Abstract

Background

The feasibility and benefits of lifestyle intervention in CKD patients who are obese is not well studied. We examined the early effects of an exercise plus weight loss intervention on body composition, exercise capacity, metabolic parameters and kidney function in obese subjects with CKD.

Methods

Nine subjects (median age: 57 years, BMI: 43.9 kg/m2) underwent a lifestyle intervention program that included supervised aerobic exercise (i.e. ~ 85% HRmax) and dietary counseling (500 kcal reduction in daily caloric intake). Body composition (iDXA), exercise capacity (VO2max), quality of life, insulin resistance (Matsuda Index), inflammation (hs-C-Reactive Protein), adipokines (leptin and total adiponectin) and kidney function (iothalamate GFR) were measured at baseline and after 12-weeks of the intervention. Changes in parameters were compared using Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

Results

After 12 weeks of intervention, there was a significant decrease in BMI and fat mass (median: −4.9 kg [25th–75th percentile: −5.9, −3.0]). There was a significant increase in exercise capacity (3.7 ml/kg/min [3.0, 4.7]), along with improvements in insulin sensitivity (0.55 [0.43, 1.2]), total adiponectin (780.9 μg/ml [262.1, 1497.1]) and leptin (−5.1 ng/ml [−14.5, −3.3]). There were improvements in biomarkers of kidney disease and quality of life measures, but kidney function remained unchanged.

Conclusion

Lifestyle modification is feasible in obese patients with CKD and produces weight loss that is related to improvements in exercise capacity, insulin resistance, and adipokines. Whether lifestyle-induced weight loss and fitness can be sustained and whether it will mediate improvements in kidney function over time merits further investigation.

Keywords: kidney disease, exercise, physical capacity, weight loss

Background

Chronic Kidney disease (CKD) is estimated to affect approximately 13% of American adults (1) and individuals with CKD are at increased risk for cardiovascular disease (2). Higher cardiovascular disease burden can largely be attributed to increased insulin resistance and hypertension. In fact, a recent Finnish study of 543 adult men with stage 3–4 CKD demonstrated significant associations between both eGFR and hypertension with hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp derived insulin sensitivity (3). Data suggest that higher levels of insulin resistance are either independently associated with cardiovascular disease complications in CKD, or predict mortality in CKD when combined with unhealthy but modifiable lifestyles (4, 5). Reduced physical activity levels and exercise capacity in CKD also contribute to disease progression and cardiovascular disease mortality (6). Indeed, CKD patients usually manifest symptoms of exercise intolerance such as muscle weakness and fatigue and are less active, exhibiting muscle atrophy when compared to inactive normal subjects (7–9).

In general, weight loss through exercise and diet (i.e. lifestyle modification) reduces adiposity, systemic blood pressure, and blood glucose in obese adults by lowering inflammation and insulin resistance, and improving aerobic capacity (10). Interestingly, targeting obesity induced vascular dysfunction and glucose intolerance in patients with CKD may also prove effective for kidney function. Thus, utilizing exercise and diet as a first-line therapy for reducing renal dysfunction risk is reasonable. Despite the magnitude of obesity and CKD in the general population, there are relatively few studies that have examined the impact of diet and exercise programs in CKD population (11–13) (14, 15). Further, the reduced exercise tolerance previously observed in CKD populations raise concerns as to the feasibility of an exercise intervention program to promote clinically meaningful weight loss.

We hypothesized that lifestyle modification is feasible in obese individuals with CKD and will be associated with clinically meaningful weight loss. Moreover, we hypothesized that this weight loss would be related to improvements in exercise capacity (i.e. VO2max), body composition, insulin resistance, adipokine profiles (i.e. high adiponectin and low leptin), inflammation, and kidney function. Hence, we investigated the feasibility and effects of weight loss achieved during the first 12 weeks of a pilot lifestyle intervention in obese adults with CKD. In addition, we also studied the potential mechanisms related to obesity that might account for the beneficial effects of weight loss in CKD.

Methods

Subjects

Patients who had an eGFR <60 ml/min/1.73 m2, a BMI >30 kg/m2 and were being followed at Cleveland Clinic Renal Clinic (identified using electronic medical record) were considered for inclusion. Demographic characteristics (age, gender, and race), comorbidities (type 2 diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia etc.), and medication use were determined. Baseline comorbid conditions were identified using electronic medical record documentation (ICD-9 codes/medication). Subjects provided both verbal and written informed consent as approved by the Cleveland Clinic Foundation (CCF) Institutional Review Board. Participants came to the Clinical Research Unit for metabolic and body composition measures at baseline, and again after 3-months into the program.

