Abstract

Objective

To determine whether drugs used in treatment of cardiovascular diseases (CVD-drugs), including hypertension, increase the risk of fragility fractures in individuals above the age of 65 years.

Design

Retrospective nationwide cohort study.

Setting

Danish nationwide national registers.

Participants

All individuals in Denmark ≥65 years who used specified CVD-drugs in the study period between 1999 and 2012.

Main outcomes measures

Time-dependent exposure to CVD-drugs (nitrates, digoxin, thiazides, furosemide, ACE inhibitors, angiotensin receptor antagonists, β-blockers, calcium antagonists and statins) was determined by prescription claims from pharmacies. The association between use of specific CVD-drugs and fragility fractures was assessed using multivariable Poisson regression models, and adjusted incidence rate ratios (IRRs) were calculated.

Results

Overall, 1 586 554 persons were included, of these 16.1% experienced a fall-related fracture. The multivariable Poisson regression analysis showed positive associations between fracture and treatment with furosemide, thiazide and digoxin. IRRs during the first 14 days of treatment were for furosemide IRR 1.74 (95% CI 1.61 to 1.89) and for thiazides IRR 1.41 (1.28 to 1.55); IRR during the first 30 days of treatment with digoxin was 1.18 (1.02 to 1.37).

Conclusions

Use of furosemide, thiazides and digoxin was associated with elevated rates of fragility fractures among elderly individuals. This may warrant consideration when considering diuretic treatment of hypertension in elderly individuals.

Keywords: accidental falls, fragility fractures, cardiovaslular drugs

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Large nationwide study including all individuals above the age of 65 years.

Owing to the large number of individuals included, it has been possible to investigate adverse events of specific drugs at specific time periods.

Linking between several national registers made it possible to adjust the analysis for comorbidity.

Observational design.

Bias due to confounding by indication cannot be fully excluded.

Introduction

Fragility fractures are fractures that result from mechanical forces that would not ordinarily result in fracture, known as low-level (or ‘low energy’) trauma. The WHO has quantified this as forces equivalent to a fall from a standing height or less.1 Fragility fractures are a major health problem for elderly people. Approximately 90% of all fragility fractures are due to falls.2 Among community-dwelling elderly populations, 30–60% fall at least once every year and serious injuries occur in 5–10% of all falls.3

With a growing elderly population, the prevalence of fragility fractures is increasing throughout the western world.4 At the same time, the prevalence of a number of chronic diseases is increasing and leads to an increase in use of medications, a situation which has led several researchers to speak of the ‘treatment burden’.5–7 With ageing, the ability to maintain homoeostasis declines and the risk of adverse effects when the organism is challenged by external or internal stimuli, like medications or diseases, increases.8 Furthermore, ageing is associated with a number of factors that influence pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics.9–12 Taken together, this makes the elderly individual susceptible to adverse effects from medical treatment. However, due to vague and atypical presentation of symptoms and diseases in elderly individuals, the adverse effects may not be recognised as such.13 Several drugs used in treatment of cardiovascular disease have been associated with falls and fragility fractures.14–16 However, the evidence is sparse.17 18 There are no randomised controlled studies, and the existing observational studies generally include small populations and are heterogeneous concerning populations, settings and definition of falls.14 15 19

Several methodological difficulties can explain the lack of randomised trials in this group of patients. The randomised controlled trial design builds on the assumption that it is possible to have two groups of patients who are comparable apart from the intervention that the study seeks to investigate. This assumption may be difficult to meet when studying frail elderly individuals, since genetic differences, lifelong living habits and different environments all contribute to increase interindividual heterogeneity with ageing. Elderly patients tend to have comorbidity, which means that they are excluded from the majority of clinical trials.20 21 Even a study designed to investigate the effect of antihypertensive treatment in persons >80 years included the healthiest segment and the authors stated, “it would be premature to extrapolate the results from HYVET to patients in this age group who are more frail”.22 Furthermore, it may be too demanding for frail elderly individuals to participate in randomised trials. Taken together, these difficulties lead to randomised trials not including the clinical relevant patients.23–29 Commonly used end points in trials investigating effects of CVD drugs are cardiovascular mortality, cerebrovascular events and all-cause mortality. Fractures leading to hospitalisation will be registered as adverse events, but the trials are not powered to investigate falls or fractures as an end point.

To overcome some of these gaps in current knowledge, we performed a nationwide register-based study in order to investigate the effect of medical treatment for cardiovascular disease on the occurrence of fragility fractures in elderly individuals. The large population allowed us to investigate the effect of specific drugs and time intervals.

Methods

Study population

We included all residents in Denmark aged 65 years or older between 1 January 1999 and 31 December 2012. Individuals were followed from either 1 January 1999, their 65th birthday, or at their date of immigration (if older than 65 years at immigration) until a diagnosis of a fall-related fracture, emigration, death or 31 December 2012, whichever occurred first.

