Abstract

Excision and end-to-end anastomosis (EPA) has been the preferred urethroplasty technique for short bulbar strictures and is associated with an excellent functional outcome. Driven by concerns over the potential morbidity associated with dividing the urethra, therefore compromising spongiosal blood flow, as well as spongiofibrosis being superficial in the majority of non-traumatic bulbar strictures, the non-transecting technique for bulbar urethroplasty has been developed with the aim of achieving the same success as EPA without the morbidity associated with transection. This manuscript highlights the fundamental principles underlying the ongoing debate—transection or non-transection of the strictured bulbar urethra? The potential advantages of avoiding dividing the corpus spongiosum of the urethra are discussed. The non-transecting anastomotic procedure together with its various modifications are decribed in detail. Our experience with this technique is presented. Non-transecting excision of spongiofibrosis with preservation of well vascularised underlying spongiosum provides an excellent alternative to dividing the urethra during urethroplasty for short non-traumatic proximal bulbar strictures.

Keywords: Anterior urethral strictures, urethroplasty, urethral reconstruction

Introduction

The optimal management of bulbar urethral strictures continues to generate much debate within the reconstructive urological community; endoscopic intervention (dilatation or urethrotomy) vs. urethroplasty, flap vs. graft, dorsal or ventral augmentation, just to mention a few of the controversial issues commonly discussed. Most recently the question of whether to transect the bulbar urethra or not in non-traumatic strictures has been raised (1).

The surgical treatment of bulbar urethral strictures is guided by stricture aetiology, length, location and previous surgical intervention (2). Traditionally the first and simplest form of treatment has been endoscopic instrumentation by dilatation or urethrotomy in the hope that healing by secondary intention will occur before further scarring. The cure rate is only around 60%, and this only in short strictures of the bulbar urethra (3). The long-term success rate and cost effectiveness decreases even further with subsequent attempts at endoscopic intervention (4). Therefore, in patients with bulbar strictures which are refractory to endoscopic manouvres, urethroplasty remains the only curative option (5).

The bulbar urethra is the commonest site for urethral strictures in the developed world. Most are idiopathic, occurring most frequently at the junction of the proximal and middle thirds. Short, sharp strictures in this location (Figure 1) may indeed be congenital in origin due to failure of complete canalisation of the urogenital membrane (6,7). Other common causes of bulbar urethral stricture are iatrogenic (usually following traumatic catheterisation or urethral instrumentation during TURP) and fall-astride perineal injuries. The current literature suggests that when such strictures are short, the best form of urethroplasty is excision of the strictured urethral segment (spongiofibrosis and surrounding corpus spongiosum) and tension-free end-to-end anastomosis of the healthy spatulated edges (EPA) (8,9).

Figure 1.

A typical idiopathic bulbar stricture; short, sharp and at the junction of the proximal and middle thirds; likely congenital in origin.

Traditionally, strictures shorter than 1-2 cm are considered to be amenable to EPA due to concerns regarding tension on the anastomosis leading to increased stricture recurrence, penile shortening and curvature during erection if longer segments are excised (10). Longer strictures requiring excision should be managed by an augmented anastomotic technique in which the ventral spongiosum is anastomosed in an end-to-end fashion and the dorsal aspect augmented with a graft (11). If the stricture is not excised, then a simple oral grafting augmentation procedure is appropriate (12). Nonetheless, recent reports have shown successful EPA for proximal bulbar strictures up to 5 cm long (13).

Transection vs. non-transection for short bulbar strictures

Transection of the urethra for short bulbar strictures was originally challenged at the 2009 American Urological Association (AUA) meeting (14). The debate in favour or against transection with end-to-end anastomosis and any non-transecting technique is based on stricture aetiology and the success rates and complications associated with each treatment modality.

The underlying pathophysiology of short bulbar strictures differs between idiopathic, iatrogenic, inflammatory and post-traumatic (fall-astride) causes even if the strictures are identical in length and location. In the first three, the degree of spongiofibrosis is often surpisingly small, limited to around 10% of the thickness of the urethral wall, with well-preserved healthy underlying corpus spongiosum present (15). This is in contrast to fall-astride injuries in which there is usually full-thickness spongiofibrosis with no remaining vascularised spongiosal tissue (16).

