Abstract

The ocean continues to provide a plethora of unique scaffolds capable of remarkable biological applications. A large number of pyrroloiminoquinone alkaloids, including discorhabdins, epinardins, batzellines, makaluvamines, and veiutamine have already been isolated from marine organisms. A class of pyrroloiminoquinone-related alkaloids known as bispyrroloquinones is the focus of this review. This family of marine alkaloids, which contain an aryl substituted bispyrroloquinone ring system, includes three subclasses of alkaloids namely, wakayin, tsitsikammamines A-B and zyzzyanones A-D. Both wakayin and the tsitsikammamines contain a tetracyclic fused bispyrroloiminoquinone ring system, while zyzzyanones contain a fused tricyclic bispyrroloquinone ring system.

The unique chemical structures of these marine natural products and their diverse biological properties, including antifungal and antimicrobial activity, as well as the potent, albeit generally nonspecific and universal cytotoxicities, have attracted great interest of synthetic chemists over the past three decades. Tsitsikammamines, wakayin, and several of their analogues show inhibition of topoisomerases. One additional possible mechanism of anticancer activity of tsitsikammamines analogues that was discovered recently is through the inhibition of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase, an enzyme involved in tumoral immune resistance. This review discusses the isolation, synthesis, and bioactivities of bispyrroloquinone alkaloids and their analogues.

Keywords: Bispyrroloquinones, tsitsikammamines, wakayin, zyzzyanones, topoisomerase, anticancer and antimicrobial

1. Introduction

Since the olden ages, humanity has relied on nature to provide therapeutics for a plethora of deadly diseases [1]. Nearly fifty percent of new drugs introduced in the past four decades have been natural products, their mimics, or their synthetic derivatives [2]. Of these compounds, those that are derived from marine sources are believed to be superior to terrestrial natural products in terms of their chemical novelty and their ability to induce potent bioactivities. A contributing factor for this observation stems from the fact that greater than 70% of earth's surface is covered by oceans and thus marine ecosystems exhibit a higher biological diversity [3-6]. Moreover, the sedentary lifestyle adopted by majority of the marine organisms has necessitated the evolution of highly efficient chemical agents for their defense mechanisms.

These chemical substances, which are produced within their system, are called ‘marine natural products.’ Usually existing as secondary metabolites in marine invertebrates such as sponges, bryozoans, tunicates, and ascidians, marine natural products help these organisms by deterring their predators or paralyzing their prey [7, 8]. Upon the release of these compounds into their surroundings, they are usually rapidly diluted by water. Hence, in order to be effective against their predators or prey, the compounds need to exhibit high potency. For this reason, marine natural products usually demonstrate extremely potent biological activities and continue to be a rich source of a vast array of such medicinally valuable compounds [7, 9-13]

As a result of the potential for new drug discovery scaffolds, marine natural products have attracted the attention of scientists from various disciplines, including organic chemistry, bioorganic chemistry, medicinal chemistry, pharmacology, and biology. With the improvement in the deep-sea sample collection technology and the large scale drug production through aqua culture, there has been an increase in the number of biologically active natural products isolated from marine sources in the last decade [14].

1.a. Marine derived drugs

More than a dozen of these marine alkaloids are currently undergoing various phases of human clinical trials for treatment of different types of cancers. Compounds such as trabectedin, bryostatins, plitidepsin, and eribulin shown in Fig. 1 capture the pharmacological value of marine natural products.

Figure 1. Marine derived drugs.

Trabectedin (ET-743, Yondelis®) was originally isolated from the Caribbean sea squirt, Ecteinascidia turbinate. It is the first anticancer marine-derived drug that was approved by the European Union for the treatment of patients with advanced soft tissue sarcoma after failure of anthracyclines and ifosfamide. Trabectedin is also in phase II trials for prostate, breast and pediatric cancer [15-17].

Bryostatins represent an important group of pharmaceutically promising substances that are produced by commensal microorganisms naturally occurring in marine invertebrates [18]. So far, twenty bryostatins have been discovered, which elicit a remarkable range of biological activities, including antineoplastic activity, synergistic chemotherapeutic activity, and cognition memory enhancement [19]. The most extensively studied compound, bryostatin 1, selectively modulates the function of various individual protein kinase C isozymes. It has been proposed for phase I and phase II clinical trials for the treatment against Alzheimer's disease [18, 20, 21].

Similarly, plitidepsin was originally isolated from the marine tunicate Plitidepsin. This compound exhibits antitumor, antiviral, and immunosuppressive activities and has especially shown promise in shrinking tumors in pancreatic, stomach, bladder, and prostate cancers [22]. It was granted orphan drug status by the European Medicines Agency for treating acute lymphoblastic leukemia. It is currently in phase II clinical trials for solid and hematological malignant neoplasias like T cell lymphoma and in phase III clinical trials for multiple myeloma [23].

Finally, eribulin is U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved anticancer drug under the trade name halaven, which is used to treat patients with metastatic breast cancer who have received at least two prior chemotherapy regimens for late-stage disease [24, 25]. Eribulin is also being investigated by Eisai Co. for use in a variety of other solid tumors, including non-small cell lung cancer, prostate cancer and sarcoma.

1.b. Marine Sponges

Of the various sources of marine natural products, marine sponges are a particularly fertile field for the discovery of bioactive scaffolds. Several reviews concerning the sponge-derived bioactive marine alkaloids with future pharmaceutical applications have been published in the last decades [3, 26-31]. Sponges produce a plethora of chemical compounds with widely varying carbon skeletons. Most bioactive compounds from sponges which have been isolated in sufficient quantities exhibited a variety of activities such as anti-inflammatory, antitumor, immunosuppressive, neurosuppressive, antiviral, antimalarial, and antibiotic activities [1, 26, 27, 32, 33]. Unfortunately, many alkaloids with unique structures are available only in minute quantities, precluding their thorough biological evaluations. The only practical way to access these alkaloids and their analogues in larger quantities is through synthetic means.

Marine sponges of the genera Latrunculia, Batzella, Prianos and Zyzzya are a rich source of alkaloids bearing a pyrroloiminoquinone ring system [29, 34]. This series of alkaloids comprise of more than 60 metabolites including discorhabdins [35], epinardins [36], batzellines [37], isobatzellines [37], makaluvamines [33, 38-42], and veiutamine [43]. These alkaloids have shown a variety of biological activities such as inhibition of topoisomerase I [38] and II, [33] cytotoxicity against different tumor cell lines, [33, 44] antifungal [38] and antimicrobial activities [32].

A related family of marine alkaloids containing an aryl substituted bispyrroloquinone ring system is of considerable significance to both organic chemists and biologists. This class includes three subclasses of alkaloids wakayin, tsitsikammamines A-B, and zyzzyanones A-D (Fig. 2). Both wakayin and the tsitsikammamines contain a tetracyclic fused bispyrroloiminoquinone ring system and while zyzzyanones contains a fused tricyclic bispyrroloquinone ring system.

Figure 2. Representative bispyrroloquinone alkaloids isolated from marine sources.

The potent bioactivities resulting from these unique ring structures have made them attractive targets for organic synthesis and drug discovery. However, the bioactivities of these compounds are yet to be tapped for medicinal applications. One of the reasons for this slow progress in the development of this class of compounds is the lack of good synthetic methods to make these compounds and their analogues in large scale. Recently, there has been a rapid growth of interest in the synthesis and biological evaluation of this class of compounds and their analogues. Quite a few syntheses and synthetic approaches have been reported for this class of compounds. This review focuses on the isolation, characterization, synthesis and biological activities of wakayin, tsitsikammamines, and zyzzyanones and their analogues.

