Abstract

BACKGROUND

Urogenital Chlamydia trachomatis infection remains prevalent and causes substantial reproductive morbidity. Recent studies have raised concern about the efficacy of azithromycin for the treatment of chlamydia infection.

METHODS

We conducted a randomized trial comparing oral azithromycin with doxycycline for the treatment of urogenital chlamydia infection among adolescents in youth correctional facilities, to evaluate the noninferiority of azithromycin (1 g in one dose) to doxycycline (100 mg twice daily for 7 days). The treatment was directly observed. The primary end point was treatment failure at 28 days after treatment initiation, with treatment failure determined on the basis of nucleic acid amplification testing, sexual history, and outer membrane protein A (OmpA) genotyping of C. trachomatis strains.

RESULTS

Among the 567 participants enrolled, 284 were randomly assigned to receive azithromycin, and 283 were randomly assigned to receive doxycycline. A total of 155 participants in each treatment group (65% male) made up the per-protocol population. There were no treatment failures in the doxycycline group. In the azithromycin group, treatment failure occurred in 5 participants (3.2%; 95% confidence interval, 0.4 to 7.4%). The observed difference in failure rates between the treatment groups was 3.2 percentage points, with an upper boundary of the 90% confidence interval of 5.9 percentage points, which exceeded the prespecified absolute 5-percentage-point cutoff for establishing the noninferiority of azithromycin.

CONCLUSIONS

In the context of a closed population receiving directly observed treatment for urogenital chlamydia infection, the efficacy of azithromycin was 97%, and the efficacy of doxycycline was 100%. The noninferiority of azithromycin was not established in this setting. (Funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT00980148.)

Urogenital chlamydia trachomatis infection is the most prevalent bacterial sexually transmitted infection in the United States and worldwide.1,2 Females are disproportionately affected by this infection because of the risk of pelvic inflammatory disease, which can lead to ectopic pregnancy and infertility. Efforts to prevent and control chlamydia infection, which have been aimed mainly toward the reduction of sequelae, have not diminished the high prevalence.

Along with screening, the provision of effective treatment is a cornerstone of chlamydia control programs. For the treatment of chlamydia infection, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends oral administration of either 1 g of azithromycin in a single dose or 100 mg of doxycycline twice daily for 7 days.3 These recommendations are supported by a meta-analysis of 12 randomized clinical trials, which showed that the efficacy of azithromycin against chlamydia was 97%, and that of doxycycline was 98%4; however, these trials had limitations. Most of the trials used tests that were less sensitive than the currently recommended nucleic acid amplification tests,3 which may have led to an underestimation of the rates of treatment failure. Adherence to doxycycline treatment was not ensured, which is important because non-adherence may lead to treatment failure.5,6 Repeat chlamydia exposure from partners could not be controlled, which made it difficult to determine whether repeat positive tests after therapy indicated treatment failure or reinfection. Finally, the studies had a single test of cure within 2 to 5 weeks after treatment but did not have a repeat test at a later time to evaluate patients for relapse from incomplete eradication of persistent noncultivable chlamydial forms, which has been described in in vitro studies.7,8

Some studies of chlamydia in which nucleic acid amplification tests have been used have raised concern about the efficacy of azithromycin. Three studies of nongonococcal urethritis showed azithromycin efficacy of less than 90% in symptomatic chlamydia-infected males.9-11 In two chlamydia studies involving female participants — a randomized clinical trial of azithromycin versus rifalazil and a longitudinal study of repeat chlamydia infection — the efficacy of azithromycin was 92%.12,13 To address the limitations of previous studies, we conducted a phase 3, open-label, randomized trial of chlamydia treatment among youth in correctional facilities to assess whether azithromycin is non-inferior to doxycycline. Youth correctional facilities were ideal sites for this study because the prevalence of chlamydia infection in such facilities is high,14-16 residents of youth correctional facilities are usually not reexposed to untreated partners, treatment is directly observed, and chlamydia exposure from new partners can be minimized by screening and treating all persons at intake and by constant staff supervision, which limits the opportunities for sexual activities. We obtained a sexual history and performed outer membrane protein A (OmpA) genotyping on C. trachomatis strains to more accurately classify treatment outcomes.

METHODS

STUDY DESIGN AND PARTICIPANTS

We enrolled males and females 12 to 21 years of age who were residing in four long-term, sex-segregated youth correctional facilities in Los Angeles. The study began in December 2009 and was initially limited to female participants. Because of the slow accrual of participants, higher-than-expected rates of early discharge from the facilities, and emerging data suggesting that cure rates with azithromycin were lower among chlamydia-infected males than previous studies had indicated,9 the protocol was amended to include male participants, beginning in August 2011.

