SUMMARY

Inadequate management of pain in early human life contributes to impaired neurodevelopmental outcome and alters pain thresholds, pain or stress-related behavior and physiological responses. However, there are also emerging animal experimental data on the impact of exposure to analgo-sedatives on the incidence and extent of neuro-apoptosis. Since this association has also been suggested in humans, the pharmacological treatment of neonatal pain is in search of a new equipoise since these ‘conflicting’ observations are the main drivers to further reconsider our current treatment regimens. This review focuses on new data concerning clinical pharmacology of morphine, followed by data on more recently introduced opioids like remifentanil and tramadol, locoregional anesthesia and minimally invasive techniques in neonates, and finally with data on intravenous paracetamol. Since the available data are still incomplete, priorities for both clinical management and future research will be proposed.

Keywords: Loco-regional anesthesia, Morphine, Neuro-apoptosis, Newborn, Pain, Paracetamol

1. Introduction

The myth that the immaturity of the nervous system precludes neonates from pain perception and its negative effects has been rejected by the pivotal observations of Anand et al.1 Consequently, effective management of pain became an important indicator of the quality of care provided to neonates. Early pain experiences contribute to impaired neurodevelopmental outcome and alter pain thresholds, pain or stress-related behavior, and physiological responses.2–8

The latest review in this journal on the pharmacological treatment of pain by Tibboel et al.2 focused on opioids with emphasis on morphine clearance and on short-term outcome data of morphine in ventilated preterm neonates. Since this review, the field of neonatal pain has evolved. Additional data on the pharmacokinetics and -dynamics of morphine have been published. Clinical observations on new treatment modalities, including synthetic opioids, non-opioids and loco-regional techniques have been introduced in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). Most importantly, new concepts on the association of exposure to pain, analgo-sedatives and neuro-apoptosis have emerged.9–12

The ontogeny of the nervous system is based on a complex pattern of cell proliferation, migration, differentiation and selective cell survival and includes apoptosis. Functional development relates to a balance of excitatory and inhibitory signals. Due to maturational plasticity of the nociceptive systems throughout infancy, nociceptive input may cause population-specific lasting alterations in pain processing.9–12 Similarly, exposure of nociceptive and non-nociceptive nervous circuits to analgo-sedatives also modulates receptor-signaling-related brain development. Experimental data from animals provide evidence that chronic morphine exposure in perinatal life results in reduced brain volume, decreased neuronal packing density and less dendritic growth and branching. This is associated with learning and motor disabilities. By contrast, opioid receptor blockade through naloxone results in increased brain size and more pronounced dendritic arborization. Similar animal experimental data have been reported for other analgo-sedatives, including benzodiaze-pines, ketamine, inhalational anesthetics, propofol and barbiturates or combinations of such analgo-sedatives. Alterations are in part drug and dose dependent, and there is an age-related window of vulnerability for apoptosis on the one hand or dendritic changes on the other hand.9–12

The extrapolation of these observations in animals to the human (pre)term newborn is obviously hampered by several limitations. Some authors report on an association between major neonatal surgery (number of interventions, disease severity) and neuro-developmental impairment. However, exposure to analgo-sedatives is only one of the factors associated with this negative outcome.9–12 Others have extended these long-term impact research concepts to include medical-procedure-related pain and nociception in later life in preterm neonates.13,14 Using functional magnetic resonance imaging during a tonic heat stimulus, the cerebral pain response in three sets (NICU preterm, NICU full term, no NICU admission) of nine children each were compared.13 Former preterms had significantly higher activations than controls in primary somatosensory cortex, anterior cingulate cortex, and insula. This exaggerated brain response was pain-specific since this was not observed during non-painful warmth stimulation.13 Similarly, and using a term matched–control design in 43 former extreme preterm neonates, Walker et al.14 documented that there were differences in somatosensory perception in childhood. These differences were in part local (e.g. thermal and mechanical hypo-sensitivity around a thoracotomy scar), in part more general (thermal hyposensitivity).14

In our opinion, these observations are the main drivers to further reconsider our current treatment regimens. In this review, we focus on new data concerning the clinical pharmacology of morphine, followed by data on more recently introduced opioids, loco-regional anesthesia and minimally invasive techniques in neonates and to finish with data on intravenous paracetamol.

