Significance

Blue light and temperature are two key environmental signals that profoundly affect plant growth and development responses, but how these two abiotic factors integrate remains largely unknown. This study demonstrates a mechanism of multiple photoreceptors and temperature coactions. Arabidopsis blue light photoreceptor cryptochrome 1 (CRY1) represses high temperature-induced hypocotyl elongation through PHYTOCHROME-INTERACTING FACTOR 4 (PIF4). CRY1 physically interacts with PIF4 in a blue light-dependent manner to repress the transcription activity of PIF4. Because PIF4 also plays a role in ambient temperature, PIF4 appears to be the molecular basis of cross-talk among blue and red light and ambient temperature signal pathways.

Keywords: blue light, cryptochrome, PIF4, hypocotyl elongation, ambient temperature

Abstract

Cryptochrome 1 (CRY1) is a blue light receptor that mediates primarily blue-light inhibition of hypocotyl elongation. Very little is known of the mechanisms by which CRY1 affects growth. Blue light and temperature are two key environmental signals that profoundly affect plant growth and development, but how these two abiotic factors integrate remains largely unknown. Here, we show that blue light represses high temperature-mediated hypocotyl elongation via CRY1. Furthermore, CRY1 interacts directly with PHYTOCHROME-INTERACTING FACTOR 4 (PIF4) in a blue light-dependent manner to repress the transcription activity of PIF4. CRY1 represses auxin biosynthesis in response to elevated temperature through PIF4. Our results indicate that CRY1 signal by modulating PIF4 activity, and that multiple plant photoreceptors [CRY1 and PHYTOCHROME B (PHYB)] and ambient temperature can mediate morphological responses through the same signaling component—PIF4.

Cryptochromes are photolyase-like blue-light receptors first discovered in Arabidopsis and later found in all major evolutionary lineages (1–4). Arabidopsis cryptochrome 1 (CRY1) and cryptochrome 2 (CRY2) mediate primarily blue-light inhibition of hypocotyl elongation (5) and photoperiodic control of floral initiation (6) via modulation of gene expression. For example, Arabidopsis CRY2 undergoes blue light-dependent interaction with CIB1 (CRY2 Interacting bHLH1) to regulate flowering time (7–9). CRYs also suppress the E3 ubiquitin ligase activity of COP1 (CONSTITUTIVE PHOTOMORPHOGENIC 1) by forming a complex with SPA1 (SUPPRESSOR OF PHYA-105) and COP1 in a blue light-dependent manner (10–13). COP1 is a RING finger E3 ubiquitin ligase that acts downstream of phytochromes, cryptochromes, and UVR8 (UV Resistance Locus 8) (14, 15) and is responsible for the degradation of various transcription factors in the dark, such as the bHLH transcription factor HFR1 (LONG HYPOCOTYL IN FAR RED1) and the bZIP factor HY5 (12, 16–18). Whether Arabidopsis CRY1 undergoes blue light-dependent interaction with transcription factors to regulate hypocotyl elongation is still unknown.

In addition to light, ambient temperature serves as another key environmental cue that affects plant growth and development, but does not induce stress responses to any significant degree (19). Temperature regulates gene expression via chromatin remodeling and also regulation of transcription. It has been demonstrated that H2A.Z histone variant-containing nucleosomes act as thermosensors and mediate temperature induced transcriptome changes (20). PHYTOCHROME-INTERACTING FACTOR 4 (PIF4) is a bHLH transcription factor directly link red light photoreceptor PHYTOCHROME B (PHYB) to light-regulated gene expression and plant development (21–23). PIF4 also plays a role in sensing high temperature, it not only regulates temperature-mediated floral induction in the short day condition through direct activation of FT (FLOWERING LOCUS T) (24), but it also controls high temperature-induced hypocotyl elongation by increasing free indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) concentrations via direct stimulation of YUC8 (YUCCA8) or TAA1 (TRYPTOPHAN AMINOTRANSFERASE OF ARABIDOPSIS) gene expression (25–32).

It was previously reported that red light response was strictly temperature dependent, it promoted hypocotyl extension at 27 °C, whereas repressed hypocotyl elongation at 17 °C or 22 °C (33), but how about blue light? Here, we show that blue light inhibits hypocotyl elongation at both 22 °C and 28 °C, and it represses high temperature-induced hypocotyl elongation through CRY1. More importantly, CRY1 physically interacts with PIF4 in a blue light-dependent manner in plants, to regulate the biosynthesis of auxin in response to elevated ambient temperature. We also show that CRY1 and PIF4 occupy the same promoter regions to repress the transcription activity of PIF4, indicating that CRY1 signal by regulating PIF4 activity. Because PIF4 binds to CRY1 and PHYB to transduce both blue and red light signals, it appears to be the molecular basis for cross-talk between CRY1 and PHYB. Blue light and temperature may also integrate by regulating PIF4.

Results

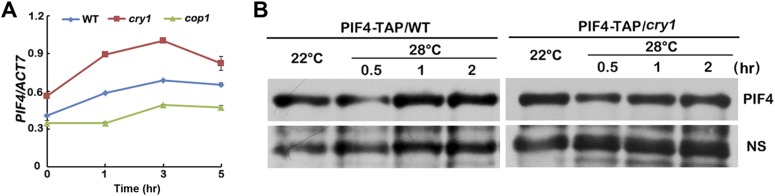

Blue Light Regulates the High Temperature-Mediated Hypocotyl Elongation via CRY1.

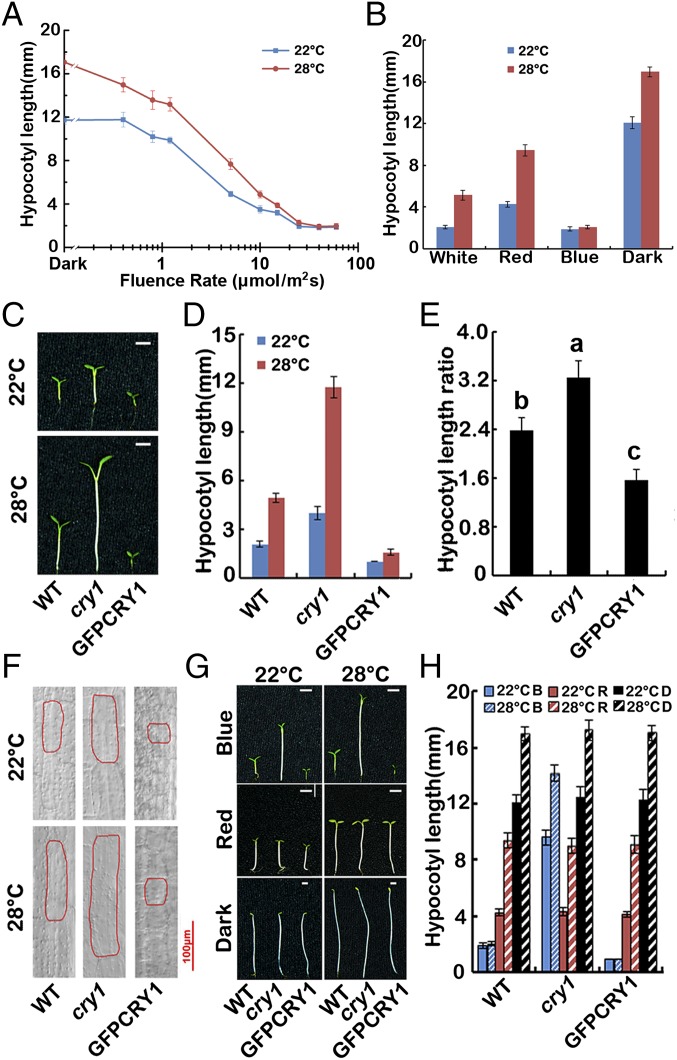

Unlike red light, all fluence rates of blue light tested repressed hypocotyl extension at both 22 °C and 28 °C (Fig. 1A). Furthermore, hypocotyl elongation of WT seedlings in response to elevated temperatures was repressed under blue light conditions, compared with dark, red light, and white light conditions (Fig. 1 A and B and Fig. S1A), indicating that blue light negatively regulates thermomorphogenesis.

Fig. 1.

Blue light inhibits high temperature-induced hypocotyl elongation via CRY1. (A) Fluence rate response curves measuring hypocotyl elongation of 4-d-old WT seedlings grown in continuous blue light at 22 °C and 28 °C. (B) A phenotypic analysis. Seedlings of the wild genotype were grown under continuous white light, red light, blue light (all 40 μmol⋅m−2⋅sec−1) or dark conditions in 22 °C or 28 °C for 4 d. The hypocotyl lengths were measured and are shown. (C–E) A phenotypic analysis. Seedlings of the indicated genotypes were grown under continuous white light at 22 °C or 28 °C for 4 d. Images of the representative seedlings are shown in C, and the hypocotyl lengths of the indicated genotypes were measured and are shown in D. Hypocotyl length ratios (28 °C/22 °C) of the quantified hypocotyl length in D are shown in E. The letters “a” to “c” indicate statistically significant differences between ratios for hypocotyl of the indicated genotypes, as determined by Tukey’s least significant difference (LSD) test (P ≤ 0.01). (F) Cell morphologies of representative seedlings of the indicated genotypes. (G and H) A phenotypic analysis in different light conditions. Seedlings of the indicated genotypes were grown at 22 °C or 28 °C in the dark or continuous blue or red light (40 μmol⋅m−2⋅sec−1) for 4 d. Images of the representative seedlings are shown in G, and the hypocotyl lengths of the indicated genotypes were measured and are shown in H. SDs (n > 15) are indicated.

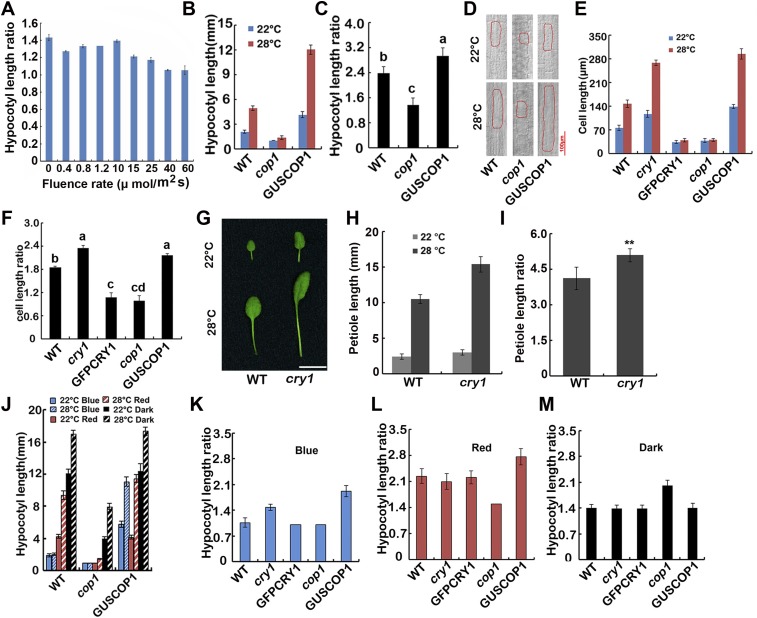

Fig. S1.

