Abstract

Supraspinatus tears often result from chronic tendinopathy. However, the typical repair model is acute. Our laboratory developed an overuse animal model; however it is unclear whether induced overuse is necessary in the repair model. We studied the repaired properties of overuse-induced tendons compared to normal tendons. We hypothesized histological and mechanical properties would not be altered between the overuse-induced and normal tendons 1 and 4 weeks after repair. Thirty-one adult male Sprague-Dawley rats were subjected to either overuse or cage activity for 4 weeks prior to bilateral supraspinatus tendon repair surgery. Rats were sacrificed at 1 and 4 weeks post-surgery and evaluated for histology and mechanics. Results at 1 week showed no clear histologic changes, but increased inflammatory protein expression in overuse tendons. At 4 weeks, percent relaxation was slightly increased in the overuse group. No other alterations in mechanics or histology were observed. Our results suggest that the effects of the surgical injury overshadow the changes evoked by overuse. Because clinically relevant mechanical parameters were not altered in the overuse group, we conclude that when examining tendons 4 weeks after repair in the classic rat supraspinatus model, inducing overuse prior to surgery is likely to be unnecessary.

Keywords: overuse, supraspinatus tendon repair, animal model

INTRODUCTION

Rotator cuff tears are a common cause of shoulder pain and dysfunction. Rotator cuff pathology is a progressive process often involving rotator cuff tendon tears and subsequent joint damage 1; 2. The majority of rotator cuff tears occur in the setting of chronic tendinopathy 3; 4. Two processes are thought to contribute to the development and progression of tendinopathy: an intrinsic mechanism, namely, that the tendon fails because of internal tissue pathology; and an extrinsic mechanism, in which impingement from surrounding structures causes the damage 5. Both intrinsic and extrinsic mechanisms can be invoked by overuse: in the former, because repetitive loading above the capacity of the tissue may cause internal micro-trauma, and in the latter, because repeated passage of the supraspinatus tendon through the coracoacromial arch may lead to impingement-related damage. Chronic inflammation in response to tendon overuse is also thought to contribute to tendon pathology, as increased expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines alter the normal biological processes in the joint 6. This abnormal biological environment, in conjunction with overuse-induced altered mechanical properties, may disrupt the native collagen fibers and tendon extracellular matrix proteins, resulting in rotator cuff tear initiation and propagation.

To investigate the pathogenesis of rotator cuff tendinopathy in the setting of overuse, our laboratory developed an animal model that would replicate both the intrinsic and the extrinsic mechanisms of tendinopathy 7–14. This rat model, based on daily downhill treadmill running that mimics repetitive overhead activity with eccentric contractions, produces the mechanical and histological properties characteristic of clinical tendinopathy in the setting of overuse. This model also produces increased gene expression of COX-2 and FLAP, inflammatory markers of the two arachidonic acid pathways 15 as well as an increase in the interleukin (IL) family of cytokines and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), among other increases in inflammatory markers 6.

Traditionally, the rat supraspinatus tendon injury and repair model in common use 15–21 utilizes an acute surgical detachment of an otherwise normal tendon. Given the fact that most rotator cuff tears occur in the setting of chronic tendinopathy, it might be asked if it is necessary to augment this model to include a period of daily downhill treadmill running, to more accurately mimic the typical clinical scenario of an “acute-on-chronic” supraspinatus tendon tear.

The research question addressed here, therefore, is whether induced overuse is a necessary (or advantageous) step when employing the traditional rat supraspinatus tendon injury and repair model. Given that the rat model for rotator cuff research has been extensively used and published, it is important to address this question. It is possible that overuse tendinopathy may produce differences in the mechanical, histological, collagen fiber organizational, or inflammatory properties seen after repair. On the contrary, it is also possible that the biological effects of surgical trauma dominate the more subtle effects of overuse. As such, we studied the post-detached and repaired properties of tendons subjected to overuse-induced tendinopathy and compared them to the properties found in normal tendons that have been detached and repaired. Because we expect the effect of surgical injury to overshadow any effect due to overuse, we hypothesized that expression of inflammatory proteins, histological properties, and collagen fiber organization would not be altered between the overuse-induced and normal tendons 1 week after supraspinatus surgical detachment and repair, and that the tendon mechanical and histological properties, and collagen fiber organization would not be altered between groups 4 weeks after supraspinatus surgical detachment and repair.

