Abstract

Influenza pandemics occur unpredictably when zoonotic influenza viruses with novel antigenicity acquire the ability to transmit amongst humans 1. Incompatibilities between avian virus components and the human host limit host range breaches. Barriers include receptor preference, virion stability and poor activity of the avian virus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase in human cells 2. Mutants of the heterotrimeric viral polymerase components, particularly PB2 protein, are selected during mammalian adaptation, but their mode of action is unknown 3–6. We show that a species-specific difference in host protein ANP32A accounts for the suboptimal function of avian virus polymerase in mammalian cells. Avian ANP32A possesses an additional 33 amino acids between the LRR and LCAR domains. In mammalian cells, avian ANP32A rescued the suboptimal function of avian virus polymerase to levels similar to mammalian adapted polymerase. Deletion of the avian-specific sequence from chicken ANP32A abrogated this activity whereas its insertion into human ANP32A, or closely related ANP32B, supported avian virus polymerase function. Substitutions, such as PB2 E627K, rapidly selected upon infection of humans with avian H5N1 or H7N9 influenza viruses, adapt the viral polymerase for the shorter mammalian ANP32A. Thus ANP32A represents an essential host partner co-opted to support influenza virus replication and is a candidate host target for novel antivirals.

The negative sense RNA genome of influenza virus is delivered into host cells associated with the viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase, a heterotrimeric complex of PB1, PB2 and PA proteins and the viral nucleoprotein NP. The viral ribonucleoprotein complex traffics to the cell nucleus where, in complex with various co-opted host factors, the viral polymerase directs transcription and replication of the genome 7. This intimate virus:host interaction is suboptimal for an avian influenza virus in mammalian cells, such that productive replication or onwards transmission do not occur until adaptive mutations are selected 3,4,8,9. The host range restriction of influenza A virus polymerase can be recapitulated in vitro, whereby functional viral polymerase, reconstituted by expression of PB1, PB2, PA and NP, directs amplification and expression of a model viral-like RNA 10. In mammalian cells, the low activity of reconstituted avian virus polymerase can be significantly increased by a single amino acid substitution (E627K) in PB2 11,12. In contrast, in avian cells, polymerases bearing either E or K at PB2 627 are active 11,16. Influenza A viruses that circulate in humans either have lysine at PB2 627 or, as in 2009 pandemic H1N1 virus, substitutions at residues 271, 590 and 591 13,14 that map close to 627 on the polymerase structure 15, suggesting a common mechanism of host adaptation.

We previously showed that heterokaryons formed by fusing human and avian cells supported avian virus polymerase activity suggesting that host range restriction was explained by a species-specific difference in a positive avian host factor that was either lacking or different in mammals 10. To identify this factor, we took advantage of a chicken genome radiation hybrid (RH) panel based on the Wg3H hamster cell line and harbouring different fragments of chicken chromosomes 17. Each RH clone was screened for the ability to support activity of a H5N1 avian influenza virus polymerase (A/turkey/England/50-92/91 virus (50-92)) compared with its human-adapted isoform bearing PB2 E627K. Four of 53 clones supported activity of the avian virus polymerase (Figure 1a). Due to instability of the chicken chromosome content, one positive clone lost this phenotype by passage 12. To identify chicken genes expressed in the positive RH clones but not in negatives, total RNA was analysed using an Affymetrix™ chicken gene array. The four early passage positive clones had 35 chicken genes in common (Figure 1b). After P12, the remaining positive hybrids shared only 12 genes in common, all present on a region of chicken chromosome 10 (Figure 1c and Extended Data Table 1). Genetic instability of the clones is revealed by PCA mapping analysis, as is variation between negative clones (Extended Data Fig 1).

Figure 1. Identification of a positive avian cellular factor that permits avian influenza virus polymerase activity in mammalian cells by screening radiation hybrid clones.

a, RH clones transfected with mouse-polI-firefly minigenome reporter, avian influenza virus H5N1 50-92 polymerase (either PB2 627E or PB2 627K) and Renilla expression control. Passage 1 clones black bars, Passage 12 clones grey bars. (Data as a ratio of PB2 627E/K polymerase activity (firefly normalised to Renilla); n=3 biological replicates; one-way ANOVA, comparisons to Wg3h, ****p<0.0001; error as SEM of the ratio). b, VENN diagram of microarray data analysis of P1 positive hybrid clones vs Parent Wg3h cells. c, VENN diagram of P12 positive hybrid clones vs parent and 365P1 (positive RH clone) vs 365P12 (reverted RH clone) (total gene numbers in brackets); Two-way ANOVA (variables: clone and passage number) adjusted by Benjamini–Hochberg multiple-testing correction (false discovery rate (FDR) of P<0.05). Statistically significant genes identified and those with fold-change values <±1.5 removed. d, Cloned chicken genes from chromosome 10 or chicken homologues of genes previously implicated with PB2 host range (underlined) expressed in 293T cells for 20hrs before transfection with pHOM1-firefly minigenome reporter, avian virus 50-92 polymerase (either PB2 627E (Black bars) or PB2 627K (grey bars)) and Renilla expression control. Luciferase activity was assayed after a further 24hrs. (Data are firefly activity normalised to Renilla; error as SEM; n=3 biological replicates; pattern of results consistent in at least three independent experiments).

We targeted candidate genes within this region and co-expressed each individually in human 293T cells with reconstituted H5N1 50-92 influenza virus polymerase. Expression of a single chicken gene, chANP32A (chicken Acidic (Leucine-rich) Nuclear Phosphoprotein 32 Family, Member A), rescued avian virus polymerase activity to levels similar to human-adapted PB2 627K viral polymerase (Figure 1d). All positive hybrid clones expressed chANP32A (Extended Data Fig. 2). Knockdown of chANP32A abrogated the ability of positive RH clone 476 to support avian virus polymerase, suggesting this single chicken gene was responsible for the phenotype (Extended Data Fig. 3). Chicken homologues of DDX17 and members of the importin alpha family previously implicated in host range restriction of influenza virus polymerase did not rescue avian virus polymerase activity in human cells (Figure 1d) 18,19.

