Abstract

Heterocyclic N-oxides have emerged as potent compounds with anticancer, antibacterial, antihypertensive, antiparasitic, anti-HIV, anti-inflammatory, herbicidal, neuroprotective, and procognitive activities. The N-oxide motif has been successfully employed in a number of recent drug development projects. This review surveys the emergence of this scaffold in the mainstream medicinal chemistry with a focus on the discovery of the heterocyclic N-oxide drugs, N-oxide-specific mechanisms of action, drug-receptor interactions and synthetic avenues to these compounds. As the first review on this subject that covers the developments since 1950s to date, it is expected that it will inspire wider implementation of the heterocyclic N-oxide motif in the rational design of new medicinal agents.

Keywords: Heterocyclic N-oxides, nitric oxide mimics, bioisosteres, hypoxia, factor Xa inhibitors, coagulation cascade direct thrombin inhibitors, antichagasic agents, antimalarials

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1. Background

Small organic molecules have been the mainstay of medicine and biology both as therapeutic agents and as probes used to investigate complex biological processes. [1, 2] Groups of structurally similar chemical agents that exert influence on these processes can be described as “privileged scaffolds”. [3] Modification of these frameworks by replacement [4, 5] of functional groups with bioisosteric units, [6] often results in an adjustment of pharmacological and physico-chemical properties, and can ultimately lead to development of new drugs. [7] Heterocyclic N-oxidation of N-heterocyclic bioactive compounds is an excellent example, where introduction of small structural changes (in this case – N-oxidation) can lead to improvement of the desired properties, and in some cases to emergence of unrelated but beneficial therapeutic outcomes. [8] Historically, heterocyclic N-oxides were often perceived as side products of hepatic metabolism of N-heterocyclic therapeutic agents. [9] Emergence of heterocyclic N-oxides in the mainstream drug development is partly credited to the unusual discovery of antihypertensive and anti-alopecia agent minoxidil by Upjohn in the early 1960s. Since then, a growing number of antibacterial, [10] antiviral (anti-HIV), [11] anticancer, [12] anti-protozoal [13] and anti-fungal [14] heterocyclic N-oxides have reached advanced drug discovery stages. In addition to pharmaceutical applications, a number of heterocyclic N-oxides have found use as agrochemicals [15] and also in cosmetics industry. [16]

1.2. Scope of the review

This review focuses on the discovery, biological activities, synthesis and some pharmacological profiles of heterocyclic N-oxide drugs and related emerging bioactive compounds. Topics related to the central theme, such as structure-activity relationships, historical perspectives and drug-receptor interactions will also be discussed. The review is organized according to the various heterocyclic N-oxide drugs and provides insights into the drug development process, as well as the current status of these agents.

2. GENERAL MODES OF ACTION OF BIOACTIVE HETEROCYCLIC N-OXIDES

2.1. Principal modes of action

Although the initial medicinal chemistry of heterocyclic N-oxides dates back to 1950, the full implementation of this scaffold in drug discovery is still at its infancy. There are several emerging areas, where these compounds hold significant promise. In particular, heterocyclic N-oxides have emerged as valuable anticancer, antibacterial, antihypertensive, antiparasitic, anti-HIV, anti-inflammatory, herbicidal, neuroprotective, and procognitive agents. There are four principal modes of action that distinguish the heterocyclic N-oxide motif with respect to each therapeutic area. The details of each mode of action are discussed vide infra in the sections dedicated to the corresponding bioactive agents.

2.2. Nitric oxide (NO) mimics

Nitric oxide (NO) is a small molecule that has been implicated in a number of important processes in living systems. These processes (including neuromodulation as well as neurotransmission) have been the subject of drug discovery research for several decades. Chemical moieties that are isoelectronic to nitric oxide have been shown to elicit NO-like functions. [17] For instance the N–O moiety in a variety of heterocyclic N-oxides can elicit nitric oxide-like effects, acting as a nitric oxide agonist. For instance, just like NO, minoxidil and its derivatives are potent ATP-dependent potassium channel openers. [18] Hence, the vasodilating and hypertrichosis activities of these drugs have been explained by these effects, e.g. in the case of minoxidil known to induce opening of K-ATP channels, leading to vasodilation and hair growth stimulation. [19]

2.3. Bioisosteres of the carbonyl group

The relatively high electron density of the heterocyclic N-oxide oxygen makes these compounds strong hydrogen bond acceptors. As a consequence, a number of heterocyclic N-oxide motifs have been used as potent bioisosteric replacements for the carbonyl function. For instance in the cases of direct thrombin as well as p38 MAP kinase inhibitors, the heterocyclic N-oxide motifs were shown to be superior over their carbonyl counterparts. [20] X-ray crystallographic data suggest that the N–O group forms critical hydrogen bonding networks, which cause conformational changes at the active site that lead to allosteric modulation of the enzyme function. In the case of thrombin inhibitors, replacement of the pyrazinone group with a pyridine N-oxide moiety led to superior inhibitory activities. [21] This review discusses further examples of heterocyclic N-oxides as bioisosteres for the carbonyl group section (3.4, 3.7).

2.4. Hypoxic-selective cytotoxins

Certain heterocyclic N-oxides, e.g. tirapazamines and their derivatives have been shown to undergo selective reduction to highly reactive free radicals under the action of multiple reductases. [22] These free radicals confer inherent cytotoxicity through DNA strand breaks and/or topoisomerase poisoning. [23] Recent research offers evidence of involvement of both hydroxyl and benzotriazinyl radicals in this pathway. [24] This review discusses the involvement of heterocyclic N-oxides as free radical sources during hypoxic-selective DNA damage sections (3.6, 3.8, 3.9 and 3.10).

2.5. Nitric oxide donors

A number of heterocyclic N-oxides, e.g. furoxans and diazetine N-oxides can be regarded as masked NO donors. Thus, under thiol mediation, these molecules have been shown to produce nitric oxide. [25] The nitric oxide released by these agents has been linked to the activation of the soluble guanylyl cyclase-cGMP pathway. [26] Consequently, there is a growing number of reports on the potential of these agents in the area of cardiovascular diseases. [27] The NO produced by these agents has also been shown to elicit neuroprotective and procognitive effects. [26] Furthermore, it has been shown that the furoxan moiety could be electronically modulated to produce controlled dosage of nitric oxide, which can be critical for nitric oxide therapeutics, especially since different dosages of nitric oxide can potentially produce different responses. [25] This review discusses some aspects of the N-oxide-mediated NO generation and the SAR (structure–activity relationship) studies of the NO donor N-oxides sections (3.8).

3. CASE STUDIES OF HETEROCYCLIC N-OXIDE DRUGS AND EMERGING BIOACTIVE COMPOUNDS

3.1. Minoxidil and kopexil

3.1.1. Introduction

Minoxidil (1) and kopexil (2) are both pyrimidine N-oxide drugs, whose development is a clear example of serendipity. Minoxidil is currently used for the treatment of any form of alopecia, – a condition characterized by hair loss, usually due to androgenic miniaturization. Kopexil on the other hand, can be viewed as a structural analogue of minoxidil, and is also known to treat alopecia. However, it has not been approved by the FDA and in most European countries, and there are no indications that an approval has been sought. Chemically, minoxidil and kopexil are 2,4-diamino pyrimidine-3-N-oxide with minoxidil containing a piperidinyl unit at C-6 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Minoxidil and structural analogues

3.1.2. Discovery of minoxidil

The development of minoxidil (1) as a drug dates back to the early 1960. [28] Researchers at Upjohn searched for an active agent that could lower the blood pressure in animal models (rats and dogs). In this quest, a large number of compounds were screened and N,N-diallylmelamine (3) emerged as the original lead compound. The discovery of N,N-diallylmelamine as the lead compound is very unusual, as it was initially developed as an additive to reduce photodegradation in plastics. Subsequently, it was tested against gastric ulcers.

Although the performance of compound 3 in the gastric ulcer tests was mediocre, compound 3 was found to lower the blood pressure in both dogs and rats. Subsequent structural optimization of 3 led to simplification of the melamine scaffold by omission of one of the nitrogen atoms in the aromatic ring and introduction of piperidinyl moiety. Interestingly, the Upjohn team was intrigued by the time lag between administration of the simplified version and the onset of action of the drug. As a result, it was postulated that the effective ingredient is most probably a product of hepatic metabolism. Detailed biochemical experiments revealed a hepatic oxidative modification of pyrimidine backbone, which indeed, was responsible for the antihypertensive activity. However, the exact nature and location of the oxygenated group in this molecule was unknown at the time. The results led the introduction of various oxygenation patterns into the lead compound. After several years of experimentation, the antihypertensive activity of the molecule was linked to the O-sulfated metabolite 4. [29] However, this analogue was highly unstable and too difficult to synthesize at that time. [30] The closely related N-oxide 2, whose activities were comparable to the O-sulfated analogue 4 made it through clinical trials. The drug was so potent that its administration was limited only to those cases, where other vasodilators failed. In addition to its antihypertensive activity, several cases of unusual side effects were reported, such as severe hair growth at unusual locations. This unexpected effect led to investigation of minoxidil as a possible treatment of hair loss, and the results from clinical trials strongly supported the observation.

