Highlights

-

•

Children between 5 and 8 years performed a sentence comprehension task.

-

•

Their structural images were analyzed using voxel-based morphometry.

-

•

Gray matter in inferior temporal and frontal areas predicts thematic role assignment.

-

•

Left temporo-parietal area's gray matter predicts working memory-related performance.

Keywords: Sentence comprehension, VBM, Brain development, Language-relevant brain areas, Verbal working memory

Abstract

Prior structural imaging studies found initial evidence for the link between structural gray matter changes and the development of language performance in children. However, previous studies generally only focused on sentence comprehension. Therefore, little is known about the relationship between structural properties of brain regions relevant to sentence processing and more specific cognitive abilities underlying complex sentence comprehension. In this study, whole-brain magnetic resonance images from 59 children between 5 and 8 years were assessed. Scores on a standardized sentence comprehension test determined grammatical proficiency of our participants. A confirmatory factory analysis corroborated a grammar-relevant and a verbal working memory-relevant factor underlying the measured performance. Voxel-based morphometry of gray matter revealed that while children's ability to assign thematic roles is positively correlated with gray matter probability (GMP) in the left inferior temporal gyrus and the left inferior frontal gyrus, verbal working memory-related performance is positively correlated with GMP in the left parietal operculum extending into the posterior superior temporal gyrus. Since these areas are known to be differentially engaged in adults’ complex sentence processing, our data suggest a specific correspondence between children's GMP in language-relevant brain regions and differential cognitive abilities that guide their sentence comprehension.

1. Introduction

Compared to other species, humans show a prolonged phase of brain functional specialization that allows the brain to be shaped by postnatal experience. This delayed time course in brain maturation provides more time for learning processes (Johnson, 2001), and the delayed prefrontal maturation is especially suggested to be an adaptation of the human brain necessary for the development of social and linguistic conventions (Thompson-Schill et al., 2009). Although children acquire basic principles of their native language incredibly fast, the ability to process complex sentences develops rather late. In developmental literature, it is discussed whether this can be attributed to lack of linguistic competence (e.g., Sheldon, 1974, Tavakolian, 1981), lack of experience (e.g., Diessel and Tomasello, 2005), or limitations in processing capacities (e.g., Goodluck and Tavakolian, 1982). However, the relation between the physical growth of the brain and development of cognitive milestones such as complex sentence processing remains largely unclear. Brain volume drastically increases early in life, and at 6 years of age children have reached approximately 90% of the adult brain volume (Courchesne et al., 2000, Lenroot and Giedd, 2006, Reiss et al., 1996). This structural increase originates from exceeding progressive changes such as an overgrowth of cell bodies (Petanjek et al., 2008), dendritic sprouting (Simonds and Scheibel, 1989), and an overgrowth of synaptic connections (Huttenlocher and de Courten, 1987, Rakic et al., 1986) in the gray as well as myelination (Yakovlev and Lecours, 1967) in white matter compartments. However, during preadolescence, the developmental pattern of gray matter is inverted and maturation is generally defined as a loss of gray matter density (Giedd et al., 1999, Giedd and Rapoport, 2010, Gogtay et al., 2004, Gogtay and Thompson, 2010, Lenroot and Giedd, 2006, Raznahan et al., 2011, Sowell et al., 2003, Taki et al., 2013). Onset and rate of gray matter loss is region-specific and follows a functional maturation sequence, starting with gray matter reduction in early-maturing primary sensorimotor areas, followed by gray matter reduction in late-maturing higher-order association areas (Gogtay et al., 2004, Brain Development Cooperative Group, 2012). While progressive changes in the cortical development are assumed to provide the basis for neural plasticity and thus maximal learning opportunities (Johnson, 2001, Simonds and Scheibel, 1989), regressive changes in the cortex, such as synaptic pruning (Rakic et al., 1986), have been related to a decline of the brain's ability to adapt to environmental input during development (Huttenlocher, 2002).

As the phylogenetic evolutionary development of the brain has been associated with the evolvement of language, it is suggested that the ontogenetic maturation, especially of the prefrontal cortex, can be related to language acquisition (e.g., Thompson-Schill et al., 2009). Prior structural imaging work found initial evidence for the link between structural gray matter changes and the development of language performance in children: Infants’ gray matter maturation of the right cerebellum and the right hippocampus was found to correlate with later language competence (Deniz Can et al., 2013). The receptive and productive phonological skills of children aged between 5 and 11 years correlate with measurements of gray matter probability (GMP) in the left inferior frontal gyrus (IFG; Lu et al., 2007). In teenagers aged between 12 and 17 years, gray matter of the left supramarginal gyrus and left posterior temporal regions correlate with vocabulary knowledge (Richardson et al., 2010). However, no study to date closely examined gray matter maturation in relation to the processing of syntactically complex sentences. Frontal and parietal areas have been shown to be involved in complex sentence processing (for a review, see Friederici, 2011). With regard to brain structure, the frontal and parietal lobe demonstrate an increase of gray matter during childhood (Giedd et al., 1999; Lenroot et al., 2007, Matsuzawa et al., 2001, Shaw et al., 2008) and an onset of gray matter loss around 9.6 years (frontal) and 10.7 years (temporal) of age (Tanaka et al., 2012).

Sentence comprehension crucially depends on determining the thematic relationship of noun phrases, that is, on identifying who is doing what to whom. While in English, word order provides a reliable cue for assigning thematic roles to noun phrases (i.e., agent, theme and goal), in German, the assignment additionally depends on processing morphological information such as case-marking. Behaviorally, it has been reported that German-speaking children cannot reliably process this kind of morphological information up to the age of 7 years (Dittmar et al., 2008, Schipke et al., 2012). In addition, several studies found that before 7 years of age, children do not demonstrate reliable subvocal rehearsal that increase verbal working memory capacity and, consequently, facilitate complex sentence processing (e.g., Gathercole et al., 2004, Gathercole and Hitch, 1993).

To elucidate on the missing link between brain structural properties of cortical regions relevant for complex sentence processing and the establishment of grammatical proficiency, we investigated the interrelation between GMP in language-relevant brain areas and specific cognitive abilities underlying complex sentence comprehension. To do this, whole-brain magnetic resonance images from 59 children aged between 5 and 8 years were assessed and analyzed using voxel-based morphometry (VBM). We determined grammatical proficiency by scores attained from grammar-specific subtests of the German version of the Test for the Reception of Grammar (TROG-D; Fox, 2006): Here, only sentences that required specific morphological and syntactic knowledge were included in the analysis. To segregate different contributions of grammatical knowledge and verbal working memory capacity to the comprehension of complex sentences, a principal component analysis was run on the participants’ behavioral data. To investigate a relation between these two factors and GMP on whole-brain level, a multiple regression analysis was performed. Finally, since the maturation of the prefrontal cortex has been associated with the development of linguistic conventions (Thompson-Schill et al., 2009) and the processing of syntactically complex sentences typically engages the left IFG (for a review, see Friederici, 2011), additional correlational analyses were restricted to this specific region.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

Children were recruited through letter announcements in local kindergartens and schools. Interested parents were invited for an informative meeting about the experiment and procedures. They gave informed written consent and children gave verbal assent prior to assessment and scanning. Children's parents filled out a questionnaire to ensure all participants were monolingual German speakers, had no neurological, medical, or psychological disorders, and no contraindications for obtaining a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) examination.

