Abstract

Stem cell therapy is considered a potential regenerative strategy for patients with neurologic deficits. Studies involving animal models of ischemic stroke have shown that stem cells transplanted into the brain can lead to functional improvement. With current advances in the understanding regarding the effects of introducing stem cells and their mechanisms of action, several clinical trials of stem cell therapy have been conducted in patients with stroke since 2005, including studies using mesenchymal stem cells, bone marrow mononuclear cells, and neural stem/progenitor cells. In addition, several clinical trials of the use of adult stem cells to treat ischemic stroke are ongoing. This review presents the status of our understanding of adult stem cells and results from clinical trials, and introduces ongoing clinical studies of adult stem cell therapy in the field of stroke.

Keywords: stroke, clinical trials, stem cells

INTRODUCTION

Stroke is one of the leading causes of death and physical disability among adults, with one-quarter to half of stroke survivors being left with complete or partial dependence on others. Stem cell therapy is an emerging paradigm in the field of stroke treatment, and is considered a potential regenerative strategy for patients with neurologic deficits. Studies involving animal models of ischemic stroke have shown that stem cells transplanted into the brain can lead to functional improvement.1 Various cell types have been used to improve function and the recovery after stroke, including embryonic stem cells (ESCs), immortalized pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), neural stem/progenitor cells (NSCs), and nonneuronal adult stem cells such as mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) and bone marrow mononuclear cells (MNCs). Most clinical trials involving patients with stroke have used adult stem cells, such as MSCs, MNCs, and NSCs. The International Cellular Medicine Society classifies culture-expanded autologous MSCs as a clinical cell line, unlike ESCs, iPSCs, and genetically modified stem cells. MSCs can migrate to injured brain regions (tropism) and self-renew, reportedly without inducing carcinogenesis. Sufficient numbers of MSCs can be easily obtained within several weeks of culture expansion.

This review presents the status of the current understanding regarding adult stem cells and the results from clinical trials. The most recent advances in preclinical studies are discussed, and ongoing clinical studies of adult stem cell therapy in the field of stroke are described.

MECHANISMS UNDERLYING STEM CELL ACTION IN STROKE RECOVERY

Stem cells aid stroke recovery via various mechanisms of action depending on the specific cell type used. Transplanted ESCs, iPSCs, and NSCs can replace the missing brain cells in the infarcted area, while nonneuronal adult stem cells, such as MSCs and MNCs, provide trophic support to enhance self-repair systems such as endogenous neurogenesis. Most preclinical studies of stem cell therapy for stroke have emphasized the need to enhance self-repair systems rather than to replace lost cells, regardless of the type of cells used (MSC1 and iPSC2). A recent study found that although iPSC-derived NSCs induced neurogenesis, they enhanced endogenous neurogenesis via trophic support, in a manner similar to adult nonneuronal stem cells (e.g., MSCs), rather than by cell replacement with exogenous iPSC-derived NSCs.2 In addition, there are hurdles associated with using cell replacement to restore neuronal function after stroke. True neuronal substitution requires specific anatomic and functional profiles, such as the need for biode-gradable scaffolds (longitudinal channel-like structures for axonal connections) and topologic transplantation of different types of stem-cell-derived neurons (cortical neurons, interneurons, and oligodendrocytes).3

