Abstract

Since the discovery of the hypocretins/orexins, a series of observations have indicated that these peptides influence a variety of physiological processes including feeding, sleep/wake function, memory, and stress. More recently, the hypocretins have been implicated in reinforcement and reward-related processes via actions on the mesolimbic dopamine system. Although investigation into the relationship between the hypocretins and reinforcement/reward remains in relatively early stages, accumulating evidence suggests that continued research into this area may offer new insights into the addiction process and provide the foundation to generate novel pharmacotherapies for drug abuse. The current chapter will focus on contemporary perspectives of hypocretin regulation of cocaine reward and reinforcement via actions on the mesolimbic dopamine system.

Keywords: hypocretin, orexin, cocaine, addiction, self-administration, nucleus accumbens, conditioned place preference, dopamine, voltammetry, microdialysis

I. Introduction

Hypocretin peptide and receptors

The hypocretins (also termed orexins) were discovered in 1998 by two independent research groups (de Lecea et al., 1998; Sakurai et al., 1998), and consist of the hypocretin-1 and hypocretin-2 peptides which are also known as orexin A and B. These peptides are synthesized solely within a restricted portion of the lateral and posterior hypothalamus and perifornical areas (Chemelli et al., 1999; Date et al., 1999; de Lecea et al., 1998; Peyron et al., 1998; Sakurai et al., 1998). While the hypocretin neurons are confined to a relatively circumscribed region, immunohistochemical studies demonstrate widespread projections of these neurons throughout the brain, suggesting varied actions of these peptides (Date et al., 1999; Nambu et al., 1999; Peyron et al., 1998; van Den Pol, 1999).

To date, two G-protein-coupled hypocretin receptor subtypes have been identified. The hypocretin 1 receptor preferentially binds the hypocretin-1 peptide, whereas the hypocretin 2 receptor binds both hypocretin-1 and -2 peptides with equi-affinity (Sakurai et al., 1998). Both the hypocretin 1 and 2 receptors are expressed widely throughout the brain with slight, yet sometimes notable variations in distribution (Backberg et al., 2002; Bourgin et al., 2000; Cluderay et al., 2002; Greco and Shiromani, 2001; Hervieu et al., 2001; Marcus et al., 2001; Suzuki et al., 2002; Trivedi et al., 1998). For example, hypocretin 1 receptors are observed throughout the cortex, hippocampus, paraventricular thalamic, ventromedial hypothalamic and arcuate nuclei, as well as the dorsal raphe, locus coeruleus, substantia nigra (SN) and ventral tegmental area (VTA). In contrast, hypocretin 2 receptors are observed in the cortex, septal nuclei, hippocampus, medial thalamic groups, the dorsal and median raphe nuclei, tuberomamillary nucleus, dorsomedial and paraventricular hypothalamic nuclei, SN and VTA (Backberg et al., 2002; Bourgin et al., 2000; Cluderay et al., 2002; Greco and Shiromani, 2001; Hervieu et al., 2001; Marcus et al., 2001; Suzuki et al., 2002; Trivedi et al., 1998).

Although extensive evidence demonstrates that the lateral hypothalamus receives inputs from much of the central nervous system, only few advances have been made in elucidating the afferent inputs to the hypocretin neurons. Nevertheless, these studies have proven to be valuable at demonstrating that hypocretin neuronal activity is likely influenced by a diverse set of functionally distinct neural structures. For example, studies using classic retrograde and anterograde tracing methods, as well as more novel molecular techniques, demonstrate that hypocretin neurons are innervated by monoaminergic regions such as the dorsal raphe, VTA, and locus coeruleus (Abrahamson et al., 2001; Fadel and Deutch, 2002; Horvath et al., 1999; Sakurai et al., 2005; Yoshida et al., 2006). Although it is generally unclear as to whether these inputs exert excitatory or inhibitory actions, it is evident that hypocretin neurons receive signals from regions that govern motivation, homeostatic drive, behavioral state, and autonomic tone, and thus the hypocretin neurons are poised to regulate a variety of neural functions.

Hypocretin regulates arousal and arousal-related behavioral activity

Despite initial connections between hypocretins and feeding, substantial research now suggests that the hypocretin system plays a critical role in the regulation of arousal, including processes involved in governing sleep and waking. For example, hypocretin neurons are preferentially active during periods of alert waking, novelty, and behavioral arousal, and are responsive to wake-promoting drugs (España et al., 2003; Estabrooke et al., 2001; Lee et al., 2005; Mileykovskiy et al., 2005). Further, hypocretin-immunoreactive fibers and hypocretin receptors are located within many arousal-related structures including the noradrenergic, serotonergic, histaminergic, and dopaminergic systems (Brown et al., 2001; Fadel and Deutch, 2002; Hagan et al., 1999; Horvath et al., 1999). Consistent with this, hypocretin levels fluctuate across the day/night cycle with the highest levels observed during the dark-phase when rats are typically awake (Yoshida et al., 2001). Further, intracerebroventricular (i.c.v.) infusions of hypocretin-1 or hypocretin-2 dose-dependently increase waking and suppress sleep (España et al., 2001; España et al., 2002; Hagan et al., 1999; Ida et al., 1999; Piper et al., 2000) and elicit behaviors typical of spontaneous waking and/or high arousal conditions, including those associated with motivated states. Similar wake-promoting and behavioral-activating effects are also observed when hypocretin-1 is focally delivered to the VTA, locus coeruleus, basal forebrain, and other arousal-related regions (Bourgin et al., 2000; España et al., 2001; Hagan et al., 1999; Vittoz and Berridge, 2006).

Additional evidence for hypocretin involvement in arousal processes comes from clinical and animal studies indicating an important link between dysregulation of hypocretin neurotransmission and the sleep/arousal disorder narcolepsy. Numerous studies using people with narcolepsy have demonstrated that these patients have reduced circulating levels of hypocretin in their cerebrospinal fluid and commonly display a degenerative loss of hypocretin neurons (Blouin et al., 2005; Crocker et al., 2005; Nishino et al., 2000; Peyron et al., 2000; Ripley et al., 2001; Thannickal et al., 2000). Additionally, researchers have detected a genetic defect in the hypocretin 2 receptor gene in a longstanding dog model of narcolepsy (Lin et al., 1999). Like people with narcolepsy, these dogs experience symptoms of excessive daytime sleepiness and cataplexy. Finally, in a mouse model of narcolepsy, hypocretin ligand and hypocretin receptor knockout (KO) mice, as well as transgenic mice with a degenerative loss of hypocretin neurons, also display a phenotype similar to that of human narcolepsy (Chemelli et al., 1999; Hara et al., 2001; Kisanuki et al., 2000). Interestingly, hypocretin ligand KO mice have also been shown to display deficits in reward/reinforcement processes as well as dopamine signaling indicating reduced responsivity to drugs of abuse (see below). This is particularly notable given that people with narcolepsy rarely develop addiction, despite treatment with pychostimulant drugs such as amphetamine (Akimoto et al., 1960; Hayduk et al., 1995; Rogers et al., 1997; Rogers et al., 2001).

Summary

Both basic and clinical research indicates that the hypocretins participate in the regulation of arousal and arousal-related processes via a widespread projection system that acts upon multiple terminal fields. Given that arousal is a critical factor in the accurate expression of all motivated behaviors, these observations have important implications for potential involvement of hypocretin systems on a broad constellation of physiological functions including those associated with drug reward and reinforcement.

II. Hypocretin regulation of reward and reinforcement processes

An amassing literature indicates that the hypocretin system participates in reward processes and motivated behaviors associated with cocaine. Some of the first evidence to support this emerged from anatomical studies showing prominent hypocretin projections to reward-related brain structures including the VTA and nucleus accumbens (Fadel and Deutch, 2002; Peyron et al., 1998). Additional work also demonstrated that dopamine neurons of the VTA contain both hypocretin 1 and hypocretin 2 receptors and that hypocretins exert excitatory actions on these neurons (Borgland et al., 2006; Korotkova et al., 2003; see below). Given these observations, it is not surprising that multiple reports have focused on the extent to which the hypocretin system influences behavioral and dopamine responses to cocaine and other drugs of abuse.

