Abstract

Objective:

The National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) recommends a comprehensive treatment program for individuals with substance use disorder (SUD) in order to treat needs they often have in addition to their SUD. Specifically, NIDA suggests providing services related to the following issues: medical care, mental health care, HIV/AIDS, child care, educational, vocational, family counseling, housing, transportation, financial, and legal. By providing a comprehensive model that combines core and wraparound services, treatment centers can deliver a higher quality of treatment. In this article, we assessed the relationship between client characteristics and the availability of wraparound services in SUD treatment centers.

Method:

We combined two nationally representative samples of treatment centers and used a negative binomial regression and a series of logistic regressions to analyze the relationship between client characteristics and wraparound services.

Results:

On average, centers offered fewer than half of the wraparound services endorsed by NIDA. Our results indicated that client characteristics were significantly related to the provision of wraparound services. Most notably, the proportion of adolescent clients was positively related to educational services, the proportion of female clients was positively related to child care, but the proportion of clients referred from the criminal justice system was negatively associated with the provision of multiple wraparound services.

Conclusions:

Our findings have important implications for SUD clients and suggest that, although centers are somewhat responsive to their clients’ ancillary needs, most centers do not offer the majority of wraparound services.

The national institute on drug abuse (nida) emphasizes that “the best treatment programs provide a combination of therapies and other services to meet the needs of the individual patient” (NIDA, 2012, p. 8). Although core services directly related to diagnosis and treatment of substance use disorders (SUDs) are undoubtedly important, wraparound services, which address clients’ co-occurring problems, are important components that constitute a comprehensive model of treatment (NIDA, 2012). Wraparound services include those addressing clients’ medical care, mental health, HIV, child care, family, educational, vocational, housing/transportation, finances, and legal issues. Individuals with SUDs often experience other problems that affect their life circumstances, and effective treatment programs should seek to end substance use as well as provide services that help individuals with other needs.

Research over the past 20 years has demonstrated that providing wraparound services enhances treatment retention and improves treatment outcomes (Knight et al., 2010; Marsh et al., 2000, 2004, 2011; McLellan et al., 1998). Despite these findings, client-level data suggest that many client needs are unmet (Apantaku-Olajide et al., 2012; Machlan et al., 2005; Pringle et al., 2006). To date, there has been less organizational-level research on how client characteristics are associated with the provision of wraparound services in SUD treatment programs across the United States. With few exceptions (Ducharme et al., 2007; Oser et al., 2009), the majority of research on wraparound services focuses on individual-level outcomes for individuals in treatment. Furthermore, few studies are nationally representative and can speak to larger patterns across the nation. This article addresses these gaps, focusing on the relationship between treatment centers’ client characteristics and their offering of wraparound services in a nationally representative sample of SUD treatment centers.

Client characteristics

We focused on several key client characteristics in this study: women, adolescents, trauma survivors, unemployed, and those referred by the criminal justice system. We highlighted these five client characteristics because research indicates that these client groups have specific needs for wraparound services in SUD treatment. It is important to note that, although the client characteristics are described below as separate categories, they are often overlapping.

Women.

SUD treatment needs differ for women and men (Ashley et al., 2003; Pelissier & Jones, 2005; Tang et al., 2012). Women often turn to substance use as a result of life circumstances, such as domestic violence, illness, accidents, and/or a change to their family life (Greenfield et al., 2007, 2010; Nelson-Zlupko et al., 1995), and thus may need specialized services and additional components of care (Greenfield et al., 2007; Marsh et al., 2000; Tang et al., 2012). Further, women are more likely to remain in treatment if the treatment provider helps in accessing dependable child care (Campbell et al., 2009; Greenfield et al., 2007; Marsh et al., 2004; Nelson-Zlupko et al., 1995), healthcare (Marsh et al., 2004; Nelson-Zlupko et al., 1995), and transportation (Marsh et al., 2004; Nelson-Zlupko et al., 1995). Aid in accessing legal assistance may also encourage entry to treatment for women with children, as the fear of losing custody of their children can be a significant treatment barrier (Greenfield et al., 2007).

Women are also more likely than men to have co-occurring psychosocial needs (Ashley et al., 2003; Marsh et al., 2011) and housing needs, partly because of the physical abuse histories and estrangement from spouses/partners that accompany their substance use (Gonzalez-Guarda et al., 2008; Royse et al., 2000). Treatment centers can resolve many of these dilemmas by offering access to services, such as child care, mental health, and legal services.

Adolescents.

Only about 10% of adolescents who need SUD treatment receive treatment (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA], 2013), partly because of adolescents’ lack of motivation or recognition of SUD and the limited availability of adolescent treatment programs (Battjes et al., 2003; Mensinger et al., 2006). Compared with adult SUD clients, adolescents are more likely to be diagnosed with co-occurring mental health problems and thus may require additional mental health services (Chan et al., 2008; Esposito-Smythers et al., 2012). Adolescents who use substances are also less likely to attend school (Engberg & Morral, 2006) and more likely to drop out of school (DuPont et al., 2013) than adolescents who do not use substances. Further, adolescents who drop out of school are also more likely to turn to alcohol and other drugs (DuPont et al., 2013).

These problems are reversible, however, as research shows that cessation of substance use is related to an increase in academic achievement (DuPont et al., 2013). Thus, providing educational services to adolescents seeking SUD treatment can be a substantial ingredient of a successful treatment experience. Finally, a large percentage of adolescent SUD clients enter treatment through the criminal justice system (Yeterian et al., 2013), so the provision of legal services is particularly beneficial for them.

Trauma survivors.

SUD clients who are trauma survivors are an especially vulnerable population. Treatment dropout rates tend to be higher for trauma survivors (Odenwald & Semrau, 2013), specifically for individuals with a history of physical or sexual abuse (Claus & Kindleberger, 2002; Kang et al., 2002), compared with clients who have not experienced traumatic events. Nonetheless, interventions that specifically address trauma are associated with increased treatment retention (Amaro et al., 2007; Ouimette et al., 2003). A comprehensive treatment approach that incorporates mental health services, child care, and other services is particularly recommended for trauma survivors (Amaro et al., 2007). In addition to mental health services and child care, trauma survivors may be in particular need of housing assistance and financial counseling to separate themselves from an abusive environment.

Unemployed.

Another important characteristic that could affect the provision of wraparound services is the proportion of unemployed clients. Extensive research indicates that unemployment rates tend to be much higher for SUD treatment clients than for the general population (Friedman et al., 1996; Lamb et al., 1996; Magura et al., 2004; SAMHSA, 2013). Many studies have found that the employment of SUD clients is linked to lower relapse rates and longer treatment retention (Henkel, 2011; Kidorf et al., 2004; Platt, 1995; Room, 1998), whereas unemployment is associated with more frequent and heavier substance use (Henkel, 2011; Widman et al., 2000). Unemployed SUD clients often report an interest in getting a job, yet many do not participate in vocational programs (Lidz et al., 2004; Magura, 2003, 2004). Educational services, vocational services in the form of job-seeking skills and placement services, and housing assistance may be essential for the achievement of long-term stability among unemployed clients. Therefore, treatment centers with a preponderance of unemployed clients may find that offering these services significantly enhances overall treatment outcomes.

