Abstract

Background

A patient who dies during the followup period of a study about total hip arthroplasty (THA) cannot subsequently undergo a revision. The presence of competing events (such as deaths, in a study on implant durability) violates an assumption of the commonly used Kaplan-Meier (KM) survivorship approach. In that setting, KM-based estimates of revision frequencies will be high relative to alternative approaches that account for competing events such as cumulative incidence methods. However, the degree to which this difference is clinically relevant, and the degree to which it affects different ages of patient cohorts, has been poorly characterized in orthopaedic clinical research.

Questions/purposes

The purpose of this study was to compare KM with cumulative incidence survivorship estimators to evaluate the degree to which the competing event of death influences the reporting of implant survivorship at long-term followup after THA in patients both younger than and older than 50 years of age.

Methods

We retrospectively reviewed 758 cemented THAs from a prospectively maintained single-surgeon registry, who were followed for a minimum of 20 years or until death. Revision rates were compared between those younger than or older than age 50 years using both KM and cumulative incidence methods. Patient survivorship was calculated using KM methods. A total of 21% (23 of 109) of the cohort who were younger than 50 years at the time of THA died during the 20-year followup period compared with 72% (467 of 649) who were older than 50 years at the time of surgery (p < 0.001).

Results

In the cumulative incidence analysis, 19% of the younger than age 50 years cohort underwent a revision for aseptic causes within 20 years as compared with 5% in the older than age 50 years cohort (p < 0.001). The KM method overestimated the risk of revision (23% versus 8.3%, p < 0.001), which represents a 21% and 66% relative increase for the younger than/older than age 50 years groups, respectively.

Conclusions

The KM method overestimated the risk of revision compared with the cumulative incidence method, and the difference was particularly notable in the elderly cohort. Future long-term followup studies on elderly cohorts should report results using survivorship curves that take into account the competing risk of patient death. We observed a high attrition rate as a result of patient deaths, and this emphasizes a need for future studies to enroll younger patients to ensure adequate study numbers at final followup.

Level of Evidence

Level III, therapeutic study.

Introduction

Level I evidence is considered the gold standard for clinical decision-making. However, when evaluating the long-term durability of hip arthroplasty designs, Level I prospective clinical trials are impractical. Thus, to date, large registry databases and longitudinal followup studies have provided the best available evidence regarding the implant design characteristics most likely to provide lasting durability and satisfactory function [2, 4–9, 11, 13, 15, 18, 19, 21–24, 26–29]. Most importantly, because hip arthroplasty was traditionally only performed in older patients, the cohorts from these studies tended to be elderly and thus had low patient survivorship at final followup. High rates of patient attrition introduced bias into these studies, and some authors have rightfully questioned the statistical validity of implant survivorship analyses in these elderly cohorts [1, 3, 10, 14].

The majority of long-term followup studies, including our own, used Kaplan-Meier (KM) [20] survivorship curves to report implant revision rates. A KM survivorship curve estimates the time to a single event of interest and assumes that the event of interest occurs independently from other possible competing events [14]. In the case of joint arthroplasty, the event of interest is typically the occurrence of a revision surgery. However, other events may take place that would compete with or even preclude the possibility of revision surgery. In particular, a patient death is a competing event because patients who die cannot be revised later. The KM approach treats those who died (with no chance of revision) similarly to those who are lost to followup (who could still undergo revision). Prior studies have shown that this biases KM analyses toward an overestimation of event rates [14, 16, 17].

More recent authors have argued for reporting implant revision rates using the cumulative incidence of competing risks (cumulative incidence) methodology. Although arthroplasty surgeons may still be somewhat unfamiliar with reporting revision rates using the cumulative incidence methodology, its use in both our field and others has been reported for some time [1, 3, 30]. The cumulative incidence method reports the probability of failure as a result of the event of interest in the presence of competing risks [14]. If a large number of patients die during followup, late implant failure becomes less likely and survivorship is increased accordingly. The current authors have previously evaluated the long-term followup of TKAs using similar methods [10]. However, the degree to which the differences between KM and competing incidence estimators may be clinically relevant has varied across the few studies on the topic in orthopaedic surgery, and so we wished to further characterize it in a population of patients who have been followed into the third decade after THA. A review of these methods should be useful in informing the design of future long-term followup studies.