METHODS

Study design

Thirty-one adult male Sprague-Dawley rats (400–450g) were used in this Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved study. Rats were housed in pairs in a conventional facility with 12 hour light/dark cycles. Rats in the overuse group (n=13) were subjected to a 2 week training period of gradual increase in speed and duration followed by 4 weeks of downhill overuse treadmill activity (17m/min, 1hr/day, 5days/wk, 10° decline) to induce a tendinopathic condition as previously described 7; 11–14; 22–25. The experimental group was compared to a control (n=18) group, previously reported 18, which were allowed normal cage activity 8. All animals were subjected to identical bilateral supraspinatus detachment and repair as described 17. For analgesia, buprenorphine (0.05 mg/kg) was administered subcutaneously 30 minutes prior to surgery, 6–8 hours post-operatively, and then every 12 hours for the next 48 hours. Animals were monitored daily for the first week and then weekly until the time of sacrifice. A randomized subset of overuse (n=4) and control (n=4) animals were sacrificed 1 week post-surgery for histological and immunohistochemical analysis. The remaining animals were sacrificed 4 weeks post-surgery, as 4 weeks is commonly the earliest time point to examine mechanical parameters due to insufficient matrix development at earlier time points. Right limbs allocated for histology and immunohistochemistry (n=4 per group) were immediately dissected and fixed in formalin, and left limbs were frozen at −20°C until later use for mechanical testing.

Detachment and Repair Surgery

Briefly and as described previously 17, with the arm held in external rotation and adduction, the deltoid muscle was split in the transverse plane to expose the supraspinatus tendon. The tendon was grasped using double-armed 5-0 polypropylene suture (Surgipro II, Covidien, Mansfield, MA) and was sharply transected from its bony insertion. For repair, a 5 mm diameter high speed bur (Multipro 395, Dremel, Mt. Prospect, IL) was used to remove remaining fibrocartilage from the footprint of the tendon insertion site. A 0.5 mm bone tunnel was drilled from anterior to posterior through the greater tuberosity of the humerus. The suture was passed through the bone tunnel and tied down, affixing the tendon to the greater tuberosity using a modified Mason-Allen technique. The wound was flushed with saline, the deltoid sutured closed, and the skin closed with staples.

Tendon mechanical testing

Supraspinatus and humerus tendon-bone units were dissected from the shoulder and cleaned of excess soft tissue under a stereomicroscope. Stain lines were placed along the length of the tendon for optical strain measurement. Cross sectional area was measured using a custom laser device 26. The humerus was embedded in polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) and held in a custom fixture. The tendon was affixed between fine grit sand paper using cyanoacrylate and then fixed in a custom grip. Samples were immersed in a 37°C PBS bath and subjected to a mechanical testing protocol consisting of a preload to 0.08 N, ten cycles of preconditioning (0.1–0.5 N at 1% strain/s), a stress relaxation to 5% strain (5%/s) followed by a 600s hold, and finally a ramp to failure at 0.3%/s. Stress was calculated as force divided by cross sectional area and 2D Lagrangian optical strain was determined from stain line displacements measured from images taken throughout the test using custom tracking software 27; 28.

Histology

Histological analysis was performed to assess cell shape, cellularity, and collagen fiber organization at the injury site and midsubstance of the repaired supraspinatus tendon. At the time of sacrifice, supraspinatus-humerus units were immediately dissected, fixed in formalin, and processed using standard paraffin techniques. 7µm sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) to assess cell shape and cellularity and alcian blue and picrosirius red (ABPR) to assess collagen fiber orientation. Cell shape and cellularity were evaluated by three blinded graders using a semi-quantitative method that is comprehensive for the purpose of assessing tendon repair tissue 29. Circular standard deviation of collagen fibers was determined by images taken with a polarizing microscope and analysis with custom software as described previously 28; 30; 31.

