Abstract

Bacterial biological control agents (BCAs) are largely used as live products to control plant pathogens. However, due to variable environmental and ecological factors, live BCAs usually fail to produce desirable results against foliar pathogens. In this study, we investigated the potential of cell-free culture filtrates of 12 different bacterial BCAs isolated from flower beds for controlling foliar diseases caused by Alternaria spp. In vitro studies showed that culture filtrates from two isolates belonging to Bacillus subtilis and Bacillus amyloliquefaciens displayed strong efficacy and potencies against Alternaria spp. The antimicrobial activity of the culture filtrate of these two biological control agents was effective over a wider range of pH (3.0 to 9.0) and was not affected by autoclaving or proteolysis. Comparative liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) analyses showed that a complex mixture of cyclic lipopeptides, primarily of the fengycin A and fengycin B families, was significantly higher in these two BCAs than inactive Bacillus spp. Interaction studies with mixtures of culture filtrates of these two species revealed additive activity, suggesting that they produce similar products, which was confirmed by LC-tandem MS analyses. In in planta pre- and postinoculation trials, foliar application of culture filtrates of B. subtilis reduced lesion sizes and lesion frequencies caused by Alternaria alternata by 68 to 81%. Taken together, our studies suggest that instead of live bacteria, culture filtrates of B. subtilis and B. amyloliquefaciens can be applied either individually or in combination for controlling foliar diseases caused by Alternaria species.

INTRODUCTION

Many species in the genus Alternaria cause significant yield and quality losses in food and ornamental crops (1). These species primarily attack aerial plant parts, including foliage, fruits, and stems, and cause a variety of symptoms ranging from necrotic leaf spots to enlarged blighted shoots, eventually resulting in defoliation and loss in yield and quality. Alternaria diseases could be managed with a combination of cultural practices, fungicides, and, if available, genetic resistance. Since many crop cultivars lack sufficient resistance to Alternaria spp., fungicide sprays are the primary means of controlling Alternaria diseases (1). However, loss in the efficacy of several commonly used fungicides for controlling Alternaria spp. has been reported (2–6). Loss of effective fungicides requires discovery and development of new and safe alternative chemicals. Although fungicides with newer chemistry are promising, their introduction into crop production systems is slow, and resistant field isolates of the pathogen usually appear very quickly, within a few seasons of the introduction of a new fungicide (5, 7, 8). As with many other plant pathogens, in most cases fungicide resistance in Alternaria spp. has been attributed to single-site mutations in the target genes (see, e.g., references 9, 10, and 11). Therefore, finding multisite-acting fungicides that are difficult to break down and are relatively stable might provide a sustainable means of control. Biological control agents (BCAs) or the products derived thereof could be used as a sustainable alternative or as a complement to fungicides in integrated pest management programs.

Many bacterial BCAs are currently being used for controlling plant pests and diseases (reviewed in references 12 and 13). Several Bacillus species have been developed into commercial products for controlling a wide range of diseases caused by fungi and oomycetes (13–16). Biological control activities of most bacterial BCAs have been attributed to cell wall-degrading enzymes, antimicrobial peptides, cyclic lipopeptides (CLPs) such as iturins, fengycins, and surfactins, low-molecular-weight metabolites, volatile organic compounds, and induction of systemic resistance in host plants (13, 17–25). Iturins, surfactin, and fengycins are extensively studied and, using knockout mutants and purified extracts, have been associated with antimicrobial activities. These peptides are distinguished from each other by the types and number of amino acids and the length of fatty acid side chains. A combination of ring amino acids and fatty acid side chains provides tremendous structural diversity, which likely accounts for the broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity of culture filtrates (CFs) of Bacillus spp. Mass spectrometry of iturins and surfactins displays masses in the m/z range of 1000 to 1200, whereas fengycins are in the m/z range of 1400 to 1600 (18, 24, 26–28). Fengycins, surfactins, and iturins also display differential activity against different plant fungal pathogens, most likely due to differences in lipid composition of the target fungi (29). Different Bacillus spp. produce complex mixtures of these peptides, and depending on the target fungal pathogen, it is suggested that these peptides act together in compromising membrane permeability (30).

Bacterial BCAs differ in their genetic makeup and ecological and adaptation characteristics, which define their biological potential and antimicrobial activities. Previously we have isolated and characterized 129 different isolates of soil-inhabiting bacteria from diverse bedding plants (31). Based on fatty acid analyses, these isolates were classified into 14 different species in six different genera. Since they were isolated from diverse host plants, it is possible that they might display antimicrobial activity against different plant pathogens.

Most research on biological control agents has focused on using live bacteria. However, the success and survival of BCAs depends on establishment, proliferation and colonization, and persistence in the plant and soil environment (32). These survival factors are in turn dependent on temperature, humidity, physical characteristics of soil such as pH, soil porosity, and composition, and light quality and intensity (33, 34). Dependence on these environmental factors is often cited as one of the major reasons for inconsistency in the performance of BCAs (35). To circumvent these issues, it would be highly useful if the bioactive compound(s) was extracted, characterized, and used directly as soil drenches or sprays instead of live bacteria. In this study, we showed that the extracellular culture filtrate of some of these bacteria contain substantial quantities of the bioactive ingredient(s). We found that the active ingredient(s) maintains fungicidal activity after exposure to high temperature and proteolysis, indicating that after production they could be easily stored, transported, and marketed with less concerns about their shelf life. Mixtures of fungicides have several advantages, including an extended control spectrum, reduced fungicide resistance, and potential synergism. Antimicrobial compounds when mixed may display synergistic (greater than expected), additive (one compound could be replaced by another with similar effects), or antagonistic (less than expected) activities (36, 37). The effect of interaction of cell-free culture filtrates of BCAs has not been studied extensively. These studies are important for extending the biological control spectrum of rhizosphere BCAs to above-ground plant parts. In addition, such investigations are also essential for discovering new antimicrobials with higher potencies and efficacies. In this study, we tested the hypothesis that the culture filtrates of soil-inhabiting BCAs can be used for controlling foliar diseases. The objectives of this research were (i) to screen culture filtrates of different bacterial species for antimicrobial activity against Alternaria spp. in vitro and in planta, (ii) to determine the stability of culture filtrates to heat, proteolysis, and pH, (iii) to determine the level of synergism in the culture filtrates of different BCAs, and (iv) to identify bioactive lipopeptides in the culture filtrates of BCAs using liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) and LC-tandem MS (LC-MS/MS) analyses.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Biological control agents and preparation of cell-free culture extract.

Information about the biological control agents used in this study is summarized in Table 1. All bacterial strains were initially revived from glycerol stocks maintained at −80°C on NYG agar (0.5% tryptone peptone, 0.3% yeast extract, 2% glycerol, 1.5% Bacto agar) at 28°C. Single colonies from each BCA strain were first grown in 5 ml LB medium in test tubes at 28°C in a shaker incubator until the optical density at 600 nm (OD600) reached approximately 0.6 to 0.8. One milliliter of this culture was added to 50 ml LB medium contained in a 250-ml flask and incubated at 28°C in a shaker incubator (220 rpm) for 24 h. At this point, all cultures grew to early stationary phase (OD600 = ∼3.0). Cells were pelleted by centrifugation at 5,000 × g for 10 min at room temperature. Supernatant was filtered through a 0.20-μm filter and stored at 4°C until further use.

TABLE 1.

Antimicrobial activity of isolates used in this study

| BCAa | Isolate | Host plant | Mean IC50 (95% CI)b | Mean MIC (95% CI)c |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacillus megaterium | B11-13 | Begonia sp. | >10 | |

| Bacillus thuringiensis | B11-48 | Fern | >10 | |

| Bacillus subtilis | B11-128 | Impatiens sp. | 0.21 (0.15–0.29) | 2.14 (1.16–3.95) |

| Bacillus amyloliquefaciens | B11-144 | Lantana sp. | 0.33 (0.21–0.51) | 1.40 (0.63–3.21) |

| Bacillus mycoides | B156 | Salvia sp. | 9.12 | |

| Bacillus pumilus | B182 | Coleus | 8.87 | |

| Bacillus circulans | B9 | Impatiens sp. | >10 | |

| Lysinibacillus sphaericus | B65 | Impatiens sp. | 9.34 | |

| Bacillus freudenreichii | B68 | Lantana sp. | >10 | |

| Bacillus cereus | B147 | Marigold | >10 | |

| Brevibacillus laterosporus | B173 | Salvia sp. | >10 | |

| Bacillus brevis | B194 | Pentas sp. | >10 | |

| Azoxystrobin (Heritage)d | 0.023 (0.017–0.032) | 0.09 (0.053–0.21) |

The identification of biological control agent (BCA) strains has been reported before (31).

Fifty percent inhibitory concentration (IC50) values, expressed as percent (vol/vol) amount of bacterial culture filtrate in the assay solution, were predicted from logistic curves fitted to the dose-response data for B11-128 and B11-144 culture filtrates tested against A. alternata in vitro; IC50 values for the remaining isolates were estimated from the data of Fig. 1. 95% CI, 95% confidence intervals.

MICs were considered minimum concentrations that completely inhibited growth. These values roughly corresponded to IC90 values, which were predicted from the logistic curves.

