Abstract

Serotonin neurons located in the raphe nucleus of the hindbrain have crucial roles in regulating brain functions and have been implicated in various psychiatric disorders. Yet functional human serotonin neurons are not available for in vitro studies. Through manipulation of the WNT pathway, we demonstrate efficient differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs) to cells resembling central serotonin neurons, primarily those located in the rhombomeric segments 2–3 of the rostral raphe, which participate in high-order brain functions. The serotonin neurons express a series of molecules essential for serotonergic development, including tryptophan hydroxylase 2, exhibit typical electrophysiological properties and release serotonin in an activity-dependent manner. When treated with the FDA-approved drugs tramadol and escitalopram oxalate, they release or uptake serotonin in a dose- and time-dependent manner, suggesting the utility of these cells for the evaluation of drug candidates.

Serotonin is involved in the regulation of mood, affection, cognition, aggression, satiety, sleep and other autonomic functions. Dysfunction of the serotonin system, especially misregulation of serotonin release or uptake, has been linked to schizophrenia, depression, bipolar disorder, anxiety, obsessive-compulsive disorder, chronic pain syndrome and eating disorders. The serotonin system is therefore a major target for the treatment of multiple psychiatric disorders1. Serotonin neurons are localized to the raphe nucleus of the hindbrain and arise during development from ventral hindbrain progenitors, which are specified by gradient concentrations of WNTs along the anterior-posterior axis; the higher the WNT concentration, the more caudal the cells will become2. Serotonin neurons are divided into two groups depending on their anatomical locations and projections, which are likely also influenced by WNT signaling. The rostral division is located just caudal to the isthmus and these neurons project and innervate virtually all areas of the brain. Among them, the progenitors located at rhombomeric (r) segments 2–3 are distinguished from r1 by expression of HOXA2 but not EN1, and generate median raphe serotonin neurons3,4. The caudal division is situated in the myelencephalon, and these neurons send descending axons to the spinal cord5. Thus, serotonin neurons are essential for diverse neural functions despite their minority in the brain (~20,000 in the rat brain and ~300,000 in the human brain)6,7.

To facilitate in vitro study of human central serotonin neurons and the development of therapeutics that target the serotonin system, we describe a strategy to differentiate hPSCs (both embryonic stem cells (hESCs) and induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) to serotonin neurons by activating WNT and sonic hedgehog (SHH) signaling. The progenitors subsequently differentiate into a highly enriched population of cells that express key serotonin markers, including serotonin, TPH2, GATA3, GATA2, PET1, LMX1B, SERT, AADC and VMAT2. First, we differentiated human PSCs to hindbrain neural stem cells (NSCs) in a chemically defined medium containing transforming growth factor (TGF)-β inhibitor SB431542, BMP inhibitor DMH1 and GSK3-β inhibitor CHIR99021 (SDC medium) (Fig. 1a). After 1 week in SDC medium, PSC markers OCT4 and NANOG were downregulated, and NSC markers SOX1, PAX6 and N-Cadherin were upregulated. No obvious expression of endoderm markers (EOMES and SOX17), mesoderm marker (T, Brachyury) or trophoblast marker (CDX2) was detected by Q-PCR (Supplementary Fig. 1a). Immunostaining and flow cytometry analysis confirmed that most of the cells expressed SOX1 and SOX2 but not OCT4 (Supplementary Fig. 1b–d), suggesting an NSC identity.

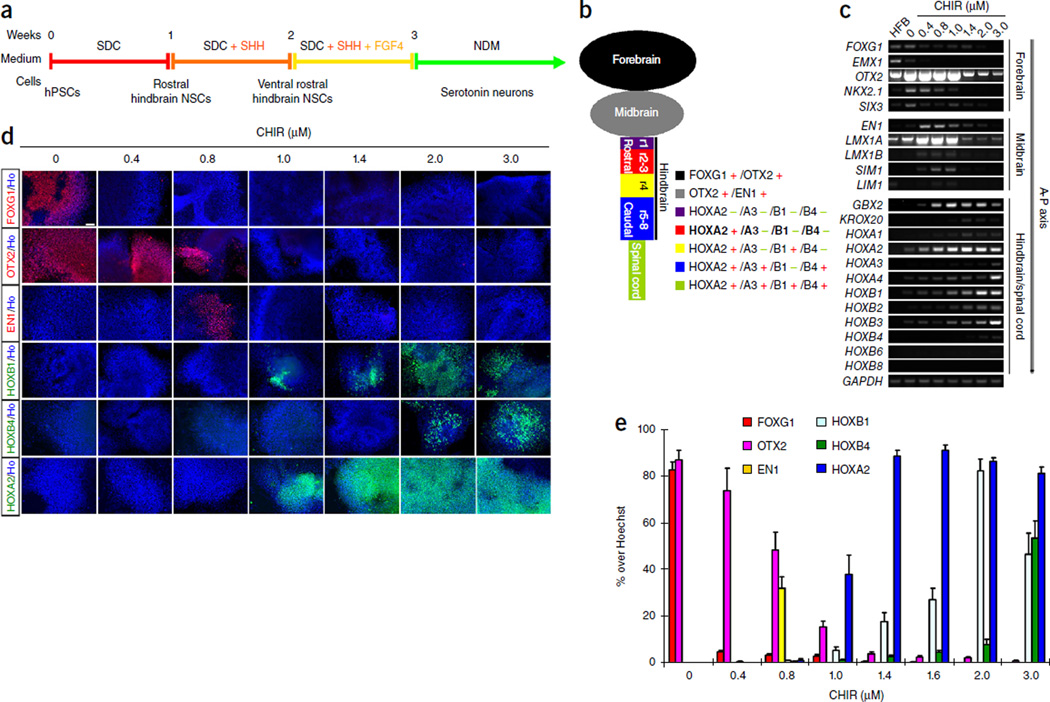

Figure 1.

