Abstract

Cardif, also known as IPS-1, VISA and, MAVS, is an intracellular adaptor protein that functions downstream of the RIG-I family of pattern recognition receptors. Cardif is required for the production of type I-IFNs and other inflammatory cytokines after RIG-I like receptors recognize intracellular antigenic RNA. Studies have recently shown that Cardif may have other roles in the immune system in addition to its role in viral immunity. In this study, we find that the absence of Cardif alters normal natural killer cell development and maturation. Cardif−/− mice have a 35% loss of mature CD27−CD11b+ NK cells in the periphery. Additionally, Cardif−/− NK cells have altered surface marker expression, lower cytoxicity, decreased intracellular STAT1 levels, increased apoptosis and decreased proliferation compared to wild-type NK cells. Mixed chimeric mice revealed that the defective maturation and increased apoptotic rate of peripheral Cardif−/− NK cells is cell-intrinsic. However, Cardif−/− mice showed enhanced control of mouse cytomegalovirus (MCMV, a DNA β-herpesvirus) by NK cells, commensurate with increased activation and IFNγ production by these immature NK cell subsets. These results indicate that the skewed differentiation and altered STAT expression of Cardif−/− NK cells can result in their hyper-responsiveness in some settings, and support recent findings that Cardif-dependent signaling can regulate aspects of immune cell development and/or function distinct from its well characterized role in mediating cell-intrinsic defense to RNA viruses.

Introduction

Pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) recognize pathogen associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) (1, 2). Retinoic acid inducible gene-1 (RIG-I)-like receptors (RLRs) are a subset of PRRs that recognize intracellular viral nucleic acids and induce the production of type-I IFNs and NFκB regulated genes (3). Two members of the RLR family, RIG-I and MDA5, have caspase recruitment and activation domains (CARDs) that allow for downstream signaling after activation. The adaptor protein that interacts with RIG-I and MDA5 and allows downstream signaling was discovered by four different groups and is thus known by four names: Cardif (CARD adaptor inducing interferon-β), MAVS (mitochondrial antiviral signaling), IPS-1 (IFN-β promoter stimulator-1), and VISA (virus-induced signaling adaptor) (4–7). We will refer to this protein as Cardif.

RIG-I and MDA5 initiate signaling through CARD-CARD interactions with Cardif, which is a ubiquitously expressed protein that is located on the outer mitochondrial membrane of both immune and non-immune cells (3, 8). The mitochondrial localization of Cardif is essential to its signaling function. Once Cardif has been engaged by RIG-I or MDA5, it aggregates with other Cardif molecules. This aggregation is essential to propagation of downstream signals (9). Cardif interacts with cytoplasmic adaptor molecules TRAF3, TRAF2, and TRAF6 to activate transcription factors NFκB, IRF3, and IRF7 to induce expression of type I IFN genes and IFN-induced genes (3, 10).

Cardif is vital for signaling in response to viral pathogenic nucleic acids sensed by MDA5 and RIG-1. However, there have been reports that suggest that both RIG-I and Cardif may play roles in immune regulation that are separate from their roles in viral defense (11–15). Wang et al. report that RIG-I−/− mice develop colitis and are more susceptible to dextran sulfate-induced colitis (12). Xu et al. report that Cardif−/− B cells have a cell-intrinsic defect in CD23 and TLR7 expression (13). Additionally, Cardif−/− mice develop more severe disease in the mouse model of multiple sclerosis, experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) (16). Cardif is also required for the optimal activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome (14). RIG-I activity under the control of IRF1 has been implicated in the progression of atherosclerosis. Wang et al. propose that 25-hydroxycholesterol induces IL-8 production in macrophages by inducing IRF1 and subsequent RIG-I expression and activation (15). These reports as well as others, suggest that Cardif is active even in the absence of pathogenic viral RNA.

Natural killer (NK) cells are innate cytotoxic lymphocytes that target virally infected, stressed or cancerous cells (17). NK cells primarily develop in the bone marrow although some peripheral organs such as the liver can house and develop NK cells (18–20). Mature NK (mNK) cells are the primary NK cells found in peripheral organs such as the spleen, liver, and lymph nodes where they undergo additional maturation (21). CD49b acquisition is the earliest stage of NK maturity. The acquisition of CD11b, CD43, and KLRG1 occur after CD49b, and identify more advanced stages of NK maturation. Surface markers CD27 and CD11b can be used to further delineate stages of maturation within immature NK and CD49b+ NK (mNK) cells (22–24). Maturation using these markers is divided into four stages that progress in the following order: CD27−CD11b− (Stage 1) → CD27+CD11b− (Stage 2) → CD27+CD11b+ (Stage 3) → CD27−CD11b+ (Stage 4). Very few CD27−CD11b− NK cells are found in the peripheral organs and the majority of CD27−CD11b− NK cells do not express CD49b. CD27+CD11b− NK cells are highly proliferative and have the ability to degranulate but are not as cytotoxic as CD27+CD11b+ or CD27−CD11b+ NK cells. CD27+CD11b+ NK cells are highly responsive to cytokine and DC stimulation in vitro compared to CD27−CD11b+ NK cells (22). CD27−CD11b+ NK cells are terminally differentiated, long-lived, and express the inhibitory NK receptor KLRG1 on their surface (25). CD27+CD11b+ NK cells are most prevalent in bone marrow and lymph nodes while CD27−CD11b+ NK cells are the predominant stage found in spleen, liver, blood, and lung.

NK cell numbers, maturation, and function are diminished in the absence of type I IFN signaling. IFNAR−/− mice that lack the ability to respond to type I IFN have fewer NK cells and are unable to control the growth of tumor cells that are normally susceptible to NK killing (26–29). IFNAR-deficient NK cells are also unable to kill some NK target cells in vitro. It has been suggested that consistent and low levels of type I IFN are required to maintain NK cell numbers and functionality in vivo as well (30). Constitutive type I IFN signaling maintains STAT1 levels in NK cells. High STAT1 levels are required to maintain NK cytotoxicity while STAT4 leads to IFNγ production (26, 31, 32). It has been suggested that many of the effects of type I IFN deficiency in NK cells can be attributed to the reduction of intracellular STAT1 levels.

Considering the above studies and observations, we sought to understand how the absence of Cardif affects the development, maturation, and function of NK cells. In this study, we found that Cardif expression is required for maintaining optimal NK cell numbers in the periphery and for full NK cell maturation. As such, we found a marked reduction in the number of CD49b+ and CD27−CD11b+ NK cells with a concomitant increase in CD27+CD11b− and CD27+CD11b+ NK cells in the periphery of mice lacking Cardif. These NK cells had decreased cytotoxicity although they produced comparable amounts of IFNγ after stimulation in vitro. Mixed bone marrow chimeras revealed that the maturation of peripheral Cardif−/− NK cells is cell-intrinsic. Similar to NK cells from IFNAR−/− mice, Cardif−/− NK cells showed decreased proliferation and decreased STAT1 activation. Intriguingly, despite their altered differentiation and effector function in these settings, in response to MCMV infection NK cells from Cardif−/− mkice showed heightened IFNg production and enhanced control of this dsDNA b-herpesvirus. Together, our results indicate that Cardif imposes intrinsic regulation of NK cell subset maintenance and function in diverse inflammatory settings.

Materials and Methods

Mice

Cardif−/− mice were a kind gift from the Shresta laboratory at La Jolla Institute for Allergy and Immunology. Cardif−/− mice were generated as described in Michallet, et al., and are on a C57BL/6 background (33). C57BL/6 mice purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (000664) or wild-type littermates were used as controls in experiments. Male and female mice were used at 6–12 weeks of age. All experiments adhered to the guidelines outlined by the La Jolla Institute for Allergy and Immunology Animal Care and Use Committee, according to criteria outlined in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals from the National Institutes of Health. Mice were euthanized by CO2 inhalation.

Flow cytometry

Spleen and liver were harvested and pushed through a 40-μm strainer. Liver was perfused with PBS prior to collection and placed in RPMI supplemented with 10μm HEPES and 10% FBS. In addition, lymphocytes were separated from hepatocytes via density centrifugation. Red blood cells were lysed with RBC lysis buffer according to the manufacturer’s protocol (BioLegend). Cells were resuspended in FACS buffer (1%BSA and 0.1% sodium azide in PBS) and 1–4 × 106 cells were incubated in 100μl with anti-CD16/CD32 Ab (2.4G2) for 30 min on ice to block FCγRII/III receptor binding. Samples were then incubated with a mixture of fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies (BioLegend, eBiosciences, BD Biosciences) for 30 min on ice in the dark. LIVE/DEAD Fixable Dead Cell Stain (Invitrogen) was used to determine cell viability. Intracellular staining of antibodies was performed after cells were fixed and permeabilized using 0.55% paraformaldehyde and Permeabilization Buffer (BD Biosciences). Samples were analyzed for cellular fluorescence on an LSR II (BD Biosciences) and data were analyzed with FlowJo software (Treestar). A complete flow cytometry gating strategy for peripheral NK cells is shown in Supplemental Figure 1.

Ex vivo stimulation

Spleen was harvested and pushed through a 40-μm strainer. Red blood cells were lysed with RBC lysis buffer according to the manufacturer’s protocol (BioLegend). Splenocytes were cultured in 96-well plates for 4–5 hours in the presence of either PMA (50ng/mL) and ionomycin (1μg/mL), or IL-12 (20ng/mL) and IL-18 (20ng/mL). When measuring degranulation, FITC-conjugated CD107a antibody (0.05ug/mL) was added to the stimulation media. After stimulation, splenocytes were washed with PBS and then prepared for flow cytometry analysis as described above.

