Abstract

Hematopoietic stem cells are formed during embryonic development, and serve as the foundation of the definitive blood program for life. Notch signaling has been well established as an essential direct contributor to HSC specification. However, several recent studies have indicated that the contribution of Notch signaling is complex. HSC specification requires multiple Notch signaling inputs, some received directly by hematopoietic precursors, and others that occur indirectly within neighboring somites. Of note, proinflammatory signals provided by primitive myeloid cells are needed for HSC specification via upregulation of the Notch pathway in hemogenic endothelium. In addition to multiple requirements for Notch activation, recent studies indicate that Notch signaling must subsequently be repressed to permit HSC emergence. Finally, Notch must then be reactivated to maintain HSC fate. In this review, we discuss the growing understanding of the dynamic contributions of Notch signaling to the establishment of hematopoiesis during development.

Keywords: Hematopoiesis, Notch signaling, Hematopoietic stem cell, Hemogenic endothelium

Introduction

Hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) are the foundation of the vertebrate blood system. These stem cells self-renew to maintain a steady pool of HSCs that can differentiate as needed into cells of the lymphoid, myeloid and erythroid lineages, and thereby maintain blood cell homeostasis for life. Thus far it has not been possible to derive HSCs in vitro from pluripotent precursors, necessitating a deeper understanding of the mechanisms leading to their development in vivo. HSCs are born during embryonic development, though the molecular mechanisms governing their emergence are not completely understood. In recent years, it has become clear that the dynamic context of the developing vertebrate embryo provides numerous molecular and environmental cues critical for HSC formation, including the Notch signaling pathway [1].

The generation of HSCs during embryonic development is dependent upon Notch signaling [2]. Within wild-type/Notch1−/− chimeric mice, Notch1-null cells fail to contribute to hematopoiesis, indicating that the Notch1 receptor is required cell-autonomously, for HSC potential [3]. In both mice and zebrafish, Notch signaling functions genetically upstream of the transcription factor Runx1 [4, 5], which is essential prior to HSC emergence [6, 7]. Although Notch signaling provides direct transcriptional regulation of several genes that are important for HSC formation, including Hes1, Hes5, Hey2 and Gata2 [8–12], Notch does not appear to directly regulate Runx1 expression [12, 13]. Rather, a transcriptional complex including Gata2 drives Runx1 expression within the hemogenic endothelium from which HSCs derive [13], providing a defined, cell-autonomous link between receipt of Notch activation and the emergence of HSCs. Interestingly, the hematopoietic defect that occurs in the absence of Notch signaling can be rescued by the artificial induction of Runx1 but not Gata2 [5]. This strongly indicates that Notch signaling regulates additional, unknown factors required for Runx1 induction.

Although it is well established that Notch signaling is required cell-autonomously for HSC formation [2, 3], recent evidence has revealed that the Notch signaling pathway exerts complex regulation of HSC specification, emergence and maintenance in the developing embryo. It is now apparent that multiple, distinct Notch signaling events act in both direct and indirect ways, and provide both positive and negative regulation over the establishment of the adult hematopoietic system.

Mechanisms of Notch signaling

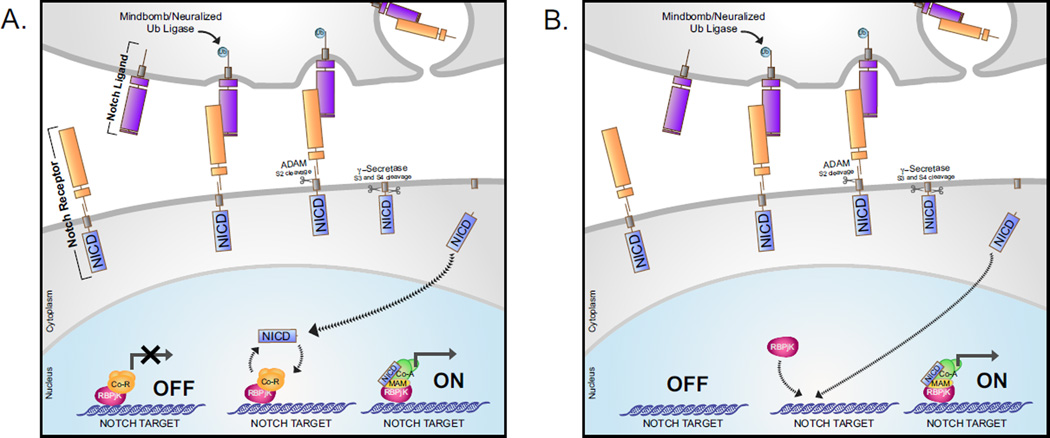

Notch signaling allows for communication between cells in close contact, through the binding of ligands and receptors on adjacent cells. Notch family receptors consist of single-pass transmembrane proteins, including an extracellular domain made up of ligand-binding EGF repeats, a membrane-tethered transcriptionally active intracellular domain and multiple proteolytic cleavage sites allowing for separation of these components upon ligand binding. The Notch signal initiates when a ligand of the Delta/Serrate/Lag-2 (DSL) family on the signal-sending cell interacts directly with a Notch receptor on the signal-receiving cell. Within the signal-sending cell, ubiquitination of the ligand by the E3 ubiquitin ligases Mindbomb [14, 15] and Neuralized [16–19] promote Notch activation by stimulating endocytosis of the receptor-bound ligand. The resulting tension exposes the S2 proteolytic cleavage site at the base of the Notch receptor extracellular domain, near the cell membrane, facilitating S2 cleavage by ADAM family metalloproteases [20–22]. Subsequently, the remaining membrane-tethered receptor is cleaved by γ-secretase from the S3 to S4 cleavage sites, releasing the Notch intracellular domain (NICD) and allowing its translocation to the nucleus. In the most established model of Notch transcriptional regulation, the Notch transcriptional partner RBPjK recruits nuclear corepressor (NcoR) and histone deacetylases (HDACs) and holds Notch target genes in a transcriptionally repressed state in the absence of Notch signaling (Figure 1A)[23]. Upon Notch activation, nuclear NICD displaces these transcriptional corepressors and recruits coactivators such as Mastermind, initializing transcription of direct Notch targets. Although according to this traditionally accepted model, RBPjK actively represses activation of Notch targets in the absence of Notch signaling, recent work has indicated that Notch transcriptional regulation may be more complex than previously realized. Rather than constantly occupying Notch-responsive enhancer elements, in many cases RBPjK is recruited alongside NICD, suggesting that RBPjK does not repress all Notch targets prior to Notch activation (Figure 1B) [24]. It remains unclear whether RBPjK functions as a steady-state repressor for direct Notch targets in the context of HSC formation.

Figure 1. Overview of Notch Signaling.

A. Notch receptors are activated by binding of the Notch extracellular domain (NECD) to Notch ligands of the Delta/Serrate/Lag-2 families on adjacent signal-sending cell. Ubiquitination of Notch ligands by the Mindbomb and Neuralized E3 ubiquitin ligases promotes endocytosis, facilitating cleavage by ADAM family metalloproteases through exposure of the S2 proteolytic cleavage site. S2 cleavage results in the separation of ligand-bound NECD, and the remaining transmembrane receptor. Subsequently, the ligand-NECD complex is taken up by the signal-sending cell. The remaining membrane-bound Notch receptor is cleaved at the S3 and S4 proteolytic sites by Gamma-Secretase, releasing the Notch intracellular domain (NICD) from the membrane tether and allowing NICD to translocate to the nucleus. In the absence of Notch receptor activation, Notch transcriptional targets are bound by RBPjK/CSL and transcriptional corepressors (Co-R), and held in a transcriptionally repressed state. Nuclear NICD binds RBPjK, displacing the corepressor complex and allowing for the recruitment of transcriptional partner Mastermind (MAM) and additional coactivators (Co-A), allowing for transcriptional activation of Notch target genes. B. In some cases RBPjK occupies Notch transcriptional target sites in a more dynamic manner. In this case, RBPjK does not occupy the Notch target site in the absence of Notch activation, and is instead recruited upon activation alongside NICD and transcriptional co-activators.