CRY1 inhibits high temperature-promoted hypocotyl and petiole extension in a blue light-dependent manner. (A) Hypocotyl length ratios (28 °C/22 °C) of the quantified hypocotyl length showed in Fig. 1A. (B and C) A phenotypic analysis. Seedlings of the indicated genotypes were grown under continuous white light at 22 °C or 28 °C for 4 d. The hypocotyl lengths of the indicated genotypes were measured and are shown in B. Hypocotyl length ratios (28 °C/22 °C) of the quantified hypocotyl length in B are shown in C. The letters “a” to “c” indicate statistically significant differences between ratios for hypocotyl of the indicated genotypes, as determined by Tukey’s LSD test (P ≤ 0.01). (D) Cell morphologies of representative seedlings of the indicated genotypes. (E) Quantifications of cell lengths shown in Fig. 1F and Fig. S1D. SDs (n > 15) are indicated. Cell length ratios (28 °C/22 °C) of the quantified cell length in E are shown in F. The letters “a” to “d” indicate statistically significant differences between ratios for cell length of the indicated genotypes, as determined by Tukey’s LSD test (P ≤ 0.01). (G–I) A phenotypic analysis showing that the petiole length of cry1 elongated more than WT in response to elevated temperature. Plants of the indicated genotypes were grown under continues white light condition in 22 °C or 28 °C for 3 wk. Images of the representative leaf petioles are shown in G. (Scale bar: 10 mm.) The petiole lengths of the indicated genotypes were measured and are shown in H. Petiole length ratios (28 °C/22 °C) of the quantified petiole length in H are shown in I. Asterisks represent a significant difference from the WT with Student’s t test (P ≤ 0.01). (J) A phenotypic analysis in different light conditions. Seedlings of the indicated genotypes were grown at 22 °C or 28 °C in the dark or continuous blue or red light (40 μmol⋅m−2⋅sec−1) for 4 d. The hypocotyl lengths of the indicated genotypes were measured and are shown. SDs (n > 15) are indicated. (K–M) Hypocotyl length ratios (28 °C/22 °C) of the quantified hypocotyl length showed in Fig. 1H and Fig. S1J. SDs are indicated.

CRY1 plays an important role in the inhibition of hypocotyl elongation in response to blue light. It has been shown that blue light and CRYs are required for temperature compensation of the circadian clock (34) and that HFR1 control of hypocotyl growth was temperature dependent in blue light, and proposed that PhyB and CRY1 were critical for controlling growth in high temperature (17). So we investigated the function of CRY1 in hypocotyl elongation in response to ambient temperature changes. Hypocotyl elongation of wild-type (WT), cry1, and CRY1 overexpression lines (35S::GFP-CRY1) were recorded after 4 d of treatment in continuous white light at 22 °C and 28 °C. The cry1 mutants exhibited far more hypocotyl elongation at 28 °C than at 22 °C compared with WT (the hypocotyl length ratio of cry1 28 °C/22 °C is 3.2, WT is 2.4), whereas the GFP-CRY1 overexpression seedlings only elongated modestly at the higher temperature (GFP-CRY1 28 °C/22 °C = 1.6), suggesting CRY1 repressed the high temperature-induced hypocotyl elongation (Fig. 1 C–E).

To further confirm this observation, we measured cell lengths in the elongation zone of the hypocotyls. Noticeable cell elongation was observed in WT at 28 °C, whereas cell elongation of cry1 mutants was more significant at 28 °C than at 22 °C. Cells of the GFP-CRY1 overexpression seedlings only elongated modestly in response to an increase in temperature (Fig. 1F and Fig. S1 E and F). We also examined the effects of the cry1 mutation on petiole elongation, which was also affected by high temperature. Petiole elongation markedly increased in cry1 mutants when grown at 28 °C (Fig. S1 G–I).

COP1 acts as a central repressor in plant light signaling, and COP1 and CRY1 reside in the same multiprotein complex. Our results indicated that the GUS-COP1 overexpression seedlings were more elongated at 28 °C than 22 °C compared with WT, whereas the cop1-6 mutant only elongated mildly at the higher temperature (Fig. S1 B and C), in a manner reminiscent of the GFP-CRY1 overexpression seedlings. Cell-length measurements were also consistent with the hypocotyl elongation data (Fig. S1 D–F). Taken together, we conclude that CRY1 serves as a negative regulator of hypocotyl elongation in response to elevated ambient temperature, whereas COP1 serves as a positive regulator.

To investigate whether CRY1 regulates the high temperature-mediated hypocotyl elongation in a blue light-dependent manner, we examined the hypocotyl length of WT, cry1, and GFP-CRY1 in continuous blue light, continuous red light, and complete darkness at both 22 °C and 28 °C. In the red light and dark conditions, all had longer hypocotyls at 28 °C, and the hypocotyl ratios (28 °C/22 °C) were almost the same for WT, cry1 mutant, and GFP-CRY1 (Fig. 1 G and H and Fig. S1 K–M). In contrast, when grown under continuous blue light, cry1 mutants were more sensitive to temperature changes, whereas GFP-CRY1 was insensitive to temperature changes (Fig. 1 G and H and Fig. S1 K–M). The data presented here suggested that CRY1 repressed high temperature-mediated hypocotyl elongation in a blue light-dependent manner. The transcription level of CRY1, and also the protein level of CRY1, showed no significant changes at different temperatures (Fig. S2).

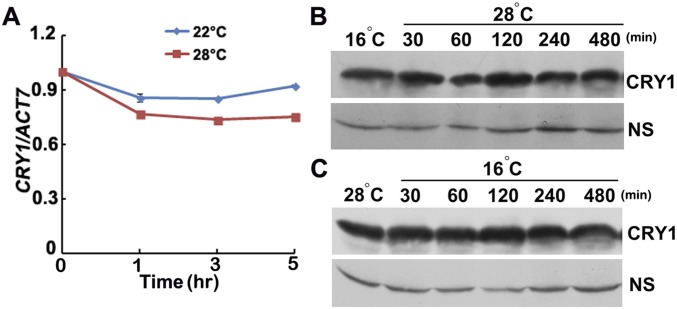

Fig. S2.

CRY1 expression is not temperature regulated. (A) qPCR results showing the lack of dramatic change of CRY1 transcription in response to increased temperature. Four-day-old seedlings grown in 22 °C in continuous white light condition were transferred to 28 °C or were continually placed at 22 °C for a 5-h time course, respectively. Error bars represent SD of three technical replicates of qPCR. Each experiment was performed at least three times with similar results. (B and C) Immunoblots showing the lack of temperature effects on the abundance of the CRY1 proteins in 6-d-old seedlings under the conditions tested. Samples were fractionated by 10% (wt/vol) Acrylamide SDS/PAGE, blotted, and probed with the anti-CRY1 antibody. WT plants were grown in 22 °C long-day (LD) condition for 6 d, transferred to 16 °C continuous light condition (B), or to 28 °C (C) for 16 h, then transferred to 28 °C (B) or 16 °C (C) for the indicated time before sample collection.

Intriguingly, COP1 also regulated the high temperature-mediated hypocotyl elongation in a light-dependent manner. In the dark, the cop1-6 mutant was strikingly more elongated at 28 °C than at 22 °C, only mildly elongated in continuous red light, while not elongated at elevated temperatures in continuous blue light. The GUS-COP1 overexpression seedlings were more elongated at 28 °C than 22 °C in either continuous blue or red light, but not in the dark (Fig. S1 J–M), indicating that CRY1 may regulate the temperature responses through COP1-dependent and also COP1-independent pathways.

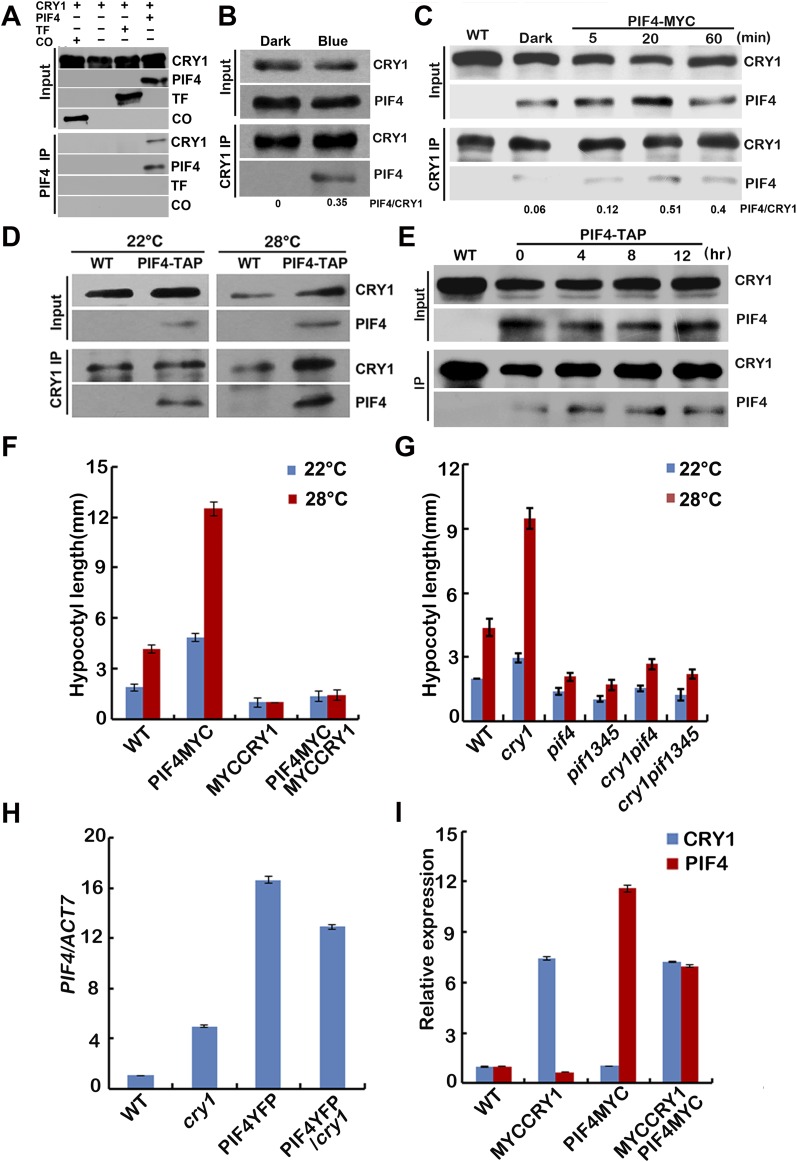

CRY1 Physically Interacts with PIF4 in a Blue Light-Dependent Manner.