In vitro culture

NK cells were enriched using EasySep™ Mouse NK Cell Enrichment kit (Stem Cell Technologies). Spleens from 3 or more mice were pooled together. Purity of NK cells was ~80–85% as reported by supplier. Murine cytokines were used in the following concentrations: IL-15 (50ng/mL) (PeproTech), IL-18 (50ng/mL) (PeproTech), IFN-β (10U/mL) (Millipore). There were triplicates of each condition. Cells were stimulated with PMA (50ng/mL) and ionomycin (1μg/mL) for 4 hours. After 4 hours, cells were harvested and processed for FACS analysis. For type I IFN rescue experiments, NK cells were cultured in the presence of IL-15 only or IL-15 with IFN-β for 5 days at a concentration of 5e6 cells/ml in a 96 well round bottom plate. IL-15 was vital for the survival of NK cells in culture. After 5 days of cytokine treatment, NK cells were stimulated with PMA and ionomycin at the aforementioned concentrations and analyzed by flow cytometry.

Cytotoxicity Assay

Enriched NK cells were cultured at various ratios together with calcein labeled-YAC-1 cells for 4 hours. YAC-1 cells were labeled with 0.5uM calcein. Specific lysis was determined by measuring percent specific release of calcein using the following formula: Percent specific release = (experimental release − spontaneous release)/(maximum release − spontaneous release) × 100.

Bone Marrow transplantation

Bone marrow transplantation studies were performed as previously described (34). CD54.1/.2 mice were irradiated with two doses of 550 rads each, 4 hours apart. Bone marrow cells were isolated from CD45.1 and Cardif−/− mice and processed under sterile conditions. A single-cell suspension in PBS was obtained with a 1:1 ratio of CD45.1 and Cardif−/− bone marrow cells. Approximately 5e6 cells were retro-orbitally injected into recipient CD54.1/.2 mice in a volume of 200μl. Mice received autoclaved water treated with antibiotics (trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole), one week before and continued until one week after injection. Mice were euthanized for experiments 8–10 weeks after injection.

Apoptosis and proliferation analysis

Annexin V (Invitrogen) and propidium iodide (Invitrogen) were used to identify apoptotic and dead cells respectively. Cells were stained according to the protocol provided by the manufacturer. FITC conjugated Caspase-3 (BD Biosciences) was also used to identify apoptotic cells. Cells were stained for intracellular caspase-3 according to the manufacturer’s protocol. For proliferation, Ki-67 (eBioscience) was used to identify proliferating cells ex vivo. Splenocytes were stained for intracellular Ki-67 using the Foxp3/Transcription factor staining buffer set (eBioscience), and cells were stained according to the protocol provided by the manufacturer.

Western blot analysis

NK cells were isolated using EasySep™ Mouse CD49b positive selection kit (Stemcell technologies). Spleens from 7 or more mice were pooled together. Purity of NK cells was ~90% as reported by supplier. Isolated NK cells were then divided and either left untreated or treated with 100U/mL IFN-β (Millipore) for 15 min at 37°C. Cells were then lysed for protein collection using RIPA Buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM NaVO4, 1 mM NaF, 0.5% NP40, 0.1% Brij35, 0.1% deoxycholic acid). Total was quantified using BCA Protein Assay Reagent (Thermo Scientific). Afterwards, 30μg of each protein sample was loaded into SDS-PAGE. The following antibodies were used at specified concentrations for immunoblots: STAT1 (1:1000; Cell Signaling #9172), pSTAT1 (Tyr701) (1:1000; Cell Signaling #9171), STAT4 (1:1000; Cell Signaling #2653), pSTAT4 (1:1000; Cell Signaling #5267), and β-Actin (1:2000; Cell Signaling #9774). Western blots were quantified using ImageJ software (NIH).

MCMV Infection

MCMV WT and Δm157 salivary gland stocks were derived from the BAC-cloned MCMV K181 strain (kind gift from Alec Redwood) after in vivo passage of MEF-derived virus twice in 3 week old Balb/c mice for 12 days, as previously described (35). Cardif−/− and WT mice were infected intra-peritoneally (i.p.) with 1 × 105 PFU, and viral replication in organs was measured by plaque assay in NIH 3T3 cells as described (36). NK cells were depleted by injecting 200ug of anti-NK1.1 antibody (clone PK136) in 200ul of PBS 24h prior to infection.

Statistical analysis

All data are presented with mean ± SEM as determined by Prism software (GraphPad). Unpaired t-tests were used to compare WT and Cardif−/− samples. P values of 0.05 or less were considered significant for all experiments.

Results

NK maturation is impaired in Cardif−/− mice

Cardif is reportedly active in the absence of a viral infection and is a potent inducer of type I IFN (3, 13, 16). Studies have shown that type I IFN regulates NK cell maturation and function (27, 30). With this information, we hypothesized that Cardif may influence NK cell maturation and function. To test this hypothesis, we characterized NK cells in the bone marrow and in the periphery of wild-type (WT) and Cardif−/− mice. We found that, compared to WT mice, Cardif−/− mice have fewer numbers of CD19−CD3−NK1.1+ NK cells in spleen but not in bone marrow (Fig. 1A).

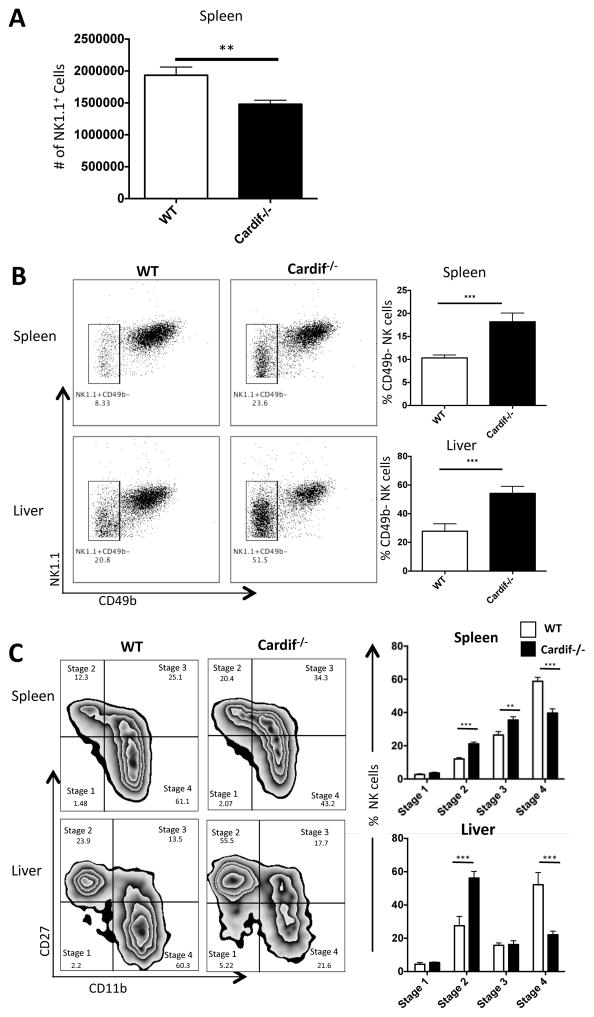

Figure 1.

Cardif is required for optimal NK cell numbers in the periphery and for the terminal differentiation of NK cells. (A) The absolute number of NK1.1+CD3−CD19− cells was determined in the spleen. (B) Representative plots (left and middle panels) and bar graphs (right panels) show the percentage of CD49b− NK cells (NK1.1+CD3−CD19−) in the spleen (upper panels) and liver (lower panels). (C) Representative plots and bar graphs plots (left and middle panels) and bar graphs (right panels) show the distribution of mNK (NK1.1+CD3−CD19− CD49b+) cells based on CD27 and CD11b expression in the spleen (upper panels) and liver (lower panels). Stages 1–4 are as follows: stage 1(CD27−CD11b−), stage 2 (CD27+CD11b−), stage 3 (CD27+CD11b−), and stage 4 (CD27−CD11b+). Experiments were repeated at least three times. For all, n=3–5 mice/group/experiment. Data are means ± SEM. **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

The acquisition of CD49b marks the developmental step from immature NK (iNK) to mature NK (mNK) cells (21, 37). We found that the frequency of CD49b− (immature) NK cells in Cardif−/− spleen and liver is significantly higher than in WT NK cells (Fig. 1B). This 2-fold increase of CD49b− NK cells in the spleens and livers of Cardif−/− mice suggests a delay in mNK development and maintenance in the periphery.

In addition to a reduction in mature NK cells (NK1.1+CD3−CD19− CD49b+), we observed a significant reduction in terminally differentiated CD27−CD11b+ NK cells in the spleen and liver of Cardif−/− mice (Fig. 1C). This reduction of CD27−CD11b+ NK cells is accompanied by a concomitant increase in frequencies of CD27+CD11b− and CD27+CD11b+ NK cells. Cardif−/− mice have a 35–40% loss of terminally differentiated mature CD27−CD11b+ NK cells with a concomitant increase in less mature (CD27+CD11b− and CD27+CD11b+) NK cells in the spleen. Additionally, there is a >50% decrease in terminally differentiated CD27−CD11b+ NK cells and a 50% increase in CD27+CD11b+ NK cells in liver of Cardif−/− mice (Fig. 1C). NK cells in the blood and lymph nodes of Cardif−/− mice displayed similar alterations in NK maturation (data not shown). However, we found no differences in NK maturation in the bone marrow (Supp. Fig. 2). Taken together, these data suggest that Cardif is important for NK maturation but does not impair NK development in bone marrow.

