Abstract

Osmanthus fragrans is an ornamental and economically important plant known for its magnificent aroma, and the most important aroma-active compounds in flowers are monoterpenes, mainly β-ocimene, linalool and linalool derivatives. To understand the molecular mechanism of monoterpene production, we analyzed the emission and accumulation patterns of these compounds and the transcript levels of the genes involved in their biosynthesis in two O. fragrans cultivars during flowering stages. The results showed that both emission and accumulation of monoterpenes varied with flower development and glycosylation had an important impact on floral linalool emission during this process. Gene expression demonstrated that the transcript levels of terpene synthase (TPS) genes probably played a key role in monoterpene production, compared to the genes in the MEP pathway. Phylogenetic analysis showed that OfTPS1 and OfTPS2 belonged to a TPS-g subfamily, and OfTPS3 and OfTPS4 clustered into a TPS-b subfamily. Their transient and stable expression in tobacco leaves suggested that OfTPS1 and OfTPS2 exclusively produced β-linalool, and trans-β-ocimene was the sole product from OfTPS3, while OfTPS4, a predictive sesquiterpene synthase, produced α-farnesene. These results indicate that OfTPS1, OfTPS2, and OfTPS3 could account for the major floral monoterpenes, linalool and trans-β-ocimene, produced in O. fragrans flowers.

Keywords: Osmanthus fragrans, MEP pathway, terpene synthase, monoterpenes, glycosylation

Introduction

Sweet osmanthus (Osmanthus fragrans Lour.), belonging to the Oleaceae family, is a well-known ornamental and economically important, aromatic woody plant, with the flower having a long history in China. Horticultural cultivars have spread throughout Thailand, India, and the Caucasus region (Baldermann et al., 2010). Because of its extremely powerful and unique aroma, flowers and the essential oils of O. fragrans are in high demand for the production of expensive perfumes, flavorings and cosmetics (Wang et al., 2009; Cai et al., 2014). The fresh flowers are very rich in floral volatiles, including terpenoids, aromatic compounds, C6 compounds and esters. The qualitative and quantitative variability of these compounds in flowers usually depends on the cultivar and developmental stage (Li et al., 2008; Cao et al., 2009; Sun et al., 2012; Xin et al., 2013). The terpenoids, including β-ionone, β-ocimene, β-linalool, and linalool derivatives, have been detected as dominant components of fresh flower volatiles and essential oils (Wang et al., 2009; Sun et al., 2012; Xin et al., 2013), and are important in the aroma formation of O. fragrans (Cai et al., 2014). Of the terpenes, β-ionone is ubiquitous in O. fragrans flowers and its biosynthesis has been reported at the molecular level (Baldermann et al., 2010; Han et al., 2014). However, the molecular mechanism for the formation of monoterpenes such as β-ocimene and linalool in O. fragrans is not clear.

In plants, monoterpenes are mainly synthesized through the plastidial methylerythritol 4-phosphate (MEP) pathway, providing terpene precursors isopentenyl diphosphate (IPP) and its allylic isomer, dimethylallyl diphosphate (DMAPP; Dudareva et al., 2013). Quantitative variation in monoterpene production can be controlled by substrate flux through the MEP pathway (Munoz-Bertomeu et al., 2006; Battilana et al., 2011; Külheim et al., 2011). The first step in the MEP pathway is the condensation of pyruvate and D-glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate (G3P) to 1-deoxy-D-xylulose 5-phosphate (DXP; Dudareva et al., 2013). The first enzyme, DXP synthase (DXS), has been considered the rate-limiting enzyme for the MEP pathway flux, because of the close correlation between the gene expression and the content of plastid isoprenoids such as monoterpenes and carotenoids (Estévez et al., 2001; Xie et al., 2008; Battilana et al., 2009). The second and sixth enzyme in the pathway, DXP reductoisomerase (DXR) and 4-hydroxy-3-methylbut-2-en-1-yl diphosphate synthase (HDS), are also potential regulatory control points (Mahmoud and Croteau, 2001; Carretero-Paulet et al., 2006; Külheim et al., 2011). However, the rate-limiting role of each of these enzymes in controlling the pathway flux appears to vary among plants (Cordoba et al., 2009).

Under the catalytic action of geranyl pyrophosphate synthase (GPPS), IPP, and DMAPP are condensed head-to-tail to produce geranyl diphosphate (GPP), the monoterpene substrate (Dudareva et al., 2013). Catalysis of this linear precursor, GPP, to a broad variety of monoterpenes is by the terpene synthase (TPS) family (Degenhardt et al., 2009). TPS enzymes from different plant species have distinct phylogenetic relationships and have been classified into seven subfamilies, designated TPS-a to TPS-g (Chen et al., 2011). Despite intriguing differences between the subfamilies, there are three conserved motifs: an arginine-rich N-terminal RR(x8)W motif required for cyclization of the GPP substrate; an aspartate-rich DDxxD motif that interacts with divalent metal (usually Mg2+ or Mn2+) ions involved in positioning the substrate for catalysis, and (N, D)Dxx(S,T)xxxE, required for second metal ion binding (Degenhardt et al., 2009). The RR(x8)W motif is involved in producing cyclic monoterpenes, and is absent in TPSs that produce acyclic products (Chen et al., 2011). Many TPSs have the ability to produce multiple terpenes from a single prenyl diphosphate substrate in vitro (Martin et al., 2010; Green et al., 2012; Nieuwenhuizen et al., 2013) or in vivo (Davidovich-Rikanati et al., 2008; Green et al., 2012). For example, the occasional complex terpene blend has been found in Arabidopsis thaliana and Medicago truncatula, often produced only by a limited number of multiproduct TPS enzymes (Tholl et al., 2005; Garms et al., 2010). To date, TPSs have been identified and characterized in many plants, including Antirrhinum majus (Dudareva et al., 2003; Nagegowda et al., 2008), Actinidia species (Nieuwenhuizen et al., 2009; Green et al., 2012) and Vitis vinifera (Martin et al., 2010). Despite monoterpenes making a significant contribution to the floral aroma and being rich in O. fragrans flowers, little is known about the TPS genes responsible for production of the major monoterpenes.

The biosynthetic monoterpenes are able to undergo complex processes of storage and conversion, which lead to the inconsistency between monoterpene release and gene transcript level (Chen et al., 2010; Green et al., 2012). Glycosides are a potential source of aroma and flavor compounds, and play important roles in controlling the release of the floral volatiles in flowers and fruit (Schwab et al., 2015). The glycoside volatiles are odorless and could release free aroma volatiles under the hydrolysis of β-glucosidase (Yauk et al., 2014; Schwab et al., 2015). They are highly valued in the flavor industry for enhancing the flavor and quality of grape wine and tea, and modifying the overall aroma during maturation, storage and processing in fruit (Birtić et al., 2009; Garcia et al., 2013; Yauk et al., 2014; Ohgami et al., 2015). In flowers, the organoleptic aroma contributed by free volatiles and the content of essential oil composed of non-glycoside volatiles accumulating in fresh flowers have received more attention compared to the few studies on the volatile glycoside (Picone et al., 2004; Green et al., 2012). It has been reported that glycosidically bound volatiles are more abundant than the free forms and are potentially a major source of aroma in flowers (Aurore et al., 2011; Wen et al., 2014; Yauk et al., 2014). Yang et al. (2005) found that β-D-glucosidase hydrolysis in fresh O. fragrans flowers enhanced the mass fractions of monoterpene volatiles. However, further research is needed on the glycoside monoterpenes in O. fragrans. Moreover, release of the bound volatile aglycones is dependent on flower development (Reuveni et al., 1999). Therefore, the connection between different forms of volatiles is fundamental for understanding the molecular mechanism of monoterpene biosynthesis.

Here, we give a detailed analysis of the emission and accumulation of floral monoterpenes in two O. fragrans cultivars during flowering. A total of 18 genes, including 13 MEP pathway genes from DXS to IDI, one GPPS and four TPS genes, were obtained by transcriptome sequencing and their expression levels were analyzed by real-time qPCR. Intriguing differences were found in the transcript levels of four TPSs. Furthermore, functional characterization of TPSs and their involvement in major monoterpene production in O. fragrans flowers are described. This work provides a better understanding of the molecular mechanism of monoterpene biosynthesis, and will also help in the biotechnological enhancement and modification of aroma in O. fragrans.

Materials and Methods

Plant Materials

The ‘Liuye Jingui’ (abbreviated as ‘Liuye’) and ‘Gecheng Dangui’ (abbreviated as ‘Gecheng’) cultivars of O. fragrans were grown in the campus nursery of Huazhong Agriculture University in Wuhan, China. Flower opening in O. fragrans was divided into four stages (Zou et al., 2014): tight bud stage (S1); initial flowering stage (S2); full flowering stage (S3); and late full flowering stage (S4). Flowers were harvested at about 10 a.m. in October 2013. Each sample at each flowering stages was separated into two parts. One was directly used for headspace volatile analysis, and the other was immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen for volatile solvent and glycoside extraction, and RNA extraction.

SPME Collection and Solvent Extraction

The released floral volatiles were collected by solid-phase microextraction (SPME; Cai et al., 2014). In triplicate, 2 g fresh flowers were placed into a 20 ml capped SPME vial and incubated at 25 ± 2°C for 30 min. SPME fiber (50/30 μm DVB/CAR/PDMS on a 2 cm Stable Flex fiber, Supelco Inc. Bellefonte, PA, USA) was then exposed to the headspace of the capped vial for 30 min. The fiber was injected manually and desorbed in the injection port of the gas chromatograph (GC) with helium as the carrier gas. The fiber was desorbed for 5 min at 250°C in splitless mode. Before each set of samples was assayed, the fiber was conditioned for 1 h at 250°C in the injection port of the GC-MS and a fiber blank recorded.

