Abstract

Human milk oligosaccharides (HMOs) are considered to play a key role in establishing and maintaining the infant gut microbiota. Lacto-N-triose forms part of both type 1 and type 2 HMOs and also of the glycan moieties of glycoproteins. Upstream of the previously characterized gene cluster involved in lacto-N-biose and galacto-N-biose metabolism from Lactobacillus casei BL23, there are two genes, bnaG and manA, encoding a β-N-acetylglucosaminidase precursor and a mannose-6-phosphate isomerase, respectively. In this work, we show that L. casei is able to grow in the presence of lacto-N-triose as a carbon source. Inactivation of bnaG abolished the growth of L. casei on this oligosaccharide, demonstrating that BnaG is involved in its metabolism. Interestingly, whole cells of a bnaG mutant were totally devoid of β-N-acetylglucosaminidase activity, suggesting that BnaG is an extracellular wall-attached enzyme. In addition to hydrolyzing lacto-N-triose into N-acetylglucosamine and lactose, the purified BnaG enzyme also catalyzed the hydrolysis of 3′-N-acetylglucosaminyl-mannose and 3′-N-acetylgalactosaminyl-galactose. L. casei can be cultured in the presence of 3′-N-acetylglucosaminyl-mannose as a carbon source, but, curiously, the bnaG mutant strain was not impaired in its utilization. These results indicate that the assimilation of 3′-N-acetylglucosaminyl-mannose is independent of BnaG. Enzyme activity and growth analysis with a manA-knockout mutant showed that ManA is involved in the utilization of the mannose moiety of 3′-N-acetylglucosaminyl-mannose. Here we describe the physiological role of a β-N-acetylglucosaminidase in lactobacilli, and it supports the metabolic adaptation of L. casei to the N-acetylglucosaminide-rich gut niche.

INTRODUCTION

Glycans in human milk are present as free oligosaccharides or conjugated to proteins and lipids (1, 2), and they have been proposed to directly influence the composition of the infant gut microbiota (3, 4). Furthermore, the free human milk oligosaccharides (HMOs), the third largest solid component in milk, act as prebiotics to promote colonization by beneficial bacterial species (5, 6). HMOs contain a lactose moiety (Galβ1-4Glc) at their reducing end, which is elongated by β1,3-linked lacto-N-biose units (Galβ1-3GlcNAc) to give the type 1 HMOs, including lacto-N-tetraose (Galβ1-3GlcNAcβ1-3Galβ1-4Glc), or by β1,3/6-linked N-acetyllactosamine units (Galβ1-4GlcNAc) to give the type 2 HMOs, such as lacto-N-neotetraose (Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-3Galβ1-4Glc). Further elongation of these core structures is made by the addition of fucose and sialic acid residues (1). Both types of HMOs contain a lacto-N-triose unit (GlcNAcβ1-3Galβ1-4Glc), highlighting the importance of this trisaccharide in the total pool of HMOs. In addition, lacto-N-triose and other N-acetylhexosaminyl-oligosaccharides also form part of the structure of glycans conjugated to proteins and lipids present in human milk. The carbohydrate moieties of these molecules also have a prebiotic role, and besides the monosaccharides described above for HMOs, they also contain N-acetylgalactosamine (GalNAc) and mannose (2).

Species belonging to the genera Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus are found as part of the gastrointestinal microbiota of infants (7–9). Specific Bifidobacterium strains are efficient consumers of HMOs (10), which is in agreement with the presence in these strains of a large number of conserved genes with the predicted capacity to hydrolyze those complex glycan structures (11). This is the case for genes encoding enzymes from glycoside hydrolase family 20 (GH20), which comprises lacto-N-biosidases (EC 3.2.1.140) and β-N-acetylhexosaminidases (EC 3.2.1.52). They are endoglycosidases, like the lacto-N-biosidase from Bifidobacterium bifidum, which degrades lacto-N-tetraose into lacto-N-biose and lactose (12), or exoglycosidases with specificity for β(1-2), β(1-3), β(1-4), and/or β(1-6) glycosidic linkages (13–15). Unlike the case for Bifidobacterium species, data about the capacity of Lactobacillus species to metabolize human milk and mucosa-associated glycans are limited. The species Lactobacillus casei is commonly isolated from the feces of breast-fed infants (7, 8). In this work, we used L. casei strain BL23 as a laboratory model because it is easy to manipulate genetically. We have previously characterized three α-l-fucosidases from this strain (16) and demonstrated that in the species L. casei the utilization of fucosyl-α-1,3-N-acetylglucosamine, an abundant structural disaccharide present in human milk glycans, is dependent on the specific α-l-fucosidase AlfB (17). Recently, we have identified in L. casei BL23 the unique metabolic pathway for both lacto-N-biose and galacto-N-biose (Galβ1-3GalNAc). The latter is a core structure in mucin glycans. These disaccharides are transported and phosphorylated by the phosphoenolpyruvate:sugar phosphotransferase system (PTS), and then they are hydrolyzed into galactose-6-phosphate (galactose-6P) and the corresponding N-acetylhexosamine by the intracellular GH35 phospho-β-galactosidase GnbG (18). A gene encoding a GH20 β-N-acetylglucosaminidase from L. casei ATCC 27092 has also been cloned, and the purified enzyme has been biochemically characterized (19), but natural substrates were not tested and the physiological role of this enzyme was not determined. In this work, we demonstrated that L. casei BL23 is able to grow in the presence of lacto-N-triose. The chromosomal inactivation of the bnaG gene, encoding an extracellular β-N-acetylglucosaminidase, prevented growth on this carbohydrate, revealing the physiological role of a β-N-acetylglucosaminidase from Lactobacillus. Additionally, we showed that 3′-N-acetylglucosaminyl-mannose is also a fermentable carbon source for L. casei and that a mutant of manA, encoding a mannose-6P isomerase, is involved in its metabolism.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, culture conditions, and plasmids.

The strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. The Lactobacillus casei strains were routinely grown at 37°C under static conditions on MRS medium (Difco). Escherichia coli, which was used as the host in cloning experiments, was grown in Luria-Bertani medium at 37°C (Oxoid). The corresponding solid media were prepared by adding 1.8% agar. E. coli DH10B transformants were selected with ampicillin (100 μg/ml), and E. coli BE50 transformants were selected with ampicillin (100 μg/ml) and kanamycin (25 μg/ml). L. casei transformants were selected with erythromycin (5 μg/ml).

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this studya

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant genotype or description | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| Lactobacillus casei | ||

| BL23 | Wild type | CECT 5275 |

| BL126 | BL23 ptsI | 28 |

| BL380 | BL23 bnaG (frameshift at SphI site) | This work |

| BL381 | BL23 manA (frameshift at XagI site) | This work |

| Escherichia coli | ||

| DH10B | F− endA1 recA1 galE15 galK16 nupG rpsL ΔlacX74 ϕ80dlacZΔM15 araD139 Δ(ara leu)7697 mcrA Δ(mrr-hsdRMS-mcrBC) λ− | Invitrogen |

| BE50 | BL21(DE3) containing pREPGroES/GroEL | 34 |

| PE168 | BE50 containing pQEbnaG | This work |

| PE169 | BE50 containing pQEmanA | This work |

| Plasmids | ||

| pRV300 | Suicide vector carrying Ermr from pAMβ1 | 20 |

| pRVbnaG | pRV300 with a frameshift at SphI site in bnaG | This work |

| pRVmanA | pRV300 with a frameshift at XagI site in manA | This work |

| pQE80 | E. coli expression vector; Ampr | Qiagen |

| pQE bnaG | pQE80 containing bnaG coding region | This work |

| pQEmanA | pQE80 containing manA coding region | This work |

CECT, Colección Española de Cultivos Tipo; Ermr, erythromycin resistance; Ampr, ampicillin resistant.

Vector pRV300 (20) was used for cloning experiments with E. coli and for insertional inactivation of genes in L. casei. Vector pQE80 (Qiagen) was used for protein overproduction. E. coli and L. casei strains were transformed by electroporation with a Gene Pulser apparatus (Bio-Rad Laboratories) as recommended by the manufacturer (E. coli) or as described earlier (L. casei) (21).

Culture of L. casei strains with oligosaccharides.

The L. casei strains were grown overnight at 37°C under static conditions on sugar-free MRS fermentation medium (18). Overnight cultures were diluted to an optical density (OD) at 550 nm (OD550) of 0.05 in 100 μl of MRS medium containing 2 mM lacto-N-neotetraose, lacto-N-triose, 3′-N-acetylglucosaminyl-mannose, 3′-N-acetylgalactosaminyl-galactose, lactose, N-acetylglucosamine, or mannose. The first four oligosaccharides were obtained from Carbosynth (Compton, Berkshire, United Kingdom). Bacterial growth was monitored for 24 h by obtaining spectrophotometric measurements at 550 nm every 30 min in 96-well plates at 37°C without shaking in a POLARstar Omega microplate reader (BMG Labtech, Offenburg, Germany). At least three independent biological replicates for each growth curve were obtained. Results are expressed as means ± standard deviations. The growth rates (μ) were calculated by using the Gompertz model (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA).

DNA manipulation and sequencing.

Total DNA was isolated from L. casei BL23 as described before (21). Recombinant DNA techniques were performed by following standard procedures (22). All PCRs were performed with an Expand high-fidelity PCR system (Roche). DNA sequencing was carried out by the Central Service of Research Support of the University of Valencia (Valencia, Spain). M13 universal and reverse primers or custom primers hybridizing within the appropriate DNA fragments were used for sequencing. Sequence analyses were carried out with dnaman (version 4.03) for Windows (Lynnon Biosoft), and sequence similarities were analyzed with the BLAST program (23).

Construction of recombinant strains.

DNA fragments containing part of bnaG and manA were obtained by PCR using L. casei BL23 chromosomal DNA and the following oligonucleotide pairs: BnaGFow (5′-AGCTGCTGCTGATAACACC)/BnaGRev (5′-TCGGCTGGGCGAACTAAG) and ManAFow (5′-TTCATAGTGTCACGCAAGG)/ManA Rev (5′-TGAACGTCATGGTGCCATC), respectively. The PCR products were cloned into pRV300 that had been digested with EcoRV. The resulting plasmids, pRVbnaG and pRVmanA, respectively, were cleaved at the unique SphI and XagI restriction sites present in the bnaG and manA coding regions, respectively. The two digested plasmids were then treated with the Klenow fragment of DNA polymerase I, ligated, and transformed. Different constructs in which a frameshift was introduced at the SphI and XagI sites in bnaG (pRVbnaG) and manA (pRVmanA), respectively, were selected. L. casei was transformed with each of these plasmids. A single-crossover integrant of each gene was selected based on its resistance to erythromycin. Subsequently, these integrants were grown in MRS medium without erythromycin for about 200 generations. Cells were plated on MRS medium and replica plated on MRS medium plus erythromycin. Antibiotic-sensitive clones were isolated, and among them, we selected one clone for each gene (strains BL380 and BL381) in which a second recombination event led to the excision of the plasmid, leaving a mutated bnaG copy and a mutated manA copy in strains BL380 and BL381, respectively, as was confirmed by sequence analysis of appropriate PCR products.

Oligosaccharide and monosaccharide analysis.

To determine the carbohydrates present in the supernatants from the L. casei cultures, the cells were removed by centrifugation and the cultures were analyzed by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) using a Jasco PU2080Plus system (for L. casei cultures on lacto-N-neotetraose, lacto-N-triose, 3′-N-acetylgalactosaminyl-galactose, or lactose) or an ICS3000 chromatographic system (Dionex) (for L. casei cultures on 3′-N-acetylglucosaminyl-mannose or mannose). The PU2080Plus system was coupled to a refractive index detector (Jasco RI-2031 Plus) using a Rezex RCM-monosaccharide column (Phenomenex). The column was kept at 80°C, and the samples were eluted in isocratic mode using water as the mobile phase at a flow rate of 0.6 ml/min. For the Dionex system, a CarboPac PA100 column with pulsed amperometric detection was used. A combined gradient of 100 to 300 mM NaOH and 0 to 300 mM acetic acid was used (100 mM NaOH for 2 min, 100 to 300 mM NaOH for 3 min, 300 mM NaOH and 0 to 300 mM acetic acid for 15 min) at a flow rate of 1 ml/min. Oligo- and monosaccharides were confirmed by comparison of their retention times with those of standards (glucose, galactose, GlcNAc, GalNAc, mannose, fructose, and the di-, tri-, and tetrasaccharides listed in Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Activity and characterization of enzyme BnaGc

Carbohydrates used as the substrates. NP, nitrophenyl; Glc, glucose; Gal, galactose; GlcNAc, N-acetylglucosamine; GalNAc, N-acetylgalactosamine; Man, mannose; Fru, fructose.