Databases

This study is a nationwide register-based Danish cohort study. For administrative purposes, every person in Denmark has been given a unique personal identification number since 1968. This enables individual-level linkage of Danish citizens through several national registries. In the present study, we used data from the Danish Civil Registration System, the Danish National Patient Registry, and the Danish Registry of Medicinal Products Statistics. The Danish Civil Registration System contains information about dates of birth and death of all Danish citizens since 1968.30 The Danish National Patient Registry contains records of all hospitalisations in Denmark since 1977.31 The Danish Registry of Medicinal Products Statistics contains data on all prescriptions dispensed in Denmark since 1994, including information about medicine strength, quantity dispensed and dispensing date. Prescriptions are classified according to the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) system.32

Outcome assessment

Fragility fractures were identified in the Danish National Patient Registry if individuals were hospitalised with the diagnosis of one of the following diagnoses classified with the International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision (ICD-10): fracture of sacrum (S321), fracture of coccyx (S322), fracture of ilium (S323), fracture of acetabulum (S324), fracture of pubis (S325), fracture of shoulder and arm (S42), fracture of forearm (S52), fracture at wrist and hand level (S62) and fracture of femur (S72).

Pharmacotherapy and duration of treatment

From the Danish Registry of Medicinal Products, we identified commonly used cardiovascular drugs. In this study, we investigated the following classes of cardiovascular drugs (ATC codes in brackets): nitrates (C01DA08, C01DA14), digoxin (C01AA05), thiazide (C03AB01), ACE inhibitors (C09AA01, C09AA02, C09AA03, C09AA04, C09AA05, C09AA10), furosemide (C03CA01), calcium antagonists (C08CA01, C08CA02, C08DA01, C08DB01), β-blockers (C07AA05, C07AB02, C07AB03, C07AB07, C07AG02), statins (C10AA01, C10AA03, C10AA05, C10AA07) and angiotensin receptor antagonists (C09CA01, C09CA03, C09CA04, C09CA06, C09CA07, C09CA08).

Treatment status was determined in a time-dependent manner by prescription claims from the Danish pharmacies, implying that individuals were only considered exposed if covered by claimed prescriptions. To determine treatment length, up to three consecutive prescriptions were considered in a retrospective manner. We created an algorithm for each drug and tablet strength in which minimum, maximum and typical daily dosages of the medication were defined. From patients’ initial prescriptions, the typical daily dosage was assigned, and treatment length was calculated by dividing the amount of first-claimed medications by that daily dosage. For patients who were covered by a previous prescription at the time of claiming a new prescription, the daily dosage was reset and a new daily dosage was calculated as the amount of claimed medications during the previous period divided by time between prescription claims (based on up to 3 previous prescriptions without treatment breaks). If calculated dosages exceeded the predefined highest daily dosages, patients were assigned the maximum osages, and the exceeding tablets were assumed to be stored and consumed during the immediate period following the end of the last prescription.

Furthermore, the date of the first prescription from 1 year prior to inclusion and throughout the study period was identified in order to define time since initiating treatment. Time since initiating treatment was grouped into periods of 0–14, 15–30, 31–90, 91–180 or >180 days. These time periods were chosen in order to discriminate between acute effects possibly due to direct cardiovascular effects, and later effects possibly due to effect on bones or muscles. Persons who were on a specific drug at inclusion were included and placed in the relevant time period according to date of the first prescription.

Comorbidities

We identified comorbidities known to be associated with falls: ischaemic heart disease, stroke, hypertension, heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cancer, diabetes, depression, dementia, osteoporosis, Parkinson's disease and previous fragility fractures.33 We used inhospital diagnoses from the Danish National Patient Registry to identify comorbidities. Some diseases are diagnosed primarily in an outpatient setting and we, therefore, included relevant medications from the Danish Registry of Medicinal Products Statistics to identify these comorbidities. We did this for the following diseases (ATC codes in brackets): depression (N06A), dementia (N06D), diabetes (A10), osteoporosis (M05B) and Parkinson's disease (N04). All comorbidities were identified from 1977 and throughout the observation period. Previous fragility fractures were defined as any fracture 5 years prior to inclusion.

Statistics

We applied time-dependent multivariable Poisson regression models to test the association between the different cardiovascular drugs and fall-related fractures. Prior to analysis, observational time was divided into bands of 1-year intervals and age was updated at the start of each time band. To ensure timely correct categorisation of comorbidities and exposure, all comorbidities were included as time-dependent variables. The importance of time since initiation of the different CVD-drugs was explored by including variables as use versus no use of a specific agent in a specific time window (eg, ‘nitrates 0–14 days’, ‘digoxin 91–180 days’, etc). The Poisson regression model was adjusted for age, gender, calendar year, comorbidities and exposure to the other classes of CVD-drugs. In order to address possible confounding by indication, we performed a subanalysis stratified by heart failure.

All analyses were conducted using SAS, V.9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA), a two-sided p value of <0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Ethics

No ethics approval is required for retrospective register-based studies in Denmark.

