Abstract

Background

Local infiltration analgesia and peripheral nerve blocks are common methods for pain management in patients after THA but direct head-to-head, randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have not been performed. A network meta-analysis allows indirect comparison of individual treatments relative to a common comparator; in this case placebo (or no intervention), epidural analgesia, and intrathecal morphine, yielding an estimate of comparative efficacy.

Questions/purposes

We asked, when compared with a placebo, (1) does use of local infiltration analgesia reduce patient pain scores and opioid consumption, (2) does use of peripheral nerve blocks reduce patient pain scores and opioid consumption, and (3) is local infiltration analgesia favored over peripheral nerve blocks for postoperative pain management after THA?

Methods

We searched six databases, from inception through June 30, 2014, to identify RCTs comparing local infiltration analgesia or peripheral nerve block use in patients after THA. A total of 35 RCTs at low risk of bias based on the recommended Cochrane Collaboration risk assessment tool were included in the network meta-analysis (2296 patients). Primary outcomes for this review were patient pain scores at rest and cumulative opioid consumption, both assessed at 24 hours after THA. Because of substantial heterogeneity (variation of outcomes between studies) across included trials, a random effect model for meta-analysis was used to estimate the weighted mean difference (WMD) and 95% CI. The gray literature was searched with the same inclusion criteria as published trials. Only one unpublished trial (published abstract) fulfilled our criteria and was included in this review. All other studies included in this systematic review were full published articles. Bayesian network meta-analysis included all RCTs that compared local infiltration analgesia or peripheral nerve blocks with placebo (or no intervention), epidural analgesia, and intrathecal morphine.

Results

Compared with placebo, local infiltration analgesia reduced patient pain scores (WMD, −0.61; 95% CI, −0.97 to −0.24; p = 0.001) and opioid consumption (WMD, −7.16 mg; 95% CI, −11.98 to −2.35; p = 0.004). Peripheral nerve blocks did not result in lower pain scores or reduced opioid consumption compared with placebo (WMD, −0.43; 95% CI, −0.99 to 0.12; p = 0.12 and WMD, −3.14 mg, 95% CI, −11.30 to 5.02; p = 0.45). However, network meta-analysis comparing local infiltration analgesia with peripheral nerve blocks through common comparators showed no differences between postoperative pain scores (WMD, −0.36; 95% CI, −1.06 to 0.31) and opioid consumption (WMD, −4.59 mg; 95% CI, −9.35 to 0.17), although rank-order analysis found local infiltration analgesia to be ranked first in more simulations than peripheral nerve blocks, suggesting that it may be more effective.

Conclusions

Using the novel statistical network meta-analysis approach, we found no differences between local infiltration analgesia and peripheral nerve blocks in terms of analgesia or opioid consumption 24 hours after THA; there was a suggestion of a slight advantage to peripheral nerve blocks based on rank-order analysis, but the effect size in question is likely not large. Given the slight difference between interventions, clinicians may choose to focus on other factors such as cost and intervention-related complications when debating which analgesic treatment to use after THA.

Level of Evidence

Level I, therapeutic study.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s11999-015-4619-9) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Introduction

Total hip arthroplasty (THA) is one of the most common and successful surgeries in modern medicine, but it is associated with substantial postoperative pain [43]. Effective treatment of postoperative pain continues to be a challenge for physicians because it can influence surgical outcomes and it has been reported that treatment of postoperative pain often remains insufficient [5, 17]. Effective treatment of postoperative pain is crucial to avoid impairment in mobility, adverse events, and prolonged hospitalization. Enhanced perioperative anesthesia protocols combining preemptive oral medication and the use of peripheral nerve blocks have been shown to improve patient satisfaction after hip arthroplasty and early postoperative rehabilitation [23, 39]. In recent years, local infiltration analgesia has been incorporated in analgesic regimens for THAs and TKAs. Use of local infiltration analgesia has gained popularity since it was first reported by Kerr and Kohan [30], and has proved effective in reducing postoperative pain after various surgical procedures [65]. The analgesic technique involves infiltration of the surgical wound and surrounding tissues at the time of surgery with a high-volume, long-acting local anesthetic solution, and frequently, with adjuvants (epinephrine, ketorolac, opioid, or steroids). A recent systematic review and meta-analysis [65] suggested that local infiltration analgesia is an effective analgesic method for THA because its use has been shown to reduce patient pain scores and analgesic consumption.

Head-to-head, direct, comparative randomized controlled trials (RCTs) between local infiltration analgesia and peripheral nerve blocks for postoperative analgesia in THA have not been performed, to our knowledge. In the absence of trials involving a direct comparison of interventions, an indirect comparison can provide valuable evidence for the relative treatment effects between competing interventions [27]. Network meta-analysis, also known as multiple-treatments comparisons, uses novel statistical methods that allow indirect comparisons of individual treatments relative to a common comparator, yielding an estimate of comparative efficacy. Network meta-analysis enabled us to synthesize data from direct (head-to-head) and indirect (through a common comparator) comparisons (comparisons of diverse regimens) [49]. For example, if we have one study that compares treatment A with treatment B and another study that compares treatment B with treatment C, an indirect statistical relative effect of treatment A compared with treatment C can then be inferred. When more treatments are involved (eg, D, F, H), numerous loops of indirect comparisons can be created. With additional treatments, or results from certain pairs of treatments, there may be sufficient evidence to perform direct meta-analyses (eg, two or more trials on A vs B), thereby improving the information network and a greater chance for applicability in practice [35]. In addition, the Bayesian approach enables us to estimate the rank probability that each of the treatments is the best, the second best, and so on [1]. Network meta-analysis could prove especially valuable in orthopaedics where large RCTs are uncommon, and rapidly changing technology further limits direct, head-to-head comparative trials. To our knowledge, our study is one of the first to have used this novel research method in the orthopaedic literature.

The aim of our study was to perform a systematic review and network meta-analysis of RCTs that compared use of local infiltration analgesia and peripheral nerve blocks with a placebo or control, epidural analgesia or intrathecal morphine, for postoperative pain management after THA in adult patients. The objective was to compare the efficacy of local infiltration analgesia and peripheral nerve blocks in reducing patient-reported pain and total opioid consumption 24 hours postoperatively. Specifically, we asked: (1) Compared with placebo, does local infiltration analgesia reduce patient pain scores and opioid consumption? (2) Compared with placebo, do peripheral nerve blocks reduce patient pain scores and opioid consumption? (3) Is local infiltration analgesia favored over peripheral nerve blocks for patient pain management postoperatively after THA?

Materials and Methods

The protocol for our systematic review was established a priori. The methodology and reporting of our review complies with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement [36].

Randomized clinical trials were considered acceptable for inclusion in our study if they met the eligibility criteria following patient and problem intervention comparison outcome (PICO) order (Table 1).

Table 1.

PICOS design and eligibility criteria used for the network meta-analysis

| P | Adult patients undergoing unilateral hip arthroplasty. |

| I | Local infiltration analgesia or peripheral nerve blocks (techniques for postoperative pain after hip arthroplasty. Studies were included for interventions regardless of the mode of administration (intraoperative and/or postoperative), delivery method (single shot vs continuous infusion), type of local anesthetic, use of adjuvants, and concentration or volume of drugs. Peripheral nerve blockade included femoral nerve block or 3-in-1 block, lumbar plexus block, psoas compartment block, and fascia iliaca compartment block. |

| C | Placebo or control group for the two pairwise meta-analyses. Placebo was defined as infiltration with normal saline or “sham nerve block”. Control was defined as no intervention (no infiltration or no nerve block); also study arms receiving patient-controlled analgesia were considered as control groups only if the other study arms also had access to patient controlled analgesia with the same drug, dosage, and restrictions. For the network meta-analysis studies that compared local infiltration analgesia or peripheral nerve block techniques with epidural analgesia and intrathecal morphine also were included. |

| O | Pain scores measured with the VAS (0 cm–10 cm or 0 mm–100 mm scale) or the numerical rating scale (0–10) at rest and/or cumulative opioid consumption (mg) at 24 hours after THA. All pain scores were converted to a continuous 0 to 10 scale (ie, if VAS of 0–100 mm was used, this was converted to a 0–10 scale) for uniformity of the analysis. |

| S | Only prospective randomized controlled trials were included. |

| Intervention group and placebo/control group had access to rescue analgesia or patient controlled analgesia. No language restriction |

PICOS = patient intervention comparison outcome study.

Data Sources and Search Strategies

A medical reference librarian (PE) experienced in searches for systematic reviews developed the search strategy with input from the study investigator (JHJA). We searched PubMed, Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid EMBASE, Cochrane CENTRAL, Web of Science, and Scopus from inception through June 30, 2014. The search strategy used controlled vocabulary supplemented with keywords describing the following concepts: hip replacement, local infiltration, analgesia, peri-/intra-articular infiltration, nerve block, and randomized. To ensure a comprehensive literature search, we reviewed references cited in primary sources. Non-English language studies were excluded from the search. Grey literature was included in the search, with the same inclusion criteria as published trials. Grey literature was defined, based on the Cochrane Handbook [25], as unpublished reports that are produced by all levels of government, academics, business and industry in print and electronic formats but that are not controlled by commercial publishers. Only one unpublished trial (published abstract) fulfilled our inclusion criteria and contained all the necessary information (after the respective author provided additional information via author contact email) and therefore was included in this review. All other studies included in this systematic review were full published articles. Including data from unpublished studies is a possible way of avoiding publication bias and the support for the use of grey literature in systematic reviews has been evident in recent questionnaires to authors and editors [25]. The full search strategy is presented in Appendix 1 (Supplemental materials are available with the online version of CORR ®).

Study Selection

A pair of reviewers (JHJA, CCW) independently evaluated eligibility of candidate titles and abstracts. At both stages of selection, we estimated chance-adjusted agreement statistics among reviewers with adequate kappa statistic (κ = 0.92 for title and abstract review; κ = 0.90 for full text review). All disagreements were settled by the opinion of a third senior reviewer (SPW).

