Abstract

Objective:

The purpose of this study was to outline a method to improve alcohol industry compliance with its self-regulatory advertising placement guidelines on television with the goal of reducing youth exposure to noncompliant advertisements.

Method:

Data were sourced from Nielsen (The Nielsen Company, New York, NY) for all alcohol advertisements on television in the United States for 2005–2012. A “no-buy” list, that is a list of cable television programs and networks to be avoided when purchasing alcohol advertising, was devised using three criteria: avoid placements on programs that were noncompliant in the past (serially noncompliant), avoid placements on networks at times of day when youth make up a high proportion of the audience (high-risk network dayparts), and use a “guardbanded” (or more restrictive) composition guideline when placing ads on low-rated programs (low rated).

Results:

Youth were exposed to 15.1 billion noncompliant advertising impressions from 2005 to 2012, mostly on cable television. Together, the three no-buy list criteria accounted for 99% of 12.9 billion noncompliant advertising exposures on cable television for youth ages 2–20 years. When we evaluated the no-buy list criteria sequentially and mutually exclusively, serially noncompliant ads accounted for 67% of noncompliant exposure, high-risk network-daypart ads accounted for 26%, and low rated ads accounted for 7%.

Conclusions:

These findings suggest that the prospective use of the no-buy list criteria when purchasing alcohol advertising could eliminate most noncompliant advertising exposures and could be incorporated into standard post-audit procedures that are widely used by the alcohol industry in assessing exposure to television advertising.

Excessive alcohol use is a risk factor for the three leading causes of death among adolescents: unintentional injuries, homicide, and suicide (Miniño, 2010). Alcohol use during adolescence has also been found to increase the risk of alcohol dependence during adulthood (Grant & Dawson, 1997). Furthermore, according to the 2013 Youth Risk Behavior Survey, approximately one in five high school students in the United States (21%) reports heavy episodic drinking, defined in the Youth Risk Behavior Survey as the consumption of five or more drinks in a row or within 2 hours (Kann et al., 2014). Adolescents who report heavy episodic drinking are also at higher risk for drinking and driving, violence and personal injury, dating violence or rape, and using other drugs (Miller et al., 2007).

Many individual factors influence adolescent initiation and use of alcohol, including age; gender; race/ethnicity; drinking by parents and other caregivers; drinking by peers; presence of older siblings in the home; personality characteristics, such as sensation seeking and rebelliousness; affective disorders, such as anxiety and depression; cultural factors, such as religiosity; environmental factors, such as alcohol policies; and developmental factors, such as cognitive development (Donovan, 2004; Masten et al., 2009; Naimi et al., 2013; Windle et al., 2009). However, even after controlling for these factors, research studies have found that exposure to alcohol advertising increases the risk that adolescents will initiate alcohol use, and that those who drink will do so more frequently and at higher intensity, thereby increasing the risk of alcohol-attributable harms (e.g., injuries) (Anderson et al., 2009; Grenard et al., 2013; Smith & Foxcroft, 2009).

Alcohol advertising and underage drinking

Alcohol advertising influences youth drinking by associating alcohol use with desirable attributes (e.g., attractiveness, sexual prowess, or masculinity) and by associating alcohol use with enjoyable activities (e.g., parties, celebrations, sports, and recreation) (Austin & Hust, 2005). Researchers have found that advertisements that tell a story, use humor, or include animals are particularly attractive to youth (Chen et al., 2005). Consistent with social cognitive theory (Bandura, 1986, 1994), many studies have found that alcohol advertising changes attitudes toward alcohol, promotes positive expectancies of alcohol use, and increases both intentions to drink and subsequent drinking behavior (Austin et al., 2006; Bekman et al., 2011; Dal Cin et al., 2009; Fleming et al., 2004; Morgenstern et al., 2011; Nicolai et al., 2012; Stacy et al., 1990).

In addition, the music, videography, and pacing of alcoholic beverage ads have been found to influence early phases of adolescents’ alcohol decision-making process by increasing the desirability of alcohol, increasing the realism of drinking situations portrayed in the ads, and increasing the underage viewer’s desire to emulate the portrayals (Pinkleton et al., 2001). Alcohol advertising portrayals linking drinking with risky activities (e.g., motorcycle racing, skiing, and snowboarding) have also been associated with increased tolerance for risky behaviors, including driving after drinking (Zwarun et al., 2006).

Anderson and colleagues (2009) and Smith and Foxcroft (2009) have summarized in review articles longitudinal research studies focused on the association between different forms of alcohol marketing and underage drinking behavior. Stacy and colleagues (2004), Collins and colleagues (2007), and Morgenstern and colleagues (2011) specifically examined the association between televised alcohol advertising and underage drinking. Stacy and colleagues used a variety of opportunity-based measures—including reported frequency of watching televised sports, frequency of watching other television programs popular with youth that contained alcohol advertising, and recalled frequency of seeing alcohol advertisements on television—to assess youth exposure to alcohol advertising. They found that each of these measures was associated with an increase in beer drinking among middle school students.

Collins and colleagues (2007) used an approach similar to that of Stacy and colleagues (2004) to assess youth exposure to alcohol advertising and found that exposure to alcohol advertisements on sports television was associated with an increase in beer drinking. In addition, Morgenstern and colleagues found that youth exposure to and recall of televised alcohol advertising had both a direct and a mediated effect on drinking and heavy episodic drinking. In this study, respondents were required to identify masked alcohol ads and report the frequency with which they had seen the ads. This advertising exposure was associated with current and heavy episodic drinking, both directly and through a mediated relationship with changes in attitudes and expectations toward drinking.

Critics of these longitudinal studies have suggested that the researchers have not adequately controlled for potential confounding factors that could explain all or part of the reported association between alcohol advertising and underage drinking (Nelson, 2010). However, these studies actually controlled for a large number of confounding factors, including parental and peer drinking; family coherence; religiosity; trait factors, such as deviance or impulsivity; demographic factors, including the age, sex, and race/ethnicity of study subjects; and environmental factors, such as participation in extracurricular activities and school attachment. It is possible that these studies did not account for additional confounding factors that were uncorrelated with covariates controlled for in the analysis, but such factors have not been identified. Thus, the published evidence suggests that, independent of other explanatory factors, exposure to alcohol advertising can increase the likelihood that youth will start drinking and will drink more if already drinking (Anderson et al., 2009). Given advertising’s influence on youth drinking behavior, regulation of advertising is a key concern of alcohol marketers, public health officials, parents, and families.

Regulation of alcohol advertising in the United States

In their landmark 2003 report to Congress on reducing underage drinking, the National Research Council and Institute of Medicine made reducing youth exposure to alcohol advertising a key recommendation (Bonnie & O’Connell, 2004). The principal means of limiting underage exposure to alcohol advertising in the United States is through a series of self-regulatory marketing guidelines produced by the alcohol advertisers themselves (Evans & Kelly, 1999; Evans et al., 2003, 2008, 2014). Trade associations for producers of distilled spirits (Distilled Spirits Council of the United States, 2011a), beer (The Beer Institute, 2011), and wine (The Wine Institute, 2011) have each produced a code of voluntary practices to guide advertising and marketing activities. These codes provide trade association members with guidelines on advertising content and placement. The intent of the placement guidelines is to limit underage exposure to advertising without limiting advertising to legal-age adults.

