Abstract

Environmental aromatic acids are transformed to chemical energy in bacteria that possess the requisite secondary pathways. Some of these pathways rely on the activation of the aromatic acid by coenzyme A (CoA) thioesterification catalyzed by an aromatic acid: CoA ligase. Adaptation of such pathways to the bioremediation of man-made pollutants such as polychlorinated biphenyl (PCB) and dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT) requires that the chlorinated benzoic acid by-product formed can be eliminated by further degradation. To take advantage of natural benzoic acid degrading pathways requiring initial ring activation by thioesterification, the pathway aromatic acid: CoA ligase must be an effective catalyst with the chlorinated benzoic acid. The present study, which focuses on the 4-chlorobenzoate: CoA ligase (CBL) of the 4-monochlorobiphenyl degrading bacterium Alcaligenes sp strain ALP83, was carried-out to determine if the 4-chlorobenzoate binding site of this enzyme can be transformed by rational design to recognize the chlorobenzoic acids formed in course of breakdown of other environmental PCB congeners. The fundamental question addressed in this study is whether it is possible to add or subtract space from the substrate-binding pocket of this ligase (so to complement the topology of the unnatural aromatic substrate) without causing disruption of the ligase catalytic machinery. Herein, we report the results of a substrate specificity analysis that, when interpreted within the context of the X-ray crystal structures, set the stage for the rational design of the ligase for thioesterification of two PCB derived chlorobenzoic acids. The ligase was first optimized to catalyze CoA thioesterification of 3,4-dichlorobenzoic acid, a poor substrate, by truncating Ile303, a large hydrophobic residue that packs against ring meta-C(H). The structural basis for the ~100-fold enhancement in the rate of 3,4-dichlorobenzoate thioesterification catalyzed by the I303A and I303G CBL mutants was validated by crystal structure determination of the 3,4-dichlorobenzoate bound enzymes. Structure determinations of the I303 mutant complexes of 3-chlorobenzoate, a very poor substrate, revealed nonproductive binding as a result of the inability of the substrate ring C(4)H to fill the pocket that binds the C(4)Cl of the native substrate. The C(4)Cl pocket of the CBL I303A mutant was then reduced in size by strategic amino acid replacement. A 54-fold improvement in catalytic efficiency was observed for the CBL F184W/I303A/V209T triple mutant. The results of this investigation are interpreted as evidence that the plasticity of ligase catalytic scaffold is sufficient to allow expansion of substrate range by rational design. The combination of structural and kinetic analyses of the constructed mutants proved to be an effective approach to engineering the ligase for novel substrates.

Keywords: 4-chorobenzoate: CoA ligase, 4-chlorobenzoate, aromatic degradation, polychlorinated biphenyl, dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane, 4-hydroxybenzoate, coenzyme A, 4-chlorobenzoyl-adenosine-5′-monophosphate, adenylate-forming enzyme superfamily, substrate recognition, rational design, protein engineering, Alcaligenes sp. strain ALP83

Chlorinated aromatics, exemplified by polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs)1 and dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT), have accumulated in the environment as a result of global dispersion (1–3). Research into methods applicable to the removal of PCB and DDT contaminants from the environment has been stimulated by the demonstration of their toxic, carcinogenic, and teratogenic properties (4–7). One effective strategy is “bioremediation”, a process that employs the chemical pathways of naturally occurring bacteria, or bacteria that have been genetically engineered, for in vivo degradation (8–11).

PCBs are chlorinated analogs of biphenyl. Biphenyl is oxidatively degraded by specialized soil-dwelling bacteria to benzoate and 2-hydroxypenta-2,4-dienoate (12–17). These two products are further oxidized to metabolites that are degraded by the citric acid cycle. PCB congeners that are chlorinated at only one of the two aromatic rings are converted to 2-hydroxypenta-2,4-dienoate and chlorinated benzoate (10). If not degraded, the chlorinated benzoate by-product accumulates and inhibits bacterial growth (10). Thus, in order to be effective at the bioremediation of a PCB the bacterium must couple the biphenyl pathway with a chlorobenzoate-degrading pathway. Such a strategy has been observed to operate in the natural 4-monochlorobiphenyl degrader Alcaligenes sp strain ALP83 (18, 19). This strain was isolated from PCB-contaminated soil and shown to degrade 4-monochlorobiphenyl to carbon dioxide by using the 4-chlorobenzoate dehalogenation pathway in combination with the biphenyl oxidation pathway (Scheme 1) (20, 21). The conversion of the 4-chlorobenzoate to the metabolite 4-hydroxybenzoate transforms the growth inhibitor to an additional source of chemical energy.

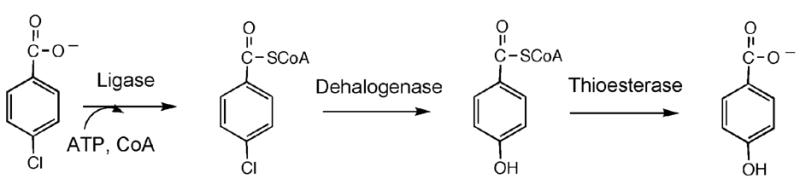

Scheme 1.

4-Chlorobenzoate Dehalogenation Pathway

The 4-chlorobenzoate is activated for hydrolytic dehalogenation by conversion to the corresponding CoA thioester (22). CoA thioesterification of the aromatic carboxylate group is a strategy used in other bacterial secondary pathways that degrade aromatic rings to metabolites, as exemplified by the phenylacetate (23), benzoate (24) and the reductive 4-hydroxybenzoate (25) catabolic pathways. These pathways serve as valuable starting points for the engineering of novel pathways for use in bioremediation of man-made aromatic pollutants. The mono-, di- and trichlorinated benzoates generated from microbial degradation of asymmetric PCBs, for example, might be mineralized by using designer pathways that employ engineered enzymes. The aromatic acid: CoA ligase catalyzes the first step of the pathway and therefore it is the logical starting point for engineering the pathway enzymes for degradation of a novel substrate.

The bacterial ligases that catalyze the transformation of the aromatic acid to the corresponding CoA thioester are not well characterized owing in part to their instability and/or poor expression of their encoding gene in E. coli.2 The 4-chlorobenzoate: CoA ligase (CBL), however is an exception (26). The recently reported X-ray structure of the Alcaligenes sp strain ALP83 CBL complexed with 4-chlorobenzoate (27) opened the door to the expansion of substrate range by rational design of the 4-chlorobenzoate binding site. Rational design alone, or in combination with saturation mutagenesis, has been successfully used in the modification of enzyme specificity (for recent examples, see references 28–35).

The first phase of the work, reported herein, focused on the analysis of the substrate specificity of CBL within the context of the structure of the 4-chlorobenzoate binding site. 3,4-Dichlorobenzoate and 3-chlorobenzoate were selected as substrates for the second phase of our work, which concentrated on the restructuring of the 4-chlorobenzoate binding pocket by strategic amino acid replacement. The results reported below show that the substrate range of CBL is subject to extension through structureguided protein engineering. The plasticity of the binding site, which tolerates these structural changes, is no doubt a key component of the natural evolution of the acyl-adenylate-forming enzyme superfamily (to which CBL belongs) (22), allowing continual diversification within the family to reach novel organic acid metabolites.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Except where mentioned, all chemicals and coupling enzymes (adenylate kinase (EC 2.7.4.3), pyruvate kinase (EC 2.7.1.40) and lactate dehydrogenase (EC 1.1.1.27)) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Custom-synthesized PCR primers were obtained from Invitrogen, as were the restriction enzymes, the pfu polymerase, and the T4 DNA ligase. Competent cells JM 109 and BL21 (DE3) were purchased from Stratagene, and pQE-70 vector was purchased from QIAGEN. DNA sequencing analysis was carried by the DNA Sequencing Facility of the University of New Mexico. SDS-PAGE was performed with gels prepared from a 12% acrylamide gel with a 3% stacking gel (37.5:1 acrylamide: biacryamide ratio) (Bio-Rad).

CBL Preparation

A single colony of E.coli JM109 containing the plasmid Sph I-Bgl II-pQE-70-CBAL (20, 21) was used to inoculate 10 mL of LB medium containing 50 μg/mL ampicillin at 37 °C with mixing at 250 RPM. The 10 mL culture was then used to inoculate 10 L of fresh LB medium containing 5 μg/mL ampicillin, and the culture was grown at 20 °C with mixing at 200 RPM. After 26 h (OD ~0.7 at 600 nm) isopropyl-β-thiogalactopyranoside was added to a final concentration of 1 mM. Following incubation at 20 °C and mixing at 200 RPM for 10 h, the cells were harvested by centrifugation at 5000 × g for 15 min. The 10 g pellet was suspended in 100 mL of lysis buffer (50 mM NaH2PO4, pH 8.0, 10 mM imidazole, 1 mM DTT) containing 10 μL of 0.1 mM of the protease inhibitor PMSF, passed through a French press at 1200 PSIG and then centrifuged at 48000 × g and 4 °C for 30 min. The supernatant was loaded onto a Ni-NTA Agarose column (QIAGEN, 25 mL), which had been pre-equilibrated with the lysis buffer. The column was washed with 500 mL of wash buffer (50 mM NaH2PO4, pH 8.0, 50 mM imidazole, 1 mM DTT) and then eluted with 200 mL of elution buffer (50 mM NaH2PO4, 250 mM imidazole, 1 mM DTT at pH 8.0). The fractions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and then selectively pooled and dialyzed for 3 h against three changes of 1.5-L 50 mM K+Hepes buffer containing 1 mM DTT, (pH 7.5, 25 °C). The protein purity was verified by SDS-PAGE analysis. The protein concentration was determined by using the Bradford method (36) and by measuring the absorbance at 280 nm (ε = 27,760 M−1 cm−1). Yield: 6 mg/gm wet cells.

CBL Activity Assays

Direct continuous assay

The CBL reaction with 4-chlorobenzoate was determined at 25 °C by measuring the increase in the absorbance of the 1 mL reaction solution at 300 nm (Δε = 2.5 mM−1cm−1). The 1 mL assay solution contained 2 mM 4-chlorobenzoate, 1 mM CoA, 3.5 mM ATP and 15 mM MgCl2 in 50 mM K+Hepes (pH 7.5).