Criminal justice system referrals.

Clients who are referred through the criminal justice system are likely to have a variety of needs beyond their substance use. The legal repercussions of their substance use could include criminal charges, financial problems, employment and housing needs, and family problems. According to the 2014 Arrestee Drug Abuse Monitoring II (ADAM II) survey, which examined arrests in five major U.S. cities, more than half of adult males arrested tested positive for at least one illegal drug (Office of National Drug Control Policy, 2014). NIDA’s report on SUD treatment for criminal justice populations emphasizes the need for social support and other wraparound services based on clients’ criminal history (NIDA, 2006).

Nonetheless, programs with a greater reliance on criminal justice-affiliated clients are less likely than other programs to offer core services (Edwards et al., 2011), particularly pharmacotherapy (Aletraris et al., 2015; Knudsen & Roman, 2012; Kubiak et al., 2009; Rich et al., 2005; Smith-Rohrberg et al., 2004). Because of the criminal justice system’s limited reimbursement policies, programs with a greater proportion of criminal justice clients might be less likely to offer wraparound services. Indeed, research suggests that correctional-based programs offer a more limited range of wraparound services compared with community-based programs (Grella et al., 2007).

Based on this review, we addressed two research questions to help us understand national trends of wraparound services in U.S. treatment centers: First, how are client characteristics related to the number of wraparound services offered by SUD treatment centers? Second, how are client characteristics related to individual wraparound services in SUD treatment centers?

Method

Sample and procedures

This research drew on data from two U.S. samples in the National Treatment Center Study, a family of ongoing, national studies on SUD treatment, with the treatment center as the unit of analysis (Aletraris et al., 2014; Aletraris & Roman 2015). The first sample was a nationally representative sample of treatment centers. The second sample was a nationally representative sample of privately funded treatment centers. The data used for analyses were a combination of these two samples. Each sample was created using the SAMHSA Substance Abuse Treatment Services Locator to randomly sample treatment organizations across the United States and was stratified by the population size of the county. Centers were required to be open to the public and to offer at least one level of care between ASAM Level I (structured outpatient treatment) and Level III (residential/inpatient treatment) services (Mee-Lee et al., 2001).

Treatment centers in the first sample had at least 25% of their caseload primarily dependent on alcohol. Face-to-face interviews were completed between June 2009 and January 2012 with administrators and clinical directors in 307 centers, representing a response rate of 68% of eligible centers contacted.

In the privately funded sample, centers met eligibility requirements if they received less than 50% of their revenues from government or block grants. Centers that were ineligible based on telephone screening were replaced by a random selection of alternate centers. Face-to-face interviews took place with 327 centers between June 2009 and the end of 2011, representing a response rate of 87.7%.

During the face-to-face interviews at the respondent’s treatment program, questions related to the center’s organization and management were asked of the administrator, whereas questions related to treatment philosophy, caseload characteristics, and wraparound services were asked of the clinical director. Field interviewers were required to have at least a bachelor’s degree and had received extensive training in the administration of the instrument from the research team. Both studies were reviewed and approved by the University of Georgia’s Institutional Review Board. After we excluded cases that were missing on any variable, our final sample was 535 centers.

Measures

Dependent variables—wraparound services.

Treatment centers offered between 0 and 11 wraparound services. We created a count variable that included primary medical care, mental health care, HIV testing, child care, family counseling, educational services, vocational services, housing assistance, transportation, financial counseling, and legal assistance. Three was the most common number of services offered (mode = 3, n = 115), and 20 centers offered no wraparound services.

We also separated this variable into 11 dichotomous variables representing each wraparound service, and each individual service was used as a dependent variable in separate analyses. For most of the wraparound services (i.e., primary care, family counseling, educational services, vocational services, housing assistance, financial counseling, and legal services), the dichotomous variable was coded as 1 if the center provided the service onsite or through a formal contract/agreement. To be stringent in our analyses, we did not code these variables as 1 if the center offered the service through informal agreements. For the remaining four wraparound services, centers were asked if the service was available onsite, and services were coded as 1 if the center answered affirmatively.

Independent variables—client characteristics.

We included five client characteristics in the analyses: the percentage of women, adolescents, unemployed, trauma survivors, and criminal justice referrals (e.g., driving under the influence [DUI]/drug courts, probation, parole) in a treatment program.

Control variables—organizational characteristics.

We controlled for organizational characteristics that could affect the provision of wraparound services.

Size: Size was measured through the client census in the center. This variable was logged to adjust for skew. On average, centers reported a daily census of 53 clients.

Hospital setting: For this dichotomous variable, a center was coded as 1 if it provided treatment in a hospital setting and coded as 0 if it was not in a hospital setting.

Private funding: This variable was the percentage of funding that came from sources other than governmental grants or contracts. This variable ranged from 0 to 100 and included Medicaid, Medicare private insurance, client fees, charitable contributions, revenue from capital funds, and/ or other private sources. Unlike government block grants, Medicaid and Medicare were not regarded as block funding because they are not guaranteed sources of revenue and are thus more similar to other private sources.

Accredited: This was a dichotomous variable in which a center was coded as 1 if it received accreditation from the Joint Commission (JC) or the Commission on Accreditation of Rehabilitation Facilities (CARF) and coded as 0 if it was not accredited by either the JC or the CARF.

Age: This variable was the age of the center, in years, where 0 indicated that a center was in its first year of operation. The average age of a treatment center was just over 27 years.

Outpatient services: In this dichotomous variable, a center was coded as 1 if it offered outpatient services only and as 0 if it offered either inpatient/residential services or a combination of inpatient/residential and outpatient services.

Private sample: This dichotomous variable indicated which sample the data came from (1 = private sample, 0 = nonprivate sample).

Analytic strategy

Our analyses proceeded in two steps. First, we used the count variable representing the number of wraparound services available in a treatment center as the dependent variable. Because this variable was inherently discrete (i.e., comprising only whole numbers) and bounded at zero, a count model was the most appropriate method for analysis. We used a negative binomial regression to model the relationship between client characteristics and the provision of wraparound services. Second, we estimated each of the 11 wraparound services as separate dependent variables in order to examine the relationship between client characteristics and each wraparound service. Hence, we could examine how specific wraparound services were available in centers with different groups of clients.

