Abstract

Objective

This study examined the prevalence and correlates of suicidal ideation and behavior (SI/B) among adolescents receiving bariatric surgery.

Method

Charts of 206 adolescents receiving bariatric surgery were reviewed. Cases with SI/B (current/lifetime reported at baseline or event occurring in the program n= 31, 15%) were case-matched on gender, age, and surgery type to 31 adolescents reporting current or past psychiatric treatment, and 31 adolescents denying lifetime SI/B or psychiatric treatment.

Results

Before surgery, adolescents with SI/B reported significantly lower total levels of health-related quality of life (p=0.01) and greater depressive symptoms (p=0.004) in comparison to candidates who never received psychiatric treatment. No significant differences were found between groups for the change in depressive symptoms or body mass index following surgery.

Conclusions

As in studies of adults, a notable subset of adolescents receiving bariatric surgery indicated pre- or post-operative SI/B. It is critical that clinicians evaluate and monitor adolescent patients undergoing bariatric surgery for risk of SI/B.

INTRODUCTION

Overweight and obesity among children and adolescents is a serious international public health concern (Flood et al., 2015; van Jaarsveld & Gulliford, 2015). Obese youth are at risk of developing significant and debilitating medical and psychological complications, such as Type 2 diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, cancer, low self-esteem and decreased quality of life (Biro & Wien, 2010; Morrison, Shin, Tarnopolsky & Taylor, 2014). Although data on the proportion of children classified as overweight or obese suggest a stabilization in overall prevalence, increases have been noted in more severe forms of obesity (Skinner & Skelton, 2014). This trend is concerning, as behavioral interventions for severely obese youth tend to produce modest reductions in weight that are not maintained in the several years following treatment (e.g., Kalarchian et al., 2009; van der Baan-Slootweg et al., 2014). Similar to studies of adults (e.g., Bondada, Jen & Deugarte, 2011), the results of research to date suggest the safety and efficacy of bariatric procedures for weight loss among severely obese adolescents (e.g., Beamish, Johansson & Olbers, 2014; Jen et al., 2010; O’Brien et al., 2010; Zitsman et al., 2015). However, despite some recent increases in the use of these surgeries (Jen et al., 2010), adolescents still constitute only a very small proportion of the procedures done in the United States (Tsai, Inge & Burd, 2007). Given these initial promising results, it is likely that the number of procedures in adolescents will continue to increase, and additional research on this age group will be needed to examine the developmental context of bariatric surgery outcomes.

Adolescents show increased impulsive responding and reward seeking. In comparison to children and adults, adolescents demonstrate increased risk-taking behaviors and neural activity in reward-processing regions (Blakemore & Robbins, 2012; Steinberg, 2008), which may relate to an imbalance of functionally mature subcortical systems relative to immature prefrontal cortical control systems (Casey, Jones & Somerville, 2011). Consistent with this pattern, impulsive behaviors including suicidal ideation and behaviors (plans, attempts or completions) heighten during adolescence, particularly among teenagers with underlying psychopathology such as depression and anxiety (Creemers, Scholte, Engels, Prinstein & Wiers, 2012; Fergusson, Woodward & Horwood, 2000; Gianetta et al., 2012). Severely obese adolescents may be at even greater risk by virtue of their medical and weight status. Specifically, adolescents with interpersonal or medical problems often report a lower quality of life and risk suicidal ideation and behaviors (Lewinsohn, Rohde & Seeley, 1996). In obese adolescents, risk for dangerous behaviors are increased more than 2 times among youth who perceive themselves to be overweight as their normal weight and overweight peers who do not perceive themselves to be overweight (Dave & Rashad, 2009; Mather, Cox, Enns & Sareen, 2009). Additionally, overweight and obese adolescents report feelings of hopelessness significantly more often than their normal weight peers, a feeling that is often linked to suicidal ideation and behaviors (Martyn-Nemeth & Penckofer, 2012).

A growing literature on adults receiving bariatric surgery suggests that suicidal ideation and behaviors may be elevated both pre- and post-operatively (Mitchell et al., 2013; Sansone, Wiederman, Schumacher & Routsong-Weichers, 2008; Windover, Merrell, Ashton & Heinberg, 2010). However, few studies have focused on these behaviors among adolescents receiving weight-loss surgery, despite data suggesting that low self-esteem, depression, and suicidal behaviors are observed in this population (Giannetta et al., 2011; Nemiary, Shim, Mattox & Holden, 2012; Sysko, Zakarian, Devlin, Bush & Walsh, 2011; Zeller, Roehrig, Modi, Daniels & Inge, 2006). For example, Duffecy and colleagues (2008) found 32% of adolescents presenting for bariatric surgery reported depression, 13% reported current suicidal ideation, 40% reported past suicidal ideation, and 13% reported past suicide attempts. Overall, 25% of the adolescent patients seeking bariatric surgery reported having engaged in self-harm (Duffecy, Bleil, Labott, Browne, & Galvani, 2008).