Specification of rostral hindbrain progenitors. (a) Schematic representation of human central serotonergic neuron generation process. (b) Regional markers along the anterior-posterior neuroaxis (A–P axis). (c) RT-PCR of regional neural markers along the A–P axis when cells were treated with different concentrations of CHIR99021 (n = 2). (d) Cells stained for typical regional markers when treated with different concentrations of CHIR99021. (e) Quantification of positively stained cells in d (n = 3). Data are represented as mean ± s.e.m. Scale bar, 50 µm. Ho, Hoechst staining; HFB, human fetal brain samples; CHIR, CHIR99021.

The hindbrain is divided into rostral regions (r1–3) and caudal regions (r5–8) by the r4 region, which expresses HOXB1. The r1 region is distinguished from the r2–3 regions by expression of HOXA2, with r1 being HOXA2- and r2–3 being HOXA2+ (refs. 5,8) (Fig. 1b). We and others have shown that WNT activation by CHIR99021 specifies caudal neural progenitors in a dose-dependent manner9–12. Indeed, when we increased the concentration of CHIR99021 to >1.0 µM, most of the cells exhibited hindbrain or spinal cord identities, indicated by the downregulation of forebrain and midbrain markers (FOXG1, EMX1, OTX2, NKX2.1, SIX3, EN1, LMX1A, LMX1B, SIM1 and LIM1) and upregulation of hindbrain and spinal cord markers (GBX2, KROX20, HOXA1, HOXA2, HOXA3, HOXA4, HOXB1, HOXB2, HOXB3 and HOXB4) (Fig. 1c). Cells expressing forebrain and/or midbrain markers (FOXG1, OTX2, EN1) gradually decreased, and those expressing hindbrain and spinal cord markers (HOXA2, HOXB1, HOXB4) gradually increased with increasing concentrations of CHIR99021 (Fig. 1d,e). In cultures treated with 1.4 µM CHIR99021, most of the cells expressed HOXA2 but not HOXB1; at the same time, they were negative for HOXA3, a marker for the caudal hindbrain and spinal cord (Fig. 1b,e and Supplementary Fig. 1e). HOXA2-expressing cells decreased with lower concentrations of CHIR99021 (<1.4 µM), whereas HOXB1- and HOXB4-expressing cells increased with higher concentrations of CHIR99021 (>1.4 µM). These data indicate that rostral (r2–3) hindbrain NSCs are efficiently specified by 1.4 µM CHIR99021.

