Abstract

Objectives

To estimate the incidence and risk factors for gastroenteritis-related hospitalisations in older adults.

Design

Longitudinal cohort study.

Participants

The 45 and Up Study is a large-scale Australian prospective study of adults aged ≥45 years (mean 62.7 years) at recruitment in 2006–2009. Self-reported demographic, health and dietary information at recruitment from 265 440 participants were linked to infectious gastroenteritis hospitalisation data.

Outcome measures

We estimated the incidence of hospitalisation for infectious gastroenteritis, and calculated HRs using Cox regression, adjusting for sociodemographic, health and behavioural variables, with age as the underlying time variable.

Results

There were 6077 incident infectious gastroenteritis admissions over 1 111 000 person-years. Incidence increased exponentially with increasing age; from 2.4 per 1000 (95% CI 2.2 to 2.5) in individuals aged 45–54 years to 9.5 per 1000 (95% CI 9.2 to 9.8) in those aged 65+ years. After adjustment, hospitalisation due to infectious gastroenteritis was significantly more common in those reporting use of proton pump inhibitors (HR 1.6, 95% CI 1.5 to 1.7), and those with poorer self-rated health (HR 4.2, 95% CI 3.6 to 4.9).

Conclusions

Infectious gastroenteritis results in hospitalisation of approximately 1% of people ≥65 years old each year. Early recognition and supportive treatment of diarrhoea in older patients with poorer self-rated health may prevent subsequent hospitalisation.

Keywords: INFECTIOUS DISEASES

Strengths and limitations of this study.

A large population-based cohort study examining risk factors for hospitalisation due to gastroenteritis, with record linkage to multiple databases.

Prospectively collected data on a range of potential risk factors and confounders, allowing analysis of multiple variables.

Self-reported exposure assessment at the recruitment.

Introduction

Gastroenteritis is one of the most common infectious diseases among humans and is a major cause of mortality in low-income and middle-income countries, particularly among children aged <5 years.1 By contrast, the highest rates of mortality due to gastroenteritis in high-income countries occur in the elderly,2 particularly people aged ≥75 years.3 The elderly are potentially at higher risk of some enteric infections, due to decreased gastric acidity, intestinal motility disorders, and a compromised immune system.4 5 Despite this, the incidence of gastroenteritis in the elderly living in the community is lowest of any age group, with one Australian study estimating the incidence of people ≥65 years old at 0.33 (95% CI 0.24 to 0.42) episodes per person per year.6

However, older people may experience more severe symptoms and be more likely to require hospitalisation than younger people.6 In Australia, people aged ≥65 years old were hospitalised with all-cause gastroenteritis at a rate of 20.2 per 1000 population annually between 2009 and 2010.7 In the USA, hospitalisation due to all-cause gastroenteritis increased by ≥50% in all adults and elder age groups between 1996 and 2007, with norovirus estimated to be a significant contributor to the high rates among the elderly.8 Furthermore, the total healthcare costs for gastroenteritis requiring hospitalisation are three times higher per adult patient compared with a child, due to increasing length of hospital stay and more common presentation with severe symptoms and complications.9

Hospitalisation due to infectious gastroenteritis imposes a significant burden on the health system in industrialised countries.10 However, risk factors among older adults have not been well described. In this study, our objective was to estimate age-specific rates of hospitalisation due to infectious gastroenteritis, along with risk factors, in a large cohort of Australian adults.

Method

Study population

The Sax Institute's 45 and Up Study is a population-based cohort which recruited over 267 000 residents in the Australian state of New South Wales (NSW) who were aged 45 years and over between January 2006 and December 2008. Details of the study methods are published elsewhere.11 Study participants were randomly selected from the national health insurance database (Medicare), and there was oversampling of those living in rural regions and those aged over 80 years. Participants completed a questionnaire at recruitment where they provided information on sociodemographics, lifestyle, dietary habits and their health (see https://www.saxinstitute.org.au/our-work/45-up-study/questionnaires/), and agreed to have their data linked to other administrative health records.

