Abstract

Objectives

We conducted a systematic survey of the methodological literature to identify recommended approaches for how and what randomised clinical trial (RCT) authors should report on missing participant data and, on the basis of these approaches, to propose guidance for RCT authors.

Methods

We defined missing participant data (MPD) as missing outcome data for trial participants. We considered both categorical and continuous outcome data. We searched MEDLINE and the Cochrane Methodology Register for articles in which authors proposed approaches to reporting MPD from RCTs. We selected eligible articles independently and in duplicate and extracted data in duplicate. Using an iterative process of discussion and revisions, we used the findings to develop guidance.

Results

Of 10 501 unique citations identified, 13 articles reporting on 10 approaches proved eligible. The identified approaches recommend reporting the following aspects (from most to least frequently recommended): number of participants with MPD (n=10), reasons for MPD (n=7), methods used to handle MPD in the analysis (n=4), flow of participants (n=3), pattern of missingness (eg, whether at random) (n=3), differences in rates of MPD between trial arms (n=2), differences between participants with and without MPD (n=2), results of any sensitivity analyses (n=2), implication of MPD on interpreting the results (n=2) and methods used to prevent missing data (n=1). We propose a guide with nine items related to reporting the number, reasons, patterns, analytical methods and interpretation of MPD.

Conclusions

Most identified approaches invite trial authors to report the extent of MPD and the underlying reasons. Fewer approaches focus on reporting missingness patterns, methods for handling MPD and implications of MPD on results. Our proposed guidance could help RCT authors to better report, and readers to better identify participants with missing data.

Keywords: EPIDEMIOLOGY, Missing participant data, Randomized clinical trials, Systematic reviews

Strengths and limitations of this study.

First systematic survey addressing recommendations for the reporting of missing participant data in randomised clinical trials.

Explicit eligibility criteria with an appropriate search for relevant English language articles.

Systematic approaches to study selection, data abstraction and data synthesis.

A limitation in excluding non-English studies.

We did not implement duplicate data extraction, but a second reviewer checked all the extracted data for accuracy.

Background

Missing participant data is common in randomised clinical trials (RCT). A methodological survey of the top five general medical journals found that 191 of 235 (87%) of published trials reported missing participant data (MPD) for the primary outcome. The median percentage of participants with missing data was 6% (IQR 2–14%).1 Of the 191 trials reporting MPD, a third lost statistical significance when making plausible assumptions about the outcomes of missing participants.1

Systematic reviews, health technology assessments and clinical practice guidelines based on results from RCTs are vulnerable to bias that may result from MPD in the primary trials. In order to assess risk of bias resulting from MPD, consumers of the medical literature must identify the number and characteristics of trial participants for whom outcome data are missing. Reports of RCTs do not, however, always include this information in a consistent and clear manner. Indeed, Sylvestre et al2 found that information on missing values was not present in one-quarter of 93 Health Technology Assessments trial reports. Moreover, contact with authors of primary studies in the aforementioned survey revealed that unclear reporting was responsible for most inaccuracies in data abstraction.1

The Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) statement recommends standards for reporting of the findings of randomised trials.3 The standards address, among other issues, the reporting of loss to follow-up in trials. These ‘evidence-based’ recommendations were published in 2010, and would benefit from the identification on the current best available evidence on the topic.

The main objective of this study was to systematically review the methodological literature to identify recommended approaches for how and what RCT authors should report on missing participant data and, on the basis of these approaches, to propose guidance for RCT authors. This study was part of a larger project addressing the issue of missing participant data in trials and systematic reviews.

Methods

Definition

Missing participant data refers to missing outcome data for trial participants. This does not include missing participant baseline characteristics (eg, patient age).

Eligibility criteria

We included articles that met the following criteria:

Inclusion criteria

The paper discussing methods or conceptual approaches to addressing how and what RCTs should report on missing participant data. A typical example would be a paper on reporting standards such as the CONSORT statement.3 A paper describing challenges and solutions, or reviewing the literature for guidelines on how RCT should report on missing participant data would also be potentially eligible.

