Abstract

Objective

To compare the efficacy and safety of incobotulinumtoxinA with conventional antispastic therapy for poststroke arm spasticity in routine clinical practice over a 1-year period.

Design

Prospective, non-interventional, open-label, parallel-group study.

Setting

47 centres in Germany.

Participants

Patients with poststroke arm spasticity; 108 receiving incobotulinumtoxinA, 110 conventional therapy.

Intervention

Conventional antispastic treatment including oral antispastic medications, physiotherapy and occupational therapy or 3-monthly incobotulinumtoxinA injections plus conventional therapy if required.

Main outcome measures

The main outcome measure was changes in muscle tone (Ashworth Scale) over the 1-year treatment period. Changes in functional disability (Disability Assessment Scale) and quality of life (Short-Form-12 Health Survey) were additionally assessed. Ratings for therapy outcome (Goal Attainment Scale), and efficacy and tolerability of treatment (Global Clinical Impression Scale) were also obtained.

Results

Muscle tone improved for all spasticity patterns with the Ashworth Scale responder rates between 63% and 86% (incobotulinumtoxinA) and 16–27% (conventional therapy). Median improvement in functional disability was –1.0 (incobotulinumtoxinA) and 0.0 (conventional measures) for all domains. Treatment goals were attained by 93% of incobotulinumtoxinA patients and 30% of patients under conventional therapy. Most physicians (93%) and patients (90%) rated efficacy as good or very good under incobotulinumtoxinA; the proportions were much lower under conventional therapy (36% and 37%). Tolerability under incobotulinumtoxinA was considered good or very good by 99% of physicians and patients (76% and 66%, respectively, under conventional therapy). Quality of life under incobotulinumtoxinA improved by 8.0 (physical score) and 10.8 (mental score) and by 0.8 and 5.7, respectively, under conventional therapy.

Conclusions

IncobotulinumtoxinA combined with rehabilitation and oral medication produces a much more robust improvement in all aspects of arm spasticity than conventional antispastic treatment. Effects are stable over a period of 1 year, whereas adverse effects are negligible. IncobotulinumtoxinA should be considered the treatment of choice for poststroke arm spasticity.

Keywords: muscle spasticity; botulinum toxins, type A; outcome assessments

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the largest study of its kind carried out in Germany.

There is a potential bias because of the 100% participation of specialist physicians in the incobotulinumtoxinA arm compared with only 11% in the conventional therapy arm: their greater expertise in the treatment of spasticity compared with general practitioners provided more patients with additional antispastic measures which might have increased the benefits of botulinum toxin treatment.

The non-interventional study design reflects the real-world healthcare situation in Germany in the treatment of poststroke spasticity.

Introduction

Spasticity is a common complication of motor stroke. It is often more pronounced in arm muscles than in leg muscles and occurs in approximately 30% of patients suffering from motor stroke.1 Patients with poststroke spasticity often experience marked functional impairments which may result in restrictions in their daily routine, in dependence on assistance from family and/or caregivers and in impaired social participation.2 This may lead to loss of self-esteem, poor body image, depression and a diminished quality of life. Conventional treatment options are numerous; efficacy, however, is limited. For adult upper limb spasticity, the use of botulinum toxin (BT) therapy is supported by various guidelines, expert opinions and a recent evidence-based review.2–6 However, an analysis of claims data from a large statutory German health insurance fund found that none in the cohort received BT treatment for poststroke spasticity.7 BT therapy for spasticity thus seems to have so far not been implemented in routine healthcare practice in Germany and cannot as yet be considered a conventional treatment approach.

Our study assessed the effectiveness and safety of different therapeutic measures for arm spasticity after stroke in routine clinical practice in Germany over a 1-year period and compared the administration of conventional measures including oral antispastic medications, physiotherapy and occupational therapy to BT therapy. The primary assessment parameter was the change in muscle tone over the treatment period. Additionally, changes in functional disability and quality of life were assessed, and physicians and patients rated goal attainment and treatment efficacy and safety.

Methods

Study design

This study was based on a prospective, non-interventional, open-label, multicentre, parallel-group design. In conventional therapy (CON) arm, patients received conventional antispastic treatment including oral antispastic medications, physiotherapy and occupational therapy at the physician’s discretion. In incobotulinumtoxinA (INCO) arm, patients received INCO (Xeomin, Merz Pharmaceuticals, Frankfurt/Main, Germany8) and additionally conventional treatment, if required. General practitioners and specialists, including neurologists and rehabilitation specialists, were invited to participate in this study. Prior to initiation of the study, they had to choose which spasticity treatment they wanted to administer and were thus included in the CON or INCO treatment arm. All treatment decisions were made before inclusion of the patient in the study. IncobotulinumtoxinA was applied according to the physician’s decision with respect to dose and muscles injected. Any kind of antispastic treatment and procedures as well as medications was documented. Participating physicians were asked to document the first four eligible patients presenting at their practice using standardised report forms. Up to 16 patients could be included per site.

