Abstract

Aim:

To compare “consultation” and “hybrid” models of consultation-liaison (CL) services provided to patients visiting the medical emergency outpatient services.

Materials and Methods:

Over the period of 18 months, two different models of consultation psychiatry services (July 2012 to March 2013-consultation model, April 2013 to December 2013 hybrid model) were compared. In the consultation model, the psychiatry resident was available on call to the internists. Whereas, for the hybrid model psychiatry resident was stationed in the medical emergency and was available to assess the patients directly requiring psychiatric evaluation.

Results:

During the first 9 months, 22,000 patients were evaluated in various emergency medical outpatient services, of which 383 (1.74%) were referred to the on-call psychiatry CL team. However, when the hybrid model was followed, the number of patients evaluated by the psychiatry resident increased to 594 out of 24,737 patients (2.4%) who reported to the emergency during the next 9 months period. There was a substantial increase in the proportion of cases with medical illnesses for which psychiatric consultation was sought, and a change in psychiatric diagnostic profile was observed too. When compared to the consultation model, the hybrid model was associated with greater use of medications, investigations, referrals and psychological measures in the emergency setting itself.

Conclusions:

Following a hybrid model in the medical emergency leads to an increase in the number of total psychiatric consultations and more extensive management of patients.

Keywords: Consultation-liaison psychiatry, emergency, India

INTRODUCTION

Last half a century has seen the steady growth of general hospital psychiatry services. The provision of mental health care services has moved from institutional based care to a more community and general hospital based care.[1,2,3] This has brought greater opportunities of close collaboration and liaison between the psychiatrists and other specialists. “Consultation-liaison (CL) psychiatry” has emerged as a discipline in its own right, which deals with patients at the interface of psychiatry and other specialties. Not only it deals with psychiatric disorders in patients with medical and surgical illnesses, but it also caters to issues in management of “difficult” patients, competency and ethics related issues, teaching about psychiatric conditions to the medical and surgical specialists and end of life care issues, etc.[4,5,6]

The provision of mental health care through CL psychiatry is quite varied across different centers and institutions.[7] As reviewed, various models of CL psychiatry are in operation for providing services.[3,8] The consultation model aims at the provision of mental health care by a psychiatry consultation team, which is called upon by the physicians for providing service in individual cases, and the patient remains the main focus of services provided. The liaison model aims at providing assistance to the physician for dealing with the patients with psychiatric issues. Here, the main focus of consultation is the consulting physician and in addition to providing consultation for the patient it also involves teaching mental aspects of patient's problem to the physician and the clinical team. The hybrid model has a psychiatrist as part of a multidisciplinary team. Other models include autonomous model wherein psychiatry, and other specialties run independently. In the bridge model, psychiatrist provides teaching to primary care physicians.[3] Comparative studies of the various models of CL services can help in understanding the nuances of a particular service model. Such comparative studies have been few.[7,9]

Although there are many studies from the West,[7,10] which have evaluated the psychiatric aspects of patients attending the emergency and accident department, there are only a few studies from developing countries and from Asia. A study evaluated 100 consecutive referrals from emergency (in which consultation model was followed) and reported a referral rate of 5.4% to the psychiatry services with 2.8 referrals per day.[11] Other studies from different parts of the country have reported a psychiatry referral rate of 1.5–2% with 0.9 psychiatry referrals per day.[12,13] Another study from India, which reviewed the register of general emergency reported that about 2.9% of patients had psychiatric illnesses.[14] A study from China reviewed psychiatric emergency consultations over 3 years period and reported psychiatric consultations for 2.3% of patients.[15] A recent study from Pakistan, which followed a hybrid model of consultation in which all patients attending the emergency were screened for psychiatric morbidity reported psychiatric morbidity in 2.3% of patients.[16] However, none of these studies was helpful in understanding the kind of CL model that needs to be followed in the emergency and accident setting.