Immunohistochemistry

At one week following surgery, immunohistochemistry was performed to assess expression of inflammatory proteins IL-1β, TNF-α, and CD45 in the injury site and midsubstance of the healing supraspinatus tendon during the inflammatory phase. For IL-1β and TNF-α, following deparaffinization and rehydration, sections were blocked for endogenous peroxidase by incubating in 3% H2O2 in methanol for 30 minutes and then washed in PBS. Antigen retrieval was performed by incubating in a 1:4 dilution of pepsin in 0.01N HCl solution for 20 minutes. Following washing, sections were incubated in 4% dry milk and 0.3% goat serum in PBS solution for 20 minutes to block non-specific binding. Sections were incubated overnight at room temperature with an IL-1β antibody (#AB1832; Chemicon, Temecula, CA; 1:500 dilution with PBS) or TNF-α antibody (#NBP1-19532; Novus Biologics, Littleton, CO; 1:1500 dilution with PBS). After washing, sections were incubated for 2 hours with horseradish peroxidase (HRP) goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody (111-035-003; Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA; 1:100 dilution in PBS). HRP was visualized as a brown immunoreactive stain using diaminobenzidine (DAB) (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO). For CD45, following deparaffinization and rehydration, antigen retrieval was performed by heating the slides in a sodium citrate buffer (pH adjusted to 6.0) bath held at 95°C for 20 minutes, and then allowing the slides to cool in the bath for 20 minutes. Non-specific binding was blocked by incubating in a solution of 10% milk and 10% serum in PBS for 20 minutes. Sections were then incubated overnight at 4°C with the CD45 antibody (ab 10558; Abcam, Cambridge, MA; 1:500 dilution with 5% serum and 5% milk in PBS). After washing with PBS, sections were blocked for endogenous peroxidase by incubating in 3% H2O2 in methanol for 30 minutes at room temperature. After washing, sections were incubated for 2 hours with HRP goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody, and HRP was visualized using DAB. Sections were then counterstained with Hematoxylin to stain cell nuclei in order to identify cells both positive and negative for CD45 staining. Signal intensity (IL-1β and TNF-α) and number of positively stained cells (CD45) was graded by three blinded investigators using a semi-quantitative method.

Statistical Analysis

Sample sizes were determined using an a priori power analysis. Mechanical testing comparisons were made using student’s t-tests with significance set a p≤0.05. Histological and immunohistochemical comparisons were made using Mann-Whitney U tests with significance set at p≤0.05.

