Significance

The main advance of this study is the development of a microengineered model of human intestinal inflammation and bacterial overgrowth that permits analysis of individual contributors to the pathophysiology of intestinal diseases, such as ileus and inflammatory bowel disease, over a period of weeks in vitro. By studying living human intestinal epithelium, with or without vascular and lymphatic endothelium, immune cells, and mechanical deformation, as well as living microbiome and pathogenic microbes, we identified previously unknown contributions of specific cytokines, mechanical motions, and microbiome to intestinal inflammation, bacterial overgrowth, and control of barrier function. We provide proof-of-principle to show that the microfluidic gut-on-a-chip device can be used to create human intestinal disease models and gain new insights into gut pathophysiology.

Keywords: microbiome, gut-on-a-chip, intestine, inflammatory bowel disease, mechanical

Abstract

A human gut-on-a-chip microdevice was used to coculture multiple commensal microbes in contact with living human intestinal epithelial cells for more than a week in vitro and to analyze how gut microbiome, inflammatory cells, and peristalsis-associated mechanical deformations independently contribute to intestinal bacterial overgrowth and inflammation. This in vitro model replicated results from past animal and human studies, including demonstration that probiotic and antibiotic therapies can suppress villus injury induced by pathogenic bacteria. By ceasing peristalsis-like motions while maintaining luminal flow, lack of epithelial deformation was shown to trigger bacterial overgrowth similar to that observed in patients with ileus and inflammatory bowel disease. Analysis of intestinal inflammation on-chip revealed that immune cells and lipopolysaccharide endotoxin together stimulate epithelial cells to produce four proinflammatory cytokines (IL-8, IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α) that are necessary and sufficient to induce villus injury and compromise intestinal barrier function. Thus, this human gut-on-a-chip can be used to analyze contributions of microbiome to intestinal pathophysiology and dissect disease mechanisms in a controlled manner that is not possible using existing in vitro systems or animal models.

Various types of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), such as Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, involve chronic inflammation of human intestine with mucosal injury and villus destruction (1), which is believed to be caused by complex interactions between gut microbiome (including commensal and pathogenic microbes) (2), intestinal mucosa, and immune components (3). Suppression of peristalsis also has been strongly associated with intestinal pathology, inflammation (4, 5), and small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (5, 6) in patients with Crohn’s disease (7) and ileus (8). However, it has not been possible to study the relative contributions of these different potential contributing factors to human intestinal inflammatory diseases, because it is not possible to independently control these parameters in animal studies or in vitro models. In particular, given the recent recognition of the central role of the intestinal microbiome in human health and disease, including intestinal disorders (2), it is critical to incorporate commensal microbes into experimental models; however, this has not been possible using conventional culture systems.

Most models of human intestinal inflammatory diseases rely either on culturing an intestinal epithelial cell monolayer in static Transwell culture (9) or maintaining intact explanted human intestinal mucosa ex vivo (10) and then adding live microbes and immune cells to the apical (luminal) or basolateral (mucosal) sides of the cultures, respectively. These static in vitro methods, however, do not effectively recapitulate the pathophysiology of human IBD. For example, intestinal epithelial cells cultured in Transwell plates completely fail to undergo villus differentiation, produce mucus, or form the various specialized cell types of normal intestine. Although higher levels of intestinal differentiation can be obtained using recently developed 3D organoid cultures (11), it is not possible to expose these cells to physiological peristalsis-like motions or living microbiome in long-term culture, because bacterial overgrowth occurs rapidly (within ∼1 d) compromising the epithelium (12). This is a major limitation because establishment of stable symbiosis between the epithelium and resident gut microbiome as observed in the normal intestine is crucial for studying inflammatory disease initiation and progression (13), and rhythmical mechanical deformations driven by peristalsis are required to both maintain normal epithelial differentiation (14) and restrain microbial overgrowth in the intestine in vivo (15).

Thus, we set out to develop an experimental model that would overcome these limitations. To do this, we adapted a recently described human gut-on-a-chip microfluidic device that enables human intestinal epithelial cells (Caco-2) to be cultured in the presence of physiologically relevant luminal flow and peristalsis-like mechanical deformations, which promotes formation of intestinal villi lined by all four epithelial cell lineages of the small intestine (absorptive, goblet, enteroendocrine, and Paneth) (12, 16). These villi also have enhanced barrier function, drug-metabolizing cytochrome P450 activity, and apical mucus secretion compared with the same cells grown in conventional Transwell cultures, which made it possible to coculture a probiotic gut microbe (Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG) in direct contact with the intestinal epithelium for more than 2 wk (12), in contrast to static Transwell cultures (17) or organoid cultures (11) that lose viability within hours under similar conditions. In the present study, we leveraged this human gut-on-a-chip to develop a disease model of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) and inflammation. We analyzed how probiotic and pathogenic bacteria, lipopolysaccharide (LPS), immune cells, inflammatory cytokines, vascular endothelial cells and mechanical forces contribute individually, and in combination, to intestinal inflammation, villus injury, and compromise of epithelial barrier function. We also explored whether we could replicate the protective effects of clinical probiotic and antibiotic therapies on-chip to demonstrate its potential use as an in vitro tool for drug development, as well as for dissecting fundamental disease mechanisms.

Results

Establishing a Complex Human Intestinal Model in Vitro.

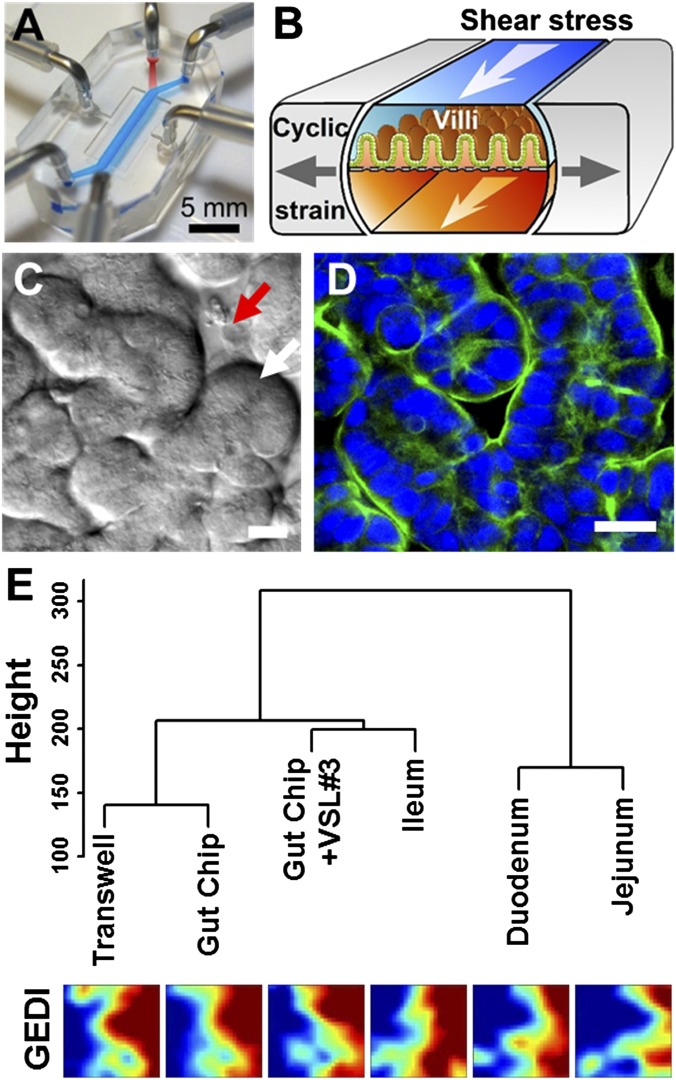

To study interactions between cultured microbiome and human intestinal epithelial cells in an organ-like context and mimic the human intestinal microenvironment undergoing injury and inflammation, we leveraged a gut-on-a-chip microfluidic device (12, 16) composed of optically clear, flexible polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) polymer with three parallel hollow microchannels (Fig. 1A). The central channel is split into an upper (lumen) and lower (capillary) channel by a flexible, extracellular matrix (ECM)-coated PDMS membrane containing an array of pores (10 µm in diameter) lined by human Caco-2 intestinal epithelial cells. The cells are exposed to trickling flow of culture medium (30 µL/h, equivalent to 0.02 dyne/cm2 shear stress) through the upper and lower microchannels and to cyclic peristalsis-like mechanical deformations (10% in cell strain, 0.15 Hz in frequency) (Movie S1) generated by applying cyclic suction to hollow side chambers that rhythmically deflect the central membrane with the attached cells (Fig. 1B). By mimicking the physical microenvironment of the intestine in this manner, the cultured human intestinal epithelial cells spontaneously form intestinal villi (Fig. 1C and Movie S1) lined by a highly polarized, differentiated columnar epithelium with a tight apical brush border (Fig. 1D) that appear similar in form to living intestinal villi in vivo (17).

Fig. 1.

The human gut-on-a-chip microfluidic device and changes in phenotype resulting from different culture conditions on-chip, as measured using genome-wide gene profiling. (A) A photograph of the device. Blue and red dyes fill the upper and lower microchannels, respectively. (B) A schematic of a 3D cross-section of the device showing how repeated suction to side channels (gray arrows) exerts peristalsis-like cyclic mechanical strain and fluid flow (white arrows) generates a shear stress in the perpendicular direction. (C) A DIC micrograph showing intestinal basal crypt (red arrow) and villi (white arrow) formed by human Caco-2 intestinal epithelial cells grown for ∼100 h in the gut-on-a-chip under medium flow (30 µL/h) and cyclic mechanical stretching (10%, 0.15 Hz). (Scale bar, 50 µm.) (D) A confocal immunofluorescence image showing a horizontal cross-section of intestinal villi similar to those shown in Fig. 1C, stained for F-actin (green) that labels the apical brush border of these polarized intestinal epithelial cells (nuclei in blue). (Scale bar, 50 µm.) (E) Hierarchical clustering analysis of genome-wide transcriptome profiles (Top) of Caco-2 cells cultured in the static Transwell, the gut-on-a-chip (with fluid flow at 30 µL/h and mechanical deformations at 10%, 0.15 Hz) (Gut Chip), or the mechanically active gut-on-a-chip cocultured with the VSL#3 formulation containing eight probiotic gut microbes (Gut Chip + VSL#3) for 72 h compared with normal human small intestinal tissues (Duodenum, Jejunum, and Ileum; microarray data from the published GEO database). The dendrogram was generated based on the averages calculated across all replicates, and all branches in the cluster have the approximately unbiased (AU) P value equal to 100. The y axis next to the dendrogram represents the metric for Euclidean distance between samples. Corresponding pseudocolored GEDI maps analyzing profiles of 650 metagenes between samples described above (Bottom).

To more clearly demonstrate the influence of culture conditions on the differentiation state of the Caco-2 cells, we performed genome-wide gene profiling analysis of the cells cultured as a static monolayer in a conventional Transwell insert, in the mechanically active gut-on-a-chip microdevice, or on-chip when cocultured with living commensal gut microbes. The commensal microbes used were contained in a therapeutic formulation of probiotic bacteria (VSL#3) that has been studied in humans (18), which contains eight strains of beneficial probiotic bacteria, including six that were originally isolated from human gut microbiome (Lactobacillus acidophilus, Lactobacillus plantarum, Lactobacillus paracasei, Bifidobacterium breve, Bifidobacterium longum, and Bifidobacterium infantis). Gene microarray analysis revealed that Caco-2 cells cultured in the gut-on-a-chip exhibit a significantly distinct gene expression profile (P < 0.00001) across 22,097 genes compared with the cells cultured in a static Transwell, and their phenotype again changed significantly (P < 0.00001) when commensal gut microbes were cocultured with the epithelium for 72 h in the lumen of the gut-on-a-chip (Fig. S1A). More importantly, hierarchical clustering analysis and GEDI visualization (19) revealed that the transcriptomes obtained from Caco-2 cells cocultured with multiple normal gut microbes (VSL#3) in the gut-on-a-chip are distinct from the profiles exhibited by the same cells cultured in the other conditions without microbes (P < 0.00001), and they are more similar to normal human ileum than to duodenum or jejunum (P < 0.00001) (Fig. 1E and Fig. S1B).