Heritage, a broad-spectrum fungicide consisting of 50% azoxystrobin as the active ingredient, was used as a positive control.

Target fungi and their culture.

Three major Alternaria spp., A. alternata, A. solani, and A. brassicicola, which infect and cause significant yield loss in many crops were used as target fungi. Isolates of A. alternata, A. solani, and A. brassicicola were recovered from infected impatiens, potato, and Arabidopsis plants, respectively. All isolates were cultured on potato dextrose agar (PDA) under continuous light at 25°C for 4 days. Spores were resuspended in potato dextrose broth (PDB) (Difco) to a final concentration of 3 × 104 spores ml−1.

Antifungal assays.

In vitro fungal growth inhibition assays were performed in 96-well microtiter plates as described previously (38). Briefly, culture filtrates of BCAs were diluted appropriately (10% to 0.01%) in LB according to the goals of the experiment and added to the wells of a 96-well flat-bottom microtiter plate (100 μl/well). One hundred microliters of the conidial suspension (3 ×104 spores ml−1 in PDB) was added to each well. Each treatment was replicated four times, and each experiment was repeated at least two times. Plates were wrapped with Parafilm and incubated at 25°C under continuous light. The absorbance (OD600) of each plate was read with the Synergy H1 hybrid multimode plate reader (BioTek) at the beginning (0 h) of an experiment and 24 h after incubation. All plates were routinely checked at the beginning and end of experiments for any bacterial contamination or turbidity with the naked eye and under an inverted microscope. Net mycelial growth was calculated by subtracting absorbance at 0 h from absorbance at the 24-h interval. Normalized net growth (percentage of the value for the untreated control) was determined by dividing net growth in each treatment by net growth in the untreated control.

Dose-response curve fitting and statistical analyses.

Dose-response analyses were conducted using 11 twofold serial dilutions (10 to 0.01%) in a microtiter plate using OD600 as described above. Dose-response data were fitted with the following 4-parameter logistic (4PL) curves using the Prism 6.0 software (GraphPad Software, Inc.): Y = [basal + (maximal − basal)]/[1 + 10(log IC50 − X) × Hill slope]. In the equation, Y is normalized net growth, basal and maximal are the basal and maximal growths expressed in units of Y, respectively, and X is the log culture filtrate (CF) dilutions. Statistical analyses of goodness of fit of curves and comparison of curves in response to different treatments were performed using Prism 6.0. Fifty percent inhibitory concentrations (IC50s), defined as the CF dilution required for 50% growth inhibition, were calculated from the fitted 4PL curves.

Interaction of culture filtrates of Bacillus subtilis (B11-128) and Bacillus amyloliquefaciens (B11-144).

To determine if B11-128 and B11-144 interact with each other additively, synergistically, or antagonistically in inhibiting A. alternata, CFs of these two isolates were tested alone and in 1:1 (vol/vol) mixtures at seven different concentrations. Concentrations for B11-128 and B11-144 alone were 2, 1, 0.3, 0.2, 0.14, 0.1, and 0.02%. A corresponding 1:1 mixture series consisted of B11-128 plus B11-144 at 1% plus 1%, 0.5% plus 0.5%, 0.15% plus 0.15%, 0.1% plus 0.1%, 0.07% plus 0.07%, 0.05% plus 0.05%, and 0.01% plus 0.01%. The expected percent mycelial growth inhibitions (Iexp) were determined using the following formula according to Abbott (39): Iexp = X + Y − (XY/100), where X and Y are the percent inhibitions provided by B. subtilis (B11-128) and B. amyloliquefaciens (B11-144), respectively, when used alone. Levels of interactions were determined as interaction ratio (IR) = Iobs/Iexp, where Iobs is the experimentally determined observed inhibition provided by mixtures of B. subtilis (B11-128) and B. amyloliquefaciens (B11-144) culture filtrates. IRs of 0.5 to 1.5 were considered additive, IRs of >1.5 were considered synergistic, and IRs of < 0.5 were considered antagonistic, as described before (36, 40–42).

Heat and proteinase K treatment and adjustment of pH of CFs.

Stability of the culture filtrate to heat and proteinase was assayed as follows. Ten-milliliter culture filtrates of B. subtilis (B11-128) and B. amyloliquefaciens (B11-144) were autoclaved at 121°C (15 lb/in2) for 20 min. Autoclaved culture filtrates were cooled to room temperature and stored at 4°C until further use. For proteinase treatment, 1 ml culture filtrate and LB as a negative control were treated with 100 μg ml−1 proteinase K (P-2308; Sigma-Aldrich) at 37°C for 4 h. The pHs of culture filtrates of B11-48, B11-128, and B11-44 were adjusted to 3.0, 4.0, 5.0, 6.0, 7.0, 8.0, and 9.0 with HCl or KOH. Each pH treatment was replicated four times and tested against A. alternata in a 96-well plate as described above.

Fungicidal and fungistatic assays.

Two hundred microliters of A. alternata spores (104 spores ml−1 in PDB) was treated with LB (control) or culture filtrates of B11-48, B11-128, and B11-144 (10% final dilution) for 24 h in eight 1.5-ml Eppendorf tubes, which were divided into two groups. Spores in one group were not processed further, whereas spores in the second group were washed five times with 1 ml of PDB and then centrifuged at 500 × g for 5 min. Washed spores were resuspended in PDB, incubated for another 24 h in 96-well plates, and examined for spore germination and growth.

Detached-leaf and in planta Alternaria inhibition assays.

The efficacy of CFs was assessed in detached-leaf and whole-plant assays. In the detached-leaf assays, healthy leaves from greenhouse-grown poinsettia, dieffenbachia, and tomato plants were immersed in 15% Clorox for 2 s and immediately rinsed thoroughly with sterile water three times. Leaves were blot dried lightly and arranged randomly on two layers of moist Whatman filter papers in humid chambers. Leaves were subjected to the following treatments: (i) water as a control, (ii) 2% LB in H2O as a control followed by inoculation with A. solani (tomato) or A. alternata (poinsettia and dieffenbachia), or (iii) 2% CFs in H2O followed by inoculation with A. solani (tomato) or A. alternata (poinsettia and dieffenbachia). A. solani and A. alternata inocula consisted of a 0.5-cm-diameter agar plug from a 5-day-old culture. Leaves were arranged in a randomized block design and incubated at 22°C under continuous light. At 7 days postinoculation, lesion diameters were measured, and data were statistically analyzed using a t test.

In planta assays were performed using the impatiens-A. alternata host-pathogen system. Five-week-old plants of Impatiens walleriana were grown in a greenhouse. Each treatment consisted of 30 plants arranged in a completely randomized design. Treatments were as follows: (i) water control spray, (ii) 2% LB in H2O control application followed by A. alternata inoculation, (iii) 2% culture filtrate in H2O application followed by A. alternata inoculation, (iv) A. alternata inoculation followed by spray with 2% culture filtrate in H2O, (v) 2% culture filtrate in H2O was applied both pre- and postinoculation with A. alternata, and (vi) azoxystrobin (Heritage) spray at the recommended rate of 0.75 mg ml−1 followed by A. alternata inoculation. Ten days later, the number of lesions on each plant was counted and the data were analyzed for significance of differences between treatments using t test.

LC-ESI-MS/MS analyses.

For LC-MS/MS analyses, cyclic lipopeptides in the culture filtrate were precipitated by adjusting the pH to 2.0 with 6 N HCl as described previously (43). Acid-precipitated lipopeptides were extracted with either water or methanol and tested for anti-Alternaria activity using a paper disk diffusion assay. Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) and liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) were performed on a Thermo Scientific LCQ Deca mass spectrometer equipped with an electrospray source (Thermo Scientific) operated in positive-ion mode. The LC system was an Agilent 1200. Mobile phase A was water containing 0.1% formic acid, and mobile phase B was acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid. Five microliters of each sample was injected onto a Thermo Scientific Hypersil Gold aQ (C18 column, 2.1-μm internal diameter, 150-mm length, 3-μm particle size, 100-Å pore size). Peptides were eluted directly off the column into the LCQ system using a gradient of 2 to 98% mobile phase B over 30 min, with a flow rate of 0.2 ml/min. The total run time was 40 min. The electrospray ionization (ESI) source operated with a spray voltage of 4 kV and a capillary temperature of 250°C. For LC-MS, the ion trap was scanned from m/z 300 to 2000 in positive-ion mode. For LC-MS/MS, the scan sequence of the mass was programmed for a full scan recorded between 300 and 2,000 Da and an MS/MS scan to generate product ion spectra to determine fragmentation ions in consecutive instrument scans of the four most abundant peaks in the spectrum. The collision-induced dissociation (CID) fragmentation energy was set to 35%.

RESULTS

Screening of extracellular culture filtrates of Bacillus species for inhibiting growth of Alternaria spp.