3.1.3. Pharmacological characteristics of minoxidil and kopexil

Minoxidil is well absorbed unchanged from the gastrointestinal tract with levels reaching a maximum after 1 h of oral administration and declining rapidly with a serum elimination half-life of 1.1–4.2 h. [31] The rate of clearance of unchanged minoxidil has been estimated at 1584 mL/min. Reports also show that approximately 67% of minoxidil is metabolized in the liver via conjugation to glucuronic acid (that is via the formation of minoxil-o-glucuronide). [32] Also, 12–20% of the drug is excreted renally in unchanged form. Multiple experiments have identified that the magnitude of antihypertensive activity by this drug is related to the hypertension present, which implies, the blood pressure response declines with reduced blood pressures and there is little to no response at pretreatment diastolic blood pressure of 85 mmHg. Hence, minoxidil is known to have negligible hypotensive activity in healthy individuals. Reports also show that the concentration of minoxidil does not correlate well with the magnitude or duration of the elicited action. This effect has been explained to be partly due to the persistence of the drug at the receptor sites. Also, despite peak plasma concentration levels within 1 h, peak blood pressure reduction occurs within 2–8 h after oral administration, with a slow recovery of the action within 11 h to 5 days. Because of this effect, the drug is usually prescribed once daily.

3.1.4. Mechanism of action of minoxidil

The mechanism of action of minoxidil has been debated for a period of more than 30 years. Several theories have been postulated to explain the differences in the duration between peak plasma level of the drug and the onset of the elicited action. This disparity has been correlated partly to the residence time of the drug at receptor sites and also to the formation and involvement of an active metabolite. Several experiments have identified the O-sulfated minoxidil to be the active metabolite. [33] The conversion of minoxidil to its O-sulfated analogue in rats has been ascribed to the action of at least four enzymes known as sulfo-transferases. The activity of these enzymes has been demonstrated in animal models (rats), as well as in human liver, [34] platelets, [35] and the epidermal keratinocytes. [36] There are also reports of concrete biochemical evidence of the sulfation of minoxidil by transferases, which were isolated from human scalp skin. [37] In addition, there are reports showing mRNA expression of the sulfo-transferases in human epidermal keratinocytes. [38] In clinical settings, the levels of these enzymes have been reported to be higher in men, who responded to minoxidil treatment compared to those, who did not respond. [39] Therefore, it is logical to conclude minoxidil sulfate is the active metabolite responsible for antihypertensive activity, as well as hypertrichosis activity observed after administration of minoxidil. In addition, minoxidil and its O-sulfate metabolites have been shown to elicit nitric oxide-like activities. For instance, these drugs are known ATP-sensitive K-channel openers. The function of these channels has been linked to the control and regulation of vasodilation. [40] Thus, the mechanism of action of minoxidil may involve hepatic or epidermal keratinocyte sulfo-transferases-mediated conversion of parent minoxidil to its sulfate metabolite, which in turn causes the opening of the plasma membrane adenosine triphosphate (ATP)-sensitive potassium channels (K-ATP channels). The opening of this channel leads to relaxation of the vascular smooth muscles, and hence propagation of vasodilation. In addition to the smooth muscles, potassium channels are also located in a variety of tissues and cell types including cells of the heart, pancreas, and the central nervous system, where they couple intracellular metabolic variations to the electrical activity of the plasma membrane. The K-ATP channels are also widely recognized to be involved in hypertrichosis (severe hair growth). Thus, upon topical administration, the sulfo-transferases of the epidermal keratinocyctes convert minoxidil to it sulfated analogue. The sulfated analogue then interact with the K-ATP channels leading to relaxation of the vascular smooth muscles or triggering a cascade of events via the central nervous system. [40] This vasodilation leads to the increase of oxygenation and nutrients levels in blood and at hair follicles. This in turn triggers shortening of the telogen phase (resting phase) leading to premature entry of the resting hair follicle into anagen (active phase), which then results in hair thickening and growth. [16] Given the structural similarity of kopexil to minoxidil, it is believed that the mode of action of kopexil is also related to ATP potassium channel activation possibly through the formation of kopexil sulfate, although no detailed mechanism of action of kopexil has been elucidated.

3.1.5. Current uses of minoxidil and kopexil

Minoxidil is direct-acting peripheral arteriolar vasodilator, which is used orally only in the cases of severe hypertension. More than 95% of all minoxidil sold today is used by the cosmetic industry principally for hair restoration. It is sold under the trade name Loniten, when used to treat hypertension and as Rogaine (which is a 2 or 5% solution in propylene glycol), when used to promote hair regrowth, especially in male-pattern baldness. Other trade names include acvogain, regaine, lipogaine, avacor physician’s formulation and vanarx. Kopexil, on the other hand, which is marketed under the trade amnexil is known to elicit similar antihypertensive and hypertrichotic effects as minoxidil.

3.1.6. Synthesis of minoxidil

There are a number of methods of assembly of the pyrimidine N-oxide core that is shared by minoxidil and kopexil. One of the synthetic routes to minoxidil reported by Upjohn involves conversion of cyanomalonate to piperidinyl cyanomalonamide 5 by direct amidation using piperidine. [41] The resulting amide could be treated with trimethyloxonium tetrafluoroborate to afford the corresponding enol ether. The reaction of this enol ether affords enamine 6 which could be converted to minoxidil (1) via treatment with hydroxylamine (Figure 2). Alternatively, minoxidil (1) was synthesized from barbiturate 7, which was first treated with phosphoryl chloride and then ammonia to afford chloropyrimidine 8. Compound 8 was then be oxidized to N-oxide 10 and reacted with piperidine to give minoxidil (1). [42] In a modification of the procedure, chloride 8 was first reacted with 2,4-dichlorophenol, and then with piperidine to afford desoxyminoxidil (9) that was subsequently oxidized to minoxidil. [43]

Figure 2.

3.2. Chlordiazepoxide

3.2.1. Introduction

Chlordiazepoxide is another important and early example of a heterocyclic N-oxide drug. Chlordiazepoxide belongs to the benzodiazepine drug family (Figure 3). Benzodiazepines are known for their remarkable psychoactive properties, which result from their interactions with the neurotransmitter gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptor. [44]

Figure 3.

General structure of the benzodiazepines and chlordiazepoxide.

Chlorodiazepoixde is the first discovered member of this class of drugs. Some of the other members include: chlorazepate, diazepam (valium), flurazepam, lorazepam, oxazepam adinazolam and midazolam. Chlordiazepoxide is the only heterocyclic N-oxide benzodiazepine. It is marketed under the trade names Elenium, Angirex, Libotryp Lubrium Mesural, Multum, Novapam, Rosolid, Silibrin, Sonimen and Tropium.

3.2.2. Discovery of chlordiazepoxide

The discovery of the benzodiazepines in general and chlordiazepoxide in particular is credited to Leo Henryk Sternbach, who was working at Hoffmann-La Roche’s Research facility in Nutley, New Jersey. [45] As a postgraduate student while in Poland in the early 1930s, Sternbach engaged in the synthesis of several heptoxdiazine compounds, – a research which was geared towards the development of synthetic dyes. Inspired by the tremendous success in the development of chlorpromazine and early reports on meprobamate, Sternbach resumed research on his heptoxdiazines hoping to contribute to the emerging area of psychopharmacology in the mid-1950s.

In this quest, he re-characterized one of his heptoxdiazines and made a library of this class of compounds. However, pharmacological assays of these compounds as tranquilizers and sedative agents were largely unsuccessful. Compounds 13 were then reacted with primary amines in an effort to synthesize their amine derivatives 14 (Figure 4). In the midst of this work, questions arose on the exact structural identity of compounds 13 and 14. Further characterization of compounds 13 and 14 revealed that indeed compound 13 and 14 were misassigned as benzoheptoxdiazines, but were rather analogues of quinazoline N-oxides 15 and 16 respectively. Additional set of experiments involving mass analysis unequivocally confirmed that compounds 13 and 14 were actually quinazoline N-oxides. With this new slew of compounds further biological tests were carried out; however, the results were disappointing in the sedative and tranquilizer screenings, and the project was suspended. In the spring of 1957, during a laboratory cleanup, Sternbach and co-workers found a few hundred milligrams of crystals in the crystallizing dish used in 1955, which have been left during their synthesis of compound 16. It also came to his recollection that this compound had not been tested in 1955. Since this compound was pure, it was submitted for testing, although with the anticipation of a negative result. Surprisingly, the compound showed interesting properties in six tests that were commonly used for tranquillizer and sedative screening. [46] Puzzled by the disparity of the UV and IR spectra data of this compound with the quinazoline N-oxides synthesized earlier, Sternbach and co-workers decided to use chemical degradation studies to determine the correct structure of this compound (Figure 5). The degradation studies of the compound were carried out by first reducing with phosphorous trichloride and then by treatment of the mixture with an acid. Result showed that the lead compound was not a quinazoline N-oxide but benzodiazepine-4-oxide 12.

Figure 4.

General structure of benzoheptodiazines and other intermediates encountered in the discovery of chlordiazepoxide.

Figure 5.

Degradation studies of chlordiazepoxide. [46]

These exciting results led to the synthesis of a new set of benzodiazepine N-oxides. Unfortunately, none of these analogues had a superior activity compared to the initial lead. Sternbach and co-workers also reported that chlordiazepoxide easily hydrolyzed, and the hydrolysis product had a comparable activity. Active research in this field in the past four decades has led to a discovery of several additional benzodiazepines, some of which have been approved for clinical use.

3.2.3. Current uses of chlordiazepoxide

Chlordiazepoxide is used in the treatment of anxiety disorders including obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), phobia, and panic attacks. It is also used in the treatment of acute alcohol withdrawal and as a short-term relieve for fear and anxiety before surgery.

