Abstract

The potential of biased cyclical electrical field flow fractionation (BCyElFFF), which applies the positive cycle voltage longer than the negative cycle voltage, for characterization of submicron particles, was investigated. Parameters affecting separation and retention such as voltage, frequency, and duty cycle were examined. The results suggest that the separation mechanism in BCyElFFF in many cases is more related to the size of particles, as is the case with normal ElFFF, in the studied conditions, than the electrophoretic mobility, which is what the theory predicts for CyElFFF. However, better resolution was obtained when separating using BCyElFFF mode than when using normal CyElFFF. BCyElFFF was able to demonstrate simultaneous baseline separations of a mixture of 0.04, 0.1, and 0.2 μm particles and near separation of 0.5 μm particles. This study has shown the applicability of the BCyElFFF for separation and characterization of submicron particles greater than 0.1 μm in size, which had not been demonstrated previously. The separation and retention results suggest that for particles of this size, retention is based more on particle size than on electrophoretic mobility, which is contrary to existing theory for CyElFFF.

Keywords: Nanoparticles, colloids, electrical field flow fractionation, chromatography

Introduction

Particle size is a critical parameter affecting the material properties of many products. Particles in the nano and sub-micrometer scale are of interest in many research and industrial applications. Field-flow fractionation (FFF) can be used for separation of particles based on interactions with the applied field and the laminar flow profile in thin channels [1]. On the basis of the field applied in the system, FFF can be categorized into many subtechniques such as sedimentation FFF (SdFFF), flow FFF (FlFFF), thermal FFF (ThFFF), and electrical FFF (ElFFF) [2].

Electrical field-flow fractionation (ElFFF) was first described in 1972 [3]. The early ElFFF system was unreliable due to the use of membranes as channel boundaries. Then, ElFFF was essentially unattended for about two decades until new instrument designs were developed in 1993 by Caldwell’s group [4]. They used solid graphite blocks as channel walls that also acted as electrodes and that were separated by a Mylar spacer. This design eliminated some of the consistency problems, but introduced the polarization problem which shielded some of the applied voltage resulting in low electric fields in the channel. Typically, the actual electric field (referred to as the effective field) is less than 3% [5] of the applied electric field and is often less than 1% [4,6]. In order to overcome this problem, cyclical electrical field-flow fractionation (CyElFFF) was developed [7,8]. In CyElFFF, cyclical electrical fields are used instead of steady, direct-current fields. The cyclical fields can produce a much higher effective field when compared to normal ElFFF due to the delay in the electrical double layer (EDL) formation on the channel walls. Further, the use of cyclical electric fields causes particles to oscillate across some portion of the channel width, depending on the electrophoretic mobilities of the particles, which changes the separation mechanism somewhat and can be used to generate separations that should only depend on mobility. ElFFF and CyElFFF have been shown to work with several kinds of samples, such as: polystyrene particles [9,10,5], metal nanoparticles [8,11], natural nanoparticles [8], carbon nanotubes [8] and polymerized liposomes [12].

Separation and resolution in CyElFFF systems suffer from the diffusion of particles, especially when using nanometer scale particles that have large diffusion coefficients. Particles tend to drift away from wall and gradually move into the center of the channel during each voltage cycle resulting in peak broadening and poor resolution in the fractogram. Recently, Tasci et al. [13] suggested that using biased cyclical electric fields, which applies the positive cycle voltage longer than the negative cycle voltage, can help solve this diffusion problem. They were able to separate nanoparticles smaller than 50 nm. However, particles larger than 50 nm have not been studied. Herein, the potential of biased cyclical electrical field flow fractionation (BCyElFFF) for submicron particle characterization was investigated.

Theory

A typical CyElFFF system consists of solid graphite blocks acting as channel walls and also electrodes that are separated by a Mylar spacer. These electrodes are connected with an alternating current (AC) source, which applies the cyclical field as a square wave resulting in movement of particles back and forth within the channel. Higher electrophoretic mobility particles can move farther away from the walls into the higher velocity flow lines of the carrier leading to earlier particle elution when compared to lower electrophoretic mobility particles as shown in Fig. 1. Generally, for relatively high frequencies and low voltages in CyElFFF, the particles oscillate away from the accumulation wall of the channel which is defined as Mode I (particles do not reach the opposite electrode) [14,7,8].

Fig. 1.