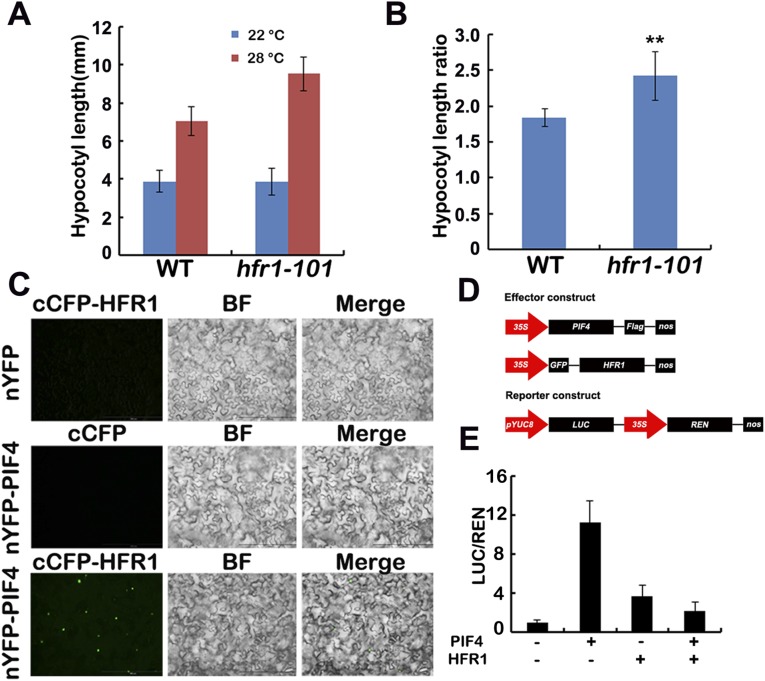

It was reported that PIF4 and PIF5 were responsible for not only red light but also blue light-regulated hypocotyl elongation (35), and PIF4 plays a prominent role in ambient temperature responses. We therefore reasoned that CRY1 might regulate the high temperature-induced hypocotyl elongation through PIF4. Our data suggested that CRY1 might regulate temperature responses through a COP1-dependent and also a COP1-independent pathway. For the COP1-dependent pathway, it has been shown that HFR1, which is degraded by COP1, can inhibit PIF4 (17, 36), and that HFR1 controls hypocotyl growth in a temperature-dependent manner in blue light (17). CRY1 suppresses the E3 ubiquitin ligase activity of COP1 to stabilize HFR1 (10–13). Our data also indicated that the hfr1 mutant was more sensitive to elevated temperature (Fig. S3 A and B), and that HFR1 interacted with PIF4 in planta to inhibit the transcription activity of PIF4 (Fig. S3 C–E). So that CRY1 might regulate PIF4 via HFR1 to regulate hypocotyl elongation in response to elevated temperature. CRY1 also repressed the transcription of PIF4, the expression level of PIF4 was higher in the cry1 mutant, but lower in the cop1 mutant (Fig. S4A), given that HY5 might regulate the transcription of PIF4 (32, 37), CRY1-COP1 might regulate PIF4 transcription via HY5. Many reports have shown that light destabilizes PIFs, whereas PHYs were necessary for the light-induced degradation of PIFs (38, 39); interestingly, CRY1 did not affect the protein stabilization of PIF4 (Fig. S4B).

Fig. S3.

HFR1 inhibits the hypocotyl elongation in response to high temperature via PIF4. (A and B) A phenotypic analysis showing that hfr1 mutant is far more elongated at 28 °C. Seedlings of the indicated genotypes were grown under long-day condition (16 light/8 dark) in 22 °C or 28 °C for 4 d. The hypocotyl length of the indicated genotypes were measured and are shown in A. SDs (n > 15) are indicated. The hypocotyl length ratios (28 °C/22 °C) of the quantified hypocotyl length in A are shown in B. Asterisks represent a significant difference from the WT with Student’s t test (P ≤ 0.01). (C) Bimolecular fluorescence complementation assays showing the in vivo protein interaction of PIF4 and HFR1. Leaf epidermal cells of N. benthamiana were cotransformated with cCFP-HFR1 and nYFP, or nYFP-PIF4, or cCFP and nYFP-PIF4. BF, bright field. Merge, overlay of the YFP and bright-field images. (D) Structure of the effector and the reporter constructs. (E) HFR1 regulates the transcription activity of PIF4. Relative reporter activity (LUC/REN) in plants with different effectors expression. Tobacco leaves were transfected with the reporter and the effector (PIF4 only or HFR1 only, or HFR1 and PIF4 together), kept in white light for 3 d. The relative LUC activities normalized to the REN activity are shown (LUC/REN, n = 3). Error bars indicate SDs of three biological repeats.

Fig. S4.

CRY1 represses the transcription of PIF4, but does not affect the protein stabilization of PIF4. (A) qPCR results showing that the transcription level of PIF4 is markedly increased in the cry1 mutant. Four-day-old seedlings grown in 22 °C continuous white light condition were transferred to 28 °C for a 5 h time course, respectively. Error bars represent SD of three technical repeats. Each experiment was performed at least three times with similar results. (B) Immunoblots showing that CRY1 did not affect the abundance of the PIF4 proteins in 4-d-old seedlings under the conditions tested. Samples were fractionated by 10% SDS/PAGE, blotted, and probed with the anti-MYC antibody. PIF4-TAP in WT or cry1 backgrounds were grown in 22 °C continuous blue light condition for 4 d, then transferred to 28 °C continuous blue light condition for the indicated time before sample collection.

For the COP1-independent pathway, it has been shown that mouse CRYs physically interact with two bHLH proteins, CLOCK and BMAL (40), and Arabidopsis CRY2 interacts with bHLH proteins CIBs (7, 8). We investigated the interaction between CRY1 and PIF4 in more detail. The insect cell expressed CRY1 interacted with the Escherichia coli expressed PIF4 in an in vitro pull-down assay (Fig. S5A), and more CRY1 was pulled down with PIF4 under blue light than under dark (Fig. 2A), indicating that CRY1 interacts with PIF4 in a blue light-dependent manner in vitro. CRY1 also interacts with PIF4 in plant cells in the BiFC (bimolecular fluorescence complementation) assays (Fig. 2B) (41, 42). As shown in Fig. 2B, strong fluorescence was detected in the nuclei of cells cotransformed with cCFP-PIF4 and CRY1-nYFP plasmids, but no fluorescence was detected in cells transformed with the cCFP and CRY1-nYFP or cCFP-PIF4 with nYFP plasmids (Fig. 2B). The in vivo interaction of PIF4 and CRY1 was further examined by coimmunoprecipitation (IP). Seedlings were either kept in the dark or exposed to blue light for 20 min (Fig. 2C) or 15 min (Fig. S5B) or 5, 20, or 60 min time course (Fig. S5C) (40 μmol⋅m–2⋅sec–1), and then subjected to co-IP analyses. More PIF4 was coprecipitated with CRY1 from seedlings irradiated with blue light than that left in dark. These results argue strongly that blue light stimulates accumulation of the CRY1–PIF4 complex in plant cells. We conclude that PIF4 interacts with CRY1 in vivo, and PIF4 undergoes blue light-dependent physical interactions with CRY1. PIF4 coprecipitated with CRY1 in samples kept at 22 °C and also samples moved to 28 °C, demonstrating that PIF4 interacts with CRY1 in both 22 °C and 28 °C (Fig. S5 D and E).

Fig. S5.

CRY1 interacts with PIF4 in a blue light-dependent manner. (A) In vitro pull-down assays showing interaction between CRY1 and PIF4. His-TF–tagged PIF4 or His-TF tag or His-TF–tagged CO (CONSTANS) were mixed with CRY1 purified from insect cells, and PIF4 antibody was used for the in vitro pull down. The products were analyzed by immunoblot probed with the anti-CRY1 (CRY1) or the anti-PIF4 antibody (PIF4) or the anti-His antibody (TF and CO). (B and C) Co-IP assays of samples prepared from 6-d-old 35S::PIF4-TAP or 35S::PIF4-MYC seedlings grown in long-day condition (16 light/8 dark), moved to dark for 1 d, then either exposed to blue light (40 μmol⋅m–2⋅sec–1) for 15 min (B) or for 5, 20, or 60 min time course (C) or kept in dark. (D and E) Co-IP assays of samples prepared from 6-d-old 35S::PIF4-TAP seedlings grown in 22 °C long-day condition, moved to 28 °C for 4 (D) or for 4, 8, or 12 h time course (E) or kept in 22 °C for 4 h. Total proteins (Input) or IP product of anti-CRY1 antibody (CRY1-IP) were probed, in immunoblots, by the anti-CRY1 antibody (CRY1), stripped and reprobed by the anti-MYC (PIF4-TAP or PIF4-MYC) antibody. (F and G) Phenotypic analysis. Seedlings of the indicated genotypes were grown in the 22 °C or 28 °C continuous white light (40 μmol⋅m–2⋅sec–1) for 4 d. The hypocotyl lengths of the indicated genotypes were measured and are shown in F and G. SDs (n > 15) are indicated. (H and I) qPCR results showing the expression of PIF4 (H) or PIF4 and CRY1 (I) in different genotypes indicated. Four-day-old seedlings grown at 22 °C in LD condition were used. Error bars represent SD of three technical repeats. Each experiment was performed at least three times with similar results.

Fig. 2.

CRY1 interacts with PIF4 in a blue light-dependent manner. (A) In vitro pull-down assays showing blue light-dependent interaction between CRY1 and PIF4. His-TF–tagged PIF4 or His-TF tag were mixed with CRY1 expressed and purified from insect cells (sf9) in the dark condition, and were incubated under blue light (40 μmol⋅m−2⋅sec−1) or dark conditions for 30 min, and PIF4 antibody was used for the in vitro pulldown. The products were analyzed by immunoblot probed with the anti-CRY1 (CRY1) or the anti-PIF4 antibody (PIF4) or the anti-His antibody (TF). (B) BiFC assays of the in vivo protein interaction. Leaf epidermal cells of Nicotiana benthamiana were cotransformated with cCFP-PIF4 and CRY1-nYFP or cCFP and CRY1-nYFP or nYFP and cCFP-PIF4. BF, bright field. Merge, overlay of the YFP and bright-field images. (C) Co-IP assays of samples prepared from 6-d-old 35S::PIF4-TAP seedlings grown in long-day condition (16 light/8 dark), moved to dark for 1 d, then either exposed to blue light (40 μmol⋅m−2⋅sec−1) or kept in dark. Total proteins (input) or IP product of anti-CRY1 antibody (CRY1-IP) were probed, in immunoblots, by the anti-CRY1 antibody (CRY1), stripped, and reprobed by the anti-MYC (PIF4-TAP) antibody. (D–G) Phenotypic analysis. (D and E) Seedlings of the indicated genotypes were grown in the 22 °C or 28 °C continuous blue or red light (both 40 μmol⋅m−2⋅sec−1) for 4 d. (F and G) Seedlings of the indicated genotypes were grown in the 22 °C or 28 °C continuous blue light (40 μmol⋅m−2⋅sec−1) for 4 d. The hypocotyl lengths of the indicated genotypes were measured and are shown in F and G. SDs (n > 15) are indicated.