Since September 2003, advertising placement guidelines for all three alcohol trade associations have specified that alcohol advertisements be placed only in media in which the adult audience is proportionate to the U.S. adult population. From September 2003 to May 2011, this guideline translated into a minimum adult (ages 21 years and older) audience proportion of 70% (Distilled Spirits Council of the United States, 2011b; The Beer Institute, 2011; The Wine Institute, 2011). In June 2011, each trade association increased this minimum adult audience proportion to 71.6% to adjust for the 2010 census. The advertising codes are silent about the maximum underage audience (ages younger than 21 years), but by default, these adult limits translate into maximum underage audiences of 30% before June 2011 and 28.4% thereafter.

Because television audiences may vary from one telecast to the next, industry guidelines suggest using a 6-month average audience composition for a network program (if available), or a network–daypart combination to verify that the audience complies with the guidelines before placing an advertisement. The distilled spirits industry code (which it states applies to all categories of alcoholic beverages for its members) also advises advertisers to conduct semi-annual, after-the-fact audits on a random sample of ad placements to verify that they met compliance guidelines, and to take corrective action if noncompliant placements are found (Distilled Spirits Council of the United States, 2011b).

Previous recommendations of the Federal Trade Commission

In its 1999 review of the advertising practices of the alcohol industry, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) recommended that alcohol advertisers adopt “no-buy” lists of media that were likely to generate disproportionate underage exposure (Evans & Kelly, 1999). The no-buy list was cited once again as a best practice in the FTC’s 2003 report, noting that several makers of flavored malt beverages (i.e., “alcopops,” such as Mike’s Hard Lemonade and Smirnoff Ice) maintained a no-buy list of television networks that included MTV and UPN, and television programs such as Malcolm in the Middle, Gilmore Girls, and Boston Public (Evans et al. 2003). Both the 2008 and 2014 FTC reports noted the use of no-buy lists by alcohol advertisers when advertising placements in certain media were found to be out of compliance (Evans et al., 2008, 2014).

Aims of this study

The objective of this study was to outline a public health intervention—a no-buy list—that would reduce youth exposure to alcohol advertising within the current self-regulatory advertising environment. To develop the no-buy list intervention, we conducted a complete, after-the-fact audit of alcohol advertising on television to assess compliance with the alcohol industry’s self-regulatory audience composition guidelines from 2005 to 2012, and to assess the proportion of total underage exposure to alcohol advertising that resulted from ads placed on television programming that did not meet these guidelines (i.e., noncompliant advertising). The audit began in 2005 rather than 2003 to give alcohol advertisers time to adjust to the new purchasing standards and to allow for the fact that decisions regarding the placement of alcohol advertising may be made a year in advance of the date when the advertising is telecast. We set out to determine (a) the percentage of alcohol advertisements and percentage of underage alcohol advertising exposure derived from noncompliant advertisements; (b) the criteria that could be used to create a no-buy list for television alcohol advertising, and the parameters to be applied to set these criteria; and (c) the incremental impact of applying each of these no-buy list criteria on underage exposure to noncompliant alcohol advertising on cable television.

Method

Data source

Television advertising data for the years 2005–2012 were licensed from Nielsen (The Nielsen Company, New York, NY) for all alcoholic beverage types in Nielsen’s alcohol category (beer, distilled spirits, alcopops or sweetened alcoholic beverages that taste like soda pop and contain malt-based alcohol, and wine). The details of our methods for processing and analyzing Nielsen data have been reported previously (Center on Alcohol Marketing and Youth, 2010). Briefly, occurrence and audience data were downloaded from Nielsen Monitor-Plus; coded to classify advertisements as product, “responsibility,” or other types of advertisements; standardized regarding brand names and alcohol types according to Impact Databank, a leading alcohol industry marketing research firm; and organized into a Microsoft SQL*SERVER database (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA). This study used data on 2,461,999 alcohol product advertisements on network, cable, and local television from 2005 through 2012, with a particular focus on 1,452,661 (59% of the total) cable television advertisements.

Measures

An advertising impression is a measure of exposure representing a single advertisement seen by a single viewer within a demographic group. Gross impressions are the sum of all advertising impressions, including multiple impressions seen by individuals. In this article, we will use the term impressions to represent gross impressions. On television, underage audience composition was defined as the proportion of underage viewers ages 2–20 years as a percentage of the total viewing audience ages 2 years and older (age 2 years is the youngest age reported in the Nielsen audience survey). A compliant advertisement was defined as an advertisement that was placed on a television program that complied with the alcohol industry’s self-regulatory placement guidelines (i.e., 30% or less of the viewing audience was underage from January 2005 through September 2011, and 28.4% or less of the viewing audience was underage thereafter). A noncompliant advertisement was defined as an advertisement that was placed on a television program that did not comply with the alcohol industry’s self-regulatory placement guidelines. Noncompliant exposure was defined as the number of advertising impressions seen by youth ages 2–20 years as a result of noncompliant advertisements.

Analysis

Compliance assessment.

Noncompliance was measured by calculating the proportion of advertisements and underage impressions generated by noncompliant advertisements. This noncompliance was assessed as a percentage of all alcohol advertising exposures (impressions) among persons ages 2 years or older (the method used by the FTC in its most recent report; Evans et al., 2014), and as a percentage of total advertising impressions among viewers ages 2–20 years. To determine which media type (cable network, spot or “local broadcast,” or broadcast network television) accounted for the majority of noncompliant exposure, we calculated noncompliant exposure by media type and by year (2005–2012).

Creation of a no-buy list.

We proposed the creation of a no-buy list using a series of three sequential and mutually exclusive ad purchasing restrictions that we shall refer to as no-buy list criteria. We describe these criteria in the next sections.

Serially noncompliant placements.

First, we examined advertisements placed on programs that were noncompliant in the previous year. Because alcohol companies are supposed to audit their performance relative to their placement guidelines (Distilled Spirits Council of the United States, 2011b), it should be possible to avoid repeatedly placing advertising on programs that have been found to be noncompliant in the past. We refer to advertising placements on programs that were found to be noncompliant in the previous year as “serially noncompliant” placements.

High-risk network dayparts.

Next, for the remaining noncompliant advertisements that were not found to be serially noncompliant, we examined whether the advertisements were placed on certain networks during times of the day (or “dayparts”) that were more likely to have disproportionately large youth audiences. This is an important consideration because advertisers often cannot specify that advertisements be placed on specific cable television programs and must instead purchase ads to run in certain network dayparts, or at any time on a network (so-called run-of-station or run-of-site advertising). Therefore, it is important to assess the impact of eliminating alcohol advertising on specific network dayparts when there is a high risk of noncompliance. After we excluded advertising that appeared on serially noncompliant programs, 90% of the remaining noncompliant advertising from 2005 to 2012 resulted from ads that were placed on 145 cable network dayparts. These 145 “high-risk network dayparts” accounted for 11.4% of the 1,272 total cable network dayparts on which alcohol advertising was placed during this period.