Results

Overall, 1 586 554 individuals were included in the study cohort with a maximum follow-up time of 14 years. The mean follow-up time was 6.7 years, and loss to follow-up due to emigration was 0.3%.

During follow-up, 255 936 individuals (16.1%) experienced a fragility fracture; of these, 90 994 (5.7%) were in treatment with CVD-drugs at the time of the fracture. Numbers ever exposed to the different CVD-drugs are presented in table 1. Individuals treated with CVD-drugs were older, and they generally had more comorbidity compared with the general population. Further population characteristics regarding gender, age and comorbidities in relation to the classes of CVD-drugs are shown in table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study population

| No treatment n=725 692 |

Nitrates n=66 931 |

Digoxin n=92 232 |

Thiazides n=322 262 |

ACE inhibitors n=299 498 |

Loop diuretics n=300 135 |

Calcium antagonists n=270 655 |

β-Blockers n=273 428 |

Statins n=315 143 |

ARBs n=153 446 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (SD) in years | 70.6 (8.0) | 77.3 (7.5) | 78.7 (7.6) | 75.3 (7.2) | 74.8 (6.9) | 77.8 (7.8) | 74.7 (6.9) | 75.0 (7.0) | 73.1 (6.1) | 74.2 (6.6) |

| Gender, male (%) | 324 105 (44.7) | 34 291 (51.3) | 44 189 (47.9) | 133 469 (41.4) | 142 259 (47.5) | 142 251 (47.4) | 119 206 (44.0) | 130 210 (47.6) | 152 412 (48.4) | 65 180 (42.5) |

| Comorbidities | ||||||||||

| Cancer (%) | 62 564 (8.6) | 8325 (12.4) | 15 260 (16.6) | 39 232 (12.2) | 33 301 (11.1) | 57 014 (19.0) | 31 129 (11.5) | 33 458 (12.2) | 33 038 (10.5) | 17 465 (11.4) |

| AMI (%) | 45 051 (6.2) | 24 458 (36.6) | 16 608 (18.0) | 28 057 (8.7) | 43 595 (14.6) | 48 088 (16.0) | 26 752 (9.9) | 53 437 (19.5) | 51 369 (16.3) | 16 837 (11.0) |

| Heart failure (%) | 35 607 (4.9) | 14 019 (21.0) | 25 062 (27.2) | 18 121 (5.6) | 34 833 (11.6) | 44 729 (14.9) | 17 014 (6.3) | 34 580 (12.6) | 24 125 (7.7) | 12 425 (8.1) |

| Hypertension (%) | 55 036 (7.6) | 20 088 (30.0) | 23 633 (25.6) | 50 881 (15.8) | 65 493 (21.9) | 72 780 (24.3) | 68 243 (25.2) | 64 463 (23.6) | 75 082 (23.8) | 41 242 (26.9) |

| Stroke (%) | 47 771 (6.6) | 9392 (14.0) | 14 656 (15.9) | 32 202 (10.0) | 33 348 (11.1) | 41 386 (13.8) | 28 593 (10.6) | 29 373 (10.7) | 50 153 (15.9) | 15 616 (10.2) |

| Diabetes (%) | 25 791 (3.6) | 7833 (11.7) | 8440 (9.2) | 16 179 (5.0) | 23 158 (7.7) | 27 430 (9.1) | 18 272 (6.8) | 21 065 (7.7) | 25 558 (8.1) | 12 933 (8.4) |

| Depression (%) | 7717 (1.1) | 1366 (2.0) | 2822 (3.06) | 4856 (1.5) | 4465 (1.5) | 7793 (2.6) | 4220 (1.6) | 4137 (1.5) | 4948 (1.6) | 2026 (1.3) |

| Dementia (%) | 10 465 (1.4) | 1314 (1.9) | 2822 (3.1) | 6326 (2.0) | 4051 (1.4) | 11 446 (3.8) | 3724 (1.4) | 3754 (1.3) | 4084 (1.3) | 1535 (1.0) |

| Parkinson’s (%) | 4785 (0.7) | 502 (0.8) | 745 (0.8) | 2126 (0.7) | 1288 (0.4) | 3385 (1.1) | 1146 (0.4) | 1378 (0.5) | 1209 (0.4) | 501 (0.3) |

| COPD (%) | 25 437 (3.5) | 7972 (11.9) | 13 474 (14.6) | 17 858 (5.5) | 18 355 (6.1) | 33 608 (11.2) | 16 502 (6.1) | 15 827 (5.8) | 17 115 (5.4) | 7521 (4.9) |

| Osteoporosis (%) | 22 770 (3.1) | 3059 (4.6) | 4566 (5.0) | 12 299 (3.8) | 11 411 (3.8) | 15 244 (5.1) | 11 302 (4.2) | 10 637 (3.9) | 12 434 (3.9) | 6382 (4.2) |

Baseline characteristics for different CVD-drug users. Numbers are presented as counts (%) for categorical variables and mean (SD) for continuous measures. Characteristics for each of the treatment groups refer to those obtained at first day of treatment; thus, groups are not exclusive. ‘No treatment’ refers to day of inclusion in the study. The table shows data for the whole population, including persons without cardiovascular disease.

