Thalidomide and lenalidomide have been tested for treatment of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma. Of 25 patients, 7 (28%) experienced delayed-onset responses without further treatment. Late-onset remissions might be a common phenomenon in the use of immunomodulatory drugs for the treatment of MALT lymphoma. Thus, sufficient follow-up time after treatment before the initiation of further therapy appears crucial to assess the full effect of therapy and avoid unnecessary overtreatment.

Keywords: Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma, Immunomodulatory drugs, Lenalidomide, Thalidomide, Extranodal lymphoma

Abstract

Background.

The immunomodulatory drugs (IMiDs) thalidomide and lenalidomide have both been tested for treatment of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma, with lenalidomide, in particular, showing promising activity. However, long-term results are missing. Because of the late-onset remissions registered in individual patients, we have systemically analyzed the patients treated with IMiDs at our institution for long-term results.

Methods.

Within the present retrospective analysis, we identified 25 patients who had been treated with lenalidomide (n = 18) or thalidomide (n = 7) and were available for long-term assessments of outcome. All patients were followed up according to a standardized follow-up protocol.

Results.

Of the 25 patients, 7 (28%) experienced delayed-onset responses without further treatment (thalidomide, n = 2; lenalidomide, n = 5). In 4 patients (16%), the initial outcome switched to a better result (partial remission [PR] to complete remission [CR], n = 1; stable disease [SD] to PR, n = 1; SD to CR, n = 1; and PD to CR, n = 1) after a median time of 19.5 months (range, 10.9–32.0). Furthermore, 2 patients showed ongoing shrinkage of the target lesion for 47.4+ and 43.5+ months, respectively, and 1 patient had durable disease stabilization for 16.2+ months. The median time to the best response for all responding patients (13 of 25; 53%) was 7.3 months (interquartile range [IQR], 5.6–22.5). After a median follow-up of 46 months (IQR, 32.0–58.5), 23 of 25 patients (92%) were alive.

Conclusion.

Our findings suggest that late-onset remissions might be a common phenomenon in the use of IMiDs for the treatment of MALT lymphoma. Thus, sufficient follow-up time after treatment before the initiation of further therapy appears crucial to assess the full effect of therapy and avoid unnecessary overtreatment.

Implications for Practice:

The immunomodulatory drugs (IMiDs) thalidomide and lenalidomide have been tested for the treatment of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma, with lenalidomide showing promising activity. However, long-term results are missing. The present findings suggest that late-onset remissions and delayed responses could be a common phenomenon with IMiD use for MALT lymphoma. Using a standardized restaging protocol to ensure concise follow-up data, these findings suggest it is of major importance to ensure a sufficient follow-up time after treatment with these compounds and before initiation of further treatment lines, because nearly one third of treated patients showed further improvement during prolonged follow-up.

Introduction

Owing to the growing awareness of the dissemination and recurrence potential of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma, systemic treatment has been increasingly used for Helicobacter pylori (HP)-eradication refractory, extragastric, or advanced MALT lymphoma [1]. The immunomodulatory drugs (IMiDs) thalidomide and lenalidomide have both been tested for the treatment of MALT lymphoma, with lenalidomide, in particular, showing promising activity [2, 3]. However, during prolonged follow-up, unexpected late remissions and improvement of residual disease were registered in our patients, prompting us to systematically analyze long-term outcome of patients treated with IMiDs for MALT lymphoma.

Methods

A retrospective analysis of all patients with MALT lymphoma diagnosed and treated with IMiDs at our institution was performed. All patients had been included in two phase II studies approved by the local ethical board and previously published [2, 3]. All our patients were followed up on a regular basis according to a standardized procedure after the end of treatment (every 3 months for 2 years, every 6 months for 2 more years, and annually thereafter). Thus, we have been able to provide profound follow-up data with excellent adherence to the scheduled evaluations for all patients.

