Abstract

BACKGROUND

Mantle-cell lymphoma is generally incurable. Initial treatment is not standardized but usually includes cytotoxic chemotherapy. Lenalidomide, an immunomodulatory compound, and rituximab, an anti-CD20 antibody, are active in patients with recurrent mantle-cell lymphoma. We evaluated lenalidomide plus rituximab as a first-line therapy.

METHODS

We conducted a single-group, multicenter, phase 2 study with induction and maintenance phases. During the induction phase, lenalidomide was administered at a dose of 20 mg daily on days 1 through 21 of every 28-day cycle for 12 cycles; the dose was escalated to 25 mg daily after the first cycle if no dose-limiting adverse events occurred during the first cycle and was reduced to 15 mg daily during the maintenance phase. Rituximab was administered once weekly for the first 4 weeks and then once every other cycle until disease progression. The primary end point was the overall response rate. Secondary end points included outcomes related to safety, survival, and quality of life.

RESULTS

A total of 38 participants were enrolled at four centers from July 2011 through April 2014. The median age was 65 years. On the basis of the Mantle Cell Lymphoma International Prognostic Index scores, the proportions of participants with low-risk, intermediate-risk, and high-risk disease at baseline were similar (34%, 34%, and 32%, respectively). The most common grade 3 or 4 adverse events were neutropenia (in 50% of the patients), rash (in 29%), thrombocytopenia (in 13%), an inflammatory syndrome (“tumor flare”) (in 11%), anemia (in 11%), serum sickness (in 8%), and fatigue (in 8%). At the median follow-up of 30 months (through February 2015), the overall response rate among the participants who could be evaluated was 92% (95% confidence interval [CI], 78 to 98), and the complete response rate was 64% (95% CI, 46 to 79); median progression-free survival had not been reached. The 2-year progression-free survival was estimated to be 85% (95% CI, 67 to 94), and the 2-year overall survival 97% (95% CI, 79 to 99). A response to treatment was associated with improvement in quality of life.

CONCLUSIONS

Combination biologic therapy consisting of lenalidomide plus rituximab was active as initial therapy for mantle-cell lymphoma. (Funded by Celgene and Weill Cornell Medical College; ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT01472562.)

Mantle-cell lymphoma, which is characterized by CD5+CD23– follicular mantle B cells with t(11;14)(q13;q32) translocation and cyclin D1 overexpression,1 is generally incurable and is associated with a median survival of approximately 4 to 5 years.2–4 Initial treatment for mantle-cell lymphoma varies but usually includes chemoimmunotherapy5–7 and often involves intensive approaches, such as high-dose chemotherapy and hematopoietic-cell transplantation.8–10 Treatment selection is influenced by age, coexisting conditions, and individual preferences. Treatment of patients with mantle-cell lymphoma, who are frequently older (median age, 65 years) and unsuitable candidates for intensive regimens,11 remains a clinical challenge.

Lenalidomide is a second-generation immunomodulatory compound that has pleiotropic anti-tumor effects, including stimulation of T-cell and natural killer (NK)–cell expansion, inhibition of tumor-associated angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis,12–14 and induction of lymphoma-cell apoptosis through the down-regulation of cyclin D1.15 When combined with rituximab in vitro, lenalidomide augments antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity by enhancing apoptosis and activation of NK-cell–mediated cytotoxicity16 and has been shown to overcome rituximab resistance in patients with lymphoma.17,18 Lenalidomide, either as a single agent19,20 or in combination with rituximab,21 has shown clinical efficacy in patients with recurrent mantle-cell lymphoma.

The major therapeutic goals in patients with mantle-cell lymphoma are to extend survival and improve quality of life. We hypothesized that initial management of mantle-cell lymphoma with biologic agents might offer patients effective disease control and a favorable side-effect profile relative to some chemotherapy approaches and that it could be applicable to a broad range of patients. We therefore conducted an uncontrolled, multicenter, phase 2 study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of the combination of lenalidomide and rituximab as induction and maintenance therapy in patients with previously untreated mantle-cell lymphoma.

METHODS

PATIENT ELIGIBILITY

We enrolled patients who had untreated, measurable mantle-cell lymphoma with characteristic histologic, immunophenotypic, and cytogenetic features. A score on the Mantle Cell Lymphoma International Prognostic Index (MIPI) indicating low-risk or intermediate-risk disease (<6.2) or a score indicating high-risk disease (≥6.2) with concomitant contraindications to chemotherapy was required (for a complete description of the index, see the Supplementary Appendix, available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org). Other requirements for enrollment included an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0, 1, or 2 (on a scale of 0 to 5, with 0 representing no symptoms and higher numbers reflecting greater disability), an absolute neutrophil count of at least 1000 per microliter, a platelet count of at least 75,000 per microliter, a creatinine clearance of 30 ml per minute or higher, and total levels of bilirubin, aspartate amino-transferase, and alanine aminotransferase that were no higher than 2 times the upper limit of the normal range. Patients were excluded if they had central nervous system lymphoma, human immunodeficiency virus infection, or active hepatitis B or C virus infection, or if they had had invasive malignant tumors within the previous 5 years.

