Abstract

Background

Transmitted drug resistance (TDR) remains an important concern when initiating antiretroviral therapy (ART). Here we describe the prevalence and phylogenetic relationships of TDR among ART-naïve, HIV-infected individuals in San Diego from 1996-2013.

Methods

Data were analyzed from 496 participants of the San Diego Primary Infection Cohort who underwent genotypic resistance testing before initiating therapy. Mutations associated with drug resistance were identified according to the WHO-2009 surveillance list. Network and phylogenetic analyses of the HIV-1 pol sequences were used to evaluate the relationships of TDR within the context of the entire cohort.

Results

The overall prevalence of TDR was 13.5% (67/496), with an increasing trend over the study period (p=0.005). TDR was predominantly toward non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs) [8.5% (42/496)], also increasing over the study period (p=0.005). In contrast, TDR to protease inhibitors and nucleos(t)ide reverse transcriptase inhibitors were 4.4% (22/496) and 3.8% (19/496) respectively, and did not vary with time. TDR prevalence did not differ by age, gender, race/ethnicity or risk factor. Using phylogenetic analysis, we identified 52 transmission clusters, including eight with at least two individuals sharing the same mutation, accounting for 23.8% (16/67) of the individuals with TDR.

Conclusions

Between 1996 and 2013, the prevalence of TDR significantly increased among recently infected ART-naïve individuals in San Diego. Around one-fourth of TDR occurred within clusters of recently infected individuals. These findings highlight the importance of baseline resistance testing to guide selection of ART and for public health monitoring.

Keywords: HIV-1, Infection, Transmission, Drug resistance, Antiretroviral therapy, San Diego

Introduction

The widespread use of combination antiretroviral therapy (ART) in the United States has resulted in a substantial reduction of HIV-related morbidity and mortality.[1] Mathematical models and clinical studies have also demonstrated that ART use reduces the risk of HIV transmission.[2-4] However, the emergence of HIV drug-resistant variants and their transmission remains a major concern to the widespread use of ART, which can lead to higher probability of early virological failure in first-line ART.[5-8]

Estimates of the rates of transmitted drug resistance (TDR) in HIV epidemic vary throughout the world. There are several reasons for this variation including differences in sampling, gender, race/ethnicity, location, time from seroconversion, duration of use of ART in the study population, and risk exposure category.[9-13] Overall, the prevalence of TDR has been reported to range from 3.4% to 25.2% among ART-naïve HIV-infected individuals in the United States [9][14-29], and has been associated with the level of drug resistance in the community as a whole, ‘community drug resistance’.[30]

Continued monitoring in the same population can provide important insights into important trends of TDR that may impact clinical practice, like which first line ART regimens should be used and if baseline drug resistance testing should be performed. Our group has monitored TDR in San Diego County since 1996 [16] and has documented TDR rates in both ART-naïve patients with an unknown duration of HIV infection [24] and those with recent infection.[16][31] Our most recent report was in 2009, which found the overall prevalence of TDR among newly diagnosed HIV-infected patients in San Diego County to be 19%.[31] The current study builds on this previous work by determining the prevalence, rate of change, and phylogenetic relationships of TDR in newly diagnosed and ART-naïve HIV-infected individuals in San Diego County from 1996 through 2013.

Methods

Study population

Individuals enrolled between June 1996 and June 2013 in the University of California, San Diego Primary Infection Resource Consortium (SDPIRC) were included in this analysis. Inclusion criteria were (1) age over 18 years, (2) HIV-infected within the previous 12 months, as determined by laboratory diagnostics, documented evolution of HIV seroconversion within the preceding 12 months or evidence of acute or early HIV infection as determined using a set of clinical, virologic and serologic criteria, and (3) no ART exposure at the time of enrollment (treatment-naïve), as previously described.[32] After informed consent, clinical demographic characteristics and laboratory data were obtained at baseline from all participants. This study was approved by the UCSD human research protection program.

Genotypic resistance analysis

Blood specimens were collected before the initiation of therapy and within 1 month of enrollment into SDPIRC for drug resistance evaluation. Population sequencing of the partial HIV-1 pol coding region was performed (GeneSeq HIV-1; Monogram Biosciences, Inc., South San Francisco, CA or Viroseq v.2.0; Celera Diagnostics, Alameda, CA).[33] Genotypic analysis was performed to detect mutations in the HIV-1 pol gene fragment encoding protease (PR) and reverse transcriptase (RT), as previously described.[32] Major drug resistance mutations (DRM) were identified using the Stanford HIV database Calibrated Population Resistance Tool version 6.0 available on http://cpr.stanford.edu/cpr/index.html [34] based on the 2009 World Health Organization surveillance of transmitted drug resistant mutations (SDRMs) list for nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs), non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs), and protease inhibitors (PIs).[35] The presence of one or more major resistance mutations in any drug class was considered as TDR according to the SDRM list.

Identification of transmission clusters by network analysis

Cluster analyses were performed as previously described.[36] Briefly, the Tamura-Nei93 nucleotide substitution model (TN93) [37] was used to compute genetic distance between all sequences, and a putative link was inferred if the TN93 genetic distance between two sequences was less than 1.5%. Elucidation of transmission clusters was performed by combining these inferred linkages.[31]

HIV-1 subtyping

The HIV-1 subtypes and circulating recombinant forms (CRF) were determined using two HIV-1 subtyping tools, namely the Rega HIV-1 subtyping tool version 3.0 [38, 39] and SCUEAL [40].The discordant subtyping results between the two tools were then analyzed using phylogenetic analysis in the Treemaker tool provided by HIV LANL Sequence Database that included all reference sequences from HIV-1 subtypes and CRFs to make an informed assignment of subtype.[41]

Phylogenetic Analysis

An alignment of the 496 available sequences was created using MUSCLE [42] and further curated manually using Bioedit software version 7.2.5.[43] To avoid the effect of homoplasy (convergent evolution) of drug resistance mutations on the phylogenetic analysis, all 29 codons associated with major DRM in PR and RT were removed from all of the sequences within the alignment. Phylogenetic approaches were then used to establish transmission clusters and interrelationships among viral sequences. Global phylogenetic relationships were estimated using a maximum likelihood (ML) approach with a bootstrap analyses with 1000 replicates using the general time reversible + Gamma (GTR + Γ) model of nucleotide substitution in FastTree version 2.1.[44] Robust clusters were assessed by bootstrap support values (≥70%) with 1000 replicates. The trees were edited and visualized using FigTree version 1.4.1.[45]