Our center in North India had been following a consultation model of psychiatric service in the general hospital setting. Emergency medical and surgical services are among the major sources of referral for psychiatric consultation at our center. Till recently this service followed a consultation model in which call was sent by the physician/surgeon depending on their judgment for a psychiatric opinion. However, in recent time this model of service was replaced by having a psychiatrist stationed in the emergency to provide consultation to the physician. Hence, in this study we attempted to find out the impact of shifting from one model of psychiatric care to another in the emergency medical services. Accordingly, the aim of this study was to compare the profile of patients seen while following a consultation model vis-a-vis a hybrid model in providing services to patients visiting the medical emergency outpatient services.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study was conducted at the adult emergency medical services of Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh, which is a tertiary care hospital in North India. The emergency medical services cater to patients from all over North India. The patients attending the medical and surgical emergency facilities are usually referred from other hospitals and some of the patients come by themselves. All the patients are initially evaluated by a team of trainee doctors under the supervision of the specialists and are reviewed by the consultant. Emergency medical care is instituted and after stabilization of the medical condition, the patients are either admitted to the medical wards or advised to seek treatment from the outpatient services.

Prior to April, 2013, psychiatry consultation was sought at the discretion of the emergency medical treating team. The referrals were made on the basis of symptom profile of the patient, past or recent history of psychiatric disorder (including substance use disorder) and specific difficulties encountered in managing the patients. It was generally observed that in many cases which required psychiatric care, patients were asked to attend the psychiatry outpatient services. Because of heavy patient load, the medicine trainee residents had to do triage to attend to patients on priority whose life was in danger; hence, patients with psychiatric illnesses were not given priority.

In this model, a call was sent to the CL psychiatry service and the service was provided by a three-tier psychiatry CL team, comprising a trainee resident, a senior resident (qualified psychiatrist) and a consultant. The trainee resident would make the initial evaluation, and subsequently the patient was examined by a senior resident followed by the consultant. Based on the evaluation and consultation further management was carried out by the primary medical team in liaison with CL psychiatry team. The CL psychiatry team besides carrying out management would have some opportunity to discuss the mental health issues with the primary treating team.

From April, 2013, there was a change in the format of CL psychiatry service in order to improve the psychiatry services provided to the patients in the emergency setting. The trainee psychiatry resident was stationed for the period between 9.00 am and 8.00 pm in the emergency area to provide psychiatry consultation and management. All the patients attending the emergency medical outpatient were initially evaluated by the physician and at the slightest suggestion of a mental health issue the psychiatry resident evaluated the case. Unlike the past practice, the medical resident was not required to do a complete psychiatric evaluation and documentation before seeking a psychiatry consultation, but could ask the psychiatry resident posted in the emergency area to do the assessment and carry out management. If on evaluation the psychiatry resident felt the need for physical care, the medicine resident provided the same.

Upon evaluation by the trainee psychiatrist, irrespective of the presence or absence of a psychiatric diagnosis, the patient was also evaluated by the senior resident and consultant to formulate the final plan of management. This model of care facilitated discussion between emergency physician and the psychiatrists with regard to the interface of physical and mental issues in precipitating the diseases, worsening the physical illnesses, management of behavioral issues and treatment of common mental disorders. All the psychiatric diagnoses were made as per the International Classification of Diseases-10 criteria.[17]

The CL psychiatry team maintains a register of all the cases seen in the emergency setting since January 2010. The records are reviewed on a weekly basis for accuracy and completion. The data that is recorded include demographic details like age and gender of the patient; clinical details like medical and psychiatric diagnoses; the treatment provided and the outcome.

For the purpose of this study, data of patients seen by the CL psychiatry team in the emergency department during the period of 18 months (i.e. July 2012 to December 2013) was extracted from the CL psychiatry register. Change in the consultation model allowed us to compare the data between July 2012 and March 2013 and that between April and December 2013. The null hypothesis was that change in service model will not lead to increase in the number of psychiatric consultations or change in the diagnostic profile of patients seen in emergency.