Coupled assay

The CBL reactions with the various carboxylate substrates were monitored by using the coupled assay that detects the formation of AMP through the sequential activities of adenylate kinase, pyruvate kinase, and lactate dehydrogenase. The 1 mL solutions initially contained 1 mM CoA, 3.5 mM ATP and 15 mM MgCl2, 200 μM NADH, 3 mM PEP, 5 mM KCl, 11 U adenylate kinase (EC 2.7.4.3), 9 U pyruvate kinase (EC 2.7.1.40) and 9 U lactate dehydrogenase (EC 1.1.1.27) in 50 mM K+Hepes (pH7 .5, 25 °C). The decrease in absorbance at 340 nm due to the oxidation of two molecules of NADH per molecule of AMP formed was monitored.

Steady-state Kinetic Constant Determinations

The initial velocity for CBL catalyzed reactions were measured as a function of one substrate concentration (varied between 0.5 and 5-fold KM) with the two co-substrates at fixed, saturating concentration (1 mM CoA, 3.5 mM ATP, 2 mM 4-chlorobenzoate). The concentration of MgCl2 used for each reaction solution is 11.5 mM plus the mM concentration of the ATP present. Reaction solutions were buffered with 50 mM K+Hepes (pH 7.5, 25 °C). The Vmax and KM values were calculated from the initial velocity data using equation (1) and the computer program KinetAsyst. The kcat was calculated from the ratio of Vmax and enzyme concentration.

| (1) |

where V is the initial velocity, Vmax the maximum velocity, [S] the varied substrate concentration, KM the Michaelis constant.

Mutant CBL Preparation

The CBL mutant genes were prepared by using a PCR-based method that employed the Alcaligenes sp. strain ALP83 (NCBI accession AF 537222.1) derived SphI-BglII-pQE-70-CBAL subclone (20, 21) as the template, and commercial primers. The purified PCR product was digested with SphI and BglII (Invitrogen) and ligated to the SphI-BglII-digested plasmid pQE-70 (which includes the 6×His-tag and stop codon (QIAGEN)) with T4 DNA ligase (Invitrogen). The mutant gene sequence was verified by DNA sequencing which was carried out by the Center for Genetics in Medicine, University of New Mexico. The mutant proteins were prepared using the same procedure as that used in the preparation of recombinant wild-type CBL (see above). The homogeneity of each purified mutant CBL was demonstrated by SDS-PAGE analysis.

Crystallization and structure determination of CBL Ile303 mutants

The Ile303 CBL mutant proteins were crystallized by hanging drop vapor diffusion using a precipitant consisting 14–22% pentaerythritol propoxylate 426 (37) and 50 mM 1,3-bis[tris(hydroxymethyl)methylamino]propane (pH 6.5–6.75). The alanine and glycine mutants were each co-crystallized in the presence of ATP and either 3-chlorobenzoate or 3,4-dichlorobenzoate. Crystals were grown at 4 °C and appeared within 1 to 2 days. Crystals were cryoprotected by transferring them sequentially to solutions containing 4 – 24% ethylene glycol, and then mounted in a nylon cryoloop, and cryo-cooled in liquid nitrogen. The final cryoprotectant solution contained 24% ethylene glycol, 24% pentaerythritol propoxylate 426, 50 mM 1,3-bis[tris(hydroxymethyl)methylamino]propane (pH 6.75). Additionally, all cryoprotectant solutions contained 1 mM of ATP and 3-chlorobenzoate or 3,4-dichlorobenzoate.

Data were collected for crystals of the Ile303 CBAL mutants at beamline F2 of the Cornell High Energy Synchrotron Source. Data collection was performed with an ADSC Quantum-210 detector set at a crystal to detector distance of 240 mm using X-rays at a wavelength of 0.97930 Å. Data were indexed, integrated, and scaled with the HKL2000 package (38). Despite the difference in the solution pH prevailing under the crystallization conditions, the crystals were isomorphous to the wild-type crystals used previously (27), however the unit cells were longer by ~2.5%. Because of this increase in the lengths of cell axes, the structures were solved by molecular replacement using MOLREP (39).

The search model used was the SeMet-containing structure (PDB code 1T5H). To generate the search model, the SeMet residues were replaced with methionines, the water molecules and metal ions were removed, and the Ile303 was replaced with the alanine or glycine side chain. In all cases, the solution was the top peak of the rotation and translation searches. The molecular replacement solution was subjected to a round of refinement with REFMAC5 (40)(40) followed by continued cycles of manual model building with COOT (41) and maximum likelihood refinement. Weighted individual B-factors were applied for all models. Near completion of the modeling, TLS refinement (42) was used to apply grouped aniostropic thermal parameters to the N- and C-terminal domains, which resulted in a drop in Rfree. Electron densities for the 3-chlorobenzoate and 3,4-dichlorobenzoate ligands were clear, and their atoms were added after several rounds of model building and refinement. Given the limited resolution, water molecules were conservatively added to spherical, or nearly spherical, density that was present in the difference maps at >2.5σ. Although ATP had been included in the crystallization media, no density for the nucleotide was apparent in any of the structures.

Atomic coordinates and structure factors for all four structures have been deposited with the Protein Data Bank: I303A bound to 3-CB, 2QVZ; I303A bound to 3,4-DCB, 2QWO; I303G bound to 3-CB, 2QVX; and I303G bound to 3,4-DCB, 2QVY.

Results and Discussion

Structural Basis for CBL 4-Chlorobenzoate Recognition

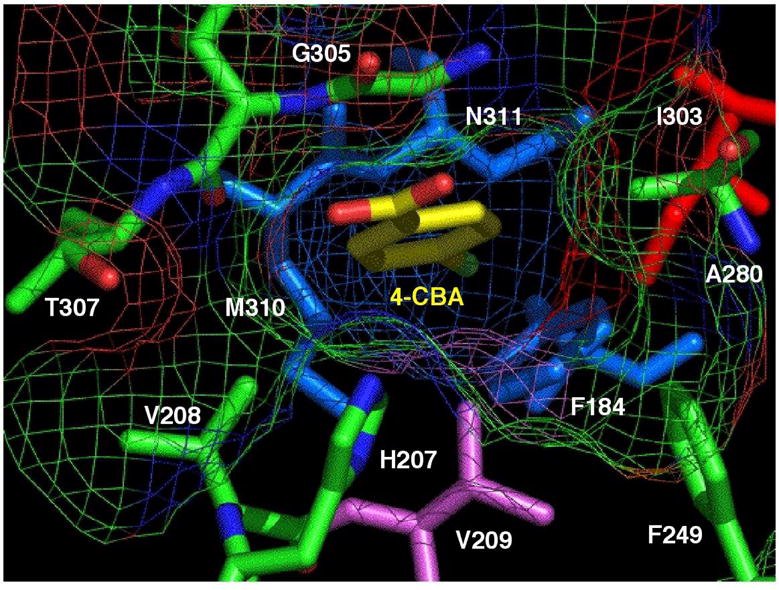

The 4-chlorobenzoate binding pocket residues Phe184, His207, Phe249, Ala280, Ile303, Gly305, Met310, and Asn311 (Figure 1) are conserved among the six additional known CBL sequences from Comamonas, Pseudomonas and Arthrobacter species (divergence to 62% nonidentity between sequence pairs). Binding pocket residues Val208 (Thr in Pseudomonas CBL) and Val209 (Ile in Arthrobacter CBL) on the other hand, are not stringently conserved. The 4-chlorobenzoate aromatic ring and its C(4) chloro substituent are surrounded by the side chains of the nonpolar pocket residues, and by the methylene group of the Asn311 side chain. The structure of unliganded CBL (determined previously at 2.0 Å resolution) shows three solvent molecules present in the 4-chlorobenzoate binding pocket (27). Upon ligand binding, the solvent water molecules are displaced. The short distance (4 Å on average) separating the 4-chlorobenzoate ring carbon atoms and the binding pocket residues allows for Van der Waals interaction. The ring carboxylate projects outside the entrance of the hydrophobic binding pocket, and is positioned 3.7 Å from the His207 imidazole Nτ (Figure 1). This distance is outside of the distance for strong hydrogen bond formation. Thus, unless the distance is decreased by a change in conformation induced by MgATP binding, it may be assumed that the orientation of the ring carboxylate is dictated by the confinement of the aromatic ring within the hydrophobic binding pocket. As this work progressed, we discovered that the hydrophobic binding pocket does in fact play an essential role in productive binding (see discussion of the 3-chlorobenzoate-CBL I303A and I303G complexes).

Figure 1.

A representation of the 4-chlorobenzoate binding pocket in CBL from Alcaligenes sp strain ALP83. The figure was generated from the X-ray coordinates of the wild-type CBL in complex with 4-chlorobenzoate (PDB: 1T5H) (27) by using the graphic program Pymol (52). The 4-chlorobenzoate ligand is shown with yellow carbon atoms, red oxygen atoms and a green chlorine atom.

Based on the structure of the 4-chlorobenzoate binding site we anticipated a narrow substrate range. In order to define this range, the steady-state kinetic constants for CBL catalyzed thioesterification of a series of organic acids were measured, with particular emphasis placed on ring substituted benzoates. The two co-substrates ATP and CoA, and the cofactor Mg+2, were present in the reaction solutions at saturating concentrations (see Table 1). Under these conditions the 4-chlorobenzoate kcat = 9.2 s−1, KM = 0.93 μM and kcat/KM = 9.9 × 106 M−1s−1. With phenylacetate serving as substrate, the kcat value is reduced three orders of magnitude and the kcat/KM value is reduced six orders of magnitude (Table 1). The methylene group increases the distance between the aromatic ring and the carboxylate group, which in turn reduces substrate binding affinity and hinders the orientation of the substrate for reaction with the ATP. The kcat measured for hexanoate thioesterification is ~5-fold lower than that measured for 4-chlorobenzoate thioesterification and the hexanoate kcat/KM is ~1 × 104-fold lower. These results suggest that the CBL active site can accommodate the flexible, hydrophobic hexanoyl unit, however at a substantial cost to binding affinity and turnover rate. Based on these results, we conclude that CBL has evolved to target a benzoate substrate, which from the location of its encoding gene within the 4-chlorobenzoate dehalogenation pathway operon (20, 22), we know to be 4-chlorobenzoate. CBL is thus functionally distinct from the acyl-CoA synthetases of primary metabolism and the phenylacetate: CoA ligase of the phenylacetate catabolic pathway.