Statistical analysis

Prevalence values were calculated with a 95% Wilson score confidence interval (95% CI) for binomially distributed data. Categorical variables were compared using the χ2 test, Fisher's exact test, or simple logistic regression analysis as appropriate. Continuous variables were compared using the Student's t-test or the Mann–Whitney U test. Multiple binomial logistic regression analysis was used to determine the factors associated with drug resistance mutations and control the potential confounders. The yearly time periods were assessed with χ2 test for trend or the Cochran-Armitage test. All P-values were two-tailed tests and the statistical significance level set at P< 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Characteristics of subjects

A total of 496 SDPIRC participants with clinical or laboratory evidence of primary HIV infection were enrolled from 1996 through 2013. The majority of the study population was male (97%); 78% were white, 9.7% Native American, 6.8% black, 3.7% Asian, and 1.9% Pacific Islander (Table 1). The mean age of SDPIRC participants was 32 years at the time of resistance testing. The most commonly reported transmission risk factors were men who have sex with men (MSM, 90.3%) or MSM and intravenous drug use (MSM+IVDU; 3.2%), followed by heterosexual contact (2.4%). These data are consistent with the HIV epidemiology in San Diego County.[46] At enrollment, mean baseline CD4 count was 530 cell/μLand 3.4% having CD4 < 200 cell/μL. Median viral load at enrollment was 97, 808 HIV RNA copies/mL. Overall, most participants were infected with HIV-1 subtype B (97.4%). No any single HIV-1 non-B subtype represented more than 0.4% of the sample.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of newly HIV-infected individuals.

| Characteristic | Number of individuals, n (%) |

|---|---|

| All patients | 496 (100) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 478 (96.96) |

| Female | 15 (3.04) |

| Unknown | 3 |

| Age at diagnosis (Years) | |

| 20-29 | 169 (39.67) |

| 30-39 | 141 (33.1) |

| 40-49 | 87 (20.42) |

| ≥50 | 29 (6.81) |

| Else (Missing data & < 20) | 70 |

| Mean, years (±SD) | 32.49 (±11.13) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Non-Hispanic or Latino/ | 230 (63.36) |

| Hispanic or Latino/ | 131 (36.09) |

| Other | 2 (0.55) |

| Unknown | 133 |

| Race | |

| White/Caucasian | 379 (77.99) |

| Native American | 47 (9.67) |

| Black/African American | 33 (6.79) |

| Asian | 18 (3.7) |

| Pacific Islander | 9 (1.85) |

| Unknown | 10 |

| HIV risk exposure | |

| MSM/MSM-IDU | 464 (94.69) |

| Heterosexual | 12 (2.45) |

| Bisexual/Bisexual-IDU | 14 (2.86) |

| Unknown | 6 |

| CD4 cell count (cell/mm3) | |

| < 200 | 17 (3.43) |

| 200 to < 350 | 88 (17.74) |

| 350 to < 500 | 136 (27.42) |

| ≥ 500 | 255 (51.41) |

| Mean absolute CD4 (±SD) | 530 (±222.69) |

| Mean percent CD4 (±SD) | 28.44 (±23.42) |

| Viral load | |

| Median Viral load (copies/mL) | 97808 |

| Mean Viral load (log10copies/mL) (±SD) | 4.97 (±1.11) |

| Missing | 1 |

| Baseline alcohol 3 months before enrollment | |

| Yes | 118 (80.27) |

| No | 29 (19.73) |

| Missing | 349 |

| Baseline methamphetamine injection 3 months before enrollment | |

| Yes | 6 (5.77) |

| No | 98 (94.23) |

| Missing | 392 |

Overall prevalence of transmitted drug resistance (TDR)

The percentage of ART-naïve individuals with primary HIV infection enrolled in SDPIRC between 1996 and 2013 who harbored one or more DRM was 13.5% [67/496; 95% confidence interval (CI): 10.8-16.8%]. The most common major DRM identified were associated with NNRTIs resistance at 8.5% [42/496; 95% CI: 6.3-11.3%], followed by PIs at 4.4% [22/496; 95% CI: 2.9-6.7%] and NRTIs at 3.8% [19/496; 95% CI: 2.4-5.9%] (Table 3). Dual- and triple-class TDR were found in 3.8% [19/496; 95% CI: 2.4-5.9] and 1.0% (5/496; 95% CI: 0.4-2.4%) of subjects. The K103N/S, NNRTIs-associated mutation, was the most frequent mutation observed in 7.3% of individuals, while most NRTIs DRM were thymidine analogue mutations (TAM) of which the most prevalent were the T215Y/F/I/S/D/E/C/V mutations (2%), followed by M41L (1.8%), whereas M46I/L was the most common PI DRM, which was found in 1.8% of individuals (Supplementary material).

Table 3. Trends of HIV-1 transmitted drug resistance throughout the study period.

| TDR Category | Total | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | P* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=496 | n=6 | n=15 | n=8 | n=11 | n=19 | n=36 | n=45 | n=48 | n=52 | n=53 | n=23 | n=14 | n=25 | n=37 | n=34 | n=27 | n=37 | n=6 | ||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| Any, n (%) | 67 (13.5) | 0 (0) | 1 (6.7) | 1 (12.5) | 3 (27.3) | 2 (10.5) | 4 (11.1) | 7 (15.6) | 1 (2.1) | 1 (1.9) | 13 (24.5) | 4 (17.4) | 4 (28.6) | 3 (12.0) | 8 (21.6) | 4 (11.8) | 4 (14.8) | 6 (16.2) | 1 (16.7) | 0.16 |

| PI, n (%) | 22 (4.4) | 0 (0) | 1 (6.7) | 1 (12.5) | 2 (18.2) | 0 (0) | 3 (8.3) | 3 (6.7) | 1 (2.1) | 1 (1.9) | 5 (9.4) | 1 (4.3) | 0 (0) | 1 (4.0) | 1 (2.7) | 0 (0) | 1 (3.7) | 1 (2.7) | 0 (0) | 0.09 |

| NRTI, n (%) | 19 (3.8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (9.1) | 0 (0) | 2 (5.6) | 5 (11.1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 (7.5) | 1 (4.3) | 2 (14.3) | 1 (4.0) | 1 (2.7) | 0 (0) | 1 (3.7) | 1 (2.7) | 0 (0) | 0.68 |

| NNRTI, n (%) | 42 (8.5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (10.5) | 3 (8.3) | 4 (8.9) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 7 (13.0) | 3 (13.0) | 2 (14.3) | 1 (4.0) | 6 (16.2) | 4 (11.8) | 3 (11.1) | 6 (16.2) | 1 (16.7) | 0.005 |

| NRTI + NNRTI, n (%) | 6 (1.2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (5.6) | 2 (4.4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.9) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.7) | 0 (0) | 0.43 |

| NRTI + PI, n (%) | 7 (1.4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (5.6) | 3 (6.7) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (3.8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.1 |

| NNRTI + PI, n (%) | 6 (1.2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (5.6) | 2 (4.4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.9) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.7) | 0 (0) | 0.43 |

| Triple-class, n (%) | 5 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (5.6) | 2 (4.4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.9) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.11 |