Low-rated cable television programs.

Finally, we examined how many of the remaining noncompliant advertisements—that is, advertisements that were neither serially noncompliant nor placed on high-risk network dayparts— appeared on low-rated cable television programs. Programs with low ratings have smaller audiences, and consequently the demographic characteristics (e.g., age distribution) of the viewers of these programs are likely to be less stable than for more highly rated programs with larger audiences due to measurement uncertainty.

Definition of low-rated cable television program.

Lowrated cable television programs were defined using television audience measurements by Nielsen, which are based on a nationally representative sample of households. Specifically, we used Nielsen data to calculate the coefficient of variation of the adult audience rating for all programs that ran alcohol advertisements from 2005 through 2012. This coefficient was calculated by dividing the standard deviation of all adult (age 21 and older) audience ratings for alcohol advertisements placed on cable television by the mean of all adult audience ratings on cable television. We then compared the coefficient of variation above and below adult audience rating thresholds of 1.5, 1.25, 1.0, 0.75, 0.50, and 0.25 to find a threshold where the coefficient of variation above the threshold was small relative to the coefficient of variation below the threshold (i.e., the threshold below which adult audience composition estimates became unstable).

We found that alcohol ads on cable television with an adult audience rating of 0.50 or less (which equates to approximately 1,000,000 or fewer adult viewers) had a coefficient of variation of 92.2, whereas the coefficient of variation for programs with an adult audience rating above 0.50 was 68.8. By contrast, the coefficient of variation for ads with an adult audience rating of 0.25 or less (83.2) was almost identical to programs with a rating above this threshold (80.2). Therefore, an adult audience rating of 0.50 represented the smallest threshold we tested in which there was considerably more fluctuation in adult audience ratings below the threshold compared with above the threshold. Based on this analysis, we classified alcohol ads placed on cable television programs with an adult audience rating below 0.50 as placements on “low-rated” programs.

Assessing the impact of a no-buy list.

To assess the impact of the three no-buy list criteria on reducing youth exposure from noncompliant ad placements, we calculated total underage exposure to alcohol advertising on cable television programs as well as the estimated reduction in noncompliant advertising exposure on these programs that could have been achieved by sequentially applying each of the three, mutually exclusive, no-buy list criteria: eliminating placement on serially noncompliant cable television programs; eliminating advertising during high-risk network dayparts; and finally, eliminating alcohol advertising on low-rated cable television programs. The potential reduction in noncompliant exposure was assessed for 2006–2012 rather than 2005–2012 because we needed to refer to placements in the prior year to classify noncompliant advertisements.

Guardbanding alcohol advertisements on low-rated cable programs.

With the proliferation of networks and programs on cable television, audiences for many cable programs may be relatively small. Therefore, it may not be feasible for alcohol advertisers to simply eliminate advertising on low-rated cable television programs because this would severely limit the programming available for placement of their advertisements. We therefore assessed the potential impact on noncompliant advertising of using a more restrictive underage audience composition limit for low-rated cable television programs—a technique called “guardbanding” (Shector, 1992). This approach has also been recently endorsed by the FTC. Specifically, the FTC has recommended that “if lack of compliance is due to wide fluctuations in measured audience composition due to small sample size, the [alcohol] company should consider using a higher [adult] audience threshold at the time of the placement to maximize the likelihood of post-placement compliance with the 71.6 percent audience composition standard” (Evans et al., 2014, Executive Summary, page iii).

To follow the FTC’s recommendation, alcohol companies would need to assess how much higher the adult audience composition must be (or how much lower the underage audience composition must be) to reliably meet their goals. Therefore, we evaluated the potential impact of various underage audience composition limits on noncompliant exposure the following year. To do so, we first calculated the average underage composition of low-rated cable television programs (i.e., programs with an adult rating of 0.50 or less) that ran alcohol advertising between 2005 and 2011. We then calculated the percentage of noncompliant advertisements that aired on that same television program in the following year (i.e., from 2006 through 2012). We then plotted the average underage composition in the prior year against the percentage of noncompliant advertisements in the following year and recommended a guardband range in a region of the resulting response curve that was relatively flat, providing protection against higher proportions of noncompliant ads due to fluctuations in the percentage of the viewing audience that was underage.

Results

Noncompliant alcohol advertising and advertising impressions

All television.

