Abstract

Background

Support groups for people living with HIV (PLHIV) are integrated into Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) care and treatment programs as a modality for increasing patient literacy and as an intervention to address the psychosocial needs of patients. However, the impact of support groups on key health outcomes has not been fully determined.

Methods

We searched electronic databases from January 1995 through May 2014 and reviewed relevant literature on the impact of support groups on mortality, morbidity, retention in HIV care, quality of life, and ongoing HIV transmission, as well as their cost effectiveness.

Results

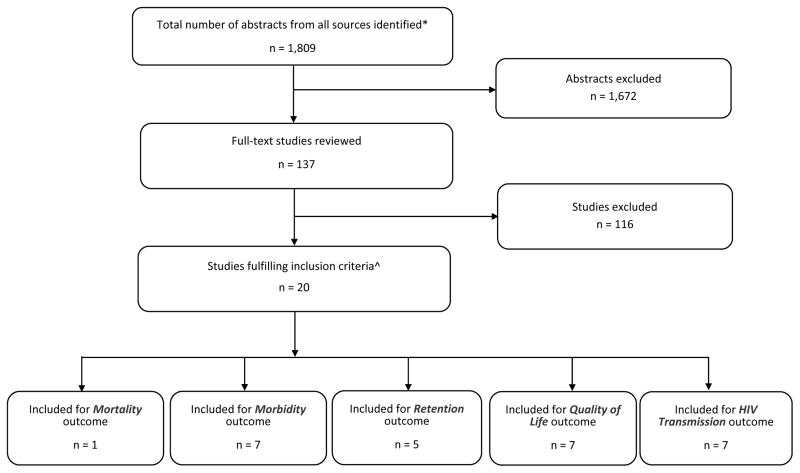

Of 1809 citations identified, 20 met inclusion criteria. One reported on mortality, seven on morbidity, five on retention in care, seven on quality of life, and seven on ongoing HIV transmission. Eighteen (90%) of the articles reported largely positive results on the impact of support group interventions on key outcomes. Support groups were associated with reduced mortality and morbidity, increased retention in care and improved quality of life. Due to study limitations, the overall quality of evidence was rated as fair for mortality, morbidity, retention in care, and quality of life, and poor for HIV transmission.

Conclusions

Implementing support groups as an intervention is expected to have a high impact on morbidity and retention in care and a moderate impact on mortality and quality of life of PLHIV. Support groups improve disclosure with potential prevention benefits but the impact on ongoing transmission is uncertain. It is unclear if this intervention is cost-effective given the paucity of studies in this area.

Keywords: Support groups, clinical, outcomes, developing countries, PLHIV

Introduction

HIV programs use support groups as an opportunity for health care workers to provide information to people living with HIV (PLHIV). HIV post-test clubs were among the first support groups to be utilized to provide support to clients who tested positive for HIV. 1 The World Health Organization (WHO) proposes support groups as an intervention to address retention and adherence among PLHIV receiving ART. 2

Both WHO and the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) promote peer support groups facilitated by trained PLHIV to address the special needs of fellow PLHIV and their partners.3, 4 Such groups serve the purpose of sharing experiences, encouraging disclosure, reducing stigma and discrimination, improving self-esteem, enhancing patients’ coping skills and psychosocial functioning and supporting medication adherence and improved retention in HIV care. 5, 6, 7 These benefits can be maximized further if the support groups are formed around specific populations such as men who have sex with men, pregnant women, adolescents, or couples in discordant relationships. Support groups are also considered an intervention in the management of mental health issues, including alcohol and other substance abuse disorders.2

Support groups are generally initiated and supported by non-governmental organizations (NGOs), civil society or community-based organizations and may convene in a health facility or in the community.

Disclosure of HIV positive status, one of the potential benefits of support groups, has broad prevention implications and is emphasized by both the WHO and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in all HIV testing protocols. 8, 9 The Mentor Mother support group model — utilizing mothers living with HIV—is a key strategy in the United Nations Global Plan for elimination paediatric AIDS by 2015 and for keeping mothers alive. 10 The Mentor Mothers is considered an effective intervention to improve maternal and infant well-being among women living with HIV. They work alongside health care workers in the clinic and at community meetings to provide health education, to promote adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART), and to promote disclosure of HIV status among other services. 11

Although the WHO and PEPFAR promote the role of support groups 2, 4, evidence of their impact on key health outcomes has not been assessed. This article presents the results of a systematic review of studies examining the evidence of impact of support groups on mortality, morbidity, retention in care, quality of life, and HIV transmission, and determining whether they are cost-effective.

Methods

This review was conducted as part of an assessment of 13 care and support interventions funded by PEPFAR. 12 Details about the interventions and methods for the review including the general search strategy are described fully in the introductory article to this supplement. 13

The review team conducted a systematic search of the literature using: Medline (via PubMed), EMBASE, Global Health, CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature), SOCA (Sociological Abstracts) and AIM (African Index Medicus) from January 1995 through May 2014 using the following Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms: HIV, community support, social support group, informal group, PLHIV network, PLHIV group, volunteer group, support group, self-help group, self-help, peer support and peer support group. These were used in addition to the general search terms described in the introductory article. 13

The authors reviewed the citations and abstracts independently and identified studies that appeared to address support group interventions and at least one of the outcomes of interest. For these “eligible” studies, full-text articles were obtained and evaluated independently by two authors. Studies that met the following criteria were “included” in the review: (1) evaluated the impact of HIV support groups; 2) were conducted in resource-limited settings; and 3) addressed one or more of the outcomes of interest -- mortality, morbidity, retention in HIV care, quality of life, or prevention of ongoing HIV transmission. Costing and cost-effectiveness outcomes where available were also considered.

