Abstract

Objectives To investigate the incidence and correlates of early treatment response among youth receiving cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Methods 56 youth who participated in a randomized controlled trial of CBT for PTSD and D-cycloserine were included. Youth with PTSD symptoms below clinical cutoff after Session 4 of a 12-session protocol were classified as early treatment responders (32% of parent reports, 44.6% of child reports). Pretreatment characteristics were examined in relation to responder status. Results Lower levels of pretreatment PTSD, depression, and anxiety symptoms and fewer trauma types were related to child- and parent-reported responder status (d = .57, d = .52, respectively). Early treatment response was maintained at follow-up. Conclusions Pretreatment symptoms levels and number of traumas may play an important role in predicting early treatment response. Correlates of early treatment response may provide avenues for identifying youth who could benefit from abbreviated protocols.

Keywords: children and adolescents, cognitive behavior therapy, early treatment response, PTSD

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) has been shown to be effective at ameliorating the impact of trauma in children (Cohen et al., 2010; Silverman et al., 2008). However, traumatized children’s access to evidence-based interventions remains limited (Allen, Gharagozloo, & Johnson, 2012; Comer & Barlow, 2014). This is unfortunate as access to empirically supported PTSD treatment is likely critical in combating the impact of trauma exposure, which has been linked to a variety of health concerns (Felitti et al., 1998). With this in mind, the use of stepped care models may be beneficial in both integrating mental and physical health models and maximizing health care resources, thereby increasing access to quality care. Stepped care models initially use an abbreviated or altered intervention that requires fewer health care resources as a first “step” of treatment, and depending on the client’s response, provide additional “steps” of treatment as needed to achieve good clinical outcomes. Stepped Care Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (TF-CBT; Salloum, Robst et al., 2014; Salloum, Scheeringa, Cohen, & Storch, 2014) has been developed for children exposed to trauma based on Preschool PTSD Treatment (Scheeringa, Weems, Cohen, Amaya-Jackson, & Guthrie, 2011) and TF-CBT (Cohen, Mannarino, & Deblinger, 2006). A recent pilot study found that Step 1 of Stepped Care TF-CBT was well received by parents and related to positive outcomes (Salloum, Robst et al., 2014).

A critical question remains: Who is most likely to require only Step 1? As indicated by Salloum and colleagues (2014), not all youth will achieve good clinical outcomes with only Step 1. Further, as approximately 70% of dropouts occur before the third session of treatment (Olfson et al., 2009), rather than referring every child to Step 1 and waiting to assess treatment efficacy, it is important to identify for whom lower levels of treatment may be warranted. Conversely, those presenting with certain characteristics (e.g., high levels of symptoms) who will likely require additional treatment could be referred to the standard treatment. Yet, research that may help to guide these clinical decisions is lacking. The first task in identifying those who may be best suited for which “step” of treatment is to investigate whether any baseline characteristics are associated with early treatment response, or good clinical outcomes before the completion of a full treatment protocol. Early treatment responders are likely good candidates for whom fewer “steps” of treatment are necessary. Consequently, the aim of this study is to explore which pretreatment characteristics are associated with early treatment response. Prior research regarding PTSD treatment response may aid in the identification of candidate factors.

In treatment studies of adults with PTSD, sizable subgroups seem to demonstrate favorable outcomes before the end of treatment protocols (Rizvi et al., 2009; Stein et al., 2012). Galovski and colleagues piloted a modified cognitive processing therapy (CPT) protocol in which the number of sessions was determined by the clients’ progress and 58% of participants achieved good end-state criteria before the completion of the CPT protocol (Galovski, Blain, Elwood, Mott, & Houle, 2012). Early completers maintained treatment progress and, compared with those who participated in additional sessions, showed equivalent or better outcomes including trauma-related guilt, and quality of life. Similar studies of early response do not exist in youth; however, Deblinger, Mannarino, Cohen, Runyon, & Steer (2011) found that an eight-session shortened TF-CBT protocol was effective for youth.

Predictors of youth’s treatment response to PTSD treatment have been examined, and these factors may help identify predictors of early response. Demographic variables were not related to treatment response in two TF-CBT studies (Cohen & Mannarino, 1996; Deblinger, Mannarino, Cohen, & Steer, 2006). In children receiving either TF-CBT or client-centered therapy (CCT), Deblinger et al. (2006) found that the number of traumas and depression symptoms was related to worse treatment outcome, but only for the CCT group. Elevated levels of youth’s pretreatment PTSD symptoms have been linked with poorer treatment outcome (Nixon, Sterk, & Pearce, 2012). Elevated parental depression and abuse-related distress positively correlated with poorer treatment outcome among sexually abused preschoolers in one study (Cohen & Mannarino, 1996). Weems & Scheeringa (2013) found that while maternal depression did not predict posttreatment response, it did predict treatment relapse at 6-month follow-up. Thus, level of pretreatment symptoms and parental distress may predict treatment outcome and therefore may also be related to early treatment response.

