Abstract

Policy initiatives increasingly seek greater use of home- and community-based services for older persons and those with chronic care needs, yet large gaps persist in our knowledge of home care, an indispensable component of long-term services and supports. Unrecognized data gaps, including the scope of home care provided by private hire and nonmedical providers, can distort knowledge and poorly inform long-term services and supports policy. The purpose of this article is to examine these gaps by describing the universe of formal home care services and provider types in relationship to major national sources. Findings reveal four distinct home care sectors and that the majority of formal home care is provided in the sectors that are understudied. We discuss the policy implications of data gaps and conclude with recommendations on where to expand and refine home care research.

Keywords: home care, home health care, home- and community-based services (HCBS), aging and disability services, personal care aides

A policeman saw a man on his hands and knees “groping about” around midnight and asked what he was doing: “I lost a $2 bill down on Atlantic Avenue,” said the man. “You lost a $2 bill on Atlantic Avenue? Then why are you hunting around here in Copley Square?” asked the officer. “Because,” said the man, “the light’s better up here.”

The “Streetlight Effect” is a well-known parable illustrating observational bias that occurs by focusing on something where it is easiest to see (Freeman, 2010). In this article, we argue that gaps in data available to identify and describe some home care services in the United States reflect a Streetlight Effect. Because little is known about several sectors of home care (Kane, 2012), our understanding of the overall costs and characteristics is distorted at the same time that current policy initiatives seek greater use of these home- and community-based services (HCBS).

New Contribution

This article provides an overview of available data in comparison to the universe of formal home care services. We estimate the size of the formal home care industry and present four primary sectors of home care and five core analytical domains that differentiate services. By reviewing national studies in light of the full range of services, we identify providers that are understudied and measure the information gaps. We highlight discussions that have relied on the extant data and discuss the long-term services and supports (LTSS) policy and research implications of the data gaps. We conclude with recommendations to reduce the Streetlight Effect in home care research.

Definitions and Methods

Home care is often used as an umbrella term to refer to a variety of services provided to people with disabilities living in the community. We define home care broadly as the range of health and supportive services provided at home. Although it is important to recognize that informal unpaid caregivers, often family members, and volunteers provide substantial support—valued at $450 billion dollars in 2009 (Feinberg, Reinhard, Houser, & Choula, 2011)—our focus is on home care that is formal and paid. This definition includes friends and family members who are paid through the formal LTSS system (e.g., Medicaid programs) or are paid out-of-pocket by the recipient using personal funds or other resources such as monies from Veterans Administration (VA) benefits.

Home care services range from medical (e.g., physical therapy) to nonmedical/supportive (e.g., assistance with dressing). They can be hands-on (e.g., wound care) or not (e.g., companionship), and short term or long term depending on needs and payer source. Terminology for the service recipient varies: home health agencies use “patient”; home care aide agencies, “client”; and Medicaid programs, “consumer.” We use “recipient” to apply across all types of home care.

State variations in licensing and practice definitions make industry analysis challenging. To determine the size of the home care industry—number of workers and establishments—we used employment summary files and online query tools from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) Employment Projections (EP) and Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages (QCEW) programs. Our data derive from the Occupational Employment Statistics annual survey, the monthly Current Employment Statistics survey, and the Current Population Survey and offer what we believe are the best available estimates on formal home care in the United States.

The BLS categorizes workers using the Standard Occupational Classification (SOC) system. We defined the home care workforce to include home health aides (SOC 31-1011), personal care aides (SOC 39-9021), and nursing assistants (SOC 31-1014). These occupations compromise the majority of home care workers according to the BLS (BLS, 2012).

To address the challenge of standardizing how agencies are counted, number of businesses, locations, or licenses, we used “establishments or agencies” rather than organizations/companies. “Establishments” is a unit of analysis from the BLS that captures single business locations or branches. One organization may operate multiple branches, or establishments. BLS classifies establishments into industries using the North American Industry Classification System (NAICS). We defined the industries engaging in home care as Home Health Care Services (NAICS 621610), Services for the Elderly and Persons with Disabilities (NAICS 624120), Private Households (NAICS 814000), Employment Services that refer or employ temporary workers (NAICS 561300), Self-Employed Workers (TE1110), and State and Local Governments (NAICS999200/999300).

To identify data gaps, we reviewed major national studies including the National Health Expenditure Accounts (NHEA), National Long-Term Care Survey, National Home and Hospice Care Survey (NHHCS), Health and Retirement Study (HRS), and National Study of Long-Term Care Providers (NSLTCP). We also reviewed studies by nongovernment organizations including LeadingAge, Home Care Pulse, and the Paraprofessional Health Institute (PHI).

The Analytical Dimensions of Home Care

The Varying Goals of Home Care

Home care is provided to meet goals from rehabilitative and curative to custodial and supportive. Kane (1999) described these as therapeutic versus compensatory goals and noted that they result in different types of agencies, which operate in separate practice realms. Restorative home care is an extension of medical services delivered in the home setting, while supportive care is ongoing and designed to assist individuals with disabilities to live as independently as possible. This distinction is rooted in the Independent Living movement where the publically funded attendant program was intentionally housed within social service departments in part to avoid “medicalization” and the assumption that recipients are “patients,” sick, and requiring curative treatment (Seyden & Robert, 2006). The consumer direction movement in home care relies on the premise that long-term care is supportive and largely nonmedical (Benjamin & Matthias, 2001; Stone, 2000).

