Abstract

Objectives

To evaluate (1) the state of the art in sustainability research and (2) the outcomes of professionals’ adherence to guideline recommendations in medical practice.

Design

Systematic review.

Data sources

Searches were conducted until August 2015 in MEDLINE, CINAHL, EMBASE, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) and the Guidelines International Network (GIN) library. A snowball strategy, in which reference sections of other reviews and of included papers were searched, was used to identify additional papers.

Eligibility criteria

Studies needed to be focused on sustainability and on professionals’ adherence to clinical practice guidelines in medical care. Studies had to include at least 2 measurements: 1 before (PRE) or immediately after implementation (EARLY POST) and 1 measurement longer than 1 year after active implementation (LATE POST).

Results

The search retrieved 4219 items, of which 14 studies met the inclusion criteria, involving 18 sustainability evaluations. The mean timeframe between the end of active implementation and the sustainability evaluation was 2.6 years (minimum 1.5–maximum 7.0). The studies were heterogeneous with respect to their methodology. Sustainability was considered to be successful if performance in terms of professionals’ adherence was fully maintained in the late postimplementation phase. Long-term sustainability of professionals’ adherence was reported in 7 out of 18 evaluations, adherence was not sustained in 6 evaluations, 4 evaluations showed mixed sustainability results and in 1 evaluation it was unclear whether the professional adherence was sustained.

Conclusions

(2) Professionals’ adherence to a clinical practice guideline in medical care decreased after more than 1 year after implementation in about half of the cases. (1) Owing to the limited number of studies, the absence of a uniform definition, the high risk of bias, and the mixed results of studies, no firm conclusion about the sustainability of professionals’ adherence to guidelines in medical practice can be drawn.

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first systematic review of the literature that has considered professionals’ adherence to clinical practice guidelines more than 1 year after active implementation. This review shows that in half of the sustainability studies professionals fully sustained in their adherence to a clinical practice guideline.

This review showed that sustainability research is a relatively new and underexplored field in healthcare.

Sustainability research is not well indexed in electronic databases, and text word searches are prone to high recall and low specificity. However, it is likely that the use of a broad variety of search terms that covered sustainability has downsized the number of relevant studies missed and is a strength of the review.

The number of studies and the methodological quality of the studies focusing on the sustainability of professionals’ adherence are limited. This makes it difficult to draw firm conclusions.

Introduction

Quality of care can be improved by decreasing unwarranted practice variation between professionals. One way to reduce practice variation is by transferring evidence-based knowledge into daily practice. To facilitate the translation of the most recent evidence into practice, guidelines are developed and implemented. Following the Institute of Medicine (IOM), clinical practice guidelines are “statements that include recommendations intended to optimize patient care that are informed by a systematic review of evidence and an assessment of the benefit and harms of alternative care options”.1 Guidelines contain practical evidence-based advice for professionals and patients and aim to improve the quality of care.2 In general, uptake of guidelines does not happen spontaneously and often an active implementation approach is required.3 Moreover, once a guideline is successfully implemented in practice, it may be difficult to sustain the quality improvements over a longer period of time. People tend to fall back into old routines4 which may impact long-term adherence to a guideline.

The road towards sustainability of healthcare innovations into practice is suggested to be a dynamic process,5 and sustainable adherence may not be self-evident without continued efforts. Sustainable change of professionals’ behaviour has the potential to result in more optimal healthcare delivery and efficiency. Not sustaining quality improvements can result in nihilistic attitudes towards future innovation. In recent years, sustainability has gained attention in healthcare. Unfortunately, the concept of sustainability is still underdeveloped.6 7 Some existing reviews studied sustainability from a wide healthcare perspective, including studies varying from medical care to public health. Results showed that determinants of sustainability varied widely between healthcare areas8 9 and suggest that partial sustainability of healthcare innovations is more common than full sustainability.10

In this systematic review, the scope of sustainability research will be narrowed to professionals’ adherence to clinical practice guidelines in medical care. The aim of the current review was to evaluate the state of the art in sustainability research and the level of sustained professionals’ adherence to guideline recommendations in medical practice more than 1 year following the cessation of the implementation project.

Methods

Eligibility criteria

Studies needed to be focused on sustainability and on clinical practice guidelines. Sustainability was described as “Sustainability of change exists when a newly implemented innovation continues to deliver the benefits achieved over a longer period of time, certainly does not return to the usual processes and becomes ‘the way things are done around here’,11 even after the implementation project is no longer actively carried out, until a better innovation comes along”.12 Studies had to include at least two measurements: one before (PRE) or immediately after implementation (EARLY POST) and one measurement longer than 1 year after active implementation (LATE POST). All activities to facilitate the adherence to clinical practice guidelines were labelled as part of the implementation project. Studies needed to be focused on professionals’ adherence to a clinical practice guideline. Studies only using self-reported adherence were excluded to reduce the chance of social desirability bias and an overestimation of results.13 Lastly, studies had to focus on medical care. Participants had to be healthcare professionals who deliver direct patient care. There were no restrictions on study design of the research articles.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched MEDLINE (OvidSP; 1946 to February 2014), CINAHL (EBSCO Host; 1982 to February 2014), EMBASE (OvidSP; February 2014), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) and the Guidelines International Network (GIN) library for studies. The electronic search strategy was designed to focus on sustainability of guideline recommendations. Free-text terms and MeSH terms regarding sustainability, quality improvement, impact and guideline recommendations were used. An information expert checked the developed search strategies (see online supplementary file 1). Before final analyses, update searches were performed to identify possible additional studies (26 June 2014 and 4 August 2015).

Searching other resources

A snowball strategy was performed, in which the reference sections of reviews6–10 14–16 and research papers on sustainability17 18 were searched. Also, databases such as PubMed and the Web of Knowledge Science Citation Index were used to locate publications and publications citing the original references. The process was repeated for any new relevant publication found.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

All records were merged into a bibliographic database and screened independently by two reviewers (SMCA and JJAdG) based on title and abstract. Full-text screening was performed by two reviewers (SMCA and JJAdG). Disagreement on selection was resolved in consensus meetings with a third reviewer (TvdW). Reasons for exclusion were documented during the full-text screening. If more clarification or details of a study were needed, an author was contacted. Authors of conference abstracts were emailed and were asked to send the research protocol. Duplicate papers were identified, and all papers published on one study were used for retrieving information.