STUDY DESIGN

This open-label, single-group, uncontrolled study consisted of induction and maintenance phases (see Fig. S1 in the Supplementary Appendix). During the induction phase, patients with a creatinine clearance of 60 ml per minute or higher received lenalidomide at a dose of 20 mg daily on days 1 through 21 of every 28-day cycle for 12 cycles; the dose was escalated to 25 mg daily after the first cycle if no dose-limiting adverse events occurred during the first cycle. Rituximab was administered at a dose of 375 mg per square meter of body-surface area during weeks 1, 2, 3, 4, 13, 21, 29, 37, and 45, for a total of nine doses. During the maintenance phase, lenalidomide was administered at a dose of 15 mg daily on days 1 through 21 of every 28-day cycle, and rituximab was administered once every 8 weeks. Treatment was continuous for at least 36 cycles or until disease progression, development of unacceptable adverse effects, or withdrawal from the study. For patients with a creatinine clearance of 30 to less than 60 ml per minute, the starting dose of lenalidomide was 10 mg daily during the induction phase (with escalation to 15 mg daily if no dose-limiting adverse events occurred) and 5 mg daily during the maintenance phase (without dose escalation). Patients received thromboprophylaxis with aspirin or low-molecular-weight heparin unless they required treatment for known thrombosis. Asymptomatic carriers of hepatitis B virus received antiviral therapy. Prophylactic growth factors were not empirically administered.

EFFICACY AND SAFETY ASSESSMENTS

We used the criteria reported by Cheson et al. (see the Supplementary Appendix) to determine responses to treatment.22 Computed tomography (CT) was performed at baseline, every 3 months for 2 years, and then every 6 months thereafter until disease progression. Combined positron-emission tomography and CT (PET-CT) was optional at baseline. A bone marrow biopsy and PET-CT were performed to confirm a complete response. Adverse events were graded according to National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 4.0 (http://evs.nci.nih.gov/ftp1/CTCAE/CTCAE_4.03_2010-06-14_QuickReference_5x7.pdf).

QUALITY-OF-LIFE ANALYSIS

Health-related quality of life was measured with the use of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–Lymphoma (FACT-Lym),23 which includes a general questionnaire (FACT-G) that assesses physical well-being (7 items, with the total score ranging from 0 to 28), social well-being (7 items, with the total score ranging from 0 to 28), emotional well-being (6 items, with the total score ranging from 0 to 24), and functional well-being (7 items, with the total score ranging from 0 to 28) — with higher scores on each component indicating higher quality of life — as well as a lymphoma-specific questionnaire (15 items, with the total score ranging from 0 to 60 and higher scores indicating better control of lymphoma-specific symptoms). The assessment was performed at baseline, every 3 months for 2 years, and every 6 months thereafter. At 24 months, a quality-of-life exploratory analysis was performed on data from the first 32 patients. The FACT-Lym total score (the sum of the FACT-G total score and the score on the lymphoma-specific questionnaire [ranging from 0 to 168]) and the FACT-Lym trial outcome index score (the sum of the scores on the physical well-being, functional well-being, and lymphoma-specific questionnaires [ranging from 0 to 116]) were obtained for information related to clinical features, treatment, and response. Previous literature suggests that a minimally important difference is indicated by a change of 2.9 to 5.4 in the score on the lymphoma-specific questionnaire, 3 to 7 in the FACT-G total score, 6.5 to 11.2 in the Fact-Lym total score, and 5.5 to 11 in the Fact-Lym trial outcome index score.24

STUDY OVERSIGHT

This multicenter, phase 2 study was designed by investigators at Weill Cornell Medical College. All the authors participated in the collection and analysis of the data and vouch for the accuracy and completeness of the data and the fidelity of the study to the protocol (available at NEJM.org). The first draft of the manuscript was prepared by the first and last authors, and all the authors contributed to revisions and approved the final manuscript. The study was approved by the institutional review board at each participating center. All the participants provided written informed consent, and the trial was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice guidelines. An independent data and safety monitoring board at Weill Cornell Medical College conducted safety reviews twice a year. Celgene funded the research and provided the lenalidomide free of charge; Celgene approved the original protocol and all amendments as written, but had no role in the design of the study, the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data, or the preparation of the manuscript.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

The primary end point was the overall response rate. Sample size was determined according to Simon’s two-stage “minimax” design,25 with a response rate of less than 40% as the null hypothesis that treatment was unacceptable and a response rate of higher than 60% as the alternative hypothesis that the regimen deserved further exploration. We calculated a sample size that would give the study 80% power, at a significance level of 10%, to test the null and alternative hypotheses of the primary end point. Responses would be measured starting after month 3 and then every 3 to 4 months for the first 2 years. During the first stage, a response assessment based on the best response measured at month 6 would be conducted on the first 16 patients who could be evaluated. If 7 or more of the 16 patients had a response to treatment, enrollment would extend to 28 patients. During the second stage, if 15 or more of these 28 patients had a response, the treatment would then be worthy of further testing. Enrollment would be expanded post hoc to enhance the precision of the observed response rate, as determined by the calculation of 90% and 95% confidence intervals. With an estimated final sample size of 38 patients (34 patients who could be evaluated), a 90% confidence interval for an expected response rate of 60% could be calculated to be within ±14.0% of the observed response rate and a 95% confidence interval could be calculated to be within ±16.7% of the observed response rate.