+, the substrate was totally hydrolyzed after a 16-h reaction under the conditions described in the Materials and Methods section; +/−, the substrate was partially hydrolyzed after a 16-h reaction under the conditions described in the Materials and Methods section; −, no activity was detected.

The enzyme activity was determined with 4-nitrophenyl-β-d-glucosaminide as the substrate. Vmax was 33.3 μmol/mg protein/min, Km was 2.3 mM, the optimal pH was 6.5, and the optimal temperature was 53°C.

BnaG enzyme activity in whole cells and supernatants of L. casei cultures.

The L. casei strains were grown overnight at 37°C under static conditions on 10 ml of MRS fermentation medium containing 0.5% glucose or 0.5% ribose. When the cultures reached an OD550 of 1.5 (glucose) or 1.2 (ribose), cells were collected by centrifugation at 8,000 × g for 10 min, and the supernatants were subjected to ultracentrifugation at 100,000 × g for 60 min to remove the cell debris. The cell pellets were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and resuspended in this buffer to an OD550 of 2. The BnaG enzyme activity was determined at 37°C with 2.5 mM 4-nitrophenyl (NP)-N-acetyl-β-d-glucosaminide (pNPGlcNAc) in 96-well plates. The 4-nitrophenol released was measured by continuously following the changes in the absorbance at 404 nm using a POLARstar Omega microplate reader (BMG Labtech, Offenburg, Germany). Reactions with reaction mixtures (100 μl) containing the substrate in 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 6.5, were initiated by adding 75 μl of cell suspension or culture supernatant.

Expression and purification of His-tagged BnaG and ManA.

The coding regions of bnaG and manA were amplified by PCR using chromosomal DNA from L. casei BL23 as the template and the primer pairs 2860BamHIFW (5′-TTTTGGATC CGCTGATAACACCTTGAAAAGCG)/2860HindIIIRV (5′-TTTTAAGCTTTTACCGGTCT GGATTCACAATGG) and 2870BamHIFW (5′-TTTTGGATCCTTGACAGAACCATTATT TTTAAAACC)/2870HindIIIRV (5′-TTTTAAGCTTTTATGCGTCTACCCCTGGAGTAG), respectively, to which restriction sites were added to the 5′ and 3′ ends (underlined). The PCR fragments were cleaved with the corresponding restriction enzymes and cloned into pQE80 digested with the same enzymes. The resulting plasmids, pQEbnaG and pQEmanA, respectively, were used to transform E. coli BE50, and the correct sequence of the inserts was confirmed by DNA sequencing. One clone of each, PE168 (pQEbnaG) and PE169 (pQEmanA), was grown in 0.5 liter Luria-Bertani medium with appropriate antibiotics at 20°C under agitation. When the cultures reach an OD550 of 1.0, IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside; 1 mM) was added and incubation was continued for 5 h. Cells were harvested by centrifugation and resuspended in lysis buffer (Tris-HCl, 50 mM, pH 7.5; NaCl, 100 mM; Na2SO4, 50 mM; dithiothreitol, 0.5 mM; phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 mM). The recombinant proteins were purified as described previously (18). Fractions containing the proteins of interest were analyzed by SDS-PAGE, pooled, dialyzed against Tris-HCl (100 mM, pH 7.5) containing 20% glycerol, and kept frozen at −80°C. Protein concentrations were determined from spectrophotometric measurements at 280 nm in a NanoDrop instrument (Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, DE, USA).

His-tagged BnaG enzyme activity.

The activity of the purified His-tagged BnaG enzyme was assayed at 37°C with different 2/4-NP-sugars (see Table 3) at 5 mM in 96-well plates. The 2/4-nitrophenol released was measured by continuously following the changes in the absorbance at 404 nm using a POLARstar Omega microplate reader (BMG Labtech, Offenburg, Germany). Reactions with reaction mixtures (100 μl) containing the substrate in 100 mM Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.0, were initiated by adding 1 μg of enzyme. The optimal pH was determined with 5 mM pNPGlcNAc using 100 mM phosphate-citrate buffer (pH 3.0 to 7.0) and 100 mM glycine-NaOH buffer (pH 7.5 to 9.5). The optimal temperature of the reaction was analyzed by performing the reaction at temperatures ranging from 20 to 60°C and at the optimal pH. Kinetic studies were performed in 100 mM Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.0, at 37°C with pNPGlcNAc at concentrations ranging from 0.5 to 7.5 mM.

In order to determine the ability of BnaG to hydrolyze natural oligosaccharides, several substrates were tested (see Table 3). The reactions were performed with 100 μl of the reaction mixture at 37°C for 16 h using 4 mM substrate in 100 mM Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.0. The reaction mixtures were analyzed by HPLC using the Jasco PU2080Plus system as described above.

His-tagged ManA enzyme activity.