Questionnaire data from study participants were linked to the NSW Admitted Patient Data Collection (APDC) to identify hospitalisations due to infectious gastroenteritis, and the NSW Register of Births, Deaths and Marriages (RBDM) for deaths. The NSW APDC records demographic and episode-related information for all patient admissions to NSW hospitals, and includes the principal diagnosis responsible for the admission, up to 54 additional diagnoses contributing to the admission, and the date of admission. Clinical information is coded using the International Classification of Disease V.10 Australian modification (ICD-10-AM).12 The NSW RBDM includes a record of all deaths in NSW and the date of death. Information on cause of death was not available at the time of analysis. We had complete APDC and RBDM records until 30 June 2012. The 45 and Up Study participant data, APDC and RBDM were linked independently of the study investigators by the NSW Centre for Health Record Linkage using personal information such as name, date of birth and sex, with false-positive and false-negative rates of <0.5% and <0.1%, respectively.13

Case definition

Participants were defined as having an incident hospitalisation with infectious gastroenteritis if they had a linked APDC record where the principal or a secondary diagnosis was coded with an ICD-10-AM code for either diarrhoea of determined aetiology-bacterial (A00-A05), parasitic (A06-A07), viral (A08) or undetermined aetiology-presumed infectious disease (A09), and the admission occurred following recruitment.

A gastroenteritis complication was defined if cases also had coded in their linked APDC record either fluid, electrolyte and acid–base disorders (ICD-10-AM E87 excluding fluid overload E87.7); shock (R57, excluding cardiogenic shock R57.0) or septicaemia (A41.9).

Statistical analysis

Participants who had a linked hospitalisation record for gastroenteritis in the 30 days prior to recruitment were excluded, as we wanted to exclude the possibility that any admissions due to gastroenteritis immediately following recruitment may be part of that same episode. To minimise the impact of pre-existing illness that may predispose individuals to infectious gastroenteritis, participants were also excluded if they had a linked hospitalisation record with a principal diagnosis code for any of the following: chronic bowel problems (non-infective enteritis and colitis K50-K52, irritable bowel syndrome K58), immunosuppressive disorders (D80-D89), or cancer (C00-C97) in the 5 years prior to study entry. Follow-up was calculated from the date of recruitment to the first date of admission for gastroenteritis, death or the end of database follow-up (30 June 2012), whichever came first. Incident gastroenteritis hospitalisation rates were calculated according to age (45–54, 55–64, 65–74, 75–84 or ≥85 years), sex, annual household income (<$A20 000, $A20 000–$A29 999, $A30 000–$A39 999, $A40 000–$A49 999, $A50 000–$A69 999, $A70 000 or more per year, or unknown), and region of residence (cities, inner regional or outer regional/remote/very remote) based on the Accessibility/Remoteness Index of Australia.14

HRs for hospitalisations due to gastroenteritis by sociodemographic, behavioural and health status variables were estimated using Cox proportional hazards models with age as the underlying time variable.15 Regression models were adjusted for attained age (as this was the underlying time variable) and sex. Models were then adjusted for additional variables, including annual household income, region of residence, education (3 categories: university degree or higher, no university degree, or unknown), health status variables including self-rated health (excellent, very good, good, fair, poor or unknown), and body mass index (BMI: underweight (<18.5 kg/m2), normal (18.5–24.99 kg/m2), overweight (25–29.99 kg/m2), obese (≥30 kg/m2) or unknown), smoking (current, past, never or unknown), alcohol (none, 1–2 alcoholic drinks per day, >2 alcoholic drinks per day or unknown) and factors which have been previously identified as risk factors for gastroenteritis, including living in aged care facilities (yes, no or unknown), proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) usage (yes, no), frequency of chicken/poultry intake (none, at least once per week or unknown), frequency of seafood intake (none, at least once per week or unknown), egg consumption (ever, never), and fruit and vegetable intake (low, adequate or unknown). Fruit and vegetable intake was categorised as ‘low’ if fruit intake was less than two servings daily, or vegetable intake was less than five servings daily, and ‘adequate’ if fruit intake was at least two servings daily and vegetable intake at least five servings daily. Participants were classified as using PPIs if they answered yes to the question ‘Have you taken any medications, vitamins or supplements for most of the last 4 weeks?’, and crossed out either ‘Nexium’, ‘Somac’ or ‘Losec, Acimax omeprazole’ in the baseline questionnaire. Participants were classified as not using PPIs if they answered ‘no’ to the above question, or answered ‘yes’ to the above question but did not cross out any one of the above medications.