Secondary end points of progression-free and overall survival were assessed with the use of a Kaplan–Meier analysis. Paired t-tests were used to compare quality-of-life measures obtained at follow-up time points with those obtained at baseline. Data from all participants who received any therapy were included in the safety analyses. For the secondary end points, all P values were two-sided, and P values of less than 0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance. All analyses were performed with the use of SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute), and Stata software, version 13.0 (StataCorp).

RESULTS

PATIENT CHARACTERISTICS

During the period from July 2011 through April 2014, a total of 38 patients were enrolled in the study (Table 1). The median age was 65 years (range, 42 to 86); 100% had Ann Arbor stage III or IV disease, 39% had elevated lactate dehydrogenase levels, and 89% had bone marrow involvement. On the basis of the MIPI scores, 34% had low-risk disease, 34% had intermediate-risk disease, and 32% had high-risk disease; on the basis of the scores on the International Prognostic Index (IPI, which ranges from 0 to 5, with higher scores indicating greater risk; for a complete description of the index, see the Supplementary Appendix), 47% had low-intermediate–risk disease (score of 2), 26% had high-intermediate–risk disease (score of 3), and 11% had high-risk disease (score of 4 or 5). Results of staining for Ki-67 were available for 34 patients (89%), and the Ki-67 index (the percentage of cells positive for Ki-67) was 30% or higher in 8 patients (21%). No patients had pleomorphic or blastoid histologic features. All the patients had indications for treatment, the most common of which were symptomatic lymphadenopathy (53%), cytopenias (18%), and bulky disease (13%). Two patients — one with a MIPI score indicating intermediate-risk disease and one with a score indicating high-risk disease — could not be evaluated because they had an inflammatory syndrome (“tumor flare”) during the first cycle and were withdrawn before response assessment. At the median follow-up of 30 months (through February 2015), the 36 patients who could be evaluated had collectively undergone a total of 932 cycles of therapy with lenalidomide and had each received a median of 16 doses (range, 4 to 26) of rituximab.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics.

| Characteristic | Patients (N = 38) |

|---|---|

| Sex — no. (%) | |

| Male | 27 (71) |

| Female | 11 (29) |

| Age — yr | |

| Median | 65 |

| Range | 42–86 |

| ECOG performance status — no. (%)* | |

| 0–1 | 37 (97) |

| >1 | 1 (3) |

| Ann Arbor stage III or IV — no. (%) | 38 (100) |

| Lactate dehydrogenase level — no. (%) | |

| Normal | 23 (61) |

| Elevated | 15 (39) |

| Bone marrow involvement — no. (%) | |

| Yes | 34 (89) |

| No | 4 (11) |

| MIPI score — no. (%)† | |

| <5.7 | 13 (34) |

| 5.7 to <6.2 | 13 (34) |

| ≥6.2 | 12 (32) |

| IPI score — no. (%)‡ | |

| 0–1 | 6 (16) |

| 2 | 18 (47) |

| 3 | 10 (26) |

| 4–5 | 4 (11) |

| Ki-67 index — no. (%) | |

| <30% | 26 (68) |

| ≥30% | 8 (21) |

| Unavailable | 4 (11) |

| Indication for treatment — no. (%) | |

| Symptomatic lymphadenopathy | 20 (53) |

| Cytopenia | 7 (18) |

| Bulky disease (>5 cm) | 5 (13) |

| Gastrointestinal symptom | 3 (8) |

| Patient preference | 2 (5) |

| Rapidly rising white-cell count (>100,000/μl) | 1 (3) |

An Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance-status score of 0 indicates no symptoms, and a score of 1 indicates mild symptoms; higher scores indicate greater disability.

A Mantle Cell Lymphoma International Prognostic Index (MIPI) score lower than 5.7 indicates low-risk disease, a score of 5.7 to less than 6.2 indicates intermediate-risk disease, and a score of 6.2 or higher indicates high-risk disease.

A International Prognostic Index (IPI) score of 0 or 1 indicates low-risk disease, a score of 2 indicates low-intermediate–risk disease, a score of 3 indicates high-intermediate–risk disease, and a score of 4 or 5 indicates high-risk disease.