There is therefore no doubt that in traumatic bulbar strictures, transection with complete excision of the strictured segment is mandatory since failure to do so may lead to stricture recurrence in the long term. However, in cases of EPA for non-traumatic bulbar urethral strictures a significant proportion of the excised urethra is indeed healthy vascularised tissue but still requires transection of the corpus spongiosum and, inevitably, also the urethral arteries within it. Although it is not certain whether this disruption of the retrograde urethral blood flow leads to adverse effects in the long-term, preservation of blood supply should be desirable particularly when the distal vascular supply to the urethra is compromised such as the elderly, those with vascular disease, hypospadias, previous urethroplasty and patients who may be candidates for artificial urinary sphincter implantation and might be at increased risk of ischaemic erosion (17).

Urethral transection for short bulbar strictures is also reported to be associated with an 18-22.5% incidence of sexual dysfunction compared to stricturotomy and augmentation (18,19). This is thought to be due to the close anatomical relationship between the bulbar urethra and erectile innervation (20).

EPA is associated with excellent success rates in excess of 95%, sustained in the long-term (21,22). Augmentation urethroplasty using buccal graft in the bulbar urethra also does well with an overall success rate of around 85% (12,23). These results, unlike with anastomotic urethroplasty, deteriorate steadily over time with recurrence rates of up to 58% at 15 years (24).

The key points for and against transection and non-transection are summarised in Table 1. On balance it seems that practice is shifting towards preservation of spongiosal blood flow in short non-traumatic bulbar strictures. Palminteri et al. advocate stricturotomy and graft augmentation rather than excision and anastomosis when feasible, if only to safeguard sexual function (25).

Table 1. Transecting vs. non-transecting techniques.

| Transecting the urethra |

| Allows complete removal of scar tissue reducing risk of restricture |

| >95% success rate in the long term |

| But may cause vascular damage to the urethra |

| But is associated with increased sexual dysfunction |

| Non-transecting the urethra |

| Prevents complete removal of scar tissue leading to stricture recurrence |

| Up to 85% success rate which deteriorates over time |

| But preserves urethral vasculature |

| But therefore causes less sexual dysfunction |

In 2007, Jordan described a modification to EPA in which the proximal urethral blood supply is preserved (17). In proximal bulbar strictures the bulbar arteries are mobilised and preserved. The strictured area is excised and the corpus spongiosum reconstituted over the anastomosis (26). This technique is not appropriate in strictures with significant spongiofibrosis.

We have independently developed the technique of non-transecting anastomotic bulbar urethroplasty with the aim of achieving the same functional outcome as EPA while avoiding the potential morbidity associated with division of the spongiosum and bulbar arteries (27). The dorsal stricturotomy approach to non-transecting urethroplasty allows the versatility of a stepwise approach to stricture management after careful intra-operative assessment of length and degree of spongiofibrosis, starting off with simple stricturoplasty for short, membrane-like strictures, progressing to excision of the spongiofibrosis and end-to-end mucosal anastomosis for longer strictures, to augmentation of even longer strictures with a dorsal patch; all without transecting the urethra.

The augmented nontransected anastomotic urethroplasty is a further modification to this technique (28). This combines partial thickness excision of the spongiofibrosis in the narrowest part of a longer stricture with graft augmentation.

This report provides a detailed description of the non-transecting urethroplasty technique for bulbar urethral strictures and also presents our experience of this procedure.

Surgical technique—non-transecting bulbar urethroplasty

Patients are admitted to hospital on the day of surgery. Prophylactic antibiotics (gentamicin and co-amoxiclav) are administered at induction of anaesthesia. Routine positioning is ‘social’ lithotomy which provides good surgical exposure of the perineum and has a very low incidence of complications (29). The legs are supported in Allen® Yellofin® stirrups. Anti-thromboembolic stockings and pneumatic intermittent calf compression devices are routine. The perineum is shaved, the skin ‘prepped’ using a 2% chlorhexidine gluconate and 70% isopropyl alcohol formulation (ChloraPrep®) and the area draped.