AMI, acute myocardial infarction; ARB, angiotensin receptor blockers; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CVD, cardiovascular disease.

Total exposure time, and numbers of fractures for each group of drugs and for those unexposed are given in table 2. Crude fracture rates were highest among patients treated with loop diuretics, digoxin or thiazides; in the remaining CVD-drugs, the crude fracture rates were similar to the unexposed.

Table 2.

Incidence rates and 95% CIs, observation time, and number of events according to exposure status

| Number of events | Observation time (person years) | Incidence rate per 100 person years (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-exposed | 164.942 | 7.167.515 | 2.30 (2.29 to 2.31) |

| Nitrates (days) | |||

| 0–14 | 91 | 2.690 | 3.38 (2.75 to 4.15) |

| 15–30 | 62 | 2.736 | 2.27 (1.77 to 2.91) |

| 31–90 | 274 | 7.819 | 3.50 (3.11 to 3.94) |

| 91–180 | 294 | 8.973 | 3.27 (2.92 to 3.67) |

| >180 | 4.155 | 120.238 | 3.46 (3.35 to 3.56) |

| Digoxin (days) | |||

| 0–14 | 156 | 3.739 | 4.17 (3.57 to 4.88) |

| 15–30 | 188 | 4.106 | 4.58 (3.97 to 5.28) |

| 31–90 | 495 | 12.583 | 3.93 (3.08 to 3.67) |

| 91–180 | 505 | 15.013 | 3.36 (3.08 to 3.67) |

| >180 | 5.792 | 189.066 | 3.06 (2.98 to 3.14) |

| Thiazides (days) | |||

| 0–14 | 446 | 12.518 | 3.56 (3.25 to 3.91) |

| 15–30 | 518 | 13.414 | 3.86 (3.54 to 4.21) |

| 31–90 | 1.502 | 44.958 | 3.34 (3.18 to 3.51) |

| 91–180 | 1.276 | 46.335 | 2.75 (2.61 to 2.91) |

| >180 | 18.057 | 687.456 | 2.63 (2.59 to 2.67) |

| ACE inhibitors (days) | |||

| 0–14 | 273 | 11.821 | 2.31 (2.05 to 2.60) |

| 15–30 | 330 | 13.092 | 2.52 (2.26 to 2.81) |

| 31–90 | 980 | 41.447 | 2.36 (2.22 to 2.52) |

| 91–180 | 1.124 | 49.915 | 2.25 (2.12 to 2.39) |

| >180 | 15.910 | 640.066 | 2.49 (2.45 to 2.52) |

| Loop diuretics (days) | |||

| 0–14 | 615 | 11.590 | 5.31 (4.90 to 5.74) |

| 15–30 | 570 | 11.883 | 4.80 (4.42 to 5.21) |

