Abstract

Flaviviruses comprise approximately 70 closely related RNA viruses. These include several mosquito-borne pathogens, such as yellow fever virus (YFV), dengue virus (DENV), and Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV), which can cause significant human diseases and thus are of great medical importance. Vaccines against both YFV and JEV have been used successfully in humans for decades; however, the development of a DENV vaccine has encountered considerable obstacles. Here, we review the protective immune responses elicited by the vaccine against YFV to provide some insights into the development of a protective DENV vaccine.

Keywords: dengue virus, protective immunity, vaccine, yellow fever

Introduction

Flaviviruses belong to the family Flaviviridae, which includes mosquito-borne pathogens such as yellow fever virus (YFV), Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV), dengue virus (DENV), and West Nile virus (WNV). Flaviviruses can cause human diseases and thus are considered medically important. According to WHO statistics, approximately 200,000 cases of YF occur annually, leading to 30,000 deaths worldwide.1,2 Although 3 billion people are at risk of JEV infection, only 20,000 clinical cases and 6,000 deaths occur annually. However, the case fatality rate of JEV infection ranges from 5 to 30%, and approximately 30–50% of patients who recover from the infection have permanent neuropsychiatric sequelae, while only one-third of patients have complete remission without lingering complications.3 Human cases of WNV infection are relatively rare, and the most recent cases have largely been reported in the USA. DENV infection has dramatically increased since the Second World War, and 2.5 billion people in more than 100 countries across the tropical and subtropical regions are currently at risk for DENV infection. An estimated 390 million dengue infections occur every year, of which 96 million manifest clinically as dengue fever.4,5

Flaviviruses are transmitted by arthropod vectors, principally represented by the Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus mosquitoes. The mosquito becomes infected when it feeds on blood from a viremic patient and is capable of delivering viruses to its offspring, thereby amplifying the number of carriers of infection.6,7 Because international travel has become more frequent, infected vectors can be transported much more easily from an endemic region to other areas of the world, rendering vector-borne diseases such as dengue fever a global health problem. The use of vaccines to prevent viral infection is the most cost-effective public health strategy. Vaccines against YFV (the YF-17D vaccine) and JEV have been effectively used in humans for decades. However, a licensed DENV vaccine has not been successfully developed using similar strategies. Because the DENV vaccine that is in the most advanced stage of clinical development is based on a chimera between YF-17D and DENV components, we closely examine the immunological factors that have been associated with the protection conferred by the YF-17D vaccine in the hopes of elucidating a strategy for the development of an efficacious DENV vaccine.

Structure and Replication Strategy of Flaviviruses

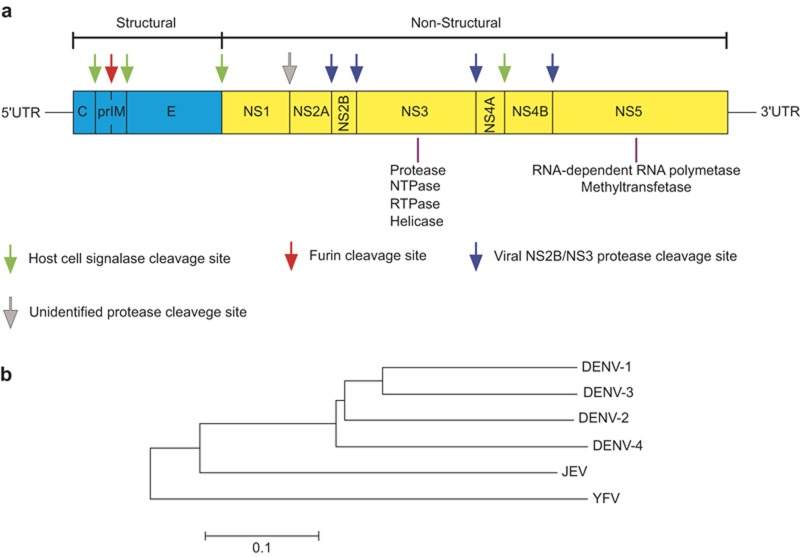

All flaviviruses share similar structural features and replication strategies (Figure 1). The mature virion consists of an icosahedral particle comprising three structural proteins: the capsid protein (C), the membrane protein (M), and the envelope protein (E). The viral genome is composed of an approximately 11,000-nucleotide single-stranded, positive-sense RNA (ssRNA). This ssRNA encodes the three structural proteins and seven non-structural (NS) proteins in a single open-reading frame that is flanked by untranslated regions (UTRs) at either end, forming the gene order 5′UTR-C-prM-E-NS1-NS2A-NS2B-NS3-NS4A-NS4B-NS5-3′UTR.8,9

Figure 1.

Structure of the flavivirus genome and genetic distance of selected flaviviruses. (a). Genomic structure and polyprotein processing of flaviviruses. The positive-sense RNA genome forms a single open-reading frame that is translated into a polyprotein precursor containing three structural proteins (blue) and seven NS proteins (yellow) flanked by the 5′ and 3′ UTRs. Cleavage sites for the host-cell signalase and furin, and the viral NS2B/NS3 protease as well as an unidentified protease are indicated by arrows. The functions of the NS3 and NS5 proteins that are required for RNA replication and polyprotein processing are also shown. (b). Phylogenetic analysis of selected flaviviruses. A neighbor-joining tree was compiled with complete genome sequences of DENV, JEV, and YFV available in the GenBank database using a Kimura two-parameter model. Sequence alignment and phylogenetic analysis were performed with MEGA 6 software(Oxford, UK) Virus sequences included are DENV-1 Hawaii, DENV-2 16681, DENV-3 H87, DENV-4 H241, JEV JaOArS982, and YFV ASIBI.

DENV infection is initiated by viral attachment to the receptors on target cells, followed principally by clathrin-mediated endocytosis or other less predominant modes of entry. The virus E protein dimers undergo a conformational change with the gradual acidification of the endosome to expose the fusion loop, leading to fusion between the viral and endosomal membranes.10,11 Then, the uncoated viral ssRNA is released into the cytoplasm and translated into a polyprotein that is subsequently cleaved by virus-encoded or host-cell proteases into three structural proteins (C, prM, and E) and seven NS proteins (NS1, NS2A, NS2B, NS3, NS4A, NS4B, and NS5).12 Viral genomic RNA synthesis is based on a double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) template in the viral replication complex, which is located within virus-induced membrane structures originating from the trans-Golgi network or the intermediate compartment.13 Most viral NS proteins and the core protein are involved in the replication process.14,15,16,17,18 Flavivirus virions assemble at the intracellular membranes of infected cells.19 The viral C protein and ssRNA form a nucleocapsid structure, probably in association with the membranes of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). Then, the prM and E proteins are transferred into the lumen of the ER to form a heterotrimeric prM/E complex that surrounds the nucleocapsid. The prM protein is further cleaved into the pr and M proteins by the furin protease during a pH-dependent virion maturation process.

The mechanism by which the immune response confers protection against the virus is likely to involve the targeting of a specific structural component or a particular step of viral replication. Elucidating how successful vaccines have worked in the past will provide a useful guide for vaccine research and development in the future. The YFV-17D vaccine for yellow fever is an ideal example of a successful vaccine that can serve as a gold-standard to determine the immune correlates of vaccine-induced protection.

Yellow Fever and Yellow Fever Vaccines

YFV is the prototype member of the flavivirus genus and is the source of the genus name. YFV rampantly attacked the world population (especially in Africa, America, and Europe) for over 200 years until the French neurotropic vaccine (FNV) and yellow fever 17D vaccine (YF-17D) were developed in the 1930s. Although highly efficacious, the use of FNV was stopped in 1981 due to its association with an increased risk of post-vaccination encephalitis (Table 1).20 The YF-17D vaccine was developed by successive passages of the Asibi strain of YFV in mouse embryo tissue culture, chicken embryo tissue culture, and then chicken embryo tissue culture without nerve tissue for several hundred generations. With great efficacy and fewer side effects,21,22 the YF-17D vaccine is considered to be the most successful human vaccine ever produced. Achieving more than 90% efficacy, the YF-17D vaccine has been administered to more than 600 million people worldwide23,24 and thus provides an excellent model for the determination of immune correlates of protection against flaviviruses.