Nucleic acid amplification testing to screen for chlamydia (APTIMA Combo 2, Gen-Probe) is routinely performed on first-catch urine specimens obtained from residents of Los Angeles County youth correctional facilities at intake; routine genital examinations are also performed within 96 hours after intake. Study staff recruited residents who had a positive screening nucleic acid amplification test result and, after obtaining written informed consent, reviewed the eligibility criteria and enrolled eligible residents. The exclusion criteria were pregnancy, breast-feeding, gonorrhea coinfection, allergy to tetracyclines or macrolides, previous photosensitivity from doxycycline, an inability to swallow pills, receipt of an antibiotic with antichlamydial activity within 21 days before screening or between screening and enrollment, concomitant infection requiring treatment with an antibiotic agent that had antichlamydial activity, and pelvic inflammatory disease or epididymitis. Study participation was voluntary. Refusal to participate in the study by eligible residents was uncommon, and no participants withdrew from the study. After enrollment, follow-up study visits occurred in up to 23 Los Angeles County youth correctional facilities (some participants were transferred from the 4 facilities where they had been enrolled to different facilities during the course of the study). The full details of the study procedures are provided in the protocol, available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org.

STUDY OVERSIGHT

The study was approved by the institutional review board at the University of Alabama at Birmingham and at the County of Los Angeles Public Health Department, as well as by the Superior Court of California County of Los Angeles Juvenile Division, the County of Los Angeles Probation Department, and Office for Human Research Protections, Department of Health and Human Services. A data and safety monitoring board convened annually. Data were collected by Los Angeles County study staff, managed by FHI 360 (a nonprofit human development organization), and analyzed by statisticians from the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences. The study drugs were purchased from a pharmacy in Los Angeles with study funds from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. All the authors vouch for the accuracy and completeness of the data and analyses presented and for the fidelity of the study to the protocol.

STUDY PROCEDURES

At enrollment, participants underwent an interview (regarding demographic characteristics, previous sexually transmitted infections, sexual behavior, contraception, and urogenital or gastrointestinal symptoms), provided first-catch urine specimens for nucleic acid amplification testing (to confirm chlamydia infection), and were randomly assigned, in a 1:1 ratio, with the use of a block randomization scheme (with randomization performed separately within each facility) to receive the CDC-recommended azithromycin regimen or doxycycline regimen. The oral intake of all doses of study drug was directly observed by youth correctional facility staff. Two database systems were reviewed for previous chlamydia infections: STD Casewatch Millennium and the Los Angeles County Public Health Laboratory MISYS database system.

Participants whose chlamydia test results at enrollment were negative were categorized as not able to be evaluated, and their participation in the study was discontinued. Participants who had a positive chlamydia test result at enrollment and who were still in a youth correctional facility at day 28 attended a first follow-up on that day; were interviewed regarding symptoms, sexual behaviors, antibiotics taken, and furloughs from the correctional facility; and provided a first-catch urine specimen for the test of cure by nucleic acid amplification testing. The timing of the test of cure was chosen to limit possible false positive nucleic acid amplification test results that can occur as a result of residual nucleic acids from dead organisms that have not yet been cleared; studies have reported C. trachomatis nucleic acid shedding 2 to 3 weeks after therapy.17-20 Youth correctional facility clinic records were reviewed for medications and interim pelvic inflammatory disease or epididymitis.

Participants who tested positive for chlamydia at the first follow-up were initially classified as having possible treatment failure, and their participation was complete, with further treatment administered in accordance with routine practice at the youth correctional facilities. Participants who tested negative for chlamydia at the first follow-up and who were still in a youth correctional facility on day 67 attended a second follow-up on that day for repeat nucleic acid amplification testing (to evaluate for persisting chlamydia that was not identified at the first follow-up) and for an interview in which the same information was collected as at the day 28 follow-up. Participants who tested positive for chlamydia at the first or second follow-up had OmpA genotyping performed on their urine specimens with the use of reported methods21 to assess for concordant strains (identical ompA sequences); participants with suspected treatment failure had genotyping performed on urine specimens from both the enrollment visit and the follow-up visit.