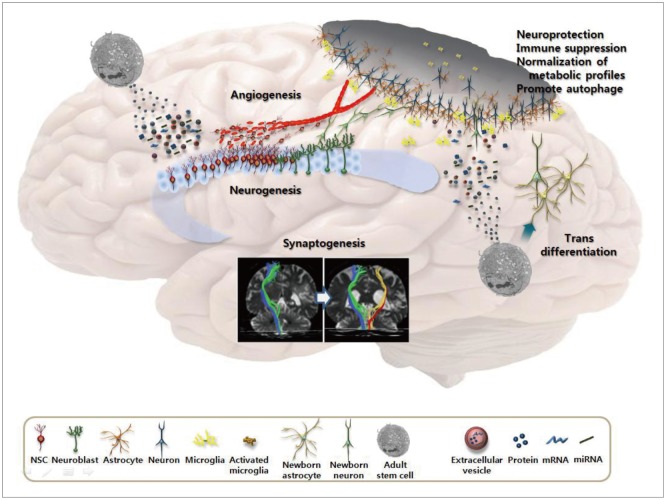

The above-described features mean that adult stem cells such as MSCs may be a good choice for stroke therapy because they secrete a variety of bioactive substances-including trophic factors-into the injured brain, which may be associated with enhanced neurogenesis, angiogenesis, and synaptogenesis.4,5,6,7 Besides trophic factors, MSCs release extra-cellular vesicles to deliver functional proteins and microRNAs to NSCs or neuronal cells.8 In addition, MSCs exert their actions by attenuating inflammation,9,10 reducting scar thickness (which may interfere with the recovery process),11 enhancing autophagy,12 and normalizing microenvironmental/metabolic profiles13 in various brain diseases. Preclinical studies have found that most injected stem cells disappear within a few weeks, which makes it unlikely that the transplanted stem cells were functionally integrated into the brain.14,15 However, it was also reported that subpopulations of MSCs (e.g., multilineage differentiating stress-enduring cells) were able to differentiate into neuronal cells, and were integrated into the peri-infarcted cortex and acted as tissue repair cells.16 Thus, MSCs are thought to play multiple roles (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Mechanisms of action of mesenchymal stem cells in stroke recovery.

CLINICAL TRIALS OF STEM CELL THERAPY IN PATIENTS WITH STROKE

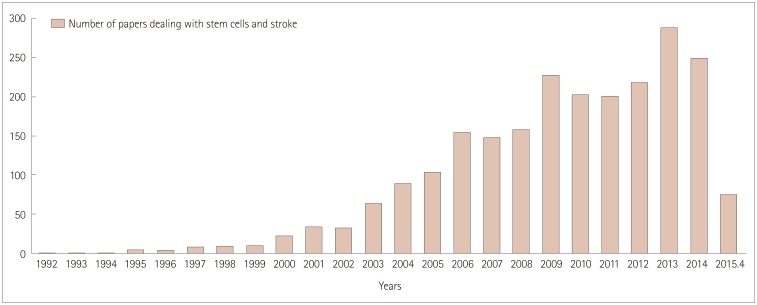

The number of studies of stem cells in stroke has increased markedly recently (Fig. 2). With current advances in the understanding of the effects of introducing stem cells and their mechanisms of action, several clinical trials of stem cell therapy have been conducted in patients with stroke since 2005, including studies using MSCs,17,18,19,20 MNCs,21,22,23,24,25,26 and NSCs (Table 1).27,28

Fig. 2. Number of papers on stem cells and stroke.

Table 1. Clinical trials of stem cells in patients with stroke.

| Ref. | Study design control:cell group | Characteristics of stroke | Manipulation (cell dose) | Route | Efficacy | Adverse effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Autologous bone marrow mononuclear cells | ||||||

| 21 | None:5 patients | Chronic | Isolation using normal saline | IC | N/A | None |

| 1-year f/u | Ischemic or ICH | |||||

| 22 | None:6 patients | Subacute | Isolation using human albumin-containing normal saline (0.6-5×108) | IA | N/A | Seizure after 200 days |

| 6-month f/u | MCA infarct | |||||

| 23 | None:10 patients | Acute | Isolation using human albumin-containing normal saline (0.6-5×108) | IV | Limited study design | None |

| 6-month f/u | Large MCA infarct | |||||

| 24 | None:20 patients | Acute | Isolation using human albumin-containing normal saline (0.6-5×108) | IA | Limited study design | None |

| 6-month f/u | Nonlacunar infarct | |||||

| 25 | 40:60 patients | Acute | Isolation using normal saline (1.33×1013) | IC | NIHSS and BI improved | None |

| 6-month f/u | ICH | |||||

| 26 | 60:60 patients | Subacute | Isolation using normal saline (2.8×108) | IV | BI and mRS at day 180 | Similar in the two groups |

| MCA/ACA infarct | ||||||

| Autologous bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells | ||||||

| 17 | 25:5 patients | Subacute | Ex vivo culture expansion using fetal bovine serum (1×108) | IV | BI improved at 3 months | None |