| 31–90 | 1.329 | 30.281 | 4.39 (4.16 to 4.63) |

| 91–180 | 1.584 | 36.189 | 4.38 (4.17 to 4.60) |

| >180 | 18.846 | 475.456 | 3.96 (3.91 to 4.02) |

| Calcium antagonists (days) | |||

| 0–14 | 249 | 10.532 | 2.36 (2.09 to 2.68) |

| 15–30 | 315 | 11.900 | 2.64 (2.37 to 2.96) |

| 31–90 | 926 | 39.813 | 2.33 (2.18 to 2.48) |

| 91–180 | 1.111 | 50.428 | 2.20 (2.08 to 2.34) |

| >180 | 16.691 | 663.196 | 2.52 (2.48 to 2.56) |

| β-Blockers (days) | |||

| 0–14 | 260 | 10.843 | 2.39 (2.12 to 2.71) |

| 15–30 | 304 | 11.932 | 2.55 (2.28 to 2.85) |

| 31–90 | 974 | 37.562 | 2.59 (2.44 to 2.76) |

| 91–180 | 1.208 | 47.672 | 2.53 (2.40 to 2.68) |

| >180 | 19.194 | 761.936 | 2.52 (2.48 to 2.56) |

| Statins (days) | |||

| 0–14 | 224 | 12.342 | 1.81 (1.59 to 2.07) |

| 15–30 | 267 | 14.033 | 1.90 (1.69 to 2.15) |

| 31–90 | 877 | 48.745 | 1.80 (1.68 to 1.92) |

| 91–180 | 1.168 | 62.608 | 1.87 (1.76 to 1.98) |

| >180 | 22.858 | 1.100.165 | 2.08 (2.05 to 2.10) |

| Angiotensin receptor antagonists (days) | |||

| 0–14 | 131 | 5.897 | 2.22 (1.87 to 2.64) |

| 15–30 | 129 | 6.185 | 2.09 (1.75 to 2.48) |

| 31–90 | 379 | 19.938 | 1.90 (1.72 to 2.10) |

| 91–180 | 556 | 26.130 | 2.12 (1.96 to 2.31) |

| >180 | 7.636 | 333.944 | 2.29 (2.24 to 2.34) |

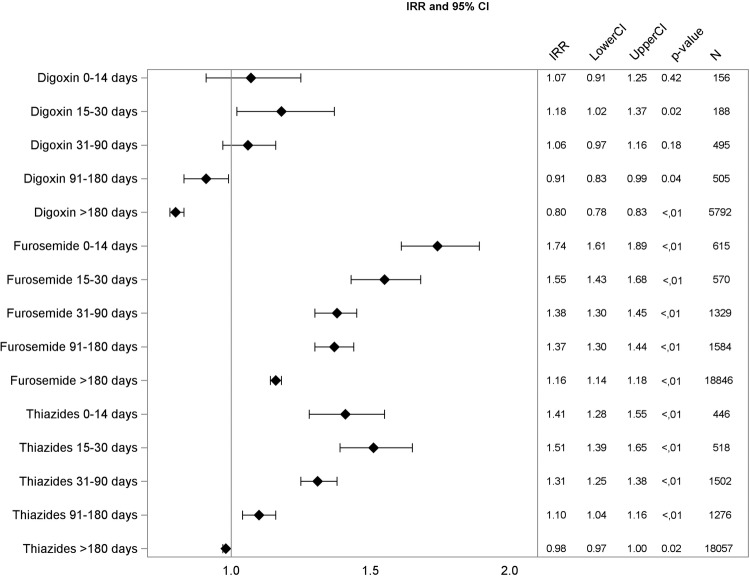

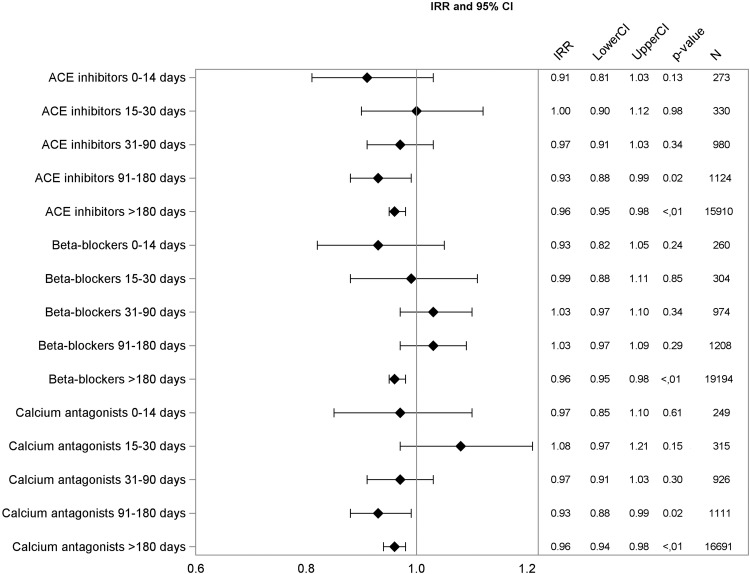

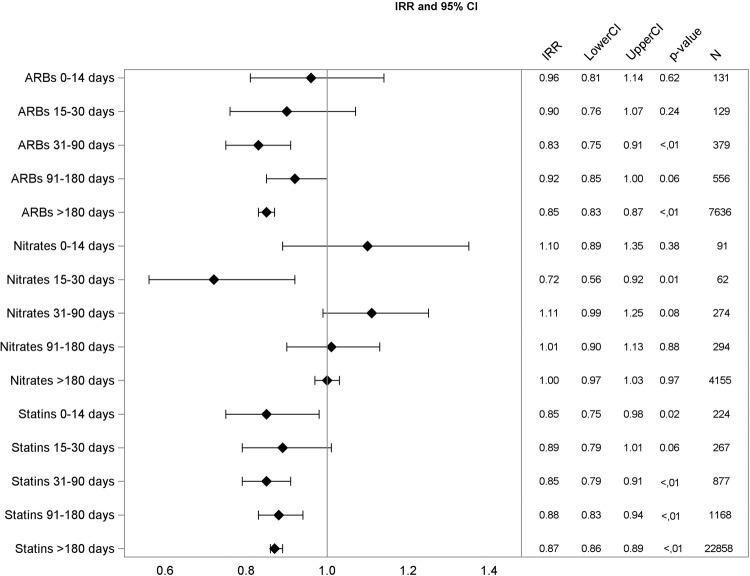

Multivariable Poisson regression analysis yielded similar patterns. The association between drug use and fragility fractures was generally strongest in the time interval of 0–14 days after drug initiation. Diuretics were significantly associated with fractures in this initial treatment period: furosemide with incidence rate ratio (IRR) 1.74 (CI 1.61 to 1.89), and thiazides with IRR 1.41 (CI 1.04 to 1.16). Digoxin was significantly associated with falls only in the period between 15 and 30 days after treatment start, and the association was weak (IRR 1.18, CI 1.02 to 1.37), data shown in figures 1–3.