OUTCOMES AND POPULATIONS USED FOR ANALYSES

The primary outcome was treatment failure at the first follow-up, which was defined as a positive test for chlamydia and concordant C. trachomatis strains at baseline and follow-up; if genotyping was unsuccessful (i.e., insufficient number of ompA copies), participants could not have had unsupervised furloughs and could not have had sex (self-reported) between enrollment and the follow-up. Participants with discordant strains were presumed to have new infections and were not considered to have treatment failure. The secondary outcomes included treatment efficacy based on the results of tests from both follow-up visits, as well as safety.

The primary analysis population for efficacy and safety was the per-protocol population, in accordance with International Conference on Harmonisation guidelines for a noninferiority study.22 An intention-to-treat approach is considered to be nonconservative in noninferiority studies, because dropouts and withdrawals may reduce the magnitude of the difference in efficacy between treatments.22 Thus, we used the per-protocol population, which comprised participants who completed therapy, defined as patients who received either a single dose of azithromycin or at least 10 doses of doxycycline and whose status with regard to treatment failure could be established at the first follow-up; the use of at least 10 doses of doxycycline for the evaluation of outcome was based on a doxycycline adherence study in which a 100% cure rate was shown in association with this degree of adherence.5 Participants were considered not able to be evaluated for the primary outcome if they were not tested at the first follow-up, had negative results of the chlamydia test at enrollment, or vomited the treatment within 1 hour after taking it (without the medication being readministered).

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

The goal of noninferiority trials is to determine whether the efficacy of a treatment is no worse than that of another treatment.23 This noninferiority study was designed to test the null hypothesis that the absolute rate of azithromycin treatment failure would be at least 5 percentage points higher than the absolute rate of doxycycline treatment failure against the alternative hypothesis that there would be no difference between regimens, with a failure rate of 3% for both (a rate that was based on the results of the meta-analysis).4 The decision to use the difference cutoff of 5 percentage points was based on the reported high cure rates for both treatments4; this difference was considered by the investigative team to be an appropriate cutoff to establish the clinical noninferiority of azithromycin to doxycycline. It was estimated that for the study to have 90% power to test the hypothesis at a one-sided 0.10 significance level, the per-protocol population would need to include 153 participants in each group. The failure rate was estimated with binomial proportion and 95% confidence intervals. One-sided 90% exact confidence intervals were used to estimate the difference in the failure rates between the two treatments, which is appropriate for a noninferiority study and which is consistent with the one-sided significance level of 0.10 that was used for the determination of the sample size. Analyses were performed with SAS software, version 9.3 (SAS Institute). Associations between participant characteristics and study group or treatment failure were evaluated with the use of Fisher's exact test or a Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Differences in self-reported versus documented previous chlamydia infection were evaluated with McNemar's test.

RESULTS

STUDY PARTICIPANTS

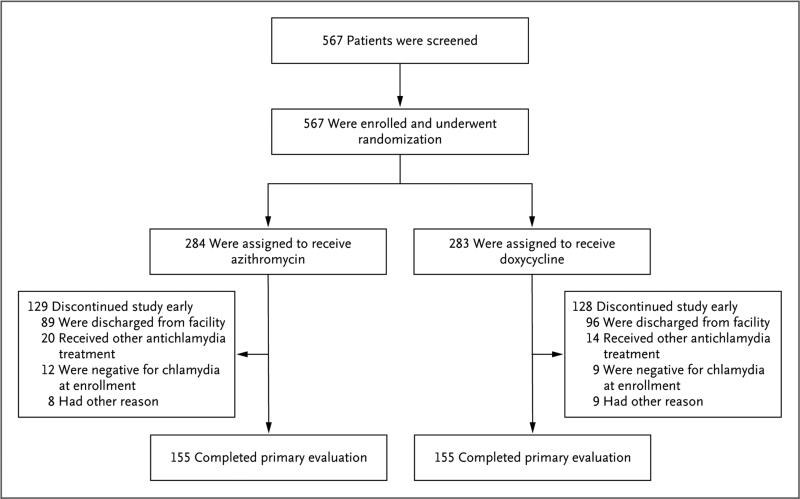

Of the 567 participants enrolled from December 2009 through April 2014, a total of 284 were randomly assigned to receive azithromycin, and 283 were randomly assigned to receive doxycycline (Fig. 1). After early discontinuation was accounted for, 155 participants (55%) in each group completed the first follow-up and made up the per-protocol population. Discharge from the youth correctional facility was the primary reason for early discontinuation. The final study visit was completed in May 2014; in the per-protocol population, 90% of the patients in the azithromycin group and 81% of the patients in the doxycycline group completed both follow-up visits.