Missing values for variables were coded as separate categories in the model. The proportionality assumption was examined by plotting the Schoenfeld residuals against the time variable in each model.16 Where this assumption was violated, we stratified exposure variables and compared findings under the two models. Sensitivity analyses were conducted by defining cases as only those with a principal hospital diagnosis of infectious gastroenteritis, and also including participants with a hospitalisation for chronic bowel problems, immunosuppressive disorders and cancer as a principal diagnosis, before recruitment. All analyses were carried out using STATA V.12.1.

Result

After excluding participants with a linked infectious gastroenteritis hospitalisation record 30 days prior to recruitment (n=45), participants with prior hospitalisations for specific illnesses associated with hospitalisations due to gastroenteritis (n=706), and confirmed linkage errors (n=44), there were 265 440 participants in the analysis, yielding a total of 1 111 223 years of follow-up (median 3.9 years per person). The mean age of study participants at recruitment was 62.7 years (SD 11.2), and 53.6% were women.

There were 6077 (2.3%) participants with at least one linked incident infectious gastroenteritis hospitalisation record during follow-up, of which 53.7% (3261/6077) had infectious gastroenteritis as the primary reason for admission (see online supplementary table S1). Among the 6077 participants with hospitalisation due to incident-infectious gastroenteritis, 58.6% (3560/6077) were referred to the hospital from the emergency department, and 26.8% (1631/6077) from a medical practitioner. The remaining cases were referred from a range of other sources, including community health, residential care and other hospitals. The mean length of hospital stay for the first hospitalisation among those 6077 participants admitted was 7.5 (SD 17.4) days; median length 3 days. Complications of gastroenteritis were reported in 11.0% (667/6077) of the hospitalisations due to gastroenteritis. Both the length of stay and the proportion with complications increased with increasing age (table 1). Among cases, 2.6% (160/6077) of the patients died within 30 days of hospital admission. Participants aged ≥65 years accounted for the majority of these deaths (90.6%, n=145) (table 1).

Table 1.

Proportion of total complications of gastroenteritis, and mean length of hospital stay by age group, 45 and Up Study

| Age group (years) | Complications | Cases | Complications/ cases (%) | Mean length of hospital stay (days) (SD) | Death within 30 days of admission |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 45–54 | 56 | 785 | 7.1 | 4.0 (11.9) | 4 (2.5) |

| 55–64 | 118 | 1347 | 8.8 | 5.8 (15.3) | 11 (6.9) |

| 65–74 | 134 | 1484 | 9.1 | 6.2 (10.2) | 25 (15.6) |

| 75–84 | 260 | 1829 | 14.2 | 9.6 (15.8) | 81 (50.6) |

| ≥85 | 99 | 632 | 15.7 | 12.5 (34.5) | 39 (24.4) |

| Total | 667 | 6077 | 11.0 | 7.5 (17.4) | 160 |

The crude incidence of hospitalisations due to gastroenteritis in the cohort was 5.5 per 1000 person-years (95% CI 5.3 to 5.6), which differed by age, sex, household income and region of residence. Incidence rose from 2.4 hospitalisations per 1000 (95% CI 2.2 to 2.5) person-years in individuals aged 45–54 years to 21.8 per 1000 (95% CI 20.2 to 23.6) in those aged 85+ years (p<0.001 for linear trend) (table 2). The rate of hospitalisations due to gastroenteritis was higher in women than in men (5.8 and 5.0 per 1000 person-years, respectively), but for both sexes, hospitalisation rates increased with decreasing household income (p<0.001). Rates were also greater among those living in cities than in other regions (6.1, 4.9 and 5.1 per 1000 person-years, respectively, in those living in cities, inner regional, outer regional; p=0.01) (table 2).

Table 2.

Crude incidence of hospitalisations due to gastroenteritis by characteristics in mid-age and older adults, the 45 and Up Study

| Characteristics | Population | Cases/person-years | Incidence (95% CI)/1000 person-years | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age group (years) | <0.001 | |||