The Current Study

The aim of the current study was to identify pretreatment factors associated with early treatment response in youth receiving CBT for PTSD, as these characteristics may be useful toward eventually guiding decision-making in Stepped Care models. This study used a sample of youth who participated in a randomized controlled trial (RCT) of CBT and D-cycloserine (DCS) for PTSD (Scheeringa & Weems, 2014). Early treatment response was operationalized as either parent’s and youth’s report of the youth’s PTSD symptoms as below clinical cutoff immediately before Session 5 of a 12-session protocol, which was before any direct traumatic event processing. Drawing from the literature broadly (Nixon et al., 2012; Weems & Scheeringa, 2013), it was expected that lower pretreatment levels of youth’s PTSD, depression, and anxiety symptoms, less rumination, shorter time between the traumatic event and treatment, fewer number of traumas, and lower parental PTSD symptoms would be related to both parent- and child-reported early treatment response. Early treatment response was expected to be maintained at the conclusion of treatment and 3-month follow-up.

Method

Participants

Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) experienced or witnessed at least one life-threatening event, (2) age 7–18 years, and (3) ≥5 PTSD symptoms with functional impairment. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) head trauma with a Glascow Coma Scale score of ≤5, (2) moderate intellectual disability, autism spectrum disorder, deafness, blindness, and foreign language speaking families, (3) acute suicidality, homicidality, or being severely disabled, (4) concurrent counseling outside of the study, (5) kidney or liver ailment, (6) epilepsy or history of seizures, (7) bipolar disorder or psychosis. Participants were allowed to remain on psychiatric medication as long as the dose remained stable throughout the study.

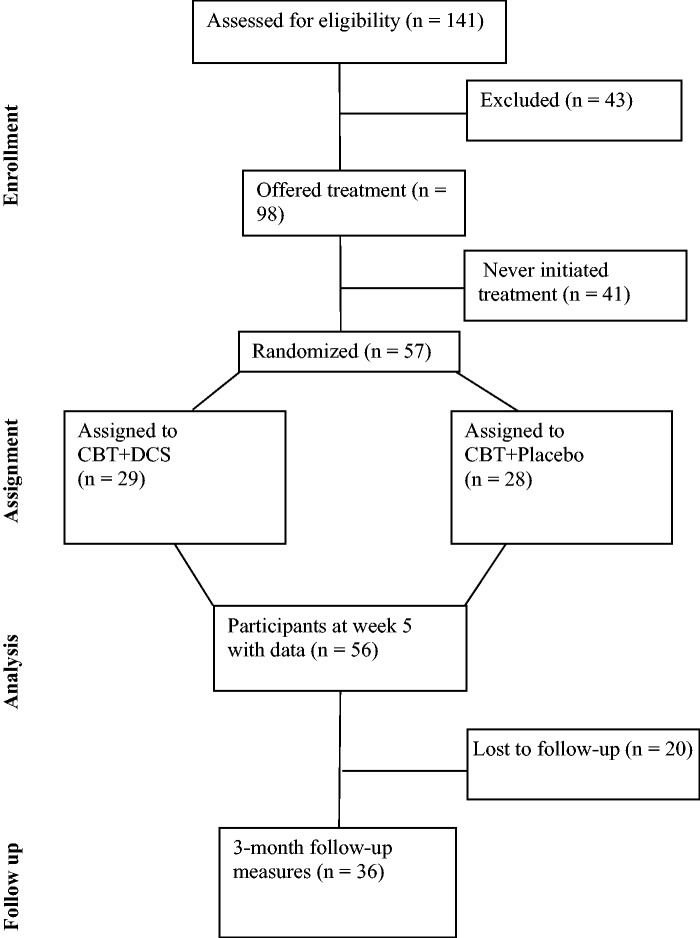

Investigators attempted to contact 644 potential participants: 30% were referred by other child-serving professionals, 14% were self-referred from advertisements, and 56% were recruited from a local Level I Trauma Center registry (see CONSORT diagram in Figure 1). Of these potential participants, 38% were not eligible due to exclusion criteria, 32% were considered initially eligible, and 30% could not be reached. Of those initially eligible, 68% were evaluated, 31% declined to participate. Approximately 70% of those evaluated met inclusion criteria and were offered treatment (n = 98), 28 of whom did not attend any therapy sessions. At Session 5, 57 participants remained in treatment (56 with Child PTSD Symptom Scale [CPSS] measures) and 47 participants completed all 12 sessions. Although a few participants had CPSS scores below the clinical cutoff at pretreatment, we chose to retain them in the analyses, as in all but two cases either the parent or youth reported symptoms above the clinical cutoff. Further, these youth were assessed by a clinician to have symptoms to warrant inclusion into a clinical trial (i.e., five PTSD symptoms with functional impairment) and excluding them may skew the sample.

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram of participant flow.

Measures

Demographics

Demographic information including age, gender, race, ethnicity, and family income were provided by the caregiver. Family income was rated categorically from 1 (<$10,000) to 10 (>$90,000) in increments of $10,000. Median household income was $30,000.

National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children-IV

The PTSD modules from the child (ages 9–17 years) and parent versions were used. The Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children-IV (DISC-IV) has moderate to good test–retest reliability, κ = .25–.92 (Shaffer, Fisher, Lucas, Dulcan, & Schwab-Stone, 2000). Despite the absence of psychometrics on the PTSD module, the DISC is the most widely used diagnostic instrument for youth. In light of the discordance between child and parent reports of PTSD symptoms (Scheeringa, Wright, Hunt, & Zeanah, 2006), a joint rating was created using the either/or rule. That is, if either the child or the parent endorsed a symptom, the symptom was counted as present. Cronbach’s α for this study was .87 for the youth version, .83 for the parent version. Eighty percent of the sample qualified for a PTSD diagnosis, whereas 19.4% had subthreshold PTSD.