Figure 1.

Adjusted incidence rate ratios (IRR), 95% CIs, p value, and number of events for digoxin, furosemide, and thiazides.

Figure 2.

Adjusted incidence rate ratios (IRR), 95% CIs, p value, and number of events for ACE inhibitors, beta-blockers, and calcium antagonists.

Figure 3.

Adjusted incidence rate ratios (IRR), 95% CIs, p value, and number of events for angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), nitrates, and statins.

Analysis stratified by heart failure showed no significant change in risk estimates for individuals with prior diagnosis of heart failure compared with individuals with no prior diagnosis of heart failure.

Discussion

In this nationwide study including individuals aged ≥65 years, we investigated the association between different cardiovascular drugs and incidence of fragility fractures. We observed that use of loop diuretics and thiazides were significantly associated with fragility fractures, while the remaining antihypertensive drugs, statins and nitrates were not. The fact that the association between drugs and fragility fractures was strongest during the first 2 weeks of treatment and thereafter, gradually declined suggests that the increase in fragility fractures is due to increase in falls rather than changes in bone health. The finding that only diuretics were associated with fragility fractures is new. In a register-based study, we cannot conclude anything on the mechanism of a possible association. However, hyponatremia has been shown to increase the risk of fractures independent of osteoporosis, probably due to the cognitive effect and the effect on balance measures of even mild hyponatremia.34 35 Diuretic-associated hyponatremia may, therefore, partly explain the association.

Other studies

Other studies have found that long-term thiazide use reduces the risk of fractures possibly due to the calcium-retaining effect in the renal tubules.36 Our study is concerned with the risk of fragility fractures in the initial treatment period and does not contradict this finding.

A meta-analysis including studies performed in the period 1966–1996 found association between falls and use of diuretics, digoxin and type1A antiarrhythmic agents.14 However, the authors explain that the results may be biased due to few people taking each drug class and few people falling, resulting in very wide CIs in the included studies. A recent meta-analysis, an update of the previous one, included another 22 studies published during 1997–2007; this found no significant associations between use of any cardiovascular drug and falls.15 All studies included in the two meta-analyses are observational studies and are heterogeneous concerning study methods, settings, power and fall definition. In a comprehensive systematic review of risk factors for falls, Deandrea et al37 found an OR 1.25 (CI 1.05 to 1.44) for use versus non-use of antihypertensive drugs.

Only few relevant studies have been published after the latest meta-analysis. Butt et al38 39 studied the association between use of antihypertensive drugs and the occurrence of falls and hip fractures in an elderly population in Ontario, Canada, using a self-controlled design. Sample size in the fracture study was smaller (1463 cases) than in the falls study (8893 cases), and the association in the falls study was stronger for all drugs. In the falls study, there were significant associations between falls and new use of thiazide diuretics, calcium channel blockers, ACE inhibitors and β-blockers, but not for angiotensin receptor antagonists. Gribbin et al used a self-controlled design and found significant association between use of thiazide diuretics and falls, IRR 2.8 (CI 1.7 to 4.6), but not for β-blockers, calcium channel blockers or ACE inhibitors. The authors mention that results may be diluted by misclassification of exposure periods, and that the falls outcome represents a small subset of self-reported falls.40

Berry et al found a significant association between starting a loop diuretic and incident hip fracture, with OR 1.8 (CI 1.2 to 2.7) for hip fracture during days 1–7 after treatment start. The maximum effect of a thiazide diuretic on the acute risk of hip fracture occurred 8–14 days following drug initiation (OR=2.2, 95% CI 1.2 to 3.9).41 Tinetti et al42 followed 4961 elderly individuals for 3 years and found association between serious falls and moderate intensity use of antihypertensive drugs with OR 1.40 (CI 1.03 to 1.9). In a propensity matched subgroup, the association did not reach significance.

In summary, our results are similar to the findings in the most recent and self-controlled studies. Results from earlier studies included in the two meta-analyses are more diverse.14 15

Strengths and limitations

A major strength of this study is the large population, which allowed us to examine the association between fractures and exposure to specific cardiovascular drugs. However, it is an observational study, and we cannot fully exclude the effect of unmeasured confounders. There are several risk factors for falls and fragility fractures that we have not been able to include; however, we have no reason to believe that these risk factors influence the exposure to CVD-drugs. In a Poisson analysis we cannot distinguish between the risk of starting medication and the risk of the disease, which was the reason for the medication. This means that the associations may merely reflect the underlying condition. However, the diversity of results concerning drugs used for the same indications, that is, hypertension and heart failure, indicates that the results are not driven by confounding by indication. We have further minimised the risk of confounding by controlling for comorbidity known to be associated with falls and fractures, including previous fragility fractures.

