Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the attitude of pregnant women towards HIV testing in two cities of West Africa: Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire and Bobo-Dioulasso, Burkina Faso.

Methods

In the context of a clinical trial to prevent HIV vertical transmission, HIV counselling and testing was offered systematically to women attending antenatal clinics. Informed consent was obtained and test results were given anonymously. Multiple logistic regression was performed to identify factors associated with refusal for testing and failure to return for test results.

Results

A total of 9724 pregnant women were interviewed from January 1995 to September 1996. In Abidjan (n = 5766) and Bobo-Dioulasso (n = 3958), 78 and 92.4% of the women consented to HIV testing, respectively, and 58.4 and 81.8% of them returned for the test results disclosure, respectively. In the two sites, the counsellors themselves and high educational level of the women appeared to be related to refusal of the test, whereas last trimester gestation was associated with failure to return for test results. In Abidjan, foreigners and employees were more likely to refuse testing, and HIV-infected women were three times less likely to return for results than uninfected women.

Conclusion

Future implementation of interventions to reduce vertical transmission of HIV that require antenatal HIV testing and counselling will have to solve issue of acceptability of HIV testing by pregnant women.

Keywords: Burkina Faso; Cote d'Ivoire; Counseling; Female; HIV Infections; Health Knowledge, Attitudes, Practice; Humans; Pregnancy; Treatment Refusal

Introduction

Since the beginning of the epidemic, more than 16 million adults have been infected by HIV in Africa. More than half of them are women, and as many as one million of African children are estimated to have been infected as a result of mother-to-child transmission of HIV [1]. Côte d’Ivoire and Burkina Faso are among the most affected countries in West Africa. In Abidjan, the economic capital city of Côte d’Ivoire (3 million inhabitants), and in Bobo-Dioulasso, the second city of Burkina Faso (400 000 inhabitants), the 1995 prevalence of HIV infection among pregnant women was 14.2% [2] and 7.5% [3], respectively. Several interventions offer the potential to reduce vertical HIV transmission in developing countries. Some of these interventions, such as antenatal administration of antiretroviral drugs, imply organization of HIV counselling and testing among pregnant women. Observational studies conducted in East Africa have suggested that HIV-infected pregnant women are less likely to return to obtain test results than uninfected women [4,5]. This may have an impact on perinatal intervention strategies that require antenatal HIV screening.

In the context of a phase II clinical trial of a short course of zidovudine during pregnancy (ANRS 049) [6], HIV counselling and testing activities were implemented in antenatal clinics in Abidjan and Bobo-Dioulasso. We evaluated the attitudes of pregnant women towards HIV testing in these West African cities in 1995–1996.

Methods

Study sites and population

The study was part of the ANRS 049 trial, and was conducted from January 1995 to October 1996 at three antenatal public clinics located in the Yopougon district of Abidjan, and in Bobo-Dioulasso at the Social Security and the Farakan Health Clinics. Each woman attending these antenatal clinics, with a pregnancy of 7 months or less, living within 10 km of the health centre and aged 18 years or more, received HIV pretest counselling and was offered free HIV serological testing.

Study design and counselling program

Pretest counselling was performed in French or in the local language by specifically trained social workers recruited by the project. Knowledge about HIV infection was evaluated and further information was given if needed. Topics discussed included routes of HIV transmission, and means of prevention and care, but no specific details about the ANRS 049 trial were given at that stage. Reasons for refusing HIV testing were noted. Sociodemographic characteristics and obstetric history data were collected on a standardized questionnaire. Six months after the beginning of the study, we extended this initial questionnaire by collecting data about knowledge of HIV infection at pretest counselling. Women who accepted HIV testing had their blood collected for HIV serology after written informed consent was obtained. Within 2 or 3 weeks according to the site, post-test counselling and test results were given individually and confidentially. In Bobo-Dioulasso, social workers collected the address of the women, if they agreed to be contacted, in case they missed their post-test appointment.

Laboratory methods

Serum samples were tested at the CeDReS (Abidjan) and Centre Muraz (Bobo-Dioulasso) laboratories using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Genelavia Mixt, Sanofi Diagnostics Pasteur, Paris, France) and, if the first test was positive, by a synthetic peptide-based assay (PEPTILAV, Sanofi Diagnostics Pasteur). HIV-positive tests refer to HIV-1, HIV-2 or dually reactive sera.

