Abstract

Objectives:

To determine the incidence and risk factors of mortality for all HIV-infected patients receiving antiretroviral treatment at public and private healthcare facilities in the Botswana National HIV/AIDS Treatment Programme.

Design:

We studied routinely collected data from 226 030 patients enrolled in the Botswana National HIV/AIDS Treatment Programme from 2002 to 2013.

Methods:

A person-years (P-Y) approach was used to analyse all-cause mortality and follow-up rates for all HIV-infected individuals with documented antiretroviral therapy initiation dates. Marginal structural modelling was utilized to determine the effect of treatment on survival for those with documented drug regimens. Sensitivity analyses were performed to assess the robustness of our results.

Results:

Median follow-up time was 37 months (interquartile range 11–75). Mortality was highest during the first 3 months after treatment initiation at 11.79 (95% confidence interval 11.49–12.11) deaths per 100 P-Y, but dropped to 1.01 (95% confidence interval 0.98–1.04) deaths per 100 P-Y after the first year of treatment. Twelve-month mortality declined from 7 to 2% of initiates during 2002–2012. Tenofovir was associated with lower mortality than stavudine and zidovudine.

Conclusion:

The observed mortality rates have been declining over time; however, mortality in the first year, particularly first 3 months of antiretroviral treatment, remains a distinct problem. This analysis showed lower mortality with regimens containing tenofovir compared with zidovudine and stavudine. CD4+ cell count less than 100 cells/μl, older age and being male were associated with higher odds of mortality.

Keywords: ART, Botswana, HIV, marginal structural model, mortality

Introduction

Botswana is one of the countries hardest hit with the HIV pandemic [1]. To respond to this public health menace, the Government of Botswana launched its national antiretroviral therapy (ART) programme called ‘Masa’, meaning ‘new dawn’ in Setswana. By the end of 2014, the programme had expanded to more than 302 healthcare facilities, and eligibility requirements had increased the CD4+ threshold to 350 cells/μl. By December 2014, the number of patients ever initiated ART had reached 247 856, of which 229 133 were in the public sector [2].

Prior studies have shown the success of this programme in Botswana [3,4]. However, these studies were hampered by small sample sizes. An analysis of the routinely collected patient data is needed to evaluate the performance of the national programme over time.

This study builds on our prior work [5], by providing a rigorous evaluation of 12 years of follow-up data for adult patients in the Masa Programme. This analysis was designed to evaluate rates of mortality, while identifying potential risk factors for mortality, including clinical and demographic factors.

Methods

Data

We analysed a database of all available electronic records routinely collected for 226 030 HIV-infected adults from 176 healthcare facilities enrolled in the Masa Programme with a documented ART initiation date. Once eligible for ART, data are collected through a patient information management system (PIMS) developed by the Ministry of Health (MOH) in Microsoft Access, or in nine major hospitals and 12 clinics, through a commercial information system. All available databases were integrated in a Microsoft SQL database in the data warehouse at the MOH. Despite the fact that all hospitals and most clinics had an electronic information system by the end of 2012, data are not always routinely entered and reported consistently for all facilities due to inadequate resources.