Induction of Notch signaling allows coordinated cell fate decisions amongst neighboring cells, through lateral inhibition or lateral induction mechanisms [25, 26]. Lateral inhibition occurs when stochastic differences between cells result in Notch activation in one neighbor, and this activation results in the transcriptional repression of Notch ligand in the signal receiving, Notch-active cell. The resulting negative feedback loop enforces directionality of Notch activation, and can drive adjacent cells of shared developmental origin to distinct fates. In contrast, lateral induction occurs when Notch activation results in increased expression of Notch ligand on the signal receiving, Notch-active cell. In lateral induction, Notch signaling induces positive feedback. As Notch-active cells become Notch-activators, elevated levels of Notch activity drive adjacent cells to the same fate. Lateral induction results in clusters of Notch-active cells, lateral inhibition creates a “salt and pepper” arrangement of Notch-active cells amongst Notch-inactive neighbors by restricting Notch activation [26, 27].

Origins of the hematopoietic system

Vertebrate hematopoiesis begins during embryogenesis with several independent waves of blood formation preceding the eventual emergence of definitive HSCs, which will establish and maintain the adult blood program. This process initiates with the independent generation of primitive myeloid and primitive erythroid cells, which both arise transiently without a sustained pool of progenitors. Primitive erythroid cells and endothelial cells arise concomitantly within the yolk sac of mammals and birds [28]. Primitive erythrocytes and endothelial cells derive from a shared ‘hemangioblast’ mesodermal precursor, during gastrulation that differentiates into distinct hematopoietic and endothelial lineages prior to reaching the yolk sac [29]. Embryo-derived primitive myeloid cells arise with restricted potential from the yolk sac shortly following primitive erythrocyte formation [30, 31]. Multipotent erythromyeloid progenitor (EMP) cells, which give rise to both definitive erythroid and myeloid lineages, emerge shortly after primitive erythropoiesis and myelopoiesis, also from the yolk sac [32]. Whereas primitive erythrocytes arise from a shared endothelial precursor, EMPs were recently suggested to derive from the endothelium itself in the murine yolk sac [33]. Embryonic hematopoiesis culminates with the generation of HSCs, the only cells capable of long-term self-maintenance and differentiation into a full repertoire of hematopoietic lineages. In the mouse, HSCs have been reported to emerge from hemogenic endothelium primarily within the dorsal aorta, from the umbilical and vitelline arteries, and the placenta [34–38]. HSCs have also been reported to emerge within the head vasculature and heart, although these findings are controversial [39, 40].

Although lower vertebrates develop externally to the parent and lack an extraembryonic yolk sac, hematopoiesis likewise proceeds through four waves, via cellular and molecular mechanisms that appear to be largely conserved. In this regard, work in zebrafish and Xenopus has helped clarify the developmental origins of embryonic and adult blood cells. In mammals, lineage restricted primitive erythrocytes and primitive myeloid cells arise during a similar period within the yolk sac, however work in zebrafish has defined distinct mesodermal origins of these two populations. Primitive myeloid cells derive from the anterior lateral plate mesoderm (ALM), and differentiate within the rostral blood island, on the anterior region of the yolk ball [41]. In contrast, primitive erythrocytes, EMPs and HSCs are thought to share a common origin within the posterior lateral plate mesoderm (PLM) of zebrafish, which is analogous to the dorsal lateral plate (DLP) of Xenopus. In both species, cells within this bilateral mesodermal population undergo commitment to primitive hematopoietic or endothelial fate, followed by medial migration, convergence at the midline, and the initiation of vasculogenesis [28]. The formation of HSCs from hemogenic endothelium of the dorsal aorta is conserved from humans to zebrafish [28]. Of the four embryonic waves of vertebrate hematopoiesis, Notch signaling is essential only for the establishment of HSCs [2, 4, 42, 43], although it also appears to influence the development of primitive erythrocytes [44].

A role for Notch signaling in hematovascular fate determination?

Signaling involved in mesodermal commitment to an endothelial fate precedes HSC development. In both mice and zebrafish, primitive erythrocytes and endothelium arise from a shared hemangioblast precursor [29, 45]. Multiple studies in zebrafish have postulated that Notch signaling influences the development of endothelial and primitive erythroid cells from the PLM [46, 47]. In one study, Notch activation in the early zebrafish embryo led to increased numbers of primitive erythrocytes and a corresponding decrease in endothelial cells, suggesting that Notch signaling influences the determination of endothelial versus primitive erythroid fate [47], consistent with its role in lateral inhibition. More recently, however, Notch signaling has been reported to promote the proliferation of endothelial precursors within the PLM [46]. Additionally, the gain of Notch signaling that occurs with the loss of Notch inhibitors numb and numb-like results in primitive erythroblasts that fail to mature and instead undergo apoptosis [48], indicating that Notch signaling inhibition promotes primitive erythrocyte survival. Accordingly, murine RBPjK mutants experience an elevated number of primitive erythrocytes, due to reduced levels of apoptosis [44], whereas the zebrafish Notch signaling mutant mindbomb shows no noticeable reduction in primitive erythrocytes [4]. Presently, it appears that Notch signaling may independently promote endothelial lineage expansion within the PLM and the maintenance of primitive erythrocytes as they undergo differentiation. Further study is necessary to elucidate any contribution of Notch signaling to fate determination within lateral plate mesoderm.

Notch signaling in arterial specification

Hematopoietic stem cells are produced from the major arterial vessels, most robustly from the ventral wall of the dorsal aorta, with additional contributions from the vitelline and umbilical arteries in the mouse [34, 35, 37, 38]. Early observations of the close association between the major arterial vessels and the earliest hematopoietic clusters [49] and the determination that these regions are the first to generate HSCs, led to the longstanding hypothesis that arterial specification is a prerequisite to HSC formation [38, 50]. Endothelial cells and HSCs share a common mesodermal origin across vertebrate species [29, 51–53]. Within the endothelial lineage, the major arterial vessels in particular give rise to HSCs, suggesting arterial specification may be an intermediate step necessary for HSC formation. This idea has been bolstered by the lack of venous contribution to HSCs, and by shared requirements for Hedgehog, VEGF, and Notch signaling in both arterial specification and HSC emergence.

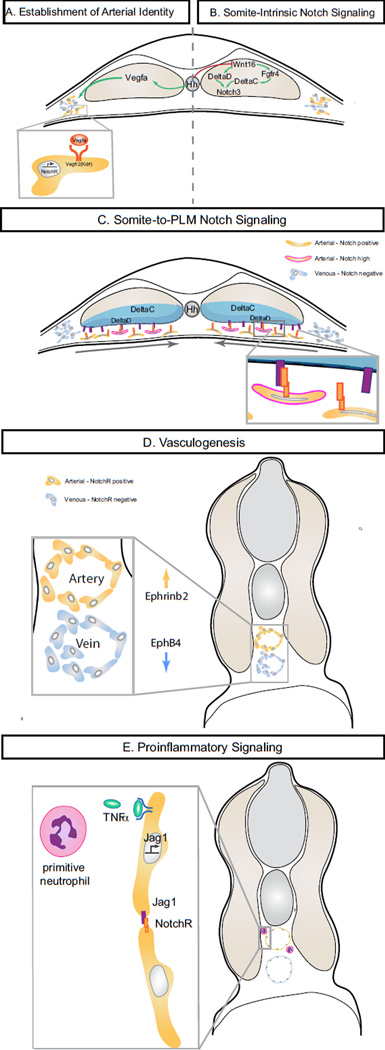

Mechanistically, work in zebrafish has shown that Hedgehog secreted from the notochord and floor plate stimulates the production of vascular endothelial growth factor a (Vegfa) from somitic tissues [54]. Both Hedgehog and VEGF signaling pathways are required for the migration of endothelial progenitors, lumenization during primary vasculogenesis, and arterial specification [54–59]. Hedgehog and Vegfa both function upstream of Notch signaling in the specification of arterial identity [54, 60]. Notch promotes arterial specification at least in part through the direct regulation of the arterial ligand EphrinB2 [61], which together with its venous receptor, EphB4, mediates the segregation of venous and arterial cells into distinct vessels by forward and reverse Eph/Ephrin transmembrane signaling [62–66]. Downstream of Hedgehog and Vegfa, Notch activation bestows both arterial identity [43, 66, 67] and HSC fate from hemogenic endothelium [43, 68, 69], placing Notch signaling as an essential downstream effector of this signaling axis (Figure 2A).