Results

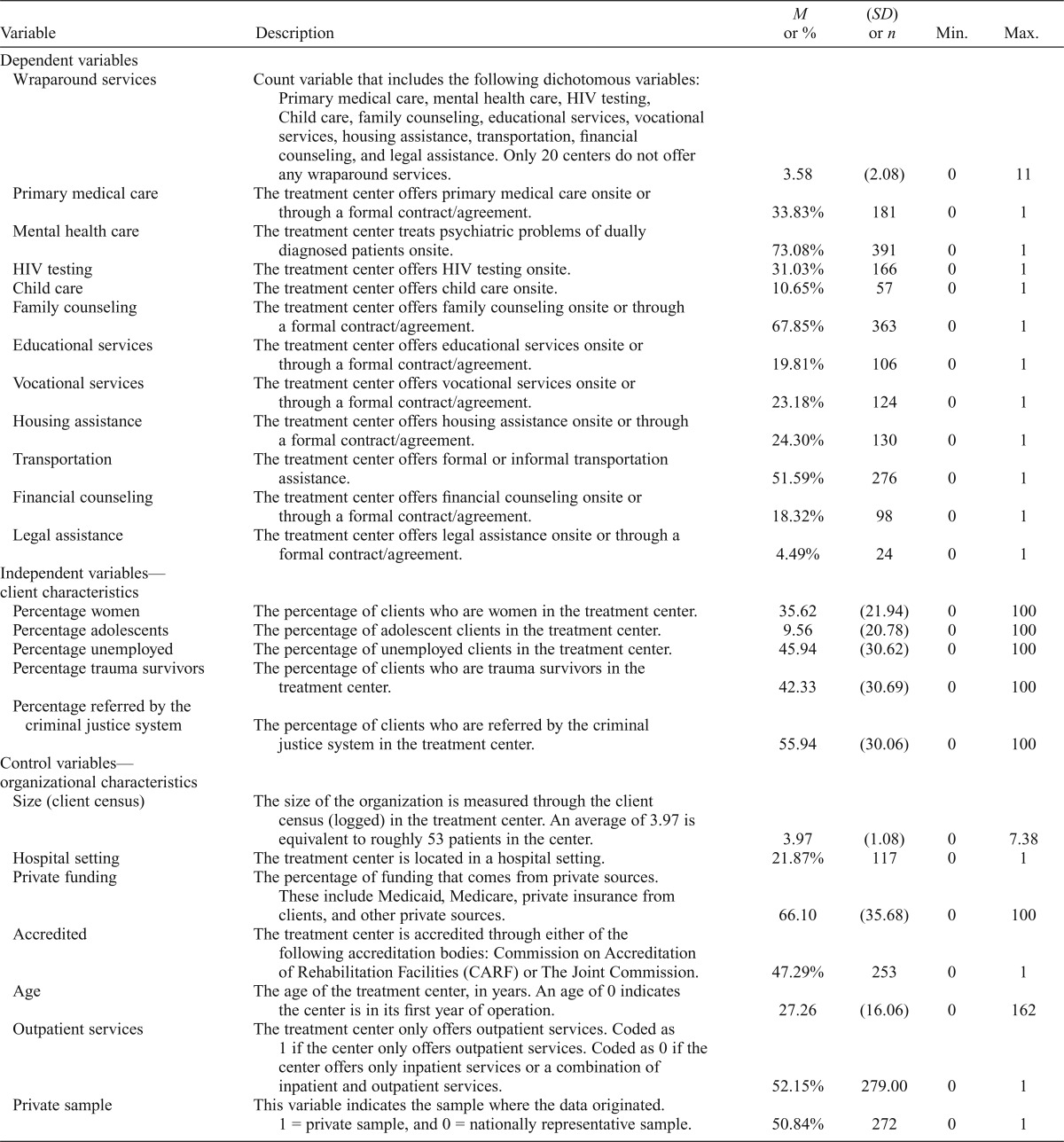

Table 1 provides descriptive statistics for the sample. We found that 96.3% of centers offered at least one wraparound service. On average, centers offered between three and four types of wraparound services (M = 3.6), although more than 15% of the centers offered five or more. The most common wraparound services offered were mental health care services and family counseling. We found that 73.1% of treatment centers offered mental health care, and 67.9% of centers offered family counseling. Legal assistance and child care were the least common wraparound services offered, with only 4.5% of centers offering legal assistance, and 10.7% of centers offering child care services.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics (N = 535)

| Variable | Description | M or % | (SD) or n | Min. | Max. |

| Dependent variables | |||||

| Wraparound services | Count variable that includes the following dichotomous variables: | 3.58 | (2.08) | 0 | 11 |

| Primary medical care, mental health care, HIV testing, Child care, family counseling, educational services, vocational services, housing assistance, transportation, financial counseling, and legal assistance. Only 20 centers do not offer any wraparound services. | |||||

| Primary medical care | The treatment center offers primary medical care onsite or through a formal contract/agreement. | 33.83% | 181 | 0 | 1 |

| Mental health care | The treatment center treats psychiatric problems of dually diagnosed patients onsite. | 73.08% | 391 | 0 | 1 |

| HIV testing | The treatment center offers HIV testing onsite. | 31.03% | 166 | 0 | 1 |

| Child care | The treatment center offers child care onsite. | 10.65% | 57 | 0 | 1 |

| Family counseling | The treatment center offers family counseling onsite or through a formal contract/agreement. | 67.85% | 363 | 0 | 1 |

| Educational services | The treatment center offers educational services onsite or through a formal contract/agreement. | 19.81% | 106 | 0 | 1 |

| Vocational services | The treatment center offers vocational services onsite or through a formal contract/agreement. | 23.18% | 124 | 0 | 1 |

| Housing assistance | The treatment center offers housing assistance onsite or through a formal contract/agreement. | 24.30% | 130 | 0 | 1 |

| Transportation | The treatment center offers formal or informal transportation assistance. | 51.59% | 276 | 0 | 1 |

| Financial counseling | The treatment center offers financial counseling onsite or through a formal contract/agreement. | 18.32% | 98 | 0 | 1 |

| Legal assistance | The treatment center offers legal assistance onsite or through a formal contract/agreement. | 4.49% | 24 | 0 | 1 |

| Independent variables—client characteristics | |||||

| Percentage women | The percentage of clients who are women in the treatment center. | 35.62 | (21.94) | 0 | 100 |

| Percentage adolescents | The percentage of adolescent clients in the treatment center. | 9.56 | (20.78) | 0 | 100 |

| Percentage unemployed | The percentage of unemployed clients in the treatment center. | 45.94 | (30.62) | 0 | 100 |

| Percentage trauma survivors | The percentage of clients who are trauma survivors in the treatment center. | 42.33 | (30.69) | 0 | 100 |

| Percentage referred by the criminal justice system | The percentage of clients who are referred by the criminal justice system in the treatment center. | 55.94 | (30.06) | 0 | 100 |

| Control variables—organizational characteristics Size (client census) | The size of the organization is measured through the client census (logged) in the treatment center. An average of 3.97 is equivalent to roughly 53 patients in the center. | 3.97 | (1.08) | 0 | 7.38 |

| Hospital setting | The treatment center is located in a hospital setting. | 21.87% | 117 | 0 | 1 |

| Private funding | The percentage of funding that comes from private sources. These include Medicaid, Medicare, private insurance from clients, and other private sources. | 66.10 | (35.68) | 0 | 100 |

| Accredited | The treatment center is accredited through either of the following accreditation bodies: Commission on Accreditation of Rehabilitation Facilities (CARF) or The Joint Commission. | 47.29% | 253 | 0 | 1 |

| Age | The age of the treatment center, in years. An age of 0 indicates the center is in its first year of operation. | 27.26 | (16.06) | 0 | 162 |

| Outpatient services | The treatment center only offers outpatient services. Coded as 1 if the center only offers outpatient services. Coded as 0 if the center offers only inpatient services or a combination of inpatient and outpatient services. | 52.15% | 279.00 | 0 | 1 |

| Private sample | This variable indicates the sample where the data originated.1 = private sample, and 0 = nationally representative sample. | 50.84% | 272 | 0 | 1 |