Drugs of abuse recruit the activity of hypocretin neurons

In a series of studies from multiple research groups, it was demonstrated that experience with drugs of abuse results in the activation of hypocretin-producing neurons. For example, acute injections of methamphetamine or nicotine (Ko et al., 2003; Pasumarthi et al., 2006) increased Fos immunoreactivity in hypocretin neurons to over 300% of vehicle-treatment levels. Additionally, chronic nicotine produced an increase of hypocretin mRNA levels, as well as mRNA levels of both hypocretin 1 and 2 receptors (Kane et al., 2000). Discontinuation of chronic drug delivery and subsequent withdrawal can also elicit activation of hypocretin neurons. Indeed, naloxone-induced withdrawal from chronic morphine treatment increases Fos levels of hypocretin peptide mRNA in hypocretin neurons and also increases Fos in the NAc shell (Georgescu et al., 2003; Sharf et al., 2008; Zhou et al., 2006). Interestingly, it appears that hypocretin 1 receptors are important in these actions given that the hypocretin 1 receptor antagonist, SB-334867, reduces the effects of morphine withdrawal on Fos levels in the NAc shell and attenuates symptoms of morphine withdrawal (Sharf et al., 2008). In addition hypocretin neurons show increased Fos when animals are exposed to cues that once predicted ethanol availability (Dayas et al., 2008).

Conditioned place preference

The previous observations suggest that administration of various drugs of abuse appears to engage hypocretin neuronal activity, however, it is possible that the increases in Fos observed with these drugs may be associated with generalized enhancement of arousal, and not with more direct actions on reward mechanisms. Despite this possibility, two studies suggest that this may not be the case for conditioned place preference (CPP) for cocaine or morphine. In those studies, Harris and colleagues demonstrate that the increases in Fos are observed only in animals that developed CPP for morphine or cocaine but not in those that were treated with drug, yet failed to acquire CPP (Harris and Aston-Jones, 2006; Harris et al., 2005). Thus, rats that acquired cocaine or morphine CPP had 3-fold greater numbers of Fos-positive hypocretin neurons than naïve animals. Animals that were treated with these drugs but did not acquire CPP showed levels of Fos comparable to naïve rats. Interestingly, the degree of Fos activation was also shown to be proportional to the magnitude of CPP induced by chemical activation of hypocretin neurons, further suggesting that the activity of these neurons is associated with the rewarding aspects of these drugs. Consistent with these observations, hypocretin signaling has also been shown to be necessary for reinstatement of CPP. For example, in animals that had been extinguished of morphine CPP behavior, activation of hypocretin neurons or hypocretin-1 injections into the VTA reinstated CPP (Harris et al., 2005).

The importance of hypocretin 1 receptors in reward processes is again highlighted in a series of CPP experiments using SB-334867. Systemic pretreatment with SB-334867 blocks CPP for morphine (Harris et al., 2005) as well as CPP for amphetamine (Hutcheson et al., 2011). Additionally, infusions of SB-334967 into the VTA block morphine CPP (Narita et al., 2006; Sharf et al., 2010), as do unilateral lesions of the lateral hypothalamus combined with contralateral SB-33467 infusions into the VTA (Harris et al., 2007). Surprisingly, while systemic administration of SB-334867 is capable of blocking CPP for morphine (Harris et al., 2005; Sharf et al., 2010) it does not appear to affect CPP for cocaine (Sharf et al., 2010).

As mentioned above, people with narcolepsy, and presumably reduced hypocretin signaling, rarely develop addiction. In this light, it is noteworthy that mice lacking hypocretin peptides show multiple deficits in their responsivity to drugs of abuse. For example, hypocretin KO mice have been shown to be less susceptible than wild-types (WT) in developing morphine dependence (Georgescu et al., 2003), they display reduced locomotor and dopamine responses to morphine, and they do not develop CPP for morphine (Narita et al., 2006; Sharf et al., 2010). Recently, we have shown that hypocretin KO mice are also less sensitive to the rewarding properties of cocaine as these mice fail to exhibit CPP for cocaine (España and Jones, 2010). In those studies, and consistent with an extensive literature, WT mice exhibited robust CPP for cocaine, however, hypocretin KO mice showed a non-significant trend toward conditioned place aversion. When taken together, these observations suggest that hypocretin signaling is important for CPP behavior associated with cocaine and other drugs and thus normal levels of hypocretins may be a critical participant in regulating the rewarding properties of drugs of abuse.

Self-Administration

Multiple paradigms are used to examine drug-seeking and drug-taking in rodents, however, intravenous (i.v.) self-administration of drugs is generally accepted as the gold standard for modeling drug abuse. These techniques can be used to model different aspects of drug taking, including the acquisition and maintenance phases of drug intake as well as the propensity to relapse by measuring reinstatement of operant drug seeking behavior following a period of forced abstinence. Additionally, researchers often vary the schedules of reinforcement to examine specific aspects of cocaine intake, including drug consumption, diurnal variations in cocaine intake, and the motivation to work for cocaine. The section that follows will provide a summary of recent observations indicating a prominent role for the hypocretin system in self-administration of cocaine and other drugs of abuse.

Reinstatement

Reinstatement of drug seeking behavior is a useful method to assess the persistence of lever pressing when the drug is no longer available. Rats are typically trained to self-administer drugs until stable levels of responding are reached and rats are subsequently exposed to extinction sessions. During extinction, rats quickly learn that drug is no longer available and consequently they cease responding on the lever. Once lever responding is extinguished, rats are presented with a cue associated with cocaine intake, or alternatively, they are exposed to a stressor (e.g., foot shock), which leads to reinstatement of drug seeking.

Several observations indicate that hypocretin signaling is crucial for normal reinstatement of drug seeking. For example, i.c.v. infusions of the hypocretin-1 peptide are sufficient to reinstate cocaine and nicotine seeking (Boutrel et al., 2005; Plaza-Zabala et al., 2010). Consistent with this, SB-334967 reduces cue-induced reinstatement of ethanol and cocaine seeking (Lawrence et al., 2006; Smith et al., 2009) and reinstatement of cocaine-seeking following foot shock and yohimbine-induced stress (Boutrel et al., 2005; Richards et al., 2008). Interestingly, cocaine-primed reinstatement is not attenuated with SB-334867 treatment (Smith et al., 2009), although the mechanisms underlying this difference are not clear. When considered together, these observations indicate that the motivation to seek drug after extinction can be influenced by hypocretin signaling, depending on the parameters used to elicit drug seeking.

Maintenance

The involvement of hypocretins in regulating the reinforcing actions of drugs have been investigated across a battery of self-administration schedules of reinforcement and results have shown varied effects depending on the paradigms used. Initial, observations examining the extent to which the hypocretin system influences ongoing cocaine self-administration suggested that blocking hypocretin signaling had no effect on the maintenance of cocaine intake. In these studies, rats were implanted with a catheter into the right jugular vein and were trained to self-administer cocaine on a fixed ratio 1 (FR1) schedule of reinforcement in which a single lever press resulted in delivery of a relatively large dose of cocaine (Aston-Jones et al., 2009; España et al., 2010). Under these conditions, rats are able to attain preferred blood levels of cocaine with little effort and thus rats can readily maintain those levels throughout a session. Consequently, responding on an FR1 schedule provides information about an animal’s preferred level of cocaine consumption. After reaching stable patterns of cocaine intake, rats were pretreated with either vehicle or SB-334867 and cocaine intake was measured. As previously described (Aston-Jones et al., 2009; España et al., 2010), treatment with SB-334867 had no effect on cocaine consumption. A similar lack of effect on an FR1 schedule was also observed when rats were infused with the hypocretin-1 peptide directly into the lateral ventricles (Boutrel et al., 2005; España et al., 2011). Although these data suggested that active cocaine self-administration was not affected by hypocretin signaling, subsequent findings using different schedules of reinforcement with varying availability levels or effort requirements demonstrated significant effects of hypocretin manipulations on self-administration of cocaine and other drugs of abuse.

