Abstract

Objective

Obesity represents a major public health problem and identifying natural compounds that modulate energy balance and glucose homeostasis is of interest for combating obesity and its associated disorders. The naphthoquinone shikonin has diverse beneficial properties including anti-inflammatory, anti-oxidant and anti-microbial effects. The objective of this study is to investigate the effects of shikonin on adiposity and glucose homeostasis.

Methods

To that end, we determined the metabolic effects of shikonin treatment on mice fed regular chow or challenged with a high fat diet (HFD).

Results

Shikonin treated mice fed regular chow exhibited improved glucose tolerance. In addition, shikonin treated mice fed HFD displayed decreased weight gain and resistance to HFD-induced glucose intolerance. Further, shikonin treatment decreased HFD-induced hepatic dyslipidemia. These findings correlated with enhanced hepatic insulin signaling in shikonin treated mice fed regular chow or HFD as evidenced by increased tyrosyl phosphorylation of the insulin receptor and enhanced downstream signaling.

Conclusion

These studies identify shikonin as a potential regulator of systemic glucose tolerance, energy balance and adiposity in vivo.

Keywords: Shikonin, glucose homeostasis, body weight and adiposity

Introduction

Obesity is a growing epidemic that presents a major health problem worldwide1, 2. Obese individuals are at a higher risk of chronic diseases including cardiovascular diseases, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and type 2 diabetes3, 4. Type 2 diabetes is a complex, polygenic disease that is characterized by increased insulin resistance in insulin-responsive tissues such as liver, adipose and skeletal muscle4. Insulin action is mediated by a complex network of signaling events that are initiated upon insulin binding to the insulin receptor (IR)5. Currently, few therapies are available for treating obesity and its associated comorbidities in humans. Thus, identifying compounds that modulate energy balance and glucose homeostasis is of major interest for combating obesity and its associated disorders including type 2 diabetes.

Shikonin is a liposoluble naphthoquinone isolated from Lithospermum erythrorhizon and has long been used in traditional herbal medicine for the treatment of measles, oozing dermatitis, burns and wound healing6. Shikonin was reported to possess different medicinal properties such as anti-inflammatory, anti-cancer and anti-microbial effects7–11. The molecular bases for shikonin anti-inflammatory activities encompass inhibition of cyclooxygenase-2 transcription, attenuation of mast cell degranulation, inhibition of neutrophil respiratory burst, proteasome inhibition and inhibition of pyruvate kinase M2 (PKM2), among others12–17. The anti-cancer activities of shikonin involve inhibition of DNA topoisomerase, induction of apoptosis and inhibition of PKM2, among others 18–20. In addition, several studies establish salutary effects of shikonin in metabolic regulation, in particular enhancing glucose uptake and inhibiting adipogenesis. Shikonin stimulates glucose uptake in 3T3-L1 adipocytes, primary adipocytes and cardiomyocytes21, in part through inhibiting phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chormosome 10 (PTEN) and protein-tyrosine phosphatase 1B (PTP1B)22. Moreover, shikonin treatment enhances glucose transporter 4 (GLUT4) translocation and glucose uptake in skeletal muscle and improves plasma glucose levels in diabetic rats23. Further, shikonin inhibits adipogenesis in 3T3-L1 adipocytes, in part, by modulating WNT/β-catenin24, 25 and attenuating ERK1/226 signaling. In this study we examined the metabolic effects of shikonin treatment on body mass and glucose homeostasis using mice fed regular chow and high fat diet.

Methods

Mouse studies

All mice used in these studies were males and on a C57BL/6J background. Mice were age-matched and were maintained on a 12-hour light-dark cycle with free access to water and food. Mice were fed standard lab chow (Purina lab chow, # 5001), and in some experiments, switched to a high fat diet (HFD; 60% kcal from fat, # D12492, Research Diets) at 6 weeks of age. Mice were treated with shikonin (2 mg/kg/day) for 5 consecutive days as previously described27 and outlined in figure 1A. Briefly, shikonin was dissolved in DMSO at a concentration of 10 mg/ml and then diluted in pre-warmed PBS to a final concentration of 0.2 mg/ml before injection. Control, non-treated mice were injected with DMSO (similar dilutions as shikonin solution) as a vehicle control. Mice received a final injected volume of 1% of their body weight. For body composition studies whole-body fat and lean mass were assessed as described28 using the quantitative magnetic resonance method (Echo, MRI 3-in-1, Echo Medical Systems). All mouse studies were conducted in line with federal regulations and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at University of California Davis.