2. Clinical pharmacology of morphine in neonates: friend and foe?

2.1. Pharmacokinetics

The predictability of morphine disposition in neonates has been further documented. Model-based simulations showed that in (preterm) newborns, a loading dose (μg/kg) and maintenance dose expressed in (μg/kg1.5/h) with a 50% reduction in newborns aged <10 days resulted in a narrow range of morphine and metabolite serum concentrations.15 The predictive performance of this population pharmacokinetic model was subsequently evaluated based on six external datasets of observations of morphine and its metabolites in neonates and infants.16

However, pharmacodynamic investigations are still needed to document target concentrations in neonates based on in-vitro trial design to estimate effect compartment concentrations, and proof of principles trials in the particular age groups. At present, we can fairly well predict morphine concentrations,15,16 but we do not yet know the target concentration to aim for. Obviously, final dosing recommendations can only be made once both types of information are available.

2.2. Pharmacodynamics

Tibboel et al.2 reported that pre-emptive morphine administration in ventilated preterm neonates did not result in improved short-term outcome. The same group recently reported on long-term neurodevelopmental outcome in their cohort of former preterm neonates at the age of 5 years. The statistically significant lower overall intelligence quotient (IQ) score in children (difference in mean values: 6 points) exposed to morphine disappeared after correction in a multiple regression model.17 However, scores of one specific IQ subtest (visual analysis) remained significantly negatively related to having received morphine and to open-label morphine consumption. A further follow-up evaluation at 8 years of age has confirmed these 5-year findings (D. Tibboel et al., unpublished data). These data provide evidence for lasting effects following pre-emptive morphine administration and are further supported by the pilot outcome data of the NEOPAIN study.17,18 Although based on a limited number of cases, there was a difference in head circumference, body weight and choice latency in the pre-emptive morphine group of the NEOPAIN cohort at the age of 5–7 years.18

3. Newer opioids in neonates: new is better?

Taking into account the shift towards less invasive neonatal care (e.g. prolonged mechanical ventilation compared with respiratory support), short-acting (e.g. remifentanil)17–24 or less potent (e.g. tramadol)25–27 analgesics were introduced.

3.1. Remifentanil

Remifentanil undergoes metabolic clearance by plasma esterases, resulting in predictable clearance irrespective of liver or renal dysfunction, whereas esterase activity is already fairly mature at birth.19,20 This compound has mainly been used for short procedures such as endotracheal intubation,21 laser surgery for retinopathy of prematurity (ROP)22 or for insertion of a percutaneous intravenous central catheter.24 However, similar to the morphine example earlier discussed, pharmacokinetics are predictable, but caregivers have to be aware that there are pharmacodynamic effects (in part compound-specific) that deserve special attention.

The analgo-sedative effects disappear very soon after discontinuation of remifentanil since the drug is cleared very rapidly.19,20 This is perfect or optimal when used for procedural analgo-sedation without subsequent pain. However, when used for major surgery, anticipation and replacement by another (longer-acting) opioid or non-opioid analgesic is needed, or the remifentanil infusion should be prolonged.24 However, further continuation will more likely result in potentially negative effects such as opioid-induced tolerance or hyperalgesia since these phenomena are much more common when opioids with a short elimination half-life are administered.19,20

3.2. Tramadol

Phenotypic variation in drug concentrations is based on constitutional, environmental and genetic factors. In early life, it mainly reflects ontogeny, i.e. age-dependent phenotypic activity.28 This is also true for cytochrome P450 (CYP) 2D6 activity, of relevance for tramadol pharmacokinetics and -dynamics.25–27

Tramadol is a 4-phenyl piperidine analogue of codeine. Its analgesic effect is mediated through noradrenaline re-uptake inhibition, increased serotonin release and decreased serotonin re-uptake in the spinal cord. Tramadol also has a weak μ-opioid receptor effect. Tramadol (M) is metabolized by O-demethylation (CYP2D6) to the pharmacodynamic (μ-opioid-receptor-mediated) active metabolite O-demethyl tramadol (M1). This metabolite is subsequently eliminated by renal route whereas M1 formation depends on ontogeny and CYP2D6 polymorphisms.25,26