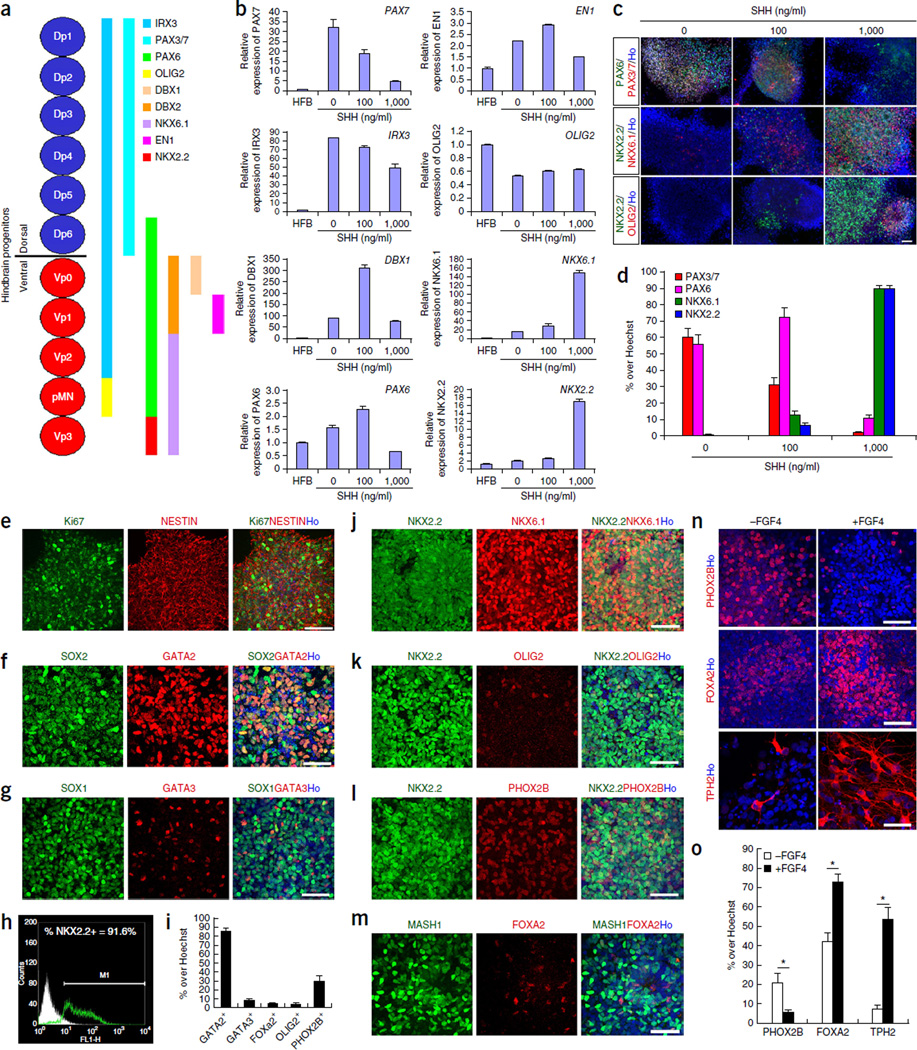

Next we sought to specify the rostral (r2–3) hindbrain NSCs into serotonin neuron progenitors. Serotonin neurons arise from progenitors in the ventral hindbrain that express NKX2.2 and NKX6.1 but not OLIG2 (ref. 13 and Fig. 2a). We treated the differentiation cultures with SHH starting with week 2. As SHH concentrations increased, the expression of dorsal hindbrain markers (such as PAX3, PAX7 and IRX3) decreased; whereas the expression of ventral hindbrain markers (such as NKX6.1 and NKX2.2) increased (Fig. 2b–d). With a high concentration of SHH (1,000 ng/ml) for 1 week, the cells retained the neural progenitor and hindbrain identity, as indicated by the expression of Ki67, NESTIN, SOX1 and SOX2 (Fig. 2e–g and Supplementary Fig. 2a). However, the majority of the cells were NKX2.2+ (89.8 ± 2.1%) and NKX6.1+ (90.0 ± 1.6%), whereas <5% of cells were OLIG2+ (Fig. 2h–k). During serotonin neuron specification, NKX2.2 cooperates with MASH1 and GATA2 (GATA binding protein 2, for rostral serotonin neurons) or GATA3 (for caudal serotonin neurons)1,14. In the culture, a substantial number of cells were MASH1+ (44.9 ± 7.0%) and GATA2+ (85.6 ± 3.4%), whereas only a few cells expressed GATA3 (8.3 ± 1.9%) (Fig. 2f,g,m), suggesting that the cells were primarily rostral serotonin neuron progenitors.

Figure 2.

Specification of ventral hindbrain progenitors. (a) Regional markers along the dorsal-ventral neuroaxis (D–V axis). (b) Q-PCR of regional markers along the D–V axis when cells were treated with different concentrations of SHH (n = 3). Data are represented as mean ± s.e.m. (c) Cells stained with typical regional markers when treated with different concentrations of SHH. (d) Quantification of positively stained cells in c (n = 3). Data are represented as mean ± s.e.m. (e–g) Cells stained for Ki67, NESTIN, SOX2, GATA2, SOX1 and GATA3 when treated with 1,000 ng/ml SHH. (h) FACS image of NKX2.2-expressing cells when treated with 1,000 ng/ml SHH. (i) Quantification of positively stained cells in f, g, k, l and m (n = 3). Data are represented as mean ± s.e.m. (j–m) Cells stained for NKX2.2, NKX6.1, OLIG2, PHOX2B, MASH1 and FOXA2 when treated with 1,000 ng/ml SHH. (n) Cells stained for PHOX2B, FOXA2 and TPH2, either untreated or treated with FGF4 in week 3 of differentiation. (o) Quantification of positively stained cells in n (n = 3). Data are represented as mean ± s.e.m. *P < 0.05, Student’s t-test. Scale bars, 50 µm. Ho, Hoechst staining.

FOXA2 is another transcription factor critical for the serotonergic fate, and is repressed by PHOX2B at r2–3 and r5–8 regions1,15. After 2 weeks of differentiation and 1 week of treatment with SHH, few FOXA2+ cells were found, whereas 30% of the cells retained PHOX2B (30.6 ± 5.0%) (Fig. 2l,m). This result suggests that additional signals are necessary to generate the serotonergic fate. As SHH cooperates with FGF4 (fibroblast growth factor 4) to promote the serotonergic program16, we applied FGF4 together with SHH for 1 week at the start of the second week of differentiation. A substantial increase in OLIG2+ cells was observed (Supplementary Fig. 2b,c), suggesting that FGF4 interferes with the ventralization of the hindbrain progenitors at this stage. Notably, when FGF4 was applied 1 week after cells were ventralized by SHH (after 3 weeks of differentiation), more cells turned on the expression of FOXA2 (72.4 ± 4.1%) and turned down the expression of PHOX2B (5.5 ± 1.1%), with a subsequent enriched TPH2 (tryptophan hydroxylase 2)-positive population after neuronal differentiation (Fig. 2n,o). These data suggest that FGF4 facilitates the serotonergic program of the ventral hindbrain progenitors.