Figure 1. Screening, Randomization, and Follow-up.

A total of 567 participants in four youth correctional facilities were enrolled and underwent randomization. In each study group, 155 participants completed the primary evaluation at the first follow-up visit 28 days after treatment initiation and made up the per-protocol population. The most common reason for early discontinuation was discharge from the youth correctional facility, which occurred more often among females than among males (60% vs. 31%). Other reasons for discontinuing study participation in the azithromycin group were as follows: tested positive for gonorrhea (1 participant), pelvic inflammatory disease diagnosis (2), vomited within 1 hour after treatment (2), pregnancy identified after treatment (1), and enrolled without a positive chlamydia screening test (2). Other reasons for discontinuing study participation in the doxycycline group were as follows: pelvic inflammatory disease diagnosis (2), pregnancy identified after treatment (1), enrolled without a positive chlamydia screening test (1), pregnancy possibility (1), physician withdrawal (1), and enrolled while taking antibiotics with potential antichlamydial therapeutic effects (3).

The characteristics of the participants in the per-protocol group at baseline are shown in Table 1. Most male participants (150 of 201, 75%) reported not having urogenital symptoms. The majority of female participants (67 of 109, 61%) reported urogenital symptoms, most commonly abnormal vaginal discharge (54 of 109, 50%). Pelvic inflammatory disease was not diagnosed in any female participant. Previous chlamydia infection was self-reported by 22% of the male participants (44 of 201) and was documented in 20% (40 of 201). Female participants self-reported previous chlamydia infection more often than it was documented (44 [40%] vs. 32 [29%], P = 0.001). Demographic characteristics, frequencies of symptoms, and the rate of reported previous chlamydia infection did not differ significantly between the treatment groups. Sex with a female in the previous 12 months was reported by 198 male participants (99%), and sex with a male was reported by 1 (0.5%). Sex with a male during the previous 12 months was reported by 107 female participants (98%), and sex with a female was reported by 17 (16%). Sex after enrollment was reported by 1 participant: a female who reported having sex with another female in the youth correctional facility. No participants had a furlough from the youth correctional facility during the course of the study.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of the Participants in the Per-Protocol Population.*

| Characteristic | All Participants (N = 310) | Azithromycin (N = 155) | Doxycycline (N = 155) | P Value† |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All participants | ||||

| Sex — no. (%) | 0.74 | |||

| Male | 201 (65) | 102 (66) | 99 (64) | |

| Female | 109 (35) | 53 (34) | 56 (36) | |

| Race — no./total no. (%) | 0.49 | |||

| White | 109/307 (36) | 59/154 (38) | 50/153 (33) | |

| Black | 136/307 (44) | 64/154 (42) | 72/153 (47) | |

| Other | 62/307 (20) | 31/154 (20) | 31/153 (20) | |

| Hispanic ethnic background — no. (%) | 158 (51) | 84 (54) | 74 (48) | 0.09 |

| Median age (range) — yr | 17.0 (13.5-20.4) | 17.1 (14.6-18.9) | 16.9 (13.5-20.4) | 0.07 |

| Previous chlamydia infection — no. (%) | 0.71 | |||

| No | 222 (72) | 113 (73) | 109 (70) | |

| Yes | 88 (28) | 42 (27) | 46 (30) | |

| HIV or AIDS — no. (%) | NA | |||

| Not present | 309/310 (100) | 154/155 (99) | 155/155 (100) | |

| Information not ascertained | 1/310 (<1) | 1/155 (1) | 0 | |

| Median no. of sexual partners in the previous 12 mo (IQR) | 3 (2-6) | 3 (2-6) | 3 (2-6) | 0.57 |

| Median age at first sexual activity (IQR) — yr | 14 (13-14) | 14 (13-15) | 13 (13-14) | 0.04 |

| Male participants | ||||

| Painful urination — no./total no. (%) | 0.86 | |||

| No | 160/201 (80) | 82/102 (80) | 78/99 (79) | |

| Yes | 41/201 (20) | 20/102 (20) | 21/99 (21) | |

| Penile discharge — no./total no. (%) | >0.99 | |||

| No | 191/201 (95) | 97/102 (95) | 94/99 (95) | |

| Yes | 10/201 (5) | 5/102 (5) | 5/99 (5) | |

| Pain in the scrotum or testicle area — no./total no. (%) | ||||

| No | 199/201 (99) | 100/102 (98) | 99/99 (100) | 0.50 |

| Yes | 2/201 (1) | 2/102 (2) | 0 | |

| No previous nongonococcal urethritis — no./total no. (%) | 201/201 (100) | 102/102 (100) | 99/99 (100) | NA |