Data analysis

Reasons for refusing HIV testing were coded, and characteristics of women who refused testing and those who did not return for post-test counselling after being tested were analysed separately. χ2 test, Fisher’s exact test and Student’s t-test were used for comparisons at a significance level of 5%. Odds ratios (OR) were computed to measure the strength of associations and their 95% confidence intervals (CI) were determined. Multiple logistic regression analysis was performed to identify factors associated with refusal for testing, and with failure to return for results. A cut-off P value of 0.25 was used in the univariate analysis as the criteria for including variables in the multivariate analysis. Each centre was studied separately and no attempt was made to pool the data because important differences had been observed between the two cities.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics of the pregnant women

Overall, 9724 pregnant women were offered HIV testing through pretest counselling (5766 in Abidjan and 3958 in Bobo-Dioulasso). Pregnant women from the two sites were mainly aged 18–29 years, with little education, were housewives and living with a partner (Table 1). They had on the average more than three pregnancies including the current one, more than two children alive and at least four persons to support not including their partner. Pregnant women from the two sites differed by religion (mainly Christian in Abidjan and Muslim in Bobo-Dioulasso), educational level (40% illiterate versus 65%; P < 10−8), educational level of the partner (35.9% illiterate versus 56.5%; P < 10−7) and proportions of foreigners (14 versus 5.6%; P < 10−7). HIV prevalence amongst the women tested was 14.8% (95% CI, 13.7–15.9) in Abidjan versus 9.2% (95% CI, 8.3–10.2) in Bobo-Dioulasso (P < 10−8). Women were seen by the project at antenatal clinics later in pregnancy in Abidjan than in Bobo-Dioulasso (mean weeks of gestation, 27 versus 24; P < 10−6).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of pregnant women attending antenatal clinics in Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire and Bobo-Dioulasso, Burkina Faso, 1995–1996.

| %

|

P | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Abidjan (n = 5766) | Bobo-Dioulasso (n = 3958) | ||

| Age (years) | |||

| 18–19 | 16.0 | 15.8 | < 10−7 |

| 20–24 | 35.8 | 30.7 | |

| 25–29 | 24.6 | 25.5 | |

| 30–34 | 16.0 | 16.2 | |

| ≥ 35 | 7.6 | 11.8 | |

| Parity | |||

| ≥ 2 | 73 | 57 | < 10−7 |

| Religion | |||

| Muslim | 30.6 | 81.2 | < 10−7 |

| Catholic | 23.0 | 15.6 | |

| Protestant | 14.9 | 2.6 | |

| Other | 31.5 | 0.6 | |

| Marital status | |||

| Single/divorced/widowed | 18.7 | 10.4 | < 10−7 |

| Living with partner | 81.3 | 89.6 | |

| Woman’s education | |||

| None | 40.0 | 65.3 | < 10−7 |

| Primary (1–7 years) | 33.7 | 21.3 | |

| Secondary and higher | 26.2 | 13.4 | |

| Woman’s occupation | |||

| Housewife | 52.9 | 53.4 | < 10−7 |

| Merchant | 37.5 | 40.4 | |

| Employee | 2.6 | 2.2 | |

| Other | 7.1 | 4.0 | |

| Foreigners | 13.9 | 5.6 | < 10−7 |

| HIV-infected | 14.8 | 9.2 | < 10−7 |

Knowledge about HIV/AIDS

Information concerning knowledge about HIV/AIDS was collected from consecutive samples of 5409 and 3015 women in Abidjan and Bobo-Dioulasso, respectively. The main mode of transmission of HIV in Africa (sexual) and the principal mean of protection (condoms) were well known. However, the vast majority of these pregnant women were not aware of vertical transmission and less than half of the women from the two sites knew that HIV infection could be asymptomatic (Table 2).

Table 2.