Data extraction and management

Data of the methodology and results were independently extracted by two reviewers (SMCA, JJAdG), guided by a predefined data extraction form. Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) Data Collection Checklist19 items (eg, location of care, type of targeted behaviour, implementation interventions) were integrated in the data extraction form. The data extraction form was developed by the authors and was pilot tested. The following study characteristics were recorded: study design, publication year, whether the study was executed in a single centre or in multiple centres, type of targeted behaviour, location of care, the name of the clinical practice guideline, clinical specialty, the implementation activities used and whether or not the implementation strategy was externally guided. An externally guided implementation strategy is a strategy which is lead and supported by an external expert organisation. With respect to the methodology of the sustainability evaluation, the following data were extracted: the timeframe between the end of the implementation strategy and the sustainability evaluation, the applied definition of sustainability, the data collection method, whether the evaluation was performed on patient, hospital or multiple hospital level and whether the sustainability evaluation was performed on single or multiple centre level. With respect to the outcome measures of the studies, data on the professionals’ adherence rates before, early after implementation and longer than 1 year after implementation, and the authors’ comments with respect to the sustainability of professionals’ adherence were extracted. Adherence was presented in terms of proportion of patients receiving treatment according to the clinical practice guideline recommendations. If sustainability of professionals’ adherence to a clinical practice guideline was evaluated at multiple postimplementation moments, the latest evaluation was selected as LATE POST measurement. The authors (SMCA and JJAdG) checked if updates of the clinical practice guidelines had become available in the postimplementation phase (eg, between the EARLY POST and the LATE POST measurement), which may explain reduced professionals’ adherence. Disagreement on data extraction was resolved in consensus meetings with a third reviewer (TvdW).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Risk of bias assessment was independently conducted by two authors using the Downs and Black checklist for randomised and non-randomised studies.20 This is a checklist which can be used for checking the risk of bias of original research articles of various study designs. Results were interpreted under consideration of risk of bias. The assessments were also used for recommendations for further research by identifying elements of studies that can be improved in future studies. The checklist was adapted to the research question. Risk of bias of the studies was presented on reporting, external validity, internal validity (bias and confounding), power and overall level.

Analysis

The analysis was narrative. This included a summary of the methodological characteristics of the sustainability evaluations, descriptions of the level of sustainability as mentioned by the author, and the level of sustained professionals’ adherence compared with results achieved immediately after implementation. Sustainability was considered to be successful if performance in terms of professionals’ adherence was fully maintained in the late postimplementation phase. A sensitivity analysis was performed by applying a 90% instead of 100% adherence criterion of sustainability.

Results

Description of studies

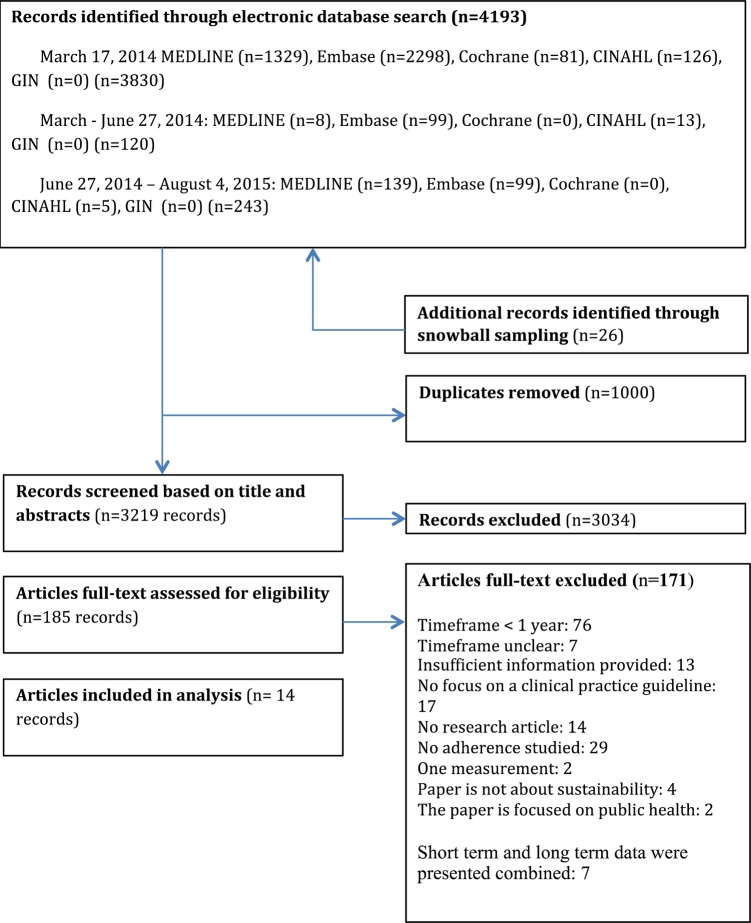

For this review, 4219 items were retrieved and screened based on title and abstract, and 185 studies were assessed based on full-text reading. Figure 1 shows the study selection process as recommended by the PRISMA statement21 (see online supplementary file 2). Fourteen studies met the inclusion criteria for this review, describing 18 sustainability evaluations.22–35 Table 1 presents the characteristics of the included studies. Two publications were published before and 12 after 2000.23 33 In six studies, the targeted behaviour was prescribing,24 25 28 30 33 35 in four studies procedures,29 31 32 34 in three studies general management of a problem22 26 27 and in one study23 general management of a problem and prescribing. The location of care was inpatient in five studies,23 28 29 32 34 outpatient in four studies24–26 35 and mixed in five studies.22 27 30 31 33