Table 1. Comparison between FNV and yellow fever-17D (YF-17D) vaccinea.

| FNV | YF-17D vaccine | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Origin | French viscerotropic virus strain | Asibi strain | |

| Attenuation | ∼128 times in mouse brain | ∼17 times in mouse embryo tissue∼58 times in chick embryo tissue∼128 times in chick embryo tissue without nerve tissue | |

| Inoculation | Scarification | Subcutaneous inoculation | |

| Side effects | Post-vaccination encephalitis | YEL-AVD and YEL-ANDb | |

| Efficacy | ∼90%c | >90% | |

| Amino acid differences | DI & DII | 52G, 54V, 56A, 84K, 142R, 153K, 170A, 173T, 200K, 249D | 52R, 54A, 56V, 84E, 142Q, 153N, 170V, 173I, 200T, 249N |

| DIII | 305S, 325P, 380T | 305F, 325S, 380R | |

Because it is a live-attenuated vaccine that infects and replicates in target cells, vaccines who receive the YF-17D vaccine usually develop detectable viremia after vaccination.25,26 When the level of viremia is too high and persists for too long, unwanted adverse events may occur. In contrast, when viremia is absent the viral replication may be too limited to produce sufficient antigens to stimulate the magnitude of immune response required for protection. Thus, an appropriate level of viremia is crucial to activate multiple types of immune responses after immunization. Table 2 summarizes the kinetics of the various types of immune responses induced by the YD-17D vaccine. The following sections include a more detailed description of these responses.

Table 2. Kinetics of immune responses elicited by YF-17D vaccination in human volunteers.

| Immune response type | Day | Month | Year | References | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4–6 | 7 | 8–13 | 14–16 | 17–30 | ||||||

| Innate immunity | NK | IFN-γ+ | ↑ | 41 | |||||||||

| IL-4+ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | 41 | |||||||||

| CD56+CD69+ | + | + | + | + | ↑↑↑ | + | + | 40 | |||||

| CD56+CD16+ | + | + | + | + | ↑↑↑ | + | + | 40 | |||||

| Monocyte | TNF-α+ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | 41,43,44 | ||||||||

| IL-10+ | ↑ | ↑ | 41,43 | ||||||||||

| pDC | ↑ | 34,38 | |||||||||||

| Adaptive immunity | CD8+ T | IFN-γ+ | + | + | ↑↑↑ | + | 18 | 26,45,49, 50 | |||||

| CD4+ T | IL-2+ | + | + | + | + | + | ↑↑↑ | + | 5 | 34,54,55 | |||

| TNF-α+ | + | + | + | + | ↑↑↑ | + | + | 34,54,55 | |||||

| IFN-γ+ | + | + | + | + | + | ↑↑↑ | + | 34,54,55 | |||||

| IL-4+ | + | + | + | + | + | ↑↑↑ | + | 34,54,55 | |||||

| nAbs | IgM | + | + | ↑↑↑ | + | 4 | 74,75 | ||||||

| IgG | + | + | + | + | Up to 35 | 59,64,69 | |||||||

| Viremia | + | + | ↑↑↑ | + | + | 25,49 | |||||||

+, Detected; ↑, up-regulated; ↓, down-regulated; ↑↑↑, peak titer.

nAbs, neutralizing antibodies

Innate immune responses

The innate immune response plays a pivotal role in protecting against pathogen invasion and shaping the adaptive immune response in vivo. Inoculation with the YF-17D vaccine can delay the onset of dengue fever when a subject is subsequently infected by the DENV within a short window after vaccination,27 suggesting that innate immunity or cross-reactive immunity is involved. Those who do not seroconvert after vaccination show a lack of an innate immunity-mediated pro-inflammatory response and an increase in adaptive immune regulatory responses compared with seroconverters.28 Thus, the induction of a potent innate immune response by the YF-17D vaccine is a key element in the protection against a subsequent viral infection, and an innate response could shape the rapidity and durability of the adaptive immune responses.

Dendritic cell activation

Dendritic cells (DCs) are professional antigen-presenting cells (APCs) that are equipped with many pathogen recognition receptors (PRRs), including toll-like receptors (TLRs). They are known to regulate the strength and quality of adaptive immune responses.29,30,31 YF-17D activates DCs through TLR2, -7, -8, and -9 via adaptor molecules, such as the myeloid differentiation primary response factor 88 (MyD88) and the toll-interleukin 1 receptor domain-containing adaptor protein. In vaccine recipients, the percentages of CD86+ myeloid DCs and CD86+ plasmacytoid DCs significantly increase during the first 7 days after inoculation with YF-17D.32 In experimental models, YF-17D can infect human monocyte-derived DCs, leading to apoptosis of immature DCs. In contrast, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α-induced maturation protects the DCs from YF-17D-induced cytopathogenicity and enables them to present antigens to activate T cells of both the Th1 and Th2 subtypes.33,34,35,36,37 When co-cultured with YF-17D in vitro, human blood plasmacytoid DCs produce high levels of interferon (IFN)-α,34 a cytokine that can activate other immune cells (i.e., natural killer (NK) cells, Th1 cells, and CD8+ T cells). Myeloid DCs incubated with either live or ultraviolet-inactivated YF-17D showed increased secretion of interleukin (IL)-1β, which had the ability to regulate T helper cell activation, B cell proliferation, and immunoglobulin (Ig) production.38

NK cell responses

Through the activation of TLRs, YF-17D can elicit robust NK cell responses and upregulate their cytolytic activity.39 After vaccination, NK cells exhibit increased expression of TLR3 and TLR9, the activation markers CD69 and HLA-DR, and the cytotoxicity-associated markers CD38 and CD16. Moreover, there is a positive correlation between the expression level of CD69 and TLR3 or TLR9.40 A kinetic study in vaccinated individuals showed that IFN-γ+ NK cells significantly increased at day 7, whereas IL-4+ NK cells decreased at days 7, 15, and 30.41 Furthermore, many NK cell-associated genes, such as GNLY, GZMB, KIR2DL3, KIR2DL4, and PRF1, were upregulated on day 7 post-vaccination.38 These data suggest that the YF-17D vaccine stimulates a wide range of NK cell functions.

Monocyte/macrophage responses

Monocytes/macrophages are considered to be effector cells against pathogen invasion in addition to being professional APCs. Both human monocytes and macrophage-like cells can support the replication of either virulent or attenuated strains of YFV.42 After YF-17D vaccination, an increased frequency of macrophage-like cells, activated monocytes, pro-inflammatory monocytes, and elevated TNF-α production on day 7 coincide with a concomitant increase in the percentage of TNF-α+monocytes.43,44 Moreover, the expression levels of Fcγ-Rs, CD16, CD32, and CD64 on monocytes/macrophages are significantly increased on day 7, suggesting the activation of a myriad of Fcγ-R-mediated responses, including phagocytosis, antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity, and cytokine production.43 The percentage of IL-10+ monocytes is elevated on day 15 post-vaccination, thereby resulting in a reduction in the immune responses and the avoidance of immune pathology.41,43

T cell immune responses

Cellular immune responses are an essential arm of adaptive immunity. In YF-17D vaccine recipients, DCs present epitopes to CD4+ and CD8+ T cells to enable their immune functions.33 Most effector T cells undergo apoptosis after the clearance of the YF-17D virus, and only a small proportion of them differentiate into viral NS4B protein-specific poly-functional memory T cells that provide long-term protection against viral infection.45