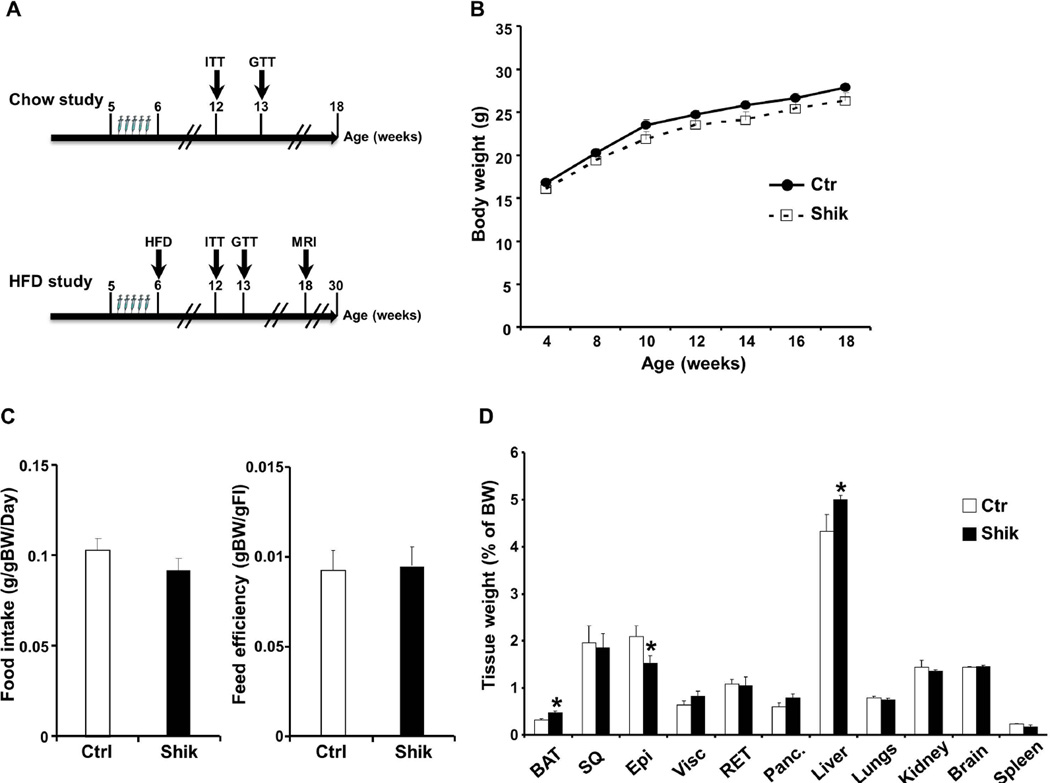

Figure 1. Effects of shikonin treatment on body weight and adiposity in mice fed regular chow diet.

A) Schematic representation of experimental timeline for administering shikonin and evaluating metabolic parameters in mice fed regular chow and HFD. B) Body weight of male mice fed regular chow diet for 18 weeks without (Ctr; n=9) and with (Shik; n=12) shikonin treatment. C) Food intake (adjusted to body weight) and feed efficiency in male mice without (n=9) and with shikonin treatment (n=12) at 12 weeks. D) Tissue weights of mice without (n=9) and with shikonin treatment (n=12) at 18 weeks. *p<0.05 indicates significant difference between control and shikonin-treated mice.

Metabolic measurements

Glucose was measured in blood collected from the tail using a glucometer (Home Aide Diagnostics). Serum insulin was determined by enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) using mouse insulin as a standard (Crystal Chem). Free fatty acid (FFA) and triglyceride (TG) concentrations were measured by an enzymatic colorimetric method (Wako). Fed glucose measurements were taken between 7–9 am and, where indicated, from mice fasted for 12 h. For insulin tolerance tests (ITTs), mice were fasted for 4 h and injected intraperitoneally (i.p.) with 0.75 U/kg body weight human insulin (HumulinR; Eli Lilly). Blood glucose values were measured before and at 15, 30, 45, 60, 90 and 120 min post-injection. For glucose tolerance tests (GTTs), overnight-fasted mice were injected with 20% D-glucose at 2 mg/g body weight, and glucose was measured before and at 30, 60, 90 and 120 min following injection.

Biochemical analyses

Tissues were ground in liquid nitrogen and lysed using RIPA buffer. Lysates were clarified by centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 10 min and protein concentrations were determined using bicinchoninic acid protein assay kit (Pierce Chemical). Proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes. Immunoblotting of lysates was performed with antibodies for pERK1/2 (Tyr202/Thr204), ERK1/2, pAKT (Ser473), AKT, pSTAT3 (Tyr705), STAT3 (Cell Signaling Technology), IRS1 (Millipore), pIR (Tyr1162/Tyr1163), IR and Tubulin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Proteins were visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL, Amersham Biosciences) and pixel intensities of immuno-reactive bands were quantified using FluorChem 8900 (Alpha Innotech). Data for phosphorylated proteins are presented as phosphorylation level normalized to protein expression.

RT-PCR analyses

Total RNA was extracted from liver samples using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). cDNA was generated using high-capacity cDNA synthesis Kit (Applied Biosystems). Srebp1c, Scd1, Cpt1a, Mttp1, Atgl, Hsl, Pepck and G6pase were assessed by SYBR Green quantitative real time PCR using SsoAdvanced™ Universal SYBR® Green Supermix (iCycler, BioRad). Relative gene expression was quantitated using the ΔCT method with appropriate primers (Table 1) and normalized to Tata-box binding protein (Tbp). Briefly, the threshold cycle (Ct) was determined and relative gene expression was calculated as follows: fold change=2−Δ(ΔCt), where ΔCt=Ct target gene−Ct TBP (cycle difference) and Δ(ΔCt)=Ct (treated mice)−/Ct (control mice).

Table 1.

Primer sequences used to quantitate Srebp1c, Scd1, Cpt1a, Mttp1, Atgl, Hsl, Pepck, G6Pase and TBP expression.

| Gene | Forward 5’–>3’ | Reverse 5'–>3' |

|---|---|---|

| Atgl | AGTTCAACCTTCGCAATCTC | GTCACCCAATTTCCTCTTGG |

| Cpt1a | CTCCGCCTGAGCCATGAAG | CACCAGTGATGATGCCATTCT |

| G6Pase | TCGGAGACTGGTTCAACCTC | ACAGGTGACAGGGAACTGCT |

| Hsl | CATCTTTGGCTTCAGCCTCTTCCT | ATGGCTCAACTCCTTCCTGGAACT |

| Mttp1 | CTCTTGGCAGTGCTTTTTCTCT | GAGCTTGTATAGCCGCTCATT |

| Pepck | CTAACTTGGCCATGATGAACC | CTTCACTGAGGTGCCAGGAG |

| Scd1 | TTCTTGCGATACACTCTGGTGC | CGGGATTGAATGTTCTTGTCGT |

| Serbp1c | GAGCCATGGATTGCACATTT | CTCAGGAGAGTTGGCACCTG |

| Tbp | TTGGCTAGGTTTCTGCGGTC | GCCCTGAGCATAAGGTGGAA |

Statistical analyses

Data are expressed as means ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical analyses were performed using the JMP program (SAS Institute). ITTs, GTTs, body weight and adiposity data were analyzed by analysis of variance (ANOVA). Post-hoc analysis was performed using Tukey-Kramer honestly significant difference test. For biochemistry studies, comparisons between groups were performed using unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test. Differences were considered significant at p<0.05 and highly significant at p<0.01.