Exercise Training

All exercise-training sessions were supervised by an exercise physiologist or research nurse, and were conducted in the Exercise Physiology Laboratory at the CCF Clinical Research Unit. The primary mode of exercise training was walking on a treadmill. Exercise was prescribed at 65–85% of heart rate max (HRmax) for 45–60 minutes/session, and subjects were expected to exercise once per day for 5 days/week for 12 weeks. Initially, exercise was prescribed for 30–40 min/day during weeks 1–4, 40–50 min/day during weeks 5–8, and then 50–60 min/day during weeks 9–12. A typical exercise session began with a 5–10 min warm-up, 10-min cycle ergometry, 30–40 min treadmill walk/jog with an appropriate grade, 10-min cycle ergometry, and a 5–10 min cool-down. Compliance with the training was carefully documented through regular attendance at the training sessions.

Diet Counseling

Participants were seen by a registered dietitian during their first visit. At baseline, a 3-day food diary was used to obtain details about participant’s dietary habits. Resting energy expenditure (REE) was determined using indirect calorimetry after an overnight fast (Vmax Encore, Viasys Sensormedics, Yorba Linda, CA), and this REE was multiplied by an activity factor of 1.2 to estimate total daily energy requirements. Subjects were individually counseled on how to reduce their daily caloric intake by 500 kcal (50–60% carbohydrate, 25–30% fat and 15%, i.e. 0.8–1.0 g/kg/day of protein) throughout the intervention. Compliance with the diet was monitored weekly during visits to the CRU for the exercise program.

Body Composition

Anthropometric measures (height, weight, and waist circumference) were measured by standard techniques, and BMI was calculated. Whole body fat mass (FM) and fat-free mass (FFM) was measured by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (model iDXA; GE Healthcare - Lunar, Madison, WI).

Insulin Resistance, Inflammation and Adipokine Measures

A 75 g oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) was performed after a 10–12 hour overnight fast. Anti-diabetic medication (e.g. insulin, metformin, etc.) was withheld 24 hour prior to testing to minimize effects on glucose metabolism. Fasting blood samples were drawn to determine initial glucose, insulin, leptin, and total/HMW adiponectin concentrations. Following these baseline draws, a 75 g glucose drink was ingested within a 10-minute period, and blood samples were collected at 30, 60, 90, 120 and 180 minutes after ingestion to determine postprandial plasma glucose and insulin. Plasma glucose was determined immediately on a YSI 2300 STAT Plus analyzer (Yellow Springs, OH). The remaining samples were stored at −80°C for subsequent analysis. Plasma insulin was determined via radioimmunoassay (Millipore, Billerica, MA). Insulin resistance was determined from the homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) and the Matsuda Index(16). Fasting high sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP), plasma leptin, and total and high molecular weight (HMW) adiponectin was analyzed via ELISA (Millipore, Billerica, MA). All blood samples were measured in duplicate, and each participant’s pre- and post-intervention samples were batch-analyzed to minimize intra-subject variability.

Kidney Function Measures

Details of 125I-sodium iothalamate GFR determination at the Cleveland Clinic have been previously described (17). Briefly, patients received a water load before the test. 125I-sodium iothalamate (25 μCu; Glofil; Questor Pharmaceuticals, Union City, CA) was injected subcutaneously without epinephrine. Baseline urine and blood samples were obtained. A voluntary-voided urine sample was discarded, followed by one timed clearance urine collection. Blood samples were drawn before and after each urine collection. Isotope activity was determined by gamma counting of 0.5 ml of plasma or urine on a Packard Minaxi 5000 series counter (Perkin Elmer Life Sciences, Downers Grove, IL). The counts in each period were the average of the samples for each clearance period. The mean iothalamate GFR (iGFR) was calculated with and without standardizing to body surface area (BSA, 1.73 m2) using the Dubois and Dubois formula.

Cystatin C and β-2-Microglobulin

From fasting blood collections, Cystatin C and β-2-microbolulin were analyzed as potentially novel biomarkers for renal function. Plasma Cystatin C was measured using a particle enhanced immunoturbidimetric assay (18). β-2-microglobulin was measured using an immunoturbidimetric assay (Roche). Both assays were run on the Roche Cobas c311 analyzer, a high throughput chemistry analyzer. 24-hour creatinine clearance and proteinuria measurements were performed using standard methods at our institution.

Measurement of Exercise Tolerance and Quality of Life

Maximal oxygen consumption (VO2max) during an incremental treadmill test was used as the criterion to measure physical fitness. Three of the 4 following criteria were required to consider the test maximum: plateau in VO2, (< 150 ml/min), heart rate within 15 bpm of age-predicted HRmax, volitional fatigue, and/or a respiratory exchange ratio >1.0. Measurements of VO2max were made at 4-week intervals to adjust exercise training intensity accordingly. Kidney Disease and Quality Of Life (KDOQL-36) was administered before and after the 12 week intervention.