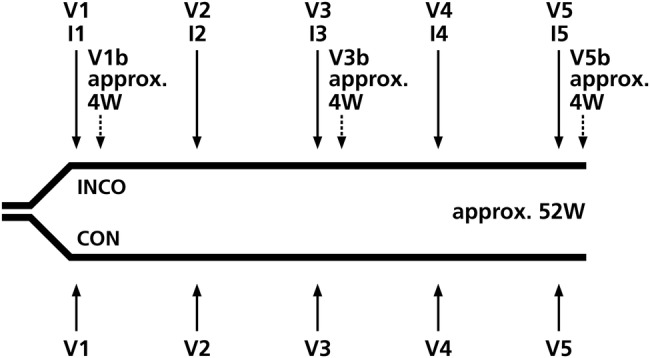

The patient flow in this study is shown in figure 1. At baseline visit (V1), all patients were prescribed their respective antispastic treatment and INCO patients received their first INCO injections. Patients then presented every 3 months for follow-ups at visits V2 (month 3), V3 (month 6), V4 (month 9) and V5 (month 12) when INCO patients received their subsequent INCO injections. To document maximum INCO efficacy, INCO patients were additionally evaluated 4 weeks after V1, V3 and V5, respectively, at V1b, V3b and V5b.

Figure 1.

Study design (CON, patients receiving conventional therapy; I, injection; INCO, patients receiving incobotulinumtoxinA; V, visit; W, weeks).

The study was conducted by the Institute of Empirical Health Economics, Burscheid, Germany at 47 centres in Germany between April 2012 and May 2014 in accordance with section 4, subsection 23 and section 67, subsection 6 of the Medicinal Products Act of the Federal Republic of Germany. All participating patients gave written informed consent.

Patients

Inclusion criteria included diagnosis of poststroke arm spasticity, indication for antispastic treatment, adult age (at least 18 years old), ability to read and to understand the study information material and to complete the patient questionnaire. Exclusion criteria included simultaneous participation in another spasticity trial, application of BT for less than 12 weeks before inclusion in this study, hypersensitivity to BT drugs or their individual contents, infection at the intended injection site and presence of neuromuscular disorders such as myasthenia gravis and Lambert-Eaton syndrome.

Parameters

As a primary assessment parameter, changes in muscle tone were evaluated with a responder analysis for all clinical patterns of upper limb spasticity. Muscle tone was evaluated with the Ashworth Scale (AS; grade 0: no increase in muscle tone; grade 1: slight increase in muscle tone, giving a catch when the affected limb is moved in flexion or extension; grade 2: a more marked increase in muscle tone, but limb easily flexed; grade 3: considerable increase in muscle tone, passive movement difficult; grade 4: limb rigid in flexion or extension).9 A reduction by at least one point was considered clinically meaningful. Patients with a clinically meaningful response were considered responders.

Functional disability was rated by the Disability Assessment Scale (DAS) for the four domains hygiene, getting dressed, limb position and pain (grade 0: no disability; grade 1: mild disability; grade 2: moderate disability; grade 3: severe disability).10 A reduction by at least one point was considered clinically meaningful.

Therapy outcome was documented by a simplified version of the Goal Attainment Scale (GAS).11 During each visit, patients and physicians chose three treatment goals (priority rating 1, 2 and 3) that they wanted to attain over the next 3 months from a list of 17 items. For documentation, physicians only documented if the treatment goal was attained or not. The list of goals is shown in box 1.

Box 1. List of treatment goals. At each visit, patients chose three treatment goals they wanted to attain until the next visit.

Pain relief

Reduction of frequency of muscle spasms

Reduction of involuntary movements

Improvement of dexterity

Improvement of self-care: personal hygiene

Improvement of self-care: eating

Improvement of sexual activity

Prevention of contractures and deformation

Improvement of self-care: hand hygiene

Improved body image

Improved fit of clothing

Facilitation of rehabilitation

Reduction of use of systemic medication in antispasticity treatment

Reduction of daily care measures

Reduction of care measures regarding movements

Easier application of (arm) splints and extended usage

Reduction/prevention of surgical interventions

Global Clinical Impression (GCI) of effectiveness and tolerability of the respective treatment was rated by patients and physicians separately at the end of the observation period as very good, good, satisfactory, poor or very poor.