We have investigated the association with single drugs. Since elderly persons will often use several drugs at the same time, our estimates of association are possibly lower than in real life.

IRRs for all drugs became lower with time. Owing to the observational design, we cannot rule out that this is partly caused by healthy user bias.

Conclusion and clinical implications

Our study supports previous concerns about the risk of falls and fractures associated with antihypertensive treatment in elderly individuals. However, the association between fragility fractures and use of antihypertensive treatment seems only to be true for diuretic treatment.

We suggest that the effect of diuretic treatment in hypertension should be carefully controlled, and use of alternative antihypertensives should be considered in elderly individuals.

The association between digoxin and fragility fractures was so weak that we would not consider this finding as basis of any clinical implication on its own; however, the finding do contribute to recently reported concerns regarding the use of digoxin.43

Footnotes

Contributors: MT and EH had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. MT, CT-P and EH were involved in study concept and design. CT-P and GG were involved in acquisition of data. All authors were involved in analysis and interpretation of data. MT and EH were involved in drafting of the manuscript. All authors were involved in critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. MT was involved in statistical analysis. GG, CT-P and EH were involved in study supervision.

Funding: This research was supported by a grant from the public Regional Research Foundation, Region Zealand.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at http://www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author), and CT-P reports grants and personal fees from Cardiome, grants and personal fees from Merck, grants and personal fees from Sanofi, grants and personal fees from Daiichi, grants from BMS, all outside the submitted work.

Ethics approval: This study was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency (j.nr:2007-58-0015 / local j.nr. GEH-2014-013 I-Suite nr: 02731).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.NICE. Osteoporosis: assessing the risk of fragility fractures. 2012. http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg146/resources/osteoporosis-assessing-the-risk-of-fragility-fracture-35109574194373