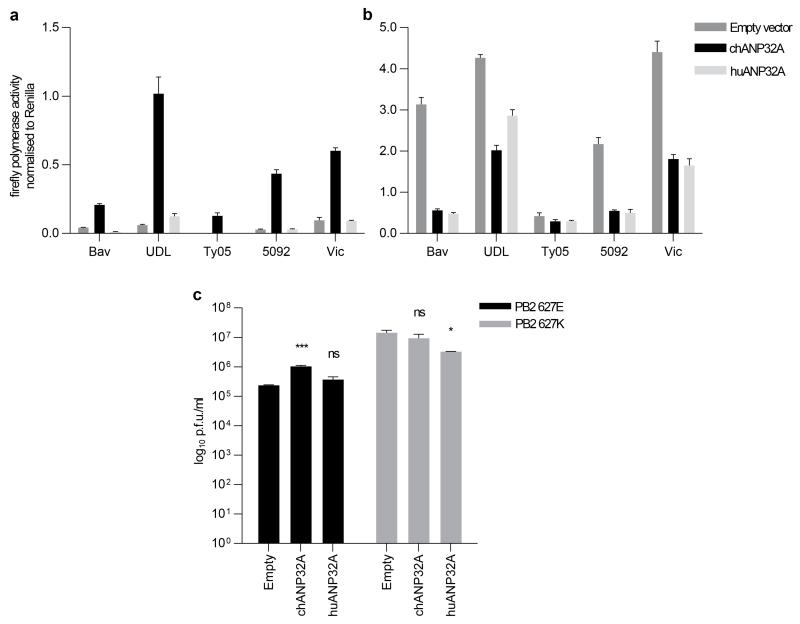

ANP32A is a member of a family of nuclear proteins implicated in multiple cellular pathways; including transcriptional regulation by chromatin remodelling, mRNA export and cell death 20. ANP32 proteins share conserved N terminal domains, comprised of leucine rich repeats (LRR) and C-terminal low complexity acidic regions (LCAR) comprised of 60-75% glutamic or aspartic acid (Figure 4a and Extended Data Fig. 8). We expressed cloned human homologue (huANP32A) as well as human and chicken genes for the related family member ANP32B. Expression of chANP32A, but not huANP32A, in human cells rescued activity of several different avian influenza polymerases including those from low (H1N1 A/duck/Bavaria/79 (Bav), H9N2 A/UDL/2008 (UDL)), and high (H5N1 (A/turkey/Turkey/05/2005 (Ty05) and A/turkey/England/50-92/91 (50-92)) pathogenicity avian viruses, and a human H3N2 virus (A/Victoria/3/75 (Vic)) when PB2 bore 627E (Extended Data Fig. 4). Expression of chANP32A but not huANP32A, chANP32B or huANP32B, increased levels of all three species of minigenome RNA produced by reconstituted avian viral polymerase in human cells (Figure 2a-c). Increase in levels of viral genomic RNA (vRNA) and complementary antigenomic RNA (cRNA) in the polymerase assay indicates that RNA replication, and not only mRNA transcription or stability, was enhanced by the expression of the chicken host factor in mammalian cells. Expression of chANP32A in human cells did not affect levels or nuclear accumulation of PB2, suggesting that its ability to support polymerase activity in the cell nucleus is not mediated by enhanced nuclear trafficking (Extended Data Fig. 5).

Figure 2. Expression of chANP32A in human cells rescues transcription and replication of avian influenza virus.

a-c, ch or huANP32A, ANP32B or empty vector were expressed for 20 hrs before transfection of avian virus 50-92 polymerase (either PB2 627E (black bars) or PB2 627K (grey bars)), and incubated at 37°C for 24hrs before qRT-PCR for luciferase gene of the viral minigenome reporter, vRNA (a), mRNA (b) and cRNA (c). d-f, 293T cells expressing chANP32A, huANP32A or empty vector for 20hrs before infection by avian influenza virus (H9N2 A/chicken/UDL-01/2008) virus (MOI 1.0), incubated at 37°C for 24hrs before qRT-PCR for viral segment 1; vRNA (d), mRNA (e) and cRNA (f). (Data expressed as fold change to empty vector, normalised to 18sRNA, calculated by ΔΔCT; error plotted as SEM; One-way ANOVA, comparisons to empty, ns= not significant, *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001; n=3 biological replicates, pattern of results consistent in at least three independent experiments). g, 293T cells expressing ch or huANP32A or empty vector for 20hrs before infection (MOI 0.1) with avian-like influenza virus (recombinant PR8 virus with H5N1 Ty05 polymerase, M and NS gene segments and PR8 HA and NA genes) bearing PB2 627E (black bars) or PB2 627K (grey bars). Cells incubated at 33°C and cell supernatant titrated for infectious virus 24hrs post infection on MDCK cells by plaque assay. (Data displayed as log10 plaque forming units/ml; One-way ANOVA, comparisons to empty vector, ns= not significant, **p<0.01 ****p<0.0001, n=3 biological replicates, pattern of results consistent in at least three independent experiments).

Additionally, expression of chANP32A enhanced avian virus replication in human cells. Levels of all three influenza RNA species derived from avian virus segment 1 were increased by expressed chANP32A but not huANP32A (Figure 2d-f). Moreover, the yield of infectious avian-like influenza virus was enhanced whether chANP32A was expressed in human cells at 33°C (Figure 2 g) or 37°C (Extended Data Fig. 4c). In contrast, chANP32A did not enhance yields of an isogenic PB2 627K recombinant virus, and over-expression of huANP32A reduced its titre (Figure 2g and Extended Data Fig. 4c).

We confirmed a role for ANP32A in supporting virus replication in avian cells. In chicken cells (DF-1, immortalized chicken fibroblasts), shRNA (Figure 3 a and Extended Data Fig. 6) and siRNA (Figure 3b ) targeting chANP32A decreased activity of avian virus polymerase (PB2 627E). Knockdown of ANP32A in DF-1 cells also decreased the yield of infectious avian-like influenza virus (Figure 3c).

Figure 3. Knockdown of ANP32 reveals avian influenza polymerase dependence on chANP32A and dependence on huANP32A and B in human cells by human adapted influenza polymerase.

a, DF-1 cells transduced with VSV-G lentiviral vectors delivering transgenes expressing puromycin and shRNA targeting chANP32A or Negative. Puromycin selected cells transfected with pCOM1-firefly minigenome reporter, avian 50-92 polymerase (627E), and Renilla expression control . b, siRNA (100nM) applied to DF-1 chANP32A shRNA cells. After 48hrs, cells transfected with avian 50-92 polymerase (627E), minigenome reporter and Renilla expression control. Luciferase activity measured 20hrs later. Knockdown in chicken DF-1 cells verified by immunoblotting using antibody against vinculin and chANP32A. c, DF-1 cells depleted of chANP32A by siRNA infected with avian-like influenza virus (PR8 virus bearing H5N1 Ty05 polymerase genes with PB2 627E, MOI 0.01). 24hrs later cell supernatants titrated for infectious virus by plaque assay on MDCK cells. d, 293T cells transduced with lentiviral vectors delivering transgenes expressing puromycin and shRNA targeting huANP32A, huANP32B, both huANP32A and B, or Negative. Puromycin selected cells transfected with, pHOM1-firefly minigenome reporter, human-adapted avian 50-92 polymerase (627K), and Renilla expression control.Luciferase activity measured after 20hrs. Knockdown in 293T cells verified immunoblotting using antibody against vinculin, huANP32A and huANP32B. (a,b&d, data are firefly activity normalised to Renilla, plotted as % of Negative or Allstars; error as SEM; One-way ANOVA comparisons to ALLStars or Negative, ns= not significant, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001; n=3 biological replicates). e, Puromycin selected A549 cells expressing shRNA against huANP32 A and/or B were infected with human (H3N2) virus A/England/691/2010 (MOI 0.1). After 24hrs, cell supernatants titrated by plaque assay on MDCK cells. (c&e, Data are % pfu relative to ALLStars or Negative; One-way ANOVA, comparisons to ALLStars or Negative, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001, n=3 biological replicates, pattern of results consistent in at least three independent experiments).

We next investigated whether the human homologues of ANP32A or B support activity of influenza polymerase in human cells. Human ANP32A and B were previously listed in the human influenza A virus interactome 21, and depletion of huANP32A and/or huANP32B from human cells decreased polymerase activity and replication of human influenza virus 22,23. We used sh or siRNA to target huANP32A and B in human cells. Human-adapted viral polymerase (50-92 PB2 627K) activity was reduced when levels of either ANP32A or B were decreased, and further reduced in cells from which both proteins were depleted, suggesting a dependence on both family members (Figure 3d and Extended Data Fig.7). Yields of influenza virus A/England/691/2010, a seasonal H3N2 human virus, were decreased in cells depleted of ANP32A and/or ANP32B (Figure 3e). We note with interest that both depletion and overexpression of human ANP32A or B were deleterious for polymerase activity and virus yields in human cells (Figure 2) which suggests that influenza virus relies on balanced expression of ANP32 proteins.