CyElFFF system. The dashed lines show the particle trajectory resulting from the cyclical field

The retention of particles in CyElFFF can be described in term of a dimensionless parameter, λ0. When a square waveform is used to in CyElFFF, λ0 can be defined as

| (1) |

where μ is the electrophoretic mobility of the particle, f is the frequency, Eeff is the effective field in the bulk of the channel, and w is the thickness of the channel. The relationship between λ0 and retention ratio (R) can be express by

| (2) |

Therefore, separation in CyElFFF is theoretically based on the difference in the electrophoretic mobilities of the particles. However, the particle diffusion combines with the electrically driven motion of particles to determine the final elution time, and is especially relevant for small particles.

The diffusion of particles can affect separation and resolution, especially for groups of the particles that have similar electrophoretic mobilities. Example trajectories of negatively charged particles are shown in Fig. 2a. In general, the cyclical field is applied as a square wave form which has a positive voltage duration equal to that of the negative voltage (50% duty cycle), which causes the net electrical displacement (le = le−– le+) to be zero. If no other forces are present, particles should return to their same location away from the wall after each cycle. If the particles start at the wall, then they should return to the wall. However, particles are subject to diffusive forces that tend to drive particles in the +x direction (+ldx) during each cycle (away from the wall) and towards the high velocity locations of carrier, which has the effect of both reducing the retention time and separation resolution.

Fig. 2.

Schematic diagram showing particle trajectories as different dashed line for 4 different dc and le conditions. (a) dc = 50% (le < ldx). (b) dc ≅ dc* > 50%) (le ≅ ldx). (c) (dc < dc* > 50%) (le < ldx). (d) dc > dc* > 50%) (le > ldx). The red circle represents smaller particles with higher diffusion coefficients than the bigger blue particles. Both particles have similar negative electrophoretic mobilities. The black dashed lines represent the trajectories when diffusion is neglected

To overcome the diffusion of particles, bias voltages have been applied by increasing the duration of the positive voltage relative to the negative voltage, which increases the percent duty cycle (dc) to more than 50%. The notation dc* was used in previous publications to represent the %dc that was required to push the particles back to wall after every cycle (le = ldx) [13]. This case would ideally separate particles by only their charge or electrophoretic mobility and should give the best resolution as shown in Fig. 2b (dc ≅ dc* > 50%), by negating the impact of diffusion. Depending on the frequency and magnitude of the applied field, the required dc* for given conditions will change. [13]. When dc > dc*, particles will reach the wall before the cycle is complete and begin to operate as if they were under a normal, DC electric field (i.e. normal ElFFF). In this case shown in Fig. 2d (dc > dc* > 50%), particles will continuously move along with the channel in +z direction according to normal FFF theory. In these conditions, the channel exhibits separation characteristics that mix CyElFFF with the normal ElFFF mode in different ratios depending on the dc that is applied to the system. In the case where an extreme dc is applied, the cyclical fields may have limited effect and the channel behavior approaches that predicted for normal ElFFF, meaning that the separation mechanism is based on both particle size and charge rather than just charge. For particles that have similar electrophoretic mobilities, the separation mechanism can be considered as only depending on size.

The resolution of the separations was calculated using

| (3) |

where t1 and t2 are the positions of the peaks and σ1 and σ2 are the standard deviations of the peaks as they are approximated by a Gaussian curve [13].

Materials and methods

To verify that particles greater than 0.1 μm in size also behave as predicted in the theory section, a series of experiments were performed to understand the behavior and separation of particles when subject to BCyElFFF applied in a variety of conditions.

Chemicals

The experiments were carried out with nominally 0.1 and 0.2 μm polystyrene particles (Bangs Laboratories, Fishers, IN, USA) and nominally 0.04 and 0.5 μm polystyrene particles (Invitrogen, Oregon, USA) which were diluted to the concentration of 0.02 – 0.04 % solids in 2 mM NaN3. The particles’ size, zeta potential and electrophoretic mobility was measured using a Zetasizer (Möbius, Wyatt Technology Corporation, USA) and the results are shown in Table 1. Deionized water was used to prepare all chemical reagents and was used as carrier solution.

Table 1.