Table 1.

Steady-state kinetic constants for CBL catalyzed thioesterification of 4-chlorobenzoate analogs in 50 mM K+Hepes (25 °C, pH 7.5) containing 1 mM CoA, 3.5 mM ATP and 15 mM MgCl2 (see Materials and Methods for details). Error limits are derived from the data fitting not from replicate measurements.

| Substrate | kcat (s−1) |

KM (μM) |

kcat/KM (s−1M−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| phenylacetate | 1.9 (± 0.1) × 10−3 | 1.8 (± 0.1) × 103 | 1.1 |

| hexanoate | 1.9 ± 0.1 | 6.3 (± 0.5) × 103 | 3.1 × 102 |

| 4-chlorobenzoate | 9.2 ± 0.2 | 9.3 (± 0.9) × 10−1 | 9.9 × 106 |

| benzoate | 7.5 ± 0.2 | 4.1 (± 0.3) × 102 | 1.8 × 104 |

| 4-fluorobenzoate | 1.01 (± 0.03) × 101 | 4.2 (± 0.4) × 101 | 2.4 × 105 |

| 4-bromobenzoate | 7.0 ± 0.4 | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 6.3 × 106 |

| 4-hydroxybenzoate | 9.9 (± 0.1) × 10−1 | 1.50 (± 0.04) × 103 | 6.6 × 102 |

| 4-nitrobenzoate | 3.4 ± 0.1 | 1.8 (± 0.2) × 102 | 1.9 × 104 |

| 4-methylbenzoate | 6.6 ± 0.2 | 1.8 (± 0.1) × 101 | 3.7 × 105 |

| 4-ethylbenzoate | 3.2 ± 0.1 | 1.1 (± 0.1) × 102 | 2.9 × 104 |

| 4-iodobenzoate | 3.82 ± 0.05 | 2.3 ± 0.1 | 1.7 × 106 |

| 4-methoxybenzoate | 4.6 ± 0.1 | 2.0 (± 0.2) × 102 | 2.3 × 104 |

| 4-cyanobenzoate | 2.90 ± 0.06 | 9.0 (± 0.6) × 101 | 3.2 × 104 |

| 4-trifluoromethylbenzoate | 3.6 ± 0.1 | 3.4 (± 0.4) × 102 | 1.1 × 104 |

| 2-chlorobenzoate | 6.9 ± 0.1 | 3.4 (± 0.2) × 102 | 2.0 × 104 |

| 3-chlorobenzoate | 1.40 (± 0.02) × 10−1 | 8.0 (± 0.5) × 102 | 1.7 × 102 |

| 3,4-dichlorobenzoate | 9.3 (± 0.1) × 10−1 | 4.6 (± 0.1) × 102 | 2.0 × 103 |

| 2,4-dichlorobenzoate | 5.13 (± 0.09) × 10−2 | 1.49 (± 0.09) × 102 | 3.4 × 102 |

| 2-bromobenzoate | 2.76 (± 0.08) × 10−2 | 1.8 (± 0.1) × 103 | 1.5 × 101 |

| 3-bromobenzoate | 1.47 (± 0.02) × 10−2 | 2.6 (± 0.1) × 102 | 5.7 × 101 |

| 3-hydoxybenzoate | 2.1 (± 0.1) × 10−1 | 2.4 (± 0.4) × 103 | 8.9 × 101 |

| 3-methylbenzoate | 4.2 (± 0.2) × 10−1 | 6.0 (± 0.5) × 103 | 7.0 × 101 |

| 3-methoxybenzoate | 7.2 (± 0.7) × 10−1 | 5.3 (± 0.9) × 103 | 1.4 × 102 |

| 2-methylbenzoate | 4.1 (± 0.2) × 10−1 | 1.05 (± 0.09) × 104 | 3.9 × 101 |

| 2-cyanobenzoate | < 1.7 × 10−4 | ||

| 3-cyanobenzoate | < 4.2 × 10−4 | ||

| 3-nitrobenzoate | < 1.0 × 10−4 | ||

| 2-iodobenzoate | < 5.5 × 10−4 | ||

| 3-iodobenzoate | < 1.4 × 10−3 | ||

| 2-methoxybenzoate | < 8.2 × 10−4 | ||

| 2,5-dichlorobenzoate | < 8.6 × 10−4 | ||

| 2,6-dichlorobenzoate | < 1.7 × 10−4 | ||

| 2,3,5-trichlorobenzoate | < 6.0 × 10−4 |

The determination of the substrate specificity towards ring substituted benzoates defines the spatial and electrostatic requirements for the active site and sets the stage for the engineering of this enzyme to accept alternate benzoate substrates. Comparison of the substrate activities of the various para (C4)-, ortho (C2 or C6)- and meta (C3 or C5)-substituted benzoates reveals that CBL catalyzes the thioesterification of a wide range of para-substituted benzoates with varying degrees of efficiency, and that CBL displays very low activity with the ortho- and meta-substituted benzoates (Table 1). These observations can be rationalized within the context of the structure of the 4-chlorobenzoate binding site (Figure 1). Specifically, the C(4)Cl of the bound 4-chlorobenzoate is accommodated by a small hydrophobic binding pocket (hereafter referred to as the “C(4)X pocket”) formed by the Cγ and Cε of the Met310 side chain, the Cβ of the Asn311 side chain and the aromatic ring of Phe184. Substrate discrimination of para-substituted benzoates is therefore based on the compatibility of the size, shape and polarity of the benzoate C(4) substituent with the “C(4)X pocket”. Notably, benzoate itself is a poor substrate. We assume that owing to its small size, the hydrogen atom at C(4) does not fill the C(4)X pocket and consequently, ligand binding affinity and orientation are adversely affected. The majority of the para substituted benzoates tested, however proved to be efficient CBL substrates (kcat/KM > 104 s−1M−1). Among these are the para-halosubstituted benzoates 4-fluorobenzoate, 4-bromobenzoate and 4-iodobenzoate. Remarkably, the electron induction provided by the C(4)F does not appear to strongly impair the reactivity of the ring carboxylate nor does the desolvation of the C(4)F into the hydrophobic pocket prevent binding. Indeed, the kcat/KM of 4-fluorobenzoate, although 50-fold smaller than the kcat/KM measured for 4-chlorobenzoate, is 10-folder greater than the kcat/KM measured for benzoate.

CBL also shows significant activity with 4-nitrobenzoate, 4-methylbenzoate, 4-ethylbenzoate, 4-methoxybenzoate, 4-cyanobenzoate, and 4-trifluoromethylbenzoate. In contrast, the kcat/KM of 4-hydroxybenzoate is ~10,000-fold smaller than that of 4-chlorobenzoate. This reduction may be attributed to strong hydrogen bonding properties of the C(4)OH. Specifically, the loss of the three H-bonds between the C(4)OH and water that will occur upon complex formation is likely to reduce the binding affinity. Moreover, despite the comparatively high nucleophilicity of the 4-hydroxybenzoate carboxylate (owing to electron donation from the ring hydroxyl group), the kcat is also diminished. Because 4-hydroxybenzoate is the end product of the 4-chlorobenzoate dehalogenation pathway (Scheme 1) (22) it is essential that CBL discriminate between it and 4-chlorobenzoate. Clearly, the evolution of CBL has optimized its reactivity with 4-chlorobenzoate while minimizing its reactivity with 4-hydroxybenzoate.

Examination of the steady-state kinetic constants for the ortho- and meta-substituted benzoate substrates reveals that KM is dramatically increased3 and kcat is dramatically decreased. The meta-substituted benzoates 3-chlorobenzoate, 3-bromobenzoate, 3-hydroxybenzoate, 3-methylbenzoate and 3-methoxybenzoate are especially poor substrates as are the ortho-substituted benzoates 2-bromobenzoate and 2-methylbenzoate. The 2-chlorobenzoate shows a modest level of activity: kcat/KM = 2 × 104 M−1 s−1 which is 500-fold lower than the 4-chlorobenzoate kcat/KM value. Given that the differences in size and electronic properties of Cl vs Br are small, it is curious that the kcat/KM value measured for the 2-bromobenzoate is 3-orders of magnitude lower than the 4-chlorobenzoate kcat/KM value. 2-Cyano, 2-iodo, 3-cyano, 3-nitro, 3-iodo, 2-methoxy, 2,5-dichloro, 2,6-dichloro, and 2,3,5-trichlorobenzoate are not substrates for CBL.

Notably, the first target for the engineering, 3,4-dichlorobenzoate displays a modest level of activity: kcat/KM = 2 × 103 M−1 s−1. The second target 3-chlorobenzoate, is much less active: kcat/KM = 1.7 × 102 M−1 s−1. Overall, the kinetic results indicate that the CBL 4-chlorobenzoate binding site fails to accommodate the ortho and meta substituted benzoates in an optimal orientation for reaction. Inspection of the CBL structure shown in Figure 1 reveals limited space (~ 4 Å) between the benzoate ring atoms C(2), C(3), C(5) or C(6) and the walls of the active site. Thus, whereas CBL productively binds a wide range of benzoates substituted at the para-position with small hydrophobic substituents, it discriminates against the corresponding ortho- and meta-substituted benzoates by size-exclusion. The meta-substituted benzoates are especially challenging substrates. Below, we describe the rational redesign of the CBL 4-chlorobenzoate binding pocket for enhanced activity with 3,4-dichlorobenzoate and 3-chlorobenzoate. Both of these chlorinated benzoates are dead-end bi-products of microbial PCB degradation (10). The rational engineering of CBL for thioesterification of 3,4-dichlorobenzoate and 3-chlorobenzoate was carried out to determine whether the 4-chlorobenzoate binding pocket is suitable for redesign to extend substrate range, and to produce novel enzyme catalysts for expanded PCB bioremediation.