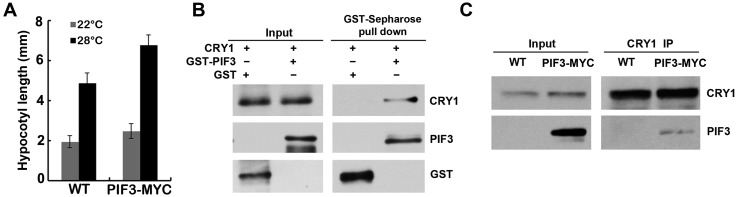

To further study the relationship between CRY1 and PIF4, we investigated genetic interactions between the CRY1 and PIF4 genes. As shown in Fig. 2 D and E, PIF4-YFP overexpression seedlings exhibited long hypocotyl phenotypes in the red light conditions, whereas blue light repressed the long hypocotyl phenotypes of PIF4-YFP seedlings. Furthermore, blue light suppressed the long hypocotyl phenotype of PIF4-YFP seedlings in a CRY1-dependent manner, because seedlings expressing PIF4-YFP in the cry1 background showed long hypocotyl phenotypes in both red and blue light conditions. Transgenic seedlings expressed PIF4-MYC and MYC-CRY1 together exhibited a similar phenotype as MYC-CRY1 seedlings under both continuous blue light (Fig. 2F) and continuous white light (Fig. S5F) conditions, consistent with that blue light suppressed the long hypocotyl phenotype of PIF4-YFP seedlings in a CRY1-dependent manner, the expression level of PIF4 and CRY1 genes is shown in Fig. S5 H and I. A CRY1-deficient cry1 mutant was crossed with pif1345, resulting cry1pif4 and cry1pif1345. The high temperature-induced hypocotyl elongation phenotype of cry1 was partially suppressed in cry1pif4 but was suppressed in cry1pif1345 under continuous blue light condition (Fig. 2G), which suggested that PIF4 and also other PIFs act downstream of CRY1. It is reported that pif4 but not pif1, pif3, pif5 mutant showed no hypocotyl elongation in response to higher temperature (25). Our data showed that PIF3 overexpression line was more sensitive to the increased temperature (Fig. S6A). Those results indicate that PIF4 plays a major role in temperature responses, but PIF3 and also maybe other PIFs are also involved in temperature responses. Furthermore, in vitro pull down and also co-IP assays both showed that PIF3 interacted with CRY1 (Fig. S6 B and C), indicating that PIF3 also acts downstream of CRY1. Interestingly, the high temperature-induced hypocotyl elongation phenotype of cry1 was suppressed in both cry1pif4 and cry1pif1345 under white light conditions (Fig. S5G), indicating the cross-talk between different light signaling. cry1pif4 and cry1pif1345 also showed shorter hypocotyl phenotype than cry1 at 22 °C (Fig. 2G and Fig. S5G). These data suggested that PIF4 and PIF3 act downstream of CRY1, and that CRY1 mediates the blue light inhibition of the hypocotyl elongation at 22 °C or in response to elevated temperature at least partially through the PIFs transcription factor.

Fig. S6.

CRY1 interacts with PIF3. (A) Phenotypic analysis. Seedlings of the indicated genotypes were grown in the 22 °C or 28 °C continuous white light (40 μmol⋅m–2⋅sec–1) for 4 d. The hypocotyl lengths of the indicated genotypes were measured and are shown. SDs (n > 15) are indicated. (B) In vitro pull-down assays showing interaction between CRY1 and PIF3. GST-tagged PIF3 or GST bound to GST beads was mixed with CRY1 purified from insect cells. The bound proteins were eluted after removing unbound proteins by washing, and analyzed by immunoblot probed with the anti-CRY1 (CRY1) or the anti-GST antibody (PIF3 and GST). (C) Co-IP assays of samples prepared from 6-d-old WT or 35S::PIF3-MYC seedlings grown in long-day condition (16 light/8 dark). Total proteins (Input) or IP product of anti-CRY1 antibody (CRY1-IP) were probed, in immunoblots, by the anti-CRY1 antibody (CRY1), stripped, and reprobed by the anti-MYC (PIF3-MYC) antibody.

CRY1 Affects the High Temperature-Induced Elevation of YUC8 Transcripts and the Free IAA Level.

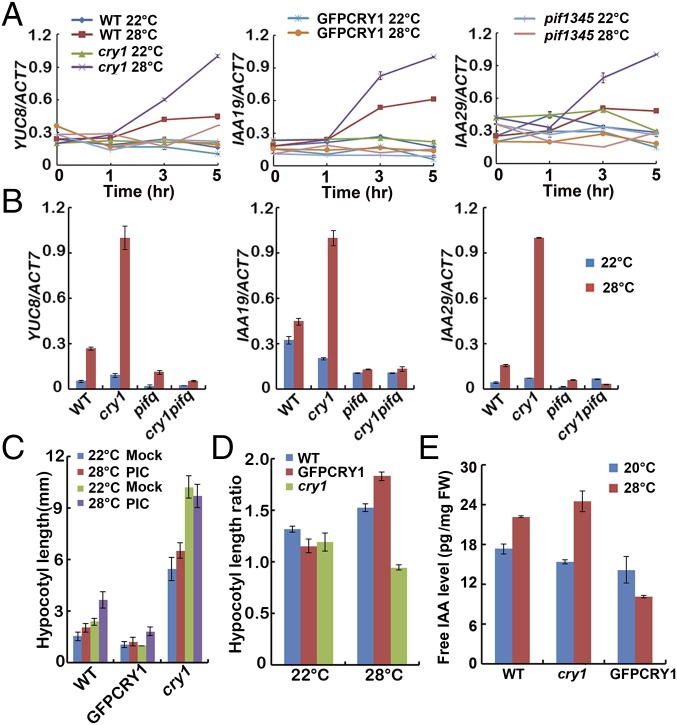

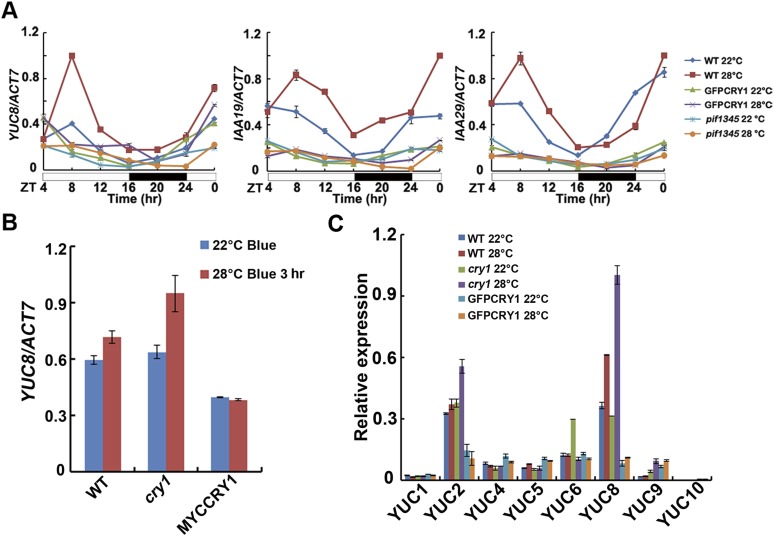

The hormone auxin, or IAA, is fundamental to plant growth and development. It has been reported that plants possess longer hypocotyls because of increased IAA levels when they were grown at elevated temperatures (26, 27, 43, 44). IAA can be formed via tryptophan-dependent and tryptophan-independent pathways (45). PIF4 controls high temperature-induced hypocotyl elongation by increasing free IAA levels via direct stimulation of YUC8 and TAA1 transcriptions and the resultant increase in YUC8 and TAA1 enzymatic activities (25–28, 30). IAA19 and IAA29 are also PIF4 targets (30). Because CRY1 interacts with PIF4 in a blue light-dependent manner, we then asked how the CRY1–PIF4 interaction affected the expression of PIF4 target genes. When WT seedlings grown at 22 °C white light condition for 4 d were transferred to 28 °C, the transcript abundances of YUC8 and the auxin response genes IAA19 and IAA29 were all elevated. In contrast, the high temperature-induced up-regulation of YUC8, IAA19, IAA29 expression was largely abolished in the GFP-CRY1 (Fig. 3A and Fig. S7A). In the cry1 mutant, the expression levels of YUC8, IAA19, and IAA29 were all up-regulated to a larger extent at 28 °C. Blue light repressed the high temperature-mediated hypocotyl elongation, and also the high temperature-mediated expression increase of YUC8, when the WT seedlings grown at 22 °C continuous blue light condition for 4 d were transferred to 28 °C continuous blue light, the transcript abundance of YUC8 was not significantly elevated, and there was totally no change of YUC8 expression in the CRY1 overexpression line, whereas in the cry1 mutant, the expression level of YUC8 was significantly up-regulated at 28 °C (Fig. S7B). Our results also indicated that the higher temperature did not up-regulate the expression of other YUC family genes tested and that CRY1 did not affect the expression of those genes (Fig. S7C). Consistent with that cry1pif1345 exhibited the same phenotype as pif1345, the expression levels of YUC8, IAA19, and IAA29 were the same in cry1pif1345 as in pif1345 (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

CRY1 affects the high temperature-induced elevation of YUC8 transcripts and the free IAA level. (A and B) qPCR results showing high temperature-induced expression patterns of YUC8, IAA19, and IAA29 of the indicated genotypes. Four-day-old seedlings grown in 22 °C in continuous white light condition were transferred to 28 °C or were continually placed at 22 °C for a 5-h time course (A) or for only 3 h (B), respectively. (C) Hypocotyl length of 4-d-old WT, GFP-CRY1, and cry1 seedlings grown in the 22 °C or 28 °C continuous blue (40 μmol⋅m−2⋅sec−1) conditions, with and without the synthetic auxin picloram. The hypocotyl lengths were measured and are shown in C. SDs (n > 15) are indicated. Hypocotyl length ratios (Picloram/Mock) of the quantified hypocotyl length in C are shown in D. (E) IAA concentrations of 6-d-old WT, cry1, and GFP-CRY1 seedlings grown in 20 °C and 28 °C continue white light (40 μmol⋅m−2⋅sec−1) condition.

Fig. S7.

Effects of CRY1 on the expression of YUC genes in response to increased temperature. (A) qPCR results showing high temperature-induced expression patterns of YUC8, IAA19, and IAA29 of the indicated genotypes. Four-day-old seedlings grown at 22 °C in LD condition were transferred to 28 °C at ZT4 or were continually placed at 22 °C for 1 d, respectively, samples were collected every 4 h. (B) Results of qPCR analyses, showing the lack of dramatic change of mRNA expression of YUC8 in response to increased temperature under blue light. Four-day-old seedlings grown at 22 °C in continuous blue light condition were transferred to 28 °C continuous blue light for 3 h. (C) Results of qPCR analyses, showing the lack of dramatic change of mRNA expression of other YUC genes except YUC8 in response to increased temperature. Six-day-old seedlings grown at 22 °C in LD condition were transferred to 28 °C for 3 h. Error bars represent SD of three technical repeats. Each experiment was performed at least three times with similar results.