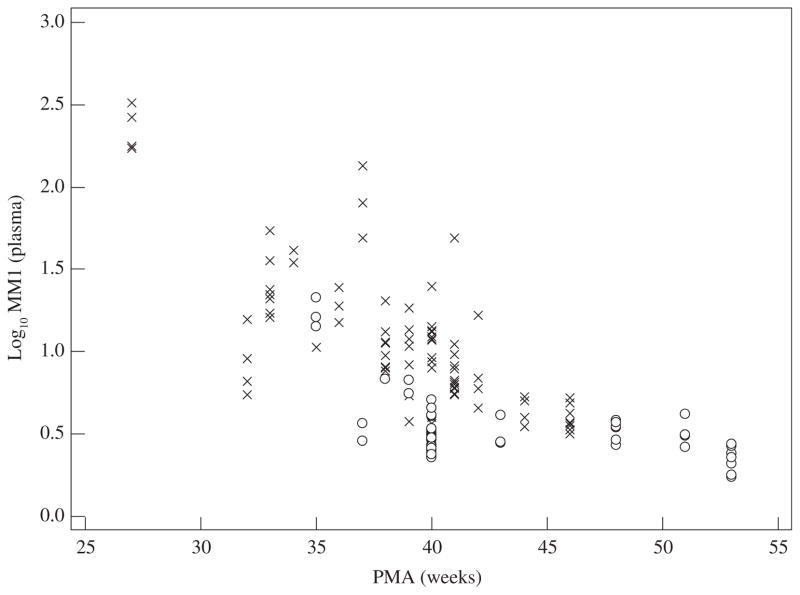

Both postmenstrual age (‘ontogeny’) and CYP2D6 activity score (polymorphism) were independent covariates of the interindividual variability in log10 M1/M values (Figure 1).25 With increasing postmenstrual age, the contribution of the CYP2D6 activity score becomes more relevant. However, we have to be aware that the phenotypic M1 concentration not only reflects tramadol metabolic clearance (M1 synthesis), but also M1 (renal) elimination clearance.26 Since renal elimination clearance matures more slowly compared with M1 metabolic clearance, M1 accumulation is observed in (near) term neonates with clinically appropriate (analgesia) M1 concentrations in plasma, despite an overall phenotypic low age-dependent CYP2D6 activity.25,26,28

Figure 1.

Plasma log10 values of tramadol (M) on O-demethyl tramadol (M1) (log10 M/M1) reflect CYP2D6 activity in early life. The lower the log10 value, the higher the metabolite concentration (i.c. M1). The phenotypic plasma log value (log10 M/M1) depends on both postmenstrual age (PMA) as well as on the CYP2D6 activity score (either CYP2D6 activity score <2, ×; or ≥2, ○).26

As with morphine, extrapolation of concentrations to effects needs a validated target concentration. In neonates, taking the non-μ-opioid-receptor-mediated effects into account, it should be borne in mind that the serotoninergic pathways are anatomically present but functionally immature. As a consequence, tramadol might be less advantageous over other opioids in this population. Further pharmacodynamic studies are needed to evaluate the mono-aminergic analgesic effect of the parent compound in neonates. At present, we are only aware of one randomized controlled trial (fentanyl, 1–2/kg/h versus tramadol, 0.1–0.2 mg/kg/h) in postoperative (mainly abdominal surgery) neonates.27 Based on a prospective study in 160 neonates, similar effectiveness (pain scores) was documented without any differences in time until spontaneous breathing, nor in time to reach full enteral feeding.

4. Locoregional anesthesia and minimally invasive techniques: less is more?

4.1. Locoregional anesthesia

Invasive surgery induces tissue inflammation and a more generalized activation of systemic metabolic and hormonal pathways by neural pathways. Locoregional blocks allow blockage of neural pathways with limited systemic exposure to result in suppression of pain, hemodynamic alterations and stress responses. Consequently, these techniques hold promise to reduce the total amounts of analgesics needed, also in neonates.29 Regional anesthesia in children has reached widespread use. Although some techniques are indeed routinely used in clinical care, we would like to make the point that these interventions also have to undergo prospective studies in neonates, also taking into account significant learning curves and team performance as essential for the appropriate conduction of these trials.30–34

To illustrate the relevance of such studies, we refer to some recently reported observations. First, local wound infiltration with bupivacaine in neonates had no effect on pain relief or fentanyl requirements following laparotomy.30 This may in part relate to the fact that hetero-assessment of pain is needed.31 In addition, opioid dosing is not always aimed to provide analgesia only, but may also aim to suppress hemodynamic responses to stimuli or even at rest.31 Similarly, there are some case series on transversus abdominis plane blocks in neonates and infants.32,33 As both research groups also mentioned, this technique only provides analgesia for the abdominal wall. Consequently, visceral manipulation is not covered by this technique, and more potent systemic analgesics are needed, including opioids. Finally, local anesthetic eye-drops before screening for ROP were ineffective to blunt the clinical pain and stress response. This is very likely due to the fact that speculum insertion induces pain and stress responses related to conjunctival manipulation, and that these are not limited to the cornea.34