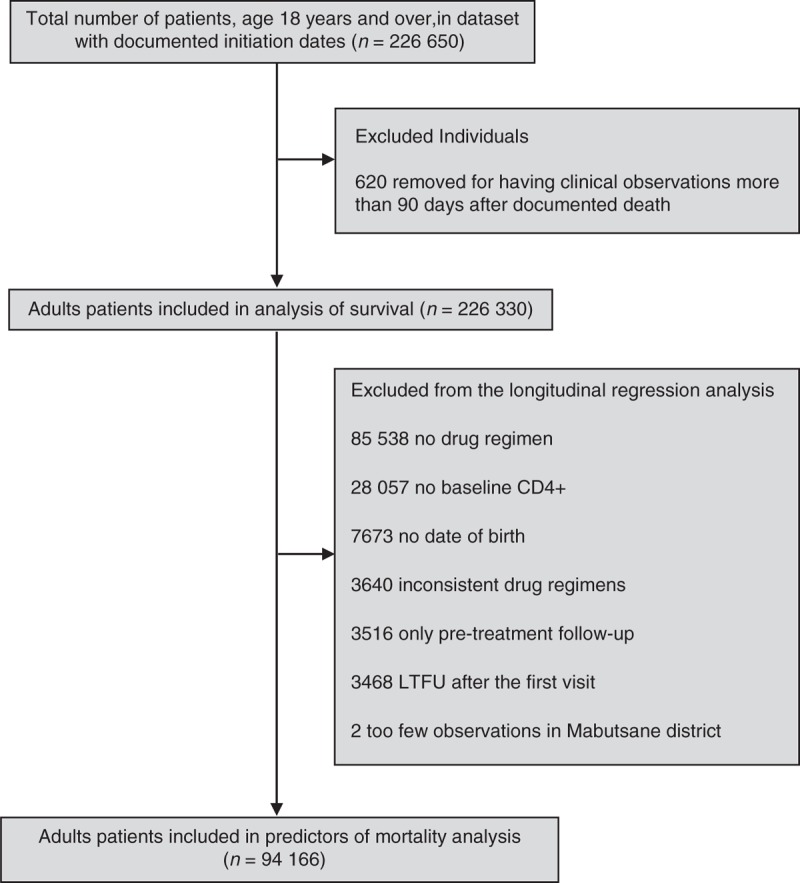

During the data cleaning process, we removed 620 individuals’ observations for having clinical records over 90 days after documented death. Because some clinics keep ART drug refill records separately to PIMS, the drug regimens from 68 facilities were not available for this analysis. The individuals without documented antiretroviral regimens or no baseline CD4+ cell counts dropped from regression models, which restricted the sample to 94 166 (see Fig. 1). Observations from 86 845 were included in a sensitivity analysis where individuals initiated in 2012 and 2013 are removed from the original model. These individuals were excluded because they might have had a different pattern of mortality and loss to follow-up (LTFU) than those who initiated earlier [6].

Fig. 1.

Description of Botswana National Antiretroviral Treatment Programme data.

The primary outcome measure for this analysis was mortality. For this analysis, ‘documented death’ referred to a death event recorded in the database. Some deaths were not reported to the Masa Programme, leading those individuals to be marked as LTFU. LTFU here is defined by no recorded clinical visits or prescription refills for 90 days after a missed clinical visit/refill. Baseline CD4+ cell counts were defined as any CD4+ cell count reported in the 90 days before treatment initiation, only if there was not a recorded baseline CD4+ cell count.

Statistical analysis

We used a person-years (P-Y) approach to analyse event rates. Follow-up time was measured from the date of ART initiation until death, or to the date of the last visit to the clinic. For the patients who did not start ART immediately after enrolment, only their post-ART follow-up time entered the analysis.

We used marginal structural modelling to estimate predictors of death among HIV patients on ART. We used this technique to address the complex issue of LTFU and prevent bias in interpreting the results [7,8]. Using observed variables, this approach allows us to derive a weight for each individual in each quarter, i.e., the inverse probability of remaining in the study in that interval [9]. Following the literature, the stabilized version of inverse probability of LTFU was estimated as a ratio of two predicted probability from two pooled logistic regression models. To correct for auto-correlation in the panel setting, we clustered the standard errors at patient level; and to deal with the clustering effect at district-level, we included dummy variable for each district in the models as fixed effect. In the model for the numerator only the baseline covariates were included, while for the denominator the logistic model was fitted with the baseline and time-varying covariates [10].

In the regression model we used all the patient-level demographic and medical variables captured for the majority of the patients in the database. The variables include age, sex, CD4+ cell count, and treatment regimen at baseline. We did not include viral load data due to poor data quality. Additionally, treatment initiation calendar year was included to capture the potential effect of guideline changes. Medication regimen at each quarter was added as the time-varying variable.

To evaluate the robustness of the findings, we performed a sensitivity analysis by removal of the observations from the last 2 years (2012 and 2013) due to low numbers of observations and documented deaths, and the potential of these patients to have different patterns of mortality and LTFU. We also restricted the model to patients who had only been on treatment for less than a year, to see how these patients may differ from the overall model results.

Results

In the database used for this analysis, the number of patients ever initiated ART in the Masa Programme increased from 3206 in 2002 to 226 030 by October 2013 [These are the numbers of enrollees in the programme whose records were captured electronically and after data cleaning to remove observations with poor data quality]. The largest increase in initiation was in 2006, after which the increasing rate of ART initiation gradually declined.

Table 1 contains descriptive statistics for the patients in the Masa programme. Of these patients, 82% had a baseline CD4+ cell count value in the database. A high percentage of the study population was female (62%), and median age at baseline was 33 for women [interquartile range (IQR) 28–40] and 38 for men (IQR 32–45).

Table 1.