The DISC-IV was also used to assess youth’s traumatic exposure. Again, disagreement was resolved between child and parent reports by coding the higher of the two ratings. Length of time between the last episode of traumatic event and the pretreatment assessment was subtracted in days. The number of traumatic events reported was summed.

Child PTSD Symptom Scale

The CPSS is a 17-item self-report measure of DSM-IV PTSD symptoms on a 4-point Likert scale (Foa et al., 2001). Clinical cutoff is ≥11. Both the parent (CPSS-P) and child (CPSS-C) versions were used and administered weekly to monitor symptoms during treatment. A joint rating was created using the either/or rule. In children aged 8–15 years, test–retest reliability 1–2 weeks later was moderate, κ = .55 (Foa et al., 2001). Psychometric properties have not been established for the parent version; however, the CPSS was chosen, as it has a concurrent child version and is likely sensitive to weekly change. In the present study, Cronbach’s α was .94 (parent version) and .89 (child version).

Screen for Child Anxiety-Related Emotional Disorders

The Screen for Child Anxiety-Related Emotional Disorders is a 41-item measure of anxiety symptoms for children aged 8–18 years (Birmaher et al., 1997). Both the child and caregiver versions were used. Respondents are asked to rate symptom frequency on a 3-point Likert scale. A joint rating was created using the either/or rule. Prior research has demonstrated good internal consistency, test–retest reliability, and sensitivity to treatment effects (Birmaher et al., 1997). Here, Cronbach’s α = .94 for the youth ratings and .95 for the parent ratings.

Children’s Depression Inventory

Children’s depressive symptoms were assessed using both the child and parent versions (Kovacs, 1992, 1996). The child version is a 27-item instrument for youth aged 7–17 years and the parent version has 17 items that cover the same symptoms. Both use a 4-point scale to assess symptom frequency. The Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI) has been found to have high internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = .83) and test–retest reliabilities have been good, .74–.77 (Carle, Millsap, & Cole, 2008). A joint rating was created using the either/or rule using the overlapping 17 symptoms on both the parent and child versions. Cronbach’s α was .90 for the youth version, .89 for the parent version.

Rumination

The Rumination questionnaire is a self-report measure that assesses how often individuals think about the traumatic event (Ehlers, Mayou, & Bryant, 1998). Youth rated their tendency to worry on a 7-point Likert scale. They then rated how often they dwell on memories of the event, thought about why it happened, and attempt to push these memories out of their mind on a 5-point Likert scale. This measure was included in light of research suggesting that rumination may be an important predictor of PTSD in youth (Meiser-Stedman et al., 2009). Although this measure has not previously been used with youth, it was used in the absence of established rumination measures for children. For the present study, Cronbach’s α was .72.

Davidson Trauma Scale

The Davidson Trauma Scale (DTS) is a 17-item self-report measure that assesses the DSM-IV PTSD symptoms (Davidson et al., 1999). Caregivers were asked to identify their most distressing traumatic event and then rate each PTSD symptom. Items are rated on a 5-point frequency scale and severity scale. The DTS has good test–retest reliability (r = .86) and internal consistency (r = .99). Cronbach’s α for this study was .94.

Treatment

Participants received Youth PTSD Treatment (YPT), which was created for the RCT (Scheeringa & Weems, 2014). YPT is an extension for older children of Preschool PTSD Treatment (Scheeringa, Amaya-Jackson, & Cohen, 2010) that has shown good efficacy in a RCT (Scheeringa et al., 2011). YPT is a 12-session manualized protocol that includes traditional components of CBT for childhood trauma: psychoeducation, affect identification, relaxation, cognitive coping, trauma narrative processing and graded exposure, and safety plans. Caregivers are involved in every session. Treatment was delivered by two masters-level therapists trained in CBT and supervised by the principal investigator (M.S.) and co-investigator (C.W.). Fidelity to the treatment was monitored by the use of fidelity checklists following each session. Two independent raters viewed 27% of the sessions and found the therapists to have 91% fidelity.

Procedure

The present study used youth who attended five sessions or more of CBT for PTSD treatment as part of an RCT investigating CBT for PTSD and DCS (Scheeringa & Weems, 2014). Participants were not allocated to the DCS condition until after Session 5; therefore, DCS could not have impacted responder status. As reported in main results of this study (Scheeringa & Weems, 2014), DCS was unrelated to any of the outcomes at the posttreatment assessments. By Session 4, youth had participated in the psychoeducation, affect identification, relaxation, and cognitive coping sessions. The CPSS-P and CPSS-C scores that were reported immediately before Session 5 were used to calculate parent-reported or child-reported early treatment response, defined as scores below the clinical cutoff of 11 (Foa et al., 2001). The measures were administered again at posttreatment and at 3-month follow-up. The study was approved by the Tulane University Committee on the Use of Human Subjects.