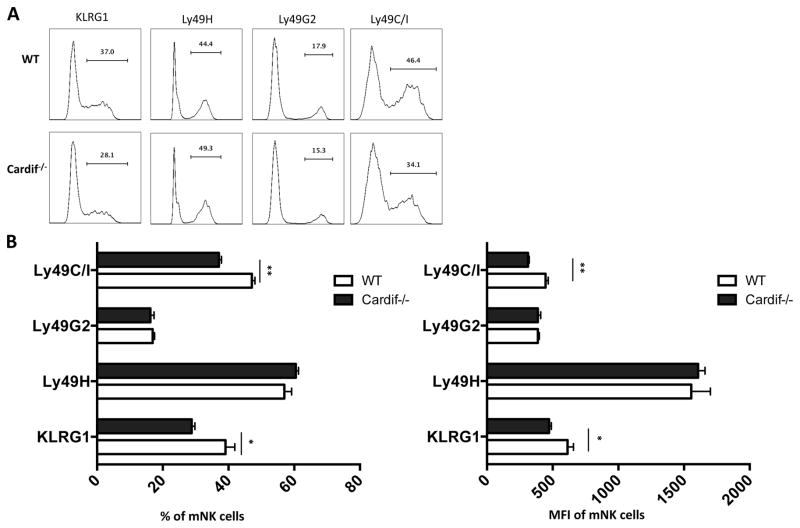

Inhibitory receptor expression is reduced in Cardif−/− mice

We next wanted to examine homeostatic NK function in the absence of Cardif signaling. Ly49 receptor expression on NK cells is required for NK cell “licensing”, the process that allows NK cells to become active cytolytic cells following their encounter with self MHC-1 expressing cells (38–40). The expression of the inhibitory receptors such as Ly49C/I and KLRG1 on NK cells is associated with NK cell maturity (23, 25). We investigated the expression of KLRG1 and select Ly49 receptors in Cardif−/− mice. We found that significantly fewer Cardif−/− mNK (NK1.1+CD3−CD19−CD49b+) cells express KLRG1 (Fig. 2A, 2B) (21). Moreover, there is a decrease in the surface expression of KLRG1 on Cardif−/− mNK cells (Fig. 2B). We found that WT and Cardif−/− mNK cells express similar amounts of the activating Ly49H receptor and the inhibitory Ly49G2 receptor (Fig. 2A, 2B). However, the number of Ly49C/I+ mNK cells is markedly decreased in Cardif−/− mice. Likewise, the surface expression of Ly49C/I on Cardif−/− mNK cells is significantly lower than WT mNK cells. The decrease in the frequency and cellular expression of KLRG1 and Ly49C/I which are associated with NK cell activation and maturation, suggest that Cardif is involved in late mNK cell maturation (18, 41).

Figure 2.

Cardif−/− NK cells are less mature. (A) Representative histograms show the percentages of KLRG1+ cells, and cells expressing select activating and inhibitory Ly49 receptors in WT and Cardif−/− mNK populations (NK1.1+CD3−CD19− CD49b+). (B) Bar graphs depict the percentage (left panel) and amount of expression (right panel) of NK maturation markers and Ly49 receptors. Amount of expression was determined by flow cytometric analysis of mean fluorescence intensity (MFI). Experiments were repeated twice. For all, n=3 mice/group/experiment. Data are means ± SEM. *p< 0.05, **p<0.01.

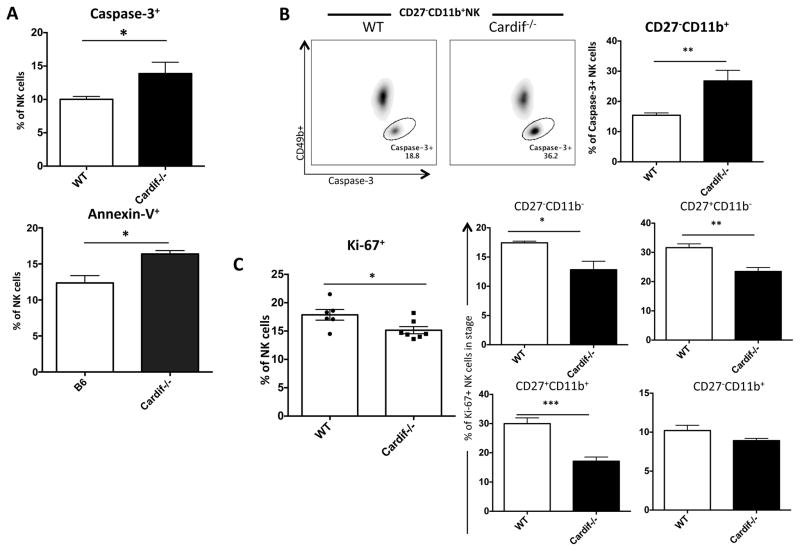

Cardif−/− NK cells are more apoptotic and less proliferative

In order to identify mechanistically why there are fewer mature NK cells in Cardif−/− mice, we investigated the survival and proliferation of NK cells in Cardif−/− mice. We found that more Cardif−/− NK cells were caspase-3+, suggesting that they were more apoptotic (Fig. 3A). We confirmed the increase in apoptosis using Annexin V, as we found more Annexin V+ NK cells in Cardif−/− mice, (Fig. 3A). The greatest increase in apoptotic mNK cells was observed in terminally differentiated CD27−CD11b+ NK cells, where 2-fold more CD27−CD11b+ Cardif−/− NK cells were apoptotic as noted by caspase-3 expression (Fig. 3B). This increase of caspase-3+ CD27−CD11b+ NK cells in Cardif−/− mice accounts for the increase in frequencies of total caspase-3+ NK cells. These data suggest that Cardif−/− NK cells, particularly, terminally differentiated CD27−CD11b+ NK cells, are more apoptotic in the absence of tonic Cardif signaling. We used Ki-67 to identify proliferating NK cells in Cardif−/− and WT mice. We found a ~15% decrease in proliferation of total splenic Cardif−/− NK cells compared to WT NK cells (Fig. 3C). However, upon further analysis, we found that CD27+CD11b− and CD27+CD11b+ Cardif−/− NK cells have a ~25% and ~30% reduction in proliferation, respectively. These two stages of NK cells are known to mature into CD27−CD11b+ NK cells (22, 23). Thus, in the absence of Cardif, early-stage NK cells proliferate less while terminally differentiated CD27−CD11b+ NK cells are prone to apoptosis. These data support our findings that Cardif−/− mice have fewer total NK cells and increased numbers of early-stage NK cells.

Figure 3.

Cardif−/− NK cells are more apoptotic and less proliferative. (A) Bar graphs show the percentage of Caspase-3+ (upper panel) and Annexin-V+ (lower panels) NK cells (NK1.1+CD3−CD19−) from WT and Cardif−/− mice. (B) Representative plots and bar graph of the percentage of WT and Cardif−/− caspase-3+ CD27−CD11b+ NK cells. (C) Bar graphs depict the percentage of Ki-67+ total NK cells (left panel), as well as stage 1–4 NK cells (middle and right panels). Experiments were repeated twice. For all, n=4–5 mice/group/experiment. Data are means ± SEM. *p< 0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

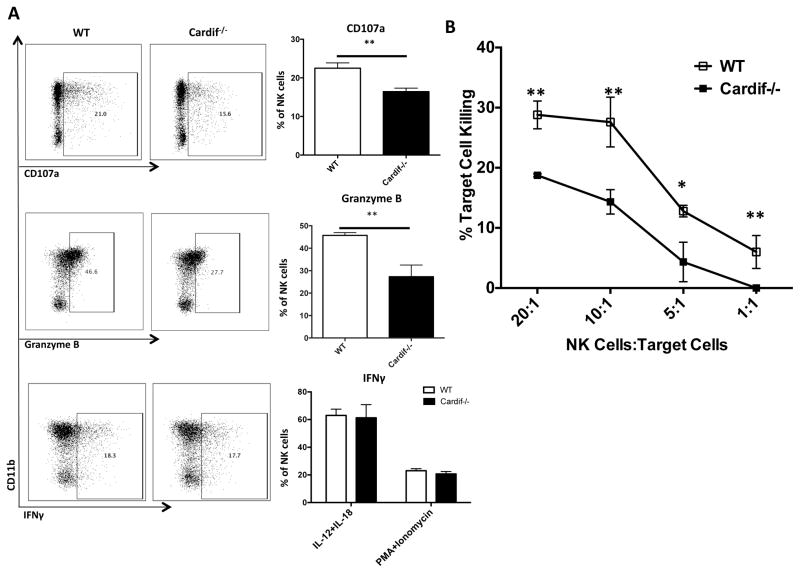

Cardif deficiency alters NK cell function

Since we found that NK cells in Cardif−/− mice are less mature and fewer are Ly49C/I+, we hypothesized that Cardif-deficient NK cells may not function as well as WT NK cells. Fernandez, et al., has previously shown that unlicensed Ly49C/I− NK cells are less cytotoxic than Ly49C/I+ NK cells (42). We stimulated WT and NK Cardif−/− NK cells with either IL-12 and IL-18, or PMA (phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate) and ionomycin ex vivo. We found that granzyme B and CD107a, a marker of degranulation, were significantly reduced in Cardif−/− NK cells compared to WT NK cells, suggesting that Cardif−/− NK cells are likely impaired in their ability to kill target cells (Fig. 4A). The production of IFNγ however was comparable between NK cells from both WT and Cardif−/− mice. Next, we tested the ability of Cardif−/− NK cells to directly kill target cells in vitro. YAC-1 cells served as target cells in the assay. Cardif−/− NK cells had ~20–25% less cytotoxic activity than WT NK cells when cultured with target B cells (Fig. 4B). These data indicate that Cardif plays an important role in manipulating the functions of NK cells.