Fig. S1.

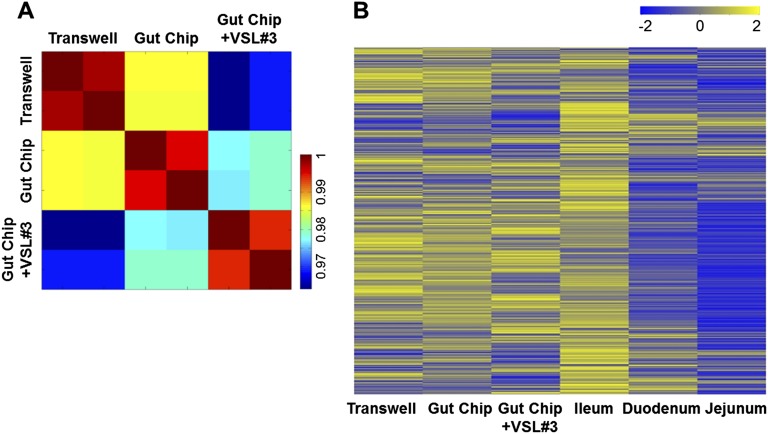

Transcriptome profiling of Caco-2 cells grown in various culture conditions and comparison with the normal human small intestinal tissues. (A) Visual representation of a Pearson correlation analysis of pairwise comparisons between transcriptome profiles of Caco-2 cells cultured in the static Transwell, the gut-on-a-chip (Gut Chip) with peristalsis-like fluid flow (30 µL/h) and mechanical deformations (10%, 0.15 Hz), or the mechanically active gut-on-a-chip cocultured with the VSL#3 formulation containing eight probiotic gut microbes (Gut Chip +VSL#3) for 72 h. Each group has two biological replicates, where an individual square in the heat map represents 22,097 human relevant genes (color bar indicates the relative expression levels). (B) Transcriptome hierarchical clustering analysis of genome-wide gene profiles of Caco-2 cells shown in Fig. 1E and Fig. S1A (Transwell, Gut Chip, and Gut Chip +VSL#3) compared with normal human small intestinal tissues (Duodenum, Jejunum, and Ileum; microarray data from the published GEO database). Color bar indicates the z-score scaled gene expression levels.

Reconstituting Human Intestinal Inflammation and Injury On-Chip.

We explored whether this system could be used to model human intestinal inflammation in vitro. Some of the key hallmarks of intestinal inflammatory diseases are the destruction of intestinal villi and associated compromise of the intestinal permeability barrier, which are believed to result from complex pathological interplay between the intestinal epithelium, gut microbes, and immune cells, as well as from changes in luminal flow resulting from altered peristalsis (1, 3).

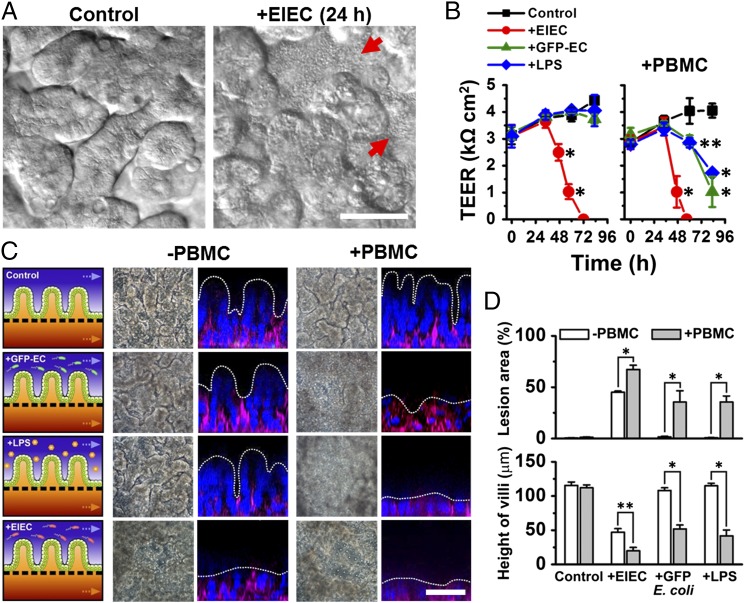

To explore how noncommensal microbes contribute to intestinal inflammation and gut injury, we cocultured Gram-negative Escherichia coli bacteria with the intestinal villus epithelium on-chip. When a nonpathogenic laboratory strain of green fluorescent protein-labeled E. coli (GFP-EC) was allowed to adhere to the apical (luminal) surface of villi for ∼1.5 h under static conditions, these bacteria subsequently colonized and spontaneously inhabited regions overlying the crypts localized between adjacent villi (Fig. S2). We next introduced a pathogenic strain (serotype O124:NM) of enteroinvasive E. coli (EIEC) that causes intestinal cell destruction and extreme diarrhea in humans (20) into the lumen of the epithelial channel. These EIEC bacteria initially distributed to similar locations between neighboring villi, but then they rapidly overgrew across the whole apical surface of villi within 24 h (Fig. 2A and Movie S2), and planktonic cells appeared in the culture medium within the channel lumen. Furthermore, when the gut-on-a-chip devices were maintained in coculture with GFP-EC for 4 additional days with cyclic mechanical deformation, the GFP-EC bacteria failed to alter normal intestinal barrier function as indicated by maintenance of a relatively constant transepithelial electrical resistance (TEER). When we added LPS endotoxin (15 µg/mL) isolated from pathogenic E. coli (serotype O111:B4) that elicits strong immune responses when administered in vivo (21), it similarly failed to disrupt the intestinal barrier on-chip (Fig. 2B), which mimics results previously observed in both other in vitro studies (22, 23) and animal models (24). There also was no detectable evidence of intestinal injury when analyzed using either phase contrast or fluorescence confocal microscopy (Fig. 2C). In contrast, when EIEC cells were added to the apical surface of epithelium, intestinal barrier function (Fig. 2B, Left) and normal villus architecture were completely lost within 24–36 h (Fig. 2C).

Fig. S2.

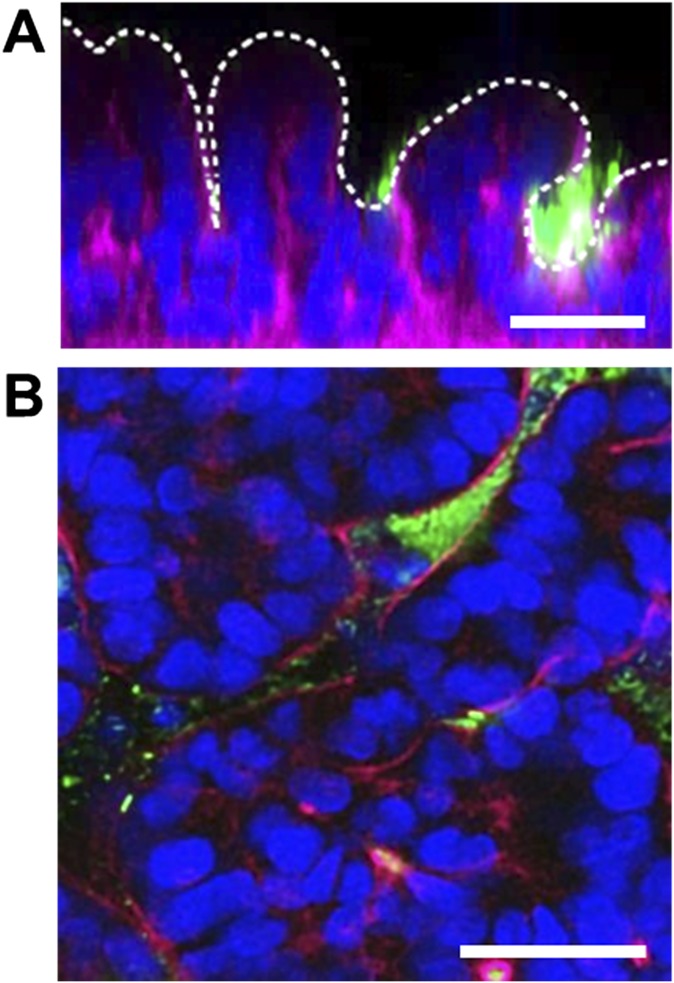

Fluorescence confocal micrographs of a vertical cross-section (A) and a horizontal cross-section (B) of microcolonies of GFP-labeled E. coli (GFP-EC; green) cultured on the intestinal epithelium (F-actin, magenta; nuclei, blue) on-chip for 2 d. White dotted line in A indicates the apical surface of the intestinal villi. Note that the bacteria preferentially inhabit the basal spaces between the villi. (Scale bars, 50 μm.)

Fig. 2.

Reconstitution of pathological intestinal injury induced by interplay between nonpathogenic or pathogenic enteroinvasive E. coli bacteria or LPS endotoxin with immune cells. (A) DIC images showing that the normal villus morphology of the intestinal epithelium cultured on-chip (Control) is lost within 24 h after EIEC (serotype O124:NM) are added to the apical channel of the chip (+EIEC; red arrows indicate bacterial colonies). (B) Effects of GFP-EC, LPS (15 µg/mL), EIEC, or no addition (Control) on intestinal barrier function (Left). Right shows the TEER profiles in the presence of human PBMCs (+PBMC). GFP-EC, LPS, and EIEC were added to the apical channel (intestinal lumen) at 4, 12, and 35 h, respectively, and PBMCs were subsequently introduced through the lower capillary channel at 44 h after the onset of experiment (0 h) (n = 4). (C) Morphological analysis of intestinal villus damage in response to addition of GFP-EC, LPS, and EIEC in the absence (−PBMC) or the presence of immune components (+PBMC). Schematics (experimental setup), phase contrast images (horizontal view, taken at 57 h after onset), and fluorescence confocal micrographs (vertical cross-sectional views at 83 h after onset) were sequentially displayed. F-actin and nuclei were coded with magenta and blue, respectively. (D) Quantification of intestinal injury evaluated by measuring changes in lesion area (Top; n = 30) and the height of the villi (Bottom; n = 50) in the absence (white) or the presence (gray) of PBMCs. Intestinal villi were grown in the gut-on-a-chip under trickling flow (30 µL/h) with cyclic deformations (10%, 0.15 Hz) during the preculture period for ∼100 h before stimulation (0 h, onset). Asterisks indicate statistical significance compared with the control at the same time point (*P < 0.001, **P < 0.05). (Scale bars, 50 µm.)

To mimic the chronically inflamed microenvironment of patients with intestinal inflammatory diseases, such as IBD, in which increased numbers of immune cells are recruited from the lamina propria (13), we carried out similar studies where isolated human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were introduced into the lower capillary channel of the device and allowed to interact with the lumen without flow for 2 h (SI Text, Inflammation Study). PBMCs contain a mixed population of innate (e.g., monocytes and granulocytes) and adaptive (e.g., lymphocytes) immune cells (Fig. S3) and have been used previously in various in vitro models of human intestinal inflammation (9, 23). Addition of PBMCs did not induce any detectable injury on their own; however, PBMCs synergized with either GFP-EC or LPS eliciting a significant decrease of intestinal barrier and major destruction and shortening of the intestinal villi (Fig. 2 B–D). Also, damage of the intestinal epithelium provoked by EIECs was accelerated and exacerbated by the presence of PBMCs (Fig. 2 B–D).