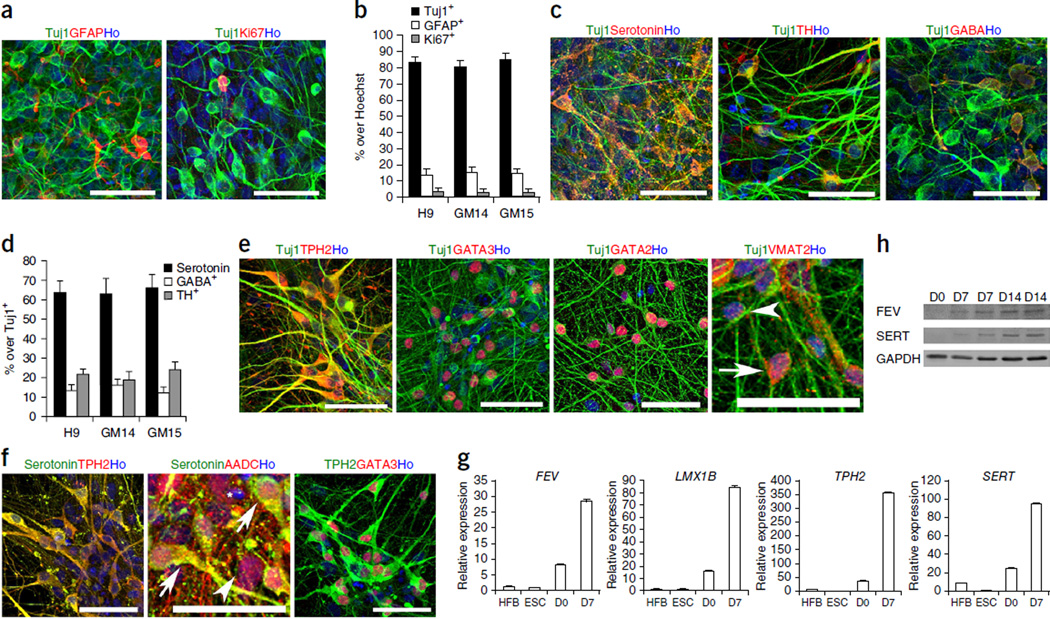

To assess the differentiation potential of the progenitors, we seeded them as single cells and cultured them in neural differentiation medium (NDM) without morphogens. Four weeks later, most of the cells became Tuj1+ neurons (>80%), whereas a small portion of the cells were GFAP+ astrocytes (<15%) and Ki67+ dividing cells (<1%) (Fig. 3a,b). Among the neurons, >60% were serotonin+, ~20% were TH+ neurons and ~15% were GABA+ neurons (Fig. 3c,d). Most of the neurons also expressed markers for central serotonin neurons TPH2, GATA2 and VMAT2 (vesicular monoamine transporter 2). GATA3 was also turned on (Fig. 3e). Double-staining for serotonin and TPH2, serotonin and AADC (aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase), and TPH2 and GATA3 (Fig. 3f) further indicated that the serotonin+ neurons were central serotonergic neurons. Q-PCR and western blot analysis showed upregulation of other markers for serotonin neurons, including FEV (fifth Ewing variant, the human ortholog of mouse Pet-1), SERT (the serotonin transporter) and LMX1b (LIM homeobox transcription factor 1β) (Fig. 3g,h). No serotonin neurons were found in cultures not treated with SHH and FGF4 (Supplementary Fig. 3a,b). The efficient generation of serotonin neurons was reproduced in human ESCs (H9 line) and iPSCs (lines GM14 and GM15) (Fig. 3b,d).

Figure 3.

Generation of central serotonin neurons. (a) Cells stained for Tuj1, GFAP and Ki67 after 4 weeks of neuronal differentiation. (b) Quantification of positively stained cells in a (n = 3). Data are represented as mean ± s.e.m. (c) Cells stained for serotonin, TH and GABA after 4 weeks of neuronal differentiation. (d) Quantification of positively stained cells in c (n = 3). Data are represented as mean ± s.e.m. (e, f) Cells co-stained for Tuj1 and serotonin, TPH2, GATA3, GATA2, GATA3, AADC and VMAT2 after 4 weeks of neuronal differentiation. In e, arrowhead indicates VMAT2− cell, arrow indicates VMAT2+ cell; in f, arrowhead indicates AADC− cell, arrows indicate AADC+ cells, and asterisk marks Hoechst-stained nucleus. (g) Q-PCR of central serotonergic neuron markers FEV, LMX1B, TPH2 and SERT during neuronal differentiation (n = 3). Data are represented as mean ± s.e.m. (h) Western blot of central serotonin neuron markers FEV and SERT during neuronal differentiation. Scale bars, 50 µm. Ho, Hoechst staining; HFB, human fetal brain samples; ESC, human embryonic stem cells; D0, day 0; D7, day 7; D14, day 14. Full-length blots can be found in Supplementray Figure 5.

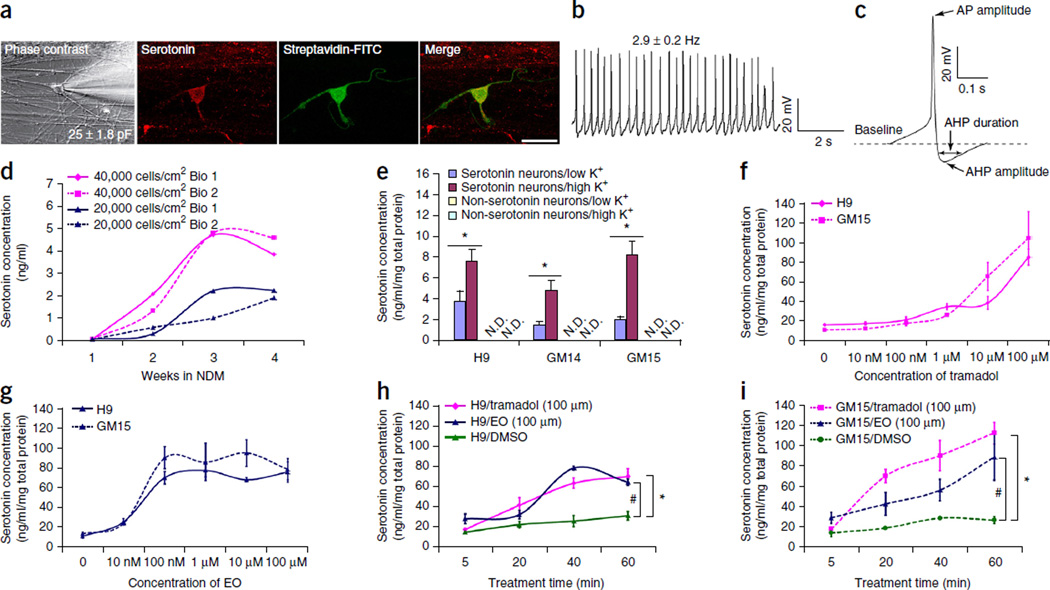

To assess functional maturation, we used electrophysiological whole-cell recording at 6 weeks in culture (Fig. 4a). In the 15 neurons tested, the mean cell capacitance (Cap) and input resistance (Rin) was 25.0 ± 1.8 pF and 622.6 ± 27.8 MΩ, respectively. Inward Na+ and outward K+ currents were observed in these cells by voltage steps from −50 mV to +50 mV (Supplementary Fig. 4a), implying the potentiation of action potentials. Indeed, injection of currents from −40 pA to +100 pA firmly triggered action potentials (Supplementary Fig. 4b). Injected currents as low as +10 pA induced action potentials of a frequency positively correlated to the size of injected currents (Supplementary Fig. 4c). In ~80% (12 of 15) of recorded neurons, excitatory (downward) and inhibitory (upward) postsynaptic spontaneous synaptic currents were observed, indicating formation of a functional synaptic network with surrounding neurons (Supplementary Fig. 4d). Around 60% (9 of 15) of recorded neurons displayed a low rate (2.9 ± 0.2 Hz) of spontaneous action potential spikes with a slow, subthreshold oscillatory potential (–30 mV, Fig. 4b), large action potential (65.3 ± 1.0 mV) and after hyperpolarization (−14.3 ± 0.6 mV), and long after hyperpolarization duration (87.4 ± 5.3 ms) (Fig. 4c), which are characteristic features of serotonin neurons17,18.