EFFICACY

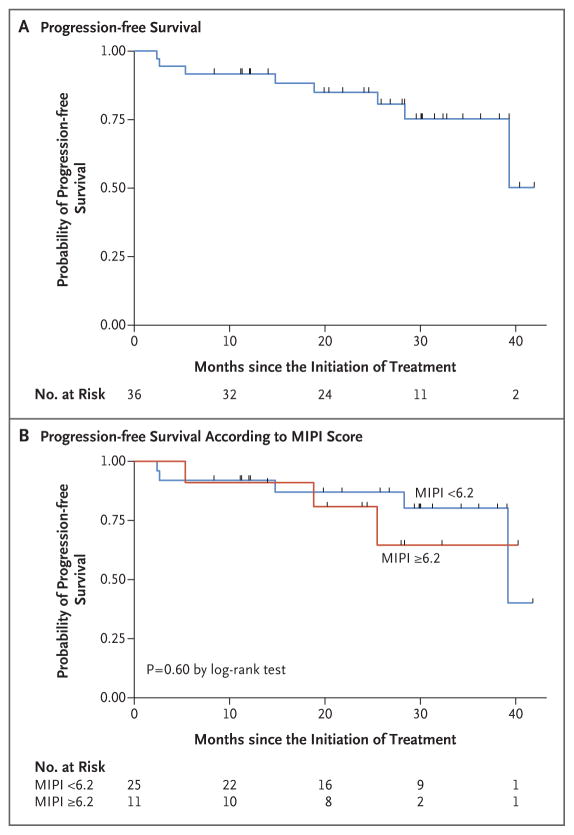

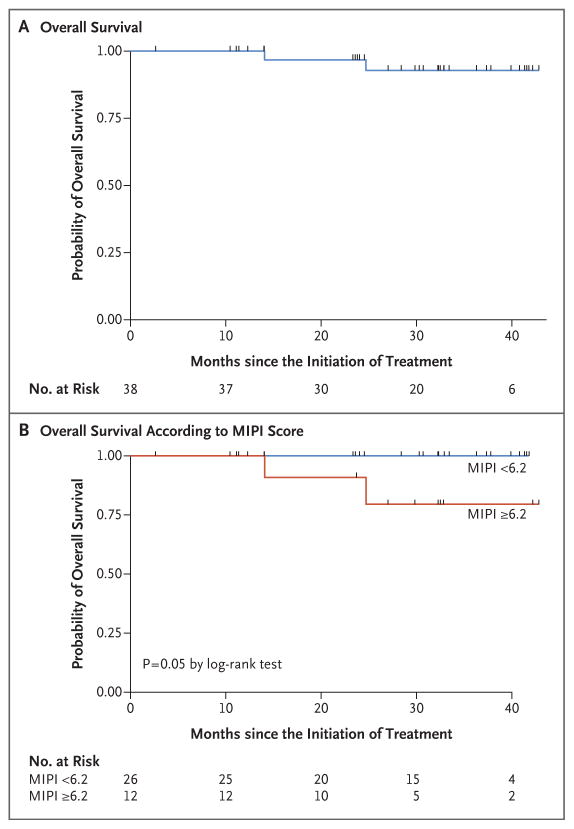

At the median follow-up of 30 months (range, 10 to 42), in the intention-to-treat population (38 patients), the overall response rate was 87% and the complete response rate was 61%. Among the patients who could be evaluated (36 patients), the overall response rate was 92% and the complete response rate was 64% (Table 2). The number of complete responses increased over time with continuous treatment (Fig. S2 in the Supplementary Appendix). The median time to a partial response to treatment was 3 months (range, 3 to 13), and the median time to a complete response was estimated to be 11 months (range, 3 to 22). The 2-year progression-free survival rate was 85% (95% confidence interval [CI], 67 to 94), and the 2-year overall survival rate was 97% (95% CI, 79 to 99). Median progression-free survival and median overall survival had not yet been reached at the median follow-up (Table 3 and Fig. 1 and 2).

Table 2.

Rates of Best Response at the Median Follow-up of 30 Months.

| Response | Patients | Intention-to-Treat Population (N = 38) | Patients Who Could Be Evaluated (N = 36) |

|---|---|---|---|

| no. | % | ||

| Overall response | 33 | 87 | 92 |

|

| |||

| Complete response* | 23 | 61 | 64 |

|

| |||

| Partial response | 10 | 26 | 28 |

|

| |||

| Stable disease | 1 | 3 | 3 |

|

| |||

| Progressive disease† | 2 | 5 | 6 |

|

| |||

| Could not be evaluated‡ | 2 | 5 | |

A complete response was confirmed by means of combined positron-emission tomography and computed tomography and, when indicated, by means of a bone marrow biopsy.

Although eight patients had progressive disease, two had primary progressive disease; six other patients had either stable disease, partial remission, or complete remission before progressive disease developed.

Treatment was discontinued because an inflammatory syndrome (tumor flare) without disease progression occurred before the response assessment was performed.

Table 3.

Survival and Follow-up Data.

| Variable | Value |

|---|---|

| Median progression-free survival | Not reached |

| 2-Yr progression-free survival — % of patients (95% CI) | 85 (67–94) |

| 2-Yr overall survival — % of patients (95% CI) | 97 (79–99) |

| Follow-up time — mo | |

| Median | 30 |

| Range | 10–42 |

| Time to partial response — mo | |

| Median | 3 |

| Range | 3–13 |

| Time to complete response — mo* | |

| Median | 11 |

| Range | 3–22 |

A complete response was confirmed by means of combined positron-emission tomography and computed tomography and, when indicated, by means of a bone marrow biopsy.

Figure 1. Progression-free Survival.