A midline perineal incision is made from the perineo-scrotal junction to about 1 cm from the anal margin (Figure 2A). This is deepened through the subcutaneous tissue and Colles’ fascia to expose the bulbospongiosus muscle. A plane between this and the underlying bulbar urethra is easily created by opening Gallaudet’s fascia. A Turner-Warwick self-retaining ring retractor provides excellent exposure. The bulbospogiosus muscle is divided in the midline and retracted. The bulbar urethra is dissected off the tunica albuginea of the corpora dorsally (Figure 2B) by dividing Buck’s fascia on either side, mobilising it from the distal margin of the bulbospongiosus muscle to the perineal membrane. There is no need to mobilise the bulb of the corpus spongiosum from its attachment to the perineal body, thus preserving the main bulbar arteries.

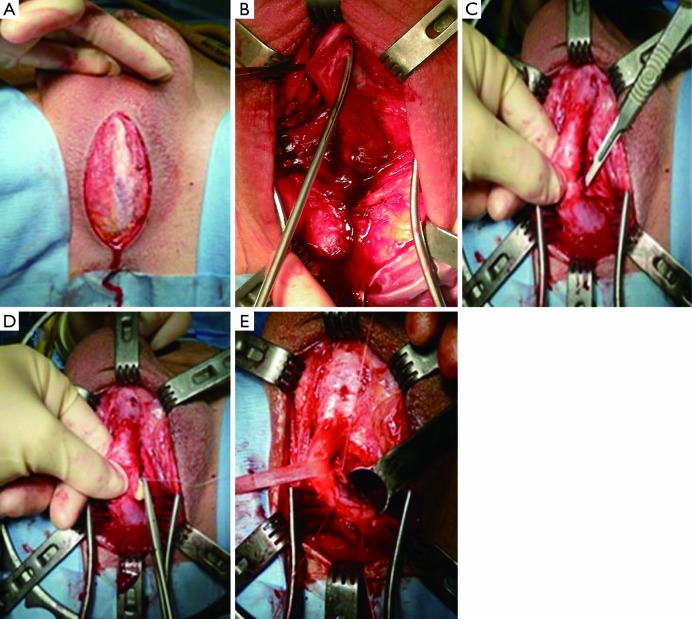

Figure 2.

A midline perineal incision is made (A) and deepened down to the bulbar urethra which is mobilised dorsally off the tunica albuginea of the corpora cavernosa (B). A dorsal stricturotomy is made by cutting down onto a catheter in the urethra at the stricture site (C) and stay sutures positioned (D). A gorget facilitates extension of the stricturotomy into healthy urethra on either side of the stricture (E).

At this point we find it extremely helpful to advance a floppy-tipped hydrophilic guide wire through the stricture, to facilitate identification of the urethral lumen following stricturotomy when the stricture is extremely tight. The level of the stricture is determined by sounding the urethra with a 20F catheter and palpating the point at which it cannot be advanced any further. An incision is then made down onto the catheter in the dorsal midline and stay sutures positioned (Figure 2C,D). With the help of a gorget (Figure 2E), the incision is extended distally into healthy normal calibre urethra and proximally through the stricture into healthy urethra as well.

We prefer a dorsal approach to bulbar urethroplasty as the stricturotomy is carried out through the thinnest part of the spongiosum. Therefore up until this stage in the operation there has been no vascular compromise to the urethra and the decision as to how to proceed is made depending on the location, length and degree of spongiofibrosis which can all be accurately evaluated through this approach.

The stepwise approach to bulbar urethroplasty

When the stricture is effectively only one or two millimeters long we would perform a stricturoplasty rather than excise it. Once the stricturotomy has been made, only an extremely narrow strip of denuded spongiosum remains. The mucosal margins on either side of this are sutured and the longitudinal stricturotomy closed transversely (Figure 3). This is effectively a ‘Heinke-Mikulicz’-type stricturoplasty commonly used in gastro-intestinal surgery (30);