Baseline patient characteristics for patientsa initiating antiretroviral treatment in the Botswana National HIV/AIDS Treatment Programme, 2002–2013.

| Continuous variables | Median | IQR | Total |

| Number of clinic visits | 5 | 2–10 | 226 030 |

| Months of follow-up | 37 | 11–75 | 202 818 |

| Age (years) | 35 | 29–42 | 214 804 |

| Baseline CD4+ | 147 | 79–200 | 185 805 |

| Indicator variables | No. of patients | % of study population | |

| Women | 138 653 | 61.8 | 224 310 |

| Year of initiation | 226 030 | ||

| 2002–2007 | 121 509 | 53.8 | |

| 2008–2013 | 104 521 | 46.2 | |

| First-line ART regimen (NNRTI or PI) | 128 450 | ||

| Nevirapine | 52 346 | 40.8 | |

| Efavirenz | 73 655 | 57.3 | |

| Lopinavir | 2449 | 1.9 | |

| First-line ART regimen (NRTI) | 128 450 | ||

| Zidovudine | 92 542 | 72.1 | |

| Stavudine | 9605 | 7.5 | |

| Tenofovir | 26 303 | 20.5 | |

| ART regimen switch | 129 946 | ||

| NRTI switch | 12 186 | 9.4 | |

| NNRTI switch | 7085 | 5.5 | |

| PI switch | 3832 | 3.0 |

ART, antiretroviral therapy; IQR, interquartile range.

aReports on the 226 030 patients included in mortality rate analysis, unless otherwise noted below the heading the number of patients with complete data for that variable.

The median baseline CD4+ cell count was 147 cells/μl (IQR 79–200). Majority of the patients (72%) have a CD4+ cell count between 50 and 250 cells/μl, whereas 15% of patients initiated with a very low baseline CD4+ cell count (<50 cells/μl). As a result of changing the CD4+ cell count threshold for ART eligibility from 200 to 250 cells/μl in 2008, 18 777 patients with CD4+ cell count between 200 and 250 cells/μl were able to start treatment earlier. Median baseline CD4+ cell count increased from 88 cells/μl (IQR 38–156) in 2002, to 258 cells/μl (IQR 147–337) in 2013.

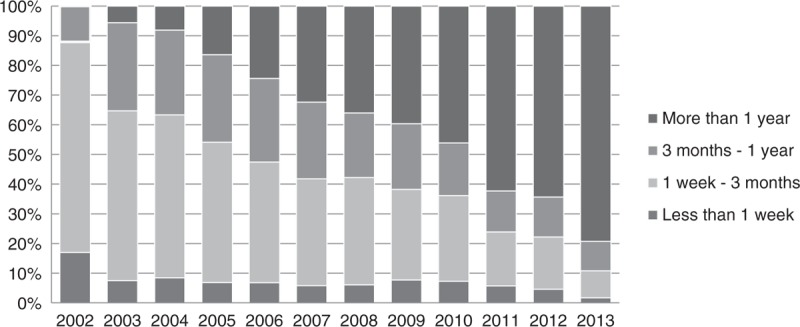

A total of 15 150 (7%) patients died during 2002–2013, of whom 9670 (64% of total deaths) died in the first year after treatment initiation, of those who died in the first year, 6261 (65% of deaths in the first year) died in the first 3 months. We found that the proportion of deaths in the first week, first 3 months, and first year of treatment have been decreasing over the 12 years of the Masa Programme (see Fig. 2). In 2002, 229 people (7%) initiating ART died in their first year of treatment, whereas in 2012, 340 people (2%) initiating ART died in their first year.

Fig. 2.

Distribution of yearly deaths by duration of treatment.