Data Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS for Windows, Version 19. Two multivariate analyses of variance (MANOVAs; one for parent reports, one for child reports) were used to investigate whether early treatment responders differed from nontreatment responders on any of the hypothesized variables: youth’s pretreatment PTSD, depression, and anxiety symptoms, level of rumination, number of traumas, time between the traumatic event and assessment, and parental PTSD symptoms. Demographic variables were assessed in relation to responder status using either MANOVA or chi-square tests to investigate potential covariates. Maintenance of early treatment response was examined using MANOVA. A priori power analyses using G*Power MANOVA Global Effects indicated that for 56 participants we had power of .75 to detect a medium effect (d = .50) and power of .99 to detect a large effect (d = .80).

Results

Sample Characteristics

To assess the representativeness of the sample, demographic variables (i.e., age, gender, race, ethnicity, and income) and symptom levels (i.e., PTSD, anxiety, depression, rumination, and parental PTSD) were compared between those who were evaluated and consented to participate versus those who declined. No differences were observed on any demographic variable. Those who declined to participate had lower levels of anxiety, t(135) = −2.73, p = .07 (M = 36.33, SD = 17.49 vs. M = 44.65, SD = 15.50) and PTSD symptoms on the DISC, t(138) = −12.84, p < .001 (M = 2.55, SD = 1.61 vs. M = 4.80, SD = .43). No differences were observed between those who attended at least one session compared with those who consented but did not attend any sessions. Lastly, the participants in treatment at Session 5 were compared with those who prematurely terminated treatment by Session 5. Groups differed only with regard to minority status, χ2 (1, 98) = 3.84, p = .05, with members of minority groups being more likely to drop out. Income was trending toward significance, t(96) = −1.87, p = .06, with those who dropped out reporting lower incomes.

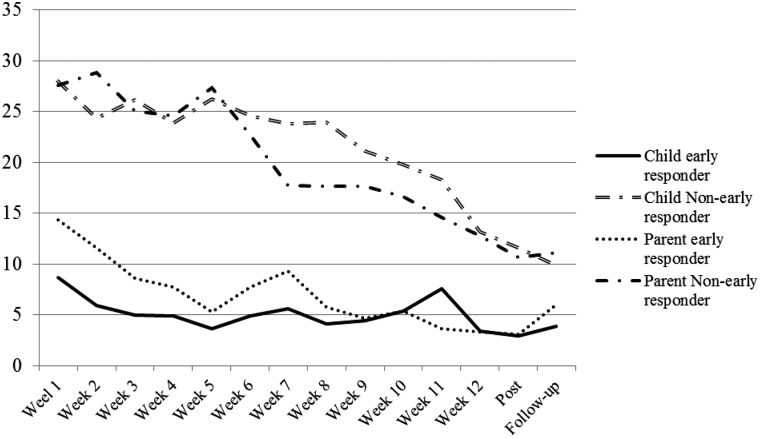

The mean age was 12.59 years (Range 7–18, SD = 3.27); 57.1% were female, 42.9% male. Forty-two percent (42.9%) identified as White, 39.3% Black, 14.3% multiracial, and 3.6% Native American. The majority, 71.4%, identified as non-Hispanic, 28.6% as Hispanic. Mean number of days since the trauma was 715.32 (SD = 767.31), or approximately 24 months. At pretreatment, 86% of participants had PTSD diagnoses, 14% had subthreshold PTSD. Mean number of traumatic events was 2.78 (SD = 1.56). Witnessing domestic violence was most common (42.9%), followed by sexual assault (39.3%), natural disaster (21.4%), physical assault (19.6%), hearing or witnessing someone being hurt or killed (16.1%), accident (12.5%), being threatened with a weapon (10.7%), and seeing a dead body (3.6%). Approximately 11% had CPSS-P scores from 0 to 10, 41.5% from 11 to 20, 28.3% from 21 to 30, and 18.8% ≥31; 28.6% of youth had CPSS-C scores from 0 to 10, 16.1% from 11 to 20, 33.9% from 21 to 30, and 21.4% ≥31 (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

CPSS scores by early responder status.

Immediately before Session 5, 32.1% had CPSS-P scores from 0 to 10, 22.6% from 11to 20, 22.6% from 21 to 30, and 22.6% ≤31. Thus, 32.1% of the sample had CPSS-P scores below the cutoff and were considered parent-reported early responders; 67.9% were classified as nonearly responders. Using the children’s reports, 44.6% had CPSS-C scores from 0 to 10, 21.4% from 11 to 20, 14.3% from 21 to 30, and 19.6% ≤31. Approximately 45% of youth reported symptoms below the cutoff and were classified as early responders, whereas 55.3% were deemed nonearly responders. The majority of parent–child dyads agreed (73.6%).

Factors Related to Parent-Reported Early Treatment Response

Age, income, gender, minority status, and ethnicity were unrelated to responder status (p values >.05). A one-way MANOVA revealed a significant multivariate main effect, Wilks’ λ = .60, F(1, 51) = 3.19, p = .005, d = .52, observed power = .95. Consistent with the hypotheses, significant univariate main effects for early treatment response were obtained for pretreatment PTSD, F(1, 51) = 17.12, p < .001, d = 1.21; depression, F(1, 51) = 21.45, p < .001, d = 1.36; anxiety, F(1, 51) = 10.04, p = .003, d = .93; and number of traumatic events, F(1, 51) = 4.45, p = .04, d = .62 (see Table I). As expected, parent-reported early responders reported lower levels of PTSD, depressive, and anxiety symptoms, and fewer traumatic events than nonearly responders. Parental PTSD symptoms did not differ between groups, F(1, 51) = .38, p = .53, d = .18. Rumination trended toward significance, F(1, 51) = 3.33, p = .07, and demonstrated a medium effect size of d = .53. Time between the trauma and treatment did not reach significance, but we observed a medium effect size (d = .52) and substantial differences in the standard deviations between groups.