Figure 4.

Functional properties of the central serotonin neurons. (a) Representative hPSC-derived serotonergic neuron (stained with serotonin and injected with streptavidin-FITC) used for the electrophysiological assays. (b) Neurons displayed low rate of spontaneous action potential spiking with a subthreshold oscillatory potential (−30 mV). (c) Neurons displayed large action potential (AP) and after hyperpolarization (AHP), and long AHP duration. (d) Serotonin release from the neurons during neuronal maturation. Samples from hESCs (H9) (n = 4). (e) K+-induced serotonin release from the serotonin neurons (n = 3). *P < 0.05, Student’s t-test. N.D., not detectable. (f) Serotonin release in the presence of different dosages of tramadol (n = 3). (g) Serotonin release in the presence of different dosages of escitalopram oxalate (EO) (n = 3). (h, i) Time-dependent serotonin release of hESC H9-derived (h) or iPSC GM15-derived (i) central serotonergic neurons after being treated with 100 µM of tramadol, 100 µM of EO or the same quantity of DMSO (n = 3). Tramadol vs. DMSO: *P < 0.05; EO vs. DMSO: #P < 0.05; two-way analysis of variance. Data are represented as mean ± s.e.m. H9: human ESCs; GM14, GM15: human iPSCs. Scale bar, 50 µm.

Next, we studied serotonin release and uptake with high-performance liquid chromatography coupled to ultra-performance liquid chromatography–electrospray ionization–tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC-ESI-MS/MS). Serotonin release increased over time, reaching a plateau at 3–4 weeks of neuronal differentiation. More serotonin was released from the higher cell-density group (Fig. 4d). Stimulation of the cultures with high potassium (K+), which depolarizes neurons, significantly increased serotonin release (P < 0.05) (Fig. 4e), confirming serotonergic identity and the capacity of the cells to release serotonin in response to stimuli.

To determine whether the human serotonergic neuron culture could be used to validate serotonin releasers or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, we tested the effects of two US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved drugs—tramadol (Ultram, ConZip, Ryzolt), a mu opiate agonist, inhibitor of monoamine (including serotonin) reuptake and serotonin releaser that is used to treat pain19–21 and escitalopram oxalate (Lexapro; EO), a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor used for treatment of major depressive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder22—on neurons cultured in NDM for 4 weeks. After 1 h exposure to tramadol, serotonin release increased in a dose-dependent manner from neurons derived from both H9 ESCs and GM15 iPSCs (Fig. 4f). Similarly, after EO treatment, serotonin release reached the peak level at the dosage of 100 nM EO and stayed at the peak level at higher dosages of EO (Fig. 4g). When neurons were treated with either 100 µM tramadol or EO for different time periods, serotonin release increased in a time-dependent manner as compared to the DMSO solvent control (Fig. 4h,i).

We have developed a chemically defined system to induce hPSCs to ventral hindbrain progenitors mainly at r2–3 segments, which further differentiate to enriched populations of serotonin neurons. Differentiation of serotonin neurons has been attempted using mouse, monkey and human ESCs. The mouse studies used FGFs (FGF2, FGF4 and/or FGF8)23–25 as did the monkey studies (FGF2 and/or FGF4)26,27. The only report of serotonin neuron differentiation from human ESCs used FGF1, FGF2, retinoic acid and the efficiency of producing serotonin-expressing cells was very low28. Although these papers all showed generation of serotonin-expressing cells, they did not demonstrate that the cells were functional and released serotonin (Supplementary Table 1). It is now clear that FGFs are not effective in patterning human or nonhuman-primate ESCs to mid- or hindbrain progenitors12,29. In fact, early application of FGF4 interferes with the specification of serotonin progenitors, as we show here.

Human PSCs, when cultured in the absence of morphogens30 or in the presence of BMP and TGFβ inhibitors31, differentiate primarily to neural progenitors with forebrain identity. Thus, morphogens that promote caudalization, including WNTs and retinoic acid, are necessary. WNTs in particular are critical in patterning mid- and hindbrain identities in vivo32 and in vitro10–12. By fine-tuning the concentrations of CHIR99021, we specified not only mid- and hindbrain progenitors but also different subpopulations of hindbrain progenitors. At 1.4 µM of CHIR99021, we obtained an enriched population of r2–3 hindbrain progenitors. Lower CHIR99021 concentrations produced forebrain and midbrain progenitors, whereas higher concentrations led to posterior hindbrain or spinal cord cells. These results suggest that it should be possible to specify most neuronal subtypes in the brain.

A neural progenitor identity is defined by its dorsal-ventral as well as anterior-posterior location in the developing brain. To generate serotonin neurons, we ventralized the hindbrain neural progenitors with SHH, as indicated by their expression of NKX6.1 and NKX2.2. Efficient specification of a ventral transcription factor NKX2.2 in the hindbrain progenitors by SHH is critical, as NKX2.2 at the r2–3 region regulates the timing of PHOX2B and FOXA2 expression, which in turn influences the progenitor identity. FOXA2 is a floor plate transcription factor and PHOX2B is a proneural factor for motor neuron generation29,33. In the mouse embryonic brain, PHOX2B initially represses the expression of FOXA2 up to embryonic day(E)10.5. After that, FOXA2 represses PHOX2B to switch progenitors to the serotonergic fate1. It is by regulating the temporal switch between the expression of PHOX2B and FOXA2 by SHH in our hindbrain progenitors that we could generate highly enriched, subtype-specific ventral hindbrain progenitors with serotonergic potential.