3.2.4. Pharmacological characteristics of chlordiazepoxide

Chlordiazepoxide is the first and only heterocyclic N-oxide member of the benzodiazepine drug family in clinical use. When administered orally, chlordiazepoxide is rapidly and completely absorbed, while intramuscular injection results in slow and erratic adsorption. Approximately 96% of the drug binds to plasma in the first 8 hrs and plasma elimination half-life in healthy individuals ranges from 5 to 30 hours. It is metabolized into a complex mixture of biotransformed pharmacologically active, demoxepam and desmethyldiazepam. It is also known that the active metabolite (desmethyldiazepam) has an elimination half-life 36 to 300 hours. This feature makes chlordiazepoxide a long circulating drug. The drug is excreted with urine both in the unchanged (1–2%) and conjugate (3–6%) forms. Multiple dose therapy with chlordiazepoxide leads to accumulation of the parent, as well as the active metabolites. The rate and extent of the accumulation is known to vary considerably and increases with age. [47]

3.2.5. Mechanism of action of chlordiazepoxide and related benzodiazepines

It has been known for several decades that all benzodiazepines elicit their effect via a centralized mechanism, which involves the allosteric modulation of the GABAA receptor function (Figure 6). [48] To fully understand this mechanism it is important to describe the nature of the binding events within this receptor. γ-Amino-butyric acid (GABA) is the main inhibitory neurotransmitter that controls the central nervous systems. Its receptor known as the γ-aminobutytyric acid receptor complex (GABAA complex) consists of five protein subunits that rings a central chlorine ion channel. The majority of these receptor subunits are α, β and γ, which are known to have different isoforms. [49] It has been demonstrated that these isoforms are responsible for the different sensitivities of different benzodiazepines. [50] GABA binds to the β subunits and most benzodiazepines bind at the interface of the γ subunit and any of the α1, α 2, α3, or α5 subunits. [51] It is also known that benzodiazepines with affinity for α1 subunit elicit sedative activity while those with affinity for the α2, or α3, subunits produce anxiolytic effects. [52]

Figure 6.

γ-Aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptor complex

(Reprinted with permission from Ref. 53. Copyright 2008 Nature Publishing Group).

Some studies have also showed that binding to the α5 subunit plays a major role in memory processes. [54] The chloride ion channel is controlled by the GABA binding site on this receptor. When GABA binds to its receptor, a conformational change in this receptor favors the entry of chloride ions into the cell through the channel. This results in hyperpolarization of the cell membrane, consequently increasing the threshold and inhibitory effect on action potential. Thus, binding of chlordiazepoxide to the GABAA receptor complex (at the interface of the γ and any of α2, or α3) induces an allosteric modulation at the receptor sites, which locks the receptor into a conformation for optimal GABA binding. [55] This results in the amplification of the inhibitory effect hence dampened emotions and relaxation of muscles. [52]

3.2.6. Synthesis of chlordiazepoxide

The synthesis of chlordiazepoxide published by Sternbach and co-workers in 1961 is still used today for the synthesis of analogues of this compound (Figure 7). The synthesis starts with the reaction of 2-amino-5-chlorobenzophenone 21 with hydroxylamine to form oxime 22. Treatment of oxime 22 with chloroacetyl chloride in the presence of acetic acid produces quinazoline N-oxide 16, which was first observed during the development stages of this drug. Finally, methylamine treatment of 16 results in chlordiazepoxide through an interesting ring expansion.

Figure 7.

Synthetic route to chlordiazepoxide. [56]

3.3. Otamixaban: direct factor Xa inhibitor

3.3.1. Introduction

Otamixaban 26 is a small molecule experimental antithrombotic agent, discovered by Sanofi. It is used for the management of acute coronary syndrome (ACS). Like other thromboembolic diseases, ACS, is characterized by obstruction of the coronary arteries due to inappropriate formation of a thrombus. Otamixaban is known to elicit its effects through reversible direct inhibition of a critical serine protease coagulant factor Xa (FXa). [57] This coagulant factor is located at the confluence of two important pathways: the contact activation pathway (intrinsic) and the tissue factor pathway (extrinsic) of the blood coagulation cascade. FXa catalyzes activation of prothrombin to thrombin via the prothrombinase complex. The activation of thrombin potentiates a cascade of events leading to the formation of a blood clot. [58] Thus FXa is an important pharmacological target for modulating thrombosis in vertebrates. Chemically, otamixaban belongs to the class of amidine-containing direct FXa inhibitors, which are designed to mimic the arginine residue of the natural substrate prothrombin. This compound 26 contains a 4-carbomoylphenyl 4-pyridine N-oxide that is connected via a peptide bond to a benzamidinyl β-aminoester unit 26.

3.3.2. Discovery of otamixaban

The discovery of otamixaban as a direct inhibitor for factor Xa (FXa) started with the identification of β-lactam compound 23 and evolved through the stages of N-p-nitrobenzamido-β-amino acid 24, then the main lead compound 25, and, finally heterocyclic N-oxide 26 (otamixaban) that had superior properties and activity profiles (Figure 8). [8]

Figure 8.

Discovery of otamixaban (26).

3.3.3. Action on the blood coagulation cascade

Blood coagulation in vertebrates is a complex series of orchestrated processes involving plasma proteins, serine protease enzymes and cellular receptors that play dynamic roles in providing delicate balancing acts leading to thrombosis and hemostasis (Figure 9). [59] The interior of blood vessels are lined by cells of the endothelium. These cells are specially designed to execute two functions: to promote blood fluidity [60] or in the case of a tissue injury, they act to promote blood coagulation at the wound site through the mediation of a cascade of enzymes and cofactors, and also prevent excessive propagation of this coagulation beyond the site by a feedback regulatory mechanism. In the case of injury, vessel disruption or cytokine inflammatory stimulation, bleeding occurs. Hemostatic plug formation is initiated upon exposure of the subendothelium at the injured site. Vasoconstriction of this region occurs due to the release of a protein known as thromboxane A2 (a major enzymatic product from platelet activation, which causes vessel walls to constrict). [61] Another protein known as von Willebrand factor (VWF) which is secreted by the endothelial cells, binds to exposed collagen fibers of the site. Platelets then adhere to the site through their interaction with the bound von Willebrand factor. Additional platelets are activated, and deposit around the site by a process known as platelet aggregation. Fibrinogen molecules form bridges between adjacent platelets, which accrue the area until all bleeding stops. The unstable loosely aggregated platelets and fibrinogen must then be consolidated. This is achieved through generation of thrombin (via the coagulation cascade) at the injured site. A glycosylated protein known as tissue factor (TF), which is released from subendothelial stores and the platelets initiates the coagulation cascade. [62] When the tissue factor (TF) binds to another protein factor VII in a 1:1 ratio, an activated complex known as TF-FVIIa is formed via limited proteolysis. The tissue TF/VIIa complex can then convert factor X or factor IX to their corresponding activated serine proteases via cleavage of an activation peptide (i.e. factor Xa or factor IXa). This marks initiation of the coagulation cascade and once the pathway starts, activation of factor X is immediately stopped by an inhibitor produced by the endothelial cells, known as tissue factor pathway inhibitor (TFPI). [63] The activated factor IXa formed by TF/FVIIa now binds to its cofactor known as factor VIIIa, which is usually located on phospholipid surfaces. The binding of factor IXa to factor VIIIa results in further activation of factor X to factor Xa. The activation of FXa initiates what is known as the common pathway for thrombin activation. This factor Xa binds its cofactor, factor Va and together with calcium ions on phospholipid surfaces forms prothrombinase complex. [64] This enzyme complex catalyzes the conversion of prothrombin to thrombin by cleavage of an activation peptide. The formation of minute amounts of thrombin has been shown to be enough to start the coagulation mechanism. Thrombin can also be formed via an intrinsic mechanism, whereby small amount of thrombin activates factor XI to factor XIa. Then factor XIa and factor VIIIa can activate factor X to factor Xa. This model of the coagulation cascade explains how thrombin activates two important cofactors, – factor V and factor VIII. The activation of factors V and VIII by thrombin result in further amplification of the coagulation activity via increased activity of prothrombinase complex. Fibrinogen, the main structural protein element of blood clot, is produced in the liver as dimeric units composed of three pairs of protein chains Aα, Bβ and γ, known to be linked at their N-termini. [65] Fibrinogen contains three globular domains, a central E domain connected by two identical D domains. Thrombin from the above cascade cleaves small peptides on fibrinogen known as fribinopeptides A and B from the Aα, and Bβ chains respectively. This ultimately leads to the formation of fibrin monomers that assemble into half-staggered, side-to-side fashion (known as protofibrils) stabilized by nonbonding interactions between the fibrin molecules. The protofibrils merge laterally into thicker fibrin and form unstable fibrin clots. The clot is finally stabilized by the action of thrombin that activates factor XIII to factor XIIIa. Factor XIIIa then form a peptide bond between the glutamic acid and lysine side chains in fibrin to create some permanence in the fibrin fibers.

Figure 9.

A model of the coagulation cascade highlighting the otamixaban inhibition of factor Xa.