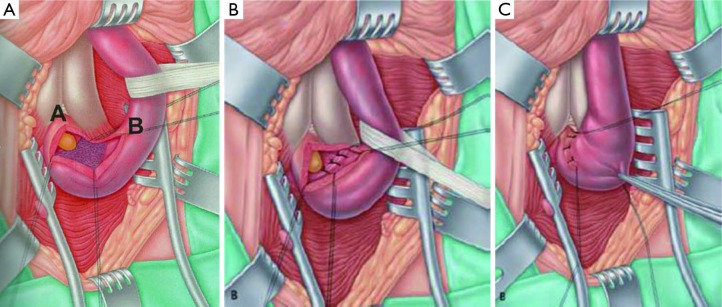

If the stricture is longer than just a membrane (up to two centimetres and sometimes longer), the scarred epithelium with the surrounding spongiofibrosis is carefully excised leaving the healthy underlying spongiosum intact (Figure 4A). The mucosal edges on either side of the excised segment are then sutured to each other (Figure 4B). The ability to bring these two edges together in a tension-free manner after adequate mobilisation of the bulbar urethra and corporal separation if necessary will dictate the length of stricture which can be treated with this technique. The longitudinal dorsal stricturotomy is then closed transversely (Figure 4C);

Strictures which are felt to be too long for a non-transecting anastomotic urethroplasty are instead simply augmented dorsally using buccal mucosal graft (31);

A common finding is a long bulbar stricture in which there is a focal area of more pronounced urethral stenosis. In such cases this short area of more significant spongiofibrosis may be excised in the non-transecting fashion and the urethral plate reconstituted ventrally by a mucosa-to-mucosa anastomosis. The dorsal stricturotomy is then augmented with buccal mucosal graft in what is known as the augmented non-transecting anastomotic urethroplasty technique (28,32).

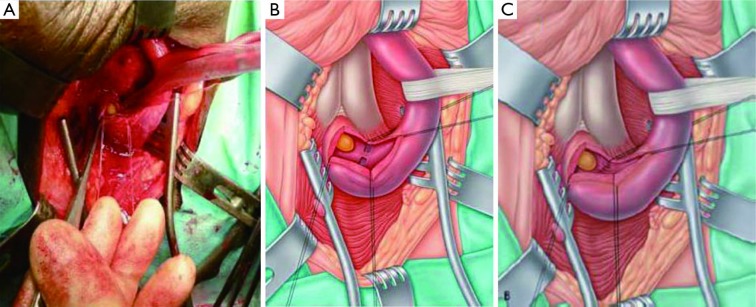

Figure 3.

Dorsal stricturotomy of a short membrane-like stricture: operative photograph (A); diagrammatic representation (B); the stricture is not excised but the epithelial defects on either side of the preserved strip are sutured (C). The dorsal stricturotomy closed transversely as in Figure 4 [reproduced with permission from (27)].

Figure 4.

(A) Diagram showing appearance following excision of epithelial and spongiofibrotic components of the stricture. Underlying spongiosum is visible; (B) the healthy mucosal edges adjacent to the excised spongiofibrosis are anastomosed in a tension-free fashion; (C) the longitudinal dorsal stricturotomy is closed in a horizontal plane [reproduced with permission from (27)].

Our experience with the non-transecting technique for bulbar urethroplasty

Our standard pre- and post-operative assessment of patients with bulbar urethral strictures consists of a clinical evaluation including a validated patient reported outcomes measure questionaire (33,34), flow rate and ascending/decending urethrography. Endoscopy does not form part of our routine assessment for urethral strictures.

A 16 F silicone foley urethral catheter is left in situ following the procedure and the perineal wound is closed in layers over a corrugated drain which is removed on the first post-operative day. A suprapubic tube is not routinely used. A pressure dressing is applied to the perineum and is also removed the day following surgery and the patient discharged home. A peri-catheter urethrogram is performed two weeks later and if this shows no leak the catheter is removed at the time. If a leak is demonstrated the catheter is kept in place for another week and a peri-catheter urethrogram repeated.

Clinical and radiological follow-up is performed at 4 months, 1 year, 2 and 5 years after the surgery.

Between January 2009 and December 2013 we have treated 67 patients with bulbar urethral strictures using one of the non-transecting techniques described. Objective follow-up (urethrogram and flow rate) and subjective follow-up (PROMS) was available for 65 (97%) of them. Mean follow-up was 13 months (range, 6.2-44.4 months). Strictures were either idiopathic (n=55; 84.6%), associated with hypospadias (n=5; 7.7%), catheter-related (n=3; 4.6%) or following TURP (n=2; 3.1%).