Table I.

Characteristics of Early Responders Versus Nonearly Responders

| Parent report |

Child report |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Responder (%) (n = 17) | Nonresponder (%) (n = 36) | Responder (%) (n = 25) | Nonresponder (%) (n = 31) | |||||||

| Male | 52.9 (n = 9) | 36.1 (n = 13) | 40.0 (n = 10) | 45.2 (n = 14) | ||||||

| Female | 47.1 (n = 8) | 63.9 (n = 23) | 60.0 (n = 15) | 54.8 (n = 27) | ||||||

| Nonminority | 58.8 (n = 10) | 36.1 (n = 13) | 72.0 (n = 18) | 19.4 (n = 6) | ||||||

| Minority | 41.2 (n = 7) | 63.9 (n = 23) | 28.0 (n = 7) | 80.6 (n = 25) | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic | 70.6 (n = 12) | 69.4% (n = 25) | 76.0 (n = 19) | 67.7 (n = 21) | ||||||

| Hispanic | 29.4 (n = 5) | 30.6 (n = 11) | 24.0 (n = 6) | 32.3 (n = 10) | ||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | D | M | SD | M | SD | D | |

| Age | 11.73 | 2.96 | 12.61 | 3.23 | 0.27 | 11.65 | 3.19 | 13.35 | 3.17 | 0.53* |

| Income | 4.24 | 3.05 | 4.31 | 3.33 | 0.02 | 4.80 | 3.34 | 3.84 | 3.22 | 0.29 |

| Number of traumas | 2.41 | 0.71 | 3.44 | 1.94 | 0.62* | 2.56 | 1.22 | 3.67 | 1.88 | 0.68* |

| Days since trauma | 470.24 | 532.23 | 868.89 | 850.95 | 0.52 | 778.32 | 771.29 | 664.52 | 773.00 | 0.14 |

| Children’s PTSD | 7.88 | 2.36 | 11.36 | 3.05 | 1.21*** | 12.00 | 2.76 | 8.20 | 2.39 | 1.45** |

| Parental PTSD | 19.76 | 17.65 | 22.89 | 16.83 | 0.18 | 19.76 | 16.88 | 24.71 | 17.66 | 0.16 |

| Anxiety | 35.88 | 13.22 | 49.83 | 15.69 | 0.93** | 38.52 | 14.60 | 50.81 | 9.05 | 0.83** |

| Depression | 22.41 | 8.78 | 34.25 | 8.64 | 1.36*** | 26.56 | 9.95 | 33.58 | 9.05 | 0.74** |

| Rumination | 4.24 | 2.81 | 5.72 | 2.74 | 0.53 | 4.16 | 2.60 | 6.19 | 2.61 | 0.77** |

Note. *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001.

Factors Related to Child-Reported Early Treatment Response

Age differed between groups, F(1, 53) = 3.94, p = .05, d = .53, with early responders tending to be younger than nonresponders. A significant effect for minority status was observed, χ2 (1, 54) = 15.66, p < .001), with minority group members tending to be nonresponders than responders. A one-way MANOVA indicated a significant multivariate main effect, Wilks’ λ = .52, F(1, 53) = 4.65, p < .001, d = .57, observed power = .99. As expected, significant univariate main effects for treatment responders were obtained for pretreatment PTSD, F(1, 53) = 29.34, p < .001, d = 1.45; depression, F(1, 53) = 7.61, p = .009, d = .74; anxiety F(1, 53) = 9.65, p = .003, d = .83; rumination, F(1, 53) = 8.39, p = .005, d = .77; and number of traumatic events, F(1, 53) = 6.52, p = .01, d = .68. Early responders reported lower levels of PTSD, depression, anxiety, rumination, and fewer traumas than nonearly responders. Parental PTSD symptoms and time between the trauma and treatment did not differ between groups (p values > .05).1

Maintenance of Early Treatment Response

There were 44 CPSS-P and 45 completed CPSS-C measures at posttreatment. All parent-reported responders reported symptoms below cutoff, compared with 65.4% of nonresponders. Of child-reported responders, 95.3% reported symptoms below cutoff versus 56.4% of nonresponders. Early responders’ posttreatment PTSD severity was compared with nonearly responders’ severity to determine whether nonearly responders demonstrated equivalent treatment response. Parent-reported early responders had significantly lower CPSS-P scores compared with nonearly responders, t(39) = 2.52, p = .016, d = .91 (M = 3.12, SD = 2.64 vs. M = 10.65, SD = 11.28). Similarly, child-reported responders had significantly lower CPSS-C scores than nonearly responders, t(43) = 3.26, p = .002, d = 1.00 (M = 2.95, SD = 5.75 vs. M = 11.56, SD = 10.60).