The following data were abstracted from each study that fulfilled the inclusion criteria; study characteristics (citation, design, study year and year of publication); key findings (the magnitude of effect of the intervention, presented as hazard ratios, odds ratios, or relative risk and 95% confidence intervals); and the quality of evidence. For the latter, we assessed the internal and external validity and other factors and rated the quality of evidence of each study as strong, medium or weak. Qualitative studies were rated on a scale of I-IV based on methods adapted from Daly et al. 14 The methods for rating study quality are described in detail in the introductory paper in this supplement. 13

Variability in the intervention, study design, and study population precluded combining study results or meta-analysis. Instead the review team summarised results from all studies that reported on each outcome. We rated the overall quality of evidence for each outcome as good, fair or poor based on criteria developed a priori. We then rated the expected impact — based on the magnitude of effect reported in individual studies, the quality of the body of evidence (all studies addressing each outcome), and consistency of results across the studies —of the intervention on each outcome as high, moderate, low or uncertain (further details regarding rating of quality of evidence for individual studies, and quality of evidence and expected impact for each outcome can be found in the introductory paper in this supplement). 13

Results

We screened 1,809 abstracts and deemed 137 of the studies to be “eligible” (Fig. 1). Full-text articles of these 137 studies were reviewed; 20 met “inclusion” criteria. Studies that were not “included” either did not address support groups as an intervention or did not report on any of the outcomes of interest. Characteristics of the 20 included studies are presented in Table 1. Six articles reported on multiple outcomes while 14 addressed one outcome of interest (Table 1). The majority of studies were conducted in sub-Saharan Africa: South Africa, n=7 15, 18, 22, 26, 32, 35, 36 ; Kenya, n=2 23, 30; Mozambique, n=2 17, 17; and one each from Nigeria 25, Rwanda 24, Tanzania 21, Uganda 31 and Zimbabwe. 27 Two studies were conducted in Vietnam 33, 34; the remaining two reported multi-country results. 19, 20

Figure 1. Study flow diagram.

Total number of studies identified; screened; eligible and included in the systematic review of support groups for People Living with HIV January 1990- May 2014.

* Duplicate citations removed.

^ Numbers below in outcome section add up to more than 20 as some studies addressed more than one outcome.

Table 1.

Assessment of individual studies on support groups (SGs) by outcome

| Study Characteristics | Key Findings (Magnitude of effect (HR, OR, RR, RD & 95% CI) or other description) | Quality of evidence for individual studies | Evidence from Economic Evaluation (Yes or No; | Comments | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Validity (Good, Fair, or Poor) | Quality of Evidence (Strong, Medium, Weak) | ||||||||

| Citation | Study Design | Study Period, Country | Participants and outcomes | Internal | External | ||||

| Mortality | |||||||||

| Decroo J, et al. 17 | Cohort | 2/2008–12/2012 Mozambique | 5729 community adherence group (CAG) members | Mortality rates among 5729 CAG members was, 2.1 per 100 person-years (PYs). Of the 5729 adult CAG members, only 208 (3.6%) died after a median follow-up time of 19 months (IQR 10–29). Factors associated with LTFU and mortality were presented together. |

Fair | Good | Medium | No data | There was no comparison group; instead the authors in their discussion quoted mortality from a cohort in Mozambique, 17.4% (14.9–20.0) were known to have died (Wandeler et al). |

| Morbidity | |||||||||

| Wouters E, et al. 15 | Prospective cohort | 2004–2007, S. Africa | 268, Assessed community support (CHWs, SGs, Treatment buddies on VL, CD4) | At 12 months, SG participants were significantly more likely (β 0.12, P <0.001) to have an undetectable viral load and a CD4 cell count above 200 cells/mL than those who did not participate in a SG. Similar outcomes were maintained 24 months after enrolment (β 0.13, P < 0.01) | Fair | Good | Medium | No data | SG meetings were at the clinic-67.3%, church-6.0%, home of a SG member-9.7%, hospice-3.9% Most met once a week-59.6%, 21.2% met 2–3 times/month 19.2% only once a month. VL |

| AchiengL, et al. 23 | Prospective observational cohort | 11/2009–4/2010, Kenya | 301 assigned to various adherence interventions incl. SGs. End points: time to treatment failure, stoppage of ART; death; or loss to follow-up | Time to treatment failure was longer in patients participating in SGs (448 days vs. 337 days, P, 0.001). SGs were associated with better adherence (89% vs. 82%, P = 0.05) and risk of treatment failure was significantly reduced by SGs (HR = 0.43, P = 0.003), the impact being higher with the number of SG sessions attended (3 vs. 2, p=0.01p=0.01). Women were more likely than men to be retained (74% vs. 6%, p=0.027) | Fair | Fair | Medium | No data | |

| Dageid, W, et al. 18 | Mixed methods- Qualitative & Quantitative, program evaluation | 2003–2005, South Africa | 44 Kudu SG Members were compared to 23 non-members | SG membership was associated with statistically significant reduction in; somatic symptoms [10.54 to 7.08 (p=0.05)], anxiety and insomnia [10.35 to 7.96 (p= 0.05)]; and social dysfunction [6.38 to 2.46 (p=0.01)], but a non-significant decrease in depression scores [4.85 to 3.38, (P>0.05); while non-SG members showed only non-significant reductions on somatic scores on the somatic scale and social dysfunction scale but an increase in scores for anxiety, insomnia and for depression respectively | Poor | N/A | Weak | No data | Results from the quantitative component are limited by the small sample size |

| Elul, B, et al. 24 | Cross sectional survey | 9/2008–4/2009, Rwanda | 1472 participants at 20 sites. 53% were enrolled in SGs. Outcomes; adherence and viral load | Participating in an association of PLHIV was associated with decreased risk of non-adherence and of having detectable viral load (AOR = 0.60, 95% CI [0.42–0.87]). After adjusting for duration on ART, age and CD4 count at ART initiation, participating in an association for PLHIV showed an inverted association with having a viral load of more than 40 copies/mL (AOR= 0.39, 95% CI [0.24–0.65]). | Fair, | Good | Medium | No data | The article did not directly report on morbidity or mortality but adherence and VL |

| Kaaya, S, et al. 21 | Unblinded RCT | 10/2001 – 2/2004, Tanzania | 331, randomized to SG (n= 168) and control (n =163) | A SG intervention was associated with a marginal reduction in depressive symptoms. Fewer women in the intervention (60%) were depressed compared to control (73%), RR=0.82, 95% CI, 0.67–1.01 (p= 0.066). There was a 20% increase in disclosure among women in the intervention arm compared with those in the control arm (56% vs. 46%), RR=1.2, 95% CI: 0.91–1.6, (p= 0.19). 88% of SG participants were satisfied with results of disclosure versus 62% in the control arm (RR 1.4, 95% CI: 1.1–1.8, p0.004). | Fair | Fair | Strong | No data | Over 30% randomized to intervention did not initiate intervention or SOC. Intervention lasted only six weeks. |