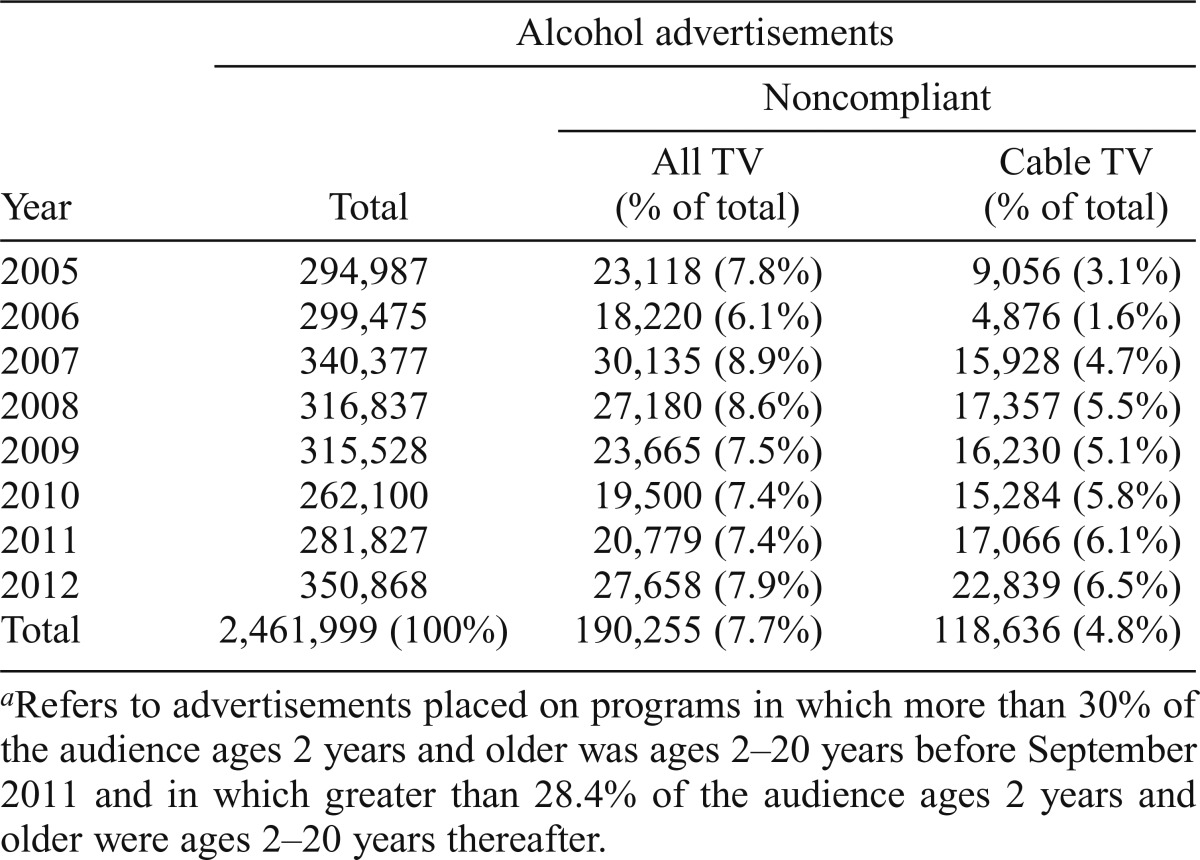

From 2005 through 2012, the alcohol industry spent $7.5 billion placing 2,461,999 advertisements on television, of which 190,255 (7.7%) were telecast on programs that exceeded the alcohol industry’s underage composition guidelines (i.e., were noncompliant) (Table 1). Beginning in 2007, the majority of noncompliant ad placements have been on cable television.

Table 1.

Total and noncompliant alcohol advertisementsa by television media type and year, 2005–2012

| Alcohol advertisements |

|||

| Noncompliant |

|||

| Year | Total | All TV (% of total) | Cable TV (% of total) |

| 2005 | 294,987 | 23,118 (7.8%) | 9,056 (3.1%) |

| 2006 | 299,475 | 18,220 (6.1%) | 4,876 (1.6%) |

| 2007 | 340,377 | 30,135 (8.9%) | 15,928 (4.7%) |

| 2008 | 316,837 | 27,180 (8.6%) | 17,357 (5.5%) |

| 2009 | 315,528 | 23,665 (7.5%) | 16,230 (5.1%) |

| 2010 | 262,100 | 19,500 (7.4%) | 15,284 (5.8%) |

| 2011 | 281,827 | 20,779 (7.4%) | 17,066 (6.1%) |

| 2012 | 350,868 | 27,658 (7.9%) | 22,839 (6.5%) |

| Total | 2,461,999 (100%) | 190,255 (7.7%) | 118,636 (4.8%) |

Refers to advertisements placed on programs in which more than 30% of the audience ages 2 years and older was ages 2–20 years before September 2011 and in which greater than 28.4% of the audience ages 2 years and older were ages 2–20 years thereafter.

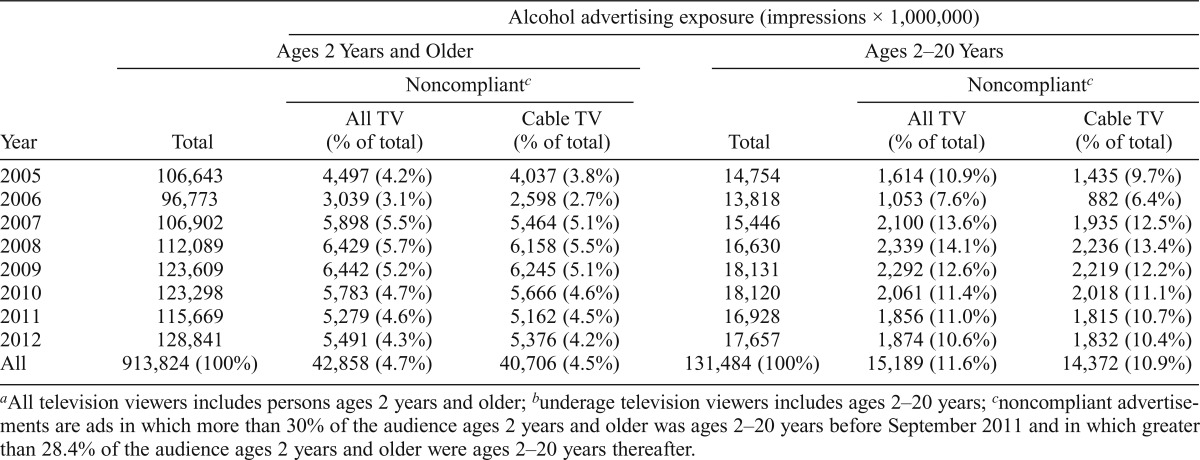

A total of 42.9 billion (4.7%) of the 913.8 billion alcohol advertising impressions viewed by all persons ages 2 years or older (i.e., by underage youth and legal-age adults) on all television programs from 2005 through 2012 were due to noncompliant advertising (Table 2). In contrast, 15.2 billion (11.6%) of the 131.5 billion alcohol advertising impressions viewed by persons ages 2–20 years on all television programs from 2005 through 2012 were generated by noncompliant advertisements.

Table 2.

Total and noncompliant alcohol advertising exposure by viewer age,a,b compliance status, and year, 2005–2012

| Alcohol advertising exposure (impressions × 1,000,000) |

||||||

| Ages 2 Years and Older |

Ages 2–20 Years |

|||||

| Noncompliantc |

Noncompliantc |

|||||

| Year | Total | All TV (% of total) | Cable TV (% of total) | Total | All TV (% of total) | Cable TV (% of total) |

| 2005 | 106,643 | 4,497 (4.2%) | 4,037 (3.8%) | 14,754 | 1,614 (10.9%) | 1,435 (9.7%) |

| 2006 | 96,773 | 3,039 (3.1%) | 2,598 (2.7%) | 13,818 | 1,053 (7.6%) | 882 (6.4%) |

| 2007 | 106,902 | 5,898 (5.5%) | 5,464 (5.1%) | 15,446 | 2,100 (13.6%) | 1,935 (12.5%) |

| 2008 | 112,089 | 6,429 (5.7%) | 6,158 (5.5%) | 16,630 | 2,339 (14.1%) | 2,236 (13.4%) |

| 2009 | 123,609 | 6,442 (5.2%) | 6,245 (5.1%) | 18,131 | 2,292 (12.6%) | 2,219 (12.2%) |

| 2010 | 123,298 | 5,783 (4.7%) | 5,666 (4.6%) | 18,120 | 2,061 (11.4%) | 2,018 (11.1%) |

| 2011 | 115,669 | 5,279 (4.6%) | 5,162 (4.5%) | 16,928 | 1,856 (11.0%) | 1,815 (10.7%) |

| 2012 | 128,841 | 5,491 (4.3%) | 5,376 (4.2%) | 17,657 | 1,874 (10.6%) | 1,832 (10.4%) |

| All | 913,824 (100%) | 42,858 (4.7%) | 40,706 (4.5%) | 131,484 (100%) | 15,189 (11.6%) | 14,372 (10.9%) |

All television viewers includes persons ages 2 years and older;

underage television viewers includes ages 2–20 years;

noncompliant advertisements are ads in which more than 30% of the audience ages 2 years and older was ages 2–20 years before September 2011 and in which greater than 28.4% of the audience ages 2 years and older were ages 2–20 years thereafter.