2. Isolation

Many industrial and academic groups are accessing marine environments using advanced technology platforms. Liquid-solid chromatographic techniques such as HPLC or partition chromatographic methods are still the major tools for isolating pure compounds. A summary of bispyrroloquinone alkaloids, and the years of their isolation can be found below in Table 1.

Table 1. Source and year of discovery of Bispyrroloquinone alkaloids.

| Natural product | Year | Marine source | Locality | Authors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wakayin | 1991 | Ascidia clavelina | N/A | Ireland et al |

| Tsitsikammamines A & B | 1996 | Tsitsikamma favus | Algoa Bay, South Africa | Coetzee and Davies-Coleman et al |

| N-18oxime tsitsikammamines analogue | 2004 | Tsitsikamma favus | Southeastern coast of South Africa | Davies-Coleman et al |

| Zyzzyanone A | 2004 | Zyzzya fuliginosa | Australia | Utkina et al |

| Zyzzyanone B-D | 2005 | Zyzzya fuliginosa | Australia | Utkina et al |

2.a. Wakayin

Wakayin (2) is the first pyrroloiminoquinone alkaloid that was isolated from the ascidian Clavelina species, reported by Ireland and Copp's group in 1991 [49].. This was the first indication that pyrroloiminoquinone metabolites are not confined to marine sponges, tentatively suggesting a possible symbiont source for these bispyrroloiminoquinone metabolites. The MeOH-CHCl3 extract of the ascidian was crudely partitioned by reverse phase flash chromatography using MeOH-aqueous trifluoroacetic acid solvent mixtures. Biologically active fractions were combined and purified by repeated elution through sephadex LH-20 affording the respective compound as a dark blue trifluoroacetate salt (0.005% wet weight). Structure elucidation of wakayin employed HRFABMS, UV analysis, and DQCOSY, HMQC, and HMBC NMR.

2.b. Tsitsikammamines A-B

In 1996, two bispyrroloiminoquinone alkaloids were isolated from a sponge collected from the Tsitsikamma Marine Reserve, South Africa. Coetzee et al [45] performed the initial separation of the alkaloids from a MeOH : CHCl3 extract using a -18 Sep-Pak cartridge with a solvent elution gradient from water to MeOH. Further chromatography of the mixture on a variety of reverse phase HPLC columns, relying on a combination of antibiotic bioassays and 1H NMR spectroscopy yielded tsitsikammamine A (1a, 0.04%) and tsitsikammamine B (1b, 0.045%) as dark green oils. Structure elucidation of these compounds employed 1H-1H COSY NMR, UV analysis, and HRFABMS. These structural compositions incorporated features of both the discorhabdins and makaluvamines. Years later in 2004, their corresponding N-18 oxime derivatives were obtained from T. favus [46]. Natural products containing either N-oxide or oxime moieties are rare in the marine environment. The reverse phase HPLC purification of these analogues required aqueous MeOH eluents containing 0.05% trifluoroacetic acid. Compounds (1c) and (1d) are considered to be isolation artifacts of the naturally occurring N-oxides of tsitsikammamines A and B.

2.c. Zyzzyanones A-D

Zyzzyanone A (3a), a bispyrroloquinone, was isolated along with a few makaluvamines and damirones from the Australian marine sponge Z. fuliginosa by Utkina's group in 2004 [47] . Often, this compound is referred as a biosynthetic seco-analogue of tsitsikammamines and is the first representative of a new class of marine alkaloids containing a pyrrolo[3,2-f]indol-4,8(1H,7H)-dione skeleton. Briefly, the freeze-dried sponge (125 g) was extracted with 50% EtOH at room temperature. The extract was concentrated under reduced pressure to yield a dark red residue. This residue was subjected to column chromatography on a Polychrome-1 (powder Teflon) column with a solvent elution gradient from water to EtOH. A brownish-green fraction eluted with 50% EtOH was chromatographed on a Sephadex LH-20 column using CHCl3–EtOH–TFA (3:1:0.1%) to yield zyzzyanone A (0.006% on the dry weight of the sponge). Zyzzyanone A can be seen to have a plausible interrelationship with the makaluvamines and with the tsitsikammamines.

One year later, continuous investigation on the same sponge in an effort to obtain more zyzzyanone A, the same group isolated three new minor bispyrroloquinones: zyzzyanone B (3b), an N1-demethyl analogue of zyzzyanone A; zyzzyanone C (3c), an N11-formyl analogue of zyzzyanone A; and zyzzyanone D (3d), an N11- formyl analogue of zyzzyanone B [48]. These scaffolds can also be seen to have a plausible interrelationship with the makaluvamines and with the tsitsikammamines.

3. Synthetic studies

A diverse library of bispyrroloquinone containing scaffolds is required for the understanding of the mechanism of bispyrroloquinone's biological activities. This opportunity has attracted synthetic chemists over the last few decades. Table 2 and the subsequent sections below summarize the striking work on the synthesis of wakayin, tsitsikammamines, zyzzyanones and their related compounds.

Table 2. Summary of synthesis of bispyrroloquinone natural products and their analogues.

| Author | Year | Description of synthetic contribution | Scheme | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cava et al | 1998 | Model reaction: oxidative formation of pyrrole ring of wakayin | 1 | [49] |

| Barret et al | 1999 | Bispyrroloquinone ring system of wakayin | 2 | [50] |

| Delfourne et al | 2006 | Several pyrazolic analouges of wakayin and tsitsikammamine | 3,4 | [51] |

| Skibbo et al | 2008 | Diimidazole structural analogues of wakayin | 5 | [52] |

| Besson et al | 2000 | Open analogues of wakayin | 6 | [53] |

| Delfourne et al | 2009 | Total synthesis of tsitsikammamine A-B | 7,8 | [54] |

| Delfourne et al | 2006 | Aza analogues of wakayin and tsitsikammamine | 9 | [55] |

| Velu et al | 2013 | Total synthesis of Zyzzyanones A-D | 10-13 | [56] |

3.a. Synthesis of wakayin and its analogues

3.a.i. Oxidative formation of the pyrrole ring D of wakayin

Owing to its unique structure and potent antitumor activities, wakayin became an interesting target for the synthetic studies since its first report of isolation in 1991. The synthetic attempts have turned out to be quite challenging because of its highly hindered fused ring structure. So far, no successful synthesis of wakayin has been reported in the literature. However, synthetic attempts and synthesis of different analogues of wakayin have been reported. Cava et al reported the first attempt at the synthesis of wakayin analogues in 1998 [49] which describes a model reaction of oxidative formation of the critical pyrrole ring D of wakayin as shown in Scheme 1. The N-methyltryptamine (4) was reacted with 2-methoxynaphthoquinone (5) in refluxing EtOH to afford 2-(indol-3-ylethylamino)-naphthoquinone (6) in 91% yield. Further, oxidation of compound 6 using DDQ in HOAc afforded the desired model compound 7 in 78% yield.

Scheme 1. Oxidative formation of the pyrrole ring D of wakayin.

3.a.ii. Formation of bispyrroloquinone ring system of wakayin

The second attempt at the synthesis of bispyrroloquinone ring system present in wakayin was reported by Barret et al in 1999 [50]. Bispyrroloquinone ring system was constructed in a single step starting from oxotryptamine (8) and N-tosylindole-4,7-quinone (9) as shown in Scheme 2. Addition of indole-4,7-quinone to the alcoholic solution of compound 8 goes through amination and oxidation to afford the intermediate 10 which then cyclizes to afford a single regioisomer of the compound 11. Tosyl group present in the compound 11 was removed by hydrolysis using NaOH in MeOH to afford compound 12.

Scheme 2. Formation of bispyrroloquinone ring system of wakayin.