Quality of life was rated by the patients with the SF-12v2 Health Survey, a shorter version of the Short-Form-36 (SF-36) Health Survey.12 The 12 SF-12 Health Survey items are subsumed under the dimensions ‘mental health’ and ‘physical health’. Possible scores in both domains range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating a higher quality of life.

To assess safety, physicians monitored the occurrence of adverse events (AEs) and serious adverse events (SAEs) during the entire 1-year observation period.

Statistical analysis

Documented data were processed with single data entry using Oracle Database Online Documentation 11 g Release 2 (Oracle, Redwood Shores, California, USA). All data were checked for completeness, consistency and plausibility. The efficacy analysis included all patients in INCO or CON for at least 3 months. Except for the primary parameter, all analyses were descriptive and exploratory. Missing data were not imputed. End of observation time point was V5 for CON and V5b for INCO. The primary study parameter (changes in AS) was evaluated with a responder analysis for all clinical patterns of upper limb spasticity. All patients with baseline AS≥1 were included in the respective analysis. Treatment response was defined as AS improvement ≥1 from baseline to end of the observation period. Fisher’s exact test was used for comparison of treatment response between INCO and CON. The influence on treatment response regarding the independent variables gender, height, weight, body mass index, age, time since stroke, duration of spasticity, treatment arm and baseline AS (for the investigated clinical patterns) was tested using logistic regression analyses. p Values for DAS changes over the course of the study were calculated with the Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test. SF-12 Health Survey changes were evaluated using the physical and the mental component score. Scores were calculated using a fixed algorithm and were based on the analysis manual of the German norm from 1994.13 Comparisons of SF-12 Health Survey scores between baseline and end of observation employed the paired Student t test. All patients receiving antispastic treatment at least once during the observation period were included in the tolerability analysis. AEs were encoded with the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities V.13.0 (MedDRA). The χ2 test was used to compare AE incidences between the treatment arms.

Results

Demographics

Table 1 summarises the baseline characteristics of the two study groups; 108 patients were included in the INCO group at 21 study sites, as against 110 patients in the CON group at 26 study sites.

Table 1.

Demographic and baseline characteristics of the study population at V1

| INCO (n=108) | CON (n=110) | |

|---|---|---|

| Male gender (n) | 58 (53.7%) | 70 (63.6%) |

| Female gender (n) | 50 (46.3%) | 40 (36.4%) |

| Age (years) | 61.7±12.9 | 67.8±12.7 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 26.7±4.1 | 27.7±4.8 |

| Time since stroke (years) | 7.5±5.8 | 5.3±5.1 |

| Type of stroke | ||

| Ischaemic | 51 (47.2%) | 43 (39.1%) |

| Haemorrhagic | 16 (14.8%) | 7 (6.4%) |

| Others | 21 (19.4%) | 29 (26.4%) |

| No data | 20 (18.5%) | 31 (28.2%) |

| Duration of upper limb spasticity (years) | 6.6±6.3 | 4.9±5.4 |

| Previous antispastic medication (n) | 85 (78.7%) | 65 (59.1%) |

| Previous botulinum toxin therapy (n) | 67 (62%) | 0 |

Data are mean±SD or number of patients (%).

CON, patients receiving conventional therapy; INCO, patients receiving incobotulinumtoxinA.

Eighty-nine per cent of the patients completed the observation period. Fifty-seven per cent of all patients presented with combined arm and leg spasticity; 54% (INCO) and 32% (CON) had arm spasticity only. The most frequent clinical spasticity patterns were flexed elbow (86%), flexed wrist (72%), shoulder adduction/internal rotation (71%), clenched fist (71%) and forearm pronation (71%). As shown in table 1, INCO patients had suffered from spasticity for a longer period of time with a higher proportion of patients with AS≥2 in most of the clinical patterns at baseline than CON patients (table 2).

Table 2.