Figure 4.

Cardif−/− NK cells are less cytotoxic than WT mNK cells. (A) Representative plots and bar graphs show the percentage of CD107a+ (upper panels), granzyme B+ (middle panels), and IFNγ+ (lower panels) mNK (NK1.1+CD3−CD19− CD49b+) cells in WT and Cardif−/− samples. (B) Representative line graph depicting the cytotoxic activity of WT and Cardif−/− NK cells against target YAC-1 cells at various ratios. Ratios are NK cells : Target cells. Experiments were repeated at least twice. For all, n=3–5 mice/group/experiment. Data are means ± SEM. *p< 0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

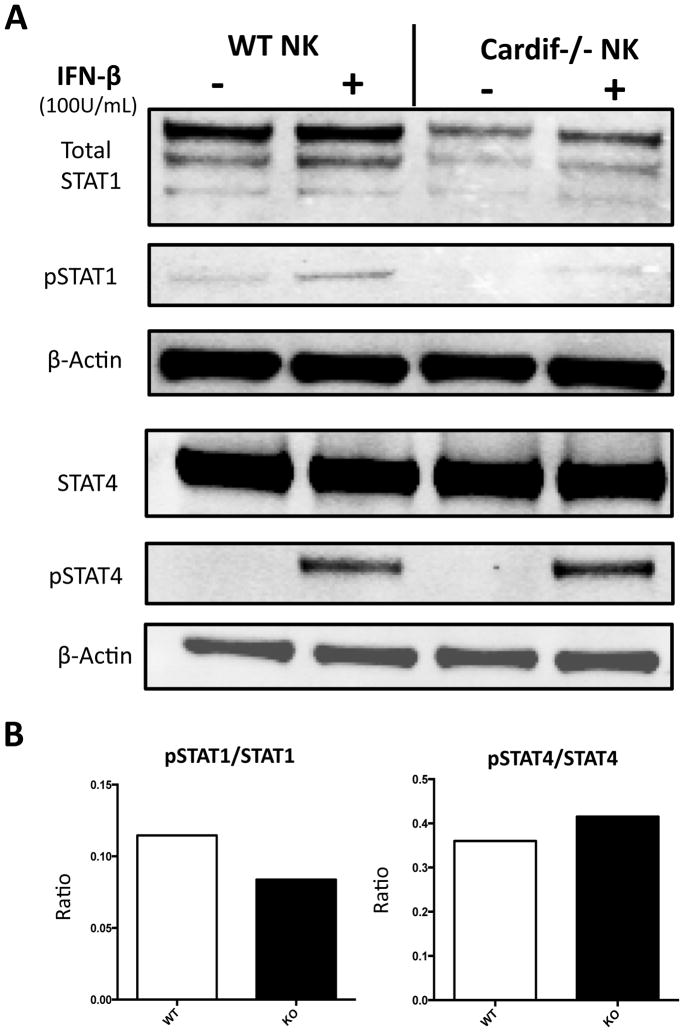

STAT1 protein is reduced in Cardif−/− NK cells

Reports have shown that the maintenance of STAT1 levels in NK cells is important for NK cell cytotoxicity upon activation, while the levels of STAT4 are important for IFNγ production (31). In earlier experiments, we found that Cardif−/− NK cells are less cytotoxic than WT NK cells while IFNγ production was the same (Fig. 4A and Fig. 4B). With these observations, we decided to measure STAT1 and STAT4 phosphorylation in NK cells and found that there were dramatic reductions in both the phosphorylation and the levels of STAT1 protein in Cardif−/− NK cells (Fig. 5A). STAT4 protein and phosphorylation seemed similar between Cardif−/− and WT NK cells but we found that the pSTAT4/STAT4 ratio was higher in Cardif−/− NK cells (Fig. 5B). Based on a known role for STAT1 in regulating NK cytolytic functions, these data indicate that the reduced cytolytic function of Cardif−/− NK cells is most likely due to the low intracellular amount of STAT1 and phosphorylated. The effects of an increase in the pSTAT4/STAT4 ratio in Cardif−/− NK cells was most likely masked due to the already high amounts of STAT4 present in WT NK cells.

Figure 5.

Cardif−/− mNK cells have decreased levels of STAT1 and phosphorylated STAT1. (A) Western blot shows the amount of total STAT1 (top panel), pSTAT1 (2nd panel), STAT4 (4th panel), and pSTAT4 (bottom panel) protein in WT (left panels) and Cardif−/− (right panels) mNK cells. Cells were treated with PBS or 100U/ml of IFN-β. Afterwards, 30ug of protein from cell lysates were loaded per well. β-Actin was used to normalize protein data. (B) pSTAT1/STAT1 and pSTAT4/STAT4 ratios derived western blot quantification. Experiments were repeated twice. For all, n=4 mice/group/experiment. Data are means ± SEM. *p< 0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

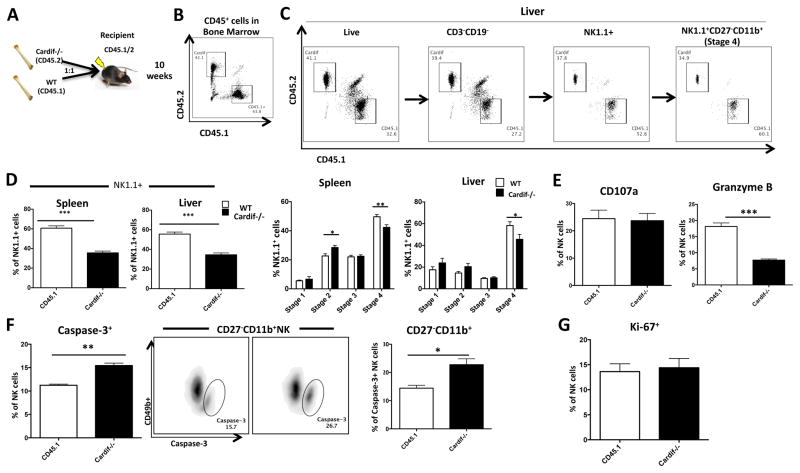

Impaired NK cell phenotype in Cardif−/− mice is cell-intrinsic

To determine whether the impact of Cardif on NK cell maturation is cell-intrinsic, we used a mixed chimera approach. WT CD45.1+ bone marrow and CD45.2+Cardif−/− bone marrow were mixed 1:1 and transplanted into irradiated CD45.1+/CD45.2+ recipient mice (Fig. 6A). After 10 weeks of reconstitution we assessed the phenotype of NK cells in various organs. We found that CD45.1+ and Cardif−/− cells contributed equally to the total number of CD45+ cells in the reconstituted bone marrow (Fig. 6B). However, there were slight, but consistently lower percentages of Cardif−/− origin NK (CD45.1−CD45.2+NK1.1+CD3−CD19−) cells in the bone marrow of chimeric mice compared to WT CD45.1 origin NK cells (data not shown). We found that this NK cell specific phenotype was more pronounced in the periphery (Fig. 6C). We found that Cardif−/− NK cells reconstituted only ~40% while CD45.1+ NK cells reconstituted ~60% of total NK cells in the spleen and liver (Fig. 6D). We also observed a slight decrease of the CD27−CD11b+ subset within Cardif−/− NK cells in the spleen and liver, similar to what we observed in the global knockout mice (Fig. 6E and 1C). The decrease in Cardif−/− CD27−CD11b+ NK cells was accompanied by an increase in CD27+CD11b− Cardif−/− NK cells in both the spleen and liver of the mixed bone marrow chimeric mice (Fig. 6E).

Figure 6.

Cardif−/− NK cells show maturation defect in 1:1 bone marrow chimeric mice. (A) Schematic diagram of method used to create 1:1 mixed bone marrow chimeric mice. Cardif−/− (CD45.2) and CD45.1 bone marrow were intravenously injected into CD45.1/.2 recipient mice in a 1:1 ratio. Mice were harvested10 weeks after injection. (B) Representative plot depicting equal amounts of WT and Cardif−/− CD45+ cells in the bone marrow. (C) Representative plots that show the ratios of CD45.1 and Cardif−/− cells in the liver in specific populations: live cells → CD3−CD19− → NK1.1+CD3−CD19− → NK1.1+CD3−CD19− → NK1.1+CD3−CD19−CD27−CD11b+ (upper panels). (D) Representative bar graphs show the contribution of cells from CD45.1 and Cardif−/− origins to total NK1.1+CD3−CD19− cells in spleen and liver. (E) Representative bar graphs depict the distribution of WT (CD45.1) and Cardif−/− NK cells based on the 4 maturation stages, denoted by CD27 and CD11b in the spleen and liver of 1:1 mixed bone marrow chimeric mice. (F) Bar graphs depict the production of CD107a (left panel) and Granzyme B (right panel) by NK cells. (G) Bar graphs depict the percentage of Caspase-3+ NK cells. Representative plots and bar graph depict the percentage of Caspase-3+ CD27−CD11b+ NK cells (middle and right panels). (H) Bar graphs depict the percentage of Ki-67+ NK cells. Experiments were performed twice (A–E) or once (F–H). For all, n=6 mice/group/experiment. Data are means ± SEM. *p< 0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

We also investigated the function of Cardif−/− NK cells in the chimeric mice. We found that although Cardif−/− NK cells and WT NK cells displayed a similar amount of degranulation, granzyme B production was lower in Cardif−/− NK cells (Fig. 6F). In addition, we found that more Cardif−/− NK cells are caspase-3+ compared to WT NK cells in chimeric mice (Fig. 6G). Similar to global knockout mice, CD27−CD11b+ Cardif−/− NK cells in chimeric mice have the greatest increase in apoptosis (Fig. 6G). We examined proliferation of WT and Cardif−/− NK cells in chimeric mice using Ki-67 and found that both WT and Cardif−/− NK cells proliferated at the same rate (Fig. 6H).