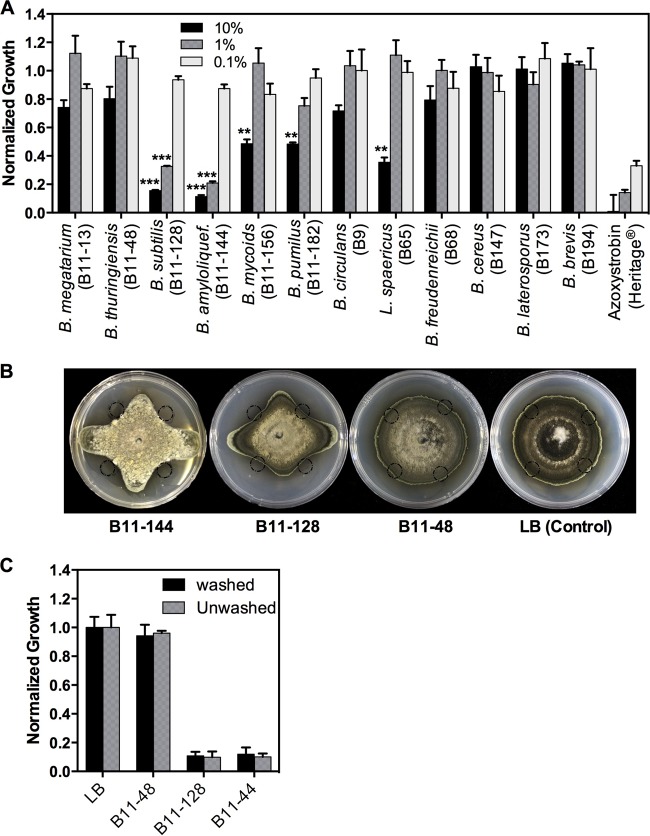

We first evaluated cell-free filter-sterilized CFs from bacterial isolates belonging to 12 different BCA species in vitro (Table 1). In initial screens, CFs were tested using three logarithmic serial dilutions (10%, 1%, and 0.1%) in a high-throughput antifungal assay in microtiter plates against three Alternaria species, A. solani, A. alternata, and A. brassicicola. There were substantial differences in antifungal activity between isolates, with some showing very strong activity and others showing no activity at all (Fig. 1A; see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). CFs from two isolates, B11-128 (B. subtilis) and B11-144 (B. amyloliquefaciens), showed the strongest inhibitory activity at the 10% and 1% dilution levels against all three Alternaria spp. (Fig. 1) (P < 0.001). These results were confirmed by the culture plate radial growth inhibition assays (Fig. 1B). CFs of three isolates, B11-156, B11-182, and B65, displayed moderate activities at 10% dilutions (P < 0.01) but no inhibition at the 1% level, whereas CFs of the remaining isolates did not display any significant activity (Fig. 1A). Since all three Alternaria species responded very similarly to CF of each of the tested isolates, data for only A. alternata are presented in Fig. 1. Since CFs of isolates B11-128 and B11-144 showed the strongest activity, they were selected for further detailed analyses.

FIG 1.

Screening of soil-inhabiting bacterial species for controlling Alternaria alternata in vitro. (A) Effects of different dilutions (10%, 1%, and 0.1%) of culture filtrates (CFs) of the bacterial isolates indicated on the x axis on the in vitro growth of A. alternata. Growth was normalized to growth in a no-CF control, considered 100%. Azoxystrobin (Heritage), a broad-spectrum fungicide, was used as a positive control, and its 10%, 1%, and 0.1% levels correspond to 5.0, 0.5, and 0.05 μg ml−1 active ingredient in the assay solution. *** and **, statistically significant differences at P values of <0.001 and <0.01, respectively, compared to corresponding dilutions of B11-48. (B) Representative pictures showing the effects of CFs of B. amyloliquefaciens isolate B11-144 and B. subtilis isolates B11-128 (strong inhibition) and B11-48 (no inhibition) on growth of A. alternata on PDA plates. CF (25 μl) was applied at the four locations indicated by circles on the plates. Control plates contained only LB. Pictures were taken 10 days after the start of the experiment. (C) Fungicidal assays. Spores treated with 2% CFs for 24 h did not resume growth when washed of culture filtrates, showing that CFs of B11-128 and B11-144 have a fungicidal mode of action. (For B11-128, washed versus unwashed, P = 0.699 by t test [n = 4]; for B11-148, washed versus unwashed, P = 0.515 by t test [n = 4]). Error bars are standard errors of the means (SEM).

Antifungal compounds usually display two modes of action, fungistatic or fungicidal, in inhibiting fungal growth. The fungistatic mode of action is characterized by reversible growth inhibition where fungi resume growth after removal of the antimicrobial compound. In contrast, in the fungicidal mode of action, cells are killed and, therefore, there is no regrowth after the antimicrobial compound is removed. CFs of B11-128 and B11-144 were assayed for fungistasis or fungicidal activity. Transfer of culture filtrate-treated Alternaria spores to culture filtrate-free medium did not result in resumption of fungal growth (Fig. 1C). These results indicated that the culture filtrates of B11-128 and 144 have fungicidal activity.

In vitro dose-response evaluation of the culture filtrates of B. subtilis and B. amyloliquefaciens against A. alternata.

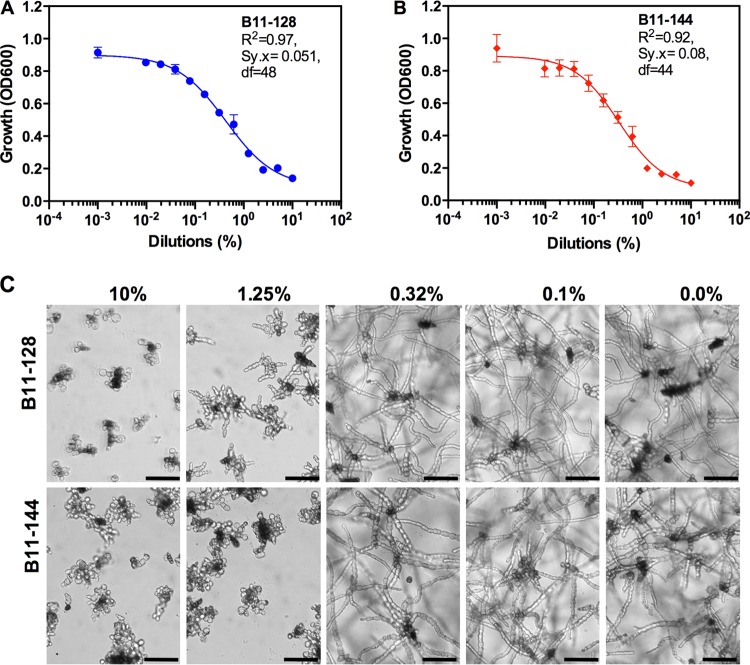

To determine the dose-response spectra of isolates B11-128 and B11-144, their CFs were tested using 2-fold serial dilutions ranging from 10 to 0.01% in vitro in microtiter plates. Fitting of logistic models to the dose-response data followed typical sigmoidal curves, indicating that culture filtrates of B11-128 and B11-144 contain an active ingredient(s) that inhibits Alternaria growth in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2). Goodness-of-fit analyses revealed very high r2 and low sum of standard errors (Sy.x, indicated on Fig. 2A and B), showing that parameter fits of sigmoid curves to the dose-response data for B11-128 and B11-144 were significant. The sigmoid curve fits of the remaining bacterial culture filtrates were not significant, and these isolates did not display a strong dose-dependent response.

FIG 2.

Dose-response analyses of culture filtrates of B. subtilis (B11-128) and B. amyloliquefaciens (B11-144). (A and B) Best-fit curves were generated from dose-response data consisting of 10, 5, 2.5, 1.25, 0.62, 0.31, 0.165, 0.078, 0.039, 0.019, 0.009, and 0.004% culture filtrates using the sigmoidal (four-parameter logistic) model. r2 values for measuring goodness of fit of the curves are shown on the graphs. Sy.x, Sum of standard errors. (C) Representative pictures of A. alternata hyphae in a microtiter plate treated with the indicated dilutions of B11-128 and B11-144 culture filtrates. Pictures were taken 5 days after incubation. Bars = 100 μm.

IC50s, which were calculated from the dose-response logistic curves for B11-128 and B11-144 or estimated from Fig. 1 for the remaining isolates, are given in Table 1. CFs of isolates B11-128 and B11-144 displayed approximately 25- to 45-fold-higher IC50s than those of B11-182, B11-156, and B65, the next group of isolates that displayed some antimicrobial activity. Antifungal activities of B11-128 and B11-144 were compared to that of the broad-spectrum fungicide azoxystrobin (Heritage; Syngenta). Based on their IC50s, B11-128 and B11-144 had approximately 3.5- to 5.5-fold-lower activities than azoxystrobin when tested at the recommended rate (Table 1). Similarly, MIC values of B11-128 and B11-144 were about 7- to 12-fold higher than that of azoxystrobin. Overall, these results indicate that culture filtrates of these two different soil-inhabiting bacterial species displayed strong antifungal activity against Alternaria spp. in vitro.