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included studies

| Study ID | Study design | Clinical practice guideline | Clinical specialty | Clinical practice guideline was updated in the postimplementation phase* (yes/no) | Time frame (years) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ament et al,22 The Netherlands | Case series | Guideline to facilitate short stay for breast cancer surgery36 | Surgery | Between 2007 and 2012: no42 43† | 5 |

| Benenson et al,23 UK | Case series | Clinical pathway for pneumonia44 | Various | Between 1995 and 1997: no45 46 | 3 |

| Cates,24 UK | Case series | Guideline for antibiotic prescription for children with earache and inflamed eardrums who are not unduly ill47 | General practice | Between 1998 and 2001: no48† | Centre 1: 3; centre 2: 2 |

| Enriquez-Puga et al,25 UK | RCT | (1) Antidepressant prescription guideline and49 (2) Antibiotic prescription guideline50 Control group: intervention groups were each other's control group |

General practice | Guideline 1 between 2003 and 2004: yes51 Guideline 2 between 2003 and 2004: no50 |

1.5 |

| Forsner et al,26 Sweden | RCT | Clinical guideline (1) for depression52 and (2) for suicidal behaviours48 Control group: received the guideline but were not included in the intervention |

Psychiatry | UTD | 1.5 |

| Gerber et al,35 USA | Case series | Outpatient antimicrobial stewardship intervention53 | Pediatric primary care | Between 2011 and 2014: no53 | 1.5 |

| Higuchiet al,27 Canada | Case series | (1) Adult Asthma Care Best Practice Guideline54 and (2) Reducing Foot Complications for People with Diabetes Best Practice Guideline55 | (1) Various (2) Various |

Guideline 1 between 2002 and 2006: yes56 Guideline 2 between 2003 and 2006: yes57 |

(1) 4 (2) 3 |

| Kelly,28 Australia | Case series | Guideline for nurse managed titrated narcotic analgesia58 | Emergency medicine | UTD | 2 |

| Knops et al,29 The Netherlands | Case series | (1) A fluid balance guideline for oncology patients38 (2) A body temperature guideline for postoperative patients59 |

(1) Various (2) Surgery |

Guideline 1 UTD (local guideline) Guideline 2 UTD (local guideline) |

7 |

| Loszadi et al,30 UK | Case series | Guidelines for the prevention and management of corticosteroid-induced osteoporosis60 | Neurology | UTD | Unknown, >2 |

| McLaws et al,31 Australia | Case series | Guidelines on Hand Hygiene in Health Care61 | Various | Between 2007–2008: no61 | 1.5 |

| Stéphan et al,32 Switzerland | Case series | Guideline for urine catheterization management for surgical procedures62 | Orthopaedic / abdominal surgery | UTD (local guideline) | 1.5 |

| Wakefield et al,33 USA | Case series | Guideline for the use of transdermal fentanyl for chronic pain33 | Various | UTD | 1.5 |

| Williams et al,34 UK | Case series | Guideline for the repair and follow-up of third degree tears63 | Obstetrics and gynaecology | UTD (local guideline) | 2 |

*The cpg was updated between the POST and LATE POST measurement (yes) or was not updated between the POST and LATE POST measurement (no). †Not updated with respect to the key recommendations of the guideline. The guideline was adopted in national guidelines in the postimplementation phase.

RCT, randomised controlled trial; UTD, unable to determine.

The implementation strategy was described in 13 studies (table 2).22–27 29–41 According to the EPOC checklist classification, in one study,24 a single element implementation strategy was executed while in the other 12 studies a multifaceted implementation strategy was executed. Implementation activities were professional-targeted interventions (n=12) {Ament, 2014 #20; de Kok, 2010 #33; Ament, 2014 #34; Benenson, 1999 #21; Enriquez-Puga, 2009 #23; Forsner, 2010 #24; Higuchi, 2011 #25; Knops, 2010 #27; Mank, 2003 #35; Knops, 2010 #27; Lozsadi, 2006 #28; Storm-Versloot, 2012 #36; Pantle, 2009 #37; Stephan, 2006 #30; Wakefield, 1998 #31; Williams, 2003 #32; Gerber, 2013 #67; Gerber, 2014 #69}, followed by organisational interventions (n=6)22 23 26 33 34 36 37 39 40 and financial interventions (n=1).27 In six studies, the implementation strategy was facilitated by external experts.22 25–27 31 35 In one study, it was unclear whether the implementation strategy was externally supported.28

Table 2.

Implementation strategies as described by the authors

| Professional interventions |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author | Distribution of educational materials | Educational meetings | Local consensus processes | Educational outreach visits | Local opinion leaders | Patient-mediated interventions |

| Ament22 | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| Benenson23 | ● | |||||

| Cates24 | ||||||

| Enriquez-Puga,25 antidepressant prescription guideline | ● | ● | ● | |||

| Enriquez-Puga,25 antibiotic prescription guideline | ● | ● | ● | |||

| Forsner,26 depression guideline | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| Forsner,26 suicidal behaviours guideline | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| Gerber35 | ● | |||||

| Higuchi,27 Adult Asthma Care Best Practice Guideline | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||

| Higuchi,27 Reducing Foot Complications for People with Diabetes Best Practice Guideline | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||

| Kelly28* | ||||||

| Knops29 fluid balance guideline for oncology patients* | ||||||

| Knops29 body temperature guideline for postoperative patients | ● | ● | ||||

| Loszadi30 | ● | |||||

| McLaws31 | ● | ● | ● | |||

| Stéphan32 | ● | ● | ● | |||

| Wakefield33 | ● | ● | ||||

| Williams34 | ||||||

| Professional interventions |

Financial interventions | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author | Audit and feedback | Reminders | Marketing | Mass media | Other | Other |

| Ament22 | ● | |||||

| Benenson23 | ||||||

| Cates24 | ||||||

| Enriquez-Puga,25 antidepressant prescription guideline | ● | ● | ||||

| Enriquez-Puga,25 antibiotic prescription guideline | ● | ● | ||||

| Forsner,26 depression guideline | ● | Participation in local network | ||||

| Forsner26, suicidal behaviours guideline | ● | Participation in local network | ||||

| Gerber35 | ● | |||||

| Higuchi,27 Adult Asthma Care Best Practice Guideline | ● | ● | Additional funding to replace nurses while they performed implementation activities | |||