Figure 2. Multiple contributions of Notch signaling surrounding HSC specification in zebrafish embryos.

A. Establishment of Arterial Identity. Hedgehog secreted by the notochord stimulates the production of Vegfa from the somites, initiating the arterial program including Notch ligand and receptor expression. B. Somite-Intrinsic Notch Signaling. Non-canonical Wnt ligand Wnt16 controls the pro-hematopoietic somitic expression of Notch ligands deltaC and deltaD. Fgf signaling downstream of Wnt16 is required for somitic deltaC, but not deltaD expression. Activation of the somitic Notch3 receptor, possibly via the DeltaC/D ligands, promotes HSPC specification, possibly by regulation of the organization or function of the sclerotome compartment. C. Somite-to-PLM Notch signaling. During medial convergence of the posterior lateral plate mesoderm, direct cell contact allows for Notch signaling between DeltaC and DeltaD ligands on the ventral face of the somite and Notch receptors on migrating arterial cells. D. Vasculogenesis. Direct arterial Notch target EphrinB2, together with venous EphB4, promotes arteriovenous segregation and the vasculogenesis. Formation of intact vasculature is required for the establishment of circulation and for circulation-dependent hemogenic endothelial maintenance. F. Proinflammatory signaling. Production of TNFα by primitive neutrophils signals through Tnfr2 to promote arterial expression of jag1a. Jag1a is required for HSPC formation, possibly through endothelialintrinsic signaling with the Notch1a receptor.

Establishment of arterial fate begins far in advance of vasculogenesis, initiating as early as the 5-somite stage in the zebrafish embryo [70]. In developing zebrafish embryos, the Hes-related transcription factor hey2 promotes arterial fate determination within the early PLM, and loss of Hey2 results in severe defects in vasculogenesis and lack of arterial expression [72–75]. Although murine Hey2 mutants have only mild vascular defects [11, 76], the combined loss of Hey1 and Hey2 results in severe defects in arterial specification and vascular morphogenesis, similarly to zebrafish hey2 mutants and reminiscent of murine Notch1-null embryos [77, 78], suggesting a conserved role of Hey transcription factors in the establishment of functional vasculature.

In zebrafish, Hey2 functions downstream of Hedgehog and Vegfa, but its expression is maintained in mindbomb Notch signaling mutants [60, 75]. Hey2 is required for arterial expression of notch1b and ephrinB2a, and hemogenic endothelial expression of runx1 and cmyb [73–75]. Both arterial and hematopoietic defects in hey2 morphants are rescued by restoration of Notch signaling, placing Hey2 as a key initiator of arterial specification in zebrafish [75]. Although Hey2 has not been reported to function upstream of Notch signaling in mice, the Hey2 transcriptional co-regulators Foxc1 and Foxc2 are required for expression of Notch1, Notch4, Dll4, Jag1, as well as EphrinB2 [79, 80], allowing for the possibility that Hey2 may act upstream of Notch signaling during the initiation of mammalian arterial specification.

Several ligands and receptors of Notch signaling are expressed in the dorsal aorta during the period of arterial and hematopoietic specification. Within the E9.5–10.5 aorta, at the time HSPC clusters are formed, the Dll4, Jag1 and Jag2 ligands and Notch1 and Notch4 receptors are arterially expressed [81]. Notch1 is essential for arterial specification, and is required cell-autonomously for HSC formation [2, 3, 82, 83]. Although Notch4 is dispensable for normal arteriogenesis, it may provide some contribution to vascular development as Notch1/Notch4 double mutants fail to form lumenized vessels and have a more severe phenotype than Notch1 mutants alone [83]. Dll4 expression is initiated within arterial cells downstream of Vegfa [80]. Both homozygous and heterozygous Dll4 mutants are embryonic lethal, with broad vascular defects prior to HSC emergence [82, 84]. In contrast, Dll4 overexpression results in the ectopic expansion of arterial markers to the venous endothelium, including Hey1, Notch1, and EphrinB2, suggesting that Dll4 is sufficient to initiate the arterial Notch program within endothelial cells [85].

Notch signaling itself is required for the expression of a number of Notch ligands and receptors within the dorsal aorta. In mice, Notch signaling is required for arterial expression of the ligands Jag1 and Jag2, and for expression of the Notch1 receptor [12], suggesting these factors might be regulated by a primary Notch signaling event within the endothelium. Similarly, Notch signaling is required for the expression of deltaC and notch3 within the dorsal aorta of embryonic zebrafish [60]. The conserved regulation of Notch ligands and receptors by Notch signaling suggests that multiple, sequential Notch signaling events occur within the dorsal aorta.

Jag1 mutant embryos undergo normal arterial development, but within the dorsal aorta, both hematopoietic gene expression within the hemogenic endothelium and hematopoietic cluster formation are reduced [81]. Notch1 and Jag1 are expressed in a salt-and-pepper fashion within the arterial endothelium [12]. This finding, paired with the close proximity of Jag1- and Notch1-expressing cells, is suggestive of inductive signaling between adjacent endothelial cells. The stochastic development of Notch-sending and Notch-receiving cells within the hemogenic endothelium may be regulated by Sox17, which directly regulates Notch1 through conserved binding sites in the Notch1 promoter and has opposing effects on Notch1 and Jag1 expression [87]. Notch signaling through Jag1-Notch1 interaction results in direct transcriptional activation of Gata2 within the hemogenic endothelium. However, the hematopoietic defect of Notch1 mutants is more severe than the defect of Jag1 mutants, suggesting involvement of additional Notch ligands [12, 81]. Dorsal aorta formation and hematopoietic cluster formation appear normal in homozygous Jag2 mutants [81].

Finally, Dll1 maintains arterial identity through regulation of Neuropilin-1 (Nrp1) and the downstream responsiveness to VEGFA, but its expression in the endothelium initiates around E13.5, far after hematopoietic specification [88]. While Dll1 is not expressed within arterial endothelium at E10.5, it is expressed in cells dispersed throughout the subaortic region [89]. Coculture with Dll1-expressing OP9 cells is sufficient to rescue hematopoietic colony forming capacity of ligand-signaling deficient Mib−/− para-splachnopleuric explants [89]. Although these findings suggest non-endothelial cells near the aorta may contribute to pro-hematopoietic Notch signaling within the endothelium, it remains unclear whether Dll1 is important for HSC formation, or whether exogenous Dll1 is simply sufficient to rescue the function of a different ligand.

Similar to Notch, Vegfa is also required for both arterial and hematopoietic specification, and recent studies have demonstrated distinct contributions of Vegfa to these processes. Of three splice isoforms of Vegfa expressed during embryogenesis, the Vegfa short isoform, Vegfa121, is sufficient to rescue both Hey2 and runx1 expression following Hedgehog inhibition [75]. In Xenopus, somitic Eto2 is required for expression of the medium and long isoforms of Vegfa, that, while dispensible for vasculogenesis and arterial specification, are required for expression of the hemogenic endothelial markers Runx1, Scl, Gata2, and Gfi1 [90]. Similarly, knockdown of eto2 in zebrafish inhibits formation of hemogenic endothelium without alteration to arterial expression of deltaC, dll4, notch1b and notch3 [90]. Therefore, rather than filling a single requirement, Vegfa makes both shared and distinct contributions to arterial specification and hemogenic endothelial patterning.

Is Notch key to the hemogenic potential of arterial endothelium?