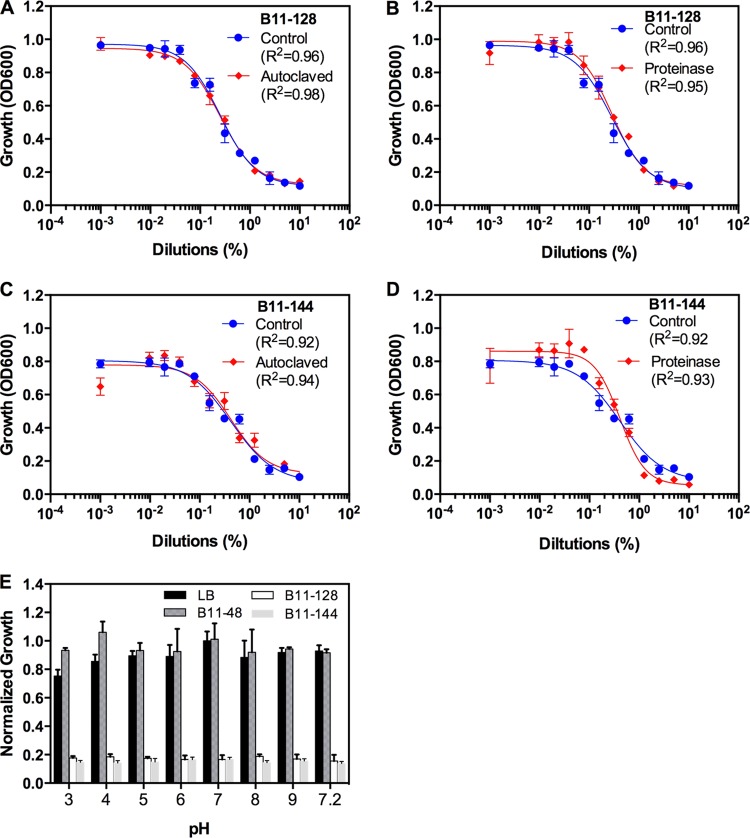

Heat, proteolysis, and pH stability of the bioactive metabolite(s) of B. subtilis and B. amyloliquefaciens.

Antimicrobial activity of various Bacillus spp. is attributed to a combination of secondary metabolites and/or proteinaceous antimicrobial enzymes and peptides (13, 21). In general, proteinaceous components, especially enzymes, are heat labile and prone to degradation by proteases, whereas secondary metabolites are usually not. In order to determine the structural identity of the bioactive compounds from B11-128 and B11-144, CFs from these two isolates were autoclaved and their anti-Alternaria activity compared to that of nonautoclaved CFs. Statistical comparison of dose-response curves did not reveal any significant difference between autoclaved and nonautoclaved CFs of B11-128 (P = 0.48) or B11-144 (P = 0.67) (Fig. 3A and B; Table 2). Similarly, the anti-Alternaria activity of neither isolate was affected by proteinase K treatment (Fig. 3B and D; Table 2). Proteinase K treatment alone did not affect the growth of Alternaria (data not shown). These analyses indicate that the anti-Alternaria activity of B11-128 and B11-144 is likely not proteinaceous.

FIG 3.

Effects of heat and proteinase K treatment and pH on the anti-Alternaria activity of culture filtrates of B. subtilis (B11-128) and B. amyloliquefaciens (B11-144). (A to D) Best-fit curves were generated from dose-response data using the sigmoidal (four-parameter logistic) model as for Fig. 2. Curve fits of control and treatment (autoclaved or proteinase treated) were compared using the null hypothesis that a single curve fits both data sets. P values for significance of tests are 0.485 (A), 0.285 (B), 0.678 (C), and 0.893 (D), which are all nonsignificant (P > 0.05). r2 values for measuring goodness of fit of the curves are shown on the graphs. (E) For assaying the effect of pH on anti-Alternaria activity, growth inhibition was normalized to a no-CF control at pH 7.0. Statistical comparison showed no significant effect of pH on the activities of B11-128 and B11-144 (P > 0.1). Data shown are means ± SEM (n = 4).

TABLE 2.

Effects of heat and proteinase treatment on the antifungal activity of culture filtrates of isolates B11-128 and B11-144

| Isolate | IC50a |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Autoclaved | Proteinase treated | |

| B11-128 | 0.22 (0.19–0.24) | 0.26 (0.22–0.31) (P > 0.48) | 0.36 (0.26–0.51) (P > 0.51) |

| B11-144 | 0.39 (0.24–0.52) | 0.44 (0.30–0.68) (P > 0.67) | 0.41 (0.31–0.52) (P > 0.98) |

Data shown are means (with 95% confidence intervals in parentheses), expressed as percent (vol/vol) concentration of bacterial culture filtrates in the assay solution, which were predicted from logistic curves fitted to the dose-response data for each culture filtrate tested against A. alternata in vitro. P values are comparing means for heat or proteinase treatments to untreated control means.

Both B11-128 and B11-144 cultures displayed a pH (∼7.35) that was slightly raised from the initial pH 7.0 at the start of the culture. To rule out the possibility that the observed antimicrobial activity was simply due to a change in pH, we assayed culture filtrates of B11-128 and B11-144 at different pH levels ranging from 3.0 to 9.0. Except for a slight reduction in growth at pH 3.0, the growth of Alternaria was not significantly affected by pH gradients ranging from pH 4.0 to 9.0 in untreated control (Fig. 3E). Culture filtrates from both B11-128 and B11-144 were equally active at all the tested pH levels. Microscopic examination of cultures also showed abnormal growth at all pH levels, similar to what is shown in Fig. 2C. These results indicate that the culture filtrates of these two BCAs are active at a wider range of pH.

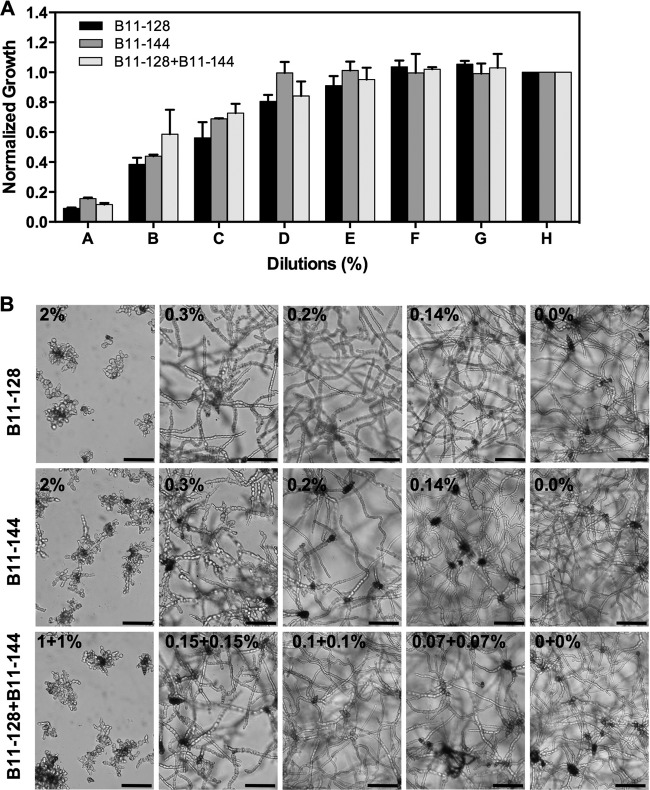

Interaction of bacterial culture filtrates with each other.

Antimicrobial compounds in mixtures may interact synergistically, additively, or antagonistically in inhibiting microbial growth. To find out how the culture filtrates of B11-128 and B11-144 would interact in controlling A. alternata, they were assayed alone and in a 1:1 (vol/vol) mixture at different concentration levels, ranging from very high (IC90) to very low (IC2.5). High and low concentration levels were chosen to capture very extreme levels, if any, of antagonism and synergism, which tend to be affected by the tested concentrations of individual compounds (36). Figure 4 shows growth of A. alternata in the presence of CF mixtures or CF alone at each tested concentration. Mycelial growth inhibition caused by CF mixtures was not significantly different from the inhibition caused by each CF alone. Similarly, interactions ratios (IRs) (Iobserved/Iexpected) at all tested concentrations were within the range for an additive interaction (0.5 to 1.5) (Table 3) (39, 42, 44). These results show that bacterial culture filtrates produced by these two bacteria do not interact synergistically or antagonistically but are additive in that one can be replaced by the other.

FIG 4.

Interaction of B. subtilis (B11-128) and B. amyloliquefaciens (B11-144) culture filtrates in controlling A. alternata. (A) Bar graph comparing effects of combining culture filtrates of B11-128 and B11-144 on A. alternata growth. CFs of B11-128 alone, B11-144 alone, and B11-128 and B11-144 combined were used, respectively, at the following percent dilutions: 2, 2, and 1 + 1 (bars A), 1, 1, and 0.5 + 0.5 (bars B), 0.3, 0.3, and 0.15 + 0.15 (bars C), 0.2, 0.2, and 0.1 + 0.1 (bars D), 0.14, 0.14, and 0.07 + 0.07 (bars E), 0.1, 0.1, and 0.05 + 0.05 (bars F), and 0.02, 0.02, and 0.01 + 0.01 (bars G). Growth data were normalized to the growth in an untreated control. Error bars are SEM. (B) Micrographs showing effects of B11-128 and B11-144 used individually or in mixtures at the indicated dilutions. Bars = 100 μm.

TABLE 3.