Given the limited data on such risky behaviors among adolescents undergoing bariatric surgery, the primary purpose of this study was to examine the prevalence and correlates of suicidal ideation and behaviors in this population. A secondary study aim was to examine clinically-relevant pre-and post-operative correlates, such as weight trajectories and depressive symptoms, in subgroups of obese adolescents to determine whether suicidal ideation and behaviors impacted surgical outcomes.

METHODS

Participants

Participants were adolescents enrolled in the Center for Adolescent Bariatric Surgery (CABS) program at Morgan Stanley Children’s Hospital of New York Presbyterian/Columbia University Medical Center (CUMC). The CABS program utilized an FDA approved Investigational Device Exemption (IDE) to perform laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding (LAGB) on patients under the age of 18. The core eligibility requirements CABS program include: 1) enrolled between the ages of 14 and 17 years; 2) BMI > 40 kg/m2 or BMI > 35 kg/m2 with serious medical comorbidities (e.g. Type II diabetes, obstructive sleep apnea); 3) history of obesity five years or more, including unsuccessful efforts at weight loss treatment (e.g. nutritional and medical management) for one year, and seen by providers at CUMC for at least six months; 4) for females, suitable contraception and not planning to become pregnant over the year subsequent to surgery; 5) absence of medical contraindications (e.g., anomalies of the gastrointestinal tract); and 6) absence of current self-induced vomiting behavior. For the LAGB, written informed assent and consent were provided by adolescents and their parent(s) in a protocol approved by the CUMC Institutional Review Board (IRB). Adolescents and parent(s) who were not participants in the LAGB protocol completed written assent/consent for pre- and post-operative self-report questionnaires in a study reviewed and approved by the New York State Psychiatric Institute IRB.

Identification of Groups

Two methods were used to identify candidates with current or past significant suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, hospitalizations, and completed suicide (SI/B group). For SI/B occurring prior to entering the CABS Program or at the time of initial psychiatric interview, baseline evaluations were reviewed (see below). For SI/B occurring while the adolescent was followed by the CABS team, clinical charts were reviewed to identify notes from surgery or psychiatry staff that would indicate an adolescent to be included in the SI/B group. Both types of SI/B were incorporated into the reference group for this study because data demonstrates that suicidal ideation severity and intensity, lifetime history of suicide attempt, and lifetime history of non-suicidal self-injury are significant independent predictors of future suicide attempts among adolescents (Horwitz, Czyz & King, 2014). This finding indicates the value of including both past behaviors and current thoughts into suicide risk formulation and evaluating whether this type of SI/B affects surgical outcomes. As events occurring while patients were enrolled in the CABS program require different clinical management, these adolescents are considered in greater detail in the sections that follow. Reference group candidates (candidates with current or past psychiatric treatment, or candidates without suicidal ideation or behavior or psychiatric treatment) were matched 1:1 using as many of several predefined characteristics as possible: age, gender, ethnicity, and type of surgery.

Assessments

All adolescents were evaluated by the surgical team, and eligible candidates were referred for a psychiatric evaluation. Adolescents and at least one parent completed both the clinical interview and a series of self-report questionnaires.

Clinical Characteristics

Psychological evaluations were completed by a psychiatrist or psychologist to assess candidates on motivation for surgery, compliance with program instructions, weight history, eating disorder psychopathology and other current or past DSM-IV Axis I disorders and psychiatric symptoms (including but not limited to suicidal ideation and behavior) as well as any current or past psychiatric (psychotherapy or medication) treatment. As described in prior publications, the clinical interview also obtained school and social history as well as demographic (e.g., age, sex, education) and family information (see Sysko et al., 2011 for a more complete description).

Body Mass Index

Weight and height were measured both pre- and post-surgery (e.g., at 1-month intervals before surgery and 3-month intervals post-operatively) during visits with surgery and/or psychiatry research staff. As self-reported weights following bariatric surgery appear accurate (Christian, King, Yanovski, Courcoulas & Belle, 2013), when clinician measured weight not available, participant reported weight was used.

Self-Report Measures

Questionnaires were administered to adolescents by bachelor’s-level research assistants either in the clinic setting or remotely through an online database. Information was collected at a baseline time-point pre-operatively and then post-operatively at three, six, nine, 12, 18, and 24 months following surgery.

Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q) and Questionnaire on Eating and Weight Patterns-Revised (QEWP-R)

Participants completed either the EDE-Q, QEWP-R, or both. The EDE-Q is a 38-question measure used to assess eating disorder symptoms over a 28-day period prior to completion (Fairburn & Beglin, 1994). The QEWP-R is a 28-item measure designed to assess eating disorder symptoms and weight and dieting history (Spitzer, Yanovski & Marcus, 1993). Loss of control over eating episodes were coded if objective bulimic episodes were reported on either the EDE-Q or QEWP-R, or subjective bulimic episodes by EDE-Q.

Measures of Depressive Symptoms

Three measures evaluated baseline depressive symptoms: the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; Beck, Ward, Mendelson, Mock & Erbaugh, 1961; n=73), the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D; n=25), and the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS; n=28). Participants completed either one or two of these measures, depending on when they enrolled in the CABS program with some patients providing data on multiple measures of depressive symptoms (n=4: all measures, n=2: BDI and CES-D, n=19: CES-D and DASS, and n=5: BDI and DASS). The BDI is a 21-question measure of depressive symptoms (Beck et al., 1961). The measure has been shown to have high internal consistency in prior studies (Beck, Steer & Carbin, 1988), and in the current study (α = 0.90). The CES-D is a 20-question measure used to rate the frequency of depressive symptoms in the previous week on a four-point scale. The scale has good internal reliability (Radloff, 1991), is comparable to the BDI for detecting depression (Zich, Attikisson & Greenfield, 1990), and demonstrated good internal consistency in this sample (α = 0.92). The DASS is a 21-question measure with one subscale used to measure degree of depressive symptoms over the past week on a four-point scale (Henry & Crawford, 2005). This subscale also had adequate internal consistency among adolescents included in the current study (α = 0.87). On all three measures, higher scores indicate more depressive symptoms. These assessments were also repeated three and 12 months following surgery.

Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory (PedsQL)

The PedsQL is a 23-item measure used to assess health-related quality of life. The version used for this study was a reliable and valid adolescent-specific (ages 13–18) version (Varni, Seld & Kurtin, 2001) with higher scores indicating better quality of life.

Statistical Analyses

At the time of the retrospective chart and record review (August 2014), a total of 143 patients had received LAGB (n=103 under the FDA approved IDE) and 63 adolescents had received gastric sleeve resections; these 206 charts were examined. Additional charts were available for participants who were enrolled in the CABS program but never received surgery, or had not yet received surgery at the time of the review, but these records were not examined because of the focus on post-surgery outcomes in this study. The data were analyzed using the Statistic Package for Social Sciences, version 22 (SPSS, Chicago, IL) and MPlus, version 7.3. Chi-square tests (χ2) analyzed categorical variables. One Way and Repeated Measure Analyses of Variance (ANOVAs) were used to evaluate differences among the three groups of adolescents and Bonferroni post-hoc tests were applied. Means are reported ± standard deviations.

Post-surgery changes in depressive symptoms were analyzed using latent growth curve modeling (LGCM), a method used previously with adolescent candidates (Sysko et al., 2012), which is superior for maximizing statistical power and simultaneously modeling both within- and between-subject differences (Bollen & Curran, 2006). We used multiple indicator models by defining negative affect as a latent variable measured by total scores on the BDI, CES-D, or DASS. We held measurement of the latent variable invariant (factor loadings held constant) for the repeated measures of negative affect (baseline, 3 months post-surgery, and 12 months post-surgery). The expectation maximization algorithm and a maximum likelihood estimator were used to model missing data, which assumed data were missing at random (McKnight, McKnight, Sidani & Figueredo, 2007). Preoperative covariates hypothesized to relate to either postoperative psychological symptoms or BMI were evaluated in all models using baseline levels of the respective independent variables. Goodness of fit for models assuming linear growth, nonlinear growth (i.e., addition of a quadratic term), piecewise growth, and the combination of nonlinear and piecewise growth were compared. The best fitting model, evaluated by Akaike Information Criteria (AIC), sample-size adjusted Bayesian Information Criteria (aBIC), and Comparative Fit Index (CFI), subsequently examined post-surgery changes in a series of conditional LGCMs. Lower AIC and aBIC indicate better fitting models. Chi square tests for nested models examined the significance of linear versus nonlinear models and unconditional versus conditional models.