3.a.iii. Pyrazolic analogues of wakayin

In 2006, Delfourne et al synthesized several analogues of wakayin and tsitsikammamines in which one of the two pyrrole rings was replaced with a pyrazole ring [51]. A novel synthetic strategy was employed for making these analogues, which involved [3 + 2] cycloaddition of 3-ethylamine-indole-4,7-dione derivative (19) with different substituted diazo compounds. The quinone 19 was synthesized as shown in Scheme 3. The synthesis started with 4,7-dimethoxyindole (13), which in turn was prepared from 2,5-dimethoxybenzaldehyde according to a five-step procedure previously published [57]. Compound 13 was formylated using POCl3 in DMF to afford dimethoxyindole-3-carboxaldehyde 14. The Henry reaction of 14, by treatment with CH3NO2 in the presence of NH4OAc in HOAc, afforded the nitro compound 15. The indole nitrogen of compound 15 was tosylated by treatment with p-toluene sulfonyl chloride in the presence of KOH. The resulting compound 16 was reduced using LiAlH4 to the corresponding amino derivative 17. The side chain amino group of 17 was then protected as the Boc derivative 18 by treatment with NaH and di-tert-butyl dicarbonate in THF. Oxidation of 18 by ceric ammonium nitrate (CAN) gave rise to quinone 19.

Scheme 3. Synthesis of 3-ethylamine-indole- 4,7-dione derivative.

The conversion of the quinone 19 to pyrazolic analogues is outlined in Scheme 4. [3+2] cycloaddition of adequately substituted diazo compounds (20) with the quinone 19 in THF gave two regioisomeric products 21a-c and 24a-c. Boc group deprotection of the side chain amino group using TFA in CH2Cl2 gave the corresponding amines as trifluoroacetate salts in good yields. Further, refluxing in EtOH in the presence of both 4 A° molecular sieves and NaHCO3 afforded the cyclized compounds 22a-c and 25a-c. Finally, removal of tosyl group was performed using NaOH in dioxane to afford the pyrazolic analogues 23a-c and 26a-c.

Scheme 4. Synthesis of pyrazolic analogues of wakayin.

3.a.iv. Diimidazole analogues of wakayin

In 2008, Skibbo et al succeeded in preparing the previously unreported diimidazolo[1,5,4-de, 1,5,4-h]-quinoxaline ring system as a structural analogue of wakayin. This synthesis permits the convenient incorporation of various R groups for the analogue development. The synthesis of diimidazole analogues is described in the Scheme 5. The first part of the synthesis is the preparation of the key intermediate 30 from which various substituted analogues were made. The synthesis started with the nitration of m-chlorophenol followed by methylation of the phenolic OH to yield 3-chloro-4-nitroanisole 27 [52]. Treatment of compound 27 with ethanolamine resulted in nucleophilic aromatic substitution to afford compound 28. Catalytic reduction of 28 resulted in an ortho diamine that was immediately treated with HOAc to afford the Phillips cyclization product, 29. O-Acetylation of compound 29 followed by nitration using fuming HNO3 afforded the compound 30.

Scheme 5. Synthesis of diimidazole analogues of wakayin.

Treatment of 30 with various primary alkyl amines in DMF resulted in nucleophilic aromatic substitution of the methoxy group along with deacetylation to afford the compounds 31a-d. The alcoholic group in 31a-d was converted to corresponding mesylates 32a-d by treatment with MsCl and pyridine. Compounds 32a-d were then converted to the tetrahydroquinoxoline intermediates 33a-d by catalytic reduction of the nitro group followed by internal nucleophilic displacement of mesylate. As these cyclization products are electron rich and susceptible to aerobic oxidation, 33a-d were immediately cyclized to 34a-d in the presence of acetic anhydride and HBr. Oxidation of compounds 34a-d using Fremy's salt afforded the final products 35a-d as orange yellow solids.

3.a.v. Open analogues of wakayin

Open analogues of wakayin were synthesized by Besson et al in 2000 [53] using a previously reported tricyclic pyrroloiminoquinone derivative 44 [58]. This synthesis used a quinoline derivative, 6,7-Dimethoxy-4-methylquinoline (38) as the starting material, which in turn was prepared by the reaction between 3,4-dimethoxyaniline (36) and methyl vinyl ketone (37) in refluxing HOAc in the presence of FeCl3. Nitration of 38 led to the 5- nitro compound 39 in a good yield. Oxidation of the methyl group of 39 to aldehyde by Vismara's method was achieved by treatment with iodine, TFA, tert-butyl iodide and FeCl2 in DMSO to obtain the compound 40.

The aldehyde group in compound 40 was then protected as a dimethyl acetal to give 41. The pyridine ring and the nitro group were simultaneously reduced by an excess of NaBH4 in MeOH with NiCl2 to afford diamine 42 in a very good yield. Heating of compound 42 at 80°C in aqueous HCl and THF led to the cyclization of pyrrole ring resulting in compound 43. Amino indole 43 was treated with CAN in aqueous acetonitrile to generate the quinone 44. C-7 methoxy group present in compound 44 was substituted with various amines in situ, without isolating the intermediate to afford the open chain analogues of wakayin 45a-e.

3.b. Synthesis of tsitsikammamine and its analogues

3.b.i. Synthesis of tsitsikammamine A

A concise route to the marine bispyrroloiminoquinone alkaloid tsitsikammamine A (1a) and its regioisomeric analogue (58) was developed by Delfourne et al in 2009 as outlined in Scheme 7. Reaction of compound 46 with indole-4,7-quinone derivative 47 in absolute EtOH gave two regioisomeric aminated products, 48 and 49. The formation of the second five-membered nitrogen ring in 48 was achieved by direct cyclization in TFA and CH2Cl2, and was concomitant with the cleavage of the Boc protecting group to give compound 50. MnO2 oxidation of compound 50 gave the bispyrroloquinone derivative 51, which was subsequently cyclized into the corresponding iminoquinone 52. The tosyl group of 52 was then removed by a reaction with 1N NaOH in dioxane followed by demethylation using BBr3 affording tsitsikammamine A (1a).

Scheme 7. Synthesis of tsitsikammamine A.

Following same set of synthetic reactions the same paper converted compound 49 to a regioisomeric analogue (58) of tsitsikammamine A as shown in Scheme 8.

Scheme 8. Synthesis of regioisomer of tsitsikammamine A.

3.b.ii. Aza analogues of wakayin and tsitsikammamines

Two classes of aza analogues of tsitsikammamines have been synthesized [55]. The strategy used was based on the 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition reaction between indole 4,7-dione and a diazoaminopropane derivative. The cycloaddition reaction involving N-tosylindole-4,7-dione (59) and diazo-Moz-aminopropane (60) gave a mixture of two regioisomers 61a/b. The mixture of cycloadducts 61a/b was tosylated prior to the cleavage of the Moz protecting group to give compounds 62a/b. The Moz-protective group in 62a/b was cleaved quantitatively by TFA in the presence of m-cresol to give the corresponding salts 63a/b, which were cyclized into the tetracyclic derivatives 64a/b as a mixture using 4Å molecular sieves in EtOH. Compounds 64a and 64b were then separated by flash chromatography. Finally, the two tosyl groups present in 64a and 64b were cleaved by treatment with NaOH in dioxane to afford the target aza analogues 65a and 65b.

3.c. Synthesis of zyzzyanones

3.c.i. Zyzzyanone A

The first total synthesis reported for zyzzyanones A-D was published by the Velu group in 2013 [56]. Scheme 10 outlines the synthesis of zyzzyanone A (3a), which begins with the previously known [59] N-tosyl-6-(methoxy)-1H-indole-4,7-dione derivative containing a (N-Boc)ethyl amine side chain (66).

Scheme 10. Synthesis of zyzzyanone A.