χ2 test for linear trend, unadjusted

PI, protease inhibitors; NRTI, nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors; NNRTI, non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor

TDR trends throughout the study period

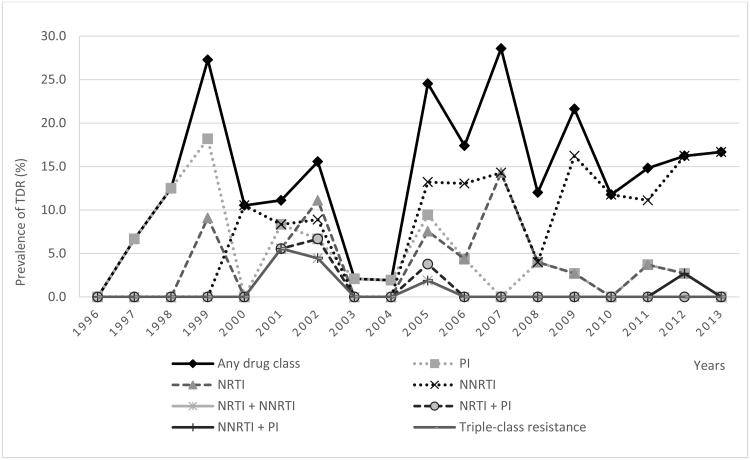

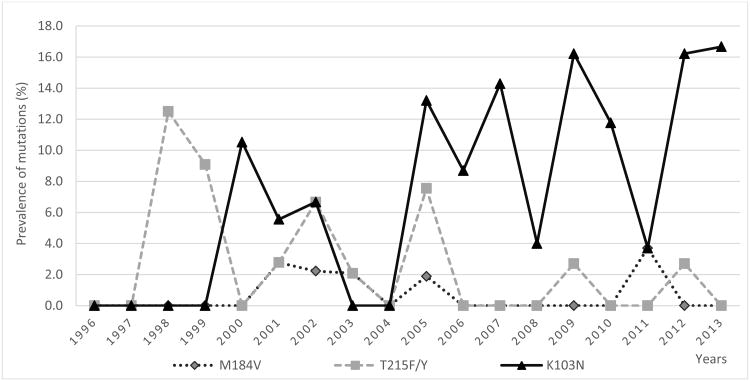

When the rates of TDR were compared among four time periods (1996-1999, 2000-2004, 2005-2009 and 2010-2013), we found a statistically significant increase over time in the proportion of participants with TDR (p = 0.005; Table 2), and this significance remains when controlling for potential confounders (p = 0.02). When comparing resistance by ART class (Table 3 and Figure 1), TDR prevalence for NNRTIs significantly increased over the entire study period (p for trend = 0.005) that coincided with the observed increase in K103N/S mutation (p for trend = 0.005; Figure 2 and Supplementary material). In contrast, the prevalence of NRTIs and PIs TDR were apparently stable over time (p = NS). The temporal trends for specific mutations are presented in Supplementary material.

Table 2. Characteristics of newly HIV-1-infected patients with and without transmitted drug resistance mutations.

| Total | TDR | Wild type | Univariate | Multivariate | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | (95%CI) | P-value | OR | (95%CI) | P-value | ||||

| Patients | 496 | 67 (13.5) | 429 (86.5) | ||||||

| Sex | 0.97 | 0.08 | |||||||

| Male | 478 | 65 (13.6) | 413 (86.4) | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | ||

| Female | 15 | 2 (13.3) | 13 (86.7) | 0.98 | 0.22-4.43 | 6.62 | 0.76-57.8 | ||

| Unknown | 3 | c | c | ||||||

| Age | 0.6 | 0.46 | |||||||

| 20-29 | 169 | 23 (13.6) | 146 (86.4) | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | ||

| 30-39 | 141 | 16 (11.3) | 125 (88.7) | 0.81 | 0.41-1.61 | 1.15 | 0.5-2.66 | ||

| 40-49 | 87 | 15 (17.2) | 72 (82.8) | 1.32 | 0.65-2.69 | 1.89 | 0.79-4.56 | ||

| ≥ 50 | 29 | 5 (17.2) | 24 (82.8) | 1.32 | 0.46-3.81 | 1.9 | 0.56-6.5 | ||

| Unknown & ≤ 20 | 70 | c | c | ||||||

| Mean years (±SD) | 32.5 (±11.13) | 32.6 (±13.2) | 32.5 (±10.8) | 0.94a | |||||

| Ethnicity | 0.75 | 0.58 | |||||||

| Non-Hispanic or Latino/A | 230 | 34 (14.8) | 196 (85.2) | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | ||

| Hispanic or Latino/A | 131 | 21 (16) | 110 (84) | 1.1 | 0.61-1.99 | 1.23 | 0.6-2.53 | ||

| Other | 2 | 0 (0) | 2 (100) | 1 | - | 1 | - | ||

| Unknown | 133 | c | c | ||||||

| HIV risk exposure | 0.66 | 0.58 | |||||||

| MSM/MSM-IDU | 464 | 62 (13.4) | 402 (86.6) | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | ||

| Heterosexual | 12 | 2 (16.7) | 10 (83.3) | 1.30 | 0.28-6.06 | 2.45 | 0.2-30.36 | ||

| Bisexual/Bisexual-IDU | 14 | 3 (21.4) | 11 (78.6) | 1.77 | 0.48-6.52 | 1.81 | 0.42-7.8 | ||

| Unknown | 6 | c | c | ||||||

| CD4 cell count at enrollment (cells/mm3) | 0.23 | 0.55 | |||||||

| <200 | 17 | 2 (11.8) | 15 (88.2) | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | ||

| 200 to < 350 | 88 | 14 (15.9) | 74 (84.1) | 1.42 | 0.29-6.90 | 5.15 | 0.52-51.06 | ||

| 350 to <500 | 136 | 24 (17.6) | 112(82.4) | 1.61 | 0.34-7.50 | 5.79 | 0.52-64.89 | ||

| ≥ 500 | 255 | 27 (10.6) | 228 (89.4) | 0.89 | 0.19-4.10 | 5.7 | 0.36-89.42 | ||