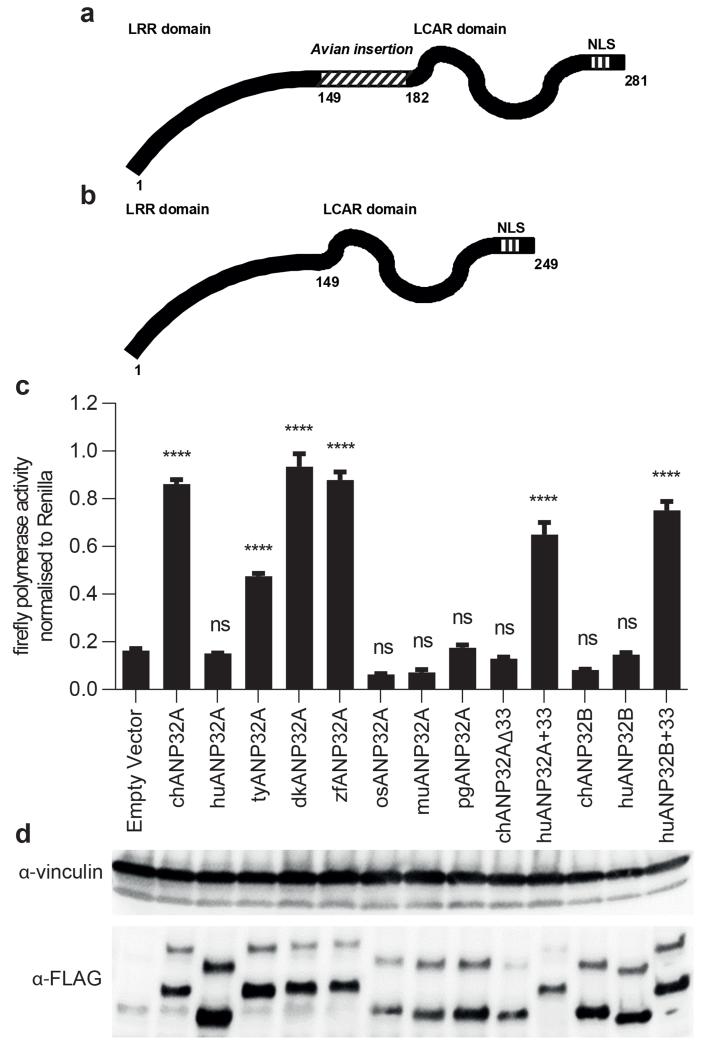

Sequence alignment of avian and mammalian ANP32A revealed that avian (except ratite) ANP32A harbours an additional 33 amino acids (176-208), derived partly by a repeat of amino acids 149-175, expressed from an additional exon absent from mammals and ostrich (Extended Data Fig. 8). Avian ANP32B does not contain the additional sequence (Extended Data Fig. 8). We cloned and FLAG-tagged ANP32A cDNA from chicken, turkey, duck, and zebrafinch, all of which encode homologues with the additional sequence, and also from ostrich, human, mouse, and pig, all of which were mammalian-like in length (Figure 4a, b and d). The four longer avian proteins increased avian, but not human-adapted, influenza virus polymerase activity in human cells (Figure 4c and Extended Data Fig. 9). In contrast, the ostrich protein, or any of the mammalian homologues, did not rescue avian virus polymerase activity. Interestingly, replication of avian influenza viruses in ostrich and other ratites selects for mammalian-adapted PB2 mutants 24.

Figure 4. Activity of avian influenza virus polymerase is dependent on a unique amino acid sequence present on avian ANP32A proteins.

a, chANP32A protein schematic with 33aa insertion relative to human homologue. b, huANP32A schematic representative of ANP32A from mammals, ostrich and of ANP32B. c, 293T cells transfected with FLAG-tagged ANP32 and after 20hrs transfected with, pHOM1-firefly minigenome reporter, avian 50-92 polymerase (627E) and Renilla expression control . Luciferase activity measured 24hrs later. (Data are PB2 627E polymerase activity normalised to Renilla; One-way ANOVA, comparisons to Empty vector, ns= not significant, ****p<0.0001; error plotted as SEM of the ratio; n=3 biological replicates; pattern of results consistent in at least three independent experiments). d. Immunoblot analysis of FLAG-tagged ANP32A constructs using antibody against FLAG peptide and vinculin.

Deletion of amino acids 176-208 from chANP32A abrogated its ability to support avian virus polymerase. Conversely, insertion of the additional avian-specific 33 amino acids bestowed upon either huANP32A or huANP32B the ability to support avian virus polymerase (Figure 4c and d).

In summary, we conducted a novel screen of chicken genome RH cells and identified a single chicken gene, ANP32A, which supports avian influenza virus polymerase activity in human cells. We suggest that avian influenza virus has co-evolved with its natural hosts, wild birds, to co-opt avian ANP32A as a host factor that supports its polymerase activity in the nucleus. The avian influenza polymerase cannot efficiently utilize shorter ANP32 proteins, such as ANP32B or mammalian ANP32A homologues, for this activity. Acquisition of host-adapting mutations, such as PB2 E627K, enables polymerase activity to be supported by the shorter ANP32 proteins typical of mammalian hosts. The underlying mechanism of avian influenza polymerase restriction in human cells has evaded researchers for decades. Others have previously demonstrated a role for PB2 residue 627 in its interaction with NP 12,25, and viral RNA promoter sequences 26,27 that may influence recognition of incoming vRNPS by RIG-I 28. The nature of residue 627 has also been linked with a PB2 dependency on specific importin family members 19,29. How these observations are linked with the species difference in host factor ANP32A we describe here remains to be elucidated.

Substitutions in PB2 are rapidly selected after avian influenza viruses enter mammalian hosts and PB2 adaptation is essential to support the pandemic potential of emerging avian influenza viruses. This stringent requirement for the virus to optimize replication efficiency in the human host suggests that disrupting the virus’ interaction with ANP32A may be a novel means for virus control.

Methods

Cells and cell culture

Chinese Hamster cell line (Wg3h), chicken genome RH clones (Laboratoire de génétique cellulaire, Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique, Castanet-Tolosan, France) 17, human embryonic kidney (293T) (ATCC), human lung adenocarcinoma epithelial cells (A549) (ATCC) and Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells (ATCC) were maintained in cell culture media (Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) (Biosera) and with 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Invitrogen)). Chicken fibroblast (DF-1) (ATCC) cells were maintained in DF-1 cell culture media (DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS, 5% tryptose phosphate broth (Sigma-Aldrich) and 0.1% Penicillin-streptomycin (Invitrogen)). Cell lines were maintained at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. Cell lines were authenticated by RT-PCR and verified negative for mycoplasma.