Addition of benzyl amine to 66 in a mixture of MeOH and THF (1:1) at room temperature produced the aminated compound 67 with a 78 % yield. Next, in the presence of Mn(OAc)3 in acetonitrile at 80°C, treatment of benzyloxyphenyl acetaldehyde diethyl acetal (68) resulted in the formation of bispyrroloquinone derivative 69 in 72 % yield. Methylation of compound 69 was carried out using MeI in the presence of NaH in anhydrous DMF at room temperature. The expected monomethylated compound 70, along with the unexpected dimethylated compound 71 was produced in 46 % and 34 % yields. Compound 71 is presumably formed by the removal of N-tosyl group from 70 followed by a second N-methylation, both steps occurring in the same reaction. Debenzylation of compound 71 was carried out with Pd black in the presence of HCOONH4 in anhydrous EtOH to afford compound 72 in 55 % yield. Finally, removal of the N-Boc group present in compound 72 was carried out through the use of TFA in CH2Cl2 to afford zyzzyanone A (3a) as a TFA salt in 81 % yield.

3.c.ii. Zyzzyanone B

The synthesis of zyzzyanone B (3b) is outlined in Scheme 11. To begin, detosylation of 70 by treatment with NaN3 in anhydrous DMF for 4 hours resulted in compound 73 with a 75 % yield. Next, debenzylation occurred using Pd black in the presence of HCOONH4 in anhydrous EtOH, which resulted in the removal of both O- and N- benzyl groups to afford compound 74 in 53 % yield. Removal of the Boc group from compound 74 using 1:1 mixture of TFA and CH2Cl2 at room temperature resulted in the formation of zyzzyanone B (3b) as a TFA salt in 85 % yield.

Scheme 11. Synthesis of zyzzyanone B.

3.c.iii. Zyzzyanone C

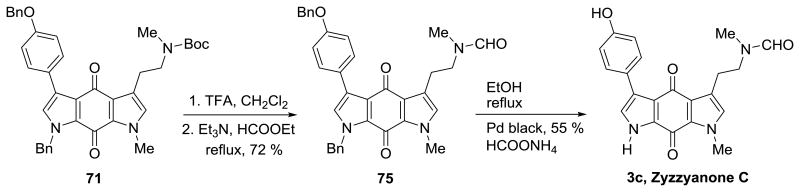

Zyzzyanone C (3c) was synthesized as outlined in Scheme 12. Removal of the Boc group from compound 71 and immediate formylation of the crude product using HCOOEt and Et3N at reflux conditions produced the N-formylated intermediate 75 in 72 % yield. Next, Pd black was used to cleave both O- and N- benzyl groups present in compound 75 in the presence of HCOONH4 in refluxing EtOH to afford zyzzyanone C (3c) in 55 % yield.

Scheme 12. Synthesis of zyzzyanone C.

3.c.iv. Zyzzyanone D

Scheme 13 demonstrates the conversion of compound 72 to zyzzyanone D (3d). 1:1 mixture of TFA and CH2Cl2 was used to remove the Boc group to obtain the amino compound which was immediately subjected to formylation using HCOOEt in the presence of Et3N under reflux conditions to afford compound 76 in 64 % yield. The expected formylation along with detosylation were observed. Both N-benzyl and O-benzyl groups present in compound 76 were removed by treatment with Pd black in the presence of HCOONH4 in EtOH under reflux conditions to afford zyzzyanone D (3d) in 58 % yield.

Scheme 13. Synthesis of zyzzyanone D.

4. Bioactivities

Bispyrroloquinone alkaloids have gained considerable attention within the past two decades not only due to their intriguing structures but also due to their encouraging pharmacological bioactivities, namely their cytotoxicity and antitumor activity.

Novel emerging natural products that show cytotoxicity and antitumor activity are often evaluated for their effects on topoisomerases because they are a viable target for the development of cancer drugs. These enzymes regulate the overwinding or underwinding of supercoiled DNA strands during DNA replication, transcription, and various other stages of normal cellular functioning. The two types, I and II, differ in their structures, mechanisms, and cellular functions. Type I enzyme exists as a monomer and causes transient single strand breaks in duplex DNA whereas the type II isozyme is dimeric and causes cuts in both strands of duplex DNA. In most of the evaluations, the clinical drug camptothecin is often used as a positive control for topoisomerase I inhibition while etoposide is used as a positive control for topoisomerase II inhibition [60-62].

Since marine alkaloids have shown a considerable affinity to both isozymes [42, 46, 63-65], many research groups have evaluated topoisomerase inhibition of wakayin and tsitsikammamine analogues. The sections below will provide a brief summary of the key contributions made in this context as well as other bioactivities reported for wakayin, tsisikammamines, zyzzyanones, and their analogues.

4.a. Biological activities of wakayin and tsisikammamines

In 1991, along with the isolation and structure elucidation of wakayin, Ireland et al also reported its in vitro cytotoxicity against the human colon tumor cell line, HCT116. Antimicrobial activity against Bacillus subtilis MIC 0.3 μg/mL was also observed. Its 3-fold differential toxicity toward the Chinese hamster ovary cell line EM9 (sensitive to DNA damaging genotoxic agents) versus BRI (resistant to carmustine) provided preliminary evidence that wakayin exhibits cytotoxicity by interfering with or damaging DNA. Evaluation of its inhibitory effects on topoisomerase I and II resulted in IC50 values of 10 and 250 μM, respectively. Thus, wakayin is an inhibitor of topoisomerases and is also shown to be a strong DNA binder.

Similarly, along with the details of the isolation of Tsitsikammamines in 1996, Coetzee et al reported both compounds exhibited antimicrobial activity against Bacillus subtilis. Initial preliminary studies have shown that while tsitsikammamines are cytotoxic and exhibit anti-fungal activity, they do not inhibit either topoisomerase I or II. In addition, cell growth inhibitory activities against the HCT-116 cell line were reported to be 1.4 and 2.4 μM for tsitsikammamines A and B, respectively.

Following this, when the novel N-18 oxime analogues of tsitsikammamines A and B were first isolated from T. favus extracts in 2004, Coleman et al compared the in vitro activity of wakayin and all four tsitsikammamines compounds against HCT-116 (Table 5). The N- oxime analogues of tsitsikammamines A and B were shown to be less active compared to the original scaffolds [46].

Table 5. Bioactivity of open analogues of wakayin against L1210.

| Compound ID | Structurea | IC50 (μM) |

|---|---|---|

| 42a |

|

5.3 |

| 42b |

|

0.3 |

| 42c |

|

0.38 |

| 42d |

|

2.1 |

| 42e |

|

0.25 |

a All compounds are isolated as TFA salts.

These four compounds were also evaluated for their topoisomerase inhibition, as a possible target of the observed cytotoxicity. Authors believed that due to the structural homology between wakayin and the tsitsikammamines, tsitsikammamines might exhibit analogous topoisomerase I inhibition and DNA intercalation, even though the preliminary studies in 1996 did not observe topoisomerase inhibition.

Results of their study demonstrated tsitsikammamines to exhibit similar topoisomerase I inhibition to wakayin [66], which required 10-100-fold the molar concentrations that camptothecin requires to elicit DNA cleavage through topoisomerase I inhibition. The micromolar concentration (Ks) of a compound that decreases DNA-bound ethidium bromide fluorescence by 50% is routinely used to quantify DNA intercalation. The strong intercalating ability of wakayin is reflected in a Ks value of 20 μM. Of the four tsitsikammamines, (1a) and its N- oxime (1c) exhibited similar DNA binding to wakayin (2), while (1b) and its N-oxime (1d) displayed a weaker DNA binding in comparison to wakayin.