The activity of the purified His-tagged ManA enzyme was assayed as previously described (24) with some modifications. A typical reaction mixture (100 μl) contained 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer, pH 8.0, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM NADP+, 0.5 U of phosphoglucose isomerase, 1.0 U of glucose-6P dehydrogenase, and 3 mM mannose-6P. The reactions were initiated by adding 2 μg of enzyme. The activity was assayed at 37°C in 96-well plates, and the NADPH formation was monitored by continuously following the changes in the absorbance at 340 nm using the POLARstar Omega microplate reader (BMG Labtech, Offenburg, Germany). Kinetic studies were performed with mannose-6P at concentrations ranging from 1.0 to 10 mM.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The sequences of the truncated genes were deposited in GenBank under accession numbers KT954009 and KT954010.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

L. casei β-N-acetylglucosaminidase BnaG is an extracellular wall-attached protein.

Analysis of the genome surroundings of the gnb operon, which is involved in the utilization of lacto-N-biose and galacto-N-biose in L. casei BL23 (18), revealed the presence of two genes, one named bnaG (LCABL_02860) and one named manA (LCABL_02870) here, that are annotated as a putative β-N-acetylglucosaminidase precursor and a putative mannose-6P isomerase, respectively (Fig. 1A). The deduced amino acid sequence of bnaG showed a conserved protein domain, GH20_DspB_LnbB-like (cd06564), from amino acids 38 to 377 (25). Sequence analysis using the SignalP (version 4.0) program (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk) additionally showed that BnaG displayed an N-terminal signal peptide for secretion (amino acids 1 to 32), and a predicted C-terminal sortase-dependent cell wall-anchoring domain (amino acids 533 to 569) was already described (26). In order to determine if the bnaG gene was responsible of the β-N-acetylglucosaminidase activity in whole cells of L. casei BL23 (26), a mutant with a mutation in bnaG was constructed (strain BL380). The results showed that in the wild type the activity was higher in cells grown in ribose than in cells grown in glucose (Table 2), confirming the findings of previous studies that showed that the β-N-acetylglucosaminidase activity in L. casei was subjected to catabolic repression by glucose (27). β-N-Acetylglucosaminidase activity was also found in the supernatants of strain BL23 (Table 2), suggesting that part of the enzyme is liberated into the culture medium as a free enzyme. Interestingly, whole cells and supernatants of the BL380 mutant were totally devoid of activity (Table 2), indicating that the bnaG gene is responsible for the β-N-acetylglucosaminidase activity present in L. casei.

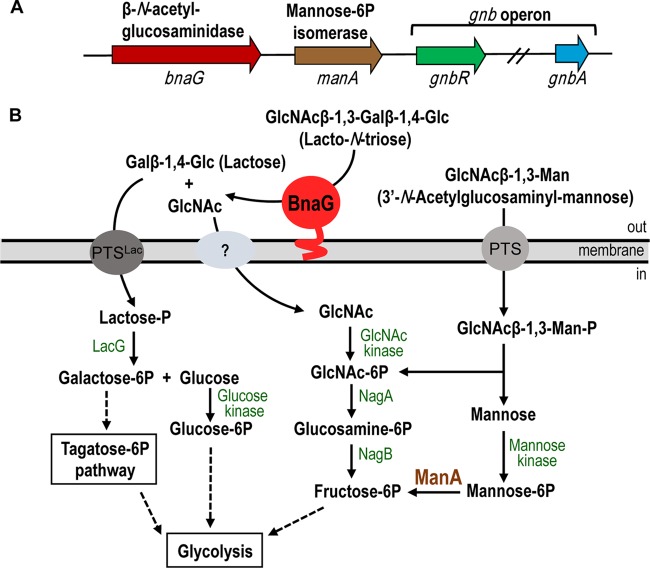

FIG 1.

(A) Schematic presentation of the 11.2-kbp Lactobacillus casei BL23 DNA fragment containing the β-N-acetylglucosaminidase precursor and a mannose-6P isomerase in the surroundings of the galacto-N-biose (gnb) operon (18). The first (gnbR) and last (gnbA) genes of this operon are represented. (B) Schematic presentation of proposed pathways for lacto-N-triose and 3′-N-acetylglucosaminyl-mannose metabolism in L. casei BL23. PTS, phosphoenolpyruvate:sugar phosphotransferase system; GlcNAc, N-acetylglucosamine; Gal, galactose; Man, mannose; LacG, phospho-β-galactosidase; NagA, N-acetylglucosamine-6P deacetylase; NagB, glucosamine-6P deaminase.

TABLE 2.

N-Acetylglucosaminidase activity in whole cells and supernatants of L. casei cultured in MRS fermentation medium with glucose or ribosea

| Strain |

N-Acetylglucosaminidase activityb (nmol/min/OD unit) in medium with: |

|

|---|---|---|

| Glucose | Ribose | |

| Whole cells | ||

| BL23 (wild type) | 0.223 ± 0.015 | 2.962 ± 0.011 |

| BL380 (bnaG) | 0.0 ± 0.013 | 0.0 ± 0.015 |

| Supernatants | ||

| BL23 (wild type) | 0.247 ± 0.003 | 0.934 ± 0.075 |

| BL380 (bnaG) | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 |

N-Acetylglucosaminidase activity was determined with 4-nitrophenyl-β-d-glucosaminide as the substrate.

Each value represents the mean of four different measurements ± standard deviation.

Substrate specificity and enzymatic characteristics of L. casei β-N-acetylglucosaminidase BnaG.