Ten children had to be excluded from the study because of too much head movement during the anatomical scan (N = 8) or brain anomalies (N = 2). Eventually, data from 28 children aged between 5 and 6 years (mean age: 5;11 years; range: 5;1 to 6;8 years; 13 boys and 15 girls) and 21 children aged between 7 and 8 years (mean age: 7;11; range: 7;1 to 8;9; 11 boys and 10 girls) were analyzed. Our group of children had a normal range of sequential processing skills in the verbal and visual domain (mean = 105; standard deviation = 12.05) administered by the Kaufman Assessment Battery for children (K-ABC; Kaufman et al., 1994). The socioeconomic status (SES) of our group was determined by maternal education converted into the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED 11, UNESCO Institute for Statistics, 2012). As with many other developmental studies, the group was weighted towards a high SES with 30% of the parents having upper-secondary education or post-secondary non-tertiary education (ISCED 3 and 4), 21.3% of the parents having short-cycle tertiary education or a Bachelor's degree (ISCED 5 and 6), 43.8% of the parents having a Master's degree (ISCED 7), and 3.8% having a doctoral degree (ISCED 9; general distribution of educational attainment in Germany: 50% ISCED 3/4; 8.6% ISCED 5/6; 13.6% ISCED 7; 1.1% ISCED 8; Bildungsbericht 2014, n.d.). The Research Ethics Committee of the University of Leipzig (Leipzig, Germany) approved the procedure and protocol of the study.

2.2. Assessment of grammatical proficiency and verbal working memory

Children's language comprehension skills were determined by the TROG-D (Fox, 2006). This is a standardized sentence comprehension test for children aged between 3 and 11 years. The comprehension of increasingly complex sentence structures is assessed by 21 grammatical constructions comprising four test items resulting in a final set of 84 items. Sentences are presented auditorily, and the child is asked to point to one out of four pictures whereby incorrect pictures depict either deviating lexical or grammatical interpretations.

We employed the Mottier Test (Mottier, 1951) to assess the children's verbal working memory abilities. Children had to listen to pseudowords with an increasing number of syllables and repeat them immediately after the presentation. For constant presentation, test items were recorded by a trained female speaker and subsequently digitized (44.1 kHz/16 bit sampling rate, mono), normalized according to the root-mean-square amplitude of all files, and presented via headphones. To make the procedure more suitable for children, we presented stimuli in form of a repetition game. Participants were introduced to a parrot on the screen who told them to repeat the items exactly how he pronounced them. To prevent lexicalization of the pseudowords during repetition, children were told that they cannot know the words they would hear since the parrot speaks a foreign parrot language. Children's responses were recorded via a portable mini disk recorder (Sony, Ft. Myers, FL, USA). These tests and an abridged version of the test for handedness (Oldfield, 1971) were administered in close temporal proximity to the MRI scanning (mean = 4 days; range: 1–26 days).

2.3. MRI acquisition procedures

During the scanning session, participants were shown a movie of their choice. Before scanning, children participated in a mock MRI scanner session to get accustomed to the scanning procedure and the scanner noise. A small sensor was fixated on the children's forehead to register movement and send a signal to the computer to interrupt the movie whenever children started to move. Additionally, we gave children verbal feedback via the headphones.

Participants were scanned in a whole-body 3-T Magnetom Trio scanner (Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany) and a 12-channel head coil at the Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences in Leipzig, Germany. MRI data were acquired with a T1-weighted 3D magnetization-prepared rapid gradient echo (MP-RAGE) sequence with selective water excitation and linear phase encoding. The magnetization preparation consisted of a non-selective inversion pulse. The following imaging parameters were used: inversion time (TI) = 740 ms; repetition time of the total sequence cycle (TR) = 1480 ms; repetition time of the gradient-echo kernel (snapshot FLASH) = 10 ms; TE = 3.46 ms; alpha = 10°; bandwidth = 190 Hz/pixel; image matrix = 256 × 240; FOV = 256 mm × 240 mm; slab thickness = 192 mm; 128 partitions; 95% slice resolution; sagittal orientation; spatial resolution = 1 mm × 1 mm × 1.5 mm; 2 acquisitions. Oversampling was performed in the read direction (head-foot) to avoid aliasing. The MRI sequence lasted about 6 min.

3. Data analysis

3.1. Confirmatory factor analysis

The TROG-D language test contains a large variety of sentences. While some of the sentences are constructed to test the interpretation of a specific word form such as a preposition, others focus on morphological and syntactic aspects of sentence processing. The different sentences included in the test battery thereby demand a varying degree of verbal working memory capacities. Since syntactic-related, morphological-related, and verbal working memory-related aspects of sentence processing are known to involve differential brain areas (for a recent review, see Friederici, 2011), we created a more homogenous subset of sentences of the TROG-D. This subset only contained sentences which required specific knowledge about case marking and structural hierarchy building to allow for the correct interpretation of who is doing what to whom (for an overview of sentences, see Table 1), and which are known to engage the fronto-temporal language areas (Friederici and Kotz, 2003, Bornkessel et al., 2005, Tyler and Marslen-Wilson, 2008). To check for potential age effects, the percentage of correct answers for each sentence structure was calculated in each age group and Pearson's correlations between performance and age were computed.

Table 1.

Overview of sentences from the TROG-D.

| Sentence structure | Example | Word order |

|---|---|---|

| Passive construction | Das Mädchen wird vom Pferd gejagt. The girlNOM is chased by the horseACC. |

SPatVOAg |

| Subject-relative clauses | Der Junge, der das Pferd jagt, ist dick. The boyNOM, whoNOM the horseACC chases, is fat. Das Mädchen jagt den Hund, der groß ist. The girlNOM chases the dogACC, thatNOM is big |

S1S2AgOPatV2V1 S1AgV1OPatS2V2 |

| Sentences with three arguments | Die Frau malt dem Jungen das Mädchen. The womanNOM paints the boyDAT the girlACC |

SAgVO1RecO2Theme |

| Object-topicalized sentences | Den braunen Hund jagt das Pferd. The brownACC dog chases the horseNOM. |

OPatVSAg |

| Object-relative clauses | Der Junge, den der Hund jagt, ist groß. The boyNOM, whoACC the dogNOM chases, is big |

S1OPatS2AgV2V1 |

TROG-D = German version of the Test for the Reception of Grammar; S = subject; V = verb; O = object; NOM = nominative; ACC = accusative; DAT = dative; Ag = agent (actor); Pat = patient (undergoer of action); Rec = recipient.

Interpretation of the selected sentences constitutes a big challenge for children for two reasons: While children need to inhibit their preferential interpretation strategy of only following the word order for thematic role assignment, they must be able to store the entire sentence to allow for the processing of long-distance dependencies and potential reanalysis processes. To corroborate that successful interpretation relies on these two different cognitive abilities, namely the inhibition of interpretation preferences and verbal working memory abilities, a confirmatory factor analysis was computed applying a principle component analysis to extract the grammar-relevant and a verbal working memory-relevant factor. Before the analysis, behavioral scores for each sentence structure were z-transformed within age groups (5–6-years versus 7–8-years) to control for age effects. For rotation, we used the varimax criterion to prevent correlations between factors. To confirm that one of these factors represents working memory capacities, the individual factor scores were correlated with scores of the Mottier Test (Mottier, 1951).