Although the restorative versus supportive home care distinction has been recognized (Kane, 1999; Notarstefano, 2010; Seavey & Marquand, 2011), the idea that medically oriented home health care is synonymous with supportive home care persists. The BLS, for example, only partially differentiates restorative and supportive home care because of limitations in the NAICS. As shown in Table 1, NAICS 621610, Home Health Care Services, includes primarily medically oriented home health care with some supportive home care. NAICS 624120, Services for the Elderly and Persons with Disabilities, also includes supportive home care, along with services provided outside the home in communities. Despite overlap in categorization, these codes are used by BLS researchers and others to track industry characteristics.

Table 1.

Major U.S. Home Care Industries Defined by the NAICS and the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

| NAICS 621610—Home Health Care Services | NAICS 624120—Services for the Elderly and Persons With Disabilities |

|---|---|

| Primarily engaged in providing skilled nursing services in the home to include | Primarily engaged in providing services to improve the quality of life for older persons or persons with disabilities to include |

| Skilled nursing services | Nonresidential social assistance |

| Physical therapy | Day care |

| Occupational therapy | Nonmedical home carea |

| Vocational therapy | Homemaker servicesa |

| Counseling | Social activities |

| Medications | Group support |

| Medical social services | Companionshipa |

| Dietary and nutrition services | |

| Audiology | |

| Speech therapy | |

| Intravenous therapy | |

| Medical equipment and supplies | |

| Personal care servicesa | |

| Homemaker and companion servicesa |

Note. NAICS = North American Industry Classification System.

These represent overlapping labor activities between major home care sectors.

Source. U.S. Census Bureau (2012).

Licensure

Agencies vary by licensure regulations within and across states. Certification or licensure is required for agencies to receive Medicare reimbursement but not to receive Medicaid. As shown in Table 2, supportive nonmedical home care offered by home care aide agencies was not licensed in 21 states in 2014 (DecisionHealth, 2014), including California (with 4.2 million persons aged 65+), Michigan (1.36 million persons aged 65+), and Ohio (1.62 million persons 65+; U.S. Census Bureau, 2010).

Table 2.

States Not Requiring Licensure for Nonmedical Home Care in 2014.

| Alabama |

| Arizona |

| Arkansas |

| California |

| Hawaii |

| Idaho |

| Iowa |

| Kansas |

| Kentucky |

| Michigan |

| Mississippi |

| Missouri |

| Montana |

| New Mexico |

| North Dakota |

| Ohio |

| South Dakota |

| Vermont |

| West Virginia |

| Wisconsin |

| Wyoming |

Source. DecisionHealth (2014).

Among states with licensing, wide variation exists in what is required and allowed to be provided in the home, by whom, and with what level and type of oversight (e.g., whether a doctor’s order is needed to begin service). To our knowledge, no studies have compared these issues by state, region, or agency type.

Payer Sources

Payer sources include Medicare, Medicaid, other government sources such as caregiver support programs and veteran assistance, other insurances such as long-term care insurance or workers compensation, and out-of-pocket private pay. Home care regulations, referral sources, billing, staffing, and agency culture are all sensitive to and reflective of payer sources with agency providers often specializing and organizing their operations around them (Pratt, 2010). Medicare, for example, covers only medically oriented (skilled) intermittent care for a limited period of time. This requires different staffing than home care aide services that are often ongoing, supportive (non-medical), and paid with out-of-pocket funds (Home Care Pulse, 2013) or Medicaid.

Agency Workers Versus Independent Workers

Persons seeking home care locate workers through two portals: agencies or independent workers. Benefits and limitations of each include issues of choice and control, satisfaction with care, safety, financial strain, workplace protections, and ease of administering services (Benjamin, Matthias, & Franke, 2000; Smith, 2007a; Stone, 2000). Independent workers are often associated with the consumer-directed model of care in government-funded programs (Smith, 2007b; Stone, 2000), but they also include private hires by private pay consumers (U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2010).

Distinctions in the Employment Relationship

A last domain useful for understanding the home care industry is the legal nature of the worker’s employment status: Is the worker self-employed or an employee, and if the worker is an employee, who is the employer (the agency, the care recipient, or another entity)? Generally there are “employer model” agencies and “independent contractor model” agencies (Benjamin et al., 2000). IRS regulations stipulate the conditions under which workers are self-employed independent contractors. These distinctions are important because employers are legally mandated to provide worker protections, withhold income taxes, pay half the worker’s Social Security and Medicare taxes (FICA taxes), and also pay for unemployment, health (if they have more than 50 employees), and worker compensation insurance. Employers are also subject to regulations and liabilities pertaining to employee safety, so workers cost more to the agency and thus to the service recipient.