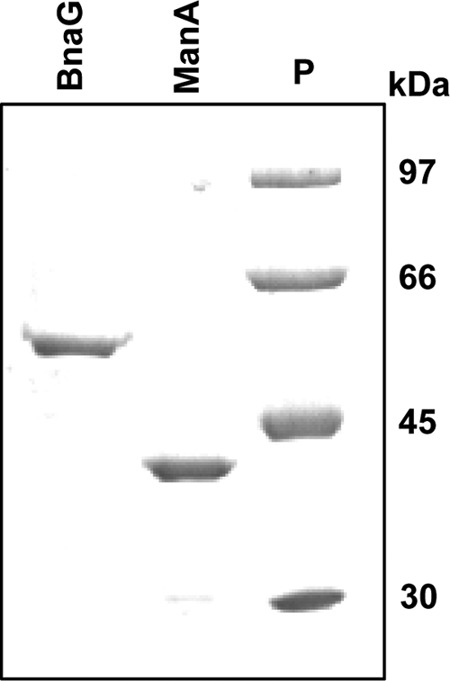

The His-tagged β-N-acetylglucosaminidase BnaG from L. casei without the N-terminal signal peptide and the C-terminal cell wall-anchoring domain was expressed in E. coli. The purified protein showed a molecular mass of 55 kDa, in agreement with the calculated mass of the 6×His-tagged protein (55,250 Da; Fig. 2). The recombinant BnaG hydrolyzed pNPGlcNAc and 2-NP-β-d-galactopyranoside; however, the latter was poorly hydrolyzed (Table 3). The catalytic properties of BnaG using pNPGlcNAc as the substrate were determined (Table 3). Although the deduced amino acid sequences of BnaG and the N-acetylglucosaminidase from L. casei ATCC 27092 (19) showed a high degree of homology (91.7% identity), the Km, optimum pH, and optimum temperature were different. The Km (6.4 μM) of the enzyme from the ATCC 27092 strain showed that the affinity for the substrate pNPGlcNAc was about 350-fold higher than that of BnaG. The modifications of the sequence described above for the purified BnaG could account for those differences between the two β-N-acetylglucosaminidases. Indeed, the enzyme from the ATCC 27092 strain showed a molecular mass (39 kDa) (19) lower than that determined for BnaG. Regarding natural oligosaccharides, BnaG is able to degrade lacto-N-triose into GlcNAc and lactose. However, it does not hydrolyze lacto-N-tetraose or lacto-N-neotetraose, which contain the same GlcNAcβ1,3-glycosidic linkage, indicating that BnaG showed exoglycosidase activity but not endoglycosidase activity. BnaG also degrades the disaccharides 3′-N-acetylglucosaminyl-mannose, 3′-N-acetylgalactosaminyl-galactose, galacto-N-biose, and lacto-N-biose, although the last two were cleaved very inefficiently (Table 3). These results indicate that the β-N-acetylglucosaminidase BnaG from L. casei showed specificity for β1,3-glycosidic linkages, and within these, N-acetylhexosaminyl-β1,3-linked sugars are better substrates than their corresponding hexoses.

FIG 2.

Coomassie brilliant blue-stained 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel showing the His-tagged proteins β-N-acetylglucosaminidase BnaG and mannose-6P isomerase ManA. Lane P, protein standards. The numbers on the right are molecular masses.

L. casei ferments lacto-N-triose and hydrolyzes it by using the β-N-acetylglucosaminidase BnaG.

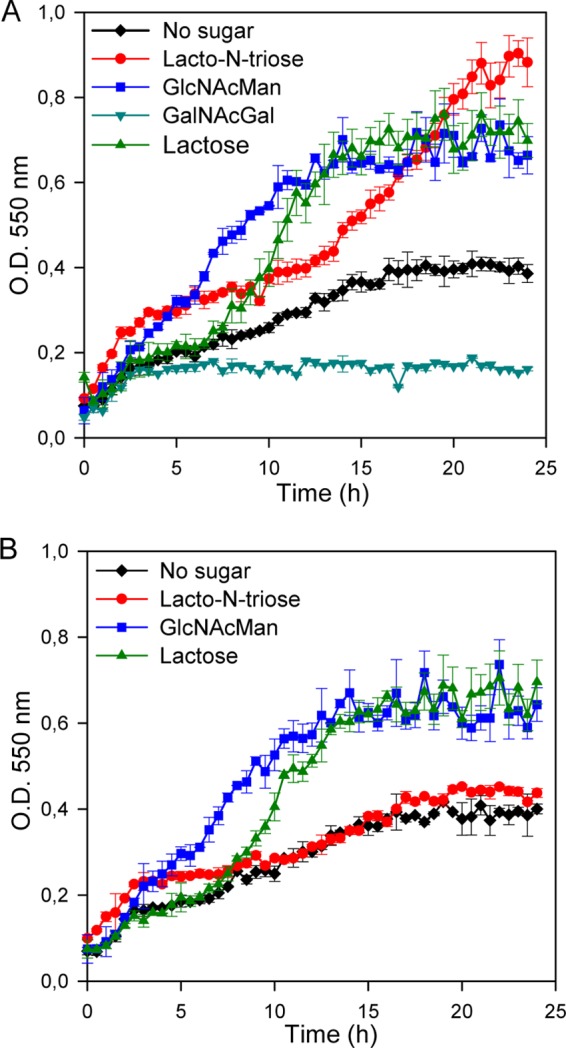

In order to determine the capacity of L. casei BL23 to metabolize lacto-N-triose, 3′-N-acetylglucosaminyl-mannose, and 3′-N-acetylgalactosaminyl-galactose, which were substrates in vitro for the β-N-acetylglucosaminidase BnaG, the growth profile in MRS basal medium supplemented with 2 mM those oligosaccharides was determined independently. L. casei BL23 was able to grow in the presence of lacto-N-triose and 3′-N-acetylglucosaminyl-mannose as fermentable carbon sources (Fig. 3A). However, the presence of 3′-N-acetylgalactosaminyl-galactose resulted in diminished growth compared with the residual growth of L. casei in nonsupplemented MRS basal medium (Fig. 3A). The growth pattern of L. casei in the presence of lactose as a positive control is also shown (Fig. 3A). To determine if the β-N-acetylglucosaminidase BnaG was involved in the utilization of lacto-N-triose and 3′-N-acetylglucosaminyl-mannose in L. casei BL23, the mutant strain BL380 (bnaG) was cultured in the presence of those oligosaccharides as carbon sources. Interestingly, this mutant exhibited diminished growth with lacto-N-triose which was comparable to that of the negative control (with nonsupplemented MRS basal medium), indicating that BnaG is necessary for the utilization of this oligosaccharide (Fig. 3B). Sugar content analysis of the culture supernatants detected lacto-N-triose in the supernatants from BL380 (bnaG), while it was completely consumed by the wild-type BL23 strain. In the wild-type strain, the resulting products (GlcNAc and lactose) from the lacto-N-triose hydrolysis by BnaG were also exhausted. The results presented above suggest that BnaG is an extracellular enzyme and that it would then hydrolyze lacto-N-triose from outside the cells into GlcNAc and lactose. GlcNAc would then be transported inside the cells by a yet unknown PTS and/or a PTS-independent permease (28). The lactose moiety would be internalized by the already characterized PTSLac into the cells as lactose-6P, and this phosphorylated sugar would be degraded by the phospho-β-galactosidase LacG into galactose-6P and glucose (29) (Fig. 1B). Although 3′-N-acetylglucosaminyl-mannose is an in vitro substrate for BnaG, the results showed that the growth rate (0.120 h−1) of BL380 (bnaG) is similar to the rate of the wild type (0.113 h−1) (Fig. 3B), suggesting that its metabolism is independent of that of glycosidase. Sugar content analysis of the culture supernatants did not detect 3′-N-acetylglucosaminyl-mannose in either BL23 or BL380 culture supernatants.