Statistical Analysis

We described patient characteristics and medication intake as N (%), and summarized continuous variables with medians and interquartile ranges. The change in values (exercise capacity, kidney function measures, adipokines, insulin resistance and weight loss) from baseline to 12 weeks after the program was evaluated using the Wilcoxon signed rank test. Spearman correlations were used to determine associations between the change in iGFR (adjusted and unadjusted) and the changes in metabolic markers (e.g. leptin, adiponectin and insulin resistance). Significance was accepted at p<0.05. Data analyses were conducted using Unix SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC), and graphs were created using R 3.0.1 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Subject Characteristics

Fifteen participants consented and underwent a screening treadmill exercise stress test. Twelve participants who had a negative test were enrolled, and nine completed the 12 week intervention (one moved out of town, one developed transient atrial fibrillation that resolved and another with pre-existing back pain worsened leading to withdrawal from the program). Table 1 outlines the baseline characteristics of the study population (n=9). In brief, median age was 57 years (IQR 51, 63) with 77% being female and 33% Whites. All included patients had hypertension and hyperlipidemia. The median BMI was 43.9 kg/m2 (IQR 40.6, 47.4) with median fat mass of 56.3 kg (IQR 48.6, 64.4). At baseline, median unadjusted iGFR and adjusted iGFR were 78.7 ml/min (IQR 76.0, 91.0) and 62 ml/min/1.73m2 (IQR 59.0, 68.0), respectively, along with an eGFR of 41.0 ml/min/1.73 m2 (IQR 33.0, 47.0). Participant compliance was 84%.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of study participants with CKD

| Variable | N or % or Median [IQR] (N=9) |

|---|---|

| Age, Median (Q1, Q3) | 57.0[51.0,63.0] |

| Male Gender | 2 |

| White race | 3 |

| Type 2 diabetes | 84.6% |

| Hypertension | 100% |

| Hyperlipidemia | 100% |

| Number of antihypertensive | 3 (2, 4) |

| Medications | |

| Insulin use | 2 |

| ACEI or ARB use | 7 |

Data are presented as median (IQR) or n; ACEI/ARB- Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers

Body Composition, Insulin Resistance, Inflammation and Adipokines

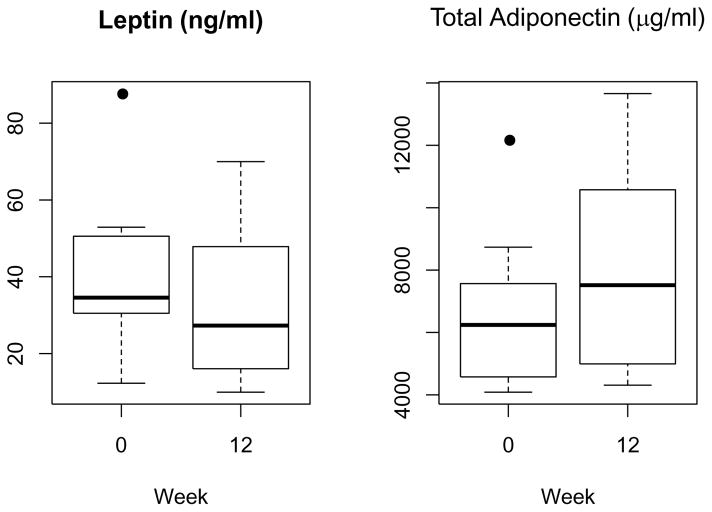

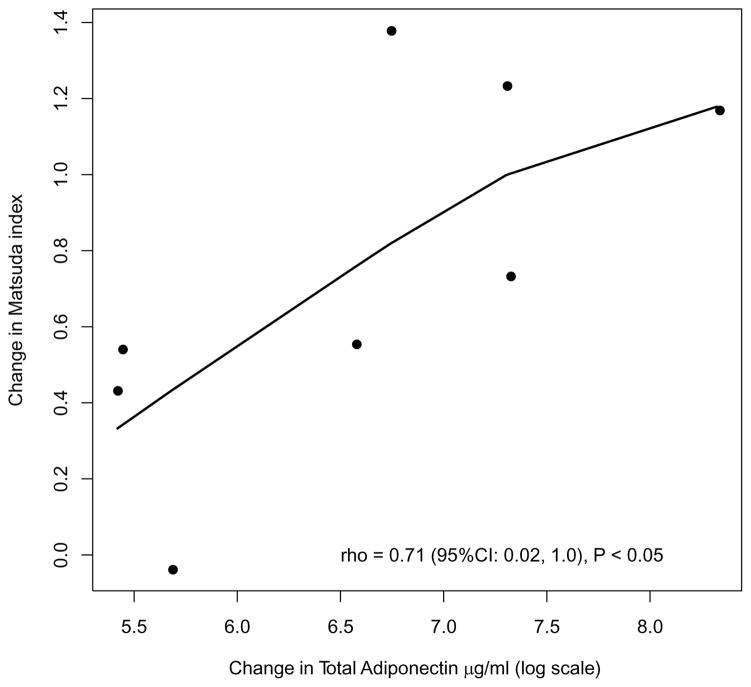

BMI, WC, and fat mass decreased significantly at 12 weeks (Table 2). The lifestyle modification program significantly reduced fasting glucose (p=0.04) and insulin levels (p=0.02), and improved insulin sensitivity as assessed by the Matsuda Index (Table 2). Total adiponectin levels increased (change: 780.9 μg/ml [262.1, 1497.1]) along with a significant decrease in plasma leptin (change: −5.1 ng/ml [−14.5, −3.3]) at 12 weeks (Figure 1). Change in total adiponectin correlated with change in insulin resistance (Figure 2).

Table 2.

Changes in adiposity parameters, lipid parameters, insulin resistance, adipokines and inflammatory markers before and 3 months after starting the intervention

| Variable | Baseline Median[IQR] | 3 month Median[IQR] | Change in variable Median[IQR] | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adiposity parameters* | ||||

| Weight (kg) | 113.8 [105.7, 138.7] | 111.3 [101.6, 133.0] | −5.1 [−6.5, −4.1] | 0.004 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 43.9 [40.6, 47.4] | 41.0 [39.0, 45.5] | −1.9 [−2.6, −1.4] | 0.004 |

| Waist Circumference (cm) | 128.0 [122.0, 133.5] | 119.0 [113.0, 130.8] | −3.0 [−8.3, −2.3] | 0.008 |

| Fat% | 50.0 [48.0, 53.7] | 47.0 [45.2, 51.7] | −1.8 [−2.6, −1.6] | 0004 |

| Fat mass (kg) | 56.3 [48.6, 64.4] | 50.1 [42.8, 66.7] | −4.9 [−5.9, −3.0] | 0.04 |

| Fat free mass (kg) | 57.5 [56.2, 64.2] | 58.5 [54.3, 65.4] | 0.00 [−1.8, 1.6] | 0.9 |

| Hemodynamics | ||||

| SBP (mm Hg) | 141.0[127.0,144.0] | 139.8[133.5,148.0] | −0.50[−7.5,14.0] | 0.99 |

| DBP (mm Hg) | 83.5[72.5,89.5] | 71.5[70.0,78.0] | −8.0[−13.5, −0.50] | 0.04 |

| Heart rate | 76.0[66.0,81.0] | 65.0[61.0,69.0] | −11.0[−13.0, −5.0] | 0.008 |

| Lipid parameters | ||||

| Total cholesterol (mg/dl) | 164.0 [135.0, 185.0] | 149.0 [130.0, 196.0] | 10.0 [4.0, 13.0] | 0.31 |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dl) | 43.0 [38.0, 48.0] | 42.0 [33.0, 58.0] | 3.0 [2.0, 3.0] | 0.12 |

| Serum triglycerides (mg/dl) | 91.0 [86.0, 122.0] | 96.0 [89.0, 105.0] | 3.0 [−24.0, 8.0] | 0.68 |

| LDL Cholesterol (mg/dl) | 106.0 [62.8, 124.8] | 80.8 [62.0, 133.2] | 7.4 [−0.80, 9.4] | 0.20 |

| Insulin Resistance & Inflammation | ||||

| Log CRP (mg/L) | 0.71 [0.60, 0.98] | 0.79 [0.68, 1.00] | 0.01 [−0.04, 0.14] | 0.46 |

| HOMA-IR | 9.3 [3.6, 9.3] | 5.3 [3.5, 9.1] | −0.82 [−4.0, 0.36] | 0.36 |

| Matsuda index | 1.4 [1.07, 2.2] | 2.2 [1.2, 3.4] | 0.55 [0.43, 1.2] | 0.02 |

| VO2max (ml/kg/min) | 18.8 [15.1, 23.3] | 21.5 [20.6, 27.3] | 3.7 [3.0, 4.7] | 0.004 |

Data are presented as median (IQR). Change in variable = After – Before intervention. BMI = body mass index; SBP = Systolic blood pressure; DBP = Diastolic blood pressure; VO2max = maximal oxygen consumption; LDL = low-density lipoprotein; HDL = high-density lipoprotein;

Figure 1.

Changes in leptin and total adiponectin during the study period (Median and interquartile range at baseline and 12 weeks after intervention)

Figure 2.