| 1-year f/u | Large MCA infarct | |||||

| 18 | 36:16 patients | Subacute | Ex vivo culture expansion using fetal bovine serum (1×108) | IV | mRS 0-3, increased in MSC group | None |

| 5-year f/u | Large MCA infarct | |||||

| 19 | None:12 patients | Subacute to chronic | Ex vivo culture expansion using autologous serum (1×108) | IV | Limited study design | None |

| 1-year f/u | Variable | |||||

| 20 | 6:6 patients | Chronic | Ex vivo culture expansion using serum-free media (5-6×107) | IV | Modest increase in FM and mBI | None |

| 24-week f/u | Ischemic or ICH | |||||

| Allogeneic neural stem/progenitor cells | ||||||

| 27 | None:5 patients | Chronic | Ex vivo culture expansion of NSCs obtained from primordial porcine striatum | IC | Limited study design | Seizure, aggravation of hemiplegia |

| Terminated early | MCA infarct affecting striatum | |||||

| 28 | None:8 patients | Subacute to chronic MCA/ACA infarct | Ex vivo culture expansion of NSCs obtained from fetal brain | IC | Limited study design | Transient low-grade fever only |

| 2-year f/u | ||||||

ACA: anterior cerebral artery, BI: Barthel index, FM: Fugl-Meyer score, f/u: follow-up, IA: intra-arterial, IC: intracerebral, ICH: intracerebral hemorrhage, IV: intravenous, mBI: modified Barthel index, MCA: middle cerebral artery, mRS: modified Rankin Score, MSC: mesenchymal stem cell, N/A: not available, NIHSS: national Institutes of Health Stroke Scale, NSCs: neural stem/progenitor cells.

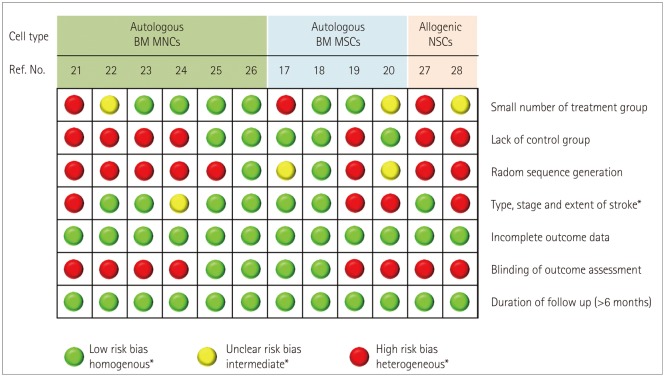

For stem cell therapy to be useful in augmenting the recovery after stroke, it needs to be safe and effective, applicable to a broad spectrum of patients with stroke, and cost-effective.29 Most clinical trials using various types of stem cell have demonstrated that stem cell therapy following stroke is both feasible and safe, and may improve recovery. However, these trials varied in terms of the patient characteristics, cell therapy timing, dose and type of cells delivered, and mode of treatment. In addition, many factors that could be critical to the transplantation success, including the location and the extent of lesions, were not adequately considered. Moreover, the assessments of functional improvement, adverse effects, and pretreatment screening tests for safety have varied greatly among the studies. None of the studies aimed to determine the efficacy of MSC therapy in patients with stroke. All of the studies aimed to assess the feasibility and safety of stem cell treatments, and most were small series and did not include a control group. While stem cells appeared to be of some benefit in several studies, there was significant bias in subsequent studies (Fig. 3). A recent multicenter randomized controlled clinical trial (RCT) of intravenous infusion of autologous bone marrow MNCs failed to show any effectiveness.26

Fig. 3. Summary table for the risk of bias from different items for each clinical trial of stem cells in patients with stroke. BM: bone marrow, MNCs: mononuclear cells, MSCs: mesenchymal stem cells, NSCs: neural stem/progenitor cells.