| Higuchi,27 Reducing Foot Complications for People with Diabetes Best Practice Guideline | ● | ● | Additional funding to replace nurses while they performed implementation activities | |||

| Kelly28* | ||||||

| Knops29 fluid balance guideline for oncology patients* | ||||||

| Knops29 body temperature guideline for postoperative patients | ● | ● | ||||

| Loszadi30 | ● | |||||

| McLaws31 | ● | ● | ● | |||

| Stéphan32 | ● | ● | ● | |||

| Wakefield33 | ● | |||||

| Williams34 | ● | |||||

| Organisational interventions |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author | Revision of professional roles | Clinical multidisciplinary team | Formal integration of services | Skill mix changes | Continuity of care | Changes in physical structure, facilities and equipment | Presence and organisation of quality monitoring | Other |

| Ament22 | ● | ● | ● | |||||

| Benenson23 | ● | ● | ● | Standard antibiotic order sheet | ||||

| Cates24 | Evidence-based patient handout | |||||||

| Enriquez-Puga,25 antidepressant prescription guideline | ||||||||

| Enriquez-Puga,25 antibiotic prescription guideline | ||||||||

| Forsner,26 depression guideline | ● | |||||||

| Forsner,26 suicidal behaviours guideline | ● | |||||||

| Gerber35 | ||||||||

| Higuchi,27 Adult Asthma Care Best Practice Guideline | New documentation procedures | |||||||

| Higuchi,27 Reducing Foot Complications for People with Diabetes Best Practice Guideline | New documentation procedures | |||||||

| Kelly28* | ||||||||

| Knops29 fluid balance guideline for oncology patients* | ||||||||

| Knops29 body temperature guideline for postoperative patients | ||||||||

| Loszadi30 | ||||||||

| McLaws31 | ● | ● | ||||||

| Stéphan32 | ||||||||

| Wakefield33 | ● | |||||||

| Williams34 | ● | |||||||

*No information about the implementation strategy provided.

● Item explicitly stated in one of the related articles of the study.

Characteristics of the sustainability evaluations

The mean timeframe between the end of the implementation strategy and the sustainability evaluation of 13 studies was 2.6 years (minimum 1.5–maximum 7.0). The actual timeframe of one evaluation was unclear, but was at least 2 years.30 Two studies referred to a definition of sustainability.22 27 Eight studies used a retrospective data collection method,23–29 33 three studies used a prospective data collection method31 32 35 and three studies used both a prospective and a retrospective data collection method.22 30 34 Ten papers reported the level of sustained adherence of a single clinical practice guideline,22–24 28 30–35 while four reported the late postimplementation adherence of two clinical practice guidelines.25–27 29 Seven studies had a single-centre design23 28–30 32–34 and seven studies evaluated sustainability in multiple centres.22 24–27 31 35 Four out of six multiple centre studies evaluated the sustainability on multiple centre level.22 26 31 35 Two out of six multiple centre studies evaluated the sustainability of professionals’ adherence of two guidelines which were implemented in one centre each.24 27

Sustainability of changed behaviour

The level of professionals’ adherence was fully sustained in 7 out of 18 evaluations (table 3, see online supplementary file 3). The adherence was not fully sustained in six evaluations, and four evaluations showed mixed sustainability results in the LATE POST measurement compared with the EARLY POST measurement. In one study, the EARLY POST measurement was not executed, while the authors reported sustained results.28 After decreasing the sustainability level of professionals’ adherence to 90% or higher, 9 out of 18 evaluations showed sustained results, 3 evaluations showed no sustained results, 4 evaluations showed mixed results. In two evaluations, it was unclear whether the professionals’ adherence had been sustained at a level 90% or higher.

Table 3.

Sustainability of professionals’ adherence to clinical practice guidelines

| Study ID | Authors’ comments in terms of sustainability of adherence to the clinical practice guideline* | Sustained compared with early implementation results (100%) (yes/no)† | Sustained compared with early implementation results (90%) (yes/no)‡ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ament et al22 | “Adherence to the guideline recommendations was sustained in four early adopter hospitals” | Yes | Yes |

| Benenson et al23 | “The observed pre pathway to post pathway differences were sustained over three years” | Yes | Yes |

| Cates24 | (Centre 1 and 2) “our approach has brought about a sustained reduction in the use of antibiotics for children with acute otitis media, and after dissemination of our findings, similar results have been replicated at centre II using deferred prescribing of antibiotics for children who are not unduly ill” | Yes | Yes |

| Enriquez-Puga et al25 | “There was a small change in the desired direction in the proportion of antidepressants prescribed according to guidelines that lasted for 24 months, although no change for antibiotics. A simple, group level educational outreach intervention, designed to take account of identified barriers to change, appears to have a small sustained effect on prescribing levels, but the effect is not consistent across different groups of drugs” | Guideline 1: no Guideline 2: yes |

Guideline 1: no Guideline 2: yes |

| Forsner et al26 | “This study suggested that the compliance to clinical guidelines, for treatment of depression and suicidal behaviour, was implemented and sustained over a two-year period after an active implementation” | Guideline 1: mixed Guideline 2: mixed |

Guideline 1: mixed Guideline 2: mixed |

| Gerber et al35 | Not mentioned | No | No |

| Higuchi et al27 | (1) “The chart audit revealed that eleven nursing care indicators related to the asthma guideline recommendations showed a mixed pattern of sustainability” (2) Not mentioned |

Guideline 1: mixed Guideline 2: mixed |

Guideline 1: mixed Guideline 2: mixed |

| Kelly28 | “The study demonstrated a significant and sustained change in analgesia administration practices away from the intramuscular (IM) route in favour of the IV route” | NA | NA |

| Knops et al29 | (1) Not mentioned (2) Not mentioned |

Guideline 1: yes Guideline 2: no |

Guideline 1: yes Guideline 2: no |

| Loszadi et al30 | Not mentioned | Yes | Yes |

| McLaws et al31 | Not mentioned | No | Yes |

| Stéphan et al32 | “One of the most important results of our intervention is its sustained impact. In particular, the frequency of catheter use decreased in the operating room not only immediately after guideline implementation, but also could be observed 2 years later” | No | Yes |

| Wakefield et al33 | Not mentioned | No | Na |

| Williams et al34 | Not mentioned | Yes | yes |

*Citations of the authors of reviewed papers about the sustainability of adherence to the clinical practice guideline. †The same level or improved professionals’ adherence was achieved years after implementation compared with early postimplementation results (yes/no). ‡At least 90% of professionals’ adherence was achieved years after implementation, compared with early postimplementation results (yes/no).