FIG 3.

(A) Growth curves of Lactobacillus casei wild-type strain BL23 on MRS basal medium without a carbon source (black) or with lacto-N-triose (red), 3′-N-acetylglucosaminyl-mannose (blue), 3′-N-acetylgalactosaminyl-galactose (dark cyan), or lactose (green). (B) Growth curves of L. casei mutant strain BL380 (bnaG) on MRS basal medium without a carbon source (black) or with lacto-N-triose (red), 3′-N-acetylglucosaminyl-mannose (blue), or lactose (green). The data presented are mean values based on at least three replicates. Error bars indicate standard deviations.

The metabolism of lacto-N-triose resulting from the catabolism of lacto-N-neotetraose has been previously reported in B. bifidum (13). This tetrasaccharide was sequentially hydrolyzed from its nonreducing terminus by two extracellular exoenzymes with β-galactosidase and β-N-acetylglucosaminidase activity, respectively (13). L. casei was able to grow in the presence of lacto-N-triose, whereas it was not able to ferment lacto-N-neotetraose (data not shown), suggesting that this strain lacks a β-galactosidase activity able to convert the tetrasaccharide into galactose and lacto-N-triose, at least under our experimental conditions. Analysis of the available genome sequences of lactobacilli (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genomes) showed that the bnaG gene was present only in the species L. casei and Lactobacillus paracasei. Notably, it was not conserved in the phylogenetically related species Lactobacillus rhamnosus. The lack of a bnaG gene in the latter species correlated with the inability of two strains of L. rhamnosus (strains ATCC 9595 and ATCC 53103 [L. rhamnosus GG]) to metabolize lacto-N-triose. However, L. rhamnosus strain HN001 was able to grow using lacto-N-triose as a carbon source (G. N. Bidart, J. Rodríguez-Díaz and M. J. Yebra, unpublished results), suggesting that, in addition to BnaG, lactobacilli have other enzymes involved in the catabolism of this trisaccharide.

ManA is required for mannose and 3′-N-acetylglucosaminyl-mannose metabolism in L. casei.

As shown above, 3′-N-acetylglucosaminyl-mannose was a carbon source for L. casei BL23, and a mutant deficient in the general component enzyme I of the PTS (28) was unable to ferment that disaccharide, which remained nonhydrolyzed in the culture supernatant (data not shown). These results suggest that 3′-N-acetylglucosaminyl-mannose is transported and phosphorylated by the PTS and it might be hydrolyzed inside the cells by a yet unknown phospho-β-glycosidase (Fig. 1B). The PTS phosphorylates the incoming disaccharides at the nonreducing end (18, 29); therefore, the intracellular products generated from 3′-N-acetylglucosaminyl-mannose would probably be GlcNAc-P and mannose. We analyzed if the manA gene was involved in the metabolism of that disaccharide. The deduced amino acid sequence of manA showed 53% and 48% identity with the sequences of the characterized type I mannose-6P isomerases (EC.5.3.1.8) from Streptococcus mutans (30) and Bacillus subtilis (31), respectively. The manA gene from L. casei BL23 codes for a 323-amino-acid protein without a signal peptide or a cell wall-anchoring motif, and it was expressed in E. coli. The purified His-tagged protein showed a molecular mass of 37 kDa, in agreement with the calculated mass of the 6×His-tagged protein (36,815 Da; Fig. 2). ManA activity was analyzed by following the conversion of mannose-6P into fructose-6P, and it exhibited a Vmax of 1.11 μmol/mg protein/min and a Km of 2.78 mM. This and the results presented below also suggest that the mannose resulting from the hydrolysis of 3′-N-acetylglucosaminyl-mannose would be phosphorylated by a mannose kinase at the C-6 position. Mannose-6P would be converted into the glycolytic intermediate fructose-6P by ManA (Fig. 1B).