| Ndu, A, et al. 25 | Cross Sectional | 6/2007 Nigeria | 122 ART clinic attendees | Participants who belonged to a SG (only 46.2%) were less likely to be depressed than those who did not (66.7% vs. 54.3% P=0.236) (not statistically significant) | Poor | Poor | Medium | No data | Causality between symptoms of anxiety and depression and their correlates could not be firmly established. |

| Pappin M, et al. 26 | Cross Sectional | 2007–08, S. Africa | 716 starting ART at 12 public health facilities | Participating in a SG was associated with decreased symptoms of depression (OR = 0.21, CI 0.05–0.99) | Poor | Fair | Medium | ||

| Retention in care | |||||||||

| Decroo, J, et al. 16 | Observational Cohort Study | 2/2008–5/2010, Mozambique | 1384 CAG members, program data | During follow up 1301 patients still remained in community groups, 1269 (97.5%) were remaining in care, 30 (2%) had died, and 2 (0.2%) were LTFU. Proportion of patients LTFU was lower (0.1%, range 0–0.5%) than the Mozambique national average (15%) and that reported in the literature (1.2–26%). Mortality was low. There was no comparison group. Only 3.5% decided to transfer back to conventional care. | Poor | Fair | Medium | No data | |

| Decroo J, et al. 17 | Same as above. Longer follow up | 2/2008–12/2012, Mozambique | 5729 CAG members, program data (No comparison) | Long term retention was very high (91.8%) at 4 years of follow-up. Retention at one year on ART was 97.7% (95% CI 97.4–98.2); at 2 years, 96.0% (95% CI 95.3–96.6); at 3 years, 93.4% (95% CI 92.3–94.3); and at 4 years, 91.8% (95% CI 90.1–93.2). Overall attrition was 2.2/100 PYs (3.9%); mortality and LTFU rates were 2.1 and 0.1/100 PYs respectively compared to; 5/100 PYs among patients more than 2 years on ART in Sub-Saharan Africa (Fox & Rosen 2010); 19.8 per 100 PYs in Mozambique [27]; and 48.6% at 3 years [38] | Poor | Fair | Medium | No data | |

| Wouters E, et al. 37 | Prospective cohort/program data | 2004–2007, S. Africa | 268 patients enrolled in the public sector ART. No statistical measures reported | Having a treatment buddy, CHW, or participation in SG at 6 months positively influenced patient retention at time 12 months. Having a TrB, CHW, or participation in a SG at 12 months positively influenced patient retention at 24 months after starting ART. | Fair | Good | Medium | No data | Findings may reflect the inherent differences between the patients lost and those retained. |

| Lamb MR, et al. 19 | Cohort study | Jan 1, 2005–Sept 30, 2011 | 312,335 patients (10–24 yrs) at 160 HIV clinics: Kenya-41, Mozambique-31, Rwanda-41, Tanz-47 | Pre-ART: There was no association between Pre-attrition and attending clinics that offered adolescent SGs (Data not reported). ART: Youth attending clinics that offered adolescent SGs experienced lower attrition after ART initiation than youth attending clinics not offering these services (AHR=0.73, 95% CI: 0.52–1.0) | Good | Good | Medium | No data | |

| Muchedzi A et al. 27 | Cross-sectional | 6–8,2008 Zimbabwe | 147 PMTCT clients were interviewed and included in the survey. | Women enrolled in a SG were twice as likely to access care and treatment (OR = 2.34, 95% CI 1.13–4.88). On multivariate analysis, access to HIV care and treatment were associated with participants enrolled in a SG (OR = 2.34, CI 1.13–4.88). | Poor | Poor | Medium | No data | Assessed factors associated with enrolment in care and not morbidity directly |

| Quality of life | |||||||||

| Dageid W, et al. 18 | Mixed methods Program evaluation | See above | 44 Kudu SG Members and 23 non-members |

From FGDs: SG members reported that they had lived positively 35/44, felt stronger (50%) compared to non-members. Negative findings included gossip and stigmatization from other SG members and from the community and inadvertent disclosure. From Surveys: (40/44)90% of SG members reported that the SG had a positive impact, all SG participants felt stronger. Statistically significant improvement in scales from baseline for somatic symptoms, anxiety and insomnia and social dysfunction, see above. |

Poor | N/A | Weak, | No data | |

| Gillet HJ, et al. 30 | Qualitative | 5–6/2009, Kenya | 21 HIV-positive women | Women believed they had gained emotional support at their SG. | N/A | N/A | Weak | No data | |

| Kim YM, et al. 31 | Qualitative | 2007–2008, Uganda | 113 key informants, 16 FGDs (11 with SG members & 5 with non-SG community members). | SGs helped to reduce the stigma and discrimination that previously deterred PLHIV from seeking care. The project helped transform the role and self-image of PLHIV. PLHIV trained as network support agents (NSAs) compensated for staffing shortages at health facilities, reducing client wait time and increasing attention to each client. | N/A | N/A | Weak | No data | More people in the community accessed care with potential mortality & prevention benefits. NSAs also conducted home visits to encourage adherence and retention |

| Mfecane S, et al. 32 | Qualitative | 2/2006–5/2007, S. Africa | 25 men attending a rural S. African health facility | SGs enabled most participants to accept their HIV diagnosis, resist HIV stigmatization, and gain confidence that they would live longer despite having HIV. Helped participants to dispense of feelings of helplessness and suicidal tendencies. Enabled adherence to ARVs. Negative effects: Men felt pressure was imposed on them in the SGs to be disciplined and responsible patients. | N/A | N/A | Weak | No data | Some negative comments: SGs assist in the transformation of PLHIV into docile and passive bodies in order to facilitate their adherence to treatment |