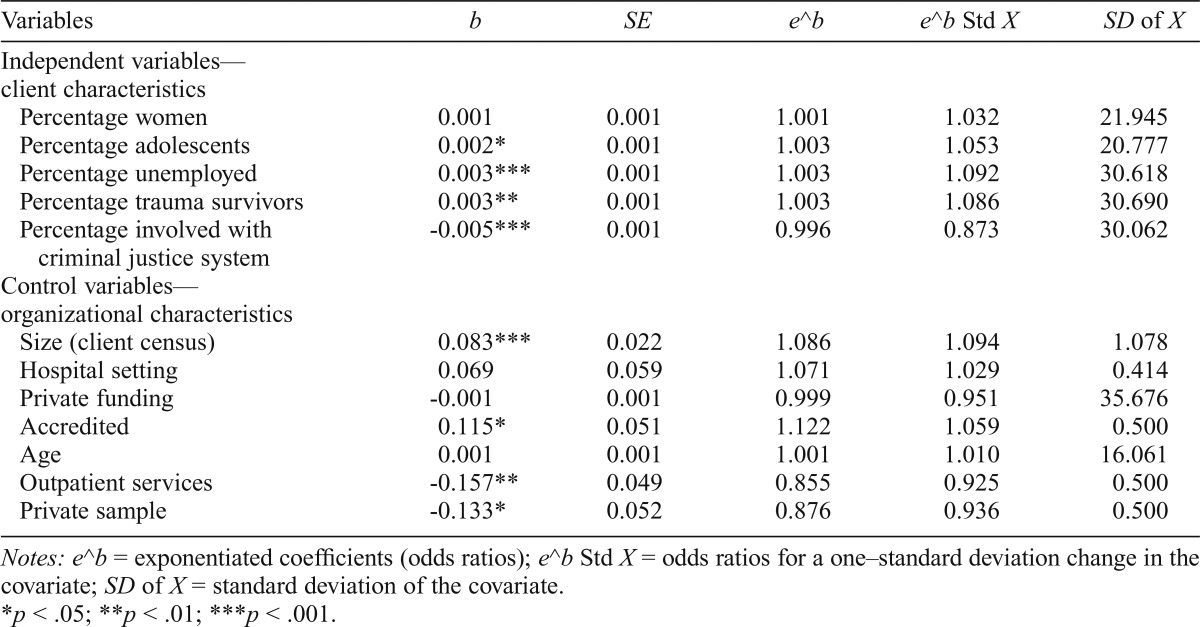

In Table 2 we present the results from the negative binomial regression. Our analyses revealed that specific client characteristics were significantly related to providing wraparound services. We found that the percentage of adolescent clients was positively related to the offering of more wraparound services. A 21% increase in the percentage of adolescents in a treatment program was associated with a 5% increase in the expected number of wraparound services. Similarly, as the percentage of unemployed clients increased, a center was more likely to offer a greater number of wraparound services. A greater proportion of trauma survivors also was associated with a greater number of wraparound services. A 31% increase in the percentage of clients who were trauma survivors increased the expected number of wraparound services by 9%, or by a factor of 1.086. We want to note that among centers that reported having any clients who were trauma survivors, 44% used standardized measures to identify a history of trauma. In contrast, the percentage of clients referred by the criminal justice system was negatively associated with a greater number of wraparound services. A 30% increase in the percentage of criminal justice clients decreased the expected number of wraparound services by 13%.

Table 2.

Negative binomial regression of wraparound services on client characteristics in treatment centers (N = 535)

| Variables | b | SE | e^b | e^b Std X | SD of X |

| Independent variables—client characteristics | |||||

| Percentage women | 0.001 | 0.001 | 1.001 | 1.032 | 21.945 |

| Percentage adolescents | 0.002* | 0.001 | 1.003 | 1.053 | 20.777 |

| Percentage unemployed | 0.003*** | 0.001 | 1.003 | 1.092 | 30.618 |

| Percentage trauma survivors | 0.003** | 0.001 | 1.003 | 1.086 | 30.690 |

| Percentage involved with criminal justice system Control variables—organizational characteristics | -0.005*** | 0.001 | 0.996 | 0.873 | 30.062 |

| Size (client census) | 0.083*** | 0.022 | 1.086 | 1.094 | 1.078 |

| Hospital setting | 0.069 | 0.059 | 1.071 | 1.029 | 0.414 |

| Private funding | -0.001 | 0.001 | 0.999 | 0.951 | 35.676 |

| Accredited | 0.115* | 0.051 | 1.122 | 1.059 | 0.500 |

| Age | 0.001 | 0.001 | 1.001 | 1.010 | 16.061 |

| Outpatient services | -0.157** | 0.049 | 0.855 | 0.925 | 0.500 |

| Private sample | -0.133* | 0.052 | 0.876 | 0.936 | 0.500 |

Notes: e^b = exponentiated coefficients (odds ratios); e^b Std X = odds ratios for a one–standard deviation change in the covariate; SD of X = standard deviation of the covariate.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

Organizational characteristics also were significantly related to the supplying of wraparound services. Larger treatment centers were more likely to offer a greater number of wraparound services. The expected numbers of wraparound services increased by 6% for accredited centers compared with nonaccredited centers. Centers that offered outpatient services only were negatively associated with offering a greater number of wraparound services. Finally, being in the privately funded sample was negatively associated with offering more wraparound services.

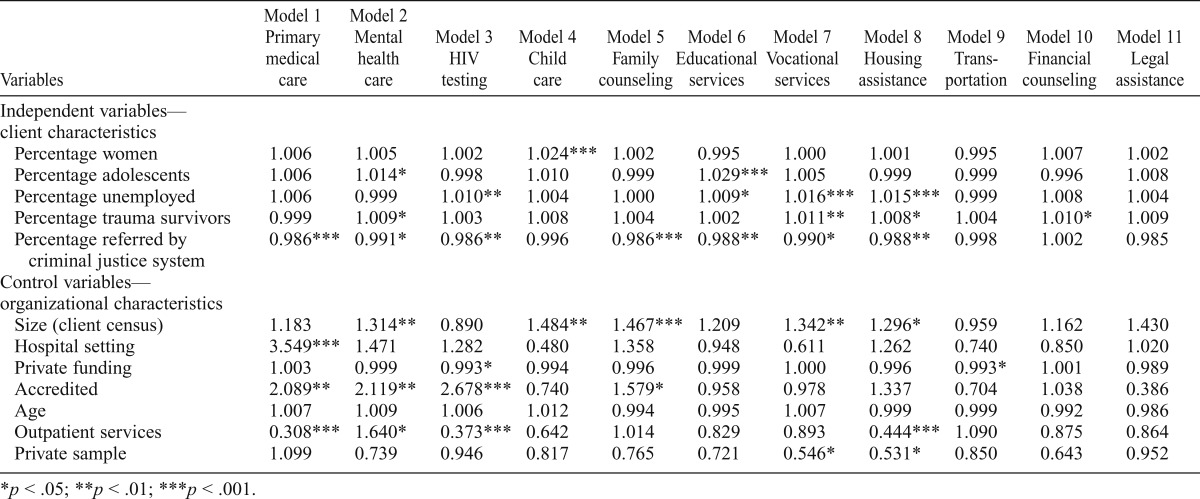

In Table 3, each wraparound service is a separate dependent variable; thus, we present 11 separate models so that we could understand how client characteristics affected each individual service. The negative binomial regression offered a comprehensive picture of the relationship between client characteristics and the overall provision of wraparound services but masked how client characteristics were related to each individual measure.