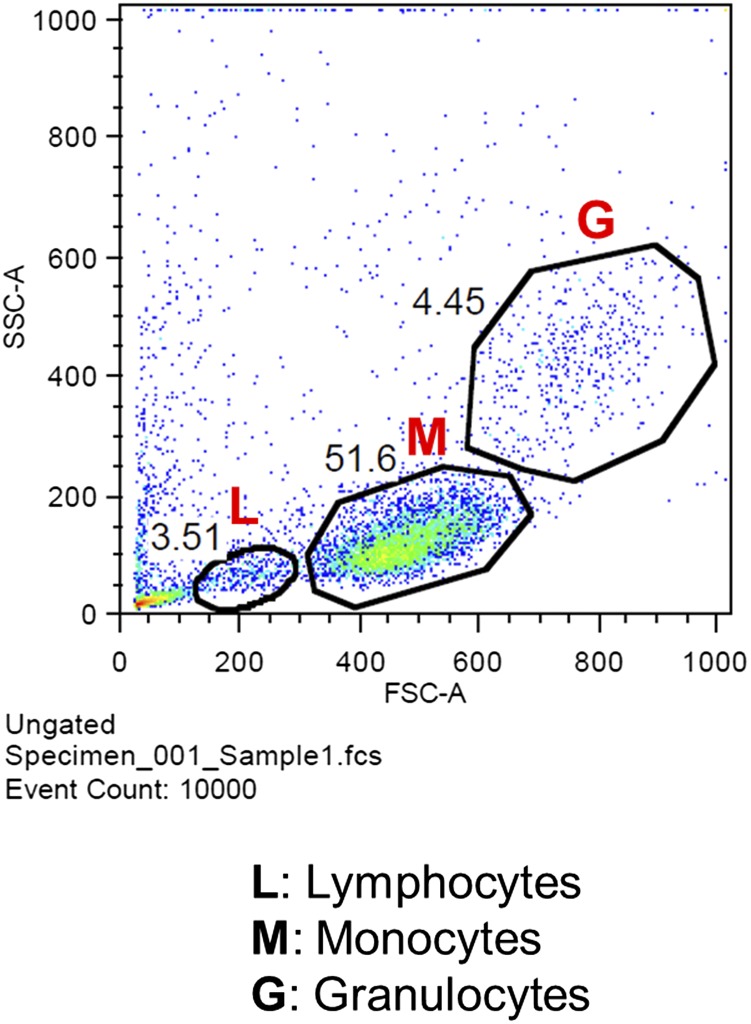

Fig. S3.

Cellular composition of PBMCs isolated from fresh human blood analyzed by flow cytometry. A representative flow cytometric dot plot shows the gating strategy for analyzing a mixed population of immune cell subsets such as monocyte (M), lymphocyte (L), and granulocyte (G) from PBMCs based on forward- and side-light scattering. See SI Text, Flow Cytometry.

Another key hallmark of intestinal inflammatory diseases is the production and secretion of inflammatory cytokines, which have been previously implicated in development of IBD (3, 25). We first analyzed production of a panel of cytokines relevant to intestinal inflammation in the gut-on-a-chip exposed to either LPS, PBMCs (Fig. 3A), or GFP-EC (Fig. S4A). LPS or GFP-EC alone did not alter production of any of these cytokines, and the PBMCs merely increased abluminal secretion of interleukin (IL)-8 into the lower capillary channel (Fig. 3A). In contrast, when PBMCs were combined with either LPS (Fig. 3A) or GFP-EC (Fig. S4A), there was a significant increase (P < 0.01) in polarized secretion of IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α into the basal channel, which is consistent with past observations (9), and there was strong activation of IL-8 production and toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) expression in the epithelium stimulated with PBMCs with LPS (Fig. S4B). Polarized basal secretion of cytokines should stimulate recruitment of additional circulating immune cells in vivo, which could further enhance cytokine production, thereby creating a positive feedback loop that might augment or exacerbate the inflammatory response.

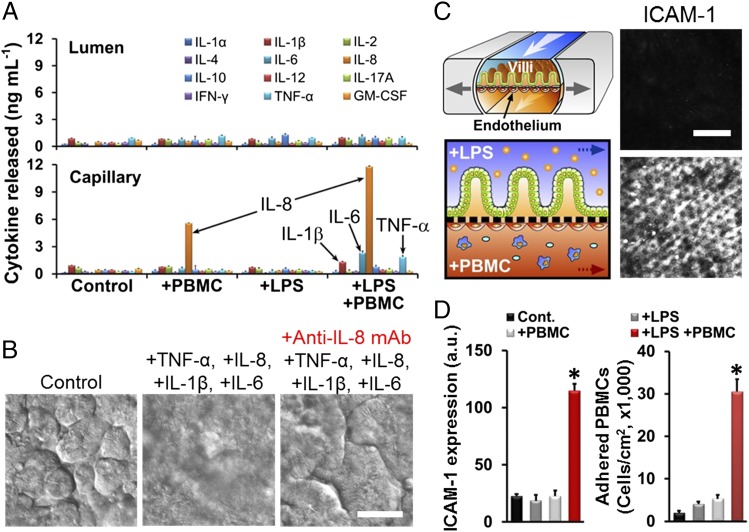

Fig. 3.

Tissue- and organ-level pathophysiological inflammatory responses of intestinal villus epithelium and vascular endothelium after being challenged with LPS and PBMCs. (A) Polarized secretion of proinflammatory cytokines after costimulation of LPS (15 µg/mL; for 32 h) and PBMCs (3.3 × 106 cells per mL; for 12 h). The concentrations of IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α secreted basolaterally were all significantly higher (P < 0.01) than in the control cultures (n = 3). (B) Villus injury caused by the treatment of four key proinflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α added at 3, 5, 15, and 4 ng/mL, respectively) and blocking effect of the anti-IL-8 monoclonal antibody (Anti-IL-8 mAb; 50 µg/mL) against the cytokine-induced villus injury. DIC images were recorded at 48 h after cytokine treatment. (C) The microenvironment of the tissue–tissue interface between the intestinal villus epithelium and vascular endothelium (Left Top) and the experimental design of studies involving challenge of this microenvironment with LPS and PBMCs (Left Bottom). Confocal microscopic fluorescence images show the ICAM-1 activation on the apical surface of the capillary endothelium in the absence (Right Top) or presence (Right Bottom) of both LPS (15 µg/mL) and PBMCs (3.3 × 106 cells per mL). (D) Quantification of the ICAM-1 expression (Left) and the number of adherent PBMCs on the surface of the activated capillary endothelium (Right). Black, control; dark gray, LPS alone; light gray, PBMCs alone; red, simultaneous administration of LPS and PBMCs (*P < 0.001; n = 50). (Scale bars, 50 µm.)

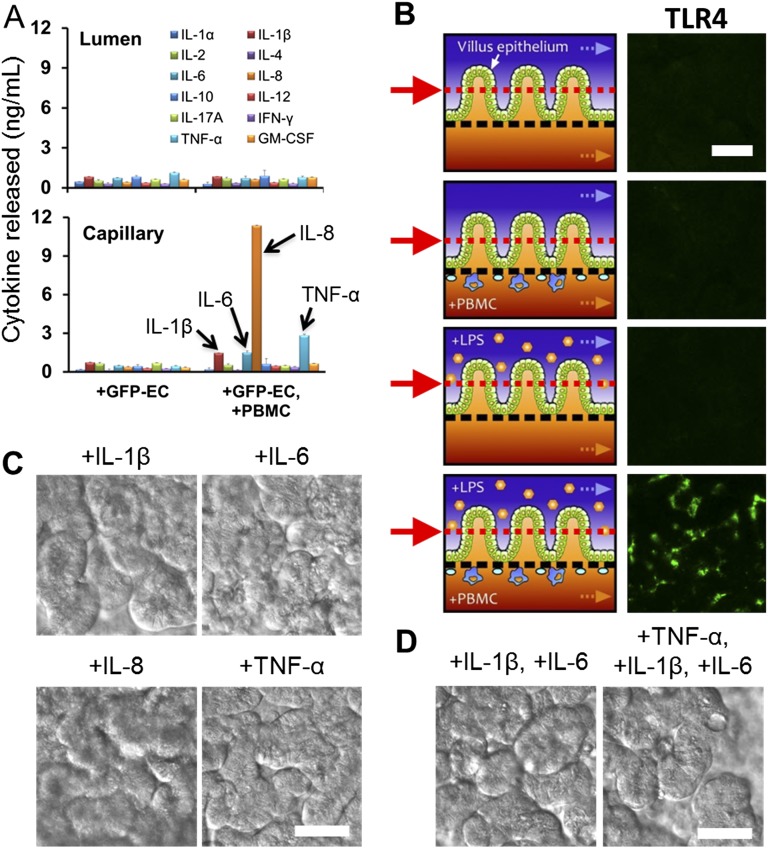

Fig. S4.

Polarized secretion of proinflammatory cytokines in response to the stimulation of the GFP E. coli alone (+GFP-EC; seeding density ∼1.0 × 107 cells per mL) or in the presence of PBMCs (+GFP-EC, +PBMC; 3.3 × 106 cells per mL) measured by ELISA (A). The concentrations of IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α secreted basolaterally were significantly higher (P < 0.01) than in the control cultures (n = 3). Intestinal villi were grown in the gut-on-a-chip at 40 µL/h in flow rate with cyclic deformations (10%, 0.15 Hz). (B) TLR4 expression on the villus epithelium. (Left) Schematics showing the experimental setup and (Right) immunofluorescence images showing that TLR4 was only expressed on the surface of the epithelium stimulated with LPS + PBMCs. Red arrows and matched dotted lines indicate the Z-position of the immunofluorescence image. Effects of individual (C) or partial combinations (D) of four cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, or TNF-α) on intestinal villus morphology. IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α were added at 3, 5, 15, and 4 ng/mL, respectively, which correspond to the levels measured in the gut-on-a-chip in the presence of both LPS and PBMCs (Fig. 3A). DIC images were taken at 48 h after addition of the cytokine. (Scale bars, 50 µm.)