Included Trials and Risk of Bias

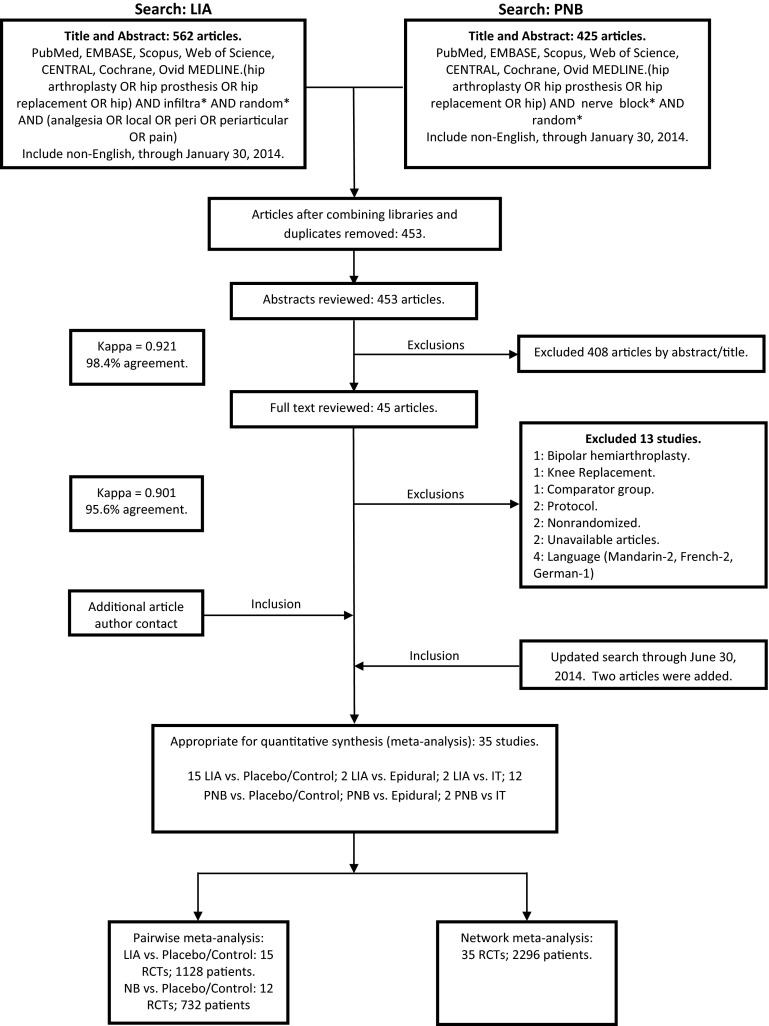

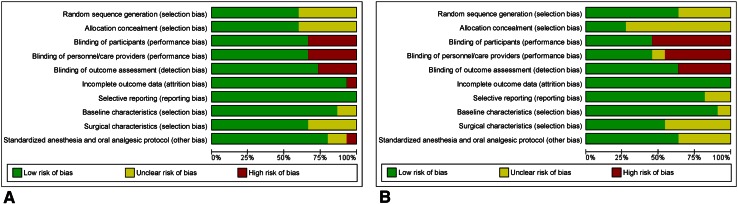

After consensus was reached, 35 RCTs (2296 patients) were included in the network meta-analysis (Fig. 1). For the pairwise meta-analyses, we included 15 RCTs (1128 patients) and 12 RCTs (732 patients), comparing local infiltration analgesia and peripheral nerve blocks with placebo/control, respectively. The imbalance on baseline characteristics and methodology also were assessed on included trials comparing local infiltration analgesia (Table 2) and peripheral nerve blocks (Table 3) with placebo/control. Baseline characteristics of additional studies included in the network meta-analysis that compared local infiltration analgesia or peripheral nerve blocks with epidural analgesia or intrathecal morphine also were evaluated and explored. (Supplemental Table 1. Supplemental material is available with the online version of CORR®). The overall risk of bias of the included trials varied from moderate to low (Fig. 2) based on the Cochrane Collaboration risk assessment tool [25]. Studies that did not mention if blinding was present or absent were considered at high risk for bias under the blinding categories. Overall, the risk of bias was likely low. Only one unpublished study was included in the overall analysis [11].

Fig. 1.

The study selection process is shown. LIA = local infiltration analgesia; PNB = peripheral nerve blocks; EMBASE = Excerpta Medica database; IT = intrathecal morphine; RCTs = randomized controlled trials.

Table 2.

Characteristics of RCTs

| Study | Patients | Procedure | Groups (number) | LIA components |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zoric et al. [66], 2014; France | N = 58; age range, 38–80 years; sex, F%, 59; diagnosis, not available; mean BMI, 27.5 kg/m2; ASA Classes I–III | Primary unilateral THA; posterolateral approach; drainage | LIA (29), placebo (29) | Ropivacaine 0.2% 2 mg/mL; 80 mL |

| Chen et al. [10], 2014; Taiwan | N = 96; mean age, 54 years; Sex, F%, 57; diagnosis, OA, ONFH; mean BMI, not available; ASA Classes I–III | Elective, primary unilateral THA; anterolateral approach; cementless; no drainage | LIA (48); placebo (48) | Bupivacaine 0.5% diluted in normal saline to 60 mL |

| Solovyova et al. [54], 2013; USA | N = 105; mean age, 60 years; sex, F%, 52; diagnosis: not available; mean BMI, 29 kg/m2; ASA class, not available | Unilateral THA; anterolateral and posterior approach† | LIA continuous infusion (35); LIA (35); placebo (35) | Ropivacaine 0.2% (50 mL); ketorolac 15 mg; adrenaline 0.5 mg; continuous infusion ropivacaine 0.2%, 5 mL/hour for 48 hours |

| Nakai et al. [44], 2013; Japan | N = 54; mean age, 66 years; sex, F%, 80; diagnosis, OA, ONFH; BMI, not available; ASA class, not available | Unilateral THA, anterolateral approach MIS | LIA (28); control (26) | Bupivacaine 0.5% 20 mL; morphine hydrochloride 10 mg; 0.5% epinephrine 0.3 mg diluted in normal saline to 30 mL |

| Pandazi et al. [45], 2013; Greece | N = 41; mean age, not available†; sex, F%, not available;† diagnosis, OA; BMI, not available†; ASA class, not available† | Elective unilateral THA, postero- lateral approach; cementless; drainage | LIA (20); control (21) | Ropivacaine, 3 mg/kg; morphine, 4–10 mg (titration); methylprednisolone, 40 mg; epinephrine, 1/1000 (0.3 mL–300 mcg); clonidine, 1 mcg/kg; cefuroxime, 750 mg—all diluted in normal saline to 100 mL |

| Murphy et al. [43], 2012; Ireland | N = 91; mean age, 56 years; sex, F%, 44; diagnosis, OA; weight, 81 kg; ASA class, not available | Primary unilateral THA; posterior approach | LIA (45); placebo (46) | Levobupivacaine 150 mg, diluted in normal saline to 60 mL |

| Dobie et al. [13], 2012; UK | N = 92; mean age, 68 years; sex, F%, 45; diagnosis, not available; BMI, 28 kg/m2; ASA Classes I–III | Primary unilateral THA, posterior approach | LIA (46); control (46) | Levobupivacaine 0.125%, 1 mg; adrenaline 1:200,000 per mL, diluted with normal saline to 160 mL |

| Aguirre et al. [2], 2012; Switzerland | N = 72; mean age, 58 years; sex, F%, 51; diagnosis, not available; BMI, 27 kg/m2; ASA Classes I–III | Elective unilateral hip arthroplasty; direct lateral approach MIS | LIA continuous infusion (36); placebo (36) | Ropivacaine 0.3% 20 mL injection; continuous infusion of ropivacaine 0.3% at 8 mL/hour for 48 hours |

| Liu et al. [37], 2011; China | N = 80; mean age, 74 years; sex, F%, 26; diagnosis, OA; BMI, 26 kg/m2; ASA Classes I–III | Elective: primary unilateral THA, postero-lateral approach | LIA (40); placebo (40) | Bupivacaine 30 mg (15 mg/1.5 mL); morphine 5 mg; betamethasone 1 mL; epinephrine 0.5 mL (1:1000) diluted in normal saline to 60 mL |

| Chen et al. [9], 2010; Taiwan | N = 91; mean age, 53 years; sex, F%, 41; diagnosis: OA, ONFH; BMI, 24 kg/m2; ASAClasses I–III | Elective primary unilateral THA; antero-lateral approach; cementless;no drainage | LIA continuous infusion (45); placebo (46) | Bupivacaine 0.5%; continuous infusion at 2 mL/hour for 48 hours via pain control infusion pumps |

| Busch et al. [8], 2010; England | N = 64; mean age, 63 years; sex, F%, 48; diagnosis, OA; BMI, 30 kg/m2; ASA Classes I–III | Unilateral THA; direct lateral approach | LIA (32); control (32) | Ropivacaine 400 mg; morphine 5 mg; ketorolac 30 mg; epinephrine 0.6 mL (1/1000), all diluted in normal saline to 100 mL |

| Lee et al. [34], 2009; Korea | N = 60; mean age, 53 years; sex, F%, 40; diagnosis, ONFH, dysplasia, Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease, pyogenic arthritis; BMI, 23 kg/m2; ASA class, not available | Primary unilateral THA; anterolateral approach MIS | LIA (30); control (30) | Ropivacaine 6.8 mg; morphine HCL 5 mg; methylprednisolone acetate 40 mg, all diluted in normal saline to 90 mL |

| Weng et al. [62], 2008; China | N = 76; mean age, 74 years; sex, F%, 66; diagnosis, not available; BMI, not available; ASA class, not available | Primary unilateral THA; direct lateral approach | LIA (30); placebo (38) | Ropivacaine 150 mg; morphine 4 mg; methylprednisolone 40 mg; epinephrine 0.3 mL, 1 mg/mL, all diluted in normal saline to 100 mL |