Patients and Methods

This study received an institutional review board exemption and was HIPPA-compliant. Our institution has maintained long-term followup records for three separate series of Charnley total hip cohorts. The methodology for each cohort has been previously published [6, 25, 28]. Each series is a prospectively followed, consecutive, nonselected cohort from the time period specified. Followup evaluations were performed by a single surgeon (DDG) not involved in the initial surgical care of the patients. Radiographs were evaluated by two independent observers (JJC, DDG) with agreement by consensus at each followup interval. One observer reviewed all radiographs at each followup interval of all cohorts (JJC). We retrospectively reviewed these records for the current analysis.

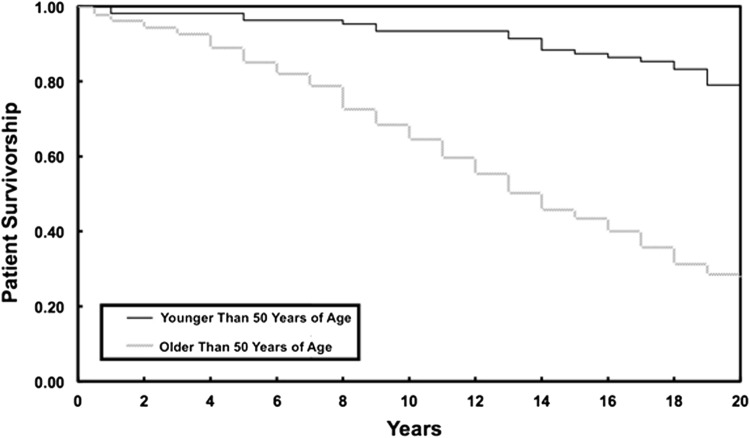

The first cohort consisted of 330 hip arthroplasties in 262 patients performed between July 1970 and April 1972 using first-generation cement techniques [6]. Details from this cohort have been published at regular intervals out to 35 years of followup [5, 6, 12, 18, 19, 27]. The second cohort consisted of 357 hip arthroplasties in 320 patients performed between July 1976 and June 1978 and used modern second-generation cementing techniques [26]. Details from this cohort have been published at regular intervals out to 20 years of followup [25, 26]. The final cohort consisted of 93 hip arthroplasties performed in 69 patients, all of whom were aged 50 years or younger at the time of surgery, performed between January 1970 and December 1976. Details from this cohort have also been published at regular intervals out to 35 years of followup [7, 24, 28]. All patients were followed for a minimum of 20 years or until death. Notably, a total of 21% (23 of 109) of the cohort who were younger than 50 years at the time of THA died during the 20-year followup period compared with 72% (467 of 649) who were older than 50 years at the time of surgery (p < 0.001) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

KM analysis shows the difference in patient survivorship out to final followup between patients younger than or older than 50 years of age at the time of their index procedure. The younger cohort was significantly more likely to survive the duration of the study period (79% versus 28%, p < 0.001).

The surgical approach and prosthesis implantations were done in a uniform fashion across all three cohorts. All operations were done by a single surgeon (RCJ). All patients were implanted with a Charnley hip prosthesis (Thackray, Leeds, UK, or Zimmer, Warsaw, IN, USA) with a polished stainless steel stem and a 22-mm diameter nonmodular femoral head. The acetabular component was made of ultrahigh-molecular-weight polyethylene with an outer diameter of either 40 or 44 mm. Both the femoral and acetabular components were inserted with the use of Simplex P cement (Northill Plastics, London, UK, or Howmedica, Rutherford, NJ, USA). All surgeries were performed through a transtrochanteric approach, and no antibiotics were used perioperatively.

The femoral cementing technique used by the surgeon changed over time. In the hips done between July 1970 and December 1976, cement was inserted using finger-packing [7, 27]. In the hips done between July 1976 and June 1978 [26], a contemporary cement technique was used in which the bone was meticulously dried and all loose cancellous bone was removed. A distal cement plug was then placed and the cement was inserted using a cement gun under pressure. A previous analysis by our group compared the two cement techniques and found no difference in implant survivorship between them [25]; thus, we feel it is reasonable to consider them together as a single group in this analysis.