Independent contractors (sometimes called self-employed workers) are responsible for their own FICA taxes, worker compensation, and health insurance, and have no unemployment insurance coverage. They are not required to adhere to the same level of regulation and oversight in their care practices compared with agencies.

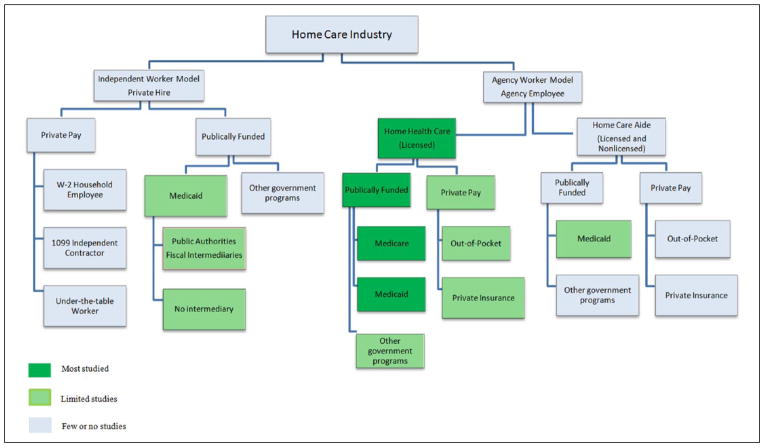

Typology of Home Care Sectors

There are four distinct workplace sectors within the universe of formal home care: (1) home health care agencies, (2) home care aide agencies/personal care aide agencies, (3) the private hire sector, and (4) government organizations. Figure 1, adapted from Seavey and Marquand (2011), maps the industry conceptually and is presented as an aid for analysis and discussion. The figure is shaded to highlight sectors where more data are available.

Figure 1.

Home Care Sectors and Available Data.

Sector 1: Home Health Care Agencies

Home health care agencies are licensed and/or certified to provide skilled, medically oriented services to recipients in their homes. They may also provide supportive services in accordance with a recipient’s plan of skilled care. According to the BLS, in 2013 there were 30,715 establishments within NAICS 621610, Home Health Care Services, including hospice agencies (BLS, 2013a). Isolating the number of medically oriented, skilled home health care establishments in this category is not possible because some nonmedical personal care and homemaker establishments are also placed in this NAICS category.

The National Center for Health Statistics counted 12,200 regulated home health agencies in 2013 (Harris-Kojetin, Sengupta, Park-Lee, & Valverde, 2013); the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) counted 11,633 Medicare certified agencies in 2011 (CMS, 2011). We were unable to find statistics on the number of home health establishments that are Medicaid certified and/or receive Medicaid payments. This information is decentralized within individual states and is unavailable. Agencies that do not participate in Medicare or Medicaid derive their revenue from out-of-pocket payments, insurances (e.g., disability or worker compensation), or funds from court settlements.

Sector 2: Home Care Aide Agencies (Personal Care Aide Agencies)

Home care aide agencies provide supportive nonmedical services such as help with dressing or meal preparation. Attempts to estimate the number of home care aide establishments and workforce size in this sector are hobbled by classification problems. For example, LeadingAge reported approximately 11,000 nonmedical home care agencies in 2010 (Notarstefano, 2010), while BLS reported 576,117 establishments in 2013 with more than 1,375,000 workers in NAICS 624120, Services for Elderly and Persons with Disabilities, a category that groups nonmedical “personal care aides” with nonresidential day care and other social services provided outside the home (BLS, 2013b). The National Association for Home Care and Hospice does not estimate the size or total spending in the home care aide sector because of difficulties in identifying providers across states with varying licensing requirements (National Association for Home Care and Hospice, 2010).

The Private Duty Home Care Benchmarking Study reported 15,100 to 17,700 businesses in 2011; about half were licensed (Home Care Pulse, 2011). Twenty-five percent of businesses reported having more than one location or establishment in 2013, with 12.5% reporting three or more (Home Care Pulse, 2014). Because these studies use businesses, rather than establishments, as their unit of analysis, their estimates underreport industry size. Payment sources for these agencies in 2013 were 82% from private pay (including 70% out-of-pocket payments) and 17% from publically funded programs such as Medicaid or Veteran Assistance (Home Care Pulse, 2014).

The California Association for Health Services at Home, using online and print Yellow Pages, identified 1,200 nonlicensed home care aide agencies and 1,163 licensed home health care agencies in 2008 and concluded: “Home care aide organizations comprise the largest single type of home care provider in California and 40 percent of the entire industry” (California Association for Health Services at Home, 2009, p. 4). In contrast, home health care agencies comprised 38% of the industry.

Sector 3: The Private-Hire Sector

The private-hire sector includes home care workers hired with private funds by individual households as either household employees or independent contractors; black market workers paid “under the table”; and “independent providers” (IPs) paid by government benefit programs, primarily Medicaid.

Private households find home care workers through word of mouth or by using a referral agency (sometimes called a registry or placement agency). Referral agencies do not employ their workers. They offer screened caregivers for consumers to hire; the workers become the employee of the care recipient or they operate as independent contractors (self-employed workers). Some states, such as Florida, license referral agencies. The BLS classifies referral agencies within the Employment Services sector (NAICS 561310).