Knowledge about HIV infection of pregnant women attending antenatal clinics in Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire and Bobo-Dioulasso, Burkina Faso, 1995–1996.

| Answers quoted (%)

|

P | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Abidjan (n = 5409) | Bobo-Dioulasso (n = 3015) | ||

| Modes of transmission | |||

| Sexual | 88.0 | 86.7 | 0.08 |

| Parenteral | 34.6 | 62.2 | < 10−7 |

| Mother-to-child | 1.8 | 8.0 | < 10−7 |

| Means of prevention | |||

| Condoms | 78.9 | 72.0 | < 10−7 |

| Mutual faithfulness | 78.3 | 24.4 | < 10−7 |

| Abstinence | 33.0 | 8.0 | < 10−7 |

| HIV infection asymptomatic | 47.4 | 47.2 | 0.65 |

Results of counselling sessions

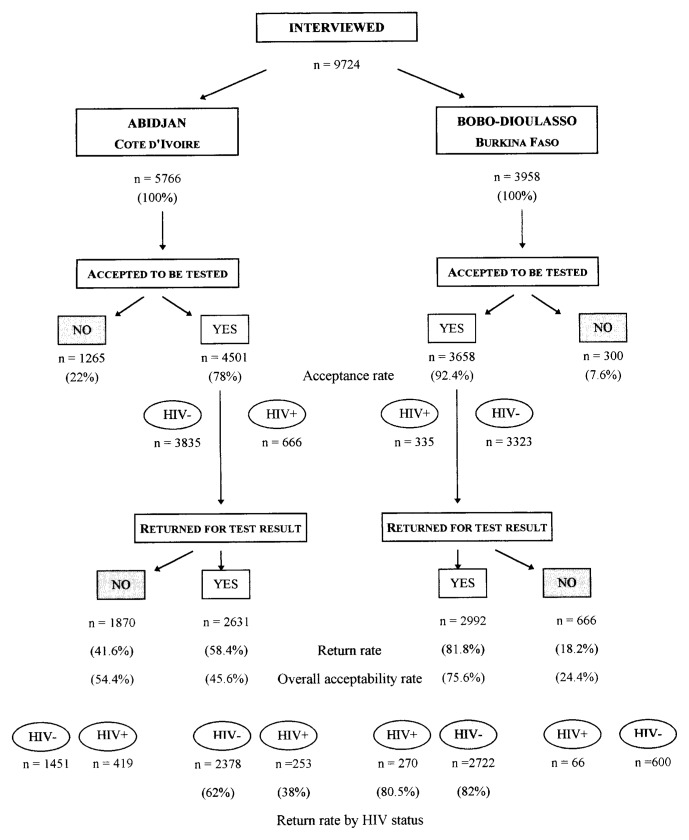

Acceptance rates, return rates and overall acceptability rates (proportion of women who both agreed to testing and returned for results) according to study sites are summarized in Fig. 1. Overall acceptability rate, which conditions access to the perinatal intervention, was lower in Abidjan than in Bobo-Dioulasso (45.6 versus 75.6%; P < 10−7). In Abidjan, only 38% of HIV-positive women returned for their results, whereas 62% of HIV-negative women received their results. In contrast, in Bobo-Dioulasso almost equal proportions of women (80%) received their results. In Bobo-Dioulasso, with a smaller number of women offered testing and a lower HIV seroprevalence, more HIV-positive women were potentially eligible to receive a prenatal intervention (n = 270) than in Abidjan (n = 253).

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of overall acceptability of HIV testing in pregnant women attending antenatal clinics in Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire and Bobo-Dioulasso, Burkina Faso, 1995–1996. Acceptance rate: the proportion of women who accepted HIV testing among women offered HIV testing; return rate: proportion of women who returned for test result among women who accepted HIV testing; overall acceptability rate: proportion of women who returned for test result among women offered HIV testing (acceptability of the two sessions of HIV counselling and testing, pretest and post-test).

Reasons for test refusal

More women refused the test in Abidjan (22%) than in Bobo-Dioulasso (7.6%). When the reasons for refusal were specified (1261 answers in Abidjan and 260 in Bobo-Dioulasso), the most common reason for refusal was ‘to seek agreement of the partner’ (45% in Abidjan versus 53% in Bobo-Dioulasso). Fear of AIDS (21 versus 41%) and the need to make a decision later at home (34 versus 6%) also conditioned refusal of HIV testing.