CD8+ T cells can eliminate infected cells directly or inhibit viral replication by secreting antiviral cytokines. After YF-17D vaccination, transient viremia can be detected between days 3 and 14, with a peak at day 7. In association with the transient viremia, CD8+ T cells can be detected as early as day 7 and gradually peak at day 15.26 Many CD8+ T cell epitopes have been mapped on the E protein and all of the NS proteins (NS1, NS2a, NS2b, NS3, NS4a, NS4b, and NS5) in vaccines with divergent HLA types who received YF-17D.46 Some epitopes are preferentially associated with specific HLA types: HLA-B35-restricted cytotoxic T lymphocyte epitopes are mainly found on the NS1, NS2b, NS3, and E proteins, whereas a dominant HLA-A2-restricted epitope is found on the NS4b protein.45,47 Although other epitopes are more promiscuous (epitopes that bind to more than one HLA allelic variant),46 once induced the memory T cell responses appear to be long-lived. In one study, YFV peptide-specific T cells appeared as early as day 14 and were maintained for up to 18 months after vaccination47; in another study, peptide-specific responses were still detectable 54 months after vaccination.48 YF-17D is capable of activating multiple CD8+ T cell subsets and endowing them with poly-functionality. CD8+ T cell proliferation was detected between days 7 and 30 after vaccination, with a peak at day 15. An examination of the kinetics of IFN-γ production demonstrated that production started at day 7, peaked at day 15, and declined after day 30.49 Accompanying the decline in CD8+ T cell numbers, CD45RA-CCR7-PD-1+CD27high YFV-specific effector cells transitioned into CD45RA+CCR7-PD-1-CD27low memory T cells.50 Most of these memory CD8+ T cells are poly-functional with the capacity to secrete IFN-γ, macrophage inflammatory protein-β, TNF-α, and IL-2 and have great proliferative potential after re-stimulation with antigens.45 Thus, the YF-17D vaccine elicits CD8+ T cells that have poly-functionality, a potent proliferative capacity and long-lived memory phenotypes that may serve as important biomarkers for protection. A recent study in a murine model of YF-17D infection showed that although CD8+ T cell responses were dispensable for long-term survival after vaccination with YF-17D in vivo, they contributed to the control of the virus in the central nervous system in the presence or absence of YF-specific antibodies.51 Furthermore, CD8+ T cells have been demonstrated to play a pivotal role in short-term protection against heterogeneous serotypes of DENV re-infection in mice.52

CD4+ T cells proliferate markedly on day 10 after YF-17D vaccination, which is earlier than the peak of CD8+ T cell responses.26,50 These kinetics are in accord with the knowledge that CD4+ T cells are necessary to provide help for the activation of CD8+ T cells. In humans,YF-17D vaccination elicits antigen-specific CD4+ T cell responses of both the Th1 and Th2 types,38,53 as manifested by the secretion of IL-2, IFN-γ, TNF-α, or IL-4.54 These poly-functional CD4+ T cells are detectable as early as day 2, followed by a significant increase between days 10 and 14.54 Once induced, YFV-specific memory CD4+ T cells can persist for 5 years, during which time in vitro activation can lead to significant production of IFN-γ and reduced secretion of IL-5, IL-10, and IL-13.55 These properties of CD4+ T cells may be important for providing help to CD8+ T cells and antibody-producing B cells and offer an explanation as to why multifunctional CD4+ T cells are correlated with vaccine-mediated protection against YFV infection.56

Humoral immune responses

In some studies, as many as 98% of YF-17D vaccine recipients are fully protected against YFV infection.57 Humoral immune responses elicited by the vaccine are thought to be a major correlate of protection in vivo. Although the distinct immunological milieu may affect the immune responses elicited by YF-17D,58 a single inoculation of the vaccine can induce viral-specific neutralizing antibodies that persist for as long as 35 years in some vaccinees,59 offering an explanation for its long-term efficacy. Some specific attributes of the viral-specific antibody response are discussed below.

Neutralizing antibody titer

Mice and monkeys can be protected by passive immunization with monoclonal antibodies to YF-17D.60,62,62 The level of neutralizing antibodies is usually measured either by the log neutralization index (LNI), in which the potential of a sera to neutralize virus infectivity is evaluated using a constant serum concentration and increasing amounts of challenge virus, or by a more conventional plaque-reduction neutralization test (PRNT) assay.63 In animal models, an LNI>0.7 is associated with protection against challenge with a virulent virus. In comparison, human subjects can develop a mean LNI of 2.2 after vaccination,64 which is a level of neutralization activity that is approximately 30-fold higher than the level needed for protection.63 In experimental models, animals have been shown to be completely protected from YFV challenge after transference of immune serum with a neutralizing antibody PRNT50 titer≥40.65 In YF-17D-vaccinated humans, nearly 100% of subjects seroconvert 21 days after vaccination,66 and their PRNT50 titers are on average above 100.67,68,69 Moreover, neutralizing antibody titers after YF-17D vaccination can be maintained for more than 40 years.25,59,70,71,72,73 When individuals are revaccinated many years later, the neutralizing antibody titer increases rapidly and markedly,25 suggesting that memory B cell responses are long-lasting.

Protective antibody classes and targeted epitopes

After YF-17D immunization, antigen-specific IgM antibody is first detected on day 8 and then gradually increases to a peak level on day 14.74 Despite subsequent waning, measurable IgM antibodies are still present 3–4 years after vaccination in some individuals.74,75 In comparison, YF-17D-specific IgG antibodies first appear between days 10 and 17 post-vaccination. Importantly, mice can survive experimental YFV infection after passive immunization with humanized IgG.62 Many studies have been conducted to identify target antigens for these antibody responses.

The E protein of flaviviruses, which is comprised of three domains (DI, DII, and DIII), is the dominant target for neutralizing antibodies.76,77 DIII is an immunoglobulin-like domain that mediates virus attachment. DII is a finger-like domain containing a fusion loop that is essential for viralentry into target cells. DI connects DII and DIII and undergoes a conformational change during viral infection to expose the DII fusion loop. While all three domains can elicit neutralizing antibodies, DIII is considered to be the most important domain that elicits broadly neutralizing antibodies during WNV and DENV infection.78,79,80 However, a recent study showed that the long-lived antibodies in human serum mainly target DI and DII after YF-17D vaccination.81 Therefore, the domain that elicits protective antibodies has yet to be determined.

Other proteins may also be targeted by antibodies. Studies in mice and monkeys have shown that active immunization with NS1 or passive immunization with anti-NS1 antibodies can confer protection against YFV challenge.61,82 Although NS1 is not exposed on the virion surface, it can be present on the membrane of infected cells. Thus, antibodies to NS1 could bring complement to target cells, resulting in their lysis.83 In principle, antibody-mediated protection against flaviviruses can be classified into five functional categories: (i) the direct blocking of receptor binding, (ii) the inhibition of viral fusion, (iii) Fc-γ-receptor-dependent viral clearance, (iv) activation of complement-mediated lysis of the virus or virally infected cells, and (v) mediating antibody-dependent cytotoxicity of infected cells.84 The literature has shown that antibodies elicited by YF-17D cover all of the above five categories, offering an explanation for why YF-17D is such a highly efficacious vaccine.

The Development of a Vaccine against DENV

Despite the successful development of live-attenuated YFV vaccines many decades ago, similar strategies have not yielded a licensed vaccine for DENV. A careful examination of what is and is not known regarding immune responses to DENV infection and a comparison of these points with the knowledge of YF infection and YF-17D vaccine-elicited protection may help to create a strategy for the development of a dengue vaccine.

DENV can principally be divided into four serotypes based on the results of neutralization and complement fixation assays.85 Although these four serotypes of the DENV all belong to the same flavivirus family, they share only approximately 67% homology at the whole genome level and differ by up to 37% in their E protein amino acid sequences.76 To complicate the field further, a fifth DENV serotype was identified in October 2013 during the screening of samples taken from a 37-year-old farmer during a dengue outbreak in the Sarawak state of Malaysia in 2007. Researchers sequenced its whole genome and discovered that the virus was phylogenetically distinct from all known DENV serotypes. Furthermore, studies on monkeys revealed that the new virus induced antibody responses that were significantly different from those induced by the other four known DENV serotypes.86 However, more data are needed and the same observation should be validated by others to confirm that this newly identified virus is indeed a fifth DENV serotype rather than a variant of one of the four existing DENV serotypes.