Clinical patterns of arm spasticity in patients with a baseline severity in Ashworth Score ≥2 at V1

| INCO (n=108) | CON (n=110) | |

|---|---|---|

| Flexed elbow | 91 (84.3%) | 59 (53.6%) |

| Clenched fist | 77 (71.3%) | 40 (36.4%) |

| Flexed wrist | 67 (62.1%) | 58 (52.7%) |

| Pronated forearm | 63 (58.3%) | 49 (44.6%) |

| Thumb-in-palm | 53 (49.1%) | 43 (39.1%) |

| Shoulder adduction/internal arm rotation | 52 (48.2%) | 40 (36.3%) |

| Shoulder abduction | 36 (33.3%) | 45 (40.9%) |

| Shoulder elevation | 32 (29.6%) | 46 (41.8%) |

| Intrinsic-plus hand | 20 (18.5%) | 33 (30.0%) |

Data are number of patients (%). Multiple responses permitted.

CON, patients receiving conventional therapy; INCO, patients receiving incobotulinumtoxinA.

In total, 78% of INCO patients and 87% of CON patients had concomitant diseases, mainly vascular disorders (87%). Prior to study entry, antispastic medications were documented for 69% of all patients. All INCO patients were treated by specialists including neurologists and rehabilitation specialists. In CON, 13% of the patients were treated by specialists. All general practitioners participating in this study chose conventional antispastic treatment.

Antispastic treatment

In the INCO group, 38% of the patients were BT naïve. The remainder had received their last BT injection 15.7 weeks (median, range 12–171 weeks) before inclusion in the study. The minimum latency allowed in this study was 12 weeks. INCO doses were 215±114 MU (mouse units; mean±SD) at V1 and 268.7±155 MU at V5. The most frequently injected muscles were flexor digitorum profundus, flexor digitorum superficialis and biceps brachii. At V1, 35% of INCO patients were receiving oral antispastic medication, mainly baclofen (63%) and tolperisone (21%). At V5, this percentage had dropped to 22%. In the CON group, 34% of the patients were receiving oral antispastic medication at V1, mainly baclofen (62%), tetrazepam (16%) and tolperisone (11%). At V5, this percentage had dropped to 33%. Non-pharmacological antispasticity treatment is shown in table 3.

Table 3.

Number of patients receiving non-pharmacological antispasticity treatment

| INCO |

CON |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First 3 study months (n=108) | Last 3 study months (n=94) | First 3 study months (n=110) | Last 3 study months (n=84) | |

| Physiotherapy | 60 (56%) | 51 (54%) | 68 (62%) | 52 (62%) |

| Occupational therapy | 43 (40%) | 44 (47%) | 15 (14%) | 8 (10%) |

| Speech therapy | 10 (9%) | 9 (9%) | 5 (5%) | 4 (5%) |

| Others | 3 (3%) | 4 (4%) | 3 (3%) | 1 (1%) |

Data are number of patients (%). Multiple responses permitted.

CON, patients receiving conventional therapy; INCO, patients receiving incobotulinumtoxinA.

In the INCO group, 56% of patients received physiotherapy during the first three study months and 54% during the last three study months. Under CON, these were 62% and 62% of the patients, respectively. Occupational therapy was prescribed for 40% of INCO patients during the first three study months and 47% during the last three study months compared with 14% and 10%, respectively, under conventional antispastic therapy. In the INCO group, 9% of patients received speech therapy during the first three study months, as against 9% during the last three study months (5% of CON patients for both periods). The intensity of the different therapies was not documented.

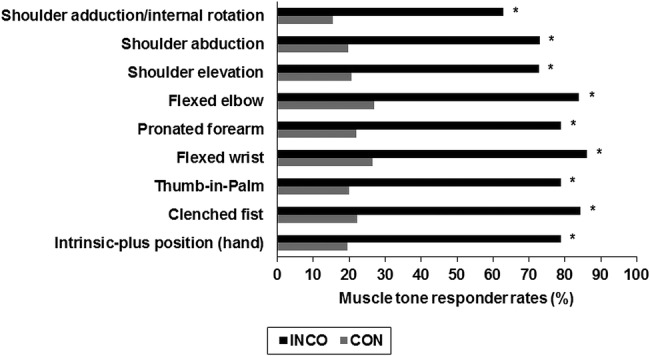

Muscle tone

Figure 2 shows the reduction of muscle tone in INCO and CON as measured by the percentage of treatment responders on the AS at V1 and V5/V5b. For all nine clinical patterns of arm spasticity, AS responder rates were significantly higher in the INCO group than in the CON group (p<0.01). Logistic regression analyses indicated no relevant influence of baseline characteristics, treatment arm or AS at baseline on the treatment response.

Figure 2.

Improvement of muscle tone from V1 to V5/V5b in the incobotulinumtoxinA group (INCO) and in patients receiving conventional therapy (CON) for all spasticity patterns as shown by the percentage of treatment responders. Treatment response was defined as an Ashworth Score improvement of ≥1. *p<0.01 (Fisher's exact test).