At 3-month follow-up, 78.6% of parent-reported responders reported CPSS-P scores below cutoff, indicating that early treatment response was generally maintained. Of the parent-reported nonearly responders, 57.1% achieved responder status at follow-up. Similarly, 86.9% of child-reported responders maintained responder status at follow-up compared with 75% of nonearly responders. Child-reported early responders had significantly lower scores than nonearly responders, t(34) = 2.50, p = .01, d = .81 (M = 3.85, SD = 4.96 vs. M = 9.88, SD = 9.22). The pattern was highly similar for parent-reported early responders CPSS-P scores at follow-up but the difference was not significant from nonearly responders, t(33) = 1.54, p = .13 (M = 6.00, SD = 6.40 vs. M = 11.10, SD = 11.14), despite a medium effect size, d = .56.

Discussion

This study adds to the extant literature in a number of ways. First, the findings offer some preliminary evidence regarding parent- and child-reported early treatment response in youth exposed to trauma. Here, 32% of youth were considered early responders per their parents’ reports and 44.6% were classified as responders by their own assessment. Thus, a sizable portion of youth may be suited for lower “doses” of treatment. Although there have been no prior studies that have specifically examined factors related to early treatment response in traumatized children, our findings intersect with some research using abbreviated protocols. Deblinger et al. (2006) found adequate treatment outcomes using an abbreviated eight-session TF-CBT protocol. Berkowitz et al. also demonstrated that a four-session protocol begun within 30 days of exposure significantly reduced PTSD symptoms in youth (Berkowitz, Stover, & Marans, 2010; see also Kenardy et al., 2008). While these positive responses might be attributed to spontaneous remission in that both the Berkowitz et al. and Kenardy et al. studies intervened very soon after trauma exposure, here the mean duration between the trauma and the assessment was 24 months. Prior research suggests that PTSD is unlikely to remit spontaneously in youth (Scheeringa, Zeanah, Myers, & Putnam, 2005); therefore, it seems unlikely that early responders would have spontaneously recovered.

Second, as early treatment response was operationalized before direct trauma processing, not all children with PTSD may require in-depth trauma processing to achieve good clinical outcomes (Deblinger et al., 2006), which has also been suggested for adults (Resick et al., 2008). While this finding should be replicated with a larger sample, the issue of whether traumatic memory processing is essential to achieve good treatment outcomes requires further examination (see also Carrión, Kletter, Weems, Berry, & Rettger, 2013). Third, as expected, pretreatment levels of symptoms (i.e., PTSD, depression, and anxiety) and number of traumas were related to both parent- and child-reported responder status. Level of rumination was related to child-reported response, but not parent-reported response, perhaps as rumination is not a symptom parents can easily assess. However, based on the observed Cohen’s d of .53, rumination may have also been related to parent-reported treatment response in a larger sample. The findings regarding symptom levels are intuitive, and consistent with prior research demonstrating that children’s pretreatment symptom severity has shown to be inversely related to PTSD treatment response (Nixon et al., 2012). Youth with higher levels of pretreatment symptoms may need a higher “dose” of treatment, such as increased number or longer sessions, or adjunct treatments (i.e., psychopharmacological interventions). It is hoped that these initial findings may be used within the stepped care literature to help guide clinical decision-making regarding who is most appropriate for Step 1 interventions. Future research should examine whether there are differential relationships between specific symptoms and early treatment response.

In contrast to expectations, parental PTSD symptoms were not related to responder status. It is possible that with a larger sample size we may have found an effect, as prior studies have highlighted the importance of parental functioning in children’s symptom presentation (Cohen & Mannarino, 1996, 2000). Yet, the failure to find a group difference is similar to Weems and Scheeringa (2013), who found that maternal symptoms were predictive of relapse but not initial response. It may be that for some parents, their own PTSD symptoms may motivate them to engage in treatment, whereas for others, it may hinder treatment.

Fourth, younger and non-White participants were more likely to be child-reported early responders. It is not clear as to why these variables would only be related to child-reported responder status. As suggested by some of the effect sizes in Table I, additional demographic variables may have reached significance in larger samples. Minority status was also significantly related to dropout, which may indicate that treatment may be less effective for these youth. Number of traumas was also predictive of treatment response, in contrast to previous findings (Deblinger et al., 2006). Length of time between the trauma and treatment was not significantly related to responder status; however, it may have reached significance in a larger sample based on the medium effect size (d = .52) we observed in the parent-reported group as well as the large differences in the SDs of the groups. Future studies with larger samples should examine the role of demographics and characteristics of the trauma in relation to treatment response and prioritize how to maximize treatment effectiveness for diverse populations.

The majority of parent–child dyads (73.6%) demonstrated agreement regarding responder status. This level of parent–child agreement is consistent with other studies finding differences in levels of parent versus child reports of symptoms (i.e., Scheeringa et al., 2006). Future studies should further examine factors relating to differences in parent–child symptom reports as well as the reliability of children’s symptom reports compared with parent’s reports. We opted to use the conjoint rule for symptom reports based on previous findings that the use of this rule resulted in significantly higher scores compared with the scores of either informant alone by almost twofold (Scheeringa et al., 2006). One advantage of the conjoint rule is that if either the child or the parent perceives the child to have the symptom, it is captured. If only one informant was used, the child’s symptoms may be underreported. However, the conjoint rule may lead to overreporting children’s level of symptoms.