The size, zeta potential and electrophoretic mobility for particles used in this work

| Manufacturer Size of Polystyrene Particles (PS) | Measured Hydrodynamic Diameter (μm) | Measured Zeta Potential (mV) | Measured Electrophoretic Mobility (μm cm/s V) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PS#1 | 0.04 μm | 0.0421±0.0012 | −40.62±7.77 | −2.82±0.54 |

| PS#2 | 0.11 μm | 0.1166±0.0011 | −67.91±1.64 | −4.36±0.10 |

| PS#3 | 0.21 μm | 0.2076±0.0018 | −82.64±1.28 | −5.68±0.09 |

| PS#4 | 0.50 μm | 0.4760±0.0061 | −69.58±2.67 | −4.84±0.18 |

Instrumentation

The CyElFFF channel used for these experiments is identical to that used in previous works [4,7,13] and consists of parallel rectangular graphite plates separated by a Mylar spacer. The channel is 64 cm long, 2 cm wide, and 178 μm thick. An injection valve (Rheodyne® Model 9725i Injector) with a 20 μL injection loop was used for introduction of the suspended particles to the channel. The carrier solution was propelled by an HPLC pump (Beckman model 110B). The voltage sources were an Agilent DC power supply (Model E3640A) and Agilent signal generator (Model 33120A) for applying direct current (DC) fields and alternating current (AC) fields respectively. A UV detector (ESA Model 520) was set at 254 nm to monitor the eluted particles. The signals from the UV detector were collected using LabView 8.6 software (National Instruments).

Methods

For all experiments, a flow rate of 1 mL/min was used. Suspended particles were introduced through the injection loop. 0.1 μm and 0.2 μm particles in a mixture were used for all separation experiments. Some validation experiments were performed with single particle types. By calculation, particles took 10 s to reach the channel after injection. Therefore, after switching the valve to the injection position for 10 s, the flow of carrier was stopped by turning off the HPLC pump and time was set to zero (t = 0). The DC power supply was turned on (1 V DC) to relax and settle the particles to the wall along with the signal generator for 1 min. After this point, data from the detector was collected, the HPLC pump was started and the DC power supply was turned off. Once the retention or separation experiments were over and the detector signal had returned to baseline, the signal generator was turned off and the flow rate of the carrier changed to 2 mL/min to flush the particles that retained in the channel. The parameters used for experiments are given in Table 2.

Table 2.

Experimental parameters

| Experiment | Particle sizes (μm) | AC voltage (Vpp) | Frequency (Hz) | %duty cycle (%dc) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency effects | 0.1 and 0.2 | 1 | 10–70 | 60% |

| Duty cycle effects | 1 | 40 | 50–80% | |

| Individual particles for peak ID | 1 | 40 | 65% | |

| Individual particles for peak ID | 2 | 70 | 65% | |

| Voltage effects | 1–3 | 40 | 65% | |

| Frequency effects | 2 | 30–60 | 75–80% | |

| Frequency effects | 2 | 60–300 | 80% | |

| Individual particles for peak ID | 2 | 120 | 80% | |

| Frequency effects | 3 | 10–500 | 80% | |

| Frequency effects | 4 | 10–500 | 80% | |

| Individual particles for peak ID | 4 | 240 | 80% | |

| Separation demonstrations | 0.04, 0.1, 0.2 and 0.5 | 4 | 240 | 80% |

Results and discussion

In order to understand the effect of the applied voltage, frequency and the magnitude of the duty cycle (dc) on separations of 0.1 and 0.2 μm particles, we first studied the effect of frequency for low voltage and duty cycle. The results for the condition of 1 Vpp with a 60%dc and a frequency varying from 10 Hz to 70 Hz are shown in Fig. 3a. A relatively poor separation was obtained at 10 Hz, though retention of the particles was at least 10 min. As the frequency increased from 10 Hz to 20 Hz, separation and retention increased slightly (from 0.45 to 0.51), while an early elution peak started to grow. At frequencies higher than 20 Hz, this early elution peak began to dominate the analysis, leaving few particles to be retained and separated, so separation peaks became smaller and more difficult to detect.

Fig. 3.