| Andersen et al. [3], 2007; Denmark | N = 37; mean age, 63 years; sex, F%, 30; diagnosis, OA; BMI, not available; ASA class, not available | Unilateral THA; direct posterior approach; MIS; cementless; no drainage | LIA continuous infusion (19); placebo (18) | Ropivacaine 300 mg; ketorolac 30 mg; adrenaline 0.5 mg, all diluted in normal saline to 151.5 mL; continuous infusion the next morning, ropivacaine 150 mg, ketorolac 30 mg, adrenaline 0.5 mg, all diluted in normal saline to 21.5 mL |

| Parvataneni et al. [46], 2007; USA | N = 71; mean age, 63 years; sex, F%, 49; diagnosis, OA; BMI, 28 kg/m2; ASA class, not available | Unilateral THA; postero-lateral approach | LIA (35); control (36) | Bupivacaine 0.5% 200–400 mg; morphine sulfate 4–10 mg; methylprednisolone acetate 40 mg; epinephrine 1/1000 300 µg; cefuroxime 750 mg, 10 mL; normal saline 22 mL |

| Administration method | Anesthesia/oral analgesia | Postoperative analgesic protocol* | Rescue analgesia* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single-shot intraoperative LIA; intraarticular and subcutaneous injection; postimplant, 40 mL injected in deep tissues (capsule, gluteus maximus/medius muscles, and rotating muscles), 40 mL in superficial tissues (fascia, subcutaneous tissues, and skin) | General: standardized anesthesia and oral (pre- and postoperative) analgesic protocol | Paracetamol 1 g every 6 hours; nefopam 60–120 mg/24 hours; NSAIDs 100 mg (when persistent high VAS) | PCA Morphine IV 1 mg/mL, bolus of 1 mL every 6 minutes—no maximum dose per 4 hours |

| Single-shot intraoperative LIA; intraarticular injection after closure of joint capsule—60 mL bupivacaine 0.5% injected directly in joint space | General: standardized anesthesia and oral (pre- and postoperative) analgesic protocol | Parecoxib 40 mg IV every 12 hours; acetaminophen 500 mg by mouth every 6 hours; meperidine 50 mg IM at 4-hour intervals if VAS > 40 | Meperidine 0.5 mg/kg IV at 10-minute intervals by patient request |

| Single-shot and continuous infusion; intra- and postoperative LIA; intraarticular and subcutaneous injection; infiltration of the joint capsule, all exposed muscle and tissue (fascia lata and subcutaneous tissue) with 50 mL of cocktail; catheter placed before wound closure, deep to the iliotibial band with tip anterior to joint, exiting the skin distal and anterior to the incision | General: standardized anesthesia and oral (pre- and postoperative) analgesic protocol | Celecoxib 200 mg every 12 hours; pregabalin 50 mg every 12 hours; acetaminophen 975 mg every 6 hours | PCA Hydromorphone IV 0.2 mg available every 10 minutes |

| Single-shot periarticular injection | General: standardized anesthesia and oral (pre- and postoperative) analgesic protocol. | Not available | Diclofenac sodium suppository |

| Single-shot, intraoperative LIA; intraarticular injection; 60 mL injected in anterior capsule/iliopsoas tendon before final reduction; 40 mL injected after final hip reduction in abductors, fascial lata, gluteus maximus, posterior capsule, short external rotators, synovium | Spinal, standardized anesthesia and oral (pre- and postoperative) analgesic protocol | Lornoxicam 8 mg IV, every 12 hours; paracetamol 500 mg every 6 hours | PCA Morphine IV, 1 mg/mL, dose: 0.8–1.2 mL, according to patient’s age; 8-minute lockout |

| Single-shot, intraoperative LIA; intraarticular and subcutaneous injection after insertion of acetabular component/before insertion of femoral stem; 50 mL injected through medial and anterior capsular spaces and around short external rotators and gluteus maximus; then 10 mL infiltrated around tensor fascia lata and subcutaneously before closing wound | Spinal: standardized anesthesia and oral (pre- and postoperative) analgesic protocol | Paracetamol 1 g every 6 hours; diclofenac 75 mg every 12 hours | PCA Morphine IV‡ |

| Single-shot, intraoperative LIA; intraarticular and subcutaneous injection; 20 mL injected anteriorly to lateral cutaneous nerve, 30 mL in split fibers of gluteus maximus, 20 mL to capsule and piriformis, 3 mL inferiorly to the tensor fascia lata, 30 mL to the anterior subcutaneous border, and 30 mL to posterior subcutaneous border | General and spinal; standardized anesthesia and oral (pre- and postoperative) analgesic protocol | Acetaminophen 1 g IV every 6 hours | Morphine IV, 10 mg as required, every 4–6 hours |

| Continuous epicapsular infusion; after implantation of prosthesis, sterile fenestrated catheter set by epicapsular placement; then 20 mL ropivacaine 0.3% injected in wound catheter, distal part of catheter adhered to capsule and proximal placed subcutaneously | Spinal: standardized anesthesia and oral (pre- and postoperative) analgesic protocol-. | Acetaminophen 1 g every 6 hours | PCA Morphine IV, no basal infusion; 2 mg bolus; 8-minute lockout |

| Single-shot, intraoperative LIA; intraarticular and subcuticular injection: 15 mL injected in joint capsule after implantation of prosthesis; 20 mL injected after capsulorrhaphy to gluteus muscles, ilopsoas, external rotators; 25 mL injected in synovium, fascia lata, and subcuticular tissue | Spinal: standardized anesthesia and oral (pre- and postoperative) analgesic protocol-. | Celecoxib 200 mg every 12 hours | PCA Morphine IV, 25 mg/100 mL, 0.5-mg bolus, 6-minute lockout; maximum dose of 5 mg/hour for first 48 hours |

| Continuous infusion; intra- and postoperative LIA; 12 mL intraarticular injection and 12 mL subcutaneous injection of bupivacaine 0.5%; catheter placed percutaneously through portal site 5 cm anterior and distal to greater trochanter, positioned intraarticularly at level of femoral head | General: standardized anesthesia and oral (pre- and postoperative) analgesic protocol | Parecoxib 40 mg IV every 12 hours; acetaminophen 500 mg by mouth every 6 hours; meperidine 50 mg IM at 4-hour intervals when VAS > 40 | Meperidine 0.5 mg/kg IV at 10-minute intervals by patient request |

| Single-shot: intraoperative LIA; intraarticular and subcuticular injection, 20 mL in posterior capsule after femoral component insertion; 20 mL injected in anterior capsule before hip reduction and capsular closure; 60 mL injected in fat and subcuticular tissues | General and spinal§ Standardized anesthesia protocol | Not available¶ | PCA Morphine IV, bolus 1.5 mg, 6-minute lockout and maximum 15 mg/hour |

| Single-shot; intraoperative LIA; intraarticular and subcutaneous injection 30 mL injected before inserting prosthesis; 30 mL administered immediately before reducing prosthesis in synovial sheath, joint capsule, deep fascia, and damaged muscle layer; 30 mL injected in subcutaneous tissue and adipose layer | General + epidural (LIA) and general (placebo), preemptive protocol only for LIA group | Acetaminophen 650 mg every 12 hours by mouth for 48 hours (LIA only); oxycodone controlled-release 5 mg/10 mg every 12 hours by mouth for 48 hours (LIA only); NSAIDs (both) | PCA Morphine IV, dose according to patient age, height, and weight |

| Single-shot; intraoperative LIA | General: standardized anesthesia protocol | Not available | PCA Fentanyl 0.01 mg/mL |

| Continuous infusion; intra- and postoperative LIA injected in equal proportions whole length of wound, muscles, subcapsular, and subcuticular tissues; catheter placed at end of surgery, with tip in joint, then penetrating capsule, running parallel under entire wound over fascia | Spinal | Paracetamol 1 g every 6 hours | PCA Oxycodone IV during first 8 hours if VAS > 30; self- administered 5 mg by mouth |

| Single-shot; intraoperative LIA; intraarticular injection Before final reduction, anterior capsule, iliopsoas tendon, and insertion site injected; after final reduction (before irrigation and closure) abductors, fascia lata, gluteus muscles, posterior capsule, short external rotators, synovium injected | Spinal: standardized anesthesia and oral (pre- and postoperative) analgesic protocol | Ketorolac IV (30 mg if < 65 years) every 6 hours as needed; celecoxib 200 mg by mouth daily; acetaminophen 1000 mg by mouth every 6 hours; Oxycodone sustained-release 10/20 mg by mouth every 12 hours; oxycodone 5 mg by mouth every 6 hours as needed | PCA |

* First postoperative day; †analysis revealed no significant differences in distribution of patients in the surgical approach. Patient demographics like age, sex, BMI, and American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status did not differ between groups; ‡authors did not specify drugs and/or dosage; §no statistical significant difference in distribution of spinal and general anesthesia between treatment groups; ¶patients used other analgesic during postoperative period (acetaminophen 325–650 mg/codeine 8 mg; acetaminophen 300 mg/caffeine 30 mg/codeine 8 mg; acetaminophen 300 mg/codeine 30 mg). Randomized, controlled trial (RCT) did not specify frequency or distribution among treatment groups; LIA = local infiltration analgesia; IM = intramuscular; PCA = patient-controlled anesthesia; IV = intravenous; MIS = minimally invasive surgery; OA = osteoarthritis; ONFH = osteonecrosis of femoral head.

Table 3.