The paper should have devoted at least two paragraphs to discuss the topic of interest (criterion applied when reviewing the full texts).

The paper could have considered reporting of categorical and/or continuous data.

Exclusion criteria

Reports of systematic reviews or of trials.

Papers discussing how to prevent, minimise, handle, analyse or assess risk of bias associated with missing participant data.

Papers written in languages other than English.

Search strategy

Given that the focus of the study was on reporting in health-related trials, as opposed to dealing with MPD in statistical analyses, our search focused on the medical literature as opposed to the statistical literature. In August 2014, we searched MEDLINE, from its inception date using the OVID interface. We also searched the Cochrane Methodology Register. A researcher with experience in developing literature search strategies (IS) developed an initial search strategy. We subsequently used relevant articles identified through the pilot search to refine the strategy (see online supplementary appendix 1). In order to be comprehensive, we reviewed the CONSORT statement with its extensions.3–6

Article selection

Using a web-based systematic review software (SRDistiller), reviewers (LAK, TA, RB-P, JWB, AC-L, SE, BCJ, IN, IS, XS, PV and YZ) conducted screening in pairs and independently: first they screened titles and abstracts, and we obtained the full texts for those judged as potentially eligible by at least one of the two reviewers. Then, they screened these full texts for eligibility, compared their judgements and resolved disagreements by discussion, or, if necessary, with the help of a third reviewer (EAA). In order to ensure clarity and consistency, and prior to initiating the article selection process, we conducted calibration exercises and pilot tested the screening forms on a number of potentially eligible articles.

We calculated agreement for full-text screening stage using the κ statistic. We interpreted the degree of agreement between pairs of reviewers according to the criteria proposed by Landis and Koch7 (κ values of 0–0.20 represent slight agreement; 0.21–0.40 fair agreement; 0.41–0.60 moderate agreement; 0.61–0.80 substantial agreement; and >0.80 values represent almost perfect agreement).

Data abstraction and presentation

One reviewer (KS) abstracted data from included articles. A second reviewer (EAA) verified all the abstracted results. We used an iterative process to optimise the presentation of the abstracted data. We abstracted data from one eligible article at a time into a table with columns listing categories of reporting recommendations. We started with a preliminary list of categories including: number of participants with MPD, reasons for MPD and participant flow diagram. With every additional article being abstracted, we modified those categories as needed to integrate all relevant information from that article. We followed this approach until we abstracted data from all eligible articles. We conducted this process through face-to-face meetings. The remaining authors provided suggestions on how to improve data presentation. We used these recommendations as the basis for developing a guide for trialists.

Developing the guide

The two reviewers who abstracted the data developed an initial draft guide based on the identified recommendations in a number of face-to-face meetings (average of 2–3 times/week over a 4-month period from start of data abstraction up to finalisation of the guide). They used an iterative process of discussion and revisions to refine the draft. Specifically, they reviewed one eligible article at a time and modified the draft to integrate any new concepts in a coherent way. They followed this approach until they reviewed all eligible articles. The remaining members of the team reviewed and commented on the draft guide through email communication. These team members include clinical epidemiologists with extensive experience in clinical trials and systematic review methodologies. The discussion was informed by the team members’ previous work on dealing with missing participant data in published trials.1 8–11 One of the challenges that we encountered was the inconsistency of the terminology used across papers to refer to the same concepts. While the team had to agree on which terminology to use, we decided, for transparency and accuracy purposes, to report in an appendix the terminology used in each included paper.