The accumulated free floral volatiles were collected by solvent extraction (Green et al., 2012). In triplicate, 2 g frozen flowers, harvested at the equivalent time points to the SPME sampling, were ground to a fine powder in liquid nitrogen, transferred to a 50 ml centrifuge tube and extracted twice with 10 ml pentane/Et2O (1:1 v/v) for 30 min with gentle shaking. The two extractions were combined and stored overnight at -20°C. The following day, the upper solvent layer was carefully separated from the lower frozen water layer and reduced to 2 ml under a gentle stream of nitrogen. The concentrated extract, with 47.3 ng/μl cyclohexanone added as internal standard, was passed through a column of anhydrous MgSO4 to remove any remaining water, and then injected into the GC.

Glycoside Extraction

Glycoside analysis was carried out according to Green et al. (2012) with minor modifications. In triplicate 2 g frozen flowers, harvested at the equivalent time points to the headspace sampling, were ground to a fine power in liquid nitrogen, transferred to a 50 ml centrifuge tube and resuspended in 30 ml ddH2O. The sample was centrifuged at 8,000 g for 15 min at 4°C and the supernatant run on a 15 mm × 25 mm i.d. Amberlite XAD-2 column (Supelco, Bellefonte, PA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, at the rate of 3 ml/min. Soluble sugars and acids were removed with 40 ml water and free volatiles by the addition of 40 ml pentane/Et2O (1:1 v/v). Bound glycosides were eluted with 20 ml methanol and evaporated to dryness in a rotary evaporator. The resulting glycoside pellet was resuspended in 2 ml deglycosylation buffer (200 mM Na2HPO4, 220 mM citric acid, pH 5.0) and re-extracted three times with 1 ml pentane/Et2O (1:1 v/v) to remove any remaining free compounds.

Enzymatic hydrolysis was carried out using β-glucosidase (6 u/mg; Sigma–Aldrich, Co, LLC, USA), dissolved in deglycosylation buffer, at a concentration of 10 mg/ml. The hydrolysis sample was overlaid with 1 ml Et2O and incubated at 40°C for 36 h. Following incubation, the sample was extracted a further three times with 1 ml Et2O. Prior to GC-MS analysis, the pooled extracts, with the addition of 47.3 ng/μl cyclohexanone as internal standard, were passed through a column of anhydrous MgSO4 and reduced to 0.5 ml under a gentle stream of nitrogen.

GC-MS Analysis

The samples of the SPME collected, solvent extracted (1 μl) and glycoside volatiles (1 μl) were separated on a 30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm HP-5 capillary column (Thermo Scientific, Bellefonte, PA, USA). The system was a TRACE GC Ultra GC coupled to a DSQ II mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The GC-MS was performed according to Cai et al. (2014). The GC oven ramp for SPME collected volatiles was at 40°C for 3 min, 3°C/min to 73°C and held for 3 min, 5°C/min to 220°C and held for 1 min. The GC oven ramp for the solvent extracted and glycoside volatiles was at 40°C for 3 min, 3°C/min to 73°C and held for 3 min, 5°C/min to 240°C and held for 10 min. The flow rate of the helium (99.999%) carrier gas was 1.2 ml/min. The transfer line temperature was 280°C. For the mass detector, the ion source temperature was set at 230°C, with electronic impact (EI) mode at 70 eV over the mass range m/z 40–450 amu. A C8–C40 alkane standard solution (Sigma–Aldrich, Co., LLC., USA) was analyzed regularly to provide references for calculation of retention time (Kovats) indices (RIs) and to monitor system performance. Identification of the compounds was based on a comparison of their mass spectra and retention indices (RIs) with the authentic standards and published data, as well as standard mass spectra in the NIST05. Relative quantification of the target compounds for emission was by measuring peak areas, and for accumulation using the internal standard method.

RNA Extraction and Real-Time PCR

Total RNA was isolated from 0.20 g frozen flowers using TRIzol reagent (CoWin Biotech Co., Ltd., Beijing, China), following the manufacturer’s instructions, and then treated with RQ1 DNase I (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) to remove genomic DNA. To synthesize first-strand cDNA, 3.50 μg total RNA was used with the RevertAidTM First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Fermentas, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The synthetic first-strand cDNAs were diluted 10-fold for gene expression analysis.

Gene expression was detected by qRT-PCR in both ‘Gecheng’ and ‘Liuye’ flowers at four flowering stages. The qRT-PCR was performed on an Applied Biosystems 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR platform with the SYBR® Premix Ex TaqTM II mix (Takara Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Dalian, China), according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and the results were analyzed using the Applied Biosystems 7500 software (Applied Biosystems Life Technologies). Three biological replicates were tested, and reactions carried out in triplicate. Relative transcript levels were calculated by the 2-ΔΔCt method using β-actin as the endogenous control gene for data normalization. The primers for qRT-PCR analysis are listed in Supplemental Table S2.

Isolation of OfTPS Genes

Based on the TPS unigene sequences from the transcriptome sequencing of O. fragrans flowers, the full-lengths of four TPS genes were obtained using the SMARTERTM RACE method. The 5′ and 3′-RACE-Ready cDNAs were separately synthesized using the BD SMARTERTM RACE cDNA Amplification Kit (Clontech, Mountain View, CA, USA). The amplified OfTPSs sequences were cloned into pEASY-T1 (TransGene Biotech CO., LTD, Beijing, China) and at least three independent clones were sequenced to check for PCR errors. The OfTPSs open reading frame (ORF) was predicted using the NCBI ORF Finder1. All primers used are listed in Supplemental Table S2.

Multiple Sequence Alignment and Phylogenetic Analysis

The DNAMAN 6.0 software (Lynnon Biosoft, USA) was used for multiple sequence alignment, and the phylogenetic tree constructed using the default parameters of the MEGA 6.1 software. The MEGA employed Clustal W2 software to generate multiple alignments and construction of the phylogenetic tree was based on the neighbor-joining computational method with 1000 bootstrap replicates. The bioinformatics tools ChloroP2 and TargetP3 were used to predict the intracellular localization of OfTPS proteins.

Transient and Stable Expression of OfTPS Genes in Tobacco

Full-length OfTPS ORFs were obtained from the pESAY-T1 vectors containing the target genes, using FastDigest enzymes (Fermentas, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., USA). OfTPS1, OfTPS2, and OfTPS3 were digested with KpnI-XbaI, and OfTPS4 with SmaI-XbaI. The restriction enzyme-generated inserts were cloned into the same restriction sites of the pCAMBIA 2300 binary vector to create pCAMBIA 2300::OfTPSs using T4 DNA ligase (Fermentas, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., USA). pCAMBIA 2300 contained the CaMV 35S promoter and nos-terminator. The pCAMBIA 2300::p19 was created by digesting the pGH-p19 vector using SmaI-XbaI to clone into the pCAMBIA 2300 vector, as described above. These plasmids were transformed in Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain EHA105 by electroporation.

Four to 6-week-old greenhouse-grown Nicotiana benthamiana seedlings were infiltrated with the A. tumefaciens strain EHA105, harboring the pCAMBIA 2300::OfTPSs and pCAMBIA 2300::p19, as described previously (Hellens et al., 2005). When freshly grown Agrobacterium cultures reached an OD600 nm of 0.6–0.8, they were centrifuged and resuspended in infiltration media (10 mM MES, 10 mM MgCl2, 200 μM acetosyringone). The suspensions were adjusted to an OD600 nm of between 1.0 and 2.0, and incubated without shaking at 28°C for 2 h. The target gene and viral suppressor p19 Agrobacterium cultures were mixed in a 1:1 ratio before injection into N. benthamiana leaves using a syringe. After 5 days, 2 g of the treated leaves were harvested and placed in a 20 ml SPME vial for volatile analysis (as above).

Leaf disks of N. tabacum were transformed by co-culture with A. tumefaciens strain EHA105 harboring the pCAMBIA 2300::OfTPSs binary vector. Three to five independent transformed lines were obtained. The transformed plants, obtained after selection with kanamycin, were confirmed by semi quantitative RT-PCR with 2x Es Taq MasterMix (CoWin Biotech Co., Ltd, Beijing, China) and GAPDH as the reference gene. 2 g leaves of the transformed plants were used for volatile analysis.

Results

Analysis of Monoterpene Emission and Accumulation in O. fragrans Flowers

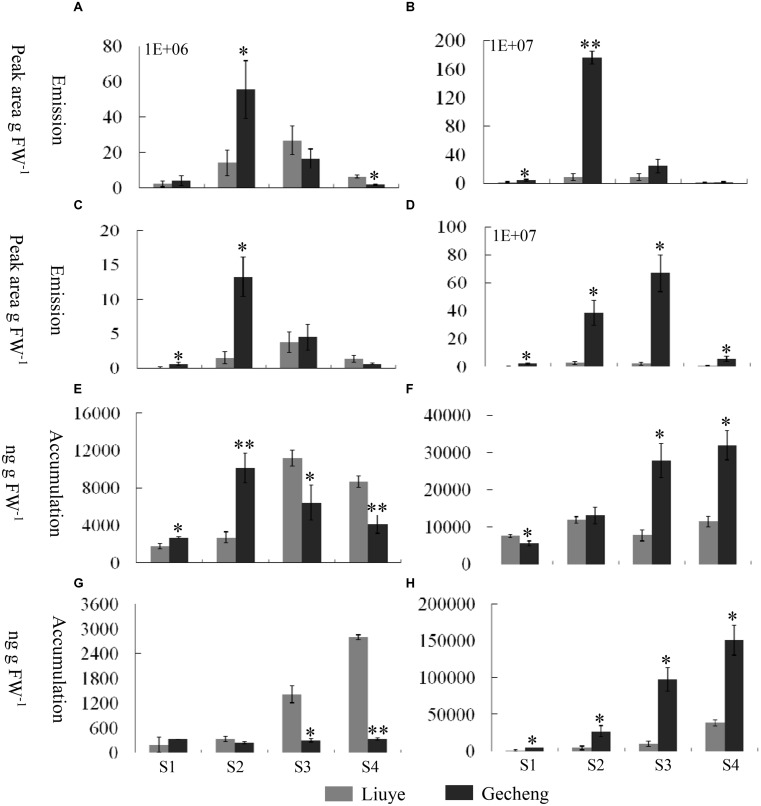

Solid-phase microextraction-GC-MS analysis identified a total of 33 volatile compounds in two cultivars of ‘Gecheng’ and ‘Liuye’ at the initial flowering stage (S2), assigned to monoterpene, norisoprenoid, aromatic and fatty acid-related compounds (Supplemental Table S1). Seventeen monoterpenes were found in the two cultivars, with β-ocimene, linalool and derivatives the dominant components in both cultivars. However, the content of monoterpenes differed in the two cultivars (Figure 1). The relative content of total monoterpenes was higher in ‘Gecheng’ (70%) than ‘Liuye’ (5%). In particular, trans-β-ocimene and linalool accounted for 44 and 23% of the total volatiles in ‘Gecheng’, but for only 1 and 2% in ‘Liuye’ (Supplemental Table S1). The emission of cis-β-ocimene, trans-β-ocimene, linalool and linalool derivatives in both ‘Gecheng’ and ‘Liuye’ flowers showed a similar pattern, increasing from S1 to S3 and decreasing at S4 (Figures 2A–D and 3A). The peak of β-ocimene and linalool emission occurred at S2 in ‘Gecheng’ and at S3 in ‘Liuye,’ while the peak of the linalool derivatives in both cultivars was at S3. The β-ocimene and linalool emissions at S2 were much higher in ‘Gecheng’ than ‘Liuye.’ The emissions of all linalool derivatives were higher in ‘Gecheng’ throughout the flowering stages.