Results

Improved glucose tolerance in shikonin-treated mice fed regular chow diet

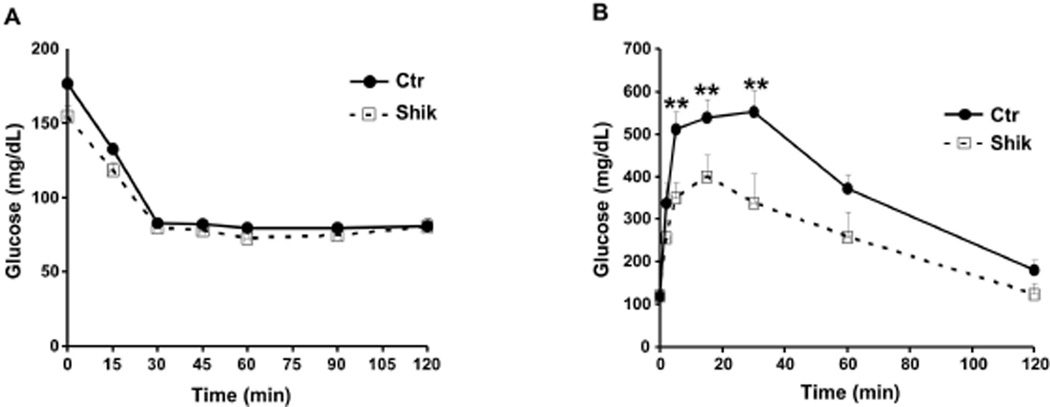

To investigate the metabolic effects of shikonin in vivo we determined body weight and glucose homeostasis in shikonin treated mice fed regular chow as detailed in Methods (Fig. 1A). Body weights of control and shikonin treated mice were comparable suggesting that any differences in systemic glucose tolerance were likely primary and not due to body weight alterations (Fig. 1B). In addition, food intake (adjusted to body weight) and feed efficiency were comparable between control and shikonin treated mice (Fig. 1C). In line with these observations, tissue weights were comparable between groups, however shikonin treated mice displayed nominal increase in brown adipose tissue (BAT) and liver weights and nominal decrease in epididymal fat weight compared with controls (Fig. 1D). Moreover, we assayed several metabolic parameters of whole body glucose and lipid homeostasis (Table 2). Shikonin treated mice displayed significantly lower fed and fasted glucose and insulin concentrations compared with controls. In addition, fed and fasted serum free fatty acid concentrations were comparable, but shikonin treated mice displayed increased fed and fasted serum triglycerides compared with controls (Table 2). To directly assess insulin sensitivity, mice were subjected to insulin tolerance tests (ITTs) as detailed in Methods. After insulin injection shikonin treated mice exhibited comparable reduction in blood glucose to controls (Fig. 2A). On the other hand, shikonin treated mice displayed significantly increased ability to clear glucose from the peripheral circulation during glucose tolerance tests (GTTs) indicating improved glucose tolerance (Fig. 2B). Together, these findings demonstrate that shikonin treatment of mice fed regular chow does not significantly alter body weight but enhances glucose tolerance.

Table 2. Metabolic variables in mice with and without shikonin treatment fed regular chow and HFD.

Male mice with and without shikonin treatment were fed regular chow or HFD. Serum was collected from fed or fasted mice at 12 weeks of age (6 weeks on HFD) and the indicated metabolic parameters were measured. Values are expressed as the mean ± SEM of measurements obtained for 6–8 animals per genotype.

| Chow | HFD | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ctrl | Shik | Ctrl | Shik | ||

|

Glucose (mg/dl) |

Fed | 139.7 ± 5.8 | 119.3 ± 7.0** | 216.7 ± 6.6 | 185.3 ± 7.0** |

| Fasted | 89.4 ± 3.0 | 82.7 ± 2.5* | 204.5 ± 7.4 | 168.4 ± 7.5** | |

|

Insulin (ng/ml) |

Fed | 1.92 ± 0.06 | 1.24 ± 0.08** | 13.93 ± 0.37 | 4.82 ± 0.13** |

| Fasted | 0.92 ± 0.07 | 0.75 ± 0.04* | 1.53 ± 0.12 | 0.35 ± 0.11* | |

|

FFA (uEq/ml) |

Fed | 0.27 ± 0.10 | 0.36 ± 0.06 | 0.52 ± 0.05 | 0.45 ± 0.10 |

| Fasted | 0.72 ± 0.09 | 0.97 ± 0.13 | 0.67 ± 0.10 | 0.76 ± 0.03 | |

|

TG (mM) |

Fed | 1.25 ± 0.08 | 1.73 ± 0.12** | 1.77 ± 0.05 | 4.33 ± 0.07** |

| Fasted | 0.52 ± 0.08 | 0.97 ± 0.06** | 1.91 ± 0.08 | 2.13 ± 0.04 | |

p<0.05;

p<0.01 indicate statistically significant difference between control and shikonin-treated mice on either diet.

Figure 2. Enhanced glucose tolerance in shikonin-treated mice fed regular chow diet.

A) Insulin tolerance test (ITT) and (B) glucose tolerance tests (GTT) in male control (n=9) and shikonin treated (n=12) mice fed chow diet for 12 weeks. **p<0.01 indicate significant difference between control and shikonin treated mice at the indicated time.