Functional disability

Table 4 shows the reduction of functional disability in INCO and CON as measured by DAS at V1 and V5/V5b.

Table 4.

Improvement of disability as measured by the Disability Assessment Scale from V1 to V5/V5b

| Domain | INCO (n=92) | p Value | CON (n=83) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hygiene | –0.7±1.1 | <0.01 | –0.2±0.8 | <0.01 |

| Dressing | –0.8±1.0 | <0.01 | 0.0±0.6 | 0.85 |

| Limb position | –1.0±0.9 | <0.01 | –0.3±0.7 | <0.01 |

| Pain | –0.8±0.9 | <0.01 | –0.1±0.9 | 0.44 |

Data are mean changes±SD. Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test for p values.

CON, patients receiving conventional therapy; INCO, patients receiving incobotulinumtoxinA.

In the INCO group, functional disability significantly improved from V1 to V5b in all four domains. For hygiene, DAS improvement was –0.7±1.1 (p<0.01), for getting dressed –0.8±1.0 (p<0.01), for limb position –1.0±0.9 (p<0.01) and for pain –0.8±0.9 (p<0.01) (mean changes±SD from baseline to study end). The median for each single domain was –1.0. In the CON group, DAS improvement for hygiene was –0.2±0.8 (p<0.01), for getting dressed 0.0±0.6 (p=0.85), for limb position –0.3±0.7 (p<0.01) and for pain –0.1±0.9 (p=0.44). Median improvements for all four domains in CON were 0.0.

Therapy outcome

In the INCO group, the most commonly chosen top priority treatment goals at V1 were alleviation of pain (35%) and improvement of finger dexterity (17%); at V5, 29% and 11% of patients, respectively, had chosen these goals. Overall, 93% of INCO patients achieved their top priority treatment goal. Alleviation of pain was attained in all INCO patients, and improvement of finger dexterity in 67%. In the CON group, top priority treatment goals at V1 were improvement of finger dexterity (32%) and alleviation of pain (26%). At the final visit, 11% attained improvement of finger dexterity, whereas 48% attained alleviation of pain. Overall, treatment goals with top priority in this group were achieved in 30%.

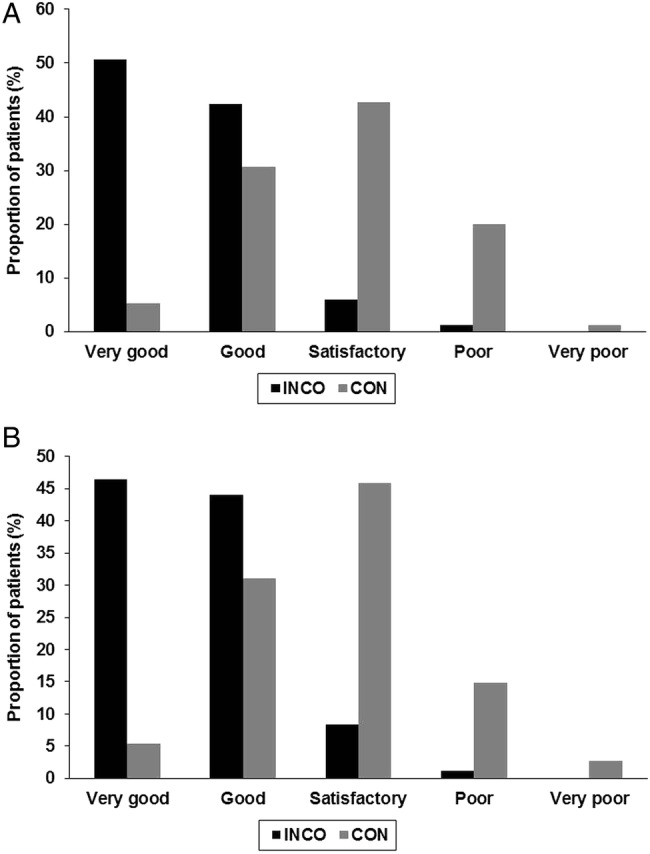

Global outcome

In the INCO group, 93% of the physicians and 90% of the patients rated the therapeutic efficacy as ‘good’ or ‘very good’, as against 36% and 37%, respectively, in the CON group (figure 3A,B). Tolerability of INCO treatment was rated as ‘very good’ by 92% of both physicians and patients; 7% of both physicians and patients considered it as ‘good’. In the CON group, 13% of the physicians and 18% of the patients rated tolerability as ‘very good’, whereas 63% of the physicians and 49% of the patients rated it as ‘good’.