RESULTS

Demographic and Clinical Information

As the included cases were matched on ethnicity, age, and surgery type, there were no significant differences in these variables across groups. Average BMI was also not different by group. Means, standard deviations, percentages and analyses comparing the three groups are summarized in Table 1. Of the 31 adolescents in the reference group, 16 participants had history of significant suicidal ideation, six had a history of a suicide attempt, one was hospitalized for a suicide attempt pre-surgery while participating in the CABS program, one was hospitalized for suicidal ideation after evaluation but before surgery, five were hospitalized for a post-surgery suicide attempt while followed in the program, and two completed suicide after receiving surgery. At the pre-surgical psychiatric evaluation, a greater proportion of adolescents with SI/B (64.5%) met criteria for current DSM-IV Axis I diagnoses compared to those with a history of psychiatric treatment (35.5%) and to those with no such treatment (12.5%) [χ2(2) = 18.3, p< 0.001]. Nine cases that indicated SI/B subsequent to the baseline psychiatric evaluation were further examined: five (55.5%) reported some past or current suicidal thoughts or behaviors in the evaluation, and four (45.5%) endorsed no previous SI/B at evaluation; additional detail about these cases is provided in Table 2.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics

| Reference Group (n=31) | Psychiatric Tx History (n=31) | No Psychiatric Tx History (n=31) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 16.0 ± 1.2 | 16.0 ± 1.0 | 15.9 ± 1.1 | NS |

| BMI | 46.9 ± 6.1 | 48.8 ± 7.8 | 46.7 ± 8.0 | NS |

| Laparoscopic Adjustable Gastric Banding | 23 (74.2%) | 25 (80.6%) | 24 (77.4%) | NS |

| Female | 26 (83%) | 26 (83%) | 26 (83%) | NS |

| Race | ||||

| Caucasian | 8 (25.8%) | 8 (25.8%) | 9 (29%) | NS |

| Hispanic | 17 (54.8%) | 15 (48.4%) | 17 (54.8%) | |

| African American | 3 (9.7%) | 5 (16.1%) | 4 (12.9%) | |

| Other | 3 (9.7%) | 3 (9.7%) | 1 (3.2%) | |

| Current DSM-IV Dx | 20 (64.5%) | 11 (35.5%) | 3 (9.7%) | <0.001 |

| Past DSM-IV Dx | 27 (87.1%) | 16 (51.6%) | 4 (12.9%) | <0.001 |

Tx = Treatment

Table 2.

Characteristics of Individual Cases with Suicidal Ideation/Behaviors (SI/B) while Enrolled in the Center for Adolescent Bariatric Surgery

| Case | Pre-Operative SI/B | Pre-Operative Psychiatric Tx | Pre-Operative Psychiatric Diagnoses |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | + | + | Mood Dis Not Otherwise Specified |

| 2 | + | + | Dissociative Dis Not Otherwise Specified |

| 3 | + | + | Bipolar Dis |

| 4 | − | + | N/A |

| 5 | − | − | Adjustment Dis |

| 6 | − | − | Past Major Depressive Dis |

| 7 | + | + | Major Depressive Dis |

| 8 | − | − | Generalized Anxiety Dis |

| 9 | + | + | Oppositional Defiant Dis/Past Anxiety Dis Not Otherwise Specified |

Tx = Treatment; Dis= Disorder

Baseline Self-Report Assessments

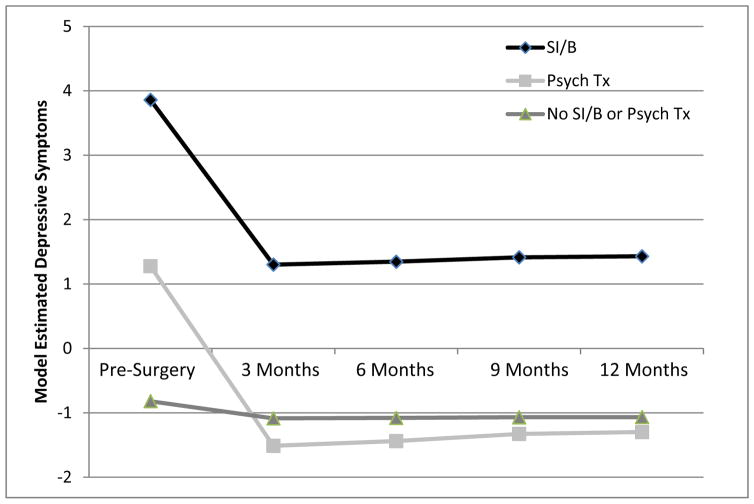

Adolescents in the SI/B group reported lower total levels of health-related quality of life on the PedsQL (64.3 ± 16.0) in comparison to candidates who had never received psychiatric treatment [76.7 ± 17.7; F(2, 89)=4.8, p=0.011], but did not differ from those with a history of psychiatric treatment (74.2 ± 16.4). Similarly, in comparison to the candidates without any history of SI/B or treatment, adolescents with SI/B reported significantly more depressive symptoms by self-report (βintercept = −5.5, SE = 1.9, p= 0.004; see Figure 1). No significant differences were found between groups for the presence of loss of control eating (objective and subjective binge episodes) at baseline, with nine (36.0%) in the SI/B group, nine (39.1%) in the psychiatric treatment group, and five (19.2%) in the no SI/B or psychiatric treatment group endorsing these episodes.