| No previous epididymitis — no./total no. (%) | 201/201 (100) | 102/102 (100) | 99/99 (100) | NA |

| Female participants | ||||

| Painful urination — no./total no. (%) | >0.99 | |||

| No | 102/109 (94) | 50/53 (94) | 52/56 (93) | |

| Yes | 7/109 (6) | 3/53 (6) | 4/56 (7) | |

| Abnormal vaginal discharge — no./total no. (%) | 0.85 | |||

| No | 55/109 (50) | 26/53 (49) | 29/56 (52) | |

| Yes | 54/109 (50) | 27/53 (51) | 27/56 (48) | |

| Irregular vaginal bleeding — no./total no. (%) | >0.99 | |||

| No | 97/109 (89) | 47/53 (89) | 50/56 (89) | |

| Yes | 12/109 (11) | 6/53 (11) | 6/56 (11) | |

| Pelvic pain — no./total no. (%) | 0.12 | |||

| No | 83/109 (76) | 44/53 (83) | 39/56 (70) | |

| Yes | 26/109 (24) | 9/53 (17) | 17/56 (30) | |

| Previous pelvic inflammatory disease — no./total no. (%) | 0.23 | |||

| No | 107/109 (98) | 51/53 (96) | 56/56 (100) | |

| Yes | 2/109 (2) | 2/53 (4) | 0 | |

| Hormone contraception use — no./total no. (%) | >0.99 | |||

| No | 100/109 (92) | 49/53 (92) | 51/56 (91) | |

| Yes | 9/109 (8) | 4/53 (8) | 5/56 (9) | |

All characteristics, with the exception of the sex of the participants, were self-reported. AIDS denotes acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, HIV human immunodeficiency virus, IQR interquartile range, and NA not applicable.

P values for the differences between the two treatment groups were determined with the use of a Wilcoxon rank-sum test (for age, sex partners in the past 12 months, and age at first sex) or Fisher's exact test (for all other characteristics).

CHLAMYDIA TREATMENT FAILURE AND PREDICTORS

No treatment failures occurred in the doxycycline group (0%; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.0 to 2.4). In the azithromycin group, seven participants (six male and one female) tested positive for chlamydia at the first follow-up; however, two of the males were infected with strains that were discordant with the infecting strains at baseline and were not considered to have treatment failure. Therefore, there were five treatment failures among participants who received azithromycin (3.2%; 95% CI, 0.4 to 7.4): four in male participants (3.9%; 95% CI, 1.1 to 9.7) and one in a female participant (1.9%; 95% CI, 0.0 to 10.1); all the participants with treatment failure were asymptomatic. The difference in failure rate between the treatments was 3.2 percentage points (one-sided 90% CI, 0 to 5.9). Because the upper boundary of the 90% confidence interval exceeded 5 percentage points, the null hypothesis was not rejected, and thus the noninferiority of azithromycin to doxycycline was not established. With only five treatment failures, analyses of participant characteristics associated with treatment failure were limited, and no significant associations were identified.

No doxycycline treatment failures were identified at the second follow-up. A single female participant who received azithromycin tested negative for chlamydia at the first follow-up but tested positive at the second follow-up. When this treatment failure was included with the five that were detected at the first follow-up, the failure rate for azithromycin was calculated as 3.9% (95% CI, 1.4 to 8.2). Of note, OmpA genotyping was unsuccessful in two of the six participants with treatment failure (both were female participants); however, these two participants did not have unsupervised furloughs or report interim sexual activity.

TREATMENT ADHERENCE AND SAFETY

In the azithromycin group, two participants (1%) vomited azithromycin within 1 hour after taking it, and a second dose was administered successfully. In the doxycycline group, 77% of participants received 14 doses; because of the logistic challenges inherent in conducting the study in youth correctional facilities, 2% of participants received 11 doses, 3% received 12 doses, 12% received 13 doses, 6% received 15 doses, and 1% received 16 doses. No participants were excluded from the per-protocol population because they received an insufficient number of doxycycline doses. Adverse events were reported by 23% of the participants in the azithromycin group and by 27% of the participants in the doxycycline group; the most common adverse events reported in both groups were gastrointestinal symptoms. No severe or serious adverse events occurred, and no participants discontinued participation in the study because of an adverse event.