In a number of cases, the extension of arterial gene expression to venous endothelium confers expression of hematopoietic genes, and even hematopoietic cell emergence from venous vessels, providing some insight into the molecular mechanisms that confer hemogenic potential. In one example, Nrp1 acts as a co-receptor to VEGFR-2, enhancing the affinity and level of response to Vegfa within arterial endothelium [91, 92]. Expression of Nrp1 is inhibited in the venous endothelium by COUP-TFII, which prevents a response to VEGF signaling in these cells [93]. Endothelial-specific deletion of COUP-TFII results in venous expression of arterial markers, including Nrp1, Hey1, Jag1 and Notch1, as well the formation of ectopic c-Kit+ CD45+ hematopoietic clusters [94]. Similarly, venous hematopoietic cluster formation accompanies the ectopic expression of arterial genes in Alk1 and Endoglin mutants [95, 96]. In a third instance, constitutively activated Hedgehog signaling in zebrafish ptc1;ptc2 mutants results in the expansion of arterial expression to the venous endothelium, and this is accompanied by ectopic runx1 expression in the posterior cardinal vein [58]. Finally, whole-embryo activation of Notch signaling by heat-shock induction of NICD1 results in an expansion of both arterial and hemogenic endothelial expression in the posterior cardinal vein [4]. Therefore, it is possible that the molecular specification of arterial endothelium creates a permissive environment for hematopoietic development by initiating the expression of Notch ligands and receptors essential to HSC formation.

Within the context of hematopoiesis, Notch signaling seems to be a unique element driving HSC potential. To this end, EMPs, which arise from endothelial cells similarly to HSCs, emerge independent of Notch signaling [2, 3, 42]. Recently, HSCs and EMPs were suggested to arise from distinct endothelial populations, with expression of Ly6A differentiating aortic endothelial cells with HSC potential [33]. Jag1 mutants, which have normal arterial specification, but are deficient in HSC formation, fail to generate Ly6a-positive cells within the dorsal aorta [81]. Similarly, in vitro programmed hemogenic endothelium requires Notch1 expression to maintain lymphoid potential, with Sox17-Notch-deficient cells generating only definitive erythroid and myeloid lineages [87]. Taken together, these reports indicate a key role for Notch signaling in establishing the hemogenic capacity of the dorsal aorta.

Somitic signaling contributes to hematopoiesis

Recently, the somites have become implicated as essential contributors to the hematopoietic specification process. The β-catenin-independent Wnt16 ligand is expressed within the somites and is required for HSC specification independently of arterial specification [97]. Somitic expression of the Notch ligands deltaC and deltaD are downregulated following wnt16 knockdown. Combined rescue of both ligands is sufficient to restore expression of hemogenic endothelial markers runx1 and cmyb within the floor of the dorsal aorta, while neither alone is sufficient for rescue [97]. Thus far it is not clear why both Notch ligands are needed within the somite. The DeltaC and DeltaD ligands interact homo- and heterophilically during somite segmentation [98]. Although both ligands are required in this process, DeltaC is sufficient to permit Notch activation while DeltaD is not, suggesting that signaling occurs through DeltaC-DeltaC and DeltaC-DeltaD dimers [98]. In HSC specification, it is unclear whether DeltaC and DeltaD function redundantly, as heterodimers, or independently with distinct functions.

The constitutive Hedgehog signaling that occurs in ptc1;ptc2 double mutants results in an increase in arterial endothelium and a concomitant 89% decrease in runx1 expressing endothelial cells, due to a simultaneous increase of Vegfa expression and decrease of wnt16, deltaC and deltaD expression within the somites [58].

Recent studies in the zebrafish embryo have demonstrated dynamic regulation of HSC specification by Fgf signaling, which first promotes hematopoietic specification through somitic signaling at 14–17 hours post fertilization, and then from creating a restrictive environment for HSC emergence from 20.5 hours, after the formation of the vascular cord [99, 100]. Within the early, positive window, Fgf signaling regulates somitic expression of deltaC, but not deltaD, through the Wnt16-dependent Fgfr4 receptor [99], indicating distinct regulation of deltaC and deltaD downstream of somitic Wnt16.

Two somitic Notch signaling events are required for HSC formation within the zebrafish embryo: somite-intrinsic Notch signaling and somite-to-PLM Notch signaling (Figure 2). Interaction between the migrating PLM cells and the ventral surface of the somite is mediated by the junctional adhesion molecule Jam1a, on PLM cells, and its binding partner Jam2a on somitic cells [101]. Direct contact between the somite and PLM is required for efficient Notch signal transduction to the PLM. When the function of either jam1a or jam2a is lost, reduced Notch signal transmission from the somite to the PLM disrupts hemogenic endothelial programming, whereas arterial differentiation occurs normally. The hematopoietic defect resulting from insufficient somite-PLM contact can be partially rescued by the provision of exogenous DeltaC, however it is fully rescuable by DeltaD [101]. Given the inability of DeltaD to individually activate Notch signaling during somite segmentation, it is possible that DeltaD may signal more effectively to the adjacent PLM.

Gata2 is a direct transcriptional target of Notch signaling and is required cell-autonomously for HSC formation prior to the endothelial-hematopoietic transition [2, 3, 12, 102]. In zebrafish, the Gata2 homologue Gata2b is specifically required for HSC formation [103]. Expression of gata2b initiates in the vascular cord during PLM convergence, and is dependent upon both Wnt16 and endothelial Notch receptors, suggesting that somite-to-PLM Notch signaling directly specifies hemogenic endothelium through Gata2b function.

An in-depth analysis of the tissue-specific requirements for the various Notch receptors recently revealed that Notch signaling must be activated both within the endothelium and the somites in order for HSC specification to proceed normally [104]. Of the four Notch receptors in the zebrafish embryo, Notch1a, Notch1b, and Notch3 are independently required for HSC formation, whereas Notch2 is not required. Whereas the Notch1 homologues Notch1a and Notch1b function directly within the endothelium, Notch3 is required within the somite and regulates HSC formation in a non cell-autonomous manner. Notch3 functions epistatically downstream of Wnt16, and combinatorial low-level knockdowns indicate notch3 is required synergistically with deltaC and deltaD, suggesting that Notch3 may be activated within the somite by one or both of these ligands (Figure 2B). While it is still unclear how somite-intrinsic Notch activation affects HSC emergence, both Wnt16 and Notch3 are required for the proper formation of the sclerotomal compartment of the somite. The transcription factor Pax9, which marks the sclerotome [105], was recently shown to be important for HSPC emergence. Knockdown of pax9 results in the decreased generation of cmyb-positive cells within the dorsal aorta [106], further supporting a contribution to HSC generation by the sclerotome. Although several lines of evidence have indicated the importance of sclerotome for HSPC specification, the exact contribution this tissue makes is not known. One likely explanation is that correct somite morphology or organization is necessary for effective transmission of Notch signaling from the somite to the PLM. It has also been proposed that Notch3-activated somitic cells may interact directly with the hemogenic endothelium following dorsal aorta formation, either by incorporating into the aortic wall or giving rise to the smooth muscle precursors that envelop the dorsal aorta. In chicken embryos, somite derived cells incorporate into the aortic endothelium in a Notch-dependent manner [107–109]. This process occurs in the period leading up to HSC emergence, and it is conceivable that these cells may relay an unknown hematopoietic inductive signal. In both mice and chicken embryos, the sclerotome gives rise to vascular smooth muscle cells that directly surround the aorta [110, 111]. However, sclerotome-derived smooth muscle cells are not required for aortic hematopoiesis [112], making it unlikely that the sclerotomal contribution occurs through this population.

Proinflammatory signaling and HSC emergence

Although embryonic development occurs in a protected environment under relatively sterile conditions, HSC formation is preceded by a transient wave of functional primitive myeloid cells. Recently, inflammatory signals produced by these primitive myeloid cells were found to be critical for the establishment and expansion of HSPCs, in part through the regulation of the Notch pathway.

Proinflammatory signaling pathways are heavily activated within HSPC clusters associated with the mouse dorsal aorta [113]. The innate inflammatory cytokine Interleukin-1 is expressed in the dorsal aorta and budding hematopoietic cells, and promotes the activity of nascent HSPCs [114]. Type I and II Interferon produced by primitive myeloid cells activate innate inflammatory signaling within the hemogenic endothelium [113]. Interferon signaling is required for the formation and expansion of HSPCs, whereas EMP formation occurs independently of this signal in both mice and zebrafish [113]. Combined knockdown of tnfa and ifng results in more severe reduction of runx1 expression than loss of either cytokine individually, suggesting cooperative action by multiple proinflammatory cytokines in HSC formation [113]. Tnfα, in particular, is provided by primitive neutrophils, and signals through Tnfr2 to activate expression of the Notch ligand jag1a in the aortic endothelium [115]. Similar to the requirement for Jag1 in mice, zebrafish Jag1a is required for HSC formation but not arterial specification [81, 115]. Of the two Notch1 homologues, low level knockdowns of jag1a with notch1a results in a more severe downregulation of hematopoietic expression, while combined knockdown of jag1a with notch1b does not. This suggests that Jag1a may signal through the Notch1a receptor to promote the formation and expansion of HSCs (Figure 2D). Interestingly, aortic expression of Jag1 is dependent on Notch signaling in mice [12]. If Jag1 regulation is conserved, it is possible that it may represent an intersection of successive hematopoietic Notch requirements.