Cable television.

Of the 42.9 billion total noncompliant alcohol advertising impressions viewed by all persons ages 2 years or older, 40.7 billion (95.0%) aired on cable television programs (Table 2). Similarly, of the 15.2 billion total noncompliant alcohol advertising impressions viewed by persons ages 2–20 years from 2005 through 2012, 14.4 billion (94.6%) resulted from the 118,636 noncompliant advertisements that aired on cable television programs. We therefore focused the balance of our analyses on noncompliant alcohol advertisements and advertising impressions viewed by persons ages 2–20 years on cable television.

Noncompliant alcohol advertising on no-buy list cable programs

Serially noncompliant programs.

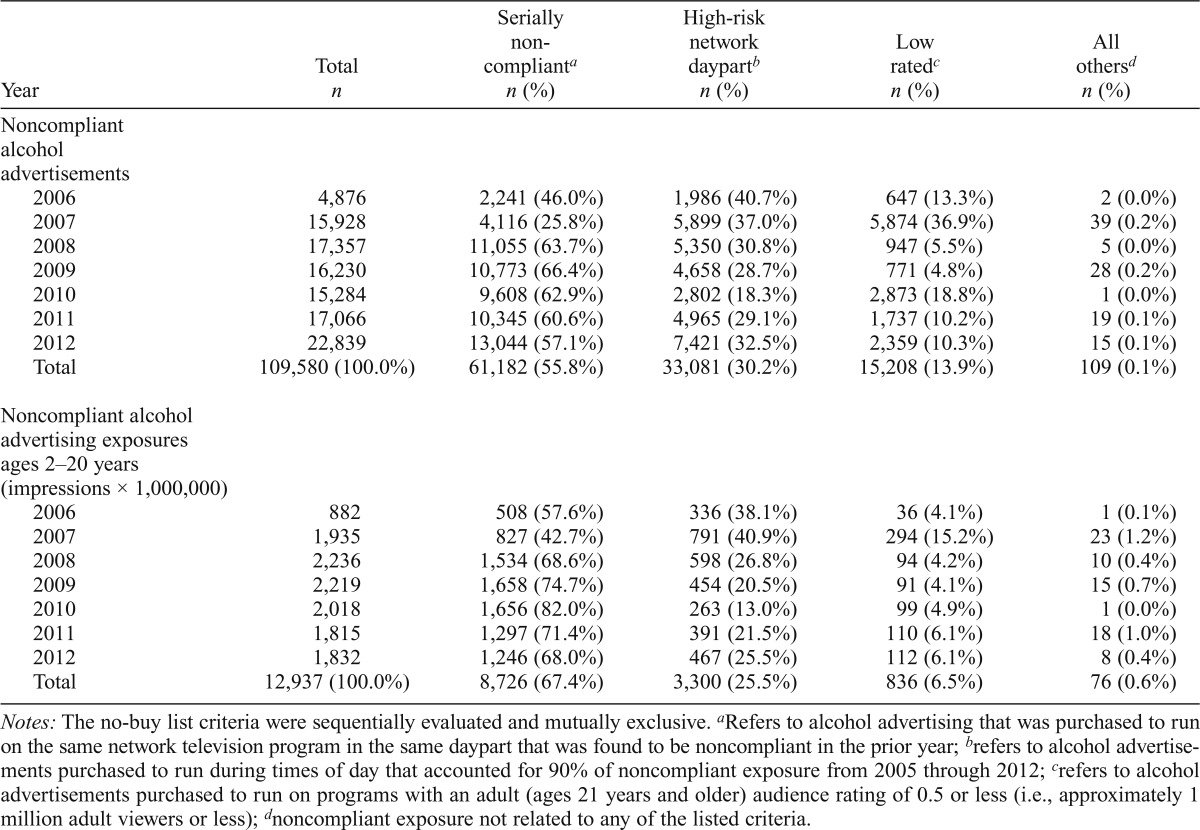

On cable television, more than half (55.8%) of the noncompliant advertisements viewed by persons ages 2–20 years from 2006 through 2012 were placed on serially noncompliant programs. These serially noncompliant ads accounted for 67.4% of all noncompliant exposure among viewers ages 2–20 years (Table 3).

Table 3.

Number and percentage of noncompliant alcohol advertisements and noncompliant alcohol advertising exposures on cable television programs classified by no-buy list criteria, 2006–2012

| Year | Total n | Serially non-complianta n (%) | High-risk network daypartb n (%) | Low ratedc n (%) | All othersd n (%) |

| Noncompliant alcohol advertisements | |||||

| 2006 | 4,876 | 2,241 (46.0%) | 1,986 (40.7%) | 647 (13.3%) | 2 (0.0%) |

| 2007 | 15,928 | 4,116 (25.8%) | 5,899 (37.0%) | 5,874 (36.9%) | 39 (0.2%) |

| 2008 | 17,357 | 11,055 (63.7%) | 5,350 (30.8%) | 947 (5.5%) | 5 (0.0%) |

| 2009 | 16,230 | 10,773 (66.4%) | 4,658 (28.7%) | 771 (4.8%) | 28 (0.2%) |

| 2010 | 15,284 | 9,608 (62.9%) | 2,802 (18.3%) | 2,873 (18.8%) | 1 (0.0%) |

| 2011 | 17,066 | 10,345 (60.6%) | 4,965 (29.1%) | 1,737 (10.2%) | 19 (0.1%) |

| 2012 | 22,839 | 13,044 (57.1%) | 7,421 (32.5%) | 2,359 (10.3%) | 15 (0.1%) |

| Total | 109,580 (100.0%) | 61,182 (55.8%) | 33,081 (30.2%) | 15,208 (13.9%) | 109 (0.1%) |

| Noncompliant alcohol advertising exposures ages 2–20 years (impressions × 1,000,000) | |||||

| 2006 | 882 | 508 (57.6%) | 336 (38.1%) | 36 (4.1%) | 1 (0.1%) |

| 2007 | 1,935 | 827 (42.7%) | 791 (40.9%) | 294 (15.2%) | 23 (1.2%) |

| 2008 | 2,236 | 1,534 (68.6%) | 598 (26.8%) | 94 (4.2%) | 10 (0.4%) |

| 2009 | 2,219 | 1,658 (74.7%) | 454 (20.5%) | 91 (4.1%) | 15 (0.7%) |

| 2010 | 2,018 | 1,656 (82.0%) | 263 (13.0%) | 99 (4.9%) | 1 (0.0%) |

| 2011 | 1,815 | 1,297 (71.4%) | 391 (21.5%) | 110 (6.1%) | 18 (1.0%) |

| 2012 | 1,832 | 1,246 (68.0%) | 467 (25.5%) | 112 (6.1%) | 8 (0.4%) |

| Total | 12,937 (100.0%) | 8,726 (67.4%) | 3,300 (25.5%) | 836 (6.5%) | 76 (0.6%) |

Notes: The no-buy list criteria were sequentially evaluated and mutually exclusive.