The ventral hindbrain progenitors have the potential to become serotonin neurons but did not appear to give rise to serotonin neurons in our chemically defined system. During neural development, FGFs in the isthmus area contribute to specifying neuronal types with different transmitter phenotypes. FGF8 is important for midbrain dopamine neurons and FGF4 for hindbrain serotonergic neurons16. Indeed, we found that FGF4 significantly enhances the differentiation of the ventral hindbrain progenitors to serotonin neurons. This is very similar to the effect of FGF8 in promoting dopamine neuron differentiation from ventral midbrain progenitors12. The FGF4 effect is time-dependent, working after specification of ventral hindbrain progenitors. Earlier FGF4 application interferes with the specification of the NKX2.2+ and NKX6.1+ hindbrain progenitors, possibly by repressing SHH signaling34. Our finding may seem to contradict the observation that in rat explant cultures FGF4 must be added before SHH and FGF8 to generate serotonin neurons16. This may represent a species difference. However, the hindbrain tissue explant was exposed to SHH in the developing embryo before isolation16, which would be consistent with our observation.

Serotonin neurons exert diverse functions depending on their locations and targets. Those located in the anterior raphe project to almost the entire brain and regulate a multitude of central actions, including feeding, sleep and mood. Because we restricted the progenitors to the anterior ventral hindbrain fate, the differentiated serotonin neurons resemble those in the anterior raphe. They exhibited characteristic oscillatory action potential spikes and released serotonin under nonstimulated conditions, similar to what serotonin neurons do in the brain. Because they can be produced in large quantities, they can be used to validate drugs that affect serotonin release or uptake as an alternative to current assays based on dialysis measurement of serotonin in the dorsal raphe nucleus, prefrontal cortex and nucleus accumbens35–37.

ONLINE METHODS

Human PSCs culture

Human ESCs (H9, passages 25–40, originally from WiCell) and iPSCs (GM14, GM15, passages 35–50, homemade cell lines) were maintained on mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEF) feeder in a stem cell growth medium38,39. The human iPSCs were established using retroviral approaches with Yamanaka factors40. The cell lines tested negative for mycoplasma contamination.

Human central serotonin neuron differentiation

The process for human central serotonergic neuron generation is shown in Figure 1a. Human PSCs were seeded onto laminin (Life Technologies)-coated plastic plates or polyornithine (PO, from Sigma-Aldrich) and laminin-coated 12-mm glass coverslips. PSCs at approximately 20% confluence (1 d after passaging) were cultured for 1 week in a chemically defined medium modified from our previous work11. Briefly, the medium consists of DMEM/F12: neurobasal (1:1), 1 × N2, 1 × B27, 1 × nonessential amino acids (NEAA), 1% GlutaMAX (all from Life Technologies), 2 µM SB431542 (Stemgent) and 2 µM DMH1 (Tocris Bioscience). Different concentrations of CHIR99021 (0–3µM, Tocris Bioscience) were applied to identify a dose that specifies progenitors with the hindbrain fate. After 1 week of differentiation, cells were passed mechanically in the same chemically defined medium at the ratio of 1:3 onto precoated plates or coverslips and different concentrations of SHH C25II (0–1,000 ng/ml, R&D Systems) were applied to ventralize cells. After two weeks of differentiation, cells were passed as previously in the same CDM with 1,000 ng/ml SHH, and FGF4 (10 ng/ml) was used to help the specification of the serotonergic fate. From the fourth week, serotonergic progenitors were seeded onto PO- and laminin-coated glass coverslips and cultured in a neuronal differentiation medium (NDM) consisting of neurobasal with 1 × N2, 1 × B27, 1 × NEAA supplemented with 1 µg/ml laminin, 0.2 mM vitamin C (Tocris Bioscience), 2.5 µM DAPT (Tocris Bioscience), 10 ng/ml glial cell line–derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF), 10 ng/ml brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), 10 ng/ml insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I) and 1 ng/ml transforming growth factor β3 (all from PeproTech).

RNA extraction, RT-PCR and Q-PCR

RNA extraction, RT-PCR and Q-PCR analysis were described before11. To compare the expression level of different genes, probes were normalized to glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) by performing 15, 20 and 25 cycles. PCR conditions and cycle numbers were established by using commercially available human fetal brain (single donor, male, 19 weeks of gestation) (Agilent Technologies). Q-PCR was performed by using the Power SYBR Green kit (Applied Biosystems, UK). Primers are listed in Supplementary Table 2.

Immunocytochemistry

Immunostaining was performed as described previously11. In brief, cells were fixed in 4% neutral-buffered paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 20 min at room temperature. For detection of GABA, 0.05% glutaraldehyde (Electron Microscopy Sciences) was included in the fixative. All antibodies, sources and dilutions are listed in Supplementary Table 3. Cell populations were counted among total cells (Hoechst labeled) or neurons (Tuj1+) using the ImageJ software. At least five fields of each coverslip were chosen randomly, and three coverslips in each group were counted. Data were expressed as mean ± s.e.m.

Electrophysiology

Whole-cell patch-clamp recordings were made from human ESC-derived serotonergic neurons at 6 weeks. Briefly, the neurons were hold at −70 mV to record the Na+/K+ channel activities, and at 0 mV to record the spontaneous release with voltage-clamp model. For recording action potentials, the cells were held at 0 pA with the current-clamp model, and with the steps of injected currents from −40 pA to + 100 pA. The bath solution consisted of 127 mM NaCl, 1.2 mM KH2PO4, 1.9 mM KCl, 26 mM NaHCO3, 2.2 mM CaCl2, 1.4 mM MgSO4, 10 mM glucose, 290 mM mOsm and 95% O2/5% CO2. Recording pipettes were filled with an intracellular solution containing 20 mM KCl, 121 mM K+-gluconate, 10 mM Na+-HEPES, 10 mM BAPTA, 4 mM Mg2+-ATP pH 7.2 and 290 mOm. An Olympus BX51WI microscope was used to visualize neurons. A MultiClamp 700B amplifer (Axon instruments, Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) was used to investigate the voltage clamp and current clamp recordings. Signals were filtered at 4 kHZ and sampled at 100 kHz using a Digidata 1322A analog-digital converter (Axon instruments). Data were analyzed with pClamp 9.0 (Axon instruments).