Lastly, all parent-reported and all but one child-reported responders remained responders at posttreatment. Early responders also demonstrated lower PTSD symptoms at posttreatment when compared with nonearly responders. Thus, it was not the case that nonearly responders “caught up” to early responders at posttreatment. These treatment gains were largely maintained at follow-up, with 78% of parent- and 85% of child-reported responders retaining their responder status, compared with 57% of parent- and 75% of child-reported nonearly responders. Therefore, the majority of youth had significant treatment gains with the full “dose” of treatment.

Limitations

There are several limitations of the present study. Most notably is the small sample size and lack of control group. The failure to support some of the hypotheses may have been due to insufficient power. Anxiety and depression were also highly correlated (r = .65). In the absence of a control group, the possibility that the early responders would have recovered without treatment cannot be ruled out. It is also possible that the early responders would not have maintained their gains at the 3-month follow-up if they had discontinued the treatment by Session 5. While the sample used in the current study was drawn from the community in New Orleans, a diverse urban city with a complex traumatic history and significant levels of poverty, members of a minority group were more likely to drop out of treatment. Thus, this sample may not be entirely representative of clients presenting to community mental health clinics, and future work should prioritize using community-based samples to explore how transportable these models are to these settings.

Early treatment response was operationalized as PTSD scores below clinical cutoff. There are alternative ways to operationalize early treatment response (i.e., percentage in symptom reduction, reliable change index); however, there is no consensus on a metric. We chose not to use a symptom reduction percentage approach owing to the absence of empirical reasons for using a specific percentage as well as floor effects. We were more interested in an absolute level of severity that would indicate need for further treatment, as some youth may exhibit a significant percentage reduction in symptoms, yet still have symptoms above clinical cutoff and need further treatment. We opted for the cutoff method because it is simple to apply in clinical practice. Still, the associations we found between the pretreatment factors and responder status may be less a function of treatment response per se and more that some “responders” entered treatment with lower symptomatology in the first place. That is, the variables may be more related to baseline symptom severity than they are to the actual response to intervention. However, the pattern found in the supplemental analyses is consistent with interpretations in the main text (i.e., younger age, fewer traumas, lower pretreatment PTSD, anxiety, depression, and rumination had lower initial intercepts but also steeper slopes). Ultimately, our interpretation is that children with clinical levels of PTSD symptoms, but who also have a pattern of lower severity across multiple indices, may be indicative of a shortened course of treatment.

Conclusions

Despite these limitations, this study provides preliminary evidence suggesting the existence of early treatment response in traumatized children and points to the importance of pretreatment levels of PTSD symptoms in predicting this response. It is hoped that further research will be conducted that will identify pretreatment characteristics that can be reliably identified to facilitate clinical decision-making regarding who might be best suited for lower doses of treatment akin to stepped care models.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary data can be found at: http://www.jpepsy.oxfordjournals.org/.

Funding

Financial support for this study was provided by National Institute of Mental Health grant 5RC1MH088969-02 and a 2009 National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression (NARSAD) Independent Investigator Award (M.S.S.).

Conflicts of interest: None declared.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

1 Findings from the MANOVAs were supplemented with multilevel modeling analyses using HLM 7.01 (see Supplementary Material online). These analyses estimated the within-subject change from pretreatment to Session 5 using the variables identified in Table I as potential moderators of the trends on the second level (fixed effects, Level 2). The HLM analyses nested pretreatment to Session 5 change (Level 1 change) in parent and child outcomes as a function of the variables associated with early treatment response. Symptom change was similarly predicted by the variables we identified (Supplementary Table and Figure available upon request). Younger age, fewer traumas, lower pretreatment PTSD, anxiety, depression, and rumination had lower initial intercepts but also steeper slopes, consistent with the main analyses.

References

- Allen B., Gharagozloo L., Johnson J. C. (2012). Clinician knowledge and utilization of empirically-supported treatments for maltreated children. Child Maltreatment, 17, 11–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkowitz S. J., Stover C. S., Marans S. R. (2010). The child and family traumatic stress intervention: Secondary prevention for youth at risk of developing PTSD. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 52, 676–685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birmaher B., Khetarpal S., Brent D., Cully M., Balach L., Kaufman J., Neer S. M. (1997). The screen for child anxiety related emotional disorders (SCARED): Scale construction and psychometric characteristics. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 36, 545–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carle A. C., Millsap R., Cole D. A. (2008). Measurement bias across gender on the Children's Depression Inventory. Educational & Psychological Measurement, 68, 281–303. [Google Scholar]