RESULTS

During the study period, psychiatric consultation was provided to 977 patients from the emergency medical department. During the first 9 months (i.e. July 2012-March 2013 when consultation model was followed), 22,000 patients were evaluated in the emergency medical outpatient, of which 383 (1.74%) were referred to the CL psychiatry team. However, in the later 9 months (i.e. April-December, 2013, when hybrid model was followed), the number of patients evaluated increased to 594 out of 24,737 patients (2.4%) seen during this time frame. In terms of the absolute increase in number of patients, there was an increment of 55.1%. The increase in the percentage of cases seen during the second 9 months was significantly higher (χ2 with Yate's correction = 24.5, P < 0.001).

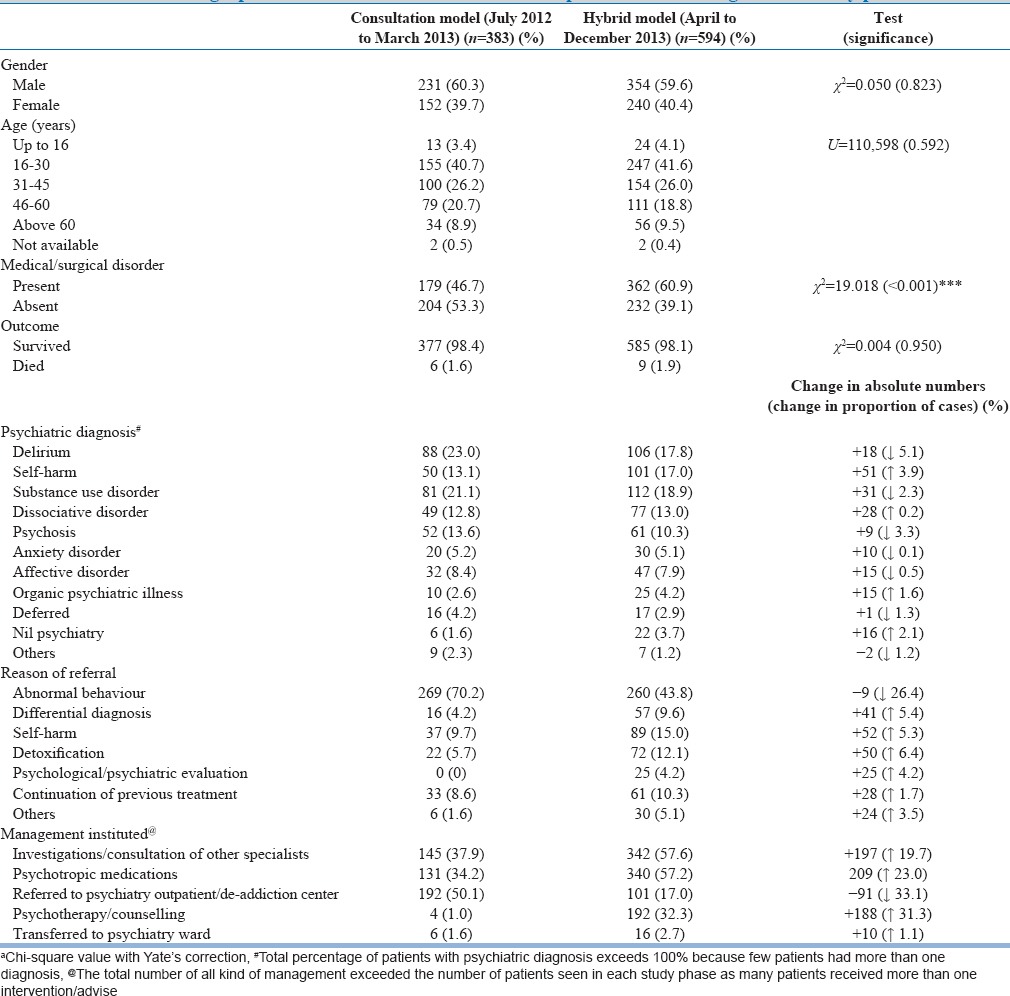

Table 1 depicts the sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the patients seen during the two phases of the study. Males comprised the majority of the patients in both the phases. While the hybrid model was followed, significantly higher consultations (P < 0.001) were sought for those with primarily medical illness and the consultations essentially those with psychiatric symptoms remained relatively stable in terms of absolute numbers. Of those for whom psychiatric consultation was sought nearly 98% of the cases survived.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients seen during the two study periods