Fractograms showing retention results for the given conditions. (a) mixture of 0.1 and 0.2 μm particles at varying frequency and a constant field of 1 Vpp at 60%dc. (b) mixture of 0.1 and 0.2 μm particles by varying the %dc and setting the condition of 1 Vpp at 40 Hz as constant. (c) the individual injections of the particles in the condition of 1 Vpp at 40 Hz and 65%dc. (d) the individual injections of the particles in the condition of 2 Vpp at 70 Hz and 65%dc

These first peaks with or near the void peak should be considered as early peaks [7], as defined by previous papers. These early peaks occur when there is no relaxation of the sample before or during the analysis. Essentially, some portion of the particles do not ever reach one of the walls, where they would synchronize with the other particles, and therefore spend most of their time in fast flow lines and elute with the void peak. Early peaks can occur when the voltage is too low or the frequency to high so that particles do not cross a significant portion of the channel height during one cycle when equilibration or bias is not used. A similar effect can occur when diffusion is relatively significant compared to the field such that the particles cannot be resynchronized at the wall (le < ldx) resulting in particles moving away from the wall by the +ldx in each cycle (model Fig. 2c) as occurs in the experiment presented in Fig. 3a, where the elution peak appears very close to the void peak for both 0.1 and 0.2 μm particles. These experimental conditions of 1 Vpp and 40 Hz were selected to further study the effect of duty cycle as shown in Fig. 3b. The results indicated that the early peaks decreased when the duty cycle increased. Fig. 3c shows the separation of mixed particles and the retention of individual particles at one of the best conditions in shown in Fig. 3b. Reasonable separation results could be obtained using these conditions, but it was clear that the smaller 0.1 μm particles were often co-eluting with the early peak as can be shown for slightly different conditions (2 Vpp, 70 Hz, 65%dc) as shown in Fig. 3d, which shows the individual and mixed fractograms. It is clear from Fig. 3d that the early peak is a co-elution of both 0.1 μm and 0.2 μm particles (though dominated by 0.1 μm particles) while a smaller, drawn out peak shortly after the early peak contained 0.1 μm particles and a clear, well resolved peak contained only 0.2 μm particles. In both the mixed particle and individual particle experiments, the first peaks were early peaks in all conditions.

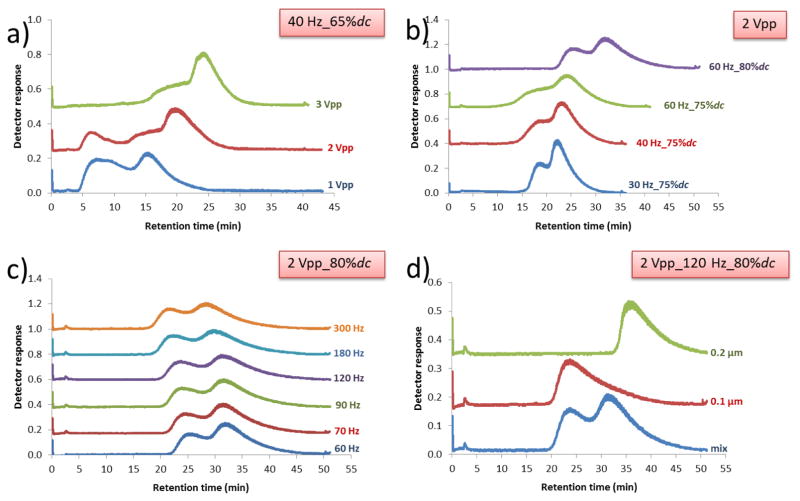

The effect of voltage was studied (Fig. 4a) when keeping the other parameters at a constant 40 Hz and 65%dc. As voltage increases with a constant duty cycle and frequency, the impact of diffusion is lessened by increasing le, which leads to a shrinking early peak and an increase in retention time. The early peak is completely eliminated for these conditions a 3 Vpp. The early peak can also be eliminated with a smaller voltage if a slightly higher duty cycle is used, as shown in Fig. 4b.

Fig. 4.

Fractograms showing the retention results for a variety of noted conditions. (a) Results for a mixture of 0.1 and 0.2 μm particles retained for a range of voltages at a constant 40 Hz at 65%dc. (b) Fractograms for a mixture of 0.1 and 0.2 μm particles with a constant 2 Vpp and varying frequency and %dc. (c) Fractograms for a mixture of 0.1 and 0.2 μm particles generated by varying the frequency and keeping the applied field at 2 Vpp and 80%dc. (d) Validation of the retention interpretation using individual injections of particles with conditions of 2 Vpp at 120 Hz and 80%dc

Based on these sets of experiments, it can be concluded that the early peaks can be avoided by both increasing either the voltage or the duty cycle, or by increasing them both in conjunction with one another. This more mild approach was selected for a series of experiments to determine further optimal separation conditions. Thus, the condition of 2 Vpp and a 75%dc was used for a further study (Fig. 4b) focused on frequency. In these conditions, although the early peaks disappeared, the separations were slowly degrading as broader separation peaks developed when increasing the frequency. These results indicate that diffusion still played a role at these higher frequencies as well. Interestingly, increasing the duty cycle at these higher frequencies still increased both resolution and retention.