Refers to alcohol advertising that was purchased to run on the same network television program in the same daypart that was found to be noncompliant in the prior year;

refers to alcohol advertisements purchased to run during times of day that accounted for 90% of noncompliant exposure from 2005 through 2012;

refers to alcohol advertisements purchased to run on programs with an adult (ages 21 years and older) audience rating of 0.5 or less (i.e., approximately 1 million adult viewers or less);

noncompliant exposure not related to any of the listed criteria.

High-risk network dayparts.

After accounting for serially noncompliant placements, we found that total advertisements placed on high-risk network dayparts independently accounted for 30.2% of all noncompliant advertisements and 25.5% of all noncompliant exposure among viewers ages 2–20 years from 2006 to 2012 (Table 3).

Low-rated cable programs.

After accounting for advertisements on serially noncompliant programs and on high-risk network dayparts, we found that advertisements placed on low-rated cable television programs accounted for 13.9% of all noncompliant advertisements and 6.5% of all noncompliant exposure among viewers ages 2–20 years from 2006 to 2012 (Table 3). Taken together, advertisers could therefore eliminate the vast majority of noncompliant alcohol advertising exposure on cable television programs using a no-buy list based on these three purchasing criteria.

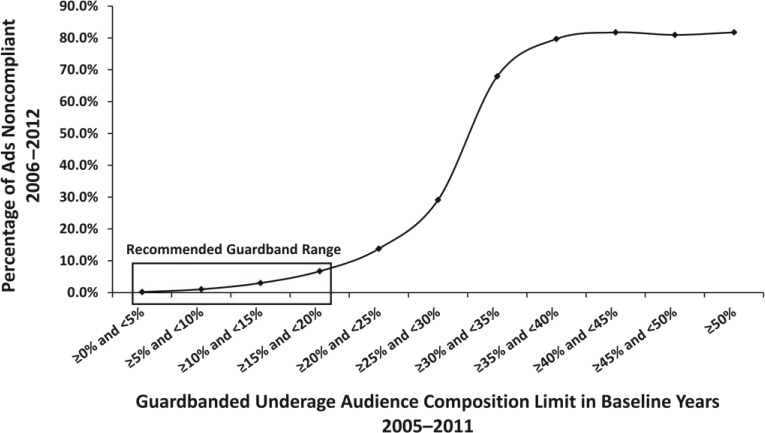

Guardbanding low-rated cable television programs

The effect of guardbanding low-rated programs on youth exposure to alcohol advertising is shown in Figure 1. Alcohol ads placed on low-rated programs with an average underage composition of at least 25% but less than 30% in a baseline year (the current alcohol industry standard) averaged close to 30% noncompliant placements in the following year, whereas ads placed on programs with an average underage composition of at least 30% but less than 35% (the prior alcohol industry standard) averaged more than 60% noncompliant placements in the following year. By contrast, alcohol ads placed using a guardbanded limit of 20% were associated with less than 10% noncompliant placements in the following year.

Figure 1.

Percentage of alcohol advertisements on low-rated cable television programs that exceeded the youth audience composition threshold during 2006–2012 based on the prior-year underage audience composition of purchased alcohol advertising. A “low-rated” program has an age 21 and older audience of fewer than 1,000,000 viewers (a rating of 0.50). A guardbanded audience composition limit is a lower audience composition threshold that is used to account for measurement variation so that the published specification is achieved.

Discussion

Underage youth were exposed to more than 15 billion noncompliant alcohol advertising impressions from 2005 through 2012, and almost all of these noncompliant impressions (96%) resulted from advertisements that aired on cable television programs. Furthermore, almost all of the noncompliant alcohol advertising exposures on cable television programs (99.4%) aired on programs that were either known to have previously violated the alcohol industry’s placement standards (i.e., were serially noncompliant), ran during periods that were known to be popular among underage youth (i.e., high-risk network dayparts), or were known to have a small number of adult viewers (i.e., low rated). Based on these findings, if the alcohol industry chose not to purchase alcohol advertising using these no-buy list criteria, youth could have been protected from viewing as many as 14 billion alcohol advertising impressions that were found to be noncompliant with industry standards during this 8-year period.

Our finding that most noncompliant alcohol advertising was placed on cable television programs is consistent with findings from other studies that have assessed youth exposure to alcohol advertising on television (Center on Alcohol Marketing and Youth, 2010). One recent study found that alcohol advertising exposure for underage youth ages 18–20 years was growing faster than that for any other age group and that this growth in exposure was attributable to the growth in alcohol advertising on cable television (Ross et al., 2014). Another study examining youth exposure to alcohol advertising in local television markets found a significant rise in exposure attributable to the increase in cable television advertising (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2013).

Implications for alcohol advertisers

Two thirds of noncompliant alcohol advertising exposures resulted from the placement of alcohol advertising on programs that were found to have noncompliant advertising in the previous year, and that another 1 of 4 noncompliant advertising exposures resulted from the placement of alcohol advertising on programs that aired during times of the day when underage youth were most likely to be watching (i.e., during high-risk network dayparts). Furthermore, after taking these previous two criteria into account, we found that almost the entire remaining balance of noncompliant exposure was attributable to advertising placements on low-rated programs. Taken together, these findings suggest that the prospective use of the no-buy list criteria when purchasing alcohol advertising is feasible and could be incorporated into standard post-audit procedures that are widely used by the alcohol industry in assessing exposure to television advertising.

Our findings also suggest that guardbanding the underage audience composition limit on low-rated cable television programs by lowering the underage audience composition limit from between 25% and 30% to between 15% and 20% could reduce the expected proportion of noncompliant exposure the following year by about two thirds (from an estimated 30% noncompliance to 10% noncompliance, respectively). This suggests that it is still possible to significantly reduce noncompliant alcohol advertising exposure on low-rated programs without entirely eliminating alcohol advertising on these programs, and thus contribute to the expected reduction in noncompliant advertising that could be achieved by implementing other no-buy list strategies, including eliminating advertising on serially noncompliant programs and on high-risk network dayparts.

Feasibility of no-buy list intervention

The proposed no-buy list, comprising the criteria outlined above, remedies virtually all noncompliant underage exposure. However, for it to be a viable intervention, the no-buy list must be implemented easily and cost-effectively. Companies should already be auditing their advertising placements to assess compliance and identify serially noncompliant programs or high-risk network dayparts. Thus, the intervention should not add a procedural burden. Nor should the intervention impose an excessive financial burden. A very small fraction of all cable television programs account for serially noncompliant advertising, and only 145 network dayparts of more than 1,200 account for almost all noncompliant advertising. Therefore, the cost to the advertiser to move out of these media should be minimal.