For our statistical analysis, all three cohorts were combined into a single group. Of note, the third cohort of patients, specifically younger than 50 years of age, included some overlap with the other studies. Thus, after excluding 22 duplicate procedures, we were left with a total of 758 unique Charnley total hip procedures in 635 patients from all three cohorts. The average age was 64 years (range, 18–91 years). Three hundred forty hips were in men (45%). The most common diagnosis was osteoarthritis in 518 hips (68%) followed by posttraumatic osteoarthritis in 83 hips (11%), developmental dysplasia of the hip in 62 hips (8%), rheumatoid arthritis in 32 hips (4%), slipped capital femoral epiphysis in 16 hips (2%), postseptic arthritis in 14 hips (2%), avascular necrosis in 11 hips (1%), Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease in five hips (< 1%), and other diagnoses in 17 hips (2%).

The patients were stratified by age with 109 hips implanted in patients aged 50 years or younger and 649 hips implanted in patients older than 50 years of age. We then compared implant survivorship between the patients 50 years or younger against patients older than 50 years according to cumulative incidence methods [14]. The details of this calculation method have been previously well described [1, 3, 14]. The primary endpoint was revision for aseptic implant failure (pain or radiographic loosening of the implants). Patients who died or who had a revision for an infection or fracture were considered to have had a competing event. Additionally, the risk of revision was also calculated using KM methods using this same cohort. In KM methodology, patients with a competing event are censored and are assigned a risk of revision equal to that of the remaining cohort [20]. Patients with a death or a revision resulting from infection or fracture were censored in this analysis. All curves were truncated at 20 years in each analysis for similar comparison across cohorts. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 13.0 software (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

A larger proportion of the younger patients in this report underwent revision for aseptic causes during the surveillance period than did the older patients. Specifically, 21 of 109 (19%) Charnley hip arthroplasties implanted in patients younger than 50 years of age underwent a revision of either the femoral or acetabular component for aseptic causes within 20 years of their index procedure as compared with 33 of 649 (5%) hips in patients older than 50 years of age (p < 0.001, chi square analysis).