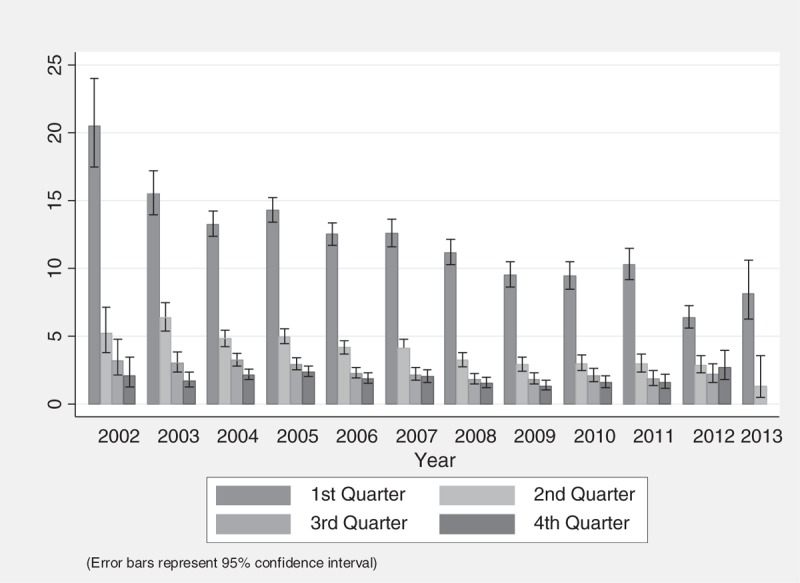

The average mortality rate was 2.06 deaths per 100 P-Y over a total follow-up time of 687 759 P-Y. Mortality rate was greatest in the first year of follow-up at 5.30 deaths per 100 P-Y [95% confidence interval (CI) 5.19–5.41] and decreased to 1.01 deaths per 100 P-Y (95% CI 0.98–1.04), after the first year on ART. Within the first year of treatment, the first 3 months shows highest mortality rate at 11.79 deaths per 100 P-Y (95% CI 11.49–12.11), but the rate decreases to 1.88 deaths per 100 P-Y (95% CI 1.75–2.03) between 9 and 12 months after treatment initiation. Moreover, the rate during the first 3 months on ART decreased over the years of the programme. The mortality rate in the first 3 months of treatment was 14.29 deaths per 100 P-Y (95% CI 13.41–15.23) in 2005 and decreases over time to 6.34 deaths per 100 P-Y (95% CI 5.57–7.22) in 2012 (see Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Mortality rate in the first year after treatment initiation.

Median follow-up time was 37 months (IQR 11–75). The median duration of follow-up for patients who were LTFU was 24 months (IQR 8–47), compared with a median of 52 months (IQR 16–89) for those who were not lost. The incidence of LTFU was 12.47 per 100 P-Y (95% CI 12.38–12.55) overall. However, LTFU rate was 14.87 per 100 P-Y (95% CI 14.68–15.05) for patients in their first year of ART treatment, with the lowest rate between 3 and 6 months [13.33 per 100 P-Y (95% CI 12.98–13.69)], and highest between 9 and 12 months [18.18 per 100 P-Y (95% CI 17.75–18.61)]. The lowest rate of LTFU by year of initiation was 7.74 per 100 P-Y (95% CI 7.52–7.97) in 2003, and the highest rate of LTFU was 22.45 per 100 P-Y (95% CI 21.75–23.18) for those initiating in 2011. Some patients who were transferred were considered LTFU, as there was not enough data to match their records across facilities. There were 51 548 patients who transferred facilities since 2002, and only 14 922 of transferred patients had their records linked.

For 128 450 patients whose first-line ART medication was available and consistent in the Masa Programme database [Some of the ART drug data was removed because of inconsistency, e.g. if the medical records indicated that a patient was on tenofovir and zidovudine at the same time.], zidovudine and tenofovir were the main nucleoside/nucleotide reverse-transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) used, with 72% of people starting with zidovudine compared with 21% on tenofovir [Following the 2008 change in the guideline, tenofovir replaced zidovudine as the first-line NRTI in Botswana.] and the remainder of patients, 7%, on stavudine. Since almost all patients who started on zidovudine also received lamivudine, and those who started on tenofovir also receive emtricitabine either separately or as a combination, Combivir and Truvada (or Atripla), respectively, we just mention zidovudine and tenofovir throughout this article. The population on non-nucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs) were split between efavirenz and nevirapine, 57 and 41%, respectively, with the remainder of patients, 2%, starting on the protease inhibitor (PI), lopinavir.

Regression analysis

Table 2 presents the results of the marginal structural model (weighted to compensate for the patients LTFU), an analysis of patients in their first year of treatment and the sensitivity analysis. Comparing three main first-line NRTI medications in Botswana National ART Programme, namely zidovudine, tenofovir and stavudine, we found that the mortality odds ratio among patients starting on zidovudine was 1.2 times that of tenofovir (95% CI 1.1–1.3). Stavudine-containing regimens were associated with 4.9 times the odds of mortality rate compared with tenofovir (95% CI 4.3–5.6). Those on efavirenz had a slightly higher rate of mortality when compared with those on nevirapine with an odds ratio (OR) of 1.12 (95% CI 1.03–1.2). The odds of mortality for those who switched NRTI or NNRTI are less, as compared with those who stayed with the original prescription.

Table 2.