Panel A shows the probability of progression-free survival among the 36 patients who could be evaluated. Panel B shows the probability of progression-free survival according to the baseline score on the Mantle Cell Lymphoma International Prognostic Index (MIPI) — lower than 6.2 (indicating low-risk or intermediate-risk disease) versus 6.2 or higher (indicating high-risk disease).

Figure 2. Overall Survival.

Panel A shows the probability of overall survival among all 38 patients. Panel B shows the probability of overall survival according to the baseline MIPI score — lower than 6.2 (indicating low-risk or intermediate-risk disease) versus 6.2 or higher (indicating high-risk disease).

Neither the MIPI and IPI scores nor the Ki-67 index measurements were correlated with response to treatment or progression-free survival. A MIPI score indicating high-risk disease was correlated with an unfavorable overall survival (P = 0.05) (Fig. 2). Of the 36 patients who could be evaluated, 28 (78%) were in remission without disease progression, including 26 who had completed induction therapy and were receiving maintenance therapy, 1 who had almost completed induction therapy, and 1 who had received the study treatment for 3 years and was no longer receiving therapy while remaining in complete remission. Eight patients who could be evaluated had disease progression: 3 had primary refractory disease, and 5 had disease progression after having had initial responses (2 who had had complete responses and progression-free survival of 18 and 39 months and 3 who had had partial responses and progression-free survival of 14, 25, and 28 months). Two participants died from progressive disease, including 1 who could not be evaluated and had had disease progression after multiple subsequent regimens and 1 who had been in complete remission for 18 months.

ADVERSE EVENTS

Treatment was associated with toxic effects that have been reported previously with these agents (Table 4, and Table S1 in the Supplementary Appendix). Grade 3 or 4 hematologic adverse events included neutropenia (in 50% of the patients, 42% during the induction phase and 32% during the maintenance phase), thrombocytopenia (in 13% of the patients, 11% during the induction phase and 5% during the maintenance phase), and anemia (in 11% of the patients, 8% during the induction phase and 3% during the maintenance phase). Two patients (5%) had febrile neutropenia, which resolved with the administration of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor and systemic antibiotic agents. Grade 3 or 4 non-hematologic adverse events that occurred in more than 5% of patients were rash (in 29%), an inflammatory syndrome (tumor flare) (in 11%), serum sickness associated with rituximab (in 8%), and fatigue (in 8%); these were reported only during the induction phase. Grade 1 or 2 nonhematologic adverse events that occurred in more than 25% of patients were diarrhea, cough, hyperglycemia, constipation, edema, nausea, anorexia, dyspnea, and elevated aminotransferase levels. Grade 1 or 2 infections that occurred during both the induction and maintenance phases included upper respiratory tract infection (in 39%), urinary tract infection (in 18%), sinusitis (in 11%), and cellulitis (in 8%). Grade 3 infections — including three cases of pneumonia, one case of cholangitis, and one case of West Nile viral encephalitis — were reported during the maintenance phase; all resolved with the administration of antibiotics and supportive care. Secondary cancers were predominantly noninvasive skin cancers requiring local therapy, including two cases of squamous-cell carcinoma, one case of basal-cell carcinoma, and two cases of melanoma in situ. Merkel-cell carcinoma developed in an 86-year-old participant after 18 months of therapy, and pancreatic cancer was diagnosed in a 68-year-old participant after 12 months of therapy.

Table 4.

Adverse Events.*

| Adverse Event | Both Phases | Induction Phase | Maintenance Phase | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any Grade | Grade ≥3 | Any Grade | Grade ≥3 | Any Grade | Grade ≥3 | |

| number of patients (percent) | ||||||

| Hematologic | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Neutropenia | 28 (74) | 19 (50) | 27 (71) | 16 (42) | 21 (55) | 12 (32) |

|

| ||||||

| Anemia | 23 (60) | 4 (11) | 18 (47) | 3 (8) | 11 (29) | 1 (3) |

|

| ||||||

| Thrombocytopenia | 15 (39) | 5 (13) | 11 (29) | 4 (11) | 11 (29) | 2 (5) |

|

| ||||||

| Febrile neutropenia | 2 (5) | 2 (5) | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | 1 (3) |

|

| ||||||

| Infectious | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 15 (39) | 0 | 9 (24) | 0 | 11 (29) | 0 |

|

| ||||||

| Urinary tract infection | 7 (18) | 0 | 4 (11) | 0 | 4 (11) | 0 |

|

| ||||||

| Sinusitis | 4 (11) | 0 | 1 (3) | 0 | 3 (8) | 0 |

|

| ||||||

| Cellulitis | 3 (8) | 0 | 2 (5) | 0 | 1 (3) | 0 |

|

| ||||||

| Pneumonia | 3 (8) | 3 (8) | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | 2 (5) | 2 (5) |

|

| ||||||

| Other | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Fatigue | 28 (74) | 3 (8) | 25 (66) | 3 (8) | 12 (32) | 0 |