Downregulation of Notch signaling in emerging HSCs

As discussed previously, multiple Notch signaling events positively regulate HSC specification. Notch transcriptional targets, including Gata2, Hes1, Hrt1 and Hrt2 are expressed in the endothelium and budding clusters within the dorsal aorta [9, 12, 77]. Recent evidence from mice suggests that Notch signaling negatively regulates HSC emergence following the specification of hemogenic endothelial cells and must be down regulated for HSC emergence to progress. VE-Cadherin:Cre mediated permanent induction of NICD1 in the endothelium and endothelial-derived cells results in a surprising lack of hematopoietic clusters within the dorsal aorta in E10.5 embryos, and a deficiency in fetal liver colonization by Notch-active cells [116]. Although total loss of Notch signaling inhibits HSC specification, deletion of either Notch1 or Notch1-regulator Sox17 from E9.5 mouse AGM explants increases the hematopoietic output of the dorsal aorta [117]. Concordantly, late chemical inhibition of Notch signaling inhibition results in increased production of CD45+ cells in both mouse para-splanchnopleura explants and in avian embryos [112]. Chemical inhibition of Notch signaling also accelerates hematopoietic cluster formation, suggesting that Notch actively delays the onset of the budding process. However, this Notch inhibition-mediated hematopoietic expansion is transient, with newly formed cells undergoing apoptosis under continued Notch inhibition [112].

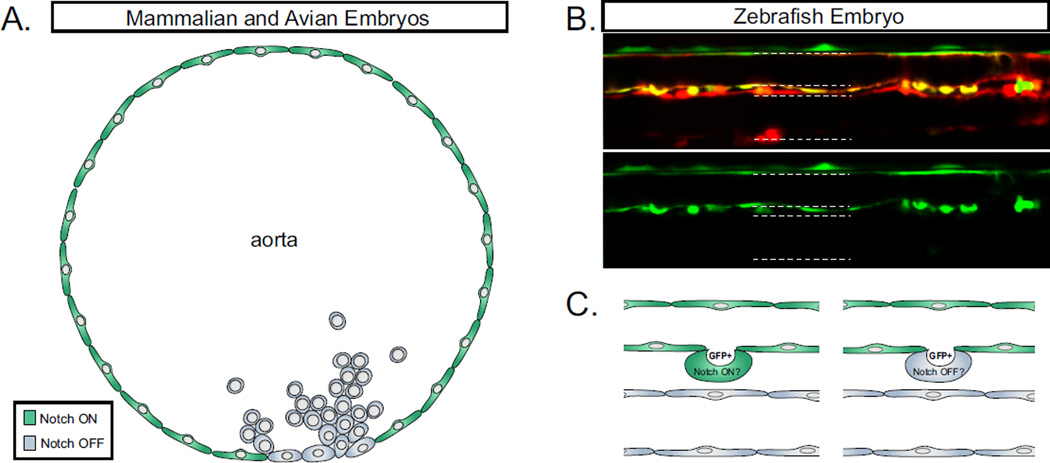

During normal hematopoietic cluster formation in both mouse and chicken embryos, Notch activity is downregulated specifically in hematopoietic clusters, but maintained in the surrounding aortic endothelium [112, 118]. This drop in Notch activity may result from loss of Sox17, which promotes Notch1 expression in arterial endothelium while actively repressing expression of hematopoietic transcription factors Runx1 and Gata2 [117]. The expression of VE-Cadherin and Dll4 are also downregulated in hematopoietic clusters relative to the aortic endothelium [112], suggesting that hematopoietic clusters experience a general loss of arterial and endothelial identity during EHT. Although both Notch1 and Notch4 are expressed in the murine dorsal aorta, only Notch1 must be downregulated, whereas enforced activation of Notch4 signaling by ectopic NICD4 impairs vascular remodeling but does not inhibit hematopoiesis [116]. Consistent with this, the Notch1 target Hes1 is progressively downregulated in emergent murine HSPCs as they mature [112], indicating a requirement for down-regulation of the Notch signal for HSC emergence.

The downregulation of Notch activity in chicken embryos is directly observable by the reduced fluorescence of the Tp1:Venus Notch reporter in budding hematopoietic clusters [112]. In zebrafish embryos, Tp1:GFP is expressed in arterial endothelium in advance of HSC formation, and is not downregulated during HSPC budding (Figure 3). However, epistatic studies in zebrafish have recently suggested that the requirement for Notch downregulation may be conserved in this system. In zebrafish embryos, Cfos acts genetically upstream of the Notch-mediated maintenance of dll4 and ephrinb2a following arterial specification [119]. Deacetylation of cfos by the transcriptional repressors Ncor2 and Hdac3 is required for HSC emergence, suggesting that the formation of HSCs may be tied to the downregulation of arterial identity in zebrafish as well [119]. In zebrafish, it is likely that HSPC emergence proceeds too quickly to yield a noticeable decrease in Tp1:GFP fluorescence. In vivo visualization of this process may instead require new tools allowing for the detection of Notch receptor activation in real time.

Figure 3. Notch activity in budding hematopoietic cells.

A. Notch signaling is inactivated in the budding hematopoietic clusters of higher vertebrates. Green coloring indicates cells in a “Notch-on” active Notch signaling state. Grey coloring indicates cells in a “Notch-off” inactive Notch signaling state. B. Confocal microscopy of HSPC budding in transgenic zebrafish. Kdrl:Cre; bactin:DsRed labels vascular and vascular-derived cells, and Tp1:GFP labels cells responsive to Notch activity. White arrows indicate cells undergoing EHT. Notch signaling is active throughout the dorsal aorta, and budding HSPCs have high levels of Notch reporter GFP at 48hpf. C. Due to the rapid development of the zebrafish embryo, it remains unclear whether Tp1:GFP+ budding HSPCs are truly Notch-active, or whether these cells have inactivated Notch signaling while the GFP protein persists.

Tight regulation of the response to Notch1 receptor-mediated signaling is provided by a type-1 incoherent feed forward loop [9]. To this effect, Notch1 simultaneously controls expression of transcriptional activators, such as Gata2, and transcriptional repressors, such as Hes1. Following simultaneous activation of both Gata2 and Hes1, Hes1 provides direct inhibition of Gata2 expression, resulting in a restricted pulse of the positive hematopoietic regulator. Loss of Hes1, combined with a loss of Hes5, results in the formation of large hematopoietic clusters that lack functionality [9]. This phenotype is reminiscent of the robust, accelerated formation of non-functional hematopoietic clusters formed under Notch inhibition, suggesting that Notch-dependent repression of cluster formation occurs via Hes1 and Hes5. Repression of premature cluster formation is likely a hematopoietic-specific process, as Hes1 and Hes5 are dispensable for arterial differentiation [9] and late Notch inhibition does not induce hematopoietic clusters in the vein [112].

Post-emergence hematopoietic contributions of Notch signaling

Although Notch activity must be downregulated in order to form hematopoietic clusters that contain functional HSPCs, Notch signaling is required in multiple capacities post-emergence. Notch signaling has a well-characterized role in lymphocyte development [120]. Additionally, a novel role for Notch signaling was recently identified in HSPCs following emergence from the dorsal aorta region. Notch1 hypomorphs successfully generate functional HSCs that seed the fetal liver, however, these cells have impaired reconstitutive capacity. Similarly, conditional deletion of RBPjK following the endothelial to hematopoietic transition results in similarly impaired competitive reconstitution. Together, these results suggest a critical, cell-autonomous requirement for Notch signaling that occurs post-emergence, although the underlying molecular mechanism(s) has not been defined. Within the bone marrow niche, Notch signaling induced by endothelial Jag1 balances the quiescence and self-renewal of long-term (LT) HSCs, thereby preventing exhaustion of the LT-HSC population [121]. Similarly, Notch activation restricts differentiation of primary cord-derived hematopoietic cells while maintaining normal levels of proliferation [122]. It is conceivable that Notch signaling may have a similar role in maintaining a steady pool of the nascent HSC population.