DISCUSSION

In this trial, the noninferiority of azithromycin to doxycycline for the treatment of chlamydia infection was not established. This was not a result of azithromycin having low efficacy; the 97% efficacy of the drug in our study was consistent with that reported in a meta-analysis.4 Rather, it reflects the 100% efficacy of doxycycline. Because doxycycline is not given under direct observation in practice outside institutional settings, the generalizability of our findings is unknown. The two studies that have evaluated patient-reported adherence to doxycycline treatment for chlamydia infection suggest that 3 to 28% of patients miss at least 1 dose.5,6 However, a study in which adherence to doxycycline treatment was evaluated with microprocessor-containing medication bottles suggested that the degree of adherence based on reporting by participants can be an overestimation5; the study showed that although 90% of participants reported taking all doses within 8 days, only 16% actually managed this degree of adherence. Nonadherence to doxycycline therapy contributes to treatment failure. Bachmann et al. reported no treatment failures among 58 participants who took 10 to 14 doses, as compared with treatment failure in 4 of 20 participants (20%) who took fewer than 10 doses.5 Khosropour et al. evaluated doxycycline adherence among males with symptomatic chlamydia urethritis and found treatment failure in 1 of 37 participants (3%) who took 14 doses, versus 2 of 10 participants (20%) who missed at least one dose.6 In our study, we determined adherence through the staff recording directly observed treatment, and our results suggest that doxycycline is up to 100% efficacious against chlamydia among patients who are mostly adherent, whereas azithromycin may be slightly less efficacious, with an occasional treatment failure. When chlamydia treatment is provided in real-world clinical practice, the possibility that the efficacy of doxycycline could be offset by limited adherence should be taken into consideration.

It is unclear why all the treatment failures in our study occurred in azithromycin-treated participants. Resistance to the drug is a consideration, although it is unlikely. High-level azithromycin resistance in human C. trachomatis strains has not been definitively shown, and only in rare cases have “heterotypic” resistant strains been associated with treatment failure.24,25 More recent studies of nongonococcal urethritis have suggested that the efficacy of azithromycin may be lower in males who have symptomatic chlamydia urethritis than previous studies had indicated.4,9-11 Our study was not designed or powered to evaluate the efficacy of azithromycin in symptomatic chlamydia-infected males. However, in a subanalysis of 102 males who received azithromycin, the difference in treatment failure rate between males who reported painful urination and those who did not report it (2 of 20 [10%] and 2 of 82 [2%], respectively) was not significant (P = 0.17), but the results suggest that the efficacy of azithromycin for the treatment of symptomatic chlamydia urethritis deserves further study. Azithromycin levels that are sufficient to eradicate chlamydia may not be achieved in some patients. Only limited studies have shown the presence of therapeutic levels of azithromycin in the female genital tract,26,27 and there are insufficient data on azithromycin levels in the urethra. Even with sufficient levels, it is possible that some organisms are not eradicated in acute infection, as suggested by an in vitro study that showed that doxycycline was more effective than azithromycin in eradicating chlamydia from acutely infected human epithelial cells.28

An important aspect of our study was the use of youth correctional facilities as the sites for the trial. Conducting the trial at these sites minimized the possibility of chlamydia re-exposure from untreated partners, limited exposure from new partners, and enhanced treatment adherence. Another important aspect of this study was the improved accuracy in the detection of treatment failure with the use of nucleic acid amplification testing and OmpA genotyping; the usefulness of the latter method is illustrated by the identification of two male participants who denied having sex after therapy and had repeat chlamydia infection with different strains, which suggested that they were not forthcoming about their sexual history. Because the residents of youth correctional facilities do not undergo routine oropharyngeal or rectal chlamydia screening, it is possible that those two male participants had sex with male residents who had extragenital chlamydia infection. Adding chlamydia testing at day 67 yielded only one treatment failure, which suggests that relapsing or persistent chlamydia infection is probably rare, despite the findings of a study of same-serovar chlamydial infections over a period of 2 to 5 years, which suggested that it may occur.29