Signaling via Cardif leads to the production of Type I IFN. We, along with other groups, have found that similar to Cardif−/− mice, IFNAR1−/− mice have fewer terminally differentiated NK cells and abrogated functionality in the absence of type I IFN signaling (27, 28, 43, 44) (Supp. Fig. 3). Gough et al., have theorized that low homeostatic levels of type I IFN are required in the absence of infection to sustain levels of STAT proteins in the cytoplasm of various immune cells and consequently maintain normal cell function upon activation (30). Thus, we hypothesized that IFN-β signaling was likely impaired in response to Cardif deletion since Cardif−/− NK cells have low intracellular levels of STAT1 (Fig. 3). In an attempt to rescue NK maturation, we treated WT and Cardif−/− NK cells with IFN-β in vitro. Similar to Brady et al., we noticed drastically reduced levels of CD11b expression on NK cells in culture (45). This made it difficult to confidently identify the maturation stages of NK cells. We did however, measure total expression of CD11b and KLRG1 in the cultured NK cells. Both CD11b and KLRG1 expression significantly increased with IFN-β treatment in WT and Cardif−/− NK cells (Supp. Fig. 3). Still, CD11b and KLRG1 levels were not restored to those of WT with IFN-β stimulation.

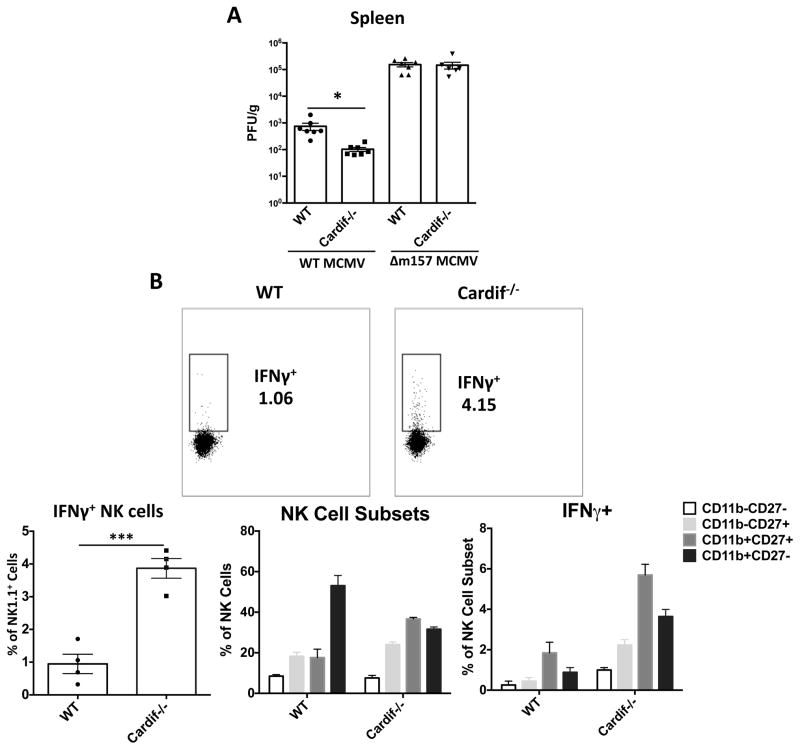

Cardif−/− mice show enhanced NK-mediated control of MCMV infection

NK cells are a key component of the host innate response required to control mouse cytomegalovirus (MCMV) (46), and is a commonly used viral model for assessing NK effector function. MCMV replication in Cardif−/− mice was controlled ~10 fold better than that seen in WT mice at day 4 after infection (Fig. 7A). However, infection with an MCMV mutant lacking the viral m157 protein (detected by Ly49h-expressing NK cells), resulted in no difference in viral control between Cardif−/− and WT mice (Fig. 7A) (36, 47–49). In addition, depletion of NK cells prior to MCMV infection also normalized viral replication to wild-type levels in Cardif−/− mice (Supp. Fig. 4). These data indicate the better control of MCMV seen in Cardif−/− mice is due to enhanced NK-mediated effector function(s). We have previously shown that a proportion of splenic NK cells express IFNγ at ~12h post MCMV infection in response to the first wave of Type I IFN produced, and this is a key time point regulating antiviral control in subsequent days (36, 50). Mack et al. have also described an early production of IFNγ by NK cells that is STAT4 and Type I IFN dependent during LCMV infection (51). Consequently, we specifically chose to measure NK IFNγ production at 12h after MCMV infection because type I IFN produced by infected splenic stromal cells is the primary cytokine driving this at this early time point, as opposed to pDC-produced IL-12 which is the primary inducer of NK IFNγ at 36h (36). We hypothesized that the STAT1/STAT4 ratio present in Cardif−/− NK cells might result in enhanced IFNγ production by NK cells at 12h after MCMV infection, potentially accounting for the observed increase in antiviral defense. Indeed, at 12h post infection, ~4 fold higher numbers of NK cells in Cardif−/− mice produced IFNγ than was seen in WT mice (Fig. 7B). All Cardif−/− NK cell subsets produced more IFNγ+ when compared to their WT counterparts; however, the highest percentage of IFNγ+cells was seen in the less mature CD27+CD11b+ subset as compared to the more mature CD27−CD11b+ NK cells. In addition to the CD27+CD11b+ NK subset containing the highest percentage of IFNγ+ cells in MCMV infected WT and Cardif−/− spleens, Cardif−/− spleens also contained nearly twice the normal proportion of these cells (Fig. 7B). These data support a model where increased numbers of CD27+CD11b+ NK cells in Cardif−/− mice, as well as enhanced STAT1/STAT4 ratios, is largely responsible for the increased IFNγ production observed in their NK cell compartment in response to initial MCMV infection, and likely underlies the enhanced control of MCMV infection in spleens of Cardif deficient mice.

Figure 7.

Cardif−/− mice show heightened NK activation and enhanced control of MCMV infection. (A) WT and Δm157 MCMV replication levels in spleens of day 4 infected WT and Cardif−/− mice (B) Representative plots of IFNγ production by NK cells at 12h in MCMV infected mice (middle panel), and bar graphs quantifying this in multiple mice and in NK cell subsets (lower panels). Bar graph portraying the percentage of IFNγ+ cells within NK cell subsets in the spleens of mice 12h post infection (lower right panel). For all, n ≥ 3 mice/group. Experiments were performed twice with at least 3 mice/group, and panel A shows the combined data from two separate experiments, with panel B being representative from a single experiment. Data are means ± SEM. *p< 0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001. PFU; plaque forming units

Discussion

We have discovered a novel intrinsic role for Cardif in the maturation and function of NK cells. It is widely accepted that Cardif is vital for antiviral signaling in response to RIG-I and MDA-5 activation; however, several studies indicate that Cardif and other components in this pathway have relatively unexplored non-viral functions (13–16). Cardif has been shown to reduce the severity of EAE in mice, activate the NLRP3 inflammasome, and regulate TLR7 expression in B cells. There are currently no reports however, describing the requirement for, or involvement of, Cardif in NK cell development. In this report, we describe a novel and cell-intrinsic role for Cardif in the homeostatic maturation and function of NK cells.

We discovered that Cardif mice have fewer splenic NK cells when compared to WT mice, and Cardif−/− NK cells are ~ 40–45% more likely to lack CD49b, a marker of mature NK cells. Splenic and liver Cardif−/− NK cells populations also have ~30% and ~60% fewer terminally differentiated NK cells, respectively. Markers associated with NK maturation, Ly49C/I and KLRG1 are also lower in Cardif−/− NK cells. Functionally, we found that Cardif−/− NK cells had lower cytotoxic activity, as Cardif−/− NK cells did not degranulate nor produce as much granzyme B, or kill target cells as well as WT NK cells. However, we observed no changes in IFNγ production in Cardif-deficient NK cells. We did not measure production of other cytokines by Cardif NK cells in the current study. Since, STAT1 has been shown to regulate the cytotoxicity functions of NK cells while STAT4 governs IFNγ production by NK cells, we measured total STAT protein and protein phosphorylation. STAT1 protein levels and phosphorylation were considerably reduced in Cardif−/− NK cells. In contrast, pSTAT4/STAT4 protein levels were higher in Cardif−/− NK cells. These data suggest that the diminished cytotoxicity of Cardif−/− NK cells is due to the reduced intracellular levels of STAT1. Though there is an increase of pSTAT4/STAT4 in Cardif−/− NK cells, this increase may not have translated into increased levels of IFNγ in our ex vivo stimulation assays because the already high overall STAT4 levels in WT NK cells is saturating. However, the altered STAT1/STAT4 ratio could have more dramatic consequences in the context of NK effector function in vivo, as appears to be the case from our studies with MCMV.