RESULTS

Tendon Mechanical Properties

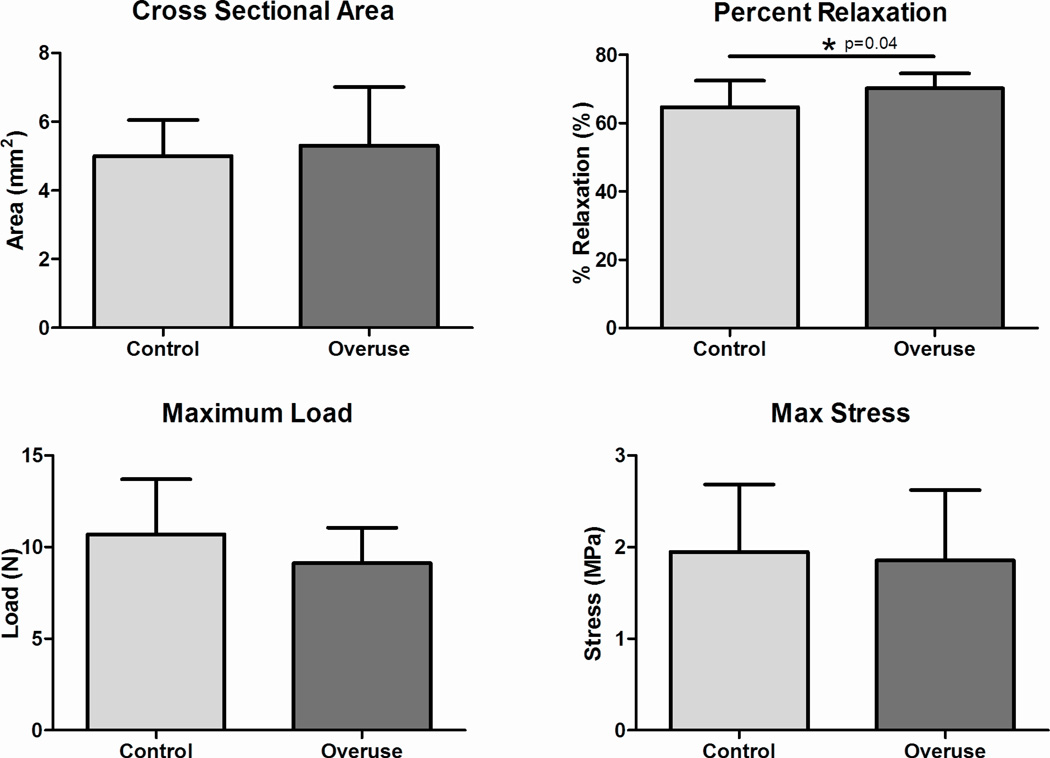

At 4 weeks following surgery, no significant differences were found between groups in cross sectional area, modulus, maximum stress, stiffness, or maximum load (Fig 1A, C, and D, Fig 2). The percent relaxation in the overuse group was 5% greater than the control group (Fig 1B); this small difference was statistically significant.

Figure 1.

Tendon mechanical properties. (A) No difference was found in cross sectional area. (B) Percent relaxation was significantly increased (5% increase) in the overuse group. (C) No difference was found in maximum load. (D) No difference was found in maximum stress. Data represented as mean ± SD.

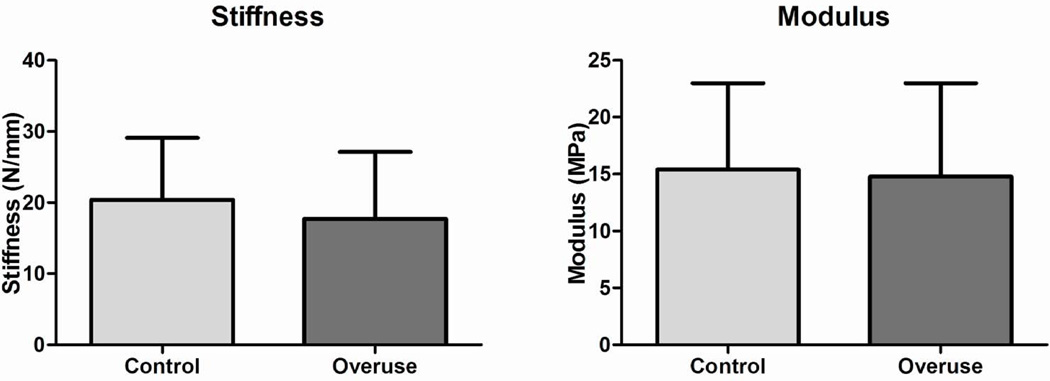

Figure 2.

Tendon mechanical propertie. (A) No difference was found in stiffness. (B) No difference was found in modulus. Data represented as mean ± SD.