Table 3.

Logistic regressions of wraparound services on client characteristics in treatment centers (odds ratios) (N = 535)

| Variables | Model 1 Primary medical care | Model 2 Mental health care | Model 3 HIV testing | Model 4 Child care | Model 5 Family counseling | Model 6 Educational services | Model 7 Vocational services | Model 8 Housing assistance | Model 9 Transportation | Model 10 Financial counseling | Model 11 Legal assistance |

| Independent variables—client characteristics | |||||||||||

| Percentage women | 1.006 | 1.005 | 1.002 | 1.024*** | 1.002 | 0.995 | 1.000 | 1.001 | 0.995 | 1.007 | 1.002 |

| Percentage adolescents | 1.006 | 1.014* | 0.998 | 1.010 | 0.999 | 1.029*** | 1.005 | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.996 | 1.008 |

| Percentage unemployed | 1.006 | 0.999 | 1.010** | 1.004 | 1.000 | 1.009* | 1.016*** | 1.015*** | 0.999 | 1.008 | 1.004 |

| Percentage trauma survivors | 0.999 | 1.009* | 1.003 | 1.008 | 1.004 | 1.002 | 1.011** | 1.008* | 1.004 | 1.010* | 1.009 |

| Percentage referred by criminal justice system | 0.986*** | 0.991* | 0.986** | 0.996 | 0.986*** | 0.988** | 0.990* | 0.988** | 0.998 | 1.002 | 0.985 |

| Control variables—organizational characteristics | |||||||||||

| Size (client census) | 1.183 | 1.314** | 0.890 | 1.484** | 1.467*** | 1.209 | 1.342** | 1.296* | 0.959 | 1.162 | 1.430 |

| Hospital setting | 3.549*** | 1.471 | 1.282 | 0.480 | 1.358 | 0.948 | 0.611 | 1.262 | 0.740 | 0.850 | 1.020 |

| Private funding | 1.003 | 0.999 | 0.993* | 0.994 | 0.996 | 0.999 | 1.000 | 0.996 | 0.993* | 1.001 | 0.989 |

| Accredited | 2.089** | 2.119** | 2.678*** | 0.740 | 1.579* | 0.958 | 0.978 | 1.337 | 0.704 | 1.038 | 0.386 |

| Age | 1.007 | 1.009 | 1.006 | 1.012 | 0.994 | 0.995 | 1.007 | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.992 | 0.986 |

| Outpatient services | 0.308*** | 1.640* | 0.373*** | 0.642 | 1.014 | 0.829 | 0.893 | 0.444*** | 1.090 | 0.875 | 0.864 |

| Private sample | 1.099 | 0.739 | 0.946 | 0.817 | 0.765 | 0.721 | 0.546* | 0.531* | 0.850 | 0.643 | 0.952 |

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

For the majority of client characteristics included in these analyses, we found a significant and positive relationship between increased percentages of a particular client characteristic and at least one wraparound service. This was the case for the first four groups of clients: women, adolescents, unemployed, and trauma survivors. A greater percentage of female clients was positively related to the provision of onsite child care. A greater proportion of adolescent clients was positively related to the offering of mental health care and educational services. A greater percentage of unemployed clients was positively associated with the offering of HIV testing, educational services, vocational services, and housing assistance. An increase in the proportion of clients who were trauma survivors was positively associated with the offering of mental health care, vocational services, housing assistance, and financial counseling.

The variable of percentage of criminal justice clients was distinctly different from the other client characteristics included in these models. We found significant relationships, but these relationships were negative. A greater percentage of criminal justice clients was negatively related to seven wraparound services: primary medical care, mental health care, HIV testing, family counseling, educational services, vocational services, and housing assistance. These models demonstrated that the variable of proportion of clients referred by the criminal justice system had no significant positive relationships with any wraparound services.

Organizational characteristics were also connected to the offering of various wraparound services. We found that larger organizations were more likely to offer mental health care, child care, family counseling, vocational services, and housing assistance. If a treatment center was located in a hospital setting, the odds of it offering primary medical care were three times higher than if it was not hospital based. We also found that an increase in private funding was negatively associated with offering HIV testing and transportation for clients. Accredited centers were more likely than nonaccredited centers to offer primary medical care, mental health care, HIV testing, and family counseling. Centers that offered outpatient services only were less likely to offer primary medical care, HIV testing, and housing assistance, but these centers were significantly more likely to offer mental health care. Finally, treatment centers in the privately funded data set were significantly less likely to offer vocational and housing assistance.

Discussion

The goal of this study was twofold. First, we sought to uncover the relationship between treatment centers’ client characteristics and the overall number of wraparound services provided. Second, we wanted to understand how different types of clients were related to specific dimensions of centers’ offerings of these wraparound services within SUD treatment centers. Each component makes up a larger system of wraparound services crucial for comprehensive SUD treatment (NIDA, 2012), and although the sum of those services creates a wide range of services for SUD clients, each individual component addresses a unique need.

This study departs from other scholarship on wraparound services by using the treatment center as the unit of analysis rather than the individual, relying on a nationally representative data set (for exceptions, see Ducharme et al., 2007; Oser et al., 2009), and specifically examining the relationship between programs’ caseload characteristics and the provision of wraparound services.

Findings from the analyses presented above demonstrate that the majority of treatment centers (96%) offered at least one type of service, and most centers offered multiple wraparound services, suggesting that many treatment centers embraced a partially comprehensive model of treatment. Nevertheless, the average program offered fewer than half of the wraparound services endorsed by NIDA, perhaps suggesting that not all client needs are being addressed, and that centers fall short of NIDA’s ideal treatment model. Our work highlights the nuanced relationships that exist between client characteristics and various wraparound services.

Our findings revealed that client characteristics at the treatment program level were associated with the availability of wraparound services. Women have unique treatment needs and may be more likely to seek or remain in treatment when those needs are realized. Our findings indicated that the percentage of women was not significantly related to our comprehensive measure of wraparound services, but an increased percentage of female clients was positively associated with one key service—child care services.

This finding suggests that treatment center professionals are cognizant of their female clients’ possible child care needs and are providing child care assistance for their clients. Past findings suggest that women are more likely to complete residential treatment when they have their children with them (Szuster et al., 1996). It is also possible that the provision of gender-sensitive services may attract more women to a treatment program. Indeed, research has found that women cite lack of child care as a barrier to entering treatment (Grant, 1997) and that SUD programs’ provision of child care is an important facilitator in women’s treatment process (Howell & Chasnoff, 1999; Sword et al., 2004).

The desire for child custody was a strong motivator among women who resumed parenting following SUD treatment, and the provision of child care was necessary for preparing them to resume caretaking responsibilities (Carlson et al., 2006). Women are also more likely than men to demonstrate a need for mental health services (Ashley et al., 2003); despite this, the percentage of women in a center was not significantly related to the provision of mental health care services.