Results

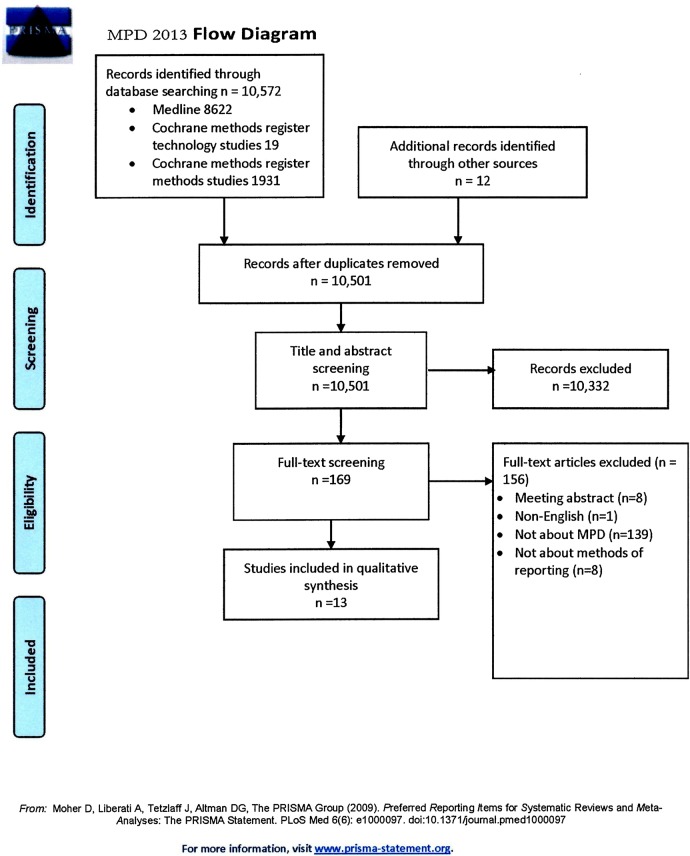

Our search strategy identified 10 572 citations, of which 13 proved eligible (figure 1). Agreement between authors for study eligibility was almost perfect (κ=0.95). The 13 articles described 10 approaches; 1 of the approaches was the CONSORT statement, and three articles reported CONSORT extensions. These extensions were for patient reported outcomes (PROs),4 harm5 and cluster trials.6

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram (MPD, missing participant data).

Recommended approaches

We report in online supplementary appendix 2 the recommendations of each included paper. The text in the appendix reproduces the paper's own terminology for referring to missing participant data. The recommendations can be summarised as follows:

Report methods used to prevent MPD;

Report number of participants with MPD;

Report differences in rates of MPD between trial arms;

Report the reasons for MPD;

Report a flow of participants;

Report any differences between participants with and without MPD;

Report pattern of missingness (eg, whether at random);

Report methods for handling MPD in analysis;

Report results of any sensitivity analyses;

▸ Discuss implication of MPD on interpreting the results.

We report in online supplementary appendix 3 the definitions of the different patterns of missingness, as well as the terminology used by each paper to describe the different reasons for missing participant data. Papers used a range of terms and different approaches to classifying missing data. A number of papers used terms that describe the underlying cause of missingness:

Health status related: for example, death, illness, progressive disease (n=4);

Participant choice related: lack of interest, lack of time, bothered by question (n=2);

Technically related: questionnaire not given, wrong questionnaire, wrong questionnaire instructions, transportation problem (n=2).

A number of papers used terms that describe the pattern of missingness (n=5):

Informative (non-random) censoring versus non-informative (random) censoring;

Missing at random versus not missing at random versus missing completely at random.

Intermittent or non-monotone missingness.

One paper used terms that describe who caused the missingness: researcher initiated (eg, removal of participants) versus participant related (eg, withdrawal).

Table 1 describes each of the 10 approaches which specific recommendations are covered (only as frequency). Three articles specifically address issues in reporting missing data in trials using continuous outcome measures such as PROs.4 12 13 The remaining articles apply to either categorical or continuous outcome measures. The identified approaches recommend reporting the following aspects (from most to least frequently recommended): number of participants with MPD (n=10), reasons for MPD (n=7), methods used to handle MPD in the analysis (n=4), flow of participants (n=3), pattern of missingness (eg, whether at random) (n=3), differences in rates of MPD between trial arms (n=2), differences between participants with and without MPD (n=2), results of any sensitivity analyses (n=2), implication of MPD on interpreting the results (n=2), and methods used to prevent missing data (n=1).

Table 1.