Reasons for failure to return for test results

More women failed to return for test results in Abidjan than in Bobo-Dioulasso (41.6 versus 18.2%). In Abidjan, 25 women were contacted by a sociologist to determine through an in-depth interview why they failed to return for post-test counselling: seven omitted their appointment, six received disapproval towards testing from the partner or the family circle, five had transport difficulties (distance, cost, availability, risky pregnancy), four said they thought they were having a test for ‘O-positive’ blood group instead of a ‘seropositive’ test and did not ask for their HIV test result, two came back to their village to deliver, and one thought that she would not cope with a HIV-positive result. In Bobo-Dioulasso, when information was available (n = 210), the main reasons were omission, disapproval of the partner, and delivery before the date of the post-test appointment.

Factors associated with test refusal

For both sites, the counsellors themselves and the high educational level of the women were associated with test refusal in the multivariate analysis (Table 3). In Bobo-Dioulasso, a high educational level of the partner remained also an important predictor for test refusal. In Abidjan, foreigners, employees, and women from the ‘other professional category’ including students, workers in the informal sector (e.g., hairdressers, craftsmen, cookers in the street) and unemployed persons, were 1.4 or 1.5 times more likely to refuse testing than others. In Abidjan, the probability of refusing testing also increased with age and almost doubled when age was 35 years or more. Ignorance of the main mode of HIV transmission (sexual) in Abidjan and the main means of prevention (condom) in Bobo-Dioulasso were associated with test refusal. However, knowledge of transmission by blood was more often observed among women who refused the test in Abidjan.

Table 3.

Factors associated with refusal for testing in antenatal clinics in Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire and Bobo-Dioulasso, Burkina Faso, 1995–1996 (multivariate analysis).

| Refusal for testing | Abidjan (n = 5766)

|

Bobo-Dioulasso (n = 3958)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P | |

| Counsellors | ||||

| No. 1 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| No. 2 | 1.8 (1.3–2.4) | < 0.001 | 1.5 (1.0–2.4) | 0.04 |

| Age (years) | ||||

| 18–19 | 1.0 | – | ||

| 20–24 | 1.1 (0.9–1.4) | 0.15 | – | |

| 25–29 | 1.5 (1.2–1.9) | < 0.001 | – | |

| 30–34 | 1.6 (1.3–2.1) | < 0.001 | – | |

| ≥ 35 | 1.9 (1.4–2.5) | < 0.001 | – | |

| Education | ||||

| None | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Primary | 0.9 (0.8–1.1) | 0.50 | 1.0 (0.6–1.6) | 0.76 |

| Higher | 1.4 (1.2–1.7) | < 0.001 | 2.1 (1.3–3.4) | 0.002 |

| Profession | ||||

| None | 1.0 | – | ||

| Merchant | 1.1 (0.9–0.3) | 0.10 | – | |

| Employee | 1.5 (1.0–2.2) | 0.02 | – | |

| Other | 1.4 (1.1–1.9) | 0.004 | – | |

| Foreigner | ||||

| No | 1.0 | – | ||

| Yes | 1.5 (1.3–1.9) | < 0.001 | – | |

| Partner’s education | ||||

| None | – | 1.0 | ||

| Primary | – | 1.2 (0.8–1.8) | 0.22 | |

| Higher | – | 2.6 (1.6–4.2) | <0.001 | |

| Knowledge of sexual transmission | ||||

| Quoted | 1.0 | – | ||

| Not quoted | 1.7 (1.4–2.0) | < 0.001 | – | |

| Parenteral transmission | ||||

| Quoted | 1.5 (1.3–1.7) | < 0.001 | – | |

| Not quoted | 1.0 | – | ||

| Condom for prevention | ||||

| Quoted | – | 1.0 | ||

| Not quoted | – | 2.1 (1.5–3.0) | <0.001 | |

OR, Odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Factors associated with failure to return for test results

Last trimester gestation (≥ 29 weeks) at the time of pretest was the only common characteristic on the two sites which was associated with failure to return in the multivariate analysis. In Bobo-Dioulasso, the counsellors themselves and length of union of 3–6 years compared with shorter duration were predictors of non-return (Table 4). In Abidjan, the Muslim group and the ‘other professional category’ were associated with non-return. However, the strongest predictor of non-return was an HIV-positive test result. Thus, HIV-infected women were three times less likely to return for results than uninfected women in Abidjan. This variable had not been introduced in the final multivariate model for Bobo-Dioulasso (P = 0.54 in the univariate analysis). Non-return for test results was more often observed by those women unaware of the existence of AIDS in Bobo-Dioulasso. Those who did not quote the condom as a means of prevention returned to seek their results less often than those who did in Abidjan.