The BLS report on private household employment (NAICS 81400) shows that in 2012 over 16% of all U.S. household employees were home care workers (109,800 personal care aides, 2,900 home health aides, and 4,600 nursing assistants). Approximately 20% of all home care workers can be found in the private hire sector (BLS, 2012; Table 3).

Table 3.

Projected Growth of the Home Care Industry by Occupation: Estimated Number of U.S. Home Care Workers in 2012 and 2022.

| NAICS code | NAICS industry name | Estimated number of workers in 2012 and 2022 (in thousands)

|

Percent change from 2012 to 2022 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Home health aides (31-1011)a

|

Personal care aides (39-9021)a

|

Nursing assistants (31-1014)a

|

Sum of workers in industry

|

|||||||

| 2012 | 2022 | 2012 | 2022 | 2012 | 2022 | 2012 | 2022 | |||

| 621600 | Home health care services | 323 | 537.3 | 298.6 | 496.7 | 64.6 | 112.6 | 686.2 | 1146.6 | 67.1% |

| 624120 | Services for the elderly and persons with disabilities | 141.2 | 231.5 | 359 | 617.9 | 16.7 | 30.1 | 516.9 | 879.5 | 70.1% |

| 561300 | Employment services | 28.7 | 36.6 | 27.9 | 35.6 | 37.6 | 47.9 | 94.2 | 120.1 | 27.5% |

| TE1110 | Self-employed workers | 19.4 | 32.1 | 70.4 | 120.9 | 30.6 | 50.6 | 120.4 | 203.6 | 69.1% |

| 999200 | State government, excluding education and hospitals | 8.2 | 8.2 | 17.8 | 18 | 15.9 | 16 | 41.9 | 42.2 | 0.7% |

| 999300 | Local government, excluding education and hospitals | 7.7 | 8.3 | 11.8 | 12.6 | 33.8 | 11.8 | 53.3 | 32.7 | −38.6% |

| 814000 | Private households | 2.9 | 2.7 | 109.8 | 104.8 | 4.6 | 4.3 | 117.3 | 111.8 | −4.7% |

| Sum of workers in occupation | 531.1 | 856.7 | 895.3 | 1406.5 | 203.8 | 273.3 | 1630.2 | 2536.5 | 55.6% | |

Note. NAICS = North American Industry Classification System.

Standard occupation ID in parentheses.

Source. Bureau of Labor Statistics (2012).

Sector 3.1: Public Authorities, Fiscal Intermediaries and Employment Services Agencies

The private-hire sector includes over half a million workers (IPs) associated with publically funded programs, mainly Medicaid (Notarstefano, 2010). Two thirds of IPs are based in California (Seavey & Marquand, 2011), which has the largest publicly funded personal care program in the United States: In-Home Supportive Services. Often IP workers are directed through a quasi-governmental entity, called a public authority, which acts as the employer of record. In these “consumer-directed” care models, the eligible recipient is responsible for locating, screening, scheduling, and supervising the worker who is paid through the public authority (Smith, 2007a). Notably, the majority of workers affiliated with public authorities are paid family caregivers (Seavey & Marquand, 2011). In California, for example, about 72% of In-Home Supportive Services recipients receive care from a relative (California Legislative Analyst’s Office, 2012). The sponsoring government authority takes on payroll processing and negotiates with unions on pay and benefits issues.

Some states play a fiscal intermediary role but have not created separate public authorities for their Medicaid workers, and some do not take on the role of “employer of record” (Seavey & Marquand, 2011). Still others contract with companies for fiscal intermediary services. The BLS classifies these companies in the Employment Services sector (NAICS 561300). Last, in states without public authorities or fiscal intermediaries, workers of publically funded programs are treated as either independent contractors or employees of the recipient or government body. Although there is considerable state variability resulting in data tracking challenges, PHI estimates there are 800,000 IPs and that the vast majority are not captured in BLS surveys (Seavey, 2012).

Sector 3.2: The Underground Economy

There are an unknown number of home care workers hired by households and paid privately that go unreported to the government. This underground economy raises concerns about potential risks of abuse to workers and care recipients, lost revenues to government in unpaid taxes, and workers lacking legal protections and benefits. Although the size of this underground economy is unknown, studies indicate approximately $2 trillion in unreported income from all U.S. economic sectors (Cebula & Feige, 2012).

Sector 4: Government Agencies

Myriad government agencies provide direct home care services to qualified recipients including state and county caregiver assistance programs, respite programs, and in-home support contracts. In 2012, 41,900 home care workers were employed within the State Government industry sector (NAICS 999200) and 53,000 in the Local Government sector (NAICS 999300; BLS, 2012).

The VA pays for home care for qualified veterans and their families through the Aid and Attendance Benefit, which increases the pension payments for those eligible, and another program whereby the VA contracts for caregiver services with approved home health and similar public and private agencies to train and pay family caregivers directly (Statement of Madhulika Agarwal, 2009). Because neither VA program pays the caregivers directly, they are not government employees and thus not included in the government agencies’ statistics reported in this section (NAICS 999200 or NAICS 999300); rather, they are included in the other sectors reported above.