4.a.i Pyrazolic analogues of wakayin and tsitsikammamine

Encouraged by the results obtained from the natural compounds, pyrazolic analogues of the marine alkaloids wakayin and tsitsikammamines A and B that were synthesized using [3 + 2] cycloaddition reactions (Scheme 4) were evaluated in vitro for antiproliferative activity against five distinct cancer cell lines and for their inhibitory effect on topoisomerases I and II [51]. Only a few of them exhibited cytotoxic activity with IC50 values in the micromolar range. A subset of the compounds showed inhibition of topoisomerase I and/or II catalyzed relaxation of supercoiled DNA at a concentration comparable to the drugs camptothecin and etoposide. Table 4 summarizes the key compounds exhibiting good bioactivities.

Table 4. Bioactivity of pyrazolic analogues of wakayin and tsitsikammamines.

| Compd ID | Structure | Topoisomerase Inhibition (IC50, μM) | Inhibition of Cancer cell proliferation (IC50, μM) or % inhibition @ 10 μM | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| hTopoI | hTopoII | HCT15 | HT29 | PC3 | CT26 | Renca | ||

| 22a |

|

300 | ND | 6.5 | 3.1 | 4.9 | 5.3 | 0.14 |

| 22b |

|

30 | >100 | 0% | 23% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| 25a |

|

>100 | >100 | 5 | 1.9 | 5.8 | 4.9 | 4.6 |

| 25b |

|

10 | 100 | 0% | 41% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| 25c |

|

>100 | ND | 1.6 | 2.9 | 5.2 | 2.9 | 1.9 |

| Etop |

|

ND | 100 | 4.5 | 6.6 | 7.8 | 0.2 | 2.9 |

| Camp |

|

100 | ND | 0.018 | 0.030 | 0.052 | 0.034 | 0.304 |

Etop: etoposide, Camp: camptothecin, ND: not determined.

Compounds 22b and 25b structurally parallel tsitsikammamine A, in which one pyrrole ring is modified to a pyrazole ring. These two most active analogues demonstrated a 3- and 10-fold improved activity in topoisomerase I inhibition respectively. 25b was the sole scaffold to also inhibit human topoisomerase II activity at a concentration comparable to that of the control drug etoposide (100 μM).

Three human cancer cell lines (HCT15 and HT29, colon; PC3, prostate) and two murine cell lines (CT-26, colon; Renca, kidney) were used for further in vitro evaluation of their antiproliferative activities. Compounds 22a, 25a, and 25c demonstrated antiproliferative effect, blockage of cell proliferation in the micromolar range, but these compounds showed no relevant inhibition of topoisomerases. Thus, these analogues use another mechanism for their cytotoxic activity against cancer cells. Despite the promising topoisomerase inhibition observed by 22b and 25b, these scaffolds did not inhibit the cell growth of tested tumoral cell lines. Author hypothesize that this could be a result of poor cell penetration as their log P values of 3.6 show they are fairly lipophilic.

4.a.ii. Diimidazole analogues of wakayin

The four analogues of wakayin based on diimidazo[1,5,4-de, 1,5,4-h]-quinoxaline (35a-d) that were described in Scheme 5 were subjected to an extensive investigation for their cytostatic and cytotoxic activity using a 60 human cancer cell-line panel consisting of the major histological tissue types [52]. The concentrations of drug required for 50% growth inhibition (GI50), total growth inhibition (TGI), and the concentration required for 50% cell death (LC50) were reported for each compound. Results showed that the cyclopropyl derivative 35c was inactive against all cell lines. However, the methyl and phenethyl derivatives, 35a and 35b, displayed a degree of cytostatic activity against some histological cancer types. Compounds 35a and 35b were most active against the ovarian and melanoma cancer panels, respectively. However, 35d performed with the highest activity against leukemia and renal histological cancer types. This compound fared the strongest in the renal panel because of its cytostatic activity against the renal cancer cell line A498. The 蝤10,000-fold increase in cytostatic activity accompanying the change from methyl to methoxyethyl indicates that such oxygen-containing side chains should be the subject of further development.

4.a.iii. Open analogues of wakayin

Besson et al evaluated five analogues (42a-42e) described in Scheme 6 for their effects on cell proliferation and cell cycle progression on a murine L1210 leukemia cell line. [53]. IC50 values are reported in the Table 5. Compound 42a represents a strict open analogue of wakayin. This compound is the least active of the four tested compounds on the L1210 cell line. As a result, the authors suggest that the enhanced flexibility of the substituent at C-7 may not be favorable for interaction with biological targets. However, compounds 42b-e all inhibited the growth of L1210 cells at concentrations less than 0.5μM. This difference in activity could be attributed to the compounds' water solubility due to the substitution by a primary amino or an amino alkyl group. Despite interesting antiproliferative properties, none of the pyrroloiminoquinone derivatives induce significant modification of the L1210 cell cycle, proving that the pyrroloiminoquinone skeleton on its own is not able to exert a specific cytotoxic action.

Scheme 6. Synthesis of an open analogue of wakayin.

4.a.iv. Aza analogues of tsitsikammamine

Several aza-analogues of natural products have been reported to have better antitumor activity compared to those of the corresponding natural products. In 2006, Delfourne group synthesized compounds 65a and 65b (Scheme 9) in which the pyrrole ring of the pyrroloquinone moiety has been replaced by a pyrazole ring to represent aza analogues of both wakayin and tsitsikammamine [55]. These scaffolds were subjected to a cell-free assay to study their ability to inhibit the DNA cleavage activities of human topoisomerases I and II. Unfortunately, no inhibition of topoisomerase II activity was observed at the maximum tested concentration, limited by final DMSO concentration in the assay mixture by both 65a and 65b. Additionally, 65b produced no effect on topoisomerase I also. A partial activity was observed at 100 μM for 65a against topoisomerase I. Surprisingly, the precursor tricyclic analogue mixture of 61a/b inhibited the catalytic activity of topoisomerase I, with potency comparable to that of camptothecin.

Scheme 9. Synthesis of aza analogues of tsitsikammamines.

4.a.v. Enzymatic IDO1 and MTT results of various cancer cell lines exhibited by tsitsikammamine analogues

Tsitsikammamines analogues and the corresponding synthetic intermediates that were described in scheme 7 and 8 were evaluated in an in vitro antiproliferative assay against the U373 glioblastoma, A549 non-small-cell lung cancer, and PC-3 prostate cancer cell lines as well as two human normal fibroblast cell lines (NHDF and Wi38) [54]. These cell lines were specifically chosen because they display distinct sensitivities to various cytotoxic compounds. For example both U373 and A549 cell lines are resistant to apoptosis, while PC-3 cells are sensitive to apoptosis. Likewise, U373 is sensitive to autophagy-related cell death and A549 is sensitive to lysosomal membrane permeabilization related cell death. Thus, this combination of cell lines serves to elucidate the mechanism of action of the tsitsikammamines analogues for their antiproliferative activity. The result of this study is summarized in Table 6.