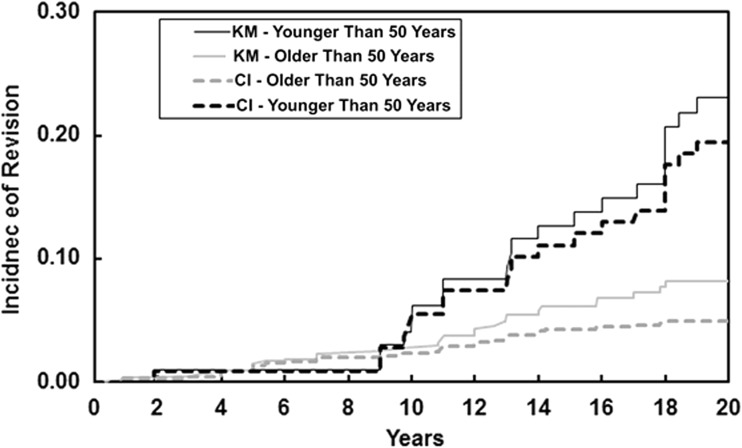

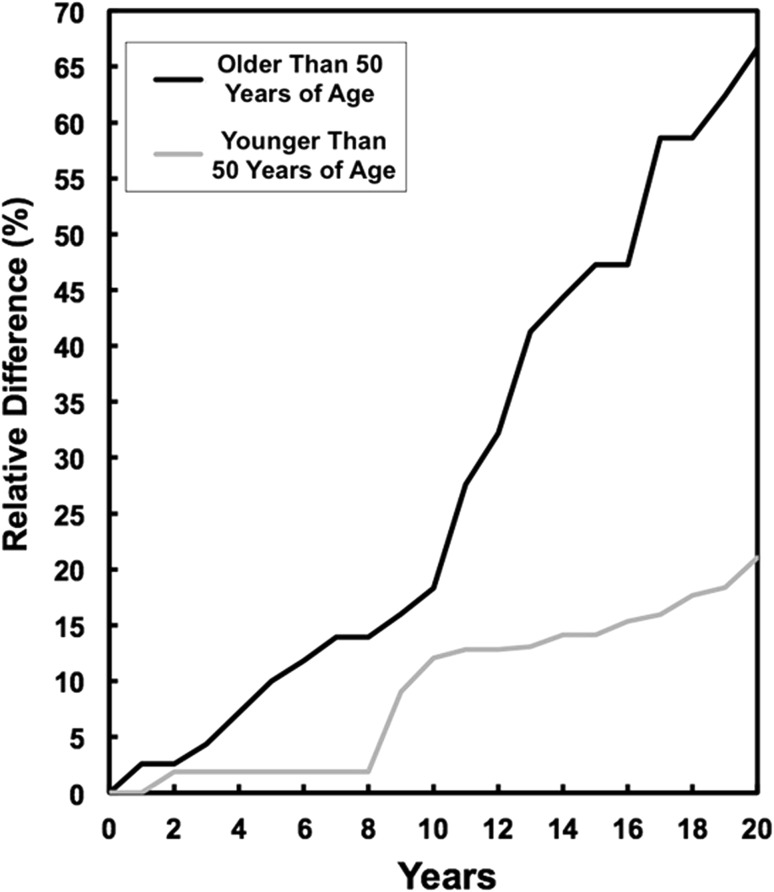

In reporting these incidences, the two analysis methods produced differing results. The cumulative incidence function reported very similar percentages to the actual revision rates noted with an estimated 19% revision rate in the younger than 50 years cohort (95% confidence interval [CI], 13%–27%) and an estimated 5% revision rate in the older than 50 years cohort (95% CI, 3%–7%). However, in the KM analysis, the risk of revision for the younger than age 50 years cohort was reported as 23% (95% CI, 15%–32%) and for the older than age 50 years cohort, the risk of revision was reported as 8% (95% CI, 7%–11%) (p < 0.001) (Fig. 2). This represents a 22% and 66% relative increase, respectively. Patient death represents the primary source of bias in the KM analysis, and thus the relative magnitude of difference between the KM and cumulative incidence methods increased as the patients aged over time during the study period (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

A comparison is shown of implant revision rates using the cumulative incidence methodology and the KM methodology (for the KM method, incidence = 1 − KM survivorship). The incidence of revision was higher for the older than 50 years of age cohort compared with the younger than 50 years of age cohort for both KM and cumulative incidence methods (p < 0.001 for each).

Fig. 3.

Trend lines are plotted, showing the relative difference between the KM and cumulative incidence methods over time. The magnitude of the relative difference between the two methods increased over time as the incidence of patient deaths increased throughout the study period, particularly in the older than 50 years of age cohort.

Discussion

Patients undergoing a THA want to know how long their implant is likely to last. Historically, long-term followup studies of specific implant designs have been one of the few available ways to acquire this information, and most studies have reported implant survivorship using KM methods. However, patient deaths during the study period violate the assumptions of the KM model. Previously, the degree to which this was clinically relevant had not been well established. Thus, we sought to compare the KM and cumulative incidence estimators from a large cohort of patients followed for a minimum of 20 years or until patient death. Overall, we found that KM methodology substantially overestimated revision rates, particularly in elderly cohorts. We feel that the results of this study will be useful in the planning and design of future long-term followup analyses.

This study does have several limitations. First, the patients operated on in our study period from the 1960s and 1970s are likely of different demographics and life expectancy than modern patient populations, and thus the patient survivorship data presented here may not completely correlate with future studies. Second, although implant revision rates are a commonly accepted measure of implant performance, the occurrence of a revision is not an ideal outcome measure because patients may have pain, radiological changes associated with loosening, major medical comorbidities, or be dissatisfied without requesting or undergoing a revision surgery. Third, we have included two cementing techniques in a single cohort for our statistical analysis. However, all of the surgeries were performed by a single surgeon using a polished flat-backed Charnley, and prior studies have shown that there is no difference in the long-term durability despite the difference in cementing technique [4, 25]. Thus, we feel it is appropriate to include them in a single analysis.

Overall, we found that the KM method overestimated the risk of revision by 66% in the older than 50 years of age cohort and by 22% in the younger than 50 years of age cohort. In contrast, the cumulative incidence method more accurately reported the revision risk. The reason for this discrepancy is straightforward. A patient who dies cannot possibly be revised, and this is taken into account in the cumulative incidence methodology [14, 17]. In contrast, in the KM analysis, patients with a competing event (death) are assigned a risk of revision equal to that of the remaining cohort [16, 17], which provides the risk of implant revision assuming that no patient ever dies. Clearly this is an unrealistic scenario, and KM analysis tends to overestimate the risk of revision for this reason [14, 17]. Therefore, the cumulative incidence method is a more appropriate statistical tool for evaluating implant survivorship and we would encourage authors of future long-term followup studies to implement it in favor of the widely used but inappropriately applied KM methodology.