- 2.Costa AG, Wyman A, Siris ES et al. . When, where and how osteoporosis-associated fractures occur: an analysis from the Global Longitudinal Study of Osteoporosis in Women (GLOW). PLoS ONE 2013;8:e83306 10.1371/journal.pone.0083306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Masud T, Morris RO. Epidemiology of falls. Age Ageing 2001;30(Suppl 4):3–7. 10.1093/ageing/30.suppl_4.3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ensrud KE. Epidemiology of fracture risk with advancing age. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2013;68:1236–42. 10.1093/gerona/glt092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mair FS, May CR. Thinking about the burden of treatment. BMJ 2014;349:g6680 10.1136/bmj.g6680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gallacher K, Morrison D, Jani B et al. . Uncovering treatment burden as a key concept for stroke care: a systematic review of qualitative research. PLoS Med 2013;10:e1001473 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gallacher KI, Batty GD, McLean G et al. . Stroke, multimorbidity and polypharmacy in a nationally representative sample of 1,424,378 patients in Scotland: implications for treatment burden. BMC Med 2014;12:151 10.1186/s12916-014-0151-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fried LP, Xue QL, Cappola AR et al. . Nonlinear multisystem physiological dysregulation associated with frailty in older women: implications for etiology and treatment. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2009;64:1049–57. 10.1093/gerona/glp076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Corsonello A, Pedone C, Incalzi RA. Age-related pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic changes and related risk of adverse drug reactions. Curr Med Chem 2010;17:571–84. 10.2174/092986710790416326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bowie MW, Slattum PW. Pharmacodynamics in older adults: a review. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother 2007;5:263–303. 10.1016/j.amjopharm.2007.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shi S, Mörike K, Klotz U. The clinical implications of ageing for rational drug therapy. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2008;64: 183–99. 10.1007/s00228-007-0422-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lattanzio F, Landi F, Bustacchini S et al. . Geriatric conditions and the risk of adverse drug reactions in older adults: a review. Drug Saf 2012;35(Suppl 1):55–61. 10.1007/BF03319103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jarrett PG, Rockwood K, Carver D et al. . Illness presentation in elderly patients. Arch Intern Med 1995;155:1060–4. 10.1001/archinte.1995.00430100086010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leipzig RM, Cumming RG, Tinetti ME. Drugs and falls in older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis: II. Cardiac and analgesic drugs. J Am Geriatr Soc 1999;47:40–50. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb01899.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Woolcott JC, Richardson KJ, Wiens MO et al. . Meta-analysis of the impact of 9 medication classes on falls in elderly persons. Arch Intern Med 2009;169:1952–60. 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leipzig RM, Cumming RG, Tinetti ME. Drugs and falls in older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis: I. Psychotropic drugs. J Am Geriatr Soc 1999;47:30–9. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb01898.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gillespie LD, Robertson MC, Gillespie WJ et al. . Interventions for preventing falls in older people living in the community. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009;(2):CD007146 10.1002/14651858.CD007146.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cameron ID, Gillespie LD, Robertson MC et al. . Interventions for preventing falls in older people in care facilities and hospitals. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;12:CD005465 10.1002/14651858.CD005465.pub3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang AR, Mallet L, Rochefort CM et al. . Medication-related falls in the elderly: causative factors and preventive strategies. Drugs Aging 2012;29:359–76. 10.2165/11599460-000000000-00000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dhruva SS, Redberg RF. Variations between clinical trial participants and Medicare beneficiaries in evidence used for Medicare national coverage decisions. Arch Intern Med 2008;168:136–40. 10.1001/archinternmed.2007.56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Van Spall HG, Toren A, Kiss A et al. . Eligibility criteria of randomized controlled trials published in high-impact general medical journals: a systematic sampling review. JAMA 2007;297:1233–40. 10.1001/jama.297.11.1233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beckett NS, Peters R, Fletcher AE et al. . Treatment of hypertension in patients 80 years of age or older. N Engl J Med 2008;358:1887–98. 10.1056/NEJMoa0801369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Denson AC, Mahipal A. Participation of the elderly population in clinical trials: barriers and solutions. Cancer Control 2014;21:209–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vind AB, Andersen HE, Pedersen KD et al. . Baseline and follow-up characteristics of participants and nonparticipants in a randomized clinical trial of multifactorial fall prevention in Denmark. J Am Geriatr Soc 2009;57:1844–9. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02435.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee PY, Alexander KP, Hammill BG et al. . Representation of elderly persons and women in published randomized trials of acute coronary syndromes. JAMA 2001;286:708–13. 10.1001/jama.286.6.708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heiat A, Gross CP, Krumholz HM. Representation of the elderly, women, and minorities in heart failure clinical trials. Arch Intern Med 2002;162:1682–8. 10.1001/archinte.162.15.1682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rehman HU. Under-representation of the elderly in clinical trials. Eur J Intern Med 2005;16:385–6. 10.1016/j.ejim.2005.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tinetti ME. The gap between clinical trials and the real world: extrapolating treatment effects from younger to older adults. JAMA Intern Med 2014;174:397–8. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.13283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jarvinen TL, Sievanen H, Kannus P et al. . The true cost of pharmacological disease prevention. BMJ 2011;342:d2175 10.1136/bmj.d2175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schmidt M, Pedersen L, Sørensen HT. The Danish Civil Registration System as a tool in epidemiology. Eur J Epidemiol 2014;29:541–9. 10.1007/s10654-014-9930-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lynge E, Sandegaard JL, Rebolj M. The Danish National Patient Register. Scand J Public Health 2011;39(7 Suppl):30–3. 10.1177/1403494811401482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kildemoes HW, Sørensen HT, Hallas J. The Danish National Prescription Registry. Scand J Public Health 2011;39(7 Suppl):38–41. 10.1177/1403494810394717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jørgensen TS, Hansen AH, Sahlberg M et al. . Falls and comorbidity: the pathway to fractures. Scand J Public Health 2014;42:287–94. 10.1177/1403494813516831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kinsella S, Moran S, Sullivan MO et al. . Hyponatremia independent of osteoporosis is associated with fracture occurrence. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2010;5:275–80. 10.2215/CJN.06120809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Renneboog B, Musch W, Vandemergel X et al. . Mild chronic hyponatremia is associated with falls, unsteadiness, and attention deficits. Am J Med 2006;119:71.e1–8. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.09.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rejnmark L, Vestergaard P, Mosekilde L. Reduced fracture risk in users of thiazide diuretics. Calcif Tissue Int 2005;76:167–75. 10.1007/s00223-004-0084-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Deandrea S, Lucenteforte E, Bravi F et al. . Risk factors for falls in community-dwelling older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Epidemiology 2010;21:658–68. 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181e89905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Butt DA, Mamdani M, Austin PC et al. . The risk of hip fracture after initiating antihypertensive drugs in the elderly. Arch Intern Med 2012;172:1739–44. 10.1001/2013.jamainternmed.469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Butt DA, Mamdani M, Austin PC et al. . The risk of falls on initiation of antihypertensive drugs in the elderly. Osteoporos Int 2013;24:2649–57. 10.1007/s00198-013-2369-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gribbin J, Hubbard R, Gladman J et al. . Risk of falls associated with antihypertensive medication: Self-controlled case series. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2011;20:879–84. 10.1002/pds.2176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Berry SD, Zhu Y, Choi H et al. . Diuretic initiation and the acute risk of hip fracture. Osteoporos Int 2013;24:689–95. 10.1007/s00198-012-2053-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tinetti ME, Han L, Lee DS et al. . Antihypertensive medications and serious fall injuries in a nationally representative sample of older adults. JAMA Intern Med 2014;174:588–95. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.14764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Freeman JV, Yang J, Sung SH et al. . Effectiveness and safety of digoxin among contemporary adults with incident systolic heart failure. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2013;6: 525–33. 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.111.000079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]