Predictors of mortality regression results and sensitivity analysis.a,b,c

| Model 1: all patients | Model 2: including only patients in their first year of treatment | Model 3: excluding those initiating in 2012 and 2013 | ||||

| Adjusted OR | 95% CI | Adjusted OR | 95% CI | Adjusted OR | 95% CI | |

| Tenofovir | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Zidovudine | 1.19** | [1.06, 1.34] | 2.04*** | [1.72, 2.42] | 1.06 | [0.95, 1.20] |

| Stavudine | 4.91*** | [4.30, 5.62] | 6.47*** | [5.33, 7.86] | 4.400*** | [3.84, 5.04] |

| Nevirapine | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Efavirenz | 1.12** | [1.03, 1.20] | 0.88* | [0.79, 0.98] | 1.166*** | [1.08, 1.26] |

| Lopinavir | 0.94 | [0.73, 1.22] | 0.32*** | [0.19, 0.54] | 0.99 | [0.77, 1.29] |

| Ever switched NRTI | 0.26*** | [0.23, 0.29] | 0.15 | [0.02, 1.01] | 0.26*** | [0.23, 0.29] |

| Ever switched NNRTI | 0.58*** | [0.51, 0.66] | 1 | [1,1] | 0.57*** | [0.50, 0.66] |

| Initiation year >2008 | 0.75*** | [0.68, 0.83] | 0.63*** | [0.53, 0.73] | 0.77*** | [0.69, 0.85] |

| Female | 0.66*** | [0.62, 0.71] | 0.77*** | [0.70, 0.84] | 0.68*** | [0.64, 0.74] |

| Age >40 | 1.21*** | [1.14, 1.28] | 1.32*** | [1.22, 1.44] | 1.19*** | [1.12, 1.26] |

| Baseline CD4 <100 | 1.92*** | [1.82, 2.02] | 2.57*** | [2.38, 2.78] | 1.87*** | [1.77, 1.97] |

| Follow-up month | 0.92*** | [0.92, 0.93] | 0.95*** | [0.94, 0.96] | 0.92*** | [0.92, 0.93] |

| Sample size | 996 770 | 43 121 | 973 925 | |||

CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio. Level of statistical significance: *0.1; **0.05; ***0.001.

aModels are run with a cubic knot spline and with health district fixed effects (not reported here).

bEach variable is an indicator variable except for follow-up month, which is a continuous variable.

cModels are weighted to account for loss to follow-up.

Those who initiated ART after 2008 had lower odds of mortality compared with those who initiated before 2008. Our model predicted a lower risk of mortality for women [OR 0.64, (95% CI 0.60–0.69)], compared with men. The odds of death increased after the age of 40. Additionally, having a baseline CD4+ cell count below 100 increased the odds of death by 1.89 times (95% CI 1.79–1.99).

Model 2, including only those that have been on treatment for less than a year, shows similar results to the main model with a few key differences. The odds of mortality with zidovudine and stavudine was higher compared with tenofovir, whereas patients on efavirenz were less likely to die compared with those on nevirapine [OR 0.87 (95% CI 0.79–0.97)]. Having a baseline CD4+ cell count of less than 100 cells/μl has a stronger effect in this model than in the model containing all individuals [OR 2.56 (95% CI 2.37–2.77)]. In Model 3, only one estimate changed after removing those initiating in the last 2 years, specifically the inferiority of zidovudine became statistically insignificant.

Discussion

This study is the first comprehensive analysis of the trends and determinants of mortality for over 200 000 patients in an African National ART Programme. We found low rate of mortality and high rate of LTFU after treatment initiation, which was similar to other African cohorts [11]. The crude mortality rate was 2.06 deaths per 100 P-Y, which is lower than a Ghanaian cohort, with 2.9 deaths per 100 P-Y [12], and a Rwandan cohort with 3.7 deaths per 100 P-Y [13], and higher than a similar cohort in South Africa, with 1.08 deaths per 100 P-Y [14]. All of these estimates are substantially lower than the 16.1 deaths per 100 P-Y found in a Zambian cohort [15].

In this study, like similar studies in sub-Saharan Africa [16], more than 64% of deaths happened in the first year after treatment initiation. However, the percentage of individuals who died in their first year of treatment has been steadily decreasing over the years, from 7 to 2% of those initiating ART during 2002–2012. Our findings are similar to a study evaluating seven programmes in South Africa, where 12-month mortality decreased to 6% in 2007 from 9% in 2002 [17]. This suggests that patients are now remaining in the programme longer, and can be successfully treated, although early mortality is still a major concern.

Crude mortality rate in the first 3 months of ART initiation is at 11.8 deaths per 100 P-Y, which is significantly lower than estimates found in other studies. In a South African cohort, followed from 2007 to 2012, the crude mortality rate in the first 3 months of ART was 19.4 per 100 P-Y. The mortality rate during the first 3 months of treatment in Zambia and China was found to be 26 and 22.6 deaths per 100 P-Y respectively [15,18]. Differences in follow-up period and a significant drop in mortality rates across the 12 years of the programme may explain the differences in these estimates.