4.2. Minimally invasive techniques

Pain prevention by adaptations of the technique is an obvious step to improve pain management.5–8 Venous puncture instead of heel lancing is the method of choice for blood sampling in neonates and the use of a sweet-tasting solution further reduces pain expression, not necessary reflecting nocieption.35,36 ROP screening is tolerated better when a Fabry lens is used instead of scleral indentation.37 Laser surgery for ROP is associated with a blunted inflammatory response and a reduced need for postoperative analgesics.37 Closed endotracheal suction results in a reduced stress response when compared with disconnection.37

Similar concepts of less invasive surgery have been introduced, but the number of observations with specific emphasis on postoperative pain in neonates is limited. Minimally invasive surgery does not always result in improved pain control with the need for fewer analgesic agents. Lemoine et al.38 evaluated the differences in postoperative pain between infants who underwent either open or laparoscopic pyloromyotomy and they were unable to document relevant differences. With the use of a case–control design, Ceelie et al.39 also documented that minimal access surgery for repair of esophageal atresia or congenital diaphragmatic hernia was not associated with fewer cumulative opioid doses following surgery. There are ongoing studies that combine intraoperative near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) and stress hormone levels comparing open versus minimal access surgery for repair of major congenital anomalies in newborns. These studies may determine the most appropriate technique (open versus minimal access). Similar to the loco-regional techniques, we have to be aware that learning curves exist.39

5. Intravenous paracetamol: alternative to opioids?

Paracetamol is commonly prescribed to treat moderate pain in neonates and infants. An intravenous formulation may reduce variability related to absorption, and may be considered when enteral routes are not available.40 Aspects of pharmacokinetics and -dynamics of intravenous paracetamol in (pre)term neonates have been reported.40–43

Based on a pooled population pharmacokinetic analysis in 943 paracetamol observations from 158 neonates, pharmacokinetic estimates (between-subject variability, %) were central distribution volume 51.9 l/70 kg (21.6%), peripheral distribution volume 22.7 l/70 kg and clearance 5 l/h/70 kg (40%). Covariate information predicted about 61% of paracetamol clearance variability. Weight (allometric, kg0.75) was the most important covariate of clearance. Clearance increased only marginally with postmenstrual age (0.138 l/kg/h at 28 weeks to 0.167 l/kg/h at 44 weeks) and contributed only 2.2% of variance.40

When considering pharmacodynamics, we reported on short-term safety and tolerance in (pre)term neonates. First, there were no signs of hepatic intolerance during and following repeated administration of intravenous paracetamol.41 Second, as part of the PARANEO study (www.clinicaltrials.gov, NCT00969176), we reported on the hemodynamics following intravenous paracetamol (loading dose, 20 mg/kg) administration. By contrast with the negative hemodynamic effects in adult intensive care unit (ICU) patients, there were no hemodynamic alterations in neonates.42 Similarly, neonates remained normothermic, whereas temperature reduction – most pronounced within the first 2 h after administration – was observed in neonates with fever.43

Although there are some data on the pharmacokinetics and -dynamics in (pre)term neonates, there are still issues to consider.44 First, the number of pharmacokinetic observations in extreme preterm neonates is still (too) limited regarding the optimal loading dose and the maintenance dosing. Second, dosing suggestions are without any validated pharmacodynamic correlate since the applicability of any paracetamol target concentration in neonates remains to be documented.44

In addition, epidemiological data suggest a link between perinatal paracetamol exposure and the risk of developing asthma, whereas the introduction of the intravenous paracetamol formulation resulted in dosage errors (10-fold error) with serious adverse events in individual cases.45,46 Epidemiological findings prompt us to collect long-term outcome data not limited to neuro-developmental outcome, whereas the dose errors reaffirm the risks associated with the introduction of a new compound in this specific population.45,46

6. Clinical practice and research directions: in search of a new equipoise

Effective pain management remains an important indicator of the quality of care provided to neonates, but observations on neuro-apoptosis and integration of newer techniques and compounds prompt caregivers to reconsider the clinical and research aspects of ‘effective’ pain management.