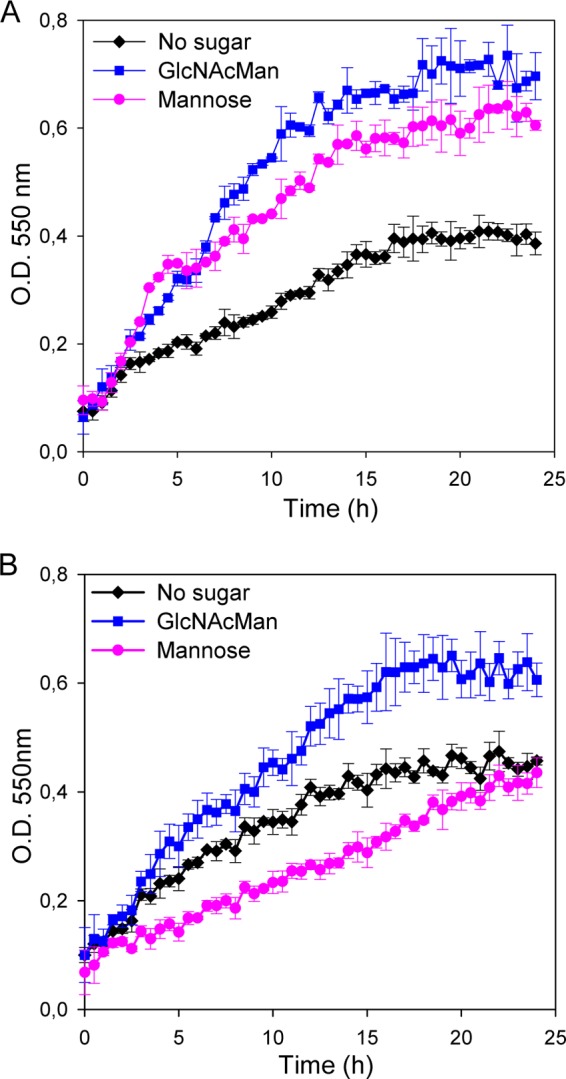

To determine if the mannose-6P isomerase ManA was involved in the utilization of 3′-N-acetylglucosaminyl-mannose in L. casei BL23, a mutant with a mutation in manA was constructed (strain BL381). Interestingly, this mutant showed a growth rate (0.064 h−1) lower than that of the wild-type strain BL23 (0.113 h−1) with that disaccharide as the carbon source in the culture medium (Fig. 4), indicating that manA is involved in the utilization of 3′-N-acetylglucosaminyl-mannose. However, mannose was not detected in the culture supernatants from BL381, which is in agreement with the fact that the maximum cell density reached by this strain was similar to that of the wild-type strain BL23. The rate of growth of strain BL381 (manA) with mannose as the carbon source was lower (0.026 h−1) than that of the negative control grown on nonsupplemented MRS basal medium (0.038 h−1) (Fig. 4B), indicating that ManA is necessary for the utilization of mannose in L. casei. Curiously, after 24 h the culture reached an OD similar to that of the control, which indicates that the growth of strain BL381 was recovering. These results and the growth profile of strain BL381 in the presence of 3′-N-acetylglucosaminyl-mannose suggested that additional genes involved in the metabolism of the mannose might be expressed. Using the deduced amino acid sequence of ManA in BLAST searches against the L. casei BL23 genome (32), another mannose-6P isomerase (LCABL_06290) was found. It showed 47% homology (30% identity) with the ManA characterized here. Hence, the catabolism of 3′-N-acetylglucosaminyl-mannose in the manA mutant might depend on this additional mannose-6P isomerase being able to utilize the mannose-6P generated.

FIG 4.

Growth curves of Lactobacillus casei wild-type strain BL23 (A) and L. casei mutant strain BL381 (manA) (B) on MRS basal medium without a carbon source (black) or with 3′-N-acetylglucosaminyl-mannose (blue) or mannose (pink). Data are presented as mean values based on at least three replicates. Error bars indicate standard deviations.