A notable outcome of the rapid scaling-up of the Botswana National ART programme from 2002 to 2013 was its success in decreasing mortality in the first 3 months after treatment initiation from more than 20 deaths per 100 P-Y in 2002, to six deaths per 100 P-Y in 2012. A similar pattern, but higher rates are found in a study in South Africa, where mortality rates in the first 3 months dropped from 21.4 per 100 P-Y (95% CI 18.3–24.8) in 2004–2005 to 9.0 per 100 P-Y (95% CI 7.3–11.0) in 2011–2012 [19]. It is likely that the high rates of LTFU in the third and fourth quarter after ART initiation in Botswana are causing us to underestimate mortality rates 6 months after ART initiation. Although this trend is often seen in similar studies in resource-limited settings, the mortality rates in Botswana remain a great deal lower, even when mortality rates are restricted to the same years of follow-up [15,18]. Diminishing rate of mortality in the first 3 months after treatment initiation in Botswana can be partially explained by higher CD4+ cell counts at treatment initiation and by replacing zidovudine with tenofovir as the first-line regimen in 2008 [20].

Some patients in our study may fulfil the definition of LTFU because they were transferred, but their medical records could not be linked due to differences in patient identifiers or differences in reporting consistency at the receiving facility. Some patients may have died without being recorded in the electronic system. Using a method to trace patients, a study of 524 patients in Botswana in early 2003 showed that more than half of the 68 patients originally deemed to be LTFU were confirmed to be dead after tracing. Therefore, many of the patients who are LTFU in our study have probably died [21].

Some of the LTFU can be explained by poor data quality. Some LTFU patients were probably still receiving care, but the facility failed to fill in the medical record electronically. Some facilities reported only demographic data and failed to report the laboratory results or prescription drug regimens of patients. Even the data reporting quality, or lack thereof, at certain facilities was not consistent, and fluctuated over time. Improving the data collection process should be a priority in the Masa Programme.

Although average retention across districts in Botswana has improved over time, many patients did not receive medical care at recommended intervals. Retention in care for those on ART is essential as they need to ensure uninterrupted receipt of ART, prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections, as well as continued clinical and laboratory monitoring to detect drug-related toxicity or treatment failure [22].

In this analysis, tenofovir was found to be associated with substantially lower rate of mortality compared with zidovudine and stavudine, which have higher rates of toxicity [23]. Our findings are in line with the results of other studies in the literature. In randomized trials, tenofovir has demonstrated comparable or greater efficacy compared with other first-line regimens, such as zidovudine and stavudine [24].

The results presented show that efavirenz was slightly inferior to nevirapine. In the sensitivity analysis, the result was reversed, which may confirm the findings of previous studies concluding there was no difference in efficacy between the two drugs [25]. Although we are not able to offer an explanation for the inferiority of efavirenz in the main model, we can stipulate that there were unmeasured confounders associated with prescription of NNRTIs in Botswana that contributed to inferior outcomes for efavirenz in this study.

Being highly immunosuppressed at the initiation of therapy, with a baseline CD4+ cell count less than 100 cells/μl, was a strong predictor of mortality, as has been shown in several similar studies [26,27]. Consistent with the literature, higher CD4+ levels in this population were positively correlated with survival.

Consistent with similar studies [15,28], individuals who were male and older individuals were more likely to die in the Masa Programme. There is a range of explanations for gender difference in mortality on ART. Given that in our regression model we accounted for the baseline CD4+ level and duration of follow-up, one probable explanation for lower mortality among women would be superior adherence to ART, which we could not control for in our model. In Botswana, like other studies in similar settings, women's better outcome can be associated with better treatment adherence and health-seeking behaviour [29–31]. Moreover, the cause of death in the database is unknown, and some of these patients may have died of non-AIDS defining conditions [32]. There is higher mortality among men in general as men are more likely to have risk factors for respiratory and cardiovascular disease, and to be involved in motor vehicle accidents, homicide, and suicide [33]. It is also important to note that older individuals are more likely to die from other causes unrelated to AIDS, e.g., cardiovascular disorders, cerebrovascular accidents, and cancer, which may contribute to higher mortality in this age. Therefore, we cannot necessarily establish a correlation between the HIV infection or treatment status and higher mortality rate among the male or older patients.