| 45–54 | 77 669 | 785/332 330 | 2.4 (2.2 to 2.5) | |

| 55–64 | 85 487 | 1347/363 217 | 3.7 (3.5 to 3.9) | |

| 65–74 | 57 678 | 1484/241 404 | 6.1 (5.8 to 6.5) | |

| 75–84 | 36 470 | 1829/145 330 | 12.6 (12.0 to 13.2) | |

| ≥85 | 8136 | 632/28 941 | 21.8 (20.2 to 23.6) | |

| Sex | <0.001 | |||

| Female | 142 313 | 3479/596 317 | 5.8 (5.6 to 6.0) | |

| Male | 123 127 | 2598/514 905 | 5.0 (4.9 to 5.2) | |

| Household income ($A/year) | <0.001 | |||

| <$A20 000 | 52 051 | 1855/214 088 | 8.7 (8.3 to 9.1) | |

| $A20 000–$A29 999 | 25 403 | 655/106 717 | 6.1 (5.7 to 6.6) | |

| $A30 000–$A39 999 | 21 005 | 433/88 693 | 4.9 (4.4 to 5.4) | |

| $A40 000–$A49 999 | 19 156 | 324/80 931 | 4.0 (3.6 to 4.5) | |

| $A50 000–$A69 999 | 27 751 | 397/117 755 | 3.4 (3.1 to 3.7) | |

| $A70 000 or more | 62 605 | 655/263 829 | 2.5 (2.3 to 2.7) | |

| Unknown | 57 469 | 1758/239 205 | 7.4 (7.0 to 7.7) | |

| Region of residence | 0.01 | |||

| Cities | 119 449 | 3012/497 142 | 6.1 (5.8 to 6.3) | |

| Inner regional | 93 299 | 1932/392 057 | 4.9 (4.7 to 5.2) | |

| Outer regional/remote/very remote | 52 692 | 1133/222 023 | 5.1 (4.8 to 5.4) | |

| Total | 265 440 | 6077/1 111 223 | 5.5 (5.3 to 5.6) |

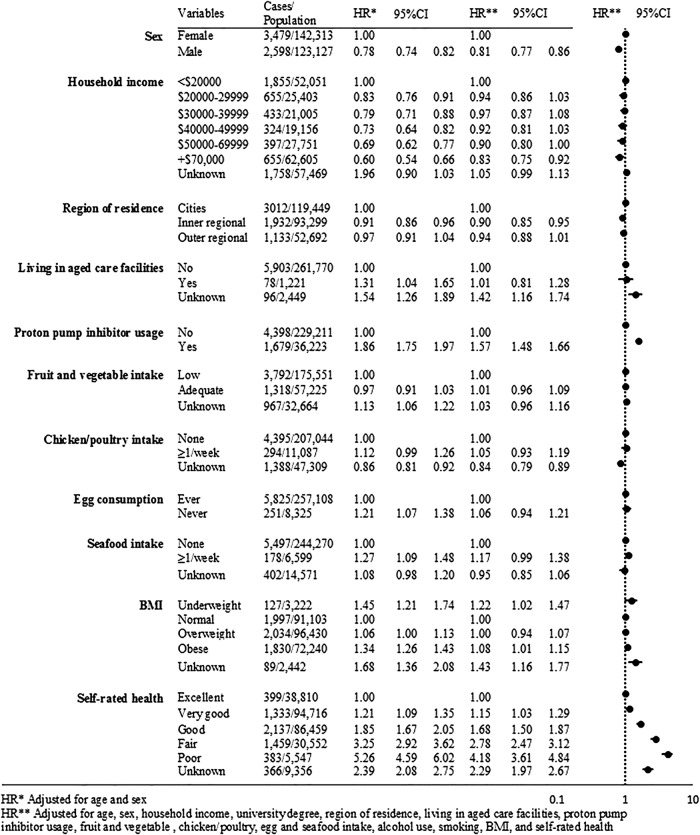

After full adjustment, participant sex, self-rated health, BMI and use of PPIs remained significantly associated with hospitalisation due to gastroenteritis (figure 1). The adjusted HRs (aHR) increased significantly with poorer self-reported health with risks >300% greater for those with poor versus those with excellent health (aHR 4.18, 95% CI 3.61 to 4.84). Hospitalisation due to infectious gastroenteritis was significantly more common in those reporting PPIs use (aHR 1.57, 95% CI 1.48 to 1.66). Compared with participants with a healthy BMI, the risk was significantly higher in the underweight (aHR 1.22, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.47) and the obese (aHR 1.08, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.15). We did not observe significant associations between hospitalisations due to gastroenteritis and food consumption, including fruit and vegetable intake, chicken/poultry intake, egg consumption and seafood consumption (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Associations between various baseline characteristics and incident infectious gastroenteritis hospitalisations, the 45 and Up Study (BMI, body mass index).