Decreased body weight and adiposity in shikonin-treated mice fed HFD

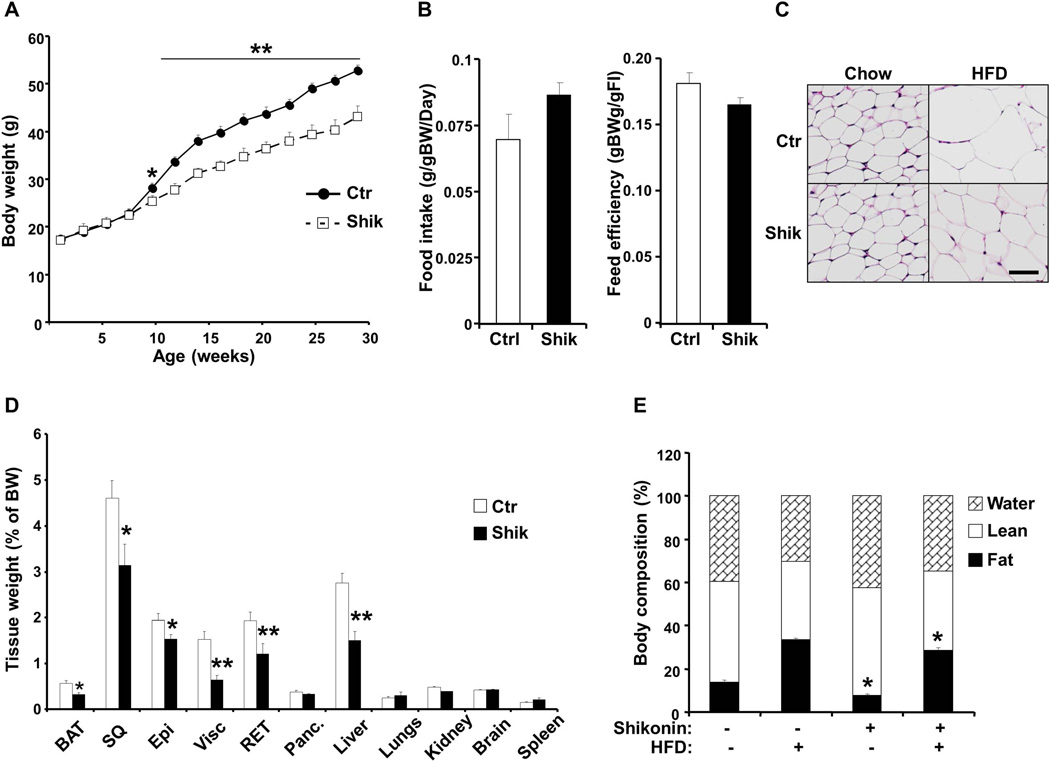

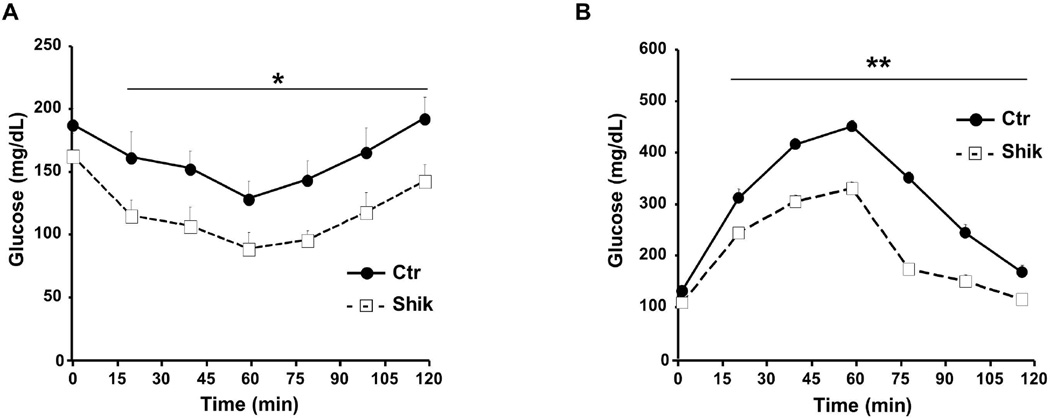

To investigate whether shikonin treatment affects energy balance, we determined body weights of mice fed HFD with and without shikonin treatment. Body weights of shikonin treated mice were significantly lower than controls and by week 30 shikonin treated mice weighed 14.7 ± 2.1 % less than controls (Fig. 3A). Comparable findings were observed in an independent cohort of mice and by week 20 shikonin-treated mice weighed 9.6 ± 3.7 % less than controls (data not shown). In addition, food intake (adjusted to body weight) and feed efficiency were comparable between shikonin treated and control mice, with shikonin treated mice exhibiting a trend for increased food intake (Fig. 3B). Consistent with decreased body weight, H&E stained subcutaneous white adipose tissue of shikonin treated mice fed HFD displayed smaller cell size compared with controls (Fig. 3C). To determine the tissues that contribute to decreased body weight in shikonin treated mice we performed body composition analysis on mice fed HFD for 24 weeks. Liver, BAT and WAT depots weights were significantly lower in shikonin treated mice compared with controls (Fig. 3D). To further evaluate effects of shikonin treatment on fat mass, we performed MRI analysis on mice fed regular chow for 18 weeks and HFD for 12 weeks with and without shikonin treatment (Fig. 3E). Consistent with previous observation, shikonin treatment decreased fat mass in mice fed chow and HFD and a trend for increased lean mass in mice fed HFD. Moreover, we assayed several parameters of whole body glucose and lipid homeostasis (Table 2). Shikonin treated mice fed HFD displayed significantly lower fed and fasted glucose and insulin concentrations compared with controls. On the other hand, fed and fasted serum free fatty acid concentrations were comparable between groups while fed serum triglycerides were elevated in shikonin treated mice compared with controls (Table 2). ITT revealed comparable overall reduction in blood glucose in shikonin treated mice compared with controls with shikonin treated mice exhibiting lower basal glucose (Fig. 4A). However, GTT revealed improved glucose tolerance in shikonin treated mice fed HFD compared with controls (Fig. 4B). Together, these findings provide in vivo evidence that shikonin treatment decreases adiposity and HFD-induced weight gain.

Figure 3. Decreased body weight and adiposity in shikonin-treated mice fed high fat diet.

A) Body weight of male control (n=7) and shikonin treated (n=10) mice fed high fat diet for 24 weeks B) Food intake (adjusted to body weight) and feed efficiency in control and shikonin-treated mice fed HFD for 12 weeks. C) Hematoxylin and Eosin-stained sections of subcutaneous WAT of control and shikonin-treated mice fed HFD for 24 weeks. Scale bar: 50µm. D) Tissue weight (percent of body weight) in male control (n=7) and shikonin-treated (n=10) mice fed HFD for 24 weeks. E) Body composition of control and shikonin treated mice fed chow diet for 18 weeks or HFD 12 weeks determined using a quantitative magnetic resonance method. n=6 per group. *p<0.05; **p<0.01 indicate significant difference between control and shikonin treated mice.

Figure 4. Enhanced glucose tolerance in shikonin-treated mice fed HFD.

A) Insulin tolerance test (ITT) and (B) glucose tolerance tests (GTT) in male control (n=7) and shikonin treated (n=10) mice fed HFD for 12 weeks. . *p<0.05; **p<0.01 indicate significant difference between control and shikonin treated mice at the indicated time.