Western blot analysis

Western blot analysis was done as described previously41. Briefly, cells were lysed in a lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 2% Triton X-100, 10 mM EDTA, 5 mM NaF and 1 mM sodium orthovanadate). Protein concentration was determined by BCA assay (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Then proteins were resolved in 12% SDS polyacrylamide gels and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes. The membranes were then incubated overnight at 4 °C in blocking solution containing 5% nonfat dry milk in PBS with 0.1% Tween-20. Subsequently the membranes were incubated with primary antibodies, followed by incubation with HRP (horseradish peroxidase)-conjugated second antibodies. Detection of HRP was performed by SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate (Pierce). Antibodies are listed in Supplementary Table 3.

Collection of serotonin release samples

To detect serotonin release into medium during neuronal differentiation, we collected NDM for the culture every week. To detect activity-dependent serotonin release, Krebs’ Ringer’s solution with specified K+ concentration was used as previously described42. Briefly, cultured cells were washed four times with Krebs’ Ringer’s solution containing 130 mM NaCl, 3 mM KCl, 2 mM CaCl2, 0.8 mM MgSO4, 10 mM glucose and 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.4) before the medium was collected with depolarizing Krebs’ Ringer’s solution containing 83 mM NaCl, 50 mM KCl, 2 mM CaCl2, 0.8 mM MgSO4, 10 mM glucose and 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.4). To detect drug- induced serotonin release, tramadol (Sigma) and escitalopram oxalate (EO, from Tocris Bioscience) were applied to the culture at different dosages and timing, and the NDM was collected at specific time points. The collected media were stored in −80 °C before detection.

Quantification of serotonin using UPLC-ESI-MS/MS

Around 1 ml of collected cell media or Krebs’-Ringer’s solution was spiked with 10 ng of d4-serotonin (internal standard, IS). Liquid-liquid extraction was performed to purify the sample before LC-MS analysis. A Dionex UPLC pump connected to a Q-Exactive Orbitrap mass spectrometer was used for LC-ESI-MS/MS analysis (Thermo Scientific, CA). A Kinetex 2.6 µm Biphenyl UPLC column (100 mm × 2.1 mm) equipped with a guard column was used for separation. The mobile phases were (A) water with 0.1% formic acid and (B) methanol with 0.1% formic acid. Multiplexed targeted-MS/MS scan function was used for data acquisition. For each sample, integrated peak area of extracted ion chromatogram of fragment ion m/z 160.075 was normalized to that of m/z 164.100 (fragment ion from IS) for determination of the concentration of serotonin. Standard calibration curves were generated for accurate quantification of serotonin in the cell medium and in the Krebs’-Ringer’s solution.

Statistical analysis

Values were expressed as mean ± s.e.m. Differences between means were assessed by two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for the data shown in Figure 4h,i and by Student’s t-test for the remaining data. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by US National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants (NS045926, MH099587 and MH100031 to S.C.Z.; 1R01DK071801 to L.L.) and the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD; P30 HD03352). The Q-Exactive Orbitrap mass spectrometer was purchased through the support of an NIH shared instrument grant (NIH–National Center for Research Resources (NCRR) S10RR029531 to L.L.). L.L. acknowledges an H.I. Romnes Faculty Research Fellowship. S.C.Z. acknowledges a Steenbock Professorship.

Footnotes

Note: Any Supplementary Information and Source Data files are available in the online version of the paper.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

J.L. designed and performed experiments, analyzed data and co-wrote the paper. X.Z., L.H., L.L. and M.A.S. processed and assessed the serotonin release samples. H.L. performed the whole-cell patch-clamp recordings. C.T.-L.H. cultured cells and performed immunocytochemistry experiments. M.A.S., J.J. and M.A. performed animal experiments. S.-C.Z. designed experiments and co-wrote the paper.