Characteristics of randomized controlled trials regarding peripheral nerve block compared with placebo/control

| Study | Patients | Procedure | Groups (number) | Injection |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wiesmann et al. [63], 2014; Germany | N = 80; mean age, 66 years; sex, F%, 54; diagnosis, not available; BMI, 28 kg/m2; ASA Classes I–II | Elective unilateral THA; cementless | Femoral nerve block (40); control (40) | Single-shot, bupivacaine 0.25%; clonidine 20 µg; total volume, 15 mL |

| Shariat et al. [51], 2013; USA | N = 32; mean age, 59 years; sex, F%, 57; diagnosis, not available; BMI, 30 kg/m2; ASA Classes I–III | Unilateral THA | Fascia iliaca block, (16); placebo (16) | Single-shot, ropivacaine 0.5%, 30 mL |

| Green et al. [23], 2013; Ireland | N = 53; mean age, not available; sex, F%, not available; diagnosis, not available; BMI, not available; ASA class, not available | Primary unilateral THA, anterolateral approach | Psoas compartment block (26); control (27) | Single-shot, bupivacaine 0.25%, 40 mL; normal saline, 10 mL |

| Cucereanu Badica et al. [11], 2010; Romania | N = 62 mean age, 71 years; sex, F%, 55; diagnosis, not available; BMI, not available; ASA class, not available | Unilateral THA | Fascia iliaca compartment block (30); control (32) | Single-shot, ropivacaine 0.5%, 40 mL |

| Marino et al. [39], 2009; USA | N = 225; mean age, 67 years; sex, F%, 67; diagnosis, OA; BMI, 27 kg/m2; ASA Classes I–III | Primary unilateral THA, posterolateral approach | Lumbar plexus block, continuous infusion (75); femoral nerve block, continuous infusion (75); control (75) | Continuous infusion: ropivacaine 0.5% 0.6 mL/kg (maximum dose, < 300 mg); continuous pump, ropivacaine 0.2%, rate 0.15 mL/kg/hour for 48 hours |

| Koroglu et al. [31], 2008; Turkey | N = 30; mean age, 57 years; sex, F%, 70; diagnosis, not available; BMI: 26 kg/m2; ASA Classes I–II | Elective unilateral THA | 3-in-1 block (15); placebo (15) | Single-shot, bupivacaine 0.25%, 40 mL |

| Stevens et al. [57], 2007; Australia | N = 44; mean age, 68 years; sex, F%, 41; diagnosis, not available; BMI, not available; ASA Classes I–III | Unilateral THA | Modified fascia iliaca compartment block (22); placebo (22) | Single-shot, bupivacaine 0.5% 30 mL; adrenaline 1:200,000; clonidine 150 μg, 9 mL; total volume, 40 mL |

| Siddiqui et al. [52], 2007; USA | N = 34; mean age, 55 years; sex, F%, 53; diagnosis, not available; BMI, 29 kg/m2; ASA Classes I–III | Elective unilateral THA | Lumbar plexus block, continuous infusion (17); control (17) | Continuous infusion, bupivacaine 0.25%; bolus, 20 mL, with 5-mL increments, followed by infusion of bupivacaine 0.125% at 10 mL/hour for 36 hours |

| Singelyn et al. [53], 2005; Belgium | N = 30; mean age, 66 years; sex, F%, 63; Diagnosis, not available; BMI, 26 kg/m2; ASA Classes I–III | Elective unilateral THA | Femoral nerve block, continuous infusion (15); control (15) | Continuous infusion, bupivacaine 0.25%; epinephrine 1:200,000; total volume, 40 mL; continuous infusion, bupivacaine 0.125%, rate 10 mL/hour |

| Biboulet et al. [7], 2004; France | N = 45; mean age, 56 years; sex, F%, 44; diagnosis, not available; BMI: 25 kg/m2; ASA Classes I–III | Elective unilateral THA | Femoral nerve block (16); psoas compartment block (15); control (14) | Single-shot, bupivacaine 0.375% 2 mg/kg; clonidine 2 μg/kg |

| Stevens et al. [58], 2000; Switzerland | N = 57; mean age, 66 years; sex, F%, 50; diagnosis, not available; BMI, 26 kg/m2; ASA Classes I–III | Elective unilateral THA | Lumbar plexus block (28); control (29) | Single-shot, bupivacaine 0.5% 0.4 mL/kg; epinephrine 1:200,000 |

| Fournier et al. [18], 1998; Switzerland | N = 40; mean age, 69 years; sex, F%, 67; diagnosis, not available; weight, 71 kg; ASA Classes I–III | Unilateral THA | 3-in-1 block (20); placebo (20) | Bupivacaine 0.5%; epinephrine 1:200,000; total volume, 40 mL |

| Administration method | Anesthesia/oral analgesia | Postoperative analgesic protocol* | Rescue analgesia* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Preoperative; neurolocation: nerve stimulator | General, standardized anesthesia and oral (pre- and postoperative) analgesic protocol | Ibuprofen†; | Piritramide† when VAS > 4 |

| Postoperative (patients with ≥ 3 on pain scale after 30 minutes in PACU with IV PCA); neurolocation, ultrasound-guided block; standardized injection technique with injection pressure monitor to exert pressure of 20 psi; injection considered successful when spread of Local anesthetic reached the femoral nerve medially and ≥ 3 cm laterally from the point of injection beneath the fascia iliaca toward anterior-superior iliac spine; two operators agreed on needle placement and on spread of Local anesthetic | General, standardized anesthesia protocol | Not available | PCA, morphine IV, 1.5 mg every 6 minutes; maximum 4-hour dose 20 mg; no continuous infusion. |

| Intraoperative; neurolocation: clinical landmarking (inferior joint capsule divided and reflected, identifying the iliopsoas) | Spinal, standardized anesthesia and oral (pre- and postoperative) analgesic protocol-. | Paracetamol 1 g every 6 hours; diclofenac 75 mg every 12 hours; oxycodone 10 mg every 12 hours | Oxycodone every 4 hours |

| Preoperative, neurolocation, clinical landmarking—after central neuraxial block, needle inserted perpendicularly to skin 1 cm below inguinal ligament at junction of middle and outer third of line joining pubic tubercle and anterior superior iliac spine. Needle advanced until “two pops” felt. After 10 mL, surgeons rechecked for free return of liquid | General, standardized anesthesia protocol | Not available | PCA, morphine IV, 4-mg bolus on demand |

| Postoperative, neurolocation, nerve stimulator. Position of catheter confirmed with injection of contrast medium followed by AP radiograph | Spinal, standardized anesthesia and oral (pre- and postoperative) analgesic protocol | Ketorolac IM, 30 mg every 6 hours | PCA, hydromorphone IV, 0.3 mg every 10 minutes, maximum 1.2 mg/hour; supplemental bolus of 1.0 mg IV hydromorphone available every 6 hours for breakthrough pain when VAS pain scores > 5 |

| Preoperative; neurolocation: nerve stimulator. Block performed using technique of Winnie et al. [64]; injection performed within 2 minutes with distal pressure application to increase spread of Local anesthetic in the psoas sheath. Presence of sensory block in femoral, obturator, and lateral cutaneous nerve dermatomes tested with pin-prick test before general anesthetic administered. Total sensory block at distribution of all three nerve distribution areas, or total block at the nerve distribution area of two target nerves and more than 80% block at the distribution area of the third target nerve was accepted as successful. | General, standardized anesthesia and oral (pre- and postoperative) analgesic protocol. | Not available. | PCA, tramadol, loading dose 20 mg every 3 minutes until VAS ≤ 3, basal infusion rate 5 mg/hour, bolus dose of 20 mg—lockout of 15 minutes. Bolus dose increased to 25 mg in patients with VAS > 3 (0.5 mg/hour; meperidine used as additional analgesic if pain not controlled |

| Preoperative; neurolocation: clinical markings. Approach: bock being performed 1 cm above inguinal ligament; needle traverses superficial fascia, then traverses fascia transversalis | Spinal, standardized anesthesia protocol | No NSAIDs, codeine, or other opioids given in first 24 hours | PCA, morphine IV, 1 mg bolus; 5-minute lockout |

| Preoperative, all blocks performed by same physician; neurolocation, nerve stimulator; lumbar plexus localized using approach described by Winnie et al. [64]; presence of block evaluated by pin-prick test in distribution of femoral, obturator, and lateral femoral cutaneous nerve, 15 minutes after administration | General, standardized anesthesia protocol | Not available | PCA, morphine IV 1-mg bolus; 6 minutes lockout; 4-hour limit of 30 mg. If VAS ≥ 5, rescue dose of morphine 2 mg every 5 minutes |

| Preoperative: neurolocation, nerve stimulator; block performed following landmarks of Winnie et al. [64] | General, standardized anesthesia; oral (pre- and postoperative) analgesic protocol | Propacetamol 1 g IV if VAS ≥ 3; piritramide 10 mg IM if VAS remained unchanged after 30 minutes | PCA, morphine IV, 1.5 mg bolus; 8 minutes lockout |

| Postoperative (in operating room), neurolocation, nerve stimulator; for femoral nerve block, paravascular landmarks described by Winnie et al. [64]; psoas compartment block using posterior approach to lumbar plexus at L3 | General, standardized anesthesia and oral (pre- and postoperative) analgesic protocol | Propacetamol 2 g IV every 6 hours; indomethacin 50 mg intrathecally at end of surgery, then 25 mg by mouth every 12 hours | PCA, morphine IV, 1-mg bolus; 10 minutes lockout; if VAS > 3, increased to 1.5 mg; 7 minutes lockout |

| Preoperative, neurolocation, nerve stimulator; block administered as single-injection posterior lumbar plexus block, using approach described by Winnie et al. [64] | General, standardized anesthesia and oral (pre- and postoperative) analgesic protocol. | Propacetamol 2 g IV every 8 hours; ibuprofen 400 mg by mouth every 8 hours | PCA, morphine IV, 1-mg bolus; 6 minutes lockout and 4-hour maximum of 40 mg |

| Preoperative, neurolocation, nerve stimulator; block performed following landmarks described by Winnie et al. [64] | General, standardized anesthesia protocol | Not available | Diclofenac, 75 mg IM, if VAS > 3; if necessary, 0.1 mg/kg morphine added after 30 minutes |

* For the first postoperative day; †authors did not specify dosage; ASA = American Society of Anesthesiologists; PCA = patient-controlled anesthesia; PACU = postanesthesia care unit; IV = intravenous; IM = intramuscular; OA = osteoarthritis.

Fig. 2A–B.

The risk of bias for (A) randomized controlled trials comparing use of LIA versus with placebo/control and (B) PNB versus with placebo/control are shown. LIA = local infiltration analgesia; PNB = peripheral nerve block.