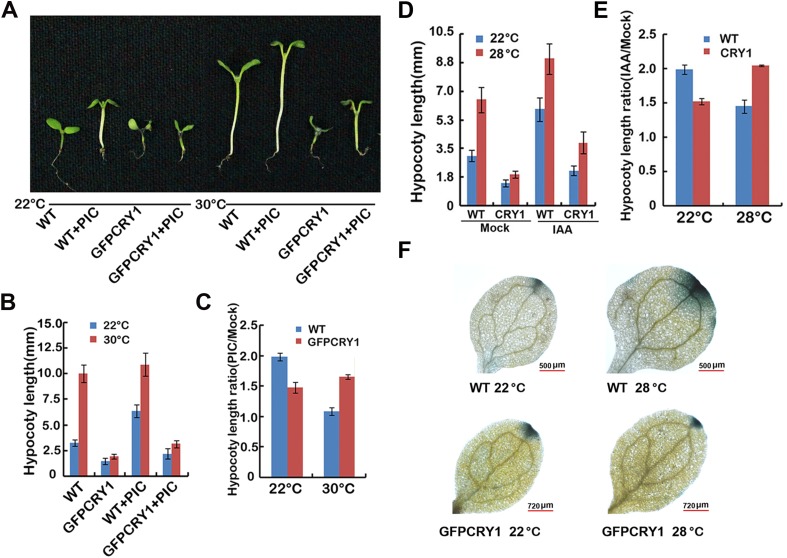

To examine whether the greatly attenuated elongation response in GFP-CRY1 overexpression seedlings at high temperature is the result of reduced IAA levels, we attempted to chemically rescue the phenotypes by applying exogenous IAA to seedlings. The high temperature-induced hypocotyl elongation phenotype was partially restored to GFP-CRY1 when picloram or IAA was applied under both continuous blue or white light conditions (Fig. 3 C and D and Fig. S8 A–E). Consistent with that blue light repressed the elevated temperature-induced hypocotyl elongation and auxin biosynthesis, WT seedlings were more sensitive to picloram at 28 °C than at 22 °C under blue light, whereas cry1 mutant is insensitive to picloram at 28 °C blue (Fig. 3 C and D). Direct measurement of the IAA content of seedlings revealed that WT seedlings grown at 28 °C white light displayed significantly higher IAA levels compared with levels measured at 20 °C, and the IAA level increased more in cry1 mutants grown at 28 °C compared with those grown at 20 °C. In contrast, the elevated levels of IAA were abolished in GFP-CRY1 plants (Fig. 3E).

Fig. S8.

Auxin treatment can partially complement the hypocotyl phenotype of GFP-CRY1 in response to elevated temperature. (A–C) Hypocotyl length of 6-d-old WT and GFP-CRY1 grown at 22 °C or 30 °C, with or without the synthetic auxin picloram. Seedlings grown in 22 °C and 30 °C continuous white light condition were sprayed with 1 µM picloram or mock after germination. Images of the representative seedlings are shown in A, the hypocotyl lengths were measured and are shown in B. SDs (n > 15) are indicated. Hypocotyl length ratios (Picloram/Mock) of the quantified hypocotyl length in B are shown in C. (D) Hypocotyl length of 6-d-old WT and GFP-CRY1 seedlings grown at 22 °C or 28 °C, with and without IAA. Seedlings grown in 22 °C and 28 °C continuous white light condition were sprayed with 10 µM IAA or mock after germination. The hypocotyl lengths were measured and are shown in D. SDs (n > 15) are indicated. Hypocotyl length ratios (IAA/Mock) of the quantified hypocotyl length in D are shown in E. (F) GUS staining of seedlings expressing DR5::GUS transgene in WT, GFP-CRY1 background.

The auxin-responsive DR5::GUS reporter construct was introduced into the GFP-CRY1 background, so that we could analyze auxin activity in planta. GUS activity was analyzed in seedlings grown either at 22 °C or 28 °C under continuous white light conditions for 4 d. Increased GUS activity was noted in WT grown at 28 °C. In contrast, no significant increase in GUS activity was recorded in GFP-CRY1 transgenic lines at 28 °C (Fig. S8F). Taken together, these data demonstrated that CRY1 affected the transcription of PIF4 targets genes and the high temperature-induced IAA increase and also the resultant auxin growth response.

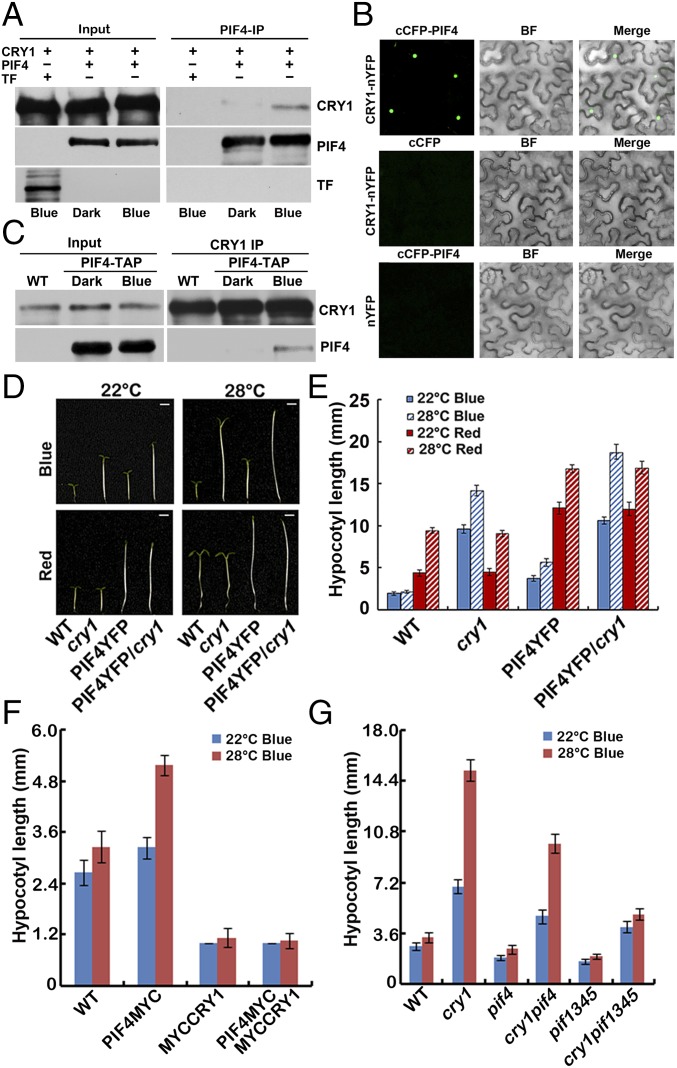

CRY1 Affects the Transcription Activity of PIF4.

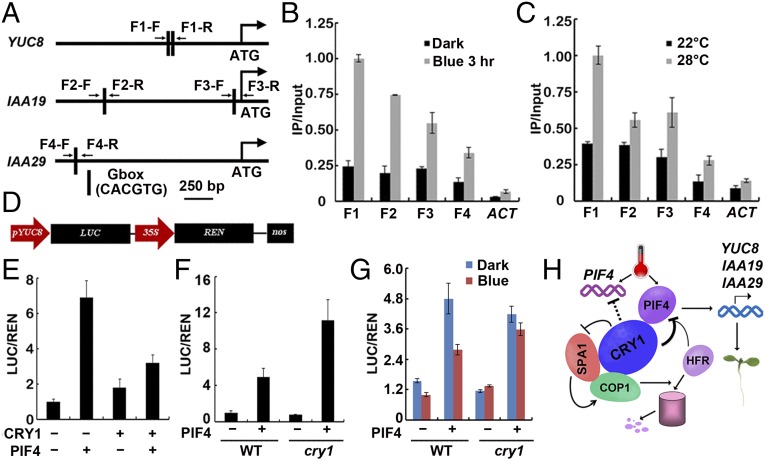

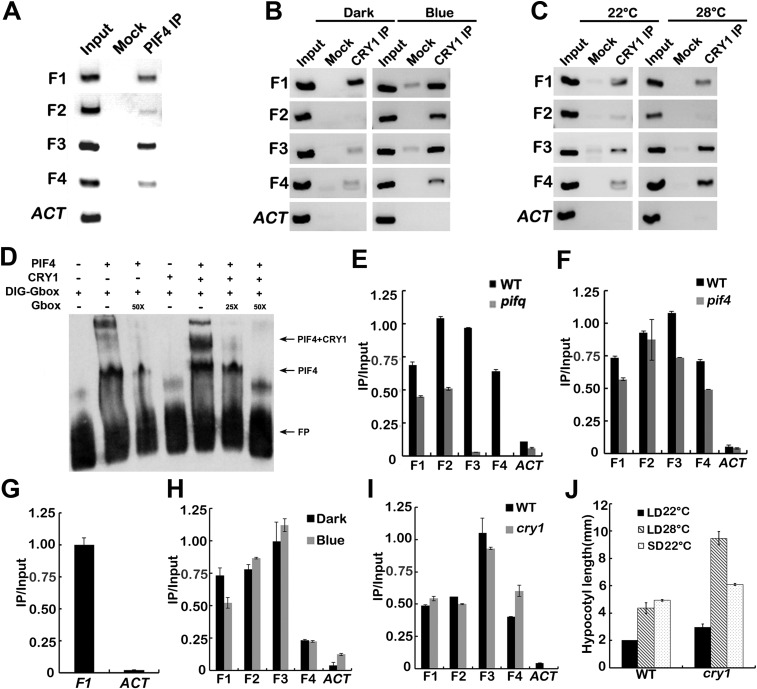

We hypothesized that because CRY1 undergoes physical interaction with PIF4 and it affects the expression of PIF4 target genes, CRY1 could physically associate with genomic regions that PIF4 bound to. To test this possibility, we performed ChIP-qPCR and ChIP-PCR assays. Both ChIP-qPCR (Fig. 4 A–C) and ChIP-PCR (Fig. S9 B and C) assays showed that, in vivo, CRY1 was associated with the same chromatin region of the YUC8, IAA19, and IAA29 promoters as seen for PIF4 (Fig. S9A). The same PCR primer pairs were used for detecting the chromatin binding of PIF4 and CRY1 (Table S1). Consistent with that CRY1 interacts with PIF4 in a blue light-dependent manner, CRY1 associated with the promoters of YUC8, IAA19, and IAA29 genes in a blue light-dependent manner. Promoter binding of CRY1 was markedly increased with blue light treatment compared with the dark grown control condition (Fig. 4B and Fig. S9B). Warm temperatures also promoted the association of CRY1 to the YUC8, IAA19, and IAA29 promoters. Promoter associations were greatly enhanced at 28 °C relative to 22 °C especially for YUC8 (Fig. 4C and Fig. S9C). Further evidence supporting that CRY1 and PIF4 form a complex to bind to targets promoter came from electrophoretic mobility-shift assays (EMSA) by using PIF4 and CRY1 proteins expressed in vitro. As shown in Fig. S9D, PIF4 bound to the G-box containing DNA fragments present in the promoter region of YUC8, CRY1 could not bind to the DNA fragments itself but could bind together with PIF4. CRY1 promoter association was significantly decreased in the pif1345 mutant background (Fig. S9E), but was not that significantly affected in the pif4 mutant background (Fig. S9F), consistent with that multiple PIFs acted downstream of CRY1. PIF3 also associated with the YUC8 promoter (Fig. S9G), the same as reported before (46, 47).