|

| ||||||

| Rash | 25 (66) | 11 (29) | 25 (66) | 11 (29) | 0 | 0 |

|

| ||||||

| Fever | 22 (58) | 0 | 19 (50) | 0 | 4 (11) | 0 |

|

| ||||||

| Cough | 21 (55) | 0 | 18 (47) | 0 | 6 (16) | 0 |

|

| ||||||

| Diarrhea | 21 (55) | 0 | 20 (53) | 0 | 14 (37) | 0 |

|

| ||||||

| Hyperglycemia | 19 (50) | 2 (5) | 12 (32) | 2 (5) | 14 (37) | 0 |

|

| ||||||

| Constipation | 17 (45) | 0 | 17 (45) | 0 | 4 (11) | 0 |

|

| ||||||

| Edema | 16 (42) | 0 | 14 (37) | 0 | 3 (8) | 0 |

|

| ||||||

| Inflammatory syndrome (tumor flare) | 13 (34) | 4 (11) | 13 (34) | 4 (11) | 0 | 0 |

|

| ||||||

| Infusion reaction | 13 (34) | 1 (3) | 13 (34) | 1 (3) | 0 | 0 |

|

| ||||||

| Nausea | 12 (32) | 0 | 12 (32) | 0 | 1 (3) | 0 |

|

| ||||||

| Anorexia | 11 (29) | 0 | 10 (26) | 0 | 3 (8) | 0 |

|

| ||||||

| Dyspnea | 11 (29) | 1 (3) | 10 (26) | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | 0 |

|

| ||||||

| Elevated alanine aminotransferase level | 13 (34) | 2 (5) | 9 (24) | 1 (3) | 4 (11) | 1 (3) |

|

| ||||||

| Elevated aspartate aminotransferase level | 11 (29) | 2 (5) | 8 (21) | 1 (3) | 4 (11) | 1 (3) |

|

| ||||||

| Hypothyroidism | 6 (16) | 0 | 6 (16) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

The table includes all treatment-related hematologic and infectious adverse events, as well as other adverse events that occurred in more than 15% of the 38 patients.

TREATMENT MODIFICATIONS

Among the 33 patients with normal renal function, 36% had no unacceptable side effects associated with the dose escalation from 20 mg to 25 mg, whereas 42% required a dose reduction from 20 mg to 15 mg or less. During the induction phase, serum sickness–like symptoms developed in 2 patients; rituximab was discontinued and treatment with single-agent lenalidomide was continued. During the maintenance phase, 6 patients received modified therapy while they were in remission: rituximab was discontinued in 2 patients with hypogammaglobulinemia (1 with recurrent urinary tract infections and 1 with sinusitis), and lenalidomide was discontinued in 4 patients (2 at the investigators’ discretion, 1 after development of an asymptomatic grade 4 liver-function abnormality, and 1 because of a reversible grade 4 ventricular arrhythmia that required placement of an automatic implantable cardiac defibrillator in a patient with a history of dysrhythmia).

OUTCOMES AFTER RELAPSE

Of the eight patients who had disease progression while they were receiving treatment, all remained alive except for an 86-year-old participant who opted for palliation. Seven had responses to subsequent therapy, with generally favorable outcomes (Table S2 in the Supplementary Appendix). Three had a response to bendamustine-based therapy; one of these patients then underwent autologous stem-cell transplantation. One patient received radiotherapy. The remaining three had responses to ibrutinib-based therapy. Four of the seven patients had a repeat tissue biopsy at the time of relapse; in all four patients, the Ki-67 index was similar to that measured at baseline (range, 5 to 20%). Therefore, data obtained after relapse showed no evidence of treatment resistance or unfavorable tumor biologic features.

QUALITY-OF-LIFE ASSESSMENT

The completion rate of the FACT-Lym questionnaire ranged from 62 to 88% at any given time point. At baseline, the mean (±SD) total score was 130.8±22.8, and the mean modified trial outcome index score was 91.0±17.5. The scores were not correlated with age, performance status, MIPI or IPI score, or clinical response. Quality-of-life scores remained stable or improved throughout the induction and maintenance phases. Trends toward improvement from baseline were noted in the mean FACT-Lym total scores for patients who completed the assessment both at month 12 and at baseline (139.1±19.1 at month 12 vs. 133.6±22.8 at baseline, P = 0.04) and those who completed the assessment both at month 21 and at baseline (139.3±24.1 vs. 133.7±24.6, P = 0.06). Trends toward improvement from baseline were also noted in the mean FACT-Lym trial outcome index scores for patients who completed the assessment both at month 9 and at baseline (98.2±13.1 at month 9 vs. 92.6±18.9 at baseline, P = 0.07), those who completed the assessment both at month 12 and at baseline (98.2±14.0 vs. 93.0±17.9, P = 0.06), and those who completed the assessment both at month 21 and at baseline (98.7±15.7 vs. 93.7±18.5, P = 0.09) (Fig. S3 in the Supplementary Appendix).

DISCUSSION

We report the results of an uncontrolled study delineating the efficacy and safety of a combination biologic therapy as initial therapy for mantle-cell lymphoma. Our data show that a lower-intensity approach for initial therapy than that usually used in the case of patients with this cancer can be highly active, with durable responses observed in most patients. In addition to induction therapy with lenalidomide plus rituximab, maintenance therapy with those agents is feasible and effective. The patients who had disease progression had generally favorable responses to subsequent therapy, without evidence that initial therapy with lenalidomide plus rituximab compromised subsequent treatment outcomes.