Results

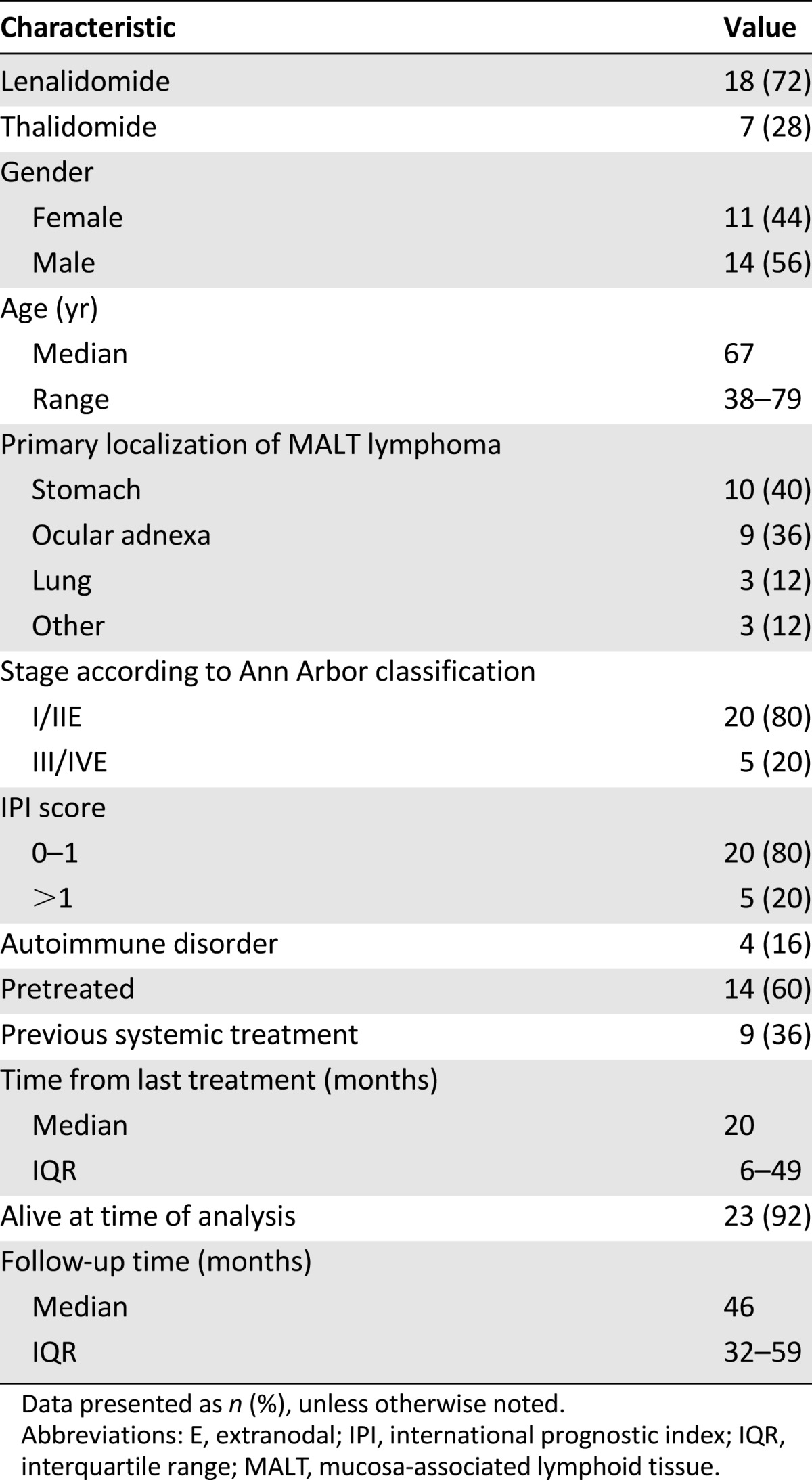

A total of 25 patients treated with IMiDs were identified (11 females and 14 males; median age, 67 years). The initial lymphoma localization was the stomach in 40%, and 60% had extragastric lymphoma. Of the 25 patients, 60% had been pretreated, including 9 patients who had received (immuno-)chemotherapy, with the median time from the last therapy 20.4 months (interquartile range [IQR], 6.4–49.0). The me-dian time to IMiD treatment from diagnosis was 9.8 months (IQR, 1.4–58.7). The baseline characteristics are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Main patient characteristics

Of the 25 patients, 7 (28%) had received thalidomide and 18 (72%) lenalidomide. For further details on the treatment protocols, the published trial results are available in [2, 3].