Table 6. Activities of tsitsikammamine analogues against enzymatic IDO1 and MTT results on various cancer cell lines.

| Compd ID | Structure | U373 GBM IC50 (μM) | A549 NSCLC IC50 (μM) | PC-3 IC50 (μM) | Mean IC50 (μM) enzymatic assay | mIDO1 inh. @ 10 μM (%) | mTDO1 inh. @ 10 μM (%) | Cell viability@ 10 μM (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 48 |

|

>100 | >100 | 9.5 | 26.9 | 31.3 | NI | >90 |

| 49 |

|

>100 | >100 | 9.7 | 10.1 | 17.4 | NI | >90 |

| 50 |

|

48.5 | 52.4 | 33.7 | 2.8 | 26.1 | NI | 83 |

| 51 |

|

3.2 | 4.1 | 4.2 | 5.4 | 15.6 | NI | 80 |

| 52 |

|

57.4 | 15.4 | >100 | 2.2 | 32.0 | 3.1 | >90 |

| 53 |

|

>100 | >100 | >3 | 0.9 | 19.4 | NI | >90 |

| 54 |

|

28.3 | 35.7 | 26.1 | 5.6 | 40.2 | 4.7 | >90 |

| 55 |

|

8.5 | 11.2 | 31.3 | 11.9 | 26.0 | NI | >90 |

| 56 |

|

41.4 | 3.1 | >100 | 4.2 | ND | ND | <50 |

| 57 |

|

4.1 | 38.1 | 55.7 | 7.1 | ND | ND | <50 |

| 58 |

|

62.2 | 35.2 | 63.7 | 7.0 | 5.3 | NI | >90 |

| 1a |

|

18.1 | 15.6 | 23.0 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

NA: not available; NI: no inhibition; ND: not determined.

Compounds 48 and 49 displayed significant anti-tumor activity against PC-3 prostate cancer cells while having minimal effect against U373 GBM and A549 NSCLC cells, suggesting activation of apoptosis. In contrast, compounds 56 and 52 may employ non-apoptotic cell death processes for anti-tumor activity.

Compound's regiochemistry consistent with the natural product tsitsikammamine A usually appeared to display higher in vitro antitumor activity than their regioisomers (eg: 58, 1a, 51-55). Compound 51 emerged to be the most active; it was the only analogue to achieve single digit μM range growth inhibitory IC50 in vitro for the three cell lines under study. Authors concluded that 51 and its derivatives represent interesting novel anti-cancer agents whose effects could be associated with a specific antiproliferative activity.

Three years later, the same group revisited this series of analogues to elucidate the mechanism of cell toxicity and have shown these compounds exert inhibitory activity on indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase, an enzyme involved in tumoral immune resistance [67]. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO1) is an enzyme that exerts its immunosuppressive effects on T-lymphocytes in a twofold manner: by depleting Trp locally and by action of toxic Trp catabolites. Tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase (TDO) has also recently been shown to be expressed constitutively in human glioblastomas where it promotes tumor progression by action of a downstream tryptophan catabolite kynurenine which acts as an endogenous ligand of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. It has been shown that TDO inhibition reverses tumoral immune resistance in vivo. Thus the recent years witnessed many attempts to discover and develop IDO and TDO inhibitors [68-70].

The key results of the inhibitory study of tsitsikammamine derivatives and synthetic intermediates on IDO1 and TDO are summarized in the Table 6. Consistent with the in vitro activity in the MTT colorimetic assay, the regioisomer leading to the natural geometry of the final tetracyclic product, 1a, was at least twice as active on IDO1 in the enzymatic assay than the corresponding regioisomer (eg: 55-51, 54-50, 56-52). Secondly, deletion of the conjugated double bond within the anisyl moiety in the tricyclic series was found to improve the bioactivity in the enzymatic assays (eg: 55-54, 51-50). Compounds bearing this structural modification produced greater than 40% IDO1 inhibition at 10μM. Lastly, the tetracyclic iminioquinone ring enhances the cellular toxicity (eg: 55-56, 51-52). It should be noted that no inhibition on TDO was observed, establishing the selectivity of these compounds for IDO1. Thus, these series of compounds show potential for future development in the field of anticancer immunotherapy.

4.b Bioactivities of Zyzzyanones

Initial biological evaluation of zyzzyanones revealed that they exhibit moderate cytotoxic activity against mouse Ehlrich carcinoma cells (IC50, 25 μg/mL) for all four natural products. Zyzzyanone A inhibited the cell division of fertilized sea urchin eggs at concentration of 25μg/mL and also exhibited UV-A and UV-B absorbing activity. These data support the earlier suggestion that the intact pyrroloiminoquinone moiety enhances cytotoxicity. No new reports have been made following these results.

5. Conclusions

Oceans account for a major proportion of the earth's surface. Marine natural products are continuously isolated from the wide range of invertebrate species found in oceans such as sponges, mollusks, ascidians, corals, and algae. A class of structural scaffolds known as bispyrroloquinones is present in three subclasses of biologically active marine alkaloids: wakayin, tsitsikammamines, and zyzzyanones. Since their first isolation and preliminary biological evaluation was published, several reports of their total synthesis and the synthesis of their analogues have emerged. Both tsitsikammamines and zyzzyanones have been synthesized to its final structure. Though several efforts have been made by different groups to accomplish total synthesis of wakayin, none have been successfully developed till date. However, aza and pyrazolic analogues as well as open analogues of wakayin have been reported.

Several derivatives of tsitsikammamines and wakayin have previously been shown to be potent anticancer agents. Mechanism of action of tsitsikammamines is reported to be through inhibition of topoisomerases. One additional possible mechanism of anticancer activity of tsitsikammamines analogues stems from their inhibition on indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase, an enzyme involved in tumoral immune resistance. However, further investigation on the exact mechanism for their bioactivity is still required for many analogues, which will be beneficial for the ongoing development and lead optimization of this class of compounds accomplished by several groups. Nevertheless, bispyrroloquinones have established their potential for future development as anticancer agents and in our opinion, this class of molecules deserve more scientific attention and interdisciplinary research to see a transition into a number of new treatments for cancer in the years to come.

Table 3. Cytotoxicity activities against the human colon tumor cell line and topoisomerase I inhibition of tsitsikammamines and wakayin.

| Structure | Compound ID | HCT-116 (IC50, μM) | Ks (μM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tsitsikammamine A | 1a | 1.4 | 15 |

| Tsitsikammamine B | 1b | 2.4 | 45 |

| Tsitsikammamine A N-Oxime | 1c | 128.2 | 20 |

| Tsitsikammamine B N-Oxime | 1d | 16.5 | 30 |

| Wakayin | 2 | 1.5 | 20 |

Acknowledgments

We thank the current and former members of Velu lab for their contributions to the research projects that were cited in this review. SEV was supported by a UAB Breast Spore pilot grant and a Collaborative Programmatic Development grant from UAB Comprehensive Cancer Center. He was also supported by grant number 1UL1RR025777 from the NIH National Center for Research Resources.