In addition, factor XIIIa covalently crosslinks plasminogen and antiplasmin (e.g alpha-2-antiplasmin) in forming a fibrin clot. [66] This feature of factor XIIIa is important in finalizing the wound healing and tissue repair process. There are regulatory mechanisms that limit and clear a blood clot at the injury sites after healing. The clot removal process known as fibrinolysis involves a zymogen (plasminogen), a number of activators and several inhibitors. One of the most important of these activators is the tissue plasminogen activator (tPA), a product of the endothelial cell. During coagulation, plasminogen produced in the liver is entrapped within the crosslinked clot. tPA and other enzymes convert plasminogen to plasmin, which interacts with antithrombin III resulting in the breakdown of the blood clot. [67]

The regulation of the coagulation cascade can also be initiated when thrombin binds to the endothelial cell receptor known as thrombomodulin. Once thrombin binds to thrombomodulin receptor, its ability becomes limited to two pathways, one of which is the protein C pathway. The thrombin/thrombomodulin receptor complex activates protein C to its active form. The active form of protein C together with its co-factor protein S and calcium ions deactivates factors Va and VIIIa. Once these factors are deactivated, any further clot growth is prevented, thus concluding the coagulation cascade. Individuals with disorders caused by malfunctioning of the regulatory process described above may develop one of the following thromboembolic diseases: pulmonary embolism (PE), acute coronary syndrome (ACS), and deep vein thrombosis (DVT). These disease conditions result from thrombus formation in the coronary arteries, pulmonary veins, and the deep veins respectively. At present, treatment of any form of thromboembolic disease includes intravenous heparin, low molecular weight heparins (LMWH), oral vitamin K antagonist (coumadin), intravenous glycoprotein IIb/IIIa antagonists, and direct thrombin inhibitors (argatroban and bivalirudin). These current therapies have certain limitations with respect to safety and efficacy. [68] As a result, development of alternative methods to combat these deadly diseases has been pursued. It is important to note that within the coagulation cascade, the only entry point leading to the formation of thrombin involves factor Xa.

Thus, development of direct inhibition of factor Xa represents an important strategy of pharmacological intervention. Heterocyclic N-oxide drug otamixaban was developed as a specific direct inhibitor of factor Xa. The development of otamixaban commenced in 1994 with the first unsuccessful attempt in screening a large compounds library at Rhone-Poulenc Rorer, now known as Sanofi-Aventis. After this failure to identify any lead compound with a Factor Xa inhibitory activity, the company adopted a more rational strategy, which was based on the results from identification of a previously discovered potent inhibitor of serine protease elastase. [69] Since factor Xa is also a serine protease, it was hypothesized that β-lactams 27 would act as suicide inhibitors of FXa (Fugure 10). The important structural elements in this β-lactam design include introduction of a meta-substituted benzamidine unit and an N-p-nitrobenzoyl substitution, as in compound 23. The N-p-nitrobenzoyl group in 23 was expected to activate the β-lactam moiety towards irreversible acylation of Ser195, which is located at the active site of FXa, hence, disabling the enzyme.

Preliminary in silico docking experiments revealed that both the styryl side chain and the p-nitrobenzoyl groups satisfy the expected binding requirements for FXa. The synthesis of racemic compound 23 was thus carried out. It commenced with the construction of the β-lactam moiety in 23. This unit was synthesized by condensation of thiopyridyl ester 28 and imine 29 (Figure 11). This reaction afforded the desired β-lactam intermediate 30 as a 95:5 mixture of trans and cis isomers. [70] The oxidative removal of the p-methoxybenzyl unit afforded β-lactams 31a and 31b, which were easily separated. Compound 31a (trans) was then acylated with p-nitrobenzoyl chloride to give diamide 32a. All attempts to convert 32a to the desired amidine target resulted in the opening of the labile β-lactam unit leading to acid 24a. [8] Interestingly, compound 24a showed inhibitory activity against human FXa at submicromolar levels (Ki = 2.4 μM). In addition, the simplified racemic ester 25 that lacked the nitro group, caused inhibition of FXa with Ki 0.34 μM. The enantiomers of 25 were resolved and tested independently, and the results showed that isomer 25 (trans) inhibited FXa with Ki = 0.16 μM, while 25 (cis) had no activity against FXa. At that point, lactam 25 (trans) began to be considered as the lead compound. The identification of the main lead compound 25 (trans-diastereomer), led to the investigation of its absolute configuration and also an optimized asymmetric method for the synthesis. The absolute configuration of the active enantiomer was established to be 2R,3R, and the methyl ester function was also found to be necessary for the binding to FXa. In addition to the methyl ester as in the lead compound 25, a biphenyl moiety (compound 35) showed further increase in the inhibitory activity. The reduction of the olefinic unit in the styryl moiety to give ester 36 did not improve the activity. Further structure activity relationship studies revealed that the styryl moiety in 35 could be replaced with a smaller methyl group without a compromise in the inhibitory activity (Figure 12). [71] Thus, a program directed towards the synthesis of analogues with variability in the benzoyl unit but with conservation of the ester and benzamidine units was initiated.

Figure 11.

First attempted synthesis of β-lactam 23. [70]

Figure 12.

Synthesis of otamixaban analogues. [71]

The new analogues were tested in the factor IIa and trypsin inhibitory activity assays. The synthesis of these analogues was carried out using an optimized procedure, which resulted in the synthesis of the active enantiomer. The details of this synthetic strategy are discussed in section 5 below). Since most of the analogues showed significant activity against trypsin, the ratio of Ki for trypsin to that of FXa was also established as a yardstick for activity selection. Table 1 summarizes some of the results for selected analogues. It is worth noting that the introduction of electron-deficient or basic groups onto the biphenyl moiety in compound 38 led to the significant improvement in the activity against FXa, as well as selectivity, as seen for compounds 39 and 40. The introduction of imidazole showed improved selectivity, albeit with a reduction in the FXa activity. Other electron-deficient groups of the pyridine class showed some dramatic increase in the potency, as illustrated by compounds 26, 42–45. The best results were obtained for compound 26 (otamixaban) that contains 4-pyridyl N-oxide unit.

Table 1.

Optimization studies leading to development of otamixaban. [72]

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compounds | R | Ki(FXa) (nM) | Ki(FIIa) (nM) | Ki(Trypsin) (nM) | Ki(trypsin)/Ki(FXa) ratio |

| 38 |

|

5.3 | 3,250 | 69 | 13 |

| 39 |

|

1.0 | 2,650 | 69 | 69 |

| 40 |

|

3.0 | 3,950 | 170 | 57 |

| 26 |

|

0.5 | 4,000 | 300 | 600 |

| 42 |

|

2.0 | >4,000 | 130 | 65 |

| 43 |

|

0.58 | >4000 | 36 | 62 |

| 44 |

|

0.5 | >4,000 | 76 | 152 |

| 45 |

|

2.7 | >4,000 | 168 | 62 |

This compound was then chosen for the advanced stages of the drug development.

The X-ray structure of compound 26 (otamixaban) in the active site of FXa was obtained (Figure 13). [72]

Figure 13.

X-ray structure of otamixaban in FXa active site highlighting water bound via N-oxide moieties (represented by red spheres)

(Reprinted with permission from Ref. 72. Copyright 2002 Elsevier Science Ltd.).

Otamixaban 26 binds in a fully extended conformation, showing a bridging hydrogen bonding between Asp189 with the benzamidine moiety. This benzamidine moiety also hydrogen bonds to the carbonyl oxygen of Gly219. Other interactions in this pocket include hydrogen bonding between the amide carbonyl oxygen from the inhibitor and the NH of Gly219 and extensive van der Waals association between Try99, Phe174 and Trp215 with pyridine N-oxide ring. The N-oxide moiety is also hydrogen bonded to water (purple circles), and the combination of all these favorable interactions is responsible for the excellent potency and selectivity of otamixaban. [72]

3.3.4. Current status of otamixaban

Otamixaban is an experimental drug, which was intended for treatment of Non-STE acute coronary syndrome (NSTE-ACS). However, the drug did not perform better than current therapy with heparin and Merck’s Integrilin (eptifibatide) in reducing mortality or new heart attacks in patients with non-ST elevation acute coronary syndrome (NSTE-ACS). Hence, otamixaban has been withdrawn from clinical trial. [73]

3.3.5. Pharmacological characteristics of otamixaban

The in vitro pharmacological profile of otamixaban 26 characterized by Chu and coworkers revealed a highly selective inhibitory activity against FXa compared to the other relevant serine protease. [72] The inhibitory activity (Ki) of compound 26 for FXa and the other serine protease are 0.5 nM (FXa), 3956 nM (thrombin, FIIa), 301 nM (trypsin), >18491 nM (activated protein C, APC), 656 nM (plasmin), and 8681 nM (tissue plasminogen activator, tPA). The selectivity measured as a ratio of Ki of enzyme normalized to Ki of FXa are 1, >7900, 600, >36000, 1300 and > 17000 for the respective enzymes. [74] In addition, these studies also showed that the introduction of the N-oxide significantly increased the inhibitory activity and selectivity for FXa compared to the biphenyl and the pyridine derivatives. The inhibitory effect of otamixaban on the physiologically relevant complex of prothrombinase/FXa at phosphilipid interface and platelets in the presence of calcium and FVa was studied. The results revealed a dose dependent inhibitory activity for thrombin generation with IC50 = 1.38 nM for prothrombinase/FXa and 2.55 nM for platelets, respectively. Experiments performed to assess otamixaban anticoagulation response in different species show that the anticoagulation response decreases in the order rabbits > humans > primates > rats and dogs. [72] In particular, humans are 2.5 times more sensitive to compound 26 compared to dogs. Other experiments performed to quantify the effect of compound 26 on platelets aggregation revealed that it has no inhibitory effect on platelet aggregation up to 100 μM concentration. [72] This experiment suggested that otamixaban therapy would not affect normal primary hemostasis and could offer some inherent advantage (e.g. reduced risk of bleeding).

3.3.6. Synthesis of otamixaban

The asymmetric synthesis of otamixaban started with deprotonation of β-amino- ester 46 followed by alkylation with 3-cyanobenzyl bromide (Figure 14). [72] Upon treatment with benzoic acid the reaction mixture furnishes the benzoate salt of amino ester 47. The reaction mixture is then basified and subjected to a peptide coupling reaction with 4-(4′-pyridinyl)benzoic acid. This sequence afforded 48, which was oxidized to N-oxide 49. The nitrile was then converted into benzamidine by way of acid-mediated methanolysis followed by a reaction with ammonia.