Six (9.2%) patients underwent a ‘Heineke-Mickulicz’-type stricturoplasty for a short membrane-like stricture. A total of 43 (66.2%) patients with proximal bulbar strictures ranging between 0.2 and 3 centimetres in length (actual stricture length measured intra-operatively) had a non-transecting anastomotic procedure (NTABU). Mean stricture length in this patient group was 1.6 centimetres. The remaining 16 (24.6%) patients with longer strictures had the narrowest segement of urethral stenosis excised in a non-transecting manner and the rest augmented dorsally using buccal mucosal graft (ANTABU). The graft was harvested from the cheek (n=14) or the undersurface of the tongue (n=2). The mean graft length was 5.2 cm (range, 3.5-9 cm).

On follow-up urethrogram there was no evidence of recurrent stricture in 63 out of the 65 patients (Figure 5) giving a radiologic success rate of 96.9%. Of the two recurrent strictures, one had undergone a simple stricturoplasty and the other a NTABU (Table 2). Both are currently being managed on a regime of regular interval urethral dilatation. Subjectively, 60 out of the 65 patients (92.3%) were satisfied or very satisfied with the overall outcome of their surgery. Their maximum flow rate improved to a mean of 32.1 mL/s. The three patients accounting for the disparity between subjective and objective outcomes (one after NTABU and two following ANTABU) remained symptomatic despite absence of recurrent stricture on fluoroscopy. Detrusor failure was confirmed on video-urodynamic assessment in all three.

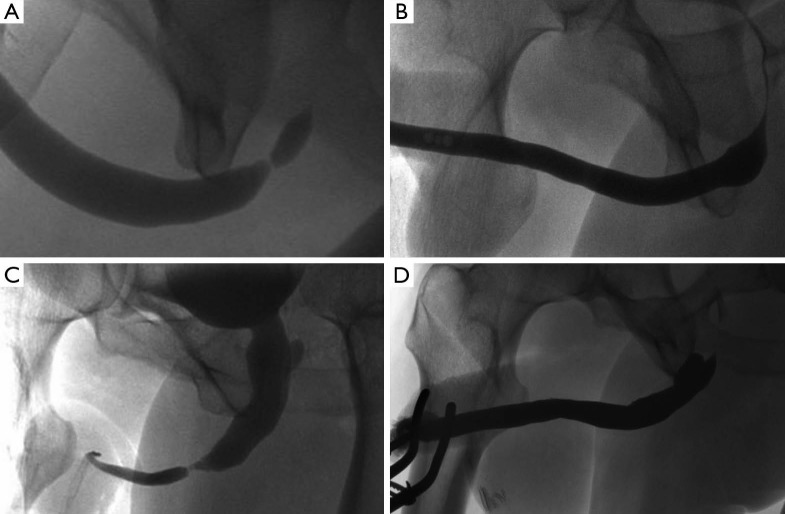

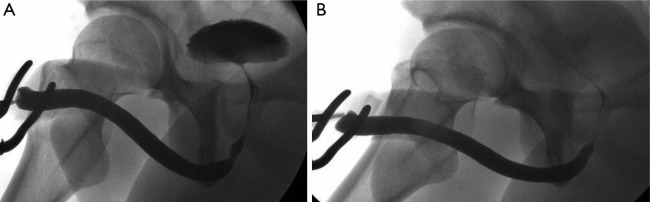

Figure 5.

Radiological appearance before and after (A,B) NTABU and (C,D) ANTABU. Even though the urethral calibre is maintained after NTABU, there is a characteristic buckled appearance of the ventral aspect of the urethra resulting from shortening of the dorsal aspect produced by the stricturoplasty.

Table 2. The subjective and objective outcomes following non-transecting bulbar urethroplasty techniques.

| Variables | Clinical assessment (patient satisfied with surgical outcome) (n, %) | Mean Qmax (mL/s) after surgery | Urethrogram (no evidence of stricture recurrence) (n, %) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stricturoplasty (n=6) | 5 (83.3) | 25.1 | 5 (83.3)† |

| NTABU* (n=43) | 41 (95.3) | 35 | 42 (97.7) |

| ANTABU** (n=16) | 14 (87.5) | 25.7 | 16 (100.0) |

†, 50% reduction in urethral calibre in one other patient but good flow and happy with outcome at 25.1 month follow-up; *, non-transecting anastomotic bulbar urethroplasty; **, augmented non-transecting anastomotic bulbar urethroplasty.