Microarray analysis

Total RNA was extracted from 1×106 cells that were of the same passage as those tested for polymerase, using an RNeasy kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. On-column DNA digestion was performed using RNase-free DNase (Qiagen) to remove contaminating genomic DNA. RNA samples were quantified using a Nanodrop Spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific) and checked for quality using a 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies). All RNA samples had an RNA integrity number (RIN) ≥ 9.8. Array hybridisation was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Affymetrix). Labelled samples were hybridized to the Affymetrix Chicken Gene 1.0 ST Arrays in a GeneChip Hybridization Oven for 16 h at 45°C and 60 rpm in an Affymetrix Hybridization Oven 645. After washing and staining, the arrays were scanned with the Affymetrix GeneChip Scanner 3000 7G. Gene-level expression signal estimates were derived from CEL files generated from raw data using the multi-array analysis (RMA) algorithm implemented from the Affymetrix GeneChip Command Console Software Version 3.0.1. Data Pre-Processing and filtering was done using Partek Software Version 6.6 and included: RMA background correction, quantile normalization across all chips in the experiment, log2 transformation and median polish summarization. Statistically significant genes were discovered by comparisons between the positive RH clones, parent cells and negative RH clones by two-way ANOVA (variables: clone and passage number) adjusted with the Benjamini–Hochberg multiple-testing correction (false discovery rate (FDR) of P<0.05). Statistically significant genes were identified and those with fold-change values <|±1.5| were removed.

Cloning of candidate cDNAs

Sequence specific primers were used to amplify targeted cellular transcripts of chicken genes from chromosome 10, including: ANP32A, RAB11A (Ras-related protein Rab-11A), TIPIN (TIMELESS Interacting Protein), RPL4 (Ribosomal Protein L4), PIAS1 (Protein Inhibitor Of Activated STAT, 1), TLE3 (Transducin-Like Enhancer Of Split 3), EIF3J (Eukaryotic Translation Initiation Factor 3, Subunit J) and CTDSPL2 (CTD (Carboxy-Terminal Domain, RNA Polymerase II, Polypeptide A) Small Phosphatase Like 2) from total RNA extracted from RH clone 476, using SuperScript® III One-Step RT-PCR System (Invitrogen). Chicken ANP32B, DDX17 (DEAD (Asp-Glu-Ala-Asp) Box Helicase 17), IMPα1, 3 and 7 (Importin α-1,3 and 7) cDNAs were amplified from RNA extracted from DF-1 cells. PCR products were cloned into the pCAGGS expression vector. cDNAs of full length ANP32A isoforms of several species were generated by gene synthesis (GeneArt® Strings™ DNA Fragments) and inserted into the pCAGGS expression vector, based on the following sequences: Chicken ANP32A (chANP32A) (Gallus gallus, XP_413932.3), Human ANP32A (huANP32A) (Homo sapiens, NP_006296.1), Zebra finch ANP32A (zfANP32A) (Taeniopygia guttata, XP_012424064.1), Duck ANP32A (dkANP32A) (Anas platyrhynchos, XP_005023024.1), Turkey ANP32A (tyANP32A) (Meleagris gallopavo, XP_010715918.1), Ostrich ANP32A (osANP32A) (Struthio camelus australis, XP_009665579.1), Pig ANP32A (pgANP32A) (Sus scrofa, XP_003121807.3), Mouse ANP32A (muANP32A) (Mus musculus, NP_033802.2), Chicken ANP32B (chANP32B) (Gallus gallus, NP_001026105.1) and Human ANP32B (huANP32B) (Homo sapiens, NP_006392.1). The sequence of dkANP32A was amended to contain the sequence encoding the intact N-terminus by comparison with duck RNA-seq data (from ENA_ERP005909) that had been de novo assembled (using CLC Genomic Workbench 7.5.1), where the appropriate contig was identified by BLASTX against the chicken ANP32A protein sequence. Furthermore, the duck sequence was confirmed by reverse-transcription of ANP32A mRNA derived from duck embryonic fibroblast cells and DNA sequencing. Mutants of these sequences were also generated by gene synthesis, as above, and included: chANP32AΔ33 (chANP32A with the ‘avian insertion’ deleted (aa176-208)), huANP32A+33 and huANP32B+33 (huANP32A and B with the avian sequence – VLSLVKDRDDKEAPDSDAEGYVEGLDDEEEDED– inserted after aa175 (huANP32A) and aa173 (huANP32B)). All plasmid constructs were verified by DNA sequencing. Primers and sequence information are available upon request.

Generation of recombinant and clinical Influenza A virus

Reverse genetics systems for the following virus strains were used in this study: PR8 (H1N1 A/Puerto Rico/8/1934) 30, UDL (H9N2 A/chicken/UDL-01/08) 31 (developed in collaboration with M. Iqbal, Pirbright Institute, UK) and Ty05 (H5N1 A/Turkey/Turkey/5/2005) (a kind gift from R. Fouchier, Erasmus University, Netherlands). The PB2 E627K substitution was made to 50-92, Ty05 (K627E) by overlapping PCR of the PB2 plasmid as previously described 11. Ty05:PR8 6:2 recombinant virus was generated with the HA and NA derived from PR8 and the internal genes of Ty05; virus rescue was performed by co-transfection of the 12-plasmid system: 8 polI plasmids as described above and 4 helper expression plasmids encoding A/Victoria/3/75 (VIC) polymerase components and NP expressed by the pCAGGS vector, as previously described 32,33. UDL virus rescue was performed by co-transfection of a 9 plasmid system including: 7 bidirectional pHW2000 plasmids 34 encoding PB2, PA, HA, NA, NP, NS and M genes, together with a polI plasmid encoding PB1 and a pCAGGS expression plasmid of the UDL-PB1 gene. Ty05 virus stocks were propagated in 9-day-old embryonated chicken eggs incubated at 37°C. UDL virus stocks were generated in MDCK cells with infection media (serum free DMEM supplemented with 1% penicillin-streptomycin and 1μg/ml TPCK-treated trypsin (Lorne Labs)) and incubated at 37°C. Clinical isolate A/England/691/2010 (H3N2) (Public Health England) was propagated in MDCK cells with infection media. Aliquots of infectious virus were stored at −80°C. Infectious titres were determined by plaque assay on MDCK cells.

Influenza A virus infection

293T cells were transfected with ANP32A (500ng, 24-well) using Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen) and after 20hrs infected with virus diluted in serum free DMEM for 1hr at 33 or 37°C (MOI as indicated in the relevant figure legends) and replaced with cell culture medium (for qRT-PCR analysis) or DMEM supplemented with 0.1% FCS and 1μg/ml TPCK trypsin (Worthington-Biochemical) (for infectious virus titres). shRNA A549 cells were infected with virus as for 293T cells, except infection media lacked FCS. Infected cell lysates and cell supernatants were harvested at 12 and/or 24hrs post-infection. Infectious titres were determined by plaque assay on MDCK cells.

Safety/biosecurity

All work with infectious agents was conducted in biosafety level 2 facilities, approved by the Health and Safety Executive of the UK and in accordance with local rules, at Imperial College London, UK.