Fig. 4.

CRY1 affects the transcription activity of PIF4. (A) Diagram depicting the putative promoter of YUC8, IAA19, IAA29. (B and C) Representative results of the ChIP-qPCR assays. Chromatin fragments (∼500 bp) were prepared from 7-d-old WT seedlings, immunoprecipitated by the anti-CRY1 antibody, and the precipitated DNA was analyzed by qPCR using the primer pairs indicated. The IP/input ratios are shown with the SDs (n = 3). (D) Structure of the YUC8 promoter-driven dual-LUC reporter gene. YUC8 promoter (−1,635 bp to 0 bp), 35S promoter, REN luciferase (REN), firefly luciferase (LUC), and T-DNA (LB and RB) are indicated. (E–G) CRY1 regulates the transcription activity of PIF4. (E) Relative reporter activity (LUC/REN) in planta with different effectors expression. Tobacco leaves were transfected with the reporter and the effector (CRY1 only, PIF4 only, or CRY1 and PIF4 together), kept in white light for 3 d. The relative LUC activities normalized to the REN activity are shown (LUC/REN, n = 3). (F and G) Relative reporter activity (LUC/REN) in protoplasts of WT and cry1 with or without PIF4 expression. Arabidopsis protoplasts of WT and cry1 were transfected with the reporter DNA together with or without PIF4, kept in white light for 8 h (F), or kept in dark and blue light (40 μmol⋅m−2⋅sec−1) for 8 h (G). The relative LUC activities normalized to the REN activity are shown (LUC/REN, n = 3). (H) A hypothetical model depicting CRY1 mediated blue-light regulation of PIF4. The model hypothesizes that in response to blue light, CRY1 interacts with PIF4 to repress the activity of PIF4 promoting transcription of the target gene, and CRY1 can also repress PIF4 through inhibiting COP1-mediated degradation of HFR1.

Fig. S9.

CRY1 binds to the PIF4 targets together with PIF4. (A–C) ChIP-PCR showing interaction of PIF4 (A) or CRY1 (B and C) with chromatin regions of the YUC8, IAA19, and IAA29 genes. Representative results of the ChIP-PCR assays showing that PIF4 (A) binds to the chromatin regions of those genes, and that CRY1 (B and C) binds to the same chromatin regions of those genes in a blue light-dependent and higher temperature-promoted manner. Chromatin fragments (∼500 bp) were prepared from 7-d-old transgenic or WT seedlings, immunoprecipitated by the anti-MYC or anti-CRY1 antibody, and the precipitated DNA were PCR-analyzed by using the primer pairs indicated in Fig. 4A. (D) EMSA showing interaction of PIF4 with the DIG-labeled G-box motifs present in the YUC8 promoter, competition by the unlabeled wild-type G box, and CRY1 failed to bind to G box itself, but could bind to the G-box motifs together with PIF4. (E and F) Representative results of the ChIP-qPCR assay showing that CRY1 binds less to the PIF4 targets in the pif1345 mutant background (E), but not in the pif4 single mutant (F). (G) Representative results of the ChIP-qPCR assay showing interaction of PIF3 with chromatin regions of the YUC8. (H and I) Representative results of the ChIP-qPCR assays showing that blue light (H) or CRY1 (I) does not affect the DNA binding of PIF4. (J) A phenotypic analysis showing that cry1 mutant is far more elongated at 28 °C long-day condition than at 22 °C short day. Seedlings of WT and cry1 mutant were grown under long-day condition (16 light/8 dark) in 22 °C or 28 °C or under short-day condition (8 light/16 dark) in 22 °C for 4 d. The hypocotyl length of the indicated genotypes were measured and are shown in A. SDs (n > 15) are indicated.

Table S1.

Oligonucleotide primers used in this work

| Assays | Destination products | Templet | Primer name | Primer sequence |

| Transformation | p1300-PIF4-TAP | TAP | TAP-F | 5′-CCGGGGATCCTCTAGAGGTGAACAAAAGTTGATTTCTGAA-3′ |

| TAP-R | 5′-GATCCTGCAGGTCGACTCACTTGTCATCGTCATCCTTG’ | |||

| PIF4 | PIF4-F | 5′-TCCCCCCGGGATGGAACACCAAGGTTGGAG-3′ | ||

| PIF4-R | 5′-TGCTCTAGAGTGGTCCAAACGAGAACCG-3′ | |||

| Dual-LUC | pGreen-0800-YUC8p | YUC8 promoter | YUC8-F | 5′-CCGCTCGAGATTAGGAGTAAACAAGAAGCAAGG-3′ |

| YUC8-R | 5′-CGCGGATCCTCTTTTTTTATAAGTTTCTTTAATAAGTATT-3′ | |||

| pHBT-PIF4 | PIF4 | PIF4-F | 5′-GAGGCGCGCCGGATCCATGGAACACCAAGGTTGGAG-3′ | |

| PIF4-R | 5′-GCACTCCCATGGATCCGTGGTCCAAACGAGAACCG-3′ | |||

| qRT-PCR | IAA19 | IAA19-F | 5′-GGTGACAACTGCGAATACGTTACCA-3′ | |

| IAA19-R | 5′-CCCGGTAGCATCCGATCTTTTCA-3′ | |||

| IAA29 | IAA29-F | 5′-CACGGCGATGAACAACAACATAT-3′ | ||

| IAA29-R | 5′-CTCTGTCGCAATCTTCATATTCG-3′ | |||

| CRY1 | CRY1-F | 5′-CTCTAAGAACCGCAGAAAAGCC-3′ | ||

| CRY1-R | 5′-CTTTTCTCACACTCACTTCCCCA-3′ | |||

| YUC1 | YUC1-F | 5′-TGGAGAGTAAAGACTCATGAT-3′ | ||

| YUC1-R | 5′-GTACTCACTCGCGTGAACGAT-3′ | |||

| YUC2 | YUC2-F | 5′-GGTGACACGGATCGGTTAGGGT-3′ | ||

| YUC2-R | 5′-TGCCGAATAATGCATTACCCGT-3′ | |||

| YUC4 | YUC4-F | 5′-TTATGGCAAAAAAGAACCTACGAC-3′ | ||

| YUC4-R | 5′-GGAAGTTTTTAGGGAAAGGCAT-3′ | |||

| YUC5 | YUC5-F | 5′-TTCAACGAGTGTGTCCAGTCTGCT-3′ | ||

| YUC5-R | 5′-TCTCTGGAACAACTTTCTCCGCGT-3′ | |||

| YUC6 | YUC6-F | 5′-GGGCTGTCCATGTTCTTACTGAA-3′ | ||

| YUC6-R | 5′-CGGGAAACAACCAAAAGGAA-3′ | |||

| YUC8 | YUC8-F | 5′-TGTATGCGGTTGGGTTTACGAGGA-3′ | ||

| YUC8-R | 5′-CCTTGAGCGTTTCGTGGGTTGTTT-3′ | |||

| YUC9 | YUC9-F | 5′-CCTGCAATCAAACAGTTCTCGCGT-3′ | ||

| YUC9-R | 5′-TGAAGCCAAGAAGGGACGTTGCTA-3′ | |||

| YUC10 | YUC10-F | 5′-TTCTGAAGTATGCTCCAGTGGCGA-3′ | ||

| YUC10-R | 5′-GTTTGGTGGCGAAAGGACCTTGTT-3′ | |||

| ACT7 | ACT7-F | 5′-AGGCACCTCTTAACCCTAAAGC-3′ | ||

| ACT7-R | 5′-GGACAACGGAATCTCTCAGC-3′ | |||

| ChIP | YUC8 | YUC8-F | 5′-GGGAATGGGTTTGATGTGGAATT-3′ | |

| IAA19 | YUC8-R | 5′-GAGAAGGGAAGTGATGGAATTAG-3′ | ||

| IAA19-F1 | 5′-GATATCAAATGACTCCACGTGTC-3′ | |||

| IAA19-R1 | 5′-TCCGTGAAAGCTCTCTTCTTCAT-3′ | |||

| IAA19-F2 | 5′-GGTGCTACAAATGTCGTTTGGTA-3′ | |||

| IAA19-R2 | 5′-GATGGGGTTTAGAGGACGTAGGG-3′ | |||

| IAA29 | IAA29-F | 5′-CTCACTACCTTTCGCTTAACGTG-3′ | ||

| IAA29-R | 5′-GTAGTATGTAAATCTAGACCCAA-3′ | |||

| ACT2 | ACT2-F | 5′-CGTTTCGCTTTCCTTAGTGTTAGCT-3′ | ||

| ACT2-R | 5′-CACAACGCATGCTAAACAGATCTAG-3′ | |||

| Pull down | pCold-TF | PIF4 | PIF4-F | 5′-CCGGAATTCATGGAACACCAAGGTTGGAG-3′ |

| PIF4-R | 5′-CGCGTCGACCTAGTGGTCCAAACGAGAACC-3′ | |||

| pGEX4T1 | PIF3 | PIF3-F | 5′-CCGGAATTCATGCCTCTGTTTGAGCTTTTC-3′ | |

| PIF3-R | 5′-CCGCTCGAGTCACGACGATCCACAAAACT-3′ | |||

| pFastBac HTA | CRY1 | CRY1-F | 5′-CCGGAATTCATGTCTGGTTCTGTATCTGGTTG-3′ | |

| CRY1-R | 5′-CCGCTCGAGTTACCCGGTTTGTGAAAGC-3′ | |||

| EMSA | YUC8-F | 5′-CTCATCCTCTCCACGTGGCTTCCATTCCACGTCATCTTTTTCTTCCC-3′ | ||

| YUC8-R | 5′-CGAGAGGAAGCCACGTGGGGAAGAAAAAGATGACGTGGAATGGAAGC-3′ |

CRY1 forms a complex with PIF4 to associate with PIF4 target genes under blue light conditions, and blue light or CRY1 did not affect the DNA binding activity of PIF4 (Fig. S9 H and I). To analyze whether CRY1 affected the transcription activity of PIF4 on the YUC8 promoter, a transient transcription assay in tobacco leaves and in protoplasts were used to test PIF4 activity. We used a dual-LUC reporter plasmid that encodes a firefly luciferase (LUC) gene driven by the YUC8 promoter (−1,635 bp to 0 bp) and a Renilla luciferase (REN) gene driven by the constitutive 35S promoter (Fig. 4D) (7, 8, 48). The YUC8pro-LUC reporter was transiently expressed in tobacco leaves together with either CRY1 or PIF4 or both. PIF4 promoted the transcription of the YUC8 gene, and the expression level of YUC8 promoter-LUC was approximately twofold lower when PIF4 was combined with CRY1 than when only PIF4 was infiltrated although the same amount of PIF4 Agrobacteria cells were used (Fig. 4E). The reporter was also transiently expressed in WT and cry1 mutant protoplasts with or without PIF4. The expression level of YUC8 promoter-LUC was approximately twofold higher when PIF4 was expressed in cry1 protoplast than when PIF4 was expressed in WT under white light (Fig. 4F). Furthermore, CRY1 repressed the transcription activity of PIF4 in blue light but not in dark (Fig. 4G). CRY1 itself did not affect the transcription of the YUC8 promoter-LUC construct significantly (Fig. 4 E–G). Taken together, these data indicated that CRY1 formed a complex with PIF4 to suppress the transcription activity of PIF4 in a blue light-dependent manner (Fig. 4H).