3.2. VBM data processing

Before preprocessing, we visually inspected all T1-images for movement artifacts that resulted in the exclusion of eight participants. The MRI data was analyzed with SPM 8 (Wellcome Department of Imaging Neuroscience, University College London) running in MATLAB 7 (Math-Works, Natick, MA, USA). Images were segmented into gray matter, white matter, and cerebrospinal fluid based on intensity values and a tissue probability map representing brain structure of children between the ages of 5 and 8 years (Fonov et al., 2011). Non-brain tissue was removed and initial segmentations were registered into MNI space. The gray and white matter images were imported into diffeomorphic anatomical registration using exponentiated lie algebra (DARTEL; Ashburner, 2007) and a template was created using the default parameters. The resulting flow fields containing the deformation information were subsequently used to normalize gray and white matter onto an age-specific template (Fonov et al., 2011). To obtain a measure of regional volume, images were modulated, resampled to 1.5 mm × 1.5 mm × 1.5 mm voxel size, and smoothed using an isotropic Gaussian kernel of 8 mm at FWHM. A modulated analysis was applied to correct for potential spatial normalization errors. Following this procedure, the GMP represents gray matter volume rather than gray matter concentration/density.

3.3. Statistical analysis of the VBM data

The statistical analysis was also performed using the software package SPM 8 (Wellcome Department of Imaging Neuroscience, University College London). To control for different brain sizes, we calculated the total intracranial volume (TIV) by summing the unmodulated volumes of gray matter, white matter, and cerebrospinal fluid. For assessing the relationship between GMP and behavioral covariates, we entered the scores of the different factors extracted by the principle component analysis into a multiple regression analysis. Additionally, we included age in months into the model to allow for the segregation of potential age and performance effects. To account for different brain sizes, potential sex differences (Tanaka et al., 2012), and structural alterations due to handedness (Dos Santos Sequeira et al., 2006, Zetzsche et al., 2001), we added sex, TIV, and the lateralization quotient (Oldfield, 1971) as covariates of no interest into the analysis. The individual voxel p-value threshold was set to p < 0.001. An AFNI implemented Monte-Carlo simulation (NIMH Scientific and Statistical Computing Core, Bethesda, MD, USA) ensured that a cluster size of 174 voxels protects against whole-volume type I error at α = 0.05.

After an exploratory whole brain assessment, a small volume correction procedure was used to restrict the analysis to the left IFG, a brain region that has constantly been shown to be involved in complex sentence processing (for a review, see Friederici, 2011). To ensure that only the relevant anatomical structures were included, a mask was generated by the Wake Forest University Pickatlas (Maldjian et al., 2003) based on the Talairach Daemon database (Lancaster et al., 2000). To correct for multiple comparisons, only clusters yielding a peak-level of p < 0.05, family-wise error-corrected for the search volume, are reported.

4. Results

4.1. Sentence interpretation and working memory

Mean percentage of correct answers according to each sentence structure and age effects are summarized in Table 2. Significant correlations between performance and age could be found for sentences with three arguments (r = 0.33, p < 0.05).

Table 2.

Mean scores of subtests for each age group and age effects.

| Age group | Mean (%) | Standard deviation | Age effect | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Passive constructions | 5–6-year olds | 90.18 | 19.65 | r = 0.07 |

| 7–8-year olds | 91.67 | 12.08 | ||

| Subject-relative clauses | 5–6-year olds | 89.29 | 27.58 | r = 0.26 |

| 7–8-year olds | 97.62 | 7.52 | ||

| Sentences with three arguments | 5–6-year olds | 83.06 | 19.31 | r = 0.33* |

| 7–8-year olds | 94.05 | 13.47 | ||

| Object-topicalized sentences | 5–6-year olds | 68.75 | 30.14 | r = 0.16 |

| 7–8-year olds | 78.57 | 27.71 | ||

| Object-relative clauses | 5–6-year olds | 46.43 | 30.97 | r = 0.15 |

| 7–8-year olds | 50.00 | 25.00 | ||

p < 0.05.

The principle component analysis on the different sentence structures of the TROG-D language test confirms two different factors underlying performance values. The appropriateness of the factor analysis and the distinction between these two factors are validated by the Bartlett's Test of Sphericity (χ210 = 44.74, p < 0.001) and the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Measure (KMO = 0.68). While the first factor (Factor 1) accounts for 45.5% of the variance in the observed variables, the second factor (Factor 2) accounts for another 21% of variance.

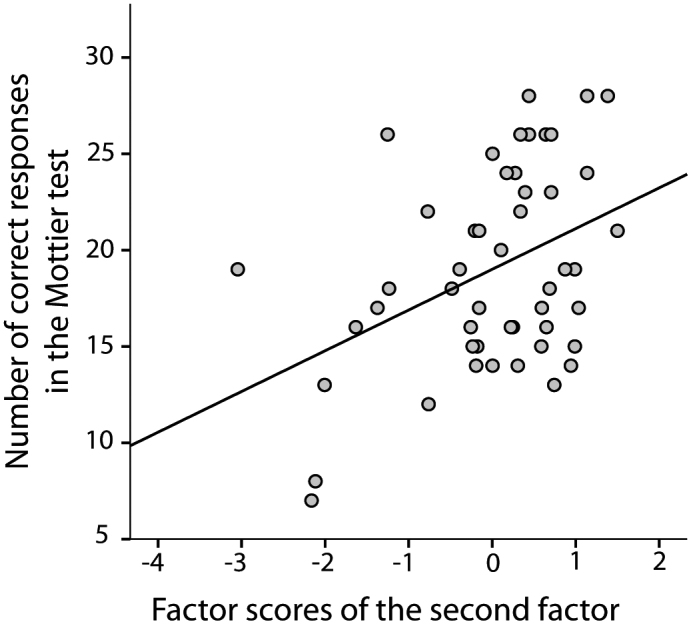

The following variables highly load on Factor 1: passive constructions, subject-relative clauses, and object-topicalized sentences. Sentences with three arguments highly load on Factor 2. Object-relative clauses load on both factors almost equally (an overview of factor loadings can be found in Table 3). To corroborate that one of these factors represents verbal working memory-related aspects of sentence processing, correlations between factor scores and the values of the Mottier Test were computed. A significant correlation could be found for Factor 2 (r = 0.41, p < 0.01; see Fig. 1), but not for Factor 1 (r = 0.27, p = 0.60), indicating that Factor 2 is related to verbal working memory.

Table 3.

Factor loadings after the principle component analysis.

| Factor 1 | Factor 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Passive constructions | 0.743 | 0.080 |

| Subject-relative clauses | 0.763 | −0.060 |

| Sentences with three arguments | −0.063 | 0.910 |

| Object-topicalized sentences | 0.806 | 0.252 |

| Object-relative clauses | 0.511 | 0.619 |

Bold font marks factor loading > 0.5.

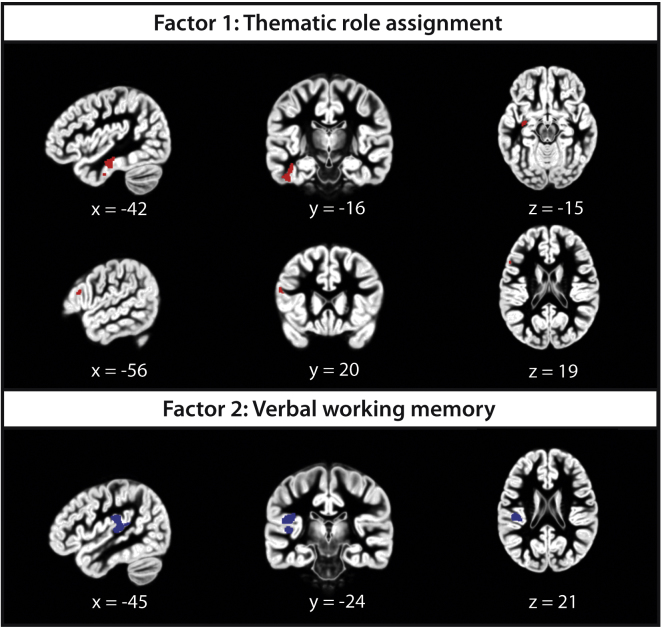

Fig. 1.