| Mundell JP, et al. 22 | Quasi-experimental | 4/2005 – 9/2006, S. Africa | 361 pregnant women, (144 participated in the 10-session weekly psychosocial SG [intervention] and 217 who declined (control) | At 2- and 8-month follow-ups, the rates of disclosure in the intervention group was significantly higher than in the comparison group (p <0.001). At follow up, the intervention group displayed higher levels of active coping (t-score, t = 2.68, p < 0.05) and lower levels of avoidant coping (t =2.02, p < 0.05) compared to control, and those who attended at least half of the intervention sessions exhibited improved self-esteem (t = 2.11, p < 0.05). | Poor | Poor | Medium | No data | |

| Nguyen TA, et al. 33 | Qualitative | 2004–2007 Vietnam | 30 women access HIV-related postnatal care | Involvement in self-help groups improved the women’s self-esteem, increased knowledge about HIV, and had a positive effect on both felt and enacted stigma from family, community, and health services. Many mothers in the group actively sought care and started to help others to access services. | N/A | N/A | Weak | No data | |

| Oosterhoff P, et al. 34 | Qualitative methods applied to a Case Study | 4/2004 –6/2007, Vietnam | 153 (84 HIV+ women 47 HIV+ men, and 22 household members) | By participating in SGs, PLHIV gained access vital social, medical and economic support and services for themselves, their children and partners. They gained self-confidence, and learned to communicate with their peers and voice their needs to service providers. More members were able to access ARVs including for PMTCT. | N/A | N/A | Weak | Most outcomes were programmatic and not individual. | |

| HIV Transmission | |||||||||

| Gaede B, et al. 35 | Descriptive cross sectional | Year not specified, S. Africa | 262 HIV positive pregnant and non-pregnant women (165 urban and 97 rural) | The findings supported positive benefits of counseling and SGs among women. Membership in a SG also showed a positive association with condom use (Spearman’s correlation Coeff=0.394; p<0.001). The overall SG membership was only 12% (7% in urban and 21% in rural (p =0.001) | Poor | Fair | Medium | ||

| Hardon A, et al. 20 | Descriptive cross sectional | 2008–09, Burkina Faso, Kenya, Malawi, Uganda | 3659 for the quantitative component and 157 for the qualitative component | Membership to a SG was strongly associated with not disclosing to partners (uRR 0.53 [95% CI 0.39–0.72], p < 0.001) even after adjustment (aRR 0.67 [95% CI 0.51–0.88], p = 0.004). In the qualitative component, interviews and focus group discussions suggested that SGs advocated caution when disclosing to partners. | N/A | N/A | Medium | Few HIV positive members answered open ended questions | |

| Skogma S, et al. 36 | Mixed (qualitative &quantitative) | 9–12, 2003, South Africa | 144 (118 women and 26 men) two HIV clinics in central Johannesburg | The disclosure rate was generally high (92%). No significant differences in disclosure between the patients with only pre- and post-test counseling vs. those attending professional counseling or SGs, and to those not attending any form of counseling. | Poor | Fair | Medium | In the setting, disclosure was high (92%). Sample size used in the study may have been too small | |

| Wouters E, et al. 37 | Prospective cohort/routine data | 2004–2007, S. Africa | 268 patients enrolled in the public sector ART. | Public disclosure at six-month follow-up was significantly associated with bonding social capital measures including support groups Participating in an HIV/AIDS SG group at 12 months and 24 months were associated with public disclosure. (β= 0.22 and β= 0.22 respectively). |

See above | See above | See above | Potential confounders such as psychosocial and socio-behavioral factors were not available in the dataset and were not controlled for. We assumed for purposes of this review that disclosure and VL are associated with less transmission | |

| Gillet HJ, et al. 30 | Qualitative | 5–6/2009, Kenya | 21 HIV-positive women | Women gained confidence to disclose to relatives and partners after meeting other PLHIV in their SG. No data on impact of SG on disclosure to non-SG members | N/A | N/A | Weak | No data | Did not investigate the impact of support groups on disclosure to people outside the SG |

| Kim YM, et al. 31 | Qualitative | 2007–2008, Uganda | 113 key informants, 16 FGDs (11 with SG members & 5 with non-SG community members). | NSAs trained from the SGs contributed to an increase in the disclosure of HIV-positive status to spouses, family members, PLHIV group members, service providers, and community members. | N/A | N/A | Weak | No data | Disclosure to family members has prevention benefits within discordant couples |

| Kaaya, S, et al. 21 | Unblinded RCT | 10/2001 – 2/2004, Tanzania | 331, randomized to SG (n= 168) and control (n =163) | There was a 20% increase in disclosure among women in the intervention arm compared with those in the control arm (56% vs. 46%), RR=1.2, 95% CI: 0.91–1.6, (p= 0.19). 88% of SG participants were satisfied with results of disclosure versus 62% in the control arm (RR 1.4, 95% CI: 1.1–1.8, p=0.004). | Fair | Fair | Strong | No data | Intervention lasted only six weeks. |

Level of Evidence; Strong (Systematic Review/meta-analysis of RCTs with consistent findings; High-quality individual RCT), Medium (Systematic Review/meta-analysis of lower-quality clinical trials or of studies with inconsistent findings; Lower-quality clinical trial; Cohort study; Case control study or Weak (Consensus guidelines; Usual practice; Opinion; Case series) Abbreviations: SG, Support Groups; VL, Viral load; CHWs, Community Healthcare Workers; FGD, Focus Group Discussion

Most studies (18) were observational—using either a cross-sectional or cohort design (11), a qualitative (5), or a mixed methods study design (2); and two were experimental studies-- an unblinded randomised controlled study (RCT) 21 and a study using a quasi-experimental design. 22 Sample sizes ranged from 21 in a qualitative study to over 300,000 in a multi-country observational cohort. Three studies targeted only women; one recruited only men; the remaining studies (n=16) included both men and women. In addition to being enrolled in support groups, PLHIV often received other interventions, such as being seen by community health workers or being assigned treatment buddies. Table 1 presents further details on the characteristics and findings from the 20 individual studies.