Mixed, the overall professionals’ adherence was not presented, and both sustained and not sustained levels of professionals’ adherence to clinical practice guideline recommendations were achieved in the late post-implementation phase compared to early post-implementation results; NA, not applicable as the early post-implementation results were not measured.

Five of the 10 papers that reported about a single clinical practice guideline presented sustained professionals’ adherence to clinical practice guidelines in the LATE POST measurement.22–24 30 34 One of these five papers evaluated the sustainability of a single clinical practice guideline in two centres.24 In both centres, professionals’ adherence had improved in the LATE POST measurement compared with the EARLY POST measurement. The four studies analysing the sustainability of two clinical practice guidelines showed mixed results. Two of these four studies25 29 presented the same level or improved adherence to one guideline and decreased adherence to the other guideline in the LATE POST measurement compared with the EARLY POST measurement. The other two of these four studies26 27 presented adherence results on guideline recommendation level and did not present overall adherence results on patient level. The adherence to the recommendations of the clinical practice guidelines showed decreased and improved levels in the LATE POST measurement compared with the EARLY POST measurement. In total, eight papers mentioned the term ‘sustainability’ in the conclusion (table 3).22–28 32 Five of these studies concluded to have sustained professionals’ adherence in the late postimplementation phase,22–24 28 32 three out of eight studies described to have a ‘mixed pattern’, ‘small desired’ or ‘almost’ sustained professionals’ adherence.25–27

Risk of bias in included studies

All studies included in the present review had a high risk of bias, following the Downs and Black assessment tool20 (table 4, see online supplementary file 4).

Table 4.

Results of the risk of bias assessment

| Study ID | Reporting | External validity | Internal validity—bias | Internal validity— confounding | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ament et al22 | Unclear | High | High | High | High |

| Benenson et al23 | Unclear | High | High | High | High |

| Cates24 | High | Unclear | High | High | High |

| Enriquez-Puga et al25 | Unclear | High | High | Unclear | High |

| Forsner et al26 | Unclear | Low | High | High | High |

| Gerber et al35 | Low | Low | High | High | High |

| Higuchi et al27 | High | High | High | High | High |

| Kelly28 | High | High | High | High | High |

| Knops et al29 | High | Low | High | High | High |

| Loszadi et al30 | Unclear | High | Unclear | High | High |

| McLaws et al31 | High | Low | Unclear | High | High |

| Stéphan et al32 | High | High | Unclear | High | High |

| Wakefield et al33 | High | High | High | High | High |

| Williams et al34 | High | High | Unclear | High | High |

| Total | High | High | High | High | High |

Discussion

Our review focused on the level of sustainability of implementation success in terms of professionals’ adherence. Also, this systematic review described the state of the art in sustainability research. This systematic review identified 14 studies, including 18 evaluations that investigated the sustainability of professionals’ adherence to a clinical practice guideline more than 1 year after the implementation was finished. Of 18 analyses that focused on the extent of sustained professionals’ adherence to a clinical practice guideline, seven analyses revealed fully sustained results. After decreasing the sustainability level of professionals’ adherence to 90% or higher, 9 out of 18 evaluations showed sustained results. The current review showed that the number of sustainability studies is scarce and that the studies are heterogeneous with respect to their methodology. Furthermore, almost no study analysed or reflected on the updates of the guideline in the postimplementation phase. The results of this review suggest that updates of the clinical practice guidelines may have led to a warranted decrease in the adherence to the original clinical practice guideline.

In this systematic review, information was presented about how to search for sustainability evaluations, how sustainability research is defined and about the type and the methodological quality of studies that report on sustainability. As was confirmed in another systematic review,10 the sustainability studies showed to have limited methodological rigour. Two out of 14 studies used an experimental design. The lack of identified studies in the current review suggests that most teams do not focus on the long-term performance effect of quality improvements.64 Owing to the limited number of studies focusing on this subject, the heterogeneity in studies, suboptimal reporting by authors and the revealed methodological weaknesses, no strong conclusions can be drawn based on the presented sustainability results. As also shown in other research, most sustainability studies used a single-case study design by focusing on a single type of programme or performed the evaluation at a single centre level.65 The current review showed that in only two of the studies, a reference for the definition of sustainability was used. Other studies performed a sustainability evaluation without mentioning a definition. This shows the underdeveloped field of sustainability research. Also, a variety of timeframes to study the sustainability of professionals’ adherence to clinical practice guidelines was revealed, varying from 1½ to 7 years following implementation.

Optimal adherence to a clinical practice guideline as determined during implementation is not always desired; for example, clinical experience and evidence may change. This systematic review included all research designs and seems to be the first review with respect to sustainability of professionals’ adherence to clinical practice guidelines to date. Other reviews focused on healthcare from a broad perspective including multiple healthcare fields10 or reviewed studies performed specifically in public health.6 9 The sustainability of a health programme in public health may be influenced by other determinants than the sustainability of a clinical practice guideline in medical care. Also, the concept of the sustainability may differ between healthcare fields. For example, in public health sustainability of a health programme may be successfully sustained if health outcomes, for example, changed lifestyle, are maintained and financial support is still available.6 65 In medical care, the primary focus is on the quality and safety of care which is supposed to be captured in clinical practice guidelines. Owing to the specific focus on clinical practice guidelines in the current review, mainly other studies were included compared with the existing sustainability reviews.6–10 14

Strengths and weaknesses

As yet, the term ‘sustainability’ is not consistently used for this area in the broader medical field, which presents a limitation to the electronic search strategy. The topic is not well indexed in electronic databases, and text word searches are prone to high recall and low specificity. However, it is likely that the use of a broad variety of search terms that covered sustainability has downsized the number of relevant studies missed and is a strength of the review.