Correlation between factor scores for the second factor and scores of the Mottier Test (number of correct responses).

4.2. Results of the voxel-based morphometry analysis

In a next step, we examined whether individual scores of these different factors predict GMP. A multiple regression analysis considering the entire brain revealed a positive relationship between Factor 1 and GMP in the left inferior temporal gyrus including the left hippocampus (ITG; main peak at x = −42, y = −16, z = −23). When the search volume was restricted to the left IFG, a positive correlation between GMP and Factor 1 was also found (main peak at x = −56, y = 20, z = 19). A positive relationship between Factor 2 and GMP was evident in the left parietal operculum extending into the left posterior superior temporal gyrus (STG; main peak at x = −44, y = −24, z = 21). No negative correlations were observed. Significant clusters of these effects are depicted in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Results of the voxel-based morphometry analysis. Significant correlations are plotted on a template representing gray matter between the ages 4 and 8 years; positive correlations could be found between Factor 1 and GMP (upper panel) in the left inferior temporal gyrus and in left inferior frontal gyrus (in red); a positive correlation between the Factor 2 and GMP (lower panel) could be found in the left parietal operculum/superior temporal gyrus (in blue). (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of the article.)

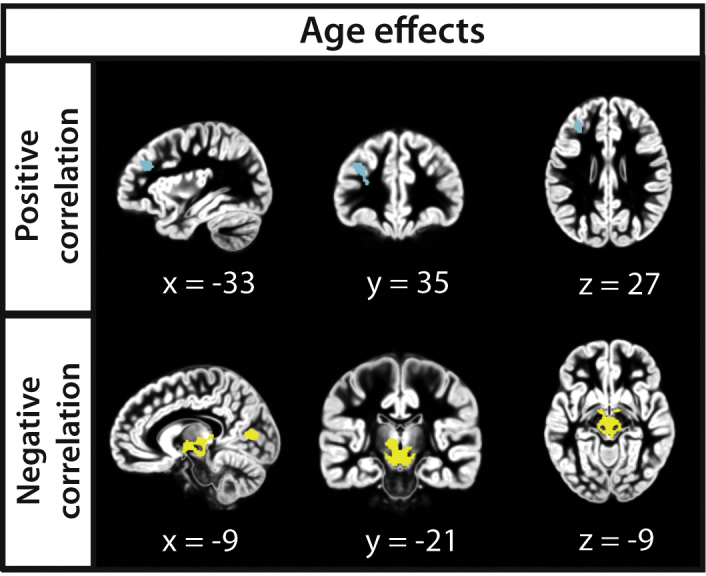

In contrast to the performance-related effects, a positive relation between age and GMP was evident in the left middle frontal gyrus (MFG; main peak at x = −33, y = 35, z = 27). A negative relation between age and GMP was observed for subcortical areas (main peak at x = −9, y = −21, z = −9) and in the left cuneus (main peak at x = −9, y = −78, z = 7; see Fig. 3). The full set of significant clusters can be found in Table 4.

Fig. 3.

Age effects of the voxel-based morphometry analysis. GMP correlates positively with age (upper panel) in the left middle frontal gyrus (in cyan); GMP correlates negatively with age (lower panel) in bilateral subcortical areas and in the left cuneus (in yellow). (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of the article.)

Table 4.

Overview of significant clusters.

| MNI coordinate |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hemisphere | Region | BA | X | Y | Z | Cluster size | z value | |||

| Positive correlation between age and GMP | ||||||||||

| Left | MFG | 5 | - | 33 | 35 | 27 | 292 | 3.83 | ||

| - | 28 | 36 | 15 | 3.67 | ||||||

| Negative correlation between age and GMP | ||||||||||

| Left | Substantia Nigra | - | 9 | - | 21 | - | 9 | 2546 | 5.14 | |

| Right | 9 | - | 22 | - | 11 | 5.06 | ||||

| Right | Thalamus | 10 | - | 7 | 1 | 3.92 | ||||

| Left | Cuneus | 23 | - | 9 | - | 78 | 7 | 815 | 4.38 | |

| Positive correlation between Factor 1 and GMP | ||||||||||

| Left | ITG | 20 | - | 42 | - | 16 | - | 23 | 491 | 3.99 |

| - | 48 | - | 16 | - | 38 | 3.94 | ||||

| Hippocampus | - | 33 | - | 10 | - | 15 | 3.56 | |||

| Left | IFG | 44/45 | - | 56 | 20 | 19 | 18 | 3.31* | ||

| Positive correlation between Factor 2 and GMP | ||||||||||

| Left | Parietal Operculum | 13 | - | 45 | - | 24 | 21 | 716 | 4.44 | |

| STG | 41 | - | 44 | - | 27 | 6 | 3.77 | |||

| Parietal Operculum | 13 | - | 39 | - | 19 | 25 | 3.63 | |||

174 voxels threshold at p < 0.001 to achieve family-wise error control at p < 0.05; * = small volume corrected; BA = Brodmann area; MNI = Montreal Neurological Institute; GMP = gray matter probability; MFG = middle frontal gyrus; ITG = inferior temporal gyrus; IFG = inferior frontal gyrus; STG = superior temporal gyrus.

5. Discussion

The results of the present study reveal a relationship between inter-individual variability in 5–8-year old children's brain morphology and specific cognitive abilities underlying complex sentence comprehension. More specifically, we found the brain's gray matter (GMP) in the left IFG, ITG, and in the left parietal operculum extending into the posterior STG to be positively correlated with different aspects of sentence comprehension.

5.1. Different aspects of sentence comprehension

A principle component analysis confirms two factors hypothesized to contribute to the variance in the sentence comprehension data. Passive constructions, subject-relative clauses, object-topicalized sentences, and object-relative clauses load on Factor 1. German speaking listeners typically prefer to assign the agent role to the first noun phrase and the patient role to the second noun phrase (for a detailed discussion about thematic role assignment in German, see Bornkessel and Schlesewsky, 2006, Fanselow, 2000, Primus, 1999, Wunderlich, 1997). However, in passive constructions, object-topicalized sentences, and object-relative clauses, the agent role is assigned to the second noun phrase (see Table 1). Therefore, listeners need to suppress the preferred word order -strategy and must exploit morphological case-marking that conveys the crucial information about the thematic relationship. Although subject-relative clauses follow the typical word order, the interpretation of these sentences requires thematic role assignment for two subjects. Again, without processing morphological information, the listener cannot identify who is doing what to whom. Considering this grammatical commonality of these four sentence structures, we propose that factor scores of Factor 1 reflect children's difficulties identifying and maintaining the morphological information necessary for correct thematic roles. This suggestion is supported by data showing that morphological information cannot be reliably processed up to 7 years of age (Dittmar et al., 2008, Schipke et al., 2012) and that, consequently, children rely on a word order instead of a structural interpretation (Lindner, 2003).