Interaction of culture filtrates of B. subtilis (B11-128) and B. amyloliquefaciens (B11-144) in inhibiting A. alternata

| Concn (%) of CF combination (B11-128 + B11-144)a | Iexpb | Iobsb (mean ± SEM) | IRc (Iobs/Iexp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1.0 + 1.0 | 69.8 | 88.4 ± 1.11 | 1.3 |

| 0.5 + 0.5 | 57.8 | 41.4 ± 1.64 | 0.7 |

| 0.15 + 0.15 | 43.8 | 27.3 ± 0.63 | 0.6 |

| 0.1 + 0.1 | 27.8 | 15.8 ± 0.96 | 0.6 |

| 0.07 + 0.07 | 9.8 | 4.9 ± 0.79 | 0.5 |

| 0.05 + 0.05 | 4.9 | 2.3 ± 0.13 | 0.5 |

CFs were mixed in equal proportions at the indicated concentrations.

Iexp (expected percent inhibition assuming an additive interaction) was calculated according to the equation (39) Iexp = X + Y − (XY/100), where X and Y are the percent inhibitions provided by B. subtilis (B11-128) and B. amyloliquefaciens (B11-144) when used alone. Iobs is the observed inhibition provided by mixtures of B. subtilis (B11-128) and B. amyloliquefaciens (B11-144) culture filtrates.

In vivo control of Alternaria spp. by culture filtrates of B. subtilis and B. amyloliquefaciens.

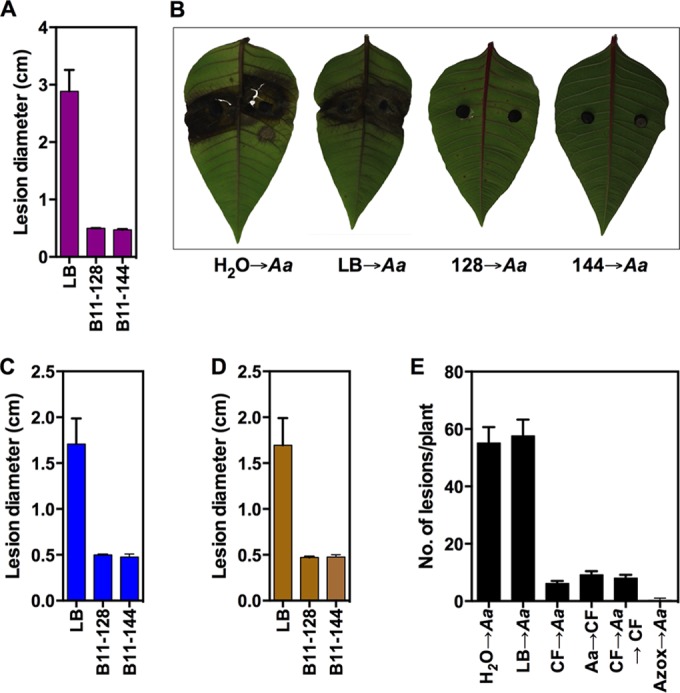

To determine the in vivo anti-Alternaria activity of isolates B11-128 and B11-144, we conducted two sets of experiments using detached-leaf and whole-plant assays with four different plant species. In detached-leaf assays, culture filtrates of B11-128 and B11-144 were tested with regard to preventing Alternaria lesion expansion on poinsettia, dieffenbachia, and tomato leaves. B11-128 and B11-144 culture filtrates (2% in H2O) completely inhibited expansion of lesions produced by A. alternata on poinsettia and dieffenbachia and by A. solani on tomato leaves (Fig. 5A to D). Since B11-128 and B11-144 produced similar results, we tested only B11-128 on whole plants. In whole-plant assays, we assayed the effect of timing of spraying the B11-128 culture filtrate either before, after, or both before and after inoculation with A. alternata. Disease severity was assessed as the number of lesions per plant. All treatments significantly reduced the number of lesions per plant compared to that with a water or 2% LB spray control (Fig. 5E). When applied preinoculation, culture filtrate reduced the number of lesions slightly more (89%) than when sprayed postinoculation (84%). The disease reduction effect of spraying CF both pre- and postinoculation (86%) was statistically similar (P > 0.05) to that of spraying CF preinoculation (CF spray followed by Alternaria inoculation) or postinoculation (Alternaria inoculation followed by CF spray). Spraying culture filtrate alone did not produce any undesirable traits such as lesions or chlorosis on leaves.

FIG 5.

In vivo control of Alternaria spp. by culture filtrates from B. subtilis (B11-128) and B. amyloliquefaciens (B11-144). (A to D) Results of detached-leaf assays; (E) results of whole-plant assays. (A, C, and D) Bar graphs showing average lesion sizes caused by Alternaria spp. on poinsettia (A), dieffenbachia (C), and tomato (D). (B) Photographs showing control of A. alternata on poinsettia leaves. Pictures were taken 7 days postinoculation. Culture filtrates of B11-128 and B11-144 significantly reduced lesion sizes. (E) Bar graph showing number of lesions per plant in response to CFs from B11-128 and B11-144. H2O→Aa, water control application followed by A. alternata inoculation; LB→Aa, 2% LB control application followed by A. alternata inoculation; CF→Aa, 2% culture filtrate application followed by A. alternata inoculation; Aa→CF, A. alternata inoculation followed by 2% culture filtrate application; CF→Aa→CF, 2% culture filtrate was applied both pre- and postinoculation with A. alternata; Azox→Aa, Azoxystrobin (Heritage) spray followed by A. alternata inoculation. Error bars indicate standard errors of the means.

Identification of bioactive compounds using LC-ESI-MS/MS analysis.

Since the biological activity of isolates B11-128 and B11-144 against Alternaria spp. was not diminished by autoclaving and proteinase treatment (Fig. 3), these active compounds could be cyclic lipopeptides (CLPs). To test this hypothesis, CLPs of B11-128 and B11-144 (bioactive) and of B11-48 (inactive) were acid precipitated and extracted with methanol. Antifungal tests with methanol-extracted fractions of B11-128 and B11-144 showed inhibition of A. alternata, and this activity was maintained for at least 5 weeks on petri dishes (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). No inhibition was observed with B11-48 or methanol only as control. These results suggested that cyclic lipopeptides are likely responsible for the anti-Alternaria activity of B11-128 and B11-144.

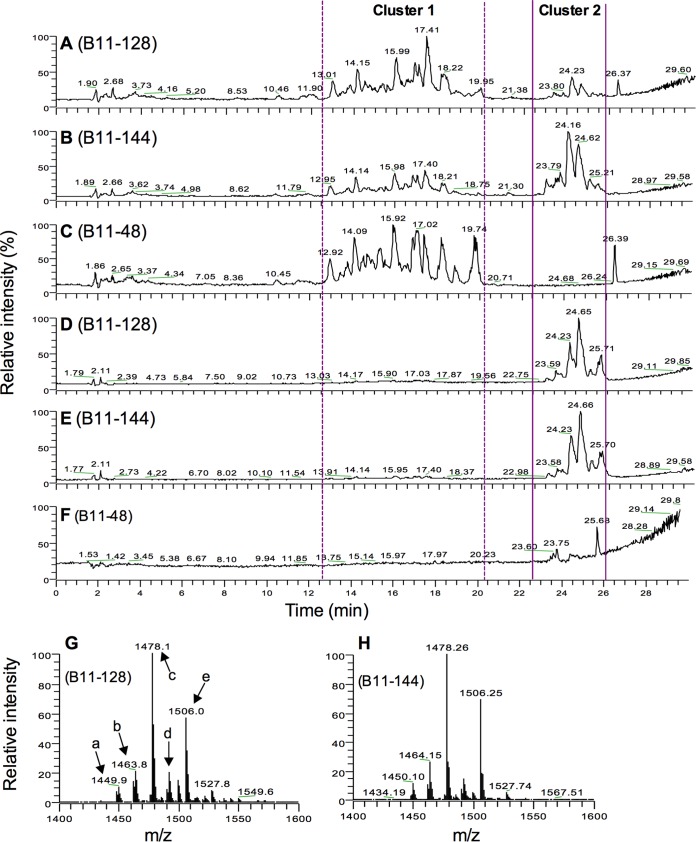

To determine the chemical composition of CLPs produced by B11-128 and B11-144, we performed LC-MS and LC-MS/MS analyses on their culture filtrates. Comparative analyses of the LC-MS ion chromatograms of the water- and methanol-soluble fractions of acid-precipitated culture filtrates revealed two distinct clusters of peaks with retention times of 12 to 20 min (cluster 1) and 23 to 26 min (cluster 2) (Fig. 6). Most of the peaks in cluster 2 were present only in the CFs of the bioactive isolates B11-128 and B11-144 and not in that of the inactive isolate B11-48. Interestingly, in the methanol-soluble fractions, several peaks were also observed at the 23- to 26-min retention time, which were enriched in the bioactive isolates compared to the inactive isolate (Fig. 6).

FIG 6.

(A to F) Total ion current chromatograms of water-soluble (A, B, and C) and methanol-soluble (D, E, and F) fractions of acid-precipitated lytic peptides of B. subtilis (B11-128), B. amyloliquefaciens (B11-144), and B. thuringiensis (B11-48). Two distinct clusters of peaks were observed at retention times of 12 to 20 min (cluster 1) and 23 to 26 min (cluster 2). Cluster 1, which was observed only in water-soluble fractions, displayed similar peak patterns in the bioactive (B11-128 and B11-144) and inactive (B11-48) strains. In contrast, cluster 2 peaks were present in the bioactive culture filtrate but not in the inactive culture filtrate. (G and H) Mass spectra (m/z) displaying the overall distribution of water-soluble cyclic lipopeptides in CFs of B. subtilis (B11-128) and B. amyloliquefaciens (B11-144). The mass spectra correspond to an average of cluster 2 (retention time, 23 to 26 min). In panel G, prominent peaks are labeled a to e.