Our findings showed that an increased percentage of adolescents was positively associated with the comprehensive wraparound service measure. In addition, the percentage of adolescents was significantly related to two individual wraparound services—mental health care and educational services. Adolescents may be more likely than other SUD clients to want or need educational services. If treatment centers can assist in encouraging adolescents to receive SUD treatment while simultaneously providing them with educational services, adolescents may be more likely to stay in SUD treatment.

Compared with adult SUD clients, adolescent clients are at an even higher risk for co-occurring mental health problems (Chan et al., 2008; Esposito-Smythers et al., 2012), and our findings suggest that adolescents are receiving treatment in centers that offer services linked to their needs. These findings are encouraging and suggest that treatment centers are implementing select—but crucial—wraparound services for adolescents. Given that many adolescents enter treatment through the criminal justice system, it is unlikely that adolescents have as much choice as other clients in deciding which program to attend.

For a multitude of reasons, SUD clients may be unemployed while seeking treatment. We found that a greater proportion of unemployed clients was significantly and positively related to the offering of a greater number of wraparound services. Our logistic regressions suggest that treatment centers may be providing the wraparound services that are of the greatest use to unemployed SUD clients. It could also be that unemployed individuals seek treatment in programs that offer these services. For example, a greater proportion of unemployed clients in a treatment center was positively related to availability of educational services and vocational services, both of which may assist unemployed clients in job preparation, and housing assistance, which is often needed because of housing instability associated with substance use and unemployment.

Employment allows clients to establish positive activities and make new, sober contacts who can aid in the recovery process (SAMHSA, 2000). While past studies have found that few SUD treatment facilities provide vocational services (West, 2008), research links employment with longer retention in treatment and lower relapse rates among SUD clients (Henkel, 2011; Kidorf et al., 2004) and links participation in educational/vocational services with employment at follow-up (Atherton & Toriello, 2011). Thus, the availability of educational and vocational services may have long-term positive effects for unemployed SUD clients.

Trauma survivors also have experiences that require unique services. Our logistic regression models indicated that the percentage of trauma survivors was positively associated with the offering of mental health care. Moreover, an increase in the percentage of trauma survivors was positively associated with vocational services, housing assistance, and financial counseling. With high dropout rates among trauma survivors (Odenwald & Semrau, 2013), these wraparound services may be especially beneficial, and trauma survivors may be more likely to stay in treatment if they receive interventions that specifically address trauma. Past research suggests that trauma-focused SUD treatment is associated with improved substance-related and mental health symptoms and increased treatment duration (Amaro et al., 2007). Thus, trauma survivors may fare better in environments where comprehensive treatment approaches, including mental health care, are available.

It is important to note that only one group of clients included in our models had no positive associations with any wraparound services—clients referred by the criminal justice system. Of the 11 factors assessed, 7 were significantly and negatively related to this client characteristic: primary medical care, mental health care, HIV testing, family counseling, educational services, vocational services, and housing assistance. Thus, treatment centers with greater percentages of criminal justice clients are less likely to offer wraparound services.

This finding builds on previous research that finds a negative relationship between criminal justice clients and the offering of core services (Edwards et al., 2011). Arguably, clients who are referred by the criminal justice system are among the most vulnerable SUD clients and may have a great need for wraparound services in SUD treatment centers. Although we cannot be certain why there is a negative relationship between the proportion of criminal justice referrals and wraparound services, it is possible that criminal justice policies on reimbursement prevent treatment centers from adopting a wide variety of wraparound services. Even treatment programs based in correctional facilities do not offer as many wraparound services as their community-based counterparts (Grella et al., 2007).

Our findings, consistent with past research indicating that criminal justice clients receive fewer services than other clients, suggest that the tension between punishment and rehabilitation may make the provision of additional services beyond the immediate treatment of one’s SUD less of a priority for programs with such clients (Oser et al., 2009). A study on SUD programs serving criminal offenders found that organizations that believed rehabilitation was the best way to reduce crime were more likely to offer more wraparound services (Oser et al., 2009). Our findings also suggest that SUD treatment counselors may face several challenges when dealing with criminal justice-affiliated clients if they are not addressing the host of needs these clients are likely to have.

These findings point toward a serious concern. There has been a great deal of positive publicity associated with the increased use of drug courts and other diversion methods by which persons with less serious criminal offenses who have SUDs are referred to treatment rather than to incarceration (Tiger, 2013). Public attitudes are supportive of this policy direction to the extent that it involves minor criminal offenses and the individuals can actually benefit from treatment interventions (Pallone & Hennessy, 2003). The increase in the numbers of referrals from the criminal justice system has been a boon to many treatment programs in search of steady revenues.

But in the face of these positive developments, the data here show that clients referred from the criminal justice system may be receiving fewer elements of comprehensive treatment relative to other client groups. This suggests that the outcomes associated with these clients may prove deficient relative to the outcomes that are possible with a more comprehensive approach to SUD treatment. If long-term outcomes prove that criminal justice referrals do not do as well as other patients, the overall policy transition that has been placed in a positive light could be undermined and even reversed if other conditions support a perceived need to discontinue treatment and “get tough.”

Several study limitations should be noted. First, our results cannot be generalized to specific types of centers (e.g., Veterans Affairs facilities or correctional facilities). In addition, our data exist in the cross-section; thus, we cannot make causal claims with these analyses. Moreover, the survey questions from our data do not specifically address which clients receive the wraparound services provided in the center. Related to this constraint, we want to note that these data cannot fully capture how much variability exists between the services offered at the various treatment services. Thus, services like mental health care may (and likely do) vary from center to center. We hope that future work will take a more in-depth look at the variability in services offered (e.g., with qualitative or small-scale case study analyses).

Our analyses only included five client characteristics, but there are other important—and vulnerable—client populations receiving treatment for SUDs, and future research should consider expanding focus to other groups (e.g., pregnant women, elderly SUD clients). Moreover, the categories of client characteristics do overlap, but our data do not allow us to know the degree to which this is the case. For example, treatment centers do not report what percentage of their trauma survivors are also women or what percentage of those referred by the criminal justice system are also adolescents.

Despite extensive research linking the provision of wraparound services to positive client outcomes (Knight et al., 2010; Marsh et al., 2011; McLellan et al., 1998), many clients do not receive treatment in settings that provide the services required to meet their needs. Our findings are crucial for individuals and organizations that are providing SUD care in treatment centers across the United States.

SUD clients are not a monolithic group; different clients have different needs in SUD treatment, and client characteristics are an important part of those treatment differences. If specific groups of clients are not receiving services that are specifically geared toward their success, then practitioners may see gaps in the potential positive impact of the treatment they are delivering. Given the link between wraparound services and positive outcomes for SUD clients, funding sources should consider reimbursement practices for wraparound services. Treatment providers should also be aware of available funding streams for these services, and states should be given greater authority to fund wraparound services.

Footnotes

Data collection for these analyses was funded by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Grant R01AA015974 and National Institute on Drug Abuse Grant R37DA013110.