Redesign of the CBL 4-Chlorobenzoate Binding Site for Accommodation of a Meta-Chloro Ring Substituent

The CBL substrate specificity profile reported in the previous section shows that the C(4)Cl makes an important contribution to productive binding. For this reason 3,4-dichlorobenzoate rather than 3-chlorobenzoate was selected as our first target for CBL engineering. The 3,4-dichlorobenzoate kcat/KM value of 2 × 103 M−1s−1 is 3-orders of magnitude lower than the kcat/KM value of 4-chlorobenzoate. We can attribute this effect to the meta-Cl substituent, and specifically to the unfavorable steric effects that may be imposed by this substituent. As indicated in Figure 1, the Cδ1 of the Ile303 side chain and the Cγ and Cε of the Met310 side chain come within close contact (~4 Å) of the benzoate ring meta carbons. The larger space required for accommodation of the meta-C(C1) (1.8 Å C-Cl bond vs 1.1 Å C-H bond) will create steric crowding for both orientations of the bound 3,4-dichlorobenzoate ligand. If additional space can be created by replacement of Ile303 or Met310 with an amino acid having a smaller hydrophobic side chain without disruption of the environment of the reaction center, the catalytic efficiency of CBL towards the 3,4-dichlorobenzoate might be enhanced.

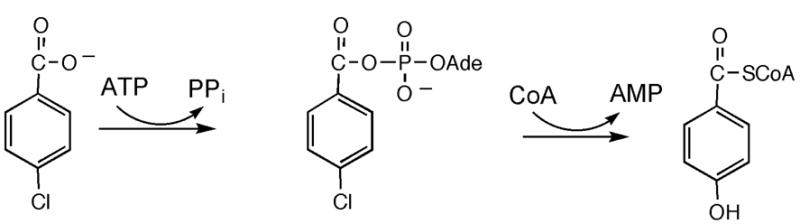

CBL catalysis proceeds via a two-step reaction (Scheme 2) (43). The first step involves the nucleophilic displacement of MgPPi from MgATP by the 4-chlorobenzoate carboxylate to form the 4-chlorobenzoyl-adenylate and the second step involves nucleophilic displacement of AMP from the 4-chlorobenzoyl-adenylate by the thiol of CoA to form the 4-chlorobenzoyl-CoA product. The “centers” of these two reactions are thus located outside of the hydrophobic 4-chlorobenzoate binding pocket shown in Figure 1. Therefore, the replacement of Ile303 or Met310 with a small hydrophobic residue should not impair catalysis unless it destabilizes the catalytic scaffold. Ultimately, we chose Ile303 for amino acid replacement because structure based sequence alignments with other members of the acyl-adenylate forming enzyme superfamily showed that an amino acid as small as Gly is used at this position in some members (for example the coumarate-CoA ligase from Arabidopsis thaliana (44), the FadD fatty acyl-CoA synthetase from E. coli (45) and the long chain fatty acyl-CoA synthetase of Thermus thermophils HB8 (46). Thus, if the CBL Ile303 residue is replaced by Ala or Gly, it is likely that the stability of the protein, and the arrangement of catalytic residues within the active site, might not be affected. We replaced Ile303 with progressively smaller residues to evaluate the activities of the mutant CBLs towards catalysis of 3,4-dichlorobenzoate CoA thioesterification.

Scheme 2.

4-Chlorobenzoate: CoA Ligase Partial Reactions

The steady-state kinetic constants of the purified mutants I303V CBL, I303A CBL and I303G CBL were first measured using 4-chlorobenzoate as substrate so that we could determine the impact of the mutation on the catalytic efficiency with the native substrate (Table 2; the kcat/KM and kcat/KM values measured for ATP and CoA are reported in Table S1 of Supporting Information). Notably, the 4-chlorobenzoate kcat/KM decreases with decreasing size of the side chain at position 303 in the mutants: I303V CBL (2.2 × 106 M−1 s−1; 4.5-fold decrease from wild-type); I303A CBL (6.0 × 105 M−1 s−1; 16.5-fold decrease from wild-type); I303G CBL (3.0 × 105 M−1 s−1; 33-fold decrease from wild-type). The decrease in the value of the respective mutants derives from both a decrease in kcat and an increase in the value of KM. The kcat/KM measured for ATP varied but to a smaller degree and not in a trend: wild-type CBL 9.3 × 104 M−1 s−1; I303V CBL 2.5 × 104 M−1 s−1 (3.7-fold decrease from wild-type); I303A CBL 3.6 × 104 M−1 s−1 (2.6-fold decrease from wild-type); I303G CBL 2.2 × 105 M−1 s−1 (2.4-fold increase from wild-type) (Table S1, Supporting Information). The kcat/KM measured for CoA did not vary significantly: wild-type CBL = 3.0 × 104 M−1 s−1; I303V CBL = 5.1 × 104 M−1 s−1 (1.7-fold increase from wild-type); I303A CBL = 2.1 × 104 M−1 s−1 (1.4-fold decrease from wild-type); I303G CBL = 1.6 × 104 M−1 s−1 (2-fold decrease from wild-type). These results show that structural alteration of the 4-chlorobenzoate binding pocket has the greatest impact on the binding and reaction of the carboxylate substrate (vs the binding and activation of ATP and CoA), as one might expect based on the separation of substrate binding sites observed in the CBL structure.

Table 2.

The steady-state kinetic constants kcat and KM measured for wild-type CBL and I303 CBL mutants in 50 mM K+ Hepes (pH 7.5, 25°C) containing 15 mM MgCl2, and the substrates 3.5 mM ATP, 1 mM CoA and varying concentrations of 4-chlorobenzoate (4-CB), 3-chlorobenzoate (3-CB) or 3,4-dichlorobenzoate (3,4-DCB) (see Materials and Methods for details). Error limits are derived from the data fitting not from replicate measurements.

| 3,4-DCB | (1.8 ± 0.2) × 03 | (5.8 ± 0.3) × 10−2 | 3.2 | |

|

| ||||

| 4-CB | (1.5 ± 0.2) × 103 | (1.9 ± 0.1) × 10−1 | 1.3 × 102 | |

| I303W | 3-CB | 2.35 × 10−4 | ||

| 3,4-DCB | 1.3 × 10−3 | |||

|

| ||||

| 3,4-DCB | (4.6 ± 0.1) × 102 | (9.30 ± 0.08) × 10−1 | 2.0 × 103 | |

|

| ||||

| 4-CB | 1.4 ± 0.1 | 3.03 ± 0.06 | 2.2 × 106 | |

| I303V | 3-CB | (5.7 ± 0.4) × 101 | (2.92 ± 0.07) × 10−2 | 5.1 × 102 |

| 3,4-DCB | (2.0 ± 0.2) × 101 | (5.2 ± 0.2) × 10−1 | 2.5 × 104 | |

|

| ||||

| 4-CB | 2.6 ± 0.3 | 1.54 ± 0.06 | 6.0 × 105 | |

| I303A | 3-CB | (1.25 ± 0.09) × 101 | (1.89 ± 0.04) × 10−2 | 1.5 × 103 |

| 3,4-DCB | 1.8 ± 0.1 | (2.74 ± 0.06) × 10−1 | 1.6 × 105 | |

|

| ||||

| 4-CB | 6.7 ± 0.7 | 2.00 ± 0.07 | 3.0 × 105 | |

| I303G | 3-CB | 9.1 ± 0.3 | (6.49 ± 0.07) × 10−3 | 7.2 × 102 |

| 3,4-DCB | (9.3 ± 0.6) × 10−1 | (1.30 ± 0.03) × 10−1 | 1.4 × 105 | |

|

| ||||

| 4-CB | (9 ± 2) × 102 | (4.5 ± 0.4) × 10−1 | 5.0 × 102 | |

| I303Y | 3-CB | 5.5 × 10−5 | ||

Whereas the binding site of wild-type CBL is expected to be most compatible with 4-chlorobenzoate, the binding site of the CBL I303V, I303A and I303G mutants are expected to be most compatible with 3,4-dichlorobenzoate provided that the meta-C(Cl) fills the space vacated by the Ile303 substitution. As reported in Table 2, the kcat/KM measured with wild-type CBL and 3,4-dichlorobenzoate is 2.0 × 103 M−1 s−1, the kcat/KM value measured for I303V CBL is 2.5 × 104 M−1 s−1 (12.5-fold increase from wild-type), for I303A CBL is 1.6 × 105 M−1 s−1 (80-fold increase from wild-type) and for I303G CBL is 1.4 × 105 M−1 s−1 (70-fold increase from wild-type). In contrast, the kcat decreased, but only to a comparatively small degree, with decreasing side chain size (wild-type CBL 0.93 s−1: I303V CBL 1.8–fold smaller; I303A CBL 3.4–fold smaller; I303G CBL 7.2–fold smaller). The observation that the kcat values measured with the 4-chlorobenzoate substrate and the mutant CBLs are similarly diminished (wild-type CBL 9.2 s−1: I303V CBL 3.0–fold smaller; I303A CBL 6.0–fold smaller; I303G CBL 4.6–fold smaller), is indicative of a small perturbation that is not substrate specific.

It is noteworthy that the increase in the kcat/KM towards the 3,4-dichlorobenzoate substrate gained by the Ile303 substitution is not based on the increase in kcat but rather on the large decrease in the KM (wild-type CBL 460 μM: I303V CBL 23–fold smaller; I303A CBL 256–fold smaller; I303G CBL 495–fold smaller) (Table 2). 3-Bromobenzoate, 3-methylbenzoate and 3-hydroxybenzoate also displayed increased kcat/KM values (~10-fold) with the I303A CBL vs wild-type CBAL as a result of decreased KM (Table S2 Supporting Information). For 3-methoxybenzoate the increase was only 2-fold. 3-Cyanobenzoate, which did not show detectable substrate activity with wild-type CBL was discovered to have a kcat/KM = 1.1 × 102 M−1 s−1 (Table S2 Supporting Information).

We found that the replacement of the Ile303 with Tyr or Trp greatly diminishes the catalytic efficiency of 4-chlorobenzoate thioesterification, and prevents the 3,4-dichlorobenzoate thioesterification (Table 2). Whereas the KM for 4-chlorobenzoate was increased ~10,000-fold, the KM values of ATP and CoA were increased by only 2-10-fold (Table S1 Supporting Information). Thus, the impact of spatial requirements of the substituted aromatic residues is restricted to 4-chlorobenzoate binding and does not extend to the other substrate binding sites.