Examining PPIs usage, we identified potential concerns with the proportionality assumption, however, a comparison of findings with a stratified version of the variable reassured us that PPIs usage could be included in the final Cox model unaltered (data not shown).

There were 3261 hospitalisations due to gastroenteritis, where a gastrointestinal infection code occurred in the principal hospital diagnosis field (see online supplementary table S1). Overall results were generally similar to the broader definition, with the rates of hospitalisations due to gastroenteritis increasing with increasing age (p<0.001 for linear trend). Male sex was significantly related to a reduced risk (aHR 0.75, 95% CI 0.69 to 0.81). Poorer self-rated health (aHR 3.45, 95% CI 2.80 to 4.26), obesity (1.12, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.22) and PPIs use (1.74, 95% CI 1.61 to 1.89) were all related to an increased risk of hospitalisations due to gastroenteritis. The sensitivity analysis, including cases with a linked record of hospital admission with pre-existing illness, showed little change in the HRs (n=266 146; 6783 incident hospitalisations due to gastroenteritis since baseline; see online supplementary table S2).

Discussion

In this large population-based prospective study, hospitalisation due to infectious gastroenteritis was extremely common. We estimate that 1% of people aged ≥65 years old were hospitalised annually with gastroenteritis, and accounted for more than two-thirds of gastroenteritis-related complications. The incidence and length of hospital stay increased dramatically with increasing age. After adjustment, females, adults with poor general health, and those taking PPIs had a greater risk of being hospitalised with gastroenteritis.

The high rate of hospitalisations due to gastroenteritis in the elderly is consistent with increased rates of hospitalisation for infectious disease in this age group,7 17 although the rate in people aged ≥65 years old was lower than a previous study examining hospitalisations due to gastroenteritis nationally due to all causes.7 This may reflect differences in study design and case definitions. In particular, the national study included admission codes for conditions that were not necessarily infectious in nature, whereas, we attempted to include only infectious causes. The trend of increasing hospitalisations with age in our study is likely to be due to greater severity of illness in older patients,18 and the increasing likelihood of severe consequences, such as dehydration, electrolyte imbalance and exacerbation of chronic conditions.19

Differences by sex were noted for hospitalisations due to gastroenteritis in all age groups. The pattern was previously reported in a US study, which used nationally representative data to investigate the trend of hospitalisations due to infectious disease for all ages.20 One possible explanation for the higher rate in females may be inadequate family support and social care for older women, possibly resulting in greater use of hospital services. In this study, we observed a higher proportion of female cases (62%) having an additional diagnosis coded with an ICD-10-AM for living alone (Z60.2), inadequate family support (Z63.2) and absence of a family member (Z63.3), than male cases (38%) at the time of admission, which may indicate an inadequate care of female patients in our study.

Self-rated health has previously been reported as a significant predictor of severe health outcomes, such as mortality.21 Although mortality remains the strongest biological indicator of ill-health, disease-related hospitalisation captures the direct burden of illness. In our study, participants’ responses to questions about self-rated health demonstrated a strong association with hospitalisations due to gastroenteritis. Consequently, poor self-rated health may serve as a useful marker for people at higher risk of hospitalisation who present to family physicians with gastroenteritis. Similarly, people with a very high or very low BMI were at higher risk of hospitalisation with gastroenteritis. These findings highlight the importance of general health in affecting hospitalisation with gastrointestinal infection in older adults.

We identified an association between PPIs use and hospitalisation with gastroenteritis, which has been consistently shown in previous studies investigating risk factors for gastrointestinal infections.22 23 Treatment with PPIs lowers gastric acidity, which is a first line of defence against ingested pathogens, leading to bacterial colonisation, thus increasing an individual's susceptibility to enteric infection.24 A recent study examining the incidence of Salmonella and Campylobacter infection in patients prescribed PPIs argued that such people were already at higher underlying risk of enteric infection before prescription.25 In our study, PPIs use was self-reported at recruitment, and was significantly associated with later hospitalisation for gastroenteritis even after adjusting for self-rated health at baseline. Although our study was insufficient to establish a causal relationship, this adds to the evidence that PPIs are associated with hospitalisation involving enteric infection.

