Abstract

Sorting nexin proteins (SNXs) and the cargo-selective retromer complex play key roles in receptor recycling from endosomes to the cell surface. A global proteomics analysis reveals a collection of cell surface proteins that rely on SNX27 and the retromer complex for their cell surface localization at steady state.

The mechanisms by which receptors are recycled from early endosomes to the cell surface have broad implications for our understanding of normal cell physiology and the molecular basis of several disease states. SNXs represent a large family of proteins that are implicated in receptor recycling1,2, and SNX27 is involved in the recycling of the Kir3 potassium channel3 and the β2 adrenergic receptor4,5. In this issue, Steinberg et al.6 use a sophisticated proteomics approach to catalogue the cohort of proteins that bind to SNX27, and those whose surface expression is altered following loss of SNX27 from cells. This work shows that SNX27 is important for the sorting and stability of a significant number of cell surface proteins, and documents a discrete recognition pathway for the localization of proteins needed for glucose and ion transport in mammalian cells.

SNXs contain a PHOX-homology (PX) domain that enables them to bind phosphatidylinositol-3-phosphate (PtdIns(3)P) on early endosomes, where most PtdIns(3)P is localized. Twelve mammalian SNX proteins also contain a bin–amphiphysin-rvs (BAR) domain and are thus called SNX–BAR proteins. BAR domains dimerize to form a curved surface that interacts with membranes and stabilizes membrane curvature7. BAR-domain proteins are important for the tubulation of endosomal membranes that accompanies (and may even drive) the process by which receptors are sorted for recycling.

Certain SNX proteins work in concert with the highly conserved retromer complex that is critical for endosomal protein recycling8,9. In yeast, retromer is comprised of a trimer of subunits encoded by the Vps (vacuolar protein sorting) genes VPS35, VPS29 and VPS26 (which mediate cargo selection), together with a dimer of two SNX–BAR proteins, Vps5p and Vps17p. In mammals, the Vps5p homologues SNX1 and SNX2 dimerize with a Vps17p orthologue, SNX5 or SNX6. Retromer was first shown to be important for the recycling of proteins from endosomes back to the Golgi complex8. More recent work has shown a role for the retromer in recycling of certain receptors from endosomes back to the cell surface9. Retromer also recruits the macromolecular WASH (Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein and SCAR homologue) complex to endosomes to promote the formation of branched actin networks9. The WASH complex may help to couple actin polymerization to drive tubule formation from the early endosome compartment. The term, retromer, will be used here to refer to a complex of VPS35, VPS29 and VPS26 proteins.

Certain SNX proteins recognize cargo directly: a PDZ domain in SNX27 enables it to bind to PDZ domain binding sites in the C-termini of the Kir3 potassium channel3 and the β2 adrenergic receptor4; SNX17 binds to β1 integrins through its so-called FERM-like (4.1–ezrin–radixin–moesin) domain10. Like SNX17, SNX27 also contains a FERM-like domain. These SNX–receptor interactions are critical for the endosomal recycling of their binding partners3–5.

Given the importance of SNX proteins in receptor recycling, characterization of their cargoes can provide mechanistic detail to our understanding of a broad swath of mammalian cell functions. To this end, Steinberg et al.6 first used SILAC (stable isotope labelling by amino acids in culture) to identify interaction partners of GFP–SNX27. Like already characterized binding partners, many of the 77 interacting proteins also contain a PDZ ‘ligand’ binding site for the SNX27 PDZ domain.

To determine if the SNX27 binding partners rely on SNX27 for their trafficking, Steinberg et al. used short interfering RNA (siRNA) to deplete cells of SNX27 and then evaluated the composition of the cell surface proteome to determine if binding partner localization had been altered. Of 122 proteins lost from the surface of cells depleted of SNX27, 81 were also lost from the cell surface of cells depleted of the retromer subunit VPS35. The SNX27- and retromer-dependent cargoes included the glucose transporter GLUT1, the Menkes disease copper transporter ATP7A and the ZnT1 zinc transporter. In contrast, about half of the proteins lost from the surface of VPS35-depleted cells did not change following loss of SNX27, implicating another set of cargo receptors for that class of protein. Indeed, 37 of 81 proteins affected by SNX27 and VPS35 depletion were enriched in the SNX27 interactome.