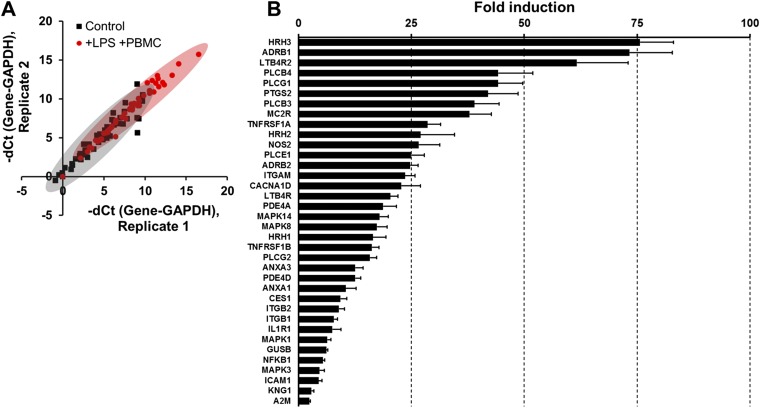

To investigate whether the detected cytokines were sufficient to induce damage to intestinal epithelial cells, we added purified IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α alone (Fig. S4C) or in different combinations (Fig. 3B and Fig. S4D) at the same concentrations they were produced on-chip (Fig. 3A). None of these individual cytokines induced villus injury (Fig. S4C), nor did addition of a mixture of IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α (Fig. S4D), even though these cytokines have been reported to contribute to intestinal damage in Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis in vivo (25). However, when these three cytokines were combined with IL-8, we were able to fully recapitulate the villus injury response observed by combined administration of LPS and PBMCs (Fig. 3A). In addition, coadministration of a blocking monoclonal IL-8 antibody completely prevented villus disruption in the presence of all four cytokines (Fig. 3B), even though addition of IL-8 alone was not sufficient to induce injury (Fig. S4C). Thus, our results suggest that although IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α were involved in induction of intestinal villus injury as suggested by in vivo studies (25), this combination is not sufficient to induce this pathological response unless IL-8 is also present at extremely high levels because low levels of production induced by PBMCs alone did not produce intestinal injury (Fig. 3A). To confirm that the cytokines were specifically produced by the intestinal epithelium, we separated the epithelial cells from the PBMCs and then carried out qPCR analysis for 92 known human inflammatory genes. These studies revealed that after being challenged simultaneously with LPS and PBMCs, the isolated intestinal epithelial cells significantly up-regulated (P < 0.05) the expression of 36 genes relative to untreated controls, whereas the same panel of inflammatory genes was undetectable in unstimulated PBMCs under these conditions (Fig. S5A). The intestinal epithelial cells increased their expression of genes encoding proteins that mediate early inflammatory signaling (e.g., PLCB3, PLCB4, PLCG1, PLCG2, TNFRSF1A, and PTGS2 also known as COX-2), as well as many that are important for leukocyte recruitment (e.g., LTB4R2, HRH1/2/3, NOS2, and ITGAM), by more than 25-fold (Fig. S5B). In addition, TLR activation is known to drive cytokine production (26), and we confirmed that the inflammatory activation of the epithelium resulted in a dramatic increase in epithelial cell expression of TLR4 when costimulated by PBMCs and LPS.

Fig. S5.

Profiling of genes involved in human inflammatory pathways for the microengineered intestinal villi challenged to LPS and PBMCs simultaneously in the gut-on-a-chip. (A) Expression profiling analysis of human inflammation-related genes expressed by the intestinal epithelium. Scatter spots shown in the correlation chart depict the individual genes in the nonstimulated villus epithelium (Control; black square) versus villus epithelium that was stimulated by LPS for 20 h followed by both LPS and PBMCs for an additional 20 h (+LPS +PBMC; red square). The delta threshold cycle (dCt) denotes the difference of the number of cycles that exceeds the baseline threshold between the gene of interest and a control gene (GAPDH). The averaged distribution of individual genes (n = 52) in each group was statistically significantly different (P < 0.0001) between the treated versus control groups. (B) A bar chart showing fold induction of genes relevant to human inflammation that exhibited statistically significant (n = 2, P < 0.05) increases in expression in villus epithelial cells challenged simultaneously with LPS and PBMCs compared with the nonstimulated control. These induced genes include alpha-2-Macroglobulin (A2M), beta-1 adrenergic receptor (ADRB1), beta-2 adrenergic receptor (ADRB2), annexin A1 (ANXA1), annexin A3 (ANXA3), calcium channel, voltage-dependent, L type, alpha 1D subunit (CACNA1D), carboxylesterase 1 (CES1), Beta-glucuronidase (GUSB), histamine H1 receptor (HRH1), histamine H2 receptor (HRH2), histamine H3 receptors (HRH3), intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM1), interleukin 1 receptor, type I (IL1R1), integrin alpha M (ITGAM), integrin beta-1 (ITGB1), integrin beta-2 (ITGB2), kininogen 1 (KNG1), leukotriene B4 receptor 1 (LTB4R), leukotriene B4 receptor 2 (LTB4R2), mitogen-activated protein kinase 1 (MAPK1), mitogen-activated protein kinase 3 (MAPK3), mitogen-activated protein kinase 8 (MAPK8), mitogen-activated protein kinase 14 (MAPK14), adrenocorticotropic hormone receptor (MC2R), nuclear factor NF-κ-B p105 subunit (NFKB1), nitric oxide synthase 2 (NOS2), cAMP-specific 3′,5′-cyclic phosphodiesterase 4A (PDE4A), cAMP-specific 3′,5′-cyclic phosphodiesterase 4D (PDE4D), 1-phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate phosphodiesterase beta-3 (PLCB3), 1-phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate phosphodiesterase beta-4 (PLCB4), 1-phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate phosphodiesterase epsilon-1 (PLCE1), phospholipase C, gamma 1 (PLCG1), 1-phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate phosphodiesterase gamma-2 (PLCG2), prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2 (PTGS2), tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily member 1A (TNFRSF1A), and tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily member 1B (TNFRSF1B).

Recapitulating Organ-Level Intestinal Inflammatory Responses.

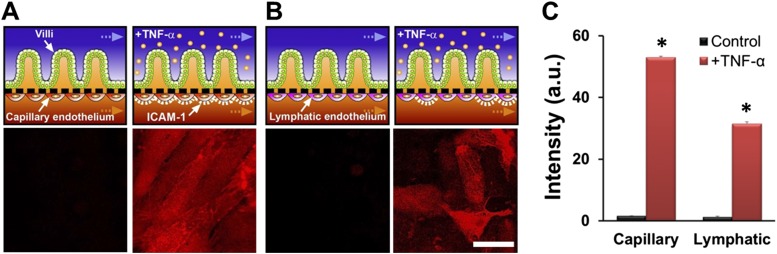

During inflammation in the intestine, pathophysiological recruitment of circulating immune cells is regulated via activation of the underlying vascular endothelium. To analyze this organ-level inflammatory response in our in vitro model, a monolayer of human microvascular endothelial cells (Fig. 3 C and D and Fig. S6 A and C) or lymphatic endothelial cells (Fig. S6 B and C) was cultured on the opposite (abluminal) side of the porous ECM-coated membrane in the lower microchannel of the device to effectively create a vascular channel (Fig. 3C). To induce intestinal inflammatory responses, LPS (Fig. 3 C and D) or TNF-α (Fig. S6) was flowed through the upper epithelial channel for 24 h, and then PBMCs were added to the vascular channel for 1 h without flow (Fig. 3 C and D). Treatment with both LPS (or TNF-α) and PBMCs resulted in the activation of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) expression on the surface of the endothelium (Fig. 3 C and D, Left, and Fig. S6) and a significant increase (P < 0.001) in the number of PBMCs that adhered to the surface of the capillary endothelium compared with controls (Fig. 3D). These results are consistent with our qPCR results, which also showed up-regulation of genes involved in immune cell trafficking (Fig. S5). Neither addition of LPS nor PBMCs alone was sufficient to induce ICAM-1 expression in these cells (Fig. 3D), which parallels the effects of LPS and PBMCs on epithelial production of inflammatory cytokines (Fig. 3A) as well as on villus injury (Fig. 2 B and D).

Fig. S6.

Responses of capillary or lymphatic endothelium to addition of the proinflammatory cytokine, TNF-α, into the lumen of the upper epithelial channel. Schematics (Top) and immunofluorescence confocal microscopic views (Bottom) show the organ-level tissue–tissue interface of intestinal villus epithelium and capillary endothelium (A) or lymphatic lacteal endothelium (B) cultured within the two adjacent microchannels in the gut-on-a-chip. Immunofluorescence staining for ICAM-1 revealed that epithelial stimulation with TNF-α (50 ng/mL) for 12 h induced endothelial activation and up-regulated expression of this surface adhesion receptor (red), which displayed a bright, uniform pattern of staining on the surface of the capillary endothelium (A, Right Bottom) and a more diffuse and punctate pattern on the lymphatic endothelium (B, Right Bottom). (Scale bar, 50 µm.) (C) Quantitation of the expression level of ICAM-1 on each endothelium (*P < 0.001; n = 50).

Evaluating Antiinflammatory Probiotic and Antibiotic Therapeutics On-Chip.

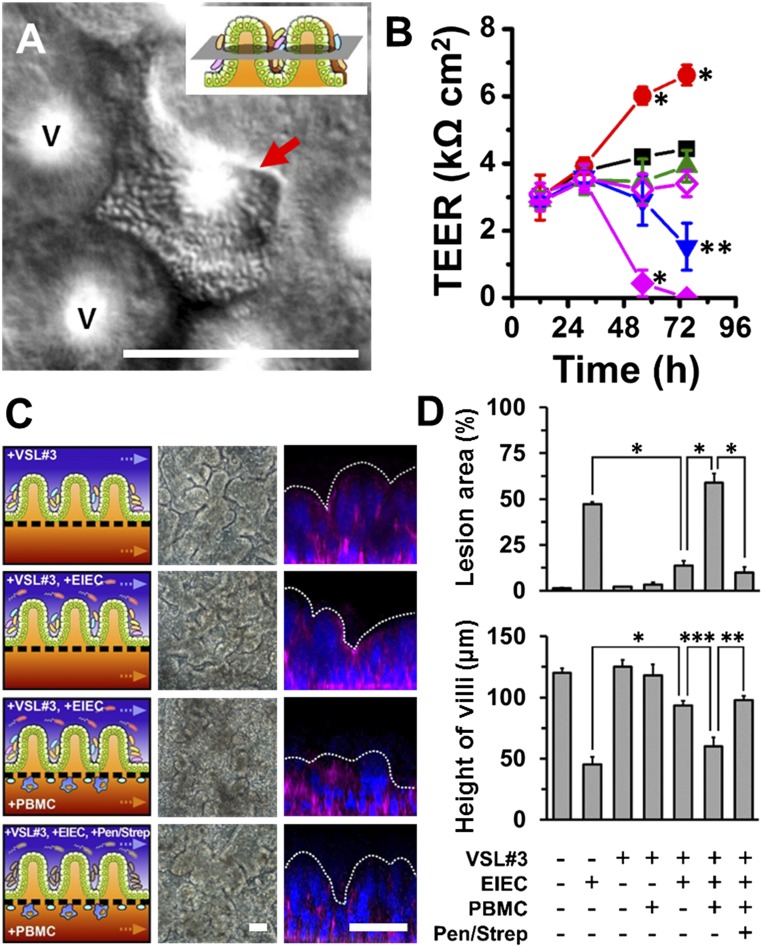

To investigate how the gut microbiome modulates these inflammatory reactions, we cocultured the human intestinal villi with the eight strains of probiotic bacteria in the VSL#3 formulation that significantly enhanced intestinal differentiation (Fig. 1E and Fig. S1B). To mimic the in vivo situation, we colonized our microengineered gut on a chip with the commensal microbes (VSL#3) first and then subsequently added immune cells (PBMCs), pathogenic bacteria (EIEC), or both in combination. The VSL#3 microbial cells inoculated into the germ-free lumen of the epithelial channel primarily grew as discrete microcolonies in the spaces between adjacent villi (Fig. 4A and Movie S3) for more than a week in culture (Fig. S7A), and no planktonic growth was detected. These microbes did not overgrow like the EIEC (Fig. 2A and Movie S2), although occasional microcolonies also appeared at different spatial locations in association with the tips of the villi (Fig. S7 B and C). The presence of these living components of the normal gut microbiome significantly enhanced (P < 0.001) intestinal barrier function, producing more than a 50% increase in TEER relative to control cultures (Fig. 4B) without altering villus morphology (Fig. 4C). This result is consistent with clinical studies suggesting that probiotics, including VSL#3, can significantly enhance intestinal barrier function in vivo (18).

Fig. 4.