We conclude that the hydrophobic CBL 4-chlorobenzoate binding site directs substrate specificity by size exclusion. Moreover, the working hypothesis is that the decrease observed in the 3,4-dichlorobenzoate KM with the I303V, I303A and I303G CBL mutants is the direct result of providing a “space” for the meta-C(Cl).

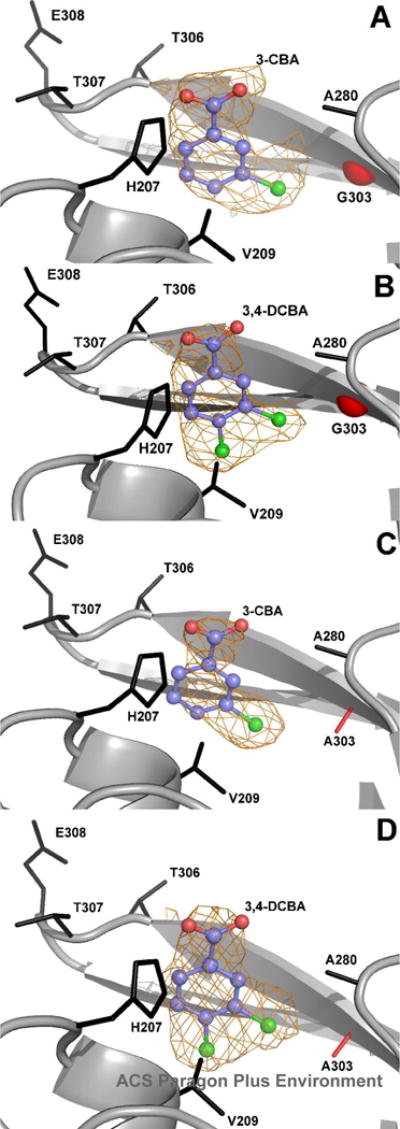

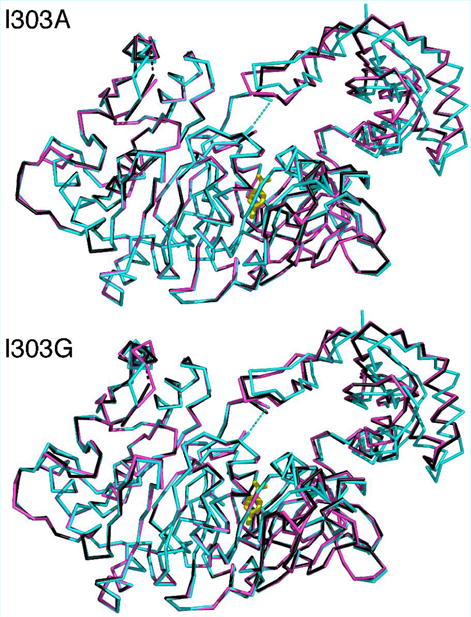

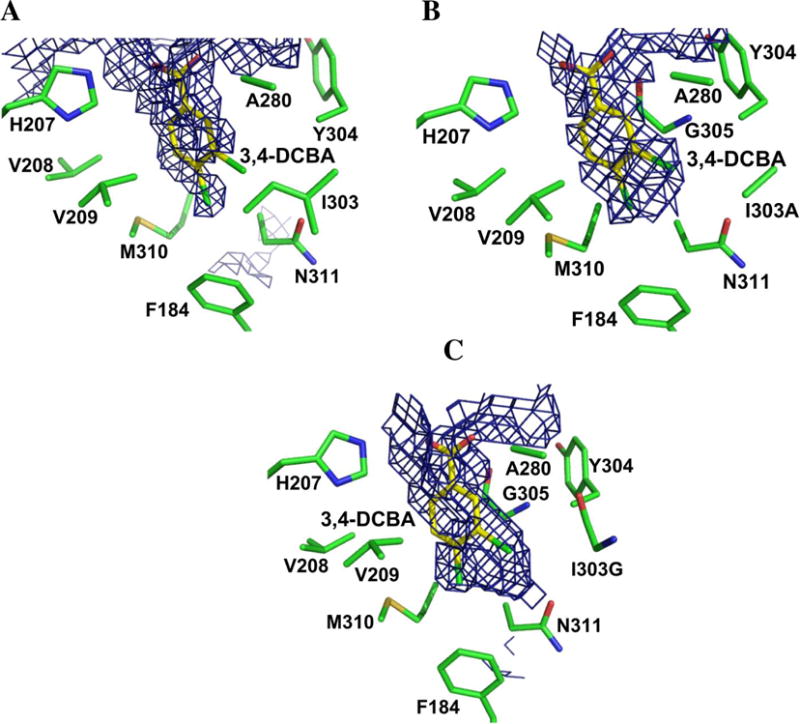

Structure Determination of CBL I303A and I303G Complexed with 3,4-Dichlorobenzoate

The X-ray crystal structures of the CBL 1303A and I303G mutants complexed with 3,4-dichlorobenzoate were determined to test our hypothesis. The crystallographic and refinement statistics are presented in Table 3. The electron density maps of the ligand binding sites are shown in Figure 2 and the superposition of the mutant structures with the wild-type CBL-4-chlorobenzoate complex (PDB: 1T5H) is shown in Figure 3. The structural overlay demonstrates that the mutant proteins adopt a very similar conformation to that of the wild-type CBL enzyme. In particular, the C-terminal domain, which has been observed in multiple orientations for different members of the adenylateforming family, assumes the same conformation as that of the wild-type enzyme. The rms deviations for Cα atoms is 0.7 Å for all atoms of the N-terminal domain and 1.0 Å for the full-length structures. The C-terminal Ser504 is missing from the structures, as was found with the wild-type CBAL in complex with 4-chlorobenzoate. In addition, the Gly- and Ser/Thr-rich loop near the active site is disordered. This disorder was also observed in the wild-type CBL structures as well as in the structures of several other members of this enzyme superfamily. A second surface loop (residues 109–112) is also poorly ordered.

Table 3.

Crystallographic and refinement data for crystals of the CBL Ile303A and I303G mutant proteins complexed with 3-chlorobenzoate (3-CB) and 3,4 dichlorobenzoate (3,4-DCB).

| I303G – 3-CB | I303G – 3,4-DCB | I303A – 3-CB | I303A – 3,4-DCB | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resolution | 30 – 2.70 Å | 30 – 2.76 Å | 30 – 2.50 Å | 30 – 2.56 Å |

| Space Group | P3221 | P3221 | P3221 | P3221 |

| Unit Cell | a=b= 127.9 | a=b= 127.8 | a=b= 127.9 | a=b= 128.1 |

| c= 71.5 | c= 71.4 | c= 71.4 | c= 71.7 | |

| Rmergea | 4.8% (40.0%) | 8.8% (52.5%) | 4.8% (32.0%) | 5.3% (39.7%) |

| Completenessa | 96.9% (98.9%) | 99.5% (99.9%) | 92.8% (100%) | 90.5% (99.4%) |

| I/σa | 15.0 (2.1) | 11.5 (1.8) | 18.4 (2.2) | 12.5 (1.9) |

| # Observations | 116608 | 109519 | 105784 | 81217 |

| # Reflections | 44023 | 20899 | 47472 | 46521 |

| Rcrysta | 18.8% (32.8%) | 19.1% (29.5%) | 19.3% (24.4%) | 18.5% (28.3%) |

| Rfreea | 27.1% (43.4%) | 25.7% (40.0%) | 26.6% (35.7%) | 25.3% (41.7%) |

| Wilson B-factor | 78.0 Å2 | 76.4 Å2 | 64.8 Å2 | 64.5 Å2 |

| Average B-factor (all atoms) | 47.3 Å2 | 58.0 Å2 | 62.0 Å2 | 56.8 Å2 |

| Average B-factor (N-term)b | 47.8 Å2 | 58.2 Å2 | 62.0 Å2 | 56.7 Å2 |

| Average B-factor (C-term)b | 44.9 Å2 | 58.0 Å2 | 62.4 Å2 | 57.8 Å2 |

| Average B-factor (Solvent) | 54.2 Å2 | 48.6 Å2 | 59.4 Å2 | 51.5 Å2 |

| Solvent Molecules | 31 | 25 | 137 | 107 |

| Average B-factor (Ligand) | 55.1 Å2 | 53.8 Å2 | 53.3 Å2 | 52.6 Å2 |

| rms deviations (lengths, angles) | .014 Å, 1.59° | .016 Å, 1.69° | .013 Å, 1.38° | .013 Å, 1.43° |

Values in parentheses represent statistics for the highest resolution shell.

Figure 2.

Electron density of ligands bound to Ile303 mutants. Unbiased ligand density is shown for: (A) 3-chlorobenzoate (3-CB) bound to I303G CBL. (B) 3,4-dichlorobenzoate (3,4-DCB) bound to I303G CBL. (C) 3-chlorobenzoate (3-CB) to I303A CBL. (D) 3,4-dichlorobenzoate (3,4-DCB) bound to I303A CBL. The electron density maps were calculated with coefficients of the form Fo-Fc determined prior to inclusion of the ligand into the refinement. The maps are contoured at 2.5 σ. Side chains of neighboring residues are labeled. The mutant residues are shown in red. The red sphere in panels A and B represents the Cα position of the CBL Gly303 mutant residue.

Figure 3.

Superposition of the main chain carbons of wild-type CBL structure (1T5D) with the A. I303A mutant protein structures and the B. I303G mutants. In both panels, the wild-type structure is shown in blue, with the 4-chlorobenzoate ligand shown in stick representation in yellow. The mutant proteins are shown bound to 3,4-dichlorobenzoate (black) and bound to 3-chlorobenzoate (pink). The two disordered loops at residues 109–111 and at 162–165 are shown with dashed lines. For clarity, only a single ligand is shown in the active site.