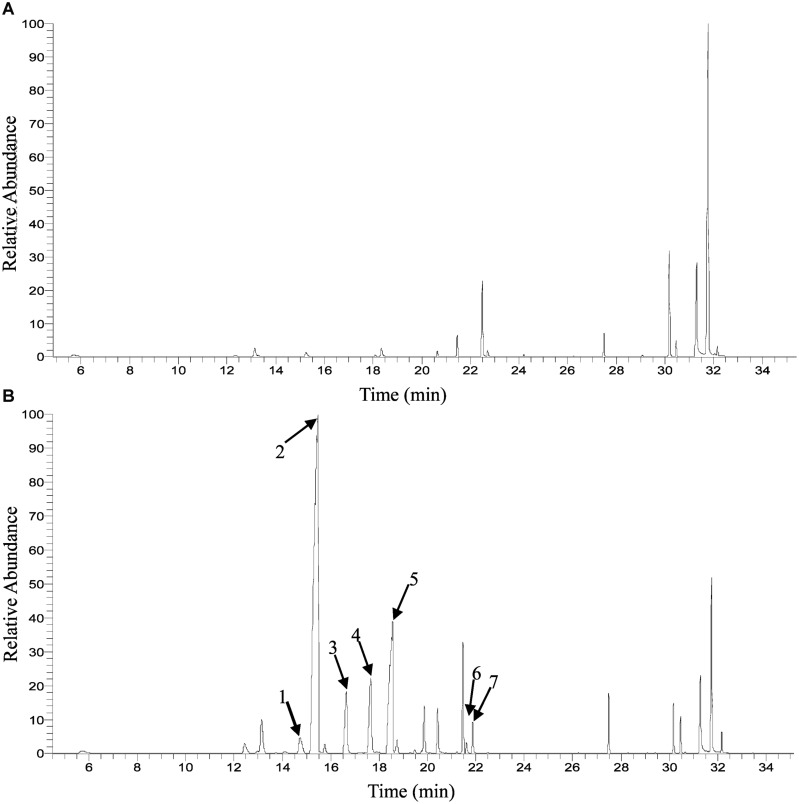

FIGURE 1.

Gas chromatograph (GC) trace of floral volatile emission in Osmanthus fragrans at the initial flowering stage (S2). (A) Liuye, (B) Gecheng. (1) cis-β-ocimene; (2) trans-β-ocimene; (3) cis-Linalool oxide (furanoid); (4) trans-linalool oxide (furanoid); (5) β-linalool; (6) cis-linalool oxide (pyranoid); (7) trans-linalool oxide (pyranoid).

FIGURE 2.

Emission and accumulation of monoterpenes and their derivatives in O. fragrans flowers at four stages. (A–D) Emission abundance of monoterpenes and their derivative volatiles: (A) cis-β-ocimene; (B) trans-β-ocimene; (C) linalool, and (D) total linalool derivatives. (E,F) Free accumulation of linalool and its derivatives: (E) linalool and (F) total linalool derivatives. (G,H) Glycoside accumulation of linalool and its derivatives: (G) linalool and (H) total linalool derivatives. The four flowering stages are: (S1) tight bud stage; (S2) initial flowering stage; (S3) full flowering stage, and (S4) late full flowering stage. Data are presented as mean ± SE (n = 3). The asterisks indicate significant differences between the values of ‘Liuye’ and ‘Gecheng’ at a given flower stage calculated by the Student’s t-test (∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01).

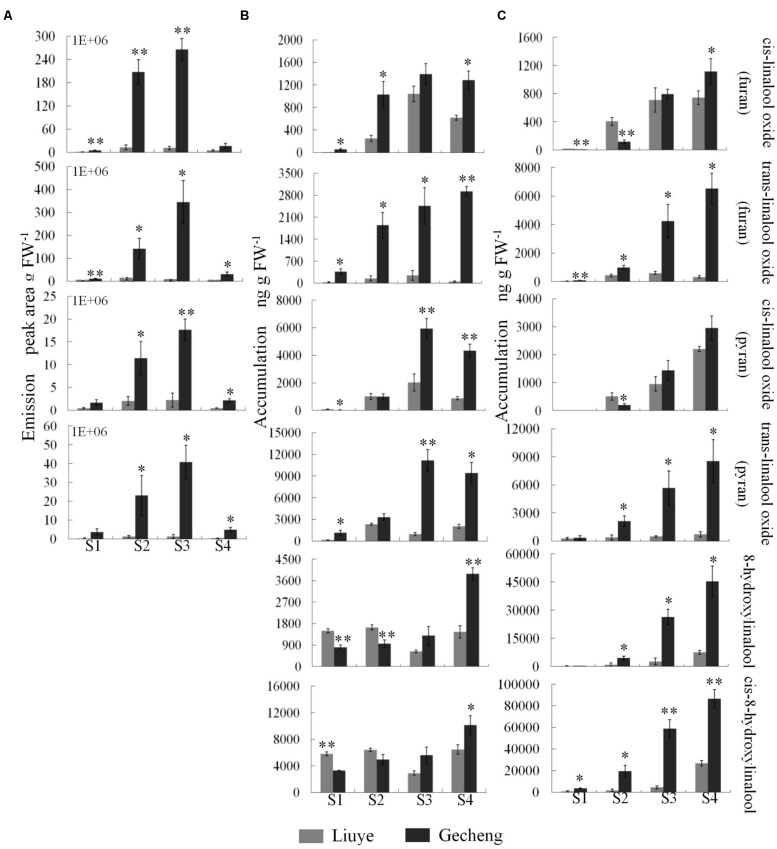

FIGURE 3.

Emission and accumulation of linalool derivatives in O. fragrans flowers at four stages. (A) Emission of linalool derivatives. (B) Accumulation of free linalool derivatives. (C) Accumulation of glycosylated linalool derivatives. Flower stages are: (S1) tight bud stage; (S2) initial flowering stage; (S3) full flowering stage, and (S4) late full flowering stage. Data are presented as mean ± SE (n = 3). The asterisks indicate significant differences between the values of ‘Liuye’ and ‘Gecheng’ at a given flower stage calculated by the Student’s t-test (∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01).

The accumulation of free monoterpenes in flowers was analyzed by solvent extraction, combining with GC-MS, collecting samples at the same stage as for SPME (Figures 2E,F and 3B). Compared with the emitted monoterpenes, β-ocimene was barely detectable, but an abundance of linalool and derivatives accumulated in O. fragrans flowers. Cis-8-hydroxylinalool and 8-hydroxylinalool, the linalolol derivatives, were not detected as emitted floral volatiles but were found in solvent extracts. The accumulation pattern of linalool was consistent with the emission pattern in both cultivars, increasing from S1 to S3 and decreasing slightly at S4. The accumulation of linalool oxides continuously increased up to S3 and slightly decreased at S4, except for trans-linalool oxide(fur) in ‘Gecheng,’ which was still increasing at S4. The accumulation of cis-8-hydroxylinalool and 8-hydroxylinalool in ‘Gecheng’ gradually increased during the flowering stages, reaching the maximum at S4, while they basically remained steady in ‘Liuye,’ dropping slightly at S3. More linalool was accumulated in ‘Gecheng’ at S1 and S2, but in ‘Liuye’ at S3 and S4. The result was just the contrary to cis-8-hydroxylinalool and 8-hydroxylinalool. There was much more accumulation of linalool oxides in ‘Gecheng’ compared to ‘Liuye’ during flowering.

Floral glycosylated volatiles were extracted from O. fragrans flowers and analyzed by GC-MS after enzymatic hydrolysis (Figures 2G,H and 3C; Table 1). Due to lack of hydoxylation in β-ocimene, only linalool and its derivatives were detected in glycosylated forms in O. fragrans flowers. In both cultivars, the glycosylated linalool and derivatives continuously increased during flowering, except for linalool in ‘Gecheng,’ which remained stable throughout the flowering stages. After S2, more glycosylated linalool accumulated in ‘Liuye’ than in ‘Gecheng.’ The glycosylated linalool derivatives as trans-linalool oxide (furan and pyran), cis-8-hydroxylinalool and 8-hydroxylinalool accumulated much more in ‘Gecheng’ than ‘Liuye’ throughout the flowering process. The percentage of glycosylation of linalool continued increasing in ‘Liuye’ from S1 to S4, but maintained a lower fraction in ‘Gecheng.’ Although the percentage of glycoside linalool oxides changed irregularly, total linalool derivatives in glycoside forms continued increasing in both cultivars from S1 to S4, due to the dominant components, cis-8-hydroxylinalool and 8-hydroxylinalool, were constantly increasing.