- Carrión V. G., Kletter H., Weems C. F., Berry R. R., Rettger J. P. (2013). Cue-centered treatment for youth exposed to interpersonal violence: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 26, 654–662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. A., Bukstein O., Walter H., Benson R. S., Chrisman A., Farchione T. R., Hamilton J., Keable H., Kinlan J., Schoettle U., Siegel M., Stock S., Medicus J., AACAP Work Group On Quality Issues (2010). Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 49, 414–430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. A., Mannarino A. P. (1996). A treatment outcome study for sexually abused preschool children: Initial findings. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 35, 1402–1410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. A., Mannarino A. P. (2000). Predictors of treatment outcome in sexually abused children. Child Abuse and Neglect, 24, 983–994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. A., Mannarino A. P., Deblinger E. (2006). Treating trauma and traumatic grief in children and adolescents. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Comer J. S., Barlow D. H. (2014). The occasional case against broad dissemination and implementation: Retaining a role for specialty care in the delivery of psychological treatments. American Psychologist, 69, 1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson J. R., Book S. W., Colket J. T., Tupler L. A., Roth S., David D., Hertzberg M., Mellman T., Beckham J. C., Smith R. D., Davison R. M., Katz R., Feldman M. E. (1997). Assessment of a new self-rating scale for post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychological Medicine, 27, 153–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deblinger E., Mannarino A. P., Cohen J. A., Runyon M. K., Steer R. A. (2011). Trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy for children: Impact of the trauma narrative and treatment length. Depression and Anxiety, 28, 67–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deblinger E., Mannarino A. P., Cohen J. A., Steer R. A. (2006). A follow-up study of a multisite, randomized, controlled trial for children with sexual abuse-related PTSD symptoms. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 45, 1474–1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers A., Mayou R. A., Bryant B. (1998). Psychological predictors of chronic posttraumatic stress disorder after motor vehicle accidents. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 107, 508–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felitti M. D., Vincent J., Anda M. D., Robert F., Nordenberg M. D., Williamson M. S., Spitz A. M., Edwards V., Koss M. P., James S. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14, 245–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa E. B., Johnson K. M., Feeny N. C., Treadwell K. R. (2001). The Child PTSD Symptom Scale: A preliminary examination of its psychometric properties. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 30, 376–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galovski T. E., Blain L. M., Mott J. M., Elwood L., Houle T. (2012). Manualized therapy for PTSD: Flexing the structure of cognitive processing therapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 80, 968–981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenardy J., Thompson K., Le Brocque R., Olsson K. (2008). Information-provision intervention for children and their parents following pediatric accidental injury. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 17, 316–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M. (1992). Children's Depression Inventory Manual. North Tonawanda, NY: Multi-Health Systems. [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M. (1996). Children’s Depression Inventory: Parent Version (CDI:P). North Tonawanda, NY: Multi-Health Systems. [Google Scholar]

- Meiser-Stedman R., Smith P., Bryant R., Salmon K., Yule W., Dalgleish T., Nixon R. D. (2009). Development and validation of the Child Post-Traumatic Cognitions Inventory (CPTCI). Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 50, 432–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nixon R. D. V., Sterk J., Pearce A. (2012). A randomized trial of cognitive behavior therapy and cognitive therapy for children with posttraumatic stress disorder following single-incident trauma. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 40, 327–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olfson M., Mojtabai R., Sampson N. A., Hwang I., Druss B., Wang P. S., Wells K. B., Pincus H. A., Kessler R. C. (2009). Dropout from outpatient mental health care in the United States. Psychiatric Services, 60, 898–907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resick P. A., Uhlmansiek M. O. B., Clum G. A., Galovski T. E., Scher C. D., Young-Xu Y. (2008). A randomized clinical trial to dismantle components of cognitive processing therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder in female victims of interpersonal violence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76, 243–258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizvi S. L., Vogt D. S., Resick P. A. (2009). Cognitive and affective predictors of treatment outcome in cognitive processing therapy and prolonged exposure for posttraumatic stress disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 47, 737–743. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salloum A., Scheeringa M. S., Cohen J. A., Storch E. A. (2014). Development of stepped care trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy for young children. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 21, 97–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salloum A., Robst J., Scheeringa M. S., Cohen J. A., Wang W., Murphy T. K., Tolin D. F., Storch E. A. (2014). Step one within stepped care trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy for young children: A pilot study. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 45, 65–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheeringa, M. S., Amaya-Jackson, L., & Cohen, J. (2010, October). Preschool PTSD treatment (Version 1.7). New Orleans, LA: Tulane Institute of Infant and Early Childhood Mental Health. Retrieved from http://www.infantinstitute.com/MikeSPDF/PPTversion7.pdf.

- Scheeringa M. S., Weems C. F. (2014). Randomized placebo-controlled D-Cycloserine with cognitive behavior therapy for pediatric posttraumatic stress. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 24, 69–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheeringa M. S., Weems C. F., Cohen J. A., Amaya-Jackson L., Guthrie D. (2011). Trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder in three-through six year-old children: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 52, 853–860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheeringa M. S., Wright M., Hunt J., Zeanah C. (2006). Factors affecting the diagnosis and prediction of PTSD symptomatology in children and adolescents. American Journal of Psychiatry, 163, 644–651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheeringa M. S., Zeanah C. H., Myers L., Putnam F. W. (2005). Predictive validity in a prospective follow-up of PTSD in preschool children. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 44, 899–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer D., Fisher P., Lucas C. P., Dulcan M. K., Schwab-Stone M. E. (2000). NIMH diagnostic interview schedule for children version IV (NIMH DISC-IV): Description, differences from previous versions, and reliability of some common diagnoses. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 39, 28–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman W. K., Ortiz C. D., Viswesvaran C., Burns B. J., Kolko D. J., Putnam F. W., Amaya-Jackson L. (2008). Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for children and adolescents exposed to traumatic events. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 37, 156–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein N. R., Dickstein B. D., Schuster J., Litz B. T., Resick P. A. (2012). Trajectories of response to treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder. Behavior Therapy, 43, 790–800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weems C. F., Scheeringa M. S. (2013). Maternal depression and treatment gains following a cognitive behavioral intervention for posttraumatic stress in preschool children. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 27, 140–146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.