We investigated the possible association between food consumption history and the risk of gastroenteritis, but did not observe any association between frequency of fruit and vegetable intake, chicken and poultry, seafood or eggs, and risk of hospitalisations due to infectious gastroenteritis. This may be due to the nature of the baseline questionnaire that did not collect detailed dietary information of participants. For example, in the questionnaire, participants were only asked if they ever eat eggs, and did not collect information on frequency of egg consumption. Additionally, our study captures cases of gastroenteritis due to a range of aetiological agents, so it is not surprising that foods were not important risk factors. Campylobacter spp and Salmonella spp are commonly found in adult patients hospitalised with infectious gastroenteritis,26 although viral enteritis has also been identified as a key cause of seasonal increases in hospitalisation among the elderly.27

Our study has several limitations that may influence the interpretation of results. First, risk factors were reported at the time of recruitment, and may have changed between recruitment and hospitalisation. Second, exposure assessment was based on self-report. Dietary intake can be difficult to measure, despite self-report being reasonably reliable for some factors.28 29 However, a validation study involving the short questions related to diet used in the 45 and Up Study questionnaire has shown them to be reproducible over time.30 Third, the 45 and Up study cohort, while including about 1 in 10 adults in the age range in NSW, is likely to be more health conscious than the general NSW population, hence, the rates of hospitalisations due to gastroenteritis may be underestimated, although this would be unlikely to affect within-cohort comparisons, such as the estimates of HRs.31

Conclusion

Our results highlight a substantial burden to the healthcare system from gastroenteritis in an aging population. Future efforts should focus on defining and improving preventive measures for hospitalisations due to gastroenteritis among the elderly. Early recognition and supportive treatment of diarrhoea in older patients with poorer self-rated health may prevent subsequent hospitalisation. Additionally, further research is required to examine if PPIs use results in excess hospitalisations due to gastroenteritis and specific enteric infections, as it is a potentially modifiable risk factor.

Acknowledgments

This study was completed using data collected through the 45 and Up Study. The 45 and Up Study is managed by the Sax Institute in collaboration with major partner Cancer Council New South Wales (NSW); and partners: the National Heart Foundation of Australia (NSW Division); beyondblue; NSW Ministry of Health; NSW Government Family & Community Services—Carers, Ageing and Disability Inclusion; Australian Red Cross Blood Service. The Centre for Health Record Linkage conducted the record linkage, and the NSW Ministry of Health provided the linked health datasets. The authors thank all the participants in the 45 and Up Study.

Footnotes

Contributors: YC performed the analyses and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. BCL, KG and MDK provided input to the design of the study and interpretation of results, and provided advice on the drafting of the manuscript. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: YC received the 2014 Prime Minister's Australia Asia Postgraduate Scholarship from the Australian Government Department of Education and Training.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The conduct of the 45 and Up Study was approved by the University of New South Wales Human Research Ethics Committee. Ethics approval for this study was obtained from the NSW Population and Health Services Research Ethics Committee, the NSW Cancer Institute Human Research Ethics Committee, and the Australian National University Human Research Ethics Committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Black RE, Cousens S, Johnson HL et al. Global, regional, and national causes of child mortality in 2008: a systematic analysis. Lancet 2010;375:1969–87. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60549-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gangarosa RE, Glass RI, Lew JF et al. Hospitalizations involving gastroenteritis in the United States, 1985: the special burden of the disease among the elderly. Am J Epidemiol 1992;135:281–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jagai JS, Smith GS, Schmid JE et al. Trends in gastroenteritis-associated mortality in the United States, 1985–2005: variations by ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes. BMC Gastroenterol 2014;14:211 10.1186/s12876-014-0211-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gavazzi G, Krause K-H. Ageing and infection. Lancet Infect Dis 2002;2:659–66. 10.1016/S1473-3099(02)00437-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Castle SC. Clinical relevance of age-related immune dysfunction. Clin Infect Dis 2000;31:578–85. 10.1086/313947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kirk MD, Hall GV, Becker N. Gastroenteritis in older people living in the community: results of two Australian surveys. Epidemiol Infect 2012;140:2028–36. 10.1017/S0950268811002834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dey A, Wang H, Menzies R et al. Changes in hospitalisations for acute gastroenteritis in Australia after the national rotavirus vaccination program. Med J Aus 2012;197:453 10.5694/mja12.10062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lopman BA, Hall AJ, Curns AT et al. Increasing rates of gastroenteritis hospital discharges in US adults and the contribution of norovirus, 1996–2007. Clin Infect Dis 2011;52:466–74. 10.1093/cid/ciq163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Friesema I, Lugnér A, Van Duynhoven Y et al. Costs of gastroenteritis in the Netherlands, with special attention for severe cases. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2012;31:1895–900. 10.1007/s10096-011-1518-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gibney KB, O'Toole J, Sinclair M et al. Disease burden of selected gastrointestinal pathogens in Australia, 2010. Int J Infect Dis 2014;28:176–85. 10.1016/j.ijid.2014.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Collaborators, the 45 and Up Study. Cohort profile: the 45 and up study. Int J Epidemiol 2008;37:941 10.1093/ije/dym184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roberts RF, Innes KC, Walker SM. Introducing ICD-10-AM in Australian hospitals. Med J Aus 1998;169:S32–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Centre for Health Record Linkage. http://www.cherel.org.au (accessed Aug 2014).