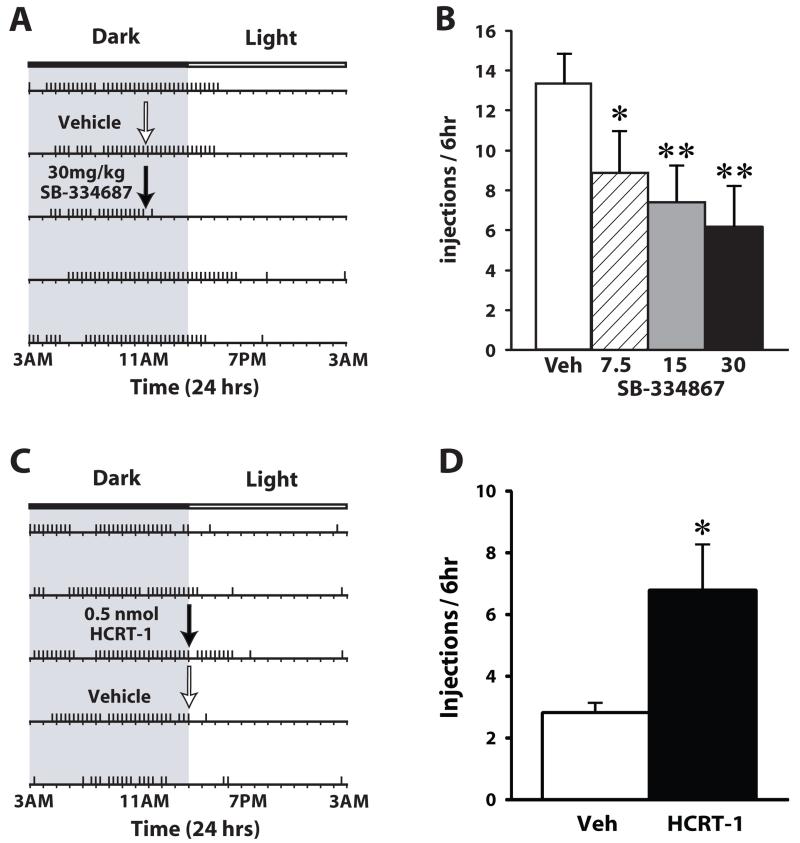

In a series of studies, we tested the effects of hypocretin manipulations across a battery of self-administration schedules. Using a 24 hr access, discrete trials (DT) schedule of reinforcement, rats were kept from maximizing their blood levels of cocaine by restricting cocaine access to three trials per hour. This degree of cocaine access engenders a characteristic pattern of intake in which animals engage in cocaine intake almost exclusively during the dark-phase (Roberts et al., 2002). Although, the effort requirement is low in a DT paradigm (one lever response results in cocaine delivery), the complex interaction between dose and availability makes this schedule more susceptible to pharmacological and physiological influences than schedules with less restricted access. As shown in figure 1, injections of SB-334867 produce a marked reduction of cocaine intake that occurred within 20 minutes of SB-334867 treatment, particularly in rats treated with the highest dose of SB-334867 (España et al., 2010). In contrast, i.c.v. infusions of hypocretin-1 increased cocaine intake, thereby extending periods of cocaine intake (España et al., 2011). These effects of hypocretin manipulations are similar to other drugs that selectively reduce intake under DT, but not FR1 schedules (Brebner et al., 2000; Smith et al., 2004).

Figure 1. Hypocretin signaling regulates cocaine self-administration on a DT schedule of reinforcement.

(A) Shown is a response pattern from an individual rat that received an i.p. vehicle (white arrow) or 30 mg/kg SB-334867 injection (black arrow). Horizontal rasters represent 24 hr periods. Vertical tick marks represent trials in which a 1.5 mg/kg cocaine injection was taken. (B) Shown are the mean ± SEM number of cocaine injections taken over the 6-hr period following i.p. injections of vehicle (n=8) or SB-334867 (7.5, 15 and 30 mg/kg; n=8). (C) Shown is a response pattern from an individual rat that received a vehicle (white arrow) or 0.5 nmol hypocretin-1 infusion (black arrow) into the lateral ventricle. (D) Shown are the mean ± SEM number of cocaine injections taken over the 6 hr period following infusion of vehicle (n=7) or 0.5 nmol hypocretin-1 (n=7). Note that for SB-334867 experiments, rats were treated at 11:00 am when rats are typically awake, whereas for hypocretin-1 experiments, rats were treated at 3:00 pm a time when rats typically discontinue taking cocaine. * P<0.05, ** P<0.01 relative to baseline.

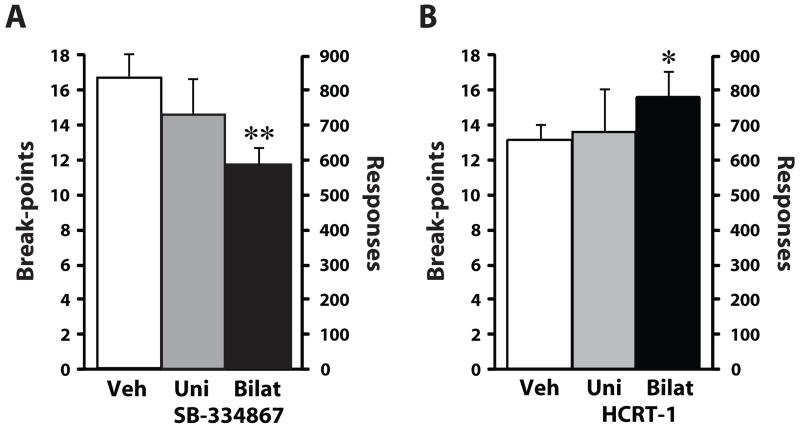

The progressive ratio (PR) schedule of reinforcement is designed to assess an animal’s motivation to work for a reinforcer and provides information on changes in the reinforcing efficacy of drugs. During the early portions of a PR session, single cocaine injections are obtained with relatively low effort (few lever responses), however, as the session continues, the lever response requirement increases and thus rats must exert progressively greater effort to obtain a single cocaine injection. Using the PR schedule, we demonstrated that both i.p. and bilateral intra-VTA injections of SB-334867 reduced the motivation for an animal to work for cocaine. Specifically, animals treated with SB-334867 engaged in significantly less lever pressing and reached lower breakpoints (fewer cocaine injections) than animals treated with vehicle (Fig. 2A). These effects are similar to recent reports showing that a 10 mg/kg i.p. dose of SB-334867 reduces PR responding for cocaine, as well as nicotine and heroin (Borgland et al., 2009; Hollander et al., 2008; Smith and Aston-Jones, 2010). Consistent with these findings, enhancement of hypocretin signaling produces the opposite effect. Thus, as shown in figure 2B, bilateral infusions of the hypocretin-1 peptide directly into the VTA, elicit an increase in breakpoints and the number of lever responses, further indicating the importance of hypocretin signaling in cocaine reinforcement (España et al., 2011).

Figure 2. Hypocretin signaling within the VTA regulates cocaine self-administration on a PR schedule of reinforcement.

(A) Shown are the mean ± SEM number of cocaine breakpoints and lever responses following unilateral or bilateral intra-VTA infusions of vehicle (unilateral, n=5; bilateral, n=6) or 10 nmol SB-334867 (uni, n=5; bilat, n=6). (B) Shown are the mean ± SEM number of cocaine breakpoints and lever responses following unilateral or bilateral intra-VTA infusions of vehicle (uni, n=5; bilat, n=6) or 0.5 nmol hypocretin-1 (unilateral, n=5; bilateral, n=6) * P<0.05, ** P<0.01 relative to baseline.

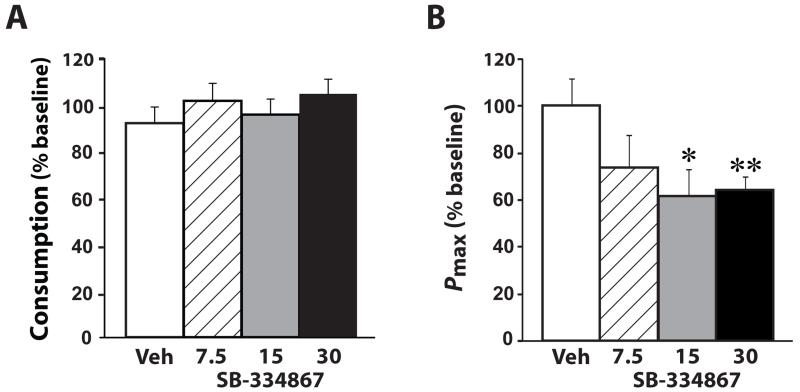

Another self-administration procedure, termed the threshold schedule of reinforcement, has been used to examine both consumption and motivation within a single session (España et al., 2010). In this procedure, lever responses during the early portion of the session result in high doses of cocaine, similar to that observed with an FR1 schedule. During this portion of the session, rats can readily titrate to preferred blood levels of cocaine, and thus it is not surprising that SB-334867 has no effect on cocaine intake under these conditions (Fig. 3A). However, as the dose of cocaine is lowered across the session, rats are required to respond more frequently to maintain blood levels of cocaine. This is reminiscent of a PR schedule in which increasingly greater numbers of responses are required to obtain the same amount of drug. At this higher price of cocaine, injections of SB-334867 decrease responding earlier in the session, at ‘threshold’ doses that are sufficient to maintain self-administration in vehicle-treated rats (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3. SB-334867 reduces responding as the unit price of cocaine is increased.

(A) Shown are the mean ± SEM percent baseline consumption of cocaine following i.p. injection of vehicle (n=9) or SB-334867 (7.5, 15 or 30 mg/kg n=9) on the threshold schedule of reinforcement. (B) Shown are the mean ± SEM Pmax values, expressed as a percentage of baseline, following i.p. injections of vehicle or SB-334867. The maximal unit price, Pmax, is defined as the point at which maximal responding occurs before an animal discontinues taking cocaine and is a measure of the behavioral economic index of price. * P<0.05, ** P<0.01 relative to vehicle.