We are at a loss to explain why no-buy lists such as those proposed in this study are not used extensively. Research published nearly a decade ago estimated the short-term cash value of underage drinking to the alcohol industry at $22.5 billion in 2001 (Foster et al., 2006); however, there is no evidence that alcohol companies intentionally generate underage exposure to their advertising. It is possible that there is general complacency about the level of compliance already achieved. In its reviews of self-regulatory performance, the FTC has noted high levels of compliance (Evans et al., 2008, 2014). However, with more than 14 billion noncompliant underage advertising impressions occurring during the study period, there is room for improvement. There may also be a perception that measurement error in audience estimates makes achieving higher levels of compliance unobtainable. However, we have shown that using a guardbanded composition limit addresses the uncertainty in measuring audiences for television programs with lower ratings.

Future research should monitor adoption of these no-buy lists and assess any reduction in underage exposure from noncompliant advertising as well as the impact of any reductions in youth exposure on underage drinking outcomes.

Limitations of this study include our reliance on Nielsen’s television audience sampling methodology, which produces audience composition estimates with a high degree of variability for low-rated programs. However, these are the same data that are used by the alcohol industry to plan, execute, and monitor its advertising schedules, and thus represent the “gold standard” by which performance should be measured. Another limitation is the amount of overlap between our nobuy list criteria: most serially noncompliant advertisements are also found on high-risk network dayparts, and many of these same advertisements are on low-rated programs. However, these criteria were applied sequentially to independently assess their impact on reducing noncompliant advertisings. In addition, the ordering of these no-buy list criteria aligns with the alcohol industry’s current recommendations for conducting post-audits to assess compliance with self-regulatory guidelines on the placement of alcohol advertising and thus provides an appropriate basis for planning corrective measures. Furthermore, companies should already be identifying advertising placements that violate industry standards and taking corrective actions. Thus, it makes sense to assess compliance with no-buy list criteria in the order presented.

In summary, this study shows that the use of no-buy list criteria by alcohol advertisers could have eliminated youth exposure to as many as 14 billion noncompliant alcohol advertising impressions on cable television from 2005 to 2012. Although eliminating these 14 billion noncompliant alcohol advertising exposures is an important step toward reducing total youth exposure to alcohol advertising, advertising research has found that responses to advertising stimuli are nonlinear; consequently, lower levels of exposure to alcohol advertising can generate a greater response (e.g., greater likelihood of youth initiating alcohol use) on a per-exposure basis than higher levels of exposure (Ackoff & Emshoff, 1975; Rao & Miller, 1975; Ross et al., 2014; Wind & Sharp, 2009). Consistent with this finding, the National Research Council/Institute of Medicine and the attorneys general of 24 U.S. states and territories (Bonnie & O’Connell, 2004; Shurtleff et al., 2011) have recommended limiting the placement of alcohol advertising to media where youth ages 12–20 years are no more than 15% of the audience. Previous research has shown that this proposed threshold is economically feasible, does not limit the ability of alcohol companies to advertise to legal-age adults, and could reduce youth exposure to alcohol advertising by as much as 20% (Jernigan et al., 2005), thus further reducing the risk of underage drinking and the harms related to it. Nonetheless, our study shows that reducing noncompliant alcohol advertisements on cable television is an appropriate and achievable public health objective that would reduce exposure to this risk factor for underage drinking and, thus, complement evidence-based strategies for reducing underage and heavy episodic drinking that are currently recommended by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Community Preventive Services Task Force, including increasing alcohol taxes and regulating alcohol outlet density (Campbell et al., 2009; Elder et al., 2010).

Footnotes

This study was supported by Cooperative Agreement Number 5U58DP002027 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Craig Ross’s work on this project was supported, in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant T32 HD052458 (Boston University Reproductive, Perinatal, and Pediatric Epidemiology training program). This study’s contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or the National Institutes of Health.

References

- Ackoff R. L., Emshoff J. R. Advertising research at Anheuser-Busch, Inc. (1963-68) Sloan Management Review. 1975;16:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson P., de Bruijn A., Angus K., Gordon R., Hastings G. Impact of alcohol advertising and media exposure on adolescent alcohol use: A systematic review of longitudinal studies. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2009;44:229–243. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agn115. doi:10.1093/alcalc/agn115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin E. W., Chen M. J., Grube J. W. How does alcohol advertising influence underage drinking? The role of desirability, identification and skepticism. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006;38:376–384. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.08.017. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin E. W., Hust S. J. T. Targeting adolescents? The content and frequency of alcoholic and nonalcoholic beverage ads in magazine and video formats November 1999-April 2000. Journal of Health Communication. 2005;10:769–785. doi: 10.1080/10810730500326757. doi:10.1080/10810730500326757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social cognitive theory of mass communication. In: Bryant J., Zillmann D., editors. Media effects: Advances in theory and research. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1994. pp. 61–90. [Google Scholar]