Probiotic gut bacteria protect against EIEC-induced, immune cell-associated intestinal injury on-chip. (A) A DIC micrograph showing a viable microcolony of multispecies probiotic VSL#3 bacterial cells inhabiting the space between adjacent villi. V indicates the villi. (Inset) A schematic displaying the focal plane of the cross-sectional view. The image was recorded at 96 h after the VSL#3 cells were added to the villi. (B) Intestinal barrier function of control intestinal villus epithelium compared with epithelium exposed to probiotic VSL#3 bacteria alone (red circles) or to the copresence with EIEC (+VSL#3 +EIEC; blue inverted triangles), PBMCs (+VSL#3 +PBMC; green triangles), or both (+VSL#3 +EIEC +PBMC; filled magenta diamonds). Effect of the antibiotic mixture (100 units per mL penicillin and 100 µg/mL streptomycin) was tested before the addition of PBMCs (+VSL#3 +EIEC +Pen/Strep +PBMC; open magenta diamonds). We set onset time (at t = 0 h) when the VSL#3 cells were added; then EIEC, PBMCs, and antibiotics were added at 35 h, 45 h, and 44 h after onset, respectively. Asterisks indicate the statistical significance in each point compared with the control at the same time point (n = 4). (C) Morphological analysis of intestinal villus damage under the conditions described in Fig. 4B. The left, middle, and right columns show schematics, phase contrast images (taken at 57 h), and fluorescence confocal micrographs (vertical cross-sectional views) of villi recorded at 83 h after staining for F-actin (magenta) and nuclei (blue). (D) Quantification of intestinal injury evaluated by measuring changes in lesion area (Top; n = 30) and the height of the villi (Bottom; n = 50) in the absence or the presence of VSL#3, EIEC, PBMCs, or antibiotics, as indicated. Intestinal villi were grown for ∼100 h in the gut-on-a-chip with flow (40 µL/h) and cyclic deformation (10%, 0.15 Hz) before stimulation. *P < 0.001, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.05. (Scale bars, 50 µm.)

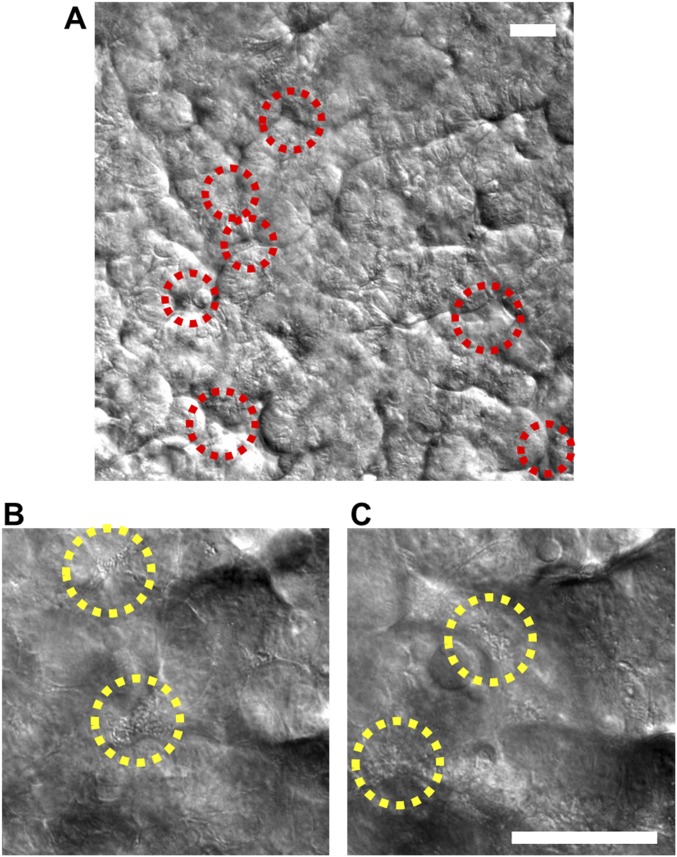

Fig. S7.

Stochastic microbial niche of VSL#3 microbial cells on the microengineered villi. (A) A DIC micrograph visualizing the long-term coculture of VSL#3 on the intestinal villi on-chip, here shown 8 d after seeding of the VSL#3 cells. Red dotted circles indicate the location of the microbial niches. Two representative DIC images at lower (B) and higher (C) Z-positions showing the presence of live bacterial microcolonies (yellow dotted circles) at different locations along the crypt-villus axis. (Scale bar, 50 µm.)

When the multispecies probiotic VSL#3 microbes were cocultured in the lumen of the epithelial channel, the devastating injury induced by EIEC infection (Fig. 2) was significantly reduced (P < 0.01), as evidenced by maintenance of high TEER values (>1,500 kΩ cm2) (Fig. 4B) and retention of villi with normal morphology (Fig. 4 C and D). Although the probiotic bacteria failed to completely prevent the intestinal damage induced by the EIEC infection in the presence of immune cells, the onset of intestinal injury was delayed by ∼18 h (Fig. 4 B–D) compared with addition of EIEC in the absence of VSL#3 microbes (Fig. 2 B–D). PBMCs also tolerated the presence of probiotic bacteria in the chip as intestinal barrier functions (Fig. 4 B and D) and tissue morphology (Fig. S8) remained unchanged when both were cocultured on-chip. However, the probiotic bacteria were not able to prevent intestinal injury when the epithelium was challenged simultaneously with both EIEC and PBMCs (Fig. 4 B–D). These findings are reminiscent of clinical findings with VSL#3 therapy, which suggest that it is most helpful in treatment of patients with ulcerative colitis during the early phase of the disease (27, 28).

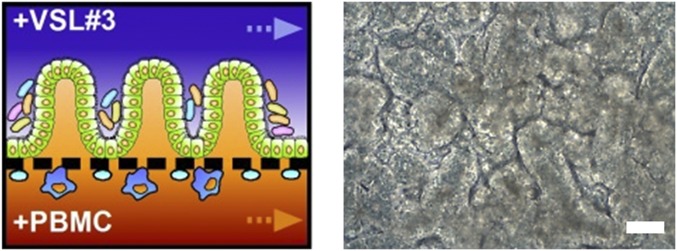

Fig. S8.

PBMCs alone do not cause pathological villus destruction during the coculture with commensal VSL#3 gut bacteria. A schematic of the experimental design (Left) and a representative phase contrast image (Right) showing that villi remained morphologically intact when precolonized with probiotic VSL#3 for 56 h and subsequently challenged to PBMCs for 40 h. (Scale bar, 50 µm.)

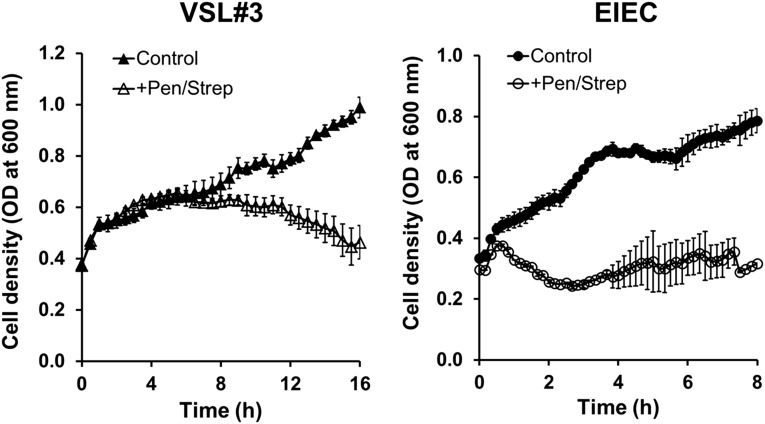

To mimic the effects of antibiotic therapies that are sometimes used clinically in patients with intestinal inflammatory disease (29), we identified a dose and combination of antibiotics (100 units per mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin) that produced effective killing of both EIEC and VSL#3 microbes in liquid cultures (Fig. S9) and then injected this drug mixture into the epithelial channel of gut-on-a-chip devices infected with EIEC. When we added PBMCs to these devices 1 h later, intestinal barrier function (Fig. 4B) and villus morphology (Fig. 4C) were largely protected from injury, and there was a significant reduction in lesion area (Fig. 4D). Thus, the gut-on-a-chip was able to mimic suppression of injury responses previously observed clinically using other antibiotics that produce similar bactericidal effects.

Fig. S9.

Graphs show that both VSL#3 (Left) and EIEC (Right) bacterial cells do not grow in the presence of antibiotics. Each bacterial strain was independently cultured in the cell culture medium (DMEM, 20% FBS) in the absence (Control; filled symbols) or the presence of a mixture of penicillin (100 units per mL) and streptomycin (100 µg/mL) (+Pen/Strep; open symbols). VSL#3 and EIEC cell densities were estimated by measuring optical density at 600 nm (n = 5).

Analyzing Mechanical Contributions to Bacterial Overgrowth.

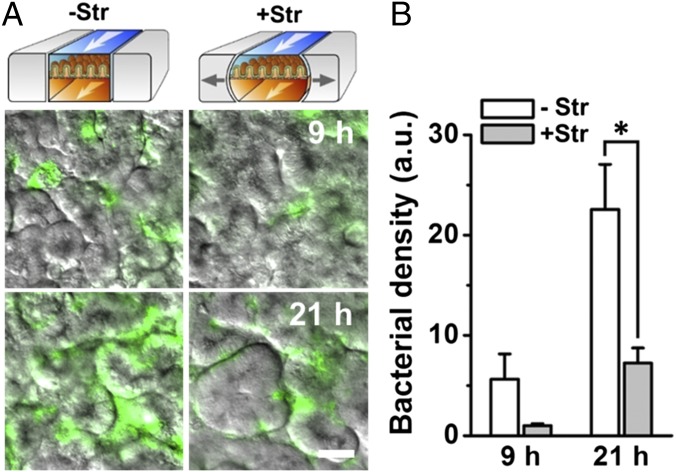

Finally, we used the gut-on-a-chip to analyze whether physical changes in peristalsis or villus motility contribute to intestinal pathologies, such as the small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) (5, 6) observed in patients with ileus (8) and IBD (7). When the GFP-EC bacteria were cultured on the villus epithelium under normal flow (30 µL/h), but in the absence of the physiological cyclic mechanical deformations, the number of colonized bacteria was significantly higher (P < 0.001) compared with gut chips that experienced mechanical deformations (Fig. 5A). Bacterial cell densities more than doubled within 21 h when cultured under conditions without cyclic stretching compared with gut chips that experienced physiological peristalsis-like mechanical motions, even though luminal flow was maintained constant (Fig. 5B). Thus, cessation of epithelial distortion appears to be sufficient to trigger bacterial overgrowth, and motility-induced luminal fluid flow is not the causative factor as assumed previously (7).

Fig. 5.

Bacterial overgrowth induced on-chip by cessation of peristalsis-like mechanical deformations. (A) Overlaid fluorescence and DIC microscopic views showing growth of GFP-EC (seeding density ∼1.0 × 107 cells per mL) on the intestinal villi in the gut-on-a-chip in the absence (−Str) or presence (+Str) of cyclic stretching motions (10% in cell strain, 0.15 Hz in frequency) after 9 h and 21 h of culture. (B) Bacterial density on villi measured by quantitating changes in the fluorescence intensity of GFP-EC in the absence (white) or presence (gray) of mechanical deformation. n = 10; *P < 0.001. (Scale bar, 50 µm.)