Cardif likely plays a role in stabilizing NK cells and preventing their apoptosis. A recent report indicated that Cardif associates with caspase-8 to induce apoptosis via caspase-3 in response to viral infection (52). Our data shows that Cardif deficiency increases apoptosis in NK cells, particularly in terminally differentiated CD27−CD11b+ NK cells. Moreover, our data suggests that the presence of Cardif decreases NK cell proliferation, predominantly in CD27+CD11b− and CD27+CD11b+ NK cells. Cardif’s apparent role in apoptosis and proliferation in NK cells explains much of the immature phenotype seen in NK cells from Cardif−/− mice (Fig. 1). The lack of proliferation in CD27+CD11b− and CD27+CD11b+ NK cells suggests a lack of differentiation into terminally differentiated stage 4 NK cells. Together our data suggest that Cardif−/− mice have fewer total NK cells, with a lower percentage of terminally differentiated CD27−CD11b+ NK cells, and this is likely caused by an increase in CD27−CD11b+ NK cell death and a decrease in proliferation of early-stage CD27+CD11b− and CD27+CD11b+ NK cells. NF-κB is a major downstream target of Cardif signaling along with Type-I IFN production (5, 6). NF-κB is known to be involved in cell survival in multiple cell types, including B and T cells (53). Yet, little is known about NF-κB activity in NK cells. A few reports suggest that changes in NF-kB signaling regulate NK cell proliferation, Ly49 expression, and increased apoptosis (53–55). NF-κB signaling is tightly regulated in NK cells and changes in NF-κB activity are likely to perturb NK cell survival, and we surmise that the absence of a Cardif-NF-κB signaling axis may contribute to the differences in observed NK cell survival.

Our mixed bone marrow chimera experiments revealed that Cardif is intrinsically required for optimal terminal differentiation of NK cells. Moreover, Cardif is intrinsically required for the fitness and survival of NK cells in peripheral organs, as Cardif−/− NK cell numbers were lower than WT in the periphery of the mixed chimeric mice and CD27−CD11b+ terminally differentiated NK cells were nearly twice as likely to be derived from WT mice in this mixed chimera scenario. We also found that increased apoptosis and decreased granzyme B levels in Cardif−/− NK cells are due to cell intrinsic deficiencies. The decreased proliferation and increased degranulation that was observed in Cardif−/− mice however is not cell intrinsic.

We initially thought that the cell-extrinsic factor acting upon Cardif−/− NK cells was IFN-β; however, we found that treatment with IFN-β in vitro, though somewhat effective, is not able to completely rescue the maturation phenotype that is present in Cardif−/− NK cells. Type I IFN is known to indirectly affect the differentiation of NK cells by upregulating the amount of IL-15 and IL-15Rα present on dendritic cells (56, 57). IL-15 transpresentation by dendritic cells has been shown to have a dose-dependent effect on the development, maturation, and proliferation of NK cells and NKT cells (58–60). IL-15 transpresentation is required for the expression of NK1.1 on NKT cells in the thymus. We have found that fewer NKT cells in the thymus express NK1.1 in young Cardif−/− mice, which leads us to believe that there may be a perturbation of ‘basal’ Type-I IFN production in Cardif−/− mice that leads to lower amounts of IL-15 transpresentation (data not shown). We also found that Cardif−/− dendritic cells express lower amounts of IL-15/IL-15Rα complexes when stimulated with TLR9 agonists (data not shown). The involvement of IL-15 transpresentation in the NK phenotype of Cardif−/− mice is also supported by results that the proliferation and cytotoxicity of Cardif−/− NK cells is normal in WT hosts, two effector functions that are mediated by IL-15 transpresentation. Thus, Cardif appears to regulate the maturation and function of NK cells by both direct and indirect mechanisms. Further studies to delineate the role of type-I IFNs in the terminal differentiation of NK cells in the absence of Cardif and other RIG-I molecules will be of interest, particularly in the context of viral immunity and autoimmune diseases.

MCMV infection was utilized as another model to test the function of Cardif−/− NK cells, as these cells are key for innate defense to this virus. Somewhat surprisingly, we found that Cardif−/− mice controlled MCMV replication better than WT mice at times of peak acute infection, and this enhanced control in the absence of Cardif was shown to be NK-dependent by both depleting NK cells and using a MCMVΔm157 mutant virus (47–49). This amplified innate antiviral defense was consistent with an increased percentage of IFNγ+ NK cells in the spleen seen at 12h of infection, a time point when innate defense to MCMV is ‘kick-started’ and the baseline for MCMV replication is being established (61). This initial IFNγ production by NK cells occurs in response to Type I IFN produced by MCMV infected marginal zone stromal cells in the spleen, a cell type which MCMV shows specific tropism for due to their differentiation by constitutive lymphotoxin-αβ signaling (36, 50). Data from Mack et al. also shows that very early after LCMV infection, a short burst of IFNγ is produced by NK cells via the Type I IFN pathway, independent of IL-12 (32). In turn, Doring et al. have shown that Cardif−/− pDCs, mDCs, and macrophages produce similar levels of IFN-α in response to MCMV (62), cells that produce the second-wave of innate cytokines in the spleen in response to MCMV generated from the infected marginal zone stroma (61). Together, this suggests that instead of type I-IFN being altered in MCMV infected Cardif−/− mice, which is perhaps not surprising since MCMV is a dsDNA virus, that Cardif−/− NK cells are more highly subject to activation by these key innate cytokines. Hayakawa et al. found that CD27+CD11b+ NK cells produced more IFNγ than CD27−CD11b+ NK cells in response to cytokines and DC cross talk (22). We also found higher IFNg production by CD27+CD11b+ NK cells in response to MCMV, accounting for a substantial overall increase in NK cell IFNg seen in Cardif−/− mice. This suggests that the CD27−CD11b+ NK subset may preferentially contribute to MCMV control in some contexts, although this needs to be tested more directly. In addition, the prevalence of more unlicensed, Ly49C/I− NK cells in Cardif−/− mice may also contribute to the observed enhanced control of MCMV, as these cells are activated to a higher extent in the response to this virus due to fewer inhibitory mechanisms (63, 64). In contrast, these unlicensed Ly49C/I− NK cells are not as functional as licensed NK cells in contexts other than viral infection, such as tumor immunosurveillance, contributing to the reduced cytotoxicity of Cardif−/− NK cells seen in vitro (39). Also, lower STAT1/STAT4 ratios might prolong IFNγ production in by Cardif−/− NK, as it could take longer to induce high enough STAT1 levels in response to type I IFN to downregulate STAT4.

Increased Cardif NK cell activation in the context of MCMV infection may be indicative of a potentially broader role of Cardif in regulating autoimmunity. Indeed, Cardif has recently been associated with incidence of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). Pothlichet et al. described a loss-of-function MAVS (Cardif) variant in humans that is associated with SLE in African-Americans (65). Patients with this variant were characterized by low type I IFN levels and a lack of autoantibodies specific for RNA-binding protein. Similarly, Molineros et al. described a risk allele of IFIH1 (MDA5) in African Americans that is associated with an increased risk of SLE with downregulation of type I IFN signaling (66). Interestingly, SLE patients have reduced absolute numbers and a reduction in the cytolytic activity of NK cells, similar to the phenotype observed in Cardif−/− mice (67–71). Furthermore, just as in Cardif−/− mice, the NK cells of SLE patients have an increase in the number of immature NK cells and a concomitant decrease of mature cytotoxic NK cells. Future studies should investigate Cardif signaling in NK cells in the context of SLE to further delineate the effect of Cardif on NK cells and SLE pathogenesis.

Our data suggest that Cardif negatively regulates NK cell maturation and function in the absence of viral infection, but may result in their hyperreactivity in the context of pathogen infection. Several other publications have suggested a similar ‘dual role’ for Cardif; however clear mechanisms haven’t been established (7, 15, 16, 65). With regards to the role of Cardif in regulating immune cell homeostasis, tonic signaling through the Rig-I/MDA-5-Cardif axis triggered by endogenous agonists may play a role. There have been reports of endogenous agonists of Rig-I such as the small self-RNAs produced by RNase-L, IRE1α, and endogenous retroviral elements in the human genome (72–77). Recently, Dupuis-Maurin et al. discovered that overexpression of the transcription factor Sp1 (specificity protein 1) activates the Rig-I-Cardif pathway in the absence of a pathogen by stimulating the OAS-RNase-L pathway to produce small self-RNAs (78). Tonic Rig-I/MDA-5-Cardif signaling activity stimulated by Sp1 or other transcription factors may lead to low-level production of IFN-β as well as NF-κB activation. It is also possible that Cardif is involved in other signaling cascades rather than the RIG-I/MDA-5-Cardif axis, as Subramanian et al. recently reported the activity of Cardif in the NLRP3 inflammasome (14).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH F31 HL110668 (to L.D.H.), the American Diabetes Association 1-13-MUI-02 Award (to L.D.H. and C.C.H.), NIH R01 HL097368 (to C.C.H.) and NIH R01 AI101423 (to C.A.B).

We thank Amy Blatchley and Deborah Yoakum at LIAI for their assistance with mice, and the Imaging Facility at LIAI for excellent technical assistance with flow cytometry.