Table 3 shows the relative sizes and projected growth of the home care industry based on BLS survey data. According to the BLS (2013c), personal care aides and home health aides are the second and third fastest growing occupations in the United States. A majority (almost 58%) of home care workers are employed outside the home health care industry as traditionally defined by the NAICS: about 32% work for aging service providers including home care aide agencies; 20% work in the private hire sector (7% self-employed, 6% employment services, 7% private household employees); and nearly 6% work for local or state governments. Forty-two percent of home care workers are employed by home health care or hospice agencies (BLS, 2012).

Home Care Studies, Data Gaps, and Policy

The Streetlight Effect in Home Care Studies

While we have identified four distinct sectors in the formal home care industry, most major national studies focus only on one, home health care. We argue that this lack of research is best explained by the Streetlight Effect. Because they are licensed or certified, home health care establishments are the most accessible for data collection. This is especially true of the subset that is Medicare certified. Lack of research on the other sectors, their practices, recipients, and workers, coupled with the assumption by many that home health care agencies represent the entire industry, distorts the picture we have of this highly complex field.

The NHHCS, conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the primary source of data on home care in the United States, provides an example. The NHHCS samples agencies that are certified by Medicare/Medicaid or licensed by a State to provide home health and/or hospice services (CDC, 2011a), and excludes agencies that provide only homemaker/housekeeping services or assistance with instrumental activities of daily living. Also excluded are IPs involved with Medicaid programs, workers employed privately in households, and workers in state and local government programs. As shown in Table 3, the majority of home care workers and their employers are excluded. Thus, NHHCS overrepresents restorative and underrepresents supportive nonmedical home care.

The CDC has conducted related surveys including the National Nursing Home Survey and the National Survey of Residential Care Facilities but has not explicitly surveyed personal care aide providers, public authority workers, or independent home care workers (CDC, 2011b, 2013). In 2012, the CDC began an integrative initiative combining studies into the NSLTCP. The NSLTCP plans to collect primary data biannually using nationally representative provider sample surveys for which CMS administrative data do not exist, but home health agencies are not included. Rather, administrative data will be used to capture home health agencies suggesting that only Medicare-/Medicaid-certified agencies and licensed home health agencies will continue to be included (CDC, 2014).

The NHEA by the CMS is another important source, using a national matrix of health spending data by service type and funding source (CMS, 2014). Reports from the National Health Policy Forum using NHEA data state that nearly 40% of total LTSS spending is on home health care and other HCBS (Martin, Lassman, Washington, & Catlin, 2009; O’Shaughnessy, 2012) and that Medicaid is the predominant payer source, followed by out-of-pocket payments by consumers (O’Shaughnessy, 2012). Yet, the NHEA explicitly states: “non-medical types of home care … are excluded” (CMS, 2014, p. 2) as are private household employers. The NHEA does, however, include “home and community based waiver services,” funded by Medicaid. Including waiver services but excluding private household workers and personal care aide agencies that do not participate in waiver programs skews the sample toward publically funded services. As a result, analyses of LTSS spending using these data sources underreport spending by those who do not qualify for public services.

Several large national studies offer a partial solution to addressing these gaps. For example, the HRS is a major source of information about older adults’ health, wealth, insurance coverage, work status, and family supports (HRS, 2014). Using in-depth biennial interviews of a nationally representative sample of adults over age 50, it was designed to inform the national retirement discussion as the population ages. Although the HRS avoids Streetlight Effects through its sampling, broad focus, and careful measurement, questions on home care usage are limited and lack specificity to address some of the questions needed for a comprehensive understanding of the home care industry. The core survey asks: “Since Respondent’s [last interview/in the last two years], has any medically-trained person come to your home to help you, yourself?” (Medically trained persons are defined to include professional nurses, visiting nurse’s aides, physical or occupational therapists, chemotherapists, and respiratory oxygen therapists.) It also asks if the costs for these services were covered by insurance and about out-of-pocket payments for in-home medical care but does not specify which types of services. Moreover, an analysis by Goldman, Zissimopoulos, and Lu (2011) noted that high nonresponse rates were common on questions about out-of-pocket home health spending.

The HRS also asks respondents about functional disabilities and whether they received help. Again, however, inquiries are general and do not cover how often help was provided and who paid for it if assistance was provided by someone other than an informal family caregiver.

The National Long-Term Care Survey (NLTCS) offers another example of a study that avoids the Streetlight Effect. It used longitudinal, community-based representative samples to examine changes in the health status of older Americans and track health expenditures, Medicare service use, and the availability and use of personal and community resources for caregiving. The last NLTCS survey, conducted in 2004, produced findings that counter some of those derived from the more limited sampling of the NHHCS and NHEA. For example, it shows that among older persons with chronic disabilities who reported receiving any paid home care, 54% pay out-of-pocket, followed by Medicare (25%) and Medicaid (18%). When the population of community elders with disabilities is considered, only 11% received any publically funded home and community-based care in 2004 (Doty, 2010). This is consistent with reports that older persons generally pay for LTSS using out-of-pocket funds first, and turn to Medicaid for support after they have spent down (Kane, 2012).