Ten of the 65 patients (15.4%) developed some degree of post-micturition dribble (PMD) following their surgery. This occurred in one, four and five patients having stricturoplasty, NTABU and ANTABU respectively (Table 3). In none of these patients was dribble causing significant bother and certainly did not have a negative impact on subjective outcome in these patients.

Table 3. Complications of non-transecting urethroplasty techniques.

| Complications | Stricturoplasty (%) | NTABU* (%) | ANTABU** (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Post-micturition dribble (10/65, 15.4%) | 1/6 (16.7%) | 4/43 (9.3) | 5/16 (31.3) |

| ED (4/62, 6.5%) | 0 | 3/42 (7.1) | 1/15 (6.7) |

| Transient ED | 0 | 2/42 (4.8) | 0 |

| Permanent ED | 0 | 1/42 (2.4) | 1/15 (6.7) |

*, non-transecting anastomotic bulbar urethroplasty; **, augmented non-transecting anastomotic bulbar urethroplasty. ED, erectile dysfunction.

A total of 4 patients out of 62 (6.5%) with previously normal erections reported some degree of sexual dysfunction post-op. This was transient in two patients undergoing NTABU, resolving within one year. In one patient each undergoing NTABU and ANTABU, erectile dysfunction (ED) persisted beyond one year and required treatment. Therefore long-term ED occurred in 2.4% of patients undergoing NTABU (Table 3).

Discussion

The anatomy of the urethra, particularly the bulbomembranous urethra, provides the basis for the non-transecting technique: the dorsal aspect of the bulbomembranous urethra is devoid of corpus spongiosum; it has a concave configuration as it curves around the point of fusion of the corporal bodies; it can stretch considerably as occurs when the bladder is displaced upwards by an expanding pelvic haematoma following a pelvic fracture. The first property means that a dorsal stricturotomy is performed in a relatively avascular plane preserving the spongiosal blood flow ventrally. The second and third provide sufficient length to allow closure of a longitudinal stricturotomy in horizonal plane without tension.

The primary aim of non-transecting techniques for bulbar urethroplasty is not to improve on the success rate of EPA for non-traumatic strictures (which is already excellent) but to try and replicate these functional outcomes while limiting surgical trauma and morbidity. We have achieved an objective success rate of 97.7% (42 of 43 patients) at a mean of 13 months in patients undergoing NTABU for short proximal bulbar strictures. A total of 95.3% (41 of 43) were subjectively improved. Of those who were not, only one had a recurrent stricture (2.3%), the other being due to detrusor failure and not any adverse event related to the surgery.

Some might argue that the follow-up in this series is short and that the results do not predict outcome in the long-term. However, most stricture recurrences after urethroplasty become clinically apparent within the first one to two years (35). Therefore we believe that a radiological stricture-free rate of 97.7% at a mean of 13 months augurs well for a satisfactory outcome in the longer term.

Long-term ED was reported in 2.4% of patients undergoing NTABU. This is significantly lower than the rate of 18-22.5% associated with EPA which is quoted in the literature (18,19). In addition, these short bulbar strictures would typically be augmented with a graft if EPA were not to be performed in order to preserve spongiosal blood flow. NTABU provides an alternative treatment option for these patients, avoiding donor site morbidity associated with harvesting a buccal graft (36,37).

Avoiding the use of a graft also reduces the incidence of PMD which is typically associated with augmentation bulbar urethroplasty. In a series of 71 patients, all patients having patch urethroplasty (dorsal and ventral) developed some degree of PMD which was troublesome in 21% of them (31). Any degree of PMD is considered to be unacceptable in some cultures. Only 4 out of 43 patients (9.3%) undergoing NTABU in our present series developed PMD and in all cases this was small-volume and non-bothersome.

Besides NTABU, we have also described the ‘Heineke-Mickulicz’-type stricturoplasty. Some would query the rationale behind this technique in which the stricture is not excised, possibly increasing the risk of stricture recurrence. We would argue that this technique should be strictly limited to those patients with short membrane-like strictures in whom there is very little to excise. Stricture excision in these cases may result in as much fibrosis as is excised, while performing a simple stricturoplasty achieves just as adequate a urethral calibre without additional surgical trauma (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Radiological appearance (A) before and (B) after stricturoplasty for short, sharp, proximal bulbar strictures.