Initial treatment for mantle-cell lymphoma varies but usually includes chemotherapy. Although historical comparisons are of limited reliability, the estimated 2-year progression-free survival of 85% among patients receiving lenalidomide plus rituximab is of interest relative to data reported on patients receiving outpatient-based chemotherapy regimens, including R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone),5 R-CHOP with interferon-alfa maintenance therapy,6,26 R-CHOP plus bortezomib as induction and maintenance therapy,27,28 and bendamustine plus rituximab7; the median progression-free survival associated with those regimens has ranged from 16.6 to 35.4 months. The efficacy of lenalidomide plus rituximab in a broad patient population, including patients who were ineligible for intensive approaches, is particularly notable in the context of data reported on patients receiving inpatient-based regimens, including high-dose chemotherapy with autologous hematopoietic-cell transplantation.8–10

The patients with mantle-cell lymphoma who were involved in this study had a median age of 65 years, with 24 patients (63%) older than 60 years of age, 10 (26%) older than 70 years of age, and 5 (13%) older than 80 years of age. Two thirds of the participants had MIPI scores indicating intermediate-risk disease (34%) or high-risk disease (32%), and 95% were symptomatic and required initiation of treatment. These patient characteristics underscore the relevance of the current study to patients routinely seen in clinical practice.

The number of complete responses to lenalidomide plus rituximab increased over time during the induction and maintenance phases; a complete response was observed in 4 patients (11%) at month 6, in 9 (24%) at month 9, and in 19 (50%) at month 12. By month 24, during the maintenance phase, 23 patients (61%) had a complete response, reflecting the durability of responses and the measurable clinical benefit of maintenance therapy. Rituximab has previously been shown to have benefit as maintenance therapy both after disease relapse and after chemotherapy.26,29,30 The duration of maintenance therapy remains to be determined, and it is unclear whether the combination of lenalidomide and rituximab is more effective than rituximab alone as maintenance therapy. The latter question may be answered by an ongoing randomized, phase 2, intergroup study (ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT01415752), which is evaluating induction therapy with bendamustine plus rituximab with or without bortezomib followed by maintenance therapy with rituximab alone or in combination with lenalidomide. It will be important to determine the durability of responses to all therapies.

The treatment-related side effects that occurred with lenalidomide plus rituximab were expected. We used the maximum tolerated dose of lenalidomide (25 mg daily). The primary hematologic adverse event was myelosuppression, which we were able to address with dose modifications. There were no treatment-induced deaths. Nonhematologic adverse events included an inflammatory syndrome (tumor flare), which occurred at the initiation of therapy and resolved with supportive care. The trajectory of health-related quality of life reflected the responses to treatment and overall absence of accumulative treatment-related toxic effects; some improvement from baseline in quality of life was observed starting at month 9 in response to treatment and was maintained thereafter in the majority of participants receiving continuous therapy. Our data support further evaluation of the lenalidomide plus rituximab regimen, potentially in combination with other agents.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by Celgene Corporation and a Weill Cornell Medical College Clinical Translational Science Center grant (UL1-TR000457-06, to Dr. Christos).

We thank Emily Kaplan, Louisa Drake, and Paige Wolsten-croft for assistance in patient data collection.

Footnotes

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org.