In this systematic review, sustainability was assessed as successful if performance in terms of professionals’ adherence was fully maintained in the late postimplementation phase. This definition of sustainability may be too pragmatic as it could be undesirable to fully sustain the professionals’ adherence in the late postimplementation phase. Therefore, a sensitivity analysis was performed to analyse the sustainability at a level of 90% or higher. However, as mentioned before, a limitation of the review is the high risk of bias of all studies included. The majority of the studies used a retrospective data collection method. Nevertheless, results were interpreted under consideration of risk of bias, and the assessments were also used for recommendations for further research by identifying elements of studies that can be improved in new studies. Also, the question is what the best method is for evaluating sustainability. For example, retrospective data may be desired to prevent a Hawthorne effect when studying routine practice.

The results of the current review show more studies with sustained professionals’ adherence than might be expected without continuing efforts and support to promote the level of sustained adherence in the postimplementation phase. Possibly, studies with unfavourable results may not be published or unsuccessful implementation projects may not be evaluated, leading to an under-representation of the true amount of work carried out in the field.66 67

Sustainability of professionals’ adherence may be influenced by the perceived quality of the guideline. However, we were not able to analyse the quality of the guidelines given the limited information in the manuscripts and the information on the internet on the specific guidelines. More information about the quality of the guidelines in sustainability evaluations may be helpful to analyse the sustainability of the guideline. Also, the potential effect of the specific implementation strategies was not analysed as part of the systematic review. Professionals’ adherence is an outcome measure used in implementation science, and it captures the behaviour change as a result of implementation strategies. The type of implementation strategy may have had an effect on the sustainability of the implementation results. The studies included used various implementation strategies and implemented different clinical practice guidelines.

Implications for practice

The current review showed that the level of the sustainability of professionals’ adherence to clinical practice guidelines varies on case study level and drops in more than half of the studies. Owing to the lack of sustainability research we think that sustainability failure as presented in this study is an underestimation. Unfortunately, implementation projects are primarily focused on short-term actions and short-term effect.64

Future research

This review complements the existing sustainability research by focusing on sustained professionals’ adherence in medical practice. The current review showed that not many studies reported data on the sustainability of professionals’ adherence to clinical practice guidelines. Also, no strong conclusions can be drawn due to the high risk for bias and the heterogeneity of the studies. As shown in previous research, structural methods for sustainability evaluations are lacking.10 68 Furthermore, future implementation and sustainability evaluations may include information about the quality of the clinical practice guideline, such as described in the AGREE instrument.69 More sustainability evaluation research and methodological guidance is needed to make future sustainability research more robust and generalisable and may be helpful in creating a general sustainability language.

Conclusion

This systematic review identified, reported and analysed studies that evaluated the level of sustainability of professionals’ adherence to guideline recommendations in medical practice more than 1 year following the cessation of the implementation project.2 Seven out of 18 evaluations showed sustained professionals’ adherence on average 2.6 years after implementation.1 Owing to the limited number and the lack of methodological quality of the identified studies, no firm conclusion about the sustainability of professionals’ adherence to guideline recommendations in medical practice can be drawn. More sustainability evaluations, methodological sustainability studies and reviews are needed in order to develop a general framework for sustainability measurement and to facilitate uniform language and communication within the sustainability science.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Karin Vaessen for the assistance in retrieving full-text papers.

Footnotes

Twitter: Follow Stephanie Ament at @stephanieament

Contributors: All authors made substantial contributions to conception and design, analysis and interpretation of data. SMCA and JJAdG were responsible for the data collection, supervised by JMCM, CDD, TvdW and JK. SMCA was responsible for the draft of the manuscript and all authors were also involved in editing the manuscript. All authors have given final approval of the version to be published. All authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. SMCA is guarantor.

Funding: This work is produced by SMCA under the terms of a doctoral research training fellowship issued by ZonMw, the Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development (grant number 171103004).

Competing interests: All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interests form at http://www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author). SMCA is a health scientist, main investigator and PhD candidate. JJAdG is a medical doctor and PhD candidate. TvdW is professor implementation of evidence in healthcare. SMCA, JJAdG and TvdW are employed by Maastricht University. JMCM is senior research associate at Maastricht University Medical Centre. CDD is professor health technology assessment of clinical interventions at Maastricht University Medical Centre. JK is professor of systematic reviews in healthcare at Maastricht University and founded Kleijnen Systematic Reviews (KSR) Ltd in 2005. KSR is an independent research company that produces and disseminates systematic reviews, cost-effectiveness analyses and health technology assessments of research evidence in healthcare. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Additional data can be accessed via the Dryad data repository at http://datadryad.org/ with the doi:10.5061/dryad.cr020.