Summary of proposed approaches for reporting MPD

| Author | Methods used to prevent missing data | Number of participants with MPD | Differences in rates of MPD between trial arms | Reasons for MPD | Flow of participants | Differences between participants with and without MPD | Pattern of missingness (eg, whether at random) | Methods for handling MPD in analysis | Results of any sensitivity analyses | Implication of MPD on interpreting the results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Staquet et al13 | ✓* | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Bernhard et al12 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Troxel et al20 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓† | |||||||

| Liu et al21 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Amico et al22 | ✓* | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Sterne et al23 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Polit and Gillespie24 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Al-Shurafa et al25 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Gewandter et al26 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| CONSORT‡3 | ✓* | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Number of studies recommending it | 1 | 10 | 3 | 7 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 2 |

*These approaches further recommended reporting missing data by study arm.

†Troxel et al recommended examining patient-related and institution-related factors affecting missing data rates descriptively or by using logistic regression models. ‡Elements recommended by CONSORT extensions, not already included in the main statement: (1) extension for harms, none; (2) extension for cluster trials: reporting for each group, the missing participant data for both clusters and individual cluster members; (3) extension for patient reported outcomes, reporting outcome data at baseline and at subsequent time points, interpreting any supportive (eg, sensitivity) analyses.

MPD, missing participant data.

Proposed guide

Box 1 presents our proposed guide on how RCT authors should report missing participant data. These include items relevant to the report of both categorical and continuous variables as well as items specific to the report of continuous variables. The guide does not specify the format of reporting, which could be narrative, tabular, or graphical (eg, study flow).

Box 1. Proposed guide on how trial authors should report missing participant data.

Recommendations to report:

A priori plans to minimise missing data, to categorise missing data according to reasons (including criteria for informative missingness), and to deal with missing data (including specific sensitivity analyses)

Number of participants in each arm with missing data; if differing across outcomes, separate accounting for each outcome

Reasons for missingness of data reported separately for each arm (eg, health related vs technical cause), and the pattern of missingness (eg, whether at random)*

Comparison of the baseline characteristics of participants with and without missing participant data reported separately for each study arm (alternatively, comparison of the baseline characteristics of participants with missing participant data in the two study arms)†

Analytical approach used in handling MPD in the main analysis (eg, complete case analysis, pattern-mixture model), and whether different from prospectively planned analysis.

Results of sensitivity analyses to assess the robustness of the main findings under different assumptions about the outcomes of participants with missing data)

Impact of missing participant data (MPD) on interpretation of trial results, particularly in terms of confidence in the effect estimates.

Specifically, for continuous data

MPD by item for each arm when a questionnaire is used as a measuring tool†

MPD trend over time for repeated measures (eg, intermittent missingness with questionnaires completed at each scheduled assessment)†

*We suggest the following classification of reasons: ‘mistakenly randomised and inappropriately excluded’, ‘did not receive any treatment’ (includes cases of not receiving any dose of medication), ‘withdrew consent’, ‘outcome not assessable’, ‘dead’, ‘experienced adverse events’, ‘non-compliant’, ‘crossed-over’, ‘moved away’, and ‘missing data, reason not specified’. The trial authors could additionally comment on the randomness of missingness of each of these reasons.

†This information could be included in an appendix.

Discussion

The majority of approaches to reporting missing data recommend that trial authors report the extent of missing participant data and the underlying reasons. Fewer approaches focus on patterns of missingness, methods for handling MPD and implications of MPD on results.

This guidance builds on, and complements the CONSORT statement, as it relates to MPD. CONSORT wisely recommends reporting a flow diagram of the progress of participants through the phases of the trial by study group, including loss to follow-up with reasons, and the number of participants excluded from the analysis. Our proposed guidance is more specific (eg, addressing missing data for each outcome separately) and wider in scope (eg, handling MPD in the main analysis and in any sensitivity analysis, evaluating impact of MPD on interpretation of results). Publication or sharing of trial raw individual participant data, would automatically allow meeting many of the recommendation (eg, participants with missing data by arm, by outcome, or by item; baseline characteristics of participants with missing data).