While it is clear that increasing the duty cycle even further might have some benefits, at that point it would start to look mostly like “normal” electrical FFF, which is already well studied. Thus, we performed a series of experiments to determine the effect and range of frequency for which separations could be obtained. These experiments were all performed at 2 Vpp and 80% dc (Fig. 4c). The results showed that while the separation resolution (Table 3) improved slightly with substantial increases in frequency from 60 Hz to 120 Hz, a baseline separation was still not obtained at this relatively low voltage. At frequencies above more than 120 Hz, the separation resolution was slightly decreased. However, the early peaks did not return and the separation results were fairly consistent. Experiments with single particle sizes compared to mixed particles showed that retention orders for 0.1 μm and 0.2 μm particles had not changed and that both could be well retained individually (Fig. 4d). The individual peaks showed significant tailing, which lead to some of the loss of resolution in the separations when the tail drifted substantially into the 0.2 μm retention peak. In the mixed particle separations, the 200 nm peak has moved up to some earlier elution times, suggesting there may be some interaction effects in the separation, possibly related to changes in field strength with increasing numbers particles, though a similar effect does not occur for the 0.1 μm particles. Overall, it seems that frequency had minimal effect on separations and only a small inverse effect on retention times.

Table 3.

Retention ratio and resolution of the amplitude and frequency variation experiments at 80%dc

| Amplitude (Vpp) | Frequency (Hz) | Retention ratio | Resolution (Rs) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.1 μm | 0.2 μm | |||

| 2 | 60 | 0.103 | 0.082 | 0.60 |

| 70 | 0.106 | 0.083 | 0.60 | |

| 90 | 0.109 | 0.082 | 0.67 | |

| 120 | 0.110 | 0.083 | 0.67 | |

| 180 | 0.116 | 0.087 | 0.59 | |

| 300 | 0.121 | 0.092 | 0.56 | |

| 3 | 10 | 0.074 | 0.063 | 0.62 |

| 60 | 0.052 | 0.040 | 0.84 | |

| 120 | 0.054 | 0.038 | 0.92 | |

| 240 | 0.058 | 0.039 | 1.04 | |

| 500 | 0.063 | 0.043 | 0.90 | |

| 4 | 10 | 0.073 | 0.062 | 0.55 |

| 60 | 0.049 | 0.036 | 0.85 | |

| 120 | 0.052 | 0.036 | 0.98 | |

| 240 | 0.063 | 0.040 | 1.16 | |

| 500 | 0.084 | 0.056 | 0.87 | |

In continued efforts to obtain a better separation, we investigated the effect of increasing voltage to 3 and 4 Vpp and varying the frequency for an 80%dc (Fig. 5a, b). It should be noted that applying a voltage of 5 Vpp at 80%dc for any frequency generated significant bubbles in the channel, so the higher voltage options are somewhat limited due to electrolysis. The results with 3 Vpp (Fig. 5a) and 4 Vpp (Fig. 5b) suggest that increasing the voltage leads to better separations (Table 3), but only for frequencies greater than at least 10 Hz. To our knowledge, the use of higher frequencies (>100 Hz) presented here is the first reported to generate retention or separations in BCyElFFF, and these conditions generated relatively high retention and baseline separations. From all of these experiments, the condition of 4 Vpp, 240 Hz at 80%dc was the optimum (highest measured resolution, Table 3) condition for the separation of 0.1 and 0.2 μm particles. These results were confirmed by injection of single particle types as shown in Fig. 5c.

Fig. 5.