Figure 1. Model Estimated Means of Latent Depression Symptoms Pre- and Post-Surgery, Controlling for Gender.

Note. SI/B= Adolescent Candidates with Current/Past Suicidal Ideation or Behavior, Psych Tx= Adolescent Candidates with Current/Past Psychiatric Treatment, No SI/B or Psych Tx= Adolescent Candidates without any Suicidal Ideation or Behavior or Psychiatric Treatment

Post-Surgery Depression Assessments and BMI

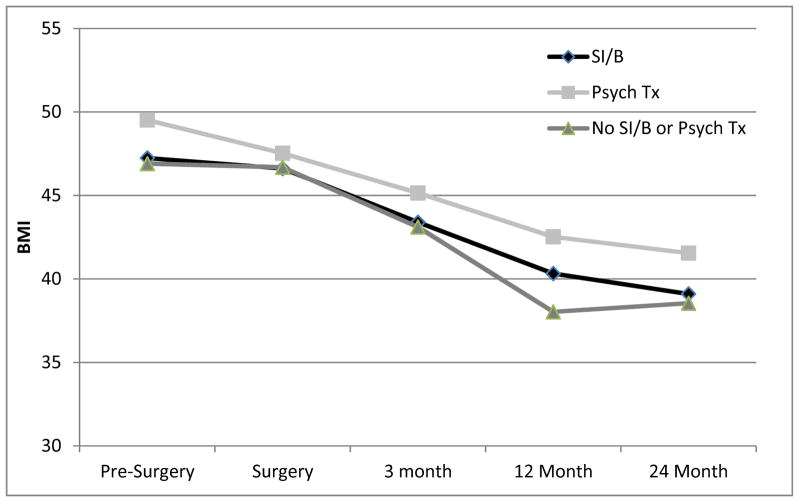

Depressive symptoms decreased significantly over the 12 months post-surgery, with male candidates demonstrating fewer improvements in comparison to their female counterparts (βslope = 1.8, SE = 0.72, p = 0.01). After controlling for baseline depressive scores, no differences were found in the slope of change in symptoms between the three groups (see Figure 1). Total BMI also significantly decreased over the two years following surgery, with changes occurring between baseline and surgery, and baseline and six months post-surgery. No further improvements were seen following this time-point, and the groups did not show a difference in weight outcomes (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Model Estimated Body Mass Index (BMI; kg/m2) by Group Adjusted by Gender.

Note. SI/B= Adolescent Candidates with Current/Past Suicidal Ideation or Behavior, Psych Tx= Adolescent Candidates with Current/Past Psychiatric Treatment, No SI/B or Psych Tx= Adolescent Candidates without any Suicidal Ideation or Behavior or Psychiatric Treatment

DISCUSSION

With an accumulating body of literature suggesting the clinical importance of suicidal thoughts and behaviors in adult bariatric surgery patients (e.g., Mitchell et al., 2013; Sansone, et al., 2008; Windover et al., 2010), it is critical to understand any potential role of receiving surgery on the presence of these behaviors. As there is limited data on suicidal ideation or behaviors among adolescent bariatric samples, the current study aimed to conduct a preliminary examination of the prevalence and any correlates of suicidal ideation and behavior within a cohort of youth. Several notable differences were identified using information from pre-surgical psychiatric evaluations and self-report questionnaire data among adolescents reporting SI/B and candidates with no indication of past/present SI/B or psychiatric treatment. Specifically, the SI/B group reported more current and past DSM-IV diagnoses, lower quality of life, and more depressive symptoms at baseline in comparison to the control group, who reported no history of psychiatric treatment. The presence of loss of control over eating episodes and frequency of these episodes did not significantly differ across groups.

Although pre-surgery differences were noted, the impact of SI/B was not observed following surgery with regard to BMI or depressive symptoms. As in prior studies (e.g., Sysko et al., 2012), all groups lost a significant amount of weight and experienced improved mood over the year or two years following surgery. The lack of effect of SI/B status on BMI or self-reported depressive symptoms is consistent with the conflicting data on the importance of mood disorders in predicting weight change from bariatric surgery in adults (Black, Goldstein & Mason, 2003; Delin, Watts & Bassett, 1995; Dixon, Dixon & O’Brien, 2001; Hsu, Benotti & Dwyer, 1998; Kalarchian et al., 2008; Ryden, Karlsson, Sullivan, Torgerson & Taft, 2003; Semanscin-Doerr, Windover, Ashton & Heinberg, 2010) and studies documenting that despite overall reductions in psychiatric symptoms and increases in quality of life following surgery in adolescents and adults, an important subset of patients will continue to experience depressive symptoms or disorders, suicidal ideation or behaviors, alcohol and substance use, or disturbances in eating behaviors (de Zwaan et al, 2011; Hayden, Murphy, Brown & O’Brien, 2014). Thus, SI/B status prior to surgery, at the time of the initial psychiatric evaluation, or while enrolled in the surgical program, appeared not to have a substantial effect on expected outcomes among this cohort of adolescents.