COMPETINGFINANCIAL INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Deneris ES, Wyler SC. Serotonergic transcriptional networks and potential importance to mental health. Nat. Neurosci. 2012;15:519–527. doi: 10.1038/nn.3039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kiecker C, Niehrs C. A morphogen gradient of Wnt/beta-catenin signalling regulates anteroposterior neural patterning in Xenopus. Development. 2001;128:4189–4201. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.21.4189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alonso A, et al. Development of the serotonergic cells in murine raphe nuclei and their relations with rhombomeric domains. Brain Struct. Funct. 2013;218:1229–1277. doi: 10.1007/s00429-012-0456-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bang SJ, Jensen P, Dymecki SM, Commons KG. Projections and interconnections of genetically defined serotonin neurons in mice. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2012;35:85–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2011.07936.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goridis C, Rohrer H. Specification of catecholaminergic and serotonergic neurons. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2002;3:531–541. doi: 10.1038/nrn871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jacobs BL, Azmitia EC. Structure and function of the brain serotonin system. Physiol. Rev. 1992;72:165–229. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1992.72.1.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen J, Condron BG. Branch architecture of the fly larval abdominal serotonergic neurons. Dev. Biol. 2008;320:30–38. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.03.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guthrie S. Patterning and axon guidance of cranial motor neurons. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2007;8:859–871. doi: 10.1038/nrn2254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kriks S, et al. Dopamine neurons derived from human ES cells efficiently engraft in animal models of Parkinson’s disease. Nature. 2011;480:547–551. doi: 10.1038/nature10648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kirkeby A, et al. Generation of regionally specified neural progenitors and functional neurons from human embryonic stem cells under defined conditions. Cell Reports. 2012;1:703–714. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lu J, et al. Generation of integration-free and region-specific neural progenitors from primate fibroblasts. Cell Reports. 2013;3:1580–1591. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xi J, et al. Specification of midbrain dopamine neurons from primate pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cells. 2012;30:1655–1663. doi: 10.1002/stem.1152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koch P, Opitz T, Steinbeck JA, Ladewig J, Brüstle O. A rosette-type, self-renewing human ES cell-derived neural stem cell with potential for in vitro instruction and synaptic integration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:3225–3230. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808387106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smidt MP, van Hooft JA. Subset specification of central serotonergic neurons. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2013;7:200. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2013.00200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alenina N, Bashammakh S, Bader M. Specification and differentiation of serotonergic neurons. Stem Cell Rev. 2006;2:5–10. doi: 10.1007/s12015-006-0002-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ye W, Shimamura K, Rubenstein JL, Hynes MA, Rosenthal A. FGF and Shh signals control dopaminergic and serotonergic cell fate in the anterior neural plate. Cell. 1998;93:755–766. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81437-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scott MM, et al. A genetic approach to access serotonin neurons for in vivo and in vitro studies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:16472–16477. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504510102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Calizo LH, et al. Raphe serotonin neurons are not homogenous: electrophysiological, morphological and neurochemical evidence. Neuropharmacology. 2011;61:524–543. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Raffa RB, et al. Opioid and nonopioid components independently contribute to the mechanism of action of tramadol, an ‘atypical’ opioid analgesic. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1992;260:275–285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Driessen B, Reimann W. Interaction of the central analgesic, tramadol, with the uptake and release of 5-hydroxytryptamine in the rat brain in vitro. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1992;105:147–151. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1992.tb14226.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kizilbash A, Ngô-Minh CT. Review of extended-release formulations of Tramadol for the management of chronic non-cancer pain: focus on marketed formulations. J. Pain Res. 2014;7:149–161. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S49502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pastoor D, Gobburu J. Clinical pharmacology review of escitalopram for the treatment of depression. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2014;10:121–128. doi: 10.1517/17425255.2014.863873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barberi T, et al. Neural subtype specification of fertilization and nuclear transfer embryonic stem cells and application in parkinsonian mice. Nat. Biotechnol. 2003;21:1200–1207. doi: 10.1038/nbt870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee SH, Lumelsky N, Studer L, Auerbach JM, McKay RD. Efficient generation of midbrain and hindbrain neurons from mouse embryonic stem cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 2000;18:675–679. doi: 10.1038/76536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim JH, et al. Dopamine neurons derived from embryonic stem cells function in an animal model of Parkinson’s disease. Nature. 2002;418:50–56. doi: 10.1038/nature00900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salli U, et al. Serotonin neurons derived from rhesus monkey embryonic stem cells: similarities to CNS serotonin neurons. Exp. Neurol. 2004;188:351–364. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tokuyama Y, Ingram SL, Woodward JS, Bethea CL. Functional characterization of rhesus embryonic stem cell-derived serotonin neurons. Exp. Biol. Med. 2010;235:649–657. doi: 10.1258/ebm.2010.009307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kumar M, Kaushalya SK, Gressens P, Maiti S, Mani S. Optimized derivation and functional characterization of 5-HT neurons from human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2009;18:615–627. doi: 10.1089/scd.2008.0181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maury Y, et al. Combinatorial analysis of developmental cues efficiently converts human pluripotent stem cells into multiple neuronal subtypes. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015;33:89–96. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li XJ, et al. Specification of motoneurons from human embryonic stem cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 2005;23:215–221. doi: 10.1038/nbt1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chambers SM, et al. Highly efficient neural conversion of human ES and iPS cells by dual inhibition of SMAD signaling. Nat. Biotechnol. 2009;27:275–280. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rhinn M, Brand M. The midbrain-hindbrain boundary organizer. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2001;11:34–42. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(00)00171-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gouti M, et al. In vitro generation of neuromesodermal progenitors reveals distinct roles for wnt signalling in the specification of spinal cord and paraxial mesoderm identity. PLoS Biol. 2014;12:e1001937. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hu BY, Du ZW, Li XJ, Ayala M, Zhang SC. Human oligodendrocytes from embryonic stem cells: conserved SHH signaling networks and divergent FGF effects. Development. 2009;136:1443–1452. doi: 10.1242/dev.029447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baumann MH, et al. Effects of phentermine and fenfluramine on extracellular dopamine and serotonin in rat nucleus accumbens: therapeutic implications. Synapse. 2000;36:102–113. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(200005)36:2<102::AID-SYN3>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pudovkina OL, Cremers TI, Westerink BH. Regulation of the release of serotonin in the dorsal raphe nucleus by alpha1 and alpha2 adrenoceptors. Synapse. 2003;50:77–82. doi: 10.1002/syn.10245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rothman RB, Baumann MH. Serotonin releasing agents. Neurochemical, therapeutic and adverse effects. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2002;71:825–836. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(01)00669-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hu BY, et al. Neural differentiation of human induced pluripotent stem cells follows developmental principles but with variable potency. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:4335–4340. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910012107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu H, et al. Spinal muscular atrophy patient-derived motor neurons exhibit hyperexcitability. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:12189. doi: 10.1038/srep12189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Takahashi K, et al. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell. 2007;131:861–872. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lu J, et al. All-trans retinoic acid promotes neural lineage entry by pluripotent embryonic stem cells via multiple pathways. BMC Cell Biol. 2009;10:57. doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-10-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ma L, et al. Human embryonic stem cell-derived GABA neurons correct locomotion deficits in quinolinic acid-lesioned mice. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;10:455–464. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.