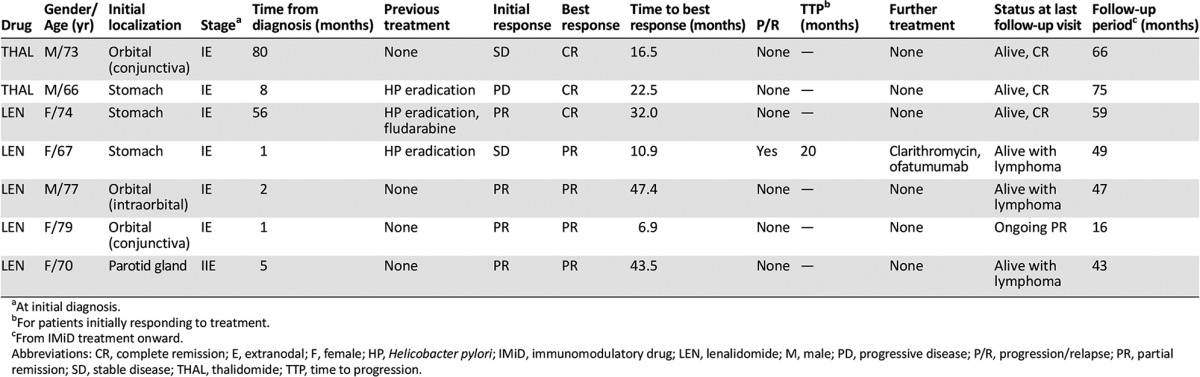

Thalidomide was started at 100 mg daily and increased up to 400 mg in patients without significant toxicities for six 4-week cycles [2]. Although initially, we had thought to include 16 patients, the study was closed prematurely owing to insufficient efficacy at an interim analysis of 8 patients. No patient had responded during the study at a median follow-up period of 19 months (4 with stable disease [SD] and 4 with progressive disease [PD]). However, during the follow-up period, 2 patients initially rated as having SD and PD, respectively, had improved further without additional therapy. In the first patient, a previously untreated 73-year-old man with orbital MALT lymphoma, SD was assessed after 6 months of treatment with thalidomide. The subsequent regular follow-up examinations revealed constant shrinkage, resulting in complete remission (CR) 16.5 months after treatment start. This patient was in ongoing CR for 49.5+ months at the last follow-up visit. The second patient, a 66-year-old man with gastric lymphoma refractory to HP eradication, had experienced focal progression revealed by endosonography and histologic examination during thalidomide treatment and was removed from the study after 23 weeks. However, the next restaging examination revealed only probably minimal residual disease according to the Groupe d' Etude des Lymphomes de l' Adulte (GELA) criteria [4], with additional follow-up examinations disclosing CR 22.5 months after the initiation of therapy. This patient has remained in CR after 75.4+ months.

Lenalidomide was tested at a daily dose of 25 mg for 21 days for a maximum of 6 cycles [3]. A total of 18 patients were included; however, 2 patients quit treatment during the first cycle for personal reasons. The response rate in the intent-to-treat analysis was 61% (six CRs and five partial remissions [PRs]). During the initial follow-up time of 20.3 months, 1 patient died of lymphoma, and the remaining patients were free of relapse. However, also in this collective, late remissions and improvements were observed. One patient with HP-negative gastric MALT lymphoma had responding residual disease (rRD) after six cycles, which had improved to a CR 32 months after treatment start and was in ongoing CR (28+ months) at the last follow-up examination. Another patient with gastric lymphoma had SD after cycle six and had improved to rRD 10.9 months after treatment start. In addition, 2 patients had PR at the end of treatment, and follow-up examinations revealed further shrinkage for 47.4+ and 43.5+ months. Finally, 1 patient had SD for 16.0+ months.

Taken together, 28% had experienced delayed-onset benefit, including 4 patients (16%) in whom the initial outcome had improved to a better result using the RECIST/GELA criteria after a median of 19.5 months (range, 10.9–32.0; Table 2). An additional 2 patients showed ongoing shrinkage of the target lesion for 47.4+ and 43.5+ months, and 1 had durable stabilization for 16+ months at the last follow-up visit. The median time to the best response (TTR) for the 13 responding patients (52%) was 7.3 months (IQR, 5.6–22.5). Ten patients (40%) required further treatment, including 4 of the 13 responding patients (31%). Also, 6 of the 13 initial responders (52%) had developed progression after a median of 19.2 months (range, 2.5–22.5).

Table 2.

Characteristics of MALT lymphoma patients experiencing delayed benefit of IMiD treatment

At the last follow-up visit, 14 of the 25 patients (56%) were alive with an ongoing CR or CR after salvage treatment. Also, 7 (28%) were alive with lymphoma, 2 had died (1 patient of lymphoma progression), and 2 patients were lost to follow-up. The median survival point had not been reached at a follow-up time of 46 months (IQR, 32.0–58.5),

Discussion

In the present analysis, we report our experience with long-term follow-up of patients treated with IMiDs, suggesting that late remissions might be a common phenomenon during prolonged observation. The standardized follow-up protocol revealed a delayed-onset benefit for 28% of patients, with 16% improving to a better response after a median of 19.5 months. In analogy to HP eradication, for which follow-up periods of at least 1 year after eradication are recommended [5–7], these findings suggest that prolonged follow-up periods might be necessary to assess the full effect of this treatment. The ability to induce late remissions after the end of actual treatment with IMiDs appears to be unique for MALT lymphoma, because in other indications, lenalidomide achieved much more rapid responses. In patients with myelodysplastic syndrome and 5q31 deletion, the median TTR was documented after 4.6 weeks (range, 1–49) [8]. In refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia, antileukemic effects were observed as early as 7 days of treatment [9]. Data evaluating lenalidomide for refractory mantle cell lymphoma showed that responding patients reacted rapidly, with a median TTR of 2.2 months [10].

Although we cannot offer a definite explanation for our results, we believe that our findings add crucial clinical information to the treatment of refractory/relapsed MALT lymphoma with IMiDs. We suggest that it is of major importance to ensure sufficient follow-up time after treatment with these compounds and before initiation of further treatment lines, because nearly one third of treated patients showed further improvement during prolonged follow-up.