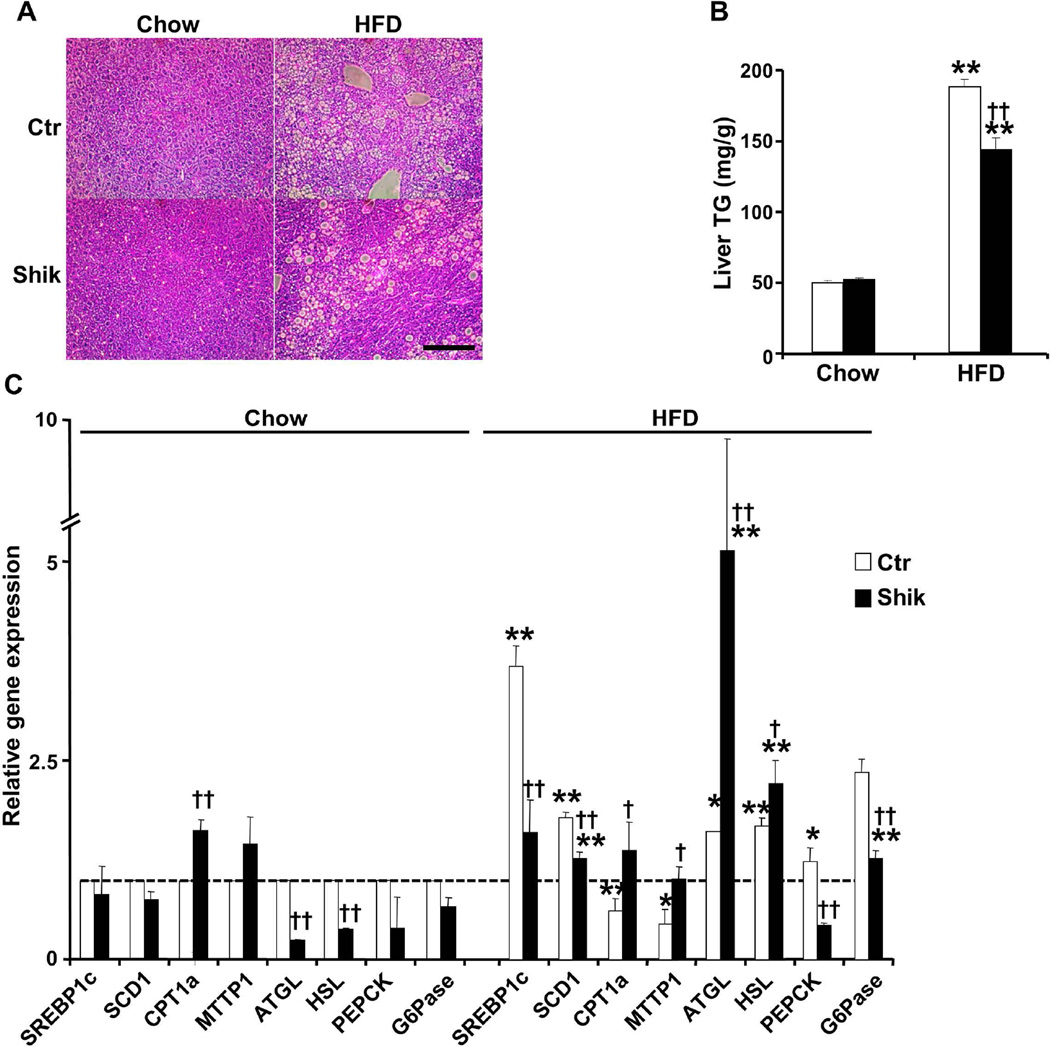

Decreased hepatic dyslipidemia in shikonin treated mice fed HFD

High fat feeding causes accumulation of lipids in the liver, a process that leads to fatty liver disease and eventually to non-alcoholic steatohepatitis29. H&E staining of liver sections of control mice fed chow and HFD revealed increased lipid accumulation upon high fat feeding (Fig. 5A). However, shikonin treated mice presented with a lower number of lipid droplets than controls. In addition, liver triglycerides concentration was decreased in shikonin treated mice compared with controls fed HFD (Fig. 5B). Consistent with these findings, hepatic mRNA of lipogenic genes such as sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1 (Srebp1c) and stearoyl-CoA desaturase (Scd1) was significantly lower in shikonin treated mice fed HFD compared with controls (Fig. 5C). In addition, hepatic mRNA of carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1a (Cpt1a) that is implicated in β-oxidation was increased in shikonin treated mice fed chow and HFD. Similarly, gene for VLDL secretion, such as microsomal triglyceride transfer protein (Mttp) was increased in shikonin-treated mice fed HFD compared with controls. Moreover, adipose triglyceride lipase (Atgl) and hormone sensitive lipase (Hsl) mRNA was increased in livers of shikonin treated mice fed HFD compared with controls. Finally, hepatic gluconeogenesis genes phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (Pepck) and glucose 6 phosphatase (G6pase) were decreased in shikonin treated mice fed HFD consistent with their improved glucose tolerance. Together, these findings suggest that shikonin treatment may confer protection against development of HFD-induced hepatic dyslipidemia.

Figure 5. Decreased hepatic dyslipidemia in shikonin-treated mice fed HFD.

A) Hematoxylin and Eosin-stained of liver from control and shikonin-treated mice fed HFD for 24 weeks. Scale bar: 100µm. B) Hepatic triglyceride of control and shikonin treated mice fed chow and HFD. Liver was harvested from fed chow and HFD mice at 18 or 30 weeks of age, respectively. Values are expressed as the mean ± SEM of measurements obtained for 6–8 animals per genotype. **p<0.01 indicate statistically significant difference between chow and HFD. ††p<0.01 indicate statistically significant difference between control and shikonin treated mice on either diet. C) Quantitative real-time PCR determination of mRNA of genes implicated in fatty acids (FA) synthesis, FA oxidation, or FA uptake, and very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) secretion, lipolysis and gluconeogenesis (normalized against Tbp) in livers of control and shikonin-treated mice fed chow diet for 30 weeks and HFD for 24 weeks. *p<0.05; **p<0.01 indicate significant differences HFD versus chow fed mice. †p<0.05; ††p<0.01 indicate significant differences between shikonin treated versus non-treated mice.