List of acronyms

- BBr3

Boron tribromide

- Boc

tert-Butoxycarbonyl

- CH2Cl2

Methylene chloride

- CHCl3

Chloroform

- CH3NO2

Nitromethane

- COSY

Correlation spectroscopy

- DDQ

2,3-Dichloro-5,6-dicyano-1,4-benzoquinone

- DMF

Dimethyl formamide

- DMSO

Dimethyl sulfoxide

- DNA

Deoxy ribonucleic acid

- DQCOSY

Double quantum filtered COSY

- EtOH

Ethanol

- FeCl3

Ferric chloride

- FeCl2

Ferrous chloride

- HBr

Hydrobromic acid

- HCl

Hydrochloric acid

- HMBC

Heteronuclear multiple bond coherence

- HMQC

Heteronuclear multiple quantum coherence

- HNO3

Nitric acid

- HOAc

Acetic acid

- HPLC

High performance liquid chromatography

- HRFABMS

High resolution fast atom bombardment mass spectroscopy

- IC50

Inhibitory concentration at 50%

- KOH

Potassium hydroxide

- LiAlH4

Lithium aluminum hydride

- MeI

Methyl iodide

- MeOH

Methanol

- MIC

Minimum inhibitory concentration

- MnO2

Manganese dioxide

- MsCl

Methane sulfonyl chloride

- NaH

Sodium hydride

- NaHCO3

Sodium bicarbonate

- NaN3

Sodium azide

- NaOH

Sodium hydroxide

- NH4OAc

Ammonium acetate

- NiCl2

Nickel chloride

- NMR

Nuclear magnetic resonance

- Pd

Palladium

- POCl3

Phosphoryl chloride

- TFA

Trifluoroacetic acid

- THF

Tetrahydrofuran

- UV

Ultraviolet

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: No potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Mehbub MF, Lei J, Franco C, et al. Marine sponge derived natural products between 2001 and 2010: trends and opportunities for discovery of bioactives [J] Mar drugs. 2014;12(8):4539–4577. doi: 10.3390/md12084539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martins A, Vieira H, Gaspar H, et al. Marketed marine natural products in the pharmaceutical and cosmeceutical industries: tips for success [J] Mar drugs. 2014;12(2):1066–1101. doi: 10.3390/md12021066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haefner B. Drugs from the deep: marine natural products as drug candidates [J] Drug discovery today. 2003;8(12):536–544. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6446(03)02713-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Simmons TL, Andrianasolo E, McPhail K, et al. Marine natural products as anticancer drugs [J] Mol Cancer Ther. 2005;4(2):333–342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Venter JC, Remington K, Heidelberg JF, et al. Environmental genome shotgun sequencing of the Sargasso Sea [J] Science New York. 2004;304(5667):66–74. doi: 10.1126/science.1093857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Proksch P, Edrada RA, Ebel R. Drugs from the seas - current status and microbiological implications [J] Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2002;59(2-3):125–134. doi: 10.1007/s00253-002-1006-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cherigo L, Lopez D, Martinez-Luis S. Marine natural products as breast cancer resistance protein inhibitors [J] Mar drugs. 2015;13(4):2010–2029. doi: 10.3390/md13042010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Badwan AA, Rashid I, Omari MM, et al. Chitin and chitosan as direct compression excipients in pharmaceutical applications [J] Mar drugs. 2015;13(3):1519–1547. doi: 10.3390/md13031519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boucle S, Melin C, Clastre M, et al. Design, synthesis and evaluation of new marine alkaloid-derived pentacyclic structures with anti-tumoral potency [J] Mar drugs. 2015;13(1):655–665. doi: 10.3390/md13010655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Jesus Raposo MF, de Morais AM, de Morais RM. Marine Polysaccharides from Algae with Potential Biomedical Applications [J] Mar drugs. 2015;13(5):2967–3028. doi: 10.3390/md13052967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reen FJ, Gutierrez-Barranquero JA, Dobson AD, et al. Emerging Concepts Promising New Horizons for Marine Biodiscovery and Synthetic Biology [J] Mar drugs. 2015;13(5):2924–2954. doi: 10.3390/md13052924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gammone MA, D'Orazio N. Anti-obesity activity of the marine carotenoid fucoxanthin [J] Mar drugs. 2015;13(4):2196–2214. doi: 10.3390/md13042196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jakubowska N, Szelag-Wasielewska E. Toxic picoplanktonic cyanobacteria--review [J] Mar drugs. 2015;13(3):1497–1518. doi: 10.3390/md13031497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pomponi SA. The bioprocess-technological potential of the sea [J] J Biotechnol. 1999;70(1-3):5–13. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brodowicz T. Trabectedin in soft tissue sarcomas [J] Future Oncol. 2014;10(8 Suppl):s1–5. doi: 10.2217/fon.14.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jordan K, Jahn F, Jordan B, et al. Trabectedin: Supportive care strategies and safety profile [J] Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2015;94(3):279–290. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2015.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Petek BJ, Loggers ET, Pollack SM, et al. Trabectedin in soft tissue sarcomas [J] Mar drugs. 2015;13(2):974–983. doi: 10.3390/md13020974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kollar P, Rajchard J, Balounova Z, et al. Marine natural products: bryostatins in preclinical and clinical studies [J] Pharm Biol. 2014;52(2):237–242. doi: 10.3109/13880209.2013.804100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blunt JW, Copp BR, Munro MH, et al. Marine natural products [J] Nat Prod Rep. 2006;23(1):26–78. doi: 10.1039/b502792f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sun MK, Alkon DL. Bryostatin-1: pharmacology and therapeutic potential as a CNS drug [J] CNS Drug Rev. 2006;12(1):1–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1527-3458.2006.00001.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Irie K, Yanagita RC. Synthesis and biological activities of simplified analogs of the natural PKC ligands, bryostatin-1 and aplysiatoxin [J] Chem Rec. 2014;14(2):251–267. doi: 10.1002/tcr.201300036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Munoz-Alonso MJ, Gonzalez-Santiago L, Martinez T, et al. The mechanism of action of plitidepsin [J] Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2009;10(6):536–542. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Galmarini CM, D'Incalci M, Allavena P. Trabectedin and plitidepsin: drugs from the sea that strike the tumor microenvironment [J] Mar drugs. 2014;12(2):719–733. doi: 10.3390/md12020719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scarpace SL. Eribulin mesylate (E7389): review of efficacy and tolerability in breast, pancreatic, head and neck, and non-small cell lung cancer [J] Clin Ther. 2012;34(7):1467–1473. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2012.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Preston JN, Trivedi MV. Eribulin: a novel cytotoxic chemotherapy agent [J] Ann Pharmacother. 2012;46(6):802–811. doi: 10.1345/aph.1Q636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Higa T, Tanaka J, Kitamura A, et al. Bioactive compounds from marine sponges [J] Pure Appl Chem. 1994;66:2227–2230. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sipkema D, Franssen MC, Osinga R, et al. Marine sponges as pharmacy [J] Mar Biotechnol NY. 2005;7(3):142–162. doi: 10.1007/s10126-004-0405-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schwartsmann G, Brondani da Rocha A, Berlinck RG, et al. Marine organisms as a source of new anticancer agents [J] The lancet oncology. 2001;2(4):221–225. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(00)00292-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Faulkner DJ. Marine natural products [J] Nat Prod Rep. 2002;19(1):1–48. doi: 10.1039/b009029h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Blunt JW, Copp BR, Munro MH, et al. Marine natural products [J] Nat Prod Rep. 2003;20(1):1–48. doi: 10.1039/b207130b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang C, Li Q, Li Y. Targeting nuclear receptors with marine natural products [J] Mar drugs. 2014;12(2):601–635. doi: 10.3390/md12020601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Perry NB, Blunt JW, Munro MHG. Cytotoxic pigments from new zealand sponges of the genus latrunculia : discorhabdins a, b and c [J] Tetrahedron. 1988;44(6):1727–1734. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Radisky DC, Radisky ES, Barrows LR, et al. Novel cytotoxic topoisomerase II inhibiting pyrroloiminoquinones from Fijian sponges of the genus Zyzzya [J] J Am Chem Soc. 1993;115(5):1632–1638. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Antunes EM, Copp BR, Davies-Coleman MT, et al. Pyrroloiminoquinone and related metabolites from marine sponges [J] Nat prod rep. 2005;22(1):62–72. doi: 10.1039/b407299p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dijoux MG, Gamble WR, Hallock YF, et al. A New Discorhabdin from Two Sponge Genera [J] J Nat Prod. 1999;62(4):636–637. doi: 10.1021/np980465r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.D'Ambrosio M, Guerriero A, Chiasera G, et al. Epinardins A-D, new pyrroloiminoquinone alkaloids of undetermined deep-water green demosponges from pre-Antarctic Indian ocean [J] Tetrahedron. 