Abstract

Objective:

To report the personal experiences of patients undergoing awake craniotomy for brain tumor resection.

Methods:

We carried out a qualitative descriptive survey of patients’ experiences with awake craniotomies for brain tumor resection. The survey was conducted through a standard questionnaire form after the patient was discharged from the hospital.

Results:

Of the 9 patients who met the inclusion criteria and underwent awake craniotomy, 3 of those patients reported no recollection of the operation. Five patients had auditory recollections from the operation. Two-thirds (6/9) reported that they did not perceive pain. Five patients remembered the head clamp fixation, and 2 of those patients classified the pain from the clamp as moderate. None of the patients reported that the surgery was more difficult than anticipated.

Conclusion:

Awake craniotomy for surgical resection of brain tumors was well tolerated by patients. Most patients reported that they do not recall feeling pain during the operation. However, we feel that further work and exploration are needed in order to achieve better control of pain and discomfort during these types of operations.

Sixty years ago, Penfield and Pasquet1 performed awake craniotomies in epilepsy patients and they published their landmark reports on the surgical and anesthetic aspects of surgery after administration of local and intermittent sedation and analgesia.1,2 The main advantage of performing an awake craniotomy, compared to a craniotomy under complete sedation, is the ongoing ability to evaluate critical anatomical brain structures and functional integrity, which enables neurosurgeons to avoid symptomatic injuries to critical areas of the brain. The awake craniotomy has also proven to be extremely important in neuro-oncological procedures, as it allows the surgeon to have ongoing evaluation of functional areas while resecting the tumor. In selective cases, tissue resection requires mapping of eloquent cortical tissue located in close proximity to the resection target.3,4 It has been proposed that patients with good preoperative functional status, undergoing uncomplicated tumor resection with this technique, have less iatrogenic deficits and shorter hospital stays compared to traditional techniques.5,6 Surgical resection of brain tumors under conscious sedation may increase the extent of resection while minimizing perioperative deficits. Many patients accept this technique, but understandably it can cause anxiety for some patients. A major concern for these patients is the potential experience of discomfort and pain during the procedure.6 Patients’ perspectives and personal experiences, while undergoing awake craniotomy, are rarely discussed in the literature. Here, we report our patients’ perspectives and experiences, captured after undergoing awake craniotomy for tumor resection.

Methods

We performed a qualitative descriptive survey of patients undergoing awake craniotomies for brain tumor resection. Ethical approval was obtained through the institute director of professional services with advisement of the research ethical board. The same surgeon between September 2007 and May 2009 at the Montreal Neurological Institute, Montreal, performed a total of 12 awake craniotomies for brain tumor resection. All patients were females. We included patients who were able to recall the procedure, the perioperative period, and communicate their concerns with no speech impairment. Epilepsy cases were not included in this study. Three patients were excluded from the study because of either dysphasia or impaired memory. An open-ended survey questionnaire was conducted after discharge from the hospital (Figure 1). A physician who was part of the surgical team conducted the survey via telephone. Prior to the operation, in the clinic, all patients had a detailed discussion with their physician regarding the routine that occurs before, during, and after surgery. The discussion included the use of oral and intravenous medications, scalp injections, head fixation, surgical positioning, surgical duration, and the expected discomfort and pain that would occur during surgery. The patients were educated on their role during surgery, and the ongoing testing of neurological function during the cortical mapping and surgical resection.

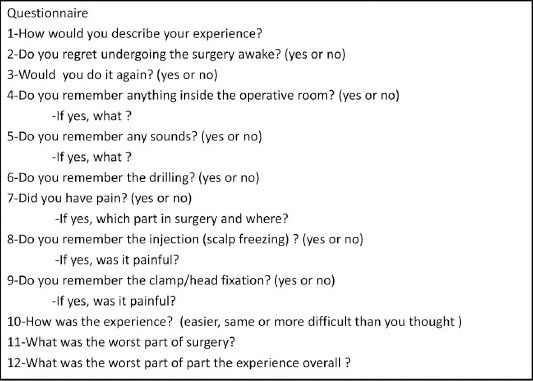

Figure 1.

Standardized questionnaire form used for the survey on a patient’s perspective of awake craniotomy.