The different disorders that were encountered during the two phases, that is, when the “consultation model” and the “hybrid model” were followed are shown in Table 1. There was an increase in the absolute number of cases during the phase when “hybrid model” was followed for all the diagnostic groups. Delirium was the most common diagnosis among the patients seen during the “consultation model” phase while substance use disorder was the most common diagnosis in the “hybrid model” phase. There was an increase in the proportion of cases referred for the self-harm and organic psychiatric illnesses (increase of proportion by 3.9% and 1.6%). Though there was an absolute increase in the number of cases of delirium during the “hybrid model” phase (106 vs. 88 cases), there was a marked decrease in the overall proportion of cases with delirium (decrease of 5.1%). In addition, there was a reduction in the proportion of cases of substance use disorder and psychosis during the “hybrid model” phase of the study.

As shown in Table 1, abnormal behavior was the most common reasons of referral during the “consultation model” phase, however during the “hybrid model” phase, there was increase in the proportion of cases evaluated for self-harm, detoxification, differential diagnosis and psychological evaluation. In the “hybrid model” phase, there was a substantial increase in the proportion of patients for whom investigations and consultation of other specialists were sought. Further, during the “hybrid model” phase there was an increase in the proportion of patients receiving psychotropic medications and a marked decrease in the proportion of patients for whom psychiatric outpatient referrals were advised. This suggested that more and more psychiatric referrals were actively managed in the emergency department, and fewer were being referred to the outpatient services.

DISCUSSION

It is now increasingly recognized that the prevalence of mental illness is quite high in the general population[18,19] and the prevalence is further higher in those with medical illness.[20,21,22] Although the “consultation model” of CL psychiatry provides an opportunity for mental health care to the patients in need, but the services are provided to only those who are judged to require the same by the physicians. Hence, in many patients the mental health issues are ignored because of the primary focus on the physical illness. Further, it involves an effort on the part of the physician to get a psychiatry consultation for the patient. Hence, a lot depends on the initiative of physicians and the response time of CL psychiatry team. In order to provide a holistic care to the patient’s, it is important to assess and address both the mental and the physical health issues at the same time. “Hybrid model” of CL psychiatry services involves having the psychiatrists as part of the treating team, who is available for care at all the time for assessment and management of the patient and also to provide knowledge about mental health issues to the physicians. Although different models of CL psychiatry have been proposed, in general, there is a lack of data which compares different models. Further, there are only limited numbers of studies from India[11,13,23] which have studied the psychiatry referral pattern arising from the emergency outpatient department. The present study was an attempt to fill this void.

The psychiatry referrals during the period when the “consultation model” was followed were 1.74%, which increased to 2.4% when the “hybrid model” was followed. This led to 55.1% increase in number of psychiatric consultations. This finding suggests that having an in-house psychiatrist increases the psychiatric consultations by almost 1½ times. Previous studies from our center and other parts of the country have reported that when the “consultation model” of CL psychiatry services is followed the numbers of referrals vary from 1.5% to 5.4%,[11,12,13,14] depending on the study site and the sample size of the emergency patients evaluated.

Besides an increase in the number of referrals, there was also a change in the diagnostic categories of patients seen in the emergency setting with a hybrid model of psychiatric care. Although delirium remained the by far the most common diagnostic category during the initial study period, referrals for patients presenting with self-harm emerged as the most common cause for referral in the latter part. By having an in house psychiatrist, more psychiatric consultation were sought for core psychiatric disorders like substance use disorders, dissociative disorders, anxiety disorders, affective disorders and psychotic disorders as shown by the increases in the absolute numbers and percentages of these cases. The increase in psychiatric consultation for these disorders suggests that possibly many of the patients with core psychiatric disorders who attend emergency medical services are not attended efficiently, if “consultation” model is followed.