Figure 3.

Improvement of Global Clinical Impression from V1 to V5/V5b. (A) Physician assessment (n=85 in INCO, n=75 in CON). (B) Patient assessment (n=84 in INCO, n=74 in CON) (CON, patients receiving conventional therapy; INCO, patients receiving incobotulinumtoxinA).

Quality of life

In the INCO group, the physical score increased from 33.6±7.8 (V1) to 42.0±8.4 (V5b) (p<0.01), and the mental score from 42.8±14.8 (V1) to 52.9±11.0 (V5b) (p<0.01) (mean values±SD). In the CON group, the mental score increased from 37.8±14.4 (V1) to 41.4±12.5 (V5) (p=0.02), and the physical score from 35.5±9.3 (V1) to 36.3±8.1 (V5) (p=0.43).

Safety

Safety analysis was based on data of 218 patients. Forty-nine patients (22%) experienced 81 AEs. Twenty AEs occurred in 8% of INCO patients and 21 SAEs in 16% of INCO patients, 18 AEs in 10% of CON patients and 22 SAEs in 15% of CON patients. There were no significant differences between the groups (p=0.439 for AEs, p=0.452 for SAEs). Of the 38 AEs, 79% were mild-to-moderate, 13% severe. Of the 43 SAEs, 19% were mild-to-moderate, 67% severe (INCO 48%, CON 87%). All AEs and SAEs but one AE were considered not related to treatment. A 72-year-old male INCO patient reported a mild loss of strength in his left arm. Six patients died during the study period, all in the CON group. None of the deaths were treatment related. Twenty-five patients (15 INCO, 10 CON) prematurely discontinued treatment. Physicians decided to withdraw INCO treatment in three cases (sufficient improvement of condition for 2 patients, lack of effectiveness for 1 patient). There was no treatment discontinuation owing to tolerability problems in the INCO group.

Discussion

This study presents the data of a long-term, multicentre study on the efficacy and safety of INCO versus conventional antispastic treatment alone in patients with poststroke arm spasticity. With 218 patients included in 47 centres in Germany, this is the largest study of its kind.

Spasticity patterns included nine different patterns of arm spasticity among others: elbow flexion, wrist flexion, shoulder adduction/internal rotation, finger flexion and forearm pronation. Conventional antispastic treatment included mainly baclofen, tetrazepam and tolperisone accompanied by physiotherapy, occupational therapy and speech therapy. BT treatment consisted of 215±114 MU INCO at the beginning and 268.7±155 MU at the end of the study accompanied by mainly baclofen, tolperisone, physiotherapy, occupational therapy and speech therapy. BT dose increase is more likely reflecting dose optimisation to improve efficacy rather than compensation for BT antibody-induced efficacy loss.14 Thirty-eight per cent of patients were BT naïve at study entry. Additional consumption of antispastic drugs was reduced in the INCO group, reflecting BT efficacy.

Regular INCO injections over a 1-year period resulted in sustained improvements in muscle tone and functional disability. Between 63% and 86% of the patients depending on the investigated clinical pattern were treatment responders as measured with the AS, and functional disability significantly improved in all four DAS domains. INCO was well tolerated and patients and physicians rated effectiveness and tolerability of the treatment very positively. The treatment was more effective than conventional antispastic therapy; the improvements in muscle tone in particular were more pronounced with a significant difference in responder rates for all nine clinical patterns. Under INCO, functional disability improved in all four domains with a median of 1.0, which is considered a clinically meaningful change.10 15 Improvements under conventional treatment were 0.0, that is, nil.

At study end, 93% of the patients receiving INCO attained their top priority treatment goal; this was only achieved in 30% of patients under CON. Relief from muscle pain is a common treatment goal for patients both in the early and late stages of upper limb spasticity16; a significant decrease in pain ratings was previously shown under long-term BT treatment.17 18 Alleviation of pain was the most frequent top priority treatment goal under INCO and the second most frequent under CON. All INCO patients but only 48% of patients under conventional antispastic treatment reached that goal. Our results demonstrate a significant reduction in pain intensity as well as in functional impairment due to spasticity-related pain in the course of INCO treatment.