Patients who are sequentially infected by different serotypes of DENVs are more likely to manifest severe dengue symptoms, including dengue hemorrhagic fever (DHF) or dengue shock syndrome (DSS).12 The exact reason for this phenomenon is not currently clear, but the most acknowledged explanation is a mechanism termed antibody-dependent enhancement (ADE). ADE states that viral infection can be augmented rather than neutralized in the presence of pre-existing non-neutralizing antibodies.87,88 Specifically, antibodies with a low affinity or those with a high affinity at a sub-neutralizing concentration can form immune complexes with the viruses. These immune complexes facilitate viral entry and subsequent replication through the interaction between the Fc region of the antibody-virus immune complexes and Fcγ receptors on the surface of target cells.87,89 Based on the ADE theory, it is widely recognized that an effective dengue vaccine needs to be tetravalent. This requirement alone increases the difficulty of developing a dengue vaccine, because it is hard to predict how to design a vaccine combination that is capable of eliciting a balanced tetravalent antibody response against all four dengue serotypes.

Current status of dengue vaccine development

Although no licensed dengue vaccine currently exists, a number of concepts have been tested in preclinical studies and some vaccines have been advanced to human clinical trials.90,91,92 Those that have entered into clinical studies are highlighted below.

A tetravalent recombinant live-attenuated dengue vaccine (DENVax) has been tested in phase I clinical trials in flavivirus-naive healthy adults in Colombia and the USA. Each component of this vaccine is a chimeric virus containing the prM and E genes of DENV-1, DENV-3, and DENV-4 in a common virus backbone (an attenuated dengue vaccine strain DENV-2 PDK-5393). The results showed that the vaccine was safe, generally well-tolerated, and immunogenic.90,94 In subjects tested in the USA, the overall seroconversion rates and geometric mean titers at day 120 after two doses of the vaccine were highest for DENV-2 (92.1% and a PRNT50 of 292.8), followed by DENV-1 and DENV-3 and were lowest for DENV-4 (71.1% and a PRNT50 titer of 15.0). Further development of this vaccine is needed to induce a more balanced immune response among all four DENV serotypes.

In another live-attenuated tetravalent dengue vaccine (LATV), each component was attenuated either by deletion mutations in the 3′ UTR or chimerization.95,96 Recent phase I clinical trials showed that a single dose of the admixture containing an enhanced DENV-2 component (TV005) elicited relatively balanced immune responses, with seroconversion for all four DENV serotypes in 90% of vaccinated subjects 90 days after vaccination.97 Further efficacy trials are planned in dengue-endemic settings with both flavivirus-naive and flavivirus-immunized individuals to determine the duration of the humoral immune responses and the significance of the cellular immune responses.

Another live-attenuated vaccine has been developed by the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research. This vaccine is composed of four serially-passaged DENV viruses, including one from each of the four dengue serotypes. These viruses were initially passaged many times in the PDK cell line and finally grown in FRhL cells to further reduce their pathogenicity.98,99,100 In phase II clinical trials, neutralizing antibodies against all four serotypes of DENV were detected in 97.1% of vaccines 3 months after vaccination.101 A phase III efficacy trial has not yet been conducted with this vaccine formulation.

The most advanced DENV vaccine has been tested in phase II and III clinical trials by the Sanofi Pasteur Company.102 This vaccine was a live-attenuated chimeric vaccine that was produced by swapping the DENV prM and E genes with the YFV genes on the YF-17D backbone.103,104 Although the tetravalent vaccine elicited neutralizing antibodies to each serotype of DENV, its protection efficacy was not ideal. While the efficacy against DENV-3 and DENV-4 reached 78.4 and 75.3%, respectively, this vaccine formulation showed low efficacy against the two most prevalent serotypes of DENV in the Asian endemic region where these vaccine trials were performed, with only 50 and 35% protection against DENV-1 and DENV-2, respectively.102,105 Similar effects with 50.3% serotype-specific vaccine efficacy for serotype 1, 42.3% for serotype 2, 70.4% for serotype 3, and 77.7% for serotype 4 were found in Latin American countries in phase III trials.106 These results call for a re-examination of issues that might have been overlooked in relation to dengue-specific protective mechanisms and strategies for future dengue vaccine development.

Lessons learned from the chimeric YF-17D/dengue vaccine efficacy trials

Innate immunity

In laboratory settings, the tetravalent ChimeriVaxTM-Dengue vaccine (TDV) can infect and activate human immature myeloid DCs and upregulate their expression of HLA-DR, CD80, CD86, and CD83 in vitro.107 However, in phase I clinical trials, vaccines did not show significant secretion of IFN-α, IL-1β, IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, or IL-12 2 weeks after vaccination,108 suggesting that only limited innate immune responses were activated in vivo. This finding would explain why only limited protection was achieved after TDV vaccination. Thus, future vaccine studies may need to include a measurement of the activation of innate immunity to screen for vaccine candidates that are likely to be efficacious.

T cell responses

Whether T cell responses cause pathogenesis or confer protection during DENV infection remains controversial.109,110 Because only limited protection against DENV-2 was afforded to vaccines despite the detection of high titers of neutralizing antibodies,105 it is reasonable to hypothesize that T cell responses play a role in the protection against heterologous serotypes in vaccine recipients.111 It should be noted that long-lived poly-functional memory T cell responses were detected in YF-17D-vaccinated individuals, and these responses might be associated with its excellent protective efficacy.

The dengue NS3 and NS5 proteins contain a number of CD8+ T cell epitopes, while the E, C, and NS1 proteins elicit mostly CD4+ T cell responses and B cell responses.112 The current chimeric dengue vaccine (TDV) does not include the dengue C, NS1, NS3, or NS5 proteins and thus may elicit a limited diversity of CD8+ and CD4+ T cell responses. In earlier human studies, TDV did not elicit either Th2 responses (IL-4, IL-5, and IL-10 production) or significant Th1 responses (IFN-γ secretion).108 The limited CD4+ T cell responses (and in particular the lack of a detectable Th2 response) may restrict the induction of B cell responses in vaccines. A lack of dengue NS3 and NS5 epitopes would prevent TDV from inducing strong CD8+ T cell responses in vaccines.

Although epitopes on the YF-17D backbone can activate both CD8+ and CD4+ T cells in humans,33 whether these T cells affect the efficacy of the chimeric YF/dengue vaccine is not known. In comparison with the potent YFV-specific T cell response induced by the YF-17D vaccine, the TDV stimulated only a narrow range of dengue-specific CD4+ T cell responses and few CD8+ T cell responses, which was another possible reason for its limited efficacy.

B cell responses

ADE is thought to play a key role in dengue pathogenesis. Therefore, the protective or enhancing properties of the antibodies elicited by vaccines should be tested. To date, only neutralizing antibody levels (PRNT50) have been determined in some TDV vaccine recipients using Vero cells, which do not express Fcγ receptors.113,114,115,116 An ADE assay should probably also be included in the evaluation of future dengue vaccines.

An inadequate range of neutralizing antibody responses against all four serotypes of DENV may be another contributing factor to the unsatisfactory efficacy of the TDV vaccine. Due to the possibility of ADE, ideally a tetravalent vaccine that induces balanced antibody responses to all four dengue serotypes in all individuals should be developed. In early clinical studies, individual chimeric YF/dengue vaccines did not induce 100% seroconversion in vaccines113,116; in a phase IIb clinical trial, the seropositivity rate was approximately 80% for each dengue serotype,105 and a smaller proportion (approximately 50%) developed antibodies to all dengue serotypes.116,117

The dengue NS1 protein can elicit antibodies to activate the complement cascade. Early experiments showed that some NS1-immunized mice were protected against lethal DENV encephalitis.118,119 Nevertheless, it has also been reported that plasma levels of NS1 and the terminal SC5b-9 complement complex were correlated with the severity of the disease in patients.120 Thus, the exact role of the dengue NS1-specific antibody in immune protection needs to be investigated.118,119,120 For YFV, NS1-specific antibodies clearly had a protective function.61,82 Therefore, whether an efficacious dengue vaccine needs to induce NS1-specific antibodies should be tested in the future.