While following the hybrid model, more patients were prescribed psychotropic medications and more psychological interventions were instituted compared to greater numbers of referrals to the psychiatric outpatient and de-addiction center in the routine consultation phase. Continued presence of the psychiatry resident in the emergency services facilitated the acute management of the patients in the emergency services itself. These finding further suggest that there is need to have a mental health professional in the emergency setting or to have a separate psychiatry emergency set-up to provide better mental health care to patients attending the emergency services.

It was also seen that the greater number of patients with medical problems were being referred for psychiatric assessment while following the hybrid model. Though there was no significant rise in the absolute number of patients without medical disorders being referred, there was a considerable increase in the absolute number of cases with medical disorders [an increase of about 14% as in Table 1]. This suggests that with close association with a member of CL psychiatry team, the medical colleagues felt more at ease in referring patients having psychiatric issues. The CL psychiatry team also felt easier to investigate patients and consult to other departments through the emergency services as has been reflected in the greater numbers of referrals and investigations. The presence of psychiatry resident thus seems beneficial to the patients on two counts. First, patients with medical illnesses with psychiatric issues are attended to promptly, and second, patients with psychiatric disorders receive consultations from other departments and are investigated more thoroughly. Similar observations on collaborative benefits have been made elsewhere.[24,25]

The implementation of hybrid liaison psychiatric services appears to be quite beneficial from the training point of view. Stationing a psychiatry resident allows him or her to observe closely various acute forms of psychiatric disorders, and allows him or her to manage them in the emergency service itself. It also gives an opportunity to closely discern the psychiatric manifestations of medical disorders. Diagnostic differentiation between medical and psychiatric disorders can be tricky at times, but rotation in the liaison service can help in better and more comprehensive understanding of the cases, as opinion of other specialists is immediately available. Such a rotation can also help in developing a rapport with the other medical specialists, which may help in de-stigmatizing psychiatry and psychiatric patients. In fact, European Association of CL psychiatry and psychosomatics have recommended clear guidelines for the inclusion of structured and supervised CL program for all trainee psychiatrists.[26]

The present observational study has some limitations that should be acknowledged. The data was extracted from the records maintained by the CL psychiatry services, and hence a limited degree of information could be accessed. Information like the specific medications used, severity of symptoms and investigation records were not available for analysis. Some of the diagnostic labels used (like intentional self-harm) do not represent psychiatric diagnoses nosologically. However, these were provisional diagnoses made in the emergency setting and were used when criteria of other diagnosis were not fulfilled. Furthermore, the present findings relate to adult emergency services of a tertiary care setting in India and may not be directly applicable to other settings such as primary care, pediatric emergency, or other adult in-patient services.