References

- 1.Pérez-Galán P, Dreyling M, Wiestner A. Mantle cell lymphoma: biology, pathogenesis, and the molecular basis of treatment in the genomic era. Blood. 2011;117:26–38. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-04-189977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Herrmann A, Hoster E, Zwingers T, et al. Improvement of overall survival in advanced stage mantle cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:511–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.8435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Campo E, Rule S. Mantle cell lymphoma: evolving management strategies. Blood. 2015;125:48–55. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-05-521898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martin P, Chadburn A, Christos P, et al. Outcome of deferred initial therapy in mantle-cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1209–13. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.6121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Howard OM, Gribben JG, Neuberg DS, et al. Rituximab and CHOP induction therapy for newly diagnosed mantle-cell lymphoma: molecular complete responses are not predictive of progression-free survival. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:1288–94. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.5.1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lenz G, Dreyling M, Hoster E, et al. Immunochemotherapy with rituximab and cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone significantly improves response and time to treatment failure, but not long-term outcome in patients with previously untreated mantle cell lymphoma: results of a prospective randomized trial of the German Low Grade Lymphoma Study Group (GLSG) J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:1984–92. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.08.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rummel MJ, Niederle N, Maschmeyer G, et al. Bendamustine plus rituximab versus CHOP plus rituximab as first-line treatment for patients with indolent and mantle-cell lymphomas: an open-label, multicentre, randomised, phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2013;381:1203–10. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61763-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Romaguera JE, Fayad L, Rodriguez MA, et al. High rate of durable remissions after treatment of newly diagnosed aggressive mantle-cell lymphoma with rituximab plus hyper-CVAD alternating with rituximab plus high-dose methotrexate and cytarabine. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:7013–23. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.1825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Geisler CH, Kolstad A, Laurell A, et al. Long-term progression-free survival of mantle cell lymphoma after intensive front-line immunochemotherapy with in vivo-purged stem cell rescue: a nonrandomized phase 2 multicenter study by the Nordic Lymphoma Group. Blood. 2008;112:2687–93. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-03-147025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Delarue R, Haioun C, Ribrag V, et al. CHOP and DHAP plus rituximab followed by autologous stem cell transplantation in mantle cell lymphoma: a phase 2 study from the Groupe d’Etude des Lymphomes de l’Adulte. Blood. 2013;121:48–53. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-09-370320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abrahamsson A, Albertsson-Lindblad A, Brown PN, et al. Real world data on primary treatment for mantle cell lymphoma: a Nordic Lymphoma Group observational study. Blood. 2014;124:1288–95. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-03-559930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bartlett JB, Dredge K, Dalgleish AG. The evolution of thalidomide and its IMiD derivatives as anticancer agents. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:314–22. doi: 10.1038/nrc1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reddy N, Hernandez-Ilizaliturri FJ, Deeb G, et al. Immunomodulatory drugs stimulate natural killer-cell function, alter cytokine production by dendritic cells, and inhibit angiogenesis enhancing the anti-tumour activity of rituximab in vivo. Br J Haematol. 2008;140:36–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06841.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Song K, Herzog BH, Sheng M, et al. Lenalidomide inhibits lymphangiogenesis in preclinical models of mantle cell lymphoma. Cancer Res. 2013;73:7254–64. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-0750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moros A, Bustany S, Cahu J, et al. Antitumoral activity of lenalidomide in in vitro and in vivo models of mantle cell lymphoma involves the destabilization of cyclin D1/p27KIP1 complexes. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:393–403. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang L, Qian Z, Cai Z, et al. Synergistic antitumor effects of lenalidomide and rituximab on mantle cell lymphoma in vitro and in vivo. Am J Hematol. 2009;84:553–9. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chong EA, Ahmadi T, Aqui NA, et al. Combination of lenalidomide and rituximab overcomes rituximab resistance in patients with indolent B-cell and mantle cell lymphomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21:1835–42. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-2221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ahmadi T, Chong EA, Gordon A, et al. Combined lenalidomide, low-dose dexamethasone, and rituximab achieves durable responses in rituximab-resistant indolent and mantle cell lymphomas. Cancer. 2014;120:222–8. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goy A, Sinha R, Williams ME, et al. Single-agent lenalidomide in patients with mantle-cell lymphoma who relapsed or progressed after or were refractory to bortezomib: phase II MCL-001 (EMERGE) study. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3688–95. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.49.2835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Trneny M, Lamy T, Walewski J, et al. Phase II randomized, multicenter study of lenalidomide vs best investigator’s choice in relapsed/refractory mantle cell lymphoma: results of the MCL-002 (SPRINT) study. Blood. 2014;124:626. abstract. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang M, Fayad L, Wagner-Bartak N, et al. Lenalidomide in combination with rituximab for patients with relapsed or refractory mantle-cell lymphoma: a phase 1/2 clinical trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:716–23. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70200-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cheson BD, Pfistner B, Juweid ME, et al. Revised response criteria for malignant lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:579–86. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.2403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith SK, Zimmerman S, Williams CS, Zebrack BJ. Health status and quality of life among non-Hodgkin lymphoma survivors. Cancer. 2009;115:3312–23. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harrison CN, Mesa RA, Kiladjian JJ, et al. Health-related quality of life and symptoms in patients with myelofibrosis treated with ruxolitinib versus best available therapy. Br J Haematol. 2013;162:229–39. doi: 10.1111/bjh.12375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Simon R. Optimal two-stage designs for phase II clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1989;10:1–10. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(89)90015-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kluin-Nelemans HC, Hoster E, Hermine O, et al. Treatment of older patients with mantle-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:520–31. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Robak T, Huang H, Jin J, et al. Bortezomib-based therapy for newly diagnosed mantle-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:944–53. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1412096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Till BG, Li H, Bernstein SH, et al. Phase II trial of R-CHOP plus bortezomib induction therapy followed by bortezomib maintenance for previously untreated mantle cell lymphoma: SWOG 0601. Blood. 2014;124:149. doi: 10.1111/bjh.13818. abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Forstpointner R, Unterhalt M, Dreyling M, et al. Maintenance therapy with rituximab leads to a significant prolongation of response duration after salvage therapy with a combination of rituximab, fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and mitoxantrone (R-FCM) in patients with recurring and refractory follicular and mantle cell lymphomas: results of a prospective randomized study of the German Low Grade Lymphoma Study Group (GLSG) Blood. 2006;108:4003–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-016725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chang JE, Li H, Smith MR, et al. Phase 2 study of VcR-CVAD with maintenance rituximab for untreated mantle cell lymphoma: an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group study (E1405) Blood. 2014;123:1665–73. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-08-523845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.