Loss of SNX27 and retromer led to the enhanced turnover of the proteins studied, suggesting a positive sorting role for SNX27 in diverting proteins from degradation. Earlier work indicated that loss of the VPS26A retromer subunit led to an increase in cell surface mannose 6-phosphate receptors8 (rather than a decrease), presumably because retromer was needed to remove these proteins from endosomes and carry them back to the Golgi complex. Thus it was surprising that in the present study, very few proteins actually increased in their cell surface abundance following loss of the VPS35 retromer subunit. This suggests that the major function of retromer in mammalian cells is in receptor recycling to the cell surface, rather than recycling to the Golgi complex. In the absence of VPS26A protein8, it is possible that the VPS26B protein influenced the trafficking of mannose 6-phosphate receptors in a manner not possible in cells lacking VPS35. This finding is consistent with work from Kornfeld and colleagues11, who were the first to show that only a small number of proteins recycle from the cell surface to the Golgi. Does SNX3 play a special role in endosome-to-Golgi transport2,9? The recent finding that transferrin receptor recycling relies on SNX3 (ref. 12) excludes this neat, directional categorization.

How does SNX27 link to other SNX–BAR proteins, the retromer complex and the WASH complex? Steinberg et al.6 show that the SNX27 FERM-like domain binds to the membrane bending SNX–BAR protein SNX1. Although SNX17 and SNX31 also contain FERM domains, they are not SNX–BAR protein partners6. The PDZ domain of SNX27 binds to the retromer subunit VPS26, and can do so independently of its ability to engage cargo. Thus, SNX27 works in concert with the retromer subunits to recognize and sort cargoes into SNX–BAR tubules of early endosomes, driving their WASH-enhanced recycling to the cell surface.