Outcomes, Quality of the Evidence and Expected Impact

Mortality

One study examined the effect of support groups on mortality. Decroo et al., reporting on a Mozambique cohort, found a mortality rate among 5729 individuals enrolled in Community Adherence Groups (CAGs) of only 2.1 per 100 person-years (PYs) and a loss to follow-up (LTFU) rate of 0.1 per 100 PYs. Only 208 (3.6%) were reported as dead after a median follow-up time of 19 months (IQR 10–29). 17 The authors also reported an overall attrition of 3.9% mostly from mortality (3.7%) and the rest from LTFU (0.2%). Factors associated with attrition (both mortality and LTFU) were presented at individual and group level. At the individual level, attrition in CAGs was associated with a low CD4 count at the time of enrolment in CAG (aHR 2.28, 95% CI 1.60–3.24) and being male (aHR 1.93, 95% CI 1.48–2.51). At the group (CAG) level, lack of rotational representation by each of the different group members at the clinic (aHR 1.72, 95% CI 1.27–2.33), lack of regular CD4 count ascertainment among members of the same group (aHR 1.88 95% CI 1.18–3.00), and attending a rural (aHR 2.59, 95% CI 1.81–3.70) or district clinic (aHR 1.57, 95% CI 1.14–2.16) were associated with higher attrition. There was no comparison group.

Reviewers rated the “overall” quality of evidence for the outcome of mortality as fair. However, the expected impact on mortality was rated as moderate based on the low mortality rate among those who participated in the support groups in this study (Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of evidence from all studies by outcome

| Outcomes | Overall Quality of Evidence | Impact of the intervention | Evidence from Economic Evaluation | Comments | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Studies | Overall Quality of the Body of Evidence (Good, Fair, Poor) | i Expected Impact (High, Moderate, Low) | Number of studies | Quality of evidence from economic evaluation | ||

| Mortality | 1 [17] | Fair | Moderate | None | N/A | Some support group characteristics described in the S. Africa settings do provide some important lessons. |

| Morbidity | 7 [15, 18, 21, 23–26] | Fair | High | None | N/A | Almost all studies were cross sectional or qualitative and only demonstrate associations. Different outcomes for morbidity were used in the different studies |

| Retention in Care | 5 [15–17, 19, 27] | Fair | High | None | N/A | Results from several large cohorts demonstrate sustained retention especially in ART patients |

| Quality of Life | 7 [18, 22, 30–34, ] | Poor | Moderate | None | N/A | As reported, the studies all used different measures of quality of life. All reported outcomes would have an impact on quality of life for PLHIV directly or indirectly |

| HIV Transmission | 7 [20, 21, 30, 31, 35, 36, 37] | Poor | Uncertain | None | N/A | Three of the four studies were conducted in S. Africa, with mixed results. One study conducted elsewhere had mixed results and involved non-representative sample of participants from each country. |

The expected impact of the intervention was rated as; High=Intervention expected to have a high impact on the outcome, Moderate=Likely to have a moderate impact on the outcome, Low=Intervention expected to have a low impact on the outcome and, Uncertain=Available information is not adequate to assess estimated impact on the outcome.

Note, assessment of the expected impact of the intervention was based on published evidence. Additional considerations that would inform implementation decisions would have to take into account the cost effectiveness information and country specific contextual considerations.

Morbidity

Seven studies 15, 18, 21, 23–26 reported on the impact of support group interventions on a range of morbidity outcomes (Table 1).

Support groups were associated with reduced frequency of HIV-related symptoms— somatic symptoms, anxiety and insomnia 18 and depression 21, 25, 26. Other benefits included improved access to ART, adherence to ART and treatment success 15, 23, 24, 27, measured as time to treatment failure and reduced risk of detectable viremia or change in CD4 cell count. For example, Achieng et al. reported that time to treatment failure was longer in patients participating in support groups (448 days vs. 337 days, P=0.001). 23 Results from a South African cohort of 268 PLHIV enrolled in the public sector HIV treatment program reported participation in a support group as a predictor of treatment success (i.e. viral load < 400 copies/mL, CD4 > 200 cells/mL), during the first six, 12 and 24 months of antiretroviral therapy. 15 Support group participants were significantly more likely to have an undetectable viral load (P <0.001) and a CD4 cell count > 200 cells/mL at 12 months (P<0.01) than those who did not participate in a support group. Viral load suppression was maintained beyond 24 months after enrolment in a support group (P < 0.01). In the Muchedzi study, women tested for HIV in a prevention of mother to child transmission (PMTCT) program and enrolled in a support group were twice as likely to access care and treatment (OR = 2.34, 95% CI 1.13–4.88) although their treatment outcomes were not reported. 27 Outcomes from the remaining five studies are presented in Table 1.

Although findings from the seven studies consistently reported morbidity benefits, reviewers rated the overall quality of evidence as fair based on limitations of the included studies. Almost all were cross sectional, qualitative or had small sample sizes. In addition, different morbidity-related outcomes were reported. Nevertheless, the expected impact of support groups on reducing morbidity in PLHIV was rated as high based on significant associations between support group participation and decrease in morbidity from studies from six different countries.

Retention in Care

Five studies 15–17, 19, 27 -- two from the same Mozambique cohort [16, 16] -- reported low LTFU for patients on ART participating in support groups. Decroo et al. reported high retention with approximately 97.5% patients remaining in care for a median follow-up period of 12.9 months (range 8.5–14 months) 16 and 91.8% at 4 years. 17 Overall, the authors reported that attrition in the cohort was lower than the national 12 month average for Mozambique (15%) 28 and lower still than rates reported in the literature for sub-Saharan Africa (1.2–26%). 29 A large study with more than 300,000 participants aged 10–24 years from four sub-Saharan countries showed that youth participating in support groups provided by clinics experienced slightly lower attrition after ART initiation (AHR=0.73, 95% CI: 0.52–1.0); in the pre-ART period, the authors reported no significant associations between attrition and participation in support groups or other adolescent friendly services—availability of adolescent peer educators, or education on high-risk substance abusing behaviour. 19 Higher retention among support group participants was also reported among patients on ART in South Africa 15 and among women enrolled in the PMTCT program in Zimbabwe 27 (Table 1).