The superposition of the residues of the 4-chlorobenzoate binding pocket of the wild-type CBL-4-chlorobenzoate complex and the residues of the 4-chlorobenzoate binding pocket of the CBL I303A(3,4-dichlorobenzoate) complex is shown in stereo in Figure 4A. Within the limits imposed by the structural resolution (2.2 Å and 2.6 Å, respectively) the positioning of the binding site residues and the benzoate ligand carboxylate group appear to be unchanged in the mutant complex. Thus, the 3,4-dichlorobenzoate is bound in the correct orientation for reaction in the I303A CBL active site. We also observed that the C(4)Cl of the 3,4-dichlorobenzoate bound to the CBL I303G mutant fills the C(4)X pocket (see Figure S1A Supporting Information). The distance from the C(3)Cl to the Ala Cβ in the mutant is 3.4 Å. By modeling the 3,4-dichlorobenzoate to fit within the 4-chlorobenzoate binding site of the wild-type CBL, and displaying a van der Waals surface on the ligand, we found that a potential steric overlap between the wild-type Ile303 side chain and the C(3)Cl exists. The distance from the C(3)Cl to the Cδ1 or the Cγ1 atoms of Ile303 is only 2.3 Å.

Figure 4.

Superposition of the wild-type CBAL-4-chlorobenzoate complex with the residues of the 4-chorobenzoate binding pocket of the A. I303A CBL-3,4-dichlorobenzoate complex and the B. I303A CBL-3-chlorobenzoate complex. All protein atoms from the wild-type structure (1T5D) are shown in black, while for the mutant structures, carbon atoms are shown in yellow, oxygen atoms are shown red, nitrogen atoms are blue, sulfur atoms are orange, and chloride atoms are green. A van der Waals surface is shown on the ligand from the mutant structure

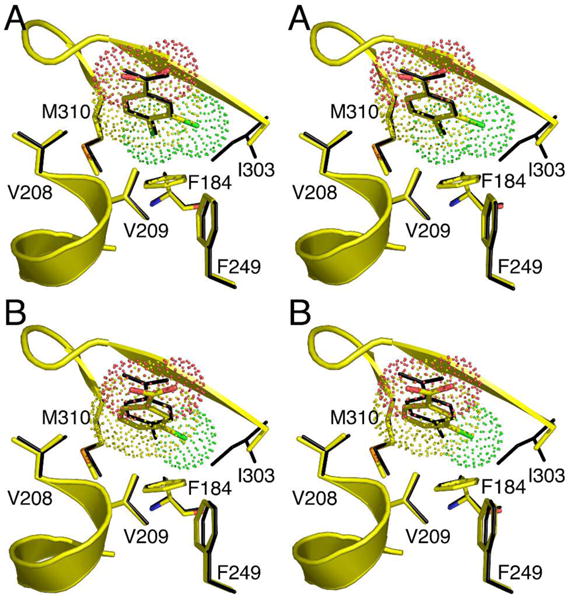

The orientation of 3,4-dichlorobenzoate is such that the C(5)H is directed at the Met310 and the C(3)Cl is directed at Ala303 (or the Gly of I303G). This orientation is true to the design. To most easily visualize the actual changes in the topology of the binding site that accommodate the ligand in this orientation, the program VOIDOO (47) was used to create a solvent cage (hereafter referred to as the “ligand cage”) that depicts the three-dimensional space available to the ligand. Figure 5A illustrates the accessible ligand cage of the wild-type enzyme. Into this cage we “add back” the 3,4-dichlorobenzoate ligand as it is defined by the I303A CBL(3,4-dichlorobenzoate) complex structure. The C(3)Cl extends outside this cage, consistent with the modest catalytic efficiency of the enzyme towards 3,4-dichlorobenzoate (reported in Table 1). Figure 5B and 5C show the ligand cages of the CBL I303A and I303G mutants generated from the X-ray structures of the I303A and I303G CBL complexes of 3,4-dichlorobenzoate. It is evident from these figures that the 3,4-dichlorobenzoate C(3)Cl is accommodated within the “extra” space provided by the truncation of I303.

Figure 5.

(A) The wild-type CBL-4-chlorobenzoate complex (PDB: 1T5H) with ligand cage. The 3,4-dichlorobenzoate was modeled in place of the 4-chlorobenzoate. (B) The I303A CBL-3,4-dichlorobenzoate complex with ligand cage. (C) The I303G CBL-3,4-dichlorobenzoate complex with ligand cage. Figures were generated from the X-ray structure coordinates of the respective complexes using the graphics program VOIDOO (47).

This finding validates the strategy used for the rational redesign of the 4-chlorobenzoate binding pocket for expanded substrate range. The structures show that the needed space was created in the I303 mutants, allowing the enzyme to act on a novel substrate, without reduction in protein stability or significant impairment of the functioning of the catalytic scaffold. Having achieved this objective, the next step was to engineer the 4-chlorobenzoate binding site so that the requirement for a C(4)Cl to fill the C(4)X pocket is eliminated. This work is described in the following section.

Activity Analysis and Structure Determination of 3-Dichlorobenzoate Complexes of CBL I303A and I303G Mutants

The low substrate activity observed with benzoate is a clear indication that the C(4)Cl of the native substrate 4-chlorobenzoate is needed for efficient binding and turnover. Based on the X-ray structure of the wild-type CBL-4-chlorobenzoate complex (Figure 1) we surmised that the C(4)Cl locks the ring in place by filling the C(4)X hydrophobic pocket. 3-Chlorobenzoate has too much steric bulk at C(3) and too little steric bulk at C(4). Indeed, the kcat/KM value measured with 3-chlorobenzoate and wild-type CBL is quite low: 1.7 × 102 M−1 s−1 (10,000-fold lower than that of 4-chlorobenzoate and 10-fold lower than that of 3,4-dichlorobenzoate; Table 1). While the Ala and Gly replacements of I303 increased the 3,4-dichlorobenzoate kcat/KM value ~100-fold, the 3-chlorobenzoate kcat/KM value is increased only ~10-fold. The 3-chlorobenzoate kcat/KM value measured for the four mutants are: I303V CBL (5.1 × 102 M−1 s−1; 3-fold increase from wild-type); I303A CBL (1.5 × 103 M−1 s−1; 8.8-fold increase from wild-type); I303G CBL (7.2 × 102 M−1 s−1; 4.2-fold increase from wild-type). The decrease observed in KM for 3-chlorobenzoate (wild-type CBL 800 μM; I303V CBL 14–fold smaller; I303A CBL 64–fold smaller; I303G CBL 88–fold smaller) is partially offset by the decrease in kcat (wild-type CBL 0.136 s−1; I303V CBL 4.7–fold smaller; I303A CBL 7.2–fold smaller; I303G CBL 21–fold smaller).

The decreased 3-chlorobenzoate KM values suggest that increased binding affinity occurs with the decreasing size of the I303 side chain, consistent with the results obtained with 3,4-dichlorobenzoate. However, the absence of the C(4)Cl to fill the C(4)X pocket may lead to nonproductive binding of the 3-chlorobenzoate. To test this hypothesis the X-ray structures of the CBL I303A and I303G mutants complexed with 3-chlorobenzoate were determined. The electron density maps are shown in Figure 2 and the crystallographic and refinement statistics are presented in Table 3. The only significant difference between these structures and those reported in the previous section for the 3,4-dichlorobenzoate complexes of CBL I303A and I303G is the position of the ligand within the 4-chlorobenzoate binding pocket. Figure 4B shows the superposition of wild-type enzyme and the I303A mutant bound to 3-chlorobenzoate. A superposition of the wildtype enzyme with the I303G mutant is shown in Figure S1 of Supporting Information. It is evident from these structures that the 3-chlorobenzoate ligand is positioned too deep within the 4-chlorobenzoate binding pocket. We concluded that this is because the C(4)H is not able to adequately fill the C(4)X pocket as needed to lock the ring in a productive binding orientation. In both mutants, the 3-chlorobenzoate carboxylate group is positioned 0.7 Å below the position of the carboxylate group of the 3,4-dichlorobenzoate or the 4-chlorobenzoate carboxylate group observed in the wild-type CBL (4-chlorobenzoate) complex.

Design of CBL Variants with Improved 3-Clorobenzoate Conversion Rates

To increase CBL activity with 3-chlorobenzoate we carried out site directed mutagenesis, replacing the residues that form the C(4)X binding pocket with larger amino acids. Residues Phe184, Asn311 and Met310 were identified as the nearest neighbors to the substrate C(4)Cl (Figure 1). The I303A CBL mutant was used as the starting point for the C(4)X pocket engineering. Phe184, Asn311 and Met310 were separately replaced with amino acids having slightly greater steric bulk (see list of mutants tested in Table 4). The use of “natural” amino acids placed a severe limitation on the remodeling. Nevertheless, in silico models generated for the planned mutants suggested that a small yet possibly significant decrease in the size of the C(4)X pocket might be achieved. At this stage we are most interested in proof of concept. In particular, the issue to be addressed is whether the plasticity of the site is sufficient to adapt to the steric and electrostatic perturbations introduced by the restructuring of the C(4)X pocket.

Table 4.

The steady-state kinetic constants measured for wild-type CBL and CBL mutant catalysis of 3-chlorobenzoate thioesterification in reaction solutions containing 3.5 mM ATP, 1 mM CoA and 15 mM MgCl2 and 50 mM K+ Hepes (pH 7.5, 25°C) (see Material and Methods for details). Error limits are derived from the data fitting not from replicate measurements.

| CBAL Variant | Km (μM) | kcat (s−1) | kcat/KM (s−1M−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| W.T | (8.0 ± 0.5) × 102 | (1.36 ± 0.02) × 10−1 | 1.7 × 102 |

| I303A | (1.25 ± 0.09) × 101 | (1.89 ± 0.04) × 10−2 | 1.5 × 103 |

| N311H/I303A | (3.35 ± 0.05) × 102 | (2.64 ± 0.01) × 10−2 | 7.9 × 101 |

| N311Q/I303A | 5.9 ± 0.3 | (2.15 ± 0.03) × 10−2 | 3.6 × 103 |

| N311T/I303A | (3.1 ± 0.3) × 102 | (2.19 ± 0.07) × 10−1 | 7.1 × 102 |

| F184W/I303A | (1.40 ± 0.7) × 10 | (7.5 ± 0.1) × 10−2 | 5.4 × 103 |

| F184Y/I303A | (2.3 ± 0.1) × 10 | (5.39 ± 0.06) × 10−3 | 2.3 × 102 |

| F184W/I303A/N311Q | 7.2 ± 0.8 | (3.2 ± 0.1) × 10−2 | 4.4 × 103 |

| M310L/I303A | N.D.a | 2.0 × 10−3 | N.D.a |

| M310I/I303A | N.D.a | 7.8 × 10−3 | N.D.a |

| V209Y/I303A | N.D.a | 2.1 × 10−3 | N.D.a |

| V209W/I303A | N.D.a | 1.7 × 10−3 | N.D.a |

| V209T/I303A | (3.0 ± 0.2) × 10 | (7.1 ± 0.2) × 10−2 | 2.4 × 103 |

| V208Q/I303A | (2.0 ± 0.3) × 102 | (1.65 ± 0.05) × 10−3 | 8.3 |

| F184W/I303A/V209T | 11.1 ± 0.8 | (1.01 ± 0.01) × 10−1 | 9.1 × 103 |

N.D. Abbreviation for not determined.