Presently, rigorous reasoning is required to replicate experimental results in patients with stroke. The Stem cell Therapies as an Emerging Paradigm in Stroke (STEPs) committee recently suggested guidelines for bridging the gap between basic and clinical studies,30 early stage clinical trials,31 and phase II/III trials32 of stem cell therapies in stroke. According to these recommendations, studies should be RCTs. After randomization, experimental procedures may not be blinded, because applying stereotaxic sham surgery or bone marrow sham aspiration to control patients may increase the risk of adverse effects. Patient selection and a cell dose that is equivalent to that used in animal studies should be used. Patients with stroke in the middle cerebral artery territory (or anterior circulation) and those with moderately severe neurologic disabilities could be ideal candidates. The mode of application of stem cells may significantly influence the number of cells delivered to target regions, as well as the incidence of adverse effects. For example, one study demonstrated that intra-arterial transplantations resulted in superior delivery of stem cells in the ischemic brain compared to intravenous infusions,33 but this may cause arterial occlusion, resulting in stroke.33,34 There have been relatively few studies directly comparing the efficacy of intravenous and intra-arterial delivery of MSCs.35 The mode of treatment should be based on the severity and location of lesions, and the timing of application. In addition to the clinical outcomes measured, laboratory and neuroimaging findings should be used as surrogate markers of efficacy. Advanced technologies such as multimodal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI; e.g., resting-state functional MRI or diffusion-tensor imaging) can be used to monitor the response to restorative therapy.36,37 Finally, patients should be followed for more than 90 days. Long-term monitoring (>6 months) is likely to be unnecessary because autologous MSCs are a clinical cell line and die within days or weeks of administration.31

ONGOING CLINICAL TRIALS

Among the various adult stem cells, MSCs have been most commonly used in the clinical trials for patients with stroke. There have been several recent efforts to improve the effects of MSC therapy. For example, MSCs can be isolated from various tissues, such as umbilical cord, endometrial polyps, menses blood, adipose tissue, and bone marrow.38 While a long culture period is required to obtain sufficient stem cells from the patient's own bone marrow, allogeneic MSC therapy can form the basis of 'off-the-shelf' products. In addition, MSCs are heterogeneous with respect to their developmental potential and trophic supports. The use of functionally distinct subpopulations of MSCs was found to improve their effects.39 Finally, presenting appropriate stimuli to cells may promote a transient adaptive response (preconditioning) so that injury resulting from subsequent exposure to a harmful stimulus is reduced. Anoxic preconditioning of stem cells has been tested for the promotion of cell survival after transplantation in ischemic disease conditions.40,41

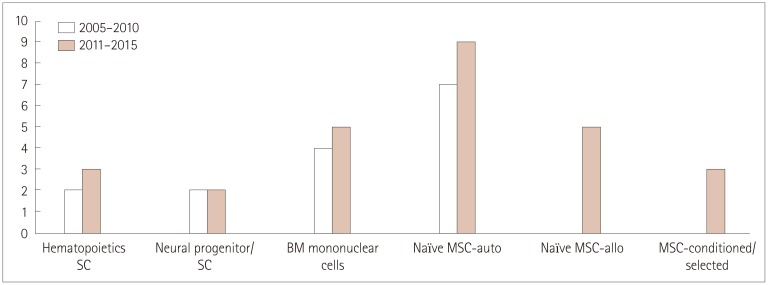

It is interesting that earlier clinical trials (i.e., performed during 2005-2010) used autologous naïve MSCs, whereas several recent trials performed since 2011 have examined allogeneic or manipulated MSCs, including by isolating functional subpopulations or the preconditioning of stem cells (Fig. 4). At the time of writing, we were aware of at least 15 active clinical trials using adult stem cells to treat ischemic stroke (http://clinicaltrials.gov) (Supplementary Table 1 in the online-only Data Supplement). It should be noted that seven of these trials were RCTs that aimed to determine the efficacy of MSC therapy, five tested the efficacy and safety of allogeneic MSCs in patients with stroke, and four studies used manipulated (conditioned or selected) MSCs. In the STem cell Application Research and Trials In NeuroloGy-2 (STARTING-2) trial, we are incorporating ischemic preconditioning using ischemic serum, blood-brain-barrier manipulation, and strict selection of candidates in order to improve the therapeutic effects and safety of MSCs.42

Fig. 4. Number and types of stem cells in clinical trials for patients with stroke. allo: allogeneic, auto: autologous, BM: bone marrow, MSCs: mesenchymal stem cells, SC: stem cell.