Histology

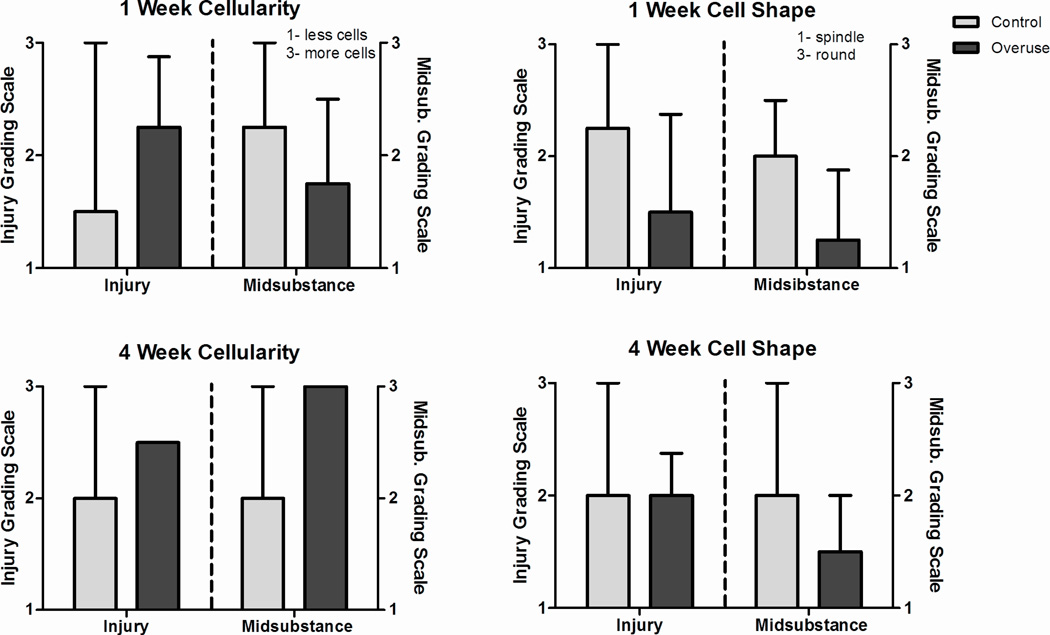

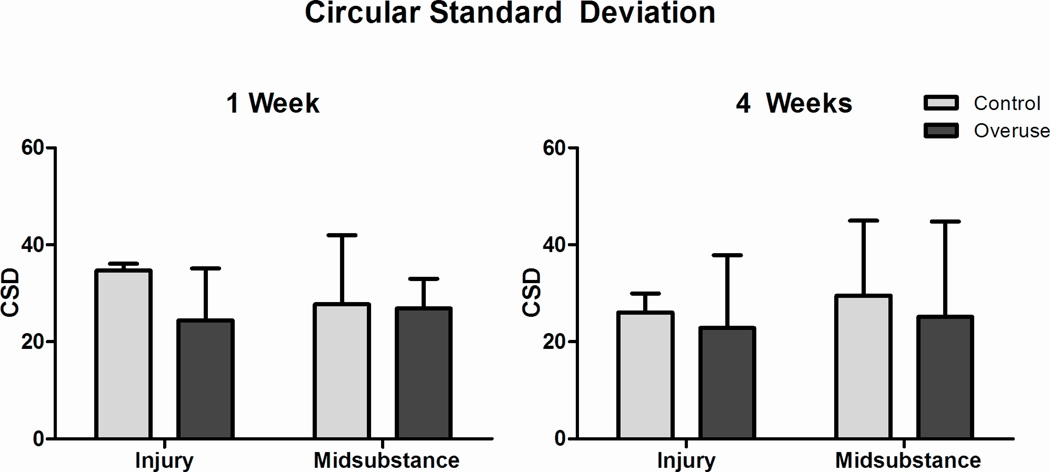

At both 1 and 4 weeks following surgery, no differences were observed in cell shape and cellularity (Fig 3) or in collagen fiber organization (Fig 4) at the injury site and midsubstance of the healing supraspinatus tendon.

Figure 3.

Histology grading. Grading scale is independent for each region. No differences were noted in injury or midsubstance at both 1 and 4 weeks. Data represented as median ± interquartile range.

Figure 4.

Circular standard deviation. No differences were noted at the injury site and the midsubstance at both 1 and 4 weeks. Data represented as mean ± SD.