The evaluation by the anesthesiologist was performed in the preoperative evaluation area. In 7 craniotomies, propofol was titrated between 35 to 100 microgram/kg/min during the maintenance phase of conscious sedation. While in the remaining 2 surgeries, intravenous opioid anesthetic was used (Sufentanil in one, and Remifentanil in the other). Infusion rates in all cases were calculated and titrated by the anesthetist according to the stage of the surgery and the need to examine the patient. In addition, intravenous Fentanyl (25-50 microgram) and intravenous morphine (2 mg) injections were used intermittently during painful surgical steps, mainly head clamp fixation, scalp injections, skin incision, and skin closure.

We started with injection of the scalp using 0.5% Marcaine with epinephrine in 3 areas; the supraorbital, preauricular, and postauricular areas bilaterally (Figure 2). Then, we proceeded with final positioning using soft pillows under the shoulder and hip. The planned sites for the clamp fixation were injected with 0.5% Marcaine with epinephrine. The Mayfield clamp was applied gradually until final pressure was achieved. After navigation registration and skin incision planning were completed, we injected the planned incision area. The incision was made and the craniotomy was performed using a high-speed drill and craniotome. Brain mapping was performed utilizing direct cortical stimulation. The surgical team tested the patient continuously during the required stages of craniotomy including cortical mapping and tumor resection. Pain medications and anesthesia infusions were titrated according to the patient’s report of pain and the desired level of consciousness. An oxygen nasal cannula was used during the procedure.

Figure 2.

Awake craniotomy A) diagram showing the areas injected with 0.5% marcaine with epinephrine before the skin incision (grey). The clamp fixation points are injected just prior to the head fixation. The sensory nerves and its dermatomal distribution are shown in the figure. B) Intraoperative setting for an awake craniotomy procedure.

Results

Nine awake craniotomies in 8 patients (one patient underwent a second awake craniotomy resection) were included in this study. Three patients were excluded, 2 had impaired memory, and one had severe dysphasia. The age ranged from 28-82 years. All patients were females. Seven had primary brain tumors, and 2 had metastatic disease (Figure 3). The median time between the surgery and the interview was 2 months.

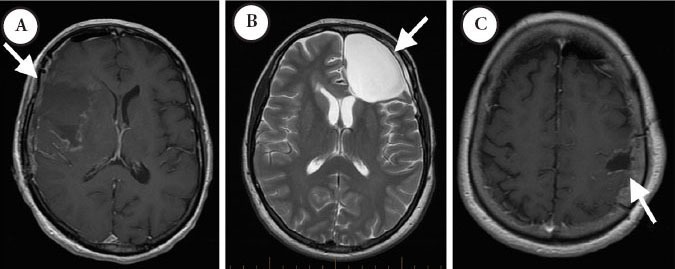

Figure 3.

Preoperative evaluation MRI A) Preoperative T1 MRI with gadolinium of a 65 year-old female who presented with left side hemiparesis (patient 9). B) Preoperative T2 MRI of a 28 year-old female who presented with dysphasia (patient 4). C) Preoperative T1 MRI with gadolinium for an 82 year-old female who presented with mild dysphasia and right upper extremity weakness (patient 5).

One patient had worsening speech during the surgical resection, which improved to her preoperative baseline in follow up (patient number 5). Another patient experienced a permanent sensory impairment as a result of the surgical resection of her right-sided parietal tumor (patient number 3). No other major sequelae were reported in any of the patients in long-term follow up (Figure 4). All patients expressed that they did not regret undergoing the surgery using the awake craniotomy technique. They reported that they would undergo the awake technique again if another craniotomy were necessary in their future. When asked if they had any recollection of their encounter inside the operating room, 3 out of 9 patients reported that they did not have any recollection of the operative act or events that occurred in the operating room. The majority (5/9) of what patients remembered were auditory memories. Four patients remembered the drilling when asked, and only one volunteered that he remembered the drilling, prior to being asked. One patient remembered their interaction with the anesthetist during the induction stage as they described remembering talking to the anesthetist. Six patients answered no when they were asked if they had pain. Two experienced tooth pain, and one mentioned that the clamp was painful (patient number 6). Five patients answered yes when asked directly if they remember the head clamp fixation, 2 classified the pain from the clamp as moderate. Patient number 6 had no opioid injection during the head clamp fixation.

Figure 4.