Polymerase assay

Influenza polymerase activity was measured by use of a minigenome reporter which contains the firefly luciferase gene flanked by the non-coding regions of the influenza NS gene segment, transcribed from a species-specific polI plasmid with a mouse terminator sequence 35. The human and chicken polI minigenomes (pHOM1-Firefly and pCOM1-Firefly) are described previously 36 ; pMouse-PolI-Firefly was generated by substituting in the mouse polI promoter sequence 37. pCAGGS expression plasmids encoding each polymerase component and NP for 50-92 (H5N1 A/Turkey/England/50-92/91), Ty05, VIC and BAV (A/Duck/Bavaria/1/77) are described previously11,36,38. UDL PB1, PB2, PA and NP genes were sub-cloned into the pCAGGS plasmid. Mutagenesis of PB2 genes to encode PB2 627K or 627E was performed by overlapping PCR as described previously 11,36. All plasmid constructs were verified by DNA sequencing. Primers and sequence information are available upon request. To measure influenza polymerase activity, 293T cells were transfected in 48-well plates with pCAGGS plasmids encoding the PB1 (20ng), PB2 (20ng), PA (10ng) and NP (40ng) proteins, together with 20ng species-specific minigenome reporter and 10ng Renilla luciferase expression plasmid (pCAGGS-Renilla)39 as an internal control, using Lipofectamine 3000 transfection reagent (Invitrogen) according to manufacturers’ instructions. Wg3h, RH clones and DF-1 cells were transfected as 293T cells but with twice the concentration of DNA and using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Cells were incubated at 37°C. 20hrs after transfection, cells were lysed with 50 μl of passive lysis buffer (Promega), and firefly and Renilla luciferase bioluminescence was measured using a Dual-luciferase® system (Promega) with a FLUOstar Omega plate reader (BMG Labtech). The effect of cellular factors on influenza polymerase was examined by polymerase assay after expression of constructs (250ng) for 24hrs.

shRNA mediated silencing

Silencing was achieved by lentivirus delivery of shRNA encoding transgenes. Lentiviral vectors were generated using the TRC1.5-pLKO.1-puro plasmid (MISSION® Sigma-Aldrich) containing the shRNA sequence and puromycin selection gene. shRNA sequences for target genes were as follows: huANP32A (TRCN0000006905, 5’-CCGGCCTGAAGATGAGGGAGAAGATCTCGAGATCTTCTCCCTCATCTTCAGGTTTTT-3’ (target sequence, 5’-CCTGAAGATGAGGGAGAAGAT-3’)), huANP32B (TRCN0000077928, 5’-CCGGCCACCCAAAGAGCCAAAGAATCTCGAGATTCTTTGGCTCTTTGGGTGGTTTTTG-3’ (target sequence, 5’-CCACCCAAAGAGCCAAAGAAT-3’)), chANP32A (TRCN0000006902, 5’-CCGGCCTATTGTGATTTGACTGTTTCTCGAGAAACAGTCAAATCACAATAGGTTTTT-3’ (target sequence, 5’-CCTATTGTGATTTGACTGTTT-3’)) and Negative (SHC002, Non-Mammalian shRNA Control) (MISSION® Sigma-Aldrich). Lentiviruses were generated by co-transfection in 293T cells with pCMV-delta8.2 40, pCAGG-VSV G 41 and TRC1.5-pLKO.1-puro at a ratio of 1:0.25:1 using Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen), cell culture media was replaced after 16hrs at a reduced volume and supernatant harvested at 36hrs post-transfection before being filtered (0.45μm) and aliquots frozen at −80°C. 293T, A549 or DF-1 cells were transduced with lentiviral vectors for 16hrs before media was replaced. After 72hrs incubation, cells were split and cell culture media was replaced containing 0.5μg/ml puromycin (Invivogen). Cells were incubated a further 72hrs after selection before analysis.

siRNA mediated silencing

DF-1, 293T or RH clone 476 cells were transfected with 100nM of siRNA using HiPerFect transfection reagent in 48-well plates, according to manufacturer’s instructions (Qiagen). 48hrs later cells were transfected with polymerase and minigenome constructs and harvested after a further 20hrs, for luciferase quantification and knockdown analysis. Total RNA was extracted as described previously but with 100μl of cell lysate added to AVL buffer before continuing with the RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen). siRNAs for target genes were as follows:, AllStars Negative Control, huANP32A (SI02655212 FlexiTube), huANP32B (SI02655380 FlexiTube) (Qiagen), 50-92 NP (5’-AAGGAUCUUAUUUCUUCGGAG-3’), chANP32A (5’-GAGCTGGAATTCTTGAGTACA-3’) (custom RNA oligos, Sigma-Aldrich).

Quantification of chANP32A and B mRNA levels

Total RNA from RH clones and DF-1 cells were extracted using an RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen), following manufacturer’s instructions. During extraction of RNA, RNeasy columns were treated with RNase-Free DNase (Qiagen). RNA samples were quantified using a Nanodrop Spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific). Equal concentrations of RNA were subject to first strand synthesis using QuantiTect Reverse Transcription Kit (Qiagen) with primers specific for chANP32A (5’-CAACTGTAGGTCATACGAAGGC-3’) and chANP32B (5’-GGTGGCCTTGAAGTTCTAGC-3’). This product was then quantified with Mesa Green quantitative PCR (qPCR) MasterMix Plus for SYBR Assay I dTTP (Eurogentec) using the primers for first strand synthesis together with chANP32A (5’-GTTTGCAACTGAGGCTAAGC-3’) and chANP32B (5’-ATGAGCATCGTCACCTCGC-3’). Real-time quantitative PCR analysis was performed (Applied Biosystems ® ViiA™ 7 Real-Time PCR System) and absolute copy numbers of either chANP32A or B calculated using a standard curve of known concentrations of the corresponding cDNA expression plasmid. Primers were designed to be specific to their target transcripts by using BLASTX against both the hamster and chicken genomes.

Quantification of RNA generated by influenza polymerase

Purified total RNA (1000ng) was subject to first-strand cDNA synthesis with gene specific primers, oligo(dT)20 or random hexamers (to amplify mRNA) using SuperScript® III (Invitrogen) followed by RNaseH treatment (Invitrogen). Primer design was based on Obayashi et al. (2008) 42 for quantification of RNA species of the luciferase minigenome driven by reconstituted polymerase, and UDL PB2 RNA species were quantified using a tagged-primer system adapted from Kawakami et al. (2011) 43. First strand primers included: luciferase vRNA (5’- TATGAACATTTCGCAGCCTACCGTAGTGTT-3’), luciferase cRNA (5’-AGTAGAAACAAGGGTG-3’), luciferase mRNA (Oligo(dT)20), UDL PB2 vRNA (5’-GGCCGTCATGGTGGCGAAT(tag)GATGCGTGATGTATTGGGAAC-3’), UDL PB2 cRNA (5’-GCTAGCTTCAGCTAGGCATC(tag)AGTAGAAACAAGGTCGTT-3’), UDL PB2 mRNA (Oligo(dT)20) and 18S ribosomal RNA (Random Hexamers (Invitrogen)). After first strand synthesis, 1ul of cDNA was subject to real-time quantitative PCR analysis with a gene specific primer pair using SYBR green PCR mix (Applied Biosystems) and analysed on the Applied Biosystems ® ViiA™ 7 Real-Time PCR System. Gene specific primer pairs were as follows: Luciferase gene (5’-CCGGAATGATTTGATTGCCA-3’ and 5’-TATGAACATTTCGCAGCCTACCGTAGTGTT-3’), UDL PB2 vRNA (5’-GGCCGTCATGGTGGCGAAT(tag)-3’ and 5’-CCTCTCAACACTGCAGATTCC-3’), UDL PB2 cRNA (5’-GCTAGCTTCAGCTAGGCATC(tag)-3’ and 5’-GGAATCTGCAGTGTTGAGAGG-3’), UDL PB2 mRNA (5’-GATGCGTGATGTATTGGGAAC-3’ and 5’- CCTCTCAACACTGCAGATTCC-3’) and 18S ribosomal RNA (5’-GCAAATTACCCACTCCCG-3’ and 5’-CTGCAGCAACTTTAATATACGC-3’). Fold change RNA to PB2 627E with Empty vector was calculated by ΔΔCT including normalisation to ct values of 18S ribosomal RNA.