For the 3-chlorobenzoate thioesterification catalyzed by F184W/I303A CBL the kcat/KM = 5.4 × 103 M−1 s−1 (Table 4). This represents a 32-fold increase in efficiency relative to wild-type CBL and a 4-fold increase relative to the I303A CBL mutant. In contrast, the kcat/KM = 2.3 × 102 M−1 s−1 measured with 3-chlorobenzoate and F184Y/I303A CBL is 6.5-fold smaller than that measured for I303A CBL. The KM values measured for ATP and CoA (Table S4 of Supporting Information) for these two mutants (and the mutants described below) are not significantly different from those measured with wild-type CBL. Thus, the impact of the amino acid substitutions appears to be limited to the 4-chlorobenzoate binding site.

Next, CBL M310 and N311 mutants were examined. Unfortunately, only the N311Q/I303A mutant displayed enhanced enzyme catalytic activity relative to the I303A single mutation (Table 4). The kcat/KM measured with 3-chlorobenzoate and N311Q/I303A CBAL is 3.6 × 103 M−1 s−1 which corresponds to a 2.4-fold increase from I303A. This is largely a KM effect. The kcat/KM values measured for N311H/I303A and N311T/I303A are smaller than that of I303A (19-fold and 2-fold, respectively). Although the kcat values of these two N311 double mutants are increased over that of CBL I303A (1.4-fold increase with N311H/I303A and 12-fold increase with N311T/I303A), the increased KM values (27-fold and 25-fold, respectively) counter the kcat effect. Lastly, the triple mutant F184W/N311Q/I303A was prepared to determine whether these three site mutations would have an additive effect on catalytic efficiency. The triple mutant is more active than the double mutant N311Q/I303A but not as active as the double mutant F184W/I303A.

The CBL mutants V209Y/I303A and V209W/I303A are not active with 3-chlorobenzoate (Table 4). In contrast, V209T/I303A CBL displayed a kcat of 0.071 s−1, 3.8-fold larger than the kcat of I303A. However, the KM is also increased. The CBL triple mutant F184W/I303A/V209T on the other hand displayed a kcat/KM = 9.1 × 103 M−1s−1 with 3-chlorobenzoate. This represents a 54-fold increase over the kcat/KM of wild-type CBL. The F184W/I303A/N311Q mutant displayed a kcat/KM = 4. × 103 M−1s−1 with 3-chlorobenzoate (27-fold increase over wild-type).

The F184W/I303A/V209T CBL is the most active mutant with 3-chlorobenzoate serving as the substrate. However, compared to the I303A CBL which was used as the starting point for engineering the C(4)Cl pocket, F184W/I303A/V209T CBL is only 6-fold more active. Thus, the replacement of the pocket residues with residues achieved the desired affect, but overall the observed rate enhancement is modest. This suggests that the positions of the main chain segments that frame the C(4)Cl pocket should be targeted for engineering a closed pocket. In future work, this alternative will be explored.

Summary and Conclusion

The present studies show that the 4-chlorobenzoate binding site has evolved to function within the 4-chlorobenzoate pathway (Scheme 1). The high kcat/KM for 4-chlorobenzoate contrasted with the low kcat/KM for the pathway product 4-hydroxybenzoate evidences an effective mechanism for substrate discrimination. The substrate specificity profile analyzed in the context of the CBL(4-chlorobenzoate) structure suggested that the substrate binding affinity and the orientation of the substrate carboxylate group for reaction is controlled by two distinct properties of the binding pocket. One property is hydrophobicity and the other is “lock-in-key” topological complementation. The addition of nonpolar ring substituents at the ortho or meta positions of the substrate is not well tolerated because of the steric hindrance that taxes binding affinity. The substitution of the para-C(Cl) with substituents of similar size and hydrophobicity is well tolerated because these substituents are able to fill the para-C(Cl) subpocket at the bottom of the binding site and by doing so lock the ring in the correct position for alignment of the carboxylate group for attack at the α-P of the bound ATP (Scheme 2).

In contrast, benzoates that do not posses a C(4) substituent of adequate size will “sink” into the pocket and the ring carboxylate will be poorly oriented for reaction. The replacement of the 4-chlorobenzoate binding pocket residue Ile303 with Ala created adequate space for the accommodation of the C(3)Cl (meta) of the 3,4-dichorobenzoate and increased the kcat/KM from 2.0 × 103 M−1 s−1 to 1.6 × 105 M−1 s−1. The attempted reconstruction of the CBL C(4)Cl subpocket to prop the 3-chlorobenzoate within the binding site of the I303A CBL mutant was only modestly successful owing the limitation of the structural changes that could be made at this site using natural amino acids. It is likely that substitutions made at the second sphere of binding site residues via focused random-mutagenesis (30, 34) could be employed to further constrict the C(4) pocket for optimized activity with 3-chlorobenzoate.

Overall, this work shows that CBL has excellent potential as a catalytic platform for the rational design of CoA thioesterification catalysts for use in activation of aromatic acids for bioremediation applications. Moreover, in a recent publication Smith and coworkers (48) reported that a Trp to Gly replacement within acetate-binding site in acetyl-CoA synthetase switches preference for acetate to preference for valerate. Thus, the acyl-adenylate forming enzyme superfamily may serve as a rich source of designer catalysts for the synthesis of acyl-CoA thioesters. For those family members that participate in nonribosomal peptide antibiotic synthetic pathways (49–51), engineering substrate specificity may lead to the development of novel antibiotics.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

This work was supported by NIH Grant GM28688 to D.D.-M. and by NIH grant GM-068440 to A. M. G.. Protein structure determinations were carried out at the Cornell High Energy Synchrotron Source (CHESS) which is supported by the National Science Foundation under award DMR 0225180 and the National Institutes of Health through its National Center for Research Resources under award 5 P41 RR001646-23R.W., J. C. and D. D-M contributed the biochemical studies and A. S. R. and A. M. G contributed the X-ray structure analyses.

The atomic coordinates and structure factors four structures have been deposited with the Protein Data Bank: 4-chlorobenzoate: CoA ligase I303A bound to 3-chlorobenzoate (2QVZ) and to 3,4-dichlorobenzoate (2QWO) and 4-chlorobenzoate: CoA ligase I303G bound to 3-chlorobenzoate and to 3,4-dichlorobenzoate (2QVY).

Abbreviations used are: polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT), coenzyme A (CoA), 4-chlorobenzoate: CoA ligase (CBL), 4-chlorobenzoyl-adenosine-5′-monophosphate (4-CB-AMP), inorganic pyrophosphate (PPi), adenosine-5-triphosphate (ATP), adenosine-5-monophosphate (AMP), β-nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH), phosphoenol pyruvate (PEP); phenylacetate (PA), 4-chlorobenzoate (4-CB), 3-chlorobenzoate (3-CB), 3,4-dichlorobenzoate (3,4-DCB), dithiothreitol (DTT), potassium salt of N-(2-hydroxyethyl)piperzine-N′-2-ethanesulfonate (K+Hepes), sodium dodecylsulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE),

There are few reports in the literature of the characterization of purified aromatic acid ligases in general and recombinant aromatic ligases in particular. In our hands, the yield of recombinant 4-chlorobenzoate: CoA ligase derived from 4-chlorobenzoate degrading Pseudomonas and Arthrobacter strains using E. coli clones as the overexpression system, is low and the activity of the purified ligase is unstable. We have met with limited or no success with the isolation of active recombinant bacterial phenylacetate: CoA ligase, benzoate: CoA ligase or aminobenzoate: CoA ligase. The reason(s) for this undesirable behavior is not clear.

Throughout this manuscript changes in the KM are related to changes in substrate binding affinity. It is well known that only in cases where rapid-equilibrium binding prevails is the KM equivalent to the dissociation constant of the enzyme-substrate complex. Thus, in this context we use the change in KM is an indicator and not as a quantitative measure of change in binding affinity.