Immunohistochemistry

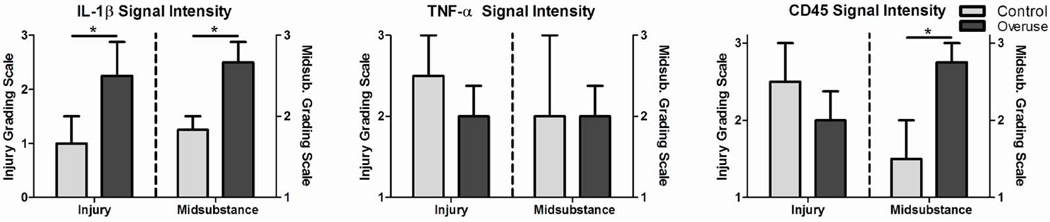

At 1 week following surgery, statistical differences were observed in inflammatory protein expression between overuse and control groups. Specifically, IL-1β staining intensity was significantly increased in the overuse group at both the injury site and the midsubstance (Fig 5A). No differences were observed in CD45 staining intensity at the injury site, although a significant increase was found in the overuse group in the midsubstance (Fig 5C). No differences were noted in TNF-α staining intensity at the injury site or the midsubstance (Fig 5B).

Figure 5.

Immunohistochemistry grading. Grading scale is independent for each region. (A) IL-1β was significantly increased in the overuse group at the injury site (p=0.03) and the midsubstance (p=0.03). (B) No differences were noted in TNF-α. (C) CD45 was significantly increased in the overuse group at the midsubstance (p=0.03). No differences were notes at the injury site. Data represented as median ± interquartile range.

DISCUSSION

This study evaluated the mechanical, histological, collagen fiber organizational, and inflammatory properties of the healing supraspinatus tendon following tendon detachment and repair. Normal tendons were compared to tendons subjected to overuse-induced tendinopathy pre-operatively, to determine whether it is necessary to augment the traditional model of rat rotator cuff repair to include a period of overuse.

We hypothesized that mechanical parameters would not be different between control and overuse groups 4 weeks following repair, and histological parameters would not be different between groups at both 1 and 4 weeks following repair. We found that adding pre-operative overuse to the traditional model is likely to be unnecessary. In particular, we found that the elastic mechanical properties were not altered between the overuse-induced tendinopathy and control tendons 4 weeks following supraspinatus detachment and repair surgery: stiffness and maximum load remained unchanged. Percent relaxation, however, was significantly increased in the overuse group. In the particular case of percent relaxation, a viscoelastic measure, this parameter is not well understood physiologically due to a lack of clinical viscoelastic data. In light of this, we propose that the small change of only 5% detected in percent relaxation between groups is likely not clinically relevant. Histological examination likewise found no changes between overuse and control groups at both the injury site and midsubstance.

Previous studies have reported disorganized, highly cellular and rounded cells in the injury site at both 1 and 4 weeks after surgical repair 16, which is consistent with our findings. Although percent relaxation, a measure of viscoelasticity, was slightly increased (5%) following repair of a tendinopathic tendon (a difference that was statistically significant), we suggest that this is likely a clinically insignificant change.

In support of the belief that overuse does have effects under the circumstances in this study, we found that inflammatory protein expression was significantly altered between overuse and control groups 1 week following supraspinatus detachment and repair surgery. Specifically, IL-1β staining intensity was significantly greater in the overuse group at both the injury site and the midsubstance. Additionally, CD45 staining was significantly increased in the overuse group in the midsubstance of the tendon. Nevertheless, the lack of mechanical and histological findings at 4 weeks suggests that these changes are indeed overwhelmed by the trauma of surgery.

There are several potential limitations of this study. First, this study is performed in an animal model. Although the rat rotator cuff model has been extensively utilized and published previously, no animal model can completely mimic the human condition. However, use of this model can provide important information to guide clinical studies. Second, elastic quasi-static mechanical testing was performed as is standard in the field. However, these properties do not represent a full picture of healing tendon function. When considering return to activity in a clinical scenario, investigation of dynamic and fatigue parameters might be relevant to overall tendon healing. Third, the biological and functional properties of the surrounding soft tissue (specifically the capsule and the joint surfaces) were not assessed. It also must be recalled that our findings are primarily limited to studies concerned with the 4 week (and likely longer) time point(s) and that studies examining inflammatory processes shortly after surgical repair (e.g., 1 week), may very well benefit from the addition of induced overuse prior to surgery. Longer time points might also be considered to examine mechanical parameters, although we would expect the effects of overuse compared to cage activity would equilibrate over time. In addition, because the control group was previously published, the control group was operated on approximately six weeks before the overuse group since the overuse group underwent the overuse protocol prior to surgery. Last, there may be properties that were not investigated (e.g., joint range of motion) that might also be relevant to clinical outcomes.