First, adequate pain management is not an isolated activity, but an integrated part of developmental care.4–8 Behavior in former preterm infants was associated with the level of both developmental care [‘infant-centered care index’ (ICC), parents’ involvement in the care of their infant, and developmental-oriented care interventions] and pain management [‘infant pain management index’ (IPM), approach to and procedures used for reducing infant pain]. A higher ICC was associated with higher scores for attention and regulation, less excitability and low stress scores, whereas higher IPM scores were associated with higher attention, higher arousal and lower lethargy.47 The association between both suggests that the combination of both practices (ICC and IPM) supports better neuro-behavioral stability.47 In our opinion, non-pharmacological methods for analgesia in collaboration with different caregivers, including the parents, are the link between pharmacological analgesia and developmental-oriented care interventions.35,47

Second, the introduction of analgo-sedatives and techniques also resulted in new clinical syndromes such as opioid-induced tolerance, neonatal drug withdrawal syndrome,48 hyperalgesia49 or complications such as drug related toxicities46,50 or toxicity due to loco-regional techniques.29 Ten-fold dosing errors with intravenous paracetamol46 and propofol infusion syndrome50 were reported and a case of hyperalgesia49 following opioid exposure in a newborn has been published. Caregivers should be aware of contemporary management of the above-mentioned complications. We refer to the recently published guideline on neonatal drug withdrawal.48

In the clinical setting, a structured approach is needed. Although emerging information indicates that there is a difference between pain expression and nociception,36 this structured approach should start with the routine use of a validated pain-assessment score for the given age-group.31,35 This should be followed by a condition-specific pain management protocol with a limited number of compounds (‘tool box’) for which caregivers are aware of the (side)-effects and thus which is the most appropriate approach.5–8 Moreover, such a pain management protocol should also focus on the titration of analgesics, including a decision tree on when and how to increase and decrease exposure to analgesics.

Finally, further studies are needed. In line with the recently published paper on pediatric analgesic clinical trial design,3 we suggest that this research agenda covers (i) the development and validation of more sophisticated pain assessment tools integrating neurobiological evaluation, (ii) the collection of long-term outcome data after neonatal exposure to analgo-sedatives (pharmaco-vigilance), and (iii) the use of an appropriate study design for neonatal pain studies.

Pain assessment tools based on pain expression reach a level of intersubjectivity based on similar intersubject quantification of pain behavior, not necessary reflecting nociception.36 Multimodal pain measurement based on integration of surface electromyography (EMG), electroencephalography (EEG) or near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS), autonomic responses (heart rate, oxygen saturation, respiratory rate, cardiovascular activity) with electrocardiography (ECG) and pulse oximetry has been advocated. Such tools have the potential to overcome the current design problem with the assessment of pain behavior.51,52

However, we suggest extensive validation of such techniques. Real-time evaluation of the sympathetic nervous system would be valuable for pain assessment, and skin conductance measurement as a pain assessment tool has been suggested.53 However, in an effort to validate the technique in another unit, researchers documented that skin conductance correlated highly with skin temperature, and significant changes in all other vital parameters were observed comparing before- and after-peak data.54 These results indicate that sympathetic neural activity to maintain homeostasis (such as autoregulation of the skin temperature) also result in skin conductance peaks. Consequently, such ‘objective’ techniques should be further improved and validated before introduction into daily clinical neonatal practice for the evaluation of pain.51–54

There are ongoing studies on the impact of neonatal or infant anesthesia, including a randomized controlled design (locoregional versus general anesthesia) with long-term neurodevelopmental assessment as primary outcome.10–12 Based on observations on the association between paracetamol exposure and atopy, we suggest not to limit these outcome data to neurodevelopmental issues.45

Until more sophisticated assessment tools become available, the state-of-the-art study design is based on the simultaneous collection of pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) observations, applying validated pain assessment scores for the specific population.31,35 Sparse or opportunistic sampling techniques and the use of low volume samples in combination with advanced population PK/PD models makes these studies not only more feasible, but also more accurate since the PK/PD variability within the neonatal population can be explored.55

In conclusion, there are still important issues on the pharmacokinetics and -dynamics of analgo-sedatives that need further attention. As well as developing more effective tools to assess pain, we encourage clinicians, ethical committees and other stakeholders to design dose-finding studies in order to improve adequate administration of analgo-sedatives in neonates (i.e. effective dosing, neither over- nor underexposure). The experimental observations in animals concerning neuro-apoptosis lead us to reconsider the modalities used, including both the drugs as well as the doses administered.