| Mean absolute CD4 (±SD) | 530 (±222.7) | 479 (±172.3) | 537 (±228.7) | 0.02a | 0.33 | ||||

| Mean percent CD4 (±SD) | 28.44 (±23.4) | 26.86 (±9.5) | 28.69 (±24.8) | 0.28a | 0.85 | ||||

| Viral load | |||||||||

| Median VL (copies/ml) | 97808 | 170000 | 90050 | 0.23b | |||||

| Mean log10 viral load (±SD) | 4.97 (±1.1) | 5.23 (±1.1) | 4.96 (±1.1) | 0.24a | 0.24 | ||||

| Year of Diagnosis | 0.005 | 0.02 | |||||||

| 1996-1999 | 40 | 5 (12.5) | 35 (87.5) | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | ||

| 2000-2004 | 200 | 15 (7.5) | 185 (92.5) | 0.57 | 0.19-1.66 | 0.07 | 0.01-0.71 | ||

| 2005-2009 | 152 | 32 (21.1) | 120 (78.9) | 1.87 | 0.68-5.15 | 0.23 | 0.03-2.09 | ||

| 2010-2013 | 104 | 15 (14.4) | 89 (85.6) | 1.18 | 0.40-3.49 | 0.14 | 0.01-1.29 | ||

Data are presented as number (%) of patients, unless otherwise indicated.

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; TDR, transmitted drug resistance; SD, standard deviation; Latino/A, Latino Americans; MSM, men who have sex with men; IDU, intravenous drug user; VL, viral load.

ORs were estimated using simple (unadjusted) and multiple (adjusted) logistic regression.

=Two-sample t test

=Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test.

=Persons with every unknown category were excluded from logistic regression models.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of transmitted drug resistance mutations by drug class among treatment-naïve, recently HIV-infected individuals over time.

PI, protease inhibitors; NRTI, nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors; NNRTI, non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors; TDR, transmitted drug resistance; Any, TDR to any drug class.

Figure 2. Prevalence of common specific resistance mutations in treatment-naïve, recently HIV-infected individuals over time.

Correlates of TDR

Characteristics of individuals with and without TDR were comparable for sex, age at enrollment, ethnicity, route of transmission, CD4 cell count, plasma HIV-RNA, baseline history of alcohol use and IVDU within 90 days of SDPIRC enrollment, and year of diagnosis (Table 2). In a univariate analysis, mean baseline CD4 cell count was significantly lower among individuals with TDR (p = 0.02; Table2), but no difference was found in baseline median plasma viral load (p = 0.23; Table 2). Similarly, no significant association between TDR and other demographic factors, sexual practices, or use of recreational drugs were found. Given that only one factor was associated with TDR (baseline CD4 count), no significant associations became evident in multivariate analyses.

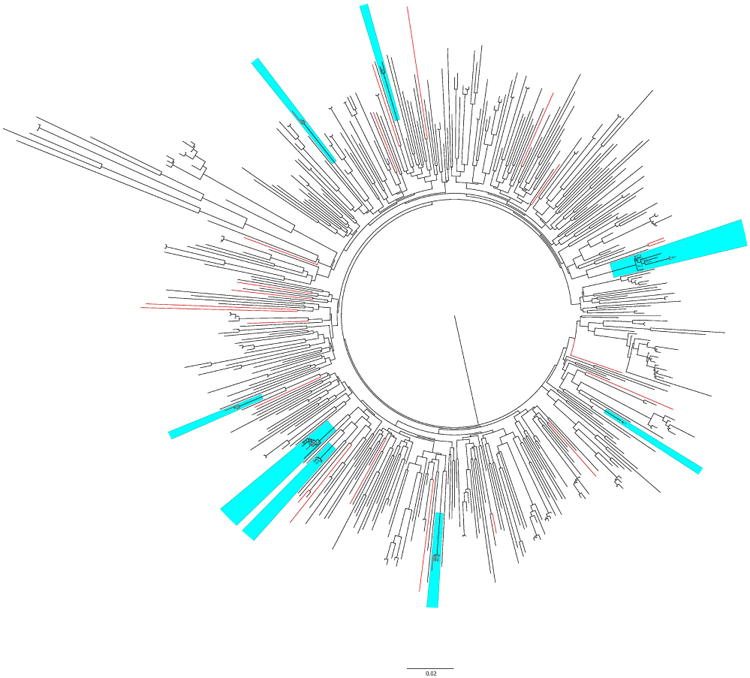

Phylogenetic and network analysis

A phylogenetic tree was inferred with the 496 HIV-1 partial pol sequences from the SD PIRC dataset (Figure 3). Given the limitations associated with phylogenetically analyzing such large numbers of sequences, we also utilized network analysis to obtain a deeper understanding of the underlying transmission network. We identified 52 transmission clusters (169 individuals, 34% of the cohort), of which 12 included at least one individual with a DRM. Of these clusters, eight (66.6%) included at least two individuals carrying the same resistance mutation, and the K103N was the concordant mutation found in seven out of these eight clusters, whereas in the remaining one cluster, L90M was the concordant mutation. Phylogenetic analysis using FastTree software was used to confirm the existence of these eight clusters, and all these clusters had bootstrap values ≥ 70% (Figure 3), supporting the findings made using the network analysis.

Figure 3.

The maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree of all HIV-1 pol sequences using GTR + Gamma nucleotide substitution model in FastTree package. Total available 496 sequences were used to reconstruct the phylogeny. Twenty-nine codons associated with resistance mutations were remove from the alignment. Bootstrap with 1000 replicated was applied to evaluate the reliability of the reconstructed tree. Bootstrap support values of ≥70% are shown at nodes on the tree. Red branches represent sequences with K103N mutation and blue box indicates identified clusters which contain at least two individuals sharing the same resistance mutation.

Focusing on the individuals with primary infection, the prevalence of TDR was not significantly different among individuals who were part of clusters and those who were not [11.8% (20/169) vs. 16.8% (47/280), respectively; p = 0.49]. In order to further determine the probability of having the same DRM in the same identified cluster by chance, prevalence of TDR was also compared among all individuals of each transmission cluster, which contained at least two individuals sharing the same DRM. Significant over-representation of individuals sharing the same DRM was found in 6 of 8 clusters at two different nominal p-values of 0.005 and 0.02 (data not shown). We also found strong evidence that individuals with DRM that were in a phylogenetic cluster were more likely to have a closest neighbor in the phylogenetic tree of all SD PIRC sequences with the same DRM than individuals with sequences harboring DRM who were not found within a cluster (p = 0.002, data not shown).