Discussion

One of the critical prerequisites for mimicking the living human intestine in vitro is to establish a stable ecosystem containing physiologically differentiated intestinal epithelium, gut bacteria, and immune cells that can be cultured for many days to weeks. Here we leveraged a mechanically active gut-on-a-chip microfluidic device to develop an in vitro model of human intestinal inflammation that permits stable long-term coculture of commensal microbes of the gut microbiome with intestinal epithelial cells. The synthetic model of the human living intestine we built recapitulated the minimal set of structures and functions necessary to mimic key features of human intestinal pathophysiology during chronic inflammation and bacterial overgrowth including epithelial and vascular inflammatory processes and destruction of intestinal villi.

Interest in the human gut microbiome is burgeoning because it has been implicated in control of intestinal homeostasis (30) and immune modulation (31), as well as in the pathogenesis of Crohn’s disease (32). The coculture method in the gut-on-a-chip described here enables stable host–microbe coexistence because of the presence of continuous fluid flow and peristalsis-like motions that enhance intestinal differentiation (33) and permit bacterial populations to reach a dynamic steady-state (12) that can be sustained over weeks in culture. In addition, the high level of mucus production on microengineered intestinal villi (16) also may provide a protective barrier to villus epithelium to maintain long-term stable coexistence with gut microbes.

One potential limitation of this model system is that the Caco-2 intestinal epithelial cells were originally isolated from a human colorectal tumor, although they were subsequently shown to exhibit features more similar to human small intestine (12, 16, 34). However, the key question in developing in vitro microphysiological systems is whether the method effectively recapitulates human organ physiology and whether it offers capabilities superior to other existing in vitro models. In our past studies, we showed that that Caco-2 cells retain stem cell-like functional capabilities in that they faithfully recreate intestinal villi that exhibit small intestinal villus morphology and functions observed in vivo (17). In the present study, transcriptome analyses clearly revealed that Caco-2 cells that form small intestinal villi in the gut-on-a-chip exhibit an entirely different phenotype compared with the same cells cultured in static Transwells, and additional coculture with commensal gut microbes pushed their level differentiation on-chip even further so that it more closely resembled that of normal human ileum. This finding is relevant because the ileum is the last segment of the small intestine where commensal gut microbes are much more abundant than in the proximal regions. In addition, these data indicate that coculture with normal commensal gut microbes has a significant normalizing effect on the differentiation state of the Caco-2 intestinal epithelial cells in the gut-on-a-chip model, even beyond that demonstrated in past publications (12, 16). Thus, we believe that this new method represents a significant leap forward relative to existing in vitro models of human intestinal inflammation.

Using this microdevice, we also discovered that immune cells must be present along with LPS or nonpathogenic bacteria to induce production of a key set of proinflammatory cytokines (IL-8, IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α) that act together to produce villus injury and intestinal barrier disruption. However, although our results confirm that IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α may contribute to development of intestinal inflammatory disease as suggested in the past based on in vivo studies (35), our ability to manipulate these factors independently revealed that these cytokines must act in the presence of high levels of IL-8 to exert these disease-promoting effects. This novel result would be difficult to detect using animal models.

We also studied the effects of PBMCs as way to mimic the effect of immune cell recruitment into the lamina propria, which is observed in chronic intestinal inflammation (13). PBMCs have been similarly used in many in vitro models of intestinal inflammation in the past because they can differentiate into intestinal tissue resident macrophages and dendritic cells (9, 23, 36). However, because the gut-on-a-chip is a synthetic system, it would be interesting to integrate other immune cells that contribute to maintenance of the immune milieu of the normal gut (e.g., gut-associated lymphoid tissue) in this model in the future.

The level of LPS found in the human intestine is generally considered harmless because the commensal Gram-negative gut microbiota routinely produce it, but it is at least partially inactivated by mammalian cell-derived acyloxyacyl hydrolase in vivo (37). Although an excessive amount of LPS was shown to produce acute intestinal inflammation in one mouse model (38), another study in mice with defects in macrophage function revealed that they failed to produce inflammatory cytokines when challenged with LPS, suggesting that immune cell function is critical in LPS-induced inflammation (24). To examine how immune cells alter responses to commensal Gram-negative bacteria and their products (i.e., LPS) during chronic inflammation, we cocultured PBMCs with a nonpathogenic laboratory strain of E. coli that produces only the core LPS (i.e., not long-chain LPS) (39). We confirmed that this nonpathogenic E. coli strain does not produce gut damage on its own. However, it did induce villus injury and compromise epithelial barrier function when PBMCs were present, suggesting that the inflammatory microenvironment does indeed sensitize the epithelial barrier to injury. Immune cells also were shown to stimulate greater increases in expression of IL-8 and other inflammatory cytokines compared with LPS alone in cultured human intestinal cells (23). Thus, our finding that immune cells must be present for LPS to produce intestinal inflammation in the human gut-on-a-chip both confirms prior work and provides additional evidence to show that LPS is not inducing injury on its own.

In addition, we showed that both inflammatory activation of the intestinal endothelium and associated surface adhesion of immune cells can be studied in this model. Because this human intestine model included both isolated immune cells and living gut microbiome, it also was able to mimic the destructive effects of pathogenic bacteria on intestinal villi in vitro and successfully replicate the protective effects of clinical probiotic and antibiotic therapies previously observed in IBD patients in vivo. Furthermore, among the 12 potential cytokines involved in human intestinal inflammation (40, 41) that we tested blindly in this study, a specific combination of 4 cytokines (IL-8, IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α) was discovered to be necessary and sufficient to induce villus injury in our model. Moreover, exposure of the epithelium to combinations of immune cells with either LPS or GFP-EC produced a similar injury response, which was also accompanied by increased production of this same set of cytokines. The same cytokines have been reported to be up-regulated in clinical studies of human inflammatory diseases, including in patients with active ulcerative colitis patients (41), Crohn’s disease (40), and pouchitis (42). Because intestinal macrophages capable of producing IL-8 are activated in IBD patients (43) and intestinal epithelial cells exposed to Gram-negative bacteria also produce this cytokine (23, 43), IL-8 has been implicated as a potential contributing factor in IBD as well. However, although our in vitro studies using a blocking antibody show that inhibition of IL-8 action completely prevents villus injury in the presence of all four cytokines, addition of IL-8 alone was not capable of inducing an injury response. Thus, apparently, IL-8 is only able to manifest its pivotal ability to compromise the intestinal barrier if it acts in an environment where IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α are also present. These observations raise the possibility that this particular combination of four cytokines and their receptors could be regarded as potential immunotherapeutic targets for a combination therapy to suppress inflammatory responses in patients with IBD. These types of mechanistic insights would have been extremely difficult to obtain using animal models.

Gene expression profiling revealed the huge extent of inflammatory changes that are induced in the human intestinal epithelial cells when challenged by LPS and immune cells in combination on-chip, as both proinflammatory and antiinflammatory processes became activated. For instance, there was a dramatic up-regulation of receptors for histamine (HRH1, HRH2, and HRH3) and leukotriene B4 (LTB4R and LTB4R2) that mediate immune cell recruitment (44, 45), which is consistent with our finding that these conditions stimulate ICAM-1 expression and immune cell recruitment, as well as with clinical reports that show high levels of both histamine and leukotriene B4 are routinely found in IBD patients (46). Early inflammatory signaling molecules, including prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2 (47) (PTGS2/COX-2), TNF receptors (48) (TNFRSF1A and TNFRSF1B), and phospholipase C enzymes (49) (PLCB3/4, PLCE1, and PLCG1/2) were up-regulated as well. However, at the same time, these cells increased expression of adrenergic receptors (50) (ADRB1 and ADRB2), annexin (51) (ANXA1 and ANXA3), and melanocortin neuropeptide receptor family member MC2R (52), which can suppress inflammatory reactions. These studies therefore suggest that the intestinal epithelial cell plays a central role in controlling both the dynamics and directionality of the inflammatory response.

Our experiments also showed that a therapeutic probiotic formulation (VSL#3) protects against the overgrowth of EIEC and subsequent gut injury. Although we did not analyze the population dynamics of individual species in this study, the maximum specific growth rates of Lactobacillus spp. (53), Bifidobacterium spp. (54), and Streptococcus sp. (55) are similar under high-nutrient conditions. Thus, it is unlikely that microbial species-level competition for nutrients significantly altered species diversity. One potential caveat, however, is that although the VSL#3 formulation contains multiple obligate or facultative anaerobic strains of commensal gut microbes, it is not fully representative of the highly complex commensal microbiome of the normal intestine. Although a positive effect of probiotic coculture on barrier function was demonstrated in past studies using static Transwells (56, 57), they were only able to perform the coculture for a short period (4–48 h). They also were not able to detect the important effect of mechanical deformation on bacterial overgrowth as we did in this study. We also found that the microbial cells predominantly colonized the intervillus spaces even though they were seeded uniformly. This may be because crevices between villi shelter these bacteria from fluid shear stress inside the microchannel, whereas bacteria positioned in regions above the tips of the villi will tend to be washed out from the device. In the confined intervillus space within a densely packed microchannel, facultative microbes may rapidly consume available oxygen, which would produce a local anoxic microenvironment that might support growth of nearby anaerobic microbes, even when the overall culture conditions are aerobic (5% CO2); this cannot be achieved in conventional 2D cell culture models. In contrast to VSL#3, the EIEC cells exhibited excessive overgrowth in the cultures. This might be because the pathogenic EIEC cells adhere more tightly to the epithelial surface or they create a more interconnected biofilm in this system. Overgrowth by the EIEC cells resulted in rapid injury of the epithelium, loss of normal villus morphology, and disruption of cell–cell junctions (Fig. 2A), likely from drastic nutrient depletion and waste accumulation. In contrast, the VSL#3 microcolonies remained limited to the spaces between villi that retained well-delineated epithelial cell borders when analyzed at up to 8 d of coculture. Taken together, these findings suggest that the gut-on-a-chip may be particularly useful for modeling SIBO given that bacterial overgrowth is currently assessed clinically by analyzing microbes in samples of small bowel fluid aspirates obtained by endoscopy (58).

Clinical and experimental studies suggest that antibiotic therapy can selectively decrease the invasion of pathogenic bacteria and broadly reduce luminal and mucosal bacterial densities in IBD patients (59). Our results showing that administration of a mixture of bactericidal antibiotics can suppress intestinal injury induced by pathogenic EIEC bacteria demonstrate that this form of adjuvant therapy can be studied in vitro using the gut-on-a-chip method. However, the antibiotics we used are different from those used most commonly in the clinic, and thus, the effects of different antibiotic therapies should be tested in future studies.

Finally, by leveraging the modular capability of gut-on-a-chip to vary mechanical parameters independently, we discovered that the loss of physiological mechanical deformation is itself sufficient to induce small intestinal bacterial overgrowth similar to that observed in some patients with ileus (8) as well as IBD (6, 7). In the case of ileus, which results from complete cessation of peristalsis (e.g., following surgery), the cause of bacterial overgrowth remains unknown. This is because although past in vivo studies suggested that it is caused by reduced movement of luminal contents due to compromised gut motility (8), inhibition of peristalsis also results in decreased mechanical deformation of the epithelium, which is known to have potent effects on cell function (60). Thus, our finding shifts the paradigm from current mechanistic models based on in vivo studies, which assume the cause of bacterial overgrowth to be slowing of luminal flow due to decreased motility that would concentrate bacterial populations. All of these discoveries were made possible by our ability to integrate and independently modulate different system parameters (e.g., peristalsis-like motions, presence of immune cells, and microbes) in the gut-on-a-chip, and it would be extremely difficult, if not impossible, to uncover these direct relationships using animal models or even human clinical studies.