The species Lactobacillus casei is associated with the infant and adult human gastrointestinal tract, and some strains are considered beneficial for the host (7, 8, 33). The establishment of this species in the gut and its interaction with the host rely on its nutritional capacities. The extracellular localization of the β-N-acetylglucosaminidase studied here and its activity on human milk and mucosa-linked glycans probably constitute a molecular strategy that these bacteria use to survive in the gut.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was financed by funds of the Spanish Ministry for Economy and Competitiveness (MINECO)/FEDER through projects AGL2014-52996-C2 (1-R and 2-R) and of the Valencian government through project ACOMP/2012/030. G.N.B. was supported by a predoctoral fellowship from the Carolina Foundation and Argentinian Ministry of Education.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bode L. 2012. Human milk oligosaccharides: every baby needs a sugar mama. Glycobiology 22:1147–1162. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cws074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garrido D, Dallas DC, Mills DA. 2013. Consumption of human milk glycoconjugates by infant-associated bifidobacteria: mechanisms and implications. Microbiology 159:649–664. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.064113-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang M, Li M, Wu S, Lebrilla CB, Chapkin RS, Ivanov I, Donovan SM. 2015. Fecal microbiota composition of breast-fed infants is correlated with human milk oligosaccharides consumed. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 60:825–833. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000000752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Leoz ML, Kalanetra KM, Bokulich NA, Strum JS, Underwood MA, German JB, Mills DA, Lebrilla CB. 2015. Human milk glycomics and gut microbial genomics in infant feces show a correlation between human milk oligosaccharides and gut microbiota: a proof-of-concept study. J Proteome Res 14:491–502. doi: 10.1021/pr500759e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yu ZT, Chen C, Kling DE, Liu B, McCoy JM, Merighi M, Heidtman M, Newburg DS. 2013. The principal fucosylated oligosaccharides of human milk exhibit prebiotic properties on cultured infant microbiota. Glycobiology 23:169–177. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cws138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li M, Monaco MH, Wang M, Comstock SS, Kuhlenschmidt TB, Fahey GC Jr, Miller MJ, Kuhlenschmidt MS, Donovan SM. 2014. Human milk oligosaccharides shorten rotavirus-induced diarrhea and modulate piglet mucosal immunity and colonic microbiota. ISME J 8:1609–1620. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2014.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martin R, Heilig GH, Zoetendal EG, Smidt H, Rodriguez JM. 2007. Diversity of the Lactobacillus group in breast milk and vagina of healthy women and potential role in the colonization of the infant gut. J Appl Microbiol 103:2638–2644. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2007.03497.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Albesharat R, Ehrmann MA, Korakli M, Yazaji S, Vogel RF. 2011. Phenotypic and genotypic analyses of lactic acid bacteria in local fermented food, breast milk and faeces of mothers and their babies. Syst Appl Microbiol 34:148–155. doi: 10.1016/j.syapm.2010.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Turroni F, Peano C, Pass DA, Foroni E, Severgnini M, Claesson MJ, Kerr C, Hourihane J, Murray D, Fuligni F, Gueimonde M, Margolles A, De Bellis G, O'Toole PW, van Sinderen D, Marchesi JR, Ventura M. 2012. Diversity of bifidobacteria within the infant gut microbiota. PLoS One 7:e36957. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Locascio RG, Ninonuevo MR, Kronewitter SR, Freeman SL, German JB, Lebrilla CB, Mills DA. 2009. A versatile and scalable strategy for glycoprofiling bifidobacterial consumption of human milk oligosaccharides. Microb Biotechnol 2:333–342. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7915.2008.00072.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.LoCascio RG, Desai P, Sela DA, Weimer B, Mills DA. 2010. Broad conservation of milk utilization genes in Bifidobacterium longum subsp. infantis as revealed by comparative genomic hybridization. Appl Environ Microbiol 76:7373–7381. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00675-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wada J, Ando T, Kiyohara M, Ashida H, Kitaoka M, Yamaguchi M, Kumagai H, Katayama T, Yamamoto K. 2008. Bifidobacterium bifidum lacto-N-biosidase, a critical enzyme for the degradation of human milk oligosaccharides with a type 1 structure. Appl Environ Microbiol 74:3996–4004. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00149-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miwa M, Horimoto T, Kiyohara M, Katayama T, Kitaoka M, Ashida H, Yamamoto K. 2010. Cooperation of beta-galactosidase and beta-N-acetylhexosaminidase from bifidobacteria in assimilation of human milk oligosaccharides with type 2 structure. Glycobiology 20:1402–1409. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwq101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jiang YL, Yu WL, Zhang JW, Frolet C, Di Guilmi AM, Zhou CZ, Vernet T, Chen Y. 2011. Structural basis for the substrate specificity of a novel beta-N-acetylhexosaminidase StrH protein from Streptococcus pneumoniae R6. J Biol Chem 286:43004–43012. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.256578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thi NN, Offen WA, Shareck F, Davies GJ, Doucet N. 2014. Structure and activity of the Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) beta-N-acetylhexosaminidase provides further insight into GH20 family catalysis and inhibition. Biochemistry 53:1789–1800. doi: 10.1021/bi401697j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rodriguez-Diaz J, Monedero V, Yebra MJ. 2011. Utilization of natural fucosylated oligosaccharides by three novel alpha-l-fucosidases from a probiotic Lactobacillus casei strain. Appl Environ Microbiol 77:703–705. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01906-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rodriguez-Diaz J, Rubio-del-Campo A, Yebra MJ. 2012. Lactobacillus casei ferments the N-acetylglucosamine moiety of fucosyl-alpha-1,3-N-acetylglucosamine and excretes l-fucose. Appl Environ Microbiol 78:4613–4619. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00474-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bidart GN, Rodriguez-Diaz J, Monedero V, Yebra MJ. 2014. A unique gene cluster for the utilization of the mucosal and human milk-associated glycans galacto-N-biose and lacto-N-biose in Lactobacillus casei. Mol Microbiol 93:521–538. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Senba M, Kashige N, Nakashima Y, Miake F, Watanabe K. 2000. Cloning of the gene of beta-N-acetylglucosaminidase from Lactobacillus casei ATCC 27092 and characterization of the enzyme expressed in Escherichia coli. Biol Pharm Bull 23:527–531. doi: 10.1248/bpb.23.527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leloup L, Ehrlich SD, Zagorec M, Morel-Deville F. 1997. Single-crossover integration in the Lactobacillus sake chromosome and insertional inactivation of the ptsI and lacL genes. Appl Environ Microbiol 63:2117–2123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Posno M, Leer RJ, van Luijk N, van Giezen MJ, Heuvelmans PT, Lokman BC, Pouwels PH. 1991. Incompatibility of Lactobacillus vectors with replicons derived from small cryptic Lactobacillus plasmids and segregational instability of the introduced vectors. Appl Environ Microbiol 57:1822–1828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol 215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gill JF, Deretic V, Chakrabarty AM. 1986. Overproduction and assay of Pseudomonas aeruginosa phosphomannose isomerase. J Bacteriol 167:611–615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marchler-Bauer A, Derbyshire MK, Gonzales NR, Lu S, Chitsaz F, Geer LY, Geer RC, He J, Gwadz M, Hurwitz DI, Lanczycki CJ, Lu F, Marchler GH, Song JS, Thanki N, Wang Z, Yamashita RA, Zhang D, Zheng C, Bryant SH. 2015. CDD: NCBI's Conserved Domain Database. Nucleic Acids Res 43:D222–D226. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Munoz-Provencio D, Rodriguez-Diaz J, Collado MC, Langella P, Bermudez-Humaran LG, Monedero V. 2012. Functional analysis of the Lactobacillus casei BL23 sortases. Appl Environ Microbiol 78:8684–8693. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02287-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Monedero V, Gosalbes MJ, Perez-Martinez G. 1997. Catabolite repression in Lactobacillus casei ATCC 393 is mediated by CcpA. J Bacteriol 179:6657–6664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Viana R, Monedero V, Dossonnet V, Vadeboncoeur C, Perez-Martinez G, Deutscher J. 2000. Enzyme I and HPr from Lactobacillus casei: their role in sugar transport, carbon catabolite repression and inducer exclusion. Mol Microbiol 36:570–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gosalbes MJ, Monedero V, Alpert CA, Perez-Martinez G. 1997. Establishing a model to study the regulation of the lactose operon in Lactobacillus casei. FEMS Microbiol Lett 148:83–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb10271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sato Y, Yamamoto Y, Kizaki H, Kuramitsu HK. 1993. Isolation and sequence analysis of the pmi gene encoding phosphomannose isomerase of Streptococcus mutans. FEMS Microbiol Lett 114:61–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1993.tb06551.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yeom SJ, Ji JH, Kim NH, Park CS, Oh DK. 2009. Substrate specificity of a mannose-6-phosphate isomerase from Bacillus subtilis and its application in the production of l-ribose. Appl Environ Microbiol 75:4705–4710. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00310-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maze A, Boel G, Zuniga M, Bourand A, Loux V, Yebra MJ, Monedero V, Correia K, Jacques N, Beaufils S, Poncet S, Joyet P, Milohanic E, Casaregola S, Auffray Y, Perez-Martinez G, Gibrat JF, Zagorec M, Francke C, Hartke A, Deutscher J. 2010. Complete genome sequence of the probiotic Lactobacillus casei strain BL23. J Bacteriol 192:2647–2648. doi: 10.1128/JB.00076-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Turroni F, Ventura M, Butto LF, Duranti S, O'Toole PW, Motherway MO, van Sinderen D. 2014. Molecular dialogue between the human gut microbiota and the host: a Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium perspective. Cell Mol Life Sci 71:183–203. doi: 10.1007/s00018-013-1318-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dale GE, Schonfeld HJ, Langen H, Stieger M. 1994. Increased solubility of trimethoprim-resistant type S1 DHFR from Staphylococcus aureus in Escherichia coli cells overproducing the chaperonins GroEL and GroES. Protein Eng 7:925–931. doi: 10.1093/protein/7.7.925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]