In addition to introducing bias into the KM analysis, the high rate of patient deaths in the older than 50 years of age cohort highlights a second important point. Specifically, only 28% of the older than 50 years cohort survived the duration of the study period, and only 5% required revision for aseptic causes. Thus, simply as a result of the high rates of patient mortality, the older patients are unlikely to require revision for aseptic reasons at any time in their remaining years. Therefore, comparisons of performance across different implant designs would be very difficult. We suggest that clinicians focus their efforts on ensuring regular followup among their younger patients. Younger patients are much more likely to survive to final followup and thus provide a more accurate estimate of implant durability and performance over time.

In summary, our study found that high rates of patient deaths introduced substantial bias into the analysis of long-term followup studies when the results were reported using KM methodology. Because patient death is a competing risk with revision, the use of a KM curve to report revision rates is inappropriate. Future investigators conducting long-term followup studies of hip arthroplasty implants should use patient survivorship curves that account for competing risks. For the investigators designing future long-term followup studies, the patient survivorship curves we provided should be useful for determining the necessary composition of patients, both in terms of patient age and numbers of patients needed, to have adequate numbers for statistically valid comparisons. Furthermore, if we wish to be able to report clinically relevant long-term results of hip arthroplasty designs, it seems likely that multicenter or joint registry studies will be necessary to acquire robust patient numbers of younger patients.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Richard C. Johnston, who performed the operations on the patients described in this analysis.

Footnotes

One of the authors (JJC) is a consultant for and received royalties from DePuy (Warsaw, Inc, USA; for intellectual property transfer for hip and knee implant designs) and from Lippincott Williams & Wilkins (Baltimore, MD, USA; for books edited). This project was supported by the Bierbaum resident research fund.

All ICMJE Conflict of Interest Forms for authors and Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research ® editors and board members are on file with the publication and can be viewed on request.

Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research ® neither advocates nor endorses the use of any treatment, drug, or device. Readers are encouraged to always seek additional information, including FDA-approval status, of any drug or device prior to clinical use.

Each author certifies that his or her institution approved or waived approval for the human protocol for this investigation and that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research.

This work was performed at the University of Iowa (Iowa City, IA, USA) and Des Moines Orthopaedic Surgeons (West Des Moines, IA, USA).

References

- 1.Aalen OO. Nonparametric estimation of partial transition probabilities in multiple decrement models. Ann Stat. 1978;6:534–545. doi: 10.1214/aos/1176344198. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ballard WT, Callaghan JJ, Sullivan PM, Johnston RC. The results of improved cementing techniques for total hip arthroplasty in patients less than fifty years old. A ten-year follow-up study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1994;76:959–964. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199407000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Biau DJ, Latouche A, Porcher R. Competing events influence estimated survival probability: when is Kaplan-Meier analysis appropriate? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;462:229–233. doi: 10.1097/BLO.0b013e3180986753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buckwalter AE, Callaghan JJ, Liu SS, Pedersen DR, Goetz DD, Sullivan PM, Leinen JA, Johnston RC. Results of Charnley total hip arthroplasty with use of improved femoral cementing techniques. A concise follow-up, at a minimum of twenty-five years, of a previous report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:1481–1485. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.00818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Callaghan JJ, Albright JC, Goetz DD, Olejniczak JP, Johnston RC. Charnley total hip arthroplasty with cement. Minimum twenty-five-year follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82:487–497. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200004000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Callaghan JJ, Bracha P, Liu SS, Piyaworakhun S, Goetz DD, Johnston RC. Survivorship of a Charnley total hip arthroplasty. A concise follow-up, at a minimum of thirty-five years, of previous reports. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91:2617–2621. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.01201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Callaghan JJ, Forest EE, Olejniczak JP, Goetz DD, Johnston RC. Charnley total hip arthroplasty in patients less than fifty years old. A twenty to twenty-five-year follow-up note. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998;80:704–714. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199805000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Callaghan JJ, Katz RP, Johnston RC. One-stage revision surgery of the infected hip. A minimum 10-year followup study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1999;369:139–143. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199912000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Callaghan JJ, Liu SS, Firestone DE, Yehyawi TM, Goetz DD, Sullivan J, Vittetoe DA, O’Rourke MR, Johnston RC. Total hip arthroplasty with cement and use of a collared matte-finish femoral component: nineteen to twenty-year follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90:299–306. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.G.00095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Callaghan JJ, Martin CT, Gao Y, Pugely AJ, Liu SS, Goetz DD, Kelley SS, Johnston RC. What can be learned from minimum 20-year followup studies of knee arthroplasty? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473:94–100. doi: 10.1007/s11999-014-3744-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Callaghan JJ, Pedersen DR, Olejniczak JP, Goetz DD, Johnston RC. Radiographic measurement of wear in 5 cohorts of patients observed for 5 to 22 years. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1995;317:14–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Callaghan JJ, Templeton JE, Liu SS, Pedersen DR, Goetz DD, Sullivan PM, Johnston RC. Results of Charnley total hip arthroplasty at a minimum of thirty years. A concise follow-up of a previous report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86:690–695. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200404000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Creighton MG, Callaghan JJ, Olejniczak JP, Johnston RC. Total hip arthroplasty with cement in patients who have rheumatoid arthritis. A minimum ten-year follow-up study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998;80:1439–1446. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199810000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fennema P, Lubsen J. Survival analysis in total joint replacement: an alternative method of accounting for the presence of competing risk. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2010;92:701–706. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.92B5.23470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Firestone DE, Callaghan JJ, Liu SS, Goetz DD, Sullivan PM, Vittetoe DA, Johnston RC. Total hip arthroplasty with a cemented, polished, collared femoral stem and a cementless acetabular component. A follow-up study at a minimum of ten years. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:126–132. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.01214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grunkemeier GL, Anderson RP, Miller DC, Starr A. Time-related analysis of nonfatal heart valve complications: cumulative incidence (actual) versus Kaplan-Meier (actuarial). Circulation. 1997;96:II-70–74; discussion II-74–75. [PubMed]