Immunoblot analysis

Cells were lysed in Passive Lysis buffer (Promega) or NP40 lysis buffer (for cellular fractionation) and prepared in Laemmli 2xbuffer (Sigma-Aldrich). Cell proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE using Mini-PROTEAN® TGX™ Precast Gels (Bio-Rad). Immunoblotting was carried out using the following primary antibodies: α-chANP32A rabbit polyclonal (LS-B10851, LifeSpan BioSciences, Inc.), α-huANP32A rabbit polyclonal (AB51013, Abcam), α-huANP32B rabbit monoclonal (AB184565, Abcam), α-vinculin rabbit monoclonal (AB129002, Abcam), α-FLAG® M2 mouse monoclonal (F1804 or F3165, Sigma-Aldrich), α-PB2 rabbit polyclonal (2N580, a kind gift from Paul Digard, Roslin Institute), and followed with secondary horseradish peroxidase-conjugated (HRP) antibodies: α-mouse IgG (H/L):HRP goat polyclonal (STAR117P, AbD Serotec) and α-rabbit IgG:HRP sheep polyclonal (STAR54, AbD Serotec). For quantification of cellular fractions, the following secondary antibodies were used: α-rabbit IgG (H/L):DyLight™ 800 (5151P, Cell signalling) and α-mouse IgG (H/L):DyLight™ 680 (5470P, Cell signalling). Protein bands were visualised by chemiluminescence (ECL+ western blotting substrate, Pierce) using a FUSION-FX imaging system (Vilber Lourmat).

Cellular Fractionation

293T cells were transfected with empty vector or ANP32 plasmid together with the polymerase complex and NP of 50-92 (PB2 627E) and pHOM1-firefly minigenome reporter. After 24hrs, cells monolayers were washed in ice-cold PBS and lysed in 0.1% NP40 buffer (50mM Tris pH 7.5, 150mM NaCl, 0.1% NP40 and protease inhibitors (EDTA-free COMPLETE tablet (Roche)). Total lysates were centrifuged at 228g for 5min at 4°C. Supernatant was removed (Cytoplasmic fraction) and the nuclear pellet was resuspended in 1% NP40 (as above) and subject to syringing with a 25G needle. Fractions were analysed by immunoblotting.

Bioinformatic and statistical analysis

Analysis of Microarray data was performed as previously mentioned, using Affymetrix GeneChip Command Console Software Version 3.0.1. and Partek Software Version 6.6. Statistical analysis of biological replicates was performed by One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparison analysis or Two-way ANOVA with Šidák multiple comparison analysis, using GraphPad Prism 6. Sequence alignments were performed using Geneious R6 software. Quantification of immunoblots was performed using Image Studio Lite V5.2.

Extended Data

Extended Data Figure 1. Analysis of mRNAs by PCA mapping reveals diversity of the radiation hybrid clones and their genetic instability during cell passage.

Each sphere represents a microarray sample. The percentage values in the axes parentheses designate proportion of overall variance as described by each PC. PC1 principal component 1 (X-axis); PC2 principal component 2 (Y-axis); PC3 principal component 3 (Z-axis). PC1 describes the predominant amount of variance (15.6%). Selection of negative clones (red), parent Wg3H cells (blue) and positive clones: 377 (purple), 386 (orange) and 365 (green) and 476 (cyan) arrays are distinguished by colour, and passage numbers 1 and 12 are distinguished by the size of spheres. Negative arrays are dispersed, while parent cells are accumulated further to the right of PC1 and upwards of PC2. Positive clones show distinct variability in their location while passaging reduced their separation from parent cells. This analysis accompanies Figure 1.

Extended Data Figure 2. Confirmation of chANP32A and chANP32B expression in RH clones by qRT-PCR.

RNA was extracted from the RH clones after testing for influenza polymerase activity and analysed by microarray for chicken transcripts. The same RNA was used to validate identification of ANP32A by confirming the level of expression of ANP32A (and ANP32B as control) in the parent Wg3h cells, positive clones, passaged positive clones and a selection of negative clones. a, Copy numbers of chANP32A mRNA were calculated by qRT-PCR against a standard curve generated with chANP32A cDNA using primers specific for chANP32A. b, Copy number of ANP32B mRNA were measured by qRT-PCR against a standard curve generated with chANP32B cDNA using primers specific for chANP32B. This analysis accompanies Figure 1.

Extended Data Figure 3. Knockdown of chANP32A in positive RH clone 476 diminished the ability to support avian influenza polymerase activity.

a, Positive RH clone 476 cells were transfected with 100nM of siRNA targeting NP, chANP32A or no target (Allstars). After 48hrs cells were transfected with mouse-polI-firefly minigenome reporter, avian influenza polymerase (H5N1 50-92) with either PB2 627E or 627K, Renilla control and either empty plasmid or codon optimised chANP32A (codon optimization according to algorithm by Geneart with manual editing). Luciferase activity was measured after a further 24hrs. (Errors are displayed as SEM; n=3 biological replicates). b, Knockdown of chANP32A was confirmed by qRT-PCR of RNA extracted from siRNA treated cells, calculated using a standard curve generated with chANP32A cDNA, using primers specific for chANP32A (Errors are displayed as SEM; n=3 biological replicates). This analysis accompanies Figure 1.

Extended Data Figure 4. Expression of chANP32A in human cells permits influenza polymerase activity of several avian influenza polymerases and an avianised human influenza polymerase and increases avian virus replication.

293T cells were transfected with empty vector, chANP32A or huANP32A. a&b. 20hrs later, cells were transfected with pHOM1-firefly minigenome reporter, and the polymerase set from low pathogenicity avH1N1 (Bav) or H9N2 (UDL), highly pathogenic H5N1 (50-92), H5N1 (Ty05), or huH3N2 (Vic) viruses, with either PB2 627E (a) or 627K (b) and Renilla expression control. After a further 24hrs luciferase activity was measured. (Data are mean PB2 627E or K polymerase activity normalised to Renilla; error plotted as SEM of the ratio; n=3 biological replicates; pattern of results consistent in at least three independent experiments). This analysis accompanies Figure 1. c. 20hrs after transfection with ch or huANP32A or empty vector, cells were infected with avian-like influenza virus (H5N1Ty05:PR8 6:2 recombinant virus) (MOI 0.1) bearing PB2 627E (black bars) or PB2 627K (grey bars). Infected cells were incubated at 37°C and cell supernatant titrated for infectious virus at 24hrs post infection on MDCK cells by plaque assay.(Data displayed as log10 plaque forming units/ml; One-way ANOVA, comparisons to empty vector, ns= not significant, *p<0.05 ***p<0.001, n=3 biological replicates, pattern of results consistent in at least three independent experiments). This analysis accompanies Figure 2.

Extended Data Figure 5. chANP32A does not alter expression or nuclear accumulation of avian PB2 protein in human cells.

293T cells were transfected with pHOM1-firefly minigenome, avian influenza polymerase and NP of H5N1 50-92 (PB2 627E) together with empty vector, chANP32A or chANP32AΔ33 or cells were untransfected (Mock). Cell monolayers were harvested after 24hrs and lysed in 0.1% NP40 lysate buffer and total fractions taken before centrifugation to generate a nuclear pellet and cytoplasmic fraction. Nuclear pellets were resuspended in 1% NP40 buffer. a. Protein levels of vinculin (cytoplasmic marker) and lamin B (nuclear marker) and of PB2 in total, nuclear or cytoplasmic fractions were analysed by immunoblotting. b. Total lysates were immunoblotted for vinculin, PB2 and FLAG peptide. c. Immunoblots were quantified using Image Studio Lite V5.2. The ratio of nuclear to cytoplasmic PB2 was calculated by dividing the ratio of PB2 to vinculin by the ratio of PB2 to lamin B from the cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions respectively. Data are the mean ratios from three independent experiments (excepting chANP32Δ33 for which only 2 data points were available), error bars are SEM. Data are not statistically significantly different by One-way ANOVA. This analysis accompanies Figure 2.