Mental quality of life scores improved under both treatments, but improvement in the physical component score was only observed in INCO patients. Spasticity has a negative impact on the quality of life of stroke survivors, in particular on the physical domain. According to a study published in 2012, US stroke survivors with spasticity had significantly lower SF-12 Health Survey physical domain scores at 3 months and 1 year following stroke than patients with stroke without spasticity.19 Increasing functional disability in the DAS domains hygiene, dressing and pain in upper limb spasticity was significantly associated with diminishing health-related quality of life measured by the EuroQol 5 questionnaire.20 At the start of our study, patients had physical and mental domain scores of 34.5 and 40.5, respectively, which were markedly lower than the scores for the German population norm with 49.6 and 52.3, respectively.

Our results confirm results from a randomised placebo-controlled INCO trial21 and a previous long-term open-label study.22 They are in line with long-term investigations of other BT drugs in the treatment of spasticity of various aetiologies including stroke.17 23 24 Underlying paresis in spasticity should be addressed by additional physiotherapy.4 25 Successful treatment of spasticity requires an individualised treatment approach and should be managed by a multidisciplinary team.2 4

A non-interventional study design evaluates the administration of medications under routine clinical practice conditions (‘real-life’ data) and complements randomised controlled trials with a predefined protocol and strict inclusion/exclusion criteria. Treatment decisions are solely at the discretion of the participating physicians and the decision how to treat a particular patient (in this study with CON or with INCO) must be made before inclusion of the patient in the study. The markedly greater improvements in muscle tone and functional ability under INCO compared with CON in this study thus reflect outcomes of day-to-day treatment decisions in general and specialist practices. It should, however, be noted that the 100% participation of specialist physicians in the INCO arm compared with only 11% in the CON arm might have introduced a bias. Physicians in Germany do not require an official certificate to offer BT treatment; however, special training is necessary to gain sufficient expertise. The greater expertise of the specialists in the treatment of spasticity compared with general practitioners provided more patients with additional non-pharmacological antispastic measures which might have increased the benefits of BT treatment. The intensity of the different procedures applied was not documented and cannot therefore be discussed. However, patients in the INCO arm received overall better care than patients under CON. Although the prescription of physiotherapy was similar between the groups, 47% of patients under INCO received additional occupational therapy in the last three study months compared with only 10% under CON.

In summary, treatment of upper limb spasticity over a 1-year treatment period in routine clinical practice was more effective in the INCO arm than in the CON arm in the assessments performed in this study. Effective poststroke spasticity treatment requires specialised, individualised and multidisciplinary treatment approaches. Lack of information about adequate or additional treatment options, the limited number of specialised physicians/BT therapy centres, and inadequate reimbursement of physicians offering BT treatment should be considered by potential stakeholders in the German healthcare system to improve spasticity treatment.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all participating physicians. Writing assistance and editorial assistance was provided by Elke Grosselindemann and paid for by the sponsor.

Footnotes

Contributors: DD contributed to the study conception and data interpretation. RR contributed to the study conception, data acquisition, data analysis and data interpretation. FK contributed to the data acquisition, data analysis and data interpretation. NS and JL-B contributed to the study conception, data analysis and data interpretation. All the authors contributed to the critical revision of the manuscript, and gave approval of the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This study was supported by Merz Pharmaceuticals GmbH, Frankfurt/Main, Germany.

Disclaimer: The sponsor was involved in the study design, analysis and interpretation of the data, in the writing of the report and in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Competing interests: DD received compensation for consultations by Allergan, Bayer, Abbvie, IAB-Arbeitskreis Bewegungsstörungen, Merz Pharmaceuticals, Ipsen and Syntaxin. NS and JL-B are employees of Merz Pharmaceuticals GmbH, Frankfurt/Main, Germany. RR and FK are employees of Institute of Empirical Health Economics, Burscheid, Germany.