Summary

Combined, the described self-administration studies indicate that hypocretin neurotransmission is necessary to support cocaine self-administration under schedules of reinforcement that require high-effort or where titrating to preferred blood levels of cocaine is restricted. Furthermore, given that intra-VTA SB-334867 and i.p. SB-334867 reduced cocaine intake to a similar extent, these observations provide strong support for the hypothesis that hypocretin influences cocaine reinforcement, via actions within the VTA.

III. Hypocretin regulation of dopamine release and uptake

A series of studies using behavioral, genetic, electrophysiological, and neurochemical techniques have expanded our understanding of hypocretin involvement in arousal, particularly as it relates to the regulation of motivated behavior, reward/reinforcement processes, and the neural mechanisms underlying these actions. These studies have shown convincingly that enhancement of hypocretin neurotransmission promotes behavioral and neurochemical responses to drugs of abuse, while manipulations that disrupt hypocretin signaling attenuate these responses. Given that the focus of the present review involves hypocretin regulation of dopamine function and motivated behaviors reliant on dopamine signaling, it is helpful to briefly review the importance of the mesolimbic dopamine system in the regulation of reward and reinforcement processes associated with cocaine.

Dopamine involvement in reward and reinforcement mechanisms

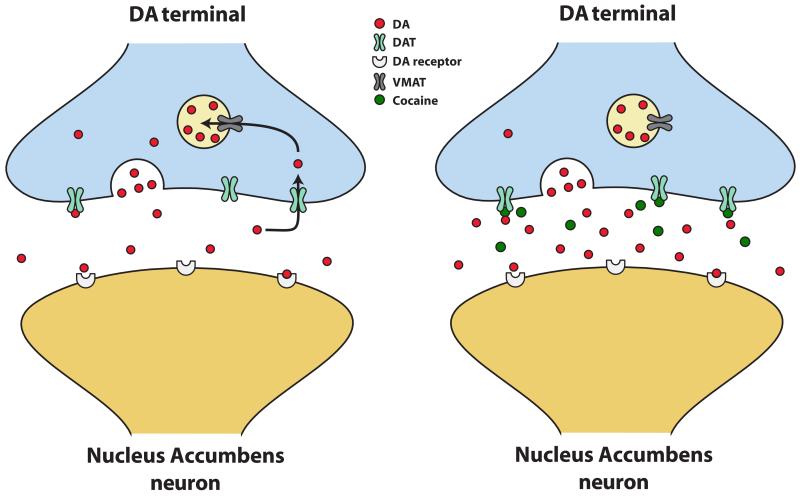

An extensive literature has demonstrated the importance of the mesolimbic projections from the VTA to the ventral striatum in reward and reinforcement processes associated with cocaine and other drugs of abuse (Koob and Le Moal, 1997; Wise, 1996; Woolverton and Johnson, 1992). Cocaine inhibits re-uptake of dopamine into the presynaptic terminal by blocking the dopamine transporter (DAT) and through these actions increases extracellular levels of dopamine and activation of pre- and post-synaptic dopamine receptors in VTA target regions (Fig. 4). It is generally believed that this enhancement of dopamine is involved in cocaine’s rewarding and reinforcing effects.

Figure 4. Effects of cocaine at the dopamine transporter.

(Left) Under normal conditions, dopamine (DA) neuron firing results in dopamine-filled vesicles to fuse with the presynaptic membrane and subsequently release into the synaptic cleft. Once in the synapse dopamine can bind to post-synaptic dopamine receptors and then is removed from extracellular space by the dopamine transporter (DAT). Once dopamine is back inside the presynaptic terminal, it is repackaged into synaptic vesicles for future release via the vesicular monoamine transporter (VMAT). (Right) Cocaine increases extracellular levels of dopamine by interacting with the DAT and thereby inhibiting dopamine uptake back into the terminal. As dopamine uptake is reduced, levels accumulate in the synapse and dopamine has a greater opportunity to bind to dopamine receptors.

Pharmacological manipulations were among the first to suggest that enhanced dopamine signaling produced rewarding/reinforcing effects while attenuation of dopamine signaling leads to reduced reinforced behavior. For instance, various dopamine agonists produce CPP (Hoffman and Beninger, 1988; Hoffman and Beninger, 1989; Hoffman et al., 1988; Papp, 1988; Parker, 1992; White et al., 1991), are readily self-administered (Caine et al., 1999; Self et al., 1996; Self and Stein, 1992; Weed and Woolverton, 1995), and have cocaine-like discriminative stimulus effects (Sinnott et al., 1999; Sinnott and Nader, 2001; Spealman et al., 1991). In contrast, dopamine antagonists can produce conditioned place aversion, (Acquas and Di Chiara, 1994; Cervo and Samanin, 1995; Funada and Shippenberg, 1996; Hoffman and Beninger, 1988; Hoffman and Beninger, 1989; Shippenberg et al., 1991; Shippenberg and Herz, 1987; White et al., 1991), and attenuate cocaine self-administration (Caine and Koob, 1994).

Among the multiple limbic structures involved in dopamine regulation of reward and reinforcement, the NAc stands out as critical participant in psychostimulant self-administration. The vast majority of addictive drugs increase extracellular dopamine in the NAc (Carboni et al., 1989; Di Chiara and Imperato, 1988; Imperato and Di Chiara, 1986) and NAc neurons display discrete discharge activity in response to cocaine-reinforced responding during self-administration (Carelli et al., 1993; Uzwiak et al., 1997). Additionally, lesions and pharmacological suppression of dopamine signaling within the NAc indicate that cocaine self-administration requires an intact NAc (Lyness et al., 1979; McGregor and Roberts, 1995; Roberts et al., 1977). These observations, amongst many others, support the hypothesis that the mesolimbic dopamine system, including the connection from the VTA to the NAc, is an essential participant in the reinforcing and behavioral effects of cocaine.

Hypocretin neurotransmission modulates dopamine responses to cocaine

As mentioned above, hypocretin neurons send relatively strong projections to the VTA where hypocretin fibers make synaptic contacts with dopamine neurons (Fadel and Deutch, 2002; Peyron et al., 1998). Additionally, both hypocretin-1 and -2 peptides induce burst firing of dopamine neurons and potentiate their glutamatergic-mediated excitation (Borgland et al., 2006; Korotkova et al., 2003) indicating that the hypocretin neurons are poised to regulate dopaminergic function. Given these observations, and the general involvement of dopamine systems in regulating motivated behaviors associated with drugs of abuse, it is likely that hypocretin influences reinforcement processing via actions on mesolimbic dopamine systems.

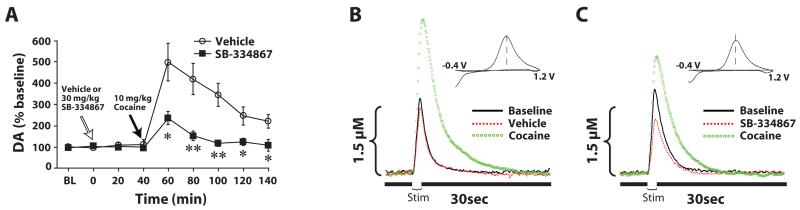

Some of the first evidence that hypocretin systems participated in regulating dopamine responses to drugs of abuse came from studies investigating the pharmacological effects of hypocretin agents on dopamine signaling. Under baseline conditions, infusions of hypocretin-1 into the VTA were shown to increase extracellular levels of dopamine in the prefrontal cortex and NAc of rats (Narita et al., 2006; Vittoz and Berridge, 2006; Vittoz et al., 2008). Consistent with this, hypocretin KO mice show reduced dopamine responses to morphine, despite showing normal levels of extracellular dopamine under baseline conditions (Narita et al., 2006). In recent microdialysis and voltammetry studies we have also shown that hypocretins regulate dopamine signaling, particularly in response to cocaine. In the first set of studies, rats were implanted with microdialysis probes to measure extracellular dopamine levels in the NAc core. On testing days, rats were pretreated with i.p. vehicle or 30 mg/kg SB-334867, forty minutes prior to receiving a single 10 mg/kg i.p. injection of cocaine. In rats treated with vehicle, injections of cocaine produced robust increases in extracellular dopamine levels (Fig. 5A). In contrast, the effects of cocaine in animals treated with SB-334867 were attenuated to nearly half of what was observed in vehicle controls (España et al., 2010). In another set of experiments, animals were implanted with probes in the NAc and also with bilateral infusion cannulae in the VTA. Rats were pretreated with vehicle or SB-334867 (10 nmol) directly into the VTA and as before received a single i.p. injection of cocaine. Similar to that observed with i.p. injections, SB-334867 reduced the effects of cocaine on dopamine signaling. Interestingly, unlike that seen with i.p. delivery, SB-334867 into VTA also reduced baseline levels of dopamine prior to cocaine administration.

Figure 5. SB-334867 attenuates cocaine-induced elevations in dopamine signaling in the NAc core.