As mentioned earlier, the type of bulbar urethroplasty performed will be influenced by stricture length and the degree of spongiofibrosis. This must be carefully assessed intra-operatively since pre-operative fluoroscopic assessment can markedly underestimate the length of a stricture if a perfectly lateral view is not obtained. For this reason all our patients with non-traumatic bulbar strictures being consented for bulbar urethroplasty are aware that a definitive decision on the type of procedure they will undergo is made after dorsal stricturotomy and evaluation of the stricture. If the stricture is longer than anticipated we will simply convert from a NTABU to a dorsal augmentation urethroplasty (which is also non-transecting).

The non-transecting technique has resulted in an important change in our approach to bulbar urethroplasty over the past few years. All non-traumatic bulbar strictures are now managed by NTABU, ANTABU or dorsal patch bulbar urethroplasty with transection of the urethra performed only for full thickness spongiofibrosis strictures associated with perineal trauma.

Conclusions

Stricture aetiology is the main determinant of whether transection of the bulbar urethra is necessary or not. It is inevitable in trauma when the fibrosis must be completely excised and healthy urethral edges anastomosed to secure the most durable result. It is however certainly not necessary in short non-traumatic proximal bulbar strictures. A dorsal approach to these strictures coupled with a non-transecting technique prevents disruption of the integrity of ventral spongiosal blood flow and there are practical and theoretical reasons for doing so. Functional outcomes are equivalent to transection and end-to-end anastomosis with less surgical trauma. Minimising surgical trauma and preservation of blood supply are key principles for any surgical intervention, so why should bulbar urethroplasty be any different?

Key learning points:

Surgical treatment of bulbar strictures is influenced by aetiology, length, location and degree of spongiofibrosis;

Traumatic bulbar strictures are associated with severe spongiofibrosis; in most non-traumatic strictures spongiofibrosis is only superficial with healthy residual underlying spongiosum which should be preserved;

The anatomy and blood supply of the urethra allows both transecting and non-transecting techniques for the treatment of bulbar strictures;

Non-transection has the advantage of preserving urethral vasculature which may become important when blood supply is compromised for a variety of reasons; also associated with a lesser impact on sexual function;

A dorsal stricturotomy approach allows to adjust operative technique to intra-operative findings (stricture length, location) preserving ventral spongiosal blood flow;