Table 1.

Glycosylation of linalool and its derivatives in ‘Liuye’ and ‘Gecheng’ cultivars of Osmanthus fragrans flowers at four stages.

| Glycoside (% of total accumulation) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liuye |

Gecheng |

|||||||

| Compounds | S1 | S2 | S3 | S4 | S1 | S2 | S3 | S4 |

| β-linalool | 10.03 ± 2.19 | 10.97 ± 0.15 | 11.22 ± 1.43 | 24.44 ± 1.22 | 10.96 ± 0.39 | 2.36 ± 0.24 | 4.49 ± 1.05 | 7.60 ± 1.54 |

| Total linalool derivatives | 14.89 ± 3.16 | 27.19 ± 3.42 | 55.71 ± 11.74 | 76.88 ± 4.93 | 43.69 ± 8.50 | 67.58 ± 12.70 | 77.76 ± 7.56 | 82.52 ± 6.10 |

| Cis-linalool oxide (furan) | 66.44 ± 5.36 | 61.97 ± 4.38 | 40.56 ± 8.36 | 54.65 ± 5.56 | 12.79 ± 2.70 | 10.29 ± 0.37 | 36.33 ± 1.07 | 46.56 ± 5.80 |

| Trans-linalool oxide (furan) | 51.10 ± 12.30 | 73.80 ± 1.38 | 70.51 ± 9.60 | 86.62 ± 10.76 | 18.39 ± 2.41 | 34.81 ± 0.37 | 63.21 ± 12.35 | 69.03 ± 8.18 |

| Cis-linalool oxide (pyran) | 15.19 ± 2.63 | 33.06 ± 6.81 | 32.04 ± 5.03 | 71.45 ± 1.72 | 26.43 ± 7.34 | 16.82 ± 2.84 | 19.50 ± 4.16 | 40.49 ± 4.73 |

| Trans-linalool oxide (pyran) | 67.29 ± 15.68 | 13.70 ± 2.16 | 33.40 ± 2.70 | 25.89 ± 6.30 | 24.10 ± 7.80 | 38.85 ± 8.91 | 33.63 ± 9.82 | 47.56 ± 10.48 |

| 8-hydroxylinalool | 13.14 ± 3.40 | 37.58 ± 11.50 | 81.03 ± 12.90 | 83.73 ± 5.82 | 29.65 ± 6.13 | 82.49 ± 10.55 | 95.33 ± 4.34 | 92.08 ± 6.48 |

| Cis-8-hydroxylinalool | 11.60 ± 1.58 | 21.06 ± 5.45 | 60.09 ± 14.33 | 80.53 ± 4.32 | 52.29 ± 12.31 | 79.63 ± 13.24 | 91.32 ± 5.09 | 89.54 ± 3.64 |

Data are presented as mean ± SE (n = 3). The values in bold indicate significant differences to the ‘Liuye’ values at a given flower stage ( Student’s t-test P < 0.05).

Expression Analysis of Genes Involved in Monoterpene Biosynthesis in O. fragrans Flowers

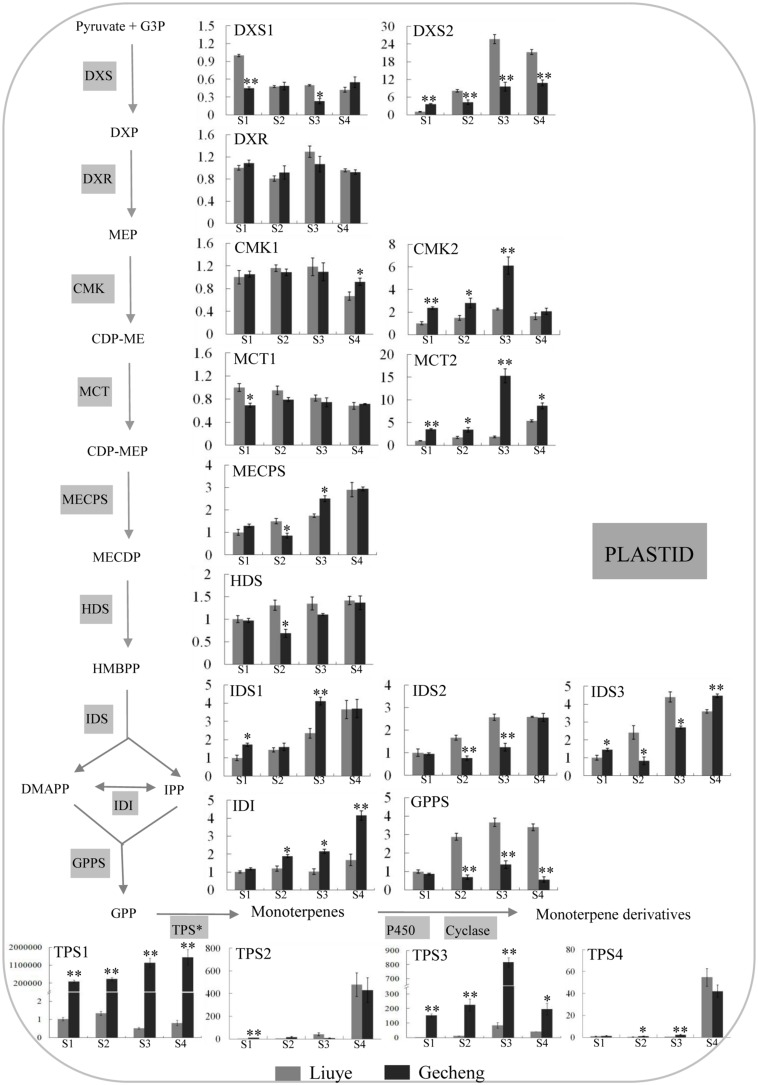

The MEP pathway produces IPP and DMAPP for production of monoterpenes (Munoz-Bertomeu et al., 2006) and TPS is the final enzyme converting the precursor GPP to kinds of monoterpenes (Degenhardt et al., 2009). The transcript levels of thirteen genes involved in the eight enzyme reaction stages of the MEP pathway, one GPPS, and four TPSs were analyzed by real-time qPCR (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

Expression of genes involved in monoterpene biosynthesis in O. fragrans flowers at four stages. Flower stages are: (S1) tight bud stage; (S2) initial flowering stage; (S3) full flowering stage, and (S4) late full flowering stage. The relative abundance was determined using a 2-ΔΔCt method with β-actin as the reference gene. Results represent the mean ± SE of three technical repetitions and three biological replicates. The asterisks indicate significant differences between the values of ‘Liuye’ and ‘Gecheng’ at a given flower stage calculated by the Student’s t-test (∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01). Abbreviations: G3P, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate; DXP, 1-deoxy-D-xylulose 5-phosphate; MEP, methylerythritol phosphate; CDP-ME, 4-diphosphocytidyl-2-C-methyl-D-erythritol; CDP-MEP, CDP-ME 2-phosphate; MECPD, 2-C-methyl-D-erythritol 2,4-cyclodiphosphate; HMBPP, (E)-4-hydroxy-3-methylbut-2-en-1-yl diphosphate; IPP, isopentenyl pyrophosphate; DMAPP, dimethylallyl pyrophosphate; GPP, geranyl pyrophosphate; MVP, mevalonate 5-phosphate; FPP, farnesyl pyrophosphate; DXS, 1-deoxy-D-xylulose 5-phosphate synthase; DXR, 1-deoxy-D-xylulose 5-phosphate reductoisomerase; MCT, 2-C-methyl-D-erythritol 4-phosphate cytidylyltransferase; CMK, 4-(cytidine 5′-diphospho)-2-C-methyl-D-erythritol kinase; MECPS, 2-C-methyl-D-erythritol 2,4-cyclodiphosphate synthase; HDS, 4-hydroxy-3-methylbut-2-en-1-yl diphosphate synthase; IDS, isopentenyl diphosphate synthase; IDI, isopentenyl pyrophosphate isomerase; GPPS, geranyl pyrophosphate synthase; TPS, terpene synthase.

In the MEP pathway, the expression levels of DXR, CMK1, and MCT1 remained stable in the two cultivars throughout the flowering stages, and only subtle differences (<2 fold) were detected in DXS1, MECPS, HDS, IDS1, IDS2, and IDS3 expression between the two cultivars. There was higher expression of CMK2, MCT2, and IDI in ‘Gecheng’ than ‘Liuye’ from S1 to S4, but the difference was no more than threefold between the two cultivars, except for MCT2 at S3. DXS2 expression was no more than threefold higher in ‘Liuye’ than ‘Gecheng’ from S2 to S4. These results showed that, during flowering, there were minor differences between the two cultivars in the expression of most genes in the MEP pathway. Expression of GPPS was the same in both cultivars at S1, but three–fivefold higher in ‘Liuye’ from S2 to S4. Regarding the TPS genes, there was no apparent difference between the two cultivars during flowering for TPS2 and TPS4 expression, which gradually increased from S1 to S3 followed by a dramatic increase at S4. However, it is worth noting that the expression of TPS1 and TPS3 was more than 100-fold higher in ‘Gecheng’ compared to ‘Liuye’ throughout flowering stage. TPS1 expression consistently increased from S1 to S4, while TPS3 had the highest level of transcript accumulation at S3 in the two cultivars. The differences in the levels of TPS gene expression between ‘Gecheng’ and ‘Liuye’ indicated their important contribution to monoterpene formation in O. fragrans flowers.