Correlation between changes in total adiponectin and the Matsuda index

Exercise Capacity

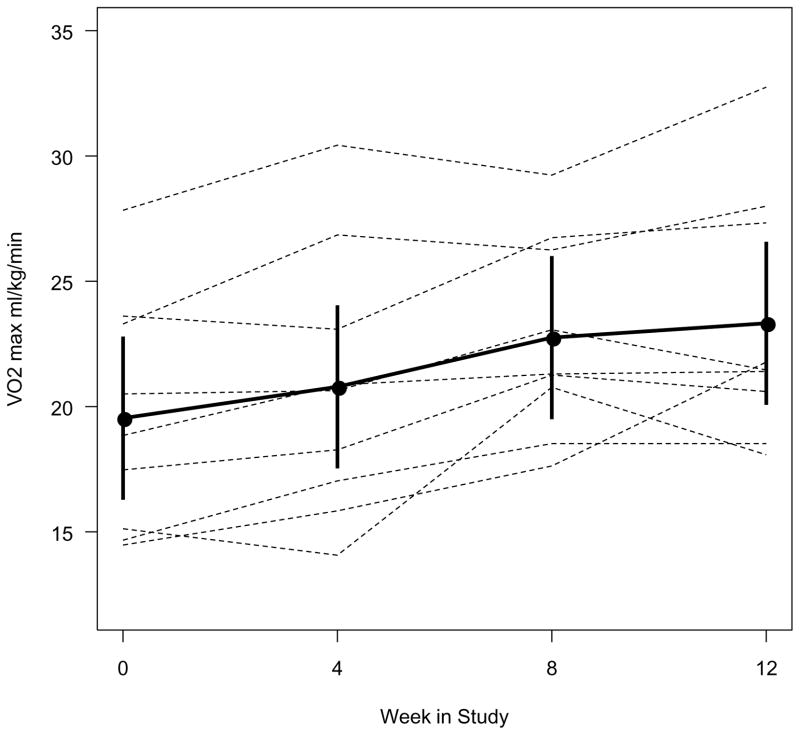

Improvement in exercise capacity was observed as early as 4 weeks into the program, and this improvement continued through 8 and 12 week time points (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Change in VO2max during the study period

Renal Function

Kidney function measures did not change significantly after 12 weeks of lifestyle modification (Table 3).

Table 3.

Changes in kidney function parameters

| Kidney function measures | Baseline | 3 month follow | Change | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serum creatinine (mg/dl) | 1.2 [1.2, 1.7] | 1.2 [1.2, 1.4] | −0.01 [−0.12, 0.10] | 0.76 |

| Cystatin C (mg/dl) | 1.4 [1.4, 1.9] | 1.5 [1.4, 1.9] | 0.04 [0.01, 0.12] | 0.10 |

| β-2 microglobulin (mg/dl) | 2.7 [2.4, 3.4] | 2.8 [2.5, 3.7] | 0.10 [0.00, 0.30] | 0.34 |

| eGFRcr (ml/min) | 55.2 [44.5, 58.8] | 55.8 [48.2, 60.1] | 0.58 [−5.7, 4.1] | 0.82 |

| eGFRcr (ml/min/1.73m2) | 41.9 [33.3, 47.5] | 43.0 [38.6, 48.8] | 1.7 [−3.5, 3.6] | 0.57 |

| iGFR (ml/min) | 78.7[72.0,82.9] | 79.9 [70.1, 85.7] | −2.8[−4.2,7.9] | 0.99 |

| iGFR (ml/min/1.73m2) | 59.0[55.0,62.0] | 58.0 [54.0, 69.0] | −1.00[−2.0,8.0] | 0.73 |

| 24 hr creatinine clearance (ml/min) | 71.2 [51.5, 78.1] | 58.3 [45.6, 67.2] | −7.8 [−23.8, 5.0] | 0.16 |

| 24 hr Proteinuria (g) | 0.16 [0.16, 0.16] | 0.16 [0.16, 0.17] | 0.00 [0.00, 0.01] | 0.81 |

Data are presented as median (IQR). Change in variable = After – Before intervention.

Quality of Life

After 12 weeks of intervention, there were significant changes in mental composite scores (median change 2.6 [0.49, 11.1], p=0.04) and there was a trend towards a decrease in kidney disease (median change 7.8 [0.00, 16.3], p=0.05), while there were no significant changes in the physical composite, burden of kidney disease, or symptoms.