Factor 2 contains loadings of sentences with three arguments and additional loadings of object-relative sentences. A correlation between factor scores for this component and scores of the Mottier Test (Mottier, 1951) confirms that Factor 2 most likely represents verbal working memory-related aspects of sentence processing, which are especially represented by performance in these two types of sentences. Likewise, the processing of case marking is mandatory for sentences loading on Factor 2. However, in these sentences, insufficient verbal working memory capacity may prevent the processing of case-marking information, since not all arguments can be held active in working memory long enough, and thus thematic roles may have to be assigned before conflicting information is evaluated (for a detailed discussion, see Gibson, 2000). While in the sentences with three arguments the amount of arguments may exceed storage capacities in general, object-relative clauses require the establishment of long-distance dependencies. To process these dependencies, the listener has to store the first noun phrase until the end of the sentence while processing a non-canonical relative clause. Thus, the comprehension of these sentences fails when storage capacities are limited in time and/or influenced by intervening sentence material (cf. Gibson, 2000, Gordon et al., 2006, Lewis et al., 2006, Van Dyke and McElree, 2006). Considering the high working memory load of these two sentence structures and the correlation with the Mottier Test (Mottier, 1951), we suggest factor scores of Factor 2 to represent sentence processing differences due to differences in verbal working memory capacities.

5.2. Brain regions involved in sentence comprehension

Functional imaging studies indicate that the processing of increased sentence complexity induces increased activity in the left IFG (for a review, see Friederici, 2011). The left IFG can be subdivided into cytoarchitectonically distinct areas: the pars opercularis, the pars triangularis, and pars orbitalis (Amunts et al., 1999, Brodmann, 1909). While the left pars opercularis has been suggested to be involved in structural hierarchy building, a combined activation of the left pars opercularis and the left pars triangularis has been assumed to support thematic role assignment (for a review, see Grodzinsky and Friederici, 2006, Bornkessel and Schlesewsky, 2006). This assumption is supported not only by German studies investigating activation patterns induced by non-canonical sentence structures (Bornkessel et al., 2005, Fiebach et al., 2005, Friederici et al., 2006, Grewe et al., 2005, Röder et al., 2002), but also by studies of other languages that involved moved argument structures which engaged the pars triangularis/pars opercularis (Ben-Shachar et al., 2004, Ben-Shachar et al., 2003, Caplan et al., 2008, Constable et al., 2004, Cooke et al., 2002, Just et al., 1996, Kinno et al., 2008, Newman et al., 2010, Santi and Grodzinsky, 2010, Santi and Grodzinsky, 2007, Stromswold et al., 1996).

The left pars triangularis and the left MTG are connected via a ventral pathway through the extreme capsule fiber system (Frey et al., 2008, Saur et al., 2008), and it has been suggested that the interaction between prefrontal and temporal areas is essential for the integration of contextual information (Dapretto and Bookheimer, 1999, Kaan and Swaab, 2002). The MTG and neighboring parts of the ITG are proposed to be part of a brain network that stores lexical-semantic information (Crinion et al., 2003, Hickok and Poeppel, 2007, Hickok and Poeppel, 2004, Leff et al., 2008), since these regions become active while processing semantic sentence ambiguity (Rodd et al., 2005) and during semantic working memory tasks (Fiebach et al., 2007). Taking these functional findings together, the left IFG is proposed to be involved in the processing of non-canonical sentence structures, which requires the consideration of contextual information provided by the ITG for thematic role assignment. Therefore, we suggest that the increased GMP in these areas either provides a better neurophysiological basis for the acquisition of those mechanisms guiding the processing of non-canonical sentences, or it results from increased exposure to these types of sentences.

5.3. Functional factors and gray matter probability

The correlation between the functional factors and GMP in the brain regions discussed—to support sentence comprehension—is straightforward. Factor 1 reflecting children's difficulties in identifying and using morphological information for thematic role assignment is correlated with GMP in the left IFG and the left ITG, that is, in brain areas known to support syntactic and thematic processes (Grodzinsky and Friederici, 2006, Bornkessel and Schlesewsky, 2006). In contrast, Factor 2 is assumed to reflect performance variance introduced by different verbal working memory capacities. Scores of this factor positively correlate with GMP in the left parietal operculum extending into the left posterior STG. This result is consistent with patient data showing that the structural disintegration of the posterior STG after a stroke predicts both decreases in auditory short-term memory capacity and the ability to comprehend spoken sentences (Leff et al., 2009). In addition, this finding fits functional data showing that inferior parietal regions and the posterior STG show increased activation while processing sentences with increased verbal working memory load (Meyer et al., 2012, Novais-Santos et al., 2007), which suggests that this area serves as a phonological buffer storing verbal material. Therefore, high GMP in this area may reflect higher storage capacities.

Developmental changes of gray matter were evident in the left MFG, subcortical areas, and in the left cuneus. In contrast, correlations between behavioral performance and GMP appear independent of age. These findings suggest that increased GMP associated with increased performance cannot be explained by age-related changes, but appear to be subject-specific for our age group. More generally, the positive correlation between GMP and behavioral performance is in line with previous studies showing gray matter thickening in the left IFG and bilateral posterior perisylvian regions in children aged between 5 and 11 years (Sowell et al., 2004), as well as a positive correlation between the intelligence quotient and cortical volume, especially in prefrontal areas of children aged between 5 and 17 years (Reiss et al., 1996). The exact underlying neurophysiological mechanisms resulting in the observed GMP are yet unclear. It is known, however, that early gray matter maturation is marked by progressive changes such as an overgrowth of cell bodies (Petanjek et al., 2008), dendritic sprouting (Simonds and Scheibel, 1989), and an overgrowth of synaptic connections (Huttenlocher and de Courten, 1987, Rakic et al., 1986). Regressive changes such as synaptic pruning start to prevail, for example in the prefrontal cortex, around 9 years of age (Rakic et al., 1986). Values of gray matter measurements represent a combination of the extent of the cortical surface, cortical thickness, and myelination in adjacent white matter (Hutton et al., 2009, Mechelli et al., 2005), and recent studies have shown that not all cortical dimension develop at the same rate (Raznahan et al., 2011, Wierenga et al., 2014). During early childhood, cortical volume expands due to both cortical thickening and an increase in surface size (Raznahan et al., 2011). However, while cortical thickness decreases from 7 years of age in most regions, cortical volume and cortical surface peaks later—between 8 and 13 years of age (Wierenga et al., 2014). As mentioned in the introduction, progressive changes are assumed to provide the basis for maximal learning opportunities, especially in language-related areas (Johnson, 2011, Simonds and Scheibel, 1989). This assumption fits structural data showing a linear increase of the absolute gray matter volume in the lateral prefrontal areas between 5 and 18 years, whereas gray matter density (i.e., the proportion of gray matter relative to other tissues of this region) does not significantly change within this age range in this region (Taki et al., 2013). Since changes in gray matter volume are associated with synaptic formation and elimination (Huttenlocher, 1979, Paus, 2005), increased GMP observed in our study, especially in the left IFG, may mirror increased local synaptic connectivity which may be due to a greater maturity of these regions leading to a superior cortical basis for language learning and better performance. Alternatively, it has been shown that trajectories of cortical maturation are associated with intelligence whereby individuals that are more intelligent show a prolonged phase of cortical increase (Shaw et al., 2006). Following this finding, increased GMP can also reflect a latter onset of gray matter reduction and thus a higher plasticity in these areas, which results in an extended sensitive period for learning. Due to missing longitudinal and training studies, it remains unclear whether and to what extend cortical properties in children can be altered by exposure to specific sentence constructions. Animal studies, for example, have shown that environmental enrichment is associated with increased amount of synapses (Diamond et al., 1966, Diamond et al., 1964). Therefore, it cannot be excluded that increased GMP associated with increased performance results from increased exposure.