Our study had some limitations. First, it was performed in a single geographic location, which may influence the generalizability of the findings. Second, urine specimens were used for chlamydia nucleic acid amplification testing in female participants. During the course of the study, vaginal swabs become the preferred specimen for chlamydia screening by means of nucleic acid amplification testing,30 in part because of the slightly higher sensitivity of this type of testing when vaginal swab samples are used31; however, we continued to test urine specimens for comparison purposes, and it is possible that a small number of infections were undetected. Third, an unexpected challenge in our study was the high rate of early discharge from youth correctional facilities; this may have been due in part to changing trends in juvenile justice policies leading to fewer and shorter incarcerations. The discharge rate led to a need to enroll more participants to achieve the targeted per-protocol population size and influenced sex distribution, with the result that there were almost two times as many males as females in the per-protocol population. Finally, with our sample size and low rate of treatment failure, a small change in the number of failures in either treatment group could alter our conclusions regarding noninferiority. For example, 2 fewer failures in the azithromycin group (3 of 155 in the azithromycin group vs. 0 of 155 in the doxycycline group) would give an upper boundary of the 90% confidence interval of 4.3 percentage points. Therefore, 2 events would influence the determination of noninferiority. Furthermore, we determined that for the observed rates of treatment failure, an additional 130 participants who could be evaluated in each treatment group (almost double our sample size) would be required in order to increase the precision and establish the noninferiority of azithromycin with the use of the prespecified statistical criteria. As we noted above, we used a one-sided significance level of 0.10 for the determination of sample size; decreasing the significance level to 0.05 would have increased the sample-size requirements to an unattainable level.

In conclusion, the noninferiority of azithromycin to doxycycline was not established in our study. However, the efficacy of both types of treatment was high (97% and 100%) in the context of a per-protocol analysis and directly observed and monitored therapy.

Acknowledgments

Supported by the Division of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health (contract number HHSN266200400073C).

Dr. Geisler reports receiving grant support from ActivBiotics Pharma. No other potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

We thank the staff at the County of Los Angeles Department of Public Health, Los Angeles County youth correctional facilities, and of the County of Los Angeles Juvenile Court Health Services for their contributions to completing the study; the staff of the County of Los Angeles Probation Department and Los Angeles County Juvenile Court Health Services for permitting the study to be conducted; Jill Stanton and Linda McNeil from FHI 360 for assistance with study coordination and data management; Melina Boudov, Staeci Morita, Lashawnda Royal, Kirsten Wilson, Kimberly Coffee, Kimberly Givan, Marisol Mejia, and Jennifer Vonghack for assistance with study coordination through the County of Los Angeles Department of Public Health; Carolyn Deal, Barbara Hahn, and Jill Long from the Division of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, National Institute of Allergy and infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, for their support and oversight throughout the development, implementation, analysis and reporting of the study; Dr. Edward Hook from the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) for his review of an earlier version of the manuscript; and Richa Kapil and LaDraka Brown from UAB for their assistance with C. trachomatis OmpA genotyping.

Footnotes

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Sexually transmitted disease surveillance 2013. Department of Health and Human Services; Atlanta: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Global incidence and prevalence of selected curable sexually transmitted infections — 2008. ( http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/rtis/stisestimates/en)