Practice points.

Neonatal pain management is not an ‘isolated’ practice, but needs integration as part of developmental care to reduce stress and facilitate neurobehavioral development.

A unit-specific pain management protocol combining assessment based on validated pain assessment tools, and therapy with a limited number of compounds (‘tool box’) of which caregivers are aware of the (side-)effects is the most appropriate approach. Such a ‘tool box’ should also include non-pharmacological interventions.

New practices result in new diagnoses and complications. Opioid exposure may result in tolerance, neonatal withdrawal syndrome or hyperalgesia. Similarly, drug-related toxicity (e.g. paracetamol, propofol) and locoregional anesthesia may result in specific complications. Caregivers should familiarize themselves with these issues.

Research directions.

Pain behavior is not equal to nociception. Development and validation of pain assessment tools that go beyond pain behavior is needed. Such tools will likely be based on integration of surface electromyography, electroencephalography, near-infrared spectroscopy, or autonomic responses.

Long-term neurodevelopmental outcome studies of different groups (preterms, surgical patients, patients with post-hypoxic encephalopathy, hypothermia) following exposure to analgo-sedatives remain crucial.

There are still important issues on pharmacokinetics and -dynamics of analgo-sedatives that need further evaluation. Besides more effective tools to assess pain, we encourage all stakeholders to design dose-finding studies in order to improve adequate (i.e. effective, but neither overexposure) administration of analgo-sedatives in neonates.

Acknowledgments

Funding sources

Karel Allegaert is supported by the Fund for Scientific Research, Flanders (Belgium) (F.W.O. Vlaanderen) by a Fundamental Clinical Investigatorship (1800209N), Johannes van den Anker in part by NIH grants (R01HD060543, K24DA027992, R01HD048689, U54HD071601) and FP7 grants TINN (223614), TINN2 (260908), and NEUROSIS (223060).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