Since cluster 2 displayed peaks with substantially higher intensity in the CFs of bioactive isolates, we hypothesized that the anti-Alternaria activity of these isolates could be associated with these peaks. To determine the nature of compounds representing these peaks, we further analyzed the water-soluble and the methanol-soluble crude lipopeptide fractions of B11-128, B11-144, and B11-48 using LC-MS analysis. Peaks with any significantly higher intensity above the background were not observed in B11-48 (data not shown). Full-scan mass spectra (m/z 300 to 2000) of all peaks in cluster 2 in both the water-soluble and the methanol-soluble fractions of B11-128 and B11-144 revealed compounds in the m/z 1450 to 1510 range (Fig. 6G and H; see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). These peaks clustered around m/z 1450 (peak a), 1464 (peak b), 1478 (peak c), 1490 (peak d), and 1506 (peak e). These peaks were essentially similar between B11-128 and B11-144. A comparison to the known mass spectra of lipopeptides of Bacillus spp. revealed that the mass spectra observed in our studies correspond to fengycins, which in general display an m/z range of 1400 to 1600 (21, 26). The fengycin family members are structurally highly diverse and are roughly divided into at least two major groups, fengycins A (Ala at position 6) and B (Val at position 6) (26). Fengycin A and fengycin B in turn consist of structural variants, each characterized by differences in the length and saturation of fatty acid side chains. To further identify the type of fengycins that are present in B11-128 and B11-144, each peak was subjected to LC-MS/MS analyses. Spectra lists showing masses of product ions of these peaks are presented in Table S1 in the supplemental material and summarized in Table 4. MS/MS analyses of the two major peaks, peak c at m/z 1478 and peak e at m/z 1506, revealed the characteristic ion fragments of fengycin A (m/z 966 and 1082) and fengycin B (m/z 995 and 1109), respectively (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material) (26). In addition to these peaks, several other peak clusters were also observed in both fengycin A and fengycin B, which likely correspond to fragmentation products at different carbon positions along the fatty acid side chains. On the basis of the results of these analyses, we can conclude that different variants of both fengycin A and fengycin B are represented in B11-128 and B11-144 (Table 4). Several isoforms were detected with a 2-Da difference, suggesting that each group of fengycins detected in this study is likely a mixture of saturated and unsaturated fatty acids.

TABLE 4.

Cyclic lipopeptides identified in isolates B11-128 and B11-144 using LC-MS/MSa

| Identified lipopeptide |

m/z by ESI-MS (retention time, 23–26 min) |

Diagnostic fragment ions (m/z)b | Fatty acid type and amino acid at position 6 | Peak no. according to Fig. 6G | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B11-128 | B11-144 | ||||

| Fengycin A | 1450.94 | 966, 1082 | C15, Ala | a | |

| 1462.02 | 1462.17 | 966, 1082 | C16, Ala | b | |

| 1463.95 | 1464.15 | 966, 1082 | C16, Ala | b | |

| 1465.89 | 966, 1082 | C16, Ala | b | ||

| 1478.06 | 1478.26 | 966, 1082 | C17, Ala | c | |

| 1480.77 | 966, 1082 | C17, Ala | c | ||

| Fengycin B | 1490 | 1490.06 | 995, 1109 | C16, Val | d |

| 1491.86 | 1492.71 | 995, 1109 | C16, Val | d | |

| 1506.12 | 1506.25 | 995, 1109 | C17, Val | e | |

| 1507.8 | 1507.76 | 995, 1109 | C17, Val | e | |

Cluster 1 (Fig. 6) was present only in water-soluble fractions. A majority of the peaks in this cluster were present both in the bioactive B11-128 and B11-144 strains and in the inactive B11-48 (see Fig. S5 in the supplemental material). A peak with m/z 1100.63 was present in both B11-128 and B11-144 but not in B11-48, suggesting that this peak might represent a compound(s) that might be contributing to the antimicrobial activities of B11-128 and B11-144. In B11-128 and B11-144, this peak eluted at retention times of 17.34 and 17.48 min, respectively. The identity of this compound could not be ascertained with our current MS/MS analysis. However, future work will be performed to identify the compound.

DISCUSSION

The application of culture filtrates for controlling foliar diseases has several advantages over using living biological control organisms. Under natural conditions, most biological control agents are found in the rhizosphere as free-living organisms or closely associated with roots of plants. Consequently, they are adapted to the ecological conditions of soil, and therefore, commercial biological control products may not be suitable or as effective in controlling foliar diseases (32). Since many Bacillus BCA species secrete a variety of antimicrobial compounds, it is possible to harvest these compounds from in vitro culture of BCAs and use them ex vivo for control of foliar diseases. In this study, we screened culture filtrates of different bacterial species recovered from the rhizosphere of flowering plants for inhibiting Alternaria spp. Several of the bacterial BCAs used in this study were previously shown to inhibit growth of the soilborne plant pathogen Rhizoctonia solani, which is primarily a root pathogen (31). However, the activity of these bacterial isolates against Alternaria has not been tested before. We showed that of the 12 total BCA species tested, cell-free culture filtrates of only B. subtilis and B. amyloliquefaciens were highly potent and efficacious in controlling foliar diseases caused by three economically important Alternaria spp. This is consistent with the well-established observations that only a fraction of rhizosphere bacteria are beneficial (45) and that most strains that produce multiple cyclic lipopeptides and are antibacterial belong to B. subtilis or B. amyloliquefaciens (46).

We demonstrated that culture filtrates of B. subtilis and B. amyloliquefaciens were effective in controlling Alternaria pre- and postinoculation, suggesting that they have both protective and curative activities. Most fungicides used in controlling plant diseases are aimed at preventing infection (47). When present on aerial plant surfaces or in the rhizosphere, protective fungicides prevent infection by inhibiting spore germination, germ tube elongation, and mycelial growth. Curative fungicides, on the other hand, are absorbed by plant tissues and display fungicidal activity against the already-established fungal hyphae. Postinoculation control by culture filtrates in this study suggests that some antifungal compounds produced by Bacillus spp. might be absorbed by plant tissues and translocated, at least locally, to the already-established infection hyphae of A. alternata. Future experiments focused on the translocation of fengycins and other CLPs in plant tissues could provide insights as to whether this hypothesis is true. It is also possible that the postinoculation inhibition of Alternaria could have resulted from the induced resistance in plants caused by fengycins or other CLPs, as was reported for other plants (48–51). Since culture filtrates of Bacillus spp. contain different antimicrobial compounds, it is safe to suggest that metabolites with different modes of action will likely target different physiological and developmental processes in the target pathogen. For example, Bacillus spp. secrete various antibiotics, such as iturins, fengycins, and mycosubtilins, with different modes of action and different molecular targets (14, 17, 19, 20, 49, 52). This is consistent with different classes of antimicrobial compounds that have different modes of actions because they interfere with different cellular and physiological processes of the target organisms (47).

The mode of action of BCAs includes direct antagonism, competition for nutrients, and activation of induced systemic resistance (ISR) in the host plant (45, 53–55). Genetic and biochemical studies showed that antimicrobial activities of BCA might be due to several different metabolites, including fengycin and surfactin-type lipopeptides produced by Bacillus spp. (17, 27, 49–51, 55, 56). In our in vitro studies, we observed direct inhibition of mycelial growth by the culture filtrate of BCA, and probably this is the most likely mechanism by which these BCAs control Alternaria. However, when sprayed on plants, culture filtrates not only might inhibit Alternaria spp. by direct antagonism but also will most likely cause ISR, as was reported before against other plant pathogens (48–51).

Proteinaceous antimicrobial compounds such as peptides and proteins could be degraded by secreted proteinases produced by the target pathogen species (57–59) or host plants (60). In our analyses, protein inactivation by autoclaving and proteinase K treatment did not reduce the activity of culture filtrate of B. subtilis or B. amyloliquefaciens, suggesting that the anti-Alternaria activity likely does not involve enzymes. Bioactive Bacillus spp. are known to produce a mixture of cyclic lipopeptides belonging primarily to the iturin, surfactin, and fengycin families (18, 24, 26–28). These peptides differ in the number and type of amino acids in the ring and in the length and type of fatty acid side chains. A combination of the ring amino acids and of fatty acid chains leads to tremendous diversity in lipopeptides produced by Bacillus spp. Using commercially available standards in our analyses, we did not detect iturins or surfactins in the CFs of bioactive isolates (data not shown), suggesting that these families do not contribute to the anti-Alternaria activities. In contrast, we found fengycins overproduced in the two bioactive BCAs. Detailed LC-MS and LC-MS/MS analyses suggested that similar to previous studies, the two bioactive BCAs explored in this studies also produced a complex mixture of fengycins. Fengycins produced by these two strains contained C15, C16, and C17 fatty acid side chains. This notion was supported by detailed comparison of the mass spectra, which showed that each peak cluster differed from the next cluster by 14 Da, which corresponds to the mass of a —CH2 group. Although both strains were dominated by fengycin A (m/z 1478) and fengycin B (m/z 1506) with C17 fatty acids, other fengycins with C15 and C16 fatty acids were also observed, suggesting that a mixture of different structural variants of fengycins likely act in concert in inhibiting Alternaria. Both bioactive strains used in this study produced similar fengycins, which could explain the additive nature of interaction of their culture filtrate. In contrast to a recent report where fengycin in combination with iturin was shown to display additive activity against Alternaria, in our analyses we did not detect iturins, suggesting that the antimicrobial activity of BCAs in our studies is mainly due to fengycins. It is also possible that trace amounts of iturins could still be present in the CFs of these two BCAs. Fengycins are lytic peptides, which are proposed to cause cell death by interfering with membrane permeability (24, 26, 27), and the antimicrobial activities of fengycins are dependent on the lipid composition of fungi (29). In a fungistatic versus fungicidal comparison test, we found that culture filtrates of both B11-128 and B11-144 were fungicidal, which most likely occurred due to interference with membrane integrity. Microscopic examination of Alternaria treated with culture filtrates of B11-128 and B11-144 revealed abnormal hyphal swelling, indicating that cell wall and/or membrane function might be adversely affected by fengycins.