Data Extraction

For each eligible study, data were extracted by two independent reviewers (JHJA, CCW) in duplicate and entered in a standardized data extraction spreadsheet. Disagreement was resolved by input from a third reviewer (PJB). Data items extracted included study characteristics, patient demographics, THA approach, components and administration methods of interventions and comparisons, anesthesia protocol, oral analgesic protocol (pre- and postoperative), and description of rescue analgesia. Additionally, all data pertaining to outcomes were retrieved.

Outcome Measures

The first outcome reported was patient postoperative pain score at rest, measured with a VAS or numerical rating scale at 24 hours. Evidence supports the validity of both pain scales as measures of pain intensity, with relatively small differences in sensitivity and responsiveness between scales in reaction to experimentally induced pain [16]. All pain scores were converted to a continuous 0-to-10 scale (ie, if a VAS of 0–100 mm was used, it was converted to a 0–10 scale) for uniformity of the analysis. When pain scores were reported graphically and the corresponding author did not provide the requested information, the values were derived by extrapolation using Digitizelt software (http://www.digitizeit.de); I. Bormann, Braunschweig, Germany); this method was followed for both outcomes. The second outcome was cumulative opioid consumption (mg) 24 hours after surgery, reported as total intravenous morphine. If the selected RCTs used a different opioid for rescue analgesia, the equivalent intravenous morphine was calculated according to opioid equianalgesic equations [22].

Quality Assessment

Two reviewers (JHJA, PJB) independently assessed the methodologic quality of each RCT’s application of the recommended Cochrane Collaboration risk assessment tool [25]. Some modifications and additions were made to this tool. We assessed blinding at three different levels (participants, personnel/care providers, and assessors), and added three items that may have acted as potential sources of bias (patient baseline characteristics, surgical characteristics, and standardized anesthesia/oral analgesic protocol). The quality of evidence was judged using the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) framework [60].

Author Contact

We attempted to clarify any uncertainties in results (incomplete data presentation, values shown graphically without descriptions of original data, values provided as median and range) or methodology by corresponding with the authors. The source of the original data (author, researcher) was contacted by e-mail for unclear bias domains, missing information in the primary outcomes, or when questions arose during our analyses. On contact one of the authors provided an additional study [10].

Data Synthesis

If the values for continuous variables were reported as median and as interquartile range (IQR) or total range, the mean value was estimated using the median and the low and high ends of the range for samples smaller than 25; for samples greater than 25, the actual median was used [6]. The mean and SD were estimated from the median and the low and high ends of the range for samples smaller than 15, as range/four for samples from 15 to 70, and as range/six for samples more than 70 [6]. If only an IQR was available, SD was estimated as IQR/1.35 [15, 24].

The SD was imputed if it was not available and the appropriate data that permitted its calculation were not provided. We followed the guidelines for imputing SD provided by the Cochrane Handbook [25]. If studies were missing SD for a specific outcome [31, 34, 37, 57], the SD was obtained from the mean SD of the included studies. This method yielded reliable results when the number of RCTs missing SD was small compared with the total number of RCTs [20].

Five of our included RCTs contained multiple intervention groups. We combined intervention arms in three studies: single-shot and continuous local infiltration analgesia [54]; continuous lumbar plexus block and continuous femoral nerve block [39]; and femoral nerve block and pudendal and paracervical block [7]. For the pairwise meta-analysis, the epidural analgesia arm was excluded for two studies [45, 53]. The combination of intervention arms and exclusion of the epidural analgesia arm was performed according to the Cochrane Collaboration guidelines [25].

Data Analysis

Two types of statistical analyses were used for the extracted data. The first was a pairwise direct meta-analysis comparing use of local infiltration analgesia and peripheral nerve blocks with placebo or control. We reported the pooled weighted mean differences (WMD) for the continuous variables using the inverse-variance method as the outcomes were measured in the same units and scale. All statistical variables were calculated with 95% CIs using a random-effect model, which incorporated between and within study variability. A random-effect model was selected a priori because of the presence of heterogeneity (variation of outcomes between included studies) among trials owing to the different intervention regimens and delivery methods. Heterogeneity was explored using the Q-statistic, with a p value less than 0.05 suggesting significant heterogeneity between trials. The I 2 value, which estimated the proportion of total variability attributable to true between-study differences rather than chance alone, was calculated. We conducted pairwise comparisons using Review Manager (RevMan V. 5.2; http://tech.cochrane.org/revman).

The second statistical comparison involved a network meta-analysis that included all RCTs that compared use of local infiltration analgesia or peripheral nerve blocks with placebo/control, epidural analgesia, and intrathecal morphine. To perform indirect comparison, we conducted random-effects Bayesian network meta-analysis using Markov methods in WinBUGS 1.4.3 (MRC Biostatistics Unit, Cambridge, UK), following methods described by Lu and Ades [38]. We modeled the comparative efficacy of local infiltration analgesia or peripheral nerve blocks as a function of each treatment relative to a reference treatment. We estimated the posterior distribution of all parameters using noninformative priors to limit inference to data derived from the trials at hand (ie, we made no assumptions regarding the efficacy of the drugs from data external to the trials included in our systematic review). We updated the Markov model with 100,000 simulated draws after a burn-in of 1000 iterations. We reported the pairwise difference in mean and 95% credible interval (CrI, or Bayesian CI), and adjusted for multiple arm trials. Additionally, with these effect estimates along with the 95% CrIs for each of the interventions relative to a common comparator, we calculated the probability that each treatment was the most effective of all treatments compared [27].

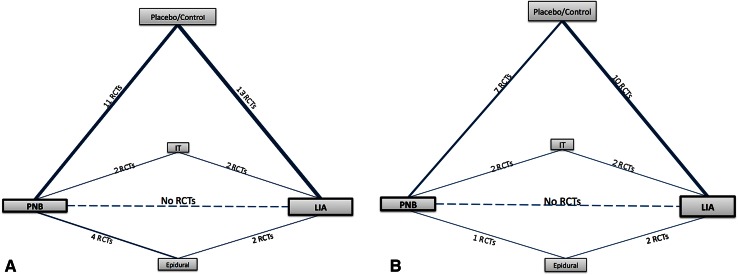

Network Meta-analysis

A network meta-analysis was performed after developing a linkage system of indirect comparisons for patient pain scores and opioid consumption (Fig. 3). In addition to the RCTs included in the two pairwise meta-analyses, Bayesian network meta-analysis included 10 more RCTs [3, 12, 14, 19, 32, 45, 48, 53, 55, 61] comparing use of local infiltration analgesia or peripheral nerve blocks with epidural analgesia or intrathecal morphine. By introducing the additional indirect comparisons (epidural analgesia, intrathecal morphine) we increased the power and precision of the network meta-analysis (Appendix 1. Supplemental material is available with the online version of CORR®).

Fig. 3A–B.

The network diagrams for (A) patient pain scores 24 hours after THA included 32 RCTs (2133 patients), (B) and for cumulative opioid consumption included 23 RCTs (1537 patients). The thickness of the lines is proportional to the number of trials comparing each pair of treatments, and the area of each rectangle is proportional to the number of randomized participants (n = sample size). LIA = local infiltration analgesia; IT = intrathecal morphine; RCTs = randomized controlled trials; PNB = peripheral nerve block.

Additional Analyses

To explore causes of inconsistency, subgroup analyses were performed and specified a priori according to the possible sources of heterogeneity (Table 4). Sensitivity analyses were performed to examine whether results changed when individual trials were excluded in a random sequential fashion. Publication bias was assessed by inspecting funnel plots for each primary outcome.

Table 4.

Possible sources of heterogeneity in included trials

| Sources of heterogeneity | Variable |

|---|---|

| Method | |

| Comparison group | Placebo |

| Control | |

| Blinding | Triple blind: blinding of participants, care providers, and outcome assessors |

| No triple blinding | |

| Intervention | |

| Administration methods | Single shot |

| Continuous infusion | |

| Components | Local anesthetic only |

| Local anesthetic plus adjuvants* | |

| Type of nerve block† | Femoral nerve block |

| Lumbar plexus block | |

| Fascia iliaca compartment block | |

| Psoas compartment block | |

| Outcomes | |

| Opioid for rescue analgesia | Intravenous morphine |

| Opioid equivalents | |

* For local infiltration anesthesia, this subgroup was subdivided into (a) injection containing at least local anesthetic and morphine and (b) injection containing at least local anesthetic and other components without morphine; †only for the meta-analysis comparing peripheral nerve blocks vs placebo/control.

Quality of Evidence

Overall, confidence in the estimates (quality of evidence) for the comparisons of use of local infiltration analgesia and peripheral nerve blocks was low for reduction in postoperative pain scores and reduction in opioid consumption. The confidence was rated down because of imprecision, heterogeneity, and indirectness. Imprecision refers to wide confidence intervals that make evidence users less certain of the effect. Estimates for pain and total opioid consumption had confidence intervals that crossed the line of no effect and therefore included benefit and harm. Heterogeneity (inconsistency) refers to the variability in the results across trials. Statistically, it is reflected by a large value of the I 2 statistics. Indirectness refers to the situation when the available evidence does not directly answer our clinical question. The optimal evidence for our clinical question would be derived from head-to-head RCTs. However, in this network meta-analysis, most of the evidence is derived from indirect comparisons. The quality of evidence was judged using GRADE [60].