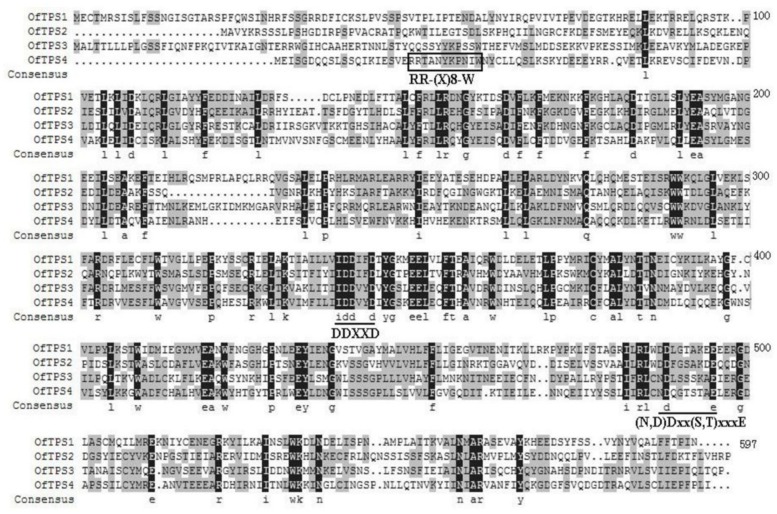

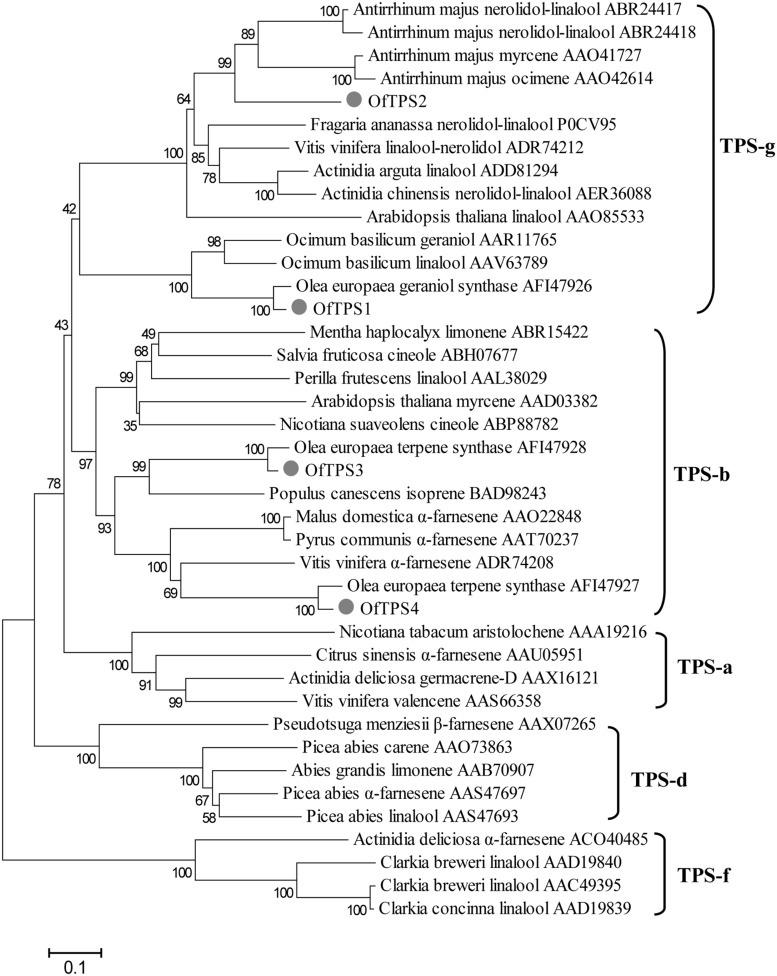

Sequence Characterization of TPS Genes from O. fragrans Flowers

The four full-length TPS genes were cloned using the RACE-PCR method. Their ORF sequences were 1746, 1668, 1776, and 1647 bp, respectively, designated OfTPS1, OfTPS2, OfTPS3, and OfTPS4 (GeneBank no. KT591180 to KT591183). The sequences of these four genes were identical in the cultivars ‘Gecheng’ and ‘Liuye.’ The four encoded proteins had highly conserved elements of TPSs, the DDxxD motif and the (N,D)D(L,I,V)x(S,T)xxxE motif, implying that they had the same capacity to bind the diphosphate group substrate (Figure 5). The N-terminal RR(x)8W motif, involved in producing cyclic monoterpenes and absent in TPSs that produce acyclic products, only appeared in OfTPS4 (Figure 5). Using the ‘ChloroP’ and ‘TargetP’ programs4, OfTPS1 and OfTPS3 were found to contain an extended N-terminus, recognized as a signal peptide, with a length of 47 and 38 amino acids, respectively. Phylogenetic analysis of the predicted amino acid sequences compared with TPS protein sequences in other species indicated that OfTPS1and OfTPS2 belong to the TPS-g subfamily, which lacks the RR(x)8W motif and mainly produce acyclic terpenes (Figure 6). OfTPS1 and OfTPS2 divided into two distinct clades. OfTPS1 grouped together with geraniol synthase and linalool synthase from Olea europaea and Ocimum basilicam in one clade, and OfTPS2 in the clade with linalool synthase, nerolidol/linalool synthase, myrcene synthase and ocimene synthase of A. majus. OfTPS3 and OfTPS4 fell into the TPS-b subfamily, covering angiosperm monoterpene synthases (Figure 6). OfTPS1, OfTPS3, and OfTPS4 showed highest amino acid sequence identity with geraniol synthase (90%), OeTPS3 (90%), and OeTPS2 (89%) from O. europaea, respectively. These results illustrate that they were the remaining uncharacterized TPSs and close to the similarly functional TPSs of O. europaea, also belonging to the Oleaceae family.

FIGURE 5.

Alignment of the amino acid sequences of OfTPS1, OfTPS2, OfTPS3, and OfTPS4. Amino acids identical in all four proteins are shaded black and those identical in three proteins are shaded gray. The three highly conserved motifs are labeled RR-(x)8-W, DDxxD and (N,D)Dxx(S,T)xxxE, respectively.

FIGURE 6.

Phylogenetic analysis of selected plant terpene synthases (TPSs) based on estimation of pair-wise distances at the amino acid level. Clusters corresponding to five TPS subfamilies (TPS-a,TPS-b, TPS-d, TPS-g, and TPS-f) are apparent. The Clustal W 2.0 algorithm was used for the alignment. Trees were inferred with the neighbor-joining (NJ) method and n = 1000 replicates for bootstrapping.

Functional Identification of OfTPS Genes in Planta

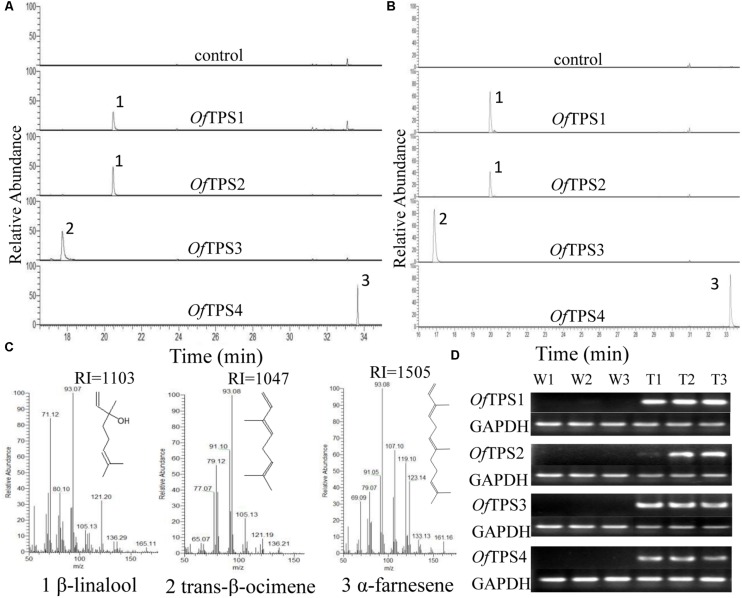

To investigate the volatiles produced by OfTPSs in planta, transient plant expression (Hellens et al., 2005) was carried out by infiltration of N. benthamiana leaves using A. tumefaciens carrying pCAMBIA 2300::OfTPSs. Samples were taken 5–6 days after inoculation and emitted volatiles were analyzed by SPME headspace sampling. Over-expression of OfTPS1 and OfTPS2 produced large amounts of β-linalool, with no other products detected. Only trans-β-ocimene was detected in tobacco leaves over-expressing OfTPS3, and α-farnesene was the only product in those over-expressing OfTPS4. No related products were observed in control leaves infiltrated with empty binary vectors (Figures 7A,C).

FIGURE 7.

Functional characterization of terpene synthases (TPSs) from O. fragrans in planta.(A) GC trace of leaves of transiently expressed N. benthamiana plants. (B) GC trace of leaves of transgenic N. tabacum plants. (C) Mass spectra of the products: (1) β-linalool, (2) trans-β-ocimene, (3) α-farnesene. Products were confirmed by comparison with authentic standards and/or GC-MS retention indices. (D) Semi-quantitative RT-PCR assay of OfTPS genes in transgenic N. tabacum plants.

Moreover, stably transformed N. tabacum plants were obtained through transformation with A. tumefaciens strain EHA105 harboring the pCAMBIA 2300::OfTPSs. Positive transgenic plants were further identified by semi-quantitative RT-PCR (Figure 7D). The volatile products of the OfTPS transformed plants were detected by SPME-GC-MS, and the results were the same as those from transient expression in plants (Figure 7B). These results suggest that both OfTPS1 and OfTPS2 are involved in synthesis of the same terpene product, β-linalool, and OfTPS3 and OfTPS4 are related to trans-β-ocimene and α-farnesene synthesis in planta, respectively.

Discussion

Monoterpenes are common components of floral scent and play a role in attracting pollinators in plants (Dudareva and Pichersky, 2006). Previous studies focusing on floral volatiles composition from O. fragrans have identified about 20 monoterpenes and find that monoterpenes such as β-ocimene, linalool and linalool derivatives are the major components of floral volatiles in most cultivars (Cao et al., 2009; Sun et al., 2012; Xin et al., 2013). In an earlier study, we also identified these compounds as important aroma-active compounds in O. fragrans flowers, with the two cultivars of ‘Gecheng’ and ‘Liuye’ having distinct monoterpene emission profiles (Cai et al., 2014). The current study gives basically identical results: monoterpenes, especially trans-β-ocimene and linalool, make up a large amount of the floral volatiles in ‘Gecheng’ but only a trace in ‘Liuye’ (Figure 1 and Supplemental Table S1). The results confirmed that ‘Liuye’ only produces small amounts of monoterpenes, unlike most O. fragrans cultivars, so this cultivar can be used as contrasting materials for our further study on the molecular mechanism of monoterpene biosynthesis.