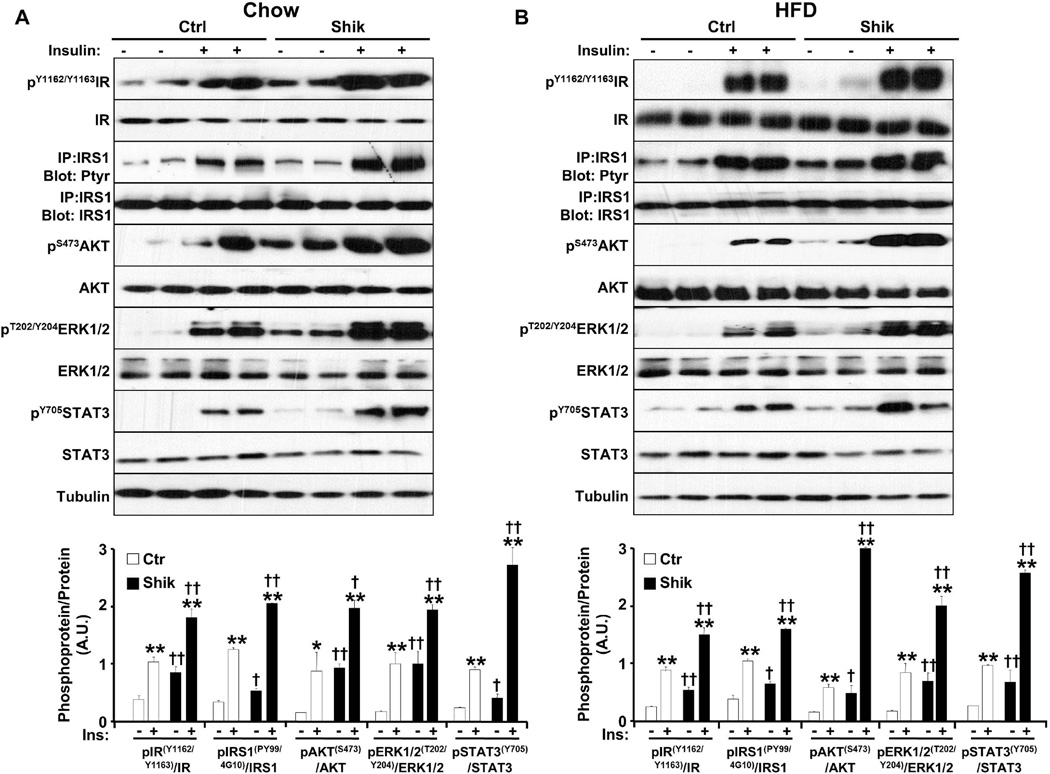

Increased hepatic insulin signaling in shikonin-treated mice

To decipher the molecular basis for enhanced glucose tolerance in shikonin treated mice, we investigated hepatic insulin signaling. We injected overnight fasted shikonin treated and control mice with insulin (10 units/kg) or saline and analyzed hepatic insulin signaling. Basal and insulin-induced tyrosyl phosphorylation of the IR at Tyr1162/Tyr1163 was increased in shikonin treated mice fed chow or HFD compared with controls (Fig. 6). Similarly, immunoprecipitates of IRS1 revealed increased basal and insulin-stimulated tyrosyl phosphorylation in shikonin treated mice fed chow or HFD compared with controls. In line with increased IR and IRS1 tyrosyl phosphorylation, basal and insulin-stimulated AKT phosphorylation on Ser473, and ERK1/2 phosphorylation on T202/Y204 were enhanced in shikonin treated mice. Finally, basal and insulin-induced tyrosyl phosphorylation of the signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) at Tyr705 was increased in shikonin treated mice fed chow or HFD compared with controls (Fig. 6). Taken together, these data suggest that enhanced glucose tolerance in shikonin treated mice is due, at least in part, to improved hepatic insulin sensitivity.

Figure 6. Increased hepatic insulin signaling in shikonin-treated mice.

Control and shikonin-treated mice (A) fed chow diet for 30 weeks or (B) high fat diet for 24 weeks were fasted overnight then injected i.p. with saline or insulin and sacrificed after 10 minutes. Total liver lysates were also immunoblotted with antibodies against pIR (Tyr1162/Tyr1163), pAKT (Ser473), pERK1/2 (Tyr202/Thr204), and pSTAT3 (Tyr705) and their corresponding unphosphorylated proteins. Total liver lysates were immunoprecipitated with IRS1 antibodies, immunoblotted with phosphotyrosine antibodies (4G10 and PY99) then stripped and reprobed for IRS1 to control for loading. C) Bar graphs represent data for pIR (Tyr1162/Tyr1163)/IR, pIRS1 (PY99/4G10)/IRS1, pERK1/2 (Tyr202/Thr204)/ERK1/2, pAKT (Ser473)/AKT, and pSTAT3 (Tyr705)/STAT3 (n=4) as means ± SEM. *p<0.05; **p<0.01 indicate significant difference between insulin-stimulated versus basal. †p<0.05; ††p<0.01 indicate significant differences between shikonin treated versus non-treated mice.

Discussion

The increasing prevalence of obesity and its associated comorbidities including NAFLD and type 2 diabetes demands effective therapeutic interventions. Shikonin has long been used in traditional herbal medicine and is reported to have beneficial properties such as anti-inflammatory, anti-cancer and anti-microbial effects. In this study, we report the effects of shikonin on metabolic regulation in vivo. Shikonin treatment improved systemic glucose tolerance in mice fed regular chow and HFD. Moreover, shikonin treated mice fed HFD gained less weight than controls and shikonin mitigated HFD-induced metabolic damage. At the molecular level, shikonin treated mice displayed increased hepatic insulin signaling. Together, these studies identify shikonin as a regulator of glucose tolerance and adiposity in vivo and suggest that shikonin treatment may confer some protection against development of HFD-induced metabolic damage.

Shikonin improved glucose homeostasis and enhanced glucose tolerance in mice fed regular chow and HFD. The enhanced glucose tolerance in shikonin treated mice is a primary effect and not secondary to body weight since it was observed in mice fed regular chow in absence of significant changes in body mass and adiposity. These findings are in line with a previous report demonstrating improved fed glucose levels and insulin sensitivity in shikonin treated diabetic Goto-Kakizaki rats23. Consistent with their improved glucose tolerance shikonin treated mice exhibited decreased Pepck and G6pase expression and improved hepatic insulin signaling. Together, these findings suggest that the liver is a contributor to the actions of shikonin in regulating glucose homeostasis. However, the contribution of additional tissue(s) such as the pancreas to enhanced glucose tolerance in shikonin treated mice cannot be ruled out and the effect of shikonin on basal and glucose-stimulated insulin secretion warrants additional investigation.