Viremia

Transient viremia is frequently detected in YF-17D vaccine recipients. This low level of replication of the vaccine virus provides sufficient antigens to activate immune responses, but not enough to harm the host. With TDV, only a small percentage of vaccines had viremia after vaccination,116,121 which could also explain why the chimeric YF/dengue vaccine was less efficacious than the YF-17D vaccine. A comparison of the immune responses and patterns of viremia induced by the dengue vaccine CYD-TDV and YF-17D is provided in Table 3.

Table 3. Immune responses elicited by CYD-TDV and YF-17D vaccines.

| Immune responses types | CYD-TDV | YF-17D | References | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Innate immunity | NK | IFN-γ+ | ND | ↑ | 41 |

| IL-4+ | ND | ↓ | 41 | ||

| CD56+CD69+ | ND | ↑ | 40 | ||

| CD56+CD16+ | ND | ↑ | 40 | ||

| mDC | CD80+ | ↑ | ↑ | 34,107 | |

| CD83+ | ↑ | — | 33,34,107 | ||

| CD86+ | ↑ | ↑ | 32,33,34,107 | ||

| IL-10+ | — | ↑ | 34,107 | ||

| IL-1β | — | ↑ | 38,107 | ||

| pDC | ND | ↑ | 34,38 | ||

| Monocyte | TNF-α+ | ND | ↑ | 41,43,44 | |

| IL-10+ | ND | ↑ | 41,43 | ||

| Adaptive immunity | CD8+ T | IFN-γ+ | ↑ | ↑ | 26,45,49,50,108 |

| CD4+ T | IL-4+ | — | ↑ | 34,54,55,108 | |

| TNF-α+ | — | ↑ | 34,54,55,108 | ||

| IFN-γ+ | CYD-4 ↑ | ↑ | 34,54,55,108 | ||

| IL-2+ | — | ↑ | 34,54,55,108 | ||

| nAbs | IgM | ND | ↑ | 74,75 | |

| IgG | ND | ↑ | 59 | ||

| Viremia | ∼10% | ∼100% | 25,26,116,121 | ||

↑, Up-regulated; ↓, down-regulated; —, Non-significant changed

nAbs, neutralizing antibodies; ND, Not determined.

PERSPECTIVE

The human yellow fever vaccine YF-17D is highly efficacious. Its immunological signature is marked by the efficient activation of APC, the induction of potent innate immune responses including the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, the elicitation of high titers of neutralizing antibodies, the induction of poly-functional CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, and the stimulation of long-term memory cellular and humoral immunity. Transient viremia may be necessary to provide sufficient antigens to activate both the innate and adaptive immune responses.

In contrast to the YF-17D vaccine, the tetravalent chimeric YF/dengue vaccine does not stimulate a potent early pro-inflammatory response, elicits only a modest level of neutralizing antibodies, and possibly activates only limited CD8+ T cells. Additionally, most vaccine recipients do not demonstrate viremia. These major differences between the highly successful YF-17D and a less efficacious dengue vaccine should provide sufficient indications to provide a guide for future development in the design and testing of the next generation of dengue vaccines.

Acknowledgments

The work was supported in part by a program project grant from the Shanghai Pasteur Health Research Foundation (Y359P41505) to XJ.

References

- 1Mackenzie JS, Gubler DJ, Petersen LR. Emerging flaviviruses: the spread and resurgence of Japanese encephalitis, West Nile and dengue viruses. Nat Med 2004; 10: S98–S109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2World Health Organization. Yellow fever fact sheet No.100. [Updated March 2014]. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs100/en/#.

- 3World Health Organization. Japanese encephalitis fact sheet No. 386. [Updated March 2014]. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs386/en/.