References

- Aletraris L., Edmond M. B., Roman P. M. Adoption of injectable naltrexone in U.S. substance use disorder treatment programs. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2015;76:143–151. doi:10.15288/jsad.2015.76.143. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aletraris L., Paino M., Edmond M. B., Roman P. M., Bride B. E. The use of art and music therapy in substance abuse treatment centers. Journal of Addictions Nursing. 2014;4:190–196. doi: 10.1097/JAN.0000000000000048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aletraris L., Roman PM. Provision of onsite HIV services in substance use disorder treatment programs: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2015;57:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2015.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amaro H., Chernoff M., Brown V., Arévalo S., Gatz M. Does integrated trauma-informed substance abuse treatment increase treatment retention? Journal of Community Psychology. 2007;35:845–862. doi:10.1002/jcop.20185. [Google Scholar]

- Apantaku-Olajide T., Ducray K., Byrne P, Smyth B. P. Perception of unmet needs and association with benzodiazepine misuse among patients on a methadone maintenance treatment programme. The Psychiatrist. 2012;36:169–174. doi:10.1192/pb.bp.111.03661. [Google Scholar]

- Ashley O. S., Marsden M. E., Brady T. M. Effectiveness of substance abuse treatment programming for women: A review. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2003;29:19–53. doi: 10.1081/ada-120018838. doi:10.1081/ADA-120018838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atherton W. L., Toriello P. J. A vocational counseling based substance abuse intensive outpatient program: Preliminary results of project working recovery. Journal of Rehabilitation Administration. 2011;35:61–71. [Google Scholar]

- Battjes R. J., Gordon M. S., O’Grady K. E., Kinlock T. W., Carswell M. A. Factors that predict adolescent motivation for substance abuse treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2003;24:221–232. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(03)00022-9. doi:10.1016/S0740-5472(03)00022-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell C. I., Alexander J. A., Lemak C. H. Organizational determinants of outpatient substance abuse treatment duration in women. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2009;37:64–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2008.09.012. doi:10.1016/j.jsat.2008.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson B. E., Matto H., Smith C. A., Eversman M. A pilot study of reunification following drug abuse treatment: Recovering the mother role. Journal of Drug Issues. 2006;36:877–902. doi:10.1177/002204260603600406. [Google Scholar]

- Chan Y. F., Dennis M. L., Funk R. R. Prevalence and comorbidity of major internalizing and externalizing problems among adolescents and adults presenting to substance abuse treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2008;34:14–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.12.031. doi:10.1016/j.jsat.2006.12.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claus R. E., Kindleberger L. R. Engaging substance abusers after centralized assessment: Predictors of treatment entry and dropout. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2002;34:25–31. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2002.10399933. doi:10.1080/02791072.2002.10399933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ducharme L. J., Mello H. L., Roman P. M., Knudsen H. K., Johnson J. A. Service delivery in substance abuse treatment: Reexamining “comprehensive” care. Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research. 2007;34:121–136. doi: 10.1007/s11414-007-9061-7. doi:10.1007/s11414-007-9061-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DuPont R. L., Caldeira K. M., DuPont H. S., Vincent K. B., Shea C. L., Arria A. M. America’s dropout crisis: The unrecognized connection to adolescent substance use. Rockville, MD: Institute for Behavior and Health, and Center on Young Adult Health and Development; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards J. R., Knight D. K., Flynn P M. Organizational correlates of service availability in outpatient substance abuse treatment programs. Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research. 2011;38:432–443. doi: 10.1007/s11414-010-9231-x. doi:10.1007/s11414-010-9231-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engberg J., Morral A. R. Reducing substance use improves adolescents’ school attendance. Addiction. 2006;101:1741–1751. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01544.x. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01544.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esposito-Smythers C., Walsh A., Spirito A., Rizzo C., Goldston D. B., Kaminer Y. Working with the suicidal client who also abuses substances. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2012;19:245–255. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2010.11.004. doi:10.1016/j.cbpra.2010.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman A. S., Granick S., Bransfield S., Kreisher C., Schwartz A. The consequences of drug use/abuse for vocational career: A longitudinal study of a male urban African-American sample. American Journal of Drug Abuse. 1996;22:57–73. doi: 10.3109/00952999609001645. doi:10.3109/00952999609001645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Guarda R. M., Peragallo N., Urrutia M. T., Vasquez E. P., Mitrani V. B. HIV risks, substance abuse, and intimate partner violence among Hispanic women and their intimate partners. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 2008;19:252–266. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2008.04.001. doi:10.1016/j.jana.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant B. F. Barriers to alcoholism treatment: Reasons for not seeking treatment in a general population sample. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1997;58:365–371. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1997.58.365. doi:10.15288/jsa.1997.58.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield S. F., Back S. E., Lawson K., Brady K. T. Substance abuse in women. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2010;33:339–355. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2010.01.004. doi:10.1016/j.psc.2010.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield S. F., Brooks A. J., Gordon S. M., Green C. A., Kropp F., McHugh R. K., Miele G. M. Substance abuse treatment entry, retention, and outcome in women: A review of the literature. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;86:1–21. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.05.012. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grella C. E., Greenwell L., Prendergast M., Farabee D., Hall E., Cartier J., Burdon W. Organizational characteristics of drug abuse treatment programs for offenders. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2007;32:291–300. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2007.01.001. doi:10.1016/j.jsat.2007.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henkel D. Unemployment and substance use: A review of the literature (1990-2010) Current Drug Abuse Reviews. 2011;4:4–27. doi: 10.2174/1874473711104010004. doi:10.2174/1874473711104010004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell E. M., Chasnoff I. J. Perinatal substance abuse treatment. Findings from focus groups with clients and providers. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 1999;17:139–148. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(98)00069-5. doi: 10.1016/S0740-5472(98)00069-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang S. Y., Deren S., Goldstein M. F. Relationships between childhood abuse and neglect experience and HIV risk behaviors among methadone treatment drop-outs. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2002;26:1275–1289. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(02)00412-x. doi:10.1016/S0145-2134(02)00412-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidorf M., Neufeld K., Brooner R. K. Combining stepped-care approaches with behavioral reinforcement to motivate employment in opioid-dependent outpatients. Substance Use & Misuse. 2004;39:2215–2238. doi: 10.1081/ja-200034591. doi:10.1081/JA-200034591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight D. K., Edwards J. R., Flynn P. M. Predictors of change in the provision of services within outpatient substance abuse treatment programs. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice. 2010;16:553–563. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0b013e3181cb4354. doi:10.1097/PHH.0b013e3181cb4354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knudsen H. K., Roman P. M. Financial factors and the implementation of medications for treating opioid use disorders. Journal of Addiction Medicine. 2012;6:280–286. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0b013e318262a97a. doi:10.1097/ADM.0b013e318262a97a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubiak S. P., Arfken C. L., Gibson E. S. Departments of corrections as purchasers of community-based treatment: A national study. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2009;36:420–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2008.08.009. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2008.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb R. J., Kirby K. C., Platt J. J. Treatment retention, occupational role, and cocaine use in methadone maintenance. American Journal on Addictions. 1996;5:12–17. doi:10.1111/j.1521-0391.1996.tb00278.x. [Google Scholar]