References

- 1.Graham R, Mancher M,, Wolman DM et al. Clinical practice guidelines we can trust. Washington DC: National Academies Press, 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thomas LH, McColl E, Cullum N et al. Effect of clinical guidelines in nursing, midwifery, and the therapies: a systematic review of evaluations. Qual Health Care 1998;7:183–91. 10.1136/qshc.7.4.183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grimshaw JM, Thomas RE, MacLennan G et al. Effectiveness and efficiency of guideline dissemination and implementation strategies. Health Technol Assess 2004;8:iii–iv, 1–72 10.3310/hta8060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Processes 1991;50:179–211. 10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pluye P, Potvin L, Denis JL et al. Program sustainability: focus on organizational routines. Health Promot Int 2004;19:489–500. 10.1093/heapro/dah411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gruen RL, Elliott JH, Nolan ML et al. Sustainability science: an integrated approach for health-programme planning. Lancet 2008;372:1579–89. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61659-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Greenhalgh T, Robert G, Macfarlane F et al. Diffusion of innovations in service organizations: systematic review and recommendations. Milbank Q 2004;82:581–629. 10.1111/j.0887-378X.2004.00325.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shediac-Rizkallah MC, Bone LR. Planning for the sustainability of community-based health programs: conceptual frameworks and future directions for research, practice and policy. Health Educ Res 1998;13:87–108. 10.1093/her/13.1.87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scheirer MA. Is sustainability possible? A review and commentary on empirical studies of program sustainability. Am J Eval 2005;26:320–47. 10.1177/1098214005278752 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wiltsey Stirman S, Kimberly J, Cook N et al. The sustainability of new programs and innovations: a review of the empirical literature and recommendations for future research. Implement Sci 2012;7:17 10.1186/1748-5908-7-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.NHS. Sustainability and its relationship with spread and adoption. Coventry, 2007. http://www.clahrc-northwestlondon.nihr.ac.uk/inc/files/documents/improvement-methodology-resources-section/ilg_1.7_substainability_and_its_relationship_with_spread_and_adoption.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ament SM, Gillissen F, Maessen JM et al. Sustainability of healthcare innovations (SUSHI): long term effects of two implemented surgical care programmes (protocol). BMC Health Serv Res 2012;12:423 10.1186/1472-6963-12-423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adams AS, Soumerai SB, Lomas J et al. Evidence of self-report bias in assessing adherence to guidelines. Int J Qual Health Care 1999;11:187–92. 10.1093/intqhc/11.3.187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buchanan D, Fitzgerald L, Ketley D et al. No going back: a review of the literature on sustaining organizational change. Int J Manag Rev 2005;7:189–205. 10.1111/j.1468-2370.2005.00111.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fleiszer AR, Semenic SE, Ritchie JA et al. The sustainability of healthcare innovations: a concept analysis. J Adv Nurs 2015;71:1484–98. 10.1111/jan.12633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Proctor E, Luke D, Calhoun A et al. Sustainability of evidence-based healthcare: research agenda, methodological advances, and infrastructure support. Implement Sci 2015;10:88 10.1186/s13012-015-0274-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chambers D, Glasgow R, Stange K. The dynamic sustainability framework: addressing the paradox of sustainment amid ongoing change. Implement Sci 2013;8:117 10.1186/1748-5908-8-117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ilott I, Gerrish K, Pownall S et al. Exploring scale-up, spread, and sustainability: an instrumental case study tracing an innovation to enhance dysphagia care. Implement Sci 2013;8:128 10.1186/1748-5908-8-128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Review Group. Data collection checklist. University of Ottawa, Institute of Population Health, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Downs SH, Black N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health 1998;52:377–84. 10.1136/jech.52.6.377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000097 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ament SM, Gillissen F, Maessen JM et al. Sustainability of short stay after breast cancer surgery in early adopter hospitals. Breast 2014;23:429–34. 10.1016/j.breast.2014.02.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Benenson R, Magalski A, Cavanaugh S et al. Effects of a pneumonia clinical pathway on time to antibiotic treatment, length of stay, and mortality. Acad Emerg Med 1999;6:1243–8. 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1999.tb00140.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cates CJ. Delayed antibiotics for children with acute otitis media: Is practice change sustainable? Evid Based Med 2009;14:2–3. 10.1136/ebm.14.1.2-a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Enriquez-Puga A, Baker R, Paul S et al. Effect of educational outreach on general practice prescribing of antibiotics and antidepressants: a two-year randomised controlled trial. Scand J Prim Health Care 2009;27:195–201. 10.3109/02813430903226530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Forsner T, Wistedt A, Brommels M et al. Supported local implementation of clinical guidelines in psychiatry: a two-year follow-up. Implement Sci 2010;5:4 10.1186/1748-5908-5-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Higuchi KS, Davies BL, Edwards N et al. Implementation of clinical guidelines for adults with asthma and diabetes: a three-year follow-up evaluation of nursing care. J Clin Nurs 2011;20:1329–38. 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03590.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kelly A-M. Nurse-managed analgesia for renal colic pain in the emergency department. Aust Health Rev 2000;23:185–9. 10.1071/AH000185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Knops AM, Storm-Versloot MN, Mank APM et al. Factors influencing long-term adherence to two previously implemented hospital guidelines. Int J Qual Health Care 2010;22:421–9. 10.1093/intqhc/mzq038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lozsadi DA, Peters G, Sadik HY et al. Prevention of osteoporosis in glucocorticoid-treated neurology patients. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 2006;108:157–62. 10.1016/j.clineuro.2005.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McLaws ML, Pantle AC, Fitzpatrick KR et al. Improvements in hand hygiene across New South Wales public hospitals: clean hands save lives, part III. Med J Aust 2009;191(8 Suppl.):S18–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stéphan F, Sax H, Wachsmuth M et al. Reduction of urinary tract infection and antibiotic use after surgery: a controlled, prospective, before-after intervention study. Clin Infect Dis 2006;42:1544–51. 10.1086/503837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wakefield B, Johnson JA, Kron-Chalupa J et al. A research-based guideline for appropriate use of transdermal fentanyl to treat chronic pain. Oncol Nurs Forum 1998;25:1505–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Williams A, Adams EJ, Bolderson J et al. Effect of a new guideline on outcome following third-degree perineal tears: results of a 3-year audit. Int Urogynecol J 2003;14:385–9. 10.1007/s00192-003-1091-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gerber JS, Prasad PA, Fiks AG et al. DUrability of benefits of an outpatient antimicrobial stewardship intervention after discontinuation of audit and feedback. JAMA 2014;312:2569–70. 10.1001/jama.2014.14042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.de Kok M. Costs and effects of implementation of a short admission programme following breast cancer surgery in the Netherlands. Rotterdam: Maastricht University, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ament SMC, De Kok M., Van de Velde CJH, Roukema JA, Bell AVRJ, Van der Ent FW, Van der Weijden T, Von Meyenfeldt MF, Dirksen CD. Calculating implementation costs using a structured method: implementation of a short stay programme for breast cancer surgery. Implementation Science 2015;10:78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Mank A, Semin-Goossens A, Lelie J et al. Monitoring hyperhydration during high-dose chemotherapy: body weight or fluid balance? Acta Haematol 2003;109:163–8. doi:70964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Storm-Versloot MN, Knops AM, Ubbink DT et al. Long-term adherence to a local guideline on postoperative body temperature measurement: mixed methods analysis. J Eval Clin Pract 2012;18:841–7. 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2011.01687.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pantle AC, Fitzpatrick KR, McLaws ML et al. A statewide approach to systematising hand hygiene behaviour in hospitals: clean hands save lives, part I. Med J Aust 2009;191(8 Suppl.):S8–S12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gerber JS, Prasad PA, Fiks AG et al. Effect of an outpatient antimicrobial stewardship intervention on broad-spectrum antibiotic prescribing by primary care pediatricians: a randomized trial. JAMA 2013;309:2345–52. 10.1001/jama.2013.6287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nationaal Borstkanker Overleg Nederland. NABON-Nota, Handboek organisatie mammazorg Amsterdam 2008. http://www.oncoline.nl/uploaded/docs/mammacarcinoom/NABON nota 2008.pdf