Discussion

This study estimated the prevalence of TDR among individuals with acute and early HIV infection in San Diego between 1996 and 2013. The combined prevalence of TDR to one or more drugs in the first three ART classes was approximately 13.5% over the 18 years of the study. Given the episodic nature of HIV transmission, we expected to observe year-to-year variation in TDR rates, similar to what has been shown in other recent studies [47-49]; however we did observe a significant increase in the overall rate of TDR over time. The TDR rates found from 2005-2013 mirror the most recent CDC study evaluating TDR nationally between 2007 and 2010, which reported a 16.2% rate of TDR among ART-naïve HIV-infected individuals across the United States.[29] In contrast, studies in Europe have reported stabilizing and possibly decreasing trends in TDR prevalence in recent years.[50] Similar to the CDC report, we found that the overall prevalence of TDR to NNRTIs was 8.5% in our cohort, while the CDC report by Kim et al. found the prevalence of TDR to NNRTIs to be 8.1%. Our study found that dual-class resistance and triple-class resistance was slightly higher at 3.8% and 1.0% respectively, compared to the CDC report of 2.1% and 0.5% respectively. These differences may be secondary to differences in study design where we only evaluated for TDR among individuals with recent HIV infection, while the CDC study examined individuals who were ART-naïve but the duration of infection was not always known. As such, the rates of TDR from the CDC study maybe underestimations, since TDR mutations can become undetectable over time from reversion to wild-type sequences.[51]

In our study, TDR to NNRTIs was the most frequently observed DRM, consistent with other published studies.[11] [17] In the pre-combination ART era (before 1996), TDR in the US was primarily directed to NRTIs; however, when NNRTIs became widely available in 1996 [52-56], the prevalence of recently HIV-infected individuals who had TDR to NNRTI increased over time, with the K103N the most frequently observed DRM. Specifically, 53.7% of individuals with DRM had the K103N mutation. This may be because the K103N DRM is often associated with early virologic failure with the most frequently used NNRTI efavirenz [57], has minimal effects on viral replication capacity [58] and may persist for long periods, even after discontinuation NNRTI-based therapy. [59, 60] Generally, early virologic failure to efavirenz is conferred by a single mutation, but continuation of ART during virologic failure often leads to accumulation of multiple DRM, which can lead to cross class resistance.[61]

In this study most DRM to NRTIs were TAMs T215Y/F/I/S/D/E/C/V (2%) and M41L (1.8%), which mostly confer resistance to older generation NRTIs, zidovudine and stavudine. However, the M41L alone can be a polymorphism that is not associated with reduced susceptibility to any NRTIs by itself.[62, 63] The rate of this TDR to NRTI with TAMs remained relatively stable throughout our observed study period. Since zidovudine and stavudine are rarely prescribed anymore, the persistence of these TAMs in our ART-naïve cohort suggests that these TAMs and their revertants are evidence of ongoing TDR that carries DRM that were selected for in patients receiving zidovudine or stavudine earlier in the epidemic. This hypothesis is supported by several studies that have demonstrated that TAMs and their revertants persist for several years with little reversion to wild type amino acids in the absence of antiretroviral selection pressure.[51] [64]

The prevalence of TDR to PIs was lower than TDR to NNRTIs and NRTIs, which is consistent with other studies [64-66], and is likely the result of the high genetic barrier to develop DRM to PIs.[67, 68] According to recent version guidelines for treating HIV infection [69, 70], integrase strand transfer inhibitors (INSTIs) were listed as a “preferred” regimen for ART-naïve HIV-infected individuals. Although to date the prevalence of TDR to INSTIs has been very rare [71-73], increased use will certainly lead to increasing TDR to INSTIs. Thus, monitoring of TDR should include evaluation for integrase mutations.

In most studies, individuals with TDR appeared to have higher baseline CD4 cell count than individuals without TDR [11][74, 75]; however, our study found the opposite. This discrepancy was found in at least one other study [76], and may be due to differences between cohorts. However, this association turned to non-significant in multivariate analysis. The most recent CDC report of TDR among ART-naïve MSM in a large US study showed higher prevalence of TDR among MSM (17.4%) compared to heterosexuals.[77] In comparison, we found the prevalence of TDR among MSM to be lower at 13.4% as compared to 16.7% in the heterosexual population (p = 0.67, data not shown). Unfortunately, the small number of participants reporting heterosexual risk prevents us from generalizing our results to that population. These variations may reflect differences in the MSM population size, linkage or access to diagnosis and care. Since new infection among MSM still remain important factor driving HIV epidemic, especially in San Diego, TDR surveillance in this group should be regularly performed to identify and intervene on developing TDR trends.

This study had a rate of clustering with 34.1% of sequences segregating into 52 clusters. Several of these transmission clusters included individuals sharing the same DRM, in particular K103N mutation. This presence of TDR within transmission clusters accounted for almost 30% of DRM in the cohort, which may be explained by reduced time for viral reversion of DRM during clustered transmission.[78] Several remaining clusters included individuals with different resistance mutations, which may reflect reversions, or sampling bias.

As with any other observational study, our study has limitations. First, we may have had a biased sample of the local population since potential participants were not selected using random sampling methods, and thus our study population might not be representative of our overall local population. Second, although the predominant risk factor in the San Diego epidemic is MSM, the SDPIRC is even more highly focused on this population with targeted HIV testing campaigns [79], and thus MSM were most likely over-represented. Third, this study did not evaluate TDR to other classes of antiretroviral medications, like integrase inhibitors and fusion inhibitors. As the use of these agents increases, surveillance for TDR to the agents must be included. Finally, our data were not complete, and so demographic and clustering associations with TDR may have been missed.

Conclusion

Transmission of primary HIV-1 drug resistance continues to be an important public health threat. This study indicates that the prevalence of TDR has significantly increased over the past 18 years, specifically for TDR to NNRTIs. This study has also identified that TDR can occur within transmission clusters, which may be why the rate of TDR does not seem to be slowing despite the use of more effective ART over time. Taken together, this study reinforces the current recommendations for both baseline resistance testing to guide treatment decisions [68] and the early treatment recently diagnosed individuals [80], since early HIV detection and treatment can prevent transmission of HIV drug resistance.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the UCSD Center For AIDS Research (CFAR) and all patients who participated in the San Diego Primary Infection Cohort, to Josué Pérez Santiago and Mayuree Homsanit for invaluable statistical advice, and to Demetrius Dela Cruz for his administrative assistance.

Source of Funding: This work was supported by Department of Veterans Affairs and grants from the National Institutes of Health: AI100665, MH097520, DA034978, AI036214, AI007384, AI047745, AI106039, AI093163, AI108351, MH100974, K01AI110181; the James B. Pendleton Charitable Trust.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: There are no conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions: Conceive and designed experiments: D.M.S., S.J.L.

Analyzed and interpreted data: T.P., S.R.M., J.O.W.

Drafted manuscript: T.P.

Revised manuscript: S.R.M., D.M.S., D.D.R., S.J.L., J.O.W.

References

- 1.Palella FJ, Jr, Delaney KM, Moorman AC, Loveless MO, Fuhrer J, Satten GA, et al. Declining morbidity and mortality among patients with advanced human immunodeficiency virus infection. HIV Outpatient Study Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:853–860. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199803263381301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Quinn TC, Wawer MJ, Sewankambo N, Serwadda D, Li C, Wabwire-Mangen F, et al. Viral load and heterosexual transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Rakai Project Study Group. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:921–929. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200003303421303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Attia S, Egger M, Muller M, Zwahlen M, Low N. Sexual transmission of HIV according to viral load and antiretroviral therapy: systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS. 2009;23:1397–1404. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832b7dca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Das M, Chu PL, Santos GM, Scheer S, Vittinghoff E, McFarland W, et al. Decreases in community viral load are accompanied by reductions in new HIV infections in San Francisco. PLoS One. 2010;5:e11068. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Little SJ, Daar ES, D'Aquila RT, Keiser PH, Connick E, Whitcomb JM, et al. Reduced antiretroviral drug susceptibility among patients with primary HIV infection. JAMA. 1999;282:1142–1149. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.12.1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wittkop L, Gunthard HF, de Wolf F, Dunn D, Cozzi-Lepri A, de Luca A, et al. Effect of transmitted drug resistance on virological and immunological response to initial combination antiretroviral therapy for HIV (EuroCoord-CHAIN joint project): a European multicohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2011;11:363–371. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70032-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hingankar NK, Thorat SR, Deshpande A, Rajasekaran S, Chandrasekar C, Kumar S, et al. Initial virologic response and HIV drug resistance among HIV-infected individuals initiating first-line antiretroviral therapy at 2 clinics in Chennai and Mumbai, India. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54(Suppl 4):S348–354. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Phanuphak P, Sirivichayakul S, Jiamsakul A, Sungkanuparph S, Kumarasamy N, Lee MP, et al. Transmitted drug resistance and antiretroviral treatment outcomes in non-subtype B HIV-1-infected patients in South East Asia. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;66:74–79. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Booth CL, Geretti AM. Prevalence and determinants of transmitted antiretroviral drug resistance in HIV-1 infection. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2007;59:1047–1056. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Novak RM, Chen L, MacArthur RD, Baxter JD, Huppler Hullsiek K, Peng G, et al. Prevalence of antiretroviral drug resistance mutations in chronically HIV-infected, treatment-naive patients: implications for routine resistance screening before initiation of antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40:468–474. doi: 10.1086/427212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grant RM, Hecht FM, Warmerdam M, Liu L, Liegler T, Petropoulos CJ, et al. Time trends in primary HIV-1 drug resistance among recently infected persons. JAMA. 2002;288:181–188. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.2.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stadeli KM, Richman DD. Rates of emergence of HIV drug resistance in resource-limited settings: a systematic review. Antivir Ther. 2013;18:115–123. doi: 10.3851/IMP2437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pham QD, Wilson DP, Law MG, Kelleher AD, Zhang L. Global burden of transmitted HIV drug resistance and HIV-exposure categories: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS. 2014;28:2751–2762. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boden D, Hurley A, Zhang L, Cao Y, Guo Y, Jones E, et al. HIV-1 drug resistance in newly infected individuals. JAMA. 1999;282:1135–1141. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.12.1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weinstock H, Respess R, Heneine W, Petropoulos CJ, Hellmann NS, Luo CC, et al. Prevalence of mutations associated with reduced antiretroviral drug susceptibility among human immunodeficiency virus type 1 seroconverters in the United States, 1993-1998. J Infect Dis. 2000;182:330–333. doi: 10.1086/315686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Little SJ, Holte S, Routy JP, Daar ES, Markowitz M, Collier AC, et al. Antiretroviral-drug resistance among patients recently infected with HIV. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:385–394. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa013552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Simon V, Vanderhoeven J, Hurley A, Ramratnam B, Louie M, Dawson K, et al. Evolving patterns of HIV-1 resistance to antiretroviral agents in newly infected individuals. AIDS. 2002;16:1511–1519. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200207260-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weinstock HS, Zaidi I, Heneine W, Bennett D, Garcia-Lerma JG, Douglas JM, Jr, et al. The epidemiology of antiretroviral drug resistance among drug-naive HIV-1-infected persons in 10 US cities. J Infect Dis. 2004;189:2174–2180. doi: 10.1086/420789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bennett D, McCormick L, Kline R. US surveillance of HIV drug resistance at diagnosis using HIV diagnostic sera. 12th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI); Boston, MA. February 22-25, 2005; Abstract 674. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shet A, Berry L, Mohri H, Mehandru S, Chung C, Kim A, et al. Tracking the prevalence of transmitted antiretroviral drug-resistant HIV-1: a decade of experience. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;41:439–446. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000219290.49152.6a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parker MM, Gordon D, Reilly A, Horowitz HW, Waters M, Bennett R, et al. Prevalence of drug-resistant and nonsubtype B HIV strains in antiretroviral-naive, HIV-infected individuals in New York State. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2007;21:644–652. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.0172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wheeler W, Mahle K, Bodnar U. Antiretroviral drug-resistance mutations and subtypes in drug-naïve persons newly diagnosed with HIV-1 infection, United States, March 2003 to October 2006. 14th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI); Los Angeles, CA. February 25-28, 2007; Abstract 648. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ross L, Lim ML, Liao Q, Wine B, Rodriguez AE, Weinberg W, et al. Prevalence of antiretroviral drug resistance and resistance-associated mutations in antiretroviral therapy-naive HIV-infected individuals from 40 United States cities. HIV Clin Trials. 2007;8:1–8. doi: 10.1310/hct0801-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith D, Moini N, Pesano R, Cachay E, Aiem H, Lie Y, et al. Clinical utility of HIV standard genotyping among antiretroviral-naive individuals with unknown duration of infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:456–458. doi: 10.1086/510748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hurt CB, McCoy SI, Kuruc J, Nelson JA, Kerkau M, Fiscus S, et al. Transmitted antiretroviral drug resistance among acute and recent HIV infections in North Carolina from 1998 to 2007. Antivir Ther. 2009;14:673–678. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wheeler WH, Ziebell RA, Zabina H, Pieniazek D, Prejean J, Bodnar UR, et al. Prevalence of transmitted drug resistance associated mutations and HIV-1 subtypes in new HIV-1 diagnoses, U.S.-2006. AIDS. 2010;24:1203–1212. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283388742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Youmans E, Tripathi A, Albrecht H, Gibson JJ, Duffus WA. Transmitted antiretroviral drug resistance in individuals with newly diagnosed HIV infection: South Carolina 2005-2009. South Med J. 2011;104:95–101. doi: 10.1097/SMJ.0b013e3181fcd75b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sey K, Ma Y, Lan YC, Song N, Hu YW, Ou Y, et al. Prevalence and circulation patterns of Variant, Atypical and Resistant HIV in Los Angeles County (2007-2009) J Med Virol. 2014;86:1639–1647. doi: 10.1002/jmv.23989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim D, Ziebell R, Saduvala N. Trend in transmitted HIV-1 ARV drug resistance-associated mutations: 10 HIV surveillance areas, US, 2007-2010. 20th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI); Atlanta, GA. March 3-6, 2013; Abstract 149. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tilghman MW, Perez-Santiago J, Osorio G, Little SJ, Richman DD, Mathews WC, et al. Community HIV-1 drug resistance is associated with transmitted drug resistance. HIV Med. 2014;15:339–346. doi: 10.1111/hiv.12122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smith DM, May SJ, Tweeten S, Drumright L, Pacold ME, Kosakovsky Pond SL, et al. A public health model for the molecular surveillance of HIV transmission in San Diego, California. AIDS. 2009;23:225–232. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32831d2a81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Le T, Wright EJ, Smith DM, He W, Catano G, Okulicz JF, et al. Enhanced CD4+ T-cell recovery with earlier HIV-1 antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:218–230. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1110187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Little SJ, Kosakovsky Pond SL, Anderson CM, Young JA, Wertheim JO, Mehta SR, et al. Using HIV networks to inform real time prevention interventions. PLoS One. 2014;9:e98443. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0098443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gifford RJ, Liu TF, Rhee SY, Kiuchi M, Hue S, Pillay D, et al. The calibrated population resistance tool: standardized genotypic estimation of transmitted HIV-1 drug resistance. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1197–1198. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bennett DE, Camacho RJ, Otelea D, Kuritzkes DR, Fleury H, Kiuchi M, et al. Drug resistance mutations for surveillance of transmitted HIV-1 drug-resistance: 2009 update. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4724. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wertheim JO, Leigh Brown AJ, Hepler NL, Mehta SR, Richman DD, Smith DM, et al. The global transmission network of HIV-1. J Infect Dis. 2014;209:304–313. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tamura K, Nei M. Estimation of the number of nucleotide substitutions in the control region of mitochondrial DNA in humans and chimpanzees. Mol Biol Evol. 1993;10:512–526. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.de Oliveira T, Deforche K, Cassol S, Salminen M, Paraskevis D, Seebregts C, et al. An automated genotyping system for analysis of HIV-1 and other microbial sequences. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:3797–3800. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alcantara LC, Cassol S, Libin P, Deforche K, Pybus OG, Van Ranst M, et al. A standardized framework for accurate, high-throughput genotyping of recombinant and non-recombinant viral sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:W634–642. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kosakovsky Pond SL, Posada D, Stawiski E, Chappey C, Poon AF, Hughes G, et al. An evolutionary model-based algorithm for accurate phylogenetic breakpoint mapping and subtype prediction in HIV-1. PLoS Comput Biol. 2009;5:e1000581. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- http://www.hiv.lanl.gov/components/sequence/HIV/treemaker/treemaker.html.

- 42.Edgar RC. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:1792–1797. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hall TA. BioEdit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symposium Series. 1999;41:95–98. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Price MN, Dehal PS, Arkin AP. FastTree 2--approximately maximum-likelihood trees for large alignments. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9490. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rambaut A. FigTree v1.4.1: Tree Figure Drawing Tool. 2009 Available: http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/

- 46.Macchione N, Wooten W, Waters-Montijo K, Ginsberg M. HIV/AIDS Surveillance Program Epidemiology Report 2012. County of San Diego Health and Human Services Agency; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vega Y, Delgado E, Fernandez-Garcia A, Cuevas MT, Thomson MM, Montero V, et al. Epidemiological Surveillance of HIV-1 Transmitted Drug Resistance in Spain in 2004-2012: Relevance of Transmission Clusters in the Propagation of Resistance Mutations. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0125699. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0125699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ambrosioni J, Sued O, Nicolas D, Parera M, Lopez-Dieguez M, Romero A, et al. Trends in Transmission of Drug Resistance and Prevalence of Non-B Subtypes in Patients with Acute or Recent HIV-1 Infection in Barcelona in the Last 16 Years (1997-2012) PLoS One. 2015;10:e0125837. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0125837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rhee SY, Blanco JL, Jordan MR, Taylor J, Lemey P, Varghese V, et al. Geographic and temporal trends in the molecular epidemiology and genetic mechanisms of transmitted HIV-1 drug resistance: an individual-patient- and sequence-level meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2015;12:e1001810. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vercauteren J, Wensing AM, van de Vijver DA, Albert J, Balotta C, Hamouda O, et al. Transmission of drug-resistant HIV-1 is stabilizing in Europe. J Infect Dis. 2009;200:1503–1508. doi: 10.1086/644505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jain V, Sucupira MC, Bacchetti P, Hartogensis W, Diaz RS, Kallas EG, et al. Differential persistence of transmitted HIV-1 drug resistance mutation classes. J Infect Dis. 2011;203:1174–1181. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiq167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Staszewski S, Morales-Ramirez J, Tashima KT, Rachlis A, Skiest D, Stanford J, et al. Efavirenz plus zidovudine and lamivudine, efavirenz plus indinavir, and indinavir plus zidovudine and lamivudine in the treatment of HIV-1 infection in adults. Study 006 Team. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1865–1873. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199912163412501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Parienti JJ, Bangsberg DR, Verdon R, Gardner EM. Better adherence with once-daily antiretroviral regimens: a meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48:484–488. doi: 10.1086/596482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Carpenter CC, Cooper DA, Fischl MA, Gatell JM, Gazzard BG, Hammer SM, et al. Antiretroviral therapy in adults: updated recommendations of the International AIDS Society-USA Panel. JAMA. 2000;283:381–390. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.3.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yeni PG, Hammer SM, Carpenter CC, Cooper DA, Fischl MA, Gatell JM, et al. Antiretroviral treatment for adult HIV infection in 2002: updated recommendations of the International AIDS Society-USA Panel. JAMA. 2002;288:222–235. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.2.222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yeni PG, Hammer SM, Hirsch MS, Saag MS, Schechter M, Carpenter CC, et al. Treatment for adult HIV infection: 2004 recommendations of the International AIDS Society-USA Panel. JAMA. 2004;292:251–265. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.2.251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Deeks SG. International perspectives on antiretroviral resistance. Nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor resistance. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2001;26 Suppl 1:S25–33. doi: 10.1097/00042560-200103011-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gianotti N, Galli L, Boeri E, Maillard M, Serra G, Ratti D, et al. In vivo dynamics of the K103N mutation following the withdrawal of non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors in Human Immunodeficiency Virus-infected patients. New Microbiol. 2005;28:319–326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hare CB, Mellors J, Krambrink A, Su Z, Skiest D, Margolis DM, et al. Detection of nonnucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitor-resistant HIV-1 after discontinuation of virologically suppressive antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47:421–424. doi: 10.1086/589867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Palmer S, Boltz V, Maldarelli F, Kearney M, Halvas EK, Rock D, et al. Selection and persistence of non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor-resistant HIV-1 in patients starting and stopping non-nucleoside therapy. AIDS. 2006;20:701–710. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000216370.69066.7f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bacheler L, Jeffrey S, Hanna G, D'Aquila R, Wallace L, Logue K, et al. Genotypic correlates of phenotypic resistance to efavirenz in virus isolates from patients failing nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor therapy. J Virol. 2001;75:4999–5008. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.11.4999-5008.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lindstrom A, Ohlis A, Huigen M, Nijhuis M, Berglund T, Bratt G, et al. HIV-1 transmission cluster with M41L ‘singleton’ mutation and decreased transmission of resistance in newly diagnosed Swedish homosexual men. Antivir Ther. 2006;11:1031–1039. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Shafer RW, Rhee SY, Pillay D, Miller V, Sandstrom P, Schapiro JM, et al. HIV-1 protease and reverse transcriptase mutations for drug resistance surveillance. AIDS. 2007;21:215–223. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328011e691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Little SJ, Frost SD, Wong JK, Smith DM, Pond SL, Ignacio CC, et al. Persistence of transmitted drug resistance among subjects with primary human immunodeficiency virus infection. J Virol. 2008;82:5510–5518. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02579-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Brenner BG, Routy JP, Petrella M, Moisi D, Oliveira M, Detorio M, et al. Persistence and fitness of multidrug-resistant human immunodeficiency virus type 1 acquired in primary infection. J Virol. 2002;76:1753–1761. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.4.1753-1761.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pao D, Andrady U, Clarke J, Dean G, Drake S, Fisher M, et al. Long-term persistence of primary genotypic resistance after HIV-1 seroconversion. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2004;37:1570–1573. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200412150-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rhee SY, Taylor J, Fessel WJ, Kaufman D, Towner W, Troia P, et al. HIV-1 protease mutations and protease inhibitor cross-resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54:4253–4261. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00574-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wensing AM, van Maarseveen NM, Nijhuis M. Fifteen years of HIV Protease Inhibitors: raising the barrier to resistance. Antiviral Res. 2010;85:59–74. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2009.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-1-infected adults and adolescents. Department of Health and Human Services; [Accessed November 17, 2014]. Available at http://aidsinfo.nih.gov/contentfiles/lvguidelines/AdultandAdolescentGL.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gunthard HF, Aberg JA, Eron JJ, Hoy JF, Telenti A, Benson CA, et al. Antiretroviral treatment of adult HIV infection: 2014 recommendations of the International Antiviral Society-USA Panel. JAMA. 2014;312:410–425. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.8722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Young B, Fransen S, Greenberg KS, Thomas A, Martens S, St Clair M, et al. Transmission of integrase strand-transfer inhibitor multidrug-resistant HIV-1: case report and response to raltegravir-containing antiretroviral therapy. Antivir Ther. 2011;16:253–256. doi: 10.3851/IMP1748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Boyd SD, Maldarelli F, Sereti I, Ouedraogo GL, Rehm CA, Boltz V, et al. Transmitted raltegravir resistance in an HIV-1 CRF_AG-infected patient. Antivir Ther. 2011;16:257–261. doi: 10.3851/IMP1749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Stekler JD, McKernan J, Milne R, Tapia KA, Mykhalchenko K, Holte S, et al. Lack of resistance to integrase inhibitors among antiretroviral-naive subjects with primary HIV-1 infection, 2007-2013. Antivir Ther. 2014 doi: 10.3851/IMP2780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bhaskaran K, Pillay D, Walker AS, Fisher M, Hawkins D, Gilson R, et al. Do patients who are infected with drug-resistant HIV have a different CD4 cell decline after seroconversion? An exploratory analysis in the UK Register of HIV Seroconverters. AIDS. 2004;18:1471–1473. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000131341.45795.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Booth CL, Garcia-Diaz AM, Youle MS, Johnson MA, Phillips A, Geretti AM. Prevalence and predictors of antiretroviral drug resistance in newly diagnosed HIV-1 infection. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2007;59:517–524. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkl501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sungkanuparph S, Oyomopito R, Sirivichayakul S, Sirisanthana T, Li PC, Kantipong P, et al. HIV-1 drug resistance mutations among antiretroviral-naive HIV-1-infected patients in Asia: results from the TREAT Asia Studies to Evaluate Resistance-Monitoring Study. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:1053–1057. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Banez Ocfemia M, Saduval N, Oster A. Transmitted HIV-1 drug resistance among men who have sex with men, 11 US jurisdictions, 2008-2011. CROI 2014. 21st Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI); Boston, MA. March 3-6, 2014; Abstract 579. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Brenner BG, Roger M, Moisi DD, Oliveira M, Hardy I, Turgel R, et al. Transmission networks of drug resistance acquired in primary/early stage HIV infection. AIDS. 2008;22:2509–2515. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283121c90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Morris SR, Little SJ, Cunningham T, Garfein RS, Richman DD, Smith DM. Evaluation of an HIV nucleic acid testing program with automated Internet and voicemail systems to deliver results. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:778–785. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-152-12-201006150-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rosenberg ES, Altfeld M, Poon SH, Phillips MN, Wilkes BM, Eldridge RL, et al. Immune control of HIV-1 after early treatment of acute infection. Nature. 2000;407:523–526. doi: 10.1038/35035103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.