Figure 14.

Synthesis of otamixaban. [72]

Reaction conditions: (a) i) LiHMDS, THF, −20 °C; ii) 3-cyanobenzyl bromide; iii) benzoic acid, water/toluene. (b) i) aq. Na2CO3; ii) 4-(4′-pyridinyl)benzoic acid; iii) TBTU, NMM, DMF. (c) MMPP, CH2Cl2/H2O. (d) i) HCl/MeOH; ii) NH3.

3.4. Pyridine N-oxide derivatives: emerging direct thrombin inhibitors

3.4.1. Discovery of pyridine N-oxide direct thrombin inhibitors

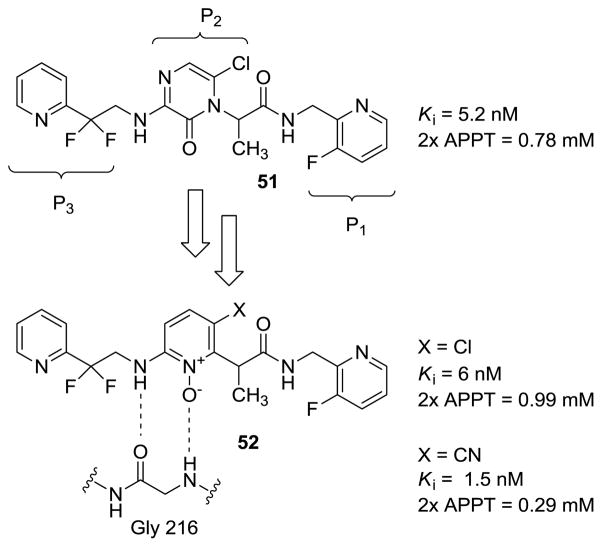

Thromboembolism is one of the major causes of morbidity and mortality worldwide. Thus, new strategies to combat this disease have been actively sought in the past several decades. In addition to the growing number of direct factor Xa inhibitors, such as otamixaban, there is also interest in the development of direct thrombin inhibitors. Towards this end, pyrazinone-based small-molecule peptidomimetics have been reported as direct thrombin inhibitors (Figure 15). [21] However, these molecules suffered from extensive metabolic oxidation that adversely affected their pharmacological profiles. [75] To address this issue, pyridine N-oxide was proposed as an alternative functional group that can retain the critical hydrogen-bonding network with Gly216 in the active site of the enzyme. Thus, the original pyrazinone core was replaced by pyridine N-oxide, which was shown to resist metabolic oxidation that plagued the pyrazinones. [76]

Figure 15.

Evolution of pyridine N-oxide class of thrombin inhibitors.

(2× APPT refers to the ability to double the activated partial thromboplastin time in human plasma

Derivatives with pyridine N-oxide ring bearing electron deficient substituents, such as Cl and CN, exhibited higher inhibitory activity. It was also shown that the non-N-oxide derivatives were much less potent than the corresponding N-oxides lending support to the proposed model that entails active participation of the N-oxide unit in hydrogen-bonding.

To further test this hypothesis, the X-ray structure of one of the inhibitors in the active site of the enzyme was obtained. Indeed, the structure clearly demonstrated the proposed hydrogen-bonding network with Gly-216 within the active site (Figure 16).

Figure 16.

X-ray structure of thrombin inhibitor 53 in the thrombin active site

(Reprinted with permission from Ref 76. Copyright 2005 Elsevier Ltd.).

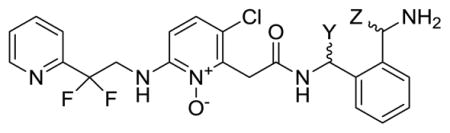

Further SAR studies were carried out with the goal of optimization of the P1 groups on the already optimized P2 template (Table 1). Towards this end, several compounds were synthesized and evaluated for their thrombin inhibitory potency and also for their functional ability to double the activated partial thromboplastin time (2× APPT) in human plasma. [77] The native unsubstituted benzyl amide 54 (Ki = 150 nM) was chosen as the starting point. The introduction of an N-linked triazole function in the ortho-position of the benzyl group afforded inhibitors with both good intrinsic and functional potency. Upon installation of a 2-aminomethyl substituent 55 significant improvement in potency was observed. Furthermore, introduction of meta-chloro substituent also yielded significant improvement in intrinsic potency. However, studies have shown that increase in lipophilicity of this inhibitor leads to erosion of functional activity [78] as a result these analogues were not considered. The combination of the ortho-azole and the meta-chloro substituents yielded very potent thrombin inhibitors 56. For instance compound 61 displayed a 1 pM Ki against thrombin, with a 2× APTT of 70nM. Similarly, this additive effect was also observed with other aminomethyl and chlorine substituents. Compound 61 showed the highest potency amongst all of the analogues synthesized. [76]

3.4.2. Pharmacological properties of P2 pyridine N-oxide direct thrombin inhibitors

The pharmacokinetics of the pyridine N-oxide thrombin inhibitors were evaluated orally using dogs as animal models. [76] Thus, oral administration of compound 57 showed peak plasma levels of 0.82 mM and a half-life of 1.5 hr, while peak plasma levels of 0.7 mM with t1/2 of 1.3 hr were attained for compound 59. All other analogues displayed inferior pharmacokinetics profiles. Hence, further structural optimization of the P1 unit was focused on the aminomethyl analogues 57 and 59. Metabolic studies of these analogues using human and dog microsomes showed that the benzylic sites were susceptible to oxidation and N-dealkylated metabolites were formed as primary products.

Attenuation of this oxidative metabolism was achieved with α-methyl benzylic analogues 62–65 and 66. The more active analogue 63 displayed approximately 8-fold loss in binding potency compared to compound 62, but maintained good anticoagulant activity (Ki = 3.2 nM, 2× APTT = 360 nM). This structural modification indeed translated into desirable improvement in the pharmacokinetic profile (Cmax = 2.6 μM, t1/2 = 4.5 hr). Other structural modifications (Table 3) did not lead to any improvement in the overall pharmacological profile. Hence, compound 63 was the best analogue that showed a perfect balance between potency and pharmacokinetics. The increase in binding potency of compound 65 and 66 compared to compound 54 has been attributed to the hydrogen bonding participation of Ser195 of the active site and the P1 substituent on these inhibitors.

Table 3.

Pharmacological profiles of pyridine N-oxide direct thrombin inhibitors 62–66. [76]

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | Y | Z | Ki (nM) | 2× APTT | Cmax (μM) | t1/2 (hr) |

| 46 | H | H | 0.4 | 0.13 | 0.82 | 1.5 |

| 62 | Me | H | 260 | __ | __ | __ |

| 63 | Me | H | 3.2 | 0.36 | 2.6 | 4.5 |

| 64 | H | Me | 20 | 5.9 | __ | __ |

| 65 | H | Me | 0.45 | 0.27 | 0.1 | 2.0 |

| 66 | CH2OH | H | 0.48 | 0.23 | 0.34 | 1.5 |

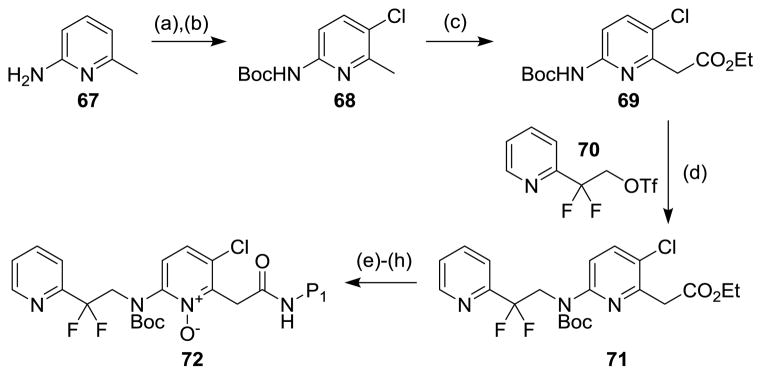

3.4.3. Synthesis of P2 pyridine N-oxide thrombin inhibitors

These inhibitors were synthesized starting with the Boc-protection of 2-amino-6-methylpyridine 67 followed by regioselective chlorination to give chloropyridine 68 (Figure 17). [76] Compound 68 was metallated at the 2-methyl group with LDA and then treated with diethyl carbonate to give pyridyl acetate 69. Alkylation of compound 69 with 2,2-difluoro-2-(2-pyridyl)ethyl-trifluoromethanesulfonate (70) established the P2–P3 subunits of compound 71. Ester hydrolysis and the carbodiimide-mediated attachment of the P1 units were followed by Boc-deprotection and N-oxidation to give the P2 pyridine N-oxide thrombin inhibitors of type 72. The cyano derivatives could be similarly prepared starting with 2-amino-5-cyano-6-methyl pyridine.

Figure 17.

Synthesis of P2 pyridine N-oxide direct thrombin inhibitors. [76]

Reaction conditions: (a) Boc2O; (b) NCS, DCE. (c) LDA, diethyl carbonate, THF. (d) NaH, DMF. (e) 1N LiOH, THF. (f) P1-NH2, EDCl, HOAt, DMF. (g) TFA, CH2Cl2; (h) mCPBA, DCE.