CONCLUSIONS

It is too early to conclude whether MSC therapy can improve functional outcomes in patients with stroke. A recent meta-analysis in the field of cardiology concluded that transplanting adult bone marrow cells improved left ventricular function, infarct size, and remodeling in patients with ischemic heart disease compared with standard therapies. This conclusion was reached after analyzing data from 50 studies (involving 2,625 patients), in which patients received echocardiographic evaluations and long-term follow-up.43 In the field of hematology, a developmental history of 60 years was required to develop the first successful stem cell therapy- the transplantation of hematopoietic stem cells. This suggests that development of a dramatically new therapy will require patience and constant dialogue between basic scientists and the physicians performing the clinical trials.44 More evidence from RCTs is needed. Further advances at both the bench and bedside would advance the understanding of the basic mechanisms underlying stem cell therapy as well as improve the therapeutic efficacy and safety of applying stem cells to patients with stroke.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Eun Hee Kim, Samsung Biomedical Research Institute, for their advice and assistance in preparing the manuscript.

This study was supported by the Korea Health Technology R&D Project, the Ministry of Health & Welfare (HI14C16240000).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The author has no financial conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Materials

The online-only Data Supplement is available with this article at http://dx.doi.org/10.3988/jcn.2016.12.1.14.

Ongoing clinical trials of stem cell therapy in adult patients with stroke

References

- 1.Chopp M, Li Y. Treatment of neural injury with marrow stromal cells. Lancet Neurol. 2002;1:92–100. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(02)00040-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chang DJ, Lee N, Park IH, Choi C, Jeon I, Kwon J, et al. Therapeutic potential of human induced pluripotent stem cells in experimental stroke. Cell Transplant. 2013;22:1427–1440. doi: 10.3727/096368912X657314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dihné M, Hartung HP, Seitz RJ. Restoring neuronal function after stroke by cell replacement: anatomic and functional considerations. Stroke. 2011;42:2342–2350. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.613422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen X, Li Y, Wang L, Katakowski M, Zhang L, Chen J, et al. Ischemic rat brain extracts induce human marrow stromal cell growth factor production. Neuropathology. 2002;22:275–279. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1789.2002.00450.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li WY, Choi YJ, Lee PH, Huh K, Kang YM, Kim HS, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells for ischemic stroke: changes in effects after ex vivo culturing. Cell Transplant. 2008;17:1045–1059. doi: 10.3727/096368908786991551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu Z, Li Y, Zhang RL, Cui Y, Chopp M. Bone marrow stromal cells promote skilled motor recovery and enhance contralesional axonal connections after ischemic stroke in adult mice. Stroke. 2011;42:740–744. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.607226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Song M, Mohamad O, Gu X, Wei L, Yu SP. Restoration of intracortical and thalamocortical circuits after transplantation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells into the ischemic brain of mice. Cell Transplant. 2013;22:2001–2015. doi: 10.3727/096368912X657909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lai RC, Chen TS, Lim SK. Mesenchymal stem cell exosome: a novel stem cell-based therapy for cardiovascular disease. Regen Med. 2011;6:481–492. doi: 10.2217/rme.11.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee ST, Chu K, Jung KH, Kim SJ, Kim DH, Kang KM, et al. Anti-inflammatory mechanism of intravascular neural stem cell transplantation in haemorrhagic stroke. Brain. 2008;131(Pt 3):616–629. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim YJ, Park HJ, Lee G, Bang OY, Ahn YH, Joe E, et al. Neuroprotective effects of human mesenchymal stem cells on dopaminergic neurons through anti-inflammatory action. Glia. 2009;57:13–23. doi: 10.1002/glia.20731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shen LH, Li Y, Chen J, Zacharek A, Gao Q, Kapke A, et al. Therapeutic benefit of bone marrow stromal cells administered 1 month after stroke. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2007;27:6–13. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shin JY, Park HJ, Kim HN, Oh SH, Bae JS, Ha HJ, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells enhance autophagy and increase β-amyloid clearance in Alzheimer disease models. Autophagy. 