis JTM. Biochemistry. 2009;48:11458–11469. doi: 10.1021/bi901196x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kennis JTM, Groot ML. Current Opinion in Structural Biology. 2007;17:623–630. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dragnea V, Waegele M, Balascuta S, Bauer C, Dragnea B. Biochemistry. 2005;44:15978–15985. doi: 10.1021/bi050839x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zirak P, Penzkofer A, Schiereis T, Hegemann P, Jung A, Schlichting I. Chemical Physics. 2005;315:142–154. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Shibata Y, Murai Y, Satoh Y, Fukushima Y, Kajima K, Ikeuchi M, Itoh S. Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 2009;113:8192–8198. doi: 10.1021/jp901631b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Toh KC, van Stokkum IHM, Hendriks J, Alexandre MTA, Arents JC, Perez MA, van Grondelle R, Hellingwerf KJ, Kennis JTM. Biophysical Journal. 2008;95:312–321. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.117788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gauden M, Yeremenko S, Laan W, van Stokkum IHM, Ihalainen JA, van Grondelle R, Hellingwerf KJ, Kennis JTM. Biochemistry. 2005;44:3653–3662. doi: 10.1021/bi047359a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Halavaty AS, Moffat K. Biochemistry. 2007;46:14001–14009. doi: 10.1021/bi701543e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Moglich A, Moffat K. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2007;373:112–126. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.07.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zoltowski BD, Schwerdtfeger C, Widom J, Loros JJ, Bilwes AM, Dunlap JC, Crane BR. Science. 2007;316:1054–1057. doi: 10.1126/science.1137128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bednarz T, Losi A, Gartner W, Hegemann P, Heberle J. Photochemical & Photobiological Sciences. 2004;3:575–579. doi: 10.1039/b400976b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sato Y, Nabeno M, Iwata T, Tokutomi S, Sakurai M, Kandori H. Biochemistry. 2007;46:10258–10265. doi: 10.1021/bi701022v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Drossler P, Holzer W, Penzkofer A, Hegemann P. Chemical Physics. 2002;282:429–439. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Tyagi A, Penzkofer A. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology a-Chemistry. 2010;215:108–117. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sun M, Moore TA, Song PS. Journal of American Chemical Society. 1972;94:1730–1740. doi: 10.1021/ja00760a052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Losi A, Quest B, Gartner W. Photochemical & Photobiological Sciences. 2003;2:759–766. doi: 10.1039/b301782f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Homoelle BJ, Edington MD, Diffey WM, Beck WF. Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 1998;102:3044–3052. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kennis JTM, Larsen DS, Ohta K, Facciotti MT, Glaeser RM, Fleming GR. Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 2002;106:6067–6080. [Google Scholar]

- 89.van Stokkum IHM, Gobets B, Gensch T, van Mourik F, Hellingwerf KJ, van Grondelle R, Kennis JTM. Photochemistry and Photobiology. 2006;82:380–388. doi: 10.1562/2005-06-15-RA-572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Laan W, Gauden M, Yeremenko S, van Grondelle R, Kennis JTM, Hellingwerf KJ. Biochemistry. 2006;45:51–60. doi: 10.1021/bi051367p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]