- Lidz V., Sorrentino D. M., Robison L., Bunce S. Learning from disappointing outcomes: An evaluation of prevocational interventions for methadone maintenance patients. Substance Use & Misuse. 2004;39:2287–2308. doi: 10.1081/ja-200034631. doi:10.1081/JA-200034631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machlan B., Brostrand H. L., Benshoff J. J. Vocational rehabilitation in substance abuse treatment programs. Journal of Teaching in the Addictions. 2005;3:71–80. doi:10.1300/J188v03n01_06. [Google Scholar]

- Magura S. The role of work in substance dependency treatment: A preliminary overview. Substance Use & Misuse. 2003;38:1865–1876. doi: 10.1081/ja-120024244. doi:10.1081/JA-120024244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magura S., Staines G. L., Blankertz L., Madison E. M. The effectiveness of vocational services for substance users in treatment. Substance Use & Misuse. 2004;39:2165–2213. doi: 10.1081/ja-200034589. doi:10.1081/JA-200034589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh J. C., Cao D., D’Aunno T. Gender differences in the impact of comprehensive services in substance abuse treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2004;27:289–300. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2004.08.004. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2004.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh J. C., D’Aunno T. A., Smith B. D. Increasing access and providing social services to improve drug abuse treatment for women with children. Addiction. 2000;95:1237–1247. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.958123710.x. doi:10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.958123710.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh J. C., Smith B. D., Bruni M. Integrated substance abuse and child welfare services for women: A progress review. Children and Youth Services Review. 2011;33:466–472. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2010.06.017. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2010.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan A. T., Hagan T. A., Levine M., Gould F., Meyers K., Bencivengo M., Durell J. Supplemental social services improve outcomes in public addiction treatment. Addiction. 1998;93:1489–1499. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1998.931014895.x. doi:10.1046/j.1360-0443.1998.931014895.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mee-Lee D. L., Shulman G. D., Fishman M. J., Gastfriend D. R., Griffith J. H. 2nd ed. Chevy Chase, MD: American Society of Addiction Medicine; 2001. ASAM patient placement criteria for the treatment of substance-related disorders, revised (ASAM PPC-2R) [Google Scholar]

- Mensinger J. L., Diamond G. S., Kaminer Y., Wintersteen M. B. Adolescent and therapist perception of barriers to outpatient substance abuse treatment. American Journal on Addictions, 15, Supplement s1. 2006:s16–s25. doi: 10.1080/10550490601003631. doi:10.1080/10550490601003631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. Principles of drug abuse treatment for criminal justice populations: A research based guide (NIH Publication No. 06–5316) Bethesda, MD: Author; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. Principles of drug addiction treatment: A research-based guide (3rd ed.) (NIH Publication No. 124180) Rockville, MD: Author; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson-Zlupko L., Kauffman E., Dore M. M. Gender differences in drug addiction and treatment: Implications for social work intervention with substance-abusing women. Social Work. 1995;40:45–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odenwald M., Semrau P. Dropout among patients in qualified alcohol detoxification treatment: The effect of treatment motivation is moderated by Trauma Load. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy. 2013;8:14. doi: 10.1186/1747-597X-8-14. doi:10.1186/1747-597X-8-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Office of National Drug Control Policy. 2013 Annual Report, Arrestee Drug Abuse Monitoring Program II. Washington, D.C.: Executive Office of the President; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Oser C., Knudsen H., Staton-Tindall M., Leukefeld C. The adoption of wraparound services among substance abuse treatment organizations serving criminal offenders: The role of a women-specific program. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2009;103(Supplement 1):S82–S90. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.12.008. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouimette P., Moos R. H., Finney J. W. PTSD treatment and 5-year remission among patients with substance use and posttraumatic stress disorders. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:410–414. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.2.410. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.71.2.410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pallone N. J., Hennessy J. J. To punish or to treat: Substance abuse within the context of oscillating attitudes toward correctional rehabilitation. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation. 2003;37:1–25. doi:10.1300/J076v37n03_01. [Google Scholar]

- Pelissier B., Jones N. A review of gender differences among substance abusers. Crime and Delinquency. 2005;51:343–372. doi:10.1177/0011128704270218. [Google Scholar]

- Platt J. J. Vocational rehabilitation of drug abusers. Psychological Bulletin. 1995;117:416–33. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.416. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pringle J. L., Emptage N. P., Hubbard R. L. Unmet needs for comprehensive services in outpatient addiction treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2006;30:183–189. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2005.11.006. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2005.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rich J. D., Boutwell A. E., Shield D. C., Key R. G., McKenzie M., Clarke J. G., Friedmann P. D. Attitudes and practices regarding the use of methadone in US state and federal prisons. Journal of Urban Health. 2005;82:411–419. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jti072. doi:10.1093/jurban/jti072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Room J. A. Work and identity in substance abuse recovery. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 1998;15:65–74. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(97)00250-x. doi:10.1016/S0740-5472(97)00250-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royse D., Leukefeld C., Logan T. K., Dennis M., Wechsberg W., Hoffman J., Inciardi J. Homelessness and gender in out-of-treatment drug users. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse: Encompassing All Addictive Disorders. 2000;26:283–296. doi: 10.1081/ada-100100605. doi: 10.1081/ADA-100100605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith-Rohrberg D., Bruce R. D., Altice F. L. Review of corrections-based therapy for opiate dependent patients: Implications for buprenorphine treatment among correctional populations. Journal of Drug Issues. 2004;34:451–480. doi:10.1177/002204260403400210. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series, No. 38. Chapter 1—The Need for Vocational Services. Rockville, MD: Center for Substance Abuse Treatment; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2012 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings (Vol. NSDUH Series H-46) Rockville, MD: Author; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Sword W., Niccols A., Fan A. “New Choices” for women with addictions: Perceptions of program participants. BMC Public Health. 2004;4:10–11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-4-10. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-4-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szuster R. R., Rich L. L., Chung A., Bisconer S. W. Treatment retention in women’s residential chemical dependency treatment: The effect of admission with children. Substance Use & Misuse. 1996;31:1001–1013. doi: 10.3109/10826089609072284. doi:10.3109/10826089609072284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Z., Claus R. E., Orwin R. G., Kissin W. B., Arieira C. Measurement of gender-sensitive treatment for women in mixed-gender substance abuse treatment programs. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2012;123:160–166. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.11.003. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiger R. Judging addicts: Drug courts and coercion in the justice system. New York, NY: New York University Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- West S. L. The utilization of vocational rehabilitation services in substance abuse treatment facilities in the U.S. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation. 2008;29:71–75. [Google Scholar]

- Widman M., Lidz V., DiGregorio G. J., Platt A. K., Robison L., Platt J. J. Health status of employed and unemployed methadone patients. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2000;18:287–289. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(99)00063-x. doi:10.1016/S0740-5472(99)00063-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeterian J. D., Greene M. C., Bergman B. G., Kelly J. F. Does mandated treatment benefit youth? A prospective investigation of adolescent justice system involvement, treatment motivation, and substance use outcomes. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly. 2013;31:431–449. doi: 10.1080/07347324.2013.831671. doi:10.1080/07347324.2013.831671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]