2014;10:32–44. doi: 10.4161/auto.26508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paik MJ, Li WY, Ahn YH, Lee PH, Choi S, Kim KR, et al. The free fatty acid metabolome in cerebral ischemia following human mesenchymal stem cell transplantation in rats. Clin Chim Acta. 2009;402:25–30. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2008.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Borlongan CV, Hadman M, Sanberg CD, Sanberg PR. Central nervous system entry of peripherally injected umbilical cord blood cells is not required for neuroprotection in stroke. Stroke. 2004;35:2385–2389. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000141680.49960.d7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosenblum S, Wang N, Smith TN, Pendharkar AV, Chua JY, Birk H, et al. Timing of intra-arterial neural stem cell transplantation after hypoxia-ischemia influences cell engraftment, survival, and differentiation. Stroke. 2012;43:1624–1631. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.637884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yamauchi T, Kuroda Y, Morita T, Shichinohe H, Houkin K, Dezawa M, et al. Therapeutic effects of human multilineage-differentiating stress enduring (MUSE) cell transplantation into infarct brain of mice. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0116009. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bang OY, Lee JS, Lee PH, Lee G. Autologous mesenchymal stem cell transplantation in stroke patients. Ann Neurol. 2005;57:874–882. doi: 10.1002/ana.20501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee JS, Hong JM, Moon GJ, Lee PH, Ahn YH, Bang OY, STARTING collaborators A long-term follow-up study of intravenous autologous mesenchymal stem cell transplantation in patients with ischemic stroke. Stem Cells. 2010;28:1099–1106. doi: 10.1002/stem.430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Honmou O, Houkin K, Matsunaga T, Niitsu Y, Ishiai S, Onodera R, et al. Intravenous administration of auto serum-expanded autologous mesenchymal stem cells in stroke. Brain. 2011;134(Pt 6):1790–1807. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bhasin A, Srivastava MV, Kumaran SS, Mohanty S, Bhatia R, Bose S, et al. Autologous mesenchymal stem cells in chronic stroke. Cerebrovasc Dis Extra. 2011;1:93–104. doi: 10.1159/000333381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Suárez-Monteagudo C, Hernández-Ramírez P, Alvarez-González L, García-Maeso I, de la Cuétara-Bernal K, Castillo-Díaz L, et al. Autologous bone marrow stem cell neurotransplantation in stroke patients. An open study. Restor Neurol Neurosci. 2009;27:151–161. doi: 10.3233/RNN-2009-0483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Battistella V, de Freitas GR, da Fonseca LM, Mercante D, Gutfilen B, Goldenberg RC, et al. Safety of autologous bone marrow mononuclear cell transplantation in patients with nonacute ischemic stroke. Regen Med. 2011;6:45–52. doi: 10.2217/rme.10.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Savitz SI, Misra V, Kasam M, Juneja H, Cox CS, Jr, Alderman S, et al. Intravenous autologous bone marrow mononuclear cells for ischemic stroke. Ann Neurol. 2011;70:59–69. doi: 10.1002/ana.22458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Friedrich MA, Martins MP, Araújo MD, Klamt C, Vedolin L, Garicochea B, et al. Intra-arterial infusion of autologous bone marrow mononuclear cells in patients with moderate to severe middle cerebral artery acute ischemic stroke. Cell Transplant. 2012;21(Suppl 1):S13–S21. doi: 10.3727/096368912x612512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li ZM, Zhang ZT, Guo CJ, Geng FY, Qiang F, Wang LX. Autologous bone marrow mononuclear cell implantation for intracerebral hemorrhage-a prospective clinical observation. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2013;115:72–76. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2012.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Prasad K, Sharma A, Garg A, Mohanty S, Bhatnagar S, Johri S, et al. Intravenous autologous bone marrow mononuclear stem cell therapy for ischemic stroke: a multicentric, randomized trial. Stroke. 2014;45:3618–3624. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.007028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Savitz SI, Dinsmore J, Wu J, Henderson GV, Stieg P, Caplan LR. Neurotransplantation of fetal porcine cells in patients with basal ganglia infarcts: a preliminary safety and feasibility study. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2005;20:101–107. doi: 10.1159/000086518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Qiao LY, Huang FJ, Zhao M, Xie JH, Shi J, Wang J, et al. A two-year follow-up study of cotransplantation with neural stem/progenitor cells and mesenchymal stromal cells in ischemic stroke patients. Cell Transplant. 