Limitations

There are limitations to this study that should be acknowledged. The main limitation is the potential for missing death data due to inconsistent reporting; however; we tried to account for this through our analysis of patients lost to follow-up, specifically in the regression model, by using marginal structural modelling to correct for bias that it may have introduced. There is also missing data for ART regimen and CD4+; however, it is less troubling as causes of missing data may include understaffing, lack of adequate training, and poor data recording due to lack of infrastructure. We could not find any evidence indicating missing data and incorrect entries may have introduced selection bias to this analysis, or have limited the generalizability of these findings, unless a correlation between documentation and quality of care is assumed. Strengths of this study include our large sample size and repeated measures over 12 years of the Masa Programme.

Conclusions

Our analysis of the Botswana National ART Programme highlights areas of success and areas needing improvement. The success of the programme can be explained, in part, by the fact that the system adjusted itself through revising the treatment guidelines, earlier identification of the patients in the course of their infection, better trained personnel and an improved health information system [5]. The programme succeeded in reducing overall as well as early mortality (12 months and 3 months after treatment initiation). Although earlier HIV diagnosis and ART initiation at higher CD4 can improve survival, the findings of this study call for interventions to target reduction in early mortality and in keeping patients engaged in care. Last but not least, the study emphasizes the critical role of high-quality, routine data collection and reporting, for epidemiological studies and day-to-day clinical practice.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Mr. Bud Bowen at the US Centers for Disease Control for his support on this project. We would also like to acknowledge the support of the Botswana Ministry of Health, specifically those at the Department of HIV/AIDS Prevention and Care, and the Department of Health Policy, Development, Monitoring and Evaluation, including the Monitoring and Evaluation Division.

Contributions: M.F. contributed to the design, planning, and implementation of the study, as well as the data management, data analysis, and the writing of the manuscript. R.M., O.N., and S.E-H., contributed to the design, planning, and implementation of the study as well as editing the manuscript. N.P. contributed to the data management and analysis, as well as aided in the writing of the manuscript. A.A., N.M., K.K., R.L., E.B.F., P.K., and T.M. contributed to the planning and implementation of this study as well as editing of the manuscript. T.C., and K.G. contributed to the collection and management of the data for this study.

Sources of support: This research has been supported by the President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention under the terms of GH000512-01.