Discussion

In this short-term prospective study, lifestyle intervention was effective in achieving weight loss, and improving body composition, physical fitness, insulin sensitivity, blood pressure, and adipokine profiles in obese subjects with CKD. Even though this was a select group of participants, compliance was higher and improvements noted are similar to what has been reported in the non-CKD population. In particular, the improvement in VO2max was encouraging since 4 of our 9 patients were below 17.5 mL/kg/min at baseline, where the 3-year risk for mortality due to cardiovascular disease is elevated (19). By week 8, all participants had achieved a VO2max above this cutoff. This is significant given evidence of reduced exercise capacity in the CKD population, and overall cardiovascular disease risk reduction. Until the recent publications detailing positive benefits to CKD patients by exercise interventions, there has been a common perception that relatively vigorous exercise could not be tolerated by these patients. In contrast to other studies that examined less strenuous exercise interventions (14, 15, 20), our data suggest that this is not the case. Indeed, these individuals with CKD were quite capable of achieving exercise levels equivalent to 60 minutes per day, five days per week, at ~80% of HRmax.

Our data demonstrate that improvements in metabolic health in CKD are achievable through diet and exercise interventions. As shown in obese insulin resistant non-diabetic and type 2 diabetics without CKD (21, 22), we demonstrated here that an exercise and diet intervention inducing approximately 6% fat loss effectively reduces insulin resistance in individuals with CKD. While stable isotope technology or use of aterio-venous sampling would be needed to determine the exact role of skeletal muscle and hepatic glucose production as a mechanism for improved glucose regulation in this study, we did observe significant improvements in both fasting and post-prandial glucose concentrations. This suggests that hepatic glucose production and skeletal muscle insulin sensitivity may have been improved. Indeed, insulin sensitivity estimated by the Matsuda index, which is strongly linked to skeletal muscle glucose disposal, and HOMA-IR, a fasting measure of insulin resistance reflecting hepatic glucose output, showed significant improvements in our study population (16). In addition, we observed significant correlations between insulin sensitivity and adiponectin, suggesting that increased adiponectin may be an important mechanism that confers protection against obesity related inflammation and insulin resistance. Interestingly, the observed improvement in adiponectin reported herein is consistent with prior work by our group, suggesting that adiponectin is an important endocrine factor related to exercise and weight loss improvements in glucose regulation (23). Taken together, since reduced multi-organ insulin sensitivity is a key risk factor for future cardiovascular in people with and without CKD, it seems reasonable to infer that systemic improvements in insulin action are likely to result in lower cardiovascular disease risk and reduction in future mortality (4).

Another crucial aspect of the improvement in insulin resistance in this population is the reduction in circulating insulin. Hyperinsulinemia in obesity is associated with alterations in glomerular hemodynamics and can also cause cell proliferation and renal injury by promoting the expression of growth factors such as transforming growth factor (TGF) β and the downregulation of matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-2, an enzyme responsible for matrix degradation (24, 25). TGFβ has been shown to promote renal fibrosis, while hyperinsulinemia can increase TGFβ expression in proximal tubular cells, which may be related to extracellular matrix proliferation, characteristic of diabetic nephropathy (26). Our observations of reductions in fasting and post-prandial insulin concentrations suggest that improvements in insulin sensitivity are an important etiological factor in the development of CKD related hypertension and heart disease. In fact, we noted improvements in DBP and resting heart rate, which are known cardiovascular risk factors. Further studies are needed to understand how insulin contributes to the development of renal injury related to hypertension.

Although our intervention did not generate measurable improvements in biomarkers of kidney function, this was not entirely unexpected. We recently demonstrated that bariatric surgery, which produced rapid and robust improvements in insulin sensitivity, did not produce improvements in kidney function until 1 year post surgery (27). These data indicate that while kidney function restoration is possible, it may require sustained long-term improvements in metabolic health to see measurable effects on kidney function. In fact, when taken together with our prior work (15), reductions in body fat do not appear to be the primary determinant for improving kidney function. Nevertheless, we acknowledge that there is no consensus currently about the utility of various biomarkers to assess changes in kidney function following clinically meaningful weight loss. Thus, our data highlight the need for additional studies to identify the optimal lifestyle approach for managing kidney function, and the need for larger studies with long-term follow-up to evaluate efficacy and durability of such an approach (28).

Our study has some limitations that may affect our interpretation of results. We acknowledge that our sample size is modest. However, our study is unique in that these subjects were able to complete an intense aerobic exercise program (5 days/week) while most published studies in this population either had twice or thrice a week supervised intervention (14, 20). In addition, the reasons the 3 participants dropped out were unrelated to the intervention per se. Otherwise, adherence rates were comparable to the wider population. Perhaps more importantly for this subject population is the observation that non-dialysis dependent CKD patients have poor quality of life including fatigue, inadequate sleep and depression (29). In our study, we noted improvements in several quality of life parameters (effects of kidney disease and SF 36 mental composite), which suggests the potential psychological beneficial effects of lifestyle interventions in CKD. Next, our study may be subject to selection bias as patients who perceived themselves below the minimal level of physically fitness for participation, or lacked motivation to travel 5 days/week are likely to have opted to not join the study. Further, we lacked a control group to assess the differences in those who didn’t receive the intervention, although others have shown that physical inactivity over the short-term (30) or of similar duration to the current study (31) reported a worsening of insulin resistance and cardiometabolic health. In either case, this might be important for outcomes such as quality of life as we report improvements with lifestyle intervention.