Many fungicides interfere with the function of single specific molecular targets in microbial cells (47). Target organisms can develop resistance to single-site antimicrobial compounds very rapidly, and in most cases resistance is traced back to a single genetic mutation in the target molecule that leads to a loss of recognition or metabolism of the antimicrobial compound. For example, A. solani has developed resistance to several commonly used fungicides, including azoxystrobin, due to single amino acid changes in the target molecules (8, 11, 61–63). Resistance is often attributed to frequent use of antimicrobial compounds of the same class. Combinations of mixtures with different modes of actions can reduce the probability of resistance development, because a pathogen would have to develop resistance to all components in a mixture simultaneously (64). In our experiments focused on investigating the interaction of culture filtrates of B. subtilis and B. amyloliquefaciens, we did not detect any synergism, which is consistent with our LC-MS analyses showing that isolates of both B. subtilis and B. amyloliquefaciens produced primarily fengycins, which have previously been suggested to inhibit Alternaria (29, 30).

Conclusions.

Several Alternaria spp. have developed resistance to important fungicides, and identification of new and eco-friendly methods/products is needed. In a screen of 12 different soil-inhabiting bacterial species, two BCAs with highly efficacious and potent activity against Alternaria were found. The active ingredient(s) is most likely a combination of antimicrobial lytic peptides, dominated by fengycins, that are resistant to autoclaving and proteinase treatment. In conclusion, here we show that culture filtrates of these two bacterial species can be used for controlling foliar disease caused by Alternaria spp. both pre- and postinfection. These results offer a viable and sustainable alternative to using live bacteria for controlling diseases caused by Alternaria spp.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was partially supported by funds to G.S.A. from the Florida Agriculture Experiment Station of the Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences at the University of Florida (FLA-APO-005155) and the Division of Sponsored Programs (00108615).

Funding Statement

This work was partially supported by funds to G.S.A. from the Florida Agriculture Experiment Station of the Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences at the University of Florida (FLA-APO-005155) and the Division of Sponsored Programs (00108615).

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AEM.02662-15.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rotem J. 1994. The genus Alternaria: biology, epidemiology, and pathogenicity. APS Press, St. Paul, MN. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pasche JS, Gudmestad NC. 2008. Prevalence, competitive fitness and impact of the F129L mutation in Alternaria solani from the United States. Crop Prot 27:427–435. doi: 10.1016/j.cropro.2007.07.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosenzweig N, Atallah ZK, Olaya G, Stevenson WR. 2008. Evaluation of QoI fungicide application strategies for managing fungicide resistance and potato early blight epidemics in Wisconsin. Plant Dis 92:561–568. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-92-4-0561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fairchild KL, Miles TD, Wharton PS. 2013. Assessing fungicide resistance in populations of Alternaria in Idaho potato fields. Crop Prot 49:31–39. doi: 10.1016/j.cropro.2013.03.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Avenot HF, Michailides TJ. 2007. Resistance to boscalid fungicide in Alternaria alternata isolates from pistachio in California. Plant Dis 91:1345–1350. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-91-10-1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mallik I, Arabiat S, Pasche JS, Bolton MD, Patel JS, Gudmestad NC. 2014. Molecular characterization and detection of mutations associated with resistance to succinate dehydrogenase-inhibiting fungicides in Alternaria solani. Phytopathology 104:40–49. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-02-13-0041-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Avenot HF, van den Biggelaar H, Morgan DP, Moral J, Joosten M, Michailides TJ. 2014. Sensitivities of baseline isolates and boscalid-resistant mutants of Alternaria alternata from pistachio to Fluopyram, Penthiopyrad, and Fluxapyroxad. Plant Dis 98:197–205. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-04-13-0459-RE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gudmestad NC, Arabiat S, Miller JS, Pasche JS. 2013. Prevalence and impact of SDHI fungicide resistance in Alternaria solani. Plant Dis 97:952–960. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-12-12-1176-RE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Avenot H, Sellam A, Michailides T. 2009. Characterization of mutations in the membrane-anchored subunits AaSDHC and AaSDHD of succinate dehydrogenase from Alternaria alternata isolates conferring field resistance to the fungicide boscalid. Plant Pathol 58:1134–1143. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3059.2009.02154.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leiminger JH, Adolf B, Hausladen H. 2014. Occurrence of the F129L mutation in Alternaria solani populations in Germany in response to QoI application, and its effect on sensitivity. Plant Pathol 63:640–650. doi: 10.1111/ppa.12120. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pasche JS, Piche LM, Gudmestad NC. 2005. Effect of the F129L mutation in Alternaria solani on fungicides affecting mitochondrial respiration. Plant Dis 89:269–278. doi: 10.1094/PD-89-0269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bhattacharyya PN, Jha DK. 2012. Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR): emergence in agriculture. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 28:1327–1350. doi: 10.1007/s11274-011-0979-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Perez-Garcia A, Romero D, de Vicente A. 2011. Plant protection and growth stimulation by microorganisms: biotechnological applications of bacilli in agriculture. Curr Opin Biotechnol 22:187–193. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2010.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alvarez F, Castro M, Principe A, Borioli G, Fischer S, Mori G, Jofre E. 2012. The plant-associated Bacillus amyloliquefaciens strains MEP2 18 and ARP2 3 capable of producing the cyclic lipopeptides iturin or surfactin and fengycin are effective in biocontrol of sclerotinia stem rot disease. J Appl Microbiol 112:159–174. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2011.05182.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Danielsson J, Reva O, Meijer J. 2007. Protection of oilseed rape (Brassica napus) toward fungal pathogens by strains of plant-associated Bacillus amyloliquefaciens. Microb Ecol 54:134–140. doi: 10.1007/s00248-006-9181-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen XH, Scholz R, Borriss M, Junge H, Mogel G, Kunz S, Borriss R. 2009. Difficidin and bacilysin produced by plant-associated Bacillus amyloliquefaciens are efficient in controlling fire blight disease. J Biotechnol 140:38–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2008.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Romero D, de Vicente A, Rakotoaly RH, Dufour SE, Veening JW, Arrebola E, Cazorla FM, Kuipers OP, Paquot M, Perez-Garcia A. 2007. The iturin and fengycin families of lipopeptides are key factors in antagonism of Bacillus subtilis toward Podosphaera fusca. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 20:430–440. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-20-4-0430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Villegas-Escobar V, Ceballos I, Mira JJ, Argel LE, Peralta SO, Romero-Tabarez M. 2013. Fengycin C produced by Bacillus subtilis EA-CB0015. J Nat Prod 76:503–509. doi: 10.1021/np300574v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Velmurugan N, Choi MS, Han SS, Lee YS. 2009. Evaluation of antagonistic activities of Bacillus subtilis and Bacillus licheniformis against wood-staining fungi: in vitro and in vivo experiments. J Microbiol 47:385–392. doi: 10.1007/s12275-009-0018-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arguelles-Arias A, Ongena M, Halimi B, Lara Y, Brans A, Joris B, Fickers P. 2009. Bacillus amyloliquefaciens GA1 as a source of potent antibiotics and other secondary metabolites for biocontrol of plant pathogens. Microb Cell Fact 8:63. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-8-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen H, Chen ZJ, Zhang YJ, Zhu WY. 2014. Identification of antifungal peptides from Bacillus subtilis Bs-918. Anal Lett 47:2891–2899. doi: 10.1080/00032719.2014.928882. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Van Wees SCM, Van der Ent S, Pieterse CMJ. 2008. Plant immune responses triggered by beneficial microbes. Curr Opin Plant Biol 11:443–448. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2008.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kloepper JW, Ryu CM, Zhang SA. 2004. Induced systemic resistance and promotion of plant growth by Bacillus spp. Phytopathology 94:1259–1266. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO.2004.94.11.1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ongena M, Jacques P. 2008. Bacillus lipopeptides: versatile weapons for plant disease biocontrol. Trends Microbiol 16:115–125. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2007.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ali GS, El-Sayed AS, Norman DJ. 17 August 2015. Soluble and volatile metabolites of plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR): role and practical applications in inhibiting pathogens and activating induced systemic resistance (ISR). Adv Bot Res doi: 10.1016/bs.abr.2015.07.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang J, Liu J, Wang X, Yao J, Yu Z. 2004. Application of electrospray ionization mass spectrometry in rapid typing of fengycin homologues produced by Bacillus subtilis. Lett Appl Microbiol 39:98–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2004.01547.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Raaijmakers JM, De Bruijn I, Nybroe O, Ongena M. 2010. Natural functions of lipopeptides from Bacillus and Pseudomonas: more than surfactants and antibiotics. FEMS Microbiol Rev 34:1037–1062. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2010.00221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen H, Wang L, Su CX, Gong GH, Wang P, Yu ZL. 2008. Isolation and characterization of lipopeptide antibiotics produced by Bacillus subtilis. Lett Appl Microbiol 47:180–186. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2008.02412.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wise C, Falardeau J, Hagberg I, Avis TJ. 2014. Cellular lipid composition affects sensitivity of plant pathogens to fengycin, an antifungal compound produced by Bacillus subtilis strain CU12. Phytopathology 104:1036–1041. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-12-13-0336-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu J, Hagberg I, Novitsky L, Hadj-Moussa H, Avis TJ. 2014. Interaction of antimicrobial cyclic lipopeptides from Bacillus subtilis influences their effect on spore germination and membrane permeability in fungal plant pathogens. Fungal Biol 118:855–861. doi: 10.1016/j.funbio.2014.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Norman DJ, Dickstein ER, Yuen JMF. 2011. Inhibition of Rhizoctonia by endospore forming bacteria indigenous to landscape planting beds. Biocontrol Sci Technol 21:1133–1142. doi: 10.1080/09583157.2011.605516. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bloemberg GV, Lugtenberg BJ. 2001. Molecular basis of plant growth promotion and biocontrol by rhizobacteria. Curr Opin Plant Biol 4:343–350. doi: 10.1016/S1369-5266(00)00183-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yu SM, Lee YH. 2013. Effect of light quality on Bacillus amyloliquefaciens JBC36 and its biocontrol efficacy. Biol Control 64:203–210. doi: 10.1016/j.biocontrol.2012.11.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fravel DR. 2005. Commercialization and implementation of biocontrol. Annu Rev Phytopathol 43:337–359. doi: 10.1146/annurev.phyto.43.032904.092924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weller DM, Thomashow LS. 1994. Current challenges in introducing beneficial microorganisms into the rhizosphere, p 1–18. In O'Gara F, Dowling DN, Boesten B (ed), Molecular ecology of rhizosphere microorganisms: biotechnology and the release of GMOs. VCH, Weinheim, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gisi U. 1996. Synergistic interaction of fungicides in mixtures. Phytopathology 86:1273–1279. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lobeer JW. 1996. Synergism, antagonism, and additive action of fungicides in mixtures: introduction. Phytopathology 86:1261–1262. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ali GS, Reddy AS. 2000. Inhibition of fungal and bacterial plant pathogens by synthetic peptides: in vitro growth inhibition, interaction between peptides and inhibition of disease progression. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 13:847–859. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2000.13.8.847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Abbott WS. 1925. A method of computing effectiveness of an insecticide. J Econ Entomol 18:265–267. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lorito M, Woo SL, D'Ambrosio M, Harman GE, Hayes CK, Kubicek CP, Scala F. 1996. Synergistic interaction between cell wall degrading enzymes and membrane affecting compounds. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 9:206–213. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-9-0206. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ali GS, Harman GE, Reisch BI. 2003. The interaction of endochitinase, a synthetic peptide and resveratrol in controlling fungi in vitro. Eur J Plant Pathol 109:639–644. doi: 10.1023/A:1024797132744. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gisi U, Binder H, Rimbach E. 1985. Synergistic interactions of fungicides with different modes of action. Trans Br Mycol Soc 85:299–306. doi: 10.1016/S0007-1536(85)80192-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kim PI, Bai H, Bai D, Chae H, Chung S, Kim Y, Park R, Chi YT. 2004. Purification and characterization of a lipopeptide produced by Bacillus thuringiensis CMB26. J Appl Microbiol 97:942–949. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2004.02356.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kosman E, Cohen Y. 1996. Procedures for calculating and differentiating synergism and antagonism in action of fungicide mixtures. Phytopathology 86:1263–1272. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Beneduzi A, Ambrosini A, Passaglia LM. 2012. Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR): their potential as antagonists and biocontrol agents. Genet Mol Biol 35:1044–1051. doi: 10.1590/S1415-47572012000600020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mora I, Cabrefiga J, Montesinos E. 2015. Cyclic lipopeptide biosynthetic genes and products, and inhibitory activity of plant-associated Bacillus against phytopathogenic bacteria. PLoS One 10:e0127738. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0127738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.FRAC. 2015. FRAC Code List 2015: fungicides sorted by mode of action. Fungicide Resistance Action Committee. http://www.frac.info/publications.