- 14. Anon. ARIA and Accessibility 2014 (cited 1 October 2014). https://www.adelaide.edu.au/apmrc/research/projects/category/aria.html.

- 15.Thiébaut A, Bénichou J. Choice of time-scale in Cox's model analysis of epidemiologic cohort data: a simulation study. Stat Med 2004;23:3803–20. 10.1002/sim.2098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pettitt A, Daud IB. Investigating time dependence in Cox's proportional hazards model. Appl Stat 1990:39: 313–29. 10.2307/2347382 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yorita Christensen KL, Holman RC, Steiner CA et al. Infections disease hospitalizations in the United States. Clin Infect Dis 2009;49:1025–35. 10.1086/605562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fleury MD, Stratton J, Tinga C et al. A descriptive analysis of hospitalization due to acute gastrointestinal illness in Canada, 1995–2004. Can J Public Health 2008;99:489–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yoshikawa T, Norman D. Infectious disease in the aging: a clinical handbook. Springer Science & Business Media, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Christensen KLY, Holman RC, Steiner CA et al. Infectious disease hospitalizations in the United States. Clin Infect Dis 2009;49:1025–35. 10.1086/605562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.DeSalvo KB, Bloser N, Reynolds K et al. Mortality prediction with a single general self-rated health question. J Gen Intern Med 2006;21:267–75. 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.00291.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pilotto A, Franceschi M, Vitale D et al. The prevalence of diarrhea and its association with drug use in elderly outpatients: a multicenter study. Am J Gastroenterol 2008;103:2816–23. 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.02107.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garcia Rodriguez LA, Ruigomez A, Panes J. Use of acid-suppressing drugs and the risk of bacterial gastroenteritis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2007;5:1418–23. 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bavishi C, Dupont H. Systematic review: the use of proton pump inhibitors and increased susceptibility to enteric infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2011;34:1269–81. 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04874.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brophy S, Jones KH, Rahman MA et al. Incidence of Campylobacter and Salmonella infections following first prescription for PPI: a cohort study using routine data. Am J Gastroenterol 2013;108:1094–100. 10.1038/ajg.2013.30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jansen A, Stark K, Kunkel J et al. Aetiology of community-acquired, acute gastroenteritis in hospitalised adults: a prospective cohort study. BMC Infect Dis 2008;8:143 10.1186/1471-2334-8-143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chui KK, Jagai JS, Griffiths JK et al. Hospitalization of the elderly in the United States for nonspecific gastrointestinal diseases: a search for etiological clues. Am J Public Health 2011;101:2082–6. 10.2105/AJPH.2010.300096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Comino EJ, Tran DT, Haas M et al. Validating self-report of diabetes use by participants in the 45 and Up Study: a record linkage study. BMC Health Serv Res 2013;13:481 10.1186/1472-6963-13-481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ng SP, Korda R, Clements M et al. Validity of self-reported height and weight and derived body mass index in middle-aged and elderly individuals in Australia. Aust N Z J Public Health 2011;35:557–63. 10.1111/j.1753-6405.2011.00742.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roddam AW, Spencer E, Banks E et al. Reproducibility of a short semi-quantitative food group questionnaire and its performance in estimating nutrient intake compared with a 7-day diet diary in the Million Women Study. Public Health Nutr 2005;8:201–13. 10.1079/PHN2004676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mealing NM, Banks E, Jorm LR et al. Investigation of relative risk estimates from studies of the same population with contrasting response rates and designs. BMC Med Res Methodol 2010;10:26 10.1186/1471-2288-10-26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]