Table 4.

Factors associated with failure to return in antenatal clinics in Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire and Bobo-Dioulasso, Burkina Faso, 1995–1996 (multivariate analysis).

| Failure to return | Abidjan (n = 5766)

|

Bobo-Dioulasso (n = 3958)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P | |

| Counsellor | ||||

| No. 1 | – | 1.0 | ||

| No. 2 | – | 2.1 (1.5–2.9) | < 0.001 | |

| Weeks of gestation | ||||

| < 29 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| ≥ 29 | 1.5 (1.3–1.7) | < 0.001 | 1.5 (1.2–1.9) | < 0.001 |

| Religion | ||||

| Christian | 1.0 | – | ||

| Muslim | 1.4 (1.2–1.7) | < 0.001 | – | |

| HIV infection status | ||||

| Negative | 1.0 | – | ||

| Positive | 3.0 (2.5–3.6) | < 0.001 | – | |

| Profession | ||||

| None | 1.0 | – | ||

| Merchant | 1.0 (0.9–1.2) | 0.30 | – | |

| Employee | 1.1 (0.7–1.8) | 0.52 | – | |

| Other | 1.7 (1.3–2.3) | < 0.001 | – | |

| Years in couple | ||||

| 0–2 | – | 1.0 | ||

| 3–6 | – | 1.3 (1.0–1.7) | 0.04 | |

| ≥ 7 | – | 0.8 (0.6–1.1) | 0.22 | |

| Knowledge of AIDS | ||||

| Yes | – | 1.0 | ||

| No | – | 1.9 (1.2–2.9) | 0.002 | |

| Condom for prevention | ||||

| Quoted | 1.0 | – | ||

| Not quoted | 1.2 (1.0–1.4) | 0.01 | – | |

OR, Odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first report on large-scale voluntary counselling and testing programmes, implemented in relation to an intervention to reduce vertical transmission of HIV. There are several potential limitations to our study. Some data, such as sexual behaviour, self-perception of HIV risk and characteristics of counsellors, known to have an impact in the decision of being tested [7,8] could not be collected. Another study limitation was a possible selection bias related to eligibility criteria for testing due to the conditions of the clinical trial that could not include women who came late in their pregnancy. Nevertheless, two cross-sectional serological surveys using an unlinked anonymous HIV screening method conducted on the same sites found similar HIV seroprevalences [2,9].

The antenatal clinics in Abidjan and Bobo-Dioulasso where the study was conducted were public sector institutions. The maternity wards associated with the project sites had 16 000 and 4000 births per year in Abidjan and Bobo-Dioulasso, respectively. These clinics were located in crowded districts where the socioeconomic level of the population was generally low. The two sites differed by their population characteristics, which may have influenced social behaviour and attitudes towards HIV testing (age, religion, educational level, marital status, profession and HIV seroprevalence). Refusing HIV testing and failing to return for results can be considered two aspects of a negative attitude towards HIV testing. Attitude towards HIV testing depends on weighting advantages and disadvantages of testing. In industrialized countries, the strongest predictors of intention to be tested have been reported to be the perceived benefit of the test and the perceived risk of HIV infection [8,10,11]. In these countries, acceptance rates reported in prenatal care sessions, before the introduction of zidovudine, were generally high and varied between 71 and 98%, and failure to return was rarely mentioned [12–15]. In developing countries, HIV-related health-care services are often non-existent and therefore less positively perceived. Most women in our study were unaware of our intervention because we informed only HIV-infected women who fulfilled specific criteria of inclusion in our trial after their post-test counselling. It could limit interest of women who perceived themselves at high risk of HIV infection in receiving their test results.