The recently published SPIRIT (Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials) statement provides recommendations for a “minimum set of scientific, ethical, and administrative elements that should be addressed in a clinical trial protocol.”14 Although not strictly eligible for this study, the statement highlights the importance in explicit reporting of MPD, starting with the protocol. For example, it invites trialists to prespecify the methods of statistical analysis of the primary outcome and how missing data will be handled. This includes details of the planned methods for imputing MPD, including which variables will be used in the imputation process. The guidance also includes outlining the planned approach to making the final methodological choices when these cannot be prespecified (eg, the method of handling missing data which might depend on examining patterns of ‘missingness’ when data become available).

While the focus of this paper is to improve the reporting of MPD to assist in their handling in systematic reviews, avoiding or minimising MPD remains the ideal solution for MPD.15–17 This shifts the burden of addressing the problem from statisticians to trialists. There has been a number of prominent guidance on this by a number of bodies such as the Food and Drug Administration.18

Strengths and limitations

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first systematic survey addressing recommendations for the reporting of MPD in RCTs. Strengths of this survey include explicit eligibility criteria, an appropriate search for relevant English language articles, and systematic approaches to study selection, data abstraction and data synthesis. One limitation of the review is the exclusion of non-English studies. Although there is evidence that exclusion of non-English studies might result in the loss of an appreciable number of eligible studies in clinical systematic reviews,19 this may be less of an issue for methodological reviews. We did not implement duplicate data extraction, but a second reviewer checked all extracted data for accuracy. Also, we did not keep track of the frequency of agreements and disagreements regarding which items are included in the final version of the guide.

Conclusion

We have summarised the recommended approaches for how trialists should report MPD, and proposed guidance based on our findings. Our findings have implications for trialists as well as editors of medical journals. Both of these groups may wish to consider adhering to this guidance when reporting trials to help the users of the medical literature to adequately identify participants with missing data to judge the validity of trial findings. Adherence to our suggestions would also allow systematic reviewers to identify MPD in order to conduct meta-analyses that adequately take them into account. The authors of the CONSORT statement may consider integrating our guidance in a future update of that statement.

Our findings have implications also for future research. There is a need to assess to what extent reports of RCTs adhere to those reporting recommendations, particularly to assess response to any initiatives to improve MPD reporting. More generally, there is a need for more research on how to prevent, minimise, handle, analyse and assess risk of bias associated with MPD.

Footnotes

Contributors: EAA, PA-C and GHG contributed to the conception and design. EAA and IS were responsible for design of search strategy. LAK, TA, RB-P, JWB, AC-L, SE, BCJ, IN, IS, XS, PV and YZ selected the paper. EAA and KS contributed to data abstraction, data synthesis and manuscript drafting. EAA, KS, LAK, TA, RB-P, JWB, AC-L, SE, BCJ, IN, IS, XS, PV, PA-C and GHG were responsible for interpretation of results. EAA, KS, LAK, TA, RB-P, JWB, AC-L, SE, BCJ, IN, IS, XS, PV, YZ, PA-C and GHG were responsible for manuscript review and approval.