6. Conclusion

This study utilized structural MRI to elucidate the relation between cortical properties and the development of cognitive milestones. More specifically, this study demonstrates the relationship between gray matter in different brain substrates and differential cognitive abilities underlying complex sentence processing in 5–8-year-old children. We show that the ability to assign thematic roles against a preferential interpretation strategy and verbal working memory-related performance for complex sentence comprehension are differentially associated with GMP in brain areas known to be involved in complex sentence processing in adults. However, it remains an open question whether the increased GMP in these children reflects differential cortical prerequisites of these brain regions or differential trajectories of cortical development. Further research using longitudinal methods should address this issue.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from the European Research Council (ERC-2010-360 AdG 20100407 awarded to A.D.F.).

Acknowledgments

We thank all the participating children and parents, H.-A. Jeon, I. Henseler, R. Roggenhofer, M. Jochemko, A. Wiedemann, S. Wipper, A. Gast-Sandmann, and S. Wagner. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Amunts K., Schleicher A., Bürgel U., Mohlberg H., Uylings H.B., Zilles K. Broca's region revisited: cytoarchitecture and intersubject variability. J. Comp. Neurol. 1999;412:319–341. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19990920)412:2<319::aid-cne10>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashburner J. A fast diffeomorphic image registration algorithm. NeuroImage. 2007;38:95–113. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Shachar M., Hendler T., Kahn I., Ben-Bashat D., Grodzinsky Y. The neural reality of syntactic transformations: evidence from functional magnetic resonance imaging. Psychol. Sci. 2003;14:433–440. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.01459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Shachar M., Palti D., Grodzinsky Y. Neural correlates of syntactic movement: converging evidence from two fMRI experiments. NeuroImage. 2004;21:1320–1336. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2003.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bildungsbericht 2014, n.d. Retrieved from http://www.bildungsbericht.de (15.05.15).

- Bornkessel I., Zysset S., Friederici A.D., von Cramon D.Y., Schlesewsky M. Who did what to whom? The neural basis of argument hierarchies during language comprehension. NeuroImage. 2005;26:221–233. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornkessel I., Schlesewsky M. The extended argument dependency model: a neurocognitive approach to sentence comprehension across languages. Psychol. Rev. 2006;113:787–821. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.113.4.787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brain Development Cooperative Group Total and regional brain volumes in a population-based normative sample from 4 to 18 years: the NIH MRI study of normal brain development. Cereb. Cortex. 2012;22:1–12. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhr018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodmann K. Barth; Leipzig: 1909. Vergleichende Lokalisationslehre der Grosshirnrinde in ihren Prinzipien dargestellt auf Grund des Zellenbaues. [Google Scholar]

- Caplan D., Chen E., Waters G. Task-dependent and task-independent neurovascular responses to syntactic processing. Cortex J. Devoted Study Nerv. Syst. Behav. 2008;44:257–275. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2006.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constable R.T., Pugh K.R., Berroya E., Mencl W.E., Westerveld M., Ni W., Shankweiler D. Sentence complexity and input modality effects in sentence comprehension: an fMRI study. NeuroImage. 2004;22:11–21. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke A., Zurif E.B., DeVita C., Alsop D., Koenig P., Detre J., Gee J., Pinãngo M., Balogh J., Grossman M. Neural basis for sentence comprehension: grammatical and short-term memory components. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2002;15:80–94. doi: 10.1002/hbm.10006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courchesne E., Chisum H.J., Townsend J., Cowles A., Covington J., Egaas B., Harwood M., Hinds S., Press G.A. Normal brain development and aging: quantitative analysis at in vivo MR imaging in healthy volunteers. Radiology. 2000;216:672–682. doi: 10.1148/radiology.216.3.r00au37672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crinion J.T., Lambon-Ralph M.A., Warburton E.A., Howard D., Wise R.J.S. Temporal lobe regions engaged during normal speech comprehension. Brain. 2003;126:1193–1201. doi: 10.1093/brain/awg104. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/brain/awg104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond M.C., Krech D., Rosenzweig M.R. The effects of an enriched environment on the histology of the rat cerebral cortex. J. Comp. Neurol. 1964;123:111–119. doi: 10.1002/cne.901230110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond M.C., Law F., Rhodes H., Lindner B., Rosenzweig M.R., Krech D., Bennett E.L. Increases in cortical depth and glia numbers in rats subjected to enriched environment. J. Comp. Neurol. 1966;128:117–125. doi: 10.1002/cne.901280110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dapretto M., Bookheimer S.Y. Form and content: dissociating syntax and semantics in sentence comprehension. Neuron. 1999;24:427–432. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80855-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diessel H., Tomasello M. A new look at the acquisition of relative clauses. Language. 2005;81:882–906. doi: 10.1017/S0305000907008379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deniz Can D., Richards T., Kuhl P.K. Early gray-matter and white-matter concentration in infancy predict later language skills: a whole brain voxel-based morphometry study. Brain Lang. 2013;124:34–44. doi: 10.1016/j.bandl.2012.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dittmar M., Abbot-Smith K., Lieven E., Tomasello M. German children's comprehension of word order and case marking in causative sentences. Child Dev. 2008;79:1152–1167. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01181.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dos Santos Sequeira S., Woerner W., Walter C., Kreuder F., Lueken U., Westerhausen R., Wittling R.A., Schweiger E., Wittling W. Handedness, dichotic-listening ear advantage, and gender effects on planum temporale asymmetry – a volumetric investigation using structural magnetic resonance imaging. Neuropsychologia. 2006;44:622–636. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2005.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fanselow G. Optimal exceptions. In: Stiebels B., Wunderlich D., editors. Lexicon in Focus. Akademie Verlag; Berlin: 2000. pp. 173–209. [Google Scholar]

- Fiebach C.J., Friederici A.D., Smith E.E., Swinney D. Lateral inferotemporal cortex maintains conceptual-semantic representations in verbal working memory. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 2007;19:2035–2049. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2007.19.12.2035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiebach C.J., Schlesewsky M., Lohmann G., von Cramon D.Y., Friederici A.D. Revisiting the role of Broca's area in sentence processing: syntactic integration versus syntactic working memory. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2005;24:79–91. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonov V., Evans A.C., Botteron K., Almli C.R., McKinstry R.C., Collins D.L. Unbiased average age-appropriate atlases for pediatric studies. NeuroImage. 2011;54:313–327. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.07.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox A.V. Schulz-Kirchner Verlag; Idstein: 2006. TROG-D. Test zur Überprüfung des Grammatikverständnisses. Handbuch. Das Gesundheitsforum. [Google Scholar]