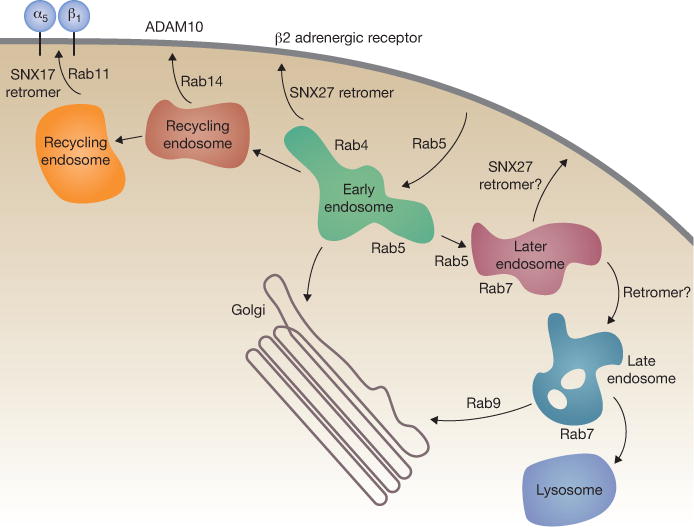

Identification of a large set of cargoes for a single SNX protein can be seen as simplifying the potential complexity of cargo recognition in receptor recycling. However, recent work highlights the gaps in our knowledge regarding the full complexity of the early endocytic pathway. A new Rab14-dependent pathway drives recycling of the ADAM family transmembrane proteases 9 and 10, and this route is distinct from the Rab4-mediated pathway for αVβ3 integrin recycling and Rab11-mediated α5β1 integrin recycling13 (Fig. 1). Which of these ‘early’ endosome events also require retromer constituents? α5 integrin relies on the VPS26–VPS29–VPS35 complex6 and was previously shown to require SNX17 (ref. 10). A paradox is presented by the finding that retromer is recruited to endosomes as they acquire Rab7 protein — a hallmark of the transfer of cargo from early to late endosomes2,9. Receptor recycling events are believed to take place before cargoes reach a Rab7 compartment. Perhaps some retromer can be recruited to SNX27 domains in conjunction with SNX–BAR proteins, at the time of late endosome conversion. Many years ago, Fred Maxfield proposed that simple segregation of cargoes into endosome tubules could be sufficient to explain the process of receptor recycling14. SNX and SNX–BAR proteins are clearly important for such tubule segregation that indeed occurs. It is now critical to decipher how many recycling routes are in play, and how the SNX and retromer subunits link to endosomal Rabs to drive receptor recycling from what seem to be multiple sorting stations to achieve recycling to the correct plasma membrane domain.

Figure 1.

Complexity in endocytic receptor trafficking. Cell surface receptors are internalized in a Rab5-dependent process and delivered to early endosomes. They are then recycled in processes that depend on Rab4, Rab14 and/or Rab11 GTPases14. In this issue, Steinberg et al. reveal the broad role of SNX27 protein in receptor recycling in conjunction with the retromer complex. The β2 adrenergic receptor requires Rab4, SNX27 and retromer constituents5,6. Recycling of α5β1 integrin uses SNX17 and retromer, probably from a Rab11 compartment6,11. Rab7 is required for retromer recruitment on a later endosome compartment9. The complexity of the early endocytic pathway was not anticipated, and how the Rabs work in concert with SNX proteins represents an important area for future work. The roles of Rab21, Rab25 and Rab35 are not shown.

Finally, the importance of SNX27 in rescuing receptors from degradation and enhancing their recycling to the cell surface has been confirmed in mice. Despite normal gross neuroanatomy, heterozygous deletion strains show defective synaptic function and deficits in learning and memory, due to loss of NMDA and AMPA receptors and overall decreased glutamate receptor recycling15. Furthermore, decreased SNX27 expression is seen in Down’s syndrome following the loss of CCAAT-enhancer-binding protein β (C/EBP β), which turns out to be a SNX27 transcription factor. In Down’s syndrome, a chromosome-21-encoded microRNA, miR-155, is overexpressed and negatively regulates C/EBP β and thus SNX27. Altogether, these studies confirm the importance of SNX27, both in Down’s syndrome15 and in non-neuronal cells6, for critical regulation of receptor recycling to the cell surface in normal and disease states.

Footnotes

COMPETING FINANCIAL INTERESTS

The author declares no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Cullen PJ. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:574–582. doi: 10.1038/nrm2427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cullen PJ, Korswagen HC. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;14:29–37. doi: 10.1038/ncb2374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lunn ML, et al. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:1249–1259. doi: 10.1038/nn1953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lauffer BE, et al. J Cell Biol. 2010;190:565–574. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201004060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Temkin P, et al. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:715–721. doi: 10.1038/ncb2252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Steinberg F, et al. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15:461–471. doi: 10.1038/ncb2721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mim C, Unger VM. Trends Biochem Sci. 2012;37:526–533. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2012.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seaman MN. J Cell Biol. 2004;165:111–122. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200312034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seaman MN. J Cell Sci. 2012;125:4693–4702. doi: 10.1242/jcs.103440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Steinberg F, Heesom KJ, Bass MD, Cullen PJ. J Cell Biol. 2012;197:219–230. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201111121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Duncan JR, Kornfeld S. J Cell Biol. 1988;106:617–628. doi: 10.1083/jcb.106.3.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen C, et al. Cell Metab. 2013;17:343–352. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Linford A, et al. Dev Cell. 2012;22:952–966. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dunn KW, McGraw TE, Maxfield FR. J Cell Biol. 1989;109:3303–3314. doi: 10.1083/jcb.109.6.3303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang X, et al. Nat Med. 2013;19:473–480. doi: 10.1038/nm.3117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]