2014;23(Suppl 1):S65–S72. doi: 10.3727/096368914X684961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adams HP, Jr, Nudo RJ. Management of patients with stroke: is it time to expand treatment options? Ann Neurol. 2013;74:4–10. doi: 10.1002/ana.23948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stem Cell Therapies as an Emerging Paradigm in Stroke Participants. Stem Cell Therapies as an Emerging Paradigm in Stroke (STEPS): bridging basic and clinical science for cellular and neurogenic factor therapy in treating stroke. Stroke. 2009;40:510–515. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.526863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Savitz SI, Chopp M, Deans R, Carmichael T, Phinney D, Wechsler L STEPS Participants. Stem Cell Therapy as an Emerging Paradigm for Stroke (STEPS) II. Stroke. 2011;42:825–829. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.601914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Savitz SI, Cramer SC, Wechsler L STEPS 3 Consortium. Stem cells as an emerging paradigm in stroke 3: enhancing the development of clinical trials. Stroke. 2014;45:634–639. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.003379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pendharkar AV, Chua JY, Andres RH, Wang N, Gaeta X, Wang H, et al. Biodistribution of neural stem cells after intravascular therapy for hypoxic-ischemia. Stroke. 2010;41:2064–2070. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.575993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang B, Migliati E, Parsha K, Schaar K, Xi X, Aronowski J, et al. Intra-arterial delivery is not superior to intravenous delivery of autologous bone marrow mononuclear cells in acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2013;44:3463–3472. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.000821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eckert MA, Vu Q, Xie K, Yu J, Liao W, Cramer SC, et al. Evidence for high translational potential of mesenchymal stromal cell therapy to improve recovery from ischemic stroke. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2013;33:1322–1334. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2013.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thiel A, Vahdat S. Structural and resting-state brain connectivity of motor networks after stroke. Stroke. 2015;46:296–301. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.006307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Burke Quinlan E, Dodakian L, See J, McKenzie A, Le V, Wojnowicz M, et al. Neural function, injury, and stroke subtype predict treatment gains after stroke. Ann Neurol. 2015;77:132–145. doi: 10.1002/ana.24309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ding DC, Shyu WC, Lin SZ. Mesenchymal stem cells. Cell Transplant. 2011;20:5–14. doi: 10.3727/096368910X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bakondi B, Shimada IS, Perry A, Munoz JR, Ylostalo J, Howard AB, et al. CD133 identifies a human bone marrow stem/progenitor cell sub-population with a repertoire of secreted factors that protect against stroke. Mol Ther. 2009;17:1938–1947. doi: 10.1038/mt.2009.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang JA, He A, Hu X, Jiang Y, Sun Y, Jiang J, et al. Anoxic preconditioning: a way to enhance the cardioprotection of mesenchymal stem cells. Int J Cardiol. 2009;133:410–412. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2007.11.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tang YL, Zhu W, Cheng M, Chen L, Zhang J, Sun T, et al. Hypoxic preconditioning enhances the benefit of cardiac progenitor cell therapy for treatment of myocardial infarction by inducing CXCR4 expression. Circ Res. 2009;104:1209–1216. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.197723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kim SJ, Moon GJ, Chang WH, Kim YH, Bang OY STARTING-2 (STem cell Application Researches and Trials In NeuroloGy-2) collaborators. Intravenous transplantation of mesenchymal stem cells preconditioned with early phase stroke serum: current evidence and study protocol for a randomized trial. Trials. 2013;14:317. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-14-317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jeevanantham V, Butler M, Saad A, Abdel-Latif A, Zuba-Surma EK, Dawn B. Adult bone marrow cell therapy improves survival and induces long-term improvement in cardiac parameters: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Circulation. 2012;126:551–568. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.086074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Prockop DJ, Prockop SE, Bertoncello I. Are clinical trials with mesenchymal stem/progenitor cells too far ahead of the science? Lessons from experimental hematology. Stem Cells. 2014;32:3055–3061. doi: 10.1002/stem.1806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Ongoing clinical trials of stem cell therapy in adult patients with stroke