- Frey S., Campbell J.S.W., Pike G.B., Petrides M. Dissociating the human language pathways with high angular resolution diffusion fiber tractography. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:11435–11444. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2388-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friederici A.D. The brain basis of language processing: from structure to function. Physiol. Rev. 2011;91:1357–1392. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00006.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friederici A.D., Fiebach C.J., Schlesewsky M., Bornkessel I.D., von Cramon D.Y. Processing linguistic complexity and grammaticality in the left frontal cortex. Cereb. Cortex. 2006;16:1709–1717. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhj106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friederici A.D., Kotz S.A. The brain basis of syntactic processes: functional imaging and lesion studies. NeuroImage. 2003;20:S8–S17. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2003.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gathercole S.E., Hitch G.J. Developmental changes in short-term memory: a revised working memory perspective. In: Collins A.F., Gathercole S.E., Conway M.A., Morris P.E., editors. Theories of Memory. L. Erlbaum Associates; Hove: 1993. pp. 189–209. [Google Scholar]

- Gathercole S.E., Pickering S.J., Ambridge B., Wearing H. The structure of working memory from 4 to 15 years of age. Dev. Psychol. 2004;40:177–190. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.40.2.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson E. The dependency locality theory: a distance-based theory of linguistic complexity. In: Miyashita Y., Marantz A., O’Neil W., editors. Image, Language, Brain. MIT Press; Cambridge: 2000. pp. 95–126. [Google Scholar]

- Giedd J.N., Blumenthal J., Jeffries N.O., Castellanos F.X., Liu H., Zijdenbos A., Paus T., Evans A.C., Rapoport J.L. Brain development during childhood and adolescence: a longitudinal MRI study. Nat. Neurosci. 1999;2:861–863. doi: 10.1038/13158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giedd J.N., Rapoport J.L. Structural MRI of pediatric brain development: what have we learned and where are we going? Neuron. 2010;67:728–734. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.08.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gogtay N., Giedd J.N., Lusk L., Hayashi K.M., Greenstein D., Vaituzis A.C., Nugent T.F., Herman D.H., Clasen L.S., Toga A.W., Rapoport J.L., Thompson P.M. Dynamic mapping of human cortical development during childhood through early adulthood. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2004;101:8174–8179. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402680101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gogtay N., Thompson P.M. Mapping gray matter development: implications for typical development and vulnerability to psychopathology. Brain Cogn. 2010;72:6–15. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2009.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodluck H., Tavakolian S. Competence and processing in children's grammar of relative clauses. Cognition. 1982;11:1–27. doi: 10.1016/0010-0277(82)90002-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon P.C., Hendrick R., Johnson M., Lee Y. Similarity-based interference during language comprehension: evidence from eye tracking during reading. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn. 2006;32:1304–1321. doi: 10.1037/0278-7393.32.6.1304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grewe T., Bornkessel I., Zysset S., Wiese R., von Cramon D.Y., Schlesewsky M. The emergence of the unmarked: a new perspective on the language-specific function of Broca's area. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2005;26:178–190. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grodzinsky Y., Friederici A.D. Neuroimaging of syntax and syntactic processing. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2006;16:240–246. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2006.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickok G., Poeppel D. Dorsal and ventral streams: a framework for understanding aspects of the functional anatomy of language. Cognition. 2004;92:67–99. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2003.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickok G., Poeppel D. The cortical organization of speech processing. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2007;8:393–402. doi: 10.1038/nrn2113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huttenlocher P.R. Synaptic density in human frontal cortex – developmental changes and effects of aging. Brain Res. 1979;163:195–205. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(79)90349-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huttenlocher P.R. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 2002. Neural Plasticity: The Effects of Environment on the Development of the Cerebral Cortex. [Google Scholar]

- Huttenlocher P.R., de Courten C. The development of synapses in striate cortex of man. Hum. Neurobiol. 1987;6:1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutton C., Draganski B., Ashburner J., Weiskopf N. A comparison between voxel-based cortical thickness and voxel-based morphometry in normal aging. NeuroImage. 2009;48:371–380. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.06.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson M.H. Functional brain development in humans. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2001;2:475–483. doi: 10.1038/35081509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson M.H. Interactive specialization: a domain-general framework for human functional brain development? Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 2011;1:7–21. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2010.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Just M.A., Carpenter P.A., Keller T.A., Eddy W.F., Thulborn K.R. Brain activation modulated by sentence comprehension. Science. 1996;274:114–116. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5284.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaan E., Swaab T.Y. The brain circuitry of syntactic comprehension. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2002;6:350–356. doi: 10.1016/s1364-6613(02)01947-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman A.S., Kaufman N.L., Melchers P., Preuss U. 2nd ed. Swets & Zeitlinger; Amsterdam: 1994. K-ABC: Kaufman Assessment Battery for Children. [Google Scholar]

- Kinno R., Kawamura M., Shioda S., Sakai K.L. Neural correlates of noncanonical syntactic processing revealed by a picture-sentence matching task. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2008;29:1015–1027. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lancaster J.L., Woldorff M.G., Parsons L.M., Liotti M., Freitas C.S., Rainey L., Kochunov P.V., Nickerson D., Mikiten S.A., Fox P.T. Automated Talairach atlas labels for functional brain mapping. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2000;10:120–131. doi: 10.1002/1097-0193(200007)10:3<120::AID-HBM30>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leff A.P., Schofield T.M., Crinion J.T., Seghier M.L., Grogan A., Green D.W., Price C.J. The left superior temporal gyrus is a shared substrate for auditory short-term memory and speech comprehension: evidence from 210 patients with stroke. Brain J. Neurol. 2009;132:3401–3410. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leff A.P., Schofield T.M., Stephan K.E., Crinion J.T., Friston K.J., Price C.J. The cortical dynamics of intelligible speech. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:13209–13215. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2903-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenroot R.K., Giedd J.N. Brain development in children and adolescents: insights from anatomical magnetic resonance imaging. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2006;30:718–729. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2006.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenroot R.K., Gogtay N., Greenstein D.K., Wells E.M., Wallace G.L., Clasen L.S., Blumenthal J.D., Lerch J., Zijdenbos A.P., Evans A.C. Sexual dimorphism of brain developmental trajectories during childhood and adolescence. NeuroImage. 2007;36:1065–1073. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.03.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis R.L., Vasishth S., Van Dyke J.A. Computational principles of working memory in sentence comprehension. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2006;10:447–454. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2006.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindner K. The development of sentence-interpretation strategies in monolingual German-learning children with and without specific language impairment. Linguistics. 2003;41:213–254. http://dx.doi.org/10.1515/ling.2003.008. [Google Scholar]

- Lu L., Leonard C., Thompson P., Kan E., Jolley J., Welcome S., Toga A., Sowell E. Normal developmental changes in inferior frontal gray matter are associated with improvement in phonological processing: a longitudinal MRI analysis. Cereb. Cortex. 2007;17:1092–1099. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhl019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maldjian J.A., Laurienti P.J., Kraft R.A., Burdette J.H. An automated method for neuroanatomic and cytoarchitectonic atlas-based interrogation of fMRI data sets. NeuroImage. 2003;19:1233–1239. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(03)00169-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuzawa J., Matsui M., Konishi T., Noguchi K., Gur R.C., Bilker W., Miyawaki T. Age-related volumetric changes of brain gray and white matter in healthy infants and children. Cereb. Cortex. 2001;11:335–342. doi: 10.1093/cercor/11.4.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mechelli A., Price C., Friston K., Ashburner J. Voxel-based morphometry of the human brain: methods and applications. Curr. Med. Imaging Rev. 2005;1:105–113. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer L., Obleser J., Anwander A., Friederici A.D. Linking ordering in Broca's area to storage in left temporo-parietal regions: the case of sentence processing. NeuroImage. 2012;62:1987–1998. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.05.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mottier G. Mottier-Test, Über Untersuchungen zur Sprache lesegestörter Kinder. Folia Phoniatr. Logop. 1951;3:170–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman S.D., Ikuta T., Burns T. The effect of semantic relatedness on syntactic analysis: an fMRI study. Brain Lang. 2010;113:51–58. doi: 10.1016/j.bandl.2010.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novais-Santos S., Gee J., Shah M., Troiani V., Work M., Grossman M. Resolving sentence ambiguity with planning and working memory resources: evidence from fMRI. NeuroImage. 2007;37:361–378. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.03.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldfield R.C. The assessment and analysis of handedness: the Edinburgh inventory. Neuropsychologia. 1971;9:97–113. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(71)90067-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paus T. Mapping brain maturation and cognitive development during adolescence. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2005;9:60–68. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2004.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petanjek Z., Judas M., Kostović I., Uylings H.B.M. Lifespan alterations of basal dendritic trees of pyramidal neurons in the human prefrontal cortex: a layer-specific pattern. Cereb. Cortex. 2008;18:915–929. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhm124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Primus B. Niemeyer; Tübingen: 1999. Cases and Thematic Roles: Ergative, Accusative and Active. [Google Scholar]