(A) Shown are the mean ± SEM of extracellular levels of dopamine (DA) within the NAc core following i.p. injection of vehicle (n=6) or 30 mg/kg SB-334867 (n=6). Shown are representative concentration-time plots and cyclic voltammograms (insets) of dopamine responses from rats that received pretreatment infusions of (B) vehicle or (C) 10 nmol SB-334867 into the VTA. Stim represents the time of electrical stimulation (1 sec, 60 Hz pulse). (Insets in B and C) Cyclic voltammograms depict two current peaks, one at 600 mV (positive deflection) for dopamine oxidation and one at −200 mV (negative deflection) for reduction of dopamine-o-quinone. The position of the peaks identifies the substance oxidized as DA. * P<0.05, ** P<0.01 relative to vehicle.

A similar set of results was also obtained in studies using voltammetry in anesthetized rats. Animals were implanted with an i.v. jugular catheter, a recording electrode in the NAc core and an infusion cannula/stimulating electrode in the ipsilateral VTA. Following collection of a stable baseline of electrically-stimulated dopamine release, rats received an infusion of vehicle or SB-334867 (10 nmol) directly into the VTA. Forty minutes later, rats received a single i.v. injection (1.5 mg/kg) of cocaine and changes in dopamine release and uptake were measured. When compared to vehicle-treated animals, SB-334867 produced a significant reduction in electrically stimulated dopamine release prior to cocaine injection, further indicating that hypocretin signaling regulates dopamine neurotransmission (Fig. 5B and C). In addition to these effects, SB-334867 also reduced the effects of cocaine on dopamine signaling. Relative to vehicle treatment, SB-334867 reduced the effects of cocaine on both stimulated dopamine release and dopamine uptake inhibition.

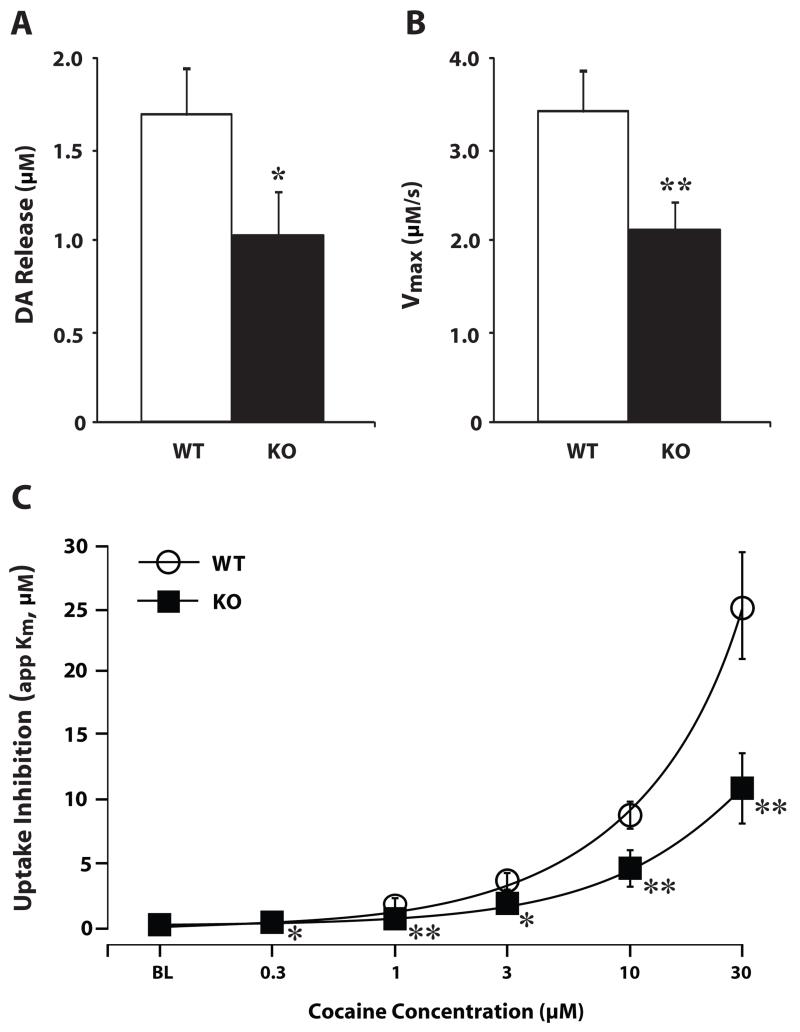

In another set of experiments, we used in vitro voltammetry in brain slices from WT and hypocretin KO mice to examine whether a complete loss of hypocretin signaling would also produce deficits in dopamine signaling. Recording and stimulating electrodes were positioned within the NAc core to allow for measurement of locally-evoked dopamine release. Following a stable baseline of dopamine release, cocaine was bath-applied to the slice at cumulatively higher concentrations. Under baseline conditions, disruption of hypocretin neurotransmission in KO mice results in disrupted dopamine signaling, with a reduction in both evoked dopamine release and dopamine uptake rate (Fig. 6). Furthermore, hypocretin KO mice displayed attenuated dopamine responses to cocaine, showing only half as much dopamine uptake inhibition as WT mice (España et al., 2010).

Figure 6. Hypocretin knockout mice display disrupted baseline dopamine signaling and attenuated dopamine responses to cocaine.

Shown are the mean ± SEM of (A) stimulated dopamine (DA) release and (B) maximal dopamine uptake rate (Vmax) in WT (n=7) and hypocretin KO (n=7) mouse slices containing the NAc core. (C) Shown are the mean ± SEM DA uptake inhibition (apparent Km) in WT (n=7) and hypocretin KO (n=7) mouse slices across cumulative doses of cocaine. * P<0.05, ** P<0.01 relative to vehicle.

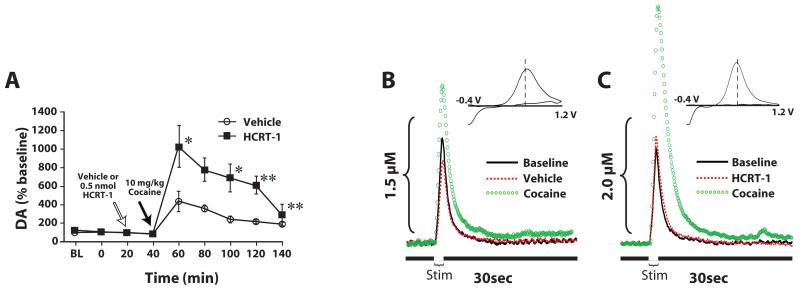

Given that disruptions in hypocretin signaling reduce dopamine responses to cocaine, we next examined whether enhancement of hypocretin signaling would have the opposite effect. Initial experiments used microdialysis to measure extracellular levels of dopamine in the NAc core. Experiments were conducted as described above with the exception that all animals received vehicle or hypocretin-1 (0.5 nmol) directly into the VTA, 20 mins prior to receiving a 10 mg/kg cocaine injection. As shown in figure 7A, infusions of hypocretin-1 had no effect on dopamine levels under baseline conditions (España et al., 2011). Nevertheless, when compared to vehicle, hypocretin-1 significantly augmented the effects of cocaine at increasing dopamine levels. Voltammetry studies in anesthetized rats also showed a hypocretin enhancement of cocaine’s effects. In those experiments, rats were pretreated with vehicle or hypocretin-1 (0.5 nmol) into the VTA 20 min prior to receiving an i.v. injection of 1.5 mg/kg cocaine (España et al., 2011). Within 5 min of infusion, hypocretin-1 significantly increased evoked dopamine release prior to cocaine treatment. Further, hypocretin-1 infusions also augmented the effects of cocaine on evoked dopamine release and dopamine uptake inhibition (Fig. 7B and C).

Figure 7. Hypocretin-1 augments cocaine-induced elevations in dopamine signaling in the NAc core.

(A) Shown are the mean ± SEM of extracellular levels of dopamine (DA) within the NAc core following intra-VTA infusion of vehicle (n=6) or 0.5 nmol hypocretin-1 (HCRT-1; n=6). Shown are representative concentration-time plots and cyclic voltammograms (insets) of dopamine responses from rats that received pretreatment infusions of (B) vehicle or (C) 0.5 nmol hypocretin-1 into the VTA. Stim represents the time of electrical stimulation (1 sec, 60 Hz pulse). (Insets in B and C) Cyclic voltammograms depict two current peaks, one at 600 mV (positive deflection) for dopamine oxidation and one at −200 mV (negative deflection) for reduction of dopamine-o-quinone. The position of the peaks identifies the substance oxidized as DA. * P<0.05, ** P<0.01 relative to vehicle.

Summary

The neurochemical studies described above provide compelling evidence for the hypothesis that hypocretin neurotransmission influences dopamine signaling in the NAc core, particularly in response to cocaine. Moreover, given that many of the described experiments used intratissue infusions of agents into the VTA, these studies indicate that the actions of hypocretin on dopamine release and uptake involve signaling within the VTA.