Ethics approval: Ethics committee of Hannover Medical School, Germany.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Adib Saberi F, Dressler D. Muscle hyperactivity after stroke: long term follow up of prevalence and current treatment [abstract]. Mov Disord 2009;24(Suppl 1):S449. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wissel J, Ward AB, Erztgaard P et al. European consensus table on the use of botulinum toxin type A in adult spasticity. J Rehabil Med 2009;41:13–25. 10.2340/16501977-0303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Simpson DM, Gracies JM, Graham HK et al. Assessment: botulinum neurotoxin for the treatment of spasticity (an evidence-based review): report of the Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology 2008;70:1691–8. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000311391.00944.c4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liepert J. Rehabilitation. Treatment of the spastic syndrome [in German]. In: Diener HC, Weimar C, eds. Guidelines for diagnostics and therapy in neurology. Stuttgart: Thieme-Verlag, 2012;1062–71. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Winter T, Wissel J. Treatment of spasticity after stroke [in German]. Neurol Rehabil 2013;19:285–309. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Esquenazi A, Albanese A, Chancellor MB et al. Evidence-based review and assessment of botulinum neurotoxin for the treatment of adult spasticity in the upper motor neuron syndrome. Toxicon 2013;67:115–28. 10.1016/j.toxicon.2012.11.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Egen-Lappe V, Köster I, Schubert I. Incidence estimate and guideline-oriented treatment for poststroke spasticity: an analysis based on German statutory health insurance data. Int J Gen Med 2013;6:135–44. 10.2147/IJGM.S36030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dressler D. Five-year experience with incobotulinumtoxinA (Xeomin®): the first botulinum toxin drug free of complexing proteins. Eur J Neurol 2012;19:385–9. 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2011.03559.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ashworth B. Preliminary trial of carisoprodol in multiple sclerosis. Practitioner 1964;192:540–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brashear A, Zafonte R, Corcoran M et al. Inter- and intrarater reliability of the Ashworth Scale and the Disability Assessment Scale in patients with upper-limb poststroke spasticity. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2002;83:1349–54. 10.1053/apmr.2002.35474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kiresuk TJ, Sherman RE. Goal attainment scaling: a general method for evaluating comprehensive community mental health programs. Community Ment Health J 1968;4:443–53. 10.1007/BF01530764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ware J Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care 1996;34:220–33. 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gandek B, Ware JE, Aaronson NK et al. Cross-validation of item selection and scoring for the SF-12 health survey in nine countries: results from the IQOLA project. International Quality of Life Assessment. J Clin Epidemiol 1998;51:1171–8. 10.1016/S0895-4356(98)00109-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dressler D, Tacik P, Adib Saberi F. Botulinum toxin therapy of cervical dystonia: comparing onabotulinumtoxinA (Botox®) and incobotulinumtoxinA (Xeomin®). J Neural Transm 2014;121:29–31. 10.1007/s00702-013-1076-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brashear A, Gordon MF, Elovic E et al. Intramuscular injection of botulinum toxin for the treatment of wrist and finger spasticity after a stroke. N Engl J Med 2002;347:395–400. 10.1056/NEJMoa011892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bakheit AM, Zakine B, Maisonobe P et al. The profile of patients and current practice of treatment of upper limb muscle spasticity with botulinum toxin type A: an international survey. Int J Rehabil Res 2010;33:199–204. 10.1097/MRR.0b013e328332f5e0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schramm A, Ndayisaba JP, Auf dem Brinke M et al. Spasticity treatment with onabotulinumtoxin A: data from a prospective German real-life patient registry. J Neural Transm 2014;121:521–30. 10.1007/s00702-013-1145-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shaw LC, Price CI, van Wijck FM et al. Botulinum Toxin for the Upper Limb after Stroke (BoTULS) trial: effect on impairment, activity limitation, and pain. Stroke 2011;42:1371–9. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.582197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gillard P, Sucharew H, Varon S et al. The negative impact of spasticity on the health-related quality of life of stroke survivors [abstract]. Stroke 2012;43:A2472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Doan QV, Brashear A, Gillard PJ et al. Relationship between disability and health-related quality of life and caregiver burden in patients with upper limb poststroke spasticity. PM R 2012;4:4–10. 10.1016/j.pmrj.2011.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kañovský P, Slawek J, Denes Z et al. Efficacy and safety of botulinum neurotoxin NT 201 in post-stroke upper limb spasticity. Clin Neuropharmacol 2009;32:259–65. 10.1097/WNF.0b013e3181b13308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kanovský P, Slawek J, Denes Z et al. Efficacy and safety of treatment with incobotulinumtoxinA (botulinum neurotoxin type A free from complexing proteins; NT 201) in post-stroke upper limb spasticity. J Rehabil Med 2011;43:486–92. 10.2340/16501977-0796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Elovic EP, Brashear A, Kaelin D et al. Repeated treatments with botulinum toxin type A produce sustained decreases in the limitations associated with focal upper-limb poststroke spasticity for caregivers and patients. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2008;89:799–806. 10.1016/j.apmr.2008.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mohammadi B, Balouch SA, Dengler R et al. Long-term treatment of spasticity with botulinum toxin type A: an analysis of 1221 treatments in 137 patients. Neurol Res 2010;32:309–13. 10.1179/016164109X12478302362734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ward AB, Wissel J, Borg J et al. Functional goal achievement in poststroke spasticity patients: the BOTOX® economic spasticity trial (BEST). J Rehabil Med 2014;46:504–13. 10.2340/16501977-1817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]