Taken together, these results demonstrate that the human gut-on-a-chip offers a robust modular platform not only for analysis of intestine–microbiome interactions and interrogating etiology and development of human intestinal inflammatory diseases but also for defining potential therapeutic targets and testing drug candidates. Because all of the cellular components of the model can be varied independently, this microphysiological system could be improved further by incorporating primary or iPS cell-derived human intestinal epithelial cells, connective tissues, and various subsets of immune cells, as well as more complex commensal gut microbial communities (e.g., isolated from human IBD patients to model their specific contributions to intestinal inflammation in vitro). This potentially could be done in a patient-specific manner to advance personalized medicine in the future.

Materials and Methods

Device Microfabrication.

The gut-on-a-chip microdevice used in this study was fabricated from PDMS as reported previously (12, 16, 33). The dimensions of cell culture microchannel (1 mm wide × 10 mm long × 0.15 mm high) and vacuum chambers (1.68 mm × 9.09 mm × 0.15 mm) were the same in the upper and lower layers; the porous PDMS membrane contained an array of circular holes (10 µm diameter × 20 µm high with 25 µm spacing). Gas-permeable silicone tubing (Tygon 3350, ID 1/32″, OD 3/32″) with a connector (hub-free stainless steel blunt needle, 18G; Kimble Chase) was connected into each microchannel to supply cell culture medium and vacuum suction.

Microfluidic Culture.

Caco-2BBE human colorectal carcinoma-derived (Caco-2) intestinal epithelial cells (obtained from Harvard Digestive Disease Center) were cultured on the upper surface of the ECM-coated, flexible, porous membrane in the gut-on-a-chip device, with culture medium (DMEM, 20% FBS, antibiotics) being perfused constantly (30 μL/h; 0.02 dyne/cm2) and exposed to cyclic mechanical deformation (10% strain, 0.15 Hz); the Caco-2 cells spontaneously formed villi after ∼100 h of culture. To model inflammatory activation, human capillary endothelial cells or human lymphatic microvascular endothelial cells were cocultured on the opposite side of the porous ECM-coated membrane in the presence of flowing (30 μL/h) coculture medium with cyclic mechanical deformations (10%, 0.15 Hz). To study inflammatory activation of the endothelium, LPS (15 µg/mL) and PBMCs (3.3 × 106 cells per mL) were introduced into the upper and lower microchannels, respectively. For host–microbe coculture, villi grown in a gut-on-a-chip device were preconditioned in antibiotic-free culture medium for 12 h before microbial cells (VSL#3, GFP-EC, or EIEC) suspended in an antibiotic-free cell culture medium were introduced into the upper microchannel. The microbes and cells were then incubated without flow for 1.5 h before flow (40 µL/h) and mechanical deformations (10%, 0.15 Hz) were resumed to establish a stable host–microbe ecosystem. PBMCs were isolated from human blood drawn from healthy volunteers using a ficoll gradient. Blood collection procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Harvard University Faculty of Medicine.

Transcriptome Analysis.

Gene expression profiling of Caco-2 cells cultured in static or microfluidic conditions was carried out using Human Genome 1.0 ST Affymetrix GeneChip arrays. Gene expression data for normal human small intestine (duodenum, jejunum, and ileum) were obtained from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database. Transcriptome profiles of Caco-2 cells performed in this study were deposited to the NCBI GEO database (accession no. GSE65790). Global gene expression profiles were also visually represented using self-organizing maps generated using the Gene Expression Dynamics Inspector (GEDI) program (19).

Morphological Analysis.

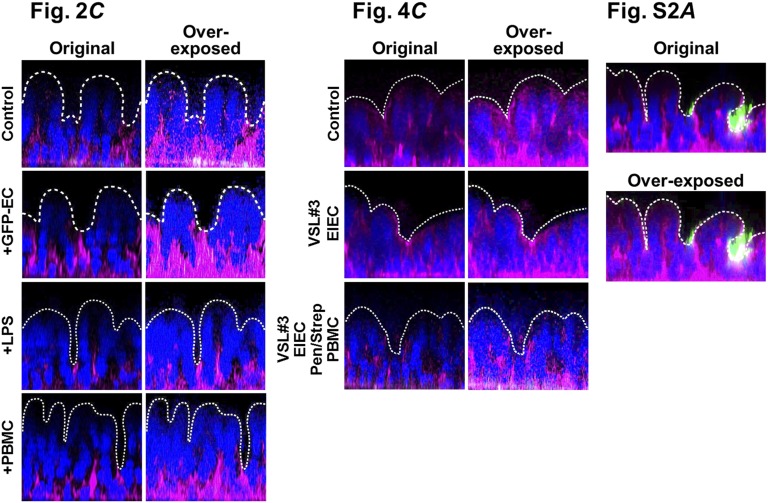

Images of the intestinal villus morphology were recorded by using phase contrast or differential interface contrast (DIC) microscopy (Zeiss). The villus microarchitecture was also visualized using immunofluorescence microscopy with a laser scanning confocal microscope (Leica). Acquired images were processed using MetaMorph (Molecular Devices), AutoQuant X (Media Cybernetics Inc.), IMARIS (Bitplane Scientific Software), ImageJ, or ZEN Pro image (Zeiss) acquisition software (Fig. S10).

Fig. S10.

Identification of the contours of apical surface of the villus epithelia presented in Figs. 2C and 4C and Fig. S2A. Each fluorescence image highlighting nuclei (blue) and F-actin (magenta) was overexposed to identify the entire cell mass and the upper boundary of the villi. Then its position was indicated with a white dotted line in the same position on the final normally exposed images.

Statistical Analysis.

All results and error bars in this article are represented as mean ± SE (SEM). For statistical analyses, a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey–Kramer multiple comparisons test was performed. Differences between groups were considered statistically significant when P < 0.05.

See SI Text for materials, more detailed procedures, and additional data.

SI Text

Cell Culture.

The Caco-2BBE human colorectal carcinoma (Caco-2) cell line was used as a source of human intestinal epithelial cells (Harvard Digestive Disease Center). The cells were grown in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM; Gibco) containing 4.5 g/L glucose and 25 mM Hepes with 20% (vol/vol) FBS (Gibco), 100 units per mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (Pen/Strep; Gibco) at 37 °C in a humidified incubator under 5% CO2 in air. Before cell seeding, the gut-on-a-chip microdevice was sterilized by flowing 70% (vol/vol) ethanol through the channels, drying the devices in a 60 °C oven, and then exposing them to UV light and ozone simultaneously (UVO Cleaner 342; Jelight Company Inc.) for 40 min. After the surfaces of the microchannels were coated with type I collagen (50 μg/mL; Gibco) and Matrigel (300 µg/mL; BD Biosciences) in the serum-free DMEM for 2 h, the Caco-2 cell suspension (∼1.5 × 105 cells per cm2) was introduced into the upper microchannel. After being allowed to adhere to the ECM-coated substrate for 1 h, fresh culture medium was flowed through the upper channel at 30 µL/h (0.02 dyne/cm2) for the first day of culture to establish a compact monolayer; thereafter, culture medium was perfused to both the upper and lower microchannels at the same flow rate. To exert peristalsis-like mechanical deformations on the cell monolayer, cyclic stretching motions (10% mean cell strain at 0.15 Hz frequency) were applied by connecting vacuum chambers to a vacuum controller (FX5K Tension instrument; Flexcell International Corporation). The Caco-2 cells spontaneously formed villi after being exposed to these culture conditions for ∼100 h.

Bacterial Cell Culture.

All of the microbial species were precultured in vitro with appropriate microbial culture medium at each culture condition, then adjusted to the optimized cell density in antibiotic-free culture medium [DMEM, 20% (vol/vol) FBS]. The VSL#3 formulation (Sigma-Tau Pharmaceuticals, Inc.) contains eight facultative or obligate, anaerobic, probiotic strains including L. acidophilus, L. plantarum, L. paracasei, Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus, B. breve, B. longum, B. infantis, and Streptococcus thermophilus. For the precultivation of VSL#3 strains, freeze-dried VSL#3 powder was resuspended in the mixture of sterilized Lactobacilli MRS Broth (Difco; BD Diagnostics) and Reinforced Clostridial Medium (Difco; BD) (1:1, vol/vol). After cell density was adjusted to ∼0.2 OD units (at 600 nm), VSL#3 cells were cultivated in an anaerobic container containing an anaerobic gas generating sachet (GasPak EZ Anaerobe Container System with Indicator; BD) without shaking at 37 °C, 5% CO2 conditioned incubator for 12 h. The VSL#3 bacterial cells in culture broth were spun down (10,000 × g, 5 min), resuspended in antibiotic-free DMEM (cell density, ∼1.0 × 107 CFU/mL), and then immediately flowed into the upper microchannel containing the villus epithelium preconditioned in antibiotic-free culture medium for 12 h. After VSL#3 bacterial cells were allowed to attach to the surface of epithelium for ∼1.5 h without medium flow, fresh antibiotic-free culture medium was perfused into both upper and lower microchannels at 40 µL/h with cyclic mechanical stretching motions (10%, 0.15 Hz). In Fig. 4A, the array of glowing white circles are the pores engineered into the culture membrane beneath the epithelium. Nonpathogenic DH5-Alpha E. coli constitutively expressing green fluorescence protein (GFP) and pathogenic enteroinvasive E. coli (EIEC; serotype O124:NM, ATCC 43893) were separately cultivated in autoclaved LB medium at 37 °C with shaking motions (200 rpm) for 12 h. After bacterial cell density was adjusted at ∼1.0 × 107 CFU/mL, they were introduced into the upper epithelium-lined channel of the gut-on-a-chip as described above.

To evaluate the effect of cyclic mechanical deformations on bacterial colonization, GFP-EC grown in LB medium were washed with PBS, resuspended in the prewarmed antibiotic-free DMEM (cell density, ∼1.0 × 107 CFU/mL), and then introduced into the upper epithelium-lined channel of the gut-on-a-chip after the cells were cultured for ∼100 h and villi had formed. After the attachment of the GFP-EC under static conditions (without flow) at 37 °C under 5% CO2 for 1.5 h, medium was restored to 40 µL/h for 24 h. The control cultures were stimulated by applying 10% cyclic strain at 0.15 Hz, whereas the experimental group had no mechanical stimulation. Images were recorded using differential interface contrast (DIC) microscopy and epifluorescence microscopy (GFP filter, Ex 475–495 nm/Em 500–550 nm; Axio Observer.Z1, Zeiss) using a 20× objective (LD PlnN, 0.4 DICII) and a digital camera (EM-CCD C9100; Hamamatsu) and MetaMorph software (Molecular Devices, LLC) at 10 different positions in each device at 9 h and 21 h, respectively. The DIC and fluorescence images recorded at each location were then overlaid to visualize the position of the GFP-EC colonies relative to the intestinal villi. Microfluorimetric quantitation of GFP levels was used to estimate bacterial densities at 9 h and 21 h of culture.

To measure effects of antibiotics on bacterial growth (Fig. S9), EIEC and VLS#3 that were cultured as described were washed with PBS and then inoculated into either control or antibiotic-containing culture medium (+Pen/Strep) in a clear-bottom black 96-well plate (BD). The well plate containing VSL#3 cells was tightly sealed with a laboratory film (Parafilm; Pechiney Plastic Packaging) and then incubated in a microplate reader (SpectraMax M5; Molecular Devices) at 37 °C without shaking. To quantitate the growth of VSL#3 cells, optical density was measured at 600 nm every 30 min for 16 h. EIEC growth analysis was carried out the same way, except that the plate was incubated in a microplate reader at 37 °C in the shaking mode (100 rpm), and the optical density at 600 nm was constantly recorded every 20 min for 8 h (n = 5).