IV. Conclusions

The hypocretin projection to dopamine neurons of the VTA appears to be a critical modulator of reward and reinforcement processing and dopamine signaling in the ventral striatum. As described above, amassing evidence indicates that an intact hypocretin system is necessary for normal behavioral responses to various drugs of abuse, including cocaine. Studies using multiple self-administration schedules of reinforcement demonstrate clearly that disruption of hypocretin signaling reduces the motivation for animals to take cocaine under conditions that require effortful responding or in which access to cocaine is limited. Consistent with these observations, enhancement of hypocretin signaling exerts the opposite influence by increasing the motivation to take cocaine.

The actions of hypocretin on reward and reinforcement behavior are likely to be associated with modulation of dopamine signaling within the striatum. Neurochemical and electrophysiological studies show convincingly that manipulations to hypocretin neurotransmission result in disrupted dopamine signaling that lead to altered dopamine levels within the NAc core both under baseline conditions and in responses to cocaine and other drugs of abuse. When taken together, both behavioral, electrophysiological, and neurochemical studies provide significant evidence for the hypothesis that the hypocretin system participates in reward and reinforcement processes, particularly as it relates to cocaine, via actions on the mesolimbic system. Further these observations suggest that continued research in this area of drug addiction may lead to development of rational pharmacotherapies based on hypocretin signaling.

Reference List

- Abrahamson EE, Leak RK, Moore RY. The suprachiasmatic nucleus projects to posterior hypothalamic arousal systems. Neuroreport. 2001;12:435–440. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200102120-00048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acquas E, Di Chiara G. D1 receptor blockade stereospecifically impairs the acquisition of drug-conditioned place preference and place aversion. Behav. Pharmacol. 1994;5:555–569. doi: 10.1097/00008877-199410000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akimoto H, HONDA Y, TAKAHASHI Y. Pharmacotherapy in narcolepsy. Dis. Nerv. Syst. 1960;21:704–706. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aston-Jones G, Smith RJ, Moorman DE, Richardson KA. Role of lateral hypothalamic orexin neurons in reward processing and addiction. Neuropharmacology. 2009;56(Suppl 1):112–121. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.06.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backberg M, Hervieu G, Wilson S, Meister B. Orexin receptor-1 (OX-R1) immunoreactivity in chemically identified neurons of the hypothalamus: focus on orexin targets involved in control of food and water intake. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2002;15:315–328. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01859.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blouin AM, Thannickal TC, Worley PF, Baraban JM, Reti IM, Siegel JM. Narp immunostaining of human hypocretin (orexin) neurons: loss in narcolepsy. Neurology. 2005;65:1189–1192. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000175219.01544.c8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borgland SL, Chang SJ, Bowers MS, Thompson JL, Vittoz N, Floresco SB, Chou J, Chen BT, Bonci A. Orexin A/hypocretin-1 selectively promotes motivation for positive reinforcers. J. Neurosci. 2009;29:11215–11225. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6096-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borgland SL, Taha SA, Sarti F, Fields HL, Bonci A. Orexin A in the VTA is critical for the induction of synaptic plasticity and behavioral sensitization to cocaine. Neuron. 2006;49:589–601. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourgin P, Huitron-Resendiz S, Spier AD, Fabre V, Morte B, Criado JR, Sutcliffe JG, Henriksen SJ, de Lecea L. Hypocretin-1 modulates rapid eye movement sleep through activation of locus coeruleus neurons. J. Neurosci. 2000;20:7760–7765. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-20-07760.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boutrel B, Kenny PJ, Specio SE, Martin-Fardon R, Markou A, Koob GF, de Lecea L. Role for hypocretin in mediating stress-induced reinstatement of cocaine-seeking behavior. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2005;102:19168–19173. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507480102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brebner K, Phelan R, Roberts DCS. Effect of baclofen on cocaine self-administration in rats reinforced under fixed-ratio 1 and progressive-ratio schedules. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2000;148:314–321. doi: 10.1007/s002130050056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RE, Sergeeva O, Eriksson KS, Haas HL. Orexin A excites serotonergic neurons in the dorsal raphe nucleus of the rat. Neuropharmacology. 2001;40:457–459. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(00)00178-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caine SB, Koob GF. Effects of dopamine D-1 and D-2 antagonists on cocaine self-administration under different schedules of reinforcement in the rat. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1994;270:209–218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caine SB, Negus SS, Mello NK, Bergman J. Effects of dopamine D(1-like) and D(2-like) agonists in rats that self-administer cocaine. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1999;291:353–360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carboni E, Imperato A, Perezzani L, Di Chiara G. Amphetamine, cocaine, phencyclidine and nomifensine increase extracellular dopamine concentrations preferentially in the nucleus accumbens of freely moving rats. Neuroscience. 1989;28:653–661. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(89)90012-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carelli RM, King VC, Hampson RE, Deadwyler SA. Firing patterns of nucleus accumbens neurons during cocaine self-administration in rats. Brain Res. 1993;626:14–22. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)90557-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cervo L, Samanin R. Effects of dopaminergic and glutamatergic receptor antagonists on the acquisition and expression of cocaine conditioning place preference. Brain Res. 1995;673:242–250. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)01420-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chemelli RM, Willie JT, Sinton CM, Elmquist JK, Scammell T, Lee C, Richardson JA, Williams SC, Xiong Y, Kisanuki Y, Fitch TE, Nakazato M, Hammer RE, Saper CB, Yanagisawa M. Narcolepsy in orexin knockout mice: molecular genetics of sleep regulation. Cell. 1999;98:437–451. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81973-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cluderay JE, Harrison DC, Hervieu GJ. Protein distribution of the orexin-2 receptor in the rat central nervous system. Regul. Pept. 2002;104:131–144. doi: 10.1016/s0167-0115(01)00357-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crocker A, Espana RA, Papadopoulou M, Saper CB, Faraco J, Sakurai T, Honda M, Mignot E, Scammell TE. Concomitant loss of dynorphin, NARP, and orexin in narcolepsy. Neurology. 2005;65:1184–1188. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000168173.71940.ab. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Date Y, Ueta Y, Yamashita H, Yamaguchi H, Matsukura S, Kangawa K, Sakurai T, Yanagisawa M, Nakazato M. Orexins, orexigenic hypothalamic peptides, interact with autonomic, neuroendocrine and neuroregulatory systems. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1999;96:748–753. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.2.748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dayas CV, McGranahan TM, Martin-Fardon R, Weiss F. Stimuli linked to ethanol availability activate hypothalamic CART and orexin neurons in a reinstatement model of relapse. Biol. Psychiatry. 2008;63:152–157. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lecea L, Kilduff TS, Peyron C, Gao X, Foye PE, Danielson PE, Fukuhara C, Battenberg EL, Gautvik VT, Bartlett FS, Frankel WN, van Den Pol AN, Bloom FE, Gautvik KM, Sutcliffe JG. The hypocretins: hypothalamus-specific peptides with neuroexcitatory activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1998;95:322–327. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.1.322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Chiara G, Imperato A. Opposite effects of mu and kappa opiate agonists on dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens and in the dorsal caudate of freely moving rats. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1988;244:1067–1080. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- España RA, Baldo BA, Kelley AE, Berridge CW. Wake-promoting and sleep-suppressing actions of hypocretin (orexin): basal forebrain sites of action. Neuroscience. 2001;106:699–715. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00319-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- España RA, Melchior JR, Roberts DCS, Jones SR. Hypocretin 1/orexin A in the ventral tegmental area enhances dopamine responses to cocaine and promotes cocaine self-administration. Psychopharmacology. 2011:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-2048-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- España RA, Oleson EB, Locke JL, Brookshire BR, Roberts DCS, Jones SR. The hypocretin-orexin system regulates cocaine self-administration via actions on the mesolimbic dopamine system. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2010;31:336–348. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.07065.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- España RA, Plahn S, Berridge CW. Circadian-dependent and circadian-independent behavioral actions of hypocretin/orexin. Brain Res. 2002;943:224–236. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)02653-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- España RA, Jones SR. Hypocretin / orexin knockout mice display disrupted dopamine responses to cocaine. Society for Neurooscience; San Diego, CA: 2010. p. 668.14. [Google Scholar]