Monoterpenes Emission and Glycosylation in O. fragrans Flowers

The emission of floral volatiles in A. majus and the content of essential oil in Lavandula species can vary with flower development (Dudareva et al., 2000, 2003; Lane et al., 2010). We analyzed the emission and accumulation patterns of the dominant monoterpenes in two O. fragrans cultivars throughout the flowering stages. The highest levels of β-ocimene and linalool were found at the initial flowering stage in ‘Gecheng’ and at the full flowering stage in ‘Liuye,’ with emission of linalool derivatives reaching a peak at the initial or full flowering stage. These emission patterns were consistent with the other cultivars (Li et al., 2008) and the concentrated emission of monoterpenes coincided with the optimal time for organoleptic aroma and pollination in O. fragrans (Baldermann et al., 2010; Zhang, 2013). Moreover, the accumulation pattern of free linalool in the two cultivars was consistent with its emission, reaching the highest level in ‘Gecheng’ at the initial flowering stage and in ‘Liuye’ at the full flowering stage. Meanwhile, a parallel trend was observed between accumulation of free linalool oxides and their emission from the tight bud stage to the full flowering stage. These results suggested that both emission and accumulation of monoterpene are controlled by flower development, and the accumulation of free monoterpenes in flowers is directly proportional to their emission in O. fragrans flowers.

It has been reported that glycosylation might be involved in regulating the release of floral volatiles. For example, the decrease of glycosylated 2-phenylethanol in flowers correlating with rhythmic emission has demonstrated that glycosylation has an impact on floral 2-phenylethanol rhythmical release in Rosa damascena (Picone et al., 2004). But the glycosylation profile cannot account for the different rhythmic patterns of (E)-nerolidol accumulation and emission in Actinidia chinensis (Green et al., 2012). In this study, the accumulation and emission of linalool and its oxides in O. fragrans flowers shared parallel patterns from the tight bud stage to the full flowering stage. However, significant amounts of glycosylated linalool and its oxides were found during this period, and their accumulation continuously increased, especially at late full flowering stage when only a small amount of linalool and its oxides were released. These results showed that glycosylation was likely to have an impact on the linalool release in O. fragrans flowers at different flowering stages. Beside direct glycosylation, linalool tends to enzymatically convert to more stable linalool derivatives such as 8-hydroxylinalool and then is stored in plant tissues in glycosylated forms (Lewinsohn et al., 2001; Chen et al., 2010; Green et al., 2012). In O. fragrans flowers, a large amount of linalool derivatives, especially cis-8-hydroxylinalool and 8-hydroxylinalool, were found and depleted the pool of linalool. These results showed the complexity of linalool metabolism, and further research on the accumulation and emission of linalool and its derivative should consider the action of glucosidase, cytochrome, P450 or cyclase for further catalytic conversion.

MEP Pathway Genes Analysis of O. fragrans Flowers

Monoterpene biosynthesis depends on the MEP pathway and the GPPS enzyme providing the GPP substrate (Chen et al., 2011). To discover the key gene controlling monoterpenes formation, the expression of genes involving in these enzymatic reactions were monitored in ‘Gecheng’ and ‘Liuye’ during flowering stages. It has been reported that, except for DXS and IDI, the other enzymes of the MEP pathway are encoded by single copy genes in Arabidopsis (Cordoba et al., 2009). Two distinctive forms of CMK and IDS have been found in gymnosperms such as Ginkgo biloba and Pinus taeda (Kim et al., 2008a,b). Two different gene expression patterns of CMK, MCT, and IDS in two cultivars throughout the flowering stages indicated that at least two forms exist in O. fragrans. This suggested that regulation of metabolic flux by a multigene is also present at the mid-point of the MEP pathway in addition to the first step of this pathway in O. fragrans.

As the over-expression of DXS in transgenic A. thaliana and tomato result in an increase in plastid isoprenoids such as diterpenes and carotenoids, the DXS enzyme has been considered as a rate-limiting enzyme for MEP pathway flux (Enfissi et al., 2005; Carretero-Paulet et al., 2006). In glandular trichomes of Ocimum basilicum, the transcript abundance of DXS correlates with oil yield which consists mostly of monoterpenes (Xie et al., 2008). In V. vinifera, DXS co-localizes with a major QTL for the accumulation of linalool, nerol and geraniol (Battilana et al., 2009). During the berry development, DXS expression shows a significant correlation with the accumulation profile of these monoterpenes (Battilana et al., 2011). However, in this study, DXS gene expression did not agree with the emission and accumulation profiles of monoterpenes from O. fragrans flowers. On the contrary, there was a higher expression of DXS2 in ‘Liuye’ producing less monoterpenes from flowers. In the second step of the MEP pathway, DXR has also been suggested as a rate-limiting enzyme in A. thaliana, Mentha piperita, O. basilicum (Wildung and Croteau, 2005; Carretero-Paulet et al., 2006; Xie et al., 2008). However, the expression of DXR was also inconsistent with the monoterpenes production in O. fragrans. HDS and IDS is associated with foliar concentrations of the monoterpene 1,8-cineole in Eucalyptus globulus (Külheim et al., 2011). Here, there was no connection between gene expression of HDS and IDS and the production of monoterpenes. Therefore, we concluded that these MEP pathway genes controlling the pathway flux in other species was not the rate-limiting factor for monoterpene biosynthesis in O. fragrans. Unexpectedly, the level of expression of CMK2 and MCT2 was higher in ‘Gecheng’ than in ‘Liuye.’ There were no reports about the connection between CMK, MCT, and monoterpene production, however, their gene expression seemed to be consistent with monoterpene emission in O. fragrans, the roles of CMK and MCT need further analysis.

OfTPS Genes Expression in O. fragrans Flowers

Transcriptional control of TPS genes has been shown to regulate the production of certain monoterpenes. For example, both spatial and temporal AlstroTPS expression correlates well with myrcene emission in scented Alstroemeria genotypes (Aros et al., 2012). Also, a concerted increase between expression of LaLINS and accumulation of linalool has been reported in the essential oil of Lavandula angustifolia during flower development (Lane et al., 2010). Similar results have been found in plants such as A. majus (Dudareva et al., 2003) and Origanum vulgare (Crocoll et al., 2010). In this study, TPS2 and TPS4 expression showed a drastic increase from full flowering stage to late full flowering stage but no difference between ‘Gecheng’ and ‘Liuye’ during flowering stages, which was not consistent with the emission and accumulation of monoterpene in the two cultivars. Interestingly, expression of TPS1 and TPS3 was more than 100 fold higher in ‘Gecheng’ as compared to ‘Liuye,’ and their expression was in agreement with the production of monoterpene during flowering. These results indicated a direct contribution of TPS1 and TPS3 to monoterpenes production in flowers of O. fragrans. Carotenoid and monoterpene biosynthesis share the same pathway, which indicates a possible competition for the IPP and DMAPP precursors (Botella-Pavía et al., 2004; Dudareva et al., 2013). However, although the production of monoterpenes in ‘Liuye,’ containing trace amounts of carotenoids, was low and ‘Gecheng,’ with large mounts of carotenoids still produced a lot of monoterpenes, this was only related to TPS genes expression. The results further demonstrated that the transcript levels of TPS genes on monoterpene production had a greater effect compared with the competition of carotenoid synthesis. This led to the conclusion that transcriptional regulation of TPS genes, especially TPS1 and TPS3, was likely to be the most important mechanism for controlling production of the monoterpenes linalool or β-ocimene in O. fragrans flowers.

Sequence and Functional Characterization of O. fragrans TPS Genes

The putative functions of the four isolated TPSs from O. fragrans were initially predicted according to the conserved motifs and amino acid sequence similarity with known TPSs from other species. The four OfTPSs shared the conserved motifs DDxxD and (N,D)Dxx(S,T)xxxE) with other TPSs. OfTPS1 and OfTPS3 had the typical putative plastid targeting signal peptides but lacked the RR(x)8W motif in the N-terminal, which indicated they probably encoded acyclic monoterpene synthases. Phylogenetic analysis placed OfTPS1 in the TPS-g subfamily defined by monoterpene synthases, that produce acyclic scent compounds such as myrcene and ocimene in A. majus (Dudareva et al., 2003), and linalool in A. thaliana (Chen et al., 2003) and V. vinifera (Martin et al., 2010). Although OfTPS2 also belonged to the TPS-g subfamily, it was not clear whether this gene encodes a mono-TPS or sesqui-TPS, due to its unpredictable signal peptide and clustering with the bifunctional linalool/nerolidol synthase of A. majus (Nagegowda et al., 2008), V. vinifera (Martin et al., 2010), and A. chinensis (Green et al., 2012). OfTPS3 and OfTPS4 clustered into the TPS-b subfamily in which all characterized TPSs are either monoterpene synthases, including all A. thaliana monoterpene synthases except linalool synthase (Chen et al., 2003) and V. vinifera ocimene synthases (Martin et al., 2010), or isoprene synthases (Chen et al., 2011). But OfTPS4 clustered with α-farnesene synthase from Malus domestica (Nieuwenhuizen et al., 2013) and V. vinifera (Martin et al., 2010). Of the four OfTPS proteins, only OfTPS4 had the RR(x)8W motif that is present in all cyclic monoterpene synthases and most sesquiterpene and diterpene synthases (Hyatt et al., 2007), which may play a role in triggering isomerization-cyclization or act to stabilize the protein (Whittington et al., 2002a,b). Moreover, the unapparent signal peptide and high homology with α-farnesene synthase in phylogenetic analysis suggested that OfTPS4 was most likely a sesquiterpene synthase.