Postoperative evaluation of A) patient 9, B) patient 4, and C) patient 5 consecutively.

When patients were asked about their experience and expectations, none of them reported that the surgery was more difficult than anticipated. Five out of the 9 patients answered that it was easier than they thought it would be. The patients’ descriptions of the overall experience are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patients overall experience and impression of awake craniotomy.

| Patient No. | How was the experience? | What was the worst part in the surgery? | What was the worst part the experience overall? |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Easier | My mouth very dry and I was thirsty | The intravenous lines insertion, hard waiting for the surgery |

| 2 | Easier | Being more awake | Being more awake |

| 3 | Easier | Lying on my side | Lying on my side |

| 4 | Same | Nothing | Nothing |

| 5 | Same | In the end because I lost speech, the beginning was also hard | The needle (local injection) |

| 6 | Same | Darkness during the surgery | Darkness during the surgery |

| 7 | Same | Feeling cold | The scars after the surgery |

| 8 | Easier | Pain in teeth | Nursing issues before the surgery |

| 9 | Easier | Scared to move during the surgery | Not improving after the surgery |

Discussion

Awake craniotomy is a surgical technique that enables surgeons to avoid damaging critical regions of the brain during surgery. Awake procedures can be helpful in cases where cortical mapping or continuous monitoring of neurological functions are expected to improves outcomes. Conscious sedation procedures are becoming more popular, specifically in cases where a tumor is located in close proximity to critical structures such as motor and speech cortex.1,3,4 This approach gives the surgeon the ability to actively monitor, and thus minimize neurological impairments during the operation.

Many techniques of sedation, analgesia, and anesthesia have been described, including the 2 well described approaches of conscious sedation technique and asleep–awake–asleep technique.3,7 At our institution we used the continuous conscious sedation technique for awake craniotomies. Patients were well educated regarding the procedure and all the steps to facilitate intraoperative testing in order to decrease anxiety. It has been proposed by Khu et al,6 that patient’s knowledge and understanding of the logic behind awake craniotomy reduces disbelief, anxiety and establishes trust.

One of the components of a successful technique is appropriate patient selection. Although the literature lacks validated criteria to address patient factors that may help the selection process, it has been mentioned anecdotally that lack of patient maturity, hypertension, and alcohol abuse are risk factors for sedation failure.8 In a recent phenomenological study with 21 participant by Palese et al,9 they reported the procedure as an anxiety-provoking experience. Our cohort of patients reported less anxiety and a tolerable experience, which was maintained throughout the surgery and after the recovery period. We feel that this was in part due to the detailed explanation regarding the routine that occurs before, during, and after the surgery, which was given to the patients preoperatively. Also, it is possible that the lack of recall of the intraoperative events contributed to this outcome as well.

In our cohort, 3 out of 9 patients (33%) reported that they had no recollection of operative act. In a study by Danks et al10 where they studied 21 patients who underwent awake craniotomies for tumor resection. In 16 of 21 patients they used Midazolam with fentanyl and sufentanil for sedation, and in 5 of 21 they added propofol to the anesthetic regimen. When looking at recall they found that the incidence of nearly complete recall of the procedure was 40% (2 of 5 patients) in the propofol group, as compared to 13% (2 of 16 patients) in the sufentanil group. In conclusion, Danks et al10 reported that at one-month, all patients were entirely comfortable with the experience. Additionally, we found that most of the patient recall of intraoperative memories were auditory, which is in keeping with previously reported results by Palese et al,9 Khu et al,6 and Manchella et al.11

In our series we found that 5 out of 9 patients remembered having pain from the clamp fixation, although none of the patients reported it as severe pain. In 3 out of 5, the pain was minimal, while the other 2 reported it as moderate. In a prospective qualitative study conducted by Khu et al6 with 27 participants they report that the most painful part of the procedure involved placement of the cranial fixation device and its removal. Moreover, in a study published by Whittle et al12 where 15 patients completed a postoperative questionnaire regarding their operative experience, it was found that the most frequent source of discomfort was pain from the cranial fixation device, inadequate local anesthesia, and pain during positioning on the operating table. We found that dermatomal block using local injections of 0.5% Marcaine with epinephrine at the supraorbital, preauricular, and postauricular areas were sufficient. Adding injections at the head fixation clamp sites helped to reduce the pressure sensation induced by the clamp. Two patients had opioid infusions for sedation rather than propofol, and both recalled more of the event, but had less pain as compared with the rest of the cohort.