Discussion

Plants evolve with multiple photoreceptors that function by interacting with photoreceptor-specific signaling proteins. Red light photoreceptors Phytochromes interact with PIFs to control red/far red light-regulated gene expression and morphogenesis (21–23). CRY2 interacts with CIBs to regulate the FT expression and also photoperiodic flowering (7–9). We show in the present study that CRY1 directly interacts with PIF4 in a blue light-dependent manner to regulate the expression of PIF4 targets and also high temperature-promoted hypocotyl elongation. Our previous studies demonstrate that blue light photoreceptors CRY2 and ZEITLUPE (ZTL) can both regulate CIB1, CRY2 physically interacts with CIB1 in response to blue light to activate its transcription activity (7, 8), whereas ZTL mediates blue-light suppression of CIB1 degradation (9). CIB1 seems to be the molecular basis of cross-talk between CRY2 and ZTL blue light receptors. PIF4 transcription factor interacts with both PhyB and CRY1, and it plays a role in temperature response, so that multiple plant photoreceptors and ambient temperature can mediate plant development through the same signaling component—PIF4. PIF4 appears to be the molecular basis of cross-talk between red and blue light pathways, and also among red and blue light and ambient temperature. It is reported that PhyA interacts with CRY1, and PhyB binds CRY2 (49, 50), so red and blue light may cross-talk at multiple layers to coordinately regulate plant development.

We also showed that CRY1 form a complex with PIF4 to associate with the PIF4 target genes, CRY1 and PIF4, which likely interacted on the nuclear DNA. Furthermore, our transactivation assays revealed that CRY1 repressed the transcription activity of PIF4. This observation is consistent with the CRYs function in animals, where CRYs act as transcriptional repressors (51). Our results suggest that CRY1 directly regulate the activity of PIF4 through physical interaction on the DNA, such that changes in the external environment can rapidly lead to phenotypic changes.

The expression of CRY1 is not temperature regulated (Fig. S2), consistent with the previous result (34). To exclude the possibility that CRY1 inhibits hypocotyl elongation more strongly at 28 °C than 22 °C, just because PIF4 is more active at 28 °C, we checked the phenotype of cry1 in short day condition because PIF4 also has a much bigger role in SD (24). cry1 mutant was not far more elongated than WT in short day condition (Fig. S9J). It was also reported that CRYs are required for temperature compensation of the circadian clock (34). These together suggest CRY1 itself may be involved in temperature response, which need to be further investigated. cop1-6 mutant is insensitive to the elevated temperature, the same as pif4, indicating that COP1 is essential for plant responses to ambient temperature; whether COP1 is involved in ambient temperature signaling independent of PIF4 needs to be further investigated.

Materials and Methods

Plant materials, seedling photothermol assays, immunoblots, the in vitro pull down, BiFC, co-IP, quantitative PCR (qPCR), free IAA measurement, ChIP, EMSA, and dual-LUC assays are as described (7, 8, 12) and in SI Materials and Methods.

SI Materials and Methods

Plant Materials and Growth Conditions.

Except where indicated, the Columbia ecotype of Arabidopsis was used. MYC-CRY1, cry1-304, pif1pif3pif4pif5, PIF3-MYC, GUS-COP1, cop1-6, PIF4-YFP, and PIF4-MYC, and hfr1-101 have been described (52–57). The PIF4-YFP/cry1, cry1pif4, cry1pif1345, and PIF4-MYC/MYC-CRY1 were prepared by genetic crosses. The full-length CRY1 and PIF4 coding sequences were cloned into pEGAD and pCambia1300, bearing either GFP (35S:GFP-CRY1) or Myc-His-Flag (35S:PIF4-TAP). Col-0 and cry1 mutant were transformed with 35S:GFP-CRY1 and 35S:PIF4-TAP by the floral dip transformation method. Phenotypes of transgenic plants were verified in at least three independent transgenic lines. Blue light or red light conditions were achieved by using light-emitting diode (LED) light incubator (Percival E30 LED; red light 670 nm and blue light 470 nm).

BiFC Assay.

The BiFC assay was based on that described previously with slight modifications (7, 42), nYFP was fused to CRY1 and PIF4 was fused to cCFP, transformed to Agrobacterium strain GV3101 containing pSoup-P19 plasmid that encodes the suppressor of gene silencing (48). Overnight cultures of Agrobacteria were collected by centrifugation, resuspended in MES buffer to 0.8 OD600, mixed, and incubated at room temperature for 2 h before infiltration. Agrobacteria suspension in a 1-mL syringe (without the metal needle) was carefully press-infiltrated manually onto healthy leaves of 3-wk-old Nicotiana Benthamiana. Plants were left under continuous white light for 3 d after infiltration.

Immunoblot.

Immunoblots were performed as described (7–9). For immunoblots, a mouse monoclonal anti-Myc antibody 4A6 (Millipore, no. 05–724, 1:4,000 dilution for immunoblot) was used to detect PIF4-TAP or PIF4-MYC fusion proteins. PIF4 antibody (Abiocode, no. 1307, 1:3,000 dilution) was used for detecting E. coli-expressed PIF4 in vitro.

Coimmunoprecipitation.

The coimmunoprecipitatin (co-IP) procedure was described (7). For co-IP, 7-d-old PIF4-TAP seedlings grown in long-day condition or in continuous white light at 22 °C or 28 °C, whereas the long-day grown seedlings were moved to dark for 16 h, then half were kept in dark whereas the other half were moved to blue light (40 μmol⋅m−2⋅sec−1) condition for 20 min, grounded in liquid nitrogen, homogenized in binding buffer [20 mM Hepes (pH 7.5), 40 mM KCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 1 mM PMSF], and centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 15 min. The 22 °C and 28 °C continuous white light grown seedlings were also grounded in liquid nitrogen. One milliliter of supernatant was mixed with 25 μL of anti-CRY1-IgG–coupled protein-A Sepharose, incubated at 4 °C for 20 min. Three microliters of anti-CRY1 antiserum was incubated with 20 μL of protein-A Sepharose beads in a 100-μL binding buffer, at 4 °C for 2 h, and used soon after. The beads were washed (approximately 20 s each) three times with washing buffer [20 mM Hepes (pH 7.5), 40 mM KCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1% Triton X-100). The bound proteins were eluted from the affinity beads with 4× SDS/PAGE sample buffer and analyzed by immunoblot.

The in Vitro Pull Down.

The in vitro pull-down protein–protein interaction assay was modified from that described (8). The coding sequence of CRY1 protein was expressed in Sf9 insect cells by using the baculovirus expression system. CRY1 was fused to the C terminus of the His tag, at the EcoRI and XhoI restriction sites of the vector pFastBacHTA (Invitrogen). PIF4 was expressed in E. coli by using the pCold-TF vector (Takara), and PIF4 was fused to the C terminus of the His-TF tag, at the EcoRI and SalI restriction sites. For pull down assays in white light condition, CRY1 protein expressed and purified under white light was incubated with the E. coli-expressed PIF4 protein under white light for 30 min. For blue light-dependent pull-down assays, CRY1 protein expressed and purified from insect cells under dark were incubated with PIF4 either under dark or under blue light conditions (40 μmol⋅m−2⋅sec−1) for 30 min. Anti-PIF4 antibody was used for the in vitro pull down, and this PIF4 antibody (Abiocode, no. 1307) can only detect the E. coli-expressed PIF4 protein but not the PIF4 in planta. BSA (1%) was added in each assay.

qPCR and GUS Assays.

Total RNAs were isolated by using the RNAiso Plus (Takara). cDNA was synthesized from 500 ng of total RNA by using PrimeScript RT Reagent Kit with gDNA Eraser (Takara). SYBR Premix Ex Tag (Takara) was used for qPCR reaction, using the MX3000 System (Stratagene). The level of ACTIN7 mRNA expression (AT5G09810; Table S1) was used as the internal control. The expression of GUS (β-glucuronidase) was analyzed as described (7).

Free IAA Measurement.

Free IAA measurements were performed as described (26, 58). The hypocotyls of 6-d-old WT and cry1 mutant seedlings grown at 20 °C and 28 °C in continuous white light were harvested for free IAA measurement. For the WT and cry1 seedlings grown at 28 °C, the 2-mm-length parts for each hypocotyl were harvested. Approximately 200 mg (fresh weight) of tissues were used for IAA extraction and measurement.

ChIP.

ChIP experiments for CRY1 and PIF4 were performed as described (7) by using 7 d-old WT seedlings or seedlings harboring PIF4-TAP grown under long-day conditions. Anti-CRY1 or monoclonal MYC antibody (Millipore, no. 05–724) were used in all experiments. Two grams of starting material was used to precipitate PIF4 or CRY1. Tissue was cross-linked with 1% formaldehyde (Sigma) for 20 min under vacuum.

Transient Transcription Dual-Luciferase (Dual-LUC) Assays.

Transient transcription Dual-LUC assays using N. benthamiana plants were done as described (7, 8). Protoplast isolation and PEG transformation was carried out as described (59). Three-week WT and cry1 plants grown in 12 h/12 h condition were used in this assay. Isolated protoplasts were transfected with a total of 20 μg of DNA (35S::PIF4-GFP and pGreen-YUC8Pro::LUC reporter) and incubated overnight. Protoplasts were harvested by centrifugation. The luciferase activity of plant extract was analyzed by a luminometer (Promega 20/20), using commercial LUC reaction reagents according to the manufacturer’s instruction (Promega).

EMSA.

The EMSA assay was as described (7, 8). The synthetic oligonucleotides (Table S1) were PCR amplified, and labeled with DIG (digoxigenin) by terminal transferase according to the manufacturer’s instruction (DIG Gel Shift Kit; Roche).