- 4Bhatt S, Gething PW, Brady OJ, Messina JP, Farlow AW, Moyes CL et al. The global distribution and burden of dengue. Nature 2013; 496: 504–507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5Kramer LD, Ebel GD. Dynamics of flavivirus infection in mosquitoes. Adv Virus Res 2003; 60: 187–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6Aitken TH, Tesh RB, Beaty BJ, Rosen L. Transovarial transmission of yellow fever virus by mosquitoes (Aedes aegypti). Am J Trop Med Hyg 1979; 28: 119–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7Rosen L, Tesh RB, Lien JC, Cross JH. Transovarial transmission of Japanese encephalitis virus by mosquitoes. Science 1978; 199: 909–911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8Chambers TJ, Hahn CS, Galler R, Rice CM. Flavivirus genome organization, expression, and replication. Annu Rev Microbiol 1990; 44: 649–688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9Rice CM, Lenches EM, Eddy SR, Shin SJ, Sheets RL, Strauss JH. Nucleotide sequence of yellow fever virus: implications for flavivirus gene expression and evolution. Science 1985; 229: 726–733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10Modis Y, Ogata S, Clements D, Harrison SC. Structure of the dengue virus envelope protein after membrane fusion. Nature 2004; 427: 313–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11Kuhn RJ, Zhang W, Rossmann MG, Pletnev SV, Corver J, Lenches E et al. Structure of dengue virus: implications for flavivirus organization, maturation, and fusion. Cell 2002; 108: 717–725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12Murphy BR, Whitehead SS. Immune response to dengue virus and prospects for a vaccine. Annu Rev Immunol 2011; 29: 587–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13Mackenzie JM, Jones MK, Westaway EG. Markers for trans-Golgi membranes and the intermediate compartment localize to induced membranes with distinct replication functions in flavivirus-infected cells. J Virol 1999; 73: 9555–9567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14Chu PW, Westaway EG. Replication strategy of Kunjin virus: evidence for recycling role of replicative form RNA as template in semiconservative and asymmetric replication. Virol 1985; 140: 68–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15Coia G, Parker MD, Speight G, Byrne ME, Westaway EG. Nucleotide and complete amino acid sequences of Kunjin virus: definitive gene order and characteristics of the virus-specified proteins. J Gen Virol 1988; 69: 1–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16Mackenzie JM, Khromykh AA, Jones MK, Westaway EG. Subcellular localization and some biochemical properties of the flavivirus Kunjin nonstructural proteins NS2A and NS4A. Virol 1998; 245: 203–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17Westaway EG, Khromykh AA, Kenney MT, Mackenzie JM, Jones MK. Proteins C and NS4B of the flavivirus Kunjin translocate independently into the nucleus. Virol 1997; 234: 31–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18Westaway EG, Mackenzie JM, Kenney MT, Jones MK, Khromykh AA. Ultrastructure of Kunjin virus-infected cells: colocalization of NS1 and NS3 with double-stranded RNA, and of NS2B with NS3, in virus-induced membrane structures. J Virol 1997; 71: 6650–6661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19Khromykh AA, Varnavski AN, Sedlak PL, Westaway EG. Coupling between replication and packaging of flavivirus RNA: evidence derived from the use of DNA-based full-length cDNA clones of Kunjin virus. J Virol 2001; 75: 4633–4640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20Macnamara FN. Reactions following neurotropic yellow fever vaccine given by scarification in Nigeria. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 1953; 47: 199–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21Theiler M, Smith HH. The effect of prolonged cultivation in vitro upon the pathogenicity of yellow fever virus. J Exp Med 1937; 65: 767–786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22Theiler M, Smith HH. The use of yellow fever virus modified by in vitro cultivation for human immunization. J Exp Med 1937; 65: 787–800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23Pulendran B. Learning immunology from the yellow fever vaccine: innate immunity to systems vaccinology. Nat Rev Immunol 2009; 9: 741–747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24Pulendran B, Oh JZ, Nakaya HI, Ravindran R, Kazmin DA. Immunity to viruses: learning from successful human vaccines. Immunol Rev 2013; 255: 243–255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25Reinhardt B, Jaspert R, Niedrig M, Kostner C, L'age-Stehr J. Development of viremia and humoral and cellular parameters of immune activation after vaccination with yellow fever virus strain 17D: a model of human flavivirus infection. J Med Virol 1998; 56: 159–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26Edupuganti S, Eidex RB, Keyserling H, Akondy RS, Lanciotti R, Orenstein W et al. A randomized, double-blind, controlled trial of the 17D yellow fever virus vaccine given in combination with immune globulin or placebo: comparative viremia and immunogenicity. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2013; 88: 172–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27Albert BS. Research on dengue during World War II. Arch Virol 1952; 1: 30–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28Luiza-Silva M, Campi-Azevedo AC, Batista MA, Martins MA, Avelar RS, Da Silveira Lemos D et al. Cytokine signatures of innate and adaptive immunity in 17DD yellow fever vaccinated children and its association with the level of neutralizing antibody. J Infect Dis 2011; 204: 873–883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29Banchereau J, Steinman RM. Dendritic cells and the control of immunity. Nature 1998; 392: 245–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30Steinman R, Banchereau J. Taking dendritic cells into medicine. Nature 2007; 449: 419–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31Pulendran B. Variegation of the immune response with dendritic cells and pathogen recognition receptors. J Immunol 2005; 174: 2457–2465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32Querec TD, Akondy RS, Lee EK, Cao W, Nakaya HI, Teuwen D et al. Systems biology approach predicts immunogenicity of the yellow fever vaccine in humans. Nat Immunol 2009; 10: 116–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33Barba-Spaeth G, Longman RS, Albert ML, Rice CM. Live attenuated yellow fever 17D infects human DCs and allows for presentation of endogenous and recombinant T cell epitopes. J Exp Med 2005; 202: 1179–1184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34Querec T, Bennouna S, Alkan S, Laouar Y, Gorden K, Flavell R et al. Yellow fever vaccine YF-17D activates multiple dendritic cell subsets via TLR2, 7, 8, and 9 to stimulate polyvalent immunity. J Exp Med 2006; 203: 413–424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35Schnare M, Barton GM, Holt AC, Takeda K, Akira S, Medzhitov R. Toll-like receptors control activation of adaptive immune responses. Nat Immunol 2001; 2: 947–950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36Dillon S, Agrawal A, Van Dyke T, Landreth G, Mccauley L, Koh A et al. A Toll-like receptor 2 ligand stimulates Th2 responses in vivo, via induction of extracellular signal-regulated kinase mitogen-activated proteinkinase and c-Fos in dendritic cells. J Immunol 2004; 172: 4733–4743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37Agrawal S, Agrawal A, Doughty B, Gerwitz A, Blenis J, Van Dyke T et al. Cutting edge: different Toll-like receptor agonists instruct dendritic cells to induce distinct Th responses via differential modulation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase-mitogen-activated protein kinase and c-Fos. J Immunol 2003; 171: 4984–4989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38Gaucher D, Therrien R, Kettaf N, Angermann BR, Boucher G, Filali-Mouhim A et al. Yellow fever vaccine induces integrated multilineage and polyfunctional immune responses. J Exp Med 2008; 205: 3119–3131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39Moretta A, Marcenaro E, Parolini S, Ferlazzo G, Moretta L. NK cells at the interface between innate and adaptive immunity. Cell Death Differ 2008; 15: 226–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40Neves PC, Matos DC, Marcovistz R, Galler R. TLR expression and NK cell activation after human yellow fever vaccination. Vaccine 2009; 27: 5543–5549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41Silva ML, Martins MA, Espirito-Santo LR, Campi-Azevedo AC, Silveira-Lemos D, Ribeiro JG et al. Characterization of main cytokine sources from the innate and adaptive immune responses following primary 17DD yellow fever vaccination in adults. Vaccine 2011; 29: 583–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42Liprandi F, Walder R. Replication of virulent and attenuated strains of yellow fever virus in human monocytes and macrophage-like cells (U937). Arch Virol 1983; 76: 51–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43Martins MA, Silva ML, Eloi-Santos SM, Ribeiro JG, Peruhype-Magalhaes V, Marciano AP et al. Innate immunity phenotypic features point toward simultaneous raise of activation and modulation events following 17DD live attenuated yellow fever first-time vaccination. Vaccine 2008; 26: 1173–1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44Belge KU, Dayyani F, Horelt A, Siedlar M, Frankenberger M, Frankenberger B et al. The proinflammatory CD14+CD16+DR++ monocytes are a major source of TNF. J Immunol 2002; 168: 3536–3542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45Akondy RS, Monson ND, Miller JD, Edupuganti S, Teuwen D, Wu H et al. The yellow fever virus vaccine induces a broad and polyfunctional human memory CD8+ T cell response. J Immunol 2009; 183: 7919–7930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46De Melo AB, Nascimento EJ, Braga-Neto U, Dhalia R, Silva AM, Oelke M et al. T-cell memory responses elicited by yellow fever vaccine are targeted to overlapping epitopes containing multiple HLA-I and -II binding motifs. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2013; 7: e1938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47Co MD, Terajima M, Cruz J, Ennis FA, Rothman AL. Human cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses to live attenuated 17D yellow fever vaccine: identification of HLA-B35-restricted CTL epitopes on nonstructural proteins NS1, NS2b, NS3, and the structural protein E. Virology 2002; 293: 151–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48Co MD, Kilpatrick ED, Rothman AL. Dynamics of the CD8 T-cell response following yellow fever virus 17D immunization. Immunology 2009; 128: e718–e727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49Miller JD, Van Der Most RG, Akondy RS, Glidewell JT, Albott S, Masopust D et al. Human effector and memory CD8+ T cell responses to smallpox and yellow fever vaccines. Immunity 2008; 28: 710–722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50Blom K, Braun M, Ivarsson MA, Gonzalez VD, Falconer K, Moll M et al. Temporal dynamics of the primary human T cell response to yellow fever virus 17D as it matures from an effector- to a memory-type response. J Immunol 2013; 190: 2150–2158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51Bassi MR, Kongsgaard M, Steffensen MA, Fenger C, Rasmussen M, Skjodt K et al. CD8+ T cells complement antibodies in protecting against yellow fever virus. J Immunol 2015; 194: 1141–1153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52Zellweger RM, Tang WW, Eddy WE, King K, Sanchez MC, Shresta S. CD8+ T cells can mediate short-term protection against heterotypic dengue virus reinfection in mice. J Virol 2015; 89: 6494–6505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53Santos AP, Matos DC, Bertho AL, Mendonca SC, Marcovistz R. Detection of Th1/Th2 cytokine signatures in yellow fever 17DD first-time vaccines through ELISpot assay. Cytokine 2008; 42: 152–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54Kohler S, Bethke N, Böthe M, Sommerick S, Frentsch M, Romagnani C et al. The early cellular signatures of protective immunity induced by live viral vaccination. Eur J Immunol 2012; 42: 2363–2373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55James EA, Lafond RE, Gates TJ, Mai DT, Malhotra U, Kwok WW. Yellow fever vaccination elicits broad functional CD4+ T cell responses that recognize structural and nonstructural proteins. J Virol 2013; 87: 12794–12804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56Darrah PA, Patel DT, De Luca PM, Lindsay RW, Davey DF, Flynn BJ et al. Multifunctional TH1 cells define a correlate of vaccine-mediated protection against Leishmania major. Nat Med 2007; 13: 843–850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57Barrett AD, Teuwen DE. Yellow fever vaccine - how does it work and why do rare cases of serious adverse events take place? Curr Opin Immunol 2009; 21: 308–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58Muyanja E, Ssemaganda A, Ngauv P, Cubas R, Perrin H, Srinivasan D et al. Immune activation alters cellular and humoral responses to yellow fever 17D vaccine. J Clin Invest 2014; 124: 3147–3158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59Poland JD, Calisher CH, Monath TP, Downs WG, Murphy K. Persistence of neutralizing antibody 30–35 years after immunization with 17D yellow fever vaccine. Bull World Health Org 1981; 59: 895–900. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60Brandriss MW, Schlesinger JJ, Walsh EE, Briselli M. Lethal 17D yellow fever encephalitis in mice. I. Passive protection by monoclonal antibodies to the envelope proteins of 17D yellow fever and dengue 2 viruses. J Gen Virol 1986; 67: 229–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61Schlesinger JJ, Brandriss MW, Cropp CB, Monath TP. Protection against yellow fever in monkeys by immunization with yellow fever virus nonstructural protein NS1. J Virol 1986; 60: 1153–1155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62Thibodeaux BA, Garbino NC, Liss NM, Piper J, Schlesinger JJ, Blair CD et al. A humanized IgG but not IgM antibody is effective in prophylaxis and therapy of yellow fever infection in an AG129/17D-204 peripheral challenge mouse model. Antiviral Res 2012; 94: 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63Monath TP, Vasconcelos PF. Yellow fever. J Clin Virol 2014; 64: 160–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64Monath TP, Nichols R, Archambault WT, Moore L, Marchesani R, Tian J et al. Comparative safety and immunogenicity of two yellow fever 17D vaccines (Arilvax and YF-VAX) in a Phase III multicenter, double-blind clinical trial. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2002; 66: 533–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65Julander JG, Trent DW, Monath TP. Immune correlates of protection against yellow fever determined by passive immunization and challenge in the hamster model. Vaccine 2011; 29: 6008–6016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66Kay A, Chen LH, Sisti M, Monath TP. Short report: yellow fever vaccine seroconversion in travelers. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2011; 85: 748–749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67Hepburn MJ, Kortepeter MG, Pittman PR, Boudreau EF, Mangiafico JA, Buck PA et al. Neutralizing antibody response to booster vaccination with the 17d yellow fever vaccine. Vaccine 2006; 24: 2843–2849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68Osei-Kwasi M, Dunyo SK, Koram KA, Afari EA, Odoom JK, Nkrumah FK. Antibody response to 17D yellow fever vaccine in Ghanaian infants. Bull World Health Org 2001; 79: 1056–1059. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69Lang J, Zuckerman J, Clarke P, Barrett P, Kirkpatrick C, Blondeau C. Comparison of the immunogenicity and safety of two 17D yellow fever vaccines. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1999; 60: 1045–1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70Groot H, Bahiarib. R. Neutralizing and haemagglutination-inhibiting antibodies to yellow fever 17 years after vaccination with 17D vaccine. Bull World Health Org 1962; 27: 699–707. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71Vaccines. CGFSOYF. Duration of post-vaccination immunity against yellow fever in adults. Vaccine 2014; 32: 4977–4984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72Gotuzzo E, Yactayo S, Cordova E. Efficacy and duration of immunity after yellow fever vaccination: systematic review on the need for a booster every 10 years. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2013; 89: 434–444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73Niedrig M, Lademann M, Emmerich P, Lafrenz M. Assessment of IgG antibodies against yellow fever virus after vaccination with 17D by different assays: neutralization test, haemagglutination inhibition test, immunofluorescence assay and ELISA. Trop Med Int Health 1999; 4: 867–871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74Monath TP. Neutralizing antibody responses in the major immunoglobulin classes to yellow fever 17D vaccination of humans. Am J Epidemiol 1971; 93: 122–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75Gibney KB, Edupuganti S, Panella AJ, Kosoy OI, Delorey MJ, Lanciotti RS et al. Detection of anti-yellow fever virus immunoglobulin M antibodies at 3–4 years following yellow fever vaccination. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2012; 87: 1112–1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76Heinz FX, Stiasny K. Flaviviruses and their antigenic structure. J Clin Virol 2012; 55: 289–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77Monath TP. Yellow fever: an update. Lancet Infect Dis 2001; 1: 11–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78Oliphant T, Engle M, Nybakken GE, Doane C, Johnson S, Huang L et al. Development of a humanized monoclonal antibody with therapeutic potential against West Nile virus. Nat Med 2005; 11: 522–530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79Beasley DW, Barrett AD. Identification of neutralizing epitopes within structural domain III of the West Nile virus envelope protein. J Virol 2002; 76: 13097–13100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80Sukupolvi-Petty S, Austin SK, Purtha WE, Oliphant T, Nybakken GE, Schlesinger JJ et al. Type- and subcomplex-specific neutralizing antibodies against domain III of dengue virus type 2 envelope protein recognize adjacent epitopes. J Virol 2007; 81: 12816–12826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81Vratskikh O, Stiasny K, Zlatkovic J, Tsouchnikas G, Jarmer J, Karrer U et al. Dissection of antibody specificities induced by yellow fever vaccination. PLoS Pathog 2013; 9: e1003458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82Schlesinger JJ, Brandriss MW, Walsh EE. Protection against 17D yellow fever encephalitis in mice by passive transfer of monoclonal antibodies to the nonstructural glycoprotein Gp48 and by active immunization with Gp48. J Immunol 1985; 135: 2805–2809. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83Schlesinger JJ, Foltzer M, Chapman S. The Fc portion of antibody to yellow-fever virus-Ns1 is a determinant of protection against yellow fever encephalitis in mice. Virology 1993; 192: 132–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84Pierson TC, Fremont DH, Kuhn RJ, Diamond MS. Structural insights into the mechanisms of antibody-mediated neutralization of flavivirus infection: implications for vaccine development. Cell Host Microbe 2008; 4: 229–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85Russell PK, Nisalak A. Dengue virus identification by the plaque reduction neutralization test. J Immunol 1967; 99: 291–296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86Normile D. Tropical medicine. Surprising new dengue virus throws a spanner in disease control efforts. Science 2013; 342: 415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87Halstead SB. Neutralization and antibody-dependent enhancement of dengue viruses. Adv Virus Res 2003; 60: 421–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88Morens DM, Halstead SB. Measurement of antibody-dependent infection enhancement of four dengue virus serotypes by monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies. J Gen Virol 1990; 71 (Pt12): 2909–2914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89Guzman MG, Alvarez M, Halstead SB. Secondary infection as a risk factor for dengue hemorrhagic fever/dengue shock syndrome: an historical perspective and role of antibody-dependent enhancement of infection. Arch Virol 2013; 158: 1445–1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90Osorio JE, Velez ID, Thomson C, Lopez L, Jimenez A, Haller AA et al. Safety and immunogenicity