- España RA, Valentino RJ, Berridge CW. Fos immunoreactivity in hypocretin-synthesizing and hypocretin-1 receptor-expressing neurons: effects of diurnal and nocturnal spontaneous waking, stress and hypocretin-1 administration. Neuroscience. 2003;121:201–217. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00334-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estabrooke IV, McCarthy MT, Ko E, Chou TC, Chemelli RM, Yanagisawa M, Saper CB, Scammell TE. Fos expression in orexin neurons varies with behavioral state. J. Neurosci. 2001;21:1656–1662. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-05-01656.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fadel J, Deutch AY. Anatomical substrates of orexin-dopamine interactions: lateral hypothalamic projections to the ventral tegmental area. Neuroscience. 2002;111:379–387. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00017-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funada M, Shippenberg TS. Differential involvement of D1 and D2 dopamine receptors in the expression of morphine withdrawal signs in rats. Behav. Pharmacol. 1996;7:448–453. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgescu D, Zachariou V, Barrot M, Mieda M, Willie JT, Eisch AJ, Yanagisawa M, Nestler EJ, DiLeone RJ. Involvement of the lateral hypothalamic peptide orexin in morphine dependence and withdrawal. J. Neurosci. 2003;23:3106–3111. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-08-03106.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greco MA, Shiromani PJ. Hypocretin receptor protein and mRNA expression in the dorsolateral pons of rats. Brain Res Mol. Brain Res. 2001;88:176–182. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(01)00039-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagan JJ, Leslie RA, Patel S, Evans ML, Wattam TA, Holmes S, Benham CD, Taylor SG, Routledge C, Hemmati P, Munton RP, Ashmeade TE, Shah AS, Hatcher JP, Hatcher PD, Jones DN, Smith MI, Piper DC, Hunter AJ, Porter RA, Upton N. Orexin A activates locus coeruleus cell firing and increases arousal in the rat. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1999;96:10911–10916. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.19.10911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara J, Beuckmann CT, Nambu T, Willie JT, Chemelli RM, Sinton CM, Sugiyama F, Yagami K, Goto K, Yanagisawa M, Sakurai T. Genetic ablation of orexin neurons in mice results in narcolepsy, hypophagia, and obesity. Neuron. 2001;30:345–354. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00293-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris GC, Aston-Jones G. Arousal and reward: a dichotomy in orexin function. Trends Neurosci. 2006 doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris GC, Wimmer M, Aston-Jones G. A role for lateral hypothalamic orexin neurons in reward seeking. Nature. 2005;437:556–559. doi: 10.1038/nature04071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris GC, Wimmer M, Randall-Thompson JF, Aston-Jones G. Lateral hypothalamic orexin neurons are critically involved in learning to associate an environment with morphine reward. Behav. Brain Res. 2007;183:43–51. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2007.05.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayduk R, Erman MK, Poceta JS, Mitler MM. Methamphetamine in the treatment of narcolepsy:serum levels,dosage and MSLT. Sleep Res. 1995;24A:316. [Google Scholar]

- Hervieu GJ, Cluderay JE, Harrison DC, Roberts JC, Leslie RA. Gene expression and protein distribution of the orexin-1 receptor in the rat brain and spinal cord. Neuroscience. 2001;103:777–797. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00033-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman DC, Beninger RJ. Selective D1 and D2 dopamine agonists produce opposing effects in place conditioning but not in conditioned taste aversion learning. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 1988;31:1–8. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(88)90302-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman DC, Beninger RJ. The effects of selective dopamine D1 or D2 receptor antagonists on the establishment of agonist-induced place conditioning in rats. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 1989;33:273–279. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(89)90499-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman DC, Dickson PR, Beninger RJ. The dopamine D2 receptor agonists, quinpirole and bromocriptine produce conditioned place preferences. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 1988;12:315–322. doi: 10.1016/0278-5846(88)90050-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollander JA, Lu Q, Cameron MD, Kamenecka TM, Kenny PJ. Insular hypocretin transmission regulates nicotine reward. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2008;105:19480–19485. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808023105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvath TL, Peyron C, Diano S, Ivanov A, Aston-Jones G, Kilduff TS, van Den Pol AN. Hypocretin (orexin) activation and synaptic innervation of the locus coeruleus noradrenergic system. J. Comp Neurol. 1999;415:145–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutcheson DM, Quarta D, Halbout B, Rigal A, Valerio E, Heidbreder C. Orexin-1 receptor antagonist SB-334867 reduces the acquisition and expression of cocaine-conditioned reinforcement and the expression of amphetamine-conditioned reward. Behav. Pharmacol. 2011;22:173–181. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e328343d761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ida T, Nakahara K, Katayama T, Murakami N, Nakazato M. Effect of lateral cerebroventricular injection of the appetite-stimulating neuropeptide, orexin and neuropeptide Y, on the various behavioral activities of rats. Brain Res. 1999;821:526–529. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01131-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imperato A, Di Chiara G. Preferential stimulation of dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens of freely moving rats by ethanol. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1986;239:219–228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane JK, Parker SL, Matta SG, Fu Y, Sharp BM, Li MD. Nicotine up-regulates expression of orexin and its receptors in rat brain. Endocrinology. 2000;141:3623–3629. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.10.7707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kisanuki YY, Chemelli RM, Sinton CM, Williams SC, Richardson JA. The role of orexin receptor type-1 (OX1R) in the regulation of sleep. Sleep. 2000;23:A91. [Google Scholar]