Footnotes

For Further Reading:Barbara Kiesewetter, Andrés J.M. Ferreri, Markus Raderer. Chemoimmunotherapy for Mucosa-Associated Lymphoid Tissue-Type Lymphoma: A Review of the Literature. The Oncologist 2015;20:915–925.

Implications for Practice:In view of the biology of MALT lymphoma with trafficking of cells within various mucosal structures, systemic treatment strategies are increasingly being used not only in advanced but also localized MALT lymphoma. In the past, different chemotherapeutic agents, including anthracyclines, alkylators, and purine analogs, have been tested successfully. However, modern regimens concentrate on reducing side effects because of the indolent nature of this distinct disease. As outlined in this review and based on recent data, chlorambucil plus rituximab (R) may be considered one standard treatment within this setting. In addition, R-bendamustine seems to be a very promising combination. According to recent trends, however, “chemo-free” approaches (i.e., antibiotics with immunomodulatory effects [clarithromycin]) or other immunotherapies (lenalidomide ±R) may be important therapeutic approaches in the near future.

Author Contributions

Conception/design: Barbara Kiesewetter, Markus Raderer

Provision of study material or patients: Barbara Kiesewetter, Marlene Troch, Marius E. Mayerhoefer, Werner Dolak, Ingrid Simonitsch-Klupp, Markus Raderer

Collection and/or assembly of data: Barbara Kiesewetter, Marlene Troch, Marius E. Mayerhoefer, Werner Dolak, Ingrid Simonitsch-Klupp, Markus Raderer

Data analysis and interpretation: Barbara Kiesewetter, Marlene Troch, Marius E. Mayerhoefer, Werner Dolak, Ingrid Simonitsch-Klupp, Markus Raderer

Manuscript writing: Barbara Kiesewetter, Marius E. Mayerhoefer, Markus Raderer

Final approval of manuscript: Barbara Kiesewetter, Marlene Troch, Marius E. Mayerhoefer, Werner Dolak, Ingrid Simonitsch-Klupp, Markus Raderer

Disclosures

Markus Raderer: Gilead, Roche, Janssen, Novartis, Eisai, Ipsen (C/A). The other authors indicated no financial relationships.

(C/A) Consulting/advisory relationship; (RF) Research funding; (E) Employment; (ET) Expert testimony; (H) Honoraria received; (OI) Ownership interests; (IP) Intellectual property rights/inventor/patent holder; (SAB) Scientific advisory board

References

- 1.Kiesewetter B, Ferreri AJ, Raderer M. Chemoimmunotherapy for mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue-type lymphoma: A review of the literature. The Oncologist. 2015;20:915–925. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2015-0109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Troch M, Zielinski C, Raderer M. Absence of efficacy of thalidomide monotherapy in patients with extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of the mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT lymphoma) Ann Oncol. 2009;20:1446–1447. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kiesewetter B, Troch M, Dolak W, et al. A phase II study of lenalidomide in patients with extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of the mucosa associated lymphoid tissue (MALT lymphoma) Haematologica. 2013;98:353–356. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2012.065995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Copie-Bergman C, Wotherspoon AC, Capella C, et al. GELA histological scoring system for post-treatment biopsies of patients with gastric MALT lymphoma is feasible and reliable in routine practice. Br J Haematol. 2013;160:47–52. doi: 10.1111/bjh.12078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fischbach W, Goebeler ME, Ruskone-Fourmestraux A, et al. Most patients with minimal histological residuals of gastric MALT lymphoma after successful eradication of Helicobacter pylori can be managed safely by a watch and wait strategy: Experience from a large international series. Gut. 2007;56:1685–1687. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.096420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ruskoné-Fourmestraux A, Fischbach W, Aleman BMP, et al. EGILS consensus report: Gastric extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of MALT. Gut. 2011;60:747–758. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.224949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dreyling M, Thieblemont C, Gallamini A, et al. ESMO consensus conferences: Guidelines on malignant lymphoma. Part 2: Marginal zone lymphoma, mantle cell lymphoma, peripheral T-cell lymphoma. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:857–877. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.List A, Dewald G, Bennett J, et al. Lenalidomide in the myelodysplastic syndrome with chromosome 5q deletion. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1456–1465. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chanan-Khan A, Miller KC, Musial L, et al. Clinical efficacy of lenalidomide in patients with relapsed or refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia: Results of a phase II study. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:5343–5349. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.0401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goy A, Sinha R, Williams ME, et al. Single-agent lenalidomide in patients with mantle-cell lymphoma who relapsed or progressed after or were refractory to bortezomib: Phase II MCL-001 (EMERGE) study. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3688–3695. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.49.2835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]