Fractograms showing the retention times for higher voltage conditions. (a) Fractograms for a mixture of 0.1 and 0.2 μm particles when varying the frequency and setting the field conditions of 3 Vpp at 80%dc constant (b) Fractograms for a mixture of 0.1 and 0.2 μm particles when varying the frequency and setting the conditions of 4 Vpp at 80%dc as constant. (c) Individual injections of 0.1 and 0.2 μm particles compared to a mixture for the conditions 4 Vpp at 240 Hz and 80%dc. (d) Individual injections of 0.04, 0.1, 0.2, and 0.5 μm particles compared to a mixture for 4 Vpp at 240 Hz and 80%dc

Careful analysis of all of the results so far show that the results do not readily match with standard CyElFFF theory. For these experiments with a bias voltage to counteract the diffusive transport in +x direction (+ldx) of the each cycle, the separation mechanism should be based on only the charge or electrophoretic mobility of the particles, according to standard CyElFFF theory. At the relatively high frequencies and low voltages used in this work, the particles should be in Mode I [7,8], and higher mobility particles should elute ahead of lower mobility particles. Accordingly, the 0.2 μm particles, which have a higher electrophoretic mobility (−5.68±0.09 μm cm/s V), should elute earlier than the 0.1 μm particles, which have a lower electrophoretic mobility (−4.36±0.10 μm cm/s V). However, the results show an inversion of the elution order suggesting that particle size must play an important role in the retention time. Thus, the retention theory will need to be revisited for CyElFFF to take into account size explicitly and to have a greater impact than charge or electrophoretic mobility. The results appear to be much more akin to normal ElFFF in their particle size separation capabilities and results. For these experiments, the results could be explained by the fact that the bias voltage was strongly applied producing an interval where “normal” ElFFF is active and an interval that has behavior like CyElFFF. The CyElFFF interval may be too small when compared with the interval that has behavior like normal ElFFF, which is heavily dependent on diffusion effects to generate separation effects. Thus, the effect of the electrophoretic mobility that has been shown to be operative in CyElFFF may be mostly negligible when voltages become large.

To better verify these results, experiments with a greater range of particles sizes were performed. For the optimal conditions found using earlier experiments (4 Vpp, 240 Hz at 80%dc), a baseline separation of a mixture of 0.04, 0.1, and 0.2 μm (Fig. 5d) particles was obtained with 0.5 μm particles showing the longest retention time, but not a complete separation from the 0.2 μm particles. It is possible (even likely) that the 0.5 μm particles exhibit steric effects leading to reduced retention. It should be noted that the electrophoretic mobility of the larger particles are relatively similar (within 25% of each other), but the smaller 0.04 μm particles have a mobility nearly half that of the others. In CyElFFF theory, these particles should elute later as they should stay close to the wall, but they again elute earliest. These results further confirm the previous results that size plays a major role in these separations and that these particles can be separated by size when they are of similar mobilities. Overall, size appears to outweigh the effects of mobility, at least for small particles with low mobilities.

As these results look a lot like those that might be obtained using ElFFF, the BCyElFFF separations with the 4 particle mixture were compared to separations obtained using normal ElFFF as shown in Fig. 6. The normal ElFFF condition of 1.9 V DC was used because electrolysis of water becomes significant and disruptive for voltages more than 1.9 V, based on our experience. Fig. 6 shows that normal ElFFF does not obtain a baseline separation between the 0.1 and 0.2 μm particles, nor does it separate the 0.5 μm particles from the 0.2 μm particles, which both eluted at the same time. Both methods showed a good separation of the smaller 0.04 μm and 0.1 μm particles. The failure to separate the 0.5 μm particles was likely due to the particles approaching or crossing the steric transition point [15,6] which is in the range of ~0.5 μm for these conditions. The BCyElFFF approach was able to baseline separate all of the particles except for the 0.2 μm and 0.5 μm particles, but it is clear that they are eluting as separate populations. The likely reason why BCyElFFF is slightly better than normal ElFFF is that the cyclical field disrupts the electrical double layer (EDL) formation on the channel walls on a regular basis and increases the effective field strength when compared with the normal ElFFF mode, which maintains a steady field. The CyElFFF approach also likely avoids some of the steric transition issues that would occur in normal ElFFF. Peaks in BCyElFFF are then retained longer (as verified in Fig. 6) and a better separation is produced. Nevertheless, the overall retention times and results are remarkably similar suggesting that the separations mechanisms are quite similar. The small improvements for BCyElFFF, though should be enough to suggest that this approach is better for many circumstances and separations involving long retention times and larger particles.

Fig. 6.

