As Liaw et al report in this month’s issue of Annals of Family Medicine, solo and small practices are under pressure from market forces propelling practice consolidation.1 However, more than one-half of all family medicine physicians—and one-half of recent graduates—are still caring for patients in practices with 5 or fewer providers. What does the future hold for these primary care physicians, especially in a world of value-based health care?

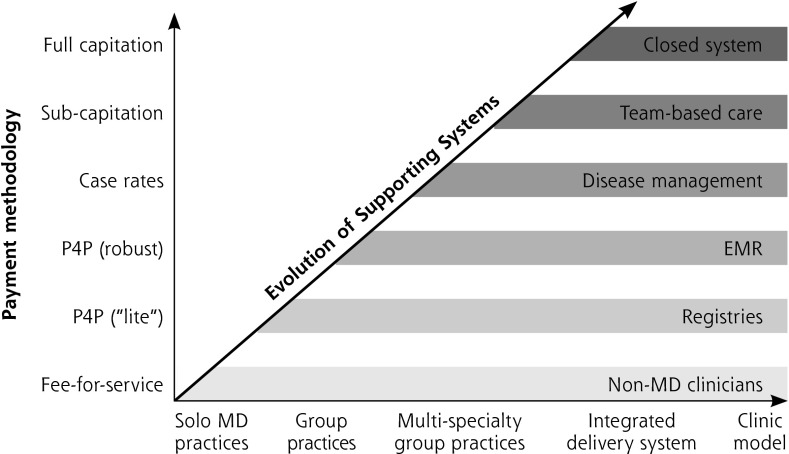

The arguments for consolidation are well known: ease of coordinated care, less duplication of tests and treatment, and decreased costs due in part to economies of scale. Under a consolidation philosophy, provider organizations evolve from solo physician practices; to groups and multispecialty practices; and finally, to fully integrated delivery systems that employ the physicians, own the hospitals, and use a single information system (and sometimes even play the role of health insurance plan).2 In this Darwinian view of health care delivery, “lower” forms of practice organization are assumed to be incapable of implementing the supporting systems needed for population health (eg, registries, electronic medical records, care management, and team-based care) and are therefore unable to compete in value-based payment systems.

Yet, small independent primary care practices are not unevolved primates; evidence instead suggests they are uniquely situated to thrive in delivering value-based care. From 2004 to 2011 hospital ownership of physician practices increased from 24% of practices to 49%.3 This consolidation does not appear to have resulted in lower prices, higher quality, or better care experiences. Instead, hospital ownership of a doctor’s group dramatically increases the probability that patients go to hospitals that employ their doctor, even when those hospitals are lower quality and higher cost.4 The main effect of such consolidation is not true clinical integration, but market power used to extract higher prices from payers5 and to prevent any efficiencies from being passed on to payers and consumers.

Meanwhile, recent evidence suggests that small, physician-owned practices, while providing a greater level of personalization and responsiveness to patient needs, have lower average cost per patient,6 fewer preventable hospital admissions,7 and lower readmission rates than larger, independent- and hospital-owned practices.8

In an era of value-based care, the autonomy of small practices and the preservation of the traditional doctor-patient relationship helps provide important reassurance to the patient that the physician is acting in his or her best interests. This unique bond generates trust which leads to better adherence to a treatment plan.9 Primary care physicians play a quarterback role—making decisions that can control up to 85% of downstream costs. In this context, the importance of a trusted, engaged, and financially aligned primary care physician in a value-based system becomes evident.

As the health care system has accelerated its transition from fee-for-service to outcome-based payment (“from volume to value”), too many family physicians feel they are facing a future where the independent practice of medicine is increasingly untenable. A paradox emerges for independent primary care physicians who, because of their relationships with patients, are uniquely positioned to lead the transition to value-based care and succeed in new payment arrangements; but because of the investment, and the regulatory, technological, and analytic expertise necessary to enter these arrangements, they are also least equipped to do so.

As suggested by Liaw et al, small practices can solve this paradox and thrive in the new health care economy if they band together to “profit from economies of scale without sacrificing the benefits of being small.”1

These practices must link up with others that share a simultaneous dedication to the mission of value-based care, and the value of small practices. This coupling has multiple positive effects. First, it allows the practices a network of peers to learn from and to glean deeper insights from population health models. Second, it provides the scale needed to negotiate value-based contracts and to spread the risk across multiple practices, so that a handful of unavoidable hospitalizations does not destroy a practitioner. Third, a network at scale can procure the necessary technologies and employ individuals who can use analytics to draw actionable insights from data, or have the regulatory and billing know-how to maximize revenue in the right way, while laying the groundwork for future savings. A variety of organizations help physicians to make this transition and share the related expenses across multiple practices: for-hire ACO consultants, government-funded Transforming Clinical Practices Initiatives, payer-sponsored entities, and venture-funded ACO operators.

Figure 1.

Evolving reimbursement and care models.