Reviewers categorized the quality of evidence for this outcome as fair. All five studies were observational. Sample sizes were small for two of the studies 15, 27 and the findings from the larger study 19 are not generalizable beyond the 10–24 year age group. Lack of a comparison group in two studies16, 17 and other methodological limitations affected the quality of evidence for this outcome. The expected impact of support groups on retention was rated as high for patients on ART but uncertain for pre-ART patients (Table 2).

Quality of Life

Seven studies—five qualitative 30–34, one quasi experimental 22 and another using mixed methods 18 — reported associations between membership and/or attendance at support groups and several measures of quality of life (QOL) (Table 1). Measures varied by study and included reported improvement in symptoms, improved confidence and self-esteem, better coping skills, and perceived reduction in stigma. The authors reported that support group participation enabled patients to seek care 31 and start ARVs. 34 Other benefits reported by Kim et al. were spill-over effects to the community in which HIV-infected persons who were not in support groups were encouraged to seek care.31 While the benefits were mostly positive, Mfecane et al. reported that a cohort of men who attended support groups felt that participation imposed pressure to conform in a way that negatively affected their perception of masculinity. 32 Dageid et al. reported negative effects such as inadvertent disclosure of HIV-positive status and gossip and stigmatization from other support group members and/or the community. 18

Reviewers categorized the quality of evidence for this outcome as poor. Four of the studies were qualitative 30, 31, 33, 34 and most had small sample sizes. One reported only on men 32 and three only on women 22, 30, 33 limiting generalizability of the findings. Despite the limitations in some of the studies the expected impact on quality of life was rated as moderate (Table 2) based on consistently positive results on quality of life across studies.

HIV transmission

Seven studies 20, 21, 30, 31, 35–37 reported on outcomes which may directly or indirectly impact HIV transmission, such as risky sexual behaviour and disclosure of HIV-positive status to sex partners. Three of the seven studies were conducted in South Africa 15, 35, 36 (Table 1). Gaede et al. reported positive associations between attendance at support groups and health behaviours and condom use. 35 Four studies 20, 21, 36, 37 reported mixed results regarding the association between support group participation and disclosure of HIV status: Skogmar found no significant difference in disclosure rates between those who attended only pre/post-test counselling (standard of care) and those who received either professional counselling or participated in support groups. 36 Woulters reported that assistance of community health workers and support group participation resulted in disclosure of HIV status to non-family members only in the second year of implementation of the program; however, the impact of support groups alone was not reported. 37 Hardon et al., in a mixed methods study involving participants from four African countries (Burkina Faso, Kenya, Malawi, Uganda), showed that membership in a support group was associated with not disclosing to partners for fear of stigma — the experience of prejudice and discrimination as the consequence of being HIV- positive. 20 Additionally, although an unblinded randomized control study conducted in Tanzania reported a 20% increase in disclosure for support group participants compared to controls, the difference was not statistically significant (RR=1.2, 95% CI: 0.91–1.6, P=0.19) and 12% of those who gave feedback about the disclosure reported negative reactions such as anger, blame and being told to leave the household. 21 Two articles reported an association between support group attendance and increased disclosure to spouses and other family members. 30, 31

Reviewers categorized the quality of evidence from the seven studies as poor and the expected impact on HIV transmission as uncertain.

Discussion

We identified 20 studies from low- and middle-income countries which evaluated the impact of support groups on mortality, morbidity, retention in care, quality of life or HIV transmission. No studies reported costing or cost-effectiveness data. The studies were primarily from sub-Saharan Africa and varied in study design, target population and sample size.

The review found largely positive results. Although limited by the quality of the included studies, the data suggest potential benefit of support groups on key health outcomes. We rated the expected impact of support groups as an intervention in PLHIV as high in terms of reducing morbidity and improving retention in care. Support groups also have the potential to influence mortality, quality of life and prevention of ongoing HIV transmission. Specific positive benefits associated with support group membership include enhancing treatment success and improving the quality of life through equipping PLHIV with coping skills.

With development of community-based care models in some settings, support groups could provide an opportunity for PLHIV to share experiences and become more engaged in their care. Given the severe human resource challenges in sub-Saharan Africa, specifically the shortage of trained health care providers 38, support groups can play an increasingly larger role in care models, particularly with regard to retaining HIV-infected persons in care. Based on success of the pilot program developed by Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) and provincial health officials in Mozambique reported in this review 16, 17, the Mozambique Ministry of Health is scaling up CAGs nationally.

We did not specifically search for adherence as an outcome in this review. However five studies reported increased adherence to ART 15, 23, 24, 32 associated with support group participation. In Wouters et al., 89.9% of support group members reported that support group meetings helped create a forum for sharing knowledge and experiences, some of which related to taking medications. In Mozambique PLHIV enrolled in support groups reported increased adherence. 16

Two studies described negative outcomes. In a South Africa study, male participants in support groups felt under pressure to conform to a lifestyle that was not consistent with established gender roles 32, while a large mixed methods study with participants from Burkina Faso, Kenya, Malawi and Uganda showed that membership in a support group was associated with non-disclosure to partners. 19 These issues will need to be addressed to maximize the potential of support groups as an intervention.

Limitations

Conclusions of this review should be interpreted with caution given the methodological limitations and relatively small number of studies. The majority of the studies were observational, eight employed qualitative methods, three studies enrolled less than 70 participants each 17, 29, 32, one study included only men 32 and three recruited only women. 22, 27, 30 Therefore, the findings may not be generalizable to the broader community and to other patient populations. Additionally, PLHIV participating in support groups often received other interventions. The impact of the other interventions or their combination may have influenced the results reported in this review. Evidence from this review may not be adequate to inform major policy changes regarding the role of support groups.

Research Gaps

Although this review has provided useful information regarding support groups, there are information gaps. Which patients are most in need of support group participation? What venues are optimal, and how do these depend on the populations participating? Who should lead the support groups? What specific considerations should be given to newly diagnosed patients, men, women, key population groups, and those starting ART?

Cost-effectiveness of the intervention is an outstanding issue. None of the studies included costing data; nor were they designed to test effectiveness for the outcomes under review. The Mozambique CAG pilot was successful in part because over a quarter (28%) of the members shared the cost of transport. It is unclear if other types of support groups would be feasible and sustainable in their respective settings. Programs already underway such as the national rollout of CAGs in Mozambique should be rigorously evaluated. Data from these evaluations could be useful for national governments and donor funding decisions.