Results

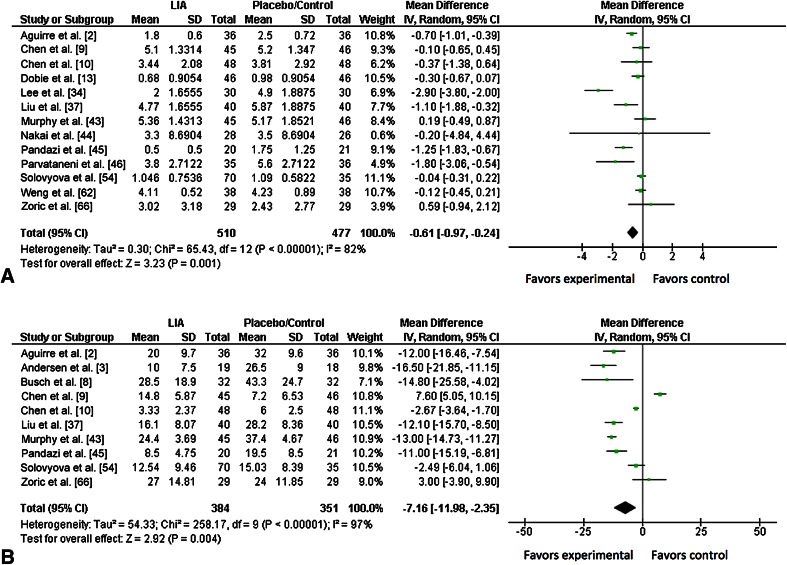

Pairwise Meta-analyses (direct comparison) of Local Infiltration Analgesia

Compared with placebo/control, use of local infiltration analgesia showed lower patient pain scores 24 hours after surgery (WMD, −0.61; 95% CI, −0.97 to −0.24; p = 0.001). Postoperative pain scores were provided in 13 trials [2, 9, 10, 13, 34, 37, 43–46, 54, 62, 66], for a total of 987 patients (510 in the local infiltration analgesia group, 477 in the placebo/control group). There was substantial heterogeneity among studies (I 2 = 82%; p < 0.001) (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4A–B.

The forest plots show the analgesic effect 24 hours after hip arthroplasty, of local infiltration analgesia compared with either placebo or no infiltration (control group) on reducing (A) pain scores and (B) cumulative opioid consumption. The size of each square is proportional to the study’s weight in the meta-analysis and the horizontal lines represent 95% CIs for individual studies. The overall effect estimated was plotted as a diamond and the lateral points of the diamond indicated the 95% CIs of the estimate. LIA = local infiltration analgesia; IV = inverse variance.

Meta-analysis showed that total opioid consumption of patients was lower with use of local infiltration analgesia compared with placebo/control (WMD, −7.16 mg; 95% CI, −11.98 to −2.35; p = 0.004) (Fig. 4B). Ten trials [2, 4, 8–10, 37, 43, 45, 54, 66], including 735 patients (384 in the local infiltration analgesia group, 351 in the placebo/control group), reported opioid consumption at 24 hours after surgery. There was substantial heterogeneity among included studies (I 2 = 97%; p < 0.001).

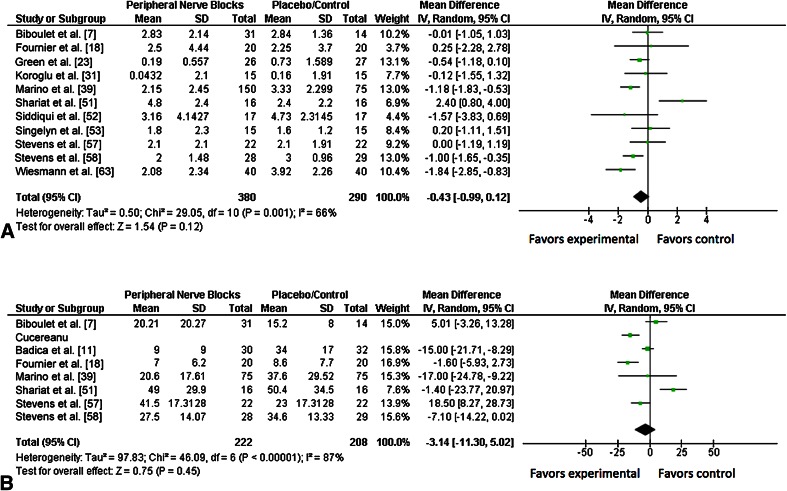

Peripheral Nerve Blocks

Patient-reported pain scores at 24 hours after surgery were no different with use of peripheral nerve blocks or placebo (WMD, −0.43; 95% CI, −0.99 to 0.12; p = 0.12). Data regarding postoperative pain scores were provided in 11 trials [7, 18, 23, 31, 39, 51–53, 57, 58, 63], for a total of 670 patients (380 in the peripheral nerve blocks group, 290 in the placebo/control group). There was moderate heterogeneity among included studies (I 2 = 66%; p = 0.001) (Fig. 5A).

Fig. 5A–B.

The forest plots show the analgesic effect of peripheral nerve blocks compared with placebo or no block (control group), 24 hours after surgery, on reducing (A) pain scores and (B) cumulative opioid consumption as rescue analgesia. The size of each square is proportional to the study’s weight in the meta-analysis and the horizontal lines represent the 95% CIs for individual studies. The overall effect estimated was plotted as a diamond and the lateral points of the diamond indicated the 95% CIs of the estimate. IV = inverse variance.

Similarly, our meta-analysis found no difference in cumulative opioid consumption of patients between the peripheral nerve block and placebo groups (WMD, −3.14 mg; 95% CI, −11.30 to 5.02; p = 0.45) Seven trials [7, 11, 18, 39, 51, 57, 58] including 430 patients (222 in the peripheral nerve blocks group, 208 in the placebo/control group), reported opioid consumption at 24 hours after surgery. There was substantial heterogeneity among included studies (I 2 = 87%; p < 0.001) (Fig. 5B).

Subgroup and Sensitivity Analyses

For local infiltration analgesia meta-analysis, patients in the subgroup given infiltration containing at least local anesthetic and morphine reported a greater treatment effect compared with patients in other subgroups (Table 5). For meta-analysis of peripheral nerve blocks, patients with lumbar plexus block reported a greater treatment effect compared with patients who received other types of peripheral blocks. Continuous nerve blocks were more effective than single-injection blocks as postoperative analgesia methods (Table 6).

Table 5.

Summary of subgroup analyses

| Variable | Pain scores | Cumulative opioid consumption | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test for overall effect | WMD, (95% CI) | I 2 (%) | Test for subgroup differences, p (I 2, %) | Test for overall effect | WMD, (95% CI) | I 2 (%) | Test for subgroup differences p (I 2, %) | |||||

| Number | z | p | Number | z | p | |||||||

| Group | ||||||||||||

| Placebo | 7 | 1.55 | 0.12 | −0.29 (−0.65 to 0.08) | 67 | 0.06 (72.5) | 8 | 2.18 | 0.03 | −6.01 (−11.42 to −0.61) | 97 | 0.58 (0) |

| Control | 6 | 2.88 | < 0.001 | −1.14 (−1.93 to −0.35) | 89 | 3 | 2.31 | 0.02 | −8.54 (−15.79 to −1.28) | 77 | ||

| Blinding | ||||||||||||

| Triple blind* | 8 | 1.96 | 0.05 | −0.29 (−0.59 to 0) | 61 | 0.07 (68.7) | 8 | 1.63 | 0.1 | −4.31 (−9.49 to 0.87) | 97 | 0.005 (87) |

| No triple blinding† | 5 | 2.34 | 0.02 | −1.39 (−2.56 to −0.23) | 90 | 3 | 6.9 | < 0.001 | −11.84 (−15.08 to −8.60) | 23 | ||

| Delivery method‡ | ||||||||||||

| Single shot | 11 | 2.76 | 0.006 | −0.66 (−1.13 to −0.19) | 84 | 0.29 (9.3) | 7 | 2.81 | 0.005 | −7.40 (−12.56 to −2.24) | 95 | 0.78 (0) |

| Continuous | 3 | 1.48 | 0.14 | −0.32 (−0.75 to 0.10) | 79 | 4 | 1.03 | 0.3 | −5.69 (−16.56 to 5.18) | 97 | ||

| Components | ||||||||||||

| Local anesthetic only§ | 5 | 0.98 | 0.33 | −0.23 (−0.68 to 0.23) | 57 | 0.05 (65.8) | 5 | 0.97 | 0.33 | −3.54 (−10.70 to 3.63) | 98 | 0.08 (60) |

| Contains morphine¶ | 6 | 2.78 | 0.005 | −1.33 (−2.27, −0.39) | 88 | 3 | 8.11 | < 0.001 | −10.16 (−11.59 to −8.74) | 0 | ||

| Other combinationsΔ | 2 | 1.11 | 2.78 | −0.70 (−1.09 to −0.30) | 18 | 3 | 1.57 | 0.12 | −6.90 (−15.49 to 1.69) | 90 | ||

| Opioid for rescue analgesia | ||||||||||||

| Intravenous morphine | 6 | 2.54 | 0.01 | −0.55 (−0.97 to −0.12) | 70 | 0.62 (0) | 7 | 4.55 | < 0.001 | −9.02 (−12.91 to −5.14) | 82 | 0.15 (52) |

| Equivalents | 7 | 2.31 | 0.02 | −0.74 (−1.36 to −0.11) | 86 | 4 | 0.9 | 0.37 | −3.16 (−10.04 to 3.72) | 96 | ||

* Blinding of participants, care providers, and outcome assessors; †double-blind and single-blind studies; ‡ trial of Solovyova et al. [54] was included in both subgroups. This trial had two intervention groups—single-shot local infiltration analgesia and continuous-infusion local infiltration analgesia—which were combined for the overall meta-analysis, as recommended by the Cochrane Handbook. Data from the control group were used twice. This method yielded similar results to the overall meta-analysis; §local infiltration analgesia containing only local anesthetic; ¶injection containing, at minimum, local anesthetic and morphine; Δinjection containing, at minimum, local anesthetic and other components, without morphine; WMD = weighted mean difference.

Table 6.