Shikonin mitigated HFD-induced body weight gain in mice. Shikonin treated mice exhibited significant changes in body mass and adiposity relative to untreated mice as evidenced by reduction in white fat depots. These findings are in line with previous studies that demonstrate inhibition of adipogenesis in 3T3-L1 adipocytes by shikonin24–26. However, the physiological basis for decreased weight gain in shikonin treated mice fed HFD is currently unclear. Conceivably, shikonin may regulate adiposity by modulating energy intake and/or energy expenditure. The current data indicate that shikonin treated mice exhibit comparable energy intake to controls. Shikonin could regulate energy expenditure by increasing uncoupling protein expression and β-oxidation in brown adipose tissue and skeletal muscle and/or enhancing “browning” of the white adipose tissue30, 31. Indeed, preliminary studies indicate increased expression of markers of brown fat in subcutaneous adipose tissue of shikonin treated mice compared with controls (unpublished data).

Shikonin mitigated HFD-induced hepatic damage and dyslipidemia in mice. Shikonin treated mice exhibited decreased HFD-induced hepatic dyslipidemia as evidenced by decreased hepatic TGs and lipid accumulation. This is in line with decreased mRNA of lipogenic genes and increased mRNA of genes implicated in fatty acid oxidation, lipolysis and VLDL secretion (Fig. 5C) in shikonin treated mice compared with controls. It is worth noting that hepatic STAT3 activation can attenuate lipogenesis through suppression of SBREP1c promoter activity and decreasing SREBP1c protein expression32, in line with the current findings from shikonin treated mice. On the other hand, shikonin treated mice exhibited elevated serum TG concentrations suggesting a potentially disadvantageous metabolic effect of shikonin. Preliminary studies indicate activation of hormone sensitive lipase and adipose triacylglycerol lipase in adipose tissue of shikonin treated mice (unpublished data) suggesting increased lipolysis that may contribute to the elevated serum TG concentrations. Together, these results identify shikonin as a potential new regulator of HFD-induced weight gain and hepatic dyslipidemia.

The tissues and molecular mechanisms mediating the metabolic effects of shikonin remain to be determined. Hitherto, the bioavailability and turnover time of shikonin are not known. To address this issue, we developed a highly sensitive ultraperformance liquid chromatography (UPLC)-tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) based method to profile shikonin in various bio-specimens from control and shikonin treated mice. Preliminary UPLC-MS/MS analysis shows presence of shikonin in the pancreas and epididymal adipose tissue of treated mice (but not in liver, serum or muscle) at time of sacrifice (unpublished data). Additional studies are warranted to evaluate the temporal bioavailability of shikonin during various interventions. At the molecular level, shikonin may modulate several targets that have been implicated in metabolic regulation such as protein-tyrosine phosphatases (PTPs) and PKM2. Shikonin stimulates glucose uptake in 3T3-L1 adipocytes through inhibiting PTEN and PTP1B21, 22. PTP1B is an established metabolic regulator in mammals and a pharmacological target for obesity and type 2 diabetes (reviewed in33), and PTEN has been implicated in regulating brown adipose tissue function and energy expenditure34. In addition, shikonin may regulate other PTPs such as Src homology phosphatase 2 (Shp2). Hepatic Shp2 deficiency leads to decreased weight gain and liver steatosis and increased hepatic STAT3 phosphorylation35 as observed with shikonin-treated mice. Moreover, shikonin is a potent inhibitor of PKM218 and protects mice from lethal endotoxemia and sepsis17. The role of PKM2 in metabolic regulation remains to be established but PKM2 phosphorylation and activation in adipose tissue correlates with glucose intolerance and insulin resistance36.

In summary, the current data establish shikonin as a potential novel regulator of glucose homeostasis and adiposity. While additional studies are required to delineate the long term effects of shikonin treatment and the underlying molecular mechanisms, these findings suggest that shikonin may be of potential use in management of disorders associated with the metabolic syndrome.

What is already known about this subject?

Shikonin exhibits anti-inflammatory, anti-cancer and anti-microbial effects

Shikonin stimulates glucose uptake in adipocytes

Shikonin inhibits adipogenesis in adipocytes

What does this study add?

Shikonin treated mice exhibit improved glucose tolerance when fed regular chow.

Shikonin treated mice fed high fat diet (HFD) displayed decreased weight gain and resistance to FD-induced glucose intolerance.

Shikonin treatment decreased HFD-induced hepatic dyslipidemia in mice

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by research grants from NIH R01DK090492 and R01DK095359 to F.G.H. and K99DK100736 to A.B.

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest

Author contributions: AB and FGH conceived the experiments. AB, EH, HK and NG carried out experiments and analyzed data. All authors were involved in writing the paper and had final approval of the submitted and published versions.