- Ko EM, Estabrooke IV, McCarthy M, Scammell TE. Wake-related activity of tuberomammillary neurons in rats. Brain Res. 2003;992:220–226. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2003.08.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF, Le Moal M. Drug abuse: hedonic homeostatic dysregulation. Science. 1997;278:52–58. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5335.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korotkova TM, Sergeeva OA, Eriksson KS, Haas HL, Brown RE. Excitation of ventral tegmental area dopaminergic and nondopaminergic neurons by orexins/hypocretins. J. Neurosci. 2003;23:7–11. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-01-00007.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence AJ, Cowen MS, Yang HJ, Chen F, Oldfield B. The orexin system regulates alcohol-seeking in rats. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2006;148:752–759. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MG, Hassani OK, Jones BE. Discharge of identified orexin/hypocretin neurons across the sleep-waking cycle. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:6716–6720. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1887-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin L, Faraco J, Li R, Kadotani H, Rogers W, Lin X, Qiu X, de Jong PJ, Nishino S, Mignot E. The sleep disorder canine narcolepsy is caused by a mutation in the hypocretin (orexin) receptor 2 gene. Cell. 1999;98:365–376. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81965-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyness WH, Friedle NM, Moore KE. Destruction of dopaminergic nerve terminals in nucleus accumbens: effect on d-amphetamine self-administration. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 1979;11:553–556. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(79)90040-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus JN, Aschkenasi CJ, Lee CE, Chemelli RM, Saper CB, Yanagisawa M, Elmquist JK. Differential expression of orexin receptors 1 and 2 in the rat brain. J. Comp Neurol. 2001;435:6–25. doi: 10.1002/cne.1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGregor A, Roberts DCS. Effect of medial prefrontal cortex injections of SCH 23390 on intravenous cocaine self-administration under both a fixed and progressive ratio schedule of reinforcement. Behav. Brain Res. 1995;67:75–80. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(94)00106-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mileykovskiy BY, Kiyashchenko LI, Siegel JM. Behavioral correlates of activity in identified hypocretin/orexin neurons. Neuron. 2005;46:787–798. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.04.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nambu T, Sakurai T, Mizukami K, Hosoya Y, Yanagisawa M, Goto K. Distribution of orexin neurons in the adult rat brain. Brain Res. 1999;827:243–260. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01336-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narita M, Nagumo Y, Hashimoto S, Narita M, Khotib J, Miyatake M, Sakurai T, Yanagisawa M, Nakamachi T, Shioda S, Suzuki T. Direct involvement of orexinergic systems in the activation of the mesolimbic dopamine pathway and related behaviors induced by morphine. J. Neurosci. 2006;26:398–405. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2761-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishino S, Ripley B, Overeem S, Lammers GJ, Mignot E. Hypocretin (orexin) deficiency in human narcolepsy. Lancet. 2000;355:39–40. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)05582-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papp M. Different effects of short- and long-term treatment with imipramine on the apomorphine- and food-induced place preference conditioning in rats. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 1988;30:889–893. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(88)90115-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker LA. Place conditioning in a three- or four-choice apparatus: role of stimulus novelty in drug-induced place conditioning. Behav. Neurosci. 1992;106:294–306. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.106.2.294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasumarthi RK, Reznikov LR, Fadel J. Activation of orexin neurons by acute nicotine. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2006;535:172–176. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peyron C, Faraco J, Rogers W, Ripley B, Overeem S, Charnay Y, Nevsimalova S, Aldrich M, Reynolds D, Albin R, Li R, Hungs M, Pedrazzoli M, Padigaru M, Kucherlapati M, Fan J, Maki R, Lammers GJ, Bouras C, Kucherlapati R, Nishino S, Mignot E. A mutation in a case of early onset narcolepsy and a generalized absence of hypocretin peptides in human narcoleptic brains. Nat. Med. 2000;6:991–997. doi: 10.1038/79690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peyron C, Tighe DK, van Den Pol AN, de Lecea L, Heller HC, Sutcliffe JG, Kilduff TS. Neurons containing hypocretin (orexin) project to multiple neuronal systems. J. Neurosci. 1998;18:9996–10015. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-23-09996.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piper DC, Upton N, Smith MI, Hunter AJ. The novel brain neuropeptide, orexin-A, modulates the sleep-wake cycle of rats. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2000;12:726–730. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00919.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plaza-Zabala A, Martin-Garcia E, de LL, Maldonado R, Berrendero F. Hypocretins regulate the anxiogenic-like effects of nicotine and induce reinstatement of nicotine-seeking behavior. J. Neurosci. 2010;30:2300–2310. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5724-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards JK, Simms JA, Steensland P, Taha SA, Borgland SL, Bonci A, Bartlett SE. Inhibition of orexin-1/hypocretin-1 receptors inhibits yohimbine-induced reinstatement of ethanol and sucrose seeking in Long-Evans rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2008;199:109–117. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1136-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ripley B, Overeem S, Fujiki N, Nevsimalova S, Uchino M, Yesavage J, Di Monte D, Dohi K, Melberg A, Lammers GJ, Nishida Y, Roelandse FW, Hungs M, Mignot E, Nishino S. CSF hypocretin/orexin levels in narcolepsy and other neurological conditions. Neurology. 2001;57:2253–2258. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.12.2253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts DCS, Brebner K, Vincler M, Lynch WJ. Patterns of cocaine self-administration in rats produced by various access conditions under a discrete trials procedure. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2002;67:291–299. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(02)00083-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts DCS, Corcoran ME, Fibiger HC. On the role of ascending catecholaminergic systems in intravenous self-administration of cocaine. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 1977;6:615–620. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(77)90084-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers AE, Aldrich MS, Berrios AM, Rosenberg RS. Compliance with stimulant medications in patients with narcolepsy. Sleep. 1997;20:28–33. doi: 10.1093/sleep/20.1.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers AE, Aldrich MS, Lin X. A comparison of three different sleep schedules for reducing daytime sleepiness in narcolepsy. Sleep. 2001;24:385–391. doi: 10.1093/sleep/24.4.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai T, Amemiya A, Ishii M, Matsuzaki I, Chemelli RM, Tanaka H, Williams SC, Richarson JA, Kozlowski GP, Wilson S, Arch JR, Buckingham RE, Haynes AC, Carr SA, Annan RS, McNulty DE, Liu WS, Terrett JA, Elshourbagy NA, Bergsma DJ, Yanagisawa M. Orexins and orexin receptors: a family of hypothalamic neuropeptides and G protein-coupled receptors that regulate feeding behavior. Cell. 1998;92:1. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)09256-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai T, Nagata R, Yamanaka A, Kawamura H, Tsujino N, Muraki Y, Kageyama H, Kunita S, Takahashi S, Goto K, Koyama Y, Shioda S, Yanagisawa M. Input of orexin/hypocretin neurons revealed by a genetically encoded tracer in mice. Neuron. 2005;46:297–308. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Self DW, Belluzzi JD, Kossuth S, Stein L. Self-administration of the D1 agonist SKF 82958 is mediated by D1, not D2, receptors. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1996;123:303–306. doi: 10.1007/BF02246638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Self DW, Stein L. The D1 agonists SKF 82958 and SKF 77434 are self-administered by rats. Brain Res. 1992;582:349–352. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)90155-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharf R, Guarnieri DJ, Taylor JR, DiLeone RJ. Orexin mediates morphine place preference, but not morphine-induced hyperactivity or sensitization. Brain Res. 2010;1317:24–32. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.12.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharf R, Sarhan M, DiLeone RJ. Orexin mediates the expression of precipitated morphine withdrawal and concurrent activation of the nucleus accumbens shell. Biol. Psychiatry. 2008;64:175–183. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shippenberg TS, Bals-Kubik R, Huber A, Herz A. Neuroanatomical substrates mediating the aversive effects of D-1 dopamine receptor antagonists. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1991;103:209–214. doi: 10.1007/BF02244205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shippenberg TS, Herz A. Place preference conditioning reveals the involvement of D1-dopamine receptors in the motivational properties of mu- and kappa-opioid agonists. Brain Res. 1987;436:169–172. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(87)91571-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinnott RS, Mach RH, Nader MA. Dopamine D2/D3 receptors modulate cocaine’s reinforcing and discriminative stimulus effects in rhesus monkeys. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1999;54:97–110. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(98)00162-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinnott RS, Nader MA. Modulation of cocaine’s discriminative stimulus effects by dopamine D(1) agonists in rhesus monkeys. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2001;68:301–309. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(00)00462-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MA, Yancey DL, Morgan D, Liu Y, Froestl W, Roberts DCS. Effects of positive allosteric modulators of the GABAB receptor on cocaine self-administration in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2004;173:105–111. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1706-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith RJ, Aston-Jones G. The orexin / hypocretin 1 receptor antagonist SB-334867 reduces self-administration and cue-induced reinstatement of heroin in rats. Society for Neuroscience; San Diego, CA: 2010. p. 67.6. [Google Scholar]

- Smith RJ, See RE, Aston-Jones G. Orexin/hypocretin signaling at the orexin 1 receptor regulates cue-elicited cocaine-seeking. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2009;30:493–503. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06844.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spealman RD, Bergman J, Madras BK, Melia KF. Discriminative stimulus effects of cocaine in squirrel monkeys: involvement of dopamine receptor subtypes. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1991;258:945–953. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki R, Shimojima H, Funahashi H, Nakajo S, Yamada S, Guan JL, Tsurugano S, Uehara K, Takeyama Y, Kikuyama S, Shioda S. Orexin-1 receptor immunoreactivity in chemically identified target neurons in the rat hypothalamus. Neurosci. Lett. 2002;324:5–8. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(02)00140-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thannickal TC, Moore RY, Nienhuis R, Ramanathan L, Gulyani S, Aldrich M, Cornford M, Siegel JM. Reduced number of hypocretin neurons in human narcolepsy. Neuron. 2000;27:469–474. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00058-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trivedi P, Yu H, MacNeil DJ, Van der Ploeg LH, Guan XM. Distribution of orexin receptor mRNA in the rat brain. FEBS Lett. 1998;438:71–75. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)01266-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uzwiak AJ, Guyette FX, West MO, Peoples LL. Neurons in accumbens subterritories of the rat: phasic firing time-locked within seconds of intravenous cocaine self-infusion. Brain Res. 1997;767:363–369. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)00752-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Den Pol AN. Hypothalamic hypocretin (orexin): robust innervation of the spinal cord. J. Neurosci. 1999;19:3171–3182. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-08-03171.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vittoz NM, Berridge CW. Hypocretin/orexin selectively increases dopamine efflux within the prefrontal cortex: involvement of the ventral tegmental area. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:384–395. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vittoz NM, Schmeichel B, Berridge CW. Hypocretin /orexin preferentially activates caudomedial ventral tegmental area dopamine neurons. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:1629–1640. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06453.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Fowler JS, Logan J, Alexoff D, Zhu W, Telang F, Wang GJ, Jayne M, Hooker JM, Wong C, Hubbard B, Carter P, Warner D, King P, Shea C, Xu Y, Muench L, Apelskog-Torres K. Effects of modafinil on dopamine and dopamine transporters in the male human brain: clinical implications. JAMA. 2009;301:1148–1154. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weed MR, Woolverton WL. The reinforcing effects of dopamine D1 receptor agonists in rhesus monkeys. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1995;275:1367–1374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White NM, Packard MG, Hiroi N. Place conditioning with dopamine D1 and D2 agonists injected peripherally or into nucleus accumbens. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1991;103:271–276. doi: 10.1007/BF02244216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise RA. Neurobiology of addiction. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 1996;6:243–251. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(96)80079-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolverton WL, Johnson KM. Neurobiology of cocaine abuse. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1992;13:193–200. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(92)90063-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida K, McCormack S, España RA, Crocker A, Scammell TE. Afferents to the orexin neurons of the rat brain. J. Comp Neurol. 2006;494:845–861. doi: 10.1002/cne.20859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida Y, Fujiki N, Nakajima T, Ripley B, Matsumura H, Yoneda H, Mignot E, Nishino S. Fluctuation of extracellular hypocretin-1 (orexin A) levels in the rat in relation to the light-dark cycle and sleep-wake activities. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2001;14:1075–1081. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01725.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y, Bendor J, Hofmann L, Randesi M, Ho A, Kreek MJ. Mu opioid receptor and orexin/hypocretin mRNA levels in the lateral hypothalamus and striatum are enhanced by morphine withdrawal. J. Endocrinol. 2006;191:137–145. doi: 10.1677/joe.1.06960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]