Transient and stable expression in tobacco leaves further confirm the function of OfTPS genes in planta, which could partly explain the production of major monoterpene volatiles in O. fragrans flowers. Over-expression of OfTPS1 and OfTPS3 genes in tobacco leaves resulted in the formation of only β-linalool and trans-β-ocimene, respectively. OfTPS2, that may be a bifunctional linalool/nerolidol synthase, produced β-linalool exclusively in over-expressing tobacco leaves. As previously speculated, sesquiterpene α-farnesene was the sole product emitted from tobacco leaves over-expressing OfTPS4. Most of the TPS enzymes from V. vinifera are multiple-product enzymes that can act on one substrate to produce more than one product (Martin et al., 2010). However, there was only a single product of the four OfTPSs in the over-expressing tobacco leaves. The TPS enzyme, that produces the same single product, has also been found in V. vinifera and M. domestica (Pechous and Whitaker, 2004; Martin et al., 2010; Nieuwenhuizen et al., 2013). OfTPS1, OfTPS3, and OfTPS4 showed high homology with OeGES, OeTPS3, and OeTPS2 from O. europaea, respectively (Figure 6). The homologous TPS proteins from O. fragrans and O. europaea had entirely different enzyme activities. Heterologous expression in a bacterial system has demonstrated that OeGES is a geraniol synthase only producing geraniol, and OeTPS2 and OeTPS3 have no enzymatic activity (Vezzaro et al., 2012). Fischer et al. (2013), expressing O. basilicum geraniol synthase in V. vinifera, A. thaliana, N. benthamiana and a microbial system, has shown that the genetic background of the heterologous expression host could have an influence on minor products but not on the main product. Nevertheless the major monoterpene compounds (β-linalool and trans-β-ocimene) found in O. fragrans flowers have been detected in tobacco leaves over-expressing OfTPS1, OfTPS2, and OfTPS3. Moreover, gene expression of OfTPS1 and OfTPS3 are closely correlated to the accumulation or emission of β-linalool and trans-β-ocimene in O. fragrans flowers. Therefore, we conclude that OfTPS1 and OfTPS3 are separately the key genes associating with β-linalool and trans-β-ocimene production in O. fragrans flowers.

This study provided the molecular basis for the production of major monoterpenes in O. fragrans. The monoterpenes emission and accumulation profiles open the way to further understand the role of monoterpenes in the physiology and pollination biology of O. fragrans flowers. Understanding the expression of the MEP pathway genes in relation to monoterpene metabolism could generate vital information regarding the regulation of monoterpene biosynthesis in higher plants. The findings on the key TPS genes responsible for formation of the major monoterpenes would be a great advantage for breeding and manipulation of scent related-enzymes to enhance the ornamental and economic value in O. fragrans as well as in other plants in the future.

Author Contributions

XZ, CW designed the research; XZ, CL, XC, and JZ performed the research; XZ, RZ, and CL analyzed the data; XZ wrote the article; CW, JL, and RZ critically read the article.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Doctoral Fund of the Ministry of Education of China (Project No 20130146110022), Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Project No 2013PY088) and Hubei Collaborative Innovation Center for the Characteristic Resources Exploitation of Dabie Mountains (Project No 2015TD02).

Footnotes

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpls.2015.01232

References

- Aros D., Gonzalez V., Allemann R. K., Müller C. T., Rosati C., Rogers H. J. (2012). Volatile emissions of scented Alstroemeria genotypes are dominated by terpenes, and a myrcene synthase gene is highly expressed in scented Alstroemeria flowers. J. Exp. Bot. 63 2739–2752. 10.1093/jxb/err456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aurore G., Ginies C., Ganou-parfait B., Renard C. M. G. C., Fahrasmane L. (2011). Comparative study of free and glycoconjugated volatile compounds of three banana cultivars from French West Indies: Cavendish, Frayssinette and Plantain. Food Chem. 129 28–34. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2011.01.104 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baldermann S., Kato M., Kurosawa M., Kurobayashi Y., Fujita A., Fleischmann P., et al. (2010). Functional characterization of a carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase 1 and its relation to the carotenoid accumulation and volatile emission during the floral development of Osmanthus fragrans Lour. J. Exp. Bot. 61 2967–2977. 10.1093/jxb/erq123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battilana J., Costantini L., Emanuelli F., Sevini F., Segala C., Moser S., et al. (2009). The 1-deoxy-dxylulose 5-phosphate synthase gene co-localizes with a major QTL affecting monoterpene content in grapevine. Theor. Appl. Genet. 118 653–669. 10.1007/s00122-008-0927-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battilana J., Emanuelli F., Gambino G., Gribaudo I., Gasperi G., Boss P. K., et al. (2011). Functional effect of grapevine 1-deoxy-D-xylulose 5-phosphate synthase substitution K284N on Muscat flavour formation. J. Exp. Bot. 62 5497–5508. 10.1093/jxb/err231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birtić S., Ginies C., Causse M., Renard C. M. G. C., Page D. (2009). Changes in volatiles and glycosides during fruit maturation of two contrasted tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) lines. J. Agric. Food Chem. 57 591–598. 10.1021/jf8023062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botella-Pavía P., Besumbes O., Phillips M. A., Carretero-Paulet L., Boronat A., Rodríguez-Concepción M. (2004). Regulation of carotenoid biosynthesis in plants:evidence for a key role of hydroxymethylbutenyl diphosphate reductase in controlling the supply of plastidial isoprenoid precursors. Plant J. 40 188–199. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02198.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai X., Mai R. Z., Zou J. J., Zhang H. Y., Zeng X. L., Zheng R. R., et al. (2014). Analysis of aroma-active compounds in three sweet osmanthus (Osmanthus fragrans) cultivars by gas-chromatography-olfactometry and GC-mass spectrometry. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. B 15 638–648. 10.1631/jzus.B1400058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao H., Li Z., Shen D. (2009). GC/MS fingerprint analysis of Osmanthus fragrans Lour. in different varieties. Acta Hort. Sin. 36 391–398. [Google Scholar]

- Carretero-Paulet L., Cairó A., Botella-Pavía P., Besumbes O., Campos N., Boronat A., et al. (2006). Enhanced flux through the methylerythritol 4-phosphate pathway in Arabidopsis plants overexpressing deoxyxylulose 5-phosphate reductoisomerase. Plant Mol. Biol. 62 683–695. 10.1007/s11103-006-9051-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen F., Tholl D., Bohlmann J., Pichersky E. (2011). The family of terpene synthases in plants: a mid-size family of genes for specialized metabolism that is highly diversified throughout the kingdom. Plant J. 66 212–229. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04520.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen F., Tholl D., D’Auria J. C., Farooq A., Pichersky E., Gershenzon J. (2003). Biosynthesis and emission of terpenoid volatiles from Arabidopsis flowers. Plant Cell 15 481–494. 10.1105/tpc.007989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Yauk Y., Nieuwenhuizen N. J., Matich A. J., Wang M. Y., Perez R. L., et al. (2010). Characterisation of an (S)-linalool synthase from kiwifruit (Actinidia arguta) that catalyses the first committed step in the production of floral lilac compounds. Funct. Plant. Biol. 37 232–243. 10.1071/FP09179 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cordoba E., Salmi M., Leon P. (2009). Unravelling the regulatory mechanisms that modulate the MEP pathway in higher plants. J. Exp. Bot. 60 2933–2943. 10.1093/jxb/erp190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crocoll C., Asbach J., Novak J., Gershenzon J., Degenhardt J. (2010). Terpene synthases of oregano (Origanum vulgare L.) and their roles in the pathway and regulation of terpene biosynthesis. Plant Mol. Biol. 73 587–603. 10.1007/s11103-010-9636-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidovich-Rikanati R., Lewinsohn E., Bar E., Iijima Y., Pichersky E., Sitrit Y. (2008). Overexpression of the lemon basil α-zingiberene synthase gene increases both mono- and sesquiterpene contents in tomato fruit. Plant J. 56 228–238. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03599.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degenhardt J., Köllner T. G., Gershenzon J. (2009). Monoterpene and sesquiterpene synthases and the origin of terpene skeletal diversity in plants. Phytochemistry 70 1621–1637. 10.1016/j.phytochem.2009.07.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudareva N., Klempien A., Muhlemann J. K., Kaplan I. (2013). Biosynthesis, function and metabolic engineering of plant volatile organic compounds. New Phytol. 198 16–32. 10.1111/nph.12145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudareva N., Martin D., Kish C. M., Kolosova N., Gorenstein N., Faldt J., et al. (2003). (E)-β-ocimene and myrcene synthase genes of floral scent biosynthesis in snapdragon: function and expression of three terpene synthase genes of a new terpene synthase subfamily. Plant Cell 15 1227–1241. 10.1105/tpc.011015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudareva N., Murfitt L. M., Mann C. J., Gorenstein N., Kolosova N., Kish C. M., et al. (2000). Developmental regulation of methyl benzoate biosynthesis and emission in snapdragon flowers. Plant Cell 12 949–961. 10.2307/3871221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudareva N., Pichersky E. (2006). “Floral scent metabolic pathways: their regulation and evolution,” in Biology of Floral Scent, eds Dudareva N., Pichersky E. (Boca Raton, FL: CRC/Taylor and Francis; ), 55–78. [Google Scholar]