1996;52(26):8899–8906. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chang LC, Otero-Quintero S, Hooper JN, et al. Batzelline D and isobatzelline E from the indopacific sponge Zyzzya fuliginosa [J] J Nat Prod. 2002;65(5):776–778. doi: 10.1021/np010581l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Carney JR, Scheuer PJ, Kelly-Borges M. Makaluvamine G, a cytotoxic pigment from an an Indonesian Sponge Histodermella sp [J] Tetrahedron. 1993;49(38):8483–8486. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Casapullo A, Cutignano A, Bruno I, et al. Makaluvamine P, a new cytotoxic pyrroloiminoquinone from Zyzzya cf. fuliginosa [J] J Nat Prod. 2001;64(10):1354–1356. doi: 10.1021/np010053+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hu JF, Schetz JA, Kelly M, et al. New antiinfective and human 5-HT2 receptor binding natural and semisynthetic compounds from the Jamaican sponge Smenospongia aurea [J] J Nat Prod. 2002;65(4):476–480. doi: 10.1021/np010471e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schmidt EW, Harper MK, Faulkner DJ. Makaluvamines H-M and damirone C from the Pohnpeian sponge Zyzzya fuliginosa [J] J Nat Prod. 1995;58(12):1861–1867. doi: 10.1021/np50126a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Venables DA, Concepcion GP, Matsumoto SS, et al. Makaluvamine N: a new pyrroloiminoquinone from Zyzzya fuliginosa [J] J Nat Prod. 1997;60(4):408–410. doi: 10.1021/np9607262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Venables DA, Barrows LR, Lassota P, et al. Veiutamine. A new alkaloid from the Fijian sponge Zyzzya fuliginosa [J] Tetrahedron Lett. 1997;38(5):721–722. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gunasekera SP, Zuleta IA, Longley RE, et al. Discorhabdins S, T, and U, New Cytotoxic Pyrroloiminoquinones from a Deep-Water Caribbean Sponge of the Genus Batzella [J] J Nat Prod. 2003;66(12):1615–1617. doi: 10.1021/np030292s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Davies-Coleman MT, Hooper GJ, Kelly-Borges M, et al. New alkaloids from a south african Latrunculid sponge [J] Tetrahedron Lett. 1996;37(39):7135–7138. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Antunes EM, Beukes DR, Kelly M, et al. Cytotoxic pyrroloiminoquinones from four new species of South African latrunculid sponges [J] J Nat Prod. 2004;67(8):1268–1276. doi: 10.1021/np034084b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Utkina NK, Makarcheno AE, Denisenko VA, et al. Zyzzyanone A, a novel pyrrolo[3,2-f]indole alkoloid from the Australian marine sponge Zyzza fuliginosa [J] Tetrahedron Lett. 2004;45:7491–7494. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Utkina NK, Makarchenko AE, Denisenko VA. Zyzzyanones B-D, dipyrroloquinones from the marine sponge Zyzzya fuliginosa [J] J Nat Prod. 2005;68(9):1424–1427. doi: 10.1021/np050154y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang L, Cava MP, Rogers RD, et al. Synthesis of a wakayin model compound: oxidative formation of a pyrrole ring in the indol-3-yl-indoloquinone system [J] Tetrahedron Lett. 1998;39:7677–7678. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Barret R, Roue N. Synthesis of a bis-pyrrolo-quinone structure analogue to wakayin [J] Tetrahedron Lett. 1999;40:3889–3890. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Legentil L, Benel L, Bertrand V, et al. Synthesis and antitumor characterization of pyrazolic analogues of the marine pyrroloquinoline alkaloids: wakayin and tsitsikammamines [J] J med chem. 2006;49(10):2979–2988. doi: 10.1021/jm051247f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hoang H, Huang X, Skibo EB. Synthesis and in vitro evaluation of imidazole-based wakayin analogues [J] Org Biomol Chem. 2008;6(17):3059–3064. doi: 10.1039/b806883f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Beneteau V, Pierre A, Pfeiffer B, et al. Synthesis and antiproliferative evaluation of 7-aminosubstituted pyrroloiminoquinone derivatives [J] Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2000;10(19):2231–2234. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(00)00450-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rives A, Le Calve B, Delaine T, et al. Synthesis and antitumor evaluation of analogues of the marine pyrroloiminoquinone tsitsikammamines [J] Eur J Med Chem. 2010;45(1):343–351. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2009.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Legentil L, Lesur B, Delfourne E. Aza-analogues of the marine pyrroloquinoline alkaloids wakayin and tsitsikammamines: synthesis and topoisomerase inhibition [J] Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2006;16(2):427–429. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2005.09.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nadkarni DH, Murugesan S, Velu SE. Total synthesis of zyzzyanones A-D [J] Tetrahedron. 2013;69(20):4105–4113. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2013.03.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Showalter HD, Pohlmann G. An improved synthesis of 4,7-dimethoxy-1H-indole [J] Org Prep Proceed Int. 1992;24:484–488. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Roberts D, Joule J. Synthesis of Pyrrolo[4,3,2-de]quinolines from 6,7-Dimethoxy-4-methylquinoline. Formal Total Syntheses of Damirones A and B, Batzelline C, Isobatzelline C, Discorhabdin C, and Makaluvamines A−D [J] J Org Chem. 1997;62(3):568–577. doi: 10.1021/jo961743z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sadanandan EV, Pillai SK, Lakshmikantham MV, et al. Efficient Syntheses of the Marine Alkaloids Makaluvamine D and Discorhabdin C: The 4,6,7-Trimethoxyindole Approach [J] J Org Chem. 1995;60(6):1800–1805. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Moukharskaya J, Verschraegen C. Topoisomerase 1 inhibitors and cancer therapy [J] Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2012;26(3):507–525. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2012.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kathiravan MK, Khilare MM, Nikoomanesh K, et al. Topoisomerase as target for antibacterial and anticancer drug discovery [J] J enzym inhib med chem. 2013;28(3):419–435. doi: 10.3109/14756366.2012.658785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pendleton M, Lindsey RH, Jr, Felix CA, et al. Topoisomerase II and leukemia [J] Ann NY Acad Sci. 2014;1310:98–110. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Marshall KM, Holden JA, Koller A, et al. AK37: the first pyridoacridine described capable of stabilizing the topoisomerase I cleavable complex [J] Anticancer drugs. 2004;15(9):907–913. doi: 10.1097/00001813-200410000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dijoux MG, Schnabel PC, Hallock YF, et al. Antitumor activity and distribution of pyrroloiminoquinones in the sponge genus Zyzzya [J] Bioorg Med Chem. 2005;13(21):6035–6044. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2005.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Khan QA, Lu J, Hecht SM. Calothrixins, a new class of human DNA topoisomerase I poisons [J] J Nat Prod. 2009;72(3):438–442. doi: 10.1021/np8007232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kokoshka JM, Capson TL, Holden JA, et al. Differences in the topoisomerase I cleavage complexes formed by camptothecin and wakayin, a DNA-intercalating marine natural product [J] Anticancer drugs. 1996;7(7):758–765. doi: 10.1097/00001813-199609000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dolusic E, Larrieu P, Meinguet C, et al. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase inhibitory activity of derivatives of marine alkaloid tsitsikammamine A [J] Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2013;23(1):47–54. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yamamoto Y, Murakami Y, Hoshi M, et al. [Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1 modulates the immuneresponse; the new therapeutic targets of this drug] [J] Nihon Yakurigaku Zasshi. 2013;142(2):85–88. doi: 10.1254/fpj.142.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Prendergast GC, Smith C, Thomas S, et al. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase pathways of pathogenic inflammation and immune escape in cancer [J] Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2014;63(7):721–735. doi: 10.1007/s00262-014-1549-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Barth H, Raghuraman S. Persistent infectious diseases say - IDO. Role of indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase in disease pathogenesis and implications for therapy [J] Crit Rev Microbiol. 2014;40(4):360–368. doi: 10.3109/1040841X.2012.742037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]