Several reasons could explain the relatively high acceptance rates of HIV testing in our study (78% in Abidjan and 92% in Bobo-Dioulasso). First, pretest counselling and testing was free, integrated into antenatal care services and implemented with trained social workers [16]. Although counsellors were trained to avoid coercion and promote free individual consent, it is conceivable that many of the participating women did not want or did not dare to contradict what a health professional proposed. Compared with Abidjan, women from Bobo-Dioulasso, who were less educated and came from traditional culture and environment, were more likely to adopt this attitude. This attitude could also partly explain substantial variations in both agreement for testing and return for test result. Second, women could perceive themselves at low risk of infection and easily accept the test because they were in good health and living with a partner, and because AIDS is still frequently associated with slim disease, prostitution and multipartnership. Differences in HIV seroprevalence between the two sites may have favoured a higher acceptance rate in Bobo-Dioulasso. Third, women previously tested were the exception in our sample unlike in industrialized countries where prior testing was shown to be an important reason to decline counselling and testing [8,10]. Fourth, acceptance of testing increases with counselling time [10]. In Bobo-Dioulasso, availability of counsellor, depending on recruitment in the antenatal clinic, has certainly played a role in the acceptance rate as well as a home visit after missing post-test counselling [17].

In Abidjan, women testing HIV-positive were three times more likely to fail to return for the test result than HIV-negative women. Such a finding has already been reported in Rwanda [4] and Kenya [5], but contrasts with studies from industrialized countries where no difference was reported [10,18]. Our findings suggested that HIV-infected women in Abidjan perceived themselves at risk of HIV infection, as documented by their past sexual behaviour (number of sexual partners) and the risk associated with their unfaithful regular partner. In Bobo-Dioulasso, women may not have been sufficiently aware about HIV infection and the visibility of the HIV epidemic was certainly lower than in Abidjan. Negative attitude towards HIV testing in women aged 35 years or more in Abidjan and living with a partner for 3–6 years in Bobo-Dioulasso could be explained by fear of loss of security and by domestic violence [19,20]. In industrialized countries, increasing refusal rates with age were also documented but not for the same reasons (limited perception of risk in particular) [10,21]. Among the reasons for refusal, the necessity to obtain agreement from the partner could be a more socially acceptable reason to decline an offer of testing or may alternatively highlight a real dependence of women to their partners. Fear of AIDS is also understandable in settings where discrimination against HIV-infected persons is still common. In Abidjan, this context could explain why employees, foreigners and persons who perceived themselves at risk of HIV infection more often refused testing or did not return for test results. Another reason to decline post-test counselling could be fear of depression following announcement of the results, which is believed to shorten life according to local beliefs [22].

Several common characteristics of the women from the two sites appeared to be associated with refusal rate and non-return rates. First, some counsellors had a negative impact on the decision to accept testing, probably related to their limited professional skills and empathic attitude. This finding has been noted elsewhere [8,10]. Second, women with high educational level, who supposedly have good access to information on HIV infection, were the most reluctant to accept testing in the two sites. These women were better able to perceive the risks of stigmatization and discrimination or may have perceived themselves at low risk of infection, as shown in other studies [12,21]. Further studies are needed to better understand which of these two attitudes is the most likely. Third, last trimester gestation (≥ 29 weeks) at the time of pretest was associated to failure to return in the two sites. This could be due to delivery before the date of the post-test appointment, transportation difficulties at this pregnancy stage, or precarious socioeconomic status. Factors that could negatively influence attitude towards HIV testing (high educational level, last trimester gestation) appeared to be more frequent in Abidjan than in Bobo-Dioulasso. Rapid test algorithms and same day results may improve return rates, although they require formal evaluation in the particular context of pregnancy when maternal HIV test result has consequences for both mother and child. Ideas and social norms from religious communities could influence women’s attitude towards HIV testing. For Muslim women, polygamy increases the complexity of disclosing the results and could increase the risks of dismissal. It is also likely that Muslim women in Abidjan, who were the minority, were fightened of stigmatization, [10,18], a situation strikingly different from that in Bobo-Dioulasso where Muslims represent the majority of the population.

In conclusion, HIV counselling and testing performed on a large scale was generally well accepted, probably because the majority of the pregnant women considered themselves at low risk of HIV infection. In Abidjan, however, women who perceived themselves at risk of being already infected were better able to analyse potential adverse consequences of testing and were more likely to develop a negative attitude towards HIV testing. This attitude may have an impact on peri-natal intervention strategies that depend on antenatal screening, such as antiretroviral prophylaxis [23], which was recently proven effective in the context of developing countries [24]. National AIDS control programmes should investigate means to combat discrimination and enhance medical management for HIV-infected persons in order to encourage access to prevention and care via HIV testing, particularly for pregnant women [25].