From the patient’s perspective of the awake craniotomy, 5 out of the 9 patients believed that their experience was easier than expected. Patient discomfort during the surgery included mouth dryness, feeling uncomfortable in the lateral decubitus position, and feeling cold. Patient communication and expression of their discomfort to the surgeon is one of the components that we believe could help in creating a more tolerable experience for the patient, as it will help in alleviating the source of discomfort, if feasible. Trust and communication between the surgeon, surgery team, and the patient play a major role in making the experience more tolerable. One of the responses provided, when asked about the overall experience, was “Not bad because the surgeon explained everything, I felt 2 hours only”

Study limitations

Results of such descriptive study should be interpreted with caution, as patients’ recall of events are the main source of data, which may introduce recall bias, especially with the wide range of duration between the surgery and the survey. Furthermore, it is difficult to generalize the result of the study given the small sample size, and that the study population was all female.

In conclusion, awake craniotomies for surgical resection of brain tumors have proven to be a well-tolerated procedure by the patients. In our descriptive study, we gave an account of the patient experience during the procedure, yet we feel that this area needs to be further explored so that considerations can be made in order to achieve better control of pain and discomfort perceived by patients undergoing awake craniotomy for tumor resection.

Footnotes

Disclosure.

References

- 1.Penfield W, Pasquet A. Combined regional and general anesthesia for craniotomy and cortical exploration. Part I. Neurosurgical considerations. Int Anesthesiol Clin. 1986;24:1–20. doi: 10.1097/00004311-198602430-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bulsara KR, Johnson J, Villavicencio AT. Improvements in brain tumor surgery: the modern history of awake craniotomies. Neurosurg Focus. 2005;18:e5. doi: 10.3171/foc.2005.18.4.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Costello TG, Cormack JR. Anaesthesia for awake craniotomy: a modern approach. J Clin Neurosci. 2004;11:16–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2003.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meyer FB, Bates LM, Goerss SJ, Friedman JA, Windschitl WL, Duffy JR, et al. Awake craniotomy for aggressive resection of primary gliomas located in eloquent brain. Mayo Clin Proc. 2001;76:677–687. doi: 10.4065/76.7.677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blanshard HJ, Chung F, Manninen PH, Taylor MD, Bernstein M. Awake craniotomy for removal of intracranial tumor: considerations for early discharge. Anesth Analg. 2001;92:89–94. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200101000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khu KJ, Doglietto F, Radovanovic I, Taleb F, Mendelsohn D, Zadeh G, et al. Patients’ perceptions of awake and outpatient craniotomy for brain tumor: a qualitative study. J Neurosurg. 2010;112:1056–1060. doi: 10.3171/2009.6.JNS09716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wahab SS, Grundy PL, Weidmann C. Patient experience and satisfaction with awake craniotomy for brain tumours. Br J Neurosurg. 2011;25:606–613. doi: 10.3109/02688697.2011.568642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Senel FC, Buchanan JM, Jr, Senel AC, Obeid G. Evaluation of sedation failure in the outpatient oral and maxillofacial surgery clinic. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;65:645–650. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2006.06.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Palese A, Skrap M, Fachin M, Visioli S, Zannini L. The experience of patients undergoing awake craniotomy: in the patients’ own words. A qualitative study. Cancer Nurs. 2008;31:166–172. doi: 10.1097/01.NCC.0000305699.97625.dc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Danks RA, Rogers M, Aglio LS, Gugino LD, Black PM. Patient tolerance of craniotomy performed with the patient under local anesthesia and monitored conscious sedation. Neurosurgery. 1998;42:28–34. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199801000-00006. discussion 34-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Manchella S, Khurana VG, Duke D, Brussel T, French J, Zuccherelli L. The experience of patients undergoing awake craniotomy for intracranial masses: expectations, recall, satisfaction and functional outcome. Br J Neurosurg. 2011;25:391–400. doi: 10.3109/02688697.2011.568640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Whittle IR, Midgley S, Georges H, Pringle AM, Taylor R. Patient perceptions of “awake” brain tumour surgery. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2005;147:275–277. doi: 10.1007/s00701-004-0445-7. discussion 277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]