Extended Data Figure 6. Quantification of knockdown of chANP32A in chicken cells.

DF-1 cells were transduced with VSV-G lentiviral vectors that delivered a transgene expressing shRNA directed against chANP32A or a negative sequence and the puromycin gene. Puromycin selected cells were transfected with siRNA (100nM) (underlined). RNA was extracted from untreated shRNA cells and siRNA-treated shRNA cells. Knockdown of chANP32A was quantified by qRT-PCR of the extracted RNA, calculated using a standard curve generated with chANP32A cDNA, using primers specific for chANP32A. Fold decrease of RNA copies is displayed as compared to Negative shRNA DF-1 or ALLstars treated chANP32A shRNA DF-1 cells. (Error displayed as SEM; n=3 biological replicates). This analysis accompanies experiments in Figure 3a-c.

Extended Data Figure 7. siRNA knockdown demonstrates that human adapted influenza polymerase activity is dependent on huANP32A and huANP32B in human cells.

a, 293T cells were transfected with siRNA (100nM) against NP, huANP32A, huANP32B or both huANP32A and huANP32B (50nM each). After 48hrs, cells were transfected with pHOM1-firefly minigenome, human-adapted avian influenza polymerase (H5N1 50-92 PB2 627K), and Renilla expression control. Luciferase activity was measured after a further 24hrs. (Data are firefly activity normalised to Renilla, plotted as % of Allstars; error as SEM; One-way ANOVA comparisons to Allstars, ****p<0.0001; n=3 biological replicates). b, Knockdown of gene targets was verified by immunoblotting using antibody against vinculin, huANP32A and huANP32B. This analysis accompanies Figure 3 e and f.

Extended Data Figure 8. Alignment of ANP32A proteins reveals significant homology except for an extra 33aa sequence in birds that is absent in mammals and ostrich and lacking from ANP32B family members.

The protein sequences of ANP32A for chicken, duck, zebra finch, turkey, ostrich, human, mouse and pig together with sequences of ANP32B for chicken and human were aligned using Geneious R6 software. chANP32A is set as the reference sequence, and colours represent similarity of amino acid identity (Black=100%, dark grey=80-100%, light grey=60-80%, white=<60%). Gaps are annotated by dashes. Residue numbers correspond to chANP32A. The 33aa sequence found in avian species is situated between residues 176-208.This analysis accompanies Figure 4.

Extended Data Figure 9. Expression of ANP32A and B proteins reduced human-adapted influenza polymerase activity in human cells.

293T cells were transfected with FLAG-tagged ANP32 constructs and after 20hrs transfected with pHOM1-firefly minigenome reporter, human-adapted influenza polymerase (H5N1 50-92 with PB2 627K, together with Renilla expression control. Cells were assayed for luciferase activity 24hrs later. (Data are PB2 627K polymerase activity normalised to Renilla; One-way ANOVA, all constructs were significantly reduced compared to empty vector (p<0.0001); error plotted as SEM of the ratio; n=3 biological replicates; pattern of results consistent in at least three independent experiments).These data relate to Figure 4.

Extended Data Table 1. Genes common between the avian influenza polymerase positive radiation hybrid cells.

Microarray analysis of RNA extracted from RH clones revealed the expression of chicken genes. The gene list from Venn1 shows common genes between the P1 positive hybrid clones when compared to Parent Wg3h hamster cells. The gene list from Venn2 shows common genes between P12 positive hybrid clones when compared to parent and 365P1 (positive RH clone) vs 365P12 (reverted RH clone). This analysis accompanies the microarray analysis Venn diagrams Figure 1b and c.

| Gene Name | Chromosome | |

|---|---|---|

| Venn 1 | IQSEC3 | 1 |

| CCDC77 | 1 | |

| WNK1 | 1 | |

| KDM5A | 1 | |

| MAP2K1 | 10 | |

| ZWILCH | 10 | |

| PIAS1 | 10 | |

| FEM1B | 10 | |

| GLCE | 10 | |

| KIF23 | 10 | |

| SPG11 | 10 | |

| TIPIN | 10 | |

| RPL4 | 10 | |

| CLN6 | 10 | |

| ANP32A | 10 | |

| MORF4L1 | 10 | |

| EIF3J | 10 | |

| CASC4 | 10 | |

| BLM | 10 | |

| NUB1 | 2 | |

| Unannotated | 2 | |

| RBM33 | 2 | |

| WDR48 | 2 | |

| PAXIP1 | 2 | |

| Unannotated | 4 | |

| HPRT1 | 4 | |

| DDX26B | 4 | |

| SLC9A6 | 4 | |

| HTATSF1 | 4 | |

| LOC422249 | 4 | |

| FAM122B | 4 | |

| MOSPD1 | 4 | |

| MMGT1 | 4 | |

| MIR1726 | 6 | |

| LOC430470 | Uncharacterised | |

|

| ||

| Venn 2 | MAP2K1 | 10 |

| PIAS1 | 10 | |

| FEM1B | 10 | |

| GLCE | 10 | |

| KIF23 | 10 | |

| SPG11 | 10 | |

| TIPIN | 10 | |

| CLN6 | 10 | |

| ANP32A | 10 | |

| EIF3J | 10 | |

| CASC4 | 10 | |

| BLM | 10 | |

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank G. Maertens, J. Stech, R. Fouchier, A. Cauldwell, G. Roche, J. McCauley, D. Huntley, A. Vaughan, V. Nair and H. Shelton for provision of reagents, advice and discussions. This work was funded by BBSRC sLoLa BB/K002465/1 “Developing Rapid Responses to Emerging Virus Infections of Poultry (DDREVIP)” which funds J.L. and E.G., B.M. was funded by a Wellcome Trust studentship. R.F. and O.M. were funded by a Wellcome Trust Programme Grant (087039/Z/08/Z). O.M. was funded by MRC (G0600006). M.I. was funded by a BBSRC Avian Diseases Programme Grant (BBS/E/I/00001708).