3.5. Ancriviroc: HIV-1 entry inhibitor

3.5.1. Introduction

Ancriviroc 75 is a heterocyclic N-oxide investigated as an HIV-1 entry inhibitor. Current approaches to the management of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) involve use of combinations of reverse transcriptase, integrase and protease inhibitors. [79] An important area of the antiretroviral drug development includes the point at which the virus enters its host cell. It has been known that HIV-1 enters the targeted macrophages and T-cells through the interaction of its gp120 and gp41 with the CD4 antigen receptors on the surface of the cells. In addition to the interaction with the CD4 receptors, there is also the participation of an important co-receptor known as CXCR4 in T-lymphocytes, and CCR5 in macrophages (Figure 18). [80] These co-receptors belong to the G-protein-coupled-receptor superfamily for which small molecule antagonists have been developed.

Figure 18.

Attachment of HIV to a CD4+ T-helper cell: (1) the gp120 viral protein attaches to CD4. (2) gp120 variable loop attaches to a co-receptor, either CCR5 or CXCR4. (3) HIV enters the cell. [81]

(Source: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases).

The native ligands to CCR5 include chemokines RANTES, MIP-1α and MIP-1β, which are known to inhibit the HIV-1 infection. [82] It has also been reported that many individuals, who are HIV positive but do not develop AIDS, have a mutation in the CCR5 receptor that makes the receptors defective, thus preventing the viron entry. [83] This finding lends support to the hypothesis that inhibition of CCR5 can provide protection against HIV-1. This discovery spurred efforts towards the development of small molecule antagonists for CCR5. [84] Amongst them, is the heterocyclic N-oxide known as ancriviroc (75), which was first reported by Schering-Plough in 2002. [85]

3.5.2. Discovery of ancriviroc as a CCR5 antagonist

The discovery of ancriviroc started with the screening of a large number of compounds from Schering-Plough’s compound library using the high-throughput 125I-labeled RANTES binding assay. [85] This effort led to the identification of compound 73 which was a CCR5 receptor antagonist with Ki = 1.0 μM (Figure 19). However, this compound was a more powerful antagonist for muscarinic M2 receptor (Ki = 1.3 nM). The initial efforts in this discovery were directed towards suppressing the muscarinic antagonism, while at the same time increasing antagonism for CCR5 receptor. Further structure activity relationship studies led to the refinement of the original structure, and, ultimately to the discovery of compound 74 (Ki(CCR5) = 66 nM; Ki(M2) = 1323 nM). [86]

Figure 19.

Discovery of ancriviroc.

The investigation of the effect of the position and identity of the substituents on the phenyl ring revealed that the para-position was optimal and other oxygenated and halogen substituent could be used in place of bromide. The results showed that p-chloro, p-iodo and some oxygen containing small groups had similar potency as compound 76 (Table 4). [85] However, their oral bioavailability was poor. This was linked to the possibility of oxidative metabolism at the benzylic sites. As a result, SAR studies were focused on introducing moieties at this benzylic site that would either block or reduce its metabolic involvement. Optimization studies revealed that a methoxime linker improved both the CCR5 antagonist potency (by 6-fold) and the blood plasma levels. These studies also show that the alkyl groups on the oxime function were limited to methyl and ethyl, as bigger groups led to decrease in potency. The Z-oxime isomer was more potent than the corresponding E-isomer. After the optimization of the geometry and alkyl substitution on the oxime, efforts were focused on the possible metabolic outcome of the drug. Experiments showed that the dimethylbenzamide moiety as in compound 74 was severely metabolized by the liver into a number of oxidized metabolites. The replacement of the methyl groups at the 2,6-positions led to a slight decrease in CCR5 binding potency. However, upon changing the benzamide to a nicotinamide, while maintaining the 2,6-dimethyl substituents, gave a potent CCR5 antagonist with significantly improved rat plasma levels after oral administration. Other substituents in the nicotinamide moiety did not increase either binding potency or bioavailability of the drug. Further metabolic studies of this analogue showed that the nicotinamide unit was significantly less metabolized compared to the 2,6-dimethylbenzamides. However, a major metabolite emerged with (M+16) mass unit. This was interpreted as N-oxidation of the nicotinamide core. This observation necessitated the expansion of the library by synthesis of new analogues with different N-oxide patterns. Further testing revealed that the new analogue compound 75 exhibited 2- to 3-fold higher oral plasma levels in the rat pharmacokinetic screen and also possessed increased binding potency. Compound 75 was, therefore, selected for advanced clinical studies.

Table 4.

Optimization of the CCR5 antagonists en route to ancriviroc. [85]

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compounds | Ar1 | R2 | Ki (nM) | IC50 | Rat PK (10 mg/kg PO) AUC0–6 (hr μg/mL) |

| 76 |

|

Me | 2.0 | 1.2 | 1.4 |

| 77 |

|

Me | 18 | 4 | 3.0 |

| 78 |

|

Me | 1.1 | 0.5 | 1.9 |

| 79 |

|

Et | 1.1 | 0.2 | 2.1 |

| 80 |

|

Et | >30 | NA | NA |

| 75 |

|

Et | 2.1 | 0.6 | 6.5 |

| 81 |

|

Et | 16 | 1.7 | 3.2 |

| 82 |

|

Et | >30 | NA | NA |

3.5.3. Pharmacological characterization of ancriviroc

The pharmacological profile of ancriviroc has been characterized in animal models (rats, monkeys and dogs) by Palani and co-workers. [87] The results showed that compound 75 is well absorbed in both rats and monkeys with oral bioavailability of 63% in rats, 52% in monkeys and 92% in dogs. The peaks plasma concentration of compound 48 at 12 and 24 h after oral administration were 330 and 16 nM in rats and 300 and 40 nM in monkeys respectively. The main route of excretion was found to be through urine for dogs and rats and through the bile in monkeys. The excreted metabolite was shown to the de-ethylated oxime, and no E/Z-isomerization of the oxime was observed in vivo. In addition, compound 75 showed negligible affinity (less than 15% inhibition at concentrations of 2–20 μM) for muscarinic M2 receptors or to the other closely related chemokine receptors, which include CCR1, CCR2, CCR3 and CCR7. [88] Despite the favorable potency and pharmacological characteristics, ancriviroc was withdrawn from clinical trials due to affinity for the hERG ion channel, when administered at high doses. [89] The inhibition of hERG leads to prolongations of the QT interval that predispose to life-threatening cardiac arrhythmias of the torsades de pointes type. [90]

3.5.4. Mechanism of action of ancriviroc

Ancriviroc was designed to be a noncompetitive allosteric antagonist of chemokine receptor CCR5. This receptor mediates viral entry into the host cell by binding to the CD4-Gp120 complex. Formation of CD4-Gp120 complex at the attachment of HIV leads to a conformation change, which exposes the binding site for CCR5. However, when CCR5 inhibitors (such as Ancriviroc) are present, the binding of CCR5 N-terminus and extracellular loops to Gp120 is blocked, which results in inhibition of the viron entry, [91] thus preventing HIV-1 replication.

3.5.5. Synthesis of ancriviroc

All structural congeners en route to the discovery of ancriviroc (75) were synthesized by a unified strategy developed by Palani and coworkers (Figure 20). The synthesis starts with protection of isonipecotic acid 83 as the trifluoroacetamide. The resulting acid was converted to acyl chloride 84 by treatment with thionyl chloride. The Friedel-Crafts reaction of acid chloride 84 with excess bromobenzene in the presence of AlCl3 afforded ketone 85. The ketone was protected as an ethylene acetal, and the trifluoroacetamide group was removed. The free secondary amine was allowed to react with N-Bocpiperidine-4-one in the presence of Ti(OiPr)4 and concomitant treatment of the resulting intermediate with diethylaluminum cyanide gave aminonitrile 87. The cyanide group was displaced by treatment with methylmagnesium bromide to give compound 88. Subsequent acetal cleavage under acidic conditions resulted in the concomitant Boc-deprotection. The Boc group was reinstalled to give ketone 89. Ketone 89 was converted to oxime 90, which was further transformed into ancriviroc by means of Boc-deprotection and a carbodiimide-mediated acylation.

Figure 20.

Synthesis of ancriviroc and its analogues. [87]

Reaction conditions and reagents: (a) TFAA (excess), reflux, 4 hr. (b) SOCl2 (excess), 12 hr. (c) AlCl3, bromobenzene (excess), reflux. (d) ethylene glycol, TsOH, toluene, reflux. (e) MeOH, H2O, K2CO3, r.t. 12 hr. (f) N-Boc-piperidine-4-one, Ti(OiPr)4, DCE, r.t. 12 hr, then Et2AlCN, r.t. 3 hr. (g) MeMgBr, THF, r.t., 2 hr. (h) 6M HCl, EtOAc, r.t. 12 hr. (i) Boc2O, 10% NaOH, Et2O, r.t., 12 h. (j) NH2OR, HCl, NaOAc, MeOH, r.t., 24 hr. (k) TFA, CH2Cl2, r.t., 2 h. (l) EDCl, DIEA, HOBt, CH2Cl2, r.t., 12 hr.

3.6. Tirapazamines: bioreductively-activated antitumor prodrugs

3.6.1. Introduction

Tirapazamine is an experimental anticancer prodrug that was developed as a hypoxic-selective cytotoxin for solid tumors. [92] This prodrug undergoes selective bioactivation catalyzed by multiple reductases at low oxygen tension (characteristic of solid tumor) to oxidizing radicals that react with DNA [22] leading to DNA damage via strand breakage and/or topoisomerase II poisoning. [23] Under oxygen-rich conditions, such as in normal cells, the free radical produced by tirapazamine is oxidized, reverting to the prodrug. Thus, this molecule is ideally suited for anticancer therapy, as it conveys excellent selectivity based on the intrinsic mechanism. Chemically, tirapazamine belongs to the class of benzotriazine di-N-oxides 92 (Figure 21).