Supporting Information. Tables of steady-state kinetic constants and a figure of I303G CBL ligand complexes are included. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.De Voogt P, Wells DE, Reutergardh L, Brinkman U. Biological activity, determination, and occurrence of planar, mono- and di-ortho PCBs. Int J Anal Chem. 1990;40:1–46. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Safe S. Toxicology, structure-function relationship, and human and environmental health impacts of polychlorinated biphenyls: progress and problem. Environ Health Perspect. 1992;100:259–268. doi: 10.1289/ehp.93100259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Faroon O, Jones D, de Rosa C. Effects of polychlorinated biphenyls on the nervous system. Toxicol Ind Health. 2001;16:305–333. doi: 10.1177/074823370001600708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aoki Y. Polychlorinated biphenyls, polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins, and polychlorinated dibenzofurans as endocrine disrupters–what we have learned from Yusho disease. Environ Res. 2001;86:2–11. doi: 10.1006/enrs.2001.4244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Faroon OM, Keith S, Jones D, De Rosa C. Carcinogenic effects of polychlorinated biphenyls. Toxicol Ind Health. 2001;17:41–62. doi: 10.1191/0748233701th098oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Faroon OM, Keith LS, Williams M, Murray HE, Jones DE, De Rosa CT. Comments on “Potential human cancer risks from exposure to PCBs: a tale of two evaluations”. Crit Rev Toxicol. 2004;34:499–501. doi: 10.1080/10408440490519803. author reply 503–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guo YL, Lambert GH, Hsu CC, Hsu MM. Yucheng: health effects of prenatal exposure to polychlorinated biphenyls and dibenzofurans. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2004;77:153–158. doi: 10.1007/s00420-003-0487-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haggblom MM. Microbial breakdown of halogenated aromatic pesticides and related compounds. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1992;9:29–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1992.tb05823.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Higson FK. Microbial degradation of biphenyl and its derivatives. Adv Appl Microbiol. 1992;37:135–164. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2164(08)70254-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pieper DH. Aerobic degradation of polychlorinated biphenyls. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2005;67:170–191. doi: 10.1007/s00253-004-1810-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rodrigues JL, Kachel CA, Aiello MR, Quensen JF, Maltseva OV, Tsoi TV, Tiedje JM. Degradation of aroclor 1242 dechlorination products in sediments by Burkholderia xenovorans LB400(ohb) and Rhodococcus sp. strain RHA1(fcb) Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72:2476–2482. doi: 10.1128/AEM.72.4.2476-2482.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nishi A, Tominaga K, Furukawa K. A 90-kilobase conjugative chromosomal element coding for biphenyl and salicylate catabolism in Pseudomonas putida KF715. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:1949–1955. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.7.1949-1955.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Toussaint A, Merlin C, Monchy S, Benotmane MA, Leplae R, Mergeay M, Springael D. The biphenyl- and 4-chlorobiphenyl-catabolic transposon Tn4371, a member of a new family of genomic islands related to IncP and Ti plasmids. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2003;69:4837–4845. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.8.4837-4845.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Furukawa K, Miyazaki T. Cloning of a gene cluster encoding biphenyl and chlorobiphenyl degradation in Pseudomonas pseudoalcaligenes. J Bacteriol. 1986;166:392–398. doi: 10.1128/jb.166.2.392-398.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hayase N, Taira K, Furukawa K. Pseudomonas putida KF715 bphABCD operon encoding biphenyl and polychlorinated biphenyl degradation: cloning, analysis, and expression in soil bacteria. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:1160–1164. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.2.1160-1164.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kosono S, Maeda M, Fuji F, Arai H, Kudo T. Three of the seven bphC genes of Rhodococcus erythropolis TA421, isolated from a termite ecosystem, are located on an indigenous plasmid associated with biphenyl degradation. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:3282–3285. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.8.3282-3285.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Masai E, Sugiyama K, Iwashita N, Shimizu S, Hauschild JE, Hatta T, Kimbara K, Yano K, Fukuda M. The bphDEF meta-cleavage pathway genes involved in biphenyl/polychlorinated biphenyl degradation are located on a linear plasmid and separated from the initial bphACB genes in Rhodococcus sp. strain RHA1. Gene. 1997;187:141–149. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(96)00748-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kong HL, Sayler GS. Degradation and total mineralization of monohalogenated biphenyls in natural sediment and mixed bacterial culture. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1983;46:666–672. doi: 10.1128/aem.46.3.666-672.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Layton AC, Sanseverino J, Wallace W, Corcoran C, Sayler GS. Evidence for 4-chlorobenzoic acid dehalogenation mediated by plasmids related to pSS50. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:399–402. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.1.399-402.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lai Su-Yuan, W-h Z, Wu Rui, Wei Yansheng, Lu Xuefeng, Layton Alice C, Sayler Gary S, Dunaway-Mariano* Debra. The Plasmid pSS70 Encoded 4-Chlorobenzoate Pathway of the 4-Chlorinated Biphenyl-Degrader Alcaligenes sp. Strain ALP83#. submitted for publication. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lai SY. PhD Thesis. University of Maryland; 1996. Characterization of the genes encoding the enzymes of the 4-chlorobenzoate degradation pathway in Alcaligenes sp strain AL3007; pp. 1–307. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dunaway-Mariano D, Babbitt PC. On the origins and functions of the enzymes of the 4-chlorobenzoate to 4-hydroxybenzoate converting pathway. Biodegradation. 1994;5:259–276. doi: 10.1007/BF00696464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ismail W, El-Said Mohamed M, Wanner BL, Datsenko KA, Eisenreich W, Rohdich F, Bacher A, Fuchs G. Functional genomics by NMR spectroscopy. Phenylacetate catabolism in Escherichia coli. Eur J Biochem. 2003;270:3047–3054. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2003.03683.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gescher J, Eisenreich W, Worth J, Bacher A, Fuchs G. Aerobic benzoyl-CoA catabolic pathway in Azoarcus evansii: studies on the non-oxygenolytic ring cleavage enzyme. Mol Microbiol. 2005;56:1586–1600. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04637.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Merkel SM, Eberhard AE, Gibson J, Harwood CS. Involvement of coenzyme A thioesters in anaerobic metabolism of 4-hydroxybenzoate by Rhodopseudomonas palustris. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:1–7. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.1.1-7.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chang KH, Liang PH, Beck W, Scholten JD, Dunaway-Mariano D. Isolation and characterization of the three polypeptide components of 4-chlorobenzoate dehalogenase from Pseudomonas sp. strain CBS-3. Biochemistry. 1992;31:5605–5610. doi: 10.1021/bi00139a025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gulick AM, Lu X, Dunaway-Mariano D. Crystal structure of 4-chlorobenzoate:CoA ligase/synthetase in the unliganded and aryl substrate-bound states. Biochemistry. 2004;43:8670–8679. doi: 10.1021/bi049384m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vopel S, Muhlbach H, Skerra A. Rational engineering of a fluorescein-binding anticalin for improved ligand affinity. Biol Chem. 2005;386:1097–1104. doi: 10.1515/BC.2005.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ema T, Fujii T, Ozaki M, Korenaga T, Sakai T. Rational control of enantioselectivity of lipase by site-directed mutagenesis based on the mechanism. Chem Commun (Camb) 2005:4650–4651. doi: 10.1039/b508244g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chica RA, Doucet N, Pelletier JN. Semi-rational approaches to engineering enzyme activity: combining the benefits of directed evolution and rational design. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2005;16:378–384. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2005.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Magnusson AO, Takwa M, Hamberg A, Hult K. An S-selective lipase was created by rational redesign and the enantioselectivity increased with temperature. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2005;44:4582–4585. doi: 10.1002/anie.200500971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Magnusson AO, Rotticci-Mulder JC, Santagostino A, Hult K. Creating space for large secondary alcohols by rational redesign of Candida antarctica lipase B. Chembiochem. 2005;6:1051–1056. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200400410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Antikainen NM, Martin SF. Altering protein specificity: techniques and applications. Bioorg Med Chem. 2005;13:2701–2716. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2005.01.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leisola M, Turunen O. Protein engineering: opportunities and challenges. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2007;75:1225–1232. doi: 10.1007/s00253-007-0964-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nowlan C, Li Y, Hermann JC, Evans T, Carpenter J, Ghanem E, Shoichet BK, Raushel FM. Resolution of chiral phosphate, phosphonate, and phosphinate esters by an enantioselective enzyme library. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:15892–15902. doi: 10.1021/ja0658618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gulick AM, Horswill AR, Thoden JB, Escalante-Semerena JC, Rayment I. Pentaerythritol propoxylate: a new crystallization agent and cryoprotectant induces crystal growth of 2-methylcitrate dehydratase. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2002;58:306–309. doi: 10.1107/s0907444901018832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Otwinowski Z, M W. Processing of X-ray Diffraction Data Collected in Oscillation Mode. Methods Enzymol. 1997;276:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vagin A, Teplyakov A. MOLREP: an automated program for molecular replacement. J Appl Crystallography. 1997;30:1022–1025. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Murshudov GN, Vagin AA, Dodson EJ. Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1997;53:240–255. doi: 10.1107/S0907444996012255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Winn MD, Isupov MN, Murshudov GN. Use of TLS parameters to model anisotropic displacements in macromolecular refinement. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2001;57:122–133. doi: 10.1107/s0907444900014736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chang KH, Dunaway-Mariano D. Determination of the chemical pathway for 4-chlorobenzoate:coenzyme A ligase catalysis. Biochemistry. 1996;35:13478–13484. doi: 10.1021/bi961284w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schneider K, Hovel K, Witzel K, Hamberger B, Schomburg D, Kombrink E, Stuible HP. The substrate specificity-determining amino acid code of 4-coumarate:CoA ligase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:8601–8606. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1430550100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Black PN, DiRusso CC, Metzger AK, Heimert TL. Cloning, sequencing, and expression of the fadD gene of Escherichia coli encoding acyl coenzyme A synthetase. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:25513–25520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hisanaga Y, Ago H, Nakagawa N, Hamada K, Ida K, Yamamoto M, Hori T, Arii Y, Sugahara M, Kuramitsu S, Yokoyama S, Miyano M. Structural basis of the substrate-specific two-step catalysis of long chain fatty acyl-CoA synthetase dimer. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:31717–31726. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400100200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kleywegt GJ, Jones TA. Detection, delineation, measurement and display of cavities in macromolecular structures. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1994;50:178–185. doi: 10.1107/S0907444993011333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ingram-Smith C, Woods BI, Smith KS. Characterization of the acyl substrate binding pocket of acetyl-CoA synthetase. Biochemistry. 2006;45:11482–11490. doi: 10.1021/bi061023e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stachelhaus T, Mootz HD, Marahiel MA. The specificity-conferring code of adenylation domains in nonribosomal peptide synthetases. Chem Biol. 1999;6:493–505. doi: 10.1016/S1074-5521(99)80082-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Eppelmann K, Stachelhaus T, Marahiel MA. Exploitation of the selectivity-conferring code of nonribosomal peptide synthetases for the rational design of novel peptide antibiotics. Biochemistry. 2002;41:9718–9726. doi: 10.1021/bi0259406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Grunewald J, Marahiel MA. Chemoenzymatic and template-directed synthesis of bioactive macrocyclic peptides. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2006;70:121–146. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.70.1.121-146.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.