References

- 1.Anand KJ, Hickey PR. Pain and its effects in the human neonate and fetus. N Engl J Med. 1987;317:1321–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198711193172105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tibboel D, Anand KJ, van den Anker JN. The pharmacological treatment of neonatal pain. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2005;10:195–205. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2004.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berde CB, Walco GA, Krane EJ, et al. Pediatric analgesic clinical trial designs, measures, and extrapolation: report of an FDA scientific workshop. Pediatrics. 2012;129:354–64. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-3591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hall RW, Shbarou RM. Drugs of choice for sedation and analgesia in the neonatal ICU. Clin Perinatol. 2009;36:215–26. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2009.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Allegaert K, Veyckemans F, Tibboel D. Clinical practice: analgesia in neonates. Eur J Pediatr. 2009;168:765–70. doi: 10.1007/s00431-009-0932-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thewissen L, Allegaert K. Analgosedation in neonates: do we still need additional tools after 30 years of clinical research? Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed. 2011;96:112–8. doi: 10.1136/adc.2008.145565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walter-Nicolet E, Annequin D, Biran V, Mitanchez D, Tourniaire B. Pain management in newborns: from prevention to treatment. Paediatr Drugs. 2010;12:353–65. doi: 10.2165/11318900-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morton NS. The pain-free ward: myth or reality. Paediatr Anaesth. 2012;22:527–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9592.2012.03881.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davidson AJ. Anesthesia and neurotoxicity to the developing brain: the clinical relevance. Paediatr Anaesth. 2011;21:716–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9592.2010.03506.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schifilliti D, Grasso G, Conti A, Fodale V. Anaesthetic-related neuroprotection: intravenous or inhalational agents? CNS Drugs. 2010;24:893–907. doi: 10.2165/11584760-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patel P, Sun L. Update on neonatal anesthetic neurotoxicity: insight into molecular mechanisms and relevance to humans. Anesthesiology. 2009;110:703–8. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31819c42a4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Durrmeyer X, Vutskits L, Anand KJ, Rimensberger PC. Use of analgesic and sedative drugs in the NICU: integrating clinical trials and laboratory data. Pediatr Res. 2010;67:117–27. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e3181c8eef3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hohmeister J, Kroll A, Wollgarten-Hadamek I, et al. Cerebral processing of pain in school-aged children with neonatal nociceptive input: an exploratory fMRI study. Pain. 2010;150:257–67. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Walker SM, Franck LS, Fitzgerald M, Myles J, Stocks J, Marlow N. Long-term impact of neonatal intensive care and surgery on somatosensory perception in children born extremely preterm. Pain. 2009;141:79–87. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Knibbe CA, Krekels EH, van den Anker JN, et al. Morphine glucuronidation in preterm neonates, infants and children younger than 3 years. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2009;48:371–85. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200948060-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krekels EH, DeJongh J, van Lingen RA, et al. Predictive performance of a recently developed population pharmacokinetic model for morphine and its metabolites in new datasets of (preterm) neonates, infants and children. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2011;50:51–63. doi: 10.2165/11536750-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Graaf J, van Lingen RA, Simons SH, et al. Long-term effects of routine morphine infusion in mechanically ventilated neonates on children’s functioning: five-year follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. Pain. 2011;152:1391–7. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ferguson SA, Ward WL, Paule MG, Hall RW, Anand KJ. A pilot study of preemptive morphine analgesia in preterm neonates: effects on head circumference, social behavior, and response latencies in early childhood. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2012;34:47–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2011.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Penido MG, Garra R, Sammartino M, Pereira e Silva Y. Remifentanil in neonatal intensive care and anaesthesia practice. Acta Paediatr. 2010;99:1454–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2010.01868.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Welzing L, Ebenfeld S, Dlugay V, Wiesen MH, Roth B, Mueller C. Remifentanil degradation in umbilical cord blood of preterm infants. Anesthesiology. 2011;114:570–7. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e318204e043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Choong K, AlFaleh K, Doucette J, et al. Remifentanil for endotracheal intubation in neonates: a randomised controlled trial. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2010;95:F80–4. doi: 10.1136/adc.2009.167338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sammartino M, Bocci MG, Ferro G, et al. Efficacy and safety of continuous intravenous infusion of remifentanil in preterm infants undergoing laser therapy in retinopathy of prematurity: clinical experience. Paediatr Anaesth. 2003;13:596–602. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9592.2003.01101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lago P, Tiozzo C, Boccuzzo G, Allegro A, Zachello F. Remifentanil for percutaneous intravenous central catheter placement in preterm infant: a randomized controlled trial. Paediatr Anaesth. 2008;18:736–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9592.2008.02636.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sammartino M, Garra R, Sbaraglia F, De Riso M, Continolo N, Papacci P. Experience of remifentanil in extremely low-birth-weight babies undergoing laparotomy. Pediatr Neonatol. 2011;52:176–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pedneo.2011.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Allegaert K, van den Anker JN, de Hoon JN, et al. Covariates of tramadol disposition in the first months of life. Br J Anaesth. 2008;100:525–32. doi: 10.1093/bja/aen019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Allegaert K, Rochette A, Veyckemans F. Developmental pharmacology of tramadol during infancy: ontogeny, pharmacogenetics and elimination clearance. Paediatr Anaesth. 2011;21:266–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9592.2010.03389.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alencar AJ, Sanudo A, Sampaio VM, Góis RP, Benevides FA, Guinsburg R. Efficacy of tramadol versus fentanyl for postoperative analgesia in neonates. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2012;97:F24–9. doi: 10.1136/adc.2010.203851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kearns GL, Abdel-Rahman SM, Alander SW, Blowey DL, Leeder JS, Kaufman RE. Developmental pharmacology – drug disposition, action, and therapy in infants and children. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1157–67. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra035092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mossetti V, Ivani G. Controversial issues in pediatric regional anesthesia. Paediatr Anaesth. 2012;22:109–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9592.2011.03655.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leelanukrom R, Suraseranivongse S, Boonrukwanich V, Wechwinij S. Effect of wound infiltration with bupivacaine on postoperative analgesia in neonates and infants undergoing major abdominal surgery: a pilot randomized controlled trial. J Anesth. 2012;26:541–4. doi: 10.1007/s00540-012-1355-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Van Dijk M, Ceelie I, Tibboel D. Endpoints in pediatric pain studies. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2011;67(Suppl 1):61–6. doi: 10.1007/s00228-010-0947-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jacobs A, Bergmans E, Arul GS, Thies KC. The transversus abdominis plane (TAP) block in neonates and infants – results of an audit. Paediatr Anaesth. 2011;21:1078–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9592.2011.03628.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bielsky A, Efrat R, Suresh S. Postoperative analgesia in neonates after major abdominal surgery: ‘TAP’ our way to success! Paediatr Anaesth. 2009;19:541–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9592.2009.02988.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dempsey E, McCreery K. Local anaesthetic eye drops for prevention of pain in preterm infants undergoing screening for retinopathy of prematurity. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011:CD007645. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007645.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Meek J. Options for procedural pain in newborn infants. Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed. 2012;97:23–8. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2011-300508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Slater R, Cornelissen L, Fabrizi L, et al. Oral sucrose as an analgesic drug for procedural pain in newborn infants: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;376(9748):1225–32. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61303-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Allegaert K, Tibboel D. Shouldn’t we reconsider procedural techniques to prevent neonatal pain? Eur J Pain. 2007;11:910–2. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2007.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lemoine C, Paris C, Morris M, Vali K, Beaunoyer M, Aspirot A. Open transumbilical pyloromyotomy: is it more painful than the laparoscopic approach? J Pediatr Surg. 2011;46:870–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2011.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ceelie I, van Dijk M, Bax NM, de Wildt SN, Tibboel D. Does minimal access major surgery in the newborn hurt less? An evaluation of cumulative opioid doses. Eur J Pain. 2011;15:615–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2010.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Allegaert K, Palmer GM, Anderson BJ. The pharmacokinetics of intravenous paracetamol in neonates: size matters most. Arch Dis Child. 2011;96:575–80. doi: 10.1136/adc.2010.204552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Allegaert K, Rayyan M, de Rijdt T, van Beek F, Naulaers G. Hepatic tolerance of repeated intravenous paracetamol administration in neonates. Paediatr Anaesth. 2008;18:388–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9592.2008.02535.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Allegaert K, Naulaers G. Haemodynamics of intravenous paracetamol in neonates. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2010;66:855–8. doi: 10.1007/s00228-010-0860-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hopchet L, Kulo A, Rayyan M, et al. Does intravenous paracetamol administration affect body temperature in neonates? Arch Dis Child. 2011;96:301–4. doi: 10.1136/adc.2010.203778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Van den Anker JN, Tibboel D. Pain relief in neonates: when to use intravenous paracetamol? Arch Dis Child. 2011;96:573–4. doi: 10.1136/adc.2011.211060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Beasley R, Clayton T, Crane J, et al. Association between paracetamol use in infancy and childhood, and risk of asthma, rhinoconjunctivitis, and eczema in children aged 6–7 years: analysis from Phase Three of the ISAAC programme. Lancet. 2008;372(9643):1039–48. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61445-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dart RC, Rumack BH. Intravenous acetaminophen in the United States: iatrogenic dosing errors. Pediatrics. 2012;129:349–53. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Montirosso R, Del Prete A, Bellu R, et al. Level of NICU quality of developmental care and neurobehavioral performance in very preterm infants. Pediatrics. 2012;129:e1129–37. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-0813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hudak ML, Tan RC Committee on drugs; Committee on fetus and newborn; American Academy of Pediatrics. Neonatal drug withdrawal. Pediatrics. 2012;129:e540–60. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-3212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hallett BR, Chalkiadis GA. Suspected opioid-induced hyperalgesia in an infant. Br J Anaesth. 2012;108:116–8. doi: 10.1093/bja/aer332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sammartino M, Garra R, Sbaraglia F, Papacci P. Propofol overdose in a preterm baby: may propofol infusion syndrome arise in two hours? Paediatr Anaesth. 2010;20:973–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9592.2010.03395.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Worley A, Fabrizi L, Boyd S, Slater R. Multi-modal pain measurements in infants. J Neurosci Methods. 2012;205:252–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2012.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fabrizi L, Worley A, Patten D, et al. Electrophysiological measurements and analysis of nociception in human infants. J Vis Exp. 2011;58:3118. doi: 10.3791/3118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Storm H. Skin conductance and the stress response from heel stick in preterm infants. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2000;83:F143–7. doi: 10.1136/fn.83.2.F143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Valkenburg AJ, Niehof SP, van Dijk M, Verhaar EJ, Tibboel D. Skin conductance peaks could result from changes in vital parameters unrelated to pain. Pediatr Res. 2012;71(4 Pt 1):375–9. doi: 10.1038/pr.2011.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.de Cock RF, Piana C, Krekels EH, et al. The role of population PK-PD modelling in paediatric clinical research. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2011;67(Suppl 1):5–16. doi: 10.1007/s00228-009-0782-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]