A follow-up to the NLTCS, the National Health and Aging Trends Study uses a nationally representative sample of Medicare beneficiaries aged 65 and older who are interviewed annually about their activities of daily living and use of supportive services. The study began its first round of data collection in 2011. Reports of findings are forthcoming and may help resolve some of the Streetlight Effect in home care research.

The Private Duty Benchmarking Studies, annual surveys of home care aide agencies conducted by Home Care Pulse, provide information about supportive home care. Because they are designed for industry rather than research and policy purposes, these studies lack widespread distribution (Home Care Pulse, 2011, 2014). Moreover, their focus is on nonmedical home care agencies, not the universe of home care.

Focusing on a different sector, PHI and the Direct Care Workforce Alliance are conducting studies of workers in the Medicaid home care programs (Edelstein & Seavey, 2009). They are also analyzing BLS data; however, limitations in the BLS data described earlier hamper their efforts to broaden our understanding of home care providers and workers.

Policy Implications of the Streetlight Effect

The Streetlight Effect in home care, which represents large and generally unrecognized gaps in information about the supply, use, costs, workers, and characteristics of home care services overall, has potentially profound policy implications. We argue that the current focus, which is predominately on the home health care sector, is often assumed to include other areas of home care as well. One of the largest misperceptions that results from this is that public programs fund the majority of HCBS. If HCBS refers to the universe of services available to support older persons in the community, then both Medicaid and non-Medicaid services, and supportive care as well as medically oriented care should be included. Yet the Congressional Budget Office (2013) recently reported:

Even though Medicare appears to account for the largest share of spending on services and supports received in the community…. Medicaid pays for a significant amount of community-based LTSS. Private insurance and other private sources of payment cover relatively little community-based care. (p. 23)

These estimates are based on published and unpublished data from the Medicare Beneficiary Annual Summary File, the NHEA (adjusted for elderly people), and the Medicaid Statistical Information System, which exclude private households and non-medical home care aid agencies, where most clients pay for personal care assistance with out-of-pocket funds rather than receive public benefits. Many reports on long-term care spending rely on data sets drawn primarily, if not exclusively, from the home health care sector (Martin et al., 2009; O’Shaughnessy, 2012), and their studies are cited by others (e.g., Notarstefano, 2010; The SCAN Foundation, 2013) and in testimony and reports to Congress (Fair Home Healthcare Act, 2007; Reauthorization of the Older Americans Act, 2005; Stone, 2010), and in regulatory policy making.

Another example of policy makers relying on data from one sector is the recent Department of Labor proposed rule change on minimum wage and overtime for home care companions. Although this change has implications for both Medicaid home care recipients and private pay consumers, the Department of Labor (2011) asserted that the change would not significantly affect businesses or consumers because “public funds pay the overwhelming majority of the cost for providing home care services. Medicaid payments represent nearly 40 percent of the industry’s total revenues…. Out-of-pocket funds account for 10 percent of agency revenues” (p. 81191–81192). This information was based on data from the National Health Expenditures Accounts, a sample that excludes home care aide agencies and private households as described earlier. Looking at data from representative community-based samples, however, such as the NLTCS cited above, 54% of chronically disabled older persons who received paid home care reported that they paid with out-of-pocket funds. A national study of home care aide agencies reported their primary payment sources were 70% from out-of-pocket funds from consumers and only 17% from publically funded programs in 2013 (Home Care Pulse, 2014).

Recommendations and Future Research

Eliminating the Streetlight Effect will allow us to better address a number of questions important for policy making. These include questions related to consumer needs, demand, and preferences; worker experiences, shortages, and needs; adequate supply of agency providers and which types of providers are needed; costs of care to different payers (e.g., families, governments); outcomes of care; regulation of workers and providers; and the interface between informal and formal care. How do workers’ duties, schedules and hours, pay, entry requirements, job satisfaction, and retention rates vary between types of agencies and compared to private hires? How do the care recipients’ experiences differ across the types of home care models in terms of met needs and outcomes? How does the ownership, size, licensure, or type of agency affect practices, costs, outcomes, or access? How do licensure scope-of-practice regulations (defining who is allowed to provide which services) differ across agencies and states, and how do they affect substitutability of one formal home care provider for another? How are “episodes of care” defined and measured, and how do quantities of home care used vary across agencies?

To address the Streetlight Effect, data are needed that include all sectors of home care. An aggressive expansion and refinement of existing home care data is essential to understand needs, cost, supply, quality, and trends and to monitor the effects of policy changes. We propose the following recommendations for consideration by involved stakeholders:

Expand national studies of home care to include all sectors of the home care industry (home health, home care aide, government providers, independent workers, and private household employers). This can be done by including underrepresented sectors in the current studies and/or undertaking parallel studies of the various sectors. For example, the National Study of Long-Term Care Providers should regularly conduct a National Survey of Home Care Aide Providers just as they study other major LTSS providers.