In conclusion, our results suggest that the biological effects of the surgical injury overshadow the changes evoked by overuse. Because clinically relevant mechanical parameters were not altered in the overuse group, we conclude that when examining tendons 4 weeks after a repair in the classic rat supraspinatus model, inducing overuse prior to surgery is likely to be unnecessary.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study was provided by VA RR&D O0979-R and NIH/NIAMS P30AR050950.

Footnotes

Author Contributions Statement: All authors have read and approved final version of manuscript. Contributions are as follows: JJT- research design, acquisition of data, data analysis and interpretation, drafting and revision of paper, approval of submitted and final versions; CNR- acquisition of data, data analysis and interpretation, revision of paper; BKC- acquisition of data, data analysis and interpretation, revision of paper; RLM- research design, data interpretation, paper revision; DRS- research design, data interpretation, paper revision; AFK- research design, data interpretation, paper revision; LJS- research design, data interpretation, paper revision, approval of submitted and final versions; JB- research design, data interpretation, paper revision, approval of submitted and final versions.

References

- 1.Keener JD, Galatz LM, Teefey SA, et al. A prospective evaluation of survivorship of asymptomatic degenerative rotator cuff tears. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2015;97:89–98. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.N.00099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neer CS., 2nd Impingement lesions. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1983:70–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nirschl RP. Rotator cuff tendinitis: basic concepts of pathoetiology. Instr Course Lect. 1989;38:439–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kannus P, Jozsa L. Histopathological changes preceding spontaneous rupture of a tendon. A controlled study of 891 patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1991;73:1507–1525. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seitz AL, McClure PW, Finucane S, et al. Mechanisms of rotator cuff tendinopathy: intrinsic, extrinsic, or both? Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 2011;26:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2010.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Millar NL, Wei AQ, Molloy TJ, et al. Cytokines and apoptosis in supraspinatus tendinopathy. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2009;91:417–424. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.91B3.21652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Soslowsky LJ, Thomopoulos S, Tun S, et al. Neer Award 1999. Overuse activity injures the supraspinatus tendon in an animal model: a histologic and biomechanical study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2000;9:79–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Soslowsky LJ, Carpenter JE, DeBano CM, et al. Development and use of an animal model for investigations on rotator cuff disease. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1996;5:383–392. doi: 10.1016/s1058-2746(96)80070-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reuther KE, Thomas SJ, Tucker JJ, et al. Overuse Activity in the Presence of Scapular Dyskinesis Leads to Shoulder Tendon Damage in a Rat Model. Ann Biomed Eng. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s10439-014-1137-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reuther KE, Sarver JJ, Schultz SM, et al. Glenoid cartilage mechanical properties decrease after rotator cuff tears in a rat model. J Orthop Res. 2012;30:1435–1439. doi: 10.1002/jor.22100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reuther KE, Thomas SJ, Evans EF, et al. Returning to overuse activity following a supraspinatus and infraspinatus tear leads to joint damage in a rat model. J Biomech. 2013;46:1818–1824. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2013.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reuther KE, Thomas SJ, Sarver JJ, et al. Effect of return to overuse activity following an isolated supraspinatus tendon tear on adjacent intact tendons and glenoid cartilage in a rat model. J Orthop Res. 2013;31:710–715. doi: 10.1002/jor.22295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reuther KE, Thomas SJ, Tucker JJ, et al. Disruption of the anterior-posterior rotator cuff force balance alters joint function and leads to joint damage in a rat model. J Orthop Res. 2014;32:638–644. doi: 10.1002/jor.22586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thomas SJ, Reuther KE, Tucker JJ, et al. Biceps detachment decreases joint damage in a rotator cuff tear rat model. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472:2404–2412. doi: 10.1007/s11999-013-3422-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kovacevic D, Gulotta LV, Ying L, et al. rhPDGF-BB Promotes Early Healing in a Rat Rotator Cuff Repair Model. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s11999-014-4020-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thomopoulos S, Hattersley G, Rosen V, et al. The localized expression of extracellular matrix components in healing tendon insertion sites: an in situ hybridization study. J Orthop Res. 2002;20:454–463. doi: 10.1016/S0736-0266(01)00144-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beason DP, Connizzo BK, Dourte LM, et al. Fiber-aligned polymer scaffolds for rotator cuff repair in a rat model. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21:245–250. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2011.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Connizzo BK, Yannascoli SM, Tucker JJ, et al. The detrimental effects of systemic Ibuprofen delivery on tendon healing are time-dependent. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472:2433–2439. doi: 10.1007/s11999-013-3258-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beason DP, Tucker JJ, Lee CS, et al. Rat rotator cuff tendon-to-bone healing properties are adversely affected by hypercholesterolemia. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23:867–872. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2013.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dolkart O, Liron T, Chechik O, et al. Statins enhance rotator cuff healing by stimulating the COX2/PGE2/EP4 pathway: an in vivo and in vitro study. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42:2869–2876. doi: 10.1177/0363546514545856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Manning CN, Kim HM, Sakiyama-Elbert S, et al. Sustained delivery of transforming growth factor beta three enhances tendon-to-bone healing in a rat model. J Orthop Res. 2011;29:1099–1105. doi: 10.1002/jor.21301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Archambault JM, Jelinsky SA, Lake SP, et al. Rat supraspinatus tendon expresses cartilage markers with overuse. J Orthop Res. 2007;25:617–624. doi: 10.1002/jor.20347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Attia M, Huet E, Gossard C, et al. Early events of overused supraspinatus tendons involve matrix metalloproteinases and EMMPRIN/CD147 in the absence of inflammation. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41:908–917. doi: 10.1177/0363546512473817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Attia M, Scott A, Duchesnay A, et al. Alterations of overused supraspinatus tendon: a possible role of glycosaminoglycans and HARP/pleiotrophin in early tendon pathology. J Orthop Res. 2012;30:61–71. doi: 10.1002/jor.21479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Castro Pochini A, Ejnisman B, de Seixas Alves MT, et al. Overuse of training increases mechanoreceptors in supraspinatus tendon of rats SHR. J Orthop Res. 2011;29:1771–1774. doi: 10.1002/jor.21320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Favata M. Scarless healing in the fetus: implications and strategies for postnatal tendon repair. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bey MJ, Song HK, Wehrli FW, et al. A noncontact, nondestructive method for quantifying intratissue deformations and strains. J Biomech Eng. 2002;124:253–258. doi: 10.1115/1.1449917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thomopoulos S, Williams GR, Gimbel JA, et al. Variation of biomechanical, structural, and compositional properties along the tendon to bone insertion site. J Orthop Res. 2003;21:413–419. doi: 10.1016/S0736-0266(03)00057-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Loppini M, Longo UG, Niccoli G, et al. Histopathological scores for tissue-engineered, repaired and degenerated tendon: a systematic review of the literature. Curr Stem Cell Res Ther. 2014;10:43–55. doi: 10.2174/1574888x09666140710110723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gimbel JA, Van Kleunen JP, Mehta S, et al. Supraspinatus tendon organizational and mechanical properties in a chronic rotator cuff tear animal model. J Biomech. 2004;37:739–749. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2003.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gimbel JA, Van Kleunen JP, Williams GR, et al. Long durations of immobilization in the rat result in enhanced mechanical properties of the healing supraspinatus tendon insertion site. J Biomech Eng. 2007;129:400–404. doi: 10.1115/1.2721075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]