Programmatic Considerations for Implementation

It is apparent from this review that support groups have the potential to play an important role in HIV care and treatment programs, in terms of having impact on key health outcomes and in retaining HIV-infected persons in care. They may also provide an alternative care model towards attaining universal access to ART in settings where long distances to health facilities, shortage of human resources and waiting times remain barriers to HIV care. Implementation issues and challenges were beyond the scope of this review; however, several merit discussion: membership and access; resources and sustainability; monitoring and evaluation, and models of implementation.

Regarding membership, not all patients need or want to participate in support groups, and health care facilities may not be able to accommodate all patients who might benefit from a support group intervention. Therefore it is important to target support group resources to those who might benefit the most. For example, support groups targeting key populations could be useful in settings with high levels of stigma and discrimination directed towards PLHIV. In this review, most support groups were formed to support patients on ART. Programs for pre-ART patients should be developed to determine whether these patients might benefit from support group participation. Implementers should identify motivators for attendance and also, perhaps, criteria to determine when participation might no longer be necessary. The needs for patients in urban vs. rural HIV care programs may differ significantly.

Secondly, resources are needed to start and maintain support groups-- both human and infrastructural. Support group programs require physical meeting space away from crowded health facilities; they may require phone credit, transportation support, and refreshments during meetings, among other needs. Training in facilitation skills and capacity building are especially important to foster free expression and to encourage full participation. The actual costs associated with running support groups are difficult to estimate in part due to lack of accurate data on the number of PLHIV who currently access services. The comparative evaluation of different models would enrich our knowledge of which support group models to scale up. Programs should understand how best to make support groups self-sustaining and less dependent on donor funding. Early lessons from Mozambique suggest that the CASG support group model is self-sustaining and could potentially be replicated in other settings.

Thirdly, for donors and ministries of health that fund support groups, monitoring and evaluation metrics are important to assess the value of support group interventions. Community level HIV indicators, including those that measure linkage between facilities and the community and retention in support group programs will be important to develop to monitor success and to ensure accountability.

Lastly, support groups are yet to be formalized as standard practice in HIV care and treatment programs; inadequate data as evident in this literature review are one of the challenges. Models for such programming need to be explored. For example, a model that links community-based support groups to an assigned health facility in a hub-and-spoke fashion with a formalized system for bidirectional referral would be useful to explore.

Conclusion

Implementing support groups in PLHIV is likely to have an impact on morbidity and retention in care and has the potential to improve quality of life and mortality. Additional research and operational lessons are needed to maximize the benefits of support groups as an integral component of HIV care and treatment.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

“This research has been supported by the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the United States Agency for International Development (USAID).”

The authors would like to acknowledge the following individuals who participated in the evidence review: From the CDC Library, Gail Bang and Emily Weyant who conducted the literature searches and; Ratanang Balisi from USAID (Botswana) and Peter Vranken from CDC (South Africa) who helped screen citations.

Footnotes

Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and should not be construed to represent the positions of the U.S. Department of State’s Office of the U.S. Global AIDS Coordinator, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or the United States Agency for International Development or the U.S. Federal Government.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose

References

- 1.AIDS Information Centre (AIC) AIDS Information Centre 2004 annual report. Kampala, Uganda: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO. Consolidated guidelines on the use of antiretroviral drugs for treating and preventing HIV infection: recommendations for a public health approach. 2013 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO. Operations Manual for Delivery of HIV Prevention, Care and Treatment in High-Prevalence, Resource-Constrained Settings (Edition 1 for field testing and country adaptation) Chapter 4: Community. 2008 The full operations manual is available at: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/imai/operations_manual/en/ [PubMed]

- 4.OGAC. Technical Considerations Provided by PEPFAR Technical Working Groups for FY 2014 COPS and ROPS. Washington, DC: OGAC; 2013. http://www.pepfar.gov/documents/organization/217761.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peterson J, Rintamaki L, Brashers D, Goldsmith D, Neidig J. The Forms and Functions of Peer Social Support for People Living with HIV. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 2012;23:294–305. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2011.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haberer JE, Kahane J, Kigozi I, Emenyonu N, Hunt P, et al. Real time-adherance monitoring for HIV antiretroviral therapy. AIDS Behav. 2010;14:1340–1346. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9799-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krebs DW, Chi BH, Mulenga Y, Morris M, Cantrell RA, et al. Community-based follow-up to late patients enrolled in district wide program for antiretroviral therapy in Lusaka, Zambia. AIDS Care. 2008;20:311–317. doi: 10.1080/09540120701594776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.UNAIDS. Counselling and HIV/AIDS. Geneva: UNAIDS Best Practice Collections; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 9.MMWR. Revised Guidelines for HIV Counselling testing and referral. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 2012. 2002;50:1–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.UNAIDS. Global plan towards the elimination of new HIV infections among children by 2015 and keeping their mothers alive. Vol. 2011. Geneva: Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS; 2011. Countdown to zero. http://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/unaidspublication/2011/20110609_JC2137_Global-Plan-Elimination-HIV-Children_en.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rotheram-Borus MJ, Richter LM, van Heerden A, van Rooyen H, Tomlinson M, et al. A Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial Evaluating the Efficacy of Peer Mentors to Support South African Women Living with HIV and Their Infants. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(1):e84867. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0084867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.PEPFAR. [Accessed August 1, 2014];The US President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief: Five-Year Strategy (Annex) 2009 Dec; at http://www.pepfar.gov/about/strategy/prevention_care_treatment/index.htm.