- Bekman N. M., Anderson K. G., Trim R. S., Metrik J., Diulio A. R., Myers M. G., Brown S. A. Thinking and drinking: Alcohol-related cognitions across stages of adolescent alcohol involvement. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2011;25:415–425. doi: 10.1037/a0023302. doi:10.1037/a0023302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnie R. J., O’Connell M. E, editors. Reducing underage drinking: A collective responsibility. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell C. A., Hahn R. A., Elder R., Brewer R., Chattopadhyay S., Fielding J., Middleton J. C the Task Force on Community Preventive Services. The effectiveness of limiting alcohol outlet density as a means of reducing excessive alcohol consumption and alcohol-related harms. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2009;37:556–569. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.09.028. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2009.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center on Alcohol Marketing and Youth. Youth exposure to alcohol advertising on television, 2001-2009. Baltimore, MD: Author; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Youth exposure to alcohol advertising on television—25 markets, United States, 2010. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2013;62:877–880. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M. J., Grube J. W., Bersamin M., Waiters E., Keefe D. B. Alcohol advertising: What makes it attractive to youth? Journal of Health Communication. 2005;10:553–565. doi: 10.1080/10810730500228904. doi:10.1080/10810730500228904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins R. L., Ellickson P. L., McCaffrey D., Hambarsoomians K. Early adolescent exposure to alcohol advertising and its relationship to underage drinking. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2007;40:527–534. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.01.002. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dal Cin S., Worth K. A., Gerrard M., Gibbons F. X., Stoolmiller M., Wills T. A., Sargent J. D. Watching and drinking: Expectancies, prototypes, and friends’ alcohol use mediate the effect of exposure to alcohol use in movies on adolescent drinking. Health Psychology. 2009;28:473–483. doi: 10.1037/a0014777. doi:10.1037/a0014777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Distilled Spirits Council of the United States. Code of responsible practices for beverage alcohol advertising and marketing. Washington, DC: Author; 2011a. Retrieved from http://www.discus.org/assets/1/7/May_26_2011_DISCUS_Code_Word_Version1.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Distilled Spirits Council of the United States. Discus code media “buying” guidelines: Demographic data/advertisement placement guidelines. Washington, DC: Author; 2011b. Retrieved from http://www.discus.org/assets/1/7/Enhanced-Expanded_Buying_Guidelines_Updated_5-26-11_to_reflect_new_demographic_standard.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Donovan J. E. Adolescent alcohol initiation: A review of psychosocial risk factors. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2004;35:529.e7–528.e18. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.02.003. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elder R. W., Lawrence B., Ferguson A., Naimi T. S., Brewer R. D., Chattopadhyay S. K., Fielding J. E the Task Force on Community Preventive Services. The effectiveness of tax policy interventions for reducing excessive alcohol consumption and related harms. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2010;38:217–229. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.11.005. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2009.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans J., Dash J., Blickman N., Peeler C. L., Engle M. K., Mulholland J. Alcohol marketing and advertising: A report to congress. Washington, DC: Federal Trade Commission; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Evans J., Kelly R. Self-regulation in the alcohol industry: A review of industry efforts to avoid promoting alcohol to underage consumers. Washington, D.C: Federal Trade Commission; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Evans J. M., Krainsky E., Fentonmiller K., Brady C., Yoeli E., Jaroszewicz A. Self-regulation in the alcohol industry: Report of the Federal Trade Commission. Washington, DC: Federal Trade Commission; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Evans J., Marcus P., Engle M. K. Self-regulation in the alcohol industry: Report of the Federal Trade Commission. Washington, DC: Federal Trade Commission; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Fleming K., Thorson E., Atkin C. K. Alcohol advertising exposure and perceptions: Links with alcohol expectancies and intentions to drink or drinking in underaged youth and young adults. Journal of Health Communication. 2004;9:3–29. doi: 10.1080/10810730490271665. doi:10.1080/10810730490271665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster S. E., Vaughan R. D., Foster W. H., Califano J. A., Jr. Estimate of the commercial value of underage drinking and adult abusive and dependent drinking to the alcohol industry. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2006;160:473–478. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.5.473. doi:10.1001/archpedi.160.5.473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant B. F., Dawson D. A. Age at onset of alcohol use and its association with DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence: Results from the National Longitudinal Alcohol Epidemiologic Survey. Journal of Substance Abuse. 1997;9:103–110. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(97)90009-2. doi:10.1016/S0899-3289(97)90009-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grenard J. L., Dent C. W., Stacy A. W. Exposure to alcohol advertisements and teenage alcohol-related problems. Pediatrics. 2013;131:e369–e379. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-1480. doi:10.1542/peds.2012-1480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jernigan D. H., Ostroff J., Ross C. Alcohol advertising and youth: A measured approach. Journal of Public Health Policy. 2005;26:312–325. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.jphp.3200038. doi:10.1057/palgrave.jphp.3200038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kann L., Kinchen S., Shanklin S. L., Flint K. H., Hawkins J., Harris W., Zaza S. Youth risk behavior surveillance – United States, 2013. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report Surveillance Summaries. 2014;63(SS04):1–168. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/ss6304a1.htm. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masten A. S., Faden V. B., Zucker R. A., Spear L. P. A developmental perspective on underage alcohol use. Alcohol Research & Health. 2009;32:3–15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller J. W., Naimi T. S., Brewer R. D., Jones S. E. Binge drinking and associated health risk behaviors among high school students. Pediatrics. 2007;119:76–85. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1517. doi:10.1542/peds.2006-1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miniño A. Mortality among teenagers aged 12-19 years: United States, 1999-2006 NCHS data brief. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgenstern M., Isensee B., Sargent J. D., Hanewinkel R. Attitudes as mediators of the longitudinal association between alcohol advertising and youth drinking. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2011;165:610–616. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.12. doi:10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naimi T. S., Nelson T. F., Blanchette J. G., Heeren T., Nguyen T., Oussayef N., Xuan Z. State-level environment of alcohol policies targeting the general population and drinking among high school aged youth. Paper presented at the American Public Health Association 141st Annual Meeting; Boston, MA: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson J. P. What is learned from longitudinal studies of advertising and youth drinking and smoking? A critical assessment. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2010;7:870–926. doi: 10.3390/ijerph7030870. doi:10.3390/ijerph7030870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolai J., Moshagen M., Demmel R. Patterns of alcohol expectancies and alcohol use across age and gender. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2012;126:347–353. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.05.040. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.05.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinkleton B. E., Austin E. W., Fujioka Y. The relationship of perceived beer ad and PSA quality to high school students’ alcohol-related beliefs and behaviors. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media. 2001;45:575–597. doi:10.1207/s15506878jobem4504_3. [Google Scholar]

- Rao A. G., Miller P. B. Advertising/sales response functions. Journal of Advertising Research. 1975;15:7–15. [Google Scholar]

- Ross C. S., Maple E., Siegel M., DeJong W., Naimi T. S., Ostroff J., Jernigan D. H. The relationship between brand-specific alcohol advertising on television and brand-specific consumption among underage youth. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2014;38:2234–2242. doi: 10.1111/acer.12488. doi:10.1111/acer.12488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross C. S., Ostroff J., Jernigan D. H. Evidence of underage targeting of alcohol advertising on television in the United States: Lessons from the Lockyer v. Reynolds decisions. Journal of Public Health Policy. 2014;35:105–118. doi: 10.1057/jphp.2013.52. doi:10.1057/jphp.2013.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shector E. S. Managing for world-class quality: A primer for executives and managers. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Shurtleff M., Gansler D., Horne T., Jepsen G., Biden J., III, Rapadas L., et al. 2011. RE: Alcohol Reports, Paperwork Comment; Project No. P114503. A communication from the chief legal officers of the following states: Arizona, Connecticut, Delaware, Guam, Hawaii, Idaho, Illinois, Iowa, Maryland, Massachusetts, Mississippi, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Mexico, New York, Oklahoma, Oregon, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Tennessee, Utah, Vermont, Washington, Wyoming.

- Smith L. A., Foxcroft D. R. The effect of alcohol advertising, marketing and portrayal on drinking behaviour in young people: Systematic review of prospective cohort studies. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:51. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-51. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-9-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stacy A. W., Widaman K. F., Marlatt G. A. Expectancy models of alcohol use. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1990;58:918–928. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.58.5.918. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.58.5.918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stacy A. W., Zogg J. B., Unger J. B., Dent C. W. Exposure to televised alcohol ads and subsequent adolescent alcohol use. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2004;28:498–509. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.28.6.3. doi:10.5993/AJHB.28.6.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Beer Institute. Advertising and marketing code. Washington, DC: Author; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- The Wine Institute. Code of advertising standards. 2011 Retrieved from http://www.wineinstitute.org/initiatives/issuesandpolicy/adcode/details.

- Wind Y., Sharp B. Advertising empirical generalizations: Implications for research and action. Journal of Advertising Research. 2009;49:246–252. doi:10.2501/S0021849909090369. [Google Scholar]

- Windle M., Spear L. P., Fuligni A. J., Angold A., Brown J. D., Pine D, Dahl R. E. Transitions into underage and problem drinking: Summary of developmental processes and mechanisms: Ages 10-15. Alcohol Research & Health. 2009;32:30–40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwarun L., Linz D., Metzger M., Kunkel D. Effects of showing risk in beer commercials to young drinkers. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media. 2006;50:52–77. doi:10.1207/s15506878jobem5001_4. [Google Scholar]