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Peter Quail, Dr. Xingwang Deng, Dr. Zhiyong Wang, Dr. Hongquan Yang, Dr. Hongwei Guo, and Dr. Giltsu Choi for kindly providing pfi1pif3pif4pif5 mutant and GUS-COP1, PIF4-YFP, MYC-CRY1, PIF3-MYC, and PIF4-MYC transgenic lines; Dr. Roger P. Hellens for the dual-LUC vector; Dr. Tom J. Guilfoyle for the DR5::GUS transgenic line; Drs. Yunde Zhao and Lin Li for other experimental materials used in this study; and Drs. Yunde Zhao and Gustavo Gomez for proofreading the manuscript. This work is supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China Grants 31270285, 31322006, and 91117016, and the Hundred Talents Program of Chinese Academy of Sciences.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1511437113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Cashmore AR. A cryptochrome family of photoreceptors. Plant Cell Environ. 1997;20:764–767. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lin C. Blue light receptors and signal transduction. Plant Cell. 2002;14(Suppl):S207–S225. doi: 10.1105/tpc.000646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sancar A. Structure and function of DNA photolyase and cryptochrome blue-light photoreceptors. Chem Rev. 2003;103(6):2203–2237. doi: 10.1021/cr0204348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Briggs WR, Huala E. Blue-light photoreceptors in higher plants. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1999;15:33–62. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.15.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ahmad M, Cashmore AR. HY4 gene of A. thaliana encodes a protein with characteristics of a blue-light photoreceptor. Nature. 1993;366(6451):162–166. doi: 10.1038/366162a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guo H, Yang H, Mockler TC, Lin C. Regulation of flowering time by Arabidopsis photoreceptors. Science. 1998;279(5355):1360–1363. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5355.1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu H, et al. Photoexcited CRY2 interacts with CIB1 to regulate transcription and floral initiation in Arabidopsis. Science. 2008;322(5907):1535–1539. doi: 10.1126/science.1163927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu Y, Li X, Li K, Liu H, Lin C. Multiple bHLH proteins form heterodimers to mediate CRY2-dependent regulation of flowering-time in Arabidopsis. PLoS Genet. 2013;9(10):e1003861. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu H, et al. Arabidopsis CRY2 and ZTL mediate blue-light regulation of the transcription factor CIB1 by distinct mechanisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(43):17582–17587. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1308987110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deng XW, Caspar T, Quail PH. cop1: A regulatory locus involved in light-controlled development and gene expression in Arabidopsis. Genes Dev. 1991;5(7):1172–1182. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.7.1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lian HL, et al. Blue-light-dependent interaction of cryptochrome 1 with SPA1 defines a dynamic signaling mechanism. Genes Dev. 2011;25(10):1023–1028. doi: 10.1101/gad.2025111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu B, Zuo Z, Liu H, Liu X, Lin C. Arabidopsis cryptochrome 1 interacts with SPA1 to suppress COP1 activity in response to blue light. Genes Dev. 2011;25(10):1029–1034. doi: 10.1101/gad.2025011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zuo Z, Liu H, Liu B, Liu X, Lin C. Blue light-dependent interaction of CRY2 with SPA1 regulates COP1 activity and floral initiation in Arabidopsis. Curr Biol. 2011;21(10):841–847. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.03.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ang LH, Deng XW. Regulatory hierarchy of photomorphogenic loci: Allele-specific and light-dependent interaction between the HY5 and COP1 loci. Plant Cell. 1994;6(5):613–628. doi: 10.1105/tpc.6.5.613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Christie JM, et al. Plant UVR8 photoreceptor senses UV-B by tryptophan-mediated disruption of cross-dimer salt bridges. Science. 2012;335(6075):1492–1496. doi: 10.1126/science.1218091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jiao Y, Lau OS, Deng XW. Light-regulated transcriptional networks in higher plants. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8(3):217–230. doi: 10.1038/nrg2049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Foreman J, et al. Light receptor action is critical for maintaining plant biomass at warm ambient temperatures. Plant J. 2011;65(3):441–452. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04434.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yi C, Deng XW. COP1 - from plant photomorphogenesis to mammalian tumorigenesis. Trends Cell Biol. 2005;15(11):618–625. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2005.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wigge PA. Ambient temperature signalling in plants. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2013;16(5):661–666. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2013.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kumar SV, Wigge PA. H2A.Z-containing nucleosomes mediate the thermosensory response in Arabidopsis. Cell. 2010;140(1):136–147. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huq E, Quail PH. PIF4, a phytochrome-interacting bHLH factor, functions as a negative regulator of phytochrome B signaling in Arabidopsis. EMBO J. 2002;21(10):2441–2450. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.10.2441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leivar P, Quail PH. PIFs: Pivotal components in a cellular signaling hub. Trends Plant Sci. 2011;16(1):19–28. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2010.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Castillon A, Shen H, Huq E. Phytochrome Interacting Factors: Central players in phytochrome-mediated light signaling networks. Trends Plant Sci. 2007;12(11):514–521. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kumar SV, et al. Transcription factor PIF4 controls the thermosensory activation of flowering. Nature. 2012;484(7393):242–245. doi: 10.1038/nature10928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koini MA, et al. High temperature-mediated adaptations in plant architecture require the bHLH transcription factor PIF4. Curr Biol. 2009;19(5):408–413. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.01.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sun J, Qi L, Li Y, Chu J, Li C. PIF4-mediated activation of YUCCA8 expression integrates temperature into the auxin pathway in regulating arabidopsis hypocotyl growth. PLoS Genet. 2012;8(3):e1002594. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Franklin KA, et al. Phytochrome-interacting factor 4 (PIF4) regulates auxin biosynthesis at high temperature. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(50):20231–20235. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1110682108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stavang JA, et al. Hormonal regulation of temperature-induced growth in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2009;60(4):589–601. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.03983.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nomoto Y, et al. A circadian clock- and PIF4-mediated double coincidence mechanism is implicated in the thermosensitive photoperiodic control of plant architectures in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 2012;53(11):1965–1973. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcs141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oh E, Zhu JY, Wang ZY. Interaction between BZR1 and PIF4 integrates brassinosteroid and environmental responses. Nat Cell Biol. 2012;14(8):802–809. doi: 10.1038/ncb2545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee HJ, et al. FCA mediates thermal adaptation of stem growth by attenuating auxin action in Arabidopsis. Nat Commun. 2014;5:5473. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Delker C, et al. The DET1-COP1-HY5 pathway constitutes a multipurpose signaling module regulating plant photomorphogenesis and thermomorphogenesis. Cell Reports. 2014;9(6):1983–1989. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.11.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Johansson H, et al. Arabidopsis cell expansion is controlled by a photothermal switch. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4848. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gould PD, et al. Network balance via CRY signalling controls the Arabidopsis circadian clock over ambient temperatures. Mol Syst Biol. 2013;9:650. doi: 10.1038/msb.2013.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kunihiro A, Yamashino T, Mizuno T. PHYTOCHROME-INTERACTING FACTORS PIF4 and PIF5 are implicated in the regulation of hypocotyl elongation in response to blue light in Arabidopsis thaliana. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2010;74(12):2538–2541. doi: 10.1271/bbb.100586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hornitschek P, Lorrain S, Zoete V, Michielin O, Fankhauser C. Inhibition of the shade avoidance response by formation of non-DNA binding bHLH heterodimers. EMBO J. 2009;28(24):3893–3902. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee J, et al. Analysis of transcription factor HY5 genomic binding sites revealed its hierarchical role in light regulation of development. Plant Cell. 2007;19(3):731–749. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.047688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Al-Sady B, Ni W, Kircher S, Schäfer E, Quail PH. Photoactivated phytochrome induces rapid PIF3 phosphorylation prior to proteasome-mediated degradation. Mol Cell. 2006;23(3):439–446. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leivar P, et al. The Arabidopsis phytochrome-interacting factor PIF7, together with PIF3 and PIF4, regulates responses to prolonged red light by modulating phyB levels. Plant Cell. 2008;20(2):337–352. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.052142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Griffin EA, Jr, Staknis D, Weitz CJ. Light-independent role of CRY1 and CRY2 in the mammalian circadian clock. Science. 1999;286(5440):768–771. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5440.768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hu CD, Chinenov Y, Kerppola TK. Visualization of interactions among bZIP and Rel family proteins in living cells using bimolecular fluorescence complementation. Mol Cell. 2002;9(4):789–798. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00496-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bai MY, et al. Functions of OsBZR1 and 14-3-3 proteins in brassinosteroid signaling in rice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(34):13839–13844. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706386104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gray WM, Ostin A, Sandberg G, Romano CP, Estelle M. High temperature promotes auxin-mediated hypocotyl elongation in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95(12):7197–7202. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.7197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Greenham K, et al. The AFB4 auxin receptor is a negative regulator of auxin signaling in seedlings. Curr Biol. 2011;21(6):520–525. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.02.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 45.Zhao Y. Auxin biosynthesis and its role in plant development. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2010;61:49–64. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042809-112308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Heyndrickx KS, Van de Velde J, Wang C, Weigel D, Vandepoele K. A functional and evolutionary perspective on transcription factor binding in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell. 2014;26(10):3894–3910. doi: 10.1105/tpc.114.130591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang Y, et al. A quartet of PIF bHLH factors provides a transcriptionally centered signaling hub that regulates seedling morphogenesis through differential expression-patterning of shared target genes in Arabidopsis. PLoS Genet. 2013;9(1):e1003244. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hellens RP, et al. Transient expression vectors for functional genomics, quantification of promoter activity and RNA silencing in plants. Plant Methods. 2005;1:13. doi: 10.1186/1746-4811-1-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ahmad M, Jarillo JA, Smirnova O, Cashmore AR. The CRY1 blue light photoreceptor of Arabidopsis interacts with phytochrome A in vitro. Mol Cell. 1998;1(7):939–948. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80094-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Más P, Devlin PF, Panda S, Kay SA. Functional interaction of phytochrome B and cryptochrome 2. Nature. 2000;408(6809):207–211. doi: 10.1038/35041583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ye R, et al. Dual modes of CLOCK:BMAL1 inhibition mediated by Cryptochrome and Period proteins in the mammalian circadian clock. Genes Dev. 2014;28(18):1989–1998. doi: 10.1101/gad.249417.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mockler TC, Guo H, Yang H, Duong H, Lin C. Antagonistic actions of Arabidopsis cryptochromes and phytochrome B in the regulation of floral induction. Development. 1999;126(10):2073–2082. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.10.2073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang H, Ma LG, Li JM, Zhao HY, Deng XW. Direct interaction of Arabidopsis cryptochromes with COP1 in light control development. Science. 2001;294(5540):154–158. doi: 10.1126/science.1063630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shin J, et al. Phytochromes promote seedling light responses by inhibiting four negatively-acting phytochrome-interacting factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(18):7660–7665. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812219106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Duek PD, Fankhauser C. HFR1, a putative bHLH transcription factor, mediates both phytochrome A and cryptochrome signalling. Plant J. 2003;34(6):827–836. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2003.01770.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sakuraba Y, et al. Phytochrome-interacting transcription factors PIF4 and PIF5 induce leaf senescence in Arabidopsis. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4636. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhong S, et al. A molecular framework of light-controlled phytohormone action in Arabidopsis. Curr Biol. 2012;22(16):1530–1535. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.06.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhou W, et al. Arabidopsis Tyrosylprotein sulfotransferase acts in the auxin/PLETHORA pathway in regulating postembryonic maintenance of the root stem cell niche. Plant Cell. 2010;22(11):3692–3709. doi: 10.1105/tpc.110.075721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yoo SD, Cho YH, Sheen J. Arabidopsis mesophyll protoplasts: A versatile cell system for transient gene expression analysis. Nat Protoc. 2007;2(7):1565–1572. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]