Although the post-surgery course of adolescents with SI/B does not appear atypical, one clinical characteristic of the group with these cognitions/behaviors warrants attention. The majority of the cases with SI/B reported past ideation or behaviors at time of their initial psychiatric evaluation; however, a significant proportion of the cases had no history of these problems or any clear proximal risk for SI/B. It may therefore not be possible to closely monitor all adolescent candidates at risk for SI/B on the basis of information gathered prior to surgery, and surgical programs may need to incorporate ongoing screening for youth who continue to return for follow-up visits following surgery.

This study had several limitations. Although the groups were equal in size, the overall sample size, and statistical power, was limited based on the number of adolescents in the reference group. In addition, little information was collected post-operatively in the clinical records of the surgery staff on suicidal ideation and behavior. Data on hospitalizations and completed suicides was obtained by the surgical team, but only for those participants who returned to the medical center or whose parents contacted the program staff. Thus, no consistent data were recorded on ideation or behaviors not requiring psychiatric or medical attention. Future research on adolescents receiving bariatric surgery should utilize a prospective design to better understand the course of suicidal thoughts or behaviors in the years after bariatric surgery.

In conclusion, as in studies of adults, this study suggests that a notable subset of these adolescents have pre- or post-operative SI/B, which does not appear to substantially affect the usual course following bariatric surgery. It is therefore critical that clinicians evaluate and monitor patients undergoing bariatric surgery for risk of suicidal ideation and behavior in both the pre- and post-operative periods, and ensure that youth pursuing surgery who are at risk for these behaviors are receiving appropriate care.

Acknowledgments

FINANCIAL SUPPORT: Dr. Sysko is supported, in part, by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grant DK088532-01A1.

The authors thank B. Timothy Walsh, M.D., and the members of the Center for Adolescent Bariatric Surgery team.