Funding: This paper is part of a project on addressing missing trial participant data in systematic reviews funded by the Cochrane Collaboration.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Akl EA, Briel M, You JJ et al. . Potential impact on estimated treatment effects of information lost to follow-up in randomised controlled trials (LOST-IT): systematic review. BMJ 2012;344:e2809 10.1136/bmj.e2809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sylvestre Y. CONSORT: missing data guidelines, the effects on HTA monograph reporting. Trials 2011;12(Suppl 1):A61 10.1186/1745-6215-12-S1-A61 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D, CONSORT Group. CONSORT 2010 Statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. J Clin Epidemiol 2010;63:834–40. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Calvert M, Blazeby J, Altman DG et al. . Reporting of patient-reported outcomes in randomized trials: the CONSORT PRO extension JAMA 2013;309:814–22. 10.1001/jama.2013.879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ioannidis JP, Evans SJ, Gøtzsche PC et al. . Better reporting of harms in randomized trials: an extension of the CONSORT statement. Ann Intern Med 2004;141:781–8. 10.7326/0003-4819-141-10-200411160-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Campbell MK, Piaggio G, Elbourne DR et al. , CONSORT Group. Consort 2010 statement: extension to cluster randomised trials. BMJ 2012;345:e5661 10.1136/bmj.e5661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977;33:159–74. 10.2307/2529310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Akl EA, Kahale LA, Agoritsas T et al. . Handling trial participants with missing outcome data when conducting a meta-analysis: a systematic survey of proposed approaches. Syst Rev 2015;4:98 10.1186/s13643-015-0083-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Akl EA, Johnston BC, Alonso-Coello P et al. . Addressing dichotomous data for participants excluded from trial analysis: a guide for systematic reviewers. PLoS ONE 2013;8:e57132 10.1371/journal.pone.0057132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ebrahim S, Akl EA, Mustafa RA et al. . Addressing continuous data for participants excluded from trial analysis: a guide for systematic reviewers. J Clin Epidemiol 2013;66:1014–21.e1. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.03.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ebrahim S, Johnston BC, Akl EA et al. . Addressing continuous data measured with different instruments for participants excluded from trial analysis: a guide for systematic reviewers. J Clin Epidemiol 2014;67:560–70. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.11.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bernhard J, Cella DF, Coates AS et al. . Missing quality of life data in cancer clinical trials: serious problems and challenges. Stat Med 1998;17:517–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Staquet M, Berzon R, Osoba D et al. . Guidelines for reporting results of quality of life assessments in clinical trials. Qual Life Res 1996;5:496–502. 10.1007/BF00540022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chan AW, Tetzlaff JM, Gøtzsche PC et al. . SPIRIT 2013 explanation and elaboration: guidance for protocols of clinical trials. BMJ 2013;346:e7586 10.1136/bmj.e7586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Little RJ, D'Agostino R, Cohen ML et al. . The prevention and treatment of missing data in clinical trials. N Engl J Med 2012;367:1355–60. 10.1056/NEJMsr1203730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Little R, Cohen M, Dickersin K et al. . The design and conduct of clinical trials to limit missing data. Stat Med 2012;31:3433–43. 10.1002/sim.5519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O'Neill R, Temple R. The prevention and treatment of missing data in clinical trials: an FDA perspective on the importance of dealing with it. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2012;91:550–4. 10.1038/clpt.2011.340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guidance for Industry. Patient-reported outcome measures: use in medical product development to support labeling claims. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration, 2009. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM193282 (accessed 13 Jan 2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Busse JW, Bruno P, Malik K et al. . An efficient strategy allowed English-speaking reviewers to identify foreign-language articles eligible for a systematic review. J Clin Epidemiol 2014;67:547–53. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.07.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Troxel AB, Fairclough DL, Curran D et al. . Statistical analysis of quality of life with missing data in cancer clinical trials. Stat Med 1998;17:653–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu M, Wei L, Zhang J. Review of guidelines and literature for handling missing data in longitudinal clinical trials with a case study. Pharm Stat 2006;5:7–18. 10.1002/pst.189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Amico KR, Harman JJ, O'Grady MA. Attrition and related trends in scientific rigor: a score card for ART adherence intervention research and recommendations for future directions. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 2008;5:172–85. 10.1007/s11904-008-0026-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sterne JA, White IR, Carlin JB et al. . Multiple imputation for missing data in epidemiological and clinical research: Potential and pitfalls. BMJ 2009;338:b2393 10.1136/bmj.b2393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Polit DF, Gillespie BM. Intention-to-treat in randomized controlled trials: recommendations for a total trial strategy. Res Nurs Health 2010;33:355–68. 10.1002/nur.20386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alshurafa M, Briel M, Akl EA et al. . Inconsistent definitions for intention-to-treat in relation to missing outcome data: Systematic review of the methods literature. PloS ONE 2012; 7:e49163 10.1371/journal.pone.0049163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gewandter JS, McDermott MP, McKeown A et al. . Reporting of missing data and methods used to accommodate them in recent analgesic clinical trials: ACTTION systematic review and recommendations. PAIN 2014;155:1871–7. 10.1016/j.pain.2014.06.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]