- 13.Kaplan J, Hamm T, Forhan S, et al. The Impact of HIV Care and Support Interventions on Key Outcomes in Low and Middle-Income Countries: A Literature Review. Introduction J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015 doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000495. issue:XXX-XXX. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Daly J, Willis K, Small R, Green J, Welch N, et al. A hierarchy of evidence for assessing qualitative health research. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2007;60(1):43–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wouters E, Damme WV, Loon FV, Rensburg Dv, Meulemans H. Public-sector ART in the Free State Province, South Africa: community support as an important determinant of outcome. Social Science & Medicine. 2009;69(8):1177–85. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Decroo, Telfer B, Biot M, et al. Distribution of antiretroviral treatment through self-forming groups of patients in Tete province, Mozambique. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2011;56(2):39–44. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182055138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Decroo B, Koole O, Remartinez D, dos Santos N, Dezembro S, Jofrisse M, et al. Four-year retention and risk factors for attrition among members of community ART groups in Tete, Mozambique. Trop Med Int Health. 2014;19:514. doi: 10.1111/tmi.12278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dageid W, Duckert F. The process of evaluating a capacity-building support initiative for HIV positive South Africans. Evaluation & Program Planning. 2007;30(4):381–91. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2007.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lamb MR, Fayorsey R, Nuwagaba-Biribonwoha H, Viola V, Mutabazi V, et al. High attrition before and after ART initiation among youth (15–24 years of age) enrolled in HIV care. AIDS. 2013;28:559–68. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hardon A, Gomez GB, Vernooij E, Desclaux A, Wanyenze RK, Ky-Zerbo O, Kageha E, et al. Do support groups members disclose less to their partners? The dynamics of HIV disclosure in four African countries. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:589. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaaya SF, Blander J, Antelman G, Cyprian F, Emmons KM, Matsumoto K, Chopyak E, et al. Randomized controlled trial evaluating the effect of an interactive group counselling intervention for HIV-positive women on prenatal depression and disclosure of HIV status. AIDS Care. 2013;25(7):854–62. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2013.763891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mundell JP, Visser MJ, Makin JD, Kershaw TSC, Jeffery B, Sikkema KJ. The Impact of Structured Support Groups for Pregnant South African Women Recently Diagnosed HIV Positive. Women & Health. 2011;51(6):546–65. doi: 10.1080/03630242.2011.606356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Achieng L, Musangi H, Ong’uti S, Ombegoh E, Bryant L, Mwiindi J, Smith N, et al. An observational cohort comparison of facilitators of retention in care and adherence to anti-retroviral therapy at an HIV treatment center in Kenya. PloS one. 2012;7(3):e32727. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Elul B, Basinga P, Nuwagaba-Biribonwoha H, Saito S, Horowitz D, et al. High Levels of Adherence and Viral Suppression in a Nationally Representative Sample of HIV-Infected Adults on Antiretroviral Therapy for 6, 12 and 18 Months in Rwanda. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(1):e53586. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053586. doi:10.1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ndu AC, Arinze-Onyia SU, Aguwa EN, Obi IE. Prevalence of depression and role of support groups in its management: a study of adult HIV/AIDS patients attending HIV/AIDS Clinic in a tertiary health facility in South-eastern Nigeria. Journal of Public Health and Epidemiology. 2011;3(4):182–6. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pappin M, Wouters E, Booysen FL. Anxiety and depression amongst patients enrolled in a public sector antiretroviral treatment programme in South Africa: a cross-sectional study. BMC public health. 2012;12:244. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Muchedzi A, Chandisarewa W, Keatinge J, Stranix-Chibanda L, Woelk G, Mbizvo E, Shetty AK. Factors associated with access to HIV care and treatment in a prevention of mother to child transmission programme in urban Zimbabwe. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2010;13:38. doi: 10.1186/1758-2652-13-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Auld A. Treatment outcomes of HIV-infected adults enrolled in the national antiretroviral therapy program—Mozambique, 2004–2007. HIV/AIDS Implementers’ Meeting; 2008; Windhoek, Namibia. Abstract 1608. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fox MP, Rosen S. Patient retention in antiretroviral therapy programs up to three years on treatment in sub-Saharan Africa, 2007–2009: systematic review. Tropical medicine & international health. 2010;15:1–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02508.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gillett HJ, Parr J. Disclosure among HIV-positive women: The role of HIV/AIDS support groups in rural Kenya. African Journal of AIDS Research. 2011;9(4):337–44. doi: 10.2989/16085906.2010.545633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim YM, Kalibala S, Neema S, Lukwago J, Weiss DC. Meaningful involvement of people living with HIV/AIDS in Uganda through linkages between network groups and health facilities: an evaluation study. Psychology Health & Medicine. 2012;17(2):213–22. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2011.592844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mfecane S. Negotiating therapeutic citizenship and notions of masculinity in a South African village. African Journal of AIDS Research. 2011;10(2):129–38. doi: 10.2989/16085906.2011.593375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nguyen TA, Oosterhoff P, Ngoc YP, Wright P, Hardon A. Self-help groups can improve utilization of postnatal care by HIV-infected mothers. JANAC: Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 2009;20(2):141–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2008.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oosterhoff P, Anh NT, Yen PN, Wright P, Hardon A. HIV-positive mothers in Viet Nam: using their status to build support groups and access essential services. Reproductive Health Matters. 2008 Nov;16(32):162–70. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(08)32408-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gaede BM, Majeke SJ, Modeste RR, Naidoo JR, Titus MJ, Uys LR. Social support and health behavior in women living with HIV in KwaZulu-Natal. SAHARA J: Journal of Social Aspects of HIV/AIDS Research Alliance. 2006;3(1):362–8. doi: 10.1080/17290376.2006.9724862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Skogmar S, Shakely D, Lans M, Danell J, Andersson R, Tshandu N, Oden A, et al. Effect of antiretroviral treatment and counselling on disclosure of HIV-serostatus in Johannesburg, South Africa. AIDS Care - Psychological and Socio-Medical Aspects of AIDS/HIV. 2006 Oct 01;18(7):725–30. doi: 10.1080/09540120500307248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wouters E, Meulemans H, Rensburg HCJv. Slow to share: social capital and its role in public HIV disclosure among public sector ART patients in the Free State province of South Africa. AIDS Care. 2009;21(4):411–21. doi: 10.1080/09540120802242077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.World Health Organization (WHO) Treat, Train Retain. The AIDS health workforce plan. Report on the Consultation on AIDS Human Resources for Health; Geneva. May 11–12, 2006; Jun 25, 2011. Available from: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/meetingreports/ttr/en/index.html. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.