Conclusion

HSCs are formed through a complex process that has yet to be fully recapitulated in vitro, suggesting that we still do not understand all requisite aspects of their development. Although Notch signaling has been known to be an essential component for HSC generation, recent studies suggest that it makes a far more complex contribution than was previously appreciated. Leading up to HSC specification, Notch signaling promotes the proliferation of early endothelial cells. In establishing the arterial program, Notch signaling makes two important contributions to the establishment of HSCs. First, it allows proper morphological development of the vasculature, permitting the establishment of circulation, which is necessary for HSC development, and second, it promotes the expression of Notch receptors and ligands that are subsequently required for HSC development. Somite-intrinsic Notch signaling establishes the sclerotomal compartment of the somite, which makes an essential, but poorly understood contribution to HSC specification [104]. Our current understanding suggests the sclerotome presents Notch ligand(s) to the shared vascular precursors of HSCs as they migrate across the ventral face of the somites to form the vascular cord at the embryonic midline. In this case, somite-intrinsic and arterial Notch signaling act hierarchically upstream of the somite-to-PLM signal, on the signal-sending and signal-receiving cells, respectively. An additional Notch ligand, Jag1, is induced by proinflammatory signaling and activates Notch1 in an endothelial-intrinsic manner [81, 115]. The number of Notch signaling events at present represents a puzzle, as we do not yet understand how the multiple intrinsic Notch signals (arterial, somite-to-PLM, and interendothelial) differ. Do these distinct Notch signaling events activate different downstream targets, and how is this achieved? Do they instead raise the overall level of Notch signaling, allowing for greater target activation? In zebrafish, where the two involvements of the somite have been described, three of the four Notch receptors are required for hematopoiesis [104], and there is some separation of ligands and receptors involved in arterial specification, somitic signaling, and interendothelial Notch signaling. However, thus far in mice, only Notch1 appears essential to the establishment of HSCs. It is not yet clear whether somite-intrinsic and somite-to-PLM Notch signaling events are conserved in mammalian species, and it is also unclear whether Notch1 mediates each signaling event or whether other receptors may be involved. Further studies focused on ligand-receptor specificity, downstream targets, and effects of Notch signaling level on hematopoiesis are necessary. Furthermore, the need for Notch downregulation within budding hematopoietic clusters is just beginning to be appreciated. Defining the molecular mechanisms of Notch shutdown, and the reason it is required for HSC establishment, may inform future in vitro HSC derivation strategies.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Clements WK, Traver D. Signalling pathways that control vertebrate haematopoietic stem cell specification. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13(5):336–348. doi: 10.1038/nri3443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kumano K, et al. Notch1 but not Notch2 is essential for generating hematopoietic stem cells from endothelial cells. Immunity. 2003;18(5):699–711. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00117-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hadland BK, et al. A requirement for Notch1 distinguishes 2 phases of definitive hematopoiesis during development. Blood. 2004;104(10):3097–3105. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-03-1224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burns CE, et al. Hematopoietic stem cell fate is established by the Notch-Runx pathway. Genes Dev. 2005;19(19):2331–2342. doi: 10.1101/gad.1337005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nakagawa M, et al. AML1/Runx1 rescues Notch1-null mutation-induced deficiency of para-aortic splanchnopleural hematopoiesis. Blood. 2006;108(10):3329–3334. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-019570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen MJ, et al. Runx1 is required for the endothelial to haematopoietic cell transition but not thereafter. Nature. 2009;457(7231):887–891. doi: 10.1038/nature07619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kissa K, Herbomel P. Blood stem cells emerge from aortic endothelium by a novel type of cell transition. Nature. 2010;464(7285):112–115. doi: 10.1038/nature08761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davis RL, Turner DL. Vertebrate hairy and Enhancer of split related proteins: transcriptional repressors regulating cellular differentiation and embryonic patterning. Oncogene. 2001;20(58):8342–8357. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guiu J, et al. Hes repressors are essential regulators of hematopoietic stem cell development downstream of Notch signaling. J Exp Med. 2013;210(1):71–84. doi: 10.1084/jem.20120993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsai FY, et al. An early haematopoietic defect in mice lacking the transcription factor GATA-2. Nature. 1994;371(6494):221–226. doi: 10.1038/371221a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iso T, Kedes L, Hamamori Y. HES and HERP families: multiple effectors of the Notch signaling pathway. J Cell Physiol. 2003;194(3):237–255. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robert-Moreno A, et al. RBPjkappa-dependent Notch function regulates Gata2 and is essential for the formation of intra-embryonic hematopoietic cells. Development. 2005;132(5):1117–1126. doi: 10.1242/dev.01660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nottingham WT, et al. Runx1-mediated hematopoietic stem-cell emergence is controlled by a Gata/Ets/SCL-regulated enhancer. Blood. 2007;110(13):4188–4197. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-07-100883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen W, Casey Corliss D. Three modules of zebrafish Mind bomb work cooperatively to promote Delta ubiquitination and endocytosis. Developmental biology. 2004;267(2):361–373. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2003.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Itoh M, et al. Mind bomb is a ubiquitin ligase that is essential for efficient activation of Notch signaling by Delta. Dev Cell. 2003;4(1):67–82. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00409-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deblandre GA, Lai EC, Kintner C. <i>Xenopus</i> Neuralized Is a Ubiquitin Ligase that Interacts with XDelta1 and Regulates Notch Signaling. Developmental cell. 2001;1(6):795–806. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(01)00091-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yeh E, et al. Neuralized functions as an E3 ubiquitin ligase during <i>Drosophila</i> development. Current biology. 2001;11(21):1675–1679. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00527-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pavlopoulos E, et al. < i>neuralized</i> Encodes a Peripheral Membrane Protein Involved in Delta Signaling and Endocytosis. Developmental cell. 2001;1(6):807–816. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(01)00093-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lai EC, et al. < i>Drosophila</i> Neuralized Is a Ubiquitin Ligase that Promotes the Internalization and Degradation of Delta. Developmental cell. 2001;1(6):783–794. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(01)00092-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gordon WR, et al. Structural basis for autoinhibition of Notch. Nature structural & molecular biology. 2007;14(4):295–300. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nichols JT, Miyamoto A, Weinmaster G. Notch signaling–constantly on the move. Traffic. 2007;8(8):959–969. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2007.00592.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parks AL, et al. Ligand endocytosis drives receptor dissociation and activation in the Notch pathway. Development. 2000;127(7):1373–1385. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.7.1373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kao HY, et al. A histone deacetylase corepressor complex regulates the Notch signal transduction pathway. Genes Dev. 1998;12(15):2269–2277. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.15.2269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Castel D, et al. Dynamic binding of RBPJ is determined by Notch signaling status. Genes Dev. 2013;27(9):1059–1071. doi: 10.1101/gad.211912.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lewis J. Notch signalling and the control of cell fate choices in vertebrates. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 1998;9(6):583–589. doi: 10.1006/scdb.1998.0266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Artavanis-Tsakonas S, Rand MD, Lake RJ. Notch signaling: cell fate control and signal integration in development. Science. 1999;284(5415):770–776. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5415.770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bigas A, Robert-Moreno A, Espinosa L. The Notch pathway in the developing hematopoietic system. Int J Dev Biol. 2010;54(6–7):1175–1188. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.093049ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Medvinsky A, Rybtsov S, Taoudi S. Embryonic origin of the adult hematopoietic system: advances and questions. Development. 2011;138(6):1017–1031. doi: 10.1242/dev.040998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huber TL, et al. Haemangioblast commitment is initiated in the primitive streak of the mouse embryo. Nature. 2004;432(7017):625–630. doi: 10.1038/nature03122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dzierzak E, Speck NA. Of lineage and legacy: the development of mammalian hematopoietic stem cells. Nat Immunol. 2008;9(2):129–136. doi: 10.1038/ni1560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bertrand JY, et al. Three pathways to mature macrophages in the early mouse yolk sac. Blood. 2005;106(9):3004–3011. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-02-0461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Palis J, et al. Development of erythroid and myeloid progenitors in the yolk sac and embryo proper of the mouse. Development. 1999;126(22):5073–5084. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.22.5073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen MJ, et al. Erythroid/myeloid progenitors and hematopoietic stem cells originate from distinct populations of endothelial cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;9(6):541–552. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jaffredo T, et al. Tracing the progeny of the aortic hemangioblast in the avian embryo. Dev Biol. 2000;224(2):204–214. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jaffredo T, et al. Intraaortic hemopoietic cells are derived from endothelial cells during ontogeny. Development. 1998;125(22):4575–4583. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.22.4575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rhodes KE, et al. The emergence of hematopoietic stem cells is initiated in the placental vasculature in the absence of circulation. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2(3):252–263. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gordon-Keylock S, et al. Mouse extraembryonic arterial vessels harbor precursors capable of maturing into definitive HSCs. Blood. 2013;122(14):2338–2345. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-12-470971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.de Bruijn MF, et al. Definitive hematopoietic stem cells first develop within the major arterial regions of the mouse embryo. EMBO J. 2000;19(11):2465–2474. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.11.2465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li Z, et al. Mouse embryonic head as a site for hematopoietic stem cell development. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;11(5):663–675. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nakano H, et al. Haemogenic endocardium contributes to transient definitive haematopoiesis. Nat Commun. 2013;4:1564. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Herbomel P, Thisse B, Thisse C. Ontogeny and behaviour of early macrophages in the zebrafish embryo. Development. 1999;126(17):3735–3745. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.17.3735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bertrand JY, et al. Notch signaling distinguishes 2 waves of definitive hematopoiesis in the zebrafish embryo. Blood. 2010;115(14):2777–2783. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-09-244590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gering M, Patient R. Hedgehog signaling is required for adult blood stem cell formation in zebrafish embryos. Dev Cell. 2005;8(3):389–400. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Robert-Moreno A, et al. The notch pathway positively regulates programmed cell death during erythroid differentiation. Leukemia. 2007;21(7):1496–1503. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vogeli KM, et al. A common progenitor for haematopoietic and endothelial lineages in the zebrafish gastrula. Nature. 2006;443(7109):337–339. doi: 10.1038/nature05045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chun CZ, et al. Fli+ etsrp+ hemato-vascular progenitor cells proliferate at the lateral plate mesoderm during vasculogenesis in zebrafish. PloS one. 2011;6(2):e14732. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lee CY, et al. Notch signaling functions as a cell-fate switch between the endothelial and hematopoietic lineages. Curr Biol. 2009;19(19):1616–1622. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.07.073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bresciani E, et al. Zebrafish numb and numblike are involved in primitive erythrocyte differentiation. PLoS One. 2010;5(12):e14296. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jordan H. Aortic cell clusters in vertebrate embryos. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1917;3(3):149. doi: 10.1073/pnas.3.3.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Garcia-Porrero JA, Godin IE, Dieterlen-Lievre F. Potential intraembryonic hemogenic sites at pre-liver stages in the mouse. Anat Embryol (Berl) 1995;192(5):425–435. doi: 10.1007/BF00240375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ciau-Uitz A, Liu F, Patient R. Genetic control of hematopoietic development in Xenopus and zebrafish. Int J Dev Biol. 2010;54(6–7):1139–1149. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.093055ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nishikawa SI, et al. Progressive lineage analysis by cell sorting and culture identifies FLK1+VE-cadherin+ cells at a diverging point of endothelial and hemopoietic lineages. Development. 1998;125(9):1747–1757. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.9.1747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pola R, et al. The morphogen Sonic hedgehog is an indirect angiogenic agent upregulating two families of angiogenic growth factors. Nat Med. 2001;7(6):706–711. doi: 10.1038/89083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lawson ND, Vogel AM, Weinstein BM. sonic hedgehog and vascular endothelial growth factor act upstream of the Notch pathway during arterial endothelial differentiation. Dev Cell. 2002;3(1):127–136. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00198-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Williams C, et al. Hedgehog signaling induces arterial endothelial cell formation by repressing venous cell fate. Dev Biol. 2010;341(1):196–204. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.02.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vokes SA, et al. Hedgehog signaling is essential for endothelial tube formation during vasculogenesis. Development. 2004;131(17):4371–4380. doi: 10.1242/dev.01304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Brown LA, et al. Insights into early vasculogenesis revealed by expression of the ETS-domain transcription factor Fli-1 in wild-type and mutant zebrafish embryos. Mech Dev. 2000;90(2):237–252. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(99)00256-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wilkinson RN, et al. Hedgehog signaling via a calcitonin receptor-like receptor can induce arterial differentiation independently of VEGF signaling in zebrafish. Blood. 2012;120(2):477–488. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-10-383729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cleaver O, Krieg PA. VEGF mediates angioblast migration during development of the dorsal aorta in Xenopus. Development. 1998;125(19):3905–3914. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.19.3905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lawson ND, et al. Notch signaling is required for arterial-venous differentiation during embryonic vascular development. Development. 2001;128(19):3675–3683. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.19.3675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Grego-Bessa J, et al. Notch signaling is essential for ventricular chamber development. Dev Cell. 2007;12(3):415–429. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Adams RH, et al. The cytoplasmic domain of the ligand ephrinB2 is required for vascular morphogenesis but not cranial neural crest migration. Cell. 2001;104(1):57–69. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00191-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Adams RH, et al. Roles of ephrinB ligands and EphB receptors in cardiovascular development: demarcation of arterial/venous domains, vascular morphogenesis, and sprouting angiogenesis. Genes Dev. 1999;13(3):295–306. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.3.295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Foo SS, et al. Ephrin-B2 controls cell motility and adhesion during blood-vessel-wall assembly. Cell. 2006;124(1):161–173. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang HU, Chen ZF, Anderson DJ. Molecular distinction and angiogenic interaction between embryonic arteries and veins revealed by ephrin-B2 and its receptor Eph-B4. Cell. 1998;93(5):741–753. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81436-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Herbert SP, et al. Arterial-venous segregation by selective cell sprouting: an alternative mode of blood vessel formation. Science. 2009;326(5950):294–298. doi: 10.1126/science.1178577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lawson ND, et al. phospholipase C gamma-1 is required downstream of vascular endothelial growth factor during arterial development. Genes Dev. 2003;17(11):1346–1351. doi: 10.1101/gad.1072203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kim PG, et al. Signaling axis involving Hedgehog, Notch, and Scl promotes the embryonic endothelial-to-hematopoietic transition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(2):E141–E150. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1214361110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Burns CE, et al. A genetic screen in zebrafish defines a hierarchical network of pathways required for hematopoietic stem cell emergence. Blood. 2009;113(23):5776–5782. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-12-193607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Quillien A, et al. Distinct Notch signaling outputs pattern the developing arterial system. Development. 2014;141(7):1544–1552. doi: 10.1242/dev.099986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kohli V, et al. Arterial and venous progenitors of the major axial vessels originate at distinct locations. Dev Cell. 2013;25(2):196–206. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zhong TP, et al. Gridlock signalling pathway fashions the first embryonic artery. Nature. 2001;414(6860):216–220. doi: 10.1038/35102599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Weinstein BM, et al. Gridlock, a localized heritable vascular patterning defect in the zebrafish. Nat Med. 1995;1(11):1143–1147. doi: 10.1038/nm1195-1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhong TP, et al. gridlock, an HLH gene required for assembly of the aorta in zebrafish. Science. 2000;287(5459):1820–1824. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5459.1820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rowlinson JM, Gering M. Hey2 acts upstream of Notch in hematopoietic stem cell specification in zebrafish embryos. Blood. 2010;116(12):2046–2056. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-11-252635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gessler M, et al. Mouse gridlock: no aortic coarctation or deficiency, but fatal cardiac defects in Hey2 −/− mice. Curr Biol. 2002;12(18):1601–1604. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)01150-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Fischer A, et al. The Notch target genes Hey1 and Hey2 are required for embryonic vascular development. Genes Dev. 2004;18(8):901–911. doi: 10.1101/gad.291004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kokubo H, et al. Mouse hesr1 and hesr2 genes are redundantly required to mediate Notch signaling in the developing cardiovascular system. Dev Biol. 2005;278(2):301–309. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Seo S, et al. The forkhead transcription factors, Foxc1 and Foxc2, are required for arterial specification and lymphatic sprouting during vascular development. Dev Biol. 2006;294(2):458–470. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hayashi H, Kume T. Foxc transcription factors directly regulate Dll4 and Hey2 expression by interacting with the VEGF-Notch signaling pathways in endothelial cells. PLoS One. 2008;3(6):e2401. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Robert-Moreno A, et al. Impaired embryonic haematopoiesis yet normal arterial development in the absence of the Notch ligand Jagged1. EMBO J. 2008;27(13):1886–1895. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Krebs LT, et al. Haploinsufficient lethality and formation of arteriovenous malformations in Notch pathway mutants. Genes Dev. 2004;18(20):2469–2473. doi: 10.1101/gad.1239204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Krebs LT, et al. Notch signaling is essential for vascular morphogenesis in mice. Genes Dev. 2000;14(11):1343–1352. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Duarte A, et al. Dosage-sensitive requirement for mouse Dll4 in artery development. Genes Dev. 2004;18(20):2474–2478. doi: 10.1101/gad.1239004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Trindade A, et al. Overexpression of delta-like 4 induces arterialization and attenuates vessel formation in developing mouse embryos. Blood. 2008;112(5):1720–1729. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-09-112748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Herbert SP, Stainier DY. Molecular control of endothelial cell behaviour during blood vessel morphogenesis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2011;12(9):551–564. doi: 10.1038/nrm3176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Clarke RL, et al. The expression of Sox17 identifies and regulates haemogenic endothelium. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15(5):502–510. doi: 10.1038/ncb2724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Sorensen I, Adams RH, Gossler A. DLL1-mediated Notch activation regulates endothelial identity in mouse fetal arteries. Blood. 2009;113(22):5680–5688. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-08-174508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Yoon MJ, et al. Mind bomb-1 is essential for intraembryonic hematopoiesis in the aortic endothelium and the subaortic patches. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28(15):4794–4804. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00436-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Leung A, et al. Uncoupling VEGFA functions in arteriogenesis and hematopoietic stem cell specification. Dev Cell. 2013;24(2):144–158. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Becker PM, et al. Neuropilin-1 regulates vascular endothelial growth factor-mediated endothelial permeability. Circ Res. 2005;96(12):1257–1265. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000171756.13554.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Soker S, et al. Neuropilin-1 is expressed by endothelial and tumor cells as an isoform-specific receptor for vascular endothelial growth factor. Cell. 1998;92(6):735–745. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81402-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Gridley T. Notch signaling in vascular development and physiology. Development. 2007;134(15):2709–2718. doi: 10.1242/dev.004184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.You LR, et al. Suppression of Notch signalling by the COUP-TFII transcription factor regulates vein identity. Nature. 2005;435(7038):98–104. doi: 10.1038/nature03511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Sorensen LK, et al. Loss of distinct arterial and venous boundaries in mice lacking endoglin, a vascular-specific TGFbeta coreceptor. Dev Biol. 2003;261(1):235–250. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(03)00158-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Urness LD, Sorensen LK, Li DY. Arteriovenous malformations in mice lacking activin receptor-like kinase-1. Nat Genet. 2000;26(3):328–331. doi: 10.1038/81634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Clements WK, et al. A somitic Wnt16/Notch pathway specifies haematopoietic stem cells. Nature. 2011;474(7350):220–224. doi: 10.1038/nature10107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Wright GJ, et al. DeltaC and DeltaD interact as Notch ligands in the zebrafish segmentation clock. Development. 2011;138(14):2947–2956. doi: 10.1242/dev.066654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Lee Y, et al. FGF signalling specifies haematopoietic stem cells through its regulation of somitic Notch signalling. Nat Commun. 2014;5:5583. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Pouget C, et al. FGF signalling restricts haematopoietic stem cell specification via modulation of the BMP pathway. Nat Commun. 2014;5:5588. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Kobayashi I, et al. Jam1a-Jam2a interactions regulate haematopoietic stem cell fate through Notch signalling. Nature. 2014;512(7514):319–323. doi: 10.1038/nature13623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.de Pater E, et al. Gata2 is required for HSC generation and survival. J Exp Med. 2013;210(13):2843–2850. doi: 10.1084/jem.20130751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Butko E, et al. Gata2b is a restricted early regulator of hemogenic endothelium in the zebrafish embryo. Development. 2015;142(6):1050–1061. doi: 10.1242/dev.119180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Kim AD, et al. Discrete Notch signaling requirements in the specification of hematopoietic stem cells. EMBO J. 2014 doi: 10.15252/embj.201488784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Nornes S, et al. Zebrafish Pax9 encodes two proteins with distinct C-terminal transactivating domains of different potency negatively regulated by adjacent N-terminal sequences. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(43):26914–26923. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.43.26914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Charbord P, et al. A systems biology approach for defining the molecular framework of the hematopoietic stem cell niche. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;15(3):376–391. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Pouget C, et al. Somite-derived cells replace ventral aortic hemangioblasts and provide aortic smooth muscle cells of the trunk. Development. 2006;133(6):1013–1022. doi: 10.1242/dev.02269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Ohata E, et al. Notch signal is sufficient to direct an endothelial conversion from non- endothelial somitic cells conveyed to the aortic region by CXCR4. Dev Biol. 2009;335(1):33–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Sato Y, et al. Notch mediates the segmental specification of angioblasts in somites and their directed migration toward the dorsal aorta in avian embryos. Dev Cell. 2008;14(6):890–901. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Pouget C, Pottin K, Jaffredo T. Sclerotomal origin of vascular smooth muscle cells and pericytes in the embryo. Dev Biol. 2008;315(2):437–447. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.12.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Wasteson P, et al. Developmental origin of smooth muscle cells in the descending aorta in mice. Development. 2008;135(10):1823–1832. doi: 10.1242/dev.020958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Richard C, et al. Endothelio-mesenchymal interaction controls runx1 expression and modulates the notch pathway to initiate aortic hematopoiesis. Dev Cell. 2013;24(6):600–611. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Li Y, et al. Inflammatory signaling regulates embryonic hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell production. Genes Dev. 2014 doi: 10.1101/gad.253302.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Orelio C, et al. Interleukin-1-mediated hematopoietic cell regulation in the aorta- gonad-mesonephros region of the mouse embryo. Blood. 2008;112(13):4895–4904. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-12-123836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Espin-Palazon R, et al. Proinflammatory signaling regulates hematopoietic stem cell emergence. Cell. 2014;159(5):1070–1085. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.10.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Tang Y, et al. Notch1 activation in embryonic VE-cadherin populations selectively blocks hematopoietic stem cell generation and fetal liver hematopoiesis. Transgenic Res. 2013;22(2):403–410. doi: 10.1007/s11248-012-9637-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Lizama CO, et al. Repression of arterial genes in hemogenic endothelium is sufficient for haematopoietic fate acquisition. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7739. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Del Monte G, et al. Monitoring Notch1 activity in development: evidence for a feedback regulatory loop. Dev Dyn. 2007;236(9):2594–2614. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Wei Y, et al. Ncor2 is required for hematopoietic stem cell emergence by inhibiting Fos signaling in zebrafish. Blood. 2014;124(10):1578–1585. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-11-541391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Radtke F, MacDonald HR, Tacchini-Cottier F. Regulation of innate and adaptive immunity by Notch. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13(6):427–437. doi: 10.1038/nri3445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Poulos MG, et al. Endothelial Jagged-1 is necessary for homeostatic and regenerative hematopoiesis. Cell Rep. 2013;4(5):1022–1034. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.07.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Carlesso N, et al. Notch1-induced delay of human hematopoietic progenitor cell differentiation is associated with altered cell cycle kinetics. Blood. 1999;93(3):838–848. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]