Inflammation Study.

To mimic the chronically inflamed microenvironment of patients with intestinal inflammatory diseases where increased numbers of immune cells are recruited from the lamina propria, microengineered intestinal villi grown in a gut-on-a-chip microdevice (30 µL/h, 10%, 0.15 Hz, ∼100 h) were challenged to GFP-EC, pathogenic EIEC, or lipopolysaccharide endotoxin (LPS) that are introduced into the upper lumen microchannel. Next, peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs; 3.3 × 106 cells per mL; SI Text, Human Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells Isolation) isolated from fresh human blood were introduced into the lower microchannel, and then the device setup was flipped over to allow PBMCs to adhere to the surface of an ECM-coated porous membrane. After 2 h of incubation, the device setup was flipped over again, and then the fresh culture medium resumed flowing at 30 µL/h with 10% cyclic stretching motions (0.15 Hz).

In studies examining the effect of probiotic commensal microbes, we add the VSL#3 cells into the lumen of the upper microchannel after the intestinal epithelial cells were cultured on-chip under fluid shear stress (0.02 dyne/cm2) and mechanical deformation (10%, 0.15 Hz) for ∼100 h, after well-developed villi had formed. We attempted to mimic the in vivo situation by colonizing our microengineered gut-on-a-chip by adding commensal microbes (VSL#3) first and then subsequently adding immune cells, pathogenic bacteria, or combinations of both. The time that the VSL#3 were added is indicated as the onset time (t = 0 h) in Fig. 4B; the EIEC bacteria were added at t = 35 h, and cultures were maintained for at least 48 additional hours; the PBMCs were added at t = 45 h, and antibiotics were added at 44 h.

To model inflammatory activation of vascular and lymphatic endothelium in the gut-on-a-chip, normal human capillary microvascular endothelial cells (capillary HMVECs; Lonza) or human lymphatic microvascular endothelial cells (lymphatic HMVECs; Lonza) were cocultured on the opposite side of the porous ECM-coated membrane from the intestinal epithelial cells. After intestinal villi were allowed to begin to form at ∼72 h, culture medium was switched to the coculture medium, a mixture [(2:8 (vol/vol)] of the epithelial medium (DMEM/20% FBS/antibiotics) and endothelial media [EBM-2 basal medium containing hEGF, hydrocortisone, GA-1000 (gentamicin, amphotericin-B), FBS, VEGF, hFGF-B, R3-IGF1, and ascorbic acid; Lonza] for 12 h before seeding the endothelial cells on the opposite side of the porous membrane in the lower channel. Capillary or lymphatic HMVECs were disassociated with Trypsin/EDTA solution (0.05% wt/vol; Gibco), washed with PBS, and resuspended in the coculture medium (∼5.0 × 105 cells per cm2) after centrifugation (500 × g, 5 min). After the gut-on-a-chip microdevice containing villi was moved into a biosafety cabinet, cell suspension of HMVECs contained in a syringe (1 mL Tuberculin slip tip, sterile; BD) equipped with a needle (25G 5/8; BD) was slowly infused into the lower microchannel. To prevent the damage of the villus epithelial layer caused by the hydrostatic pressure during the endothelial cell seeding, tubes connected to the inlet and outlet of the upper microchannel were clamped before seeding the endothelial cells. After the HMVECs were introduced into the lower microchannel, the clamp was released from the tubing connected to the lower microchannel, and the whole gut-on-a-chip device was flipped upside down and placed in an incubator (37 °C, humidified, 5% CO2) for ∼1.5 h to facilitate HMVEC attachment onto the surface of the porous membrane in the lower microchannel. After the cells adhered, the device was flipped over again, and coculture medium was perfused at 30 µL/h to both upper and lower microchannels with mechanical stretching (10%, 0.15 Hz) for at least 3 d before use. To study inflammatory activation of the endothelium, LPS (15 µg/mL) and PBMCs (3.3 × 106 cells per mL) were introduced into the upper and lower microchannels, respectively. Controls included addition of LPS alone, PBMCs alone, or neither. The pores in the membrane in Fig. 3C appear as a regular array of dark circles surrounded by ICAM-1 staining in Fig. 3C, Bottom Right.

To estimate the number of PBMCs adhered to the surface of the activated endothelium, PBMCs isolated from fresh blood were incubated in coculture medium containing Calcein AM (5 µM, final concentration; Invitrogen) in the humidified CO2 incubator for 30 min at 37 °C and then introduced into the lower microchannel. The device was flipped upside down (lower channel on top) for 1 h without flow, and then it was flipped back again to assess the number of adhered PBMC. After unbound PBMCs in the lower microchannel were washed with culture medium at a high (300 µL/h; 10× higher than normal) flow rate for 30 min, the adherent fluorescently labeled PBMCs were counted under the confocal microscope (Leica).

Human Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells Isolation.

PBMCs were isolated from fresh citrate-anticoagulated human blood drawn from healthy volunteers using a ficoll gradient. Blood collection procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Harvard University Faculty of Medicine. The buffy coat containing PBMCs was washed with PBS containing 10% (vol/vol) FBS three times using centrifugation (250 × g, 10 min) and aspiration and then adjusted to the final cell density (3.3 × 106 cells per mL) in the epithelial cell culture medium before being infused into the lower capillary channel of the device.

Transcriptome Analysis.

Gene expression profiling was carried out using Human Genome 1.0 ST Affymetrix GeneChip arrays. In brief, total RNA was extracted from cells with the RNAeasy kit including DNase digestion (Qiagen). Biotin-labeled cDNA was obtained from 1 µg of total RNA with the GeneChip OneCycle labeling kit (Affymetrix). The cDNA (1.5 µg) was fragmented and hybridized to Affymetrix Human Genome 1.0 ST Affymetrix GeneChip arrays according to the manufacturer’s protocol. DNA chips were washed, stained, and scanned using an Affymetrix Fluidics device and a GCS3000 scanner, and the images obtained were analyzed using GCOS software. Experiments were performed with biological duplicate for the Caco-2 cells cultured either in static Transwell or in the gut-on-a-chip with flow and cyclic peristalsis-like motions, in the presence or absence of VSL#3 probiotic bacteria. Data normalization was calculated with the robust multichip average (RMA) algorithm (61) implemented in BioConductor. The cluster analysis was performed and the plots were generated using R packages. Human Gene 1.0 ST Array mRNA data of Caco-2 cells cultured in various conditions were deposited to the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (accession no. GSE65790).

To compare transcriptome profiles between in vitro cultures of Caco-2 cells versus samples of different regions of human small intestine, we obtained gene expression data for normal human duodenum (GSM175908, GSM175947, GSM175949, and GSM463933), jejunum (GSM175982, GSM176265, GSM176266, GSM750891, and GSM750892), and ileum (GSM242031, GSM242032, GSM242033, GSM750888, GSM750889, and GSM750890) from the GEO database. All of the raw .cel files were imported into R software and subjected to RMA normalization using the Bioconductor Oligo R-package (v3.0). Comparison between results obtained with the human tissue microarray data sets (HG U133 Plus 2.0) and our microarrays (HG 1.0ST) obtained in-house using samples from Transwell or gut-on-a-chip cultures were made based on common identifiers using the Affymetrix HG-U133 Plus to Human Gene 1.0 ST, Good Match translation table. Probes that could not be matched were dropped, resulting in 29,469 (of 29,480) common probes for comparisons. Batch correction was performed using the sva package, and batch effects occurring within replicate groups were removed using ComBat (62). Normalized, batch-corrected data were then merged into a single dataset, and averages were calculated across all replicates. Clustering on Euclidean distance with complete linkage was performed in R (3.1.2) using the pvclust package (v1.3.2) for assessing uncertainty in hierarchical cluster analysis. Pearson correlation analysis was performed with MATLAB corr function for calculating the pairwise linear correlation coefficient between each pair of samples (22,097 probes). It produces a matrix of P values for testing the hypothesis of no correlation against the alternative that there is a nonzero correlation.

Global gene expression profiles were visually represented using self-organizing maps that were generated using the GEDI program (19). In GEDI, each pixel tile within a mosaic represents a minicluster of genes that have highly similar expression patterns across all analyzed samples. The same genes are forced to the same mosaic position for all GEDI maps, hence allowing direct comparison of transcriptomes based on the overall mosaic pattern. The color of tiles indicates the centroid value of gene expression level for each minicluster.

Epithelial Barrier Measurements.

The integrity of the tight junction barrier of the intestinal epithelium was evaluated by measuring TEER. Briefly, two Ag/AgCl electrode wires (0.008″ in diameter; A-M systems, Inc.) were applied to the tubing linked to the upper or the lower microchannel, and the resistance value of epithelial layer was recorded using a voltage-ohm meter (87V Industrial Multimeter; Fluke Corporation). An empty gut-on-a-chip microdevice filled with culture medium was used to normalize for baseline resistance. The final TEER values were determined by multiplying the normalized resistance value (Ω) times the total cell culture surface area (cm2) available on the porous PDMS membrane (n = 4).

Cytokine-Induced Villus Injury.

To study villus disruption induced by cytokines identified in our analysis, four human recombinant cytokines, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α (R&D Systems), were dissolved in prewarmed cell culture medium at 3, 5, 15, and 4 ng/mL, respectively. Test medium containing different combinations of four cytokines was then flowed through the upper microchannel of the gut-on-a-chip at 30 µL/h with cyclic mechanical strain (10%, 0.15 Hz) for 48 h. In some studies, anti-IL-8 monoclonal blocking antibodies (50 µg/mL; R&D Systems) were added in the test medium containing four cytokines and then flowed to the intestinal lumen of the chip under the same culture conditions.

Morphological Analysis.

Images of the epithelium were recorded by the phase contrast microscopy (Axiovert 40CFL; Zeiss) equipped with a 20× objective (0.30 Ph1; Zeiss) and a Moticam 2500 camera (Motic China Group Co., Ltd.) and imaging software (Motic images plus 2.0) or using a DIC microscope (Axio Observer.Z1; Zeiss) coupled to a 20× objective (LD PlnN, 0.4 DICII; Zeiss) and a digital camera (1,000 × 1,000 eight-micrometer pixels, EM-CCD C9100; Hamamatsu) and either MetaMorph software (Molecular Devices) or ZEN Pro image acquisition software (Zeiss). Images of villi were recorded at more than 10 different locations from at least two independent gut-on-a-chip replicates at each time point, and representative images are included in the figures (Figs. 1C, 2 A and C, 3B, 4 A and C, and 5A and Figs. S4 C and D, S7, and S8). The villus architecture of the epithelium was also visualized using immunofluorescence microscopy with a laser scanning confocal microscope (Leica SP5 X MP DMI-6000) using a 25× water immersion objective (NA 0.95) linked to a 405-nm diode laser, a white light laser (489–670 nm), or an argon laser (488 nm and 496 nm) and coupled to a photomultiplier tube or HyD detectors. Single-plane or multiplane Z-stacked confocal fluorescence images were analyzed by Leica imaging software (LAS AF Ver. 2.3.1 build 5194; Leica Microsystems CMS GmbH). To obtain high-resolution horizontal or vertical cross-sectional views, deconvolution (AutoQuant X, Version ×3.0.1; Media Cybernetics Inc.) followed by a 2D projection process (IMARIS 7.6 F1 workstation; Bitplane Scientific Software) were routinely performed on Z-stacked confocal fluorescence images. The contours of the apical surfaces of the intestinal villi were identified by overexposing DAPI-stained images (Fig. S10) and then indicating the positions of the intestinal villi using dashed lines on the normally exposed images that were included in Figs. 2C and 4C and Fig. S2A.