References

- Beamish AJ, Johansson SE, Olbers T. Bariatric surgery in adolescents: What do we know so far? Scandinavian Journal of Surgery. 2014;104:24–32. doi: 10.1177/1457496914553150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Carbin MG. Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory: Twenty-five years of evaluation. Clinical Psychology Review. 1988;8:77–100. doi: 10.1016/0272-7358(88)90050-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–571. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biro FM, Wien M. Childhood obesity and adult morbidities. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2010;91:1499S–1505S. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2010.28701B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black DW, Goldstein RB, Mason EE. Psychiatric diagnosis and weight loss following gastric surgery for obesity. Obesity Surgery. 2003;13:746–751. doi: 10.1381/096089203322509327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blakemore SJ, Robbins TW. Decision-making in the adolescent brain. Nature Neuroscience. 2012;15:1184–1191. doi: 10.1038/nn.3177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollen KA. Latent variables in psychology and the social sciences. Annual Review of Psychology. 2002;53:605–634. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bondada S, Jen HC, Deugarte DA. Outcomes of bariatric surgery in adolescents. Current Opinion in Pediatrics. 2011;23:552–556. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e32834a1b49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey B, Jones RM, Somerville LH. Braking and accelerating of the adolescent brain. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2011;21:21–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christian NJ, King WC, Yanovski SZ, Courcoulas AP, Belle SH. Validity of self-reported weights following bariatric surgery. JAMA. 2013;310:2454–2456. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creemers DH, Scholte RH, Engels RC, Prinstein MJ, Wiers RW. Implicit and explicit self-esteem as concurrent predictors of suicidal ideation, depressive symptoms, and loneliness. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 2012;43:638–646. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2011.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dave D, Rashad I. Overweight status, self-perception, and suicidal behaviors among adolescents. Social Science & Medicine. 2009;68:1685–1691. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Zwaan M, Enderle J, Wagner S, Mühlhans B, Ditzen B, Gefeller OA, et al. Anxiety and depression in bariatric surgery patients: a prospective, follow-up study using structured clinical interviews. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2011;133:61–68. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delin CR, Watts JM, Bassett DL. An exploration of the outcomes of gastric bypass surgery for morbid obesity: Patient characteristics and indeces of success. Obesity Surgery. 1995;5:159–170. doi: 10.1381/096089295765557962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon JB, Dixon ME, O’Brien PE. Pre-operative predictors of weight loss at 1-year after Lap-Band surgery. Obesity Surgery. 2001;11:200–207. doi: 10.1381/096089201321577884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffecy J, Bleil ME, Labott SM, Browne A, Galvani C. Psychopathology in adolescents presenting for laparoscopic banding. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2008;43:623–625. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elder KA, Wolfe BM. Bariatric surgery: A review of procedures and outcomes. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:2253–2271. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.03.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG, Beglin SJ. Assessment of eating disorders: interview or self-report questionnaire? International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1994;16:363–370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Woodward LJ, Horwood LJ. Risk factors and life processes associated with the onset of suicidal behaviour during adolescence and early adulthood. Psychological Medicine. 2000;30:23–39. doi: 10.1017/s003329179900135x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flood TL, Zhao YQ, Tomayko EJ, Tandias A, Carrel AL, Hanrahan LP. Electronic health records and community health surveillance of childhood obesity. American Journal of Preventative Medicine. 2015;48:234–240. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giannetta MM, Betancourt LM, Brodsky NL, Wintersteen MB, Romer D, Giannetta JM, Hurt H. Suicidal ideation and self-harm behavior in a community sample of preadolescent youth: A case-control study. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2012;50:524–526. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayden MJ, Murphy KD, Brown WA, O’Brien PE. Axis I disorders in adjustable gastric band patients: The relationship between psychopathology and weight loss. Obesity Surgery. 2014;24:1469–1475. doi: 10.1007/s11695-014-1207-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry JD, Crawford JR. The short-form version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21): Construct validity and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2005;44:227–239. doi: 10.1348/014466505x29657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horwitz AG, Czyz EK, King CA. Predicting future suicide attempts among adolescent and emerging adult psychiatric emergency patients. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2014;28:1–11. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2014.910789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu LK, Benotti PN, Dwyer J, Roberts SB, Saltzman E, Shikora S, Rand W, et al. Nonsurgical factors that influence the outcome of bariatric surgery: A review. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1998;60:338–346. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199805000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jen HC, Rickard DG, Shew SB, Maggard MA, Slusser WM, Dutson EP, DeUgarte DA. Trends and outcomes of adolescent bariatric surgery in California, 2005–2007. Pediatrics. 2010;126:e746–753. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-0412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalarchian MA, Levine MD, Arslanian SA, Ewing LJ, Houck PR, Cheng Y, Marcus MD. Family-based treatment of severe pediatric obesity: Randomized, controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2009;124:1060–1068. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-3727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalarchian MA, Marcus MD, Levine MD, Soulakova JN, Courcoulas AP, Wisinski MS. Relationship of psychiatric disorders to 6-month outcomes after gastric bypass. Surgery for Obesity and Related Diseases. 2008;4:544–549. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn PM, Rohde P, Seeley JR. Adolescent suicidal ideation and attempts: Prevalence, risk factors, and clinical implications. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 1996;3:25–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2850.1996.tb00056.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Loux TJ, Haricharan RN, Clements RH, Kolotkin RL, Bledsoe SE, Haynes B, Harmon CM. Health-related quality of life before and after bariatric surgery in adolescents. Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 2008;43:1275–1279. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2008.02.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovibond PF, Lovibond SH. The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1995;33:335–343. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(94)00075-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martyn-Nemeth PA, Penckofer S. Psychological vulnerability among overweight/obese minority adolescents. Journal of School Nursing. 