Abbreviations used in this article

- mNK

mature natural killer

- NK

natural killer

- MCMV

mouse cytomegalovirus

References

- 1.Takeuchi O, Akira S. Pattern recognition receptors and inflammation. Cell. 2010;140:805–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ireton RC, Gale M. RIG-I like receptors in antiviral immunity and therapeutic applications. Viruses. 2011;3:906–19. doi: 10.3390/v3060906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eisenächer K, Krug A. Regulation of RLR-mediated innate immune signaling--it is all about keeping the balance. Eur J Cell Biol. 2012;91:36–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2011.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meylan E, Curran J, Hofmann K, Moradpour D, Binder M, Bartenschlager R, Tschopp J. Cardif is an adaptor protein in the RIG-I antiviral pathway and is targeted by hepatitis C virus. Nature. 2005;437:1167–72. doi: 10.1038/nature04193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seth RB, Sun L, Ea CK, Chen ZJ. Identification and characterization of MAVS, a mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein that activates NF-kappaB and IRF 3. Cell. 2005;122:669–82. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kawai T, Takahashi K, Sato S, Coban C, Kumar H, Kato H, Ishii KJ, Takeuchi O, Akira S. IPS-1, an adaptor triggering RIG-I- and Mda5-mediated type I interferon induction. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:981–8. doi: 10.1038/ni1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu LG, Wang YY, Han KJ, Li LY, Zhai Z, Shu HB. VISA is an adapter protein required for virus-triggered IFN-beta signaling. Mol Cell. 2005;19:727–40. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kawai T, Akira S. TLR signaling. Cell Death Differ. 2006;13:816–25. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takamatsu S, Onoguchi K, Onomoto K, Narita R, Takahasi K, Ishidate F, Fujiwara TK, Yoneyama M, Kato H, Fujita T. Functional Characterization of Domains of IPS-1 Using an Inducible Oligomerization System. PLoS One. 2013;8:e53578. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Loo YM, Gale M. Immune signaling by RIG-I-like receptors. Immunity. 2011;34:680–92. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li X, Chiu Y. Mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein (MAVS) monitors commensal bacteria and induces an immune response that prevents experimental colitis. Proc …. 2011;108:17390–17395. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1107114108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang Y, Zhang HX, Sun YP, Liu ZX, Liu XS, Wang L, Lu SY, Kong H, Liu QL, Li XH, Lu ZY, Chen SJ, Chen Z, Bao SS, Dai W, Wang ZG. Rig-I−/− mice develop colitis associated with downregulation of G alpha i2. Cell Res. 2007;17:858–68. doi: 10.1038/cr.2007.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xu LG, Jin L, Zhang BC, Akerlund LJ, Shu HB, Cambier JC. VISA is required for B cell expression of TLR7. J Immunol. 2012;188:248–58. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Subramanian N, Natarajan K, Clatworthy MR, Wang Z, Germain RN. The Adaptor MAVS Promotes NLRP3 Mitochondrial Localization and Inflammasome Activation. Cell. 2013;153:348–61. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.02.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang F, Xia W, Liu F, Li J, Wang G, Gu J. Interferon regulator factor 1/retinoic inducible gene I (IRF1/RIG-I) axis mediates 25-hydroxycholesterol-induced interleukin-8 production in atherosclerosis. Cardiovasc Res. 2012;93:190–9. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvr260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dann A, Poeck H, Croxford AL, Gaupp S, Kierdorf K, Knust M, Pfeifer D, Maihoefer C, Endres S, Kalinke U, Meuth SG, Wiendl H, Knobeloch KP, Akira S, Waisman A, Hartmann G, Prinz M. Cytosolic RIG-I-like helicases act as negative regulators of sterile inflammation in the CNS. Nat Neurosci. 2012;15:98–106. doi: 10.1038/nn.2964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vivier E, Tomasello E, Baratin M, Walzer T, Ugolini S. Functions of natural killer cells. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:503–10. doi: 10.1038/ni1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gordon SM, Chaix J, Rupp LJ, Wu J, Madera S, Sun JC, Lindsten T, Reiner SL. The transcription factors T-bet and Eomes control key checkpoints of natural killer cell maturation. Immunity. 2012;36:55–67. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Daussy C, Faure F, Mayol K, Viel S, Gasteiger G, Charrier E, Bienvenu J, Henry T, Debien E, Hasan Ua, Marvel J, Yoh K, Takahashi S, Prinz I, de Bernard S, Buffat L, Walzer T. T-bet and Eomes instruct the development of two distinct natural killer cell lineages in the liver and in the bone marrow. J Exp Med. 2014;211:563–77. doi: 10.1084/jem.20131560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fathman JW, Bhattacharya D, Inlay Ma, Seita J, Karsunky H, Weissman IL. Identification of the earliest natural killer cell-committed progenitor in murine bone marrow. Blood. 2011;118:5439–47. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-04-348912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.De Colvenaer V, Taveirne S, Delforche M, De Smedt M, Vandekerckhove B, Taghon T, Boon L, Plum J, Leclercq G. CD27-deficient mice show normal NK-cell differentiation but impaired function upon stimulation. Immunol Cell Biol. 2011;89:803–11. doi: 10.1038/icb.2010.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hayakawa Y, Smyth M. CD27 dissects mature NK cells into two subsets with distinct responsiveness and migratory capacity. J Immunol. 2006;176:1517–1524. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.3.1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chiossone L, Chaix J, Fuseri N, Roth C, Vivier E, Walzer T. Maturation of mouse NK cells is a 4-stage developmental program. Blood. 2009;113:5488–96. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-10-187179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fu B, Wang F, Sun R, Ling B, Tian Z, Wei H. CD11b and CD27 reflect distinct population and functional specialization in human natural killer cells. Immunology. 2011;133:350–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2011.03446.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huntington ND, Tabarias H, Fairfax K, Brady J, Hayakawa Y, Degli-Esposti Ma, Smyth MJ, Tarlinton DM, Nutt SL. NK cell maturation and peripheral homeostasis is associated with KLRG1 up-regulation. J Immunol. 2007;178:4764–70. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.8.4764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nguyen KB, Salazar-Mather TP, Dalod MY, Van Deusen JB, Wei X, Liew FY, Caligiuri Ma, Durbin JE, Biron Ca. Coordinated and distinct roles for IFN-alpha beta, IL-12, and IL-15 regulation of NK cell responses to viral infection. J Immunol. 2002;169:4279–87. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.8.4279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Swann JB, Hayakawa Y, Zerafa N, Sheehan KCF, Scott B, Schreiber RD, Hertzog P, Smyth MJ. Type I IFN contributes to NK cell homeostasis, activation, and antitumor function. J Immunol. 2007;178:7540–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.12.7540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mizutani T, Neugebauer N. Conditional IFNAR1 ablation reveals distinct requirements of Type I IFN signaling for NK cell maturation and tumor surveillance. Oncoimmunology. 2012;1:1027–1037. doi: 10.4161/onci.21284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee CK, Rao DT, Gertner R, Gimeno R, Frey aB, Levy DE. Distinct requirements for IFNs and STAT1 in NK cell function. J Immunol. 2000;165:3571–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.7.3571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gough DJ, Messina NL, Clarke CJP, Johnstone RW, Levy DE. Constitutive type I interferon modulates homeostatic balance through tonic signaling. Immunity. 2012;36:166–74. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miyagi T, Gil MP, Wang X, Louten J, Chu W-M, Biron Ca. High basal STAT4 balanced by STAT1 induction to control type 1 interferon effects in natural killer cells. J Exp Med. 2007;204:2383–96. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mack E, Kallal L, Demers D, Biron C. Type 1 interferon induction of natural killer cell gamma interferon production for defense during lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus infection. MBio. 2011;2:e00169–11. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00169-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Michallet M-C, Meylan E, Ermolaeva Ma, Vazquez J, Rebsamen M, Curran J, Poeck H, Bscheider M, Hartmann G, König M, Kalinke U, Pasparakis M, Tschopp J. TRADD protein is an essential component of the RIG-like helicase antiviral pathway. Immunity. 2008;28:651–61. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hanna RN, Carlin LM, Hubbeling HG, Nackiewicz D, Green AM, Punt Ja, Geissmann F, Hedrick CC. The transcription factor NR4A1 (Nur77) controls bone marrow differentiation and the survival of Ly6C- monocytes. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:778–85. doi: 10.1038/ni.2063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McWhorter AR, Smith LM, Masters LL, Chan B, Shellam GR, Redwood AJ. Natural Killer Cell Dependent Within-Host Competition Arises during Multiple MCMV Infection: Consequences for Viral Transmission and Evolution. PLoS Pathog. 2013:9. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Verma S, Wang Q, Chodaczek G, Benedict Ca. Lymphoid-Tissue Stromal Cells Coordinate Innate Defense to Cytomegalovirus. J Virol. 2013;87:6201–6210. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00113-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Seillet C, Huntington ND, Gangatirkar P, Axelsson E, Minnich M, Brady HJM, Busslinger M, Smyth MJ, Belz GT, Carotta S. Differential requirement for Nfil3 during NK cell development. J Immunol. 2014;192:2667–76. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1302605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sun JC. Re-educating natural killer cells. J Exp Med. 2010;207:2049–52. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim S, Poursine-Laurent J, Truscott SM, Lybarger L, Song YJ, Yang L, French AR, Sunwoo JB, Lemieux S, Hansen TH, Yokoyama WM. Licensing of natural killer cells by host major histocompatibility complex class I molecules. Nature. 2005;436:709–13. doi: 10.1038/nature03847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yokoyama WM, Kim S. Licensing of natural killer cells by self-major histocompatibility complex class I. Immunol Rev. 2006;214:143–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2006.00458.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Robbins SH, Tessmer MS, Van Kaer L, Brossay L. Direct effects of T-bet and MHC class I expression, but not STAT1, on peripheral NK cell maturation. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:757–65. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fernandez NC, Treiner E, Vance RE, Jamieson aM, Lemieux S, Raulet DH. A subset of natural killer cells achieve self-tolerance without expressing inhibitory receptors specific for self MHC molecules. Blood. 2005;105:4416–4424. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-08-3156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Beuneu H, Deguine J, Bouvier I, Di Santo JP, Albert ML, Bousso P. Cutting Edge: A dual role for type I IFNs during polyinosinic-polycytidylic acid-induced NK cell activation. J Immunol. 2011;187:2084–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1004210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Marçais A, Viel S, Grau M, Henry T, Marvel J, Walzer T. Regulation of Mouse NK Cell Development and Function by Cytokines. Front Immunol. 2013;4:450. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brady J, Carotta S, Thong RPL, Chan CJ, Hayakawa Y, Smyth MJ, Nutt SL. The interactions of multiple cytokines control NK cell maturation. J Immunol. 2010;185:6679–88. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Biron Ca, Nguyen KB, Pien GC, Cousens LP, Salazar-Mather TP. Natural killer cells in antiviral defense: function and regulation by innate cytokines. Annu Rev Immunol. 1999;17:189–220. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.17.1.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bubić I, Wagner M, Krmpotić A, Saulig T, Kim S, Yokoyama WM, Jonjić S, Koszinowski UH. Gain of virulence caused by loss of a gene in murine cytomegalovirus. J Virol. 2004;78:7536–7544. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.14.7536-7544.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Orr MT, Sun JC, Hesslein DGT, Arase H, Phillips JH, Takai T, Lanier LL. Ly49H signaling through DAP10 is essential for optimal natural killer cell responses to mouse cytomegalovirus infection. J Exp Med. 2009;206:807–817. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brown MG, Dokun aO, Heusel JW, Smith HR, Beckman DL, Blattenberger Ea, Dubbelde CE, Stone LR, Scalzo aa, Yokoyama WM. Vital involvement of a natural killer cell activation receptor in resistance to viral infection. Science. 2001;292:934–937. doi: 10.1126/science.1060042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schneider K, Loewendorf A, De Trez C, Fulton J, Rhode A, Shumway H, Ha S, Patterson G, Pfeffer K, Nedospasov Sa, Ware CF, Benedict Ca. Lymphotoxin-Mediated Crosstalk between B Cells and Splenic Stroma Promotes the Initial Type I Interferon Response to Cytomegalovirus. Cell Host Microbe. 2008;3:67–76. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2007.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Maslowski KM, Vieira AT, Ng A, Kranich J, Sierro F, Yu D, Schilter HC, Rolph MS, Mackay F, Artis D, Xavier RJ, Teixeira MM, Mackay CR. Regulation of inflammatory responses by gut microbiota and chemoattractant receptor GPR43. Nature. 2009;461:1282–6. doi: 10.1038/nature08530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.El Maadidi S, Faletti L, Berg B, Wenzl C, Wieland K, Chen ZJ, Maurer U, Borner C. A novel mitochondrial MAVS/Caspase-8 platform links RNA virus-induced innate antiviral signaling to Bax/Bak-independent apoptosis. J Immunol. 2014;192:1171–83. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Samson S, Mémet S, VCACF, Richard O, ND, IA, DSJP Combined deficiency in IκBα and IκBα reveals a critical window of NF-κB activity in natural killer cell differentiation. Blood. 2004;103:4573–4580. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-08-2975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pascal V, Nathan NR, Claudio E, Siebenlist U, Anderson SK. NF-κB p50/p65 Affects the Frequency of Ly49 Gene Expression by NK Cells. J Immunol. 2007;179:1751–1759. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.3.1751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tato CM, Mason N, Artis D, Shapira S, Caamano JC, Bream JH, Liou H-C, Hunter Ca. Opposing roles of NF-kappaB family members in the regulation of NK cell proliferation and production of IFN-gamma. Int Immunol. 2006;18:505–13. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lucas M, Schachterle W, Oberle K, Aichele P, Diefenbach A. Dendritic cells prime natural killer cells by trans-presenting interleukin 15. Immunity. 2007;26:503–17. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Baranek T, Manh T-PV, Alexandre Y, Maqbool MA, Cabeza JZ, Tomasello E, Crozat K, Bessou G, Zucchini N, Robbins SH, Vivier E, Kalinke U, Ferrier P, Dalod M. Differential responses of immune cells to type I interferon contribute to host resistance to viral infection. Cell Host Microbe. 2012;12:571–84. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lee GA, Liou Y-H, Wang S-W, Ko K-L, Jiang S-T, Liao N-S. Different NK cell developmental events require different levels of IL-15 trans-presentation. J Immunol. 2011;187:1212–21. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Castillo EF, Schluns KS. Regulating the immune system via IL-15 transpresentation. Cytokine. 2012;59:479–90. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2012.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gordy LE, Bezbradica JS, Flyak AI, Spencer CT, Dunkle A, Sun J, Stanic AK, Boothby MR, He Y-W, Zhao Z, Van Kaer L, Joyce S. IL-15 regulates homeostasis and terminal maturation of NKT cells. J Immunol. 2011;187:6335–45. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Verma S, Benedict Ca. Sources and signals regulating type I interferon production: lessons learned from cytomegalovirus. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2011;31:211–218. doi: 10.1089/jir.2010.0118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Doring M, Lessin I, Frenz T, Spanier J, Kessler a, Tegtmeyer P, Da F, Thiel N, Trilling M, Lienenklaus S, Weiss S, Scheu S, Messerle M, Cicin-Sain L, Hengel H, Kalinke U. M27 Expressed by Cytomegalovirus Counteracts Effective Type I Interferon Induction of Myeloid Cells but Not of Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cells. J Virol. 2014;88:13638–13650. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00216-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Orr MT, Murphy WJ, Lanier LL. “Unlicensed” natural killer cells dominate the response to cytomegalovirus infection. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:321–7. doi: 10.1038/ni.1849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Orr MT, Lanier LL. Natural Killer Cell Licensing During Viral Infection. In: Pulendran B, Katsikis PD, Schoenberger SP, editors. Crossroads Between Innate and Adaptive Immunity III. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. Vol. 780. Springer New York; New York, NY: 2011. pp. 37–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pothlichet J, Niewold TB, Vitour D, Solhonne B, Crow MK, Si-Tahar M. A loss-of-function variant of the antiviral molecule MAVS is associated with a subset of systemic lupus patients. EMBO Mol Med. 2011;3:142–52. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201000120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Molineros JE, Maiti AK, Sun C, Looger LL, Han S, Kim-Howard X, Glenn S, Adler A, Kelly Ja, Niewold TB, Gilkeson GS, Brown EE, Alarcón GS, Edberg JC, Petri M, Ramsey-Goldman R, Reveille JD, Vilá LM, Freedman BI, Tsao BP, Criswell La, Jacob CO, Moore JH, Vyse TJ, Langefeld CL, Guthridge JM, Gaffney PM, Moser KL, Scofield RH, Alarcón-Riquelme ME, Williams SM, Merrill JT, James Ja, Kaufman KM, Kimberly RP, Harley JB, Nath SK. Admixture mapping in lupus identifies multiple functional variants within IFIH1 associated with apoptosis, inflammation, and autoantibody production. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003222. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Poggi A, Zocchi MR. NK Cell Autoreactivity and Autoimmune Diseases. Front Immunol. 2014;5:27. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Park Y-W, Kee S-J, Cho Y-N, Lee E-H, Lee H-Y, Kim E-M, Shin M-H, Park J-J, Kim T-J, Lee S-S, Yoo D-H, Kang H-S. Impaired differentiation and cytotoxicity of natural killer cells in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:1753–63. doi: 10.1002/art.24556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Henriques A, Teixeira L, Inês L, Carvalheiro T, Gonçalves A, Martinho A, Pais ML, da Silva JAP, Paiva A. NK cells dysfunction in systemic lupus erythematosus: relation to disease activity. Clin Rheumatol. 2013;32:805–13. doi: 10.1007/s10067-013-2176-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hervier B, Beziat V, Haroche J, Mathian A, Lebon P, Ghillani-Dalbin P, Musset L, Debré P, Amoura Z, Vieillard V. Phenotype and function of natural killer cells in systemic lupus erythematosus: excess interferon-γ production in patients with active disease. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:1698–706. doi: 10.1002/art.30313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Schepis D, Gunnarsson I, Eloranta M-L, Lampa J, Jacobson SH, Kärre K, Berg L. Increased proportion of CD56bright natural killer cells in active and inactive systemic lupus erythematosus. Immunology. 2009;126:140–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2008.02887.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Malathi K, Dong B, Gale M, Silverman RH. Small self-RNA generated by RNase L amplifies antiviral innate immunity. Nature. 2007;448:816–9. doi: 10.1038/nature06042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ezelle H, Hassel B. Pathologic effects of RNase-L dysregulation in immunity and proliferative control. Front Biosci (Schol Ed) 2012:767–786. doi: 10.2741/s298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cho Ja, Lee A-H, Platzer B, Cross BCS, Gardner BM, De Luca H, Luong P, Harding HP, Glimcher LH, Walter P, Fiebiger E, Ron D, Kagan JC, Lencer WI. The Unfolded Protein Response Element IRE1α Senses Bacterial Proteins Invading the ER to Activate RIG-I and Innate Immune Signaling. Cell Host Microbe. 2013;13:558–69. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 75.Malathi K, Saito T, Crochet N, Barton DJ, Gale M, Silverman RH. RNase L releases a small RNA from HCV RNA that refolds into a potent PAMP. RNA. 2010;16:2108–19. doi: 10.1261/rna.2244210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zeng M, Hu Z, Shi Z, Li X, Beutler B. MAVS, cGAS, and endogenous retroviruses in T-independent B cell responses. Science. 2014;346:1486–1492. doi: 10.1126/science.346.6216.1486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 77.Grasset BEK, Cerutti A. Retroviral help for B cells. Science. 2014;346:1454. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa3263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Dupuis-Maurin V, Brinza L, Baguet J, Plantamura E, Schicklin S, Chambion S, Macari C, Tomkowiak M, Deniaud E, Leverrier Y, Marvel J, Michallet MC. Overexpression of the Transcription Factor Sp1 Activates the OAS-RNAse L-RIG-I Pathway. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0118551. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0118551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.