Figure 21.

General structure of tirapazamines.

3.6.2. Discovery of tirapazamine

Tirapazamine was originally developed in a screening program directed towards the discovery of new herbicides. The first anticancer clinical use of tirapazamine was reported in 1986 by Zeman and coworkers. [93] However, the first synthesis of tirapazamine was reported by Robbins and Schofield as a derivative of 1, 2, 4-benzotriazines as early as in 1957. [94] The most important characteristic that distinguished tirapazamine was its relatively high hypoxic cytotoxicity ratio (HCR). HCR is defined as the ratio of drug concentration under aerobic and hypoxic conditions to yield approximately the same survival. Before the discovery of tirapazamine as hypoxic-selective anticancer agent is described, it is important to briefly discuss the physiology associated with hypoxia and survival of solid tumors.

Solid tumor cells transcribe a discrete set of genes in response to hypoxic stress under oxygen deprivation. [95] This hypoxic stress stimulates the tumor cell towards activation of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 HIF-1 (the main transcription factor regulating gene expression under hypoxia). The HIF-1 is a heterodimer, composed of α and β subunits. Under usual oxygen rich conditions, the alpha subunits have been shown to be hydroxylated at a conserved proline residue by enzymes known as HIF-prolyl-hydroxylases. This hydroxylation is a critical signal that leads to their ubiquitination [96] and, hence destruction by the proteasomal cascade. However, under oxygen-deprived conditions (hypoxia), such as in solid tumor, the activity of HIF prolyl-hydroxylases is inhibited, since oxygen is known to be a co-substrate of these enzymes. [97] This inhibition causes stabilization of the α subunit in HIF-1, which then translocates into the nuclear compartment and binds DNA as a heterodimer with the β subunit. The binding event occurs at the hypoxia-response element (HRE). This binding event triggers overexpression of genes necessary for tumor survival under such conditions. Some of these include glycolysis enzymes, which allow ATP-synthesis in an oxygen-independent manner, and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) that promotes angiogenesis leading to abnormal tumor vasculature. Therapeutic intervention employing radiation that is aimed at damaging the DNA has severe limitations, due to resistance of tumor especially at such low oxygen tension. This resistance under oxygen deprivation was first described by Gray and co-workers. [98] They showed that upon irradiation, the biological lesion react with oxygen. Oxygen, which has the highest electron affinity in the cell, reacts extremely rapidly with the free radical, thus making the damage permanent. In the absence of oxygen, (e.g. in a solid tumor) most of the free radicals produced on DNA and other biological targets can be reverted by proton transfer due to the participation of non-proteinogenic sulfhydryls in the cells (Figure 22). [99]

Figure 22.

Schematic representation of radiation-induced DNA damage in aerobic conditions and thiol-mediated DNA repair under hypoxic conditions.

The chemical restitution, or DNA repair pathway, which is characteristic of tumor, spurred efforts towards the development of alternative methods to produce free radicals under such hypoxic and reducing conditions. In 1986, Zerman and co-workers embarked on a search for small non-natural molecules, as well as natural products capable of producing free radicals selectively in a solid tumor under hypoxia. In this quest, mitomycin, misonidazole and tirapazamine were tested on a number of cancer cell lines. Their results showed that tirapazamine exhibited superior balance between hypoxic potency and selectivity for tumor cell compared to mitomycin and misonidazole. They investigated the use of tirapazamine in combination with radiotherapy, and their result in vivo experiments showed that non-toxic doses of tirapazamine enhanced radiation-induced tumor cell kill, when the drug was given between 1 hr before and 2 hr after the radiation dose. [93]

Tirapazamine entered clinical trials as a combination therapy with radiotherapy for the treatment of advanced head and neck cancer. [100] Although the drug did not complete phase III clinical trials due to poor extravascular penetration at the tumor site, it is a perfect therapeutical model that is used in the development of new selective-hypoxia agents. [101] Since then, several efforts to improve the activity and the pharmacological properties of tirapazamine have resulted in diverse analogues with some conservation of the benzotriazinyl backbone. For instance, Hay and coworkers studied influence of the ring substitution on the activity of tirapazamine. They established that ring substituents on tirapazamine analogues can be used to predictably modulate the single electron reduction potential of parent tirapazamine, – an important attribute that dictates the hypoxic-cytotoxic efficacies. In addition, they showed that greater selectivity could be achieved with substituents that are weakly electron-donating, such as halogens with single electron reduction potentials of E(1) values between −450 to −510 mV. However, in their studies, tirapazamine outperformed all new analogues in terms of the balance between hypoxic-cytotoxicity and solubility. [102] Continuous efforts in this field have been directed towards the development of more potent and selective analogues with improved penetrability in solid tumors. More recent structure activity relationship (SAR) studies carried out using a spatially resolved pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamics model, which employs tissue penetrability explicitly in lead optimization, revealed analogues with improved pharmacological properties. This method developed by Hicks and coworkers showed that two new lead compounds SN30000 (93) and SN29751 (94) have superior performance in hypoxic-selective cytotoxicity compared to parent tirapazamine (Figure 23). [103] For instance, metabolic studies of 93 and 94 in HT29 (colon cancer) cultures showed that each compound undergoes a hypoxia-dependent loss with a concomitant formation of their corresponding 1-oxides (95, 96, 97). With the exception of SN30000, a trace amount of the non-oxide 98 was formed. Formation of the 1-oxide metabolite confirms that these drugs operate via a similar mechanism to the parent tirapazamine. Comparatively, SN30000 showed highest rate constant for bioreductive consumption (Kmet 1.53 ± 0.21 min−1) followed by tirapazamine (1.3 ± 0.04 min−1) and the lowest for SN29751 (0.87±0.03 min−1). The reduced analogues of these parent N-oxides showed substantially reduced potencies and lower selectivity as hypoxic cytotoxins compared to the parent prodrugs. Further studies carried out with eight cell lines in order to test the scope of hypoxia-selective cytotoxicity of the compounds showed that SN30000 was more potent across all the cell lines than tirapazamine and SN 29751. The order of tumor penetrability calculated as a diffusion coefficient across HT29 multicellular layers was: SN30000 > SN 299751 > tirapazamine. Thus, the new analogue SN 30000 has superior hypoxic potency and selectivity. [103]

Figure 23.

Structures of tirapazamine analogues and their metabolites. [103]

Beatriz and coworkers [104] reported the synthesis and hypoxia-selective cytotoxicity of a series of 1,4-di-N-oxide derivatives of 99 and 100 (Figure 24). From their studies, a derivative 99-Cl with R1 = Cl, exhibited good cytotoxicity against the NCI 60 cell panel with a mean GI50 = 0.07 μM. Also, in an effort to improve the poor extravascular transport of tirapazamine, Hu and coworkers [105] reported the synthesis and evaluation of 3-aryl amino and 3-(alkoxymethylamino)benzotriazine-1,4-dioxide derivatives 101 and 102 by introducing lipophilic groups at the C-3 amino group of tirapazamine. Most of the analogues of this compound were more potent than tirapazamine in the tumor cell lines assay, and some of them exhibited greater hypoxia selectivity. In addition, SAR studies revealed that the introduction of an aromatic group at the C-3 amino 101 had a favorable effect on hypoxic cytotoxic activity, and a positive correlation between hypoxic activity and lipophilicity was demonstrated as well.

Figure 24.

Tirapazamine-based hypoxic-selective cytotoxins. [103]

Along these lines, Hu and coworkers also reported the synthesis and evaluation of a series of 3-phenyl-2-ethylthio-(or 2-ethylsulfonyl)-quinoxaline-1,4-dioxide derivatives by replacement of the 2-cyano group in 104 with ethylthio or ethylsulfonyl groups. The 2-ethylsulfonyl derivatives 106 displayed moderate to good antiproliferative activities under hypoxic conditions, while the corresponding 2-ethylthio derivatives showed almost no activity in a cell-based assay. These results support the observation that electron-withdrawing moieties are necessary for hypoxic activities, due to the modulation of one-electron reduction potentials of the molecules. Based on this finding, analogues of type 103, e.g. 3-(4-bromophenyl)-2-(ethylsulfonyl)-6-methylquinoxaline-1,4-dioxide, were synthesized that exhibited good antiproliferative activities in extensive cell lines in hypoxia, and also showed good inhibition of SMMC-7721 tumor growth in a dose-dependent manner using a human tumor xenograft mice model. [106] In order to further improve the potency and selectivity in hypoxia, Hu and coworkers reported a series of analogues of type 103 with a variation of the R1 and R2 substituents. Upon evaluation of these analogues across diverse cell lines, the most potent compound was identified with R1 = CH3 and R2 = Cl, i.e. 7-methyl-3-(3-chlorophenyl)-quinoxaline-2-carbonitrile 1,4-dioxide. This analogue displayed significant cytotoxic activity against BEL-7402, HepG2, HL-60, NCI-H460, HCT-116 and CHP126 cell lines in hypoxia with IC50 values ranging from 0.31 to 3.16 μM. [107]

Other strategies to improve the therapeutic efficacy of tirapazamine include ligation to endogeous ligand inhibitors whose receptors are native to tumor environment. [108] One worthy example is the chemical ligation of tirapazamine to indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) inhibitor. [109] IDO is an enzyme that catalyzes the metabolism of L-tryptophan through the kynurenine pathway. [110]

The depletion of L-tryptophan has been linked to halted growth of microbes as well as T-cells. Thus IDO is known as an immunomodulator. It has been demonstrated that tumor cells escape the immune system by engaging in the overexpression of IDO, which depletes L-Trp. Indeed, a wide range of human cancers such as prostatic, colorectal, pancreatic, cervical, gastric, ovarian, head, lung, are known to overexpress human IDO (hIDO). [111] The combination of hypoxic cytotoxin with IDO inhibitors has been postulated to be effective for hypoxic-neoplastic cells. An example of IDO-tirapazamine hybrid inhibitor is shown in figure 25.