- 3.Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-12):1–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lau CY, Qureshi AK. Azithromycin versus doxycycline for genital chlamydial infections: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Sex Transm Dis. 2002;29:497–502. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200209000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bachmann LH, Stephens J, Richey CM, Hook EW., III Measured versus self-reported compliance with doxycycline therapy for chlamydia-associated syndromes: high therapeutic success rates despite poor compliance. Sex Transm Dis. 1999;26:272–8. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199905000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khosropour CM, Manhart LE, Colom bara DV, et al. Suboptimal adherence to doxycycline and treatment outcomes among men with non-gonococcal urethritis: a prospective cohort study. Sex Transm Infect. 2014;90:3–7. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2013-051174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beatty WL, Morrison RP, Byrne GI. Persistent chlamydiae: from cell culture to a paradigm for chlamydial pathogenesis. Microbiol Rev. 1994;58:686–99. doi: 10.1128/mr.58.4.686-699.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wyrick PB. Chlamydia trachomatis persistence in vitro: an overview. J Infect Dis. 2010;201(Suppl 2):S88–S95. doi: 10.1086/652394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schwebke JR, Rompalo A, Taylor S, et al. Re-evaluating the treatment of nongonococcal urethritis: emphasizing emerging pathogens — a randomized clinical trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:163–70. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Manhart LE, Gillespie CW, Lowens MS, et al. Standard treatment regimens for nongonococcal urethritis have similar but declining cure rates: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56:934–42. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takahashi S, Matsukawa M, Kurimura Y, et al. Clinical efficacy of azithro mycin for male nongonococcal urethritis. J Infect Chemother. 2008;14:409–12. doi: 10.1007/s10156-008-0643-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Geisler WM, Pascual ML, Mathew J, et al. Randomized, double-blind, multicenter safety and efficacy study of rifalazil compared with azithromycin for treatment of uncomplicated genital Chlamydia trachomatis infection in women. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58:4014–9. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02521-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Batteiger BE, Tu W, Ofner S, et al. Repeated Chlamydia trachomatis genital infections in adolescent women. J Infect Dis. 2010;201:42–51. doi: 10.1086/648734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mertz KJ, Voigt RA, Hutchins K, et al. Findings from STD screening of adolescents and adults entering correctional facilities. Sex Transm Dis. 2002;29:834–9. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200212000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bauer HM, Chartier M, Kessell E, et al. Chlamydia screening of youth and young adults in non-clinical settings throughout California. Sex Transm Dis. 2004;31:409–14. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000130456.03464.ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Robertson AA, Thomas CB, St Lawrence JS, Pack R. Predictors of infection with chlamydia or gonorrhea in incarcer ated adolescents. Sex Transm Dis. 2005;32:115–22. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000151419.11934.1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Renault CA, Israelski DM, Levy V, Fuji-kawa BK, Kellogg TA, Klausner JD. Time to clearance of Chlamydia trachomatis ribosomal RNA in women treated for chlamydial infection. Sex Health. 2011;8:69–73. doi: 10.1071/SH10030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morré SA, Sillekens PT, Jacobs MV, et al. Monitoring of Chlamydia trachomatis infections after antibiotic treatment using RNA detection by nucleic acid sequence based amplification. Mol Pathol. 1998;51:149–54. doi: 10.1136/mp.51.3.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Workowski KA, Lampe MF, Wong KG, Watts MB, Stamm WE. Long-term eradication of Chlamydia trachomatis genital infection after antimicrobial therapy: evidence against persistent infection. JAMA. 1993;270:2071–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gaydos CA, Crotchfelt KA, Howell MR, Kralian S, Hauptman P, Quinn TC. Molecular amplification assays to detect chlamydial infections in urine specimens from high school female students and to monitor the persistence of chlamydial DNA after therapy. J Infect Dis. 1998;177:417–24. doi: 10.1086/514207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kapil R, Press CG, Hwang ML, Brown L, Geisler WM. Investigating the epidemiology of repeat Chlamydia trachomatis detection after treatment by using C. trachomatis OmpA genotyping. J Clin Micro-biol. 2015;53:546–9. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02483-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.International Conference on Harmonisation E9 Expert Working Group ICH Harmonised Tripartite Guideline: statistical principles for clinical trials. Stat Med. 1999;18:1905–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Piaggio G, Elbourne DR, Pocock SJ, Evans SJ, Altman DG. Reporting of non-inferiority and equivalence randomized trials: extension of the CONSORT 2010 statement. JAMA. 2012;308:2594–604. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.87802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Somani J, Bhullar VB, Workowski KA, Farshy CE, Black CM. Multiple drug-resistant Chlamydia trachomatis associated with clinical treatment failure. J Infect Dis. 2000;181:1421–7. doi: 10.1086/315372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jones RB, Van der Pol B, Martin DH, Shepard MK. Partial characterization of Chlamydia trachomatis isolates resistant to multiple antibiotics. J Infect Dis. 1990;162:1309–15. doi: 10.1093/infdis/162.6.1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Worm AM, Osterlind A. Azithromycin levels in cervical mucus and plasma after a single 1.0g oral dose for chlamyd ial cervicitis. Genitourin Med. 1995;71:244–6. doi: 10.1136/sti.71.4.244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krohn K. Gynaecological tissue levels of azithromycin. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1991;10:864–8. doi: 10.1007/BF01975844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reveneau N, Crane DD, Fischer E, Caldwell HD. Bactericidal activity of first-choice antibiotics against gamma inter-feron-induced persistent infection of human epithelial cells by Chlamydia trachomatis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49:1787–93. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.5.1787-1793.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dean D, Suchland RJ, Stamm WE. Evidence for long-term cervical persistence of Chlamydia trachomatis by omp1 genotyping. J Infect Dis. 2000;182:909–16. doi: 10.1086/315778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Recommendations for the laboratory-based detection of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae — 2014. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2014;63(RR-02):1–19. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chernesky M, Jang D, Gilchrist J, et al. Head-to-head comparison of second-generation nucleic acid amplification tests for detection of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae on urine samples from female subjects and self-collected vaginal swabs. J Clin Microbiol. 2014;52:2305–10. doi: 10.1128/JCM.03552-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]