Peripheral nerve blocks compared with placebo/control

| Variable | Pain scores | Cumulative opioid consumption | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test for overall effect | WMD (95% CI) | I 2 (%) | Test for subgroup differences; p (I 2, %) | Test for overall effect | WMD (95% CI) | I 2 (%) | Test for subgroup differences; p (I 2, %) | |||||

| Number | z | p | Number | z | p | |||||||

| Comparison group | ||||||||||||

| Placebo | 4 | 1.00 | 0.32 | 0.62 (−0.59 to 1.82) | 56 | 0.44 (79.4) | 3 | 0.73 | 0.47 | 5.69 (−9.59 to 20.97) | 84 | 0.11 (59) |

| Control | 7 | 3.51 | < 0.001 | −0.84 (−1.31 to −0.37) | 46 | 4 | 1.85 | 0.06 | −8.66 (−17.85 to 0.53) | 84 | ||

| Blinding | ||||||||||||

| Triple-blind* | 3 | 0.37 | 0.71 | 0.32 (−1.36 to 2.00) | 87 | 0.25 (23.9) | 3 | 0.28 | 0.78 | −1.33 (−10.59 to 7.94) | 58 | 0.72 (0) |

| No triple blinding† | 8 | 2.66 | 0.008 | −0.71 (−1.23 to −0.19) | 41 | 4 | 0.65 | 0.51 | −4.17 (−16.70 to 8.36) | 93 | ||

| Delivery method‡ | ||||||||||||

| Single shot | 8 | 0.79 | 0.43 | −0.28 (−0.98 to .42) | 71 | 0.40 (0) | 6 | 0.16 | 0.87 | −0.69 (−9.13 to 7.76) | 85 | 0.005 (87) |

| Continuous | 3 | 1.61 | 0.11 | −0.81 (−1.79 to 0.18) | 46 | 1 | 4.28 | < 0.001 | −17.00 (−24.78 to −9.22) | Not available§ | ||

| Components | ||||||||||||

| Local anesthetic only | 5 | 1.24 | 0.21 | −0.36 (−0.93 to 0.21) | 23 | 0.74 (0) | 3 | 5.99 | < 0.001 | −15.14 (−20.10 to −10.19) | 0 | 0.0004 (91) |

| Local anesthetic plus adjuvants | 6 | 1.16 | 0.25 | −0.55 (−1.47 to 0.38) | 78 | 4 | 0.66 | 0.51 | 2.95 (−5.84 to 11.74) | 84 | ||

| Opioid for rescue analgesia | ||||||||||||

| IV morphine | 7 | 0.02 | 0.98 | 0.01 (−0.84 to 0.86) | 67 | 0.07 (69.7) | 6 | 0.16 | 0.87 | −0.69 (−9.13 to 7.76) | 85 | 0.005 (87) |

| Equivalents | 4 | 3.04 | 0.002 | −0.97 (−1.59 to −0.35) | 52 | 1 | 4.28 | < 0.001 | −17.00 (−24.78 to −9.22) | Not available§ | ||

| Type of nerve block | ||||||||||||

| Femoral nerve block | 4 | 2.26 | 0.02 | −0.78 (−1.45 to −0.10) | 62 | 0.01 (73.2) | 3 | 0.47 | 0.64 | 0.90 (−2.82 to 4.61) | 75 | 0.03 (65) |

| Lumbar plexus block | 3 | 3.27 | 0.001 | −1.04 (−1.67 to −0.42) | 0 | 2 | 2.69 | 0.007 | −7.77 (−13.44 to −2.10) | 0 | ||

| Fascia iliaca compartment block | 2 | 1.76 | 0.08 | 0.85 (−0.10 to 1.81) | 82 | 3 | 1.70 | 0.09 | −4.71 (−10.15 to 0.73) | 93 | ||

| Psoas compartment block | 2 | 1.66 | 0.10 | −0.54 (−1.18 to 0.10) | Not available§ | 1 | 2.35 | 0.2 | −5.95 (−10.9 1 to −0.99) | Not available§ | ||

* Blinding of participants, care providers, and outcome assessors; †double-blind and single-blind studies; ‡trials of Marino et al. [39] and Biboulet et al. [7] were included in two subgroups each for the cumulative opioid outcome and eliminated for the pain scores outcome. These trials had two intervention groups (continuous femoral nerve block and continuous lumbar plexus block [39]; femoral nerve block and psoas compartment block [7]) that were combined for the overall meta-analysis as recommended by the Cochrane Handbook. The data from the control group were used twice for the opioid outcome. This method yielded similar results to the overall meta-analysis for cumulative opioid consumption. Removing these trials from the subgroup analysis yielded similar results to the overall meta-analysis for pains scores; WMD = weighted mean difference; §only one study was included in the respective subgroup, therefore the heterogeneity coefficient could not be obtained for this subgroup.

Sensitivity analyses did not substantively change the results. Removal of any individual RCT in a random sequential fashion led to no significant change in the direction or magnitude of the effect. Publication bias was not evident on inspection of the funnel plots, however, evaluation of publication bias was not reliable in the presence of heterogeneity.

Network Meta-analysis

We found no differences between peripheral nerve blocks and local infiltration analgesia in terms of patient-reported postoperative pain scores (WMD, −0.36; 95% CI, −1.06 to 0.31 and cumulative opioid consumption at 24 hours after THA (WMD, −4.59 mg; 95% CI, −9.35 to 0.17). In addition, compared with peripheral nerve blocks, use of local infiltration analgesia had a greater probability of being ranked most effective for both outcomes. Rank-order analysis showed that local infiltration analgesia was the most effective treatment in 12% of the simulations for postoperative pain scores and most effective in 32% of the simulations for opioid consumption. Peripheral nerve block was the best intervention in only 0.7% of the simulations for pain scores and the most effective for 0.3% of the simulations of opioid requirements.

Discussion

The THA is one of the most frequently performed and successful surgical procedures in modern medicine and has been called the “operation of the century” [33, 50]. Nevertheless, management of postoperative pain after THA often remains insufficient, and there is no agreement regarding the preferred postoperative analgesic intervention [17, 33, 43, 50]. With the emergence of new regional techniques, which have been found to be safe and effective [21, 65], comes the need to compare the efficacy of these new techniques. However, the comparative analgesic efficacy of these interventions for pain management after THA remains to be seen, as evidence from head-to-head, direct comparative RCTs is lacking. The objective of our investigation therefore was to compare the analgesic effects of local infiltration analgesia and peripheral nerve blocks through indirect methods.

Our findings must be considered in light of several limitations. The first is regarding the methods used in the study. Our search strategy excluded grey literature and non-English language studies. The main limitations of the network meta-analysis methodology emerge when trials have different populations or characteristics that lead to inconsistency (ie, different results of trials in the same pairwise comparison) or when each pairwise comparison has unique characteristics (eg, different populations) leading to differences between direct and indirect comparisons (ie, incoherence). We encountered high heterogeneity defined by the I 2 index, most of which was inherent to the intervention treatments. There was variability among studies in administration methods of local infiltration analgesia and peripheral nerve blocks, time of infiltration, type of nerve block, injection components and respective doses, and anesthesia/analgesic protocols. Different patient self-reported pain scores (VAS, numerical rating scale) and measurement scales (VAS, 0–10, VAS, 0–100 mm) were used in the RCTs included. Additionally, different opioids were administered as rescue analgesics, and conversion to morphine equivalents may have caused inaccurate results. A random-effects model was selected to incorporate heterogeneity among studies and heterogeneity was addressed with a priori subgroup analysis following established criteria [59]. Some values were imputed and converted from graphic values to numeric values owing to the absence of availability of numerical representation of graphic data. Sensitivity analyses however, showed that our conclusions were not affected by removing any trial, making this of less concern overall. Imprecision (wide CIs that included appreciable benefit and harm) and indirectness (lack of comparison of head-to-head trials) further lowered confidence in the ranking superiority of one intervention over the other. Finally, probability ranking should be interpreted with caution. Although it provides the probability that a certain intervention is the winner or the most effective, it does not provide any information regarding the magnitude of the effect (the absolute benefit over the other interventions) or the risk of bias. Ranking probability results does not represent a clinically significant difference and hides the overall quality of the evidence.

The limitations of our study highlight important deficits in the current standard of orthopaedic evidence. Our systematic review showed a scarcity of large RCTs comparing peripheral nerve blocks and local infiltration analgesia with other postoperative analgesic regimens and absence of direct comparative RCTs between interventions. Furthermore, many of the included RCTs lacked depth of reporting their outcomes in a systematic manner. These RCTs illustrated values for pain scores and opioid consumption in a graphic way without appropriate numerical representation. In other cases, studies failed to provide values that described the variability of the outcomes (SD, range, interquartile range). More uniform patient-reported outcome data including pain scales, rescue analgesics used, postoperative functional scores, use of standardized anesthesia protocols, multimodal perioperative pain protocols, and reporting of the efficacy of delivery of postoperative analgesic interventions will be mandatory moving forward to provide consistently useful information. As a specialty, orthopaedics can derive greater understanding of new analgesic interventions and techniques with the initiation of large, well-designed RCTs; otherwise, decisions for patient care will be driven by forms of evidence with greater potential for bias and heterogeneity, such as retrospective reviews. Although there were limitations in using this approach, we were able to include 35 RCTs and 2296 patients by a series of direct and indirect statistical comparisons. We believe this strengthens the interpretation of our data for surgeons making evidence-based decisions regarding which analgesic intervention to use after THAs.

We found local infiltration analgesia to be superior to placebo/control for patient-reported postoperative pain scores at rest and cumulative opioid consumption. By contrast, patients in the peripheral nerve blocks groups reported no differences in pain scores and in opioid requirements when compared with those in the placebo/control groups at 24 hours after THA. The lumbar plexus block showed a greater treatment effect in reducing pain scores and total opioid consumption compared with other types of peripheral blocks. Our data also showed that continuous nerve blocks do not reduce pain scores compared with single injection blocks for postoperative analgesia. These results were somewhat surprising as our experience with peripheral nerve blocks has been positive. We have been using peripheral nerve blocks during THAs and TKAs for more than a decade. These blocks have been the cornerstone of our multimodal anesthetic pathway, and have led to a positive patient experience, improved inpatient rehabilitation, and decreased length of stay. Our experience is supported by studies that showed that that nerve blocks can provide superior pain control with fewer side effects and decrease hospital length of stay compared with epidural regional anesthesia [28, 47]. However, our experience also shows that the results obtained from peripheral nerve blocks postoperatively are highly technique dependent. Today most peripheral nerve blocks are inserted using ultrasound guidance to reliably determine the position of the needle before injection or placement of the catheter. The variability in technique could account for the results in our study.