Acknowledgments

Sponsorship: This study was funded by the Agence Nationale de Recherches sur le SIDA (ANRS, Paris, France) and the French Ministry of Cooperation (ANRS Coordinated Action 12), and was supported by the National AIDS Control Programs of Burkina Faso and Côte d’Ivoire.

The authors thank directors of the health facilities where the study took place and also physicians, nurses and social workers of the DITRAME project for their daily contribution. The authors wish to acknowledge mothers and children participating to this study; without their collaboration, this study could not have been performed.

Appendix

The DITRAME (Diminution de la Transmission Mère Enfant du VIH) Study Group

Biostatistics: R. Lassalle, V. Leroy, R. Salamon (Bordeaux Coordination Unit).

Epidemiology: M. Cartoux (Bobo-Dioulassa Centre), F. Dabis (Coordinator of the DITRAME ANRS 049 trial, Bordeaux Coordination Unit), N. Meda (Coordinator of Bobo-Dioulasso Center), P. Msellati (Coordinator of Abidjan Centre), R. Ramon (Abidjan Centre).

Gynaecology/Obstetrics: A. Bazié, B. Dao (Bobo-Dioulasso Centre), R. Likikouet (Abidjan Centre), L. Mandelbrot (Principal Investigator, Paris Centre), C. Welffens-Ekra (Principal Investigator, Abidjan Centre).

Microbiology: D. Bonard, P. Combe, M. Dosso, T. Ouassa, F. Sylla-Koko (Abidjan Centre), L. Gautier-Charpentier, F.D. Ky, A Ouangré, O. Sanou, Y. Traore, P. Van de Perre (Bobo-Dioulasso Centre).

Molecular Biology: J.B. Kottan, C. Montcho, B. You (Abidjan Centre), A.M. Cassel-Beraud, O. Manigart, A. Simonon, D. Valea (Bobo-Dioulasso Centre), C. Rouzioux (Paris Centre).

Paediatrics: R. Camara, N. Elenga, M. Timité (Abidjan Centre), B. Nacro, F. Tall (Bobo-Dioulasso Centre).

Trial monitoring: G. Gourvellec, V. Noba, I. Viho (Abidjan Centre), O. Ky-Zerbo, I. Sombié, S. Tiendrebeogo, S. Yaro (Bobo-Dioulasso Centre).

Abidjan Health Facilities: Health Centres of Anonkoua-Koute, Ouassakara, Yopougon and Yopougon-Attie, the Centre Hospitalier Universitaire of Yopougon.

Bobo-Dioulasso Health Facilities: Health Centres of Accart-Ville, Farakan and Social Security, the Centre Hospitalier National Sourô Sanou.

Data and Safety Monitoring Board: J-F. Delfraissy (President, internal medicine specialist), D. Costagliola and C. Chouquet (statisticians), B. Bazin (trialist), P. Lepage (paediatrician), B. Masquelier (virologist) and K. Toure Coulibaly (obstetrician).

Footnotes

See Appendix for details.