Fractograms showing the retention of 0.04, 0.1, 0.2 and 0.5 μm particles in BCyElFFF mode using 4 Vpp, 240 Hz, and 80%dc, and normal mode using 1.9 V DC

Conclusions

BCyElFFF was applied to the separation of particles at the submicron scale for the first time. Low applied voltages and high frequencies show the largest influence on the production of an early peak. Increasing duty cycle and applied voltage can improve the separation by reducing the early peak and prolonging the elution time. Higher duty cycles produced better separation results in these conditions. Higher frequency voltages than had been tested before using CyElFFF were required to get baseline separations of a mixture of 0.1 and 0.2 μm particles even with a high duty cycle. The separation mechanism was mostly found to be based on the size of particles, which makes the method similar to the results that can be obtained using normal ElFFF. Finally, it was shown that BCyElFFF can generate a better separation efficiency than that obtained for normal ElFFF for a mixture of particles spanning a large size range. Thus, BCyElFFF at high frequencies may be an approach worth considering when separating electrically charged particles ranging from <5nm to 0.5 μm.

Acknowledgments

Funding: We gratefully acknowledge research grants from the Thailand Research Fund (TRF) and Center for Innovation in Chemistry: Postgraduate Education and Research Program in Chemistry (PERCH-CIC), Commission on Higher Education, Ministry of Education, Thailand, and the Office of the Higher Education Commission and Mahidol University under the National Research Universities Initiative. Financial support was from the Huachiew Chalermprakiet University and Thailand Research Fund through the Royal Golden Jubilee Ph.D. Program (Grant No. PHD/0035/2554) to M.O. Support for B.K.G was provided in part by the National Institutes of Health under grant 1R21GM107894

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Giddings JC. A New Separation Concept Based on a Coupling of Concentration and Flow Nonuniformities. Separation Science. 1966;1(1):123–125. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schimpf ME, Caldwell KD, Giddings JC. Field-Flow Fractionation Handbook. John Wiley & Sons, Inc; New York: 2000. p. 8. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caldwell KD, Kesner LF, Myers MN, Giddings JC. Electrical field-flow fractionation of proteins. Science. 1972;176(4032):296–298. doi: 10.1126/science.176.4032.296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Caldwell KD, Gao YS. Electrical field-flow fractionation in particle separation. 1. Monodisperse standards. Anal Chem. 1993;65(13):1764–1772. doi: 10.1021/ac00061a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tri N, Caldwell K, Beckett R. Development of electrical field-flow fractionation. Anal Chem. 2000;72(8):1823–1829. doi: 10.1021/ac990822i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gale BK, Caldwell KD, Frazier AB. Geometric scaling effects in electrical field flow fractionation. 2. Experimental results. Anal Chem. 2002;74(5):1024–1030. doi: 10.1021/ac015623p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gale BK, Srinivas M. Cyclical electrical field flow fractionation. Electrophoresis. 2005;26(9):1623–1632. doi: 10.1002/elps.200410296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gigault J, Gale BK, Le Hecho I, Lespes G. Nanoparticle characterization by cyclical electrical field-flow fractionation. Anal Chem. 2011;83(17):6565–6572. doi: 10.1021/ac2008948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dunkel M, Tri N, Beckett R, Caldwell KD. Electrical field-flow fractionation: A tool for characterization of colloidal adsorption complexes. J Microcolumn. 1997 Sep;9(3):177–183. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gale BK, Caldwell KD, Frazier AB. A micromachined electrical field-flow fractionation (μ-EFFF) system. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 1998;45(12):1459–1469. doi: 10.1109/10.730439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Somchue W, Siripinyanond A, Gale BK. Electrical Field-Flow Fractionation for Metal Nanoparticle Characterization. Anal Chem. 2012;84(11):4993–4998. doi: 10.1021/ac300662b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sant HJ, Chakravarty S, Merugu S, Ferguson CG, Gale BK. Characterization of Polymerized Liposomes Using a Combination of dc and Cyclical Electrical Field-Flow Fractionation. Anal Chem. 2012;84(19):8323–8329. doi: 10.1021/ac301424b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tasci TO, Johnson WP, Fernandez DP, Manangon E, Gale BK. Biased Cyclical Electrical Field Flow Fractionation for Separation of Sub 50 nm Particles. Anal Chem. 2013;85(23):11225–11232. doi: 10.1021/ac401331z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee S, Myers MN, Beckett R, Giddings JC. Particle separation and characterization by sedimentation/cyclical-field field-flow fractionation. Anal Chem. 1988;60(11):1129–1135. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gale BK, Caldwell KD, Frazier AB. Geometric Scaling Effects in Electrical Field Flow Fractionation. 1. Theoretical Analysis. Anal Chem. 2001;73(10):2345–2352. doi: 10.1021/ac001463q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]