of a recombinant live attenuated tetravalent dengue vaccine (DENVax) in flavivirus-naive healthy adults in Colombia: a randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 1 study. Lancet Infect Dis 2014; 14: 830–838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91Durbin AP, Kirkpatrick BD, Pierce KK, Elwood D, Larsson CJ, Lindow JC et al. A single dose of any of four different live attenuated tetravalent dengue vaccines is safe and immunogenic in flavivirus-naive adults: a randomized, double-blind clinical trial. J Infect Dis 2013; 207: 957–965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92Beckett CG, Tjaden J, Burgess T, Danko JR, Tamminga C, Simmons M et al. Evaluation of a prototype dengue-1 DNA vaccine in a Phase 1 clinical trial. Vaccine 2011; 29: 960–968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93Huang CY, Butrapet S, Tsuchiya KR, Bhamarapravati N, Gubler DJ, Kinney RM. Dengue 2 PDK-53 virus as a chimeric carrier for tetravalent dengue vaccine development. J Virol 2003; 77: 11436–11447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94George SL, Wong MA, Dube TJ, Boroughs KL, Stovall JL, Luy BE et al. Safety and immunogenicity of a live attenuated tetravalent dengue vaccine candidate in flavivirus-naive adults: a randomized, double-blinded Phase 1 clinical trial. J Infect Dis 2015; doi:10.1093/infdis/jiv179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 95Blaney JE, Durbin AP, Murphy BR, Whitehead SS. Development of a live attenuated dengue virus vaccine using reverse genetics. Viral Immunol 2006; 19: 10–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96Durbin AP, Mcarthur JH, Marron JA, Blaney JE, Thumar B, Wanionek K et al. rDEN2/4Delta30(ME), a live attenuated chimeric dengue serotype 2 vaccine is safe and highly immunogenic in healthy dengue-naïve adults. Hum Vaccin 2006; 2: 255–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97Kirkpatrick BD, Durbin AP, Pierce KK, Carmolli MP, Tibery CM, Grier PL et al. Robust and balanced immune responses to all 4 dengue virus serotypes following administration of a single dose of a live attenuated tetravalent dengue vaccine to healthy, flavivirus-naive adults. J Infect Dis 2015; 212 (5):702–710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98Kanesa-Thasan N, Edelman R, Tacket CO, Wasserman SS, Vaughn DW, Coster TS et al. Phase 1 studies of Walter Reed Army Institute of Research candidate attenuated dengue vaccines: selection of safe and immunogenic monovalent vaccines. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2003; 69: 17–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99Simasathien S, Thomas SJ, Watanaveeradej V, Nisalak A, Barberousse C, Innis BL et al. Safety and immunogenicity of a tetravalent live-attenuated dengue vaccine in flavivirus naive children. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2008; 78: 426–433. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100Watanaveeradej V, Simasathien S, Nisalak A, Endy TP, Jarman RG, Innis BL et al. Safety and immunogenicity of a tetravalent live-attenuated dengue vaccine in flavivirus-naive infants. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2011; 85: 341–351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101Watanaveeradej V, Gibbons RV, Simasathien S, Nisalak A, Jarman RG, Kerdpanich A et al. Safety and immunogenicity of a rederived, live-attenuated dengue virus vaccine in healthy adults living in Thailand: a randomized trial. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2014; 91: 119–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102Capeding MR, Tran NH, Hadinegoro SRS, Ismail HIHJM, Chotpitayasunondh T, Chua MN et al. Clinical efficacy and safety of a novel tetravalent dengue vaccine in healthy children in Asia: a phase 3, randomised, observer-masked, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2014; 384: 1358–1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103Guirakhoo F, Weltzin R, Chambers TJ, Zhang ZX, Soike K, Ratterree M et al. Recombinant chimeric yellow fever-dengue type 2 virus is immunogenic and protective in nonhuman primates. J Virol 2000; 74: 5477–5485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104Guirakhoo F, Arroyo J, Pugachev KV, Miller C, Zhang ZX, Weltzin R et al. Construction, safety, and immunogenicity in nonhuman primates of a chimeric yellow fever-dengue virus tetravalent vaccine. J Virol 2001; 75: 7290–7304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105Sabchareon A, Wallace D, Sirivichayakul C, Limkittikul K, Chanthavanich P, Suvannadabba S et al. Protective efficacy of the recombinant, live-attenuated, CYD tetravalent dengue vaccine in Thai schoolchildren: a randomised, controlled phase 2b trial. Lancet 2012; 380: 1559–1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106Villar L, Dayan GH, Arredondo-Garcia JL, Rivera DM, Cunha R, Deseda C et al. Efficacy of a tetravalent dengue vaccine in children in Latin America. N Engl J Med 2015; 372: 113–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107Deauvieau F, Sanchez V, Balas C, Kennel A, De Montfort A, Lang J et al. Innate immune responses in human dendritic cells upon infection by chimeric yellow-fever dengue vaccine serotypes 1–4. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2007; 76: 144–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108Guy B, Nougarede N, Begue S, Sanchez V, Souag N, Carre M et al. Cell-mediated immunity induced by chimeric tetravalent dengue vaccine in naive or flavivirus-primed subjects. Vaccine 2008; 26: 5712–5721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109Duangchinda T, Dejnirattisai W, Vasanawathana S, Limpitikul W, Tangthawornchaikul N, Malasit P et al. Immunodominant T-cell responses to dengue virus NS3 are associated with DHF. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2010; 107: 16922–16927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110Hatch S, Endy TP, Thomas S, Mathew A, Potts J, Pazoles P et al. Intracellular cytokine production by dengue virus-specific T cells correlates with subclinical secondary infection. J Infect Dis 2011; 203: 1282–1291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111Zellweger RM, Miller R, Eddy WE, White LJ, Johnston RE, Shresta S. Role of humoral versus cellular responses induced by a protective dengue vaccine candidate. PLoS Pathog 2013; 9: e1003723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112Rivino L, Kumaran EA, Jovanovic V, Nadua K, Teo EW, Pang SW et al. Differential targeting of viral components by CD4+ versus CD8+ T lymphocytes in dengue virus infection. J Virol 2013; 87: 2693–2706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113Capeding RZ, Luna IA, Bomasang E, Lupisan S, Lang J, Forrat R et al. Live-attenuated, tetravalent dengue vaccine in children, adolescents and adults in a dengue endemic country: randomized controlled phase I trial in the Philippines. Vaccine 2011; 29: 3863–3872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114Dayan GH, Garbes P, Noriega F, Izoton De Sadovsky AD, Rodrigues PM, Giuberti C et al. Immunogenicity and safety of a recombinant tetravalent dengue vaccine in children and adolescents ages 9–16 years in Brazil. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2013; 89: 1058–1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115Lanata CF, Andrade T, Gil AI, Terrones C, Valladolid O, Zambrano B et al. Immunogenicity and safety of tetravalent dengue vaccine in 2–11 year-olds previously vaccinated against yellow fever: randomized, controlled, phase II study in Piura, Peru. Vaccine 2012; 30: 5935–5941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116Poo J, Galan F, Forrat R, Zambrano B, Lang J, Dayan GH. Live-attenuated tetravalent dengue vaccine in dengue-naive children, adolescents, and adults in Mexico city: randomized controlled phase 1 trial of safety and immunogenicity. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2011; 30: e9–e17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117Leo YS, Wilder-Smith A, Archuleta S, Shek LP, Chong CY, Leong HN et al. Immunogenicity and safety of recombinant tetravalent dengue vaccine (CYD-TDV) in individuals aged 2–45 y: phase II randomized controlled trial in Singapore. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2012; 8: 1259–1271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118Schlesinger JJ, Brandriss MW, Walsh EE. Protection of mice against dengue 2 virus encephalitis by immunization with the dengue 2 virus non-structural glycoprotein NS1. J Gen Virol 1987; 68 (Pt3): 853–857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119Falgout B, Bray M, Schlesinger JJ, Lai CJ. Immunization of mice with recombinant vaccinia virus expressing authentic dengue virus nonstructural protein NS1 protects against lethal dengue virus encephalitis. J Virol 1990; 64: 4356–4363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120Avirutnan P, Punyadee N, Noisakran S, Komoltri C, Thiemmeca S, Auethavornanan K et al. Vascular leakage in severe dengue virus infections: a potential role for the nonstructural viral protein NS1 and complement. J Infect Dis 2006; 193: 1078–1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121Guirakhoo F, Kitchener S, Morrison D, Forrat R, Mccarthy K, Nichols R et al. Live attenuated chimeric yellow fever dengue type 2 (ChimeriVaxTM-DEN2) vaccine: phase I clinical trial for safety and immunogenicity: effect of yellow fever pre-immunity in induction of cross neutralizing antibody responses to all 4 dengue serotypes. Hum Vaccin 2006; 2: 60–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122Barrett AD. Yellow fever vaccines. Biologicals 1997; 25: 17–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123Jennings AD, Whitby JE, Minor PD, Barrett ADT. Comparison of nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequences of the envelope protein genes of the wild-type French viscerotropic strain of yellow fever virus and the live vaccine strain, French neurotropic vaccine, derived from it. Virology 1992; 192: 692–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124Martin M, Tsai TF, Cropp B, Chang GJ, Holmes DA, Tseng J et al. Fever and multisystem organ failure associated with 17D-204 yellow fever vaccination: a report of four cases. Lancet 2001; 358: 98–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125Monath TP. Yellow fever vaccine. Expert Rev Vaccines 2005; 4: 553–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]