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.UNAIDS. Report on the global HIV/AIDS epidemic. Geneva, Switzerland: Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 2.M&E Division. Ministry of Health Quarterly HAART Report Q1. Gaborone: Botswana; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bussmann H, Wester CW, Ndwapi N, Grundmann N, Gaolathe T, Puvimanasinghe J, et al. Five-year outcomes of initial patients treated in Botswana's National Antiretroviral Treatment Program. AIDS 2008; 22:2303–2311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.WHO. Case Study: Country-enhanced monitoring and evaluation for antiretroviral therapy scale-up: analysis and use of strategic information in Botswana. In: HIV/AIDS Programme Strengthening Health Services to Fight HIV/AIDS. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Farahani M, Vable A, Lebelonyane R, Seipone K, Anderson M, Avalos A, et al. Outcomes of the Botswana National HIV/AIDS Treatment Programme from 2002 to 2010: a longitudinal analysis. Lancet Glob Health 2014; 2:e44–e50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnson LF, Estill J, Keiser O, Cornell M, Moolla H, Schomaker M, et al. Do increasing rates of loss to follow-up in antiretroviral treatment programs imply deteriorating patient retention?. Am J Epidemiol 2014; 180:1208–1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hernán MA, Brumback BA, Robins JM. Estimating the causal effect of zidovudine on CD4 count with a marginal structural model for repeated measures. Stat Med 2002; 21:1689–1709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fitzmaurice GM, Laird NM, Ware JH. Applied longitudinal analysis. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cole SR, Hernán MA. Constructing inverse probability weights for marginal structural models. Am J Epidemiol 2008; 168:656–664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fewell Z, Hernán MA, Wolfe F, Tilling K, Choi H, Sterne JA. Controlling for time-dependent confounding using marginal structural models. Stata J 2004; 4:402–420. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Somi G, Keogh SC, Todd J, Kilama B, Wringe A, van den Hombergh J, et al. Low mortality risk but high loss to follow-up among patients in the Tanzanian national HIV care and treatment programme. Trop Med Int Health 2012; 17:497–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sarfo FS, Sarfo MA, Norman B, Phillips R, Bedu-Addo G, Chadwick D. Risk of deaths, AIDS-defining and non-AIDS defining events among Ghanaians on long-term combination antiretroviral therapy. PLoS ONE 2014; 9:e111400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lowrance DW, Ndamage F, Kayirangwa E, Ndagije F, Lo W, Hoover DR, et al. Adult clinical and immunologic outcomes of the national antiretroviral treatment program in Rwanda during 2004-2005. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2009; 52:49–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mee P, Collinson MA, Madhavan S, Kabudula C, Gómez-Olivé FX, Kahn K, et al. Determinants of the risk of dying of HIV/AIDS in a rural South African community over the period of the decentralised roll-out of antiretroviral therapy: a longitudinal study. Glob Health Action 2014; 7:24826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stringer JS, Zulu I, Levy J, Stringer EM, Mwango A, Chi BH, et al. Rapid scale-up of antiretroviral therapy at primary care sites in Zambia: feasibility and early outcomes. J Am Med Assoc 2006; 296:782–793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gupta A, Nadkarni G, Yang W-T, Chandrasekhar A, Gupte N, Bisson GP, et al. Early mortality in adults initiating antiretroviral therapy (ART) in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC): a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2011; 6:e28691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cornell M, Grimsrud A, Fairall L, Fox MP, van Cutsem G, Giddy J, et al. Temporal changes in programme outcomes among adult patients initiating antiretroviral therapy across South Africa, 2002-2007. AIDS 2010; 24:2263–2270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang F, Dou Z, Ma Y, Zhao Y, Liu Z, Bulterys M, et al. Five-year outcomes of the China National Free Antiretroviral Treatment Program. Ann Intern Med 2009; 151:241–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lessells RJ, Mutevedzi PC, Iwuji CC, Newell M-L. Reduction in early mortality on antiretroviral therapy for adults in rural South Africa since change in CD4+ cell count eligibility criteria. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2014; 65:e17–e24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gallant JE, DeJesus E, Arribas JR, Pozniak AL, Gazzard B, Campo RE, et al. Tenofovir DF, emtricitabine, and efavirenz vs. zidovudine, lamivudine, and efavirenz for HIV. N Engl J Med 2006; 354:251–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bisson GP, Gaolathe T, Gross R, Rollins C, Bellamy S, Mogorosi M, et al. Overestimates of survival after HAART: implications for global scale-up efforts. PLoS ONE 2008; 3:e1725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Govindasamy D, Kranzer K, Ford N. Strengthening the HIV cascade to ensure an effective future ART response in sub-Saharan Africa. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 2014; 108:1–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mercier S, Gueye NFN, Cournil A, Fontbonne A, Copin N, Ndiaye I, et al. Lipodystrophy and metabolic disorders in HIV-1-infected adults on 4- to 9-year antiretroviral therapy in Senegal: a case-control study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2009; 52:224–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gallant JE, DeJesus E, Arribas JR, Pozniak AL, Gazzard B, Campo RE, et al. Tenofovir DF, emtricitabine, and efavirenz vs. zidovudine, lamivudine, and efavirenz for HIV. N Engl J Med 2006; 354:251–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mbuagbaw LC, Irlam JH. Efavirenz versus nevirapine as a nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor in initial combination antiretroviral therapy for HIV infection. Cochrane Libr 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Braitstein P, Brinkhof MW, Dabis F, Schechter M, Boulle A, Miotti P, et al. Mortality of HIV-1-infected patients in the first year of antiretroviral therapy: comparison between low-income and high-income countries. Lancet 2006; 367:817–824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fox MP, Rosen S. Patient retention in antiretroviral therapy programs up to three years on treatment in sub-Saharan Africa, 2007-2009: systematic review. Trop Med Int Health 2010; 15:1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ferradini L, Jeannin A, Pinoges L, Izopet J, Odhiambo D, Mankhambo L, et al. Scaling up of highly active antiretroviral therapy in a rural district of Malawi: an effectiveness assessment. Lancet 2006; 367:1335–1342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen SCC, Yu JKL, Harries AD, Bong CN, Kolola-Dzimadzi R, Tok TS, et al. Increased mortality of male adults with AIDS related to poor compliance to antiretroviral therapy in Malawi. Trop Med Int Health 2008; 13:513–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dou Z, Xu J, Jiao JH, Ma Y, Durako S, Yu L, et al. Gender difference in 2-year mortality and immunological response to ART in an HIV-infected Chinese population, 2006-2008. PLoS ONE 2011; 6:e22707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Druyts E, Dybul M, Kanters S, Nachega J, Birungi J, Ford N, et al. Male sex and the risk of mortality among individuals enrolled in antiretroviral therapy programs in Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS 2013; 27:417–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith CJ, Ryom L, Weber R, Morlat P, Pradier C, Reiss P, et al. Trends in underlying causes of death in people with HIV from 1999 to 2011 (D: A: D): a multicohort collaboration. Lancet 2014; 384:241–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Owens IPF. Sex differences in mortality rate. Science 2002; 297:2008–2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]