- Enfissi E. M. A., Fraser P. D., Lois L. M., Boronat A., Schuch W., Bramley P. M. (2005). Metabolic engineering of the mevalonate and non-mevalonate isopentenyl diphosphate-forming pathways for the production of health-promoting isoprenoids in tomato. Plant Biotechnol. J. 3 17–28. 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2004.00091.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estévez J. M., Cantero A., Reindl A., Reichler S., León P. (2001). 1-Deoxy-D-xylulose-5-phosphate synthase, a limiting enzyme for plastidic isoprenoid biosynthesis in plants. J. Biol. Chem. 276 22901–22909. 10.1074/jbc.M100854200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer M. J. C., Meyer S., Claudel P., Perrin M., Ginglinger J. F., Gertz C., et al. (2013). Specificity of Ocimum basilicum geraniol synthase modified by its expression in different heterologous systems. J. Biotechnol. 163 24–29. 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2012.10.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia C. V., Stevenson R. J., Atkinson R. G., Winz R. A., Quek S. Y. (2013). Changes in the bound aroma profiles of ‘Hayward’ and ‘Hort16A’ kiwifruit (Actinidia spp.) during ripening and GC-olfactometry analysis. Food Chem. 137 45–54. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garms S., Kollner T. G., Boland W. (2010). A multiproduct terpene synthase from Medicago truncatula generates cadalane sesquiterpenes via two different mechanisms. J. Organ. Chem. 75 5590–5600. 10.1021/jo100917c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green S. A., Chen X., Nieuwenhuizen N. J., Matich A. J., Wang M. Y., Bunn B. J., et al. (2012). Identification, functional characterization, and regulation of the enzyme responsible for floral (E)-nerolidol biosynthesis in kiwifruit (Actinidia chinensis). J. Exp. Bot. 63 1951–1967. 10.1093/jxb/err393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han Y., Wang X., Chen W., Dong M., Yuan W., Liu X., et al. (2014). Differential expression of carotenoid-related genes determines diversified carotenoid coloration in flower petal of Osmanthus fragrans. Tree Genet. Genomes 10 329–338. 10.1007/s00425-010-1222-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hellens R., Allan A., Friel E., Bolitho K., Grafton K., Templeton M., et al. (2005). Transient expression vectors for functional genomics, quantification of promoter activity and RNA silencing in plants. Plant Methods 1:13 10.1186/1746-4811-1-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyatt D. C., Youn B., Zhao Y., Santhamma B., Coates R. M., Croteau R. B., et al. (2007). Structure of limonene synthase, a simple model for terpenoid cyclase catalysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104 5360–5365. 10.1073/pnas.0700915104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S. M., Kim Y. B., Kuzuyama T., Kim S. U. (2008a). Two copies of 4-(cytidine 5-diphospho)-2-C-methyl-D-erythritol kinase (CMK) gene in Ginkgo biloba: molecular cloning and functional characterization. Planta 228 941–950. 10.1007/s00425-008-0794-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S. M., Kuzuyama T., Chang Y. J., Kobayashi A., Sando T., Kim S. U. (2008b). 1-Hydroxy-2-methyl-2-(E)-butenyl 4-diphosphate reductase (IDS) is encoded by multicopy genes in gymnosperms Ginkgo biloba and Pinus taeda. Planta 227 287–298. 10.1007/s00425-007-0616-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Külheim C., Yeoh S. H., Wallis I. R., Laffan S., Moran G. F., Folev W. J. (2011). The molecular basis of quantitative variation in foliar secondary metabolites in Eucalyptus globulus. New Phytol. 191 1041–1053. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2011.03769.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane A., Boecklemann A., Woronuk G., Sarker L., Mahmoud S. (2010). A genomics resource for investigating regulation of essential oil production in Lavandula angustifolia. Planta 231 835–845. 10.1007/s00425-009-1090-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn E., Schalechet F., Wilkinson J., Matsui K., Tadmor Y., Nam K. H., et al. (2001). Enhanced levels of the aroma and flavor compound S-linalool by metabolic engineering of the terpenoid pathway in tomato fruits. Plant Physiol. 127 1256–1265. 10.1104/pp.010293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z., Cao H., Zhu G., Gao J., Shen D. (2008). Study on chemical constituents of fragrance releases from fresh flowers of three different Osmanthus fragrans Lour. During different florescences. Chem. Ind. For. Prod. 28 75–80. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoud S. S., Croteau R. B. (2001). Metabolic engineering of essential oil yield and composition in mint by altering expression of deoxyxylulose phosphate reductoisomerase and menthofuran synthase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98 8915–8920. 10.1073/pnas.141237298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin D. M., Aubourg S., Schouwey M., Daviet L., Schalk M., Toub O., et al. (2010). Functional annotation, genome organization and phylogeny of the grapevine (Vitis vinifera) terpene synthase gene family based on genome assembly, FLcDNA cloning, and enzyme assays. BMC Plant Biol. 10:226 10.1186/1471-2229-10-226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munoz-Bertomeu J., Arrillaga I., Ros R., Segura J. (2006). Up-regulation of 1-deoxy-D-xylulose-5-phosphate synthase enhances production of essential oils in transgenic spike lavender. Plant Physiol. 142 890–900. 10.1104/pp.106.086355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagegowda D. A., Gutensohn M., Wilkerson C. G., Dudareva N. (2008). Two nearly identical terpene synthases catalyze the formation of nerolidol and linalool in snapdragon flowers. Plant J. 55 224–239. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03496.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieuwenhuizen N. J., Green S. A., Chen X., Bailleul E. J. D., Matich A. D., Wang M. Y., et al. (2013). Functional genomics reveals that a compact terpene synthase gene family can account for terpene volatile production in apple. Plant Physiol. 161 787–804. 10.1104/pp.112.208249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieuwenhuizen N. J., Wang M. Y., Matich A. J., Green S. A., Chen X., Yauk Y. K., et al. (2009). Two terpene synthases are responsible for the major sesquiterpenes emitted from the flowers of kiwifruit (Actinidia deliciosa). J. Exp. Bot. 60 3203–3219. 10.1093/jxb/erp162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohgami S., Ono E., Horikawa M., Murata J., Totsuka K., Toyonaga H., et al. (2015). Volatile glycosylation in tea plants: sequential glycosylations for the biosynthesis of aroma β-primeverosides are catalyzed by two Camellia sinensis glycosyltransferase. Plant Physiol. 168 464–477. 10.1104/pp.15.00403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pechous S. W., Whitaker B. D. (2004). Cloning and functional expression of an (E, E)-α-farnesene synthase cDNA from peel tissue of apple fruit. Planta 219 84–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picone J. M., Clery R. A., Watanabe N., MacTavish H. S., Turnbull C. G. N. (2004). Rhythmic emission of floral volatiles from Rosa damascena semperflorens cv. ‘Quatre Saisons.’ Planta 219 468–478. 10.1007/s00425-004-1250-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reuveni M., Sagi Z., Evnor D., Hetzroni A. (1999). β-glucosidase activity is involved in scent production in Narcissus flowers. Plant Sci. 147 19–24. 10.1016/S0168-9452(99)00097-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schwab W., Fischer T. C., Giri A., Wüst M. (2015). Potential applications of glucosyltransferases in terpene glucoside production: impacts on the use of aroma and fragrance. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 99 165–174. 10.1007/s00253-014-6229-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun B., Li L., Han Y., Zhu Q., Yuan W., Dong M., et al. (2012). HS-SPME-GC-MS analysis of different Osmanthus fragrans cultivars from Guilin Garden in Shanghai. J. Fujian For. Coll. 32 39–42. [Google Scholar]

- Tholl D., Chen F., Petri J., Gershenzon J., Pichersky E. (2005). Two sesquiterpene synthases are responsible for the complex mixture of sesquiterpenes emitted from Arabidopsis flowers. Plant J. 42 757–771. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02417.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vezzaro A., Krause S. T., Nonis A., Ramina A., Degenhardt J., Ruperti B. (2012). Isolation and characterization of terpene synthases potentially involved in flavor development of ripening olive (Olea europaea) fruits. J. Plant Physiol. 169 908–914. 10.1016/j.jplph.2012.01.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L., Li M., Jin W., Li S., Zhang S., Yu L. (2009). Variations in the components of Osmanthus fragrans Lour essential oil at different stages of flowering. Food Chem. 114 233–236. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2008.12.014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wen Y. Q., He F., Zhu B. Q., Lan Y. B., Pan Q. H., Li C. Y., et al. (2014). Free and glycosidically bound aroma compounds in cherry (Prunus avium L). Food Chem. 152 29–36. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.11.092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittington D. A., Wise M. L., Croteau R., Christianson D. W. (2002a). Insights into monoterpene cyclization reactions in biology: crystal structure of (+)-bornyl diphosphate synthase. Biochemistry 41:8973. [Google Scholar]

- Whittington D. A., Wise M. L., Urbansky M., Coates R. M., Croteau R. B., Christianson D. W. (2002b). Bornyl diphosphate synthase: structure and strategy for carbocation manipulation by a terpenoid cyclase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99 15375–15380. 10.1073/pnas.232591099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wildung M. R., Croteau R. B. (2005). Genetic engineering of peppermint for improved essential oil composition and yield. Transgenic Res. 14 365–372. 10.1007/s11248-005-5475-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Z., Kapteyn J., Gang D. R. (2008). A systems biology investigation of the MEP/terpenoid and shikimate/phenylpropanoid pathways points to multiple levels of metabolic control in sweet basil glandular trichomes. Plant J. 54 349–361. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03429.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xin H., Wu B., Zhang H., Wang C., Li J., Yang B., et al. (2013). Characterization of volatile compounds in flowers from four groups of sweet osmanthus (Osmanthus fragrans) cultivars. Can. J. Plant Sci. 93 923–931. 10.4141/cjps2012-333 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z., Yao W., Qian H. (2005). Effect of β-D-glucosidase on aromatic compounds of sweet osmanthus. Fine Chem. 22 924–926. [Google Scholar]

- Yauk Y. K., Ged K., Wang M. Y., Matich A. J., Tessarotto L., Cooney J. M., et al. (2014). Manipulation of flavour and aroma compound sequestration and release using a glycosyltransferase with specificity for terpene alcohols. Plant J. 80 317–330. 10.1111/tpj.12634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H. (2013). Pollination Biology of Osmanthus fragrans Lour. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Nanjing Forestry, Nanjing, 16–28. [Google Scholar]

- Zou J. J., Zhou Y., Cai X., Wang C. Y. (2014). Increase in DNA fragmentation and the role of ethylene and reactive oxygen species in petal senescence of Osmanthus fragrans. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 93 97–105. 10.1016/j.postharvbio.2014.02.015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.