To conclude, this study suggests that implementation of a hybrid model of psychiatric services improves the referral rates from emergency medical set-up. Such a model allows for better collaboration between the psychiatrist and other specialists and thus benefits the patients. It also provides opportunities for comprehensive training of psychiatrists. Future studies should look at the other related issues like patient satisfaction, clinician's convenience and the cost benefits ratio with regard to the implementation of the hybrid model of CL psychiatry services. Different models of service delivery need to be evaluated for their feasibility and usefulness in CL psychiatry.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Ajiboye PO. Consultation-liaison psychiatry: The past and the present. Afr J Med Med Sci. 2007;36:201–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ene S. The role of consultation-liaison psychiatry in the general hospital. J Med Life. 2008;1:429–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grover S. State of Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry in India: Current status and vision for future. Indian J Psychiatry. 2011;53:202–13. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.86805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huyse FJ, van Tilburg W. Euthanasia policy in the Netherlands: The role of consultation-liaison psychiatrists. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1993;44:733–8. doi: 10.1176/ps.44.8.733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kisely S, Campbell LA. Taking consultation-liaison psychiatry into primary care. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2007;37:383–91. doi: 10.2190/PM.37.4.c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Knesper DJ. My favorite tips for engaging the difficult patient on consultation-liaison psychiatry services. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2007;30:245–52. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2007.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huyse FJ, Herzog T, Lobo A, Malt UF, Opmeer BC, Stein B, et al. Consultation-Liaison psychiatric service delivery: Results from a European study. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2001;23:124–32. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(01)00139-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Strain JJ. Liaison psychiatry. In: Rundell JR, Wise MG, editors. Textbook of Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1996. pp. 37–51. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Callaghan P, Eales S, Coates T, Bowers L. A review of research on the structure, process and outcome of liaison mental health services. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2003;10:155–65. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2850.2003.00300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gala C, Rigatelli M, De Bertolini C, Rupolo G, Gabrielli F, Grassi L. A multicenter investigation of consultation-liaison psychiatry in Italy. Italian C-L Group. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1999;21:310–7. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(99)00015-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kelkar DK, Chaturvedi SK, Malhotra S. A study of emergency psychiatric referrals in a teaching general hospital. Indian J Psychiatry. 1982;24:366–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adityanjee, Mohan D, Wig NN. Determinants of emergency room visits for psychological problems in a general hospital. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 1988;34:25–30. doi: 10.1177/002076408803400104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bhatia MS, Agrawal P, Khastbir U, Rai S, Bhatia A, Bohra N, et al. A study of emergency psychiatric referrals in a government hospital. Indian J Psychiatry. 1988;30:363–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Trivedi JK, Gupta AK. A study of patients attending emergency out-patient services of a large teaching institution. Indian J Psychiatry. 1982;24:360–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsai SJ, Lee YC, Chang K, Sim CB. Psychiatric emergency consultation in a general hospital. Changgeng Yi Xue Za Zhi. 1996;19:337–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khan AG, Ansari M, Hayder Z, Hussain M. Pattern of psychiatric emergencies at tertiary care hospital in Karachi. J Pak Psychiatr Soc. 2010;7:37–41. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Geneva: World Health Organization; 1993. World Health Organization. The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders: Diagnostic criteria for research. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kessler RC, Angermeyer M, Anthony JC, DE Graaf R, Demyttenaere K, Gasquet I, et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of mental disorders in the World Health Organization's World Mental Health Survey Initiative. World Psychiatry. 2007;6:168–76. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB, Hughes M, Eshleman S, et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States. Results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:8–19. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010008002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anderson RJ, Freedland KE, Clouse RE, Lustman PJ. The prevalence of comorbid depression in adults with diabetes: A meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:1069–78. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.6.1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fava GA, Porcelli P, Rafanelli C, Mangelli L, Grandi S. The spectrum of anxiety disorders in the medically ill. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71:910–4. doi: 10.4088/JCP.10m06000blu. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rackley S, Bostwick JM. Depression in medically ill patients. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2012;35:231–47. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2011.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sidana A, Sharma RP, Chavan BS, Arun P, Raj L. Psychiatric profile of patients attending General Emergency room services – A prospective study. J Ment Health Hum Behav. 2009;14:80–3. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vaz FJ, Salcedo MS. A model for evaluating the impact of consultation-liaison psychiatry activities on referral patterns. Psychosomatics. 1996;37:289–98. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3182(96)71568-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rothenhäusler HB, Ehrentraut S, Kapfhammer HP. Changes in patterns of psychiatric referral in a German general hospital: Results of a comparison of two 1-year surveys 8 years apart. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2001;23:205–14. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(01)00146-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Söllner W, Creed F. European Association of Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry and Psychosomatics Workgroup on Training in Consultation-Liaison. European guidelines for training in consultation-liaison psychiatry and psychosomatics: Report of the EACLPP Workgroup on Training in Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry and Psychosomatics. J Psychosom Res. 2007;62:501–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2006.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]