Figure 25.

Tirapazamine analogue chemically-ligated to an indoleamine 2, 3-dioxygenase (IDO) inhibitor (IDO) and its mono-N-oxide derivative.

These hybrid inhibitors consist of three important modules: the hypoxia-selective cytotoxin unit, a linker, and an IDO inhibitor unit. It was demonstrated that hybrid inhibitors 107 and 108 were potent non-competitive IDO inhibitors. The tirapazamine-monoxide hybrid 108 was shown to be a stronger inhibitor than the di-N-oxide analogue 107. The hypoxia-selective cytotoxicity of both was compared to unmodified tirapazamine, and the results showed that compound 108 was indeed the most potent of them. However, compound 107 was still more potent than tirapazamine, confirming a cumulative effect originating from the presence of the IDO-inhibitor units.

There are also tirapazamine derivatives that contain attached DNA-targeting agents. These compounds were designed based on the hypothesis that tirapazamine toxicity occurs principally in the nuclear matrix of the cell [112] and that any metabolism or toxicity outside the nuclear compartment contribute to the unwanted side effects of the drug. [113] To test this hypothesis, tirapazamine was chemically linked to acridine and other agents known to target DNA (Figure 26). These compounds have been tested in comparison to tirapazamine. [114]

Figure 26.

Tirapazamine chemically-ligated to a DNA targeting unit.

The results demonstrated that attaching tirapazamine to acridine, e.g. as in compound 109, indeed led to increase in the potency by two orders of magnitude compared to unmodified tirapazamine depending on the cell investigated, while also retaining its selectivity towards hypoxic cells. The report also showed that tirapazamine undergoes bioreduction while bound to acridine chromophore on DNA.

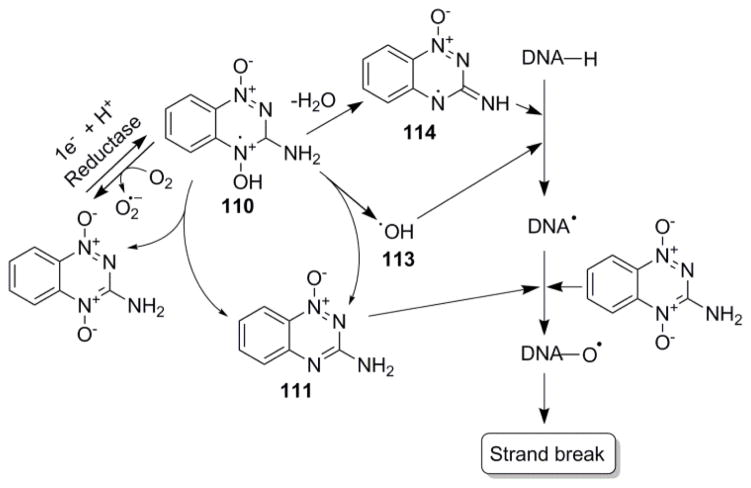

3.6.3. Unified mechanism of action of tirapazamine and related analogues

The unified mechanism of the hypoxic-selective cytotoxicity by tirapazamine and its analogues involves the metabolic action of multiple reductases to form a radical anion species. In the presence of oxygen (normal cells and tissues), this radical anion is back-oxidized to the parent compound. Under hypoxic conditions on the other hand, the radical abstracts a proton from DNA, thus inducing a single and double strand cleavage in a pathway, which is not completely understood. Studies show that under hypoxia, the protonated tirapazamine radical undergoes disproportionation forming a nontoxic two electron species 1,2,4-benzotriazin-3-amine 1-oxide, and also decays by a first order process forming a DNA damaging radical. The exact identity of the DNA damaging radical involved in this process has been a subject of debate. Some studies show evidence supporting decay of the protonated tirapazamine radical to a hydroxyl radical, [24] while others support the loss of water and concomitant formation of benzotriazinyl radical. [24]

Either way, the abstraction of a proton from DNA by the hydroxyl or benzotriazinyl radical produces DNA radicals, which then lead to strand breaks. [115] At the level of the strand cleavage, some studies have supported the second involvement of tirapazamine in the oxidation of DNA radical to form similar oxidized products as in oxygen-induced radiation cell death (Figure 27). [116] This finding is based on the demonstration of oxidized phosphoglycolate residues in DNA incubated under anoxic conditions with tirapazamine radical-generating system (i.e. a mixture of tirapazamine, xanthine and xanthine oxidase). [117] The finding has been supported by isotope-transfer and kinetic experiments, which shows the oxidation of photolytically generated DNA radical by tirapazamine under anaerobic conditions. [118] Thus, the radical-induced cleavage of DNA leads to major perturbations in the genes responsible for tumor survival under hypoxia and hence cell death. [119]

Figure 27.

Proposed bioreductive mechanism of action of tirapazamine resulting in DNA cleavage. [24a]

3.6.4. Synthesis of tirapazamines

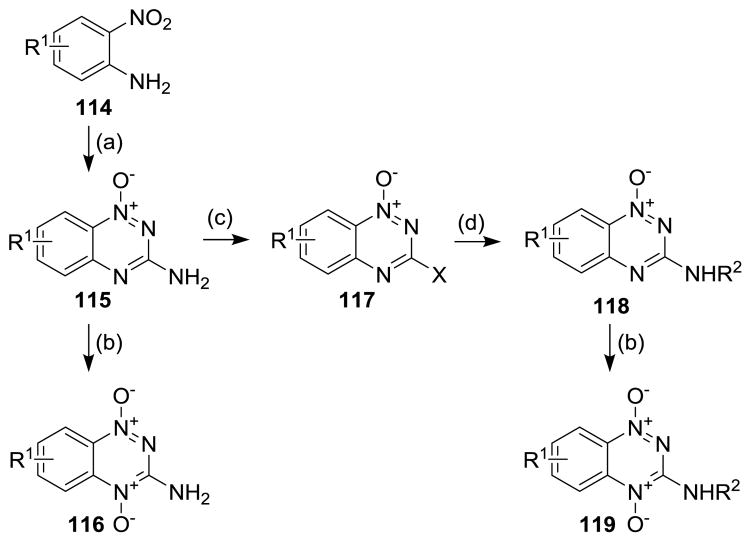

Tirapazamine and their analogues were prepared in two steps that involve a condensation of nitroaniline with cyanamide, followed by cyclization of the resulting guanidine with sodium hydroxide (Figure 28). The resulting 1-oxide was further oxidized to afford the di-N-oxide 116. The mono-N-oxide could be diazotized then chlorinated with POCl3. The resulting 2-chloro derivatives could be reacted with primary amines to afford 2-substituted tirapazamine derivatives 118. This method is widely used to build the benzotriazinyl backbone of all tirapazamine analogues. The benzotriazinyl core was also been prepared by reaction of o-nitroaniline with triphosgene (Figure 29). This reaction afforded an isocyanate which was then reacted with ammonia to afford urea derivative 121. The urea derivative was then cyclized using sodium hydroxide, providing a hydroxy group at the C-3 of the benzotriazine moiety of 122.

Figure 28.

Synthetic routes to tirapazamine analogues. [102]

Reaction conditions: (a) NH2CN, HCl, then 30% NaOH. (b) CF3CO3H, CF3CO2H, CH2Cl2. (c) i) NaNO2, CF3CO2H; ii) DMF, POCl3. (d) RNH2.

Figure 29.

Alternative synthetic routes to tirapazamine analogues. [102]

Reaction conditions: (a) triphosgene. (b) i) NH3; ii) NaOH, then AcOH. (c) i) POCl3; ii) R2NH2.

The chlorination of this compound with phosphorus oxychloride followed by reaction with various primary amines afforded a library of 1-oxide compounds with an amino group at C-3. Upon N-oxidation with peracid, this sequence furnished a family of tirapazamine derivatives.

The tricyclic analogues were prepared following the above protocol but starting with bicyclic o-nitroanilines 124 (Figure 30). To introduce non-heteroatom substituents at C-3, the corresponding 3-aminotriazine-1-oxide was diazotized in the presence of trifluoroacetic acid following by chlorination or iodination of the intermediate phenol. Iodination could be achieved by reaction of the corresponding diazonium with diiodomethane, while phosphorus oxychloride could be used to install the 3-chloro substituent.

Figure 30.

Synthetic routes to tricyclic tirapazamine analogues. [103]

Reaction conditions: (a) NH2CN, HCl, then 30% NaOH. (b) i) NaNO2, CF3CO2H; ii) DMF, POCl3 heat; (c) i) tBuNO2, CH2I2, CuI, THF, reflux; ii) allyl alcohol, Pd(OAc)2 (cat.), nBu4NBr, NaHCO3, DMF, heat; ii) morpholine, MeOH, then NaBH3CN, AcOH. (d) CF3CO2H, CF3CO3H, CH2Cl2.

The Heck reaction of these 3-halotriazines with allyl alcohol afforded an aldehyde which was subjected to reductive amination in the presence of morphine to give mono-N-oxide 127. The oxidation of 127 by trifluoroperacetic acid yielded the desired SN 30000 analogue 128. Other tirapazamine derivatives were also made using this protocol.

3.7. Aminopyridines and 1,7-naphthyridine N-oxides: emerging p38α mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) inhibitors

3.7.1. Introduction