References

- 1.Spiegelman BM, Flier JS. Obesity and the regulation of energy balance. Cell. 2001;104:531–543. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00240-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mensah GA, Mokdad AH, Ford E, et al. Obesity, metabolic syndrome, and type 2 diabetes: emerging epidemics and their cardiovascular implications. Cardiol Clin. 2004;22:485–504. doi: 10.1016/j.ccl.2004.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mann JI. Diet and risk of coronary heart disease and type 2 diabetes. Lancet. 2002;360:783–789. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)09901-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Biddinger SB, Kahn CR. From mice to men: insights into the insulin resistance syndromes. Annual review of physiology. 2006;68:123–158. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.68.040104.124723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taniguchi CM, Emanuelli B, Kahn CR. Critical nodes in signalling pathways: insights into insulin action. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:85–96. doi: 10.1038/nrm1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen X, Yang L, Oppenheim JJ, Howard MZ. Cellular pharmacology studies of shikonin derivatives. Phytotherapy research : PTR. 2002;16:199–209. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang WJ, Bai JY, Liu DP, Xue LM, Zhu XY. The antiinflammatory activity of shikonin and its inhibitory effect on leukotriene B4 biosynthesis. Acta pharmaceutica Sinica. 1994;29:161–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kundakovic T, Fokialakis N, Dobric S, et al. Evaluation of the anti-inflammatory and cytotoxic activities of naphthazarine derivatives from Onosma leptantha. Phytomedicine : international journal of phytotherapy and phytopharmacology. 2006;13:290–294. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2004.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singh B, Sahu PM, Lohiya RK, Sharma MK, Singh HL, Singh S. Anti-inflammatory activity of alkanoids and triterpenoids from Trichodesma amplexicaule Roth. Phytomedicine : international journal of phytotherapy and phytopharmacology. 2006;13:152–156. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2004.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Staniforth V, Wang SY, Shyur LF, Yang NS. Shikonins, phytocompounds from Lithospermum erythrorhizon, inhibit the transcriptional activation of human tumor necrosis factor alpha promoter in vivo. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2004;279:5877–5885. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309185200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang H, Zhou P, Huang H, et al. Shikonin exerts antitumor activity via proteasome inhibition and cell death induction in vitro and in vivo. International journal of cancer. Journal international du cancer. 2009;124:2450–2459. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang JP, Raung SL, Chang LC, Kuo SC. Inhibition of hind-paw edema and cutaneous vascular plasma extravasation in mice by acetylshikonin. European journal of pharmacology. 1995;272:87–95. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(94)00627-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang JP, Kuo SC. Impairment of phosphatidylinositol signaling in acetylshikonin-treated neutrophils. Biochemical pharmacology. 1997;53:1173–1177. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(97)00098-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen X, Oppenheim J, Howard OM. Shikonin, a component of antiinflammatory Chinese herbal medicine, selectively blocks chemokine binding to CC chemokine receptor-1. International immunopharmacology. 2001;1:229–236. doi: 10.1016/s1567-5769(00)00033-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Subbaramaiah K, Bulic P, Lin Y, Dannenberg AJ, Pasco DS. Development and use of a gene promoter-based screen to identify novel inhibitors of cyclooxygenase-2 transcription. Journal of biomolecular screening. 2001;6:101–110. doi: 10.1177/108705710100600206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lu L, Qin A, Huang H, et al. Shikonin extracted from medicinal Chinese herbs exerts anti-inflammatory effect via proteasome inhibition. European journal of pharmacology. 2011;658:242–247. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2011.02.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang L, Xie M, Yang M, et al. PKM2 regulates the Warburg effect and promotes HMGB1 release in sepsis. Nature communications. 2014;5:4436. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen J, Xie J, Jiang Z, Wang B, Wang Y, Hu X. Shikonin and its analogs inhibit cancer cell glycolysis by targeting tumor pyruvate kinase-M2. Oncogene. 2011;30:4297–4306. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang FL, Wang P, Liu YH, et al. Topoisomerase I inhibitors, shikonin and topotecan, inhibit growth and induce apoptosis of glioma cells and glioma stem cells. PloS one. 2013;8:e81815. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0081815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Andujar I, Recio MC, Giner RM, Rios JL. Traditional chinese medicine remedy to jury: the pharmacological basis for the use of shikonin as an anticancer therapy. Current medicinal chemistry. 2013;20:2892–2898. doi: 10.2174/09298673113209990008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kamei R, Kitagawa Y, Kadokura M, et al. Shikonin stimulates glucose uptake in 3T3-L1 adipocytes via an insulin-independent tyrosine kinase pathway. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2002;292:642–651. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2002.6714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nigorikawa K, Yoshikawa K, Sasaki T, et al. A naphthoquinone derivative, shikonin, has insulin-like actions by inhibiting both phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome 10 and tyrosine phosphatases. Molecular pharmacology. 2006;70:1143–1149. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.025809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oberg AI, Yassin K, Csikasz RI, et al. Shikonin increases glucose uptake in skeletal muscle cells and improves plasma glucose levels in diabetic Goto-Kakizaki rats. PloS one. 2011;6:e22510. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee H, Kang R, Yoon Y. Shikonin inhibits fat accumulation in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Phytotherapy research : PTR. 2010;24:344–351. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee H, Bae S, Kim K, et al. Shikonin inhibits adipogenesis by modulation of the WNT/beta-catenin pathway. Life sciences. 2011;88:294–301. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2010.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gwon SY, Ahn JY, Jung CH, Moon BK, Ha TY. Shikonin suppresses ERK 1/2 phosphorylation during the early stages of adipocyte differentiation in 3T3-L1 cells. BMC complementary and alternative medicine. 2013;13:207. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-13-207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xiong W, Luo G, Zhou L, Zeng Y, Yang W. In vitro and in vivo antitumor effects of acetylshikonin isolated from Arnebia euchroma (Royle) Johnst (Ruanzicao) cell suspension cultures. Chinese medicine. 2009;4:14. doi: 10.1186/1749-8546-4-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alikhani N, Ferguson RD, Novosyadlyy R, et al. Mammary tumor growth and pulmonary metastasis are enhanced in a hyperlipidemic mouse model. Oncogene. 2013;32:961–967. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Perlemuter G, Bigorgne A, Cassard-Doulcier AM, Naveau S. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: from pathogenesis to patient care. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab. 2007;3:458–469. doi: 10.1038/ncpendmet0505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cannon B, Nedergaard J. Brown adipose tissue: function and physiological significance. Physiological reviews. 2004;84:277–359. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00015.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rasmussen BB, Wolfe RR. Regulation of fatty acid oxidation in skeletal muscle. Annual review of nutrition. 1999;19:463–484. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.19.1.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ueki K, Kondo T, Tseng YH, Kahn CR. Central role of suppressors of cytokine signaling proteins in hepatic steatosis, insulin resistance, and the metabolic syndrome in the mouse. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101:10422–10427. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402511101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bakke J, Haj FG. Protein-tyrosine phosphatase 1B substrates and metabolic regulation. Seminars in cell & developmental biology. 2015;37C:58–65. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2014.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ortega-Molina A, Efeyan A, Lopez-Guadamillas E, et al. Pten positively regulates brown adipose function, energy expenditure, and longevity. Cell metabolism. 2012;15:382–394. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nagata N, Matsuo K, Bettaieb A, et al. Hepatic Src homology phosphatase 2 regulates energy balance in mice. Endocrinology. 2012;153:3158–3169. doi: 10.1210/en.2012-1406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bettaieb A, Bakke J, Nagata N, et al. Protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B regulates pyruvate kinase M2 tyrosine phosphorylation. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2013;288:17360–17371. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.441469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]