Footnotes

Author Information

The microarray data have been submitted to The European Bioinformatics Institute (EBI) (http://www.ebi.ac.uk) under accession number E-MTAB-3643.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Neumann G, Kawaoka Y. Transmission of influenza A viruses. Virology. 2015;479-480:234–46. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2015.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cauldwell AV, Long JS, Moncorgé O, Barclay WS. Viral determinants of influenza A virus host range. J. Gen. Virol. 2014;95:1193–210. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.062836-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Almond JW. A single gene determines the host range of influenza virus. Nature. 1977;270:617–8. doi: 10.1038/270617a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Subbarao EK, London W, Murphy BR. A single amino acid in the PB2 gene of influenza A virus is a determinant of host range. J. Virol. 1993;67:1761–4. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.4.1761-1764.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Naffakh N, Tomoiu A, Rameix-Welti M-A, van der Werf S. Host restriction of avian influenza viruses at the level of the ribonucleoproteins. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2008;62:403–24. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.62.081307.162746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mänz B, Schwemmle M, Brunotte L. Adaptation of avian influenza A virus polymerase in mammals to overcome the host species barrier. J. Virol. 2013;87:7200–9. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00980-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eisfeld AJ, Neumann G, Kawaoka Y. At the centre: influenza A virus ribonucleoproteins. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2014 doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3367. doi:10.1038/nrmicro3367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Steel J, Lowen AC, Mubareka S, Palese P. Transmission of influenza virus in a mammalian host is increased by PB2 amino acids 627K or 627E/701N. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000252. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van Hoeven N, et al. Human HA and polymerase subunit PB2 proteins confer transmission of an avian influenza virus through the air. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2009;106:3366–3371. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813172106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moncorgé O, Mura M, Barclay WS. Evidence for avian and human host cell factors that affect the activity of influenza virus polymerase. J. Virol. 2010;84:9978–86. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01134-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Long JS, et al. The effect of the PB2 mutation 627K on highly pathogenic H5N1 avian influenza virus is dependent on the virus lineage. J. Virol. 2013;6899 doi: 10.1128/JVI.01399-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mehle A, Doudna J. a. An inhibitory activity in human cells restricts the function of an avian-like influenza virus polymerase. Cell Host Microbe. 2008;4:111–22. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bussey K. a, Bousse TL, Desmet E. a, Kim B, Takimoto T. PB2 residue 271 plays a key role in enhanced polymerase activity of influenza A viruses in mammalian host cells. J. Virol. 2010;84:4395–406. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02642-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mehle A, Doudna J. a. Adaptive strategies of the influenza virus polymerase for replication in humans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2009;106:21312–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911915106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pflug A, Guilligay D, Reich S, Cusack S. Structure of influenza A polymerase bound to the viral RNA promoter. Nature. 2014 doi: 10.1038/nature14008. doi:10.1038/nature14008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Massin P, van der Werf S, Naffakh N. Residue 627 of PB2 is a determinant of cold sensitivity in RNA replication of avian influenza viruses. J. Virol. 2001;75:5398–404. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.11.5398-5404.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morisson M, et al. ChickRH6: a chicken whole-genome radiation hybrid panel. Genet. Sel. Evol. 2002;34:521–533. doi: 10.1186/1297-9686-34-4-521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bortz E, et al. Host- and Strain-Specific Regulation of Influenza Virus Polymerase. MBio. 2011;2:1–10. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00151-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gabriel G, et al. Differential use of importin-α isoforms governs cell tropism and host adaptation of influenza virus. Nat. Commun. 2011;2:156. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reilly PT, Yu Y, Hamiche A, Wang L. Cracking the ANP32 whips: important functions, unequal requirement, and hints at disease implications. Bioessays. 2014;36:1062–71. doi: 10.1002/bies.201400058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bradel-Tretheway BG, et al. Comprehensive proteomic analysis of influenza virus polymerase complex reveals a novel association with mitochondrial proteins and RNA polymerase accessory factors. J. Virol. 2011;85:8569–81. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00496-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Watanabe T, et al. Influenza Virus-Host Interactome Screen as a Platform for Antiviral Drug Development. Cell Host Microbe. 2014;16:795–805. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sugiyama K, Kawaguchi A, Okuwaki M, Nagata K. pp32 and APRIL are host cell-derived regulators of influenza virus RNA synthesis from cRNA. Elife. 2015 doi: 10.7554/eLife.08939. doi:10.7554/eLife.08939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shinya K, et al. Ostrich involvement in the selection of H5N1 influenza virus possessing mammalian-type amino acids in the PB2 protein. J. Virol. 2009;83:13015–13018. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01714-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rameix-Welti M-A, Tomoiu A, Dos Santos Afonso E, van der Werf S, Naffakh N. Avian Influenza A virus polymerase association with nucleoprotein, but not polymerase assembly, is impaired in human cells during the course of infection. J. Virol. 2009;83:1320–31. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00977-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Crescenzo-Chaigne B, van der Werf S, Naffakh N. Differential effect of nucleotide substitutions in the 3’ arm of the influenza A virus vRNA promoter on transcription/replication by avian and human polymerase complexes is related to the nature of PB2 amino acid 627. Virology. 2002;303:240–252. doi: 10.1006/viro.2002.1637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Paterson D, Te Velthuis AJW, Vreede FT, Fodor E. Host Restriction of Influenza Virus Polymerase Activity by PB2 627E Is Diminished on Short Viral Templates in a Nucleoprotein-Independent Manner. J. Virol. 2014;88:339–44. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02022-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weber M, et al. Influenza virus adaptation PB2-627K modulates nucleocapsid inhibition by the pathogen sensor RIG-I. Cell Host Microbe. 2015;17:309–19. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2015.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Resa-Infante P, et al. The host-dependent interaction of α-importins with influenza PB2 polymerase subunit is required for virus RNA replication. PLoS One. 2008;3 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Additional references for methods

- 30.Whiteley A, et al. Generation of candidate human influenza vaccine strains in cell culture - rehearsing the European response to an H7N1 pandemic threat. Influenza Other Respi. Viruses. 2007;1:157–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-2659.2007.00022.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Iqbal M, Yaqub T, Mukhtar N, Shabbir MZ, McCauley JW. Infectivity and transmissibility of H9N2 avian influenza virus in chickens and wild terrestrial birds. Vet. Res. 2013;44 doi: 10.1186/1297-9716-44-100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Elleman CJ, Barclay WS. The M1 matrix protein controls the filamentous phenotype of influenza A virus. Virology. 2004;321:144–53. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2003.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Neumann G, et al. Generation of influenza A viruses entirely from cloned cDNAs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1999;96:9345–50. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.16.9345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hoffmann E, Neumann G, Kawaoka Y, Hobom G, Webster RG. A DNA transfection system for generation of influenza A virus from eight plasmids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2000;97:6108–13. doi: 10.1073/pnas.100133697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pleschka S, et al. A plasmid-based reverse genetics system for influenza A virus. J. Virol. 1996;70:4188–92. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.6.4188-4192.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moncorg O, et al. Investigation of influenza virus polymerase activity in pig cells. J. Virol. 2013;87:384–94. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01633-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Flick R, Pettersson RF. Reverse genetics system for Uukuniemi virus (Bunyaviridae): RNA polymerase I-catalyzed expression of chimeric viral RNAs. J. Virol. 2001;75:1643–1655. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.4.1643-1655.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Howard W, et al. Development of a reverse genetics system enabling the rescue of recombinant avian influenza virus A/Turkey/England/50-92/91 (H5N1) Avian Dis. 2007;51:393–5. doi: 10.1637/7645-050906R1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cauldwell AV, Moncorgé O, Barclay WS. Unstable polymerase-nucleoprotein interaction is not responsible for avian influenza virus polymerase restriction in human cells. J. Virol. 2013;87:1278–84. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02597-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Naldini L, Blömer U, Gage FH, Trono D, Verma IM. Efficient transfer, integration, and sustained long-term expression of the transgene in adult rat brains injected with a lentiviral vector. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1996;93:11382–11388. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ulm JW, Perron M, Sodroski J, C. Mulligan R. Complex determinants within the Moloney murine leukemia virus capsid modulate susceptibility of the virus to Fv1 and Ref1-mediated restriction. Virology. 2007;363:245–255. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.09.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Obayashi E, et al. The structural basis for an essential subunit interaction in influenza virus RNA polymerase. Nature. 2008;454:1127–1131. doi: 10.1038/nature07225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kawakami E, et al. Strand-specific real-time RT-PCR for distinguishing influenza vRNA, cRNA, and mRNA. J. Virol. Methods. 2011;173:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2010.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]