- 48.Welling LL. 2001. Induced resistance: from the basic to the applied. Trends Plant Sci 6:445–447. doi: 10.1016/S1360-1385(01)02046-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jourdan E, Henry G, Duby F, Dommes J, Barthelemy JP, Thonart P, Ongena M. 2009. Insights into the defense-related events occurring in plant cells following perception of surfactin-type lipopeptide from Bacillus subtilis. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 22:456–468. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-22-4-0456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ongena M, Jourdan E, Adam A, Paquot M, Brans A, Joris B, Arpigny JL, Thonart P. 2007. Surfactin and fengycin lipopeptides of Bacillus subtilis as elicitors of induced systemic resistance in plants. Environ Microbiol 9:1084–1090. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2006.01202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rahman A, Uddin W, Wenner NG. 2015. Induced systemic resistance responses in perennial ryegrass against Magnaporthe oryzae elicited by semi-purified surfactin lipopeptides and live cells of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens. Mol Plant Pathol 16:546–558. doi: 10.1111/mpp.12209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Malanicheva IA, Kozlov DG, Efimenko TA, Zenkova VA, Katrukha GS, Reznikova MI, Korolev AM, Borshchevskaya LN, Tarasova OD, Sineokii SP, Efremenkova OV. 2014. New antibiotics produced by Bacillus subtilis strains. Microbiology 83:352–356. doi: 10.1134/S0026261714040110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Maksimov IV, Abizgil'dina RR, Pusenkova LI. 2011. Plant growth promoting rhizobacteria as alternative to chemical crop protectors from pathogens. Appl Biochem Microbiol 47:333–345. doi: 10.1134/S0003683811040090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.De Vleesschauwer D, Hofte M. 2009. Rhizobacteria-induced systemic resistance. Adv Bot Res 51:223–281. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2296(09)51006-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Choudhary DK, Johri BN. 2009. Interactions of Bacillus spp. and plants—with special reference to induced systemic resistance (ISR). Microbiol Res 164:493–513. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2008.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Leclere V, Bechet M, Adam A, Guez JS, Wathelet B, Ongena M, Thonart P, Gancel F, Chollet-Imbert M, Jacques P. 2005. Mycosubtilin overproduction by Bacillus subtilis BBG100 enhances the organism's antagonistic and biocontrol activities. Appl Environ Microbiol 71:4577–4584. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.8.4577-4584.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sreedhar L, Kobayashi DY, Bunting TE, Hillman BI, Belanger FC. 1999. Fungal proteinase expression in the interaction of the plant pathogen Magnaporthe poae with its host. Gene 235:121–129. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1119(99)00201-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Murphy JM, Walton JD. 1996. Three extracellular proteases from Cochliobolus carbonum: cloning and targeted disruption of ALP1. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 9:290–297. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-9-0290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Poussereau N, Creton S, Billon-Grand G, Rascle C, Fevre M. 2001. Regulation of acp1, encoding a non-aspartyl acid protease expressed during pathogenesis of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Microbiology 147:717–726. doi: 10.1099/00221287-147-3-717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Horger AC, van der Hoorn RA. 2013. The structural basis of specific protease-inhibitor interactions at the plant-pathogen interface. Curr Opin Struct Biol 23:842–850. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2013.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Peters RD, Drake KA, Gudmestad NC, Pasche JS, Shinners-Carnellcy T. 2008. First report of reduced sensitivity to a Qol fungicide in isolates of Alternaria solani causing early blight of potato in Canada. Plant Dis 92:1707–1707. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-92-12-1707B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wharton P, Fairchild K, Belcher A, Wood E. 2012. First report of in-vitro boscalid-resistant isolates of Alternaria solani causing early blight of potato in Idaho. Plant Dis 96:454–455. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-07-11-0544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rosenzweig N, Olaya G, Atallah ZK, Cleere S, Stanger C, Stevenson WR. 2008. Monitoring and tracking changes in sensitivity to azoxystrobin fungicide in Alternaria solani in Wisconsin. Plant Dis 92:555–560. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-92-4-0555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Samoucha Y, Gisi U. 1987. Use of two- and three-way mixtures to prevent buildup of resistance to phenylamide fungicides in Phytophthora and Plasmopara. Phytopathology 77:1405–1409. doi: 10.1094/Phyto-77-1405. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.