2012;28:291–301. doi: 10.1177/1059840511430508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mather AA, Cox BJ, Enns MW, Sareen J. Associations of obesity with psychiatric disorders and suicidal behaviors in a nationally representative sample. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2009;66:277–285. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2008.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKnight PE, McKnight KM, Sidani S, Figueredo AJ. Missing Data: A Gentle Introduction. New York: Guilford Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell JE, Crosby R, de Zwaan M, Engel S, Roerig J, Steffen K, Wonderlich S. Possible risk factors for increased suicide following bariatric surgery. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2013;21:665–672. doi: 10.1002/oby.20066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison KM, Shin S, Tarnopolsky M, Taylor VH. Association of depression & health related quality of life with body composition in children and youth with obesity. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2014;172C:18–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemiary D, Shim R, Mattox G, Holden K. The relationship between obesity and depression among adolescents. Psychiatric Annals. 2012;42:305–308. doi: 10.3928/00485713-20120806-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien PE, Sawyer SM, Laurie C, Brown WA, Skinner S, Veit FJB, et al. Laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding in severely obese adolescents: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2010;303:519–526. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olbers T, Gronowitz E, Werling M, Marlid S, Flodmark CE, Peltonen M, Marcus C. Two-year outcome of laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass in adolescents with severe obesity: results from a Swedish Nationwide Study (AMOS) International Journal of Obesity. 2012;36:1388–1395. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2012.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff L. The use of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale in adolescents and young adults. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1991;20:149–166. doi: 10.1007/BF01537606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratcliff MB, Reiter-Purtill J, Inge TH, Zeller MH. Changes in depressive symptoms among adolescent bariatric candidates from preoperative psychological evaluation to immediately before surgery. Surgery for Obesity and Related Diseases. 2011;7:50–54. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2010.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryden A, Karlsson J, Sullivan M, Torgerson JS, Taft C. Coping and distress: What happens after intervention? A 2-year follow-up from the Swedish Obese Subjects (SOS) study. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2003;65:435–442. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000041621.25388.1a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sansone RA, Wiederman MW, Schumacher DF, Routsong-Weichers L. The prevalence of self-harm behaviors among a sample of gastric surgery candidates. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2008;65:441–444. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2008.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semanscin-Doerr DA, Windover A, Ashton K, Heinberg LJ. Mood disorders in laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy patients: does it affect early weight loss? Surgery for Obesity and Related Diseases. 2010;6:191–196. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2009.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner AC, Skelton JA. Prevalence and trends in obesity and severe obesity among children in the United States, 1999–2012. JAMA Pediatrics. 2014;168:561–566. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spear LP. Heightened stress responsivity and emotional reactivity during pubertal maturation: Implications for psychopathology. Developmental Psychopathology. 2009;21:87–97. doi: 10.1017/s0954579409000066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer R, Yanovski S, Marcus M. The questionnaire on eating and weight patterns-revised (QEWP-R) New York: New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L. A social neuroscience perspective on adolescent risk-taking. Developmental Reviews. 2008;28:78–106. doi: 10.1016/j.dr.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sysko R, Devlin MJ, Hildebrandt TB, Brewer SK, Zitsman JL, Walsh BT. Psychological outcomes and predictors of initial weight loss outcomes among severely obese adolescents receiving laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2012;73:1351–1357. doi: 10.4088/JCP.12m07690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sysko R, Zakarin EB, Devlin MJ, Bush J, Walsh BT. A latent class analysis of psychiatric symptoms among 125 adolescents in a bariatric surgery program. International Journal of Pediatric Obesity. 2011;6:289–297. doi: 10.3109/17477166.2010.545411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai WS, Inge TH, Burd RS. Bariatric surgery in adolescents: recent national trends in use and in-hospital outcome. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine. 2007;161:217–221. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.3.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Baan-Slootweg O, Benninga MA, Beelen A, van der Palen J, Tamminga-Smeulders C, Tijssen JG, van Aalderen WM. Inpatient treatment of children and adolescents with severe obesity in the Netherlands: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatrics. 2014;168(9):807–814. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Jaarsveld CH, Gulliford MC. Childhood obesity trends from primary care electronic health records in England between 1994 and 2013: population-based cohort study. Archives of Disorders of Childhood. 2015;100:214–219. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2014-307151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varni JW, Seid M, Kurtin PS. PedsQL™ 4.0: Reliability and validity of the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory™ Version 4.0 Generic Core Scales in healthy and patient populations. Medical Care. 2001;39:800–812. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200108000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Windover AK, Merrell J, Ashton K, Heinberg LJ. Prevalence and psychosocial correlates of self-reported past suicide attempts among bariatric surgery candidates. Surgery for Obesity and Related Diseases. 2010;6:702–706. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2010.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeller MH, Inge TH, Modi AC, Jenkins TM, Michalsky MP, Helmrath M, Buncher R. Severe obesity and comorbid condition impact on the weight-related quality of life of the adolescent patient. Journal of Pediatrics. 2015;166:651–659. e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeller MH, Roehrig HR, Modi AC, Daniels SR, Inge TH. Health-related quality of life and depressive symptoms in adolescents with extreme obesity presenting for bariatric surgery. Pediatrics. 2006;117:1155–1161. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zich JM, Attkisson CC, Greenfield TK. Screening for depression in primary care clinics: The CES-D and the BDI. International Journal of Psychiatry and Medicine. 1990;20:259–277. doi: 10.2190/LYKR-7VHP-YJEM-MKM2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zitsman JL, DiGiorgi MF, Fennoy I, Kopchinski JS, Sysko R, Devlin MJ. Adolescent laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding (LAGB): prospective results in 137 patients followed for 3 years. Surgery for Obesity and Related Diseases. 2015;11:101–109. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2014.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]