Local infiltration analgesia is an accepted technique for postoperative pain management after TKA. Gibbs et al. [21] concluded that there is sufficient evidence indicating that local infiltration analgesia reduces postoperative pain after TKA. In contrast, there are mixed opinions and conflicting results regarding the use of local infiltration analgesia after THA [54, 65]. Marques et al. [41] concluded that inclusion of local anesthetic infiltration in a multimodal anesthesia regimen is effective in reducing short-term pain and hospital stay for patients undergoing THAs and TKAs. However, Yin et al. [65] stated that although local infiltration analgesia is a potential approach for reducing pain scores and analgesic consumption during the early postoperative stages without increasing risk of adverse effects, there was no indication that it could help in the later stages of recovery. Furthermore, some authors [28, 54] stated that some of the observed analgesic effects of local infiltration analgesia are attributable to deficiency of a rigorous study design that may have led to bias in reporting results. This bias and analgesic efficacy of local infiltration analgesia could be attributed to a lack of comprehensive multimodal analgesia in some of the included studies. In contrast, local infiltration analgesia is an accepted technique for postoperative pain management after TKA. Gibbs et al. [21] concluded that there is sufficient evidence showing local infiltration analgesia reduces postoperative pain after TKA. Unfortunately, previous systematic reviews regarding the efficacy of local infiltration analgesia as an analgesic treatment after THA have been limited by low number of available RCTs and the variability of design and quality of included studies [29, 42].

Using the novel statistical network meta-analysis approach, we found no difference between local infiltration analgesia and peripheral nerve blocks in terms of cumulative opioid use and pain scores 24 hours after surgery, although we found that local infiltration analgesia had a greater probability of being ranked first in efficacy for patient outcomes. Local infiltration analgesia does not offer superior pain control than peripheral nerve blocks after hip arthroplasty during the early postoperative period. Nevertheless, the confidence in the estimates is low. This means that future investigations may show different estimates and perhaps future direct head-to-head trials may offer different conclusions in unique patient populations. Users of the evidence derived from this network meta-analysis should acknowledge the confidence warranted by data and convey the level of uncertainty to patients when they counsel them regarding their choice for postoperative pain control.

With minimal if any difference observed in analgesic efficacy among local infiltration analgesia and peripheral nerve blockades, it may be prudent to place greater emphasis on other factors in the decision-making process, namely cost and intervention-specific complications. Local infiltration analgesia has been shown to be a cost-effective treatment option compared with current clinical analgesic regimens (which include peripheral nerve blocks) in primary THAs and TKAs, with the evidence being stronger for hip replacements [40]. Furthermore, local infiltration analgesia appears to be the most economic option according to the data provided by a cost-effective study of two RCTs [40] that compared current clinical analgesia regimens in primary THAs and TKAs. Reduction of as much as USD 350 per hip replacement has been reported by use of local infiltration analgesia instead of peripheral nerve blockade [56]. It is crucial that the theoretical framework for debating whether to use local infiltration analgesia or nerve blockade incorporates intervention-specific complications, safety, and surgeons’ expertise. Because the frequency and magnitude of opioid-related complications are dose-dependent, a multimodal perioperative regimen that reduces the opioid requirements is desired. Failure to provide adequate analgesia delays participation in early physical rehabilitation that is critical to achieve a functional recovery and reduced time to hospital discharge in patients who have hip replacement. Our systematic review and network meta-analysis showed similar analgesic efficacy between local infiltration analgesia and peripheral nerve blocks, in terms of patient-reported pain scores and total opioid consumption at 24 hours after primary THA. Attributable in large part to the network meta-analysis technique, to the best of our knowledge, our review is the most comprehensive summary of the available evidence and evaluation of local infiltration analgesia versus peripheral nerve blocks as an analgesic approach for patients undergoing primary THA. This challenging technique is rarely described in the orthopaedic literature [24, 26] and could prove particularly valuable in this field where large RCTs are relatively rare and rapidly changing technology further limits head-to-head investigation of interventional materials. The findings of our study support the use of local infiltration analgesia as an alternative to peripheral nerve blocks as an analgesic intervention after primary THA.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

We thank Victor Montori MD, and Colin West MD (both from the Division of Internal Medicine, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, USA) for their contributions to the methodology and statistical analyses used in our investigation. We also thank Patricia Erwin (Reference of Preventive Department, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, USA) for assistance in defining the search strategy for the systematic review.

Footnotes

One of the authors certifies that he (RJS), or a member of his or her immediate family, has or may receive payments or benefits, during the study period, an amount of USD 10,000-USD 100,000, from Biomet Inc (Warsaw, IN, USA).

All ICMJE Conflict of Interest Forms for authors and Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research ® editors and board members are on file with the publication and can be viewed on request.

Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research ® neither advocates nor endorses the use of any treatment, drug, or device. Readers are encouraged to always seek additional information, including FDA approval status, of any drug or device before clinical use.

Each author certifies that his or her institution approved the human protocol for this investigation, and that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research, and that informed consent for participation in the study was obtained.

This work was performed at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, USA.

References

- 1.Ades AE, Sculpher M, Sutton A, Abrams K, Cooper N, Welton N, Lu G. Bayesian methods for evidence synthesis in cost-effectiveness analysis. Pharmacoeconomics. 2006;24:1–19. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200624010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aguirre J, Baulig B, Dora C, Ekatodramis G, Votta-Velis G, Ruland P, Borgeat A. Continuous epicapsular ropivacaine 0.3% infusion after minimally invasive hip arthroplasty: a prospective, randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled study comparing continuous wound infusion with morphine patient-controlled analgesia. Anesth Anal. 2012;114:456–461. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e318239dc64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andersen KV, Pfeiffer-Jensen M, Haraldsted V, Soballe K. Reduced hospital stay and narcotic consumption, and improved mobilization with local and intraarticular infiltration after hip arthroplasty: a randomized clinical trial of an intraarticular technique versus epidural infusion in 80 patients. Acta Orthop. 2007;78:180–186. doi: 10.1080/17453670710013654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andersen LJ, Poulsen T, Krogh B, Nielsen T. Postoperative analgesia in total hip arthroplasty: a randomized double-blinded, placebo-controlled study on peroperative and postoperative ropivacaine, ketorolac, and adrenaline wound infiltration. Acta Orthop. 2007;78:187–192. doi: 10.1080/17453670710013663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Apfelbaum JL, Chen C, Mehta SS, Gan TJ. Postoperative pain experience: results from a national survey suggest postoperative pain continues to be undermanaged. Anesth Analg. 2003;97:534–540. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000068822.10113.9E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baidya DK, Khanna P, Maitra S. Analgesic efficacy and safety of thoracic paravertebral and epidural analgesia for thoracic surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2014;18:626–635. doi: 10.1093/icvts/ivt551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Biboulet P, Morau D, Aubas P, Bringuier-Branchereau S, Capdevila X. Postoperative analgesia after total-hip arthroplasty: comparison of intravenous patient-controlled analgesia with morphine and single injection of femoral nerve or psoas compartment block. a prospective, randomized, double-blind study. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2004;29:102–109. doi: 10.1097/00115550-200409002-00194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Busch CA, Whitehouse MR, Shore BJ, MacDonald SJ, McCalden RW, Bourne RB. The efficacy of periarticular multimodal drug infiltration in total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468:2152–2159. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-1198-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen DW, Hsieh PH, Huang KC, Hu CC, Chang YH, Lee MS. Continuous intra-articular infusion of bupivacaine for post-operative pain relief after total hip arthroplasty: a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study. Eur J Pain. 2010;14:529–534. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2009.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen DW, Hu CC, Chang YH, Lee MS, Chang CJ, Hsieh PH. Intra-articular bupivacaine reduces postoperative pain and meperidine use after total hip arthroplasty: a randomized, double-blind study. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29:2457–2461. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2013.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cucereanu Badica IG, Pavelescu D, Badica L, Barbilian R, Grintescu I. The efficacy of fascia iliaca compartment block (FICB) for postoperative analgesia after hip arthroplasty (HA). Reg Anes. Pain Med. 2010;35:E80. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dauri M, Celidonio L, Fabbi E, Nahmias S, Faria S, Coniglione F, Silvi MB. Comparing continuous lumbar plexus block, continuous epidural block and continuous lumbar plexus block with a parasacral sciatic nerve block on post-operative analgesia after hip arthroplasty. J Anes Clin Res. 2011;2:177. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dobie I, Bennett D, Spence DJ, Murray JM, Beverland DE. Periarticular local anesthesia does not improve pain or mobility after THA. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470:1958–1965. doi: 10.1007/s11999-012-2241-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duarte LT, Beraldo PS, Saraiva RA. [Effects of epidural analgesia and continuous lumbar plexus block on functional rehabilitation after total hip arthroplasty][in Portuguese] Rev Bras Anestesiol. 2009;59:531–544. doi: 10.1016/S0034-7094(09)70078-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Engelman E, Marsala C. Efficacy of adding clonidine to intrathecal morphine in acute postoperative pain: meta-analysis. Br J Anaesth. 2013;110:21–27. doi: 10.1093/bja/aes344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ferreira-Valente MA, Pais-Ribeiro JL, Jensen MP. Validity of four pain intensity rating scales. Pain. 2011;152:2399–2404. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Filos KS, Lehmann KA. Current concepts and practice in postoperative pain management: need for a change? Eur Surg Res. 1999;31:97–107. doi: 10.1159/000008627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fournier R, Van Gessel E, Gaggero G, Boccovi S, Forster A, Gamulin Z. Postoperative analgesia with “3-in-1” femoral nerve block after prosthetic hip surgery. Can J Anaesth. 1998;45:34–38. doi: 10.1007/BF03011989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frassanito L, Rodola F, Concina G, Messina A, Chierichini A, Vergari A. The efficacy of the psoas compartment block versus the intrathecal combination of morphine, fentanyl and bupivacaine for postoperative analgesia after primary hip arthroplasty: a randomized single-blinded study. Eur Med Pharmacol Sci. 2008;12:117–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]