Early results seem to show comparably high success rates for both transecting and non-transecting approaches.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Barbagli G, Sansalone S, Romano G, et al. Bulbar urethroplasty: transecting vs. nontransecting techniques. Curr Opin Urol 2012;22:474-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mundy AR, Andrich DE. Urethral strictures. BJU Int 2011;107:6-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steenkamp JW, Heyns CF, de Kock ML. Internal urethrotomy versus dilation as treatment for male urethral strictures: a prospective, randomized comparison. J Urol 1997;157:98-101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Greenwell TJ, Castle C, Andrich DE, et al. Repeat urethrotomy and dilation for the treatment of urethral stricture are neither clinically effective nor cost-effective. J Urol 2004;172:275-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Naudé AM, Heyns CF. What is the place of internal urethrotomy in the treatment of urethral stricture disease? Nat Clin Pract Urol 2005;2:538-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Netto NR, Jr, Martucci RC, Goncalves ES, et al. Congenital stricture of male urethra. Int Urol Nephrol 1976;8:55-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sugimoto M, Kakehi Y, Yamashita M, et al. Ten cases of congenital urethral stricture in childhood with enuresis. Int J Urol 2005;12:558-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mundy AR. Anastomotic urethroplasty. BJU Int 2005;96:921-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morey AF, Watkin N, Shenfeld O, et al. SIU/ICUD Consultation on Urethral Strictures: Anterior urethra--primary anastomosis. Urology 2014;83:S23-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guralnick ML, Webster GD. The augmented anastomotic urethroplasty: indications and outcome in 29 patients. J Urol 2001;165:1496-501. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abouassaly R, Angermeier KW. Augmented anastomotic urethroplasty. J Urol 2007;177:2211-5; discussion 2215-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barbagli G, Guazzoni G, Lazzeri M. One-stage bulbar urethroplasty: retrospective analysis of the results in 375 patients. Eur Urol 2008;53:828-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Terlecki RP, Steele MC, Valadez C, et al. Grafts are unnecessary for proximal bulbar reconstruction. J Urol 2010;184:2395-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barbagli G, Lazzeri M. Reconstructive urethral surgery to be addressed at 2009 GURS meeting. AUANews 2009;14:14. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mundy AR, Andrich DE. Non-transecting bulbar urethroplasty. In: Brandes SB, Morey AF. eds. Advanced Male Urethral and Genital Reconstructive Surgery, New York: Humana Press, 2014:531-40. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cavalcanti AG, Costa WS, Baskin LS, et al. A morphometric analysis of bulbar urethral strictures. BJU Int 2007;100:397-402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jordan GH, Eltahawy EA, Virasoro R. The technique of vessel sparing excision and primary anastomosis for proximal bulbous urethral reconstruction. J Urol 2007;177:1799-802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Al-Qudah HS, Santucci RA. Buccal mucosal onlay urethroplasty versus anastomotic urethroplasty (AU) for short urethral strictures: which is better? J Urol 2006;175:103. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barbagli G, De Angelis M, Romano G, et al. Long-term followup of bulbar end-to-end anastomosis: a retrospective analysis of 153 patients in a single center experience. J Urol 2007;178:2470-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Erickson BA, Granieri MA, Meeks JJ, et al. Prospective analysis of erectile dysfunction after anterior urethroplasty: incidence and recovery of function. J Urol 2010;183:657-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eltahawy EA, Virasoro R, Schlossberg SM, et al. Long-term followup for excision and primary anastomosis for anterior urethral strictures. J Urol 2007;177:1803-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Santucci RA, Mario LA, McAninch JW. Anastomotic urethroplasty for bulbar urethral stricture: analysis of 168 patients. J Urol 2002;167:1715-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mangera A, Patterson JM, Chapple CR. A systematic review of graft augmentation urethroplasty techniques for the treatment of anterior urethral strictures. Eur Urol 2011;59:797-814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Andrich DE, Dunglison N, Greenwell TJ, et al. The long-term results of urethroplasty. J Urol 2003;170:90-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Palminteri E, Franco G, Berdondini E, et al. Anterior urethroplasty and effects on sexual life: which is the best technique? Minerva Urol Nefrol 2010;62:371-6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gur U, Jordan GH. Vessel-sparing excision and primary anastomosis (for proximal bulbar urethral strictures). BJU Int 2008;101:1183-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Andrich DE, Mundy AR. Non-transecting anastomotic bulbar urethroplasty: a preliminary report. BJU Int 2012;109:1090-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Welk BK, Kodama RT. The augmented nontransected anastomotic urethroplasty for the treatment of bulbar urethral strictures. Urology 2012;79:917-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Andrich DE, Mundy AR. Complications of 'Social' Lithotomy. BJU Int 2010;16 40-1. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pocivavsek L, Efrati E, Lee KY, et al. Three-dimensional geometry of the Heineke-Mikulicz strictureplasty. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2013;19:704-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Andrich DE, Leach CJ, Mundy AR. The Barbagli procedure gives the best results for patch urethroplasty of the bulbar urethra. BJU Int 2001;88:385-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gingu C, Dick A, Patrascoiu S, et al. Nontransecting augmented roof anastomosis: The technique of choice for long bulbar urethral strictures with limited spongiofibrosis. Eur Urol Suppl 2014;13:e77. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jackson MJ, Sciberras J, Mangera A, et al. Defining a patient-reported outcome measure for urethral stricture surgery. Eur Urol 2011;60:60-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jackson MJ, Chaudhury I, Mangera A, et al. A prospective patient-centred evaluation of urethroplasty for anterior urethral stricture using a validated patient-reported outcome measure. Eur Urol 2013;64:777-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Meeks JJ, Erickson BA, Granieri MA, et al. Stricture recurrence after urethroplasty: a systematic review. J Urol 2009;182:1266-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Barbagli G, Vallasciani S, Romano G, et al. Morbidity of oral mucosa graft harvesting from a single cheek. Eur Urol 2010;58:33-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wood DN, Allen SE, Andrich DE, et al. The morbidity of buccal mucosal graft harvest for urethroplasty and the effect of nonclosure of the graft harvest site on postoperative pain. J Urol 2004;172:580-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]