In conclusion, current clinical guidelines for those with kidney disease recommend exercising 5 days per week for at least 30 minutes (32). Our data highlights the feasibility of these recommendations for severely obese patients with CKD and suggest that these individuals can successfully perform this moderate to high intensity exercise prescription. Moreover, this type of exercise and diet intervention offers beneficial effects in terms of exercise capacity, insulin resistance and adipokines. However, whether these benefits and this type of lifestyle modification program is sustainable, and leads to better kidney function and reduction in cardiovascular disease risk should be the focus of larger studies in the future.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the research volunteers for their outstanding dedication and effort, and the nursing staff of the Clinical Research Unit at Cleveland Clinic, and the staff who helped with the implementation of the study and data collection. This work was performed while Drs. Navaneethan and Malin were at the Cleveland Clinic.

Funding: SDN was supported by a career development award from the National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health (Grant #TR000440). SKM was supported by an NIH training grant T32 DK007319 to JPK. This work was “Supported in part by UL1TR000439, National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) of the National Institutes of Health.”

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors have no relevant financial interest in the study.

Previous presentations: The results of this study were presented as an abstract at the Annual American Society of Nephrology meeting held in Philadelphia, PA – November 2014.

The contents of this manuscript are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

References

- 1.Coresh J, Selvin E, Stevens LA, Manzi J, Kusek JW, Eggers P, et al. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in the United States. JAMA. 2007 Nov 7;298(17):2038–47. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.17.2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Go AS, Chertow GM, Fan D, McCulloch CE, Hsu CY. Chronic kidney disease and the risks of death, cardiovascular events, and hospitalization. N Engl J Med. 2004 Sep 23;351(13):1296–305. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xu H, Huang X, Arnlov J, Cederholm T, Stenvinkel P, Lindholm B, et al. Clinical correlates of insulin sensitivity and its association with mortality among men with CKD stages 3 and 4. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014 Apr;9(4):690–7. doi: 10.2215/CJN.05230513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Becker B, Kronenberg F, Kielstein JT, Haller H, Morath C, Ritz E, et al. Renal insulin resistance syndrome, adiponectin and cardiovascular events in patients with kidney disease: the mild and moderate kidney disease study. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005 Apr;16(4):1091–8. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004090742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Navaneethan SD, Schold JD, Kirwan JP, Arrigain S, Jolly SE, Poggio ED, et al. Metabolic syndrome, ESRD, and death in CKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013 Jun;8(6):945–52. doi: 10.2215/CJN.09870912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Navaneethan SD, Kirwan JP, Arrigain S, Schreiber MJ, Sehgal AR, Schold JD. Overweight, obesity and intentional weight loss in chronic kidney disease: NHANES 1999–2006. Int J Obes (Lond) 2012 Dec;36(12):1585–90. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2012.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kosmadakis GC, Bevington A, Smith AC, Clapp EL, Viana JL, Bishop NC, et al. Physical exercise in patients with severe kidney disease. Nephron Clin Pract. 2010;115(1):c7–c16. doi: 10.1159/000286344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roshanravan B, Patel KV, Robinson-Cohen C, de Boer IH, O’Hare AM, Ferrucci L, et al. Creatinine Clearance, Walking Speed, and Muscle Atrophy: A Cohort Study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2014 Dec 23; doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang XH, Mitch WE. Mechanisms of muscle wasting in chronic kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2014 Sep;10(9):504–16. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2014.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Look AHEAD Research Group. Wing RR. Long-term effects of a lifestyle intervention on weight and cardiovascular risk factors in individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus: four-year results of the Look AHEAD trial. Arch Intern Med. 2010 Sep 27;170(17):1566–75. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Navaneethan SD, Yehnert H, Moustarah F, Schreiber MJ, Schauer PR, Beddhu S. Weight loss interventions in chronic kidney disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009 Oct;4(10):1565–74. doi: 10.2215/CJN.02250409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Afshinnia F, Wilt TJ, Duval S, Esmaeili A, Ibrahim HN. Weight loss and proteinuria: systematic review of clinical trials and comparative cohorts. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010 Apr;25(4):1173–83. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfp640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Ogden CL. Prevalence of obesity and trends in the distribution of body mass index among US adults, 1999–2010. JAMA. 2012 Feb 1;307(5):491–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Greenwood SA, Koufaki P, Mercer TH, MacLaughlin HL, Rush R, Lindup H, et al. Effect of Exercise Training on Estimated GFR, Vascular Health, and Cardiorespiratory Fitness in Patients With CKD: A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. Am J Kidney Dis. 2014 Sep 15; doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Headley S, Germain M, Wood R, Joubert J, Milch C, Evans E, et al. Short-term aerobic exercise and vascular function in CKD stage 3: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Kidney Dis. 2014 Aug;64(2):222–9. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matsuda M, DeFronzo RA. Insulin sensitivity indices obtained from oral glucose tolerance testing: comparison with the euglycemic insulin clamp. Diabetes Care. 1999 Sep;22(9):1462–70. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.9.1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Poggio ED, Rule AD, Tanchanco R, Arrigain S, Butler RS, Srinivas T, et al. Demographic and clinical characteristics associated with glomerular filtration rates in living kidney donors. Kidney Int. 2009 May;75(10):1079–87. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hansson LO, Grubb A, Liden A, Flodin M, Berggren A, Delanghe J, et al. Performance evaluation of a turbidimetric cystatin C assay on different high-throughput platforms. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 2010 Sep;70(5):347–53. doi: 10.3109/00365513.2010.491124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sietsema KE, Amato A, Adler SG, Brass EP. Exercise capacity as a predictor of survival among ambulatory patients with end-stage renal disease. Kidney Int. 2004 Feb;65(2):719–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00411.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rossi AP, Burris DD, Lucas FL, Crocker GA, Wasserman JC. Effects of a renal rehabilitation exercise program in patients with CKD: a randomized, controlled trial. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014 Dec 5;9(12):2052–8. doi: 10.2215/CJN.11791113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Solomon TP, Haus JM, Kelly KR, Cook MD, Filion J, Rocco M, et al. A low-glycemic index diet combined with exercise reduces insulin resistance, postprandial hyperinsulinemia, and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide responses in obese, prediabetic humans. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010 Dec;92(6):1359–68. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2010.29771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Malin SK, Kirwan JP. Fasting hyperglycaemia blunts the reversal of impaired glucose tolerance after exercise training in obese older adults. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2012 Sep;14(9):835–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2012.01608.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kelly KR, Navaneethan SD, Solomon TP, Haus JM, Cook M, Barkoukis H, et al. Lifestyle-induced decrease in fat mass improves adiponectin secretion in obese adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2014;46(5):920–6. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000000200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hall JE, Brands MW, Dixon WN, Smith MJ., Jr Obesity-induced hypertension. Renal function and systemic hemodynamics. Hypertension. 1993 Sep;22(3):292–9. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.22.3.292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lupia E, Elliot SJ, Lenz O, Zheng F, Hattori M, Striker GE, et al. IGF-1 decreases collagen degradation in diabetic NOD mesangial cells: implications for diabetic nephropathy. Diabetes. 1999 Aug;48(8):1638–44. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.48.8.1638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sharma K, Ziyadeh FN. Hyperglycemia and diabetic kidney disease. The case for transforming growth factor-beta as a key mediator. Diabetes. 1995 Oct;44(10):1139–46. doi: 10.2337/diab.44.10.1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Navaneethan SD, Malin SK, Arrigain S, Kashyap SR, Kirwan JP, Schauer PR. Bariatric Surgery, Kidney Function, Insulin Resistance, and Adipokines in Patients With Decreased GFR: A Cohort Study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015 Feb;65(2):345–7. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jesudason DR, Clifton P. Interpreting different measures of glomerular filtration rate in obesity and weight loss: pitfalls for the clinician. Int J Obes (Lond) 2012 Nov;36(11):1421–7. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2011.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Porter A, Fischer MJ, Wang X, Brooks D, Bruce M, Charleston J, et al. Quality of life and outcomes in African Americans with CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014 Aug;25(8):1849–55. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013080835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reynolds LJ, Credeur DP, Holwerda SW, Leidy HJ, Fadel PJ, Thyfault JP. Acute Inactivity Impairs Glycemic Control but Not Blood Flow to Glucose Ingestion. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2014 Sep 9; doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000000508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Malin SK, Gerber R, Chipkin SR, Braun B. Independent and combined effects of exercise training and metformin on insulin sensitivity in individuals with prediabetes. Diabetes Care. 2012 Jan;35(1):131–6. doi: 10.2337/dc11-0925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Inker LA, Astor BC, Fox CH, Isakova T, Lash JP, Peralta CA, et al. KDOQI US commentary on the 2012 KDIGO clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2014 May;63(5):713–35. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.01.416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]