References

- 1.Quinn TC. Global burden of the HIV pandemic. Lancet. 1996;348:99–106. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)01029-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sylla-Koko F, Anglaret X, Traore-Anaky MF, et al. Séroprévalence de l’infection par le VIH dans les consultations prénatales d’Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire, 1995. Méd Mal Infect. 1997;27:127–128. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sangaré L, Meda N, Lankoandé S, et al. HIV infection among pregnant women in Burkina Faso: a nationwide survey. Int J STD AIDS. 1997;8:646–651. doi: 10.1258/0956462971918797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ladner J, Leroy V, Msellati P, et al. A cohort study of factors associated with failure to return for HIV post-test counselling in pregnant women: Kigali, Rwanda, 1992–1993. AIDS. 1996;10:69–75. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199601000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kiarie J, Nduati R, John G, et al. Acceptability of antenatal HIV-1 screening. XI International Conference on AIDS; Vancouver. July 1996; abstract MoC211. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dabis F, Meda N, Msellati P, Cartoux M, Welffens-Ekra C, Mandelbrot L. Zidovudine to decrease mother-to-child transmission of HIV-1: a phase II study in West Africa, 1995–1996 (ANRS 049a). XI International Conference on AIDS; Vancouver. July 1996; abstract TuC444. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miller KS, Hennessy M, Wendell DA, Webber MP, Schoenbaum EE. Behavioral risks for HIV infection associated with HIV-testing decisions. AIDS Educ Prev. 1996;8:394–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Irvin KL, Valdiserri RO, Holmberg SD. The acceptability of voluntary HIV antibody testing in the United States: a decade of lessons learned. AIDS. 1996;10:1707–1717. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199612000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meda N, Zoundi MT, Ouangré A, et al. Séroprévalence de l’infection à VIH chez les femmes enceintes, Bobo-Dioulasso, Burkina Faso, 1996;. X International Conference on AIDS and STD in Africa; Abidjan. December 1997; abstract B386. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sorin MD, Tesoriero JM, LaChance-Mccullough ML. Correlates of acceptance of HIV testing and post-test counseling in the obstetrical setting. AIDS Educ Prev. 1996;8:72–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meadows J, Catalan J, Gazzard B. ‘I plan to have the HIV test’: predictors of testing intention in women attending a London antenatal clinic. AIDS Care. 1993;5:135–140. doi: 10.1080/09540129308258594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Royce RA, Donaldson KH. HIV counseling and testing in a cohort of pregnant women attending public prenatal clinics. XI International Conference on AIDS; Vancouver. July 1996; abstract WeC3593. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goldberg DJ, MacKinnon H, Smith R, et al. Prevalence of HIV among chilbearing women and women having termination of pregnancy: multidisciplinary steering group study. BMJ. 1992;304:1082–1085. doi: 10.1136/bmj.304.6834.1082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lindsay MK, Adefris W, Peterson HB, Williams H, Johnson J, Klein L. Determinants of acceptance of routine voluntary human immunodeficiency virus testing in an inner-city prenatal population. Obstet Gynecol. 1991;78:678–680. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Henrion R. Faut-il ou non tester les femmes enceintes? Lett Infectiol. 1988;13:455–456. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Slutsker L, Klockner R, Fleming D. Factors associated with failure to return for HIV post-test counseling. AIDS. 1992;6:1226–1227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cartoux M, Meda N, Van de Perre P, Sioho N, Mandelbrot L, Dabis F. HIV testing and counseling in African pregnant women in the context of interventions to reduce mother-to-child transmission. XI International Conference on AIDS; Vancouver. July 1996; abstract ThC411. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Valdiserri RO, Moore M, Gerber AR, Campbell CH, Dillon BA, West GR. A study of clients returning for counseling after HIV testing: implications for improving rates of return. Public Health Rep. 1993;108:12–18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Temmerman M, Ndinya-Achola J, Ambani J, Piot P. The right not to know HIV-test results. Lancet. 1995;345:969–970. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)90707-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Van der Straten A, King R, Grinstead O, Serufilira A, Allen S. Couple communication, sexual coercion and HIV risk reduction in Kigali, Rwanda. AIDS. 1995;9:935–944. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199508000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lindsay MK, Adefris A, Peterson HB, Williams H, Johnson J, Klein L. Determinants of acceptance of routine voluntary human immunodeficiency virus testing in an inner-city prenatal population. Obstet Gynecol. 1991;78:678–680. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cartoux M, Rouamba O, Meda N, Dabis F, Durand G, Salamon R. Le point sur le conseil lié au dépistage de l’infection par le VIH à Bobo-Dioulasso, Burkina Faso. Sante. 1996;6:7–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dabis F, Newell ML, Fransen L, De Vincenzi Ghent International Working Group. Prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV and its implications in developing countries. from research projects. 12th World AIDS Conference; Geneva, Switzerland. June 1998; abstract 23300. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Administration of zidovudine during late pregnancy and delivery to prevent perinatal HIV transmission. Thailand, 1996–1998. MMWR. 1998;47:151–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.De Cock KM, Johnson AM. From exceptionalism to normalisation: a reappraisal of attitudes and practices around HIV testing. BMJ. 1998;316:290–295. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7127.290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]