- Rakic P., Bourgeois J.P., Eckenhoff M.F., Zecevic N., Goldman-Rakic P.S. Concurrent overproduction of synapses in diverse regions of the primate cerebral cortex. Science. 1986;232:232–235. doi: 10.1126/science.3952506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raznahan A., Shaw P., Lalonde F., Stockman M., Wallace G.L., Greenstein D., Clasen L., Gogtay N., Giedd J.N. How does your cortex grow? J. Neurosci. 2011;31:7174–7177. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0054-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiss A.L., Abrams M.T., Singer H.S., Ross J.L., Denckla M.B. Brain development, gender and IQ in children. A volumetric imaging study. Brain J. Neurol. 1996;119(5):1763–1774. doi: 10.1093/brain/119.5.1763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson F.M., Thomas M.S.C., Filippi R., Harth H., Price C.J. Contrasting effects of vocabulary knowledge on temporal and parietal brain structure across lifespan. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 2010;22:943–954. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2009.21238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodd J.M., Davis M.H., Johnsrude I.S. The neural mechanisms of speech comprehension: fMRI studies of semantic ambiguity. Cereb. Cortex. 2005;15:1261–1269. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhi009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Röder B., Stock O., Neville H., Bien S., Rösler F. Brain activation modulated by the comprehension of normal and pseudo-word sentences of different processing demands: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study. NeuroImage. 2002;15:1003–1014. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santi A., Grodzinsky Y. Working memory and syntax interact in Broca's area. NeuroImage. 2007;37:8–17. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.04.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santi A., Grodzinsky Y. fMRI adaptation dissociates syntactic complexity dimensions. NeuroImage. 2010;51:1285–1293. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.03.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saur D., Kreher B.W., Schnell S., Kümmerer D., Kellmeyer P., Vry M.-S., Umarova R., Musso M., Glauche V., Abel S., Huber W., Rijntjes M., Hennig J., Weiller C. Ventral and dorsal pathways for language. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2008;105:18035–18040. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805234105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheldon A. The role of parallel function in the acquisition of relative clauses in English. J. Verbal Learn. Verbal Behav. 1974;13:272–281. [Google Scholar]

- Schipke C.S., Knoll L.J., Friederici A.D., Oberecker R. Preschool children's interpretation of object-initial sentences: neural correlates of their behavioral performance. Dev. Sci. 2012;15:762–774. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2012.01167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw P., Greenstein D., Lerch J., Clasen L., Lenroot R., Gogtay N., Evans A., Rapoport J., Giedd J. Intellectual ability and cortical development in children and adolescents. Nature. 2006;440:676–679. doi: 10.1038/nature04513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw P., Kabani N.J., Lerch J.P., Eckstrand K., Lenroot R., Gogtay N., Greenstein D., Clasen L., Evans A., Rapoport J.L., Giedd J.N., Wise S.P. Neurodevelopmental trajectories of the human cerebral cortex. J. Neurosci. Off. J. Soc. Neurosci. 2008;28:3586–3594. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5309-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonds R.J., Scheibel A.B. The postnatal development of the motor speech area: a preliminary study. Brain Lang. 1989;37:42–58. doi: 10.1016/0093-934x(89)90100-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sowell E.R., Peterson B.S., Thompson P.M., Welcome S.E., Henkenius A.L., Toga A.W. Mapping cortical change across the human life span. Nat. Neurosci. 2003;6:309–315. doi: 10.1038/nn1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sowell E.R., Thompson P.M., Leonard C.M., Welcome S.E., Kan E., Toga A.W. Longitudinal mapping of cortical thickness and brain growth in normal children. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:8223–8231. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1798-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stromswold K., Caplan D., Alpert N., Rauch S. Localization of syntactic comprehension by positron emission tomography. Brain Lang. 1996;52:452–473. doi: 10.1006/brln.1996.0024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taki Y., Hashizume H., Thyreau B., Sassa Y., Takeuchi H., Wu K., Kotozaki Y., Nouchi R., Asano M., Asano K., Fukuda H., Kawashima R. Linear and curvilinear correlations of brain gray matter volume and density with age using voxel-based morphometry with the Akaike information criterion in 291 healthy children. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2013;34:1857–1871. doi: 10.1002/hbm.22033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka C., Matsui M., Uematsu A., Noguchi K., Miyawaki T. Developmental trajectories of the fronto-temporal lobes from infancy to early adulthood in healthy individuals. Dev. Neurosci. 2012;34:477–487. doi: 10.1159/000345152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavakolian S.L. The conjoined-clause analysis of relative clauses. In: Tavakolian S.L., editor. Language Acquisition and Linguistic Theory. MIT Press; Cambridge: 1981. pp. 167–187. [Google Scholar]

- Tyler L.K., Marslen-Wilson W. Fronto-temporal brain systems supporting spoken language comprehension. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 2008;363:1037–1054. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2007.2158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson-Schill S.L., Ramscar M., Chrysikou E.G. When a little frontal lobe goes a long way. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2009;18:259–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2009.01648.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO Institute for Statistics . UNESCO Institute for Statistics; Montreal, Quebec: 2012. International Standard Classification of Education: ISCED 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dyke J.A., McElree B. Retrieval interference in sentence comprehension. J. Mem. Lang. 2006;55:157–166. doi: 10.1016/j.jml.2006.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wierenga L.M., Langen M., Oranje B., Durston S. Unique developmental trajectories of cortical thickness and surface area. NeuroImage. 2014;87:120–126. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wunderlich D. Cause and the structure of verbs. Linguist. Inq. 1997;28:27–68. [Google Scholar]

- Yakovlev P.I., Lecours A.R. The myelogenetic cycles of regional maturation of the brain. In: Minkowski A., editor. Regional Development of the Brain in Early Life. Blackwell Scientific Publications; Oxford: 1967. pp. 3–65. [Google Scholar]

- Zetzsche T., Meisenzahl E.M., Preuss U.W., Holder J.J., Kathmann N., Leinsinger G., Hahn K., Hegerl U., Möller H.J. In-vivo analysis of the human planum temporale (PT): does the definition of PT borders influence the results with regard to cerebral asymmetry and correlation with handedness? Psychiatry Res. 2001;107:99–115. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4927(01)00087-7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0925-4927(01)00087-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]