Refine the NAICS industry categories—“Services for the Elderly and Persons with Disabilities” (624120) and “Home Health Care Services” (621610). Currently, there is no separate industry category to distinguish home care aide providers from all other community services. The separate NAICS industry categories needed are: (a) “Home Care Aide Agencies”; (b) “Home Care Registries”; and (c) “Public authorities and Fiscal intermediaries.” The supportive housing industry has refinement in their NAICS industry categories that could serve as a model. Also, nonmedical home care services are included in Home Health Care Services (621610), further muddying the categorization. For this category, home health care agencies, hospices, durable medical equipment providers, and infusion therapy providers all need distinct industry codes.

Use a consistent unit of analysis for data collection and industry tracking. Studies of home care providers should follow the BLS model and use “establishments” as their unit of analysis. Additional data can be collected on number of licenses and businesses, but these units of analysis should be treated as conceptually distinct.

When home care studies are designed and reported, clearer articulation of their samples and of the limitations of their findings is needed.

This article focuses on formal paid home care and identifies areas where clarification and additional research are needed. Informal home care, whether provided by families, friends, or community volunteers, is a critical resource for LTSS but beyond the scope of this article. This study also does not address important questions about defining “episodes of care” or measuring “quantities of care provided” across different types of agencies. Further research is needed to address these topics. We have attempted to begin to expand our understanding of home care by mapping the formal home care sectors, and calling for more research to deepen our knowledge of the understudied sectors.

Conclusion

Increasingly, the trend in LTSS is for home-based supports for seniors and persons with disabilities. The Affordable Care Act targets improving chronic care. Home care is an essential component of both chronic care and the LTSS system because it is there that the medical, social, and personal needs of individuals converge. This article presents a review and critique of the current data on formal home care in the United States to show where important gaps in our knowledge are located, the size and implications of those gaps, and some recommendations for eliminating the Streetlight Effect. Many important studies have laid a foundation, but for policies to be most effective we need to expand our knowledge of the entire universe of home care.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Support from an NIA student training grant (No. T32AG000037).

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Benjamin AE, Matthias RE. Age, consumer direction, and outcomes of supportive services at home. The Gerontologist. 2001;41:632–642. doi: 10.1093/geront/41.5.632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin AE, Matthias RE, Franke TM. Comparing consumer-directed and agency models for providing supportive services at home. Health Services Research. 2000;35:351–366. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of Labor Statistics. Employment projections: Industry-occupation matrix 2012–2022. 2012 [Data file]. Retrieved from http://www.bls.gov/emp/tables.htm.

- Bureau of Labor Statistics. Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages: NAICS 621610—Home Health Care Services. 2013a Series ID: ENUUS000205621610 [Data file]. Retrieved from http://data.bls.gov/projections/nationalMatrix?queryParams=31-1011-3609&ioType=o.

- Bureau of Labor Statistics. Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages: NAICS 624120—Services for the elderly and disabled. 2013b Series ID: ENUUS000205624120. [Data file]. Retrieved from http://data.bls.gov/projections/nationalMatrix?queryParams=624120&ioType=i.

- Bureau of Labor Statistics. Employment projections: Table 1.3 Fastest growing occupations, 2012 and projected 2022. 2013c Dec; Retrieved from http://www.bls.gov/emp/ep_table_103.htm.

- Califonia Association for Health Services at Home. Policy update: How large is California’s home care industry? CAHSAH Bulletin. 2009 Dec;25(12):4. Retrieved from http://cahsah.org/documents/734_dec09bulletin.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- California Legislative Analyst’s Office. In-home supportive services: Background and policy considerations of proposed integration into Medi-Cal managed care. 2012 Mar 12; Retrieved from http://www.lao.ca.gov/Publications/Detail/2604.

- Cebula RJ, Feige EL. America’s unreported economy: Measuring the size, growth and determinants of income tax evasion in the U.S. Crime, Law, & Social Change. 2012;57:265–285. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Home and Hospice Care Survey. 2011a Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhhcs/about_nhhcs.htm.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Nursing Home Survey. 2011b Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nnhs.htm.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Survey of Residential Care Facilities. 2013 Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nsrcf.htm.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National study of long-term care providers. 2014 Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nsltcp.htm.

- Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services. OSCAR data. 2011 Apr; Retrieved from http://www.nahc.org/assets/1/7/2011hhas.pdf. [PubMed]

- Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Quick definitions for NHEA categories. 2014 Retrieved from http://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/Downloads/quickref.pdf.

- Congressional Budget Office. Methods for analysis of the financing and use of long-term care services and supports. Washington, DC: Author; 2013. Publication No. 4240. [Google Scholar]

- DecisionHealth. Private duty home care state licensing laws. 2014 Retrieved from http://privateduty.decisionhealth.com/StateLaws.aspx.

- Doty P. The evolving balance of formal and informal, institutional and non-institutional long-term care for older Americans: A thirty-year perspective. Public Policy and Aging Report. 2010;20(1):3–8. [Google Scholar]

- Edelstein S, Seavey D. The need for monitoring the long-term care direct service workforce and recommendations for data collection. Washington, DC: National Direct Service Workforce Resource Center; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Fair Home Healthcare Act (H.R.: 3582): Hearing before Subcommittee on Workforce Protections, House of Representatives, 110th Cong. 1 (2007) (testimony of C. Becker).