- 43.Nationaal Borstkanker Overleg Nederland. Richtlijn Mammacarcinoom, landelijke richtlijn 2012. http://www.heelkunde.nl/uploads/_a/Gk/_aGkhzjRsgiYhbhbFWFETQ/Mammacarcinoom2012.pdf

- 44.Niederman MS, Bass JB Jr, Campbell GD et al. Guidelines for the initial management of adults with community-acquired pneumonia: diagnosis, assessment of severity, and initial antimicrobial therapy. American Thoracic Society. Medical Section of the American Lung Association. Am Rev Respir Dis 1993;148:1418–26. 10.1164/ajrccm/148.5.1418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Niederman MS, Mandell LA, Anzueto A et al. Guidelines for the management of adults with community-acquired pneumonia. Diagnosis, assessment of severity, antimicrobial therapy, and prevention. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001;163:1730–54. 10.1164/ajrccm.163.7.at1010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mandell LA, Wunderink RG, Anzueto A et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society consensus guidelines on the management of community-acquired pneumonia in adults. Clin Infect Dis 2007;44(Suppl. 2):S27–72. 10.1086/511159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Centre for Clinical Practice at NICE (UK). Respiratory tract infections. Antibiotic prescribing: prescribing of antibiotics for self-limiting respiratory tract infections in adults and children in primary care. London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (UK), 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Medicinskt programarbete Regionalt vårdprogram. Vård av suicidnära patienter. Stockholm County Council, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Leicestershire Health Authority. Leicestershire evidence based guidelines for the management of major depression. Leicestershire, 2000.

- 50.Health Protection Agency. Management of infection guidance for primary care for consultation and local adaptation. London: HPA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 51. National Institue for health and care excellence (NICE). Depression in adults: The treatment and management of depression in adults. London, 2004. [PubMed]

- 52.Medicinskt programarbete. Regionalt vårdprogram för depressionssjukdomar inkl. mano-depressiv sjukdom. Stockholm Stockholm County Council, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bradley JS, Byington CL, Shah SS et al. The management of community-acquired pneumonia in infants and children older than 3 months of age: clinical practice guidelines by the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society and the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2011;53:e25–76. 10.1093/cid/cir531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Registered Nurses' Association of Ontario, RNAO. Adult asthma care guidelines for nurses: promoting control of asthma. Toronto: 2002a. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Registered Nurses' Association of Ontario, RNAO. Reducing Foot Complications for People with Diabetes. Toronto: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario, RNAO. Adult Asthma Care Guidelines for Nurses: Promoting Control of Asthma Toronto2004 [updated February 2007]. http://rnao.ca/sites/rnao-ca/files/Adult_Asthma_Care_Guidelines_for_Nurses_-_Promoting_Control_of_Asthma.pdf

- 57.Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario, RNAO. Reducing Foot Complications for people with Diabetes Toronto2004 [updated 2007]. http://rnao.ca/sites/rnao-ca/files/Foot_Compl_Diabetes_Updated.pdf.

- 58.Acute pain management guideline panel. Acute pain management: operative or medical procedures and trauma: clinical practice guideline. Washington DC: US Department of Health and Human Services, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Vermeulen H, Storm-Versloot MN, Goossens A et al. Diagnostic accuracy of routine postoperative body temperature measurements. Clin Infect Dis 2005;40:1404–10. 10.1086/429621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.National Osteoporosis Society. Guidance on the prevention and management of corticosteroid induced osteoporosis. Bath: NOS, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 61.World Health Organization, WHO. Guidelines on hand hygiene in health care (advanced draft): a summary. Clean hands are safer hands. Geneva: WHO, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 62. Norton JA, Bollinger RR, Chang A, Lowry SF. Surgery: basic science and clinical evidence. 2nd ed. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Malouf AJ, Norton CS, Engel AF et al. Long-term results of overlapping anterior anal-sphincter repair for obstetric trauma. Lancet 2000;355:260–5. 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)05218-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.ØVretveit J, Bate P, Cleary P et al. Quality collaboratives: lessons from research. Qual Saf Health Care 2002;11:345–51. 10.1136/qhc.11.4.345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Schell S, Luke D, Schooley M et al. Public health program capacity for sustainability: a new framework. Implement Sci 2013;8:15 10.1186/1748-5908-8-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hopewell S, Loudon K, Clarke MJ et al. Publication bias in clinical trials due to statistical significance or direction of trial results. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009;(1):MR000006 10.1002/14651858.MR000006.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Easterbrook PJ, Berlin JA, Gopalan R et al. Publication bias in clinical research. Lancet 1991;337:867–72. 10.1016/0140-6736(91)90201-Y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tricco AC, Cogo E, Ashoor H et al. Sustainability of knowledge translation interventions in healthcare decision-making: protocol for a scoping review. BMJ Open 2013;3:pii: e002970 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-002970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.AGREE Collaboration. Development and validation of an international appraisal instrument for assessing the quality of clinical practice guidelines: the AGREE project. Qual Saf Health Care 2003;12:18–23. 10.1136/qhc.12.1.18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]