Health IT extension programs provide hope and a helpful precedent. In an era when stand-alone small practices were thought to be “unwilling and unable to adopt information systems”2 Mat Kendall and I worked in the Office of the National Coordinator (ONC) at the US Department of Health and Human Services to create a model that enabled small practices to successfully implement electronic health records (EHRs).10 The Regional Health IT Extension Center program—a nationwide initiative which helped over 100,000 primary care providers in small practices adopt EHRs,11 and lay the technology-based foundation for success in value-based care.

Since leaving ONC, I’ve spent time discussing these issues with hundreds of small practices around the country. First as a visiting scholar at the Brookings Institute, and currently as CEO of Aledade, a start-up company that partners with independent primary care physicians to provide what they need to enter into and succeed in value-based care arrangements. Given the right supports, independent primary care physicians are eager to participate in ACOs and other value-based arrangements. They have the ability to be effective at rapidly implementing practice transformation initiatives, yet they are navigating new and often choppy waters. To help them thrive in value-based care, we need federal policies that will support competition and patient choice. These include:

Primary care rates should be set to parity with those paid to organized systems, reducing the financial incentives for independent primary care practices to join hospital systems.12 This incentive structure ignores the unique benefits small practices bring to the health care system and underestimates the power of their relationships with patients; and is counterproductive for patients and payers alike.

The federal government and payers should avoid undue regulatory burdens on providers and offer administrative relief for small practices. Limiting the number of process measures reported and following the lead of CMS in permitting quality intermediaries to conduct the reporting of quality measures could alleviate burdens.

The Federal Trade Commission should investigate complaints regarding limiting hospital admitting privileges, restricting care by hospital employees, and vendors and health systems using their market power to force independent physicians away from true market choice. The Department of Justice must continue to emphasize investigating cases of fraud, such as parties “overpaying” physicians (ie, those hiring at a loss) in order to obtain referrals.13

CMS should discourage “ACO squatting” by requiring hospital-owned ACOs with capital reserves to switch to 2-sided risk models after an initial 3-year contract period, while allowing flexibility for physician-led ACOs.

This is an exciting time for the future of health care. But central to the promise of that future is preserving small, independent primary care physicians which comprise about one-half of all family medicine physicians. These providers are close to the community, engaged in the lives of their patients, and have earned the trust needed to change patient behavior that includes patient ownership of his or her own health. Now that the financial systems exist for this type of medicine to be rewarded, we need to facilitate the partnerships, technologies, and policies necessary for independent practices to thrive. This is necessary not just for the future of these practices, but for the sustainable future of a value-based health care system that serves all patients.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks the independent primary care physicians in Aledade ACOs in 11 states who inspire and educate us every day.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: Dr Mostashari is CEO of Aledade, Inc, a for-profit, start-up company that partners with independent, primary care physicians to create and run accountable care organizations (ACOs), and enter into value-based contract arrangements with payers.

References

- 1.Liaw WR, Jetty A, Petterson S, Peterson LE, Bazemore A. Solo and small practices: a vital, diverse part of primary care. Ann Fam Med. 2016;14(1):8–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee TH, Berenson RA. The organization of health care delivery: a roadmap for accelerated improvement. In: The Health Care Delivery System: A Blueprint for Reform. Washington, DC: The Center for American Progress; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cutler DM, Scott Morton F. Hospitals, market share, and consolidation. JAMA. 2013;310(18):1964–1970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baker LC, Bundorf MK, Kessler DP. The effect of hospital/physician integration on hospital choice. NBER Working Paper No. 21497. http://www.nber.org/papers/w21497 August 2015.

- 5.Gaynor M, Town R. The impact of hospital consolidation – update. http://www.rwjf.org/en/library/research/2012/06/the-impact-of-hospital-consolidation.html June 2012.

- 6.Robinson JC, Miller KM. Total expenditures per patient in hospital-owned and physician-owned physician organizations in California. JAMA. 2014;312(16):1663–1669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Casalino LP, Pesko MF, Ryan AM, Mendelsohn JL, Copeland KR, Ramsay PP, et al. Small primary care physician practices have low rates of preventable hospital admissions. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014:33(9):1680–1688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McWilliams J, et al. Delivery system integration and health care spending and quality for medicare beneficiaries. JAMA. 2013;173(15):1447–1456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Piette JD, Heisler M, Krein S, Kerr EA. The role of patient-physician trust in moderating medication nonadherence due to cost pressures. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(15):1749–1755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mostashari F, Tripathi M, Kendall M. A tale of two large community electronic health record extension projects. Health Aff (Millwood). 2009;28(2):345–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lynch K, Kendall M, Shanks K, et al. The Health IT Regional Extension Center Program: evolution and lessons for health care transformation. Health Serv Res. 2014;49(1 Pt 2):421–437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miller ME. Medicare Payment Advisory Committee (MedPac). Medicare fee-for-service payment policy across sites of care. Statement before the Subcommittee on Health Committee on Energy and Commerce US House of Representatives May 21, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 13.US Department of Justice. Office of Public Affairs. Adventist Health System agrees to pay $115 million to settle False Claims Act allegations. Justice News. September 21, 2015. http://1.usa.gov/1RmTu2t.