- 17.Grunkemeier GL, Wu Y. Interpretation of nonfatal events after cardiac surgery: actual versus actuarial reporting. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2001;122:216–219. doi: 10.1067/mtc.2001.117535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnston RC. Clinical follow-up of total hip replacement. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1973;95:118–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnston RC, Crowninshield RD. Roentgenologic results of total hip arthroplasty. A ten-year follow-up study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1983;181:92–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958;53:457–481. doi: 10.1080/01621459.1958.10501452. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Katz RP, Callaghan JJ, Sullivan PM, Johnston RC. Results of cemented femoral revision total hip arthroplasty using improved cementing techniques. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1995;319:178–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Katz RP, Callaghan JJ, Sullivan PM, Johnston RC. Long-term results of revision total hip arthroplasty with improved cementing technique. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1997;79:322–326. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.79B2.7245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keener JD, Callaghan JJ, Goetz DD, Pederson D, Sullivan P, Johnston RC. Long-term function after Charnley total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;417:148–156. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000096807.78689.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Keener JD, Callaghan JJ, Goetz DD, Pederson DR, Sullivan PM, Johnston RC. Twenty-five-year results after Charnley total hip arthroplasty in patients less than fifty years old: a concise follow-up of a previous report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85:1066–1072. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200306000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klapach AS, Callaghan JJ, Goetz DD, Olejniczak JP, Johnston RC. Charnley total hip arthroplasty with use of improved cementing techniques: a minimum twenty-year follow-up study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83:1840–1848. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200112000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Madey SM, Callaghan JJ, Olejniczak JP, Goetz DD, Johnston RC. Charnley total hip arthroplasty with use of improved techniques of cementing. The results after a minimum of fifteen years of follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1997;79:53–64. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.79B1.6699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schulte KR, Callaghan JJ, Kelley SS, Johnston RC. The outcome of Charnley total hip arthroplasty with cement after a minimum twenty-year follow-up. The results of one surgeon. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1993;75:961–975. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199307000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sullivan PM, MacKenzie JR, Callaghan JJ, Johnston RC. Total hip arthroplasty with cement in patients who are less than fifty years old. A sixteen to twenty-two-year follow-up study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1994;76:863–869. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199406000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weber KL, Callaghan JJ, Goetz DD, Johnston RC. Revision of a failed cemented total hip prosthesis with insertion of an acetabular component without cement and a femoral component with cement. A five to eight-year follow-up study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1996;78:982–994. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199607000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wongworawat MD, Dobbs MB, Gebhardt MC, Gioe TJ, Leopold SS, Manner PA, Rimnac CM, Porcher R. Editorial: estimating survivorship in the face of competing risks. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015 Feb 11 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]