- Feinberg L, Reinhard SC, Houser A, Choula R. Valuing the invaluable: 2011 update, the growing contributions and costs of family caregiving. AARP Public Policy Institute Report. 2011 Jul; Retrieved from http://www.aarp.org/relationships/caregiving/info-07-2011/valuing-the-invaluable.html.

- Freeman DH. Why scientific studies are so wrong: The streetlight effect. Discover. 2010;31(6):55–57. [Google Scholar]

- Goldman DP, Zissimopoulos J, Lu Y. Medical expenditure measures in the health and retirement study. Forum for Health Economics & Policy. 2011;14(3):1–27. doi: 10.2202/1558-9544.1267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris-Kojetin L, Sengupta M, Park-Lee E, Valverde R. Long-term care services in the US: 2013 overview. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health and Retirement Study. About the health and retirement study. 2014 Retrieved from http://hrsonline.isr.umich.edu/

- Home Care Pulse. 2011 annual private duty home care benchmarking study. Rexburg, ID: Author; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Home Care Pulse. Private duty benchmarking study. 4. Rexburg, ID: Author; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Home Care Pulse. 2014 annual private duty home care benchmarking study. 2014 Retrieved from http://benchmarking.homecarepulse.com/2014-private-duty-study/

- Kane RA. Goals of home care. Journal of Aging and Health. 1999;11:299–321. doi: 10.1177/089826439901100303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane RA. Thirty years of home and community-based services: Getting closer and closer to home. Generations. 2012;36(1):6–13. [Google Scholar]

- Martin AB, Lassman D, Washington B, Catlin A. Growth in U.S. health spending remained slow in 2010: Health share of gross domestic product was unchanged from 2009. Health Affairs. 2012;31:1208–1219. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Association for Home Care and Hospice. Basic statistics on home care. 2010 Retrieved from http://www.nahc.org/assets/1/7/10HC_Stats.pdf.

- Notarstefano P. Non-medical homecare: A first step to providing home & community-based services (AAHSA Brief) Washington, DC: LeadingAge; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- O’Shaughnessy CV. The basics: National spending for long-term services and supports. Washington, DC: National Health Policy Forum; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- O’Toole G. Did you lose the keys here? No, but the light is much better here. 2013 Retrieved from http://quoteinvestigator.com/2013/04/11/better-light/#note-5967-1.

- Pratt JR. Long-term care, managing across the continuum. 3. Sudbury, MA: Jones & Bartlett; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Reauthorization of the Older Americans Act: Hearing before Subcommittee on Retirement Security and Aging Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions, Senate (2005) (testimony of J. Cabonell).

- Smith PR. Aging and caring in the home: Regulating paid domesticity in the twenty-first century. Iowa Law Review. 2007a;92:1837–1904. [Google Scholar]

- Smith PR. Home sweet home: Workplace casualties of consumer-directed home care for the elderly. Notre Dame Journal of Law, Ethics & Public Policy. 2007b;21:537–560. [Google Scholar]

- Stone RI. Consumer direction in long-term care. Generations. 2000;24(3):5–9. [Google Scholar]

- Stone J. Long-term care: Financing overview and issues for congress. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service; 2010. Report No. R40718. [Google Scholar]

- The SCAN Foundation. Who pays for long-term care in the US? Fact Sheet. 2013;2013 Retrieved from http://www.thescanfoundation.org/who-pays-long-term-care-us. [Google Scholar]

- Seavey D. PAS workforce and informal caregivers: State of the research. San Francisco, CA: Center for Personal Assistance Services; 2012. Sep, PHI Research Brief. [Google Scholar]

- Seavey D, Marquand A. Caring in America: A comprehensive analysis of the nation’s fastest-growing jobs: Home health and personal care aides. New York, NY: Paraprofessional Heath Institute; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Seyden N, Robert B. The history of in-home support services and public authorities in California. 2006 Retrieved from http://www.cicaihss.org/ihss-public-authority-history.

- Statement of Madhulika Agarwal, Chief Officer, Patient Care Services, Veterans Health Administration, Department of Veterans Affairs: Hearing before the Subcommittee on Health, Committee on Veterans Affairs, House of Representatives. 101st Cong; 2009. Retrieved from http://www.va.gov/OCA/testimony/hvac/sh/090604MA.asp. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. Statistical abstract of the United States: Resident population by age and state. 2010 [Data file]. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/compendia/statab/2012/tables/12s0016.pdf.

- U.S. Census Bureau. North American Industry Classification System. 2012 Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/eos/www/naics/

- U.S. Department of Labor. Federal Register. 248. Vol. 76. Washington, DC: 2011. Dec 27, Application of the Fair Labor Standards Act to Domestic Service: Notice of Proposed Rulemaking. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics. Employment by industry, occupation, percent distribution, 2010 and projected 2020. 2010 [Data file]. Retrieved from http://www.bls.gov/emp/tables.htm.