Abstract

Plasmodium salivary sporozoites are the infectious form of the malaria parasite and are dormant inside salivary glands of Anopheles mosquitoes. During dormancy, protein translation is inhibited by the kinase UIS1 that phosphorylates serine 59 in the eukaryotic initiation factor 2α (eIF2α). De-phosphorylation of eIF2α-P is required for the transformation of sporozoites into the liver stage. In mammalian cells, the de-phosphorylation of eIF2α-P is mediated by the protein phosphatase 1 (PP1). Using a series of genetically knockout parasites we showed that in malaria sporozoites, contrary to mammalian cells, the eIF2α-P phosphatase is a member of the PP2C/PPM phosphatase family termed UIS2. We found that eIF2α was highly phosphorylated in uis2 conditional knockout sporozoites. These mutant sporozoites maintained the crescent shape after delivery into mammalian host and lost their infectivity. Both uis1 and uis2 were highly transcribed in the salivary gland sporozoites but uis2 expression was inhibited by the Pumilio protein Puf2. The repression of uis2 expression was alleviated when sporozoites developed into liver stage. While most eukaryotic phosphatases interact transiently with their substrates, UIS2 stably bound to phosphorylated eIF2α, raising the possibility that high-throughput searches may identify chemicals that disrupt this interaction and prevent malaria infection.

Author Summary

Malaria is transmitted to humans by female mosquitoes as they take a blood meal. Plasmodium sporozoites are the infectious and quiescent forms of malaria parasites, which reside in the salivary glands of mosquitoes. Global protein synthesis is inhibited in sporozoites through phosphorylation of the translational factor eIF2α. However, the development of the parasites in the host liver requires de-phosphorylation of eIF2α-P. We find that a unique Plasmodium phosphatase termed UIS2 de-phosphorylates eIF2α-P in malaria. The eIF2α is highly phosphorylated in the uis2 mutant sporozoites. The uis2 mutant parasites did not change their morphology after delivery into the host and could not properly infect the host. We also showed that UIS2 expression was inhibited by the Pumilio protein Puf2. However, this repression was relieved when sporozoites developed into liver stage. In sum, our findings revealed a new mechanism that evolved to control eIF2α dephosphorylation and suggest that identification of UIS2 inhibitors may be useful in anti-malaria therapy.

Introduction

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease of humans and other animals caused by parasitic protozoans of the genus Plasmodium. In 2013, there were 198 million cases of malaria and 584,000 fatalities (WHO world malaria report 2014), underscoring its role as a major pathogen. Sporozoites are the infectious and quiescent forms of the malaria parasite residing in the salivary glands of Anopheles mosquitoes. Malaria transmission begins with the injection of salivary sporozoites (Ssp) into the skin of a vertebrate host by infected mosquitoes. The parasites enter the blood circulation and rapidly invade hepatocytes where the crescent-shaped sporozoite progressively transforms into a spherical liver stage (or exo-erythrocytic stage, EEF). Many genes required for the Ssp transformation into liver stages are transcribed in the Ssp [1–3]. However, translation is repressed by phosphorylation of eIF2α by eIK2 kinase, also named UIS1 (UIS, Upregulated in Infective Sporozoites) [4, 5]. If the eIK2 kinase uis1 is knocked out, the Ssp transcripts are translated prematurely while sporozoites are still inside the salivary glands of mosquitoes [4]. During the normal parasite cycle, liver-stage transcripts are only translated when Ssp enter hepatocytes and eIF2α-P is de-phosphorylated [6]. Thus, Ssp quiescence is regulated by phosphorylation and de-phosphorylation of eIF2α.

Parasites rapidly multiply inside hepatocytes and generate thousands of merozoites that enter the blood and infect host erythrocytes where they grow, multiply, and transform into schizonts that contain additional infective merozoites. Following entry of merozoites into erythrocytes, a phosphatase must de-phosphorylate eIF2α-P to permit the completion of the parasite’s cycle [7]. Treatment of Ssp with salubrinal, a specific inhibitor of eIF2α phosphatase [8], markedly increases eIF2α phosphorylation in the parasite and inhibits their transformation into liver stages [4, 6]. The central role of eIF2α-P phosphatases in the Plasmodium life cycle is highlighted by the observation that the parasites are not viable if they bear the phosphomimetic mutation Ser59Asp in eIF2α that cannot be de-phosphorylated [7]. Nevertheless, no eIF2α-P phosphatase has been identified in Ssp.

In mammalian cells, the de-phosphorylation of eIF2α-P is mediated by the PP1 phosphatase whose activity requires the co-factor GADD34 (Growth Arrest and DNA Damage-Inducible Protein) or its homologue CReP [9]. The substrate specificity of PP1 and its localization are regulated by association with these co-factors [10]. Nevertheless, GADD34/CReP is absent in Plasmodium and the molecular mechanism of eIF2α-P de-phosphorylation in the parasite is still unknown. Here we show that the knockout of pp1 in P. berghei sporozoites did not affect Ssp quiescence or the levels of eIF2α phosphorylation. These findings excluded a central role of PP1 in the transformation of Ssp into liver stages. We provide evidence that the eIF2α-P phosphatase in Plasmodium is a unique serine/threonine phosphatase belonging to the PP2C/PPM family and termed UIS2 [11]. We also show that expression of this phosphatase is regulated at the protein level to support proper parasite development.

Results

PP1 is not the eIF-2α-P phosphatase in Plasmodium Ssp

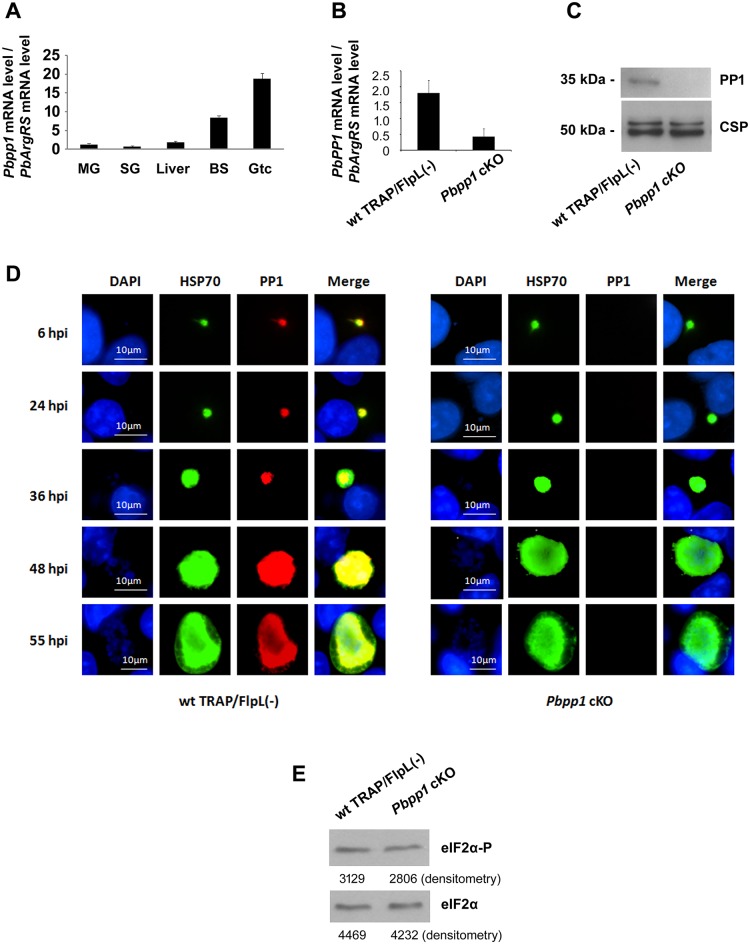

Plasmodium pp1 transcription takes place during the erythrocytic cycle (Fig 1A), which occurs predominantly in gametocytes. To test whether PP1 phosphorylates eIF-2α, we attempted to knock out pp1 in P. berghei erythrocytic schizonts (S1 Fig and S1 Table) but two attempts failed, supporting previous findings demonstrating that this gene is essential for blood stage development [12, 13]. In fact, we showed that high levels of pp1 mRNA was present in the erythrocytic cycle (Fig 1A). We obtained instead a P. berghei pp1 conditional knockout (cKO) using the FlpL/FRT site-specific recombination system (S2 Fig) [14]. In these Pbpp1 cKO parasites, pp1 locus was intact in the blood stages (S2 and S3 Figs) and pp1 genomic locus was disrupted only when the parasites were developing into sporozoites in mosquito (S3B Fig) [14]. The pp1 mRNA level was significantly decreased in these mutants (Fig 1B) and PP1 protein was not detected in Pbpp1 cKO Ssp (Fig 1C). The pp1 cKO parasites completed the life cycle in Anopheles mosquitoes and produced similar numbers of midgut and salivary gland sporozoites as the wild type (wt) (S4 Fig). This is consistent with the low level of Pbpp1 mRNA in the mosquito vector (Fig 1A). The mutant sporozoites then developed into liver stages and produced hepatic merozoites in vitro as shown by IFA (Fig 1D). PP1 was disrupted in 96.3% (SD +/- 4.6%) of the hepatic schizonts (S5 Fig). Quantitative PCR analysis showed that the liver stage development of Pbpp1 cKO Ssp in HepG2 cells and in mice was indistinguishable from the wild type TRAP/FlpL(-) Ssp (S6 Fig). However, the pp1 cKO merozoites exiting the hepatocytes did not infect the mouse blood (S7 Fig). Thus, these findings corroborate the essential role of pp1 in the parasite´s erythrocytic cycle. In addition, the levels of phosphorylation of eIF2α in wt and pp1 cKO sporozoites were indistinguishable by immunoblot (Fig 1E). In sum, PP1 is not the enzyme that de-phosphorylates eIF2α-P, which is required for liver stage transformation of Ssp.

Fig 1. Characterization of Plasmodium pp1 (PBANKA_102830).

(A) pp1 mRNA levels during the P. berghei life cycle. Pbpp1 mRNA levels were analyzed by real-time PCR using cDNAs from the different stages of P. berghei. The arginyl-tRNA synthetase (PbArgRS, PB000094.03.0) was used as internal control. Each value is the mean ± SD of two independent experiments. MG: midgut; SG: salivary gland; Liver: liver stages; BS: asexual blood stages; Gtc: gametocyte. (B) Pbpp1 mRNA levels in Pbpp1 cKO Ssp were quantified by qPCR. P = 0.041. P value was calculated by t test. Shown are mean ± SD of two independent experiments. (C) Immunoblot analysis of Pbpp1 cKO and wt TRAP/FlpL(-) Ssp using anti-PbPP1 serum. CSP was used as control. (D) The liver stage development of Pbpp1 cKO Ssp in HepG2 cells was indistinguishable from the wild type TRAP/FlpL(-) Ssp. Hepatic parasites were stained with anti-PbHSP70 and anti-PbPP1 antibodies at 6h, 24h, 36h, 48h, and 55h post-infection. Bar, 10 μm. (E) eIF2α phosphorylation level in Pbpp1 cKO sporozoites was indistinguishable from wild type. Five hundred thousand wt TRAP/FlpL(-) or Pbpp1 cKO sporozoites were dissected from mosquito salivary glands. Levels of PbeIF2α-P and total PbeIF2α were quantified by densitometry analysis of immunoblots performed with antibodies against anti-eIF2α-P and anti-total eIF2α [15, 16]. Values are shown below the bands. Results were similar in two independent experiments.

UIS2 Interacts with eIF2α-P

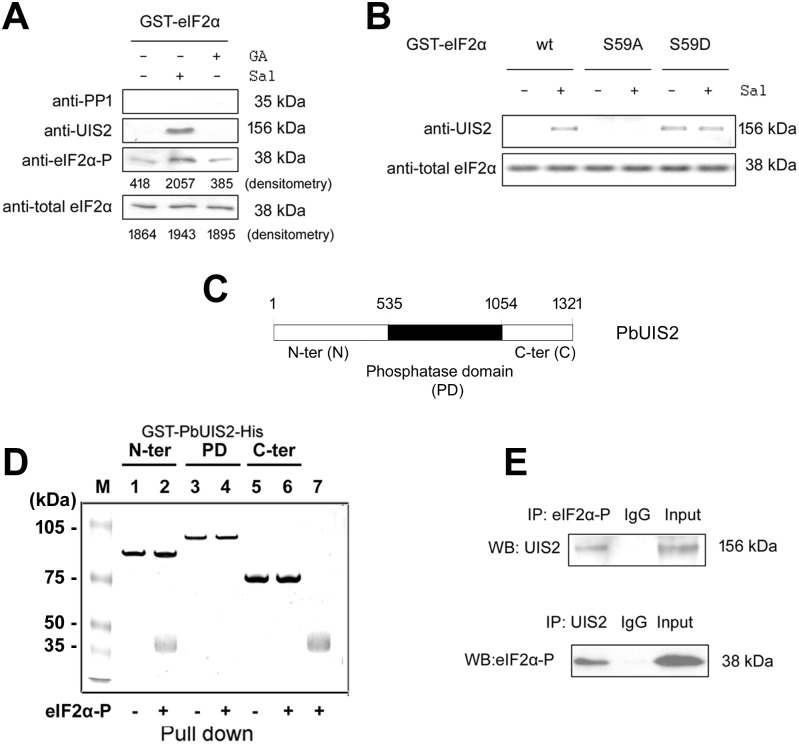

Plasmodium sporozoites up-regulate a unique subset of genes in the mosquito salivary glands collectively termed UIS [5, 17]. UIS1 (eIK2) is an eIF2α kinase that controls the latency of Ssp [4] and UIS2 is the only phosphatase among the 30 uis genes [5]. Thus, we reasoned that UIS2 could be a candidate to de-phosphorylate eIF2α-P when Ssp transform into liver stages. To test this possibility, we first performed pull-down assays to determine whether UIS2 interacts with eIF2α-P using extracts from P. berghei blood stage parasites. To inhibit endogenous phosphatases in the extracts, we added either salubrinal [Sal, a selective inhibitor of eIF2α phosphatase [4, 8]], or guanabenz acetate [GA, a selective inhibitor of PP1 [18]]. The lysates were then incubated with immobilized GST-PfeIF2α. The beads were extensively washed and the bound parasite proteins were detected by immunoblot analysis. We found that endogenous UIS2 was pulled-down by GST-eIF2α from the lysates containing Sal but not from those lysates containing GA (Fig 2A top 2 panels and S8 Fig). The pull down of UIS2 was associated with the phosphorylation of GST-PfeIF2α (Fig 2A bottom 2 panels), indicating that UIS2 only bound phosphorylated PfeIF2α. Further evidence for the specificity of UIS2/eIF2α-P interaction was obtained by generating mutants of PfeIF2α in which the regulatory ser59 was substituted either with alanine or with aspartic acid that mimics a phosphorylated serine. The PfeIF2αS59D bound UIS2 but PfeIF2αS59A did not interact with UIS2 (Fig 2B).

Fig 2. The N-terminus of UIS2 binds eIF2α-P.

(A) PfeIF2α-P interacts with endogenous UIS2. In these experiments we used the codon-optimized eIF2α of P. falciparum [7] that shares 89% identity with its P. berghei ortholog. The immobilized GST-PfeIF2α was incubated with the lysates of P. berghei blood stage parasites in the presence or absence of Sal (50 μM) or GA (70 μM). The bound proteins were detected by immunoblot using antibodies against PP1, UIS2, phosphorylated eIF2α, and total eIF2α. Levels of PbeIF2α-P and total PbeIF2α were quantified by densitometry analysis. See also S8 Fig: The mouse anti-PbPP1 antibody recognized the 35 kDa endogenous PP1 from the parasite lysates. (B) PfeIF2αS59D mutant protein interaction with UIS2. The immobilized GST-PfeIF2α wt, S59A, or S59D were incubated with the lysates of P. berghei blood stage parasites, with or without Sal, and UIS2 was detected by immunoblot. (C) Schematic representation of the PbUIS2 coding sequence. UIS2 contains a putative conserved phosphatase domain (PD, 535–1054 amino acids) and Plasmodium specific sequences at N- and C- terminus. (D) The N-terminus of PbUIS2 bound PfeIF2α-P. The PbUIS2 N-ter, PD, and C-ter were fused to GST-tag at their N-terminus and His-tag at their C-terminus, respectively. After 2-step affinity purification, the E. coli expressed fusion proteins were immobilized on glutathione sepharose 4B. After incubation with purified recombinant PfeIF2α-P, the sepharose was washed three times with high-salt NETN buffer (300 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 0.5 mM EDTA, and 0.5% (v/v) Nonidet P-40). The retained proteins were detected by SDS-PAGE followed by coomassie brilliant blue staining. Lane 1,3,5: GST and His-tagged PbUIS2 N-ter, PD, and C-ter, respectively. Lane 2,4,6: proteins retained on the glutathione sepharose 4B after pull down assays with PfeIF2α-P. Lane 7, PfeIF2α-P control. The pulled down 38 kDa protein in lane 2 was analyzed by mass spectrometry and identified as PfeIF2α-P. See also S9 Fig. (E) Co-immunoprecipitation (IP) of endogenous complex between UIS2 and eIF2α-P. Whole cell extracts from P. berghei blood stage parasites were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-eIF2α-P or anti-UIS2 antibodies followed by immunoblot analysis.

Plasmodium UIS2 contains a predicted metallo-phosphatase domain enclosed by large N and C-terminal domains (Fig 2C). To determine which domain binds PfeIF2α-P, we expressed the recombinant domains of UIS2 in E. coli. We show in Fig 2D that only the UIS2 N-terminus stably bound to eIF2α-P but not to non-phosphorylated PfeIF2α (S9 Fig). The association between UIS2 and eIF2α-P under physiological conditions was documented in extracts of P. berghei erythrocytic parasites by co-immunoprecipitation with anti-eIF2α-P or anti-UIS2 antibodies followed by immunoblot analysis (Fig 2E).

Properties of the UIS2 phosphatase domain

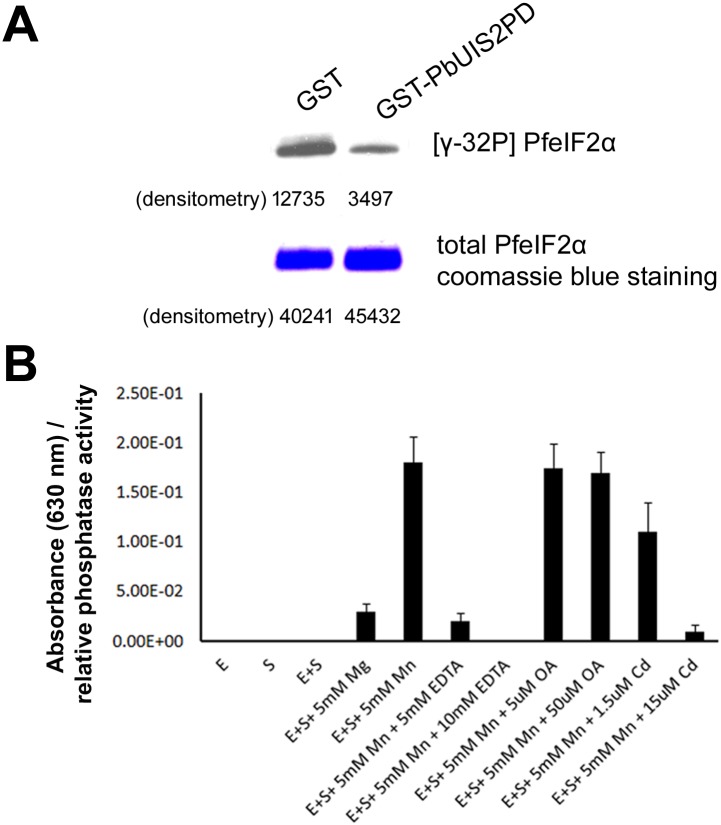

Next, we tested whether the UIS2 phophatase domain dephosphorylated eIF2α-P. Indeed, we found that the recombinant GST-PbUIS2PD was able to dephosphorylate eIF2α-P in vitro (Fig 3A). The activity of the phosphatase was inhibited by EDTA and Cd2+ (Fig 3B), which are inhibitors of the PP2C/PPM [19, 20], but was unaffected by okadaic acid (Fig 3B), which inhibits PP1 (IC50 = 15–20 nM) and PP2A (IC50 = 0.1 nM). The phosphatase displayed a strong preference for Mn2+ over Mg2+ (Fig 3B). Thus, PbUIS2 activity is similar to that of the PP2C/PPM family of phosphatases [21].

Fig 3. PbeIF2α-P phosphatase activity of UIS2.

(A) PbUIS2 phosphatase domain (PD) dephosphorylated eIF2α-P in vitro. PfeIF2α-P[γ-32P] was incubated with GST-PbUIS2PD in the presence of 5mM MnCl2. (B) Characterization of PbUIS2 as a PP2C/PPM phosphatase. PbUIS2PD phosphatase activity was measured by malachite green colorimetric assay in the presence of EDTA, okadaic acid (OA), or CdCl2. E: GST-PbUIS2PD; S: eIF2α-P. The inorganic phosphate was detected with malachite green by measuring the absorbance at 630 nm. Each value is the mean ± SD of three independent experiments.

Generation of uis2 cKO parasites

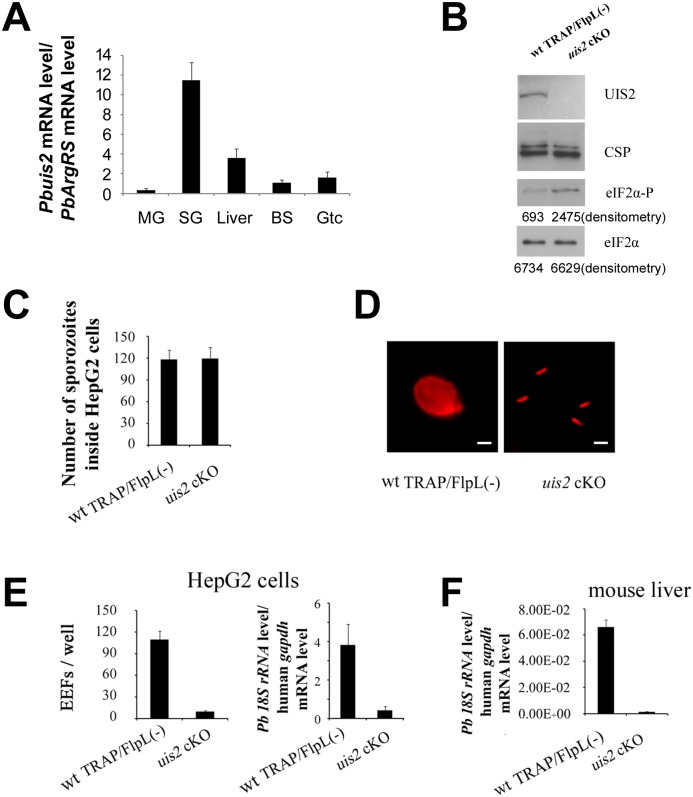

We then investigated the expression pattern and levels of the phosphatase uis2 during the P. berghei life cycle (Fig 4A). Transcripts were detected during the liver, erythrocytic and mosquito stages. Notably, uis2 mRNA level increased substantially when midgut sporozoites entered the salivary glands of Anopheles. This is consistent with the results of subtractive cDNA hybridization between P. berghei Ssp and midgut sporozoites [5] and with the comparative microarray analysis of P. yoelii midgut sporozoites and Ssp [17, 22]. The presence of the UIS2 protein in the Ssp was then detected by immunoblot (Fig 4B). The uis2 transcript is also present in the blood stages (Fig 4A). The presence of UIS2 in the P. berghei blood stage parasites was detected by pull down and co-IP assays (Fig 2). To further investigate the uis2 function, we first tried to knock out the gene in P. berghei blood stages where uis2 mRNA levels are very low (Fig 4A); however, several attempts failed (S10 Fig). This result indicated that uis2 is essential for the development of the Plasmodium erythrocytic cycle. Next, we utilized the yeast FlpL/FRT site-specific recombination system to generate the cKO of the uis2 gene (S1 Text and S11A Fig) [14]. In the uis2 cKO construct, the 3’UTR of TRAP together with DHFR flanked by 2 FRT sites were inserted after the stop codon of uis2. We then demonstrated the correct integration of the uis2 cKO clone in the uis2 genome locus (S11B Fig). The FlpL recombinase was under the control of the TRAP gene promoter that is only transcribed when the parasite reaches the mosquito midgut. Since there was no expression of FlpL recombinase in the blood stages, the uis2 cassette was not affected. When uis2 cKO reached the mosquito midgut, the uis2 locus was disrupted (S11C Fig). The disruption of uis2 expression was confirmed by immunoblot with specific antibodies (Fig 4B).

Fig 4. Phenotypes of uis2 cKO parasites.

(A) mRNA levels of uis2 in the P. bergthei life cycle. Pbuis2 (PBANKA_132800) mRNA levels were analyzed by real-time PCR using cDNAs from different stages of P. berghei. mRNA level was normalized to arginyl-tRNA synthetase (PbArgRS, PB000094.03.0). MG: midgut; SG: salivary gland; Liver: liver stages; BS: asexual blood stages; Gtc: gametocytes. Each value is the mean ± SD of two independent experiments. (B) Phosphorylation level of eIF2α was higher in uis2 cKO Ssp. Levels of UIS2, PbeIF2α-P and total PbeIF2α from 5X105 Ssp are shown by immunoblots. CSP was used as a control. Values of densitometry analysis are shown below the bands. This experiment was repeated three times and similar results were obtained. (C) The mutant sporozoites invaded HepG2 cells as effectively as wt parasites. Wild-type TRAP/FlpL(-) and uis2 cKO Ssp were added to HepG2 cells and fixed 1 h post-infection. The parasites inside and outside the HepG2 cells were quantified by the hepatocyte invasion assay. Each value is the mean ± SD of two independent experiments. ( D ) The mutant parasites maintained the crescent shape in contrast to the round shape of the wt parasites in HepG2 cells. Wt TRAP/FlpL(-) and uis2 cKO Ssp were added to HepG2 cells and were detected 48 h post-infection by immunofluorescence using antibodies against the liver stage antigen UIS4. Bars, 10 μm. (E) The development of uis2 cKO sporozoites was blocked inside HepG2 cells. P. berghei Ssp infectivity of HepG2 cells was evaluated 48 h post-infection by counting exo-erythrocytic stage (EEF) numbers and measuring18S rRNA level. The left panel shows the mean of EEF numbers ± SD of two independent experiments. The right panel shows liver-stage parasite burden measured by real-time RT-PCR. (F) The development of uis2 cKO sporozoites was blocked in the mouse liver. C57BL/6 mice (five per group) were injected intravenously with 1×104 wt TRAP/FlpL(-) or with the same number of uis2 cKO Ssp. Liver-stage parasite burden was measured 42 hours post-infection by real-time RT-PCR. Each value is the mean ± SD of two independent experiments.

UIS2 is essential for Plasmodium development in liver stages

The uis2 cKO parasite developed normally in the mosquito vector. The number of Ssp in uis2 cKO and wt parasites was very similar (S12 Fig). Next, we compared the phosphorylation levels of eIF2α in Ssp obtained from uis2 cKO and from wt parasites by immunoblot using specific antibodies [7, 15, 16, 23]. We found that phosphorylation of eIF2α was greatly enhanced in the absence of the uis2 phosphatase (Fig 4B) and the mutant sporozoites invaded HepG2 cells as effectively as wt (Fig 4C). Nevertheless, the development of the uis2 cKO Ssp in HepG2 cells was profoundly inhibited two days post-infection: the mutants maintained the sporozoite shape while the wt parasites rounded up and developed into spherical liver stages (Fig 4D). In addition, the number of exo-erythrocytic forms (EEFs) and the P. berghei 18S rRNA of the uis2 cKO parasites were profoundly decreased in the liver stages as compared to the wt parasites (Fig 4E and 4F).

When the uis2 cKO sporozoites were injected into mice either by mosquito bite or by intravenous injection, only 4 out of 11 mice were infected as detected by Giemsa staining of blood smears. In addition, the pre-patent day was delayed for 3 days in the 4 mice infected with the uis2 cKO sporozoites as compared to wt (Table 1). We then examined the genotype of the blood and liver stage parasites originated by uis2 cKO sporozoites. The parasites were uis2 (+) and expressed the UIS2 antigen as the wt (S13 Fig), indicating that the uis2 locus had not been completely excised by the recombinase FlpL. The incomplete excision in the FlpL/FRT-mediated conditional mutagenesis system has been previously reported [14]. The overall conclusion of these experiments is that uis2 is essential for liver stage development.

Table 1. Infectivity of wt TRAP/Flp(-) and uis2 cKO sporozoites in C57BL/6 mice.

| Infection | wt TRAP/FlpL(-) | Uis2 cKO | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| infected / total | PPDs* (no. of mice) | infected / total | PPDs* (no. of mice) | |

| mosquito bite§ | 6 / 6 | 4(6) | 2 / 6 | 7(2) |

| intravenous injection# | 5 / 5 | 4(5) | 2 / 5 | 7(2) |

* Pre-patent day (PPD): Number of days after sporozoites inoculation until detection of erythrocytic stages by microscopic examination of blood smears.

§10 infected mosquitoes per mouse.

# 10,000 sporozoites per mouse.

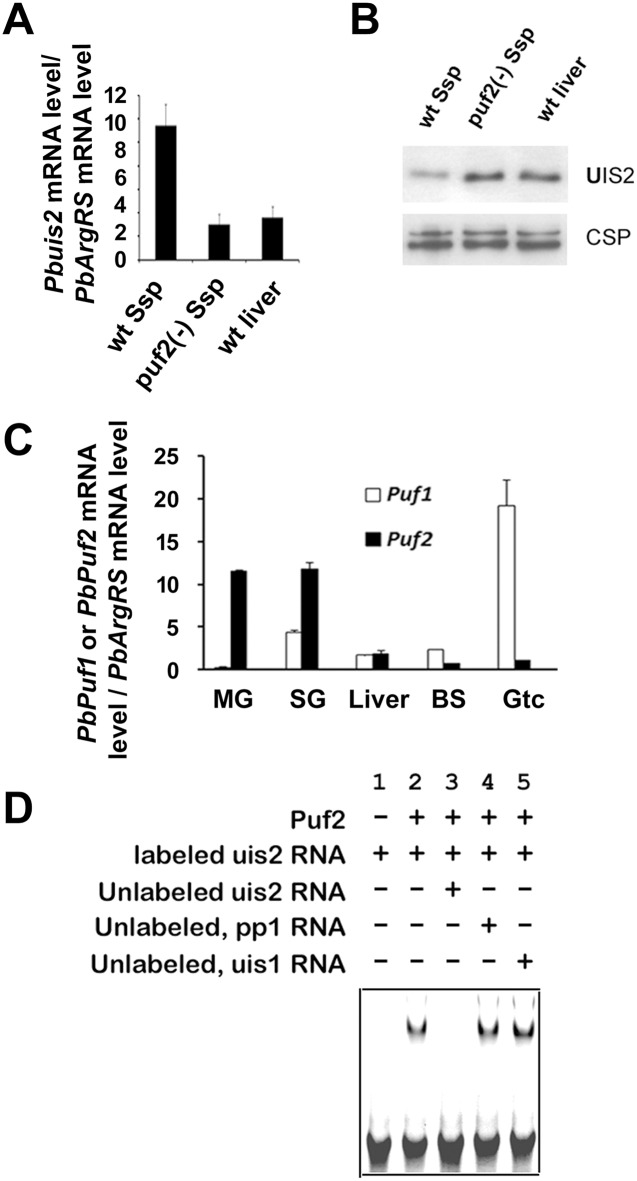

Puf2 controls UIS2 Expression

As mentioned above, when midgut sporozoites invade the salivary gland of mosquitoes uis1 and uis2 are up-regulated [5]. Yet, the uis1 kinase is dominant, inhibits protein translation, and maintains the salivary gland sporozoites in a latent state. The eIF2α-P is dephosphorylated when sporozoites are injected into the mammalian host and transform into liver stages [4, 6]. We found that the uis2 mRNA level was decreased in the liver stages as compared to the sporozoite stage (Fig 5A), which was consistent with the results of previous transcriptome analysis [24]. Nevertheless, uis2 protein level increased in the liver stages as compared to the sporozoite stages (Fig 5B). These results suggest that uis2 translation may be repressed in the sporozoite stage and the translational repression may be alleviated in host liver stages. The up-regulation of UIS2 protein level is associated with the eIF2α-P dephosphorylation in host liver [4].

Fig 5. Regulation of UIS2 expression by Puf2 in Ssp.

(A) The uis2 mRNA levels of wt Ssp, puf2(-) Ssp, and wt liver stages were measured by Real-time PCR. Each value is the mean ± SD of two independent experiments. (B) Immunoblot depicts UIS2 protein levels in wt Ssp, puf2(-) Ssp, and wt liver stages using mouse anti-UIS2 antibodies. CSP was used as internal control (n = 3). (C) mRNA levels of Puf proteins at different stages of parasite development. puf1 and puf2 mRNA levels were analyzed by real-time PCR using cDNAs from different stages of P. berghei development. mRNA levels were normalized to the control mRNA, arginyl-tRNA synthetase (PB000094.03.0). MG: midgut; SG: salivary gland; Liver: liver stages; BS: blood stages; Gtc: gametocytes. Each value is the mean ± SD of two independent experiments. (D) The uis2 mRNA binding to Puf2 was analyzed by RNA gel shift assays. Lane 1: The reaction contains only the biotinylated uis2-RNA probe (negative control). Lane 2: The band shift of the uis2-RNA probe was detected by the addition of recombinant P. berghei Puf2 protein. Lane 3: The labeled probe is outcompeted by the addition of a 200-fold excess of un-labeled uis2-RNA. Lane 4 and 5: The labeled probe was not outcompeted by the addition of a 200-fold excess of non-specific unlabeled Pbpp1 or Pbuis1 probe.

The 3’UTR of uis2 mRNA contains several putative NREs (Nanos response elements). In Drosophila and C. elegans, Pumilio protein binds to NREs on hunchback mRNA to inhibit its translation [25]. In Plasmodium there are two Pumilio proteins (Puf1 and Puf2) [26, 27]. We show in Fig 5C that puf1 is predominantly transcribed in gametocytes and puf2 in sporozoites. We then used gel shift assays to document the binding of the Pumilio protein Puf2 to the uis2 mRNA (Fig 5D). Since uis2 mRNA level was down-regulated in puf2(-) sporozoties (Fig 5A) but the UIS2 protein level was up-regulated (Fig 5B), these results suggest that Puf2 protein may inhibit uis2 translation in sporozoites. The mRNA and protein levels of UIS2 from the puf2(-) sporozoites and wt liver stages were very similar. Taken together, our findings provide the mechanistic explanation to the previous reports showing that puf2(-) sporozoites round up and start transforming into liver stages in the mosquito salivary glands [23, 28, 29]. The potential translational repression of uis2 in Ssp is consistent with the normal development of Pbuis2 cKO parasites in the mosquito salivary glands where uis2 is highly transcribed (Figs 4A and S12). As expected, the alleviation of uis2 repression during liver stages corroborates the defective development of Pbuis2 cKO parasites during liver stage where uis2 is significantly translated. Although both uis 1 and uis2 are highly transcribed in Ssp, only uis1 is dominant. Thus, it is the binding of the Pumilio protein Puf2 to the uis2 mRNAs that likely inhibits the phosphatase translation. Once translated, US2 binds to eIF2α-P but not to eIF2α. The results imply that small molecules that disrupt the essential UIS2-eIF2α-P interaction will likely interrupt establishment of parasites in hepatocytes and possibly reveal new leads to combat malaria infection.

Discussion

We show here that UIS2 is the phosphatase that controls the development of the dormant Ssp into the liver stages. Its activity is enhanced by Mn2+, inhibited by Cd2+, but is not affected by okadaic acid, a powerful inhibitor of PP1 and PP2A phosphatases. Thus, UIS2 belongs to the PP2C/PPM family of phosphatases. The human genome encodes ~ 500 protein kinases, ~2/3 of which are serine/threonine kinases, and approximately 40 serine/threonine phosphatases [30, 31]. In Plasmodium, there are ~ 80 protein kinases and ~30 protein phosphatases [13, 32, 33]. These disparate numbers raise the question of how few phosphatases recognize specifically the very large number of phosphorylated proteins. In the case of the PP1 mammalian phosphatase, enzyme specificity and localization are regulated by a large number of multiple co-factors. However, this is not the case for Plasmodium UIS2 that encompasses catalytic and regulatory domains within the same polypeptide chain [21]. The N-terminal domain of UIS2 interacts stably with the eIF2α-P substrate placing it in close proximity to the catalytic site. We showed that eIF2α-P interacted with endogenous UIS2 from lysates of blood stage parasites. We did not use lysates from sporozoites because of the repression of uis2 expression by Puf2. The interaction of UIS2/ eIF2α-P is in sharp contrast to other phosphatases whose interaction with the substrate is unstable and is enhanced by co-factors. In the blood stage, the mRNA level of uis2 is very low but UIS2 is translated and is essential for the parasite’s blood stage development. However, the function of uis2 in the blood stage is unknown.

In mammalian cells, PP1 acts in conjunction with the regulatory subunit GADD34 or CReP to de-phosphorylate eIF2α-P. These co-factors are absent in Plasmodium. In yeast, the N-terminal extension on eIF2α contains a PP1-binding motif (KKVAF) that enables eIF2α to target PP1 to dephosphorylate eIF2α-P [10, 34]. PP1-binding motif is also absent in Plasmodium eIF2α. As shown here, the parasite utilizes instead the PP2C/PPM phosphatase UIS2 to regulate the phosphorylation level of eIF2α. Perhaps additional proteins have evolved to control eIF2α dephosphorylation in organisms that do not contain recognizable homologs of GADD34/CReP or PP1-binding motif (KKVAF) in eIF2α, such as in Plasmodium, S. pombe, and Aspergillus.

Small molecules have been useful to distinguish enzyme activities in different organisms. For example, the small molecule GA directly binds to PP1 and selectively inhibits the stress-induced dephosphorylation of eIF2α-P in mammalian cells and in Toxoplasma [18, 35]. Nevertheless, GA does not inhibit eIF2α-P de-phosphorylation in Plasmodium, supporting our conclusion that PP1 is not the eIF2α-P phosphatase in Plasmodium. Instead, Sal is a selective inhibitor of dephosphorylation of eIF2α-P in Plasmodium sporozoites [4]. Also shown here, levels of eIF2α-P increased substantially in the Sal treated erythrocytic stages of the parasite. However, in mammalian cells Sal inhibits GADD34/PP1 complex that is responsible for eIF2α dephosphorylation [8], but the molecular mechanism is unknown [36]. There is no ortholog of GADD34, and UIS2 is the eIF2α-P phosphatase. Therefore, the explanation of Sal effect in Plasmodium is unknown. Our findings indicate that Plasmodium has developed a different strategy to de-phosphorylate eIF2α. Thus, there is a distinct possibility that UIS2 inhibitors will have no side effects on human cells.

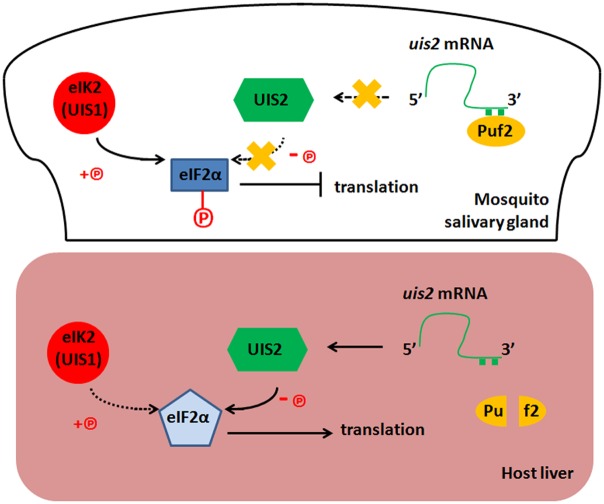

We have previously reported that uis1 encoded the eIF2α kinase eIK2 [4] and here we show that uis2 encodes the eIF2α phosphatase. It is to be expected that uis2 (-) and uis1 (-) Ssp have contrasting phenotypes. The uis2 (-) Ssp maintained sporozoite shape 48 hours post-invasion into host hepatocytes (Fig 4D). This is in contrast to the uis1 (-) Ssp, which prematurely transform into spherical liver stages in mosquito salivary glands [4, 23, 28, 29]. UIS2 is highly transcribed and translationally repressed in Ssp, but the repression is alleviated when the dormant Ssp transform into liver stages (Figs 4A, 5A and 5B). The translation of uis2 is tightly controlled by the Pumilio protein Puf2. In Drosophila and C. elegans Pumilio proteins bind to specific nucleotide motifs at the 3´ UTRs sequences of hunchback mRNAs to inhibit their translation [25]. In Plasmodium there are two Pumilio proteins (Puf1 and Puf2) [26]. Puf1 and Puf2 are transcribed predominantly in gametocytes and sporozoites, respectively [3, 25, 26]. The function of Plasmodium Puf1 is unknown and Puf2 is essential to maintain the infectivity of malaria Ssp [23, 28, 29]. Puf2 likely represses translation of uis2 mRNA in the mosquito Ssp. In puf2 (-) parasites, uis2 mRNA is translated prematurely and the parasites progressively transform into liver stages while they reside in the salivary glands [23, 28, 29]. When wt Ssp parasites are injected into the mammalian host, the translational repression of uis2 is probably alleviated, eIF2α-P is dephosphorylated [4], and liver stage messages are decoded (Fig 6).

Fig 6. Model for UIS2 function in the Plasmodium.

The eIF2α kinase eIK2 (also called UIS1) and Pumilio protein Puf2 are highly transcribed and translated in the mosquito salivary gland [3–5, 25, 26]. The highly transcribed eIF2α phosphatase uis2 mRNA binds to Puf2 and the translation of phosphatase UIS2 is likely repressed. The eIF2α of Ssp is highly phosphorylated since the eIF2α kinase eIK2 activity is dominant, leading to translation inhibition and latency of sporozoites in the mosquito salivary glands. When sporozoites are injected into the mammalian host, the repression of UIS2 translation is probably alleviated, the eIF2α phosphatase UIS2 activity is dominant, eIF2α is dephosphorylated, and Ssp transform into the liver stages. Knockout of puf2 or eIK2 contributes to the dominance of UIS2 and the mutant sporozoites inside of mosquito salivary glands prematurely transform into liver stages [4, 23, 28, 29].

In sum, the conditional knockouts of pp1 and uis2 in Ssp together with the biochemical evidence demonstrating that UIS2 binds to and de-phosphorylates eIF2α-P reveal that UIS2, and not PP1, is the eIF2α phosphatase in Plasmodium Ssp. These findings raise the possibility of using high-throughput screenings of small molecules to disrupt UIS2-eIF2α-P interaction, which is essential for the parasite’s survival, and perhaps lead to the discovery of new drugs to interrupt the parasite’s development in hepatocytes.

Materials and Methods

Ethics statement

All animal work has been conducted according to Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) Laboratory Animal Protocol: 140102.

Stage-specific mRNA levels of uis2 and pp1

Pbuis2 (PBANKA_132800) and Pbpp1 (PBANKA_102830) mRNA levels were analyzed by real-time RT-PCR using cDNA prepared from blood, liver and mosquito-stage parasites of P. berghei. Axenic liver stages of the parasite were prepared by incubation of P. berghei salivary gland sporozoites at 37°C in DMEM plus 10% FBS for 6 hours as described previously [37, 38]. Total RNAs were extracted using TRIzol reagent and treated with DNase. The absence of genomic DNA contamination was confirmed by PCR amplification on same-treated RNA samples that lacked reverse transcription. The specificity of amplification for each PCR product was confirmed by dissociation curve analysis. Real-time PCR was performed using iQ SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad Laboratories), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The 1ml reaction mix contained 1X iQ SYBR Green Supermix, 300 nM forward/reverse primers, and cDNA reverse-transcribed from 2 μg RNAs. The temperature profile included 95°C for 10 min, 35 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 15 sec, and annealing/extension at 60°C for 1 min. Transcript expression was normalized to the expression of the control gene, arginyl-tRNA synthetase (PbArgRS, PB000094.03.0). The normalized expression was calculated as following: relative amount of Pbuis2 cDNA / relative amount of PbArgRS cDNA. Gene-specific primers were PbArgRS (sense 5’- ttggtgattggggaacac-3’, antisense 5’- cttgatataaaagggtcaaac-3’); Pbuis2 (sense 5’- actgaaaatgaacatgccttacta -3’, antisense 5’- catatgggtgagcttcttcctt-3’); Pbpp1 (sense 5’-cccgaaaaggaaataaatgg-3’, antisense 5’-ttggagccgaaaataaagtaac-3’).

Antisera

A fragment of P. berghei UIS2 (from 413 to 618 amino acids) fused at the C-terminal with GST was expressed in E. coli and was used to immunize mice. Western blot of P. berghei sporozoites lysates with the mouse antibody (1:1,000 dilution) revealed a 160 kDa band (endogenous PbUIS2 is 156 kDa). The identity of Puf2 proteins from P. berghei and P. yoelii is 95%. The Puf2 antiserum was raised in mice by immunization with the GST-fused P. yoelii Puf2 recombinant protein. The Puf2 antibody (1:1,000 dilution) recognizes a band of about 60 kDa band in western blots of P. berghei or P. yoelii sporozoites lysates. The anti-total eIF2α and anti-eIF2a-P sera were generated in William J. Sullivan Jr.’s lab [15, 16]. The Anti-eIF2a-P sera (1:500 dilution) specifically recognize Plasmodium eIF2a-P [4, 7, 23]. Anti-total eIF2α sera (1:1,000 dilution) recognizes both phosphorylated and non-phosphorylated forms of eIF2α from Toxoplasma [15] and Plasmodium [4, 7, 23].

eIF2α-P phosphatase activity in vitro

The eIF2α-P phosphatase activity was measured by two methods: (1) His-tagged PfeIF2α was incubated with GST-PfPK4 kinase domain and [γ-32P] ATP for 1 hour as described [7] and purified by Ni-NTA affinity chromatography. The [γ-32P] labeled PfeIF2α-P was then used as the phosphatase substrate as following: One μg GST or GSTPbUIS2PD was added into 100 μg [γ-32P] labeled PfeIF2α-P in the assay buffer (20mM Tris-HCl, pH7.0; 50 mM NaCl) with 5 mM MnCl2. After 1 hour incubation at 37°C, the total proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and subjected to autoradiography and coomassie blue staining. (2) Malachite green colorimetric assay: GSTPbUIS2PD in assay buffer (50mM Tris-HCl, pH7.0) was pre-incubated for 30 min in the absence or presence of MgCl2, MnCl2, CdCl2, or okadaic acid. PfeIF2α-P was added and incubated for an additional 30 min. Then, 2 volumes of malachite green reagent (0.15% malachite green, 1% ammonium molybdate and 12.5% concentrated HCl v/v) were added before reading the absorbance at 630 nm.

Pull down assay from parasite lysate

P. falciparum eIF2α coding sequence was codon-optimized and expressed with a GST fusion tag in E. coli [7]. The GST-PfeIF2a was immobilized and purified on glutathione affinity column. The lysates of P. berghei blood stage parasites were incubated with immobilized GST-PfeIF2α in the presence or absence of eIF2α phosphatase specific inhibitor Salubrinal (Sal, 50 μM), or PP1 inhibitor Guanabenz acetate (GA, 70 μM) for 2 hours. After 3 times wash with high-salt NETN buffer (300 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 0.5 mM EDTA. 0.5% (v/v) Nonidet P-40), the GST-PfeIF2α and its binding proteins were eluted with 10 mM reduced glutathione/ 50 mM Tris-HCL pH 8.0. The eluates were analyzed by immunoblots using antisera specific to PP1, UIS2, phosphorylated eIF2α, and total eIF2α.

Hepatocyte invasion assay

Ten thousand P. berghei sporozoites were added to confluent HepG2. After 60 min incubation at 37°C, the HepG2 cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and blocked with 3% BSA in PBS. To detect the parasites outside the HepG2 cells, the slide was stained with anti-CSP 3D11 Ab [39] followed by Alexa Fluor 594 goat anti-mouse IgG (Molecular Probes). Then, to detect both sporozoites outside and inside hepatocytes [40], the HepG2 cell membranes were permeabilized with 100% chilled methanol. The cells were again blocked and stained with anti-CSP 3D11 Ab followed by Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-mouse IgG as secondary Ab. Sporozoites were counted under a fluorescent microscope.

Gel shift assay

GST-tagged PbPuf2 was expressed in E. coli and purified by affinity chromatography. The biotinylated uis2-RNA was synthesized using HiScribe T7 High Yield RNA Synthesis Kit (New England Biolabs). The Puf2 protein was incubated with 5 nM biotinylated uis2-RNA in 1X REMSA buffer containing 5% glycerol. Reactions were resolved on a native 6% polyacrylamide gel in 0.5X TBE and transferred to a nylon membrane. Band shifts were detected using Thermo scientific LightShift Chemiluminescent RNA EMSA kit.

Supporting Information

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

A double cross-over knockout strategy was used to knockout Pbpp1. hDHFR, human dihydrofolate reductase. Parasites were found in the blood smear of mice 24 hours post-transfection of the linearized construct. The mice were then treated with pyrimethamine. No parasites were observed 14 days post pyrimethamine treatment. Two attempts to knockout Pbpp1 failed. Related to Fig 1.

(TIF)

(A) The targeting plasmid for generating the Pbpp1 cKO contains the 3’ end (700 bp) of the pp1 coding sequence (box CDS), a fragment including 0.6 kb of TRAP 3’ regulatory sequence (lollipop) and the hdhfr marker cassette (gray box), the plasmid backbone (thick line), and pp1 3’ regulatory sequence (500 bp, lollipop). The linearized plasmid was integrated at the cognate locus into wt TRAP/FlpL(-) NK65 parasite via double crossover recombination, generating the pp1 cKO clone. (B) Pbpp1 expression cassette is intact in Pbpp1 cKO blood stage. Swiss Webster mice (5 per group) were injected intra-peritoneally with 200 μl of blood infected with Pbpp1cKO or wt TRAP/FlpL(-) parasites (1% parasitemia). The parasitemia of the recipient mice was checked in Giemsa-stained blood smears. Since the FlpL recombinase is expressed in midgut sporozoites, Pbpp1 is only disrupted in Ssp. Related to Fig 1.

(TIF)

The primers used for integration-specific PCR analysis are indicated as arrows in S2 Fig. (A) Integration-specific PCR analysis of the uis2 loci of the wt TRAP/FlpL (-) NK65 and uis2 cKO blood stage clones. Lanes 1 and 4: primers P5+P6; lanes 2 and 5: primer P5+P2; lanes 3 and 6: primer P4+P6. (B) Pbpp1 locus is disrupted in Pbpp1 cKO Ssp. PCR amplification from gDNA of intact uis2 cKO blood stage parasites or from pp1 cKO Ssp using primers P5+P2 were performed. Control depicts PCR amplification of the eIF2α coding sequence. Related to Fig 1.

(TIF)

Sporozoite numbers were counted in three different mosquito cycles. Related to Fig 1

(TIF)

(A) Twenty thousand wild type TRAP/FlpL(-) or Pbpp1 cKO sporozoites were added to 1x105 HepG2 cells. Fourty-eight hours post infection hepatic parasites were stained with anti-PbHSP70 and anti-PbPP1. Bar, 100 μm. (B) The HSP70 stained liver stage parasites were counted. The EEF (Liver stage) numbers were indistinguishable between wild type TRAP/FlpL(-) and Pbpp1 cKO parasites. P value was calculated by t test. (C) The HSP70 stained and PP1 stained liver stage parasites were counted in Pbpp1 cKO infected HepG2 cells. The Pbpp1 disruption rate was calculated from 5 independent experiments. Related to Fig 1.

(TIF)

(A) Twenty thousand wild type TRAP/FlpL(-) or Pbpp1 cKO sporozoites were added to 1x105 HepG2 cells and grown for 6, 24, 36, 48, and 55 h. P berghei 18S rRNA copy number was measured by qPCR. Human gapdh was used as internal control. There was no significant difference between wt and Pbpp1 cKO. (B) C57BL/6 mice (6 weeks old, five mice per group) were intravenously injected with 1x104 wt TRAP/FlpL(-) or Pbpp1cKO sporozoites. Liver-stage parasite burden was measured 42 hours post infection by qPCR, and shown are the mean ± SD. Pbpp1 cKO Ssp developed normally in mice. P value was calculated by t test. Related to Fig 1.

(TIF)

(A) Infectivity of wt TRAP/FlpL(-) and Pbpp1 cKO sporozoites after intravenous injection of C57BL/6 mice. Genotype of blood stage parasites was analyzed from the Pbpp1 cKO sporozoites infected mice. The parasites were pp1 (+); therefore, the pp1 locus had not been disrupted by the recombinase FlpL. The incomplete excision in the FlpL/FRT-mediated conditional mutagenesis system was previously reported by Combe et al. [14]. (B) Genotype of blood stage parasites from the Pbpp1cKO sporozoites infected mouse performed by gDNA PCR. Lane 1, intact Pbpp1 cKO blood stage parasites; lane 2, Pbpp1 cKO Ssp; lane 3, blood stage parasites from a Pbpp1 cKO sporozoites infected mouse. Primers P5+P7 (S2 Fig) were used to verify the disruption of Pbpp1 3’UTR. Primers P5 and P2 were used to verify the intact Pbpp1 locus. Related to Fig 1.

(TIF)

The proteins from 5X105 P. berghei blood stage parasites were separated by SDS-PAGE followed by Western blot using naive mouse serum (Lane 1) and mouse anti-PbPP1 antibody (Lane 2), respectively. The mouse anti-PbPP1 antibody recognized the 35 kDa endogenous PP1 from the lysates of P. berghei blood stage parasites. Related to Fig 2.

(TIF)

(A) The N-terminus of PbUIS2 pulled down PfeIF2α-P. The PbUIS2 N-ter was fused to GST-tag at its N-terminus and His-tag at its C-terminus. After 2-step affinity purification, the E. coli expressed fusion protein (85 kDa) was immobilized on glutathione sepharose 4B. After incubation with purified recombinant PfeIF2α or PfeIF2α-P, the sepharose was washed three times with high-salt NETN buffer (300 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 0.5 mM EDTA, and 0.5% (v/v) Nonidet P-40). The retained proteins were detected by SDS-PAGE followed by coomassie brilliant blue staining. Lane 1: PbUIS2 N-ter. Lane 2: proteins retained on the glutathione sepharose 4B after the pull down assays with non-phosphorylated PfeIF2α. Lane 3: non-phosphorylated PfeIF2α input control. Lane 4: proteins retained on the glutathione sepharose 4B after the pull down assays with PfeIF2α-P. Lane 5, PfeIF2α-P control. (B) Mass spectrometry shows that the protein bound to the PbUIS2 N-ter is indeed PfeIF2α-P. The PbUIS2 N-ter pulled down protein was analyzed by mass spectrometry. Peptides denoted in green are peptides identified in our analysis. Each green line under a peptide denotes the number of times the peptide has been identified in this analysis (spectral counts). A red line below a peptide indicates that the corresponding amino acid carries a modification (in vivo or in vitro). The modification shown here are: C = Carbamidomethylation (+57 for alkylation of cysteines, that is a result of the sample preparation); M = oxidation (+16 for oxygen addition, common in gel digestion); Q, N = deamidation (+1, usually an in vitro modification enhanced by storing samples at high pH. Sample digestion was performed at pH = 8 overnight). Related to Fig 2.

(TIF)

A double cross-over knockout strategy used to attempt a knockout uis2 in P. berghei. The uis2 KO plasmid pBC_uis2KO contains a 500-bp PCR fragment from uis2 coding sequence (CDS, 800–1300 bp), GFP cassette, DHFR cassette, and a 500 bp PCR fragment from the uis2 C terminal CDS. DHFR, dihydrofolate reductase. Three independent attempts to generate Pbuis2 knock-out parasite failed.

(TIF)

(A) Schematic representations of the uis2 locus in the wild type TRAP/FlpL(-) NK65 clone and in the uis2 cKO clone. The uis2 cKO plasmid contains the 3’ end (800 bp) of the uis2 coding sequence (box CDS), a fragment including 0.6 kb of TRAP 3’ regulatory sequence (lollipop) and the hdhfr marker cassette (gray box), the plasmid backbone (thick line), and uis2 3’ regulatory sequence (770 bp, lollipop). The linearized plasmid integrated at the cognate locus into wt TRAP/FlpL(-) NK65 parasite via double crossover recombination, generating the uis2 cKO clone. The primers used for integration-specific PCR analysis are indicated as arrows. (B) Integration-specific PCR analysis of the uis2 loci of the wt TRAP/FlpL (-) NK65 and uis2 cKO clones. Lanes 1 and 4: primers P1+P3; lanes 2 and 5: primer P1+P2; lanes 3 and 6: primer P3+P4. (C) Pbuis2 locus is disrupted in Pbuis2 cKO Ssp. PCR amplification from gDNA of intact uis2 cKO blood stage parasites (lane 1) or uis2 cKO Ssp (lane 2) using Primers P1+P2. Controls are shown in lanes 3 and 4: PCR amplification of eIF2α coding sequence from uis2 cKO blood stage parasites (lane 3) and from uis2 cKO Ssp (lane 4). Related to Fig 4.

(TIF)

Sporozoite numbers were counted in three different mosquito cycles. Related to Fig 4.

(TIF)

(A) A few uis2 (+) parasites still remained from the liver stages originated from uis2 cKO Ssp. The figure represented one of them stained with anti-UIS2 and anti-UIS4 sera. Bars, 10 μm. (B) The genotype of the blood stage parasites originated by uis2 cKO sporozoites was uis2 (+). gDNA PCR amplifications were performed using primers P1 and P2 (S11 Fig) and uis2 expression cassette from intact uis2 cKO blood stage parasites (lane 1), uis2 cKO Ssp (lane 2), and the erythrocytic stages parasites from a mouse infected with uis2 cKO Ssp (lane 3). eIF2α was used as internal control. Related to Table 1.

(TIF)

Acknowledgments

We thank Sergio Schenkman and Nobuko Yoshida’s laboratories from Universidade Federal de Sao Paulo (UNIFESP) for technical support. We thank Moriya Tsuji’s laboratory from Aaron Diamond AIDS Research Center for providing laboratory facilities. We thank Leids Universitair Medisch Centrum for providing Puf2(-) parasites and William J. Sullivan Jr. from Indiana University for providing anti-eIF2α-P and anti-total eIF2α antibodies.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

BMAF is supported by National Institutes of Health R01 AI079110-03 http://projectreporter.nih.gov/project_info_description.cfm?aid=8662161&icde=25265777&ddparam=&ddvalue=&ddsub=&cr=2&csb=default&cs=ASC. VN is supported by National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases AI108592 http://projectreporter.nih.gov/project_info_description.cfm?aid=8868027&icde=25265856&ddparam=&ddvalue=&ddsub=&cr=1&csb=default&cs=ASC. VN and MZ are supported by Sao Paulo Research Foundation – FAPESP Grant number: 12/50399-4 http://bvs.fapesp.br/en/auxilios/55638/characterization-of-the-protein-phosphatase-uis2-of-plasmodium-as-a-new-tool-for-malaria-drug-develo/. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Florens L, Washburn MP, Raine JD, Anthony RM, Grainger M, Haynes JD, et al. A proteomic view of the Plasmodium falciparum life cycle. Nature. 2002;419(6906):520–6. Epub 2002/10/09. 10.1038/nature01107 nature01107 [pii]. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lasonder E, Janse CJ, van Gemert GJ, Mair GR, Vermunt AM, Douradinha BG, et al. Proteomic profiling of Plasmodium sporozoite maturation identifies new proteins essential for parasite development and infectivity. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4(10):e1000195 Epub 2008/11/01. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Le Roch KG, Zhou Y, Blair PL, Grainger M, Moch JK, Haynes JD, et al. Discovery of gene function by expression profiling of the malaria parasite life cycle. Science. 2003;301(5639):1503–8. Epub 2003/08/02. 10.1126/science.1087025 1087025 [pii]. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zhang M, Fennell C, Ranford-Cartwright L, Sakthivel R, Gueirard P, Meister S, et al. The Plasmodium eukaryotic initiation factor-2alpha kinase IK2 controls the latency of sporozoites in the mosquito salivary glands. J Exp Med. 2010;207(7):1465–74. Epub 2010/06/30. jem.20091975 [pii] 10.1084/jem.20091975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Matuschewski K, Ross J, Brown SM, Kaiser K, Nussenzweig V, Kappe SH. Infectivity-associated changes in the transcriptional repertoire of the malaria parasite sporozoite stage. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(44):41948–53. Epub 2002/08/15. 10.1074/jbc.M207315200 M207315200 [pii]. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zhang M, Joyce BR, Sullivan WJ Jr., Nussenzweig V. Translational control in Plasmodium and toxoplasma parasites. Eukaryot Cell. 2013;12(2):161–7. Epub 2012/12/18. EC.00296-12 [pii] 10.1128/EC.00296-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zhang M, Mishra S, Sakthivel R, Rojas M, Ranjan R, Sullivan WJ Jr., et al. PK4, a eukaryotic initiation factor 2alpha(eIF2alpha) kinase, is essential for the development of the erythrocytic cycle of Plasmodium. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(10):3956–61. Epub 2012/02/23. 1121567109 [pii] 10.1073/pnas.1121567109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Boyce M, Bryant KF, Jousse C, Long K, Harding HP, Scheuner D, et al. A selective inhibitor of eIF2alpha dephosphorylation protects cells from ER stress. Science. 2005;307(5711):935–9. Epub 2005/02/12. 307/5711/935 [pii] 10.1126/science.1101902 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Harding HP, Zhang Y, Scheuner D, Chen JJ, Kaufman RJ, Ron D. Ppp1r15 gene knockout reveals an essential role for translation initiation factor 2 alpha (eIF2alpha) dephosphorylation in mammalian development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(6):1832–7. Epub 2009/02/03. 0809632106 [pii] 10.1073/pnas.0809632106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hendrickx A, Beullens M, Ceulemans H, Den Abt T, Van Eynde A, Nicolaescu E, et al. Docking motif-guided mapping of the interactome of protein phosphatase-1. Chem Biol. 2009;16(4):365–71. Epub 2009/04/25. S1074-5521(09)00079-9 [pii] 10.1016/j.chembiol.2009.02.012 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lammers T, Lavi S. Role of type 2C protein phosphatases in growth regulation and in cellular stress signaling. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2007;42(6):437–61. Epub 2007/12/11. 788273801 [pii] 10.1080/10409230701693342 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kumar R, Adams B, Oldenburg A, Musiyenko A, Barik S. Characterisation and expression of a PP1 serine/threonine protein phosphatase (PfPP1) from the malaria parasite, Plasmodium falciparum: demonstration of its essential role using RNA interference. Malar J. 2002;1:5 Epub 2002/06/12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Guttery DS, Poulin B, Ramaprasad A, Wall RJ, Ferguson DJ, Brady D, et al. Genome-wide Functional Analysis of Plasmodium Protein Phosphatases Reveals Key Regulators of Parasite Development and Differentiation. Cell Host Microbe. 2014;16(1):128–40. Epub 2014/07/11. S1931-3128(14)00219-4 [pii] 10.1016/j.chom.2014.05.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Combe A, Giovannini D, Carvalho TG, Spath S, Boisson B, Loussert C, et al. Clonal conditional mutagenesis in malaria parasites. Cell Host Microbe. 2009;5(4):386–96. Epub 2009/04/22. S1931-3128(09)00099-7 [pii] 10.1016/j.chom.2009.03.008 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sullivan WJ Jr., Narasimhan J, Bhatti MM, Wek RC. Parasite-specific eIF2 (eukaryotic initiation factor-2) kinase required for stress-induced translation control. Biochem J. 2004;380(Pt 2):523–31. Epub 2004/03/03. 10.1042/BJ20040262 BJ20040262 [pii]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Narasimhan J, Joyce BR, Naguleswaran A, Smith AT, Livingston MR, Dixon SE, et al. Translation regulation by eukaryotic initiation factor-2 kinases in the development of latent cysts in Toxoplasma gondii. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(24):16591–601. Epub 2008/04/19. M800681200 [pii] 10.1074/jbc.M800681200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Aly ASI, Lindner SE, MacKellar DC, Peng XX, Kappe SHI. SAP1 is a critical post-transcriptional regulator of infectivity in malaria parasite sporozoite stages. Mol Microbiol. 2011;79(4):929–39. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07497.x ISI:000287094300009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tsaytler P, Harding HP, Ron D, Bertolotti A. Selective inhibition of a regulatory subunit of protein phosphatase 1 restores proteostasis. Science. 2011;332(6025):91–4. Epub 2011/03/10. science.1201396 [pii] 10.1126/science.1201396 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pan C, Liu HD, Gong Z, Yu X, Hou XB, Xie DD, et al. Cadmium is a potent inhibitor of PPM phosphatases and targets the M1 binding site. Sci Rep. 2013;3:2333 Epub 2013/08/02. srep02333 [pii] 10.1038/srep02333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Pan C, Tang JY, Xu YF, Xiao P, Liu HD, Wang HA, et al. The catalytic role of the M2 metal ion in PP2Calpha. Sci Rep. 2015;5:8560 Epub 2015/02/25. srep08560 [pii] 10.1038/srep08560 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Shi Y. Serine/threonine phosphatases: mechanism through structure. Cell. 2009;139(3):468–84. Epub 2009/11/03. S0092-8674(09)01254-9 [pii] 10.1016/j.cell.2009.10.006 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mikolajczak SA, Silva-Rivera H, Peng X, Tarun AS, Camargo N, Jacobs-Lorena V, et al. Distinct malaria parasite sporozoites reveal transcriptional changes that cause differential tissue infection competence in the mosquito vector and mammalian host. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28(20):6196–207. Epub 2008/08/20. MCB.00553-08 [pii] 10.1128/MCB.00553-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lindner SE, Mikolajczak SA, Vaughan AM, Moon W, Joyce BR, Sullivan WJ Jr., et al. Perturbations of Plasmodium Puf2 expression and RNA-seq of Puf2-deficient sporozoites reveal a critical role in maintaining RNA homeostasis and parasite transmissibility. Cell Microbiol. 2013;15(7):1266–83. Epub 2013/01/30. 10.1111/cmi.12116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tarun AS, Peng X, Dumpit RF, Ogata Y, Silva-Rivera H, Camargo N, et al. A combined transcriptome and proteome survey of malaria parasite liver stages. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(1):305–10. Epub 2008/01/04. 0710780104 [pii] 10.1073/pnas.0710780104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wharton RP, Sonoda J, Lee T, Patterson M, Murata Y. The Pumilio RNA-binding domain is also a translational regulator. Mol Cell. 1998;1(6):863–72. Epub 1998/07/14. S1097-2765(00)80085-4 [pii]. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cui L, Fan Q, Li J. The malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum encodes members of the Puf RNA-binding protein family with conserved RNA binding activity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30(21):4607–17. Epub 2002/11/01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Miao J, Li J, Fan Q, Li X, Cui L. The Puf-family RNA-binding protein PfPuf2 regulates sexual development and sex differentiation in the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. J Cell Sci. 2010;123(Pt 7):1039–49. Epub 2010/03/04. jcs.059824 [pii] 10.1242/jcs.059824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gomes-Santos CS, Braks J, Prudencio M, Carret C, Gomes AR, Pain A, et al. Transition of Plasmodium sporozoites into liver stage-like forms is regulated by the RNA binding protein Pumilio. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7(5):e1002046 Epub 2011/06/01. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002046 PPATHOGENS-D-10-00436 [pii]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Muller K, Matuschewski K, Silvie O. The Puf-family RNA-binding protein Puf2 controls sporozoite conversion to liver stages in the malaria parasite. PLoS One. 2011;6(5):e19860 Epub 2011/06/16. 10.1371/journal.pone.0019860 PONE-D-11-02456 [pii]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Barford D. Molecular mechanisms of the protein serine/threonine phosphatases. Trends Biochem Sci. 1996;21(11):407–12. Epub 1996/11/01. S0968-0004(96)10060-8 [pii]. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Cohen PT. Protein phosphatase 1—targeted in many directions. J Cell Sci. 2002;115(Pt 2):241–56. Epub 2002/02/13. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ward P, Equinet L, Packer J, Doerig C. Protein kinases of the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum: the kinome of a divergent eukaryote. BMC Genomics. 2004;5:79 Epub 2004/10/14. 1471-2164-5-79 [pii] 10.1186/1471-2164-5-79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wilkes JM, Doerig C. The protein-phosphatome of the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. BMC Genomics. 2008;9:412 Epub 2008/09/17. 1471-2164-9-412 [pii] 10.1186/1471-2164-9-412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Rojas M, Gingras AC, Dever TE. Protein phosphatase PP1/GLC7 interaction domain in yeast eIF2gamma bypasses targeting subunit requirement for eIF2alpha dephosphorylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(14):E1344–53. Epub 2014/04/08. 1400129111 [pii] 10.1073/pnas.1400129111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Konrad C, Queener SF, Wek RC, Sullivan WJ Jr. Inhibitors of eIF2alpha dephosphorylation slow replication and stabilize latency in Toxoplasma gondii. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57(4):1815–22. Epub 2013/02/06. AAC.01899-12 [pii] 10.1128/AAC.01899-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hahn CK, Lowrey CH. Eukaryotic initiation factor 2alpha phosphorylation mediates fetal hemoglobin induction through a post-transcriptional mechanism. Blood. 2013;122(4):477–85. Epub 2013/05/22. blood-2013-03-491043 [pii] 10.1182/blood-2013-03-491043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kaiser K, Camargo N, Kappe SH. Transformation of sporozoites into early exoerythrocytic malaria parasites does not require host cells. J Exp Med. 2003;197(8):1045–50. Epub 2003/04/23. 10.1084/jem.20022100 jem.20022100 [pii]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wang Q, Brown S, Roos DS, Nussenzweig V, Bhanot P. Transcriptome of axenic liver stages of Plasmodium yoelii. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2004;137(1):161–8. Epub 2004/07/29. 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2004.06.001 S0166685104001689 [pii]. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Yoshida N, Nussenzweig RS, Potocnjak P, Nussenzweig V, Aikawa M. Hybridoma produces protective antibodies directed against the sporozoite stage of malaria parasite. Science. 1980;207(4426):71–3. Epub 1980/01/04. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kumar KA, Garcia CR, Chandran VR, Van Rooijen N, Zhou Y, Winzeler E, et al. Exposure of Plasmodium sporozoites to the intracellular concentration of potassium enhances infectivity and reduces cell passage activity. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2007;156(1):32–40. Epub 2007/08/24. S0166-6851(07)00207-1 [pii] 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2007.07.004 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

A double cross-over knockout strategy was used to knockout Pbpp1. hDHFR, human dihydrofolate reductase. Parasites were found in the blood smear of mice 24 hours post-transfection of the linearized construct. The mice were then treated with pyrimethamine. No parasites were observed 14 days post pyrimethamine treatment. Two attempts to knockout Pbpp1 failed. Related to Fig 1.

(TIF)

(A) The targeting plasmid for generating the Pbpp1 cKO contains the 3’ end (700 bp) of the pp1 coding sequence (box CDS), a fragment including 0.6 kb of TRAP 3’ regulatory sequence (lollipop) and the hdhfr marker cassette (gray box), the plasmid backbone (thick line), and pp1 3’ regulatory sequence (500 bp, lollipop). The linearized plasmid was integrated at the cognate locus into wt TRAP/FlpL(-) NK65 parasite via double crossover recombination, generating the pp1 cKO clone. (B) Pbpp1 expression cassette is intact in Pbpp1 cKO blood stage. Swiss Webster mice (5 per group) were injected intra-peritoneally with 200 μl of blood infected with Pbpp1cKO or wt TRAP/FlpL(-) parasites (1% parasitemia). The parasitemia of the recipient mice was checked in Giemsa-stained blood smears. Since the FlpL recombinase is expressed in midgut sporozoites, Pbpp1 is only disrupted in Ssp. Related to Fig 1.

(TIF)

The primers used for integration-specific PCR analysis are indicated as arrows in S2 Fig. (A) Integration-specific PCR analysis of the uis2 loci of the wt TRAP/FlpL (-) NK65 and uis2 cKO blood stage clones. Lanes 1 and 4: primers P5+P6; lanes 2 and 5: primer P5+P2; lanes 3 and 6: primer P4+P6. (B) Pbpp1 locus is disrupted in Pbpp1 cKO Ssp. PCR amplification from gDNA of intact uis2 cKO blood stage parasites or from pp1 cKO Ssp using primers P5+P2 were performed. Control depicts PCR amplification of the eIF2α coding sequence. Related to Fig 1.

(TIF)

Sporozoite numbers were counted in three different mosquito cycles. Related to Fig 1

(TIF)

(A) Twenty thousand wild type TRAP/FlpL(-) or Pbpp1 cKO sporozoites were added to 1x105 HepG2 cells. Fourty-eight hours post infection hepatic parasites were stained with anti-PbHSP70 and anti-PbPP1. Bar, 100 μm. (B) The HSP70 stained liver stage parasites were counted. The EEF (Liver stage) numbers were indistinguishable between wild type TRAP/FlpL(-) and Pbpp1 cKO parasites. P value was calculated by t test. (C) The HSP70 stained and PP1 stained liver stage parasites were counted in Pbpp1 cKO infected HepG2 cells. The Pbpp1 disruption rate was calculated from 5 independent experiments. Related to Fig 1.

(TIF)

(A) Twenty thousand wild type TRAP/FlpL(-) or Pbpp1 cKO sporozoites were added to 1x105 HepG2 cells and grown for 6, 24, 36, 48, and 55 h. P berghei 18S rRNA copy number was measured by qPCR. Human gapdh was used as internal control. There was no significant difference between wt and Pbpp1 cKO. (B) C57BL/6 mice (6 weeks old, five mice per group) were intravenously injected with 1x104 wt TRAP/FlpL(-) or Pbpp1cKO sporozoites. Liver-stage parasite burden was measured 42 hours post infection by qPCR, and shown are the mean ± SD. Pbpp1 cKO Ssp developed normally in mice. P value was calculated by t test. Related to Fig 1.

(TIF)

(A) Infectivity of wt TRAP/FlpL(-) and Pbpp1 cKO sporozoites after intravenous injection of C57BL/6 mice. Genotype of blood stage parasites was analyzed from the Pbpp1 cKO sporozoites infected mice. The parasites were pp1 (+); therefore, the pp1 locus had not been disrupted by the recombinase FlpL. The incomplete excision in the FlpL/FRT-mediated conditional mutagenesis system was previously reported by Combe et al. [14]. (B) Genotype of blood stage parasites from the Pbpp1cKO sporozoites infected mouse performed by gDNA PCR. Lane 1, intact Pbpp1 cKO blood stage parasites; lane 2, Pbpp1 cKO Ssp; lane 3, blood stage parasites from a Pbpp1 cKO sporozoites infected mouse. Primers P5+P7 (S2 Fig) were used to verify the disruption of Pbpp1 3’UTR. Primers P5 and P2 were used to verify the intact Pbpp1 locus. Related to Fig 1.

(TIF)

The proteins from 5X105 P. berghei blood stage parasites were separated by SDS-PAGE followed by Western blot using naive mouse serum (Lane 1) and mouse anti-PbPP1 antibody (Lane 2), respectively. The mouse anti-PbPP1 antibody recognized the 35 kDa endogenous PP1 from the lysates of P. berghei blood stage parasites. Related to Fig 2.

(TIF)

(A) The N-terminus of PbUIS2 pulled down PfeIF2α-P. The PbUIS2 N-ter was fused to GST-tag at its N-terminus and His-tag at its C-terminus. After 2-step affinity purification, the E. coli expressed fusion protein (85 kDa) was immobilized on glutathione sepharose 4B. After incubation with purified recombinant PfeIF2α or PfeIF2α-P, the sepharose was washed three times with high-salt NETN buffer (300 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 0.5 mM EDTA, and 0.5% (v/v) Nonidet P-40). The retained proteins were detected by SDS-PAGE followed by coomassie brilliant blue staining. Lane 1: PbUIS2 N-ter. Lane 2: proteins retained on the glutathione sepharose 4B after the pull down assays with non-phosphorylated PfeIF2α. Lane 3: non-phosphorylated PfeIF2α input control. Lane 4: proteins retained on the glutathione sepharose 4B after the pull down assays with PfeIF2α-P. Lane 5, PfeIF2α-P control. (B) Mass spectrometry shows that the protein bound to the PbUIS2 N-ter is indeed PfeIF2α-P. The PbUIS2 N-ter pulled down protein was analyzed by mass spectrometry. Peptides denoted in green are peptides identified in our analysis. Each green line under a peptide denotes the number of times the peptide has been identified in this analysis (spectral counts). A red line below a peptide indicates that the corresponding amino acid carries a modification (in vivo or in vitro). The modification shown here are: C = Carbamidomethylation (+57 for alkylation of cysteines, that is a result of the sample preparation); M = oxidation (+16 for oxygen addition, common in gel digestion); Q, N = deamidation (+1, usually an in vitro modification enhanced by storing samples at high pH. Sample digestion was performed at pH = 8 overnight). Related to Fig 2.

(TIF)

A double cross-over knockout strategy used to attempt a knockout uis2 in P. berghei. The uis2 KO plasmid pBC_uis2KO contains a 500-bp PCR fragment from uis2 coding sequence (CDS, 800–1300 bp), GFP cassette, DHFR cassette, and a 500 bp PCR fragment from the uis2 C terminal CDS. DHFR, dihydrofolate reductase. Three independent attempts to generate Pbuis2 knock-out parasite failed.

(TIF)

(A) Schematic representations of the uis2 locus in the wild type TRAP/FlpL(-) NK65 clone and in the uis2 cKO clone. The uis2 cKO plasmid contains the 3’ end (800 bp) of the uis2 coding sequence (box CDS), a fragment including 0.6 kb of TRAP 3’ regulatory sequence (lollipop) and the hdhfr marker cassette (gray box), the plasmid backbone (thick line), and uis2 3’ regulatory sequence (770 bp, lollipop). The linearized plasmid integrated at the cognate locus into wt TRAP/FlpL(-) NK65 parasite via double crossover recombination, generating the uis2 cKO clone. The primers used for integration-specific PCR analysis are indicated as arrows. (B) Integration-specific PCR analysis of the uis2 loci of the wt TRAP/FlpL (-) NK65 and uis2 cKO clones. Lanes 1 and 4: primers P1+P3; lanes 2 and 5: primer P1+P2; lanes 3 and 6: primer P3+P4. (C) Pbuis2 locus is disrupted in Pbuis2 cKO Ssp. PCR amplification from gDNA of intact uis2 cKO blood stage parasites (lane 1) or uis2 cKO Ssp (lane 2) using Primers P1+P2. Controls are shown in lanes 3 and 4: PCR amplification of eIF2α coding sequence from uis2 cKO blood stage parasites (lane 3) and from uis2 cKO Ssp (lane 4). Related to Fig 4.

(TIF)

Sporozoite numbers were counted in three different mosquito cycles. Related to Fig 4.

(TIF)

(A) A few uis2 (+) parasites still remained from the liver stages originated from uis2 cKO Ssp. The figure represented one of them stained with anti-UIS2 and anti-UIS4 sera. Bars, 10 μm. (B) The genotype of the blood stage parasites originated by uis2 cKO sporozoites was uis2 (+). gDNA PCR amplifications were performed using primers P1 and P2 (S11 Fig) and uis2 expression cassette from intact uis2 cKO blood stage parasites (lane 1), uis2 cKO Ssp (lane 2), and the erythrocytic stages parasites from a mouse